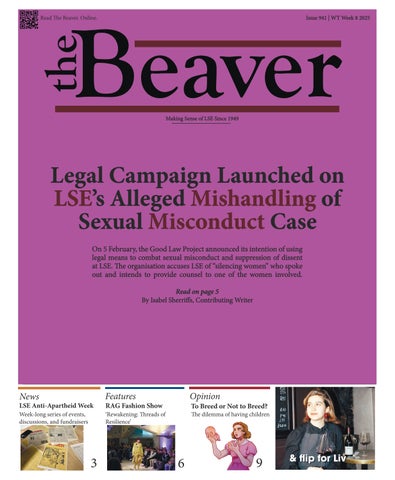

On 5 February, the Good Law Project announced its intention of using legal means to combat sexual misconduct and suppression of dissent at LSE. e organisation accuses LSE of “silencing women” who spoke out and intends to provide counsel to one of the women involved.

Read on page 5

By Isabel Sherri s, Contributing Writer

‘Rewakening: reads of Resilience’ Week-long series of events, discussions, and fundraisers

e dilemma of having children

Executive Editor

Janset An executive.beaver@lsesu.org

Managing Editor

Oona de Carvalho managing.beaver@lsesu.org

Flipside Editor

Emma Do editor. ipside@lsesu.org

Frontside Editor

Suchita epkanjana editor.beaver@lsesu.org

Multimedia Editor

Sylvain Chan multimedia.beaver@lsesu.org

News Editors

Melissa Limani

Saira Afzal

Features Editors

Liza Chernobay

Mahliqa Ali

Opinion Editors

Lucas Ngai

Aaina Saini

Review Editors

Arushi Aditi

William Goltz

Part B Editor

Jessica-May Cox

Social Editors

Sophia-Ines Klein

Jennifer Lau

Sport Editors

Skye Slatcher

Jo Weiss

Illustration Heads

Francesca Corno

Paavas Bansal

Photography Heads

Celine Estebe

Ryan Lee

Podcast Editor

Laila Gauhar

Website Editor

Rebecca Stanton

Social Secretary

Sahana Rudra

Sylvain Chan Multimedia Editor

My energy was wholly drained throughout December and January as I ploughed through back-to-back summatives and exams, both plural. It was undeniably a contender for the worst period of my life, compounded by anxieties regarding internships, extracurricular responsibilities, and homesickness. Staying at the Marshall building from day to evening hunched over my laptop, I watched the sun disappear behind the horizon at 3pm, casting the skies in an oppressively mundane gray as though it was deliberately trying to get me depressed. Dragging myself home with puddles made from yesterday’s rain and today’s tears beneath my feet, I really wondered if life could get better.

Despite it all, it has. Coinciding with the submission of my last essay, in the past month, my route to school has been decorated by the honeyed light of the morning, pigeons resting beneath the trees’ shadows with heads tucked under their wing. Opening my emails and seeing satisfactory feedback on my assignments, I listen in on the laughter from the groups of friends sat on mahogany benches outside cafés along Lambs Conduit Street, the sounds accompanied by the rich aroma of roasted co ee beans from inside.

It’s easy to forget just how beautiful London is. As an international student, I think I’m allowed to romanticise this city for just a bit longer before the corporate world completely destroys my sense

of belonging. For example, sunbathing in Lincoln’s Inn Fields last ursday was an experience I’d like to relive. Sure, the dirt was still a bit wet, and the seat of my jeans have seen better days, but the sheer vibrancy of the atmosphere was one to remember. Basking under the once-rare sunlight peeking through the trees, I watched other students kick their feet in the grass, gossiping as dogs ran wild across the open eld. With a Gregg’s Steak Bake in my friend’s hand, and a matcha latte (inside a reusable cup) in my own, we had an incredibly meaningful heart-to-heart: discussing whether we agreed with what the speakers at an event we both attended said, catching each other up on our personal lives, joking back and forth.

Of course, these picturesque scenes are by no means an attempt to persuade you into falling in love with springtime London. I’m well aware many LSE students are in the midst of their own summative seasons, with the recent release of exam timetables proving harrowing for others. Maybe you’re simply not a fan of the sun glaring down at you the moment you step outdoors. Nonetheless, good weather has the (scienti cally proven) ability to upli your mood. If you’re currently going through a slump, just remember to be gentle with yourself. Go for a nice walk, visit that new café around the block, or check out that new museum exhibit you’ve been meaning to go to. Let’s welcome spring with open arms.

e Beaver has been shortlisted for 10 SPA Journalism National Awards, including but not limited to: Best Publication, Best Newspaper Design, and Best Overall Digital Media. We are once again, extremely excited about this news, and are grateful for the SPA for recognising our hard work. e Beaver will be very excitedly heading to Exeter in April to see what we will achieve!

Any opinions expressed herein are those of their respective authors and not necessarily those of the LSE Students’ Union or Beaver Editorial Sta e Beaver is issued under a Creative Commons license. Attribution necessary. Printed at Ili e Print, Cambridge.

2.02

Rebecca Stanton

Website Editor

Photographed

by

Rebecca Stanton

Monday, February 10 to Friday, February 14 was Anti-Apartheid week at LSE. LSESU hosted a week-long series of events, discussions, and fundraisers to bring the LSE community together to ‘re ect, learn, and discuss’ systems of oppression such as apartheid. e importance of this week is felt by many in the community, with ongoing student action demanding that LSE divest from companies tied to unethical practices.

On Monday, LSESU societies including Grimshaw Society, Palestine Society, and Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Society hosted an inter-society bake sale outside the Saw Swee Hock building that raised over £1,000 in donations for Muslim Aid for Sudan and Medical Aid for Palestinians.

Later that day was the Right to Protest Workshop, led by a representative from the National Union of Students, about protesting safely as a student. With the signi cant police presence

at on-campus protests last year and the suspension of the LSE 7, it was a relevant and informative session that highlighted the challenges faced by student activists.

Completing this rst day was a screening of Tantura, a documentary lm about the 1948 forced displacement and massacre of Palestinians living in Tantura by the Israeli military. Incorporating testimonies, documents and archival footage, the conversation a er the screening was one focused on the importance of historical memory and forefronting silenced narratives.

On the second day of events, two KCL alumni, Robert Wintemute, a professor of Human Rights Law, and Sari Arraf, a PhD student specialising in histories of apartheid, led a discussion titled ‘Power of Divestment: Breaking Ties with Oppression’.

Wintemute’s discussion centred around a comparison of apartheid in South Africa and Palestinian oppression, emphasising the use of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement as an e ective tool of resistance against apartheid in situations

where Western governments have not acted to put economic or political pressure on the in icting power.

Arraf led on from this, focusing on the history of activism against South African apartheid at LSE, a running theme of the week’s discussions. LSE students were among the rst in the UK to protest by occupying the Old Building in 1987, demanding that LSE divest from companies in apartheid South Africa. He highlighted the enduring importance of student activism in striving for a system where students are involved in decision making processes that can disentangle universities from violent structures.

On Wednesday, LSE associates Mahvish Ahmad, Muna Dajani, and Akile Ahmet hosted a session on ‘Education Under Occupation’ about the e ects that occupation and scholasticide have had on education in Palestine, as well as the role played by UK universities in apartheid systems. e speakers emphasised the reasons why students at LSE should remain involved and vigilant in holding institutions to account.

‘Living Apartheid Live’ took place that evening, hosted by Andrey X, a journalist and activist in the West Bank, and Tony Dykes, a representative of anti-apartheid legacy, and a representative from the Birzeit University in Palestine. Incorporating a discussion of historical activism with rsthand experience of life under occupation in Palestine, the discussions o ered a deeply personal lens on the e ects of apartheid on everyday life.

ursday’s events focused on LSE’s history of anti-apartheid activism amongst di erent generations of students. Looking at LSE Divest campaign archives from the 1970s to the 2024 Encampment was a powerful testament to the university’s long standing tradition of student activism.

One of the event’s speakers was a student from 1984-88 who spoke about his time as a leader of the LSE Divest Now campaign against South African apartheid. He recounted the importance of making di cult decisions and having clear strategies and objectives in the eventual success of the movement.

e week’s events culminated on Friday in a rally for divestment outside the Centre Building plaza demanding that LSE respect the outcome of the 2024 student referendum on divestment.

Asking the week’s organiser Wajiha, LSESU’s Education O cer, about its importance, she re ected:

“Anti-Apartheid Week 2025 was always something I wanted to plan in my capacity as Education O cer at the LSESU. With the mounting evidence of apartheid and now genocide in Gaza, educating and informing students about apartheid, systems of oppression, and the History of LSE activism, especially following the student activism from the encampment for Palestine last year, was very important.”

“I learnt a lot throughout the week, like the real life impacts

of scholasticide in Gaza and how the erasure of education and standing against this is actually a shared responsibility of higher education systems and students everywhere, including at LSE. ere were interesting discussions on decolonial and post colonial theory and even the now seemingly mainstream idea to ‘decolonise the curriculum’ but with no stance on colonialism in Palestine.”

“ e discussion on the LSE Liberated Zone being a space of belonging was also fascinating, especially for students who had otherwise felt excluded on campus or felt they were in opposition to the school.”

“ e other highlight of the week for me was hearing from student activists from the 1980s and 2010s, and looking through archives of those who opposed apartheid in South Africa and called for divestment. e discussion on community organising and resilience in student movements was inspiring and insightful, rea rming that discussions about Palestine and systems of oppression must continue, and that change can happen when students and people unite against apartheid.”

Amy O’Donoghue Staff Writer

New research by agency Jisc has found that UK universities educate more national leaders than any other country, prompting discussion on the international character of the UK’s higher education institutions. Whilst this proli c achievement can be seen as a source of national pride, there are also concerns about universities’ reliance on international students for funding contributing to nancial instability.

Of all UK universities, LSE educated the second most heads

of states/governments since 1990 with 24, following University of Oxford that came in rst place with 36. With the highest proportion of international students in the UK (65% of students were international in the 2022/23 cohort), LSE clearly has a signi cant global presence. Alumni include Ursula von de Leyen (President of the European Commission), Juan Manuel Santos (former President of Colombia) and Alexander Stubb (current President of Finland).

Vivienne Stern, Chief Executive of organisation Universities UK, described the number of world leaders being produced as a testament to what a “national asset” UK univer-

sities are, bringing numerous “so -power bene ts” to the UK on the global stage.

However, some have taken a more negative view on the increasingly international nature of the UK’s university system. Financial issues have been rife in recent years. With a £3.4 billion drop forecast and 72% of higher education providers expected to be in de cit in 2025-26, there has been much discussion of what universities could do to reduce their nancial instability.

Over-reliance on international fees is o en highlighted during these debates. A 2024 government inquiry into reliance on international students for

funding was concerned about whether this funding model was sustainable. Dependence on these students means universities are vulnerable to uctuations outside of their control; for example, a 16% fall in the number of study visas issued from 2023-24 had a notable e ect on funding.

Nick Hillman, Director of Higher Education Policy Institute, stated that “we will struggle to claim the UK still has a world-class higher education system if over 100 institutions come to have less than 30 days liquidity.” Attempts have been made to rectify this situation, such as the recent government decision to introduce a 3% rise in tuition fees for home students.

LSESU’s International Student O cer said:

“International students bring immense cultural and intellectual value to UK universities, but the extortionate fees they are charged are increasingly unjusti able when you consider the lack of job prospects and post-study support from the UK government compared to countries such as Canada. If even top graduates from institutions like LSE or UCL are struggling to secure employment, it raises the question of why students should pay such high fees only to face limited opportunities and be forced to leave.”

‘A Pulse of Creativity’: Pulse Travels to Paris and Joins Soundsystem Sciences

Angelika Santaniello Staff Writer

Photographed by Pulse

Radio

From Friday 21 February to Monday 24, Pulse (LSE’s creative and music network) travelled to France, partly in collaboration with their Sciences Po (Reims campus) counterpart, Soundsystem. e agreement between the societies entails Pulse attending one of their events and the Soundsystem network would co-host an event in London with Pulse on April 4.

e trip was formed by 20

Pulse members, including members from the main committee, sub-committee, and members who are tied closely to Pulse’s network. e partnership event, which took place on Friday 21 February, involved a team of 20 members from Soundsystem.

e Beaver spoke to Stella, Pulse President, about the logistics and her experience. Stella characterised the collaboration as one of “[learning] from each other”. is involved creating projects with a team composed of both Pulse and Soundsystem members.

Beginning as “a collaboration

and not precisely a trip”, the plan developed into “forming something concrete with us going there”. Driving the project were connections formed by members of the Pulse committee and Soundsystem members.

e agship event was a house party in Reims at one of the student ‘party ats’ – apartment buildings that usually accommodate students and are renowned for a tradition in which each inhabitant hosts a house party. e event involved both Soundsystem and Pulse DJs, as well as being an opportunity for members of each network to socialise.

Stella drew parallels between Pulse’s and Soundsystem’s events. Being based in London, Pulse organises large-scale events, being able to “create that sense of community and family”. Stella explained that Soundsystem “taught [Pulse] how to organise great house parties” and “the energy and the vibe you want to create”.

Regarding Pulse’s excursion to Paris, Stella observed the “community sense” fostered by the group’s meeting at sun-

set on the steps of Montmartre, rendering another trip highlight.

Summarising the trip, Stella described the atmosphere as “quaint” attributed to the “very intimate and almost nostalgic feel, not about ashy events, but meaningful experiences.”

A “pulse of creativity […] fuelled” the trip. “It wasn’t just about the music and the trip but about the way the whole experience brought us together,” she remarked.

Read the full article online.

Melissa and Saira’s picks:

• LSE Dance Showcase ‘Escape’, 17 March, Peacock eatre

• LSESU Summer Ball 2025, 18 June, Natural History Museum. Tickets available on lsesu.com

• LSESU Teaching Awards, nominations open until 23 March

• LSESU Drama Society’s ‘Brief Encounter’, 10 March-14 March

Isabel Sherriffs

Contributing Writer Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

*Trigger warning: this article deals with the topic of sexual misconduct.

On 5 February 2025, the not-for-pro t organisation Good Law Project (GLP) called for funds for a new campaign to use legal means to combat sexual misconduct and suppression of dissent at LSE, according to a post on its website. e organisation criticised LSE’s alleged mishandling of a series of sexual misconduct complaints against an LSE professor.

GLP announced its intentions to provide one of the women involved in the case with coun sel, as well as opening its own investigation. e organisation also accused LSE of “silencing women” who spoke on the sit uation, and invited anyone af fected by the situation to con tact the GLP.

e allegations described by the GLP were rst published by e Beaver in March 2024. In 2021, ve women brought forward formal complaints against an LSE professor, prompting an internal investi gation, which the GLP claims was “botched”. tion resulted in the dismissal of the allegations, whilst the complainants allege the inves tigation was a heavily process.

GLP is now asking the public for donations to support one of the complainants in draw ing up an internal complaint about the university’s alleged mishandling of the investiga tion to the LSE’s vice president. If this new complaint was to be dismissed, the organisation declared it would bring the case before the O Independent Adjudicator for Higher Education.

Since the sexual misconduct

allegations were published in March 2024, many members of the LSE community have voiced their dissatisfaction on campus and on social media. GLP claims some of those who spoke out publicly, particularly on social media, have been met with disciplinary procedures. For example, one student was required to attend a disciplinary meeting because of a social media comment referencing a speci c professor and criticising the LSE’s mishandling of sexual misconduct complaints. With its campaign, GLP hopes to defend students from action taken by LSE.

In addition to support with internal procedures, GLP plans to launch its own investigation,

“While we do not normally comment on the details of individual disciplinary investigations, we want to assure both students and sta that the allegations in this particular case were investigated very extensively and in light of specialist advice. We are con dent that the investigation was robust and that the outcome, in which the allegations were not upheld, was the correct one in light of the evidence presented.”

“We can also assure the community that no sta or students have been disciplined for speaking out about sexual harassment.”

“LSE is committed to a work-

where people can achieve their full potential free of all types of harassment and violence. We take reports of sexual harassment extremely seriously and encourage any member of the LSE community who has experienced or witnessed this to get in touch via one of our many channels, which allow students and sta to make anonymous reports and access specialist support.”

e spokesperson said LSE has developed a number of measures to ensure that any allegation of misconduct receives a robust response.

“ ese measures include the new Report + Support system, which enables us to address issues more quickly and consistently across the School and vastly improves our approach to case management and communication with all involved.”

“We have commissioned Rape Crisis South London and Survivors UK to run an Independent Sexual Violence Advisory service for the School. is provides practical and emotional support for any student (or sta member) who needs it, and supports them through a reporting process and/or

the criminal justice process if they wish. is service is available online without a waiting list.”

e spokesperson highlighted LSE’s all-sta online training course on addressing sexual misconduct and harassment a ecting students, which is “being rolled out across the School.”

LSE policies “include the prohibition of personal relationships between students and sta whose role includes supervising or otherwise interacting with students as part of their job; training for specialist sta and senior leadership focused on trauma-informed investigations, adjudication, and sanctioning; and commissioning a range of dedicated external specialists to provide wellbeing support and outreach victim-survivor support services on campus.”

“Alongside this, in close working with the Students’ Union, we have redesigned our Consent Ed programme to set out clearly to students what is, and is not, acceptable and made this training required for all new entrants to LSE.”

A spokesperson from the student-led anti-sexual harassment campaign group HandsO said:

“HandsO stands in complete solidarity with the Good Law Project’s support of one of the survivors of sexual misconduct that LSE attempted to silence. We support them in their pursuit of justice and action from LSE. e support of such an important organisation such as the Good Law Project speaks to the injustice of LSE’s protection of predators and suppression of survivors’ voices. HandsO will continue to campaign against such injustice and to make LSE an environment that upli s survivors’ voices, rather than silence them and suppress them, as LSE has done with the women who spoke out against the professor.”

Angelika Santaniello Staff Writer

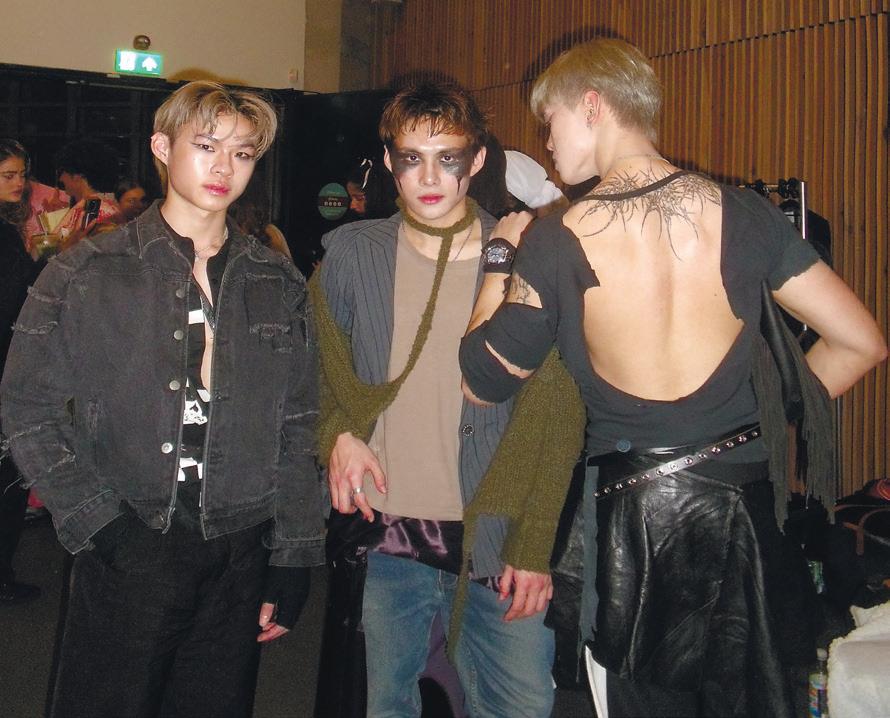

Photographed by Oliver Chan

When contemplating London’s fashion scene, an individual’s mind may consider seasonal fashion weeks, the rise of trends, and fashion’s representation of the city’s vibrant, multicultural population. Embedded within this aesthetic consumption of fashion is a vital discussion on the industry’s accessibility and inclusivity. How, on a smaller-scale university level, does one address the nuances of fashion and its problematic aspects?

e annual LSESU RAG (Raising and Giving) Charity Fashion Show took place on Wednesday 19 February, as one of RAG’s agship events incorporating both the LSE student community and London’s creative community. It aimed to address the aws of the fashion industry, presented on the Instagram page as being “not just about fashion [instead, about] making a di erence”.

Interpreting the show’s theme – ‘Reawakening: reads of Resilience’ – Sachin, the RAG Vice President, asserted in his pre-show speech that “this theme is incredibly relevant today as it represents how people can rebuild their lives on the backdrop of such horri c circumstances,” tying the show to the society’s charitable cause.

e show raised money for RAG’s three charity partners. e Sharan Project provides advice and support to South Asian women, facing domestic abuse, honour-based abuse, and dowry violence. Women for Refugee Women supports women forcibly displaced by war and persecution. Moreover, Care4Calais delivers aid to refugees at the Franco-British border.

Commenting on RAG’s support for the charities, voted for by the student body, Sachin o ered his own perspective: “ ese organisations are not passive. ey have real and tangible impact, and this is why we do what we do.”

Introducing the show, Elma, General Director of the fashion show, explained the genesis of the theme: “It started with a very brief idea of dreams and nightmares.” Elaborating on this, Anoushka, Creative Director, told the audience, “We [looked into the charities’] stories and start building from [that] it is that common thread of resilience that you have to have to face the ups and downs of life.”

Concluding their speech, they stressed: “We hope you can see a piece of yourself in the story. ere is a saying that art is stagnant, but fashion is moving art.” Certainly, viewing fashion as a “moving art” broadens an outlook on art, creating a space for individual perspectives. is nurtures a view of fashion at LSE that builds opportunities for ordinary students at LSE.

Student immersion in the fashion show spearheaded the show, notably in the space created for student-led passion projects. e Venue event opened with a performance by the LSESU Pole Fitness Society. Whispers of awe resounded through the Venue amongst the audience members, with some lming their friends who were part of the pole performance.

Amara, the fashion show’s PR Director and President of the Pole Fitness Society spoke to e Beaver about the atmosphere backstage. “We had done showcases and competitions before [but] it was a bit of an unknown,” she summarised.

Addressing the scope for integrating more sports societies into projects like the fashion show, Amara highlighted that the Pole Fitness Society “[trains and learns] these moves to perform. [Opportunities are] great because other students also get to see it. We have had people want to join us before because they have seen our performances before.” is reveals the inspirational quality of a fashion show that incorporates student-led societies that display di erent students’ passions.

Contrasting with the powerful pole performance that utilised a deep red lighting, the fashion show opened with the theme of ‘dreams’ a whimsical, tranquil opening. e enmeshing of various patterns that characterised the garments with an atmosphere of pale lighting and harp music submerged the audience in a dreamscape experience.

e ephemeral energy sharply diverted with the subsequent ‘nightmare’ section, which was characterised by more commanding walks and darker fabrics. However, these antithetical sections were complemented by more neutral tones and cooler lighting in the nal sections that used music with heavy bass beats and whimsical bells reminiscent of the rst section. e

audience was presented with the image of models with individualised walks, emanating an energy of excitement towards wearing unique, designer pieces that they felt con dent and empowered in.

However, this leads to a wider discussion on the show’s accessibility and inclusivity. To explore this, I went behind the scenes to unpick the bres of a university fashion show.

Inside the Weston Studio, where participants got ready for the show, the atmosphere was professional and supportive. Inevitably, there were pockets of stress, reminiscent of the backstage sentiment at professional fashion shows. A healthy environment was at the crux of building a fashion show representative of LSE.

Eva, a third-year IR student, modelled for this year’s show: “ ere was a casting call where we got to meet the team. I think this was a nice addition because it was less about picking who was going to walk, more [about getting a feel] for what it was going to be like. e team was really supportive, always there to listen to our concerns.”

Sophie, a model representing the Running and Athletics Society, noted that “getting involved with something like the LSE fashion show is a great way because it’s super welcoming.” Similarly, Eva noted that “sometimes [she feels] LSE

lacks the creative culture and energy”, rendering the fashion show “a [fun] way to challenge yourself and step out of your comfort zone but still in an environment that you know you’ll feel comfortable in.”

Speaking to Aman, a thirdyear Social Anthropology student and one of the show’s photographers, reinforced the role of events like the charity fashion show in encouraging creative passions among students. Aman wanted “to voice the entire event as accurately as possible. Being able to reassure models that their hard work paid o backstage a er the show was wonderful. is is a testament to the power of collaboration and has fostered my desire to pursue professional photography,” she explained.

Overall, providing an inclusive space for creative students centralises the importance of accessibility in student-led projects. Visually, a blend of abstraction and individual expression formed the lattice of the RAG charity fashion show, incorporating sonorous elements and London’s creative community to reinterpret a fashion show framework. However, RAG’s emphasis on active engagement with fashion to curate a professional environment undercut by a unique LSE spirit and sense of familiarity shaped this year’s fashion show as a vessel for embracing fashion’s inclusive and accessible potential.

Alexander Bray Contributing Writer Illustrated by Paavas Bansal

Is LSE Economics Education Fit for the 21st Century?

According to the Complete University Guide, the London School of Economics and Political Science is ranked second in the United Kingdom in economics, which makes sense for a university with ‘economics’ in its name.

Does this re ect the ability of Economics at LSE to tackle some of humanity’s greatest modern challenges, such as climate change, universal access to basic goods and services, and societal inequality? is was the subject of a national report by Rethinking Economics UK, examining if ‘economics education [is] t for the 21st century’ among twenty universities, including LSE.

What does a 21st century ‘economics education’ look like?

e National Report makes four recommendations to all universities on how to make economics education t for the 21st century.

Firstly, they recommend changing the way that students are introduced to the discipline of economics. e dominant economic school of thought is ‘neoclassical economics’, which is taught at introductory microeconomics courses as if it were the foundation of all economics. is narrows down a student’s experience of economics as simply models of rational agents following the invisible hand of the market, where if something is not priced, it may as well not exist.

is contrasts with economic history, where gi economies, not markets, used to dominate smaller societies, built on the basis of good will towards one’s neighbour. Pricing anything and everything also reduces

the complexity of analysing social, cultural and environmental impacts of policies, making them seem ‘cheap’ compared to people’s experiences or even scienti c reality. As the neoclassical school aggregates micro into macro, these biases continue throughout economics degrees, creating and perpetuating the assumption that economics only has one method of thinking.

In contrast, the report recommends that “economics departments restructure undergraduate economics education by introducing new models that replace the overarching binary of microeconomics-macroeconomics in the rst year of study”. e Uni-

cation’ is moving away from hegemony (the dominance of one school of thought in a discipline) and moving towards pluralism (the consideration of multiple schools of thought), so that students can learn, discuss and critically assess ecological, feminist, decolonial, Marxist, institutional, and post-Keynesian schools of thought, alongside the neoclassical school.

irdly, the report recommends changing economics assessment to be far less dependent on mathematics exams and the regurgitation of information, but rather to “prioritise critical thinking, collaborative work and individual research projects”. Re-

‘Critical thinking will be the priority, rather than solving model equations ad nauseam.’

versity of Sydney, for instance, runs courses in Political Economy, where the introductory module ‘Economics as a Social Science’ examines multiple schools of economic thought, their assumptions, and their broader contributions to economics, without separating micro from macro so rigidly. More broadly, they recommend that economics education engage students in debate and discussion on inequality, the environment, and power relations. Critical thinking will be the priority here, rather than solving model equations ad nauseam.

Secondly, the report calls for the decarbonisation, decolonisation, and diversi cation of economics learning. ‘Decarbonisation’ is teaching that economic systems are fundamentally embedded in ecological realities, making the environment matter beyond negative externalities in a market. ‘Decolonising’ is recognising that there are historical and contemporary inequalities perpetuated by colonialism, where the Global North has economically bene tted from imperial relationships with the Global South. Finally, ‘Diversi-

community supporting it. ese economists, who “[did not] appear not to read anything that’s not published by an economist”, refused to accept any criticism from medical professionals, claiming that the latter had “little understanding of rigorous research methods”. Democratisation of economics also includes better consultation with students on how to change economics curriculums for progress.

modules, where one includes ecological economics.

ferring to academics outside the economics discipline to teach di ering perspectives and considerations is also encouraged, and the report particularly praises the approach of the LSE100 module to foster interdisciplinary thinking and discourse.

Finally, the report recommends democratising economics by better consultation with students on how to change economics curriculums for progress on the above goals. It also advocates for economics students having more options outside their primary subject, as it will “[help] dispel the myth currently conveyed to students that economics is apolitical”. Interdisciplinary teaching would also reduce the ‘arrogance’ associated with economics being a ‘superior social science’.

For instance, economists Jennifer Doleac, Anita Mukherjee, and Molly Schnell conducted a study that argued against harm reduction (substituting opioid consumption for safe heroin injections to reduce the risk of addicts contracting HIV) despite the World Health Organisation and the wider health

e report places LSE as a university that “need[s] a wake up call”. In particular, it highlights that mainstream economic theories dominate the BSc Economics course, which “comes at the expense of learning real-world economics”. One notable exception is the LSE100 programme, which engages in interdisciplinary approaches to project research, including ecological economics for the climate futures option.

e BSc Economics course heavily prioritises quantitative methods and their thorough examination, particularly in third year modules. Wealth and inequality are covered by six out of nineteen modules, but critical questions of historical slavery, colonialism and neocolonialism are only discussed in one module. e environment is covered in three

Overall, LSE seems to do well compared to most universities, but its major focus on the neoclassical school, particularly in compulsory modules, risks causing students to think that economics is an objective, straightforward ‘science’ that operates by solving models to the world’s end. is contrasts with the truly rich variety of perspectives that exist in economics, particularly in heterodox schools. e disengagement and boredom of students in economics classes is noticeable, as economics teaching expects them to solve maths puzzles without much critical thinking or creativity. ‘Mentioning and forgetting’ assumptions causes students to accept them, despite their lack of basis in the real economy based on regular people’s lived experiences.

As many LSE economics graduates go on to control vast sums of assets andnancial resources, it would perhaps bene t them and the world to understand and critically assess multiple perspectives on how those resources are allocated, rather than be intellectually deprived with our current, singular thought curriculum.

Saira Afzal News Editor Photographed by Saira Afzal

LSESU RAG’s ‘Take Me Out’, or, why are LSE students so single?

How do LSE students nd love? Can a hopeless romantic survive dating culture at university? LSESU’s Raising and Giving (RAG), the charity branch of the Student Union, collaborated with Imperial College’s RAG for a ‘Take Me Out’ contest, based on the axed British dating game show. LSE and Imperial contestants were brought on stage to impress a line-up of students and earn a date with one of them, making for a lively night with an electric audience. But what does an event like this tell us about dating culture at LSE, or at university in general? And what do couples on campus say about their experience nding love?

‘Take Me Out’ was particularly fun to attend as an audience member, screaming when couples would say ‘yes’ to each other, or collectively gasping when

the panellists on stage popped their red balloons before the contestant had a chance to defend themselves. Many of the questions were light-hearted and funny (think hot takes, red ags, green ags), and some eccentric characters brought out big laughs from the crowd.

One LSE student opened his time with a drawn-out card trick, not seeming to impress many female panellists. Most of the girls popped their balloons early on, seemingly over trivial things (“I prefer tea over co ee”), throwing plenty of single sh back into the sea. In the end, there were a few successful couples who got a roar of applause from the crowd a er pairing together, like one couple who bonded over their mutual love of McDonalds.

Later, a contestant from Imperial strided onto the stage, blasting ‘Can You Feel My Heart’ by Bring Me e Horizon; yet, he was quickly humbled by the panellists who all popped their balloons. He didn’t leave the stage without dropping to the oor and doing some push-ups, making

‘I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad with dating apps. e problem comes from them trying to monetise.’

for an eventful end to the Take Me Out. Overall, the event was “way better than expected” according to LSESU RAG coordinator Marion. She said the “audience and hosts were amazing”, and hoped to do the event again next year.

While most of the questions aimed at contestants were silly and playful, some common trends at the event reveal important things about dating culture at LSE. For example, some students are concerned about their potential partner’s future. One contestant asked all the panellists about their plans for the next ve years. Another contestant said he liked women with “ambition” and future goals a er university. Secondly, age gaps can be icky for some. One Imperial panellist popped her balloon a er hearing the LSE contestant was in their rst year, herself being in third year. While 18 and 21 could be a small age gap for some, others nd it to be a dealbreaker in a potential relationship.

An event like ‘Take Me Out’ only tells us so much about student dating culture. What is it really like to date while at university? Jake* and Lilly*, both LSE students who met at freshers week, eventually became a couple through meeting in-person and staying in the same student accommodation. Considering dating life has gradually moved

‘ ere are more “happily and unhappily single people’” at LSE who want to focus on their career and future, or “happily in-love people who did not meet their partner at university”.’

into the digital space over the last decade, Lilly highlighted some important di erences between meeting a partner in-person versus via an app.

“Meeting someone in person is a friends-to-lovers situation, gradually getting to know them more based on a conversation. Whereas, on a dating app, you kind of arbitrarily bond with someone based o of their interests—which might be performative, since they want to [show] the traits that will get them attention,” she said.

Jake disagreed: “I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad with dating apps. e problem comes from them trying to monetise. Dating apps are a great way for people to meet in this day and age. So long as both people take it genuinely, I don’t see why [dating apps] could be bad. e app is just a replacement for meeting them [in-person].”

Natalie*, who met her boyfriend through Hinge, described her dating app experience as similar to TikTok, due to its algorithmic nature: “Hinge gets your physical type down very quickly. It’s a good way to meet people but it is messed up.”

Another interviewee, Julie*, met her boyfriend during boarding school. She also agreed that nding relationships through an app is “less organic” than meeting someone in-person. Julie described dating culture at LSE as “non-existent” and “long-distance”. She believes that generally, there is a lack of romantic expression and dating at LSE. Movies and books present an idyllic image of the ‘university dating life’, nding your ‘university sweetheart’ and transforming them into your life-partner. For Julie, there are more “happily and unhappily single people” at LSE who want to focus on their career and future, or “happily in-love people who did not meet their partner at university”.

Does this mean dating culture at LSE is uniquely lacking? According to Julie, “corporate culture and career-focused environment at LSE makes it less conducive to a ‘college sweetheart’ life”, but many university relationships are long-distance.

“I think maybe, people at LSE see each other as colleagues rather than life-partner potential; it’s just like, we’re students focussed on our studies and careers terests—it’s slightly more formal”.

*Names

have been changed to preserve anonymity

Jessica-May Cox

Part B Editor

Illustrated by Sylvain Chan

There comes a time in every woman’s life where she must grapple with the ultimate conundrum: do I want to have kids? ‘Every’ woman is de nitely an exaggeration, but most conversations about children that I have with my girl friends o en end similarly—we genuinely do not know if we want to have kids.

As a university student in Britain, I’m lucky enough to even be able to consider having kids as a dilemma—a choice many do not have. Yet that is what makes this topic all the more relevant: as women’s rights (hopefully) continue to expand, and we become more mired in the freedom of choice, I hope more of us are able to fully engage with this thought experiment.

So why would I want to have children? I think the main motivation, at least when I was a teenager, was that it was a faraway, normal milestone that everyone should aspire to. Even though this was de nitely not my Chinese mother’s experience, she still drilled a roadmap into me from a young age: go to a good university, meet a (preferably rich) guy, marry, and have kids. Great, easy! Well, my nal year is coming to a close soon, and I’m in a longterm relationship with a very reasonable guy…and I care for this arbitrary milestone less than ever.

Admittedly, my main reason for this is that I am the one who has to deal with being pregnant and giving birth. is is what puts o most women in my generation; if we have the option of just not su ering one of the most painful things in human experience, why on earth would we go through with it? You have to spend one year (if you only have one child) of your eeting life in constant

discomfort and then, even with modern medicine, there may be irreversible consequences. On top of all this, how am I supposed to maintain the ideal female body that society wants me to keep? It’s quite unfair, I say.

I’ve heard a few parents comment that re-experiencing life’s wonders through their child’s eyes is irreplaceable. I can understand that sentiment, but it still doesn’t sit well with me. In an ideal world, surely you would have children for reasons less sel sh than vicariously living your life through them? Perhaps those people who think wanting kids is the result of a natural drive are correct; it’s not necessarily a bad thing, and we are all just fumbling around for a more morally upstanding, profound cover-up. Except, we know that isn’t true.

e idea of a biologically intrinsic ‘maternal instinct’ is empirically dubious, as it historically arose from a need to control women and push us into a traditional family structure. It doesn’t take extensive scienti c literature to see this: for example, a er deciding that women were inferior rst, Aristotle attributed this to the fact that we, apparently, have fewer teeth than men. Despite being veri ably untrue, it represents how men have always started with a political standpoint, and then invented a fact about women’s bodies to justify it. If we believe that we should have children because of a ‘maternal instinct’, then we are slipping further back into patriarchy’s tiger-like grip.

is is why I approach any desire to have children cautiously, because I’m fully aware that I could just be cornering myself into a kitchen-shaped prison a er slaving away at my day job. Even though women have achieved some degree of economic independence in the capitalist system, patriarchy’s exploitation persists at home. A er all, besides breadwin-

ning, we remain obligated to do most of the child-rearing and domestic labour on average, all for the sweet price of nothing. So to have children is to fall into the unfortunate trap of a foul, exploitative system. You can’t blame me for being absolutely terri ed of this notion.

I appreciate that not having children so as to not uphold the patriarchal and capitalist system is a big jump, but we cannot just ignore the enduring link between the personal and political because it is uncomfortable or inconvenient. Yet it is also ridiculous to expect me to sacri ce a potential for increased happiness because of some esoteric desire to topple the capitalist system. Let’s be real: unless you become a world leader, we will only ever be able to a ect our immediate surroundings. So let’s just take it one step at a time: I think we should focus less on gesturing at vague righteous notions, and

etc.) then your life will be an unending, sisyphean nightmare of work. Having seen both my parents work two jobs just to a ord my weekly dance lessons makes me think that, especially with the increasing cost of living that our generation faces, raising a child with limited nancial resources is an unfair deal for both parties. is thought process seems rational on the surface: if you cannot a ord to have kids, don’t have kids. But that sentiment is inevitably a classist one, even if we don’t intend for it to be. Considering that class is predominantly a structural issue, expecting lower class people to ‘be responsible’ and abstain from having children is, quite frankly, a little eugenic.

However, another valiant concern my sister raised was: our planet is literally burning, and even our generation will su er the disastrous consequences

many generations we pass, we just cannot seem to get it right. Not to the inherent fault of any parent, but it’s impossible to raise a human who is not messed up in one way or another. If a child doesn’t consent to being born, why would I force them into such a miserable existence?

I now disagree with this extremely pessimistic view. If anything, it makes me consider if having children might actually be a good idea. It’s true, I didn’t ask to be born, I’m worried about the climate, and I’m far from a perfect person. But despite our chronic tendency to fall short, there is so much to be gained from the striving of perfection; it is core to the human race. To be alive is incredibly rare, worthy of treasure and awe: according to some funky calculation on the internet, the chances of you just being born as you are (and not involving all the socialisation piled on top that rounds you out as a person), is 400 trillion to one.

As somebody who has struggles but absolutely loves being alive and experiencing things new and old, perhaps bringing another person into the world to forge their own path, to see what they can achieve, and to share in that happiness is reason enough.

Ann Yi Ngai Contributing Writer

Looking out the window of my mother’s car, a striking campus came into view—it boasted grandiose, modern structures elegantly dressed in the o cial school colours, with the school’s coat of arms haughtily stamped across the tallest building. Several football elds spanned plenty of acres, with diligent sprinklers nursing the grass to maintain its lushness; straight fences erected around campus, broken only by imposing guard houses. Sometimes you could spot luxury cars gliding in and out of campus dropping o their young inheritors at the boarding houses scattered across the depths of the campus.

ough I had been attending this school for over six years, the sight never failed to evoke a sense of guilt and indulgence. Its imposing, polished disposition clashed violently with its surroundings consisting of half-furnished, unkempt shop lots, uneven streets, open drains, broken down cars, stray animals, and barren construction sites.

Stepping foot into school meant trapping yourself into a bubble, a vacuum—a world that revels so much in its own su ocating air.

As hyperbolic as it sounds, it is an attempt to recreate my own experience at a British international school in Malaysia. e international school industry has been a well-es-

tablished one in my home country for decades now, with the oldest British international school being founded in 1946. e appeal of British education in Malaysia in particular comes from a number of places. Parents who choose British international schools over local education may cite greater chance at university acceptance, better employment opportunities, or wanting a more well-rounded education for their children than what local schools can provide. A er all, learning English was the way to climb the social ladder. It is why the British international school to UK university pipeline is so entrenched, and why I am at LSE.

While I recognise my privilege in being able to come to LSE as a Malaysian, I still feel a sense of lingering resentment and frustration—an inkling that I have betrayed parts of my cultural heritage and national identity. rough my years rehearsing to pursue opportunities overseas, I started to realise that I have been participating in a chaotic arena of neocolonial politics: learning the rules of the game, the slick manoeuvres, the scheming from the moment I stepped foot into that glorious campus.

Tuition fees for British international schools in Malaysia can go up to RM100,000 (around £17,640) per year, almost the life savings for an average Malaysian. It is decidedly not a choice that everybody has, and exacerbates Malaysia’s deeply embedded economic and racial division. Malay-Malay-

sians and indigenous peoples, or Bumiputera, make less than three-quarters of the income of Chinese-Malaysians. ese ethnic divisions can be traced back to colonial times and attributed to British colonial divide-and-rule strategies, which le some races more de nitively a uent than others. In response to this colonial legacy, a rmative action policies, collectively known as the NEP, were implemented by the government in 1971 to combat these persistent racial inequalities. is involved introducing enrollment quotas in national universities that prioritise the Bumiputera over the Chinese and Indians; with the odds stacked against them the latter feel pushed to seek out international schools in order to get into UK universities instead. And amongst the interracial and economic grievances, the UK continues to embrace and bene t from its legacy through service exports and exorbitant international tuition fees.

What exactly makes British education so appealing aside from escaping racial quotas and gaining economic advantage? For those who can spend more than a buck on their children’s education, British international schools stand as status symbols in front of family or friends. Beyond that, there is something to be said about the contradictory ideas of ‘Western-ness’ in Malaysia which perpetuate a ‘curated’ form of colonialism. On one hand, there is great resistance towards the erosion of ‘Malaysian culture’ through the imposition of Western values, which is o en accompanied

with impassioned debates about LGBTQ+ rights and white saviourism, among other colonial evils. On the other hand, there is a quieter, more subtle ‘Anglophilic’ aspect— the continued championing of English over other languages and the glori cation of private British education. Proximity to and characteristics associated with British education act as various forms of cultural capital that a large portion of the elite still prize. Completion of school at a private British institution acts as embodied, objecti ed, and institutionalised cultural capital – from pro ciency in English, to certi cates needed to apply to UK universities, to having been to a school that has accreditation from COBIS – all of which facilitate upward social mobility.

Even within the microcosm of the British international school I went to, these white-coloured glasses are put on. From the mistreatment of local teachers juxtaposed against the greater visibility of white teachers to adverts heavily featuring a white kid regardless of the ad’s content (with the non-white students in the background scoring DEI brownie points), British international education panders towards the Anglophilic gaze. It does seem ironic though, as there is a sense of tired contradiction in feeling like you are constantly being alienated and exploited for your identity by a foreign institution in your country looking for pro t, to whom you feel helpless to give huge sums of money anyway… Did I mention the frequent racist comments made by white teachers

• Publicly boo at people who vape and smoke - Anonymous

• If you wear tight jorts you should also be publicly booed - Suchita

who got away scot-free?

e most troubling implication for me, however, is the role of former colonies in upholding this neocolonial legacy. How much is the Malaysian state accountable for it? How much actual agency do we have? e tightrope between neocolonial structure and postcolonial agency is in constant tension in Malaysia: if we comply with the Structure and sing its praises, we attract more direct investment from the UK, climb the ranks of economic development, and get a little closer to our decades-long desire of becoming a high income country. How sustainable is this compliance, however, when the British international school to UK university to overseas employment pipeline, but more speci cally the interracial inequalities that prop it up, is one of few factors contributing to high levels of brain drain in Malaysia?

I don’t pretend to know what postcolonial Malaysia means, but I do believe we are not quite there yet. Inequalities in race, class, and mobility continue to be persistent features of the Structure le behind by an Empire with a fetish for division. At the same time, I can’t blame the Malaysian government for projecting an illusion of progress; for no matter how much I lament over my postcolonial heritage, I feel helpless, unable to forfeit the rules of the (neo)colonial game.

Read full article online.

• Nobody wants to see your butt busting out of your tight chinos, Finance bros - Anonymous

• People who hate on speci c clothing items just do not know how to style them - Syl

• @lsememez on Instagram is borderline harassment - Saira

• I STILL think Korean food is trash - Anonymous

• e appeal of milk before cereal is that the cereal doesn’t get soggy - Syl

• Cereal is SUPPOSED to be soggy! - Aaina

• People who are short should stop complaining about being short - Lucas (175cm)

Aaina Saini Opinion Editor

In 1947, India was le to pick up the pieces of the Partition—the tip of the iceberg of a colonial legacy which had determined the course of the subcontinent for over 200 years. India was amputated into divided nations, and migration and mass killing ensued. Yet the government of newly independent India still conducted an extensive census exercise to document the situation of each of its citizens just four years later.

In 1971, when India was kneedeep into the Bangladesh Liberation War and mobilised its army to defend a neighbour, a team of remarkable statisticians still oversaw the census. And then the Indians found themselves in the grave economic crises of 1991 which threatened bankruptcy for almost 800 million people. Yet the census was still conducted.

In 2021, for the rst time in

‘If

elections in populous states in India during COVID-19 such as Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Bengal, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh which saw congregations of thousands of people—where our beloved Prime Minister, Narendra Modi himself campaigned must be quite safe.

And of course, to question the hosting of the Kumbh Mela, – a large Hindu religious pilgrimage festival during the second wave of COVID-19 in 2021 which attracted a record amount of 3.5 million people – must mean I am a bad Hindu!

So, what is Narendra Modi so afraid of? Everything. It’s as they say, out of sight, out of mind! If the census were to be conducted, the idyllic image of a perfect ‘Hindu Nation’ with no poverty and increased bene ts from GDP growth to each citizen he has sold to the Indian population for the past 10 years will come crumbling down.

is Hindutva-frenzied gov-

the census were to be conducted, the idyllic image of a perfect “Hindu

Nation” with no poverty or increased bene ts from GDP growth to each citizen he has sold to the Indian population for the past 10 years will come crumbling down.’

the history of independent, or even colonial India, the decennial census has been postponed. Now, more than once. Fine, they said they couldn’t send enumerators home during the COVID-19 pandemic for the safety of the citizens; we understood. However, now standing four years a er the scheduled date of the census, little e ort has been made to conduct this long-overdue exercise.

is naturally makes one wonder if this is a deliberate move by the populist Hindu-nationalist BJP-led government. If safety was as paramount as one is forced to interpret by constant data collection delays, then I guess conducting

double standard is palpable when you consider that the Hindu population rose from 303 million to 966 million in the same period—a ve times greater increase.

e aversion to a census by the BJP runs much deeper than dismantling their distorted views on Indian religion statistics. It’s not just the census data that is lacking—the Modi government has actively led an age of misinformation and lack of credible datasets. Whether it be the lack of information on how many migrant workers perished in commuting back home during 2020 or the shortly a er seen deaths due to lack of oxygen in hospitals in the second wave of Covid—the point is the government either has no idea or refuses to share the data in an attempt of face saving and it is hard to argue which alternative is worse.

new census to add new beneciaries—one which I believe is never to come.

Furthermore, the demands for a caste census that would shed light on social mobility in India for historically marginalised communities are increasing by opposition parties in Parliament and the BJP staunchly refuses to conduct such an exercise claiming that it shall lead to divisive politics, which I call bullshit. is peace-loving BJP has already done enough for the ‘unity’ of the nation and it must stop now.

National Statistical Survey Ofce (NSSO) used to collect for industries, severely impacting the policies designed since most of them rely upon estimates and projections—all of which remain unveri able. National Crime Records and road accident statistics are just a few examples of the union government data that continues to remain unavailable and, as an economist, I continue to ask year a er year: where is the data? In such an ethnically divided country, what kind of e ective policy in 2025 can come from population statistics collected in 2011?

ernment has signi cantly bene ted from the racial divides set up by the colonial government to earn the favour of India’s largely Hindu majority. ey put the second-largest religious community in India under the bus, accusing them of stealing jobs. In one of his election campaigns last year, Modi referred to Muslims as “in ltrators” and “those who have more children”, implying that there is a signi cant increase in the number of Muslims in India that threatens the jobs of ‘Hindu natives’.

However, critics of government statistics prove that between 1951 and 2011, the Muslim population rose from 35.4 million to 172 million. A noteworthy increase for sure, but the

A WHO report suggests that 4.7 million people died as a result of the pandemic in India—10 times more than ocial statistics suggest. So much for the safety of the people I guess!

To add further shame, the Indian government outrightly denied such gures. When met with resistance and asked to provide their own, they met academics with the same response: we do not know.

e question ultimately boils down to ‘what DO we know?’

We do know that the people of India are hungry and are denied access to food due to the government’s constant failures. Bene ciaries under the 2014 Food Security Act are based on the 2011 census, where it is estimated that 100 million people have been excluded since the government conveniently claims that it shall wait for the

Prolonged conversations about whether to include a caste census or not to the list of census questions is yet another tactic to delay the information we demand. While a caste census shall disclose valuable information; it is pointless if such deliberations only lead to a further data lag and could possibly be something that could be picked on in future censuses. What we need right now, is even an iota of real, credible data that the nation can use to bring its people, whose views on politics are clouded by false data and propaganda, out of the dark.

Last summer, I worked as a research intern at government think tank NITI Aayog (literally Policy Commision in Hindi), where I discovered that we no longer collect consumption data. We do not collect several other forms of data that the

Bad data, or lack thereof, leads to bad policy. And I, as an Indian, have had enough bad policy. I think the ultimate point is—it’s a shit show. It isn’t happening. e constant postponement is not circumstantial but deliberate, and deliberations over the caste census (possibly well intentioned by the opposition) do nothing but kick the can down the road, keeping Indians away from the truth for as long as it possibly can.

What is at stake is credible data for an entire decade, one which has been marked by a signicant governance shi and with no data to document the true e ect! is shi has disastrous e ects on India’s population, but really, seems to suit Mr. Modi just ne.

Many agree that simply nishing the task is the “most e ective way of dealing with the source of stress.”

Spending time with friends had the most positive e ects overall. Whether it’s playing tabletop games or going to the pub, being with others in social contexts can help “separate (your) brain from university”. ree students also mention the importance of having such a support system, as it’s “nice to know you’re not alone”.

Crying can be “good to relieve your emotions”, but other times it can make it worse as it “exacerbates (the) pain” and gets you “stuck in (your) own head and sadness”.

Alcohol is a “natural relaxant”, and “sometimes you need a feral night out” to take your mind o things. It “can be sustainable as long as it’s not something you do o en, or over-rely on.”

Second year can be tough: graduating from the safe ‘trial phase’ that is rst year, as academia and one’s future prospects become of utmost concern. But how well do LSE students cope with these challenges? is multimedia spread aims to investigate causes of stress within 25 second-years, and the extent to which they e ectively cope with these issues.

Read the article and the data online:

Going to the gym, reading, and daydreaming are all methods one can use to relax. Giving yourself time to recharge is not bad in moderation, but has the potential to be destructive if you are simply “cooped up in (your) room”.

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” was the mentality one student had when describing her struggles with dealing with stress. For many, stress is a cycle. Even if you nally complete that looming assignment, or nally send o that internship cover letter, any moment of relief is then “immediately replaced by more stress”.

Caught between academics, the need to consider future prospects, maintaining interpersonal relationships, and managing their daily chores, the second-year life can appear as an endless obstacle course with no end in sight. e interviews reveal these issues can be compounded by factors out of one’s control, which make dealing with these problems more di cult. For example, “bad teachers”, “impersonal teaching environments”, and tightly packed deadlines, can demotivate students and heighten academic pressure. Moreover, when socialising becomes a conscious e ort one must make, as to not worry your family or become isolated from your friends, it can get overwhelming. ere are simply not enough hours in the day to be on top of all these responsibilities.

erefore, one must imagine Sisyphus happy. ese struggles are part of life — part of adulthood — as dismal as that may sound for some.

To prevent these issues in our lives from getting the best of us, we must adapt and face these obstacles head-on. For example, “getting your foot through the door”, and doing even the most minor of tasks, can help you work towards completion. A erall, “it is the initial hurdle” that discourages people from striving forward, causing many to fall into an unhealthy loop of procrastination, stress, and unproductivity.

EDITED BY SKYE SLATCHER AND JO WEISS

by JOHN LEWIS & DAVID KNIGHT

A Note from the Editors: We are thrilled to be able to feature an article from the 1979/80 1st XI. We are especially grateful to John, David, and Martyn for their work on the piece.

Nearly 45 years ago in May 1980, e Beaver covered the exploits of the all-conquering LSE 1st XI Football Team of the 1979-80 season. For the rst time in our esteemed history, the LSE ‘Firsts’ had won something. In fact, the team, of which I was a member, did ‘ e Double’, winning both the London University Football League and the Challenge Cup.

at is a feat that (as far as I’m aware) remains unmatched. Some of the same players from the Double-winning team did win the league again in the 1981/82 season. Far more recently, the league was nally won again by the Firsts in the 2022/23 season. However, another Double has remained frustratingly elusive.

And that’s absolutely ne. It would be great if LSE had a tradition of success down the years, but, quite frankly, no one applies to attend the best university in the world for the football. But I suspect that another thing that was true back then still holds true today: so many of us achieve so much more whilst we are at LSE because of the football.

Late last year, it struck me that with the 45th anniversary of our team’s success approaching, it was an opportunity to celebrate our unique achievement and to reconnect with my old teammates. It meant tracking down my fellow players with the help of the one teammate I was still in touch with, Nigel Hopkins. And from the LSE itself, in the form of the Alumni O ce. I am delighted to say that we made it happen.

On 22 February, most of the original 1st XI, with a couple of welcome additions, met up and, in time-honoured tradition, took the train from Waterloo to New Malden – the home of our past glories and still the home of LSE Football – to watch the current LSE 1sts play their nal league xture of

this season – and ‘thrash’ Imperial 3-2 – whilst sharing our own unreliable memories.

It was a wonderful occasion, which was only made possible by the support that Nigel and I received from LSE’s Alumni O ce and the LSESU Athletics Union (AU)—especially from AU Secretary Matt Carl and Will Warren, the 1st XI captain. I am delighted to report that we found the AU and the LSESU Football Club (now an unbelievable seven teams strong) to be in very good hands.

Mind you, that is coming from a couple of profane and degenerate punks of yesteryear. When we weren’t playing football, beating everyone in sight, some of us were at gigs, watching Joy Division, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and a new band called e Cure. And during our time at LSE, the most headline-grabbing punk band e Sex Pistols released their only album, Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s e Sex Pistols, which Nigel and I referenced in the title of our shoutout message to old teammates. Or would have done, if it hadn’t been amended by the Alumni O ce, due to our use of the ‘B’ word. I did explain that back in the day, the cover was neither illegal nor censored and, in fact, regarded as a cultural landmark. But they would not be swayed.

Nevertheless, we still tracked down some of those old punks, post-punks, and the rest of the team, and it was marvellous to discover that our teammates have gone on to enjoy long and rewarding careers, happy lives, and rewarding relationships. While neither success at LSE nor on the football pitch can absolutely guarantee you the good life, it appears that putting the two together certainly helps.

However, it’s important to add that bringing the ‘old boys’ back together also involved some real sadness, with the discovery that one of our number was no longer with us. Just a week before the reunion, we heard the devastating news that John Glennon, our team captain, passed away last year. John was so important to the team—as a player and person. He was at the heart of most of our extraordinary memories—some unreliable, but most of them true.

We raised a glass to John on February 22—a poignant moment during a very happy day. And we will be staying in touch with each other, hopefully meeting again in future. We have rediscovered old friends and that punk spirit is certainly still there among us.

We wish everyone who joins the AU and plays football, at whatever level, during their time at LSE a great future and rmly believe it is the best decision you will ever make.

With special thanks to Skye & Joey, LSE Library Services, and the LSE Digital Library.

by MARK WORANG

Dubbed as a ‘sleeping giant’ Indonesia’s National Football team presents a newly optimistic vision for fans sharing the love of the game. A window of opportunity has emerged for the nation’s golden generation to showcase their ability, capitalising its chances within international tournaments.

Following the appointment of Erick ohir as Football Association of Indonesia (PSSI)’s incumbent chairman, breakthroughs spanning across –gender with women’s football and age groups from junior to senior level – are visible with prestigious achievements including its debut milestone winning the 2024 AFF Women’s cup. His primary goal (pun intended) is long-term progress and attainment of reaching the FIFA World Cup. Deconstructing it further, he aims to achieve this objective through rigorous structural and systemic development – of the team’s programmes, players, and sta , whether managerial or coaching – to ensure a multidimensional approach which his predecessors have failed to recognise.

Prior to leading the country’s football organisation, Erick has demonstrated gi ing within the realm of the private sector and public administration. With an eye for talent, he began owning international and domestic sports giants namely – Inter Milan, DC United, Oxford United, Persis Solo for football, along with Philadelphia 76ers, and Satria Muda for basketball –consolidating his presence in the national and global stage. Equipped with a shiny track record and global network, he earned his place in power a er proving himself through hosting the 2018 Asian Games and campaigning for seventh Indonesian president Joko Widodo, securing himself a spot as a government minister of State-Owned Enterprises before being ordained with authority to lead Timnas Garuda.

is narration will highlight key themes representing Indonesia’s success and future, whilst agging the barriers preventing Indonesia’s move forward. It will begin by discussing pivotal moments during the 2024 U-23 Asian Cup and end with the prospects Indonesia possess moving forward.

Crediting the sorely missed Korean manager Shin Tae-yong, the upbeat of the national team began in Qatar, where it revealed the striking potential of Indonesian youth. Challenging a tournament favourite Australia, Ernando Ari started the game with an early critical penalty save against Mohamed Toure a er a handball from Komang Teguh. Redeeming himself a er the foul, Teguh then capitalised a beautiful slice volley from the naturalised Nathan Tjoe-A-On securing the rst three points during the group stage. Snowballing ahead with momentum, Indonesian wonderkid Marselino Ferdinan set the tone with the Jordanians through a successful penalty execution. Known as the Batman and Robin duo Marselino and Witan Sulaeman scored two more times with con dence including a goal of the tournament candidate.

Among the three Indonesian Rory Delap style set-piece takers, Pratama Arhan also displayed his signature powerful throw-in, assisting a header

for Teguh sealing the deal in a 4-1 victory leading to the knockout stages. Faced against incumbent giants South Korea FIFA ranking at least 100 places above Indonesia, Rafael Struick showed up as the consistently capped number nine, with two goals ultimately reaching a draw nishing extra-time. With a nail-biting shootout and synchronised cheering from passionate supporters of the national chant “Yo Ayo, Ayo Indonesia”, once again Ernando saved Lee Kanghee’s shot and Arhan won with a ticket to the Semi-Final against Uzbekistan. Although this meant that Indonesia had secured another place for the same biennial competition, a victory in the next game was necessary to obtain a place in the 2024 Olympic Games. A er a series of controversial referee decisions, including a disallowed goal from a questionable VAR o side angle position, Indonesia’s peak performance was cut short. It continued to a streak of losses against Iraq for third place and then Guinea for a seat in the Olympics stage with more unfair value judgement from FIFA in the Stade Pierre Pibarot. Despite Erick’s best e orts to – create appeals, as well as sitting beside Gianni Infantino, motivate management and his team – the critical juncture had closed, but this allowed creation of precedents for the new lineup.

READ THE REST OF MARK’S ARTICLE HERE:

James Cook MBE recently spoke at the LSESU Sports Business Conference about the social impact of sports. He shared re ections and stories from his career as a boxer, during which he reached the titles of European and British super middleweight boxing champion. Now, he focuses instead on the Pedro Youth Club in Hackney. James and Paul shared insights into the work that the Pedro Club has been doing since 1929—it has a deep history within the community as a space for kids and a hub for everyone. Focused on boxing as a way to develop a far wider skillset than just physical strength, the Pedro Club is now looking to secure its legacy for a further 100 years, in an improved building. e work they have been doing is incredible and we now have the opportunity to support them. You can read more about them on their website.

If you are able to donate, the relevant information is here: National Westminster Bank Sort Code: 60-09-23 Account: 75067749

e Pedro Club would like to say a huge ank You in advance to anyone who is able to donate.

EDITED BY SOPHIA-INES KLEIN

AND JENNIFER LAU

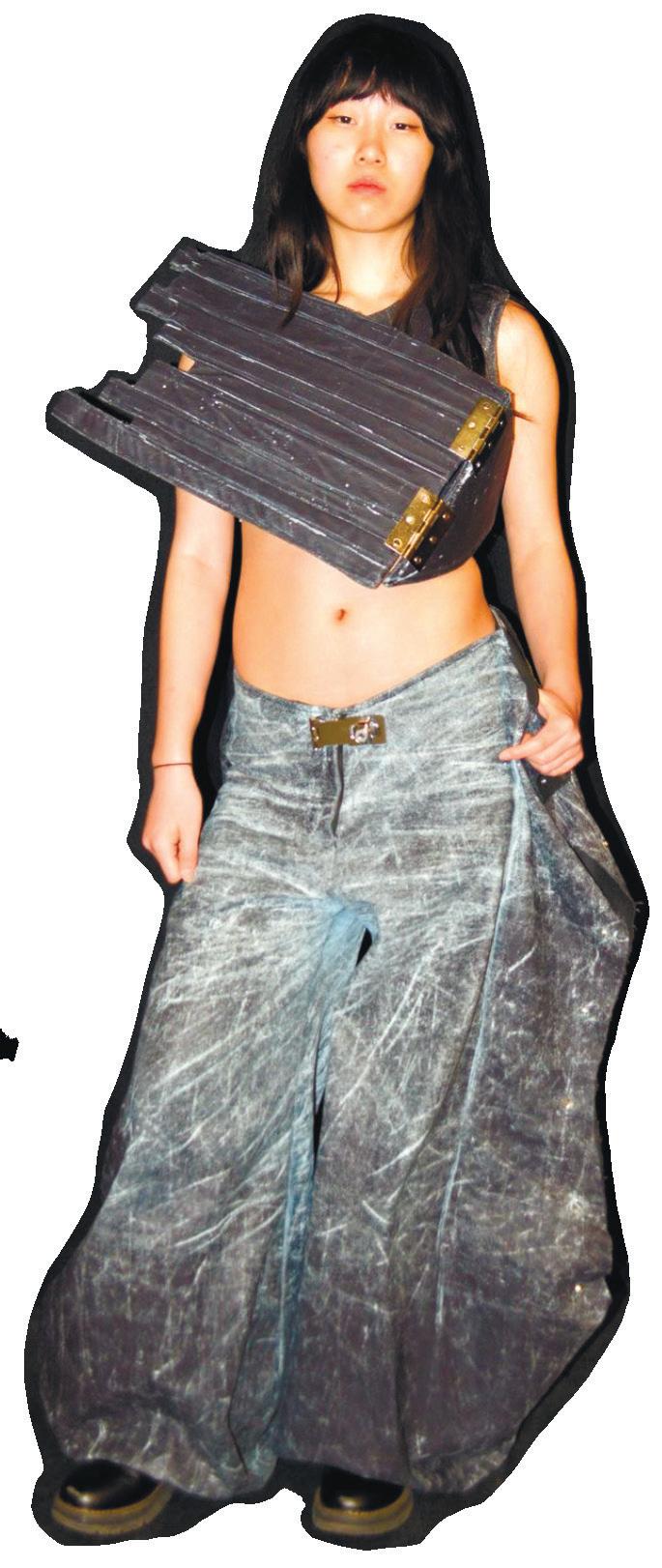

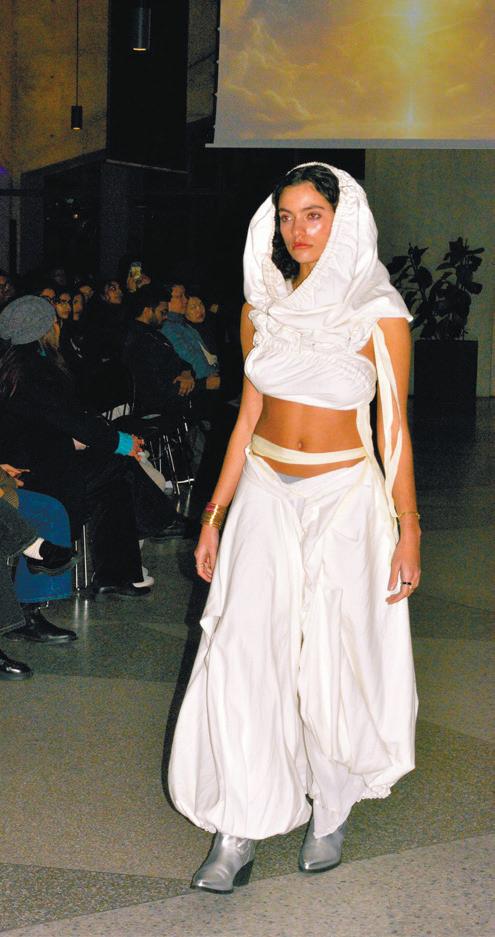

In the height of fashion week season LSESU’s Raising And Giving Society (RAG) has put its name on the schedule with its third annual fundrais ing fashion show ‘Reawakening: reads of Resilience’. Curated as a re ection of the journey of reawakening that nds its way into each person’s life, the lineup brought this to the runway through four themes: e Dream, e Fall, e Struggle, and e Rebirth, each de ned by a distinct and unique energy and artistry.

e fashion show stands out as one of the bold expressions of the student body’s creativity. In a university where the arts are o en overlooked, RAG contributes actively to the champion ing of artistic expression on campus. is e ort does not go unsupported, with an audience of 425 people from LSE and beyond lling the seats of the fashion show’s twopart runway on the ground oor of the Marshall building and the Student Union building’s Venue.

e interplay of textiles was also a highlight of the line up. Speci cally, the white tux and skirt designed by Ziyao Zang stood out for its intricate oral stitching. e simple white suit paired with a matching white skirt, designed by Ziyao Zang, takes on a captivating essence through its contrasting matte ower embroi dery on the shiny fabric of the blazer. e vibrant oranges and reds draw attention down to the matching lace sock on his right foot, while the mismatched socks and white ‘wine’ high heels add an unexpected twist to the otherwise simple tux set.

e Fall begins boldly, introducing the rst el ments of struggle. It completely shi ed the tone ‘shattered’ the dream through a palette of red black accompanied by sharp angles. It subverts what was initially o ered to us from e Dream and brought a new wave of energy and intrigue drowned in darkness. e lineup triggered emotions of despondency and bitter retort, which was tactically enhanced through the punctuated beat of the music and the sudden increase in the models’ pace.

As Social Editors the show was an event we were looking forward to and it certainly was a treat. Here’s our debrief; what we think, and which looks stood out most.