This work sample is an excerpt from a longer research paper that analyzes historical census data of the Atlanta metropolitan area to contextualize the changes made to roadways and population demographics from 1940 to 2010. Background information, methodology, and references have been excluded from this sample. All maps shown in this document were created by me using ArcGIS Pro.

Conclusions and Discussion Interpretation of Results

In 1940, before the Lochner Plan proposal, affected census tracts had a total black population of 91,377 out of 255,924, and by 1970, after the completion of most highways and interstates, there was a black population of 153,989 out of 299,386. With the Lochner Plan’s proposed expressway routes, 51.4% of the total population affected by the Lochner Plan’s route would have been black. Compare this to the statewide population proportion of black people in 1970, being only 26%.

Although most routes of the Lochner Plan proposal were not finalized to become highways in Atlanta, the statistics of present-day interstates and population demographics tells a similar story, and the disproportionate impact highway construction has had on the black population in the Atlanta metropolitan area can be seen today.

Figure 8: Preliminary 1946 Lochner Plan Expressway and Majority Black Census Tracts in 1940 and 1970

Figure 8: Preliminary 1946 Lochner Plan Expressway and Majority Black Census Tracts in 1940 and 1970

Of the affected census tracts, the vast majority of majority-black census tracts can be found in the southern half of central Atlanta. A total of 762,021 black people resided in the affected census tracts out of a total population of 1,864,113, ultimately making up a proportion of 40.9% of the affected population. This is disproportionate to the 30.2% statewide population of black people in Georgia.

Along with the analysis of recorded historic plans and the grounds on which many planning decisions were made in relation to racial segregation, GIS is a useful tool to visualize the qualitative and quantitative aspects of this history. Additionally, a uniform visualization of communities that were or could have been affected by roadway plans and identifying which were predominantly black, and what happened to the black population in such neighborhoods

Figure 9: 2010 Census Tracts Affected by Current Interstate System

Figure 10: 2010 Census Tracts Affected by Current Interstate System

Figure 9: 2010 Census Tracts Affected by Current Interstate System

Figure 10: 2010 Census Tracts Affected by Current Interstate System

and those surrounding would be insightful in assessing the effect roadway projects have had on black populations throughout Atlanta’s history.

Limitations

Much of the limitation of this analysis were by lack of sufficient data. As stated in the methodology section, population census data and census tract boundary data that would have been more appropriate to be used (i.e. from 1910, 1930), there was no usable information available. Additionally, many old roadway plans that were described to be discriminatory and were often ultimately never carried out, were difficult to track down and document. Most of the time, no visual aids were provided, and only a textual description of route trajectories, often using historic roads as references that do not exist today, was provided.

Additional Analysis

Aside from roadway-related changes to Georgia’s built environment, it is also important to note other visible changes in population.

Figure 11: Comparison of 1950 and 1960 Census Tracts with Majority Black Population

Figure 12: Comparison of 1950 and 1970 Census Tracts with Majority Black Population

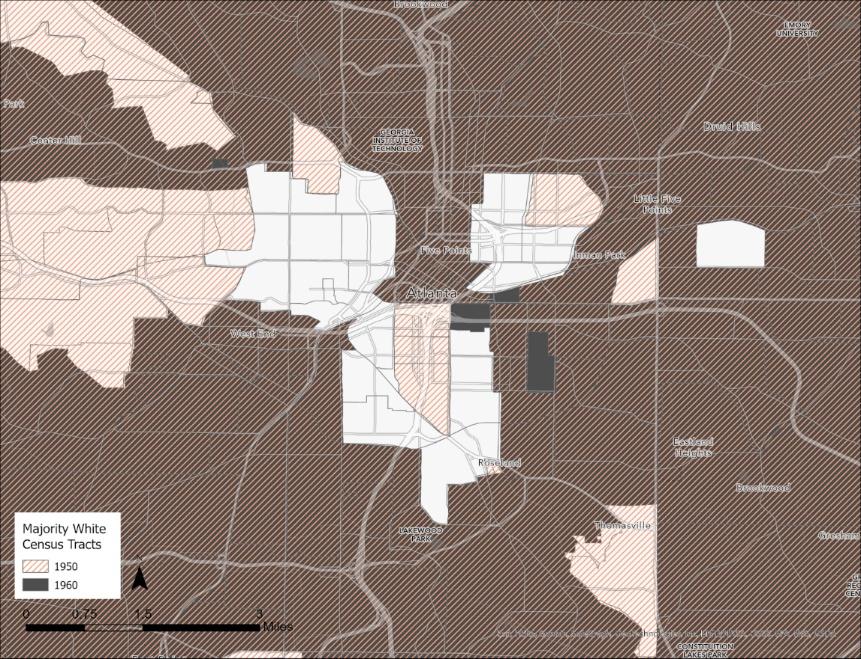

Figure 13: Comparison of 1950 and 1960 Census Tracts with Majority White Population

Figure 12: Comparison of 1950 and 1970 Census Tracts with Majority Black Population

Figure 13: Comparison of 1950 and 1960 Census Tracts with Majority White Population

As seen in figures 11 and 12, as mentioned previously, there is a steady westward expansion of majority black census tracts, and some tracts in central Atlanta are no longer majority black. On the contrary, the twenty-year span between 1950 and 1970 is shown to have seen a drastic outer-city migration of white populations, with central, east, and west Atlanta regions losing most majority-white census tracts.

This change in population is representative of suburbanization and urban renewal movements characteristic of mid-late 20th century American cities. Even before the labeled era of suburbanization and urban renewal, the sense of independence and space that a life in a less densely built environment offered were appealing aspects of life that people would gravitate towards provided they had the means to do so. The separation of space defined usage, and some degree of property that a suburban life offered was much different from the cramped, close quarters living style of urban cities. While there had always been an ongoing trend of wealthy residential areas fleeing from the encroachment of economic activity in the city centers, they used to live in where those who could afford to flee the noise and traffic congestion went northward, a growing segregation of socioeconomic classes became apparent, and those who could not afford to relocate remained in the south and had to make do with worsening housing conditions.

Figure 14: Comparison of 1950 and 1970 Census Tracts with Majority White Population

Figure 14: Comparison of 1950 and 1970 Census Tracts with Majority White Population