A New Generation Growing More than Crops

Executive Editor

Edna Rodriguez

Managing Editor

Beth Andrachick Hauptle

Associate Editor

Kara Hoving

Editorial Team

Kelli Dale

Lisa Misch

Mo Murrie

Justine Post

Photographer Joe Pellegrino

Staff Contributors

Carolina Alzate Gouzy

Benny Bunting

Kavita Koppa

Jaimie McGirt

Lisa Misch

Joe Pellegrino

Graphic Designer

Despard Design

RAFI is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and as such, donations are tax-deductible to the full extent allowed by law. EIN #56-1704863. RAFI believes in transparency, ethical accounting, and donor stewardship. RAFI has earned the 2024 Platinum GuideStar Exchange Seal and the sixth consecutive 4-star rating from Charity Navigator.

© Rural Advancement Foundation International - USA (RAFI)

Email: livingroots@rafiusa.org

Web: rafiusa.org

Union Label

Dear Living Roots Readers,

As we close out another year, we extend our deepest gratitude for the dedication, resilience, and hard work you bring to your farms, families, and communities. This past season presented some big challenges, and we especially hope that those a ected by Hurricanes Debby, Ernesto, Helene, and Milton are nding recovery and strength. Our thoughts remain with you, your loved ones, and the land you tend and steward.

In this issue, we are proud to share stories of hope and innovation. We feature ve young farmers who demonstrate that farming is more than growing crops — it’s about building vibrant, connected communities. We’re also proud to announce a new tool RAFI helped design to analyze the relationship between grocery store concentration and food access issues. Lastly, we’ve included essential guidance on what to watch for to protect your farm business when entering into contracts.

To our valued readers — farmers, colleagues, and champions of sustainable agriculture — your unwavering commitment inspires and sustains us. As we look toward 2025, we wish you a joyful holiday season and hope the coming year brings you health, happiness, and new opportunities to grow and thrive. RAFI stands with you, as always, ready to support and uplift our shared vision for a more equitable and resilient agricultural future.

With appreciation and warmest wishes,

Edna Rodriguez Executive Director

P.S. If you value RAFI’s work, please consider donating to help us support farmers and rural communities in the coming year. Make your impact at www.ra usa.org/donate/give/

RAFI’S BIENNIAL Come to the Table Conference was held this fall in Rocky Mount, NC. This year’s conference theme was “Food, Land, & Sacred Stories.” More than 400 people participated in person or virtually, engaging in thought-provoking discussions on the narratives that shape our understanding of food justice and the power of story to advance collective, creative solutions. See page 6 for a full recap of the event.

See QR code on page 5 for more information

Mariel Gardner shares her story “My Granny is a Genius” on stage at the Taste and Hear portion of the Come to the Table 2024 Conference at

IN JULY, RAFI announced the recipients of the 2024 Beginning Farmers Stipend. Awardees received between $3,000 and $5,000 to help reduce nancial barriers and cover farming start-up or production costs. These stipends support Historically Underserved Farmers and Ranchers as de ned by USDA NRCS.

This year, $75,000 went to 16 awardees across nine states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. The awardees represent diverse production models: 50% raise livestock, 75% grow vegetables, and 50% grow herbs. Funded projects include a range of activities for enhancing productivity and sustainability on the farm, from fencing and irrigation improvements to equipment purchases and high tunnel construction. Funding priority was given to farmers with barriers to accessing credit, loans, or capital and whose proposals demonstrated a solid commitment to farming, project planning and feasibility, economic impact, nancial need, agroecological practices, and community impact.

This project is supported by a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, a key funder of the Farmers of Color Network since 2020.

See the QR code on page 5 to learn more about the awardees and their funded projects.

Celia Borjas, one of the 2024 RAFI Beginning Farmer Stipend awardees, with her family.

JANUARY 6-7

Lexington, Kentucky 2025 Kentucky Fruit and Vegetable Conference

JANUARY 10-12

Roanoke, VA

Virginia Biological Farming Conference

FEBRUARY 4-6

Atlanta, GA

SOWTH Conference

MARCH 7-9

Utuado, Puerto Rico Latin America Organic and Agroecology Assembly

Since its founding, RAFI’s Farm Advocacy program has supported farmers facing financial crises. The role of a Farmer Advocate is uniquely challenging, requiring a blend of skills to navigate complex farm finances, USDA regulations, and the high emotional stakes of working with farmers under extreme stress. Many of today’s expert Farmer Advocates began their work by advocating for themselves or their neighbors during the 1980s Farm Crisis. Looking to the future, RAFI recently secured funding to train a new generation of Farmer Advocates. Funded by the USDA Farm Service Agency, RAFI is one of several

partners, including Farm Aid, collaborating as part of the Distressed Borrowers Assistance Network (DBAN). The project team will develop a comprehensive training curriculum, pilot a Southeast Cohort of Farmer Advocates, and establish a national network of Farmer Advocate practitioners to increase collective capacity to support farmers in financial distress. Look out for more information about this project in 2025.

Mark your calendars! RAFI will offer two grant programs to farmers in 2025: one for beginning farmers and another for farm infrastructure. Applications will open in spring 2025.

The Beginning Farmer Stipend is open to farmers actively operating for three years or less and will fund start-up costs. The Infrastructure Grant is for farmers who have been actively operating for at least four years and will fund infrastructure associated with the farm. Both require eligibility as a Historically Underserved Farmer or Rancher according to USDA’s NRCS definition.

To be notified when these programs begin accepting applications, sign up for RAFI’s monthly farmer newsletter at rafiusa.org/e-news-list/.

The Transition to Organic Partnership Program (TOPP) is a USDA-funded national project investing up to $100 million over five years in cooperative agreements with nonprofit organizations, including RAFI. The program supports farmers transitioning to organic with mentorship, workshops, field days, technical assistance, and educational events. Currently, 36 mentors and 61 mentees are active in the Southeast region of the U.S., with 1,194 acres in transition to organic production. Mentees receive guidance from a qualified organiccertified farmer mentor, a $500 stipend to attend eligible educational events, and support completing the organic systems plan. Mentors receive up to a $3,000 stipend each year for providing support to other farmers and professional development opportunities. See QR code above to learn more.

USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) can provide substantial conservation support for farm and non-industrial forest land. For those eligible, NRCS financial assistance programs, like EQIP and CSP, can provide financial assistance to address environmental challenges or enhance existing conservation efforts.

These practices can be applied to cropland (including orchards), pasture/grazing land, hay fields, rangeland, field edges or buffer areas, woodlands/ forests, small water bodies on farms, energy-inefficient buildings, and other farm-adjacent land. NRCS defines qualifying practices and enhancements as specific activities with an intended, positive outcome on the farm and the surrounding natural environment. Currently, substantially more funding is available for conservation practices/enhancements that are climate-smart.

Some Southeast states’ application deadlines have passed, but others are upcoming. Now is a great time to weigh your options and consider applying to make those long-awaited improvements to your farm. Improvements may include introducing grazing management and supporting infrastructure, improving pastures and forage, covering and stabilizing soil, reducing water loss, increasing soil fertility, planting tree crops, increasing wildlife and pollinator habitat, and improving water and air quality.

RAFI staff and partnering technical assistance (TA) providers located across the Southeast U.S. and the U.S. Caribbean can offer one-on-one, no-cost technical assistance to help you better understand NRCS options and your eligibility, prepare for an NRCS agent farm visit, feel confident with your application, and develop

SCAN to learn more about the Come to the Table conference, RAFI’s Beginning Farmer Stipend recipients, upcoming events and funding opportunities, and more.

a backup plan if you are not selected for funding. Depending on location, your TA provider may offer in-person or remote/ over-the-phone assistance.

See QR code above for more information on applying to NRCS.

RAFI’s Just Foods program partnered with the North Carolina Botanical Garden to harvest wildflower seeds from grow-out plots at two North Carolina farms this September. The harvest was the latest step in developing a new seed mix of pollinator-friendly wildflowers ideally suited to North Carolina’s unique environment. Just Foods program director Kelli Dale and NC Botanical Garden Conservation Grower Ali Touloupas gathered seeds from North Carolina ecotypes of wild bergamot, Eastern beard-

tongue, and mountain mint. When collecting wildflower seeds, it is important to keep them as dry as possible. Dale and Touloupas recommend waiting to harvest until the dew has dried off and storing them in paper bags instead of plastic to prevent molding. After harvesting, seeds must be thoroughly dried and separated from other organic matter. Eventually, Dale hopes to work with more farmers around the state to grow additional wildflower species and harvest seeds for restoration projects or pollinator-friendly commercial seed mixes. Farmers interested in the project should stay tuned for announcements from RAFI’s Just Foods program.

See QR code above to download RAFI’s North Carolina Pollinator Tool Kit.

(L-R) A-dae Romero-Briones, Fred DuBray, and Elsie DuBray speak at the “Food, Land & Sacred Stories” Come to the Table Conference in Rocky Mount, NC. Top: Richard Hewlin of 4-Ever Vista Farms with attendees at the farmers market portion of the Come to the Table 2024 Conference.

RAFI’s 2024 Come to the Table Conference

“WHEN YOU STAND on the land, we are all equal.” - Rev. Richard Joyner

On September 30 and October 1, 2024, RAFI held its biennial Come to the Table Conference at The Impact Center in Rocky Mount, NC. Speakers and participants shared diverse experiences with food, land, and history, re ecting on the theme “Food, Land & Sacred Stories.”

The conference opened with a keynote by Dr. Gail Myers, who highlighted the resilience of Black farmers. Afterward, RAFI’s Jarred White facilitated a panel featuring Dr. Myers, Rev. Richard Joyner (Founder, Conetoe Family Life Center), Joe Thompson (Thompson’s Prawn Farm), and Gabrielle Buchannan (Inter-Faith Food Shuttle).

Over 30 workshops o ered valuable insights and perspectives, from “Shaping Stories that Challenge Corporate Power” to “Food Charity, Food Justice, Food Rights & Food Sovereignty.”

On Monday evening, conference attendees gathered over dinner to hear six storytellers share about food, land, and the sacred, guided by Mark Yaconelli of The Hearth. The evening gathering emphasized the power of personal stories to connect storytellers and listeners to the land and those who have come before them.

On the second morning, RAFI welcomed A-dae Romero-Briones and Fred and Elsie DuBray to the stage for a meaningful conversation about the stories we hold onto, our oldest teachers, and what the bu alo

can teach us about our humanity and connection to the land. Elsie DuBray, a Stanford University graduate, shared that her formal education could not hold a candle to the lessons she’s learned from the bu alo and her home in South Dakota. “My greatest and oldest teachers are that of my homeland,” she explained. Her father, Fred DuBray, a key gure in the modern bu alo restoration movement and lifelong bu alo rancher, left the audience with a poignant reminder: “The stories are what keep it going; all sorts of things get lost, but our stories stay the same.”

See QR code on page 5 for more conference photos.

Highlighting Solidarity and Resilience

ON OCTOBER 1, 2024, farmers, advocates, and allies from across the region gathered in Rocky Mount, NC, for a dynamic Farmers of Color Network (FOCN) gathering. This event was an inspiring day of shared learning, deep connection, and celebration, highlighting the vital role farmers of color play in shaping agriculture and food systems across the U.S.

The atmosphere was warm and engaging throughout the day as participants exchanged stories, experiences, and insights. Linette Hewlin of 4-Ever Vista Farms and FOCN Coordinator Bianca Anthony led a heartfelt session on the joys and challenges of farming as a family, drawing on their own experiences. Tou Lee of Lee’s One Fortune Farm shared what it’s like to grow niche Asian vegetables, explaining how culturally relevant crops can help farmers reach new markets and strengthen ties with their communities.

RAFI’s Carolina Alzate Gouzy, Ph.D., hosted a screening of the 2022 lm “Serán las dueñas de la Tierra” (Stewards of the Land), sparking a meaningful discussion about land access in Puerto Rico. FOCN Communications Coordinator Hope Ostane-Baucom led an engaging hands-on workshop on using social media to tell farmers’ stories, connect with customers, and promote their work.

Urban farmer and educator Duron Chavis of Happily Natural Day delivered a spirited keynote underscoring the power that comes from

bridging urban and rural farming communities. He spoke of how these connections can inspire community resilience, liberation, and cultural preservation, leaving everyone with a sense of purpose and unity.

“It’s always gratifying when we can gather in person with Network members. Since 2017, the Network has grown signi cantly, and these events allow us to share ideas, address challenges, and explore farming innovations for a brighter future,” said RAFI Executive Director Edna Rodriguez. The gathering was not just an event but a celebration of growth, solidarity, and the enduring spirit of farmers of color, united in their dedication to the land and to each other.

BY KARA HOVING

Regenerative. Agroecological. Climate-Smart. Sustainable. Organic.

The world of agriculture is bursting with alternatives to the modern industrial model. As farmers and consumers recognize the negative environmental and community impacts of large, resource-intensive monocultures, there is a growing shift towards models that aim to restore soil health, conserve ecosystems, and reestablish balance with nature. But what do these terms really mean, where do they come from, and how do they truly di er?

On the surface, these agricultural movements can appear very similar. Most adhere to soil health principles like building organic matter and maximizing biodiversity. They promote practices like cover cropping, reduced tillage, intercropping, compost application, and rotational grazing — techniques often rooted in Indigenous land management predating colonization. However, they di er in their unique histories and nuanced beliefs, attitudes, and goals for building a better food system.

“Each of these terms has a history with a particular group of people that saw a particular challenge and then imagined a

speci c alternative that would help to overcome that challenge,” says Liz Carlisle, an Associate Professor of Environmental Studies at UC Santa Barbara who specializes in regenerative farming and agroecology. “The language is a really good indicator of the larger values that are driving the practices.”

The rst to emerge was the organic agriculture movement, which arose in the 1960s and ‘70s in response to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring exposé on the hazards of industrial chemicals and pesticides. The movement aimed to replace synthetic chemicals with biological fertility and pest control methods.

Thanks to the e orts of organic farmers and advocates, Congress passed the Organic Foods Production Act in 1990, authorizing USDA to develop the National Organic Program. To become certi ed and use the USDA Organic Seal, producers must adhere to a strict set of standards, including prohibitions on genetically engineered organisms and certain synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, and must undergo an accreditation process with a certifying agent.

Today, organic agriculture in the U.S. is a multi-billion dollar industry. In 2021, some 17,000 farms were certi ed

organic, accounting for 3.6 million acres of U.S. cropland and 1.3 million acres of pasture/rangeland. These farms vary in character from small, diversi ed farms to mechanized operations thousands of acres in size.

The organic de nition’s legal enforceability and clear focus on chemicals make it easy to understand. But it has limitations. A 2022 Cornell study found that while smaller organic farms tend to adopt practices that conserve resources and bene t the whole farm ecosystem, larger organic farms often operate much like conventional ones, with low crop diversity and a high degree of automation. Additionally, USDA Organic doesn’t fully address labor rights, animal welfare, or holistic environmental protection. Meanwhile, the organic certi cation process can present administrative hurdles that some small and beginning farmers consider too burdensome to be worth the e ort. Thus, the policy debate about what can and should qualify as organic remains ongoing.

Many producers seek frameworks that go “beyond organic” to advance a broader range of ecological and social values. These systems di er in their underlying values and the scope

Permaculture is an approach to land management and settlement design that adopts arrangements observed in flourishing natural ecosystems.

of their objectives, ultimately in uencing which practices are implemented and how outcomes are measured.

In 1987, the UN Commission on Environment and Development introduced the modern de nition of “sustainable development” as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Sustainable agriculture seeks to ful ll this principle while advancing a “triple bottom line” of economic pro tability, environmental quality, and social equity.

The U.S. adopted a legal de nition for sustainable agriculture as a system that satis es human food and ber needs, enhances environmental quality and natural resources, maintains economic viability, and improves quality of life for farmers and society. De nitions of sustainable agriculture practices abound, yet “true” sustainability varies widely with the local environment. In the 21st century, heightened concerns about global climate change have led to the evolution of new climate-oriented subsets of sustainable agriculture. Climate-smart agriculture aims to sustainably increase farm productivity, adapt or build resilience to climate change impacts, and reduce or remove greenhouse gas emissions where possible. Carbon farming focuses more narrowly on removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in soils or plant matter.

In recent years, the USDA has increased its support for climate-smart farming. Its $3.1 billion Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program launched in 2022 de nes a climate-smart commodity as “produced using farming, ranching, or forestry practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or sequester carbon.”

Enthusiasm for carbon farming has grown with carbon markets, which boost farmer incomes by compensating them to sequester carbon that o sets external emissions. However, both models have also been met with skepticism, including from Antonio Tovar, a senior policy analyst at the National Family Farm Coalition (NFFC). Tovar’s concerns about carbon farming include scienti c uncertainties surrounding soil carbon sequestration and measurement, the impermanence of carbon storage in soil and plant matter, and the fact that carbon o sets don’t translate into needed reductions in fossil fuel consumption.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, the regenerative agriculture framework emerged, with the central goal of restoring soil health through practices like reduced tillage, cover cropping, and grazing for natural fertilization and weed control. De ning “regenerative” remains one of agriculture’s most

Around the world, there are countless models and philosophies for ecologically and socially sustainable farming, though some have more scientific basis than others. Here are a few more to consider:

Agroforestry

Agroforestry describes practices that integrate trees with crop or livestock systems to boost ecosystem services and productivity. Practiced by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years, it is now promoted as a key component of sustainable and regenerative farming. Agroforestry practices like alley cropping, silvopasture, and windbreaks are eligible for NRCS support in many U.S. states.

Biodynamic farming

Biodynamic farming, an early influence on organic agriculture, focuses on ecological and spiritual harmony on the farm. Practiced in over 50 countries, it combines more common practices like composting, cover cropping, and crop diversity with mystical practices like planting and harvesting in rhythm with the lunar calendar and using “biodynamic sprays” made of herbs, crystals, and animal parts.

Holistic Management

Developed by Allan Savory in the 1960s, Holistic Management is a framework for managing land and livestock to regenerate grasslands and combat desertification by mimicking the movement of wild herds.

Permaculture

Permaculture, popularized by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, designs landscapes that mirror natural ecosystems. Its principles include growing perennial crops, creating closed-loop systems to recycle resources, and placing elements for multifunctional use.

hotly debated topics. A 2020 survey of over 250 sources found con icting, often contradictory, de nitions. This ambiguity allows corporations to use the term as a marketing ploy while in uencers make sweeping claims about its bene ts, creating confusion for consumers and producers alike.

According to Carlisle, the heart of the debate is a distinction between “deep” and “shallow” de nitions. Shallow regenerative, she says, acts as a checklist of practices, like cover cropping, that can be easily layered onto existing conventional models piecemeal without transforming the agroecosystem or human-land relationships. Deep regenerative, on the other hand, asks, “How can we x the problems that industrial agriculture has brought to land and community and not only rebuild soil health but rebuild the whole food system in a way that’s based on reciprocal relationships between people and land, plants, and animals?” This means including considerations like farmworker rights, land access, and animal welfare. It also means honoring the origins of

many regenerative practices in Indigenous and African traditions and seeking to rectify the ways that agricultural policies in the U.S. have dispossessed and disenfranchised Indigenous peoples, Black Americans, farmers of color, and migrant farmers — issues that white advocates within the regenerative movement have been slow to address.

Fortunately, there are many active e orts to ensure a deeper version of regenerative takes root, including the development of certi cations such as the Regenerative Organic Certi cation, the Real Organic certi cation, and Certi ed Regenerative by A Greener World (AGW). [Disclosure: RAFI is a partner on AGW’s Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities project, which includes technical and nancial support for farmers working towards AGW’s Certi ed Regenerative certi cation.]

Legal de nitions for regenerative agriculture are being developed, as they were for organic and sustainable agriculture. California has begun a public process to de ne regenerative agriculture for state funding programs, and advocates are closely watching the debate and its potential national impact.

These efforts have highlighted ongoing con icts between and within di erent agricultural movements. A critical debate is over agrochemicals. Some advocates worry that “regenerative” might be used as a greenwashing tactic for chemical-intensive practices, arguing that the nal de nition should adhere to organic standards to be truly chemical-free. Others believe that reduced tillage, central to regenerative practices, may require some agrochemical use. They advocate for allowing strategic, targeted chemical application in combination with ecological pest control.

Standardization also risks excluding traditional Indigenous agricultural practices, which are often community-based and deeply attuned to hyper-local environments and ecosystems. According to A-dae Romero-Briones, Director of Programs for the Native Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative at the First Nations Development Institute, “There are 574 di erent tribes in this country that have food production systems that predate American agriculture and regenerative agriculture. Some of them are growing corn, some are wildcrafting, some

to learn more

are ocean-based, and all of these have implications for this landmass that we call America now.” Narrow de nitions too focused on speci c approaches for soil health or carbon sequestration, she says, could close the door to more inclusive interpretations of ecologically adapted foodways.

Some advocates believe that terms like regenerative are ill-equipped to prevent attempts at corporate greenwashing and co-optation, nor can they address broader systemic challenges in the food system beyond the farm gate. Others prefer terms with social and political considerations naturally embedded in their de nitions. Agroecology describes both the science and practice of managing farms as ecosystems as well as a grassroots political movement for systemic transformation towards an equitable food system. According to Tovar of NFFC, agroecology goes hand in hand with food sovereignty, the concept that people have a right to healthy, sustainable, and culturally appropriate food and that those who produce, distribute, and consume food should drive agricultural decision-making, not corporations. These frameworks, championed by global movements like La Via Campesina, have a broad following in Latin America and Africa but have struggled to gain traction in the United States’ corporate-dominated agricultural policy sphere.

For Romero-Briones, none of these broad frameworks can truly capture the speci city of locally adapted Indigenous food systems. “When I think about these descriptors of agriculture, to me, it’s somebody interpreting what they’re witnessing and observing instead of somebody from a localized food system describing their own system,” she says. A better way, she suggests, might be to focus on naming and describing speci c practices and allowing communities to de ne their agricultural models on their own terms.

Sarah Hackney, Coalition Director at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC), describes the push and pull between frameworks as part of an eternal cycle. “As a term gains in uence, popularity, and attention, people are drawn to it because it seems compelling, and power moves to it. If a corporate entity thinks it’s going to give them market power, they’re going to try to use it. And then folks doing the really hard work of doing it right can, I think rightfully, feel that it’s being watered down.” Terms cycle in and out of favor as new groups seek to recapture previous movements’ transformative values and meanings.

“There is no one magic term that if we just picked the right word, it won’t be co-optable, and there won’t be that pressure,”

Hackney says. But fortunately, farmers can still nd ways to cut through the noise. For farmers seeking to move beyond extractive paradigms of production and bene t from the added market value of ecologically aligned practices, Hackney recommends starting by examining their values and the values of their community and customer base. From there, they can identify practices that align with those values and see if they correspond to a speci c certi cation that can help build trust in the marketplace.

For Romero-Briones, these alternative models are ultimately “imperfect descriptors of something better than what exists in the mainstream.” The true goal is achieving a healthy relationship between people and the land. “I think English words often fail to describe the power of that relationship. I’ve talked to farmers who love their land and who may not be able to describe it but feel it. And to me, that’s the heart of everything we’re trying to describe.”

KARA HOVING is a writer and policy advocate specializing in sustainable food systems and climate change communication. She helps nonprofits tell solutions-based stories that build momentum for positive change.

BY MELANIE CANALES

It used to be a saying that a town needed a bank, a post o ce, and a grocery store to survive. And if you didn’t have any one of those things, the town would die,” stated Brian Horak, manager of Post-60 Market, when sharing how his cooperatively owned grocery store came to be.

Post-60 Market’s story starts in 2018, after the small town of Emerson, Nebraska, lost its only grocery store, leaving residents without a convenient source of fresh food. Staring down the potential decline of their community, residents rallied together to raise funds to convert a former American Legion building into a cooperatively owned grocery store. It now serves three rural counties as the only grocery store in a 25-mile radius. The saga of Emerson’s struggle to improve food access is just one of many playing out in towns across the country, re ecting a broader trend in the grocery industry where corporations continue to consolidate and attain

outsized portions of market share, squeezing out competition and posing a massive threat to food access in vulnerable areas.

Over the past two decades, corporations have steadily consolidated the grocery industry, resulting in a highly concentrated market. In 2000, four parent companies controlled 42.5% of the total market share, while over half of the money spent in the grocery industry was divided among smaller, more regional food retail operations. By 2023, that concentration had risen sharply, with 67% of the market held by just four top parent companies. Of particular interest is Walmart’s market share, which grew 1035% between 2000 and 2023 and has dominated the grocery industry with the highest single-company market share.

The more concentrated a market, the higher the barriers to entry, and the harder it is to compete. The harm this poses to competition has tangible consequences. Workers su er deteriorated working conditions due to the lack of accountability and alternative employment options. Corporations prioritizing their bottom line above all else leave consumers subject to price gouging, divestment of grocery options in their neighborhoods, and poor food access.

Farmers who face challenges breaking into such a restricted market are robbed of opportunities to feed their communities and generate income for their operations.

Despite this rampant concentration, antitrust enforcement in the grocery industry over the last twenty years has been negligible. Laws like the Robinson-Patman Act, which is supposed to prevent price discrimination, go underutilized; the FTC has not brought a case under this law since 2000. Revitalizing these antitrust laws is crucial to mitigating grocery’s ongoing market concentration. Without a reliable analysis of market consolidation’s pervasiveness and consequences across the country, corporations can continue evading accountability and further concentrate the grocery industry.

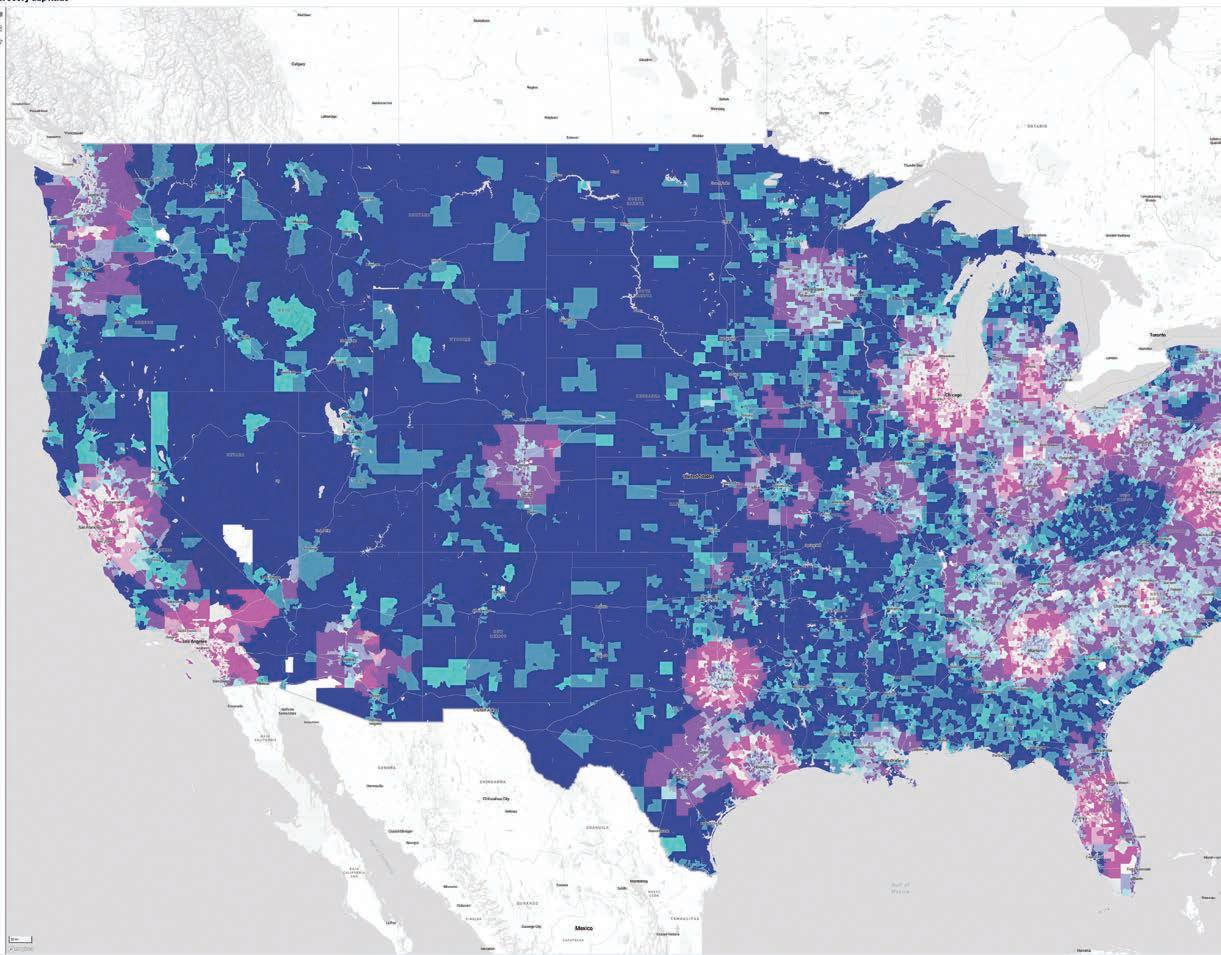

Enter The Grocery Gap Atlas. In partnership with the Open Spatial Lab at the University of Chicago’s Data Science Institute, RAFI developed the Grocery Gap Atlas to better illuminate the structural factors that contribute to food insecurity across the U.S., experienced at disproportionately high rates in rural and non-white communities. This geospatial analysis tool is designed to visualize corporate concentration in

Opposite: Downtown Tarboro, NC in 2024. Left: A decaying sign advertising Chicod Food Mart across from a recently built Dollar General in the outskirts of Greenville, NC.

Over seven states and nearly half the landmass of the country struggle under food apartheid conditions as corporations further consolidate their market share.

A town spanning three counties with large Native American, Hispanic, and farmland communities, where the closest grocery store can be over an hour away.

This 200-mile stretch between two rivers has a high African-American population. Walmart dominates five of the seven states in this region.

Predominantly rural areas in Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia experience disproportionately high levels of consolidation and food insecurity.

SCAN to explore the full Grocery Gap Atlas and learn more about corporate consolidation in the grocery industry.

the grocery industry, how it a ects food access, and which consumers are most impacted.

The Grocery Gap Atlas measures the concentration of retail grocery markets at national, state, county, and census tract levels — the closer a market is to a monopoly, the higher the market’s concentration and the lower its competition. Additionally, the Atlas measures how adequately grocers provide food access, which is determined by analyzing travel distances to grocery stores and comparing the food demand of a given geography to the supply available, as re ected by grocery sales data. Market concentration and food access quality are then mapped alongside each other to show how the two are correlated. Areas in dark blue are both highly concentrated and have limited food access, according to data from 2020. The Grocery Gap Atlas found that poor food access is somewhat more likely in areas with high market concentration and that this is most pervasive in rural areas, particularly impacting the rural West, the Mississippi Delta, and Appalachia. When corporations dominate an area, these geographies are susceptible to underinvestment in their food access needs. When food access declines, so does the health of entire communities. Workers lose jobs at stores that are closed. Competitors are prevented from lling the gaps in food access. Mid-scale farmers who live in these predominantly rural areas are cut o from various market opportunities and are forced to accept unfair contracts that do not fully account for the cost of their labor and operations — contracts that are entirely inaccessible to small-scale farmers. The Grocery Gap Atlas seeks to produce substantial data analysis that can more reliably inform policy decisions

addressing concentration in the grocery industry, educate the public about how concentration impacts food access in their communities, and identify potential solutions.

“What’s for supper tonight?” Horak endeavors to answer this question as he considers creative solutions to meet the needs of Emerson residents. A pragmatist, he recognizes how thin his margins are when competing with the buying power of monoliths like Hy-Vee and Walmart. Though he sources 99% of the store’s products from Associated Wholesale Grocers (AWG), he struggles to get distributors to stock a small store in such an isolated area.

Even with state-level initiatives meant to help establish new grocery businesses, expansions of investor bases, and countless grant applications, the nancial limitations of smaller grocery stores competing in a land of corporate giants pose enormous challenges to the resurgence of rural grocery. Corporations exploit their outsized market power by extracting discounts from grocery suppliers, and small grocery stores pay the price for this parasitic relationship. Small groceries often end up paying even more for their stock as suppliers try to recoup the di erence. In order to thrive longterm, food retail operations like Post-60 require federal-level policy designed to curtail market concentration, expand grant quali cations to include more creative grocery solutions, and incentivize a more regionally robust food system that doesn’t rely on corporate whims. While some solutions, like the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, have been proposed and implemented, small-scale food retail will need comprehensive support to remain viable long-term.

In the meantime, Horak keeps dreaming bigger. He envisions a Post-60 that has the capacity one day to serve surrounding towns that also lost grocery stores and struggle under conditions that make food access so abysmal. To Horak, Post-60’s highly local and collaborative structure gives him an edge over corporations that are only concerned with their bottom line.

“You always want to make money. But our motivation is to be a service to the community,” he shares. “So, as long as we pay our bills and put a little money in the bank, we’re okay. The rest is just to help the town succeed.”

MELANIE CANALES is the Challenging Corporate Power Project Manager at RAFI. Her years of experience in narrative development and working on farms have yielded a fierce commitment to cultivating a just and equitable food system. Her focuses include antitrust legislation, just agricultural transition, and resilient regional markets and food systems.

BY BETH HAUPTLE, KARA HOVING, ZACHA MUÑIZ, AND HOPE OSTANE-BAUCOM

Kamal Bell, Taij and Victoria Cotten, Kara Dodson, Juan Quinonez Zepeda, and Camil Valentin are ve farmers under 35 who, along with their families, are rede ning what it means to farm. Each has faced diverse challenges, like obtaining land, navigating systemic barriers, and building sustainable operations. Yet all are driven by a desire to pay it forward and foster something lasting.

These farmers aren’t just growing food — they’re building community and investing in the future of agriculture. Mentorship plays a crucial role in their work, whether it’s soaking up knowledge passed down from experienced farmers or helping the next generation nd its footing. From climate-smart practices and agroforestry to empowering farmworkers and young people, these stories demonstrate how farming is more than just a livelihood — it’s a way to connect people, restore balance with the land, and build a future that is both sustainable and equitable for those who come after.

Sankofa Farms - Efland, NC

Kamal Bell founded Sankofa Farms in response to systemic issues he was seeing, such as food deserts, di culty accessing land, and the lack of fresh, healthy food options for Black communities. He seeks to empower his community through land-based solutions that promote food sovereignty and economic self-su ciency. At Sankofa Farms, Bell has successfully established a diversi ed farm focusing on sustainable practices and growing accessible, nutrient-rich food for underserved areas.

“When I saw all these issues in our communities and so many other disparities, I thought they were all connected back to the land. I believed that farming could help solve it,” Bell says. Determined to be part of the solution, he pursued a bachelor’s degree in animal science and a master’s in agricultural education from NC A&T to gain knowledge and experience and to prepare himself for a future in agriculture.

After graduation, he spent four years teaching earth and environmental sciences to middle schoolers, engaged young men in an agricultural academy at his farm, and worked toward a Ph.D., but his ultimate goal was to farm. When he found 12 acres just north of Durham, he applied for a loan through the USDA Farm Service Agency. Although he was initially denied, he appealed the decision and, with the help of his mentor Howard Allen, successfully secured the funding he needed to purchase the land and cover initial operating expenses. Re ecting on land access challenges, Bell notes, “I think there would be many more stories like Sankofa’s if

we didn’t have to face all the barriers to accessing land.” He proudly shares that he’s been a full-time farmer for two years. Bell’s most signi cant challenges were building capital and learning to farm in a sustainable, diversi ed system. “I’ve had to learn that system through trial and error and mentorship. Howard Allen is one of my former mentors, and he’s helped abundantly with getting me informed, answering questions, and being a resource,” Bell says. Allen is known in the Triangle area of North Carolina as a “farmer’s farmer” and one who is always willing to share his knowledge and wisdom. (See Living Roots Issue 1, “Tunnel Vision: A High Tunnel Raising.”)

Mentorship like Allen’s is critical for young farmers. Talking to experienced farmers who have already navigated start-up challenges is invaluable, says Bell. “We need things like ‘Where do you get your irrigation equipment?’ ‘Do you need to work with a company that grows and ships transplants to you?’ There are so many things that we just don’t know early on. We need more resources and support around how to actually grow food. And how to hold on to our land.” Bell also encourages young farmers to get involved with local agricultural institutions and establish relationships with their local USDA o ce sta early on. Building these connections ahead of time can make it much easier to navigate USDA programs and resources when needed.

Kamal Bell is more than just a farmer — he’s a community-builder, an advocate, and a catalyst for change. Through Sankofa Farms, he’s transforming land into opportunity and turning food into a powerful tool for empowerment. His work shows that farming isn’t just about what you grow; it’s about who you lift up along the way. BH

CottenPicked Farm - Pittsboro, NC

If you come across a vibrant hideaway, alive with brilliant colors, nestled in the heart of downtown Pittsboro, chances are it’s the creation of Taij and Victoria Cotten. With their bright smiles, over owing energy, and a fresh perspective on sustainable agriculture, their path into farming is as lively and surprising as the lisianthus ourishing in their elds.

The Cotten’s love story and farming journey took a serendipitous turn in 2017 when they responded to a Craigslist ad to work for one week helping with the Mother’s Day rush at Preston Flowers in Cary, NC. They fell in love with owers. This moment prompted them to leave their jobs and travel across the Piedmont region, learning from various farmers. They enrolled at Central Carolina Community College to enhance their technical expertise, focusing on sustainable agriculture. Their approach was to divide and conquer. Sharing one car and a ip phone, they plunged into farming wholeheartedly, acquiring experience in numerous agricultural areas, from sheep shearing to row crops to blueberry orchards.

They launched their farming business in October 2023, cultivating one acre of land they a ectionately call their “farmdom.” They lease the land with a cousin, a fellow young Black farmer specializing in cattle. They also grow perennial crops at Victoria’s mother’s house, which they aspire to transform

into their permanent farm. Much of the family-owned land is forested and not readily available for agricultural use, but they are exploring ways to overcome this obstacle. Creativity and passion seem to unfold solutions to the many trials of farming.

The Cottens acknowledge the challenges and stigma associated with farming as a Black family. Some naysayers still associate Black farmers with historical connotations of slavery and sharecropping, but the Cottens celebrate farming as an act of liberation and independence. They wanted to escape the constraints of a traditional 40-hour work week to be with their children and follow their passion for working the land. For them, farming o ers freedom, self-reliance, and a lifestyle that is meaningful and ful lling.

One word captures the Cotten’s farming philosophy: intentionality. To them, farming is more than planting seeds; it’s about sowing purpose, both in the soil and in the relationships they nurture along their journey. They have learned to embrace their unique experiences, understanding that their struggles and successes di er from those of others in the eld and that no universal solution will t each farm’s distinct trajectory. Their counsel to fellow farmers is to focus on their own journey while keeping an awareness of the broader landscape, to cultivate with intention, and to maintain resilience. Ultimately, no matter how challenging the journey may become, farming — when approached with intention — fosters growth, not only in the elds but in life itself. HOB

Until 2015, Kara Dodson worked as a eld organizer for an environmental organization, promoting energy e ciency and campaigning against coal ash pollution and mountaintop removal in Appalachia. Exhausted by the burnout culture of high-stakes nonpro t work and her desire to work both body and mind, Dodson left her job at age 25 to work on an organic farm in the North Carolina High Country. In 2016, she and her partner, Jacob Crigler, bought land in Deep Gap, NC, and launched Full Moon Farm.

Dodson and Crigler grow produce on their 30-acre farm using organic, sustainable, and no-till practices. Initially, they marketed through multiple channels in a sort of “buckshot approach,” selling through a CSA, a farmstand, direct sales to restaurants, and a weekday farmers market. Nowadays, they mainly sell through the High Country Food Hub, a year-round online farmers market, as well as selling to the Hunger and Health Coalition food pantry.

Dodson’s nearly decade-long farming journey has brought many lessons along the way. “There’s several learning curves around working with a partner, whether a spouse or a business partner,” she says. She also mentions the learning curve around timing capital investments on the farm. “I would say go slow, especially with investing. I see a lot of people buy

expensive equipment or expensive property or want to do things 100% organic, regenerative, highly managed right away, and you don’t get to learn about your working skills or the land you’re working on.” She recommends going through several experimental phases to understand what crops and approaches work best on your land, even if some e orts fail. “I think farming teaches you to fail over and over again, and you start to see failure not as a bad thing,” Dodson shares.

Dodson and Crigler had help from their family when they rst purchased their land. Since then, property values in their area have skyrocketed. “Acquiring land is still too hard for people who don’t have generational wealth, and that’s just the reality,” Dodson says. The couple is positioning Full Moon Farm to support the next generation of small farmers. They are transitioning the farm to nonpro t status and plan to grow food for bulk sales to food access groups and distribution programs. Over time, they will transition ownership of the land beyond their 4-acre homestead to the nonpro t, which will hire beginning farmers to learn the ropes of managing the property and give growers an opportunity to farm on land they otherwise could not a ord to buy themselves.

Dodson is excited to pay it forward by mentoring young farmers just starting out. “Farming is something that needs to be taught, and it needs to be something that’s mentored. It’s not something that can be taught in a classroom or a college environment. And for people who want to get into farming

that respects the environment and climate and resource use, they need to learn that from other people who are doing it in real-time.” She, Crigler, and their new nonpro t board also hope to build public spaces on the property for activities like group counseling so that Full Moon Farm can be a place for growing, education, and healing. KH

Note: The interview with Kara Dodson took place prior to Hurricane Helene. This article was published with her consent as Full Moon Farm undergoes recovery e orts.

Cebadilla Ranch - Senatobia, Mississippi

“Cebadilla means ‘barley’ in Spanish — the barley elds where my stepdad worked in Mexico with his stepdad when he was about 11 years old,” says Juan Quinonez Zepeda. “In those elds is where he met my mother and where they rst locked eyes. And I guess the rest is kind of history.”

Cebadilla Ranch is a 28-acre cattle operation in Senatobia, Mississippi, that Quinonez Zepeda owns and co-manages with his family. It was founded in early 2024 as a multi-cultural, -lingual, and -generational ranch with a mission to conserve traditional Mexican knowledge, build collective Latine immigrant power, and foster farm ownership opportunities for Latine farmworkers in the region.

Quinonez Zepeda grew up surrounded by agriculture. Born in California and raised in Mexico, Quinonez Zepeda’s love for agriculture was nurtured by his grandmother, who now operates an all-women co ee cooperative in Casimiro Castillo, Jalisco, Mexico. He started working in the northern Mississippi cattle industry with his stepdad at 14, laboring long hours during summers and school breaks. “It wasn’t something that brought me any joy back then. I think I very quickly realized ... the power dynamics between white owners and Latine workers that my dad was subject to, and that I then also became subject to — the levels of labor exploitation and wage theft and lack of proper recognition for the work that people are doing. Then, I went to college in New Hampshire, and my rst job there, making $10 an hour, was more than my dad was making at that time. And I told myself I’m never going back; that is not what I want to do.”

Yet, while in college, Quinonez Zepeda began connecting to his family’s experiences through a social justice lens. In 2020, he co-founded FUERZA Farmworkers’ Fund, a mutual aid organization to support dairy farmworkers in the Northeast, while focusing his senior honors thesis on migrants in northern Misssissippi’s beef cattle industry. Increasingly, he felt called to return to Mississippi and the cattle industry on his terms.

In 2024, he and his family purchased the land for Cebadilla from a family contact. The previous landowner, with

over 50 years of experience in the cattle industry, continues to guide the family as they set up their business. Quinonez Zepeda says that support has been a blessing. Still, it’s one that other Latine families do not have access to in a region that lacks multicultural and multilingual support for aspiring farmers. He sees a growing shift in the industry where folks who have worked as farmworkers for decades are seeking to become farm owners and establish a permanent legacy for their children. However, they need Spanish-language support to navigate legal and nancial processes for obtaining land.

Quinonez Zepeda hopes to position Cebadilla Ranch as part of the solution. He envisions creating an incubator ranch o ering peer-to-peer educational opportunities online and on the ranch. He also wants Cebadilla to showcase Latine and immigrant agricultural workers’ essential knowledge and deep experiences, pushing back against harmful stereotypes that depict them as an unskilled labor force.

Quinonez Zepeda is hopeful that supporting the transition of farmworkers to farm owners will help advance broader transformations toward a more inclusive, sustainable, and just food system. “I think that’s the powerful thing about having people who previously worked [as farmworkers], who now are shifting to owners, that they don’t want to replicate those systems of harm that they experienced themselves, and want to take care of the land and the animals in a di erent

way than what they previously experienced,” he says. “As a younger generation, I think we’ll have the ability to rede ne what agriculture means for us, what we want to make it.” KH

Huerta Libre - San Sebastián, Puerto Rico

Camil Valentin’s journey into agriculture began in 2014 when a high school agricultural education course changed her life. “It transformed me,” she says. “I went from wanting to study law to dedicating myself to agriculture.” Valentin’s entrepreneurial spirit emerged early — she started selling cilantro to her teachers while still young.

When she began cultivating cilantro and eggplants, it became clear that farming would be her life’s passion. “Agriculture became this driving force. I understood that I wanted to work for social justice, but I wanted to do it through action,” she shared. She studied political science and sustainable agriculture at the University of Puerto Rico in Utuado.

She began farming at relatives’ homes, working with about a quarter of an acre. At that time, Valentin produced value-added products and participated in farmers markets. Challenges like urban encroachment and herbicide use from neighboring homes soon drove her to seek a farm of her own.

Two years ago, Valentin acquired a 5.6-cuerda (about 5.4acre) former sugarcane and co ee farm in the rural, isolated Mirabales neighborhood of San Sebastián. As she familiarized herself with the land, she discovered how degraded its soil was. Its soil has a pH of 4.8 (extremely acidic), an uneven topography, and signs of a landslide.

Valentin and her team began transforming the farm, called Huerta Libre, into an agroforestry system. Their long-term goal is for it to be a model farm, showcasing agroforestry practices and functioning as a forest school. Valentin envisions creating a space where young people can explore and engage with sustainable agriculture.

Currently, Huerta Libre focuses on grafted breadfruit as its star product, grown in symbiotic association with smaller fruits such as soursop, custard apples, oranges, grapefruit, and pineapples. However, the farm is in a transitional phase as Valentin works to build essential infrastructure, including a house/workshop, a nursery, shaded structures, and an improved drainage system.

Erosion is a major issue. “It’s an everyday battle, having a farm with irregular topography where it rains a lot. We haven’t been able to pave or lay down stones yet,” she says. An infrastructure grant from RAFI has allowed Valentin to work on xing some trenches, hopefully mitigating an impending

landslide. “It’s a constant challenge,” she says. The farm is also heavily shaded, preventing the growth of erosion-controlling crops like vetiver.

Another obstacle has been nding agroforestry models in Puerto Rico that align with her vision. Many nearby farms grow co ee or cocoa, which are commodities, but Valentin wants to grow food. A visit to Ecuador gave her hope: The agroforestry system she envisioned was possible and already being practiced there for the past 10, 15, or even 20 years!

“As tropical countries, we must bet on these more resilient systems,” she notes.

She re ects on helping her grandmother harvest in their garden and how it shaped her connection to agriculture. “We would plant pigeon peas, pick acerola cherries, climb trees to get grapefruits. I now realize how lucky I was to have lived such a close-to-nature childhood. It helped me develop a deep sensitivity to nature, the forest, and agriculture.”

Ultimately, Valentin sees Huerta Libre not just as a farm but as a place of learning, hope, and community — a place where sustainable practices can ourish and serve as a model for the island and beyond. ZM

BY BENNY BUNTING AND KARA HOVING

Managing contracts is an essential part of running a successful farming business. Contracts help farmers plan for the future and balance nancial risks. Sometimes, documents come across a farmer’s desk that don’t appear to be contracts but actually are. Seemingly small details in a contract can make a huge di erence in your farm’s nancial security and whether you are eligible for various grants and programs, including USDA funding.

Here is some advice on what to look for when considering a new contract:

Read the ne print: Carefully read and make sure you understand every clause of the contract. One way to gauge your understanding is by trying to explain each clause to a family member or friend. If there is a clause you don’t fully

understand, go back to the other party or seek legal assistance. If possible, always consult an attorney before signing a contract to ensure you fully understand the scope of the agreement.

Cradle to grave: Consider the full timeframe covered by the contract, which should be clearly de ned. Contracts can be binding for any period, from a single season to 100 years. For example, most NRCS contracts require proof that you have control over the farm property for the next ve years to be eligible for assistance. Can you commit to the timeframe required by the contract? Will the contract continue to be economically favorable for you over the long term? And if not, what are your options for terminating the contract?

It’s also important to understand how your responsibilities will change at di erent points during the entire life cycle of any new venture or project. If you’re leasing out some of your

land to an energy developer to host solar panels or a wind turbine, who will be responsible for that infrastructure at the end of its useful life? Work with the other party to ensure everyone’s responsibilities are clearly de ned at each stage.

Look out for liabilities: Reading through a contract to understand the bene ts to each party is easy — understanding liabilities can be slightly more complicated. Ideally, both the bene ts and the burden of liabilities should be more or less equally distributed — each side bene ts; each side also shares in the risk of loss.

But this is not always the case. Often, poultry and livestock contracts can be the opposite — the grower holds all of the nancial risk, while the integrator is essentially insulated from loss. For example, most hog farming contracts place the responsibility of creating and adhering to a waste management plan on the farmer, not the integrator. In the case of a spill, the farmer would be liable to be ned or even shut down by the state, or could be sued by downstream neighbors a ected by the breach. Understanding your liabilities and implied responsibilities — and their potential consequences — is absolutely crucial when entering into a contract. Overall, weigh the pros and cons and make sure you’re not absorbing additional risks that outweigh those you are trying to protect against by entering into the contract.

who becomes legally recognized as the “grower.”

Also, consider any rights you might be giving up when borrowing money. Look at any requirements included when signing a promissory note — a legally binding document outlining a loan’s terms and repayment agreement. Promissory notes often restrict what farmers can do with any equipment put up as security. If a farmer sells their equipment without authorization from the lender and does not replace it with substitute collateral or tries to sell secured equipment to get money to make a payment, this would count as a non-monetary default on the loan.

Understand the consequences of termination: Get a clear understanding of what will happen if you can’t ful ll the terms of an agreement. For example, many NRCS contracts include a monetary termination penalty to cover for lost sta time if a farmer decides not to go through with a project. Failure to implement a funded project can be forgiven if the failure is due to something outside of the farmer’s control, like a natural disaster, but it’s important to understand where the boundaries of responsibility lie.

Think outside the box: Consider possible third-order e ects of a contract, particularly how the contract will directly or indirectly impact your relationships with outside parties. For instance, contracts can a ect your eligibility for government programs. In a production contract where a company is supplying the farmer with labor, equipment, or transportation, this can complicate the question of who quali es as the “producer,” according to the Farm Service Agency (FSA). This will impact who is eligible for insurance or other USDA assistance.

Contracts can also in uence your overall marketing opportunities. For example, a hemp farmer might contract to deliver 25,000 pounds of product to a buyer but end up having a bumper crop and producing in excess of that amount. The contract only obligates the buyer to take the agreed-upon amount but might grant the buyer the right of rst refusal before the farmer can sell the excess to someone else. This could leave the farmer scrambling to sell the surplus.

What are you giving up? In reading through a contract, make note of every right you previously held that the contract would have you give up. This may take obvious or less obvious forms. For instance, does the contract exclusively grant the other party the right to public funds or grant money? This is the case in many carbon credit contracts, as more companies seek to capitalize on government programs incentivizing climate-smart practices. Farmers implementing climate-smart practices to sell carbon credits to a broker are often required to surrender any grants or public funding to the broker entity,

Likewise, it’s important to understand what your options are if the other party fails to uphold their end of the agreement. Farmer Advocates advise that it’s important to retain your right to go to court with a contracted party. In the past, many poultry and livestock contracts have forbidden growers from taking integrators to court, instead requiring them to go through an arbitration process that heavily favors the integrator. Understand your rights in these situations, and consult an attorney when in doubt.

A balanced deal: When it comes to negotiating a contract, you want to get a good deal — but you also want the other side to get a good deal. If something falls through that leaves the other party high and dry, chances are that is not going to be good for you either. Consider things like insurance and whether it should be required by the contract so that both parties are protected in the event of a loss. Ensuring a good deal for both sides will protect others’ willingness to work with you in the future.

Contracts are complicated — but they don’t have to be intimidating. Fortunately, resources are available to help. Organizations like Farmers Legal Action Group and Farm Commons produce high-quality print and online materials explaining legal issues surrounding di erent types of contracts encountered in farming. Regional organizations, like Legal Food Hub in the Northeast, match farmers with pro bono legal services to guide them through the process. Start by contacting a Farmer Advocate or checking the QR code on page 22 to learn more.

By Carolina Alzate Gouzy

Clara Inés Nicholls is a Colombian agronomist with a Master’s degree in Entomology from the Colegio de Postgraduados, Chapingo, Mexico, and a Ph.D. in Entomology and Biological Control of Insect Pests from the University of California, Davis. She is a professor of Sustainable Rural Development in Latin America at the University of California, Berkeley. She also teaches at Santa Clara University and other universities in Colombia, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Spain, and Italy. Her research focuses on managing vegetation biodiversity on farms to provide habitat to encourage natural control of insect pests in various agricultural systems. She is the author of four books (including Biodiversity and Pest Management in Agroecosystems) and more than 50 articles in scienti c journals.

Carolina Alzate Gouzy spoke with Professor Nicholls about agroecology and natural pest control.

Carolina Alzate Gouzy (CAG): Let’s start by understanding what makes an organism a pest.

Clara Nicholls (CN): An organism is considered a pest when its population reaches a level at which, if no action is taken, the economic cost from the loss in production due to the organism will be greater than the cost of control or treatment. Agroecological practices aim to keep phytophagous insects (insects that feed on plants) at low population levels, causing only minor damage that does not a ect economic output. In other words, agroecological practices can keep the insect from becoming a pest.

One question that immediately arises is: How can the density of an insect be reduced so that it is not considered a pest and does not cause economic damage? In conventional agriculture, the

response is to apply chemical pesticides, which do reduce the insect population, but at a high environmental cost. They also only work until the pest develops pesticide resistance. In agroecology, we ask the question, “What is the root of the problem that allowed the insect to become a pest?”

CAG: What are some reasons a phytophagous insect becomes a pest?

CN: Generally, pest problems arise in monocultures that provide a large supply of a single crop. Insects that feed on plants respond to olfactory and visual signals. If a eld has only corn, it will be very easy for a specialized phytophagous insect to nd that crop through sight and smell. But if we combine corn with beans, squash, or other crops, the smells and colors change, and that phytophagous insect cannot nd corn as easily.

In addition, diversi ed farms provide habitat for natural predators and parasites that attack the pests. But in a conventional monoculture, pesticide

application tends to eliminate these natural enemies. Another issue is that as long as you use a chemical, you constantly expose the insects to the same stimulus so the population can develop resistance. The same thing happens with genetic engineering and GMOs. In summary, farmers who rely on monocultures, pesticides, and GMO crops get trapped in a “pesticide treadmill,” forced to apply more and more pesticides as pests develop resistance and as natural enemies are eliminated.

CAG: How do you address these pests with an agroecological approach?

CN: From an agroecological perspective, the rst thing is to prevent phytophagous insects from becoming pests. So, how do we do that? If the root cause of the problem is the monoculture, we act by breaking up the monoculture with diversity. Diversi cation — through crop rotations, intercropping, or agroforestry systems — makes it more di cult for phytoph-

agous insects to nd the host plant and also attracts natural enemies that feed on the phytophagous insects and keep their population under control. The introduction of owers is key as natural enemies need pollen and nectar for fecundity and reproduction; other plants can serve as “trap crops,” luring pests away from the crop, while others may repel some phytophagous insects that do not like the plant’s smell.

CAG: For example, cilantro and tomato?

CN: Exactly. In that case, the smell of cilantro repels potential pests such as white ies from tomatoes.

CAG: What are other ways to attract natural enemies to control pests?

CN: It is important to understand what natural enemies need to thrive and remain in the eld. Many parasitoids of pest insects need pollen and nectar for longevity. Not just any ower will do; planting borders or strip rows of owers that o er exposed pollen, bloom for extended periods, and ower at the same time crops are planted can help ensure the presence of natural enemies during critical periods of the crop’s growth.

Natural enemies also need shelter and nesting sites. Some, like coccinellids (the family of beetles that includes ladybugs), are attracted to herbaceous plants, so leaving a herbaceous layer for them is essential. Ground-walking predators, like spiders, require soil cover in the form of cover crops or mulch. Others, like lacewings, need trees and larger bushes, which can be provided in the form of hedgerows. So, it is vital to know the ecology of natural enemies when designing diversi ed farms.

In ecology, we always say that the more diverse a natural ecosystem, the more stable it is. In an agroecosystem, you have a crop to protect, so you must work with auxiliary biodiversity that provides bene ts for farmers, including pest control.

CAG: How do you visualize and monitor biological pest control in the field to ensure you apply the right strategy?

CN: First, we look at what we have in the eld, what the pest is, and how, where, and when it a ects the crop. What does the pest feed on: leaves, roots, or fruit? Then, we must understand the pest’s life cycle and when it is most susceptible to predators or parasitoids. For some, when the insect is in the pupal stage, it is generally more di cult for a natural enemy to feed on it, but if a pest is in the egg or larval stage, parasitoids or predators can reach it more easily.

There are many methods to capture and identify the pests and other insects on your farm, including sweep nets, yellow sticky traps, yellow pans, pitfall traps, and direct observation of plants. When farmers observe the diversity and abundance of natural enemies in their elds, they can gain con dence about the potential for natural pest control methods to prevent or reduce their pest problems.

CAG: How can farmers learn more about the insects in their agroecosystem and start implementing biological pest control?

CN: Simple courses and eld guides can help farmers identify insects on their farms and understand how biological control works. They can also learn through eld visits and experimentation, knowledge exchange with other farmers, and access to clear information.

Training starts on the farm by observing what insects are present and if the farm’s environmental conditions are conducive to biological control. It is important to learn little by little. We work with farmers to collect insects, identifying which are bene cial, which are pests, and which, like decomposers, are neutral but could provide additional bene ts in the absence of chemical pesticides. Then we observe if the farm

provides habitat (refuge, nesting sites) and alternative food sources (such as owers) for bene cial insects.

So, if a farmer wants to make an agroecological transition, the rst step is eliminating chemical pesticides. But this process involves learning, trust, understanding, and gradually transitioning. The farm doesn’t have to be transformed all at once; farmers can change a small section at a time and observe the di erences compared to the rest of the farm.

The tomato hornworm, Manduca quinquemaculata (Haworth), is a common pest that feeds on plants in the Solanaceae (nightshade) family.

In these experiments, they can observe when natural enemies such as ladybugs and lacewings start coming from the system’s edge to eliminate the pest. Through observation and experimentation, farmers become increasingly con dent in agroecology’s ability to activate and sustain ecological processes on their farms.

CAROLINA ALZATE GOUZY joined RAFI in August 2022. She has worked on agroecological projects as a part of nongovernmental organizations that seek a more just and regenerative relationship between the rural and urban worlds. She is a biological engineer with a Master’s in Agribusiness and a Ph.D. in Sustainable Development from Universidade de Brasília, Brazil.

by Sara June Jo-Sæbo, The Daily Yonder

FEW BOOKS ABOUT America’s industrial agriculture system and food industry uncover the billionaires behind its biggest corporations. But a new exposé by Austin Frerick, a former tax economist at the U.S. Treasury Department and current fellow at Yale University’s Thurman Arnold Project, reveals the amassed fortunes of Big Ag’s most powerful families. Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry (Island Press) exposes these ill-gotten gains and a cadre of complicit government players who made it all possible. The USDA’s dismal Census of Agriculture (February 13, 2024) disclosed that 141,733 farms shuttered between 2017 and 2022. Barons reveals that these losses happened at the same time that big food producers and merchants garnered both stunning pro ts and government handouts.

Frerick is an expert in agriculture policy with an antitrust law focus. He served as a co-chair for the Biden

campaign’s Agriculture and Antitrust Policy Committee during the 2020 election. In Barons, Frerick steers his experience and scholarship into a pointed denunciation of Big Ag’s unbridled and monopolistic wealth. It’s an overdue censure. In fact, many times during the book, I was surprised by a recurring sense of personal validation. Being from rural Iowa and witnessing the 1980s Farm Crisis take hold of my family and neighbors, Barons takes a long overdue stand for the farm community of my youth. It’s a painful loss knowing that today’s industrial food system rises from the ashes of America’s family farms. And it is no accident.

For folks who haven’t kept up with our recent history in food production, Barons will be a wake-up call about the food in our grocery stores. Most Americans can agree that we want to see family farms with pastured livestock and tidy croplands dotting the countryside. We want to think that

It’s a painful loss knowing that today’s industrial food system rises from the ashes of America’s family farms. And it is no accident.

most of our groceries come from these untroubled places of our imagination. But Frerick shows us that this earlier model of farming has been absent or in a state of decline for a generation. The meteoric rise of industrial-scale farming in the last 50 years means that the food we buy today assuredly comes from warehouses packed with living animals under a whir of exhaust fans or from cropland doused with Roundup.

While Frerick o ers the details of this agricultural dystopia, his focus is elsewhere. He wants to expose the families and policymakers who’ve built this system. Resurrecting data about today’s con nement farms, labor violations, and environmental pollution, Frerick presses beyond the emotional draw of disgraceful industrial practices to take aim at the system’s big money. He unmasks the people who build fortunes by garnering monopolistic shares in agriculture and food distribution consolidation — obscene wealth, unearned.

Through seven carefully researched chapters (there are 58 pages of citations), Frerick shapes the story of the American food industry around a few families who make a killing from our government-backed industrial model. Each chapter uncovers an individual family’s origins in agribusiness and the ways they gamed policy and dereg-

ulation to their own advantage. Some of these family names will be familiar — like the Cargill-MacMillans of Cargill, Inc. and the Waltons of Walmart. But most of the families in Barons are hidden behind their brands. The hog producers, Je and Deb Hansen, built a Midwestern empire called Iowa Select Farms. Mike and Sue McCloskey own a massive con nement dairy operation called Fair Oaks Farms and invented a modi ed milk called “Fairlife.” The Batista brothers, Wesley and Joesley, own a global network of slaughterhouses under the brand JBS. Frerick uses these families’ stories to look at America’s history with farm practice and policy. “Each chapter,” he says, “is built around both a baron and a key concept. For example, the Grain Baron chapter is really about the Farm Bill. I used the story of the Grain Barons to tell the history of the Farm Bill

and how it has corrupted the food system.” Likewise, a chapter about the McCloskey dairy barons exposes agriculture’s checko system, in which individual farmers must pay a fee for each unit of product they bring to market. Frerick skillfully reveals how an otherwise mundane industry marketing program has been twisted to support lobbying on behalf of major corporations, not farmers. In a carefully researched book, Frerick makes ordinary insider knowledge both compelling and urgent.

At times, Frerick deftly switches his approach to include his family’s own connection to these food empires. Frerick’s mom owned a bakery, and his dad drove a truck and delivered beer in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He positions his family’s experience against this backdrop of what’s happening across rural America as the billionaires of Big

Ag gather ever-growing shares of their markets. From the emptying of rural communities to the pastures that used to contain small herds of cows, Frerick dispels the illusion that rural and small-town America is just a wholesome destination for weekend bike rides and microbrews. In truth, Rural America has been sacri ced for a brutal food industry and the personal fortunes of its barons. And Frerick doesn’t let us look away.

SARA JUNE JO-SAEBO founded the Midwest History Project and is the author of I Have Walked One Mile After Dark in a Hard Rain, a book that uncovered new facts about an 1848 settlement of Black Americans in Wisconsin. She lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia.

This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder. For more rural reporting and small-town stories, visit dailyyonder.com.

By Megan Collins

And if we can’t be the land, soft and dry beneath their feet,

let us be a bridge, let our bodies be the planks they step across,

let our linked arms be stronger than any cables could be.

And if we can’t be a bridge, let us be the air, let our breath

become theirs, let us fill them up so their lungs don’t hurt like hearts.

And if we can’t be the air, let us be the clouds, let our mouths

hold in the rain, let us swallow it down until the soil knows thirst again.

And if we can’t be the clouds, let us be the light, let our veins

become wires, let us blaze each bulb with our electric blood.

And if we can’t be the light— or clouds or air or bridge or land—