RAFIhasateamoftechnicalassistanceproviderswhocaninform,andprovidesupportonawiderange offarmoperationtopics.Inparticular,RAFIisdevotingmoreresourcestohelpfarmersadoptclimatesmartpractices.Wecanprovideassistancetoidentifyfarminfrastructureimprovementsthatsupport on-farmconservation,andatthesametimeimprovethefarm’sproductionandmarketaccess.Takea lookbelowforanoverviewoffarmerservicesavailableandstaffcontacts.

Wecanhelpyou…

UnderstandNRCSeligibility,programs,andpopularinitiatives.

IdentifyresourceconcernsandconservationpracticesthatcouldqualifyyourlandforNRCS assistance.

CompletethenecessaryformstoapplyforNRCS cost-shareassistance.

MakesuccessfulcontactwithyourlocalNRCS agentandotherfarmerswithsuccessfulprojects.

CONTACTJAIMIEMCGIRT:JAIMIE@RAFIUSA.ORG

Wecanhelpyou…

DetermineFSAloaneligibilityandloanoptionsthatwouldbethe bestfitforyouroperation.

ReviewfarmfinancialstocompleteFSAforms.

ByprovidingsupportthroughouttheFSAloanapplication process.

Byrecommendinghowyoucanreacheligibilityorpursueother lendingoptions(shouldyoubeineligibleforFSAloans).

CONTACTOTISWRIGHT: OTIS@RAFIUSA.ORG

RAFIwillsoonlaunchanew programthatwillsupport farmerswhowanttoalign theiroperationwith regenerativeandclimatesmartagriculturepractices. Detailswillbeavailablelater thisyear.

CONTACTJEREMYHART: JEREMY@RAFIUSA.ORG

SinecesitasatenciónenespañolcomunícateconCarolinaalemailcarolina@rafiusa.org

Executive Editor

Edna Rodriguez

Managing Editor

Beth Andrachick Hauptle

Editorial Team

Margaret Krome-Lukens

Lisa Misch

Joe Pellegrino

Justine Post

Mary Saunders Bulan

Contributors

David Allen

Carolina Alzate Gouzy

Jennifer Fahey

Aaron Johnson

Jaimie McGirt

Lisa Misch

Joe Pellegrino

Justine Post

Mary Saunders Bulan

Angel Woodrum

Proofreaders

Matthew Adkins Mo Murrie

Designer

Despard Design

Dear Friends,

We’ve had a busy summer here at RAFI and thoroughly enjoyed meeting so many of you at site visits, conferences, farmers markets, work days, and online during webinars.

Creating this magazine is a labor of love for RAFI sta . As you can see from the number of sta writers and contributors, we enjoy sharing our knowledge, experience, and connections to help farmers and their advocates grow and prosper. We hope Living Roots provides you with some food for thought, opportunities, and access to resources.

We would really love to hear from you. What you like about the magazine, what you wish we would include, a suggestion of something you might contribute — we are open to your feedback and hope you will take us up on it. It’s easy! Email livingroots@ ra usa.org or text us at 800.513.2803 (text only/no calls).

With best wishes for a continuing successful harvest,

RAFI is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and as such, donations are tax-deductible to the full extent allowed by law. EIN #56-1704863. RAFI believes in transparency, ethical accounting, and donor stewardship. RAFI has earned the 2022 Platinum GuideStar Exchange Seal and the sixth consecutive 4-star rating from Charity Navigator.

Email: livingroots@rafiusa.org

Web: rafiusa.org

Union Label

Beth Andrachick Hauptle RAFI Senior Communications ManagerPS. If you do not wish to receive this magazine, please write to livingroots@ra usa.org and we will take you o the list.

2023 Infrastructure Grantee & Meet the FOCN Team

CHUE LEE IS one of 11 farmers who were chosen out of a competitive pool of applicants to receive a 2023 RAFI Farmers of Color Network (FOCN) Infrastructure grant. Since 2020, $861,536 has been awarded to farmers in 11 states in the Southeast U.S. and U.S. Caribbean. Lee’s One Fortune Farm, a 90-acre stretch of land in Western NC, is farmed by a group of relatives from the Hmong community who follow the traditional practice of cooperatively growing food to feed their families. They grow fruits, vegetables, heirloom rice, and just under 1,000 fruit trees, including specialty Japanese blood red plum trees, seven varieties of Asian pears, eight plum varieties, seven peach varieties, two persimmons, and four types of nectarines. With their FOCN grant, the farm plans to construct a much-needed new building for washing and processing produce.

Several new staff members joined RAFI’s FOCN program team recently. Learn about them on page 7.

WHETHER IT BE WINDS, rains, heat, or drought — natural disasters are an inevitable part of farming. But good preparation and recordkeeping before a disaster can make the di erence when a farm faces recovery ahead. RAFI’s Disaster Assistance webpage (see QR code above) is a great tool to learn more about how to prepare before a disaster occurs and what you can do to speed recovery immediately after. Here are some top tips!

Before a Disaster

• Have an FSA Farm Number and update your FSA record annually

• Submit a map of your farm/crops to the FSA o ce

• Keep important documents organized and on hand (leases, agreements, harvest records)

• Specialty crop producers — consider signing up for NAP crop coverage

• Learn about USDA disaster relief programs (ECP, ELAP, LIP)

After a Disaster

• Immediately document all damage through photographs, videos, or notes (remember, camera before chainsaw)

• Call your FSA o ce to report any farm damage

• Know which agency to contact for assistance

USDA: farm operation losses/damage

FEMA: household and home losses/damage

SBA: other business losses/damage

Call RAFI’s Farmer Hotline if you need additional help: 866.586.6746

Did you know there’s a grant available that allows farmers to test out new ideas, practices, or technology that would address a production or marketing challenge? It’s called the Southern SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education) Producer Grant Program. This is a research grant program available to individuals or farmer groups to test out a sustainable agriculture idea using a field trial, on-farm demonstration, marketing initiative, or other technique. Typically, grant proposals open in September with final proposals due in November. Producer grants are paid by reimbursement of allowable project expenses for a maximum of $20,000 to individual farmers and $25,000 to farmer groups over two years.

SARE’S FOUR REGIONS. Check for programs in your area.

If you have a new idea for production or marketing that you’ve wanted to research, visit southern.sare.org to learn more. Not in the Southern region? The other three SARE regions (Northeast, North Central, and Western) also have farmer grant programs although the timelines, applications, and grant award parameters vary.

In August 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, including two sections (22006 and 22007) with provisions that will provide financial assistance to farmers in certain situations. We include updates on the implementation of these sections below:

Section 22006: Payments for producers in financial distress

There have been several rounds of automatic payments for FSA borrowers in financial distress (just before our print deadline, USDA announced a new round of automatic payments for guaranteed loan borrowers) and there are currently a few application-based assistance opportunities for certain kinds of FSA borrowers. Application-based assistance has an application deadline of December 31, 2023. Read more about eligibility details, timelines, and the application process at farmers.gov/22006

around about this program. Please be aware:

• It is NOT a lawsuit.

• Community organizations are available to offer free technical assistance completing applications.

• Producers should not have to hire a lawyer in order to apply for the program.

• There is NO FEE to apply.

in cooperative agreements with non-profit organizations who will partner with others to provide technical assistance and wrap-around support for transitioning and existing organic farmers.

TOPP provides technical assistance and mentorships designed to help producers overcome technical, cultural, and financial shifts during and following organic certification. Our partnership with TOPP has just begun. Look for more information from us later this year on how to get involved.

Carolina and beyond. This conference is made possible by generous support from The Duke Endowment.

Section

The application is open with a deadline of October 31, 2023. For the most current information, please visit farmers.gov/22007. There is much misinformation

Have you been considering transitioning your farm operation to organic practices and becoming certified organic, but found the process daunting? Have you already transitioned to organic but are struggling to find your feet?

RAFI is pleased to announce our partnership with the USDA’s Transition to Organic Partnership Program (TOPP), which is investing up to $100 million over five years

The Come to the Table Conference will take place at Word Tabernacle Church in Rocky Mount, North Carolina on October 3-4, 2024. The guiding theme for the conference is “Food, Land, and Sacred Stories,” which will explore these pieces as individual concepts and as a continual thread through the lens of race and equity. With a special emphasis on lived stories, the conference will incorporate storytelling and storymaking in several different mediums, featuring workshops, panels, keynotes, and networking events. We are inviting faith leaders and laypeople, farmers, community organizers, and other food justice advocates to find mutually beneficial solutions to strengthen just, sustainable agriculture in North

SEPTEMBER 23

Noblesville, IN Farm Aid

OCTOBER 20-22

Philadelphia, PA Black Urban Growers (BUGs) Conference

NOVEMBER 1-2

Stockton, CA

The 2023 Latino Farmer Conference

NOVEMBER 11-13

Durham, NC Carolina Farm Stewardship Association Conference

JANUARY 6-8

Roanoke, VA Virginia Association for Biological Farming Conference

PRO TIPOVER THE PAST few years, RAFI has forged new relationships in the U.S. Caribbean territories, leading to the development of the Caribbean Farmers Network (CFN). As founding members of this multi-organizational collaboration RAFI, Alliance for Agriculture in Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands Good Food Coalition seek to connect Caribbean farmers with resources and support, from farm financial information to policy advocacy. These farmers, being U.S. citizens, qualify for many of the same USDA programs as mainland producers. However, geographic isolation, the lingering systemic effects of colonial dynamics, intensifying

effects of climate change, and cultural and racial differences often leave Caribbean farmers out of the loop.

RAFI’s Executive Director Edna Rodriguez helped guide the formation of this collaboration. Given her own experience growing up in the Dominican Republic, she feels strongly that working in partnership with organizations on the islands is the best way to strengthen farmer viability. Working side-by-side, we can avoid repeating the dynamics of “parachuting in to save the day,” and instead provide assistance where it’s most needed and sought.

Our efforts in the region have grown to include:

• Encouraging USDA to provide better service and support farmers.

• Increasing the visibility of the territories and farmer challenges among food/farm organizations with the intention of bringing new programs, services, resources, and funding.

• Strengthening the capacity of local organizational partners.

• Extending and modifying the Farmers of Color Network re-granting programs to offer grants to CFN farmer members.

• Extending RAFI programs of technical assistance and farm advocacy in partnership with organizations on the ground.

• Incorporating issues identified as relevant by farmers in the territories in RAFI’s Farm Bill platform, and sponsoring a delegation of farmers and advocates from Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to lobby congress in D.C. during the Farmers for Climate Change: Rally for Resilience in Spring 2023.

• Engaging culturally competent, Spanish-speaking staff to serve as a point of contact for farmers.

RAFI’s engagement in the region reflects our unwavering commitment to racial equity and climate resilience. We focus on serving those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, a commitment central to our organizational ethos. Working in partnership with our colleagues on the islands, we look forward to building a farmerdriven network focused on regional food sovereignty and resilience.

RAFI’S

OF COLOR Network (FOCN) continues on a growth trajectory since its founding in 2017, with 754 members currently on its roster. In addition to its re-granting programs, FOCN offers online and in-person trainings, technical assistance, farm tours, networking events, and gatherings that highlight ancestral traditions and market access solutions.

Currently, the program serves farmers of color in the Southeast U.S., U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico through the recent addition of a satellite network, the Caribbean Farmers Network. (See opposite page.)

Mary Saunders Bulan, Farmer Services Director, brings both academic and practical knowledge to the FOCN team. She has a Ph.D. in Agronomy and years of farming experience. After working as an agriculture researcher and professor, she yearned for a more applied setting. With RAFI, she has found an inspiring group of farmers with whom to continue her work in a very direct way. Mary and her partner run a small herb, flower, and vegetable farm in Western NC.

Carolina Alzate Gouzy, Farmer Outreach Manager, has worked on agroecological projects, primarily in Latin America with nonprofits seeking a more just and regenerative relation-

ship between rural and urban worlds. Carolina is a biological engineer with a master’s in Agribusiness and a Ph.D. in Sustainable Development from Universidade de Brasília, Brazil. Carolina wears several hats at RAFI, helping farmers access USDA conservation and disaster assistance, supporting the FOCN team, and working with farmers in the U.S. Caribbean.

Jeremy Hart, Climate and Equity Technical Assistance Provider, is FOCN’s newest team member. He has a bachelor’s in Agribusiness from NC A&T University. Since then, he has worked with various agencies of the USDA, and gained farming experience while providing counseling and advice to farmers. Jeremy serves as lead technical advisor for a new RAFI project: A Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities. He advises farmers on climatesmart practices leading to the creation of a regenerative plan and A Greener World Certified Regenerative designation.

FOCN Membership Manager Humon Heidarian’s interest in creating and sharing good food — with knowledge of its origin and ingredients — is deeply rooted in his Iranian heritage.

While working as a farmhand at ECO City Farms during the day and volunteering for Prince George’s Food Equity Council at night (both in Maryland), he developed a passion for working at the intersection of agriculture and food justice. He has a bachelor’s in Environmental Science from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and an MPA from the University of Vermont. In addition to his role with FOCN, he is a policy team lead on urban farming.

B. Ray Jeffers, FOCN Director, has been at RAFI since 2021 bringing his experience as a farmer on his family’s 200-acre century-old farm in Roxboro, NC which was purchased by his then-19-year-old great-grandfather. Ray grows produce, hogs, and layers on this land.

He is grateful that his work as a farmer, a farmer advocate, and a NC State Representative allows him to stand up for farmers and develop policy in NC that impacts farmers and our food system.

Otis Wright, Farmer Resources Coordinator, assists farmers with obtaining FSA loans, working remotely from his home in Pearl, MS. Otis enjoys helping new farmers and likes to see them start from nothing and grow into a full-out farm. Otis brings a wealth of experience in helping farmers with USDA programs, experience he learned on the ground as he navigated USDA’s policies and procedures himself. He now uses this knowledge to help other farmers have successful outcomes with the USDA.

In the summer of 2020, RAFI’s Come to the Table program staff member Jarred White asked the question: what would it look like for faith communities to be in sustainable, mutually beneficial, and practical relationships with farmers?

Instead of one-time produce purchases or the occasional farm tour, how could a faith community financially support and enter into a relationship with a local farmer? What if this support could benefit a local farmer of color who has long faced systemic discrimination? Conversely, how could a farmer and their fresh produce benefit a faith community’s ministries, which provide food for many food insecure community members?

These questions led to the creation of RAFI’s Farm and Faith Partnerships Project. This project aims to address injustices in the food system that marginalize rural communities and farmers of color. It does this by creating partnerships between farmers who are members of RAFI’s Farmers of Color Network and faith groups in their local areas.

RAFI’s Executive Director, Edna Rodriguez, talks about the genesis of the project: “Now is the time to invest in the work of transforming local and regional food supply chains. Through leveraging existing relationships and the trust we have built with farmers and faith communities, RAFI is committed to creating that change.”

The Farm and Faith Partnership Project centers community supported agriculture (CSA) shares (a weekly food box

subscription) among a group of churches with one or more farmers of color in the area. Come to the Table helps pair the churches and farmers, then church members commit to purchasing shares for themselves and/or for their food ministries before the season begins.

What started with a handful of churches and a couple of farmers in Wake County, North Carolina, has now spread to include eight CSA projects made up of 20 congregations and more than 10 farmers.

The pilot project launched in April 2021 and after three years and eight seasons, the CSA has grossed more than $150,000 for the farmers and doubled its seasonal shares to more than 220 members.

“Bless the hands that plant, prune, and propagate. Bless the seeds, the bugs, the animals. Bless the labor and the work. Bless the people who eat from the land, their bodies, their minds, and their hearts. Bless the community that dreams of sustainability and equality and creation justice. Bless the farmers. Bless their ancestors. Bless the churches. Bless the creative minds at RAFI. Bless our budding relationships and new friendships.”

—Rev. Lacey Brown

Steve and Elke McCalla, owners and operators of Rocky Ridge Farm in Louisburg, NC, are original partners in the Wake County CSA. Previously selling produce at local farmers markets, the CSA has been a nice change of pace for them, allowing them to operate at their peak production and have reliable and stable market access.

“We would like to share our gratitude,“ Steve McCalla said. “[Because of the CSA], we basically transitioned from a small farm to a medium sized farm.”

In the Wake County CSA, each farmer is paired with one to three faith communities whose members and ministries sign up for CSA shares before the growing season. After sign-ups, the farmers know exactly how much they need to grow for that season.

McCalla recounted experiences of his fellow farmers who faced hardships due to market rain-outs during the spring and summer seasons. He further explained how the CSA model can provide stability for farmers by minimizing the unpredictability of sales, which can often be a ected by factors beyond their control.

“With the CSA, we know exactly how many shares we have, we know what to plant, it’s not hit or miss, everything that we harvest is already sold and the money is provided up front,” McCalla said. “So the supplies, input, equipment, and maintenance that we need to sustain ourselves, we have that budget up front each season.”

Patrick (Rick) Brown is a fourthgeneration farmer in Henderson, NC, whose products are also featured in the Wake County CSA. Brown sells a lot of his produce wholesale, but still sees the CSA as an added bene t to his farm.

“I feel like [a CSA] is one of the ways that farmers can have a secondary market for what they’ve already been doing in order to add diversi cation to their farm portfolio,” Brown said. “Through RAFI and the Farm and Faith Partnerships Project, it’s easy for a small farmer to get set up to put this into production, because they’re already doing the work and it guarantees a market for their produce.”

One added bene t of the Farm and Faith Partnerships has been that farmers can focus on what they do best — growing

What do you grow in bulk that you can sell? What are your price points? How often will you have these items available? Do you need pick-up from the farm or do you have the tools needed to drop-off?

Learn more about the desired outcome of your partner — what types of produce do they need and how often? How long of a commitment are they looking for?

What contingency plans (i.e. crop loss, economic shift, personal injury, etc.) need to be put in place? How will the shareholders pay and how often? Will you offer work days or farm tours to engage with church members?

and harvesting food — and not have to divert their energy away from farming and toward marketing.

“Our attention is o of trying to market for ourselves and the churches are actually supporting us by marketing our work,” McCalla said. “That frees up time for us to be able to look at buying plants or materials that we would normally not have had time for.”

Not only have the partnerships been unique market opportunities for the farmers, but they have been a way to build community.

For the last three years, farmers and shareholders from the CSAs have joined together at a participating farm and held a blessing of the land. For owner and operator of Singing Stream Farm, Ken Daniel, the blessing of the land was a selling point for joining the CSA.

“When I rst joined the CSA, [the other farmers] were making preparations for the rst blessing of the land event,” Daniel said. “And I thought to myself, ‘blessing of the land?’ Now that sounds like something I want to be involved with.’”

Brown said one of the most bene cial parts of the experience has been getting to know the shareholders at his partner church, St. Francis of Assisi, in Raleigh, NC.

“We’ve been able to go to the church and introduce ourselves, tell our story, and build a relationship with them,”

Brown said. “Even though we’re not members of the organization, we feel as though we are.”

The McCallas echoed Brown’s sentiment, detailing the list of activities they’ve collaborated on with their partner church, including a presentation on Earth Day, a hands-on activity of transplanting cabbage with the children of the church, and volunteer days at the farm building a new fence.

“On Saturday mornings it’s not like we just drop the vegetables o and take o ,” McCalla said. “We stand and chat, and people ask us all kinds of questions, so it’s kind of a warm and cozy place to be on a Saturday morning.”

If you are interested in learning more about the Farm and Faith Partnerships Project, or if you are a farmer in North Carolina who would like to be connected with a faith community in your county, contact the Come to the Table team at cttt@ra usa.org.

For those of you interested in seeing how the program may t into your community, RAFI o ers a video and guidebook. Scan the QR code above with your phone’s camera to access the materials.

DAVID ALLEN works as Come to the Table’s Project Manager, focusing on the program’s event, cohort, and communication efforts. David is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke Divinity School.

Take a walk through the Fountain Heights neighborhood of Birmingham, Alabama, and you’ll find gardens bursting with edible color: bright rainbow chard, fuschia beets, magenta sokoyokoto (more on that later), amethyst basil, greens galore, a hot palette of peppers. The greening of this space has taken the work of dozens of volunteers. Behind that effort is a couple motivated to create a healthy, nourishing village within a city. M. Dominique Villanueva runs Fountain Heights Farm with her husband Christopher Gooden and the farm has blossomed from their front yard garden to five city lots, producing thousands of pounds of food annually. Villanueva also works to help enroll local farmers in USDA farm programs, and currently serves on RAFI’s Board of Directors.

Villanueva and her husband began growing food out of

financial necessity when they decided to buy a home. Already working full-time jobs, they gardened in order to purchase their house. Then they began, almost accidentally, to transform their community. She says, “Before we fixed up the house, we made the garden.” Elders would walk by, admire the vegetables, and stop to talk. They usually walked away with a zucchini or cucumber.

Sharing the abundance came naturally, and so did the growth of their operation. Villaneuva set up a table in front of their house. Before long, she thought, “What if I’m not out here?” She set up a donation table, and the next year Gooden built a community pantry. They then started farming the lot next door. “We went from eight rows in 2017 to 21.” Now in 2023, the farm spans five lots and expansion is an ongoing process.

Arson had damaged the neighboring property in 2009 and the owner was unable to rebuild. Villanueva learned through

the city how to acquire the lot and started talking with neighbors. The elder who owned it told her, “You don’t need to own my property to grow on it,” so they went ahead and planted crops. After a year, the owner sold it to them. Villaneuva was thrilled: “This is a vision of what it looks like to feed an entire community, touch the earth, and connect with nature. Our vision is to have enough space and grow the next generation to sustain our community’s needs for fresh produce. Now we are working on infrastructure, a need for farmers everywhere: access to water, wash and pack, refrigeration, distribution. Once those things are built, they can be shared.”

The farm has also grown in crop and production system diversity. The aquaponics learning center teaches people soilless farming. It’s not just a novelty: Birmingham has a history of industrial pollution that has poisoned the soil in some parts of the city. Villanueva and Gooden have a SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) grant to test growing mushrooms on the wood of the weedy, fast-growing Mimosa tree. (See page 4: On-Farm Research Grants.) This summer they’ll plant their first urban pumpkin patch and an urban orchard will go in the ground this fall.

Villanueva developed her taste for agriculture as a child growing up in rural Washington state. She fondly remembers her great uncle’s petting farm: a menagerie of donkeys, minihorses, and pheasants. Now living in the South, she calls the “endless growing season,” first and second summer.

Villanueva’s favorite crop is called sokoyokoto: Nigerian spinach. It’s a bright magenta celosia (C. argentea) with vibrant flowers and delicious greens, and it’s drought and heat tolerant. She first encountered the plant while working at an urban farm where it was used only in bouquets. Villanueva’s seed stock was given to her by seed-saving and Southeast gardening legend Ira Wallace, who told Villanueva about its food and cultural value. “It makes beautiful greens and flowers, it reconnects us with West African heritage. It’s now my favorite thing to grow and cook. We include it in bouquets. I love to share the seed,” says Villanueva. She continues to spread the sokoyokoto love, and these days, you’ll see the plant brightening up vegetable beds and community gardens throughout Fountain Heights.

Along with farming, Villanueva works to connect eligible growers to USDA programs. She explains, “Helping farmers and connecting them with resources is a natural extension of being a good farmer. Farmers are at their best when they work together.”

Villanueva wants people to understand how hard the physical labor of farming is. “A lot of people can conceptualize: it’s hot, it’s outside, and physical. But when you are in it, as a mother, living the experience of poverty, carrying your kid on your back, and harvesting beans … the picture is sweet, and it is sweet. And the other side is the lack of access to childcare.”

She says, “It’s courageous to farm. Especially in relation to the new climate. Especially for urban farmers, with changes in microclimates. Also it’s courageous because, if you have a background that is traumatized by what it means to be in agriculture, you don’t usually have the support of your family to be a farmer. It’s courageous to work in an industry that is underpaid. Society considers us unsuccessful people, even though farming literally sustains us all.”

As her inspiration for this work, Villanueva credits an “ancestral pull,” and also points to the youth. “I’m not old, but I’m not young. And I see young folks making the decision to farm, and it’s inspiring. Volunteers, people in their early 20s and 30s. They bring such joy, and I want to keep these spaces for them, so they can have a place,” she adds.

After nearly a decade of farming, Villanueva is proud of the balance she has achieved. She works hard, does her best, and yet understands that one can’t control the plants or the harvest. She is happy to have found the “deep respect that comes with not being in control, and being okay with it.”

“You get to define what farming is. I define it as growing enough to feed others. You can start small and grow. Farming literally teaches you that everything starts small and it grows.

In the farming villages of our ancestors, people worked together as a way of life, sharing labor and other resources in relationships of trust, reciprocity, community responsibility, and necessity. In this respect, agricultural cooperatives are a holdover from the past, but they can also offer a strategy for the present. The collective power of the cooperative can be a lifeline for farmers with limited individual access to resources like capital, equipment, land, and markets. Historically co-ops have taken many forms, from the ambitious Freedom Farm Cooperative of Fannie Lou Hamer to the modest general store in many rural towns. RAFI staff profiled three active cooperatives who are navigating the highs and lows of joining forces on the farm.

Carolina Alzate Gouzy spoke with Ángel L. Rodriguez, of the Cooperativa de Porcicultores de Puerto Rico;

Angel Woodrum interviewed Delia Jovel Dubón of Tierra Fértil Co-op in Western North Carolina; and Jaimie McGirt talked with Tonya Pennix of the Piedmont Progressive Farmers Cooperative in the North Central Piedmont region of North Carolina.

The Cooperativa de Porcicultores de Puerto Rico (CPPR) was

initially organized in 2009 in response to the risk imposed on local producers by an increasing supply of pork from the U.S. mainland and Canada. At that time Puerto Rico had hit a never-before-seen low in production. Only 2.61% of the pork sold on the island was locally sourced, while the remaining 97.39% came from new-entry external markets. According to Ángel L. Rodriguez, Purchasing, Sales, and Marketing Director of CPPR (Puerto Rican Hog Farmers Cooperative), farmers started to think about how they had lost so much market share and realized that, “We weren’t unified, and we were struggling individually.”

In 2009 Rodriguez and a group of farmers started to organize themselves as a cooperative with a unified mission and vision. By 2013 they were well-organized but still felt their final product needed improvement to compete with imported pork. They took on that challenge, breeding swine adapted to local climate conditions and meeting taste preferences for layered fat, showcased in signature dishes like lechón, roasted suckling pig. By 2017 the co-op was blossoming with membership of more than 70 small pork producers.

Rodriguez says that their main strength lies in working together. They are getting more and better products to their clients. They have access to new funding and resources. They have gained the respect needed to negotiate with the government and industry and to demand attention for their sector.

BY CAROLINA ALZATE GOUZY, JAIMIE MCGIRT, AND ANGEL WOODRUM

Rodriguez is proud to share that local pork production is now nearly 7% of all pork consumed in Puerto Rico and growing.

Low-price imports continue to present a major challenge. “How is it possible,” Rodriguez asks, “that imported pork is cheaper? A pork chop that is sold for $4 to $6 dollars per pound on the mainland is sold in Puerto Rico for $1 to $2 dollars per pound,” he states. “How is that possible?”

Rodriguez’s advice to anyone considering forming a co-op is to “Be prepared to work with human beings. They naturally like to work individually and it is hard for them to cooperate.” He believes that the best way to organize a group like this is by setting a good example and not merely with words that are often “taken by the wind.” Rodriguez himself wasn’t trusted at the beginning. But he says when farmers saw his way of producing and doing business, he started winning their trust and allegiance. “We need more leaders with a heart!” Rodriguez proclaims.

Since last year, CPPR and RAFI team members have been working toward the goal of a co-op-owned processing plant. RAFI introduced CPPR to the Flower Hill Institute, an Indigenous-led nonprofit that is assisting CPPR in the planning and design of its slaughterhouse. Prospects look good, especially since FIDECOOP, a PR-based nonprofit serving co-ops, was recently awarded funding from the USDA Rural Development Meat and Poultry Intermediary Lending Program (MPILP) to support CPPR in owning and operating its own facility.

Move now to the verdant peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and you’ll find Tierra Fértil Cooperative, a Hispanic, worker-owned farm cooperative whose purpose is “to set a precedent to reclaim and recover knowledge, resources, autonomy, capacity, and collective power to create a more sustainable, fair, and equitable life for the Latinx community and people of color.” Together, the members of Tierra Fértil grow a variety of vegetables and herbs, which can be found at farmers markets in the Asheville, NC area.

When Delia Jovel Dubón and a group of founding members created the co-op, they weren’t necessarily planning to create a business. It started as a community initiative in 2020 to create food access and food sovereignty in their community during the pandemic. Dubón explains, “We were concerned about having access to food because a lot of us lost our jobs. We just wanted to get food to our community.”

Dubón explains that the Hispanic community has a deep connection with farming; many came from farming families and from countries with many farms. “We have lost that connection. The way we live now, you buy everything. I was craving a sense of belonging, and farming was an excellent way to get that,” Dubón shares. “The reason we decided to create a cooperative was because we believe in collective power, we believe in protecting us, we believe in the need to share capacities, to share knowledge, and create community,” she adds. “I believe a lot in working together. It was the only way to try (farming), honestly. Every person brings different capacities and knowledge. As an individual, you aren’t able to do and bring everything. Working together is more possible,” she shares.

Like Ángel Rodriguez of the Pork Cooperative in Puerto Rico, Dubón notes that many people believe that success

is individually based. “If I want to be successful, I have to think just about me, and not the others. I think it’s because we don’t understand how to work together anymore. Working together, you have to be concerned about all of our success,” Dubón says. And, again like Rodriguez, Dubón notes the lack of trust among people and the patience it takes to earn mutual trust.

While building its processing facility poses the largest challenge for CPPC, land access is the single biggest challenge for Tierra Fértil. “We are so grateful to have a partnership that allows us to continue farming, but we need to focus on having access to land. It’s the only way to keep it Tierra Fértil. It’s essential,” Dubón says.

For egg producers, being able to “focus on your farm” is critical and so the benefits that come with being a member of a co-op — guaranteed markets and a fair market price — allows farmers to focus on what farmers do best, tend to their flocks. The Piedmont Progressive Farmers Cooperative (PPFC) is providing central NC markets with fresh eggs from pasture-raised chickens and providing its farmer members with services like a website, packaging materials, marketing, as well as equipment to wash, weigh, and package the eggs.

PPFC began as a grassroots nonprofit in NC, committed to food access, agricultural innovation, and equitable access to farm resources. Its intention to support underserved farmers was clear from the beginning; early members were African-American producers and PPFC continues to be led by an African-American board with a strong commitment to farmers of color.

The co-op is more than just a business venture. Tonya Pennix, member and current Board President of PPFC, identifies the level of collaboration and mutual support as a deep source of power and pride. “Working together gives us a bigger voice — not only as small farmers — as people involved in the importance of agriculture and its future,” said Pennix.

The group has recently added aggregation of vegetables, fruits, and meat to its slate which has been successful in bringing in new farmers, some of whom take advantage of the starter flock program to begin raising egg layers. Add the new bulk-buying cost reduction strategy and you have a membership well worth joining. RAFI Farmers of Color Network Director Ray Jeffers recently joined the

co-op and started a new flock on his farm!

But with scaling up farm operations comes the need for both infrastructure and environmental conservation. Sam Crisp, a PPFC founding farmer-member and current board member, strongly advocates that farmers access cost-share assistance for environmental enhancements. Because of Crisp’s familiarity with USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) programs, he has introduced many PPFC members to their local NRCS office.

While membership is growing, the demand for PPFC’s products is growing even faster. At a recent recruitment meeting, Weaver Street Market’s Merchandising Manager, James Watts, said to producers in the room, “We cannot keep the cooperative’s eggs on our shelves, and if you can produce more by growing your membership, we are dedicated to selling it.”

The co-op has outgrown its current processing facilities and is on the lookout for a permanent space to house the egg wash machines, cold storage, and office space, and Pennix encourages readers to reach out to her with any possibilities.

Pennix’s bright perspective on any adversity is unwavering: “Yes, there were probably roadblocks, but as a group we knew the importance of what we were and what we are working towards. Instead of viewing obstacles as blocks to stop us, we approached them as hurdles and learned to jump them or go around or under them — whichever worked best for the future of the cooperative and more importantly our members.”

Earth is the only planet known to have soil. This mysterious body has complex architecture, reinforced by biological glues exuded from roots, earthworms, bacteria and fungi: a living world underfoot ignored by most humans. Farmers, however, can’t afford to be oblivious. We still have much to learn about the networked ecological community underground, and the ways soil health drives agricultural productivity and resilience. But we are beginning to understand that this ecosystem needs to be conserved, nurtured, and fed.

Planting cover crops to build soil health is growing in popularity among farmers of all types. Cover crops are planted with the goal of providing ecosystem benefits, and not purely harvested yield. These benefits can include reducing compaction, improving water infiltration, preventing erosion, fixing

nitrogen, adding organic matter, suppressing weeds, scavenging nitrate, and feeding beneficial microbes. Species vary by soil type and climate. For example, while mainland U.S. farmers may plant vetch or clover for nitrogen, Caribbean farmers use tropical legumes like guandul (pigeon pea), canavalia, crotalaria, and mucuna. Cover crops may also add beauty, pollinator forage, and wildlife habitat. At our farm, flowering buckwheat and clover even play cameo roles in bouquets.

Cover crops are one of the most widely recommended and adopted farm enhancements of both the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) and Soil and Water Conservation Division (SWCD). Farmers already planting cover crops may be eligible for payments through the NRCS Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). Even producers trying them for the first time may qualify for cost-share payments through NRCS’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) or their SWCD. Though voluntary and competitive, historically underserved producers such as farmers of color and beginning farmers, can be eligible for higher payment rates and advance payments.

As the growing season winds down, now is a great time to plan for winter covers. Like any management adjustment on the farm, it is important to be clear about your goals for planting a cover crop, and how it will be managed from establishment to termination. Because it is usually secondary to the main crop, understanding timing and cost is key to making the practice worthwhile and successful.

Cover crops come in many flavors: fat daikons, delicate phacelia, towering sorghum, grinning sunflowers, creeping subterranean clover, sturdy southern peas, stately cereal rye. They can work in planting windows from a few midsummer weeks to an overwintered extended jam. They can be planted

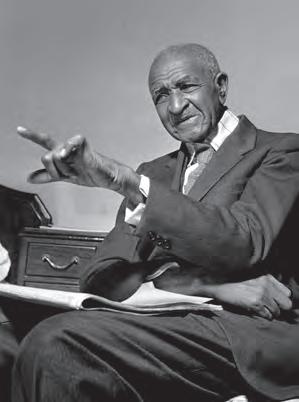

George Washington Carver (18641943), acknowledged as one of the most prominent Black scientists of the early 20th century, was instrumental in promoting the concept of soil conservation and health, particularly through his research and educational efforts to introduce and popularize certain farming practices that benefited the soil.

He is perhaps best known for his work on promoting crop rotation, specifically alternating nitrogen-fixing legumes, such as peanuts and soybeans, with soil-depleting crops like cotton. Nitrogen-fixing plants can convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that plants can use. When these plants die and decompose, this nitrogen becomes available to other plants, enriching the soil.

He also advocated for alternative crops like sweet potatoes and legumes which are beneficial for the soil, as they are less demanding in terms of nutrient extraction compared to cotton, and also add market value for the farmer. Carver’s work laid the groundwork for what we now know as sustainable agriculture. He advocated for the use of local resources, waste reduction, and organic matter recycling, which help maintain the structure and fertility of the soil.

in “cocktail” mixes or alone, and make a useful addition to the soil health toolkit for farmers at every scale.

Jamie Stallings farms cotton, soybeans, corn, and peanuts in northeastern North Carolina. He grows on 2,300 acres in Perquimans, Pasquotank, Chowan, and Gates counties, and has participated in cover crop trials with NC State University. Stallings plants wheat as a winter cover crop to prevent soil erosion, reduce tillage, retain soil moisture, and control weeds. He says, “The ground we plant peanuts in is sandy, so having a cover crop on that land is especially important.” Stallings started planting cover crops in vulnerable elds to prevent soil loss from winter storms. When he saw the bene ts, he incorporated them into the whole operation. Stallings begins seeding wheat around October 15, and in mid-November switches to cereal rye because it will emerge in cooler weather.

At the other end of the scale, Natasha Shipman manages three-fourths of an acre of vegetables for CSA and farmers markets in Western NC. Shipman says, “I use cover cropping two di erent ways. In summertime, if there’s an area I want to let rest, I plant a mix of species, usually buckwheat, sunn hemp, and sorghum or millet. Buckwheat is great for pollinators. In winter, when I pull a bed, I plant winter wheat, peas, and oats.” To save money she makes her own seed mixes, usually combining nitrogen- xing legumes with productive grasses. Of the bene ts of cover cropping, Shipman remarks, “It makes your garden look so beautiful. It keeps the weeds down. It de nes the garden space, and there is something really satisfying about having that growth there all the time.”

Take heed, however, of potential pitfalls. Cover crops can be hosts for pests and pathogens and should be accounted for in rotations. Planting wheat as a cash crop following its use as a winter cover resulted in hessian y pressure in Stallings’ elds. For Shipman, terminating at the proper growth stage poses a challenge because “sometimes you need the bed earlier or later.” Grasses can go to seed and become weeds. In a busy season, managing cover crops can fall to the bottom of a farmer’s to-do list. Shipman prefers to mow her covers, and then smother with a silage tarp, a termination process that takes weeks in cool weather. She relies on a combination of exibility and ingenuity, sometimes with help from feathered friends. “I had an area that I let go too long and (the cover crop) went to seed. So I put the chickens on it, and they ate the grain.” Everybody bene tted.

Picture living roots in the farm eld all season, feeding your soil ecosystem and protecting the ground. Cost-share for starting and managing cover crops through NRCS could be available; contact your local agent to learn about eligibility. Or just give cover cropping a try. Stallings advises, “Talk with a farmer that is already growing cover crops, go to a eld day. There are lots of opportunities to learn.” —MSB

have

reach spanning decades and are strangling the food system at every level. So what can independent grocery stores do to fight back?

Imagine going to the grocery store and the shelves being filled with locally produced goods. The fresh lettuce in the produce section was grown in a greenhouse down the street. The beef came from a cattle farmer you knew in high school. The baked goods were made by the familiar bakery downtown, which sources its wheat from a local farmer. Now, imagine all of this was priced so that the community the grocery store serves has access to this food easily — even in small, rural towns.

Today in the U.S. this sounds like a bucolic fantasy. Many community-rooted small and mid-scale farmers and ranchers would love to secure markets for their products in their community’s grocery stores. However, as of 2019 nearly 70% of U.S. grocery stores were owned by four giant corporations, led by Walmart — which captures a third of national grocery sales on its own — exerting even more extreme power regionally, controlling 50% or more of the food retail market in 43 U.S. metropolitan areas and 160 smaller markets across the U.S. according to a 2019 report by the Institute for Local Self Reliance. These massive national grocery chains cut costs by eliminating regional sourcing staff of the smaller grocery chains they’ve gobbled up, and instead, purchase food from their fellow dominant meatpackers and food processing corporations. Farmers seeking to plug into a regional food system are left on the outside, with fewer markets, untenable prices, and all too often, farm businesses on or over the edge of viability.

In the process of vertically integrating and centralizing their procurement, dominant grocery corporations have locked independent farmers out of a broad swath of mainstream marketing opportunities. Nonetheless, regional farmers used to still have an avenue to thrive in the retail space: the independent grocery store. But today, the surviving

independent grocery stores are also dealing with predatory abuses of market power by wholesale distributors, also known as “broadliners.” Broadliners aggregate massive amounts of food to distribute to grocery stores and control access to a majority of the types and brands of the food that are in most demand by consumers. To grow and profit, every grocery broadliner wants to hook a whale like Walmart or Kroger, which would mean a multi-million or perhaps even billion dollar contract. To help them acquire the biggest customers with the biggest contracts, they are prepared to offer huge discounts to get these retail whales in the door. To make up the cost of offering larger chains discounts, small independent grocery stores are forced to pay a premium to broadliners to get the same products on the shelf. But it doesn’t end there.

These mega-corporations

a wide

INTERESTED in learning more about retail grocery concentration?

Read RAFI’s May 2022 comment submitted to AMS, USDA

Independent grocery stores have increasing pressure to match the shopping experience that customers expect from big box retail chains. That space is all about convenience, creating a one-stop shop with everything you need for the week on the shelf. Many of these products can only be purchased from broadliners. Independent grocers not only get less favorable prices from broadliners, but the contracts include minimum purchasing quantities. Sometimes this is a speci c dollar amount, but often it comes in the form of a percentage. It is not uncommon for broadliners to stipulate that independent grocers must ll 70% of their store with their products if the grocer wants to do business at all.

Approximately 8% goes to small vendors, according to Danny Peed, general manager of Market Plus IGA in En eld, NC, leaving an even smaller percentage available to purchase directly from small to mid-scale farmers in the grocer’s area. Peed explains, “If you look at just 35% left over from the broadliner, you’re forgetting now that you still got Coke, you still got Pepsi, you still got Frito Lay, you still got Sunbeam, you still got all your other small vendors that it’s still going to take at the very least another 8%.”

The result is what you see today. Nominal (if any) o erings of locally farmed products at big corporate chains, and limited o erings of locally farmed products at smaller, independent grocers. What’s more, because independent grocers pay more for the products, they face tighter margins in setting

retail prices for their customers. They risk not breaking even if they don’t raise their prices. This is a di cult tightrope to walk for grocers, as the impact of corporate consolidation has hit consumer wallets too. Especially in rural towns, a grocer’s customers might not enjoy the purchasing autonomy in supporting local businesses at a higher price.

These mega-corporations have a wide reach spanning decades and are strangling the food system at every level. So what can independent grocery stores do to ght back?

James Watts is the Merchandising Manager at Weaver Street Market, a network of four co-op grocery stores in the Triangle area of North Carolina. Weaver Street Market enjoys signi cantly lower demands on purchasing percentages from broadliners than most grocery stores today, but that wasn’t always the case.

“The biggest distributor in natural foods had done a huge contract with Whole Foods that gave Whole Foods their outsized pricing power. All of us independent grocers were looking at each other going, oh, ‘what are we going to do? Okay, well, we better band together.’ And so we formed a trade organization and we started to negotiate as a unit. We collectively bargained with the broadliner and said, ‘Collectively, we’re your second largest customer,’” Watts tells us.

Weaver Street Market was able to receive a more favorable contract with a broadliner through collective bargaining, which is undeniably a tactic with merit. But the

that Weaver Street serves at its four locations tend to be affluent, and the stores are filled with organic, vegan, gluten-free, and premium items as well as prepared foods made at a central kitchen.

“I’m going to say this pretty clearly and upfront. Our retailing environment is different than the vast majority of independent retailers out there because most independent retailers have a contract with a distributor that requires a much higher percentage of overall purchases to go to that wholesale partner. In my case, we get somewhere between 20% and 30% of our purchasing at any given moment. If you are an IGA affiliate down in Southeastern North Carolina, your contract with your supplier probably requires you to buy somewhere between 70% and 90% of your food from them,” Watts explains.

IGA’S Danny Peed wants to take a different approach, but with a similar underlying concept. Peed imagines a network of grocery stores mutually supporting an independent aggregator that collects food and products from farmers and other suppliers to stock independent grocers. This would allow the complete elimination of the broadliner contract. He stresses that a smaller model like this could allow small grocers to cater to the niche of their area.

“So to cater to a single customer, even if you got four of a product on the shelf and if you sell them at one a week or one every two weeks, you still satisfy that customer in the neighborhood. And it won’t really put you out, especially if you’ve got a centralized location where your other stores are within an hour or two away,” Peed says.

Aaron Johnson, who manages RAFI’s Challenging Corporate Power program, explains that he would like to see the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) take action against broadliners that use their market power to bully independent grocers into bad contracts. “We’d like to pressure the FTC to do an economy-wide rulemaking against exclusive contracting on the part of dominant firms. We want them to say: ‘If your firm controls more than 30% of the market share of a relevant market, which could be a national market or regional market, you can’t compel your customer network, your clients, to sign exclusive contracts with you.’” The FTC could also, for the first time in decades, enforce the Robinson Patman Act, which, Johnson explains, “was originally passed to protect community stores from being driven out of business by national chains, by prohibiting dominant wholesalers and

retailers from offering or requiring anti-competitive preferential discounts, and then charging smaller or independent grocery stores unfairly higher prices for goods.“

The consistent vertical integration of markets affects every aspect of our food system. Independent farmers, grocers, processors, and more are all finding the market space they rely on to be increasingly hostile terrain. However, consumer tastes and preferences have been trending toward a higher demand for locally farmed goods, which is increasing pressure on the current market paradigm to shift. Farmers need a consistent customer to budget their growing seasons and many independent grocers want to meet the demands of their local communities with locally farmed goods. The question remains whether legislators will make an overdue course correction for working-class U.S. citizens, or if they will continue to feed a few mega firms that have a stranglehold on markets.

Feast Down East’s Impactful Journey

Feast Down East is a nonprofit organization based in Wilmington, North Carolina, offering farmer support, hunger relief programs, and a food hub distribution program. The organization partners with local farmers to purchase food which is distributed to the community via its mobile farmers market, food hub, and Emergency Food Relief Program. Feast Down East’s mission is to “strengthen the farming communities in and around the Wilmington area by providing resources, education, and distribution opportunities to farmers while addressing equitable food access in communities with the greatest need.”

RAFI Market Access Coordinator, Angel Woodrum, spoke with Feast Down East’s Food Hub Operations Manager, JT Crawford, about how farmers can partner with Feast Down East.

Angel Woodrum (AW): Tell me about your work with Feast Down East (FDE) and what FDE does.

JT Crawford (JTC): FDE has two main components, the Food Hub and the Mobile Market.

As the Food Hub manager I work directly with our farmers and customers to coordinate deliveries of local and fresh produce. The Food Hub is also responsible for all farmer engagement, onboarding new farmers and customers, and coordinating deliveries.

Our mobile market goes into underserved communities to bring the same products that fine dining restaurants downtown order at a wholesale cost, while also being able to use SNAP/EBT,

which we are able to double. We are also incorporating a whole new route to serve rural communities through BlueCross BlueShield Medicare funding to target rural and elderly populations.

AW: How does FDE engage with farmers?

JTC: FDE engages with farmers by visiting their farms to see where our products are coming from. We provide technical assistance when farmers are lling out necessary paperwork. Additionally we cover delivery costs for farming supplies like wax boxes, clamshells, and baskets, and we are able to sell packaging at cost with no markups. When harvest time comes we can gather a volunteer group for a “crop mob” for farms needing assistance. We arrange for Carolina Farm Stewardship Association to provide food safety workshops for our farmers. And nally, we advise farmers about crop planning and share other sales opportunities available to them.

AW: If a farmer is interested in selling to FDE, what is the process for that? Are there any certifications they would need to have? What about best practices?

JTC: To work with Feast Down East we ask that each producer go through our onboarding process. FDE is a GAP certi ed facility so we do require each farmer to ll out necessary paperwork such as a Grower Approval Questionnaire (in which farmers share what they grow and their practices) and Farmshare documents (Food Safety Policy and Farmshare Grower Questionnaire). We encourage farmers to follow best practices like ensuring all pro-

duce is free of dirt and blemishes when products arrive to us and using proper packaging such as wax boxes for produce, tomato boxes for tomatoes, clamshells for berries, and plastic bags for herbs.

AW: What sort of contract is in place for farmers selling to FDE?

JTC: FDE does not have a formal contract with the farmers we work with. However, I am in the process of nishing our producer contract, an in-depth document that covers how farmers should wash and package their products, FDE’s customer expectations, our markup to cover delivery costs, and the times for availability, ordering, and product drop o at the Food Hub.

Beyond being a guide for selling to the Food Hub, following these best practices enables farmers to sell practically anywhere else by following industry standards.

AW: What are some tips for farmers who haven’t sold wholesale before? Or best practices you see from farmers who currently sell with FDE?

JTC: Take pride in your product and maintain a high quality product. This is the only thing customers ever see from the farm and they may never get the chance to meet each farmer, so the face of your farm should be your product. Because of brand recognition, farmers with the highest quality products always have good sales even if they do not have much to sell that week.

AW: What products are always in demand? What do you wish more farmers had to offer?

JTC: Varieties of squash (zucchini, yellow squash, butternut, patty pan), kale (green, dino), lettuces/greens (buttercrunch, arugula, spinach, romaine), potatoes (sweet, gold, red, purple), and herbs (rosemary, oregano, basil, mint) are always in demand.

I wish farmers had a longer season for fruits (blueberries, blackberries, strawberries, watermelon, pears, peaches), cucumbers, and tomatoes. These items have very high demand when they are in season but the growing season for each is very short.

AW: Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers that I didn’t ask about? And, where are farmers you work with located?

Every food hub operates di erently and at FDE we only get the exact quantities of products that are sold each week. This changes weekly and is always subject to change. Farmers should explore all possible sales routes when deciding what to grow for each season. Diversify your sales opportunities by not only selling to food hubs but also at farmers markets, and if possible, by providing CSAs.

Feast Down East generally works with farms within 100 miles of our home base in Burgaw, NC, but we’ve been a little more exible recently with some farms that are closer to around 120 miles away. Some of it depends upon our isolated transportation infrastructure, with some farmers having to drive 10 or more miles to even get on a main road. Some of the farms farthest away are located in Durham, Raleigh, Kittrell, En eld, Jamesville, Maxton, Sanford, and Harlowe.

“Take pride in your product and maintain a high quality product.”

and sent out 13,318 acceleration letters, demanding that farmers pay their delinquent loans in full or prepare to face foreclosure.

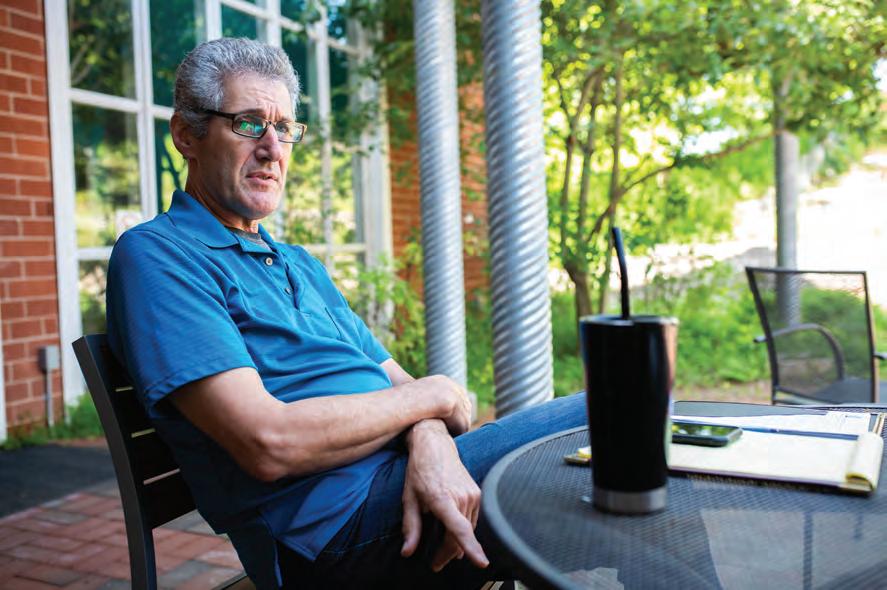

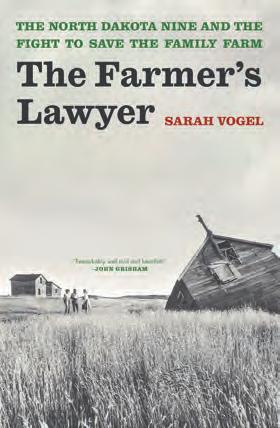

IF YOU WERE TO COMPILE A list of essential readings for farmers, farmer advocates, and people interested in agriculture, Sarah Vogel’s The Farmers Lawyer: The North Dakota Nine and the Fight to Save the Family Farm would top it. This true story of a young attorney and her lawsuit on behalf of farm families is many things: a compelling memoir; an important history lesson; a crash course in law; an epic David vs. Goliath struggle; and a warning for us all about the challenges farmers continue to face that threaten their very existence.

Sarah’s story begins in the early 1980s, with farmers suffering the worst economic crisis to hit rural U.S. since the Great Depression. Land prices were down, operating costs and interest rates were up, and severe weather devastated crops. Rather than assisting farmers, the newly elected Reagan Administration made a plan to push

them into foreclosure under the guise of dramatically reducing government spending. The Grand Doctrine, as it was known, was dreamed up by David Stockman, Reagan’s young director of the Office of Management and Budget. His goal: “abruptly severing the umbilical cords of dependence that ran from Washington to every nook and corner of the nation,” requiring “ruthless dispensation of short-run pain” to every corner of the federal budget — farm programs, nutrition and school lunch programs, legal services — in the name of future gain to the economy. Finding willing partners in John Block, Secretary of Agriculture, and Charles Shuman, National Administrator of Farmers Home Administration [(FmHA) known now as Farm Service Agency (FSA)], Stockman led the charge to eliminate farm loan delinquencies. By the end of 1981, FmHA had commenced 2,195 foreclosures

For folks who work with and support RAFI, The Farmer’s Lawyer is a glimpse into the critical work that RAFI’s farmer advocate, Benny Bunting, does every day. The roots of Benny’s work are deep in the ground of the 1980s Farm Crisis, when farmers rose up to save their farms and the farms of others, learning how to, as Sarah puts it, “help farmers and ranchers navigate the maze of FmHA rules and regulations.” Speaking of one such advocate who trained hundreds of others, Sarah says, “He knew FmHA regulations better than most FmHA employees did, and he freely shared his techniques and knowledge with other farmers.” The network of farmers and advocates like Benny who have such integral knowledge remains essential to farmers to this day.

Sarah’s case depended on these details, including knowing what rights farmers have in their dealings with FmHA, including the right to an appeal and the right to obtain the records FmHA keeps about you and your farm. As Benny can tell you, Sarah’s lawsuit challenging FmHA’s foreclosure processes in North Dakota, and eventually across the country as she won certification of more than 240,000 FmHA farm loan borrowers as a class for a class action lawsuit, is every bit as relevant today. To this day, farmers struggle to know their rights as farm borrowers, and to receive fair and equitable treatment. Sarah explains, “My main strength was naivete. I was a solo practitioner proposing a lawsuit against the U.S. government, which was rep-

resented by thousands of lawyers who fought hard and hated to lose. USDA was an ogre — big, mean and nasty. Yet I believed I could defeat it.”

Though she had trained to be a lawyer, Sarah came to the case much like the farmer advocates she mentions in her book: by necessity. Sarah was recruited by farmers who asked her to take up their case. Suffering from financial hardship and the imminent loss of their farms, they could not pay legal fees. Many of them bartered, offering carpentry services, eggs, and homemade jam in exchange for her representation. For Sarah, there was no option to say no; she had been raised in a household that ingrained in her the essential value of farmers. Sarah put her farmer plaintiffs first, forsaking her personal financial security and her discomfort with litigating a case in court — a thing she’d never planned to do.

Sarah’s legal argument relied on the decision in Goldberg v. Kelly, the U.S. Supreme Court case that had protected mothers receiving welfare benefits from being cut off from those benefits without a prior hearing. Sarah saw its precedent in the cases of the farmers she represented, who were cut off from their farm loans without a hearing, denied funds for food, electricity, feed for their animals, and other essential living and operating expenses. The brilliance of Sarah’s logic was in demonstrating that another suit, United States v. Kimbell Foods, Inc., showed that the court had previously found that FmHA’s loan programs were “a form of social welfare, primarily designed to assist farmers and businesses that cannot obtain funds from private lenders on reasonable terms.” In that decision,

the judge had written, “For qualified recipients, welfare provides the means to obtain essential food, clothing, house and medical care… [Thus] termination of aid pending resolution of a controversy over eligibility may deprive an eligible recipient of the very means by which to live while he waits.”

This ruling that FmHA’s program was a “social welfare” program, not merely a business enterprise of lending capital, recalled FmHA’s origins during the Great Depression as an organization with a mission to help struggling tenant and dispossessed farmers. They just hadn’t been practicing that way — until Sarah came along. In the final ruling of Coleman v. Block, Sarah’s lawsuit representing more than 240,000 farmers, the final permanent injunction stated:

“Before any liquidation, foreclosure, freeze of income, or similar action could be taken, FmHA had to provide at least thirty days’ written notice of its intentions to the farmer. This notice had

to tell the farmer that she or he had a right to a hearing and also had to give the reason for the proposed liquidation or termination.”

In the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987, Congress incorporated the provisions of the Coleman decision, including “due process, notice, fair hearings, and release of income — into the permanent law along with scores of other protections and safeguards,” effectively putting an end to the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. But as Sarah urgently warns in the preface, “I never thought that our present farm crisis would come as soon as the 2020s. There was a 50-year gap between the 1930s and 1980s farm crises, but this one is occurring on a much faster trajectory. Further, it seems likely that the farm crisis of the 2020s might be worse than its predecessors because it will coexist and overlap with climate change, hunger and food insecurity, unemployment, multiple federal, state, and local budget shortfalls, a ‘red state’ and ‘blue state’ political divide, and the economic and social aftershocks of the terrible world-wide COVID-19 pandemic.”

That makes The Farmer’s Lawyer a must-read for everyone who cares about food and farming. The paperback comes out September 19, 2023 with a preface from Willie Nelson, Farm Aid co-founder and president.

JENNIFER FAHEY joined Farm Aid in 2002 and serves as Communications Director, utilizing Farm Aid’s stage to share the stories of family farmers, farm advocates, and activists working to grow a farm and food system that benefits all of us. Though she’s never worked as a farmer, she used her first vacation at Farm Aid to volunteer on a Western Massachusetts farm for a week. It was one of the most rewarding, joyous, and challenging weeks of her life.

To this day, farmers struggle to know their rights as farm borrowers, and to receive fair and equitable treatment.

It is well known that many of the idioms or gures of speech that we use today are in large part due to the agricultural history of our country, as well as the animals we keep and care for. Come to the Table Program Director Justine Post asked the sta at RAFI to share their favorite farm-related expressions. Read them below; it won’t be a hard row to hoe!

This idiom holds a lot of meaning, but for Farm and Faith Partnerships Project Manager Jarred White, it is significant ”because it points to the idea that just as we are nurtured by a particular set of people, relationships, and communities, we should prioritize giving back to those same communities.”

When we asked Challenging Corporate Power Senior Program Manager Aaron Johnson if he had submitted this particular idiom without an explanation, he responded with “HOLD YOUR HORSES: I would never submit an idiom and ghost you. What a hill of beans … I’ll beat this dead horse insisting I did no such thing until the cows come home, so don’t go counting your chickens before they hatch!”

While many could credit Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca for this saying; it describes something of negligible importance. Farmer Resources Coordinator Otis Wright likes to use it because “you can apply it to different situations,” like when something makes no sense, or “if someone does something so stupid you can’t find the words!”

Just Foods Program Director Kelli Dale says that she uses this one a lot when she’s nearing the end of a task or project, as it refers to the last rows of the harvest. More than that, it reminds her of her father, as he uses the phrase frequently.

“That don’t amount to a hill of beans.”

“We’re on the short rows now.”

“Bloom whereplanted.”you’re

Giveaone-time donation.You’llbe helpingcreateamore fairfoodsystem. Pledgeamonthly donation.You’llsustain RAFI’sabilitytohelp farmersandtheir communitiesforyearsto come.

JoinRAFI’sPolicyAction Network.You’llreceive foodsystempolicy updates,actionalerts, socialmediaactivism guides,andtraining opportunities.

Your Support

MakesRAFI Stronger!

JoePellegrino