Executive Editor

Janset An executive.beaver@lsesu.org

Managing Editor

Lucas Ngai managing.beaver@lsesu.org

Flipside Editor

Skye Slatcher editor. ipside@lsesu.org

Frontside Editor

Suchita epkanjana editor.beaver@lsesu.org

Multimedia Editor

Sylvain Chan multimedia.beaver@lsesu.org

News Editors

Amy O’ Donoghue

Jack Baker

Features Editors

Vasavi Singhal

Angelika Santaniello

Opinion Editors

Shreya Gupta

Aaina Saini

Review Editors

Jessica Chan

Iman Waseem

Part B Editor

Zara Noor

Social Editors

Amelia Hancock

Aashi Bains

Sport Editors

Emerson Lam

Harry Roberts

Illustration Heads

Vivika Sahajpal

Laura Liu

Website Editors

Natasha Pinto

Philippa Park

Photography Head

Yuvi Chahar

Podcast Editor

Salma Abuletta

Noor Sayegh

Formatting Editor

Oliver Chan

Social Secretary

Isabella Liu

Social Media

Sophie Alcock

Yashve Rai

Anika Balwada

Anisha Shinde

Khushi Khandelwal

Skye Slatcher Flipside Editor

At the start of term, this was written on the oor outside the Saw Swee Hock:

‘you can’t want two contradictory things’ (with a little pigeon drawn underneath)

‘of course i can! how else would i get to feel everything?’ (with a little rat drawn underneath)

It was visible from the Media Centre, and in week zero I

would come in and check it was still there. And one day it was gone. Presumably the estates had scrubbed it o Maybe they just didn’t get it.

Walking around Holborn and Chancery Lane, if you just look down, you’ll nd similar pieces of street art e artist behind the pigeon and rat cartoons is @beakandsqueak. ere’s another one of his around the corner from Old Building that says, “i dont need much. just someone who talks like a poet, laughs like a drunk, and walks home like

weve got nowhere to go.” I’ve got an album in my photos app of all of the beakandsqueaks I’ve spotted around London. It’s come to feel a bit like a personal treasure hunt. Move over, Banksy.

It’s hard to avoid the words of these artists — for example, @lxsinglove has written all around London with quotes you will probably have seen on your artsy friend’s Instagram story. Sometimes I must admit I don’t get them either — and some of them I just don’t like. But I always stop to look at

them — a brief pause in my busy days.

I’m not sure there is any lesson to take from this. Maybe just a reminder to look down sometimes. And to take pictures when you see this street art — it (probably) won’t be there forever.

I’ll leave you with one of my favourites:

‘to do:

get through today, today’

Any opinions expressed herein are those of their respective authors and not necessarily those of the LSE Students’ Union or Beaver Editorial Sta

e Beaver is issued under a Creative Commons license. Attribution necessary. Printed at Ili e Print, Cambridge.

Room 2.02

Saw Swee Hock Student Centre

LSE Students’ Union

London WC2A 2AE

News Editors Jack Baker Amy O’Donoghue news.beaver@lsesu.org

Amy O’Donoghue News Editor

Yuvi Chahar Photography

The Education Secretary, Bridget Phillipson, has confirmed that tuition fees will rise with inflation for the next two years. Legislation to make it so that they will increase automatically every following year has also been announced. Current Home students at LSE will pay the increased rate from

the 2026-2027 academic year onwards, with incoming students paying the higher rate for the entirety of their degree.

The government’s Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper was published on 20 October 2025. The paper announced that tuition fees will increase proportionally to inflation each year, likely according to the Retail Price Index minus mortgage payments (RPIx).

Tuition fees increased last year for the first time since 2017, when they were capped at £9,250. In 2024, they rose to £9,535 for the 2025/26 academic year.

The new fee levels will only be permitted for universities that meet the quality threshold set by the Office for Students (OfS). The OfS rates universities based on student experiences and outcomes, using the

Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) as its metric. LSE was awarded an overall ‘Silver’ rating during the most recent evaluation in 2023. This means LSE will almost undoubtedly be subject to the incoming tuition fee rises.

The fee increase is intended to relieve universities of financial pressure following a decade of frozen fees and over 12,000 job cuts in the past year. Over 40% of UK universities anticipated a financial deficit this year. However, LSE is in a more fortunate financial position than most. They reported a surplus in their 2023/2024 financial statement, noting that 66% of their students are from overseas and pay international tuition fees.

Isabel Howe, LSESU Welfare and Liberation Officer, told The Beaver: “This fee rise will make LSE a more exclusive in-

stitution. I am worried for the future of our student body’s class diversity; these proposals will deter working-class people from LSE, making it even harder for working-class students to feel like they belong here.”

Maintenance loans will also increase with forecast inflation. Those claiming the maximum amount, who come from the lowest-income households, will see the biggest cash increases. The Education Secretary also recently announced that maintenance grants will be reintroduced by 2029, after their abolition in 2015. These would be given to “tens of thousands” of students from lower-income backgrounds and do not have to be paid back. However, these will only be given to students on “prior ity courses” selected by the La bour government, which have not yet been announced and may not be available at LSE.

LSESU Education Officer, Nooralhoda Tillaih, told The Beaver that there are “crucial and detrimental caveats” to the plans outlined in the government’s White Paper. She stated that the maintenance grants being allocated only to “priority courses” means they are unlikely to support LSE students and will turn poorer students away from the humanities.

In response, an LSE spokesperson stated: “LSE is committed to ensuring no students are put off from applying due to financial concerns, and that money does not prevent students from thriving while studying here. This is why we invest significant amounts of fee income into bursaries, pre-university outreach, and support.”

Read the full article and LSE’s response online.

On Friday, 31st October, students met for the inaugural meeting of LSE’s Your Party branch. Students from various le -wing associations, including the LSESU Communist Society and LSESU Students for Justice in Palestine, met to discuss strategy, policies and their approach to revitalising the student movement.

Your Party, as it is currently named, is a new le -wing party founded by prominent gures of the British le , Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana. Following their announcement earlier this year, self-organised local groups have been formed throughout the UK, such as the LSE Your Party group.

e inaugural meeting was run without a formal leadership structure, with an emphasis

on self-organising within the student body. e focus of the meeting was on democratically discussing the national party’s founding statement, as well as laying the groundwork for the year ahead.

Students talked critically about Your Party nationally, as well as their optimism for an authentic class-based party. Many expressed discontent over the “lack of unity” that has le many feeling “extremely disheartened”.

Following the unilateral launch of a national membership portal, Sultana accused Corbyn and other le -wing MPs of operating a ‘sexist boys-club’ and ‘excluding’ her from decision making processes. is resulted in Corbyn and his allies pursuing legal action against Sultana before the two made amends.

Despite this, the prevailing hope was that Your Party at LSE would “bring together the multiple forms of student activist groups at LSE” who have otherwise become “siloed without a central group to work together”, an unnamed student said.

Tarik A, President of the LSESU Communist Society, felt that students were “using this historic opportunity to organise for change in our own locale”. In his view, they were “relating a mass political movement” in the form of Your Party “to our own situation on campus”.

Monty, who led the session but who holds no formal leadership role, echoed Tarik’s words, stating that they were “using it as an opportunity to unify and build a mass movement”. He felt they needed to ensure that Your Party both national-

ly and locally “met the needs of the people” when it comes to le -wing economic policy and presenting an alternative to the neoliberal order.

Le -wing student activism has long been an aspect of life at LSE. In the 1960s, anti-apartheid activist Marshall Bloom led widespread protests against the appointment of Sir Walter Adams as director due to his previous role in racially segregated Rhodesia. More recently, in 2024 students occupied the Marshall Building in an attempt to force LSE to divest from its investments in Israeli arms and fossil fuels.

Students hoped to carry on this “rich tradition” and act as a new home for le -wing students. Prior to the group’s formation, the Labour Society and Communist Society were the only active le -wing societies at LSE, with the Greens

defunct since last year. When asked about the di erences between Your Party and the Greens, one student expressed concern that the Greens “were not a class-based party”, whereas Your Party would be.

e national party has yet to formally agree on policy, with this planned for the national conference happening in late November.

You can nd more information about the new society on their Instagram: @lseyourparty

Alba Azzarello Contributing Writer

Protests erupted outside the Marshall Building on ursday, October 16th, in response to an invite-only event hosted by LSE in conjunction with e Dinah Project. e event was titled ‘A Quest for Justice — October 7th and Beyond’. Students moved from the Marshall building and mobilised in front of the Cheng Kin Ku building, where the event was being held, touting ‘Viva Palestina’ and ‘LSE Manufactures Consent for Genocide’ banners.

e Dinah Project is an Israeli organization made up of academics, legal experts, and former civil service members. It aims to raise awareness and calls for justice for victims of sexual violence on 7 October 2023, through reports calling on the UN to blacklist Hamas. e report aims to set out a new legal basis to prosecute Hamas for con%ict-related sexual violence. e Dinah Project calls for a changing of the evidentiary threshold to prosecute con%ict-related sexual violence, including “additional ways to build the evidentiary bases beyond those typically relied upon in domestic criminal law”.

In response to their most recent report, Reem Alsalem, the

U.N. Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, emphasised that reports of such violence must be independently veri ed and investigated, and that perpetrators must be held accountable. Alsalem also emphasised that, while the special commission appointed to investigate has found “patterns indicative of sexual violence against Israeli women at di erent locations”, the commission has been “unable to independently verify speci c allegations of sexual and gender-based violence due to Israel’s obstruction of its investigations”.

LSESUJP further asserts that:

“ e spurious, one-sided analysis of sexual violence that this event presents, fundamentally ties a narrative of sexual violence to a colonial ideology

...rather than advancing a systemic understanding of it.”

e open letter received hundreds of signatures, from students and sta alike. However, the event continued with little publicity.

Alsalem also wrote that “neither the Commission nor any other independent human rights mechanism established that gender-based violence was committed against Israelis on or since 7 October 2023 as a systematic tool of war.”

On 12 October 2025, LSESU Justice for Palestine released an open letter, citing Alsalem and calling for the cancellation of the event, stating that the event was being hosted despite concerns over the %awed assertions and methodological shortcomings presented in the report. ey claim it “undermines both academic freedom and the standards of rigorous academic research that LSE so proudly claims to uphold”.

An LSE spokesperson said: “ is event was organised by a group of faculty from di erent departments. It was chaired by an LSE academic, and featured a Q&A session with the audience a er the main lecture.” e spokesperson also clari ed that “the event was not hosted by LSE Communications,” as the open letter alleges.

Demonstrations against the event continued well into the evening, with the LSESUJP reporting ‘agitators’ spitting on students. In a post on Instagram since, the society stated that LSE failed to protect student protestors from these ‘agitators’ present on campus.

Multiple students criticised LSE’s hosting of an event about sexual violence against women in Israel, arguing that LSE

has failed to e ectively address misconduct claims against its own professors. One student stated: “We know LSE does not care about women, or it would not protect professors who are sexually violent on campus, so this is not about women. is is to push Zionist ideology on campus.”

Onlookers at the protest had mixed emotions, with one stating they “felt proud” to see students standing up to the event, whilst another stated that “ is should be the least controversial speaking event at LSE.” e student further explained that “the entire facade of this protest is dishonest; it’s not about apartheid or genocide or whatever else they claim; they are protesting an event of an organisation that supports victims and survivors of sexual assault.”

Another student involved in the protest remarked:

“Our institution is a prestigious institution, its name has value to be put on things, and we can’t be throwing that around.”

versy remains. e society reiterated its opposition to the event, stating: “We stand rmly against the manipulation of sexual violence discourse to justify Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. is instrumentalisation of survivor justice is both unethical and complicit in colonial violence.”

ey point out that the event “was hidden from public view, not listed on LSE’s website, and closed to students and sta . Why are members of our own community excluded from knowing who is being platformed on our campus?”

An LSE spokesperson told e Beaver:

“Freedom of academic enquiry, thought, and speech underpins everything we do at LSE. is was a private research-related event organised by a group of academics from di erent departments. It was chaired by an LSE academic and featured a Q&A session with the audience a er the main lecture.”

While protests around the event have subsided, contro

Janset

An Executive Editor

Ryan Lee Photography

Staff and faculty at LSE have launched a petition addressed to senior management condemning the conclusions of the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Review that was carried out earlier this year. So far, the petition has garnered over...

134 signatures

...and the undersigned are expecting a response from the university by Tuesday, December 2.

The group have two demands: LSE’s immediate divestment from ‘egregious activities’ and an adoption of an Ethical and Sustainable Investment Policy (ESIP) to guide financial policy. They have proposed alternative investment avenues, such as low emission technologies, promotion of pay equity across gender, and the circular economy. They also call for the creation of a Community Oversight Group to keep the Investments Sub Committee accountable to the implementation of ESIP when managing investment funds.

This comes in the wake of an ESG review initiated in July 2024. LSE Council initiated a review of the School’s ESG Policy, with the intention of addressing “both the questions regarding LSE’s investment policies and practices, and appropriate arrangements for ongoing governance and oversight”. The process was pulled forward by a year in response to increased student mobilisation calling for divestment, with the campaign culminating in the encampment of the Marshall Building for over a month in May 2024. It was dismantled on 17 June 2024, with LSE becoming the first university to evict its own students in the UK after being granted an

The Council formed an ESG Review Group composed of independent experts on investment policy from LSE and a Consultative Group that consisted of three academics, three staff, and three students. The latter was tasked with representing the wider campus community by critically engaging with and advising the former on its recommendations to the Council.

After months of deliberation and four formal meetings between the two groups, on 10 July 2025, the Council announced the adoption of the following policies as informed by the Review Group’s findings: holding annual General meetings, pushing for increased transparency surrounding LSE’s endowments, and revisiting their policies every three years as opposed to five.

However, staff and faculty have been expressing great concern over this outcome. A member of professional services staff told The Beaver: “The Review Group Report and Council’s statement made it explicit that the university will continue to prioritise maximising returns on investments above human rights and environmental concerns. Many of us in the LSE community find this abhorrent and unacceptable.”

Their demands centre around the claims made in LSESU Palestine Society’s report ‘Stakes in Settler Colonialism’, published in June 2025.

e report explains that there is at least £131 million invested in ‘egregious activities’:

crimes against the Palestinian people, the global arms trade and climate breakdown. For instance, LSE currently invests in 21 European financial institutions, like HSBC and Barclays, that are listed by the High Commissioner for Hu-

man Rights as involved in illegal settlement activities in the Occupied Palestinian territories. LSE also has investments in 176 companies like BP and National Grid, which are involved in the extraction and distribution of fossil fuels.

The petitioners highlight that the proportion of LSE’s portfolio value that the investments associated with egregious activities contribute to has increased by 5% since 2024.

They also underscore that divestment has been a policy action that the campus community has endorsed en masse. The SU held a referendum in 2024 that saw 89% of votes favour divestment from fossil fuels and weapons. Further more,

in 2025, 88.6% of stu dents voted in favour of the SU acknowledging the ongoing genocide in Palestine — this vote further increased the impetus for calls of divestment from activities that violate human rights.

this issue to get involved. You can support this campaign by sharing our petition and participating in our campaign processes.”

Despite collective opinions and the reports of the Consultative Group, petitioners argue that the Review Group has failed to consider divestment from these holdings. On the other hand, the Review Group argued in their report that considerations into human rights and the interpretation of international law is inherently subjective, and thus cannot be applied to LSE’s holdings without it becoming an explicitly politicised matter.

They also mention that international law is unanimously understood to regulate relations between states, but there is no such unanimity surrounding its enforceability on the activities of private firms. Subsequently, the Council reported that concerns for the treatment of Palestinians would be “explicitly placed beyond the purview of the Review”.

A representative from the SU said: “We remain committed to our democratically passed policy calling for divestment. This policy reflects what students want and we will continue to lobby LSE to divest in line with students’ priorities.

We encourage all students who wish to see progress on

The petitioners note that other institutions have responded to calls of divestment from their commitments. Subsequently they claim, it is also financially viable for LSE to divest. Recently, King’s College Cambridge announced that it would be excluding investment from arms companies engaged in illegal activities like “the occupation of Ukrainian and Palestinian territories”. Simi

lar shifts in rhetoric have taken place in other universities, such as Trinity College Dublin and King’s College London.

Staff and faculty are calling for LSE to follow suit and to adopt the Consultative Group’s ESIP framework. The group has outlined how the LSE has a commitment to abide by its own Ethics Code, its Sustainability Strategic Plan and the UN Principles for Responsible Investment. Multiple representatives of the petition have asserted that refusing to adopt this framework “goes against the School ethos of striving for the betterment of society”.

An LSE spokesperson responded: “Following the recent review of the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Policy, LSE remains fully committed to strengthening our approach to responsible investment. e review included a thorough assessment of the policy and addressed questions raised by LSE students and sta related to the School’s investments.

As a result of this project, beginning this academic year LSE will review the current investment lters related to fossil fuels, tobacco and armaments to further reduce our exposure to these sectors, as appropriate.

e ESG report is available to read on the LSE website.”

Features Editors

Angelika Santaniello

Vasavi Singhal features.beaver@lsesu.org

Suchita Thepkanjana Frontside Editor

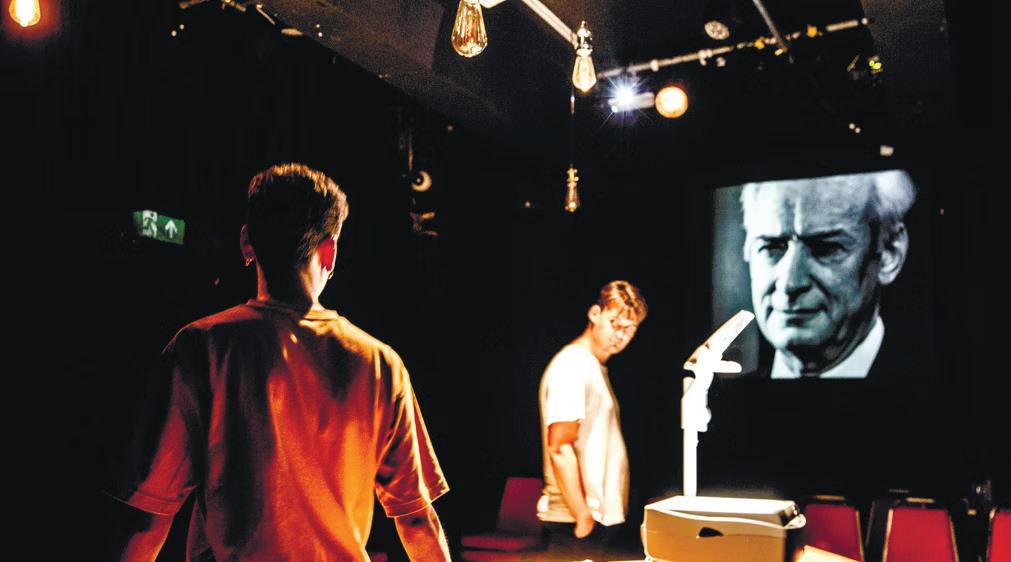

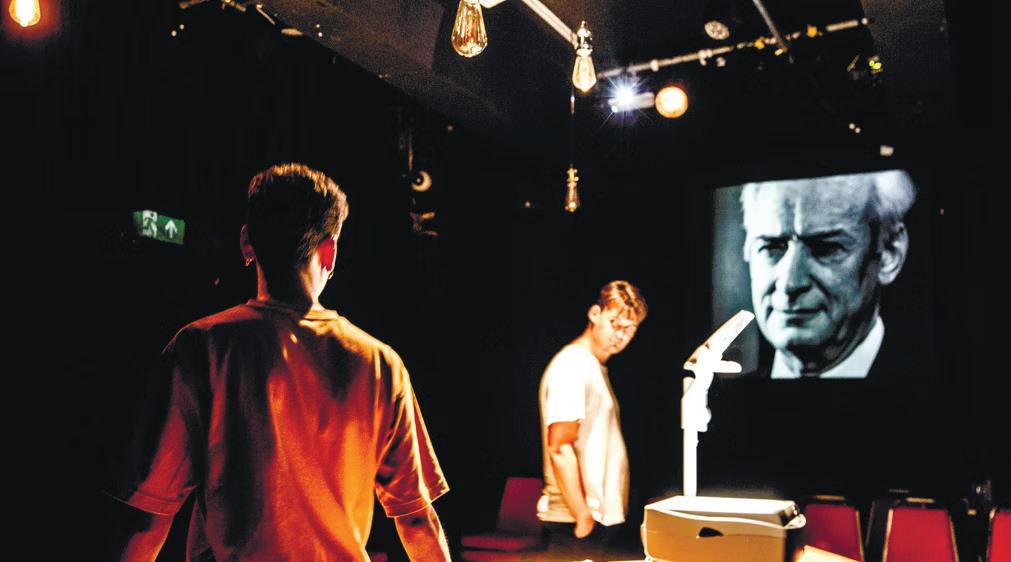

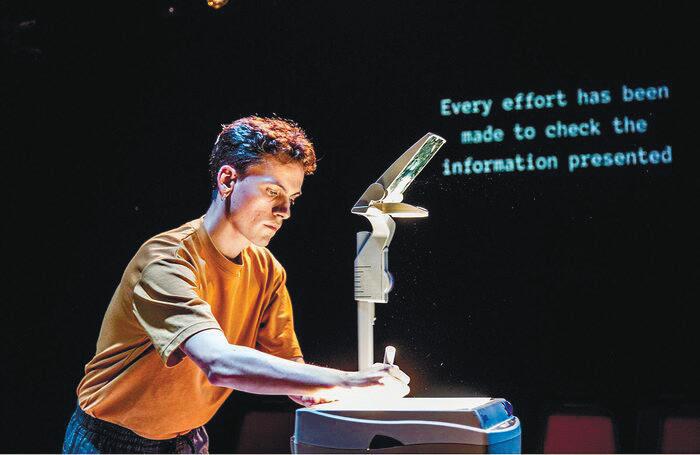

Jack Sain Photography

Content Warning: this article mentions suicide.

The date is 1968. e place is the Old eatre, a dusty lecture hall at the heart of LSE’s campus. Inside are three thousand students, not watching a lecture or taking notes, but protesting against the School Director’s ties to apartheid.

is is how the play Lessons on Revolution by Gabriele Uboldi and Sam Rees begins. For the next hour, the two tell stories about this protest, but also about their own lives — growing up, keeping secrets from family, and battling eviction in a gentrifying London.

Weaving together seemingly unrelated fragments of history, Lessons on Revolution is ultimately an ode to the revolutionary spirit and a plea to keep it alive.

In the writers’ own words, “this story is about change and how we talk about it.”

e date was 2023, and the place was the LSE Library. Gabriele and Sam had leafed through documents about LSE in 1968 for hours, gathering inspiration for their new play.

e two had conceived of this idea a er reading about the student occupation of the Old eatre in a history book, according to Sam.

“I was very interested in the idea of ‘68 as a moment […] and how it echoes and ripples,” he says.

Indeed, 1968 was a pivotal year in global and local history. Situated in the context of the Cold War, the Vietnam War, and worldwide waves of decolonisation, LSE and its international ties became a centre for political tension and action. In this fateful year, Walter Adams, who nancially supported minority rule and apartheid in Rhodesia, was appointed School Director. A er several unsuccessful attempts to negotiate with Adams, activists David Adelstein and Marshall Bloom urged students to occupy the Old eatre in protest.

“LSE was and is an immensely rich and well-resourced university in the most important city in the imperial core […] it’s only

natural that the rami cations of empire would converge on it,” Sam describes. “LSE then becomes a place where a lot of these struggles come to bear.”

Gabriele adds: “We cared about LSE because it was just around the corner and because we’d just been students ourselves. I think that connection was really helpful in terms of how we got people engaged.”

Given this, they incorporated the archived pieces — blackand-white photographs, copies of the revolutionary pamphlet Agitator, letters from Walter Adams — throughout the play.

But the story does not end at this protest, this single moment in time. Gabriele and Sam emphasise that while anchored in a speci c event, the play is not meant to be a perfect historical account. Rather, it is about what LSE in 1968 can teach us about struggle and the desire for change that continues across decades and circumstances.

“ is documentary piece is, in many ways, the documentary of our lives as much as it is a piece about that period itself,” Sam explains.

Gabriele adds that the most important takeaway is “to under-

'Weaving together seemingly unrelated fragments of history, Lessons on Revolution is ultimately an ode to the revolutionary spirit and a plea to keep it alive.'

“If things were di erent once, then they can be di erent again. It’s 1968 as long as we believe it is.”

stand yourself as part of a current struggle, but also as part of the continuation of what was going on in ‘68 and in all these di erent moments”.

At the core of this play and of revolution, no matter when or where it takes place, is the persistent determination that things always can and should change.

e date was July 2024, and the place was the Marshall Building, where students had set up an encampment to protest the university’s complicity in arming Israel. LSE had just become the rst university to evict its student encampment.

For current LSE students, Lessons on Revolution might feel eerily familiar. As Gabriele puts it, “what was happening back then is exactly what is happening right now.”

In both instances, there was a struggle and an attempt at revolution. But in both instances, revolution failed.

Walter Adams still became School Director, many student protestors of 1968 faced disciplinary measures, and Marshall Bloom committed suicide two

years later. In the same way, the 2024 encampment was dismantled, and LSE has not divested.

Yet the most signi cant point is not that they failed, but that they were there in the rst place.

Revolution is not solely characterised by dramatic, tangible policy change. Revolution is also, as Sam and Gabriele say in the play, “sitting in a room with 2999 other people, not doing anything, but existing politically, having a glimpse of a better future”.

“ e success-or-failure binary is not useful,” Sam argues. “It sees history as an object that is nished.”

“ ere are ripples that come out of any particular activist movement […] ose ripples are still there.”

Lessons on Revolution is a story about history, politics, and failure. But above all, it is a story about hope. It is a story about remembering that change is always a real possibility. In the words of Gabriele and Sam,

“If things were di erent once, then they can be di erent again. It’s 1968 as long as we believe it is.”

LSE Media Relations have declined to comment on this article.

Angelika Santaniello

Features Editor

Skye Slatcher

Flipside

Editor

Yuvi

Chahar

Photography

It is now the latter half of Autumn Term. Course selection has closed and, for many, formative assignments have been set. Despite exam season being in the upcoming Spring Term for Law students; some students may be re ecting on their exam strategy, whether it is about adjusting for open-book exams or looking back at a closed-book exam experience.

e very nature of exams means students may not be able to separate exam season from their academic deep dives into their subject. So, what happens when exam formats are suddenly changed?

For the LSE Law School, this happened on the rst day of term when the change was announced to students with a follow-up email to students on

exam format for their course without any direction from the Law School.”

“ e Law School keeps assessment formats under continual review. In this case, speci c changes were recommended to protect the integrity of the programme, and thereby the value of the LLB degree.”

How can students handle this? e emphasis on choosing “the most academically appropriate exam format” calls into question how far the decision to change the exam policy was unilateral, and whether it involved su cient consultation with members of the LSE Law School, namely students.

How comfortable do students feel raising concerns about the changes in exam policy?

Sam* expressed dissatisfaction about the approach the Law school had taken: “While I accept that changes can occur, such changes must be both reasonable and subject to proper consultation.”

“[S]tudents are not passive recipients but paying consumers entitled to certain standards and protections”

2 October. e change broadened the scope of assessment modes to closed-book, ‘partial open-book’ (in which students are permitted to bring a single-sided A4 sheet of paper with them into the exam), or wholly open-book.

A Statement from the LSE Law School

e LSE Law School has provided e Beaver with an ofcial statement regarding the change in exam policy: “As outlined in our email to students on 2 October, the new policy enables convenors to choose the most academically appropriate exam format to assess their course.”

“ is includes, where suitable, the use of open book exams. Convenors have full freedom to choose the most appropriate

were overwhelmingly negative.

One student said that it “felt like a massive betrayal and that the Law School was purposefully being deceitful”. Others felt “shock” and “outrage” that “such a signi cant change was made with such a dismissive attitude”.

To many it came as a surprise that LSE would neglect to give any o cial noti cation of these changes, with students learning of the development “through the grapevine”.

One respondent’s tone was entirely di erent: “I was happy. I think it’s ridiculous they were open-book in the rst place. We all know everyone just cheats their way through.”

On the one hand, a respondent supporting the change said that “everyone is just mad that they actually have to study now.”

“ e outcome will be more rote learning, less critical thinking, and therefore worse quality [academic performance].”

ble-sided sheets, or even three if they’re feeling tight.”

“[S]tudents are not passive recipients but paying consumers entitled to certain standards and protections,” they added.

According to Taylor*, the change in exam policy is “a step back which undermines accessibility for many students and disregards important considerations of student welfare.”

e change in exam policy requires an arguably stronger, more coherent justi cation: from framing a discussion around contractual obligations marking the LSE Law School experience, to concerns about student welfare.

Initial Reactions:

With this in mind, we conducted a survey asking LSE Law students for their responses to these changes. e reactions

Conversely, closed-book exams were described as “an ineffective way to assess a person’s knowledge”, with some saying that it is not a test of understanding or reasoning but of memory. Others described it as “archaic” or “ableist” to assume everyone can learn and revise in the same way for a closed-book exam.

Also, most other top global universities have open book exams. Some have said that the impact of this is that LSE Law students’ grades are lower in comparison making the application process for training contracts and pupillage more di cult.

So, is the new ‘partial openbook’ exam a fair compromise?

One replied that it is “absolute nonsense”; another called it a “slap in the face for those who prefer open book exams”. Some highlighted that one single sheet of A4 feels insucient — “a better compromise would have been ve dou-

For some modules to have gone from dissertations to single-sided, A4-sheet exams so quickly is shocking to many students.

In light of the changes, students’ approaches to studying have changed.

To our question about whether they were satis ed with their professors’ responses, most gave the same answer: No.

One said “most teachers were incredibly dismissive, saying they ‘didn't understand’ [students’] xation on exam format. is is a ridiculous thing to say when it should be wellknown that students frequently act so as to maximise their exam performance.”

is respondent added that students “are under more pressure to do so in order to secure training contracts and mini pupillages in the current econ omy”.

Concerns about the change in exam policy exceed mere speculation: students are questioning the very “integrity” and “value” of their programme. What we can learn from responses to the change in exam programme is the need to push the “continual review” of it. A ecting a degree focused heavily on analytical skills, critical thinking, strong argument, and textual interpretation, it appears that the changes required a stronger justi cation.

Will students’ worries be remedied, or is the case closed for the LSE Law School?

e Beaver contacted LSE Media Relations for a comment. LSE Media Relations have stated that no further comment will be provided.

*Names have been changed to preserve anonymity.

Anna Alexiev

Contributing Writer

Laura Liu Illustrator

As the rst month of the Autumn Term comes to a close, the celebratory buzz of Freshers' Week is giving way to a much harsher reality. When talking to fellow rst-years, one topic keeps resurfacing, usually paired with the same mix of panic and anxiety: Spring Weeks.

Despite hardly being a month into this university, a period meant to celebrate the huge achievement of getting here, many students are already frantically chasing the next milestone.

It may arguably be an expecta tion to be surrounded by am bition at LSE. e situation is perhaps best summarised by one student who confessed, “It’s a numbers game. I think I applied to over 100 Spring Weeks last year.”

In accordance with the “E” in “LSE”, it’s only logical to view this problem through the lens of an economist. Currently, we are dealing with a classic supply and demand problem, except here, the gap between the two is getting wider with each passing year. e demand for prestigious Spring Weeks is skyrocketing, while the supply of spots remains xed.

Let’s consider the odds. In

'True

tically much more likely to secure a place at LSE itself, which has an acceptance rate of approximately 6.33% (1 in 16 applicants get in).

Excess demand doesn't just clear the market, but instead actively generates behavior that creates more excess de-

apply makes me wonder if I'm supposed to be doing it too?”

is feeling of being compelled to chase the next achievement, even an unwanted one, is not accidental. It is simply how the system is designed. We exist in a society built upon a perpetual, o en anxious, state of longing,

"Arguably,

can’t be ranked in the way that these systems expect us to be.

We exist outside of the clean, predictable models of economic theory, navigating a self-perpetuating system that treats our time, e ort, and mental health as inputs in a zero-sum numbers game. Ar-

it is the system that is awed, not the individual caught within its relentless cycle."

mand in the following cycle. whether that be for professional success, for money, or

guably, it is the system that is %awed, not the individual

progress would mean demanding that universities, ranking bodies, and employers value curiosity, individuality, and well-being just as much as corporate logos on graduate destinations.'

2020, Goldman Sachs reported receiving 17,000 applications for only 450 Spring Week places, translating to a brutal 2.6% acceptance rate.

At Morgan Stanley, the reported acceptance rate for their 2020 program was similarly cutthroat, at 4%. To put this into context, you are statis-

. application habits, ultimately worsening the perceived scarcity.

e intense pressure of the environment is perhaps best captured by a rst-year student, only a week into the Autumn Term, who admitted: “Honestly, nance isn't my goal, but seeing everyone around me

ral selection.

ose who opt out or slow down are o en quickly (and unfairly) labelled as “lazy” or insu cient. Most of us accept this as the inherent, natural order of things: a warped, modern revision of Darwinian theory.

But we must remember the crucial distinction: we are real people, not merely statistical entities, nor perfectly rational agents designed for optimisation. We

was blunter: “It’s not ambition, but survival.”

And that’s the paradox. Everyone recognises the problem, but nobody wants to be the rst to stop moving. Rejecting the system feels too risky: risky to careers, risky to identity, and risky to the carefully curated narrative of success that brought many of us here. e relentless motion, the perpetual striving, is what keeps the gears turning.

A collective pause would expose just how dependent this celebrated structure is on student anxiety, on our willingness to measure ourselves against impossible standards.

Without that momentum, the illusion of scarcity and prestige might not shatter entirely, but it might look smaller, quieter, and a lot less impressive than we were taught to believe.

True progress would mean demanding that universities, ranking bodies, and employers value curiosity, individuality, and well-being just as much as corporate logos on graduate destinations.

As a friend at UCL observed (proof this mindset isn’t exclusive to Houghton Street): “If intellectual curiosity doesn’t count unless it ts on a CV, we should call it branding, not education.” Until the system stops treating students like perfectly optimised nancial products, we will continue to sprint toward burnout, mistaking exhaustion for ambition and motion for meaning.

achievement, what would happen if students actually paused? What if, even brie%y, we chose not to feed the anxious cycle of “constant wanting”?

Several students I spoke to admitted that the idea sounds great in theory and terrifying in practice. One laughed and said, “I’d love to take a break, but I’m worried everyone else will sprint past while I’m catching my breath”. Another

Read the full article online.

Sherkan Sultan Contributing Writer

Sylvain Chan Illustrator

“

It is dangerous to be right when the government is wrong,” Voltaire wrote. One might add, though spared the ordeal of a university risk-assessment committee, that it is fatal to be right when a university is desperate to appear neutral.

On 16 October, LSE hosted a closed-door event titled ‘A Quest for Justice — October 7 and Beyond’. e name has the bureaucratic fragrance of something already embalmed. e gathering is based on the Dinah Project Report, which purports to document sexual violence committed by Hamas on 7 October, in part funded by the British government — a document that would struggle to meet even undergraduate research standards. e lead author on the report, Halperin-Kaddari, couldn’t substantiate any case from over 1000 witnesses’ testimonies.

found no evidence of orders, noting that Israel’s non-cooperation impeded veri cation. e

UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women later added that no independent mechanism had established sexual or gender-based violence against Israelis as a systematic tool of war or genocide. Even coverage of the report’s launch by Reuters noted that key assertions could not be independently veri ed.

e gap between claim and proof has been bridged, not by evidence, but by repetition and emotional theatre. e myth of the “savage rapist” justi ed lynchings in the American South. Fanon saw it clearly: “ e colonist fabricates the colonised like a monster he must slay.”

e expression of views that are unpopular, controversial, provocative or cause o ence does not, if lawful, constitute grounds for the refusal or cancellation of an event or an invited speaker.”

LSE’s own Middle East Centre declined to host it, and many academics from Gender Studies refused to chair or serve as discussants also refused. When these scholars declined involvement, management allegedly pressed the Centre to relent, then shi ed the event to the School’s Communications team. It is alleged that senior management repeatedly encouraged the Centre to reconsider despite sta objections about the report’s credibility and optics. No academic department or research unit was associated with it.

e report’s core claims face serious evidentiary hurdles. e UN Commission of Inquiry said it could not verify several speci c allegations and

academics wish to put on. e expression of views that are unpopular, controversial, provocative or cause o ence does not, if lawful, constitute grounds for the refusal or cancellation of an event or an invited speaker. e spokesperson also said that this event was organised by a group of academics; it was not hosted by the School’s Communications team. Nor was it moved to a “communications back room”.

Susan Sontag warned that compassion without action withers; this is worse, compassion repurposed as cover re.

e department most uent in feminist analysis refused to lend its name to this distortion.

Here, the fabrication is institutional. It borrows the vocabulary of human rights whilst hollowing it out.

Picture the meeting: administrators murmuring about “balance” while ignoring every scholar quali ed to judge the evidence. ey speak the grammar of procedure: minutes, memos, reputational risk, where morality becomes a rounding error. A school that advertises a “space for all perspectives” quietly moved this one o the calendar and into a communications back room; that is not neutrality. An LSE spokesperson said this was an academic-led event. It is incorrect to suggest it was initiated by any “administrators”. Likewise, in line with the statement above, LSE has a legal duty to enable events that

Across the sector, the choreography is now familiar: statements on “community” and “respect”, a gestural meeting or two, then legal notices, fencing, and a possession order. Oxford had arrests and fences. Cambridge now has court-drawn protest maps. UCL won summary possession; Birmingham, Nottingham, and Queen Mary followed suit, the last clearing tents with baili s. e result is not scholarly scrutiny but administrative erasure: the protest disappears, the investments remain, and the university congratulates itself on neutrality. Many of 30 campus encampments were removed in the summer of 2024, many through court orders, while numerous Palestine-related events were cancelled or postponed “for safety reasons” under the new IHRA-aligned policies.

Since adopting the IHRA denition of antisemitism, universities have treated discussions of Zionism as reputational hazards. “Safety” and “balance” have become the vocabulary of avoidance.

Particularly obscene is how this report hijacks feminist language, even as well-documented evidence shows Israeli forces employing sexual violence. e Dinah Project ips that script, casting the occupier as protector and the occupied as predator. e pattern repeats: feminism as ag, not conviction.

What drives LSE’s persistence is not malice but timidity — a dangerous vice. Founded by the Webbs and George Bernard Shaw to champion reason and equality, the School now hides behind the sophistries they once lampooned.

From Rhodesia House marches to anti-apartheid divestment, LSE’s conscience once faced outward; today it faces Legal and Comms. A university that once de ned dissent now consults branding guidelines before exercising it. According to UNESCO, more than 600,000 students in Gaza have been le without functioning schools or universities.

sity, Al-Azhar University and the University of Palestine were among those levelled by airstrikes, memorials to what UNESCO has described as an assault on knowledge itself.

“Hosting that event was not an act of openness; it was an act of sanitation deferred.”

Hosting that event was not an act of openness; it was an act of sanitation deferred. e right to speak nonsense does not include the right to do so under institutional endorsement. However, an LSE spokesperson stated that, as per its policy, LSE does not “endorse” speakers or views at our events, and the above statement is incorrect.

Karl Popper warned that tolerance, if extended to those who despise reason itself, becomes a weapon against the very freedom it protects. A university cannot be neutral between knowledge and propaganda; to host what is known to be false is not tolerance but dereliction.

LSE scholars have themselves written about “scholasticide” and the techniques of genocide denial. Gaza’s Islamic Univer-

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Health, more than 67,000 people have been killed in Gaza since 2023. Every university in the territory has suffered catastrophic damage in the name of self-defence. If this sounds bombastic, remember that ideas, like ordnance, have trajectories. When universities sanctify falsehood, the fallout lands far from campus. Propaganda does not stay in lecture halls; it travels to parliaments, to courts, to battle elds.

e martyrs of free thought, from Giordano Bruno to Shireen Abu Akleh, the Palestinian journalist killed in 2022, knew that truth demands its defenders. e Dinah Project will fade, as do all such cheap documents. What remains to be seen is whether LSE chooses to stand among the defenders of truth or among its temporary landlords. If none of its stewards will risk a career to say so, the students must — the unreasonable ones who still believe the university exists not to atter power but to confront it.

(Continued on next page)

Because if neutrality becomes the new virtue, the next atrocity may march in wearing a university crest.

e Dinah Project was contacted for comment but did not reply.

“Freedom of academic enquiry, thought, and speech underpins everything we do at LSE. Our Code of Practice on Free Speech is designed to protect and promote lawful freedom of expression on

campus, including the right to peacefully protest.”

“ is is enshrined in UK law by the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, to which LSE has an obligation to adhere.”

“ e Act includes a legal duty to secure and promote freedom of speech within the law as well as academic freedom for faculty. If an academic wants to host an event, showcase research, or enable other forms of engagement for the free and frank exchange of views lawfully, we must seek

to assist them to the best of our ability while ensuring our health and safety responsibilities.”

“A range of events happen at LSE each day, covering many viewpoints and positions, including on controversial current issues. LSE does not, however, endorse speakers or views at our events. As outlined on every LSE event listing online: ‘LSE holds a wide range of events, covering many of the most controversial issues of the day, and speakers at our events may express views that cause o ence. e views expressed

by speakers at LSE events do not re ect the position or views of the London School of Economics and Political Science.’”

“ e event to which the author refers was organised by a group of academics from di erent departments. It was not hosted by LSE Communications nor was it moved into a back room. It was a ticketed event and took place in a lecture theatre in the CKK building. It was chaired by an LSE academic and featured a Q&A session with the audience a$er the main lecture.”

“As an institution, LSE does not take a formal position on political or international matters. Instead, we aim to provide a platform to enable discussions and critical debates, within the law, where the views of all parties are treated with respect. is includes the expression of views that are unpopular, provocative, or cause upset, as long as they are not unlawful.”

Angelica Di Monte

Contributing Writer

April Yang

Illustrator

As yet more franchise titles hit the big screen, Hollywood proves once more that it has killed creativity to turn it into a corporate marketing strategy.

e Little Mermaid (2023), Moana 2 (2024), Despicable Me 4 (2024), Mufasa: e Lion King (2024), e Conjuring: Last Rites (2025), Freakier Friday (2025), Mission: Impossible — e Final Reckoning (2025).

It is not an original take if I say that Hollywood has run out of ideas. In recent years, it’s become increasingly di%cult to &nd an original blockbuster. Most new releases seem to be a reboot, a sequel/prequel, a live-action remake of an animated classic, or a cinematic universe expansion of a wellknown franchise. e titles cited above are only a few of the ones that have been released in the last couple of years.

While arguing that the current Hollywood industry merely rests on sequels or reboots would be false and reductive, the question still stands: why is Hollywood recycling its own past now more than ever? We could justify it as a risk-mitigation strategy and blame greedy studios that prefer to stick to

what is “safe” and pro&table. But that doesn’t explain why the same movies keep being remade and why it works. What if we looked at the other side of the coin to explain why this is happening? Perhaps the roots of the crisis go much deeper, beyond &lm or Hollywood.

Major studios, like Disney, have learned that nostalgia provides a reliable emotional return on investment, and know that audiences will turn to familiar stories for comfort, leading to the capitalisation on longing.

en why is nostalgia so pro"table? And why are we so nostalgic?

e explanation for our nostalgia-driven culture lies in our own fragmented lives and our struggle to navigate an overload of information. We live in a digitalised era that is fastpaced and ooded with social media algorithms with an easy access to endless information, leaving us having to process an overwhelming array of information all at once. We watch movies while scrolling on Instagram reels on a smaller screen, we shi$ through multiple tabs during lectures and scroll through our lives in 15-second clips. When we go on social media, we seek a

sense of connection and go on an endless quest to piece fragments of our identity together in search of authenticity and meaning, which only results in a sense of anxiety, identity crisis and disconnection from reality. When everything moves so quickly, it is nearly impossible to &nd anchorage, and to construct an identity with something so volatile and ever-changing. erefore, when nothing is solid, we cling to nostalgia for stability. How we consume media in an algorithmic culture is also part of the blame. Streaming platforms have trained us to prefer familiarity and to emotionally recycle and rewatch content.

is psychological and social condition ends up being reected in Hollywood cinema, which has become an industry that can no longer create without referencing itself.

Audiences have always sought comfort and escapism from the anxiety of everyday life; this is not new. What is new is Hollywood’s realisation that familiarity sells. When you spend hundreds of millions on a blockbuster, you want a guaranteed audience, which nostalgia gives. A sequel to the Indiana Jones franchise, i.e. Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023) is a guarantee that

the audience will exist. Gareth Edwards, director of the new Jurassic World &lm, Jurassic World: Rebirth (2025), told BBC’s Front Row that he was trying “to make it nostalgic. e goal was that it should feel like Universal Studios went into their vaults and found a reel of &lm, brushed the dust o and it said 'Jurassic World: Rebirth'.” Studios know that audiences will show up for the emotional familiarity of a story they already love.

e issue with all this creative recycling is that &lms become capitalist products served as comfort food, where storylines lack substance and characters are underwritten. When every franchise is milked for the success it has had in the past, emotional stakes vanish and Hollywood turns into a vat of reprocessed nostalgia. For instance, Disney’s 2019 e Lion King remake replicates every frame of the 1994 original, except that hand-drawn animation is replaced by sterile, photorealistic CGI.

Unfortunately, this continues to work because Hollywood’s

over-commercial, pro&t-maximising, risk-averse machine of entertainment production is compatible in a world where everyone is exhausted from information overload, and where audiences crave and will buy the safety of the familiar rather than seeing something new.

However, not all is lost. Creativity still thrives in independent and international cinema, and even Hollywood itself is not limited to its remakes and sequels and has so much more to o er beyond that. Not even all Hollywood sequels or remakes are devoid of creativity and not all franchise &lms are emotionally hollow. However, while nostalgia is comforting, it is in&nitely recyclable and its exploitation by Hollywood is becoming boring. As audiences, we can choose where to direct our attention and money. If we want cinema to be as valuable as it once was, we need to stop rewarding corporations for repackaging our memories and start paying more attention to those who create something new. Art should ultimately make us feel something.

Ethan Sell Contributing Writer

The ideology of Trumpism has dominated American political discourse for the past decade. Closely adjacent to MAGA and America First, it represents an economically conservative, anti-globalist, and populist political framework. It promises to reduce wasteful government spending, restore America’s industrial greatness, and to liberate the working-class American from ‘liberal elites’. However, Trump’s policies prove to harm those who support him the most — those in de-industrialised cities, rural areas, and manufacturing. Such tension, I propose, is irreconcilable with the common Marxist-inspired approach to Trumpism that is frequently heard in modern political discourse: the idea that ideology is false consciousness and that Trump supporters are merely deceived about their interests and need correcting with facts. Instead, $i%ek’s view of ideology of not masking reality, but structuring reality itself, is much more apt. Consequently, we must rethink the way we conduct political discourse.

"Trump’s policies prove to harm those who support him the most — those in de-industrialised cities, rural areas, and manufacturing."

US counties with the biggest growth in Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) since 2008 voted for Trump in 2024.

MAGA persists in popularity despite this tension. While Trump's approval ratings have declined from when he took o ce, they are still high enough to raise eyebrows.

As of August 2025...

85%

of Trump's 2024 voters continue to approve of his job performance.

ough this is a decline from 95% at the beginning of his term, it is still a substantive majority. Further, Trump sustains an 81% approval rating on his tari s amongst his 2024 voters, and while rural support has indeed declined (59% in February 2025 to 46% in May 2025), it is still of a sizable amount.

Investigating tari s and healthcare cuts, Trump’s April tari s caused an immediate loss of 14,000 manufacturing jobs, which could increase factory costs anywhere from 2% to 4.5%, and are on track to cost the typical American household an average of $2,400 per year. Trump’s Medicaid cuts impacted Republicans and rural Americans the most: 23% of rural Americans are insured by Medicaid, higher than the average 19%, and more than two-thirds of the nearly 300

sis of social reality – the trauma of the impossibility of an ordered, harmonious society. Ideology is not a set of mental states, it is a set of actions; belief comes a&er to support the system established by the ideology. Underpinning ideology is the ‘Real’, which can be understood as the traumatic, impossible kernel that resists symbolisation. Ideology is what imposes order upon the world, meaning that we are still able to navigate the world, just via an imposed symbolic reality.

" e solution is not to deconstruct ideologies, it is to replace them. What works is constructing a rival ideology that makes people feel as though they are being listened to in the same way that Trumpism does, but is ultimately more bene"cial."

is pre-theoretical, it is also unfalsi'able, meaning that there is nothing that can be said to challenge it.

Now, we have a paradox. According to the common, Marxist-inspired conception of ideology, the coexistence of support and contradictions in Trumpism shouldn’t stand, unless supporters were unaware of the facts. But supporters are not unaware of the facts. 68% of Americans believe that tari s increase prices, and 44% of Republicans acknowledge that they will hurt the economy in the short term. Contradictions within Trump’s policy have been widely reported by NBC News, e Washington Post, and e New York Times.

For $i%ek, ideology is not what we believe; rather, it is what makes reality itself understandable. at is, it conceals the deep antagonism at the ba-

e ideology is not de'ned by beliefs such as ‘tari s will restore American manufacturing’, or even more general ones such as ‘Trump will make my life better’. Instead, the ideology is characterised by deeper narrative structures that, amongst other things, appeal to an idea of the lost greatness of America that was stolen by the liberal elites. According to this reading, ideology takes on a quasi-mythical character — which in the case of Trumpism, is deeply nostalgic. As such, contradictions in Trump’s policies lose the majority of their weight. While they might challenge speci'c beliefs, these beliefs are not what constitute the ideology. Rather, beliefs are constructed as consequences of the ideological fantasy. e fantasy itself is safe from contradictions; immanent critique (contradictions and antagonisms in Trump’s policy) cannot rebut the fantasy as the fantasy structures reality itself, so all these arguments operate within the fantasy’s framework rather than challenging the framework itself. I contend that this can be seen in how Trump supporters defend Trumpism against various criticisms: they o&en claim that continued economic hardship is a result of the deep state working against Trump, or an initial phase in a wider plan. Since the fantasy

"It is like trying to harm a ghost by punching it: there is a di erence in the level on which each thing operates."

erefore, the approach to criticising Trumpism that favours fact-motivated observation of the antagonisms and contradictions in his policy is ine ectual, because there is an asymmetry in the mechanism of critique and of defence. It is like trying to harm a ghost by punching it: there is a di erence in the level on which each thing operates. e consistent failure of mainstream Democrats to defeat Trump, and a wider failure of the political centre to defeat Trumpism-adjacent ideologies (Reform UK and AfD, for example), is clear evidence. erefore, the solution is not to deconstruct ideologies, it is to replace them. Obviously, there are some ideologies that carry more harm with their implications than others — compare Nazism to Liberalism or Stalinism to New Labour. us, the goal is to establish ideologies which promote the general good. ere

are already hints that such an approach is e ective against right-wing populism. Zohran Mamdani winning the Democratic primary for the New York City mayoral election and the buzz of excitement around Zack Polanski, the new leader of the Green Party, re(ects that what works is not an immanent critique of the opposing ideology. What works is constructing a rival ideology that makes people feel as though they are being listened to in the same way that Trumpism does, but is ultimately more bene'cial for all.

“Ask yourself, ‘are these the people I want to surround myself with?’”

“To me, networking only really works if you have a connection with someone […] you need to authentically care about what someone does.” And it goes both ways —

age and carve out these opportunities for yourself. “Confdence is something that’s built,” she responds. She underscores the importance of having a goal in mind when attending a networking event, but dispels the valorisation of simply showing up.

I asked Kai what it means to fnd the cour-

On behalf of all uncertain LSE students,

“Art is such a long career that you can build it alongside your other careers,” and gain clarity through varying -experi ences to realise the exact path you want to take.

But the benefts lie in its elasticity:

“There’s no right way of doing things,” Kai laments, “and because the industry is so big, you need to fnd where the gap is”.

On self-fulflment and the future

When I brought up her feature on ELLE — somehow not even in the top 3 of her accomplishments — Kai showed me her Ho bonichi planner, where she had listed wanting to be on the magazine under a page titled ‘100 goals’.

It was almost like a divine feat of manifestation, though it’s clear that passion and persistence have led her to where she is right now. So, where to from here?

She acknowledges the intense expectation to fnd a job upon graduation and paints a more optimistic perspective. “It defnitely comes with privilege, to be able to have the time to fgure it out, but I think parents can be supportive because the economic situations have changed. […] As long as you can sustain yourself, take care of yourself, and not become a burden to other people, then you’re ok.”

Going to Europe for the frst time also meant seizing new -opportuni ties — “It made sense to go from LA to Tokyo to London. They’re big cities and places that are really supportive of the arts.”

“LSE was the most practical and most versatile [option]. I could turn it into whatever I wanted to study.”

“part-time job”. Even still, she remains grateful for studying in London.

Kai comments that pursuing academia did not inherently stife her art career, -of ten describing her master’s degree as a

the beaver in the room

Kai interrogates her desire to stride upwards. Ventures such as appearing in Forbes may seem glamorous, but “capi talism works because it keeps feeding people ideas of what they think they should want.”

Ultimately, she seeks to continue to make meaningful art and give back to the community. She speculates that this may not just come in the form of bringing her ‘Everyday Toast’ exhibition to Lon don, but also conquering new horizons wherever she goes.

Whether engaging in LSE societies, pod casting, rapping, modelling, or voice acting, she states, “my audience thrives when I’m thriving.”

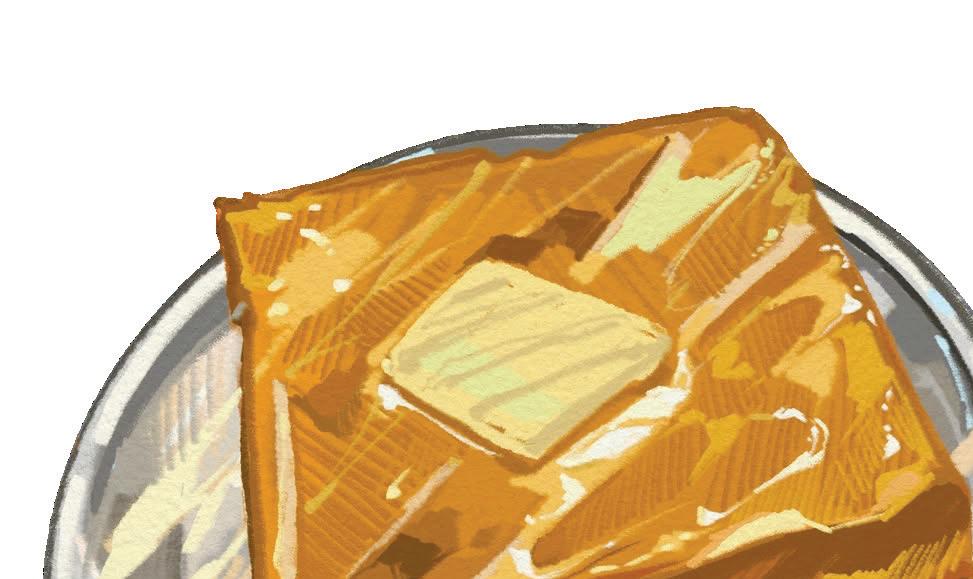

ing about Bourdieu for her Master’s in Culture and Society. Or perhaps you know her best online on yet another side quest under the alias ‘Nomkakaii’.

Most simply, Kai is a food illustrator: memorialising the tantalising dishes she eats through digital art. But she is also a creative director, model, and edi-

Having grown up across four different cities, with London being her ffth, Kai rarely gets homesick, often seeking out comfort food and community as remedies. “If it happens, like if I miss my mom, then I’ll call my mom”.

“Things only blew up for me after Kai recalled, -re fecting on how she had channeled all her energy into content -crea tion after an internship -opportu nity fell through. Marking a new beginning by bleaching her hair — the visual antithesis to corporate life — content became her escape.

“It’s hard to keep projects going […] if it doesn’t have meaning or doesn’t tie into that community as pect. Being able to talk to people that own cafés and involve them in the [crea tive] process, having pop-ups in these places, and giving back through events like that really made me feel like my art was not just stagnant, but something that keeps growing.”

“I started doing toast drawings because I understood how hard it was to run a café… [My art] turned into an […] ar chive project of wanting to document these places and give them expo sure, hoping that it connects to someone.”

It is a vehicle for conversation and story telling; indeed, her own work was birthed from celebrating the hospitality industry.

“When you start out, you have these art inspirations, but then when you start getting the hang of what you do, you start looking outside of the art space in general.”

On what motivates her art

Labelling her profession

Professionally, Kai best identifes as a ‘Slasher’ — someone who takes on multiple careers rather than sticking to one.

Resonating with this term came organi cally: while restless between graduation and fnding a summer internship, she stumbled upon Mill MILK’s interview with travel in fuencer Victoria Yeung (@travelmomentss) discussing her multihyphenate lifestyle as a lawyer and inn-owner. With various skills and hobbies under her belt that she did not want to forgo, Kai “was inspired by [Victo ria’s] life to make it work”.

One moment she’s rendering egg yolk melting invitingly into smoked salmon;

another moment she’s posed on ELLE-Men;

another moment she’s dancing onstage along with the K-pop girl group Aespa.

When I frst met up with her for a cof fee chat, the conversation derailed into discussing her latest collaboration with Genki Sushi and our fond memories of the chain growing up. And as I write this, she recently made her Malaysian debut with Ink ling Studio in publishing a zine about being a Slasher.

“My adrenaline shots come from projects,” she admits.

On being a ‘content creator’

With a mindset of maintaining authenticity, ‘infuencing’ was not a conscious goal she had when posting on Instagram. “It’s the place to be for art,” Kai says, praising the platform’s primary visual focus.

She refects on her viral ‘Everyday Toast’ series, an ongoing compilation of toast drawings. “I was posting for myself just to get better at Procreate” — the humble origins of a daily challenge which has since catapulted into an exhibition at Ztoryhome last summer.

Her account incorporates video diaries that refect on these very opportunities, striving to inspire confdence in viewers through her artistic journey with the same vigour as a K-pop idol.

“I was attracted to [the idea of being an idol] because there was so much variation, and that’s what I want to do with my career, […] becoming this kind of one-stop shop for everyone. If you’re looking for motivation, aesthetics, inspiration, or fashion, it’s there.”

EDITED BY EMERSON LAM & HARRY ROBERTS

Written by CASPER FONG

Equipment maintenance and repair rarely make headlines, but without them, the quality and consistency top athletes rely on and need to perform at the top level would fall apart.

As someone who came to London from China three years ago, I have been able to experience the importance of the sports maintenance industry "rsthand, and have even become deeply engaged in the "eld. While badminton has only been part of my life for a few years, I’ve grown to love it deeply and have even considered a potential career in it, albeit not as an athlete, but as part of the ever-expanding supporting sta that professional badminton requires.

One of the most jarring di erences between badminton in the UK and China is the drastic di erence in cost. !is refers not only to the cost of hiring courts, but also to the fees required to service rackets, mainly in terms of the labour cost for stringing. While a one-time fee of £10 per stringing for labour wasn’t much at a glance, the cost would quickly accumulate considering the frequency with which I needed to restring my racket, along with factoring in the cost of the string itself as a raw material. is inspired me to think about acquiring a stringing machine, not only helping to save money in the long run, but also presenting itself as an excellent business opportunity in a relatively unexplored market.

I began my journey through research

Written by EMERSON LAM

Illustrated by LAURA LIU

You don't exactly come to the UK for baseball.

When I asked people if they knew that LSE had a baseball society, the usual reaction was a surprised, "Oh, I didn't know, that's pretty cool!" !at makes sense: though there is a British Baseball Federation, the sport doesn't have the same cultural presence that you "nd in places like the US or Japan. As a big baseball fan myself, I was pretty disappointed last year when I went to the sports fair and came up empty. So, when I saw that a baseball society was "nally starting this year, I had to go and check it out.

Attending the "rst-ever LSE Baseball training session, I found myself going over the basics, such as how to swing a bat and catch a ball. It was de"nitely a bit mundane at "rst, but so is the basics of every sport: you've got to start somewhere, especially when most participants are picking up the sport for the very "rst time. Of course, we ran into the classic beginner's problem: the gear. !e metal bats were a bit worse for wear a er a few solid hits, and

into how stringing machines actually work, comparing di erent manufacturers, and whether it would work out "nancially over time.

While many entry-level stringers seemed to prefer “drop-weight systems”, which used gravity to pull the string to the desired tension, I thought that investing in an electronic system would give me greater accuracy and save me time. To explain the operation of a badminton stringing machine in layman’s terms, the racket is mounted on a six-point racket mount, which gives it stability, and the string gets pulled through the racket horizontally and vertically by either drop-weights, manual cranks, or electronic tension heads before getting knotted o to complete the process. My machine, which is identical to most high-end commercial use machines, is able to do the tensioning process through a panel where the user can set the tension, and the tension head automatically pulls the string to the needed tension.

Since I rst started stringing in November of 2024, I’ve worked on roughly 400 rackets, allowing me to break even and make pro"t. I was able to learn rapidly through various online tutorials from experienced stringers, as well as learning hands-on from the various stringers I’ve known from China. I was able to further increase my experience in this "eld by working for the stringing team as a part-time stringer for Central Sports, one of the largest badminton equipment distributors in the UK. !e process of learning this trade has enabled me to engage in a new life skill — acting as a good way to bring in some spare change on the side, meet new people, work at sporting events, and on a side note, is rather therapeutic considering you can be in front of the machine for hours at a time weaving patterns!

To learn more about his business, check out his Instagram:

"nding a glove that would "t just right was a challenge. But, in a way, that just made it more impressive that the society managed to get o the ground.

It’s not a simple sport to pick up, but the society is making it work.

A er the session, I caught up with Soomin, the President and co-founder. I’ve known him, Eldon (the Vice-President), and Marc (the Treasurer) since I joined LSE last year, so I was curious about what drove them to start the society.

Written by SHREYA GUPTA

As a ex-competitive swimmer, I’ve always been fascinated by the sport’s ability to represent more than just physical endurance or speed. Swimming, for me, has always symbolised control — a rare, almost meditative form of order in a world that o en feels chaotic. !at’s what struck me most when I "rst watched e Swimmers on Net ix, now one of my favourite true story "lms.

!e "lm, made with the assistance of the real Yusra and Sara Mardini for authenticity, tells their remarkable journey from the swimming pools of Damascus to the open waters of the Aegean Sea and, "nally, to the Olympic stage. But e Swimmers isn’t simply a story about athletic triumph or survival: it’s a study of how swimming becomes a tool of control and self-determination amid the uncontrollable turmoil of war and displacement.

At the start of the lm, Yusra’s dream of becoming an Olympic swimmer feels impossibly distant. Once a rising star in Syria’s national team, she becomes “nationless” overnight. !e Olympics — an arena where athletes carry the pride of their nations — suddenly seems closed to her. !e "lm forces us to confront a question we rarely ask: what happens when an athlete no longer has a nation to compete for?

!e creation of the Refugee Olympic Team at the 2016 Rio Games, which Yusra later joined, was a historic moment for both sport and global politics. It was introduced by the International Olympic Committee, marking the "rst time stateless athletes could compete under the Olympic ag. !is represented not only inclusion but also recognition, making it a symbolic moment where sport transcended national borders. In that sense, Yusra’s participation carried a message far beyond competition: that athletic identity can exist without a nation, and that the pool itself can become a form of belonging.

Yet, in the "lm, her initial reluctance to compete under the refugee ag reveals how deeply identity and belonging are tied to national representation.

It’s only through her sister Sara’s words of encouragement (“Swim for us all”), that Yusra accepts her new role. !roughout the "lm, swimming becomes the one realm Yusra can control, in stark contrast to the instability of war-torn Syria. “Swimming is home for me,” she says in one of the "lm’s most poignant moments. “It’s where I belong.” In that line, the pool becomes a sanctuary — a place untouched by politics. One of the most striking scenes shows the sisters walking through their neighbourhood in Damascus, passing a wall gra tied with the words: “Your planes can’t bomb our dreams.” It’s a haunting reminder that, even amid destruction, ambition and identity survive. For Yusra, the very act of swimming becomes de"ance — a rhythm of control against the chaos of war. By the time she reaches Germany, helped by a generous coach and Sara’s unwavering belief, her discipline and skill carries her from refugee camps to the Olympic pool. !is is further emphasized by the inclusion of Sia’s Unstoppable and Titanium in the soundtrack — songs that perfectly capture her transformation from survivor to athlete, from powerless to powerful.

As someone who’s spent countless hours staring at the black line on the pool oor, I understand that calm she "nds. In swimming, your world narrows to the sound of your breath and the precise rhythm of your stroke. e outside noise fades. I adore the "lm’s cinematography, mirroring this internal world beautifully. !e slow-motion bubbles, Yusra’s dive into the race, and the mu ed cheers surrounding her. Every swimmer can relate to these sensations before a race begins.

It’s not just a competitive discipline de"ned by split seconds and technique, but a life skill, a means of survival, and ultimately, a form of freedom. !e "lm turns the act of swimming into something deeply human: a way of reclaiming control when everything else is uncertain. !rough Yusra’s story, we see that swimming can carry you through both literal and metaphorical waters — from saving lives to chasing dreams. By blending the physical with the political, e Swimmers transforms swimming from a sport into a language of endurance and belonging.

e Swimmers captures something few sports "lms achieve — the full spectrum of what swimming can represent.

As Soomin put it,

“ With all three of us having played baseball for more than seven years, when we found out that there wasn’t a LSE Baseball Society, we became determined to start one."

With a long-term goal of building up a team that is able to compete, the club aims to build up the foundation of baseball at the university in this "rst year, buying essential equipment and creating networks with other universities for friendly matches. In particular, multiple matches have already been set up with the UCL Baseball Society, creating a strong network between the two universities that will hopefully help both teams improve.

At the end of the day, baseball is just a really fun sport that has a way of creating unforgettable, rewarding moments that just stick with you.

Follow the LSE Baseball Society's Instagram here:

EDITED BY AMELIA HANCOCK & AASHI BAINS

Written by SHIVANGI SHAH

Between lectures, ca!eine runs (aka waiting in line at Blank Street), and pretending to study in the Marshall Building, nding the right food makes or breaks the lock-in. Luckily, I can suggest a few ideas to switch up your current go-to food spots. Here are my two favourite restaurant options near campus, plus a bonus dessert spot.

Eat Tokyo

If you love Japanese food, why aren’t you already here? Right by campus, Eat Tokyo is that rare mix of a!ordable, reliable, and genuinely delicious. e sushi’s fresh, the portions generous, and it somehow always hits exactly right a er a long seminar. You’ll end up here more o en than you think, and honestly, that’s not a bad thing.

Despite wanting to gatekeep this place, it is just too good not to share! Fancy enough for a date, but with a student discount on the regular menu, ai Square o!ers affordable lunch, set, and theatre menus. Every dish is perfectly seasoned: rich in %avour, sometimes spicy, always comforting, and addictive in that “I can’t believe this is ve minutes from class” way. It’s become my go-to for both late lunches and “I deserve this” dinners. Go once, and you’ll understand why I’m obsessed.

Chin Chin (Bonus Dessert Pick!)