By Sylvain Chan, Multimedia Editor

By Sylvain Chan, Multimedia Editor

Executive Editor

Janset An executive.beaver@lsesu.org

Managing Editor

Oona de Carvalho managing.beaver@lsesu.org

Flipside Editor

Emma Do editor. ipside@lsesu.org

Frontside Editor

Suchita epkanjana editor.beaver@lsesu.org

Multimedia Editor

Sylvain Chan multimedia.beaver@lsesu.org

News Editors

Melissa Limani

Saira Afzal

Features Editors

Liza Chernobay

Mahliqa Ali

Opinion Editors

Lucas Ngai

Aaina Saini

Review Editors

Arushi Aditi

William Goltz

Part B Editor

Jessica-May Cox

Social Editors

Sophia-Ines Klein

Jennifer Lau

Sport Editors

Skye Slatcher

Jo Weiss

Illustration Heads

Francesca Corno

Paavas Bansal

Photography Heads

Celine Estebe

Ryan Lee

Podcast Editor

Laila Gauhar

Website Editor

Rebecca Stanton

Social Secretary

Sahana Rudra

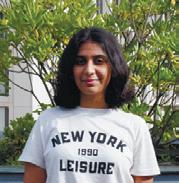

Janset An Executive Editor

The time currently is 7.30pm on a Sunday, I am writing this from the Media Centre. I woke up at 5.30am today to do my coursework due tomorrow and an internship application due in a few hours. I am struggling to keep my eyes open, so please accept my sincerest apologies if what you are about to read is not profound.

You are holding the eighth and nal issue of e Beaver for the academic year 2024/2025. I feel so proud that we have nally made it here. It really has been, at times, a challenging journey full of endless meetings, formatting on weekends, back and forth with the SU and

Media Relations, and creative con icts… but I would do it all again with no doubt whatsoever. In fact, I love this long-hour, uno cial but technically o cial, part-time, non-paying job so much that I will be in this position again next year.

So, why have I opted to do this again?

e Beaver is not just a ‘newspaper’. It is a support system. e Beaver is a space for you to use and to develop yourself in whatever avenue you wish, whether it’s editing, writing, photography, podcasting, illustrating, social media, videography, or interviewing–there is a place for every LSE student.

Oona de Carvalho Managing Editor

Like other nal-year students, I am nishing my last classes at LSE this week. Graduation slowly approaches and it is all starting to feel slightly surreal. For the rst time in a long time, I swim in uncertainty as I do not yet know what I’ll do, or where I’ll be, a er I walk across the Peacock eatre stage in July.

e questions of what next, and where to from here, have been preoccupying me a lot lately. Especially considering how at an institution such as LSE, having a clear, set career path and graduate job lined up is the rule and not the exception. Not having everything gured out yet can at times feel overwhelming.

However, it is foremost

exciting. I nd so much comfort in knowing that my future remains open with possibilities and take pleasure in imagining the di erent trajectories that my life can take. As much as I have enjoyed my years at LSE, I look forward to experiencing change and novelty.

ough of course, it is all very bittersweet. I o en catch myself prematurely reminiscing about the small, ordinary things that have made up my time at this university and in this city.

I remember when I rst entered the Media Centre in the fall of 2022 for a copyeditors’ meeting, eager to get involved with e Beaver’s community. I remember the rst news article I pitched and the thrill that followed as I chased interviews, dra ed and

Last year, when I took my rst steps in this role, I was clueless, struggling to even understand the concept of ‘formatting’. A year on, however, I have thus far managed to somehow prevent the newspaper from getting sued, and I have, in fact, learned how to do a textbox on InDesign :)

All jokes aside, except for the obvious CV-sprucing skills I have garnered from this job, what has made me fall in love with e Beaver and reluctant to let go of it just yet are the people that I have worked with. I have made memories with the Ed Board, my Exec gals, and LooSE TV that I’ll carry with me long a er graduation. ey have taught me, challenged me,

and moulded me into a better editor and writer. But more fundamentally, they have given me the con dence to believe that I can do this all again.

In closing, here’s my message to prospective Beaver members: Get involved! I can assure you from personal experience that it will be the highlight of your university experience.

I am so excited to see how this newspaper will grow next year and what new projects will be pursued. I promise I’m going to get us an app…

Best of luck for your exams; stay positive, and see you all in September <3

re-dra ed, and saw the nal piece come together in print.

And now, sentimentally, I am sitting in the same spot (though on a refurbished chair) as I write this editorial. I can testify to what many of those who have come before me have said—being a part of e Beaver has been, albeit timeconsuming, one of the most rewarding experiences I have had during my undergraduate studies. It has been so special and gratifying to be able to tell people’s stories and work with a team of editors and writers who pour so much dedication and passion into our paper.

I know that someday I will miss having my calendar structured around our publishing dates and will long for the stretched formatting Sundays in the Media Centre.

Any opinions expressed herein are those of their respective authors and not necessarily those of the LSE Students’ Union or Beaver Editorial Sta

e Beaver is issued under a Creative Commons license. Attribution necessary. Printed at Ili e Print, Cambridge.

Saw Swee Hock Student Centre

LSE Students’ Union

London

WC2A 2AE

020 7955 6705

As I continue my journey beyond the con nes of this university, I rest assured knowing that e Beaver lies in good hands, and I am excited to see how it will evolve and grow under the next editorial team.

Explore e Beaver’s digital archive!

“I am so grateful to the students for re-electing me to be Gen Sec for another year. is year we have had many wins such as tripling the hardship fund, the summer ball, and a new green space on the sixth oor of the SU building. I am delighted to be here for another year to keep leading on transforming LSE and serving the student body. In my next year in this role I am so excited to continue on various projects, such as transforming the Student Salon into a social space with microwaves and hot water taps, ghting for a better LSE experience for black students, and much more! ank you all for the support and if you want to reach out to me for anything feel free to come to the SU o ce or email me at su.generalsecretary@lse.ac.uk”

“I’m really excited to start the role of Activities and Communities O cer at LSE Students’ Union. I’m incredibly grateful to everyone who voted for me and supported me during the campaigning period, and I’m so excited to get started on making activities work for everyone, stamping out the problems at LSE which are dividing our community, and ensuring that everyone is unleashed and empowered so they are free to thrive. ank you once again to everyone who has voted for me!”

“I am beyond grateful to those who supported me in this election. e di culties of campaigning were overcome by the sheer kindness and enthusiasm of students at LSE. is has only boosted my con dence further that students and sta alike welcome progress. I am excited to use this opportunity for change-making and I won’t be taking it for granted.”

“Coming from an underprivileged economic and social background, I know all too well how overwhelming it can be to integrate yourself in and navigate LSE. Yet, I was able to make some of the most incredible memories and participated in opportunities that allowed me to grow into who I am today, all with the help of friends, peers, sta , and mentors I made along the way. eir support was beyond invaluable to me—now I want to be this helping hand for all students at the LSE, no matter what your social or economic background. I will be the friend, peer, and mentor that listens to YOUR needs to ensure you leave LSE with a sense of ful lment and pride. With Nooralhoda, no one gets le behind.”

Amy O’Donoghue Staff Writer Photographed by Paavas Bansal

LSE has received national attention over a controversial book launch entitled ‘Understanding Hamas And Why at Matters’, hosted by LSE’s Middle East Centre on 10 March 2025. e event attracted many pro-Israel protesters and pro-Palestine counter-protesters, while police separated the two camps outside the Cheng Kin Ku Building.

e mobilisation began when Zionist group Betar Worldwide posted about the event on X, claiming “these jihadis are destroying our nation” and inviting “all Patriots, all Zionists, all decent people to stop this event”. is gained further traction a er promotion on Instagram by Jewish-led campaign group Stop the Hate. e group LSE Liberated Zone (not a liated with the LSE administration) responded with a call for “emergency mobilisation” to “help us keep our campus safe from farright agitators”.

An online open letter calling for the event to be cancelled received 53,000 signatures.

ere was a large turnout for the protest, which took place outside the Cheng Kin Ku Building where the book launch was being held. A GB News reporter was also present and spoke to protesters; one protester from the pro-Israeli side told the reporter that the fact this event was being held was “shameful” and “shows the decline of universities”. Most protesters from the pro-Palestinian side declined to speak to the GB News reporter.

LSE Liberated Zone claims

endorse the views set out in the book. He also repeatedly stated that anyone in the audience who crosses the line from free speech to extremism would be expelled from the event.

e three co-authors of the book (Helena Cobban, Jeroen Gunning, and Mouin Rabbani) were then given a chance to speak. Cobban stated she was pleased LSE was “upholding values of free speech and free association” by holding this event. She also claimed Hamas has been “systematically mis-

groups such as Hamas when seeking a peace settlement, referencing historic engagement with the IRA as an example of this.

e chair then questioned the authors, announcing his “ethical unease” with the contents of the book, which he claimed mentions the war crimes committed by Hamas only once in its entirety. e authors responded that they did not wish to deny the atrocities committed.

strongly encouraged to discuss and debate the most pressing issues around the world.”

“We host an enormous number of events each year, covering a wide range of viewpoints and positions.”

“We have clear policies in place to ensure the facilitation of debates in these events and enable all members of our community to refute ideas lawfully and to protect individual’s rights to freedom of expression within the law. is is formalised in our Code of Practice on Free Speech and in our Ethics Code.”

Preceding the event, Israeli Ambassador to the UK Tzipi Hotovely wrote to LSE President and Vice-Chancellor Larry Kramer, describing the content of the event as “Hamas propaganda”.

An LSE spokesperson responded to Hotovely, stating that “free speech and freedom of expression underpins everything we do at LSE”, and so the event would go ahead.

e Home O ce also issued a statement, warning LSE that anyone taking part in the event who crosses the legal boundaries of free speech will “face the full force of the law”.

that a pro-Palestinian counter-protester was arrested and later released without charge a er a “baseless accusation” was made against them by a protester from the other side. ey also claim the police “demonstrated their alignment with the Zionist fascist forces” by assaulting protesters who were attempting to speak to the individual that was arrested. e Metropolitan Police did not respond when e Beaver attempted to verify these claims.

Tension continued during the book launch itself. It began with the chair, Michael Mason, emphasising that Hamas is considered a terrorist organisation and that LSE does not

represented in the corporate media” since before the events of October 2023.

Gunning then stated that whilst he does not deny the war crimes that Hamas has committed, he believes that the labelling of them as a terrorist organisation has “devastating e ects” because it obscures historical roots. He also highlighted that the IDF has used the terrorist label to target all Gazans. He claimed the IDF has previously stated that they see no di erence between Hamas and Gaza citizens and that to them, all Gazans are “animals”.

Rabbani added that it is standard practice to engage with

During the Q&A section of the event, a sta member from LSE described the “twisted use” of the term demonisation in relation to Hamas as a “clear attempt to exonerate a terrorist organisation”. A heated exchange between audience members and author Cobban followed, with uproar occurring a er Cobban claimed that most of the October 7 attacks were targeted to military personnel, which the chair immediately disputed. A row of spectators eventually walked out.

An LSE spokesperson said:

“Free speech and freedom of expression underpins everything we do at LSE. Students, sta , and visitors are

“Central to our culture and protected in law is LSE’s responsibility to enable diverse individual views, including the voices of those who wish to peacefully protest. During protests, LSE’s security team work closely with relevant authorities to prioritise the safety of our community and campus.”

“Bullying, harassment or discrimination are not acceptable, and we encourage any students or sta who have witnessed such behaviour to get in touch via one of our many channels, such as Report and Support.”

Daniel Levy, Betar spokesperson, told e Beaver that “Zionists stand strong against hate”. e spokesperson claimed LSE promoted a program with a “friendly depiction of Hamas, which is completely against all British values”. ey also claim LSE “harbours” and “favours” Hamas. e spokesperson alleges that LSE sta made an “attempt to brand Hamas as a political movement”, which would make LSE a “pariah”.

Betar US did not provide any evidence to substantiate their claims.

LSE Liberated Zone did not respond in time for publication.

Iman J. Shaikh

Contributing

Writer

Photographed by Ryan

Lee

In honour of International Women’s Day 2025, LSESU Feminism Society (FemSoc) organised a dedicated Women’s Week, beginning on Monday 3 March. Centred around the theme of ‘Accelerated Action: Resistance and Resilience’, FemSoc, in collaboration with various other societies from the LSE community, coordinated several events and activities open to all, ranging from games nights and craing, to lm screenings and discussion circles, culminating in the ‘Million Women Rise’ rally on Saturday 8 March.

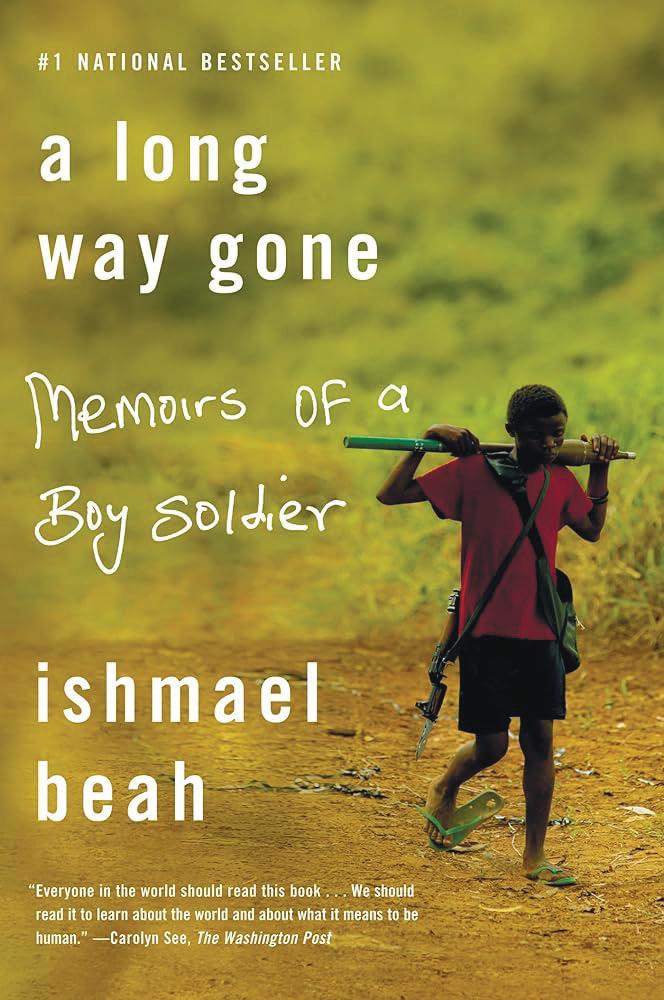

To kick o the week, FemSoc co-hosted a Pilates Workshop with LSESU Pilates, followed by a showing of Smoke Sauna Sisterhood in a special edition of LSESU Film Society’s weekly lm screenings, where members vote on a range of movies to watch grounded in an overarching common theme. at week’s theme was ‘women’.

e following days featured

casual, activity-based social events, including a charity games night aimed at raising funds to tackle menstrual poverty, a Sip ‘n’ Paint session jointly organised with LSESU Cra s Society, and an informal Feminist Discussion Circle on Wednesday evening.

Of particular note was the Ladies’ Self Defence Workshop held at e Venue in collaboration with the LSESU Brazilian Jiu Jitsu Club (BJJ) on ursday 6 March, which e Beaver was invited to attend. A dozen attendees sat intently focused on the workshop facilitator, Mithalina, a nal-year Social Anthropology student.

Having rst ventured into BJJ as a form of self-defence, Mithalina is now in her third year of practising BJJ. “It can feel intimidating, and there still aren’t a lot of girls in the sport,” Mithalina explained, “but there are a lot of misconceptions. BJJ is great for those who are small-framed, as it’s more about grappling than pure striking power.”

Mithalina’s fondness for BJJ is rooted in an appreciation for the sport as an art form, where

unlike other forms of martial arts, one’s strength or mass does not correlate to one’s prociency in the sport—rather, it is one’s technique. Larissa, a student rugby player, commented on her appreciation for BJJ’s ability to bypass these physical barriers that girls may o en face when participating in certain sports.

Another student, Anne, rst attended a ‘Give-It-A-Go’ session held by LSESU BJJ at the beginning of the academic

year. “Boys get into ghts with each other at a young age, but girls will generally avoid being physical,” Anne explained when asked about her motivation for joining BJJ. “My father stressed to me the importance of self-defence and martial arts. It’s a universal skill, it’s not gendered.” Now a BJJ regular, she greatly values the boost in con dence and strength she gained since rst playing in September.

Following the workshop, Fri-

day saw a ‘Show & Tell’ event co-hosted by LSESU’s Literature Society, where attendees could share “artworks, pieces of poetry, literature works, or anything else that resonates with the theme of this week”.

On Saturday, FemSoc joined LSESU LGBTQ+ Society in attending the annual ‘Million Women Rise’ rally to round o a week of nding community and building friendships—the core tenets of accelerating any calls to action.

Suchita Thepkanjana and Sylvain Chan

Frontside Editor and Multimedia Editor

Content Warning: Mentions of Depression and Suicide

On 13 March 2025, e Beaver attended an exclusive screening of the nale of Big Boys, hosted on University Mental Health Day. Big Boys is a Channel 4 comedy series that explores university students’ mental health struggles. e event was held at Regent Street Cinema in collaboration with suicide prevention and mental health charities Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) and Student Minds.

e event featured a panel with the show’s creator Jack Rooke,

cast members Katy Wix and Jon Pointing, and charity representatives Dr Wendy Robinson, Dr Dom ompson, and Taj Donville-Outerbridge. e Beaver had the opportunity to interview Rooke himself and Rosie Tressler OBE, the CEO of Student Minds, about mental health among university students.

Big Boys is a sitcom that follows university students Jack (a semi- ctionalised version of Rooke played by Dylan Llewellyn) and Danny (played by Pointing) whilst they attempt to navigate identity, grief, relationships, and a battle with depression.

Rooke described to e Beaver how the story is essentially “about friendship and

about two boys from very different ends of the spectrum of masculinity…coming together and choosing each other”. Yet there is a constant theme of mental health struggle running through all three seasons of Big Boys, which eventually culminates in a powerful message about awareness, prevention, and support.

“I always knew [Big Boys] was going to lead somewhere whereby it was going to tell a story about young male suicide,” Rooke explains.

“As somebody who’s been bereaved by suicide, [there’s the feeling that] it could have been so di erent so easily. It could have been so di erent if only he had waited to see what potential and what other oppor-

tunities were there.”

“I kept that idea very close to my chest because suicide is still a topic that I think is very complicated for people to talk about,” he says.

e panel discussion spotlighted how university students are o en vulnerable to serious mental health struggles. Dr Robinson, Director of Services at CALM, states that 7,000 young people have ended their lives in the past ten years. Dr ompson, GP and young person’s mental health expert at Student Minds, explains how this can be due to the “pressure” for young people to come into their own and make lots of friends at university. Hence, it can be isolating when these

expectations di er from reality.

Still, Pointing cites how over 80% of survivors of attempted suicide believe it was completely preventable, which is why it is imperative to normalise conversations around suicide and take away the shame holding people back from seeking help.

If you , or someone you know, is struggling with mental health, please reach out to a trusted friend, family member, or professional.

Read the full article online.

Mahliqa Ali Features Editor Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

LSE is o en praised for its diversity. When LSE was ranked rst in e Times University guide earlier this year, Larry Kramer attributed this to our global community of students and faculty. With a student population that is 70% international, the range of countries and experiences that students bring to LSE undeniably makes our campus an enriching cultural melting pot. Yet, diversity has become a buzzword, so reminding ourselves why it matters highlights the need to prioritise it beyond just nationality and culture.

Diversity is important because everyone has a di erent experience, heavily in uenced by factors including race, religion, class, gender, sexuality, neurodivergence, and disability. Diverse spaces featuring representation from across the spectrum of these characteristics enable us to develop empathy for all and learn from those with experiences unlike our own. ere is not one ideal way to live; there are a multitude of values, priorities, and ways of being we can be exposed to when we seriously and genuinely engage with those who are di erent to ourselves.

ere is a signi cant lack of class diversity at LSE, inhibiting our ability to engage with the diversity of experience that makes LSE such a special place.

Zoë is LSESU’s Class Liberation O cer, representing students from working-class, state-school, or care-experienced backgrounds and those who have experienced homelessness. She comes from Darlington, a small town in the North East, attended a stateschool, and grew up on free school meals while living in a single-parent household.

“ ere isn’t enough class diversity,” Zoë explains, attributing it partly to LSE’s demograph-

ics. “ ere’s a large majority of international students, and to sustain their studies, they have to prove that they have a certain amount of wealth.”

She also highlights the dominance of privately educated home students. “Even among state school students, some attended good quality grammar schools. Whereas I went to the worst school in my town, and already the North East is one of the worst places to be educated in the UK, so my standard of state school is di erent.”

is year, Zoë has set up the ‘Working Class Collective’, a social space for working class students, worked with the SU to launch the Kickstart social mobility scheme, and tripled the hardship fund which helps students facing nancial di culty.

Gracie, a third-year Geography student, o ers perspective on the value of the schemes LSE offers for working-class students. Gracie is from Colchester, Essex, which she notes is “generally an area of really low academic progression”. She grew up in a single-parent household and is the rst in her family to attend university. roughout her degree, she has worked as a Widening Participation Student Ambassador and LSE recruitment o ce assistant.

“ ere are some fantastic recruitment programmes that are working. LSE Springboard, LSE rive, Pathways to Banking & Finance, Pathways to Law are targeted towards schools or individuals underrepresented in higher education and LSE.”

“It’s so lovely seeing students grow to become more condent in knowing that higher education or LSE is for them. Of course, some students come onto those programmes and decide actually the subject is not for them, and that’s totally okay. It’s giving them that rst exposure to decide which is helpful,” she adds.

Gracie personally bene tted from the Kickstart scheme. She

had never had a sports membership before due to the cost. rough Kickstart, Gracie was able to access ve societies, one of which was women’s football, where she is now an active member. “It’s so nice to have the SU acknowledge that certain demographics might not have access. ings like this make it a little bit more equal.”

Beyond society participation, how does the working class experience di er from wealthier peers? Gracie highlights the challenges of having to work to cover the rising cost of living.

“ e LSE policy is that you can only work 20 hours a week. I’ve gone beyond that on multiple occasions and it’s due to necessity. I’ve always had a full maintenance loan, the LSE bursary, and sometimes it feels like even those aren’t quite enough.”

“ at funding sustains me, it covers rent, groceries, TFL. But sometimes I’ll do extra work shi s to enjoy the stu others enjoy. If I want an iced matcha latte, I have to work for that. I’m not gonna deprive myself because I deserve to have the same fun. It’s so trivial but these things a ect your whole university experience,” she adds.

While class is primarily dened by nancial capital, working-class students not only have less monetary resources, but also lack the luxury of time.

She also re ects on how this is exacerbated by other factors. “I’m neurodivergent, so I have a brain that needs more time to process, for essays and reading. I already have an academic disadvantage with a learning disability, and then I have to work, so it gives me even less time even though I need more.”

Additionally, many working-class students have to dedicate e ort to familiarise themselves with the educational and career navigation skills that privileged students may have learned from family or school. Gracie explains, “Perhaps my CV even looks a bit messy because I’ve done a consulting

insight programme, then I’ve done a banking workshop. Of course everyone spends time guring out their path, but especially if you’re someone who has no clue because your parents don’t work in these careers, and you didn’t go to a private school where you were told about these things, it takes a lot of time to gure out.”

Wajiha, LSESU’s Education

O cer, who comes from a “low socioeconomic background”, also notes the lack of con dence she had coming to university. “I’m the rst in my family to attend university, so I’ve not had anyone to ask about it growing up. e systemic aspects are sometimes unbearable. Like when you’re writing an essay or struggling to do referencing. Some people were taught how to do that at school. Am I stupid because I don’t know how to do something, or is this actually a manifestation of inequality?”

In contrast, Joe, a History and Politics student, attended a private school in Nottingham and received ample support. “My parents are doctors, so we were always very comfortable when I was

“My school gave me endless, unlimited support. ree different teachers looked through my personal statement and helped me improve it before it got sent o . Our deputy head of sixth form had been an Oxford admissions tutor. My friends applying to medicine had a huge amount of time with teachers, receiving training for months leading up to interviews. e school had real expertise about how to help us get into university.”

Wajiha identi es the role of luck as signi cant in getting her into LSE. “I was part of a small group in my year that was encouraged to aim for the top 10 universities. My head of sixth form helped me, and I wouldn’t have made it here if it wasn’t for him. And that’s pure luck. From my background there were a lot of people not going into higher education.”

Once students get to LSE, how is their experience studying here?

Zoë re ected on the ‘imposter syndrome’ that she felt in classes. “I didn’t speak my entire rst year because I felt so

deeply insecure about the way I sound. I think certain people are able to articulate themselves because they’ve been taught how. I was never taught how to make a convincing argument.”

e term ‘imposter syndrome’ originates from psychologists, describing the doubt people feel about deserving their success in high-achieving environments. Is this an accurate description of people’s experiences? e word ‘syndrome’ implies that the issue lies within the individual’s self-doubt. However, these interviews demonstrate that many of the conditions that facilitate high achievement actually are exclusive to those from privileged backgrounds: there are certain social norms, networks, and opportunities that have not traditionally been accessible for the working class.

Interestingly, the psychologists who coined the term initially labelled it as a phenomenon; this seems more apt for the systemic problem of educational and wealth inequality. Gracie agrees, saying: “Calling it imposter syndrome doesn’t acknowledge the reality of why you feel that way. Rather than saying I’m in a hard class, all my peers are comfortable here, I must be the imposter, I would prefer to say they’ve had certain systemic advantages over me, and I’m working hard to overcome that.”

Joe observed similar patterns in seminars. “In History and Politics, my classes are based on small group discussions then feeding back to the whole class. I notice the same people speak every time. Some people want to talk, some prefer not to, and that’s ne. What’s less acceptable is the way class interacts with that. In school I had small class sizes, and debate was a huge thing, so this is a style of teaching I’m very used to. I have noticed the people who feel comfortable to share are people like me with a more privileged background.”

is issue is particularly pertinent within a social science university where class is o en talked about as a sociological category of analysis. “It’s a reg-

ular frustration going to class and poverty is seen as an abstract thing, an academic concept. I do politics, and we talk about policies to reduce inequality. You can say you disagree with a policy when you’re sitting in class, but for me, if that policy was implemented, that would massively impact my life and the way I’ve grown up, but that wouldn’t mean anything to you. I think we should stop talking about poor people as if they don’t actually exist. And if you don’t have experience with something in a seminar, what’s the need to speak on it?” questions Zoë.

the majority of society, but at LSE, they are a minority. is makes class disparities even more visible and jarring for students from less privileged backgrounds.

Zoë remarks that at LSE, she feels like an anomaly: “It feels like there’s a microscope on my background because it’s so different to the majority of people here. Children shouldn’t have to live in poverty of course, and that shouldn’t be normalised, but it’s a regular thing many people relate to.”

Once students overcome the systemic barriers to enter a

‘ e working class make up the majority of society, but at LSE, they are a minority. is makes class disparities even more visible and jarring for students from less privileged backgrounds.’

Kieran, a Politics and IR graduate, shares this frustration. He explains, “A lot of middle-class people at LSE will spend time in seminars trying to understand the behaviours of working class people as a social scienti c subject. To some extent I’m guilty of this myself as a Political Science student, but my analysis comes from growing up with these communities. ose students will try to explain working class behaviour without knowing people who are actually working class. I think it’s only recently that people have started to consider alternative explanations for working class behaviour other than economic feeling.”

He highlights the failure to acknowledge that working class people are active political agents. “ e traditional narrative of electoral politics is that deprivation is what drives people to vote, but working class people vote on the basis of lots of di erent factors.”

is tendency to analyse the working class as an abstract concept in essays o en translates into students not engaging with the real lived experiences of the working class people around them. Many interviewees noticed the sheer lack of awareness some students had of di ering realities. e working class make up

work to make your immediate material conditions better, but in terms of building generational wealth, these are more exceptions than the rule,” he explains. “Have I achieved social mobility? I will say I’m earning significantly more than the average UK graduate salary and the average salary in my area. Tower Hamlets has a very high bene t recipients rate, lots of unemployment, gig work, and multigenerational households with an elderly population.”

“One of the unfortunate aspects of class in British society is that a key indicator of ‘making it’ is owning property, speci cally to extract value from other working-class people,” adds Arif.

people will recognise my skills,’ but it’s not like that.”

Furthermore, class does not exist in an isolated bubble. Other aspects of identity can confound the e ects of class inequality. Wahija recalls the statistic that 50% of Muslims in the UK live under the poverty line. “A lot of these people are working really hard in care jobs—they’re nurses, careworkers, people who work at home, rst-generation immigrants.”

Arif adds “Many students from a uent backgrounds don’t understand the plight of the British working class. at also feeds into ethnic inequalities where South Asians and Black people are underrepresented.”

high-achieving university, does an LSE degree confer a certain level of social mobility on those who have them? Meritocratic narratives argue that if people work hard, get a good education, and put in e ort to secure a lucrative job, they can ‘work their way out’ of their class situation. How realistic is this for LSE students and graduates?

Arif is an LSE History graduate who lives in Tower Hamlets—one of the most deprived areas in London. He is a second-generation Bangladeshi immigrant and comes from a working-class family. Post-graduation, Arif works at a top nancial rm in the city.

Arif spoke to e Beaver as he walked 15 minutes from his corporate o ce in Canary Wharf to his home in East London. “ e reality of living in this area is literally being stood amongst council estates, against the backdrop of highrise buildings from the city, where billions are coming in and out every day.”

“My ability to succeed was actually due to a lot of DEI programmes. I got to where I am because I was on scholarships, got mentoring from industry leaders, and got lucky with applications. I don’t think meritocracy and social mobility exist. Sure, you can technically

Notably, these students recognised that there was an element of circumstance in addition to their hard work. e myth of meritocracy means many privileged students tend to think that hard work and success have a linear correlation, failing to recognise other factors that contributed to their success.

How do we measure success?

Zoë explains, “I completely understand going to university and wanting to do better, that’s why I’m here.”

“At the same time, I refuse to equate success with the amount of money you earn or being in the corporate world. My mum’s a trained social worker and carer, my dad’s a healthcare assistant, they both work in failing systems, and they both work extremely hard,” she argues.

Wajiha adds that having an LSE degree does not automatically level the playing eld. “I think LSE gives you opportunity, even just the name opens doors. But it’s not the only thing. It’s also knowing how to use your LSE education. Networking, for example, takes years to gure out.”

Kieran highlights the dangers of perpetuating the myth of meritocracy: “I didn’t know what an internship was before coming to LSE, or why it was important. I’ve realised it’s more about having something on your CV as veri cation for your skills. People who believe in meritocracy might think, ‘If I work hard,

Arif has a long-term health condition called Multiple Sclerosis, which requires him to take immunosuppressants. Due to this, he wears a mask in the o ce to prevent illness. He recognises that “as someone who is a graduate, it does a ect my ability to socialise and network. For the most part people are understanding, but the corporate world is a very conservative place, so some of them may have opinions on me masking.”

Class does not only manifest in education and careers—it is also visible in daily interactions. Joe observes reactions to running low on money: “ ere’s a world of di erence between those who text their parents to send them more money, and people who pick up extra work shi s and don’t go out the last week of the month. e attitude of ‘It doesn’t matter if I run out of money, I can just send a text and more money will appear’.”

Of course, no one chooses the family they are born into. e lottery of birth means that we have no say in the privileges we inherit, or the struggles we must navigate. What can be chosen is awareness of the vastly di erent realities that exist beyond our own. In a city where these divides are stark, where just 20 minutes from campus, wealth and struggle exist side by side, acknowledging these di erences is not just about perspective. It becomes a responsibility.

Sebastien Grech

Contributing Writer Illustrated by Paavas Bansal

Last year, a few friends and I did something that, in hindsight, feels very ‘LSE’. We wrote down our ‘module aspirations’ that is, target grades for each course and pinned them to the fridge. It started o as a small accountability trick; something to keep us motivated and engaged with academic work. But for me, those numbers transformed from simple targets into constant reminders of what I ought to achieve. It wasn’t that I consciously thought about them all the time, but their presence increasingly set a tone. Work was no longer something I did on a day-to-day basis, but something I had to justify not doing. Taking a break felt like slacking, and slacking felt like falling behind.

We weren’t the only ones. Ask most LSE students and they will more than likely tell you the same thing. Being busy isn’t just common, it is something expected of you in an ever-increasingly competitive environment, where students are not only judged on academics, but also graduate employment, and the relentless pursuit of ‘doing enough’. But is this culture something that LSE creates, or does the university just attract people who already thrive on overworking?

It’s true that most people hate the feeling of idleness. In a famous psychology experiment conducted by Timothy Wilson, participants were given the choice to push a button to electrically shock themselves, whilst sitting alone in a featureless room without distractions for 15 minutes. Even though every participant initially claimed they would pay to avoid an electric shock, 67% ended up shocking them-

selves. It proved that stillness is uncomfortable. And when ambition is measured by busyness, staying in motion feels safer than pausing to question whether you’re moving forward.

But, in an academic setting, this discomfort isn’t just about boredom—it’s about the constant feeling that you should be doing more. Unlike a job with set working hours, life on campus has no natural stopping point, as there’s always another reading, another problem set, another application that could be done.

e sense of external pressure from students only adds to this feeling of guilt: According to Daniel*, a second-year Poli-

mands at university, employers increasingly cite time management and resilience as two of the biggest challenges for fresh graduates. It suggests that an ‘always-on’ mindset and long hours don’t necessarily translate into e ectiveness—and for many, that only becomes clear once they leave university.

For many students, the transition into the professional world feels illuminating. Ella*, a BSc Economics graduate working in transport consulting, told e Beaver: “I love my job, but it’s not my life. At LSE, it felt like everything revolved around work. Now, I’ve got evenings and weekends that actually feel like mine. I’m still busy, but it’s di erent—I

‘An “always-on” mindset and long hours don’t necessarily translate into e ectiveness—and for many, that only becomes clear once they leave university.’

perimenting with di erent and varied activities. “It’s not just about developing time management—it’s about learning to embrace uncertainty. Just doing di erent things, even when you’re not fully sure where they’ll lead, makes things happen. e more you do, the more you can do. Some of the most successful and ful lled people just went and did something.”

ere is truth in that. Trying di erent things can help students break out of rigid denitions of success and explore paths they might not have considered. But, for students already feeling stretched thin, even the idea of ‘doing more’ — no matter how well-intended — can feel like another ex-

of studying you’re doing, basically the time expenditure of keeping busy. It pushes me to do more, but I’m not sure that’s entirely a good thing.”

Studies con rm his thoughts. According to the Labour Force Survey, 2.8 million people are out of work due to long-term sickness, primarily caused by burnout and fatigue. While students juggle constant de-

‘ e hardest thing to do at LSE isn’t another reading, another work experience, another application. It’s stopping.’

. Most importantly, I get gen uine time to throw myself into other creative disciplines.” For many, this shi is liberating. e structure of professional life, with its clearer work-life boundaries, allows them to step away from the all-consuming mindset of university.

But that transition isn’t always easy. It raises an important question: How well does LSE prepare students for entering the world of work?

Lewis Humphreys, an LSE careers advisor, emphasises that students should make the most of their time at university by ex-

pectation to meet. When productivity is so deeply tied to self-worth, how do you separate healthy creative exploration from the pressure to always be in the state of ‘achieving’?

Bérénice, one of the Social Anthropology community ambassadors, re ected upon the weekly arts and cra s sessions they host in the department’s common room. “We asked ourselves: what would bring people together, what would foster friendships and solidarity among students? We needed something fun and non-academic, something accessible

to students, allowing them to switch o from readings and assignments, making their time at LSE lighter and more enjoyable.”

“I don’t see expectations of achievement creeping into those spaces,” she adds. “Rather, I see people trying new things and reconnecting with old hobbies. e end result is o en a surprise, driven by the motivation to explore ceramics, jewellery making, or even creating holiday decorations. ere is no pressure to perform or to be perfect. ese creative events touch upon the students’ personal lives, enabling them to bridge their student and everyday lives.”

at desire to reclaim time, connection, and creativity outside of achievement is part of something deeper. As one graduate put it plainly: “ e problem with the world today is that people are running at full speed but going absolutely nowhere. Busyness has become a convenient mask— one that allows individuals to convince themselves they’re doing enough. For many, the relentless hustle is disguised as ambition but, in reality, it’s emptiness.”

LSE’s culture o en reinforces that mindset. Here, long hours and back-to-back commitments don’t just feel normal— they feel necessary. ere’s always something more to do and stepping back can feel like falling behind. But does busyness always mean progress? Or just movement? e hardest thing to do at LSE isn’t another reading, another work experience, another application. It’s stopping. And maybe that’s the lesson students need most.

*Names have been changed to preserve anonymity.

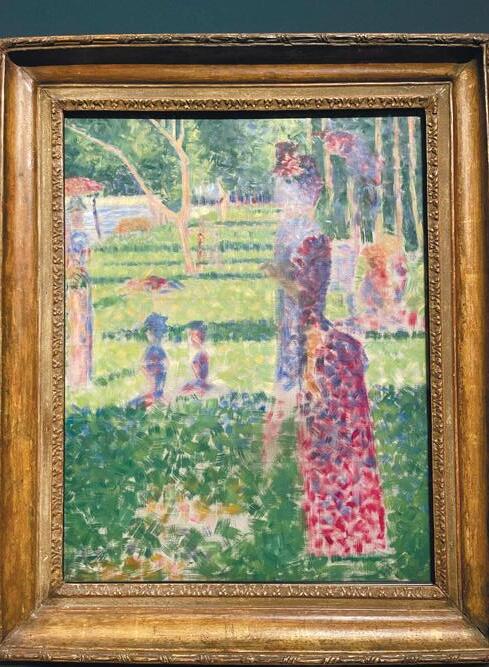

Sylvain Chan Multimedia Editor Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

Art is both fetishised and undervalued. Everyone loves watching movies and engaging with fan art from their favourite franchises. But many take for granted the labour of love that goes into the creation of this media, especially when it appears to be awed. “Why is the animation in Invincible still so choppy?” or “Who let the atrocious backlighting in Wicked slide?” or “CGI in cinema has really fallen o since Pirates of the Caribbean”.

“Artists are getting so lazy; doing art isn’t hard.” Never mind how studios are sacri cing quality for pro t, as layo s, outsourcing, and generative AI-assisted production become the norm in the animation process. Never mind how fast turnover rates desensitise consumers to the arduous years it takes for art to be translated from page to screen. And god forbid, a director’s creative decision runs contrary to your own tastes.

In fact, it’s so simple to make art; you can make a short lm yourself by simply typing some prompts into Sora and stringing clips together. Let’s ignore the holes in continuity, the distorted character proportions, and the absence of a cohesive narrative. is innovative technology will only improve with time, and empowers people that lack artistic talent to contribute to the conversation!

Why try — risking vulnerability, failure and wasting time — when you know you can have a machine churn something out for you in under a minute?

ere is a lot to criticise about generative AI: from legal concerns surrounding programmes scraping copyrighted artwork, to the environmental damage these electricity and water-intensive models exert,

exacerbating the dire climate crisis. But on top of the ethical issues, I think we need to think twice about the cultural ramications of normalising generative AI in the creative process and wider community.

In December 2024, LSE and King’s College London hosted a an AI ‘Art’ Challenge for participants to consider the assistive potential generative AI has in the creative process, if engaged with responsibly and ethically. Conceptually, this is interesting as it encourages a developing conversation around AI literacy.

However, I believe that using generative AI as a ‘collabora tive’ tool — even if one were to just generate reference images or create a base to develop from — is not ethically di erent from appropriating generat ed content as your own without reimagining it. Regardless of how trans formative your work be comes with the human touch, you are still utilising programmes built on sto len data, thereby improving its ability to process patterns and create ‘accurate’ output. Exacerbating the technical prowess of generative AI has devastating consequences far beyond art: from Open AI’s human labour exploitation al legations of exposing their un derpaid content moderators based in Africa to traumatising material, to the ongoing deepfake pornography crisis a ecting female celebrities and young girls alike. Expecting everyone empowered by this technology to approach it ‘responsibly’ ignores the unregulated, unethical mess that is intrinsic to generative AI.

for their livelihood, subscribing to the narrative that artists should be more ‘productive’ speaks more to the necessity of reform in their working conditions, rather than the fault of artists not being e cient enough.

Regarding art as a ‘labour of love’ is o en at odds with the cutthroat nature of capitalism, where so many end up sacricing their passion to tight

this dance of transforming, studying, and remixing starkly di ers to how generative AI understands art: a procedure that scans and replicates patterns in a neural network, devoid of meaning.

Let’s take a look at the recent allegations Rainbow S.p.A. has acquired for using generative AI in the upcoming Winx Club reboot. For a show that “immortalises Y2k fashion”, and integrates characters’ appearances into their personality and overall story, it comes as insulting to long-time fans of the franchise, to see the media they deeply cherish be so compromised on the quality of its character designs and promotional material. You cannot expect fans in good conscience nancially support, or even engage at any level, with work that lacks love.

But it’s important to remember that art is not just a skill, but an expression of humanity. Not everyone creates for money or fame.

Additionally, one must reconsider why artists should even resort to using generative AI in any capacity. Perhaps it does ‘save time’ and increase output, but what does this say about how we, as a society, value art? Must art be reduced to a mere statistic to meet KPI’s? While it is true many artists are dependent on illustrating

e artistic process is one of dedication and persistence. No one picks up a pencil and instantaneously creates a masterpiece: it’s about having the humility to recognise your shortcomings and the motivation to desire improvement. As Austin Kleon strives to convey in his book Steal Like an Artist, inspiration lies at every corner. Whether compiling reference images on Pinterest, studying your favourite artist’s compositions and technique, or staring at a tree outdoors for too long guring out how to render leaves from a distance,

certain elements would look in newer frames at di erent angles. e Nintendo Switch 2 is expected to support upgraded graphics thanks to AI upscaling. ese examples align with Sophia Smith Galer’s emphasis during a recent AI workshop for authors: “the best AI keeps humans in the loop”, unlike speci cally generative AI models which usurp the role of original creation from humanity.

Yet on average, incorporating generative AI into the artistic process does little to counter the rampant appropriation of creative work. It only reinforces the devaluation of the arts as something easily replicable and mass-produced by technology.

I have witnessed the works of inuential artists like Qing Han and Kim Jung Gi be instantly processed into generative AI models a er their unfortunate passing. I have watched art students voice their frustrations and demotivation a er seeing their university platform AI-generated artwork. I have heard of countless stories featuring freelancers losing clients to AI. For many at the bottom, the destructive impacts of generative AI is a lived reality. It is so frustrating to watch authorities with the power to regulate its usage, twiddle their thumbs and rhetorically hypothesise a world where creatives are supposed to adapt to a techno-fetishistic environment they never asked to endure in the rst place.

However, it is also important to acknowledge how AI can prove bene cial to art. A er all, Into e Spiderverse animators documented using machine learning to predict how

What, then, can artists do? ough AI has seemingly been normalised as an integral component to our society, there are still various methods of collective resistance that are worth being employed to challenge this erosion of culture. Many artists use Nightshade, a tool that ‘poisons’ their work to prevent AI models from accurately scraping its data. And rather than give ‘AI slop’ more engagement, people should turn to celebrating independent creators, such as Kiana Kahnsmith and her recent pilot animatic Pretty Pretty Please I Don’t Want to be a Magical Girl, or Studio Heartbreak’s Taglish animated lm e Lovers, or even the friends around you.

e act of creating and appreciating art is an irreplaceably rewarding experience. Even if your rst attempts at worldbuilding are clumsy, even if your rst illustrations were crude Microso Paint doodles, they are in nitely more earnest, more authentic, and more meaningful to your own development than anything generative AI could comprehend.

Chloë Amaratunga-Brooks Sta Writer Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

For those of us who grew up with the internet, it’s hard to imagine a world where online content isn’t forever—a permanent, vast, and unending archive that would exist for posterity. Every cringe tweet, meme, news article, and obscure webpage felt like it would always be one search away. But what if this notion of ‘forever’ had an expiration date? We’ve always been told that what we put online stays online, that an online mistake could haunt you forever, and to be cautious about what we post: this concept of permanence has practically become a digital mantra.

e truth is, the internet – far from being a stable record –might be more fragile than we thought. Counterintuitively, digital history could become shockingly easy to erase, particularly as censorship, cyberattacks, erasure, and algorithm-driven content control reshape the internet.

e Brownstone Institute recently reported that a quiet “scrubbing” of the internet is underway, where content is removed without much notice or fanfare, o en due to changes in policies or corporate priorities. When entire archives are sometimes wiped and content that doesn’t align with platform policies disappears, this digital scrubbing ultimately risks becoming our generation’s Library of Alexandria—a place that once held vast knowledge, lost in a tragic and irreversible way.

Case in point: Archive of Our Own (AO3), the popular fanction platform, su ered a cyberattack in July 2023 that rendered much of the site’s vast amounts of content temporarily inaccessible, and the outage was a rude awakening to how quickly digital content can disappear. In a moment of sheer digital panic, if fanction can disappear; what

next?! If hackers can compromise entire archives instantly, what does that say about the security and longevity of online information?

Archive.org, our trusted ‘internet’s memory’ we rely on to preserve everything from historical documents to memes, was similarly hit by a cyberattack in October 2024, forcing it into read-only mode and e ectively halting new archiving, becoming a static page that jeopardised its ability to capture the internet’s dy namic evolution. Meanwhile, Google’s recent discontinua tion of its cached page feature (a tool that allowed users to view snapshots of web pages as they appeared in the past) leaves users with virtually no free tools to access past web con tent. For all the talk of the in ternet’s permanence, digital content is feeling surprising ly temporary, and the result is an information landscape that’s more closed and con trolled than ever.

Parallel to cyberattacks, we’re also witnessing an era of heightened censor ship and aggressive algorithmic control. e freedom to access diverse perspectives and information, once seen as a fundamental principle of the internet, is becoming increasingly restricted.

started prioritising AI-determined results, trading organic results for algorithmically curated (in a stroke of genius, Londoners are exploiting these aws by love-bombing the Angus steakhouse chain to manipulate AI-powered search engines and mislead tourists from overcrowding restaurants).

Earlier this year, the TikTok ban in the US (over national security concerns) triggered

TikTok ban is not just about one platform; it signals how easily digital ecosystems can be dismantled and is another step toward a controlled internet, where governments and corporations can dictate what stays and what disappears, creating a digital black hole in our collective memory.

forms – and the content they host – are subject to political whims. It shows how easily entire ecosystems of content can be wiped from public access.

Take social media platforms who use algorithms that increasingly in uence the content we see, making certain information less searchable or even burying it completely. Instagram introduced an opt-in requirement for political content, yet this shi wasn’t widely publicised, meaning many users were unaware that, by default, certain types of content would no longer appear in their feeds, thus shaping what users see whether they realise it or not (it’s almost as if Meta was hoping no-one would notice that certain topics would stop appearing in people’s feeds).

Search engines, once vehicles of un ltered knowledge, have

If TikTok’s content is wiped from US servers, what happens to the millions of videos documenting everything from eeting trends to signi cant grassroots movements that have ourished on the platform? What happens to our cultural archive, documenting trends, personal stories, and global events in real time? e

e implications of these trends are profound. With major players in online search and social media shi ing from organic to AI-determined results, from free speech to censorship, our access to information is increasingly curated by falsities. Governments and corporations exercise control over what remains accessible online, undermining the idea of an open, democratic internet. e impact? A fragmented and censored information landscape where record loss is not just possible but likely, and a setting that erodes the internet’s founding principles: freedom of information and democratic access.

e question of what remains accessible online becomes even more signi cant when you consider how this gradual erosion of digital preservation tools could mean our grandkids may have to take our word that “the internet was really something back in the day.” Information loss and restricted access are more than inconveniences; they erode our collective memory and hinder our ability to reference the past accurately. Imagine trying to un-

derstand a past event or social movement without access to social media discussions, news articles, or online publications documenting it; imagine trying to understand the COVID pandemic without the memes that circulated.

e promise of the internet as an open, accessible library is becoming a distant memory, replaced by algorithms and corporate interests. We laugh at the idea of ‘printing the internet’ but as more content vanishes without warning and digital records become unreliable and subject to algorithmic suppression, physical copies of critical information may be the only truly permanent way to save data.

Ultimately, we must ask what it means to lose our digital history. It would be like watching the Library of Alexandria burn all over again, the loss of irreplaceable knowledge, philosophy, and culture except with emojis, memes, and unhinged forum debates—a gradual, unseen erasure of digital records that undermines our ability to understand and learn from the past. Each time a post, website, or archive goes dark, a piece of our collective memory is erased.

For a generation that believes “the internet is forever”, it’s a di cult reality to accept, but what does ‘forever’ mean in the digital age? We may not be facing a literal re like the one that destroyed the Library of Alexandria, but the metaphor is more tting than it seems. Digital information can burn just as easily – quietly and without smoke – if we don’t take steps to protect it.

• “People need to stop wearing their LSE lanyards”

• “People should stop applauding at the end of lectures”

• “Short people deserve less representation in the media”

• “Normalise irting with friends”

• “LSE is not a personality”

• “Paddington Bear is British propaganda”

Suchita epkanjana

Frontside Editor Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

As the spring owers and longer days slowly phase out the winter, a not-so-beautiful reality also comes into view—the dilemma of where to live for the next academic cycle. While some may opt to battle incoming freshers for LSE accommodation, most will end up deciding to privately rent a at.

I myself was one of the latter: a wide-eyed, excited rstyear ready to dive into the idyllic university life where I’d spend the best years of my 20’s in chic central London ats with my closest friends! At least, that’s what binge-watching ten seasons of Friends made me believe living in a at would be like.

So you can imagine my bitter disappointment when I was hurled head- rst into the deep end of the swimming pool called ‘the London Rental Market’, notorious for being the peak of frenzied competition and preposterously-high price mark-ups

According to an article by e Independent, London rent prices have increased 31% since 2021, and there are now an average of 25 households competing over each property on the market. Given this immense pressure to beat rival renters, it is no surprise that 40% of private renters are now paying £1,200 above the advertised rate for their property. Put simply, at hunting is London’s Hunger Games—while it lacks the same amount of death and gore, it is nonetheless a brutal rite of passage into adulthood. e intense, cutthroat nature of at hunting gives any naïve

young teenager no choice but to toughen up and face the adult world, acquiring vital survival skills and experiences in the process.

I entered my at hunting journey well-mannered and optimistic, and came out of it sel sh, confrontational, and signi cantly better-equipped to face the real world. is is the story of how at hunting made me a worse person but more importantly, a better adult.

It was midMarch 2024, I was 19 years old, and the only stressful thing on my mind was a GV100 essay. I was chilling. until three of my friends announced triumphantly that af ter less than one week of searching, they had signed a contract on an af fordable yet beautiful, ful ly-furnished minutes walk from LSE’s campus and available in September. For li gle nger, they were spared from the trenches that was the London Rental Market, just like that! And they just had to rub it in, showing o their new pristine blue walls and queen-sized beds to me for the next few weeks.

girls by spending a good 75% of my waking hours doom-scrolling on Zoopla and Rightmove, logging any prospects on a meticulously-color-coded spreadsheet. If my friends could nd the perfect at almost immediately, surely this would be easy for me too, right?

150+ unsuccessful entries on the spreadsheet and ve dismal at-viewings later, I could not be more wrong.

Suddenly, righteousness, kindness, and sel essness didn’t mean as much to me as an a ordable two-bedroom did.

spair, frustration, and anger began to seep in, and I started having nightmares of myself drowning in hordes of renters making absurdly-high o ers on squalid ats.

I had never felt so jealous in my life.

And thus became my rst lesson in adulthood: the only thing you can do with such insurmountable levels of jealousy is to turn it into ery, tunnel-visioned determination.

I o cially embarked on my at search with three other

I got exclusive rst-viewings on ats by pitting agents from the same company against each other. I made promises to put down an o er in exchange for lowered rent, only to pull out of the deal last-minute. I woke up in the middle of the night, strategising on ats under offer from someone else. I once led an agent on for so long with my false promises she scolded me for wasting her time, and I scolded her right back. Worst of all, I turned my back on the girls I had promised to move in with, after secretly securing a two-person at with another friend and not telling them until we legally sealed the nd egregious today.

Alas, in April of 2024, Inally signed a contract on a at that I loved—reasonably-priced, spacious, close to campus, and pretty much

perfect! I had nally succeeded.

I had also become insensitive, impatient, and irritatingly-persistent by the end, but I arguably would have failed more intensely and miserably if I hadn’t changed. Furthermore, it was these newly-obtained skills and life lessons that, while sometimes morally-questionable, will likely be indispensable to living in the adult world later on.

Flat hunting taught me how to negotiate, sugar-coat, and even straight-up lie when I needed it most. It taught me to make demands, push harder, and not back down. Most of all, it taught me the experience of wanting something so damn bad and refusing to stop until I get it.

Most importantly, at-hunting taught me that, just like in real adulthood, not everything will feel ‘fair’. e amount of hard work you put in does not guarantee proportionate success (weeks of toil may not earn you the same glorious Holborn bachelor pad someone else landed a er two days of minimal e ort). But with the right amount of relentlessly abrasive pestering, amorality, sucking-up, and most importantly, desperate determination, you might end up pretty satis ed (in a warm and cozy at on the Strand) one day.

Most of all, I was outraged and disillusioned at how ‘unfair’ this whole thing was: Why is it that a er weeks of cold-calling and begging letting agents, I have nothing, while my friends got the at of their dreams when they barely even tried?

My fantasy of the perfect Friends-esque life was ying straight out the window, and with them went my morals.

While I may have dramaticised my at hunting experience to make a point, I must emphasise just how privileged I am to be able to a ord rent at all. And in Central London, no less. Every Friday, a line of homeless people gather just down the street from my at for food donations. ey are a constant reminder of what happens when the rental market does not adequately serve its people. Many people are faced with homelessness a er being forced to move out of their homes and unable to nd an a ordable and adequate at in time. In fact, it is this “lack of safe and a ordable housing” that underpins the massive homelessness problem in the UK, according to Crisis UK. For more information, check the Renters’ Reform Coalition, a campaign to increase and strengthen renters’ rights in England, at: https://rentersreformcoalition.co.uk/

Lessons we have learnt while on the Ed Board:

Mahliqa (Features Editor)

ere are so many interesting people and communities doing amazing things on LSE’s campus and beyond, who deserve to tell their stories. Seeking out these underrepresented groups is the rst step; the responsibility of portraying people in a way that does them justice is the main part.

Journalism is never neutral, regardless of how objective Features aim to be. What matters is allowing people from these communities themselves to authentically tell their own stories.

When external narratives are imposed, communities can come to be understood in a way that is completely unre ective of the warmth and richness they know themselves to embody. I’m not here to impose my own perspective. I’m here to listen, learn, and understand from people whose experiences are di erent from my own. at’s the value of having such a diverse campus. How do people conceptualise things di erently, what are their alternative worldviews, and how can we engage with them receptively?

Ultimately, I am not the authoritative voice on other people’s experiences challenging conventional knowledge created by those who have held power over those they have represented requires us to approach topics with sensitivity, empathy, and open-minded curiosity.

Lucas (Opinion Editor)

When I rst stepped into the Media Centre as an aspiring contributor, I was desperate to reinvent myself out with the shy, anxious, risk-averse Lucas, and in with the new con dent, sociable, gumptious Lucas, who could ‘get OUT of his comfort zone’! Strangely enough, out of all the (outlandish) things I could have tried at LSE, I swore to myself that I’d write for e Beaver, even if it was just one article. Every bre in my body resisted the thought: How could I ever willingly produce a piece of writing outside of school? God forbid, writing could actually be a FUN activity!

I’m now eternally grateful for this one time I let my intrusive thoughts win. My time at e Beaver serendipitously awoke a love for writing I never knew I had. One article became two, and, before I knew it, I had created precious memories and friendships that have de ned my second year.

In some ways, I’m still the same quiet, sensitive person from freshers’ week. Yet, in others, I’ve become so much more con dent and sociable not because I successfully moulded myself into someone I was not, but because I was able to share my newfound passion with like-minded people. We o en have the misplaced ideal that we should narrow our vision towards a passion that’s magically appealed to us at a speci c moment in time. To me, however, passion should be equally developed through time and investment, even if it’s something you may not initially enjoy. If you do just a little more digging, you never know what life-changing gem you could nd!

Aaina (Opinion Editor)

ere is a lot to be loved about the Beaver the joy of contributing to creating something meaningful, the countless hours of idle chatter in the Media Centre, the people who always have something interesting to say, or for me, most of all, the ability to be bold in ways one can seldom be once they step into the scathing politically governed world of commercial journalism.

Re ecting upon this past year, it is di cult to narrow down on a single favourite memory since there have been such an abundance of them. However, something I look back on quite fondly is the one time I spent most of the weekly Opinion meeting solving e Beaver crossword (courtesy of our Multimedia Editor) with other editors. I feel this was an important step in my journey, as it helped me break the ice and get to know the unique, complex and wonderful people they were beyond the work they did and ideals they held.

In my journey at e Beaver, I also found the invigorating feeling of the knowledge that my work was not only read but well received and applauded when someone who I had never spoken to before reached out to me on LinkedIn complimenting one of my articles an ariticle which I had not only invested a lot of labour in, but also, something I am truly passionate about as a cause. ese small reinforcements of community and appreciation, at the end of the day, are really what keep me in the writing business.

My favourite memory from e Beaver has to be the evening of 11 December, with the other members of the editorial board. Our plan had been to head to the pub following the launch of our issue, but when we found it packed to the brim, we ended up at HIBA by Holborn for kebabs, grabbed a few drinks from Sainsbury’s, and made our way back to the beloved media centre. With the lights o and the lamps casting a so glow, the atmosphere was just perfect; we sat in a circle and took turns sharing our rst impressions of each other, one of the best moments being when we tried to mimic Janset’s signature meeting pose—elbows on knees, hands clasped, eye contact unwavering, all business. Another hilarious moment was trying to guess how many siblings everyone had, with Paavas being assigned ‘middle child’, which apparently isn’t exactly a compliment… But what really stood out to me was the comfort we had with each other—the way we could tease one another and laugh it o . It was in those moments that I felt the shi , like we had moved beyond just colleagues to something more like a family (just as Janset called us the other day)… Not to mention that the rst impressions I received, such as ‘I thought you were French’, ‘you look like you eat Sunday Brunch’, and that I seem ‘put together’, were a massive ego boost x

Liza (Features Editor)

A er two sweet years on e Beaver’s Ed Board, I feel rather nostalgic as I am writing my farewell. I will really miss this community, bursting with creative thinking and passion to do something meaningful; I will also miss watching the writers blossom and develop their own distinct styles. Yet, con te partirò!

e rst time we sat down to format an issue with my co-editor last year, we spent at least ve hours grappling with InDesign (for context, it’s meant to take around two-three for Features). Which is where comes my rst advice: Keep a note entry on your phone with ALL the useful InDesign tricks you learn (e.g. what keys to press to resize an image without cropping it, or which tools to use to text-wrap an irregular illustration). is saved us a million times! But, if in doubt, track down the Flipside Editor—they would know what to do!

Another tip for incoming Features Editors is to organise a few dra s over the summer so that you don’t have to stress about scrambling for articles at the beginning of term. Given the long format of Features pieces, there is always a shortage in October, as writers are warming up their feathers, so having a few articles ready to go is a must.

Writing and editing at e Beaver has stretched my potential much further than I thought it could go. I never thought of myself as a writer, but, having written for all seven sections at e Beaver (by the time Issue 8 comes around), I inadvertently became a writing machine. It’s a bittersweet ending to be graduating and leaving e Beaver, but it’s given me an invaluable experience and long-lasting memories!

To future editors: To be a journalist is to be a listener. Above writing, editing, emailing, and formatting, you have to treat other people with respect and dignity when you’re interviewing them. I always try to approach interviews with sensitivity and clear boundaries, especially if the topic is particularly contentious.

Most of all, don’t hesitate to take initiative. If you nd a good news story, investigate it. Ask anybody and everybody you know about it, reach out to people by email, nd people on campus who might know someone. News is a very lively section, meaning you can’t expect news scoops to fall into your lap. Events are always unfolding on campus and the onus falls on you to nd out all the details.

Finally, take yourself seriously. Student journalism is a cornerstone of democracy in universities. As a student journalist, you wield the power to spotlight student and sta stories that wouldn’t be broadcasted otherwise. Student newspapers are a vital part of every university campus because they bring a critical perspective to the institution, being a formalised place to challenge and question university leadership. If you nd yourself lacking the drive to write, think about the bigger picture.

At the beginning of my rst year at LSE, there were few things I wanted more than to work for e Beaver. I loved coming to the Media Centre on Wednesdays for Features and Opinion meetings and watched with intrigue as Alan and Vanessa discussed solutions to libel issues, Liza and Amadea formatted the next Features spread, and Kieran and Honour helped a writer re ne their pitch. is was a community I so desired to be a part of.

A year later, I have had the honour to oversee over 70 articles published across the sections I love most and work with six talented section editors, all of whom I continue to admire and learn from every day. Over the past year, we have covered protests and controversies, from the Encampment to the ‘Understanding Hamas’ book launch. We have spotlighted the lives of students and sta , from Finance Bros to the LSE_7 to the legendary Sam McAlister. We have opined about everything under the sun, from pirates to AI to Narendra Modi.

To say I am proud of our Frontside team is an understatement. Most of all, I am grateful to have been one part of this newspaper’s history alongside such a phenomenal group of individuals.

“please... no more non-law students in the law common room... there aren’t any places for us anymore.”

“there’s a wall with what looks like peeling paint and damp from water damage”, “its crusty and old”, “it’s impossible to get fresh air”.

“free pizza! go management!”

“the chairs in the sociology common room are so uncomfortable.”

“it looks like a nursery.”

“need to dinsigtuish between common work areas and kitchen facilities. this room is a disaster. mould in the fridge, no cleaning equipment...”

“the reason why i keep coming back to the common room is because it is a space my friends and i can meet that is usually free.”

(non-anthropology student): “suprisingly nice. i’d infltrate it more if it wasn’t tucked away in the OLD building.”

“but it’s an upgrade from the old STC common room where we didn’t have any microwaves or kettles.”

“law common room is the best, philosophy is the worst.”

(non-fnance student): the fnance common room “does not have good vibes”, “the atmosphere is so suffocating”, “maybe it’s the gender imbalance”.

“very ugly.”

“seeing as lse is sandwiched between oxford and cambridge for geography, we deserve better!”

“hidden away, but at least it has a microwave.”

“i wonder if there is a correlation between common room quality and the amount of private sector employment that could result from that department...”

interested in reading more to uncover the truth behind this comment? read the full article here!

party lewis salty shaw houghton serle march how connected to lse are you? group words that share a common thread! just like the nyt’s connections, create four groups of four from the words below.

hicks bean sheffeld meade

in

Leafy green found in smoothies

Worrier’s woe, they say

Spiritual guide

Nights before

What wounds and colours may do

Longest cricket format

hi there, crossword beaver here! i hope you’ve enjoyed solving the crosswords this year. i started this in hope sthat the us would subsidise my nyt games subscription - while that has not happened yet, i realised that making crosswords is way more fun than solving them. it warms my heart to imagine friends putting their heads together and having fun, and i look forward to making more for you all to enjoy!

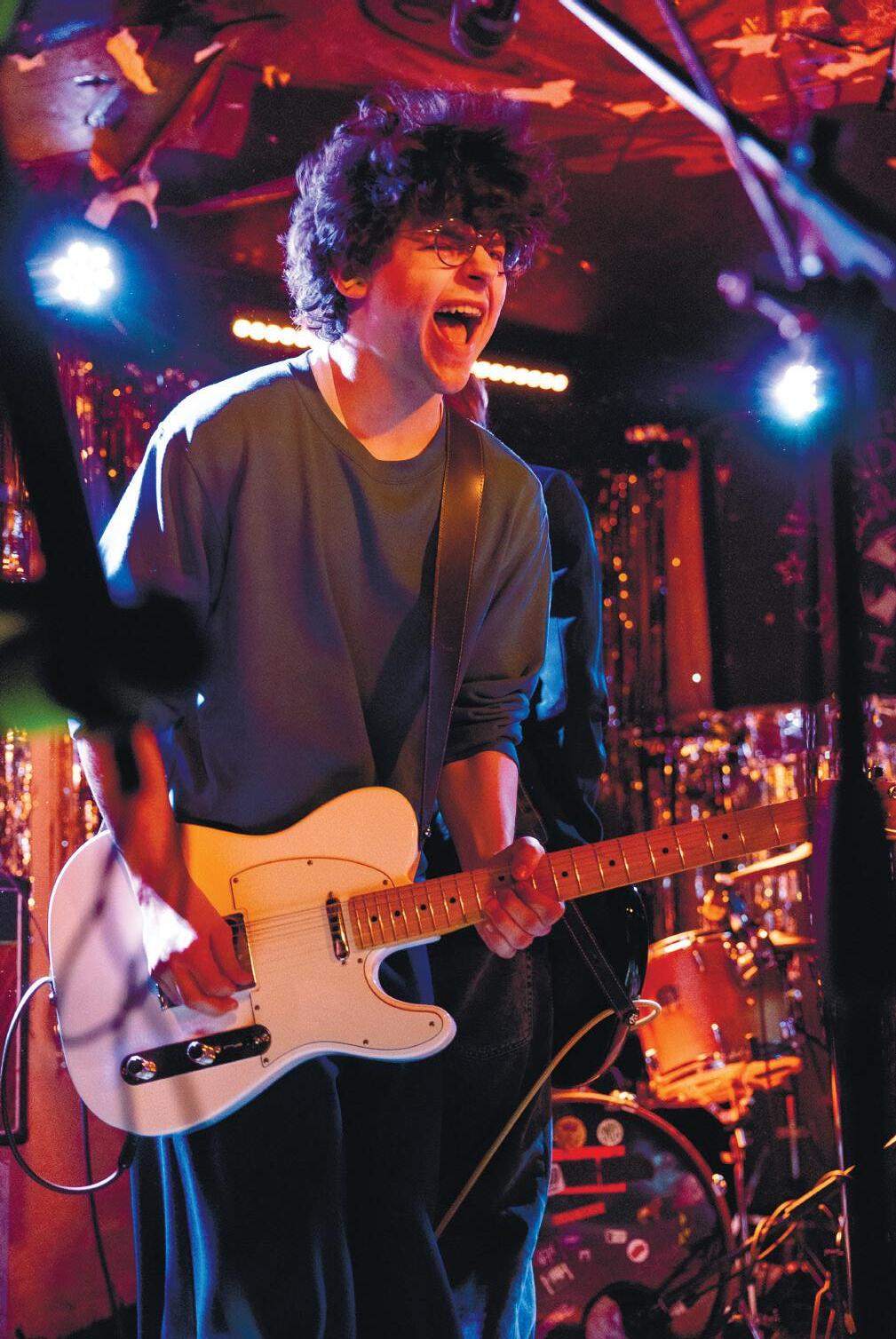

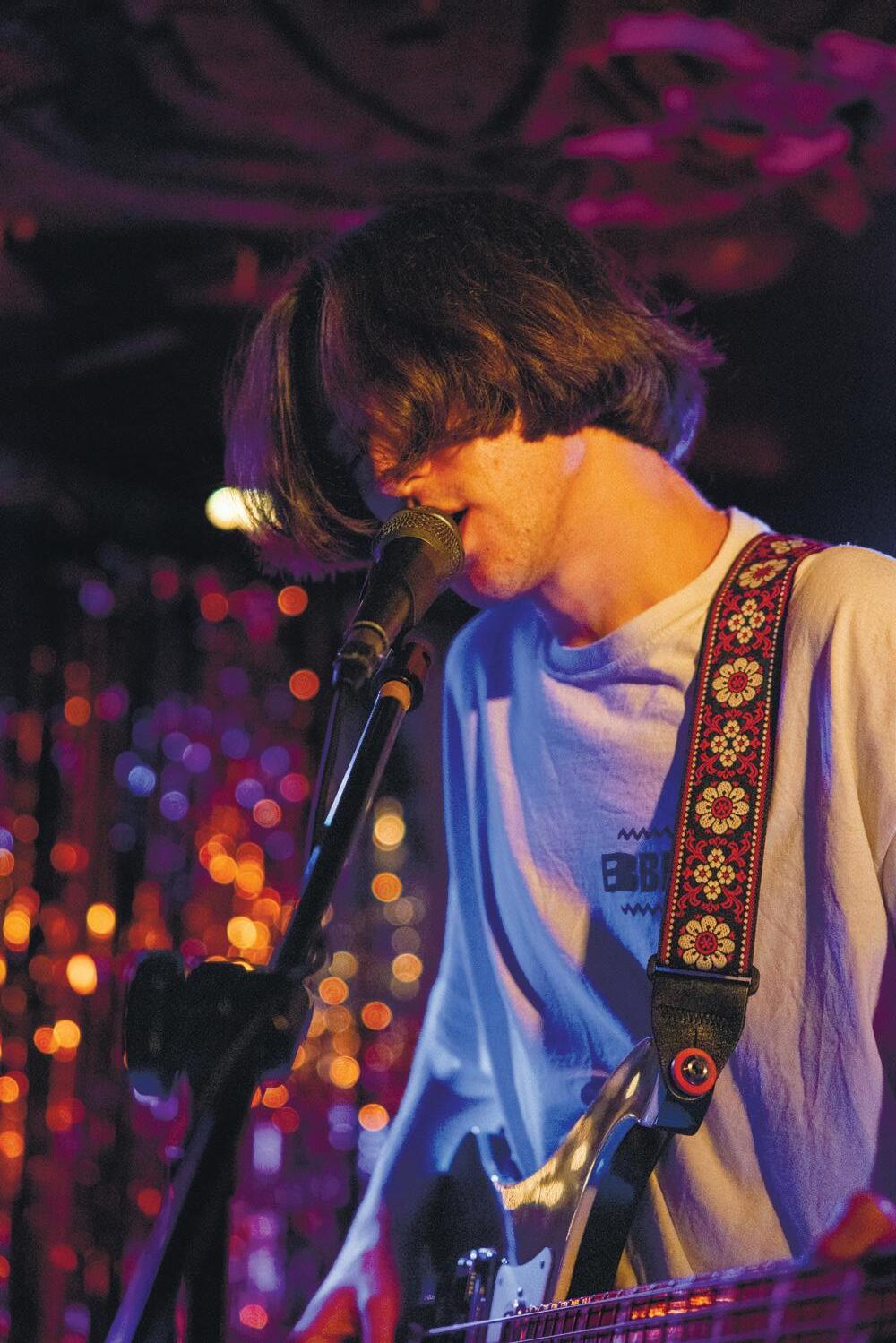

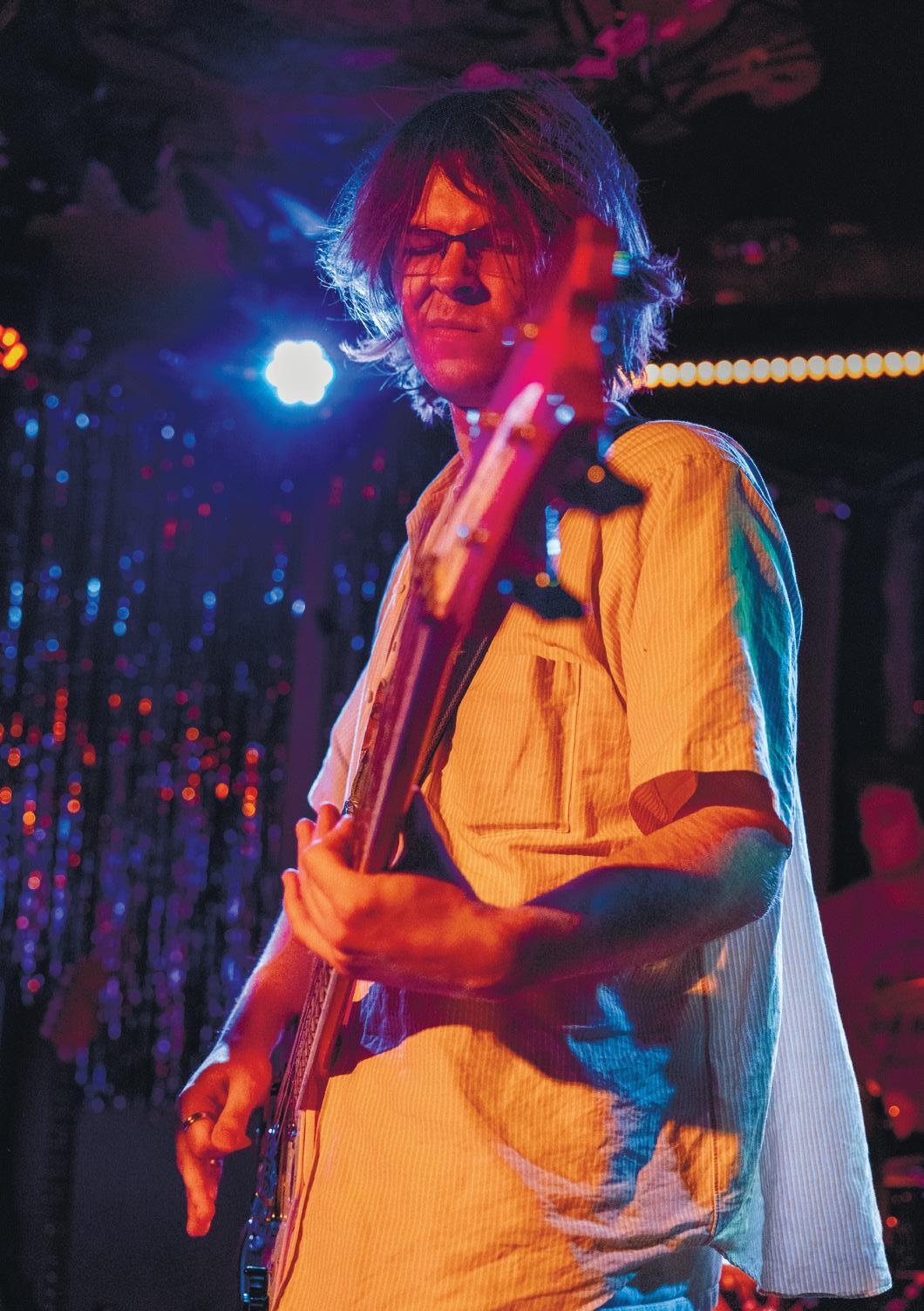

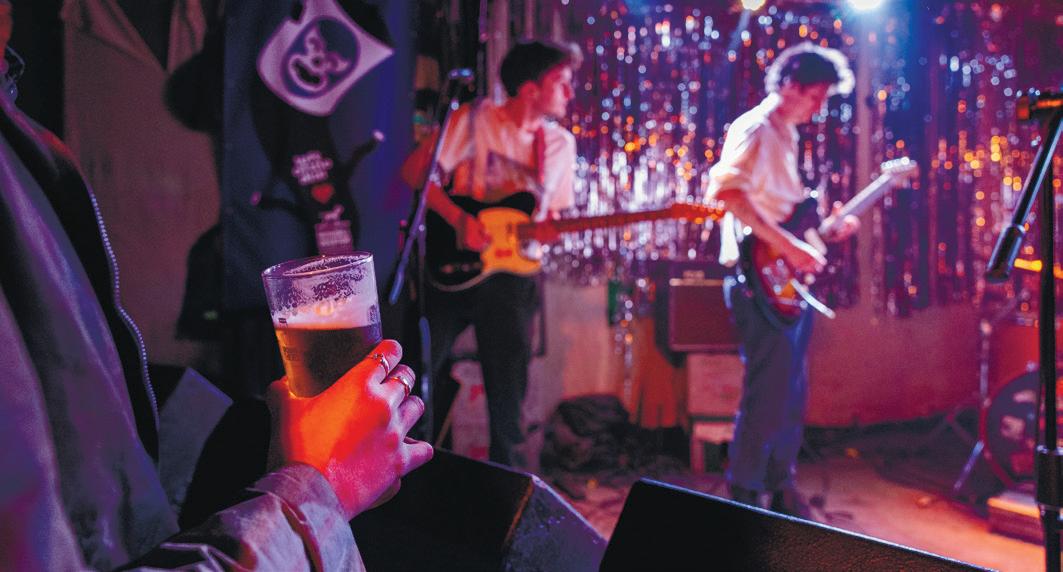

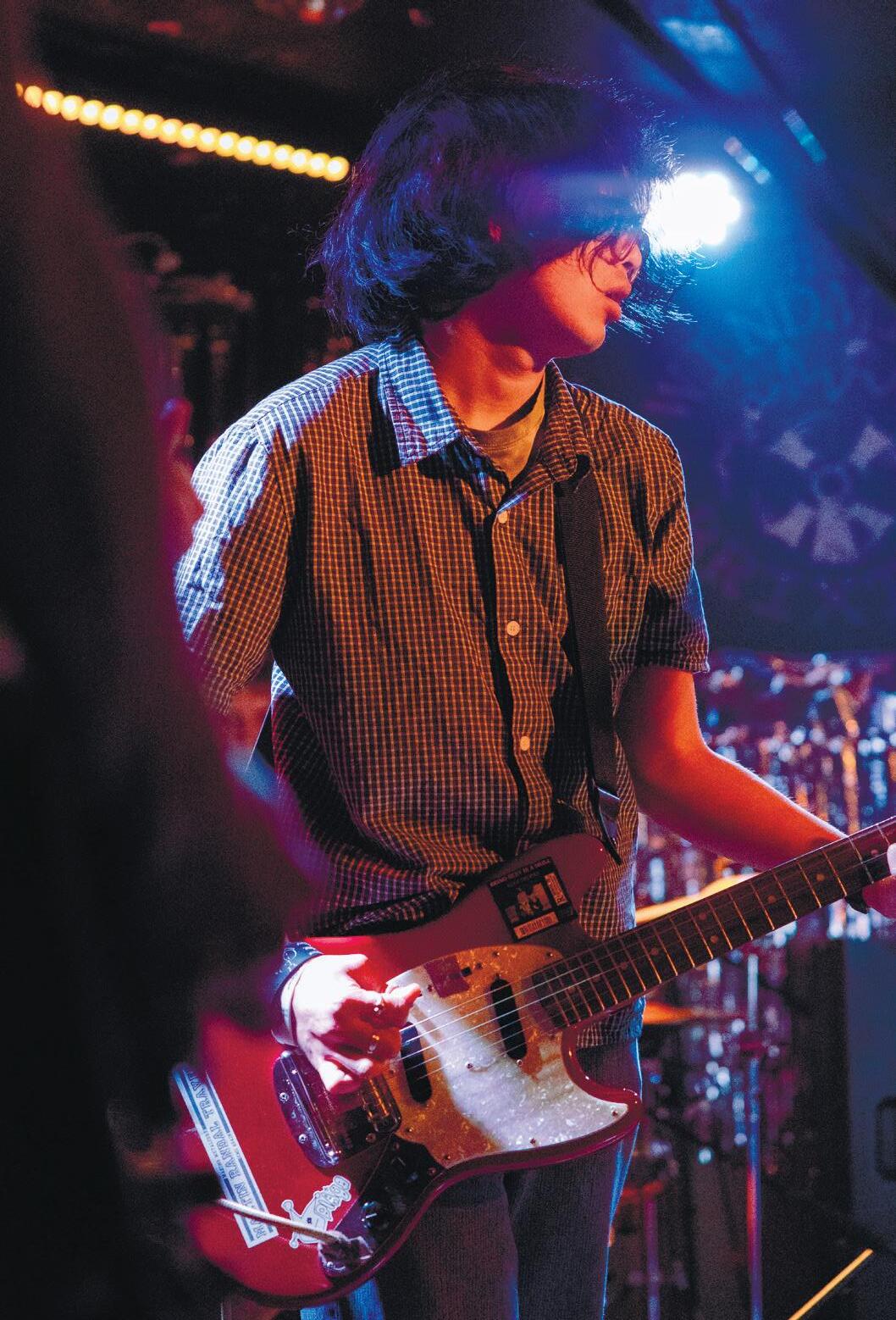

Ryan Lee Head of Photography

Every band has a starting point before their breakthrough. e Beatles rst performed at the Jacaranda, a pub in Liverpool. Green Day frequented 924 Gilman St., a 500-person venue in Berkeley, California. Weezer rst formed and played in a garage.

But what does that starting point look like? Here’s a glimpse into the underground scene at the Windmill Brixton: a 150-person venue nestled in a residential neighbourhood.

Bands featured, with their Instagram handles: Newbuild (@newbuild.band), Civil Partnership (@civilpartnership), and Dog Saints (@dogsaintsdogsaints).