Perspective is now in its fourth edition which means that we’re now well into the swing of seeing a research lens in the minds of our students at Pymble Ladies’ College.

Publishing in Perspective is certainly a great achievement but students are learning that publication of a finished piece is only one part of the research process. Students are further building their research muscles by also presenting their work at the annual Pymble Student Research Conference and taking part in the Sokratis program (a year-long, co-curricular research opportunity co-led by the Pymble Institute and the College libraries).

What is exciting is that students are now seeing the power of interconnections and overlap. They’re starting to link these different research opportunities together; namely, conducting a Sokratis research project or doing a major work or research task for a course or class, with presenting their findings at the conference and then writing it up for publication. They are learning how to maximise these efforts and deepen their understanding of the research process by sticking with the journey of research through a range of twists and turns.

This is giving Pymble students a powerful perspective on research as they appreciate the value of commitment to ideas which just don’t go away- and don’t need to! Dedication to pursuing an idea through research is an attribute we aim to cultivate in the Pymble Institute. This edition brings to readers twenty four articles, representing the scholarship of twenty six students. The topics are themselves worthy of research as they provide an annual snapshot of what matters for young people today.

In this edition, we welcome the inclusion of HSC Major Works from Society and Culture, as well as History and Science Extension through papers from Tess, Nupur, Isla, Lucy and Sumeera. The importance of humans and their environments and communities is explored by Carrie, Victoria, Lauren, Megan and Maya in papers written for their Senior Geography Projects and Elective Geography courses. Course work in History and English inspired Catherine, Chloe, June and Paanya, and the National History Challenge provided an excellent opportunity for Amy, Lauren, Elizabeth, Jenny and Joy to explore Australia’s past, present and future. Perspective also offers an opportunity to capture the elusive nature of speeches, as seen with Evelyn and Aliya’s papers. Outstanding winners of the Pens Against Poverty primary school writing competition, Chloe, Chloé and Charlotte, are given a wider audience

through their publication in Perspective. In the Science area, budding researchers Evelyn, Leahara and Yuki share findings emerging from their own investigations.

Once again, we commend and thank Julie for her generous leadership of the Perspective Student Editors Group. Julie has a gift for drawing others towards her and inviting more students to get involved –this is ideal for building a research culture. We also recognise the talents of Ang-Ya who managed all the submissions and Sophia who designed the cover. The student editors worked as a positive, supportive and productive team and deserve to be very proud of their commitment. Congratulations to Anisha, Ayana, Aysel, Caiyi, Catherine, Erika, Helena and Maya! Thank you also to Ms Rachel Fairbairn and Mr Bray Stoneham from the Community Engagement team for making Perspective come to life each edition.

We hope readers enjoy their journey through these young researchers’ investigations and find much benefit in hearing about the myriad of perspectives which are important to students of Pymble Ladies’ College.

DR SARAH LOCH DIRECTOR – PYMBLE INSTITUTEWhen I was in Year 9, my History class learnt about the eugenics theories of Nazi Germany. I was disgusted by the sheer cruelty, by the blatant bastardization of research, by the corruption of something that gave us penicillin into something that condemned millions of innocent people to death. But sadly, as I later discovered, WWII was not the first or the last time a vile crime like this occurred. From the Tuskegee study in America to the Aversion Project in South Africa, our past is riddled with instances where research was used for evil, to the detriment of entire communities.

It is harrowing to think about. Research can build trust. Research can unite people. Research can draw attention to issues that have remained silent before, but it can also silence issues that deserve to be advocated for. Research has power, but how this power is wielded is up to us.

In our age of digital news and online forums, the power of research grows more and more with each mind it touches. And when it is abused, misinformation, oppression, and tragedy will inevitably ensue.

So here at Pymble, our focus is on using research for good. Our mission is to harness research as a tool that drives positive change and social equality. The College is in the influential position of imparting a rich education to a great number of bright minds, and as such, it also has the responsibility of ensuring that its students mature into not only intelligent

and capable women, but leaders who care about changing their community for the better.

This responsibility is fulfilled year after year, and 2023 was no exception. After reading the diverse and nuanced research produced by the Pymble student authors, I believe it is safe to say that the future of research is in good hands.

Each piece of work has been carefully crafted, with a distinct voice, and a strong underlying current of social awareness. There is research that exposes injustice, research that gives a fresh perspective, research that confronts and research that subverts. Our students are young, but they are also keenly insightful, with passion that propels them to think more, to learn more, and to do more.

Crucially, they are also willing to share. Research that remains locked in the mind of one person has no potential to affect society as a whole. But research spread on the lips of two people, ten people, hundreds and thousands and millions of people, has this potential. The courage that all the contributors to this 2023 edition of our journal have exhibited in stepping forward and sharing their knowledge is also the courage that the world needs if we want it to be a better place.

Hence, I would like to express my sincere thank you to the authors of the research works we have proudly showcased in Perspective this year. They deserve to feel great pride at the painstaking effort

they have invested in their research and the high quality work they have perfected in detail. Years later, some of these talented researchers may pursue a distinguished career in academia, or politics, or finance. But regardless of where they choose to take their journeys, their respect for the power of research will always stay with them, and because of that, I am sure that they will be able to use their influence for good.

My gratitude also extends to my fellow student editors. This year marks the second time that students served on the Perspective editorial team, and our group, with students from Years 7 to 12, accomplished the task wonderfully, with efficiency, verve, and exuberance. The section editors are:

Literature and Philosophy

Chengjia (Julie)

Ayana

Catherine

Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics

Yuki

Caiyi

Ang-Ya

History and Politics

Helena

Maya

Erika

Geography, Business, Economics

Jiya

Sophia

Anisha

Philosophy and Ethics

Aysel

Ariana

But we did not do it alone. The Editorial Team is deeply indebted to Dr Loch, the head of the Pymble Institute, who has given up her precious time to oversee the editorial process of this Journal. Her guidance, humility and warmth has led us along this rewarding journey. Dr Loch, one of the first educators to unlatch the gates of academia for high school students, has opened our eyes and fostered our growth. Under her leadership, Pymble students flourish and immerse themselves completely in the tantalizing world of research.

Finally, on behalf of the Perspective Editorial Committee, I would like to thank you, dear reader, for your interest and support of Pymble’s unique and vibrant research culture. I hope you enjoy this edition and are inspired to undertake your own research for good.

Cheers,

JULIE SHENG LEADER OF THE PERSPECTIVE STUDENT EDITORIAL TEAMThis paper was written for Year 12 Science Extension

ABSTRACT

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels when exceeding 1000ppm are known to cause fatigue, headaches, and poor focus. A study conducted across a year in Victoria found that on average urban classrooms exceeded the established threshold of 1000ppm in 85% of cases. The study investigated the relationship between CO2 levels within high school science classrooms at Pymble Ladies’ College and the reduction resultant from the implementation of a 115mm Syngonium podophyllum. Plants are known to reduce CO2 levels within sealed chambers as first established in 1960, this is not investigated satisfactorily when extended to larger environments with conflicting results being proposed and no clear recommendations, guidelines or implementation potential being recognised. Further investigation was therefore advised as to whether it provided a feasible way in which CO2 levels within classrooms could be reduced. The study was conducted across a 4-week period with a 2-week base level recording and 2-week intervention implementation period. There were 4 observed classrooms with 1 acting as a temporal control throughout the trial. The study found reductions of CO2 in all cases of implementation and no significant variation in CO2 levels within the controlled classroom across the experimental period. The average CO2 reduction when S. podophyllum was implemented was 37.1%. This aligned with known knowledge and performance of S. podophyllum within modelled ideal chambers. The significance of the findings could result in the implementation of plants to reduce CO2 levels within school environments. However, prior to guideline implementation further investigation without time, cost and space restrictions would enable greater specification regarding species and plant to student ratios requirements.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Exposure to high levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) is known to be associated with a range of health effects ranging from slight drowsiness to high shortness of breath. When CO2 levels exceed 1000 parts per million (ppm), drowsiness is reported, and when excess of 2000 ppm, sleepiness, headaches, increased heart rate, loss of attention, and nausea may become present (MN Dept. Of Health, 2022.). It is further indicated that CO2 levels exceeding 1000 ppm can cause poor decision making when compared to decisions made at 600 ppm (Satish et al., 2012). The negative impact of CO2 on human health

within an indoor environment has been recognised since 1960 (Wittlin, 1960).

Negative impacts of high CO2 levels within classrooms were identified in 1996 with a Norwegian investigation finding “correlations of reduced pupils’ performance and increased CO2 levels” (Myhrvold et al, 1996). The longstanding recognition of negative impact has not led to the development or enforcement of international guidelines. Current guidelines within New South Wales (NSW) for classroom ventilation are specified as ventilation of 10 litres per person, per second (Department of Education, 2023). Further Australian building codes state that the level of CO2 across an 8 hour period should not exceed 850ppm (ABCB, 2022). This level is known to be exceeded within school classrooms (Hanmer, 2021) with a Victorian study indicating that all indoor environments with inadequate ventilation and high usage rates are likely to experience CO2 rates which exceed recommendation guidelines (Andamon et al., 2023).

Air ventilation systems utilise an average of 120 kilowatt hours accounting for up to 39% of office energy usage (HVAC HESS, 2013). With institutional requirements to progress towards net zero and reduce energy usage other mechanisms for CO2 reduction are recommended for investigation (Sadrizadeh et al.,2022) as to whether they are feasible to use in the place of traditional ventilation technology.

One mechanism feasible for investigation is the implementation of plants capable of photosynthesis. The process of photosynthesis utilising CO2 and being understood at a molecular level was published in 1960 (Stirbet et al., 2019). This process indicates that the plant leaves photosynthesise, absorbing CO2 and H2O, and then oxidation occurs, forming glucose and oxygen. The production of glucose allows for growth within plants as CO2, once converted into glucose, forms chains of cellulose, resulting in more CO2 being stored than is respired during respiration. This indicates that a plant with a greater growth rate will be more effective at eliminating CO2 from the environment. S. podophyllum is known to be effective at reducing indoor atmospheric CO2, with one study finding that this reduction occurred at 10.08% (Suhaimi, Leman, & Safii, 2016).

It is clearly established that plants can have a beneficial impact on the reduction of CO2. A Swedish study within

an ideal sealed chamber investigated the effectiveness of plants to reduce CO2 levels. The study found that “a combination of plants, as in this report, resulted in lower particulate matter and lower CO2 levels” (Claudio, 2011). Therefore, making it clear that the benefits of indoor plants being abundant in highly used indoor environments should be thoroughly investigated. The recognised requirement to reduce CO2 levels within indoor environments to prevent the negative health effects and comply with Australian guidelines indicates the need to investigate alternate mechanisms for CO2 reduction.

Is there a correlation between introducing a S. podophyllum of base diameter 150mm into a Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom and recorded level of CO2 ppm 1 metre away from the plant?

Within an ideal sealed chamber, S. podophyllum reduces CO2 levels by 10.08%. Therefore, it is suggested that this will extend to an indoor classroom environment which is known to have a high concentration of CO2 will have a decrease in CO2 when a S. podophyllum is introduced to the classroom.

A 150mm S. podophyllum plant was introduced to the classroom. S. podophyllum is a commonly found plant which is seen to be effective at removing CO2 from indoor atmospheres within modelled trials.

To monitor CO2 levels within the classroom an Arduino MQ-135 sensor was utilised. The sensor records atmospheric levels of CO2 at 10-minute intervals throughout the trial period. The measurements were recorded within a Comma-separated values (CSV) file with both a timestamp and value reading.

The classrooms were constructed in 1994 of a double brick material. They are located on the bottom floor of the building with S9, S10 and S11 having 2 external doors and north facing windows. S12 has 1 external door and southeast facing windows, additionally the windows within S12 open onto an area of trees and other low foliage. Each classroom has an area of 62.08m2 and an average number of 20 students per lesson. The internal construction material consists of a laminate floor and 21m2 area of carpet. The internal construction, layout and usage of the classrooms is the same. The 4 selected classrooms are utilised for junior science and senior biology, selected due to the lack of chemical usage and uniformity of the classrooms.

The monitoring cycle consisted of a continuous 4-week period in which measurements were taken at 10-minute intervals throughout. The sensor remained in the same

The classrooms were constructed in 1994 of a double brick material. bottom floor of the building with S9, S10 and S11 having 2 windows. S12 has 1 external door and southeast facing windows, within S12 open onto an area of trees and other low foliage. 62.08m2 and an average number of 20 students per lesson. The consists of a laminate floor and 21m2 area of carpet. The internal of the classrooms is the same. The 4 selected classrooms are senior biology, selected due to the lack of chemical usage and

position throughout the 4 weeks with the plant being introduced for the second 2 weeks positioned exactly 1 metre from the sensor. The time period was selected as it allowed for the same 2-week student timetable to occur both with and without a plant. This controlled the activities and usage levels of the classrooms throughout the experiment period.

The classrooms were constructed in 1994 of a double brick material. bottom floor of the building with S9, S10 and S11 having 2 external windows. S12 has 1 external door and southeast facing windows, within S12 open onto an area of trees and other low foliage. Each 62.08m2 and an average number of 20 students per lesson. The consists of a laminate floor and 21m2 area of carpet. The internal of the classrooms is the same. The 4 selected classrooms are senior biology, selected due to the lack of chemical usage and uniformity

The monitoring cycle consisted of a continuous 4-week period taken at 10-minute intervals throughout. The sensor remained the 4 weeks with the plant being introduced for the second 2 weeks from the sensor. The time period was selected as it allowed timetable to occur both with and without a plant. This controlled of the classrooms throughout the experiment period.

The plant was positioned on the back bench away from student desks and lab desks to prevent interference with the plant. At the conclusion of the first 2-week monitoring cycle, a 150mm S. podophyllum plant was introduced to the classroom positioned 1 metre from the sensor and watered bidaily.

The monitoring cycle consisted of a continuous 4-week period taken at 10-minute intervals throughout. The sensor remained in the 4 weeks with the plant being introduced for the second 2 weeks from the sensor. The time period was selected as it allowed timetable to occur both with and without a plant. This controlled of the classrooms throughout the experiment period.

The plant was positioned on the back bench away from student interference with the plant. At the conclusion of the first 2-week podophyllum plant was introduced to the classroom positioned watered bidaily.

The plant was positioned on the back bench away from student interference with the plant. At the conclusion of the first 2-week podophyllum plant was introduced to the classroom positioned watered bidaily.

Across the 4-week period weather conditions and classroom temperatures understand fluctuations within the uncontrolled variables.

Across the 4-week period weather conditions and classroom temperatures were tracked to understand fluctuations within the uncontrolled variables. The distribution of CO2 is assumed as approximately normal, the data is continuous, and the data is randomly sampled. As the data is not of equal variance the appropriate statistical measure was a t-test for two values of unequal variance. The t-test was conducted between the control period and implementation period. To test for the null hypothesis of no change in CO2 levels between periods tested for a confidence level of 95% and the critical alpha value was established as 0.05.

Across the 4-week period weather conditions and classroom temperatures understand fluctuations within the uncontrolled variables.

The distribution of CO2 is assumed as approximately normal, data is randomly sampled. As the data is not of equal variance the was a t-test for two values of unequal variance. The t-test was period and implementation period. To test for the null hypothes levels between periods tested for a confidence level of 95% and established as 0.05.

The distribution of CO2 is assumed as approximately normal, the data is randomly sampled. As the data is not of equal variance the was a t-test for two values of unequal variance. The t-test was conducted period and implementation period. To test for the null hypothesis levels between periods tested for a confidence level of 95% and established as 0.05.

Figure 1: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S9. Continuously across the 4-week period with no implementation of a plant. This enabled the classroom to act as a temporal control. This measuring from environmental changes between the time periods. The P value of p=0.073 shows no significant change between the two time periods.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science the 4-week period with no implementation of a plant. This enabled the This measuring from environmental changes between the time periods. significant change between the two time periods.

Figure 1: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College the 4-week period with no implementation of a plant. This enabled This measuring from environmental changes between the time periods. significant change between the two time periods. FIGURE 2

Figure 2: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S10 is represented within Figure 2. It is a graphical comparison between the time cycle without and with a plant. The mean for the time with no plant was 796.78ppm whilst it was

FIGURE 2

Figure 2: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science

Figure 2: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College

Figure 2. It is a graphical comparison between the time cycle without with no plant was 796.78ppm whilst it was 514.58ppm within the cycle when a plant was introduced is 48.7%. The time cycles were t-tested variance and has a t stat of 89.59 and p value of p<9.96E-281 which

Figure 2. It is a graphical comparison between the time cycle without with no plant was 796.78ppm whilst it was 514.58ppm within the cycle when a plant was introduced is 48.7%. The time cycles were t-tested variance and has a t stat of 89.59 and p value of p<9.96E-281 which

Figure 2: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S10 is represented within Figure 2. It is a graphical comparison between the time cycle without and with a plant. The mean for the time with no plant was 796.78ppm whilst it was 514.58ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 48.7%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance and has a t stat of 89.59 and p value of p<9.96E-281 which can be considered significant.

514.58ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 48.7%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance and has a t stat of 89.59 and p value of p<9.96E-281 which can be considered significant.

Figure 2: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S10 is represented within Figure 2. It is a graphical comparison between the time cycle without and with a plant. The mean for the time with no plant was 796.78ppm whilst it was 514.58ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 48.7%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance and has a t stat of 89.59 and p value of p<9.96E-281 which can be considered significant. FIGURE 3

Figure 3:

concentration

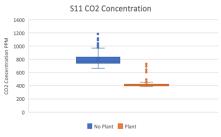

Ladies’ College science classroom S11 is represented within Figure 3. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 790.51ppm whilst it was 418.21ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 47.1%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 77.46 and P value of 0.

both throughout the control and plant implementation. The plant intervention did however still further reduce the CO2 levels within the classroom.

FIGURE 3

The weather throughout the trial period was seen to impact classroom CO2 levels as days with colder temperatures were seen to have higher CO2 concentrations within the classroom. This did not impact the results analysis as the trend was observable across all classrooms including the control and the average CO2 level was not altered throughout these conditions. It is however an observation which can advise guidelines regarding classroom conditions on cooler or wet days as these days the CO2 levels were seen to exceed 1000 ppm.

Figure 3: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S11 is represented within Figure 3. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 790.51ppm whilst it was 418.21ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 47.1%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 77.46 and P value of 0.

4:

The results of the investigation indicate with strong evidence that introducing a plant to a classroom reduces CO2 levels. This is desirable within classrooms as lower CO2 levels reduce fatigue and increase concentration. Study results mean that recommendations can be made that plants should be introduced to high school science classrooms. These recommendations should dictate that any classroom without direct window to plants should have a plant within them. This recommendation can be based on the knowledge that when classrooms do not back directly onto foliage, they exceed the 1000 ppm CO2 safety limit and therefore should be required to have at least one plant within. Further investigation into specific foliage amounts and species type to include within recommendation is advised.

Figure 3: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S11 is represented within Figure 3. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 790.51ppm whilst it was 418.21ppm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 47.1%. The time cycles were t-tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 77.46 and P value of 0.

Figure 4: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S12 is represented within Figure 4. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 270.72ppm whilst it was 227.77pm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 15.84%. The time cycles were tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 79.96 and P value of 0.

Discussion

Discussion

College science classroom S12 is represented within Figure 4. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 270.72ppm whilst it was 227.77pm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 15.84%. The time cycles were tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 79.96 and P value of 0.

Figure 4: The CO2 concentration from the Pymble Ladies’ College science classroom S12 is represented within Figure 4. It is a graphical comparison between the cycle without a plant and cycle within a plant within the classroom. The mean for the time with no plant was 270.72ppm whilst it was 227.77pm within the cycle with a plant. The percentage decrease when a plant was introduced is 15.84%. The time cycles were tested for two samples assuming unequal variance has a t stat of 79.96 and P value of 0.

The known model of S. podophyllum performance when reducing CO2 levels within indoor atmospheres supports the investigation findings. The previous studies which utilised models of controlled CO2 levels reported reduced performance in comparison to that observed within the investigation. The most likely cause for this observation is the influence of foliage area. The plant utilised within this investigation had a base radius 15mm greater than that within the sealed chamber trial and there was a greater initial level of CO2 within the environment.

A decrease in CO2 levels was observed for all classrooms with S. podophyllum introduced was observed, the average decrease was 37.1% This reduction was observed across 3 classrooms and was not explained through other environmental changes.

A decrease in CO2 levels was observed for all classrooms with S. podophyllum introduced was observed, the average decrease was 37.1% This reduction was observed across 3 classrooms and was not explained through other environmental changes.

The variation across the classrooms included changed ventilation conditions, orientations, and usages. The variation in classroom conditions allowed for testing across various environments and therefore application to broader school usages for reduction in CO2. The south facing classroom with large amounts of foliage directly outside the classroom had the lowest recorded CO2 levels both throughout the control and plant implementation. The plant intervention did however still further reduce the CO2 levels within the classroom.

METHODOLOGY

The variation across the classrooms included changed ventilation conditions, orientations, and usages. The variation in classroom conditions allowed for testing across various environments and therefore application to broader school usages for reduction in CO2. The south facing classroom with large amounts of foliage directly outside the classroom had the lowest recorded CO2 levels both throughout the control and plant implementation. The plant intervention did however still further reduce the CO2 levels within the classroom.

A decrease in CO2 levels was observed for all classrooms with S. podophyllum introduced was observed, the average decrease was 37.1%. This reduction was observed across 3 classrooms and was not explained through other environmental changes.

The weather throughout the trial period was seen to impact classroom CO2 levels as days with colder temperatures were seen to have higher CO2 concentrations within the classroom. This did not impact the results analysis as the trend was observable across all classrooms including the control and the average CO2 level was not altered throughout these conditions. It is however an observation which can advise guidelines regarding classroom conditions on cooler or wet days as these days the CO2 levels were seen to exceed 1000 ppm.

The weather throughout the trial period was seen to impact classroom CO2 levels as days with colder temperatures were seen to have higher CO2 concentrations within the classroom. This did not impact the results analysis as the trend was observable across all classrooms including the control and the average CO2 level was not altered throughout these conditions. It is however an observation which can advise guidelines regarding classroom conditions on cooler or wet days as these days the CO2 levels were seen to exceed 1000 ppm.

The results of the investigation indicate with strong evidence that introducing a plant to a classroom reduces CO2 levels. This is desirable within classrooms as lower CO2 levels reduce fatigue and increase concentration.

The results of the investigation indicate with strong evidence that introducing a plant to a classroom reduces CO2 levels. This is desirable within classrooms as lower CO2 levels reduce fatigue and increase concentration.

Study results mean that recommendations can be made that plants should be introduced to high school science classrooms. These recommendations should dictate that any classroom without direct window to plants should have a plant within them. This recommendation can be based on the knowledge that when classrooms do not back directly onto foliage, they exceed the 1000 ppm CO2 safety limit and therefore should be required to have at least one plant within. Further investigation into specific foliage amounts and species type to include within recommendation is advised.

The variation across the classrooms included changed ventilation conditions, orientations, and usages. The variation in classroom conditions allowed for testing across various environments and therefore application to broader school usages for reduction in CO2. The south facing classroom with large amounts of foliage directly outside the classroom had the lowest recorded CO2 levels

Study results mean that recommendations can be made that plants should be introduced to high school science classrooms. These recommendations should dictate that any classroom without direct window to plants should have a plant within them. This recommendation can be based on the knowledge that when classrooms do not back directly onto foliage, they exceed the 1000 ppm CO2 safety limit and therefore should be required to have at least one plant within. Further investigation into specific foliage amounts and species type to include within recommendation is advised.

Further the effect of CO2 reduction was only observed during daylight hours. This is supported by known evidence of how photosynthesis occurs and supports the use of plants within classrooms to reduce CO2 levels as classrooms are only used throughout daylight hours. The increased CO2 concentration was related significantly to the classroom which observation occurred in. The classrooms which were North facing and received sunlight had significantly higher average levels of CO2 than those with poorer lighting. To further investigate this relationship and the degree of impact that plants can have in well-lit classrooms the experiment should be repeated across a broader range of rooms.

Classroom carbon dioxide levels did not vary depending on classroom usage. This observation may mean that

The known model of S. podophyllum performance when reducing CO2 levels within indoor atmospheres supports the investigation findings. The previous studies which utilised models of controlled CO2 levels

The known model of S. podophyllum performance when reducing CO2 levels within indoor atmospheres supports the investigation findings. The previous studies which utilised models of controlled CO2 levels

built up carbon dioxide does not decrease at a rate related to time of use. This could alternatively be related to the effectiveness of plants removing carbon dioxide from a classroom at a greater rate during the day than during the night. This pattern would be aligned with known requirements for CO2 removal aligned with photosynthesis.

Limitations within the investigation include the restricted number of trial classrooms and length of study. Additionally, the lack of control across the classrooms ventilation and usage provides a limitation in determination of causality. The correlation observed across the three classrooms is directly observed in Pymble Ladies’ College science classrooms.

Further limitations include the lack of diversity in species and lack of variation in foliage amounts. The lack of variation means the study conclusions can only extend for S. podophyllum to reduce CO2 levels within 1 metre of the plant.

Investigation into the radius of impact surrounding the plant, application across different types of classrooms and reportable effects from those who partake in classes which contain a plant would provide greater evidence for guidelines and recommendations to be introduced across all classroom types.

Australian Building Codes Board. (2022). Handbook: Indoor air quality Indoor Air Quality.

Andamon, M. M., Rajagopalan, P., & Woo, J. (2023). Evaluation of ventilation in Australian school classrooms using long-term indoor CO2 concentration measurements. Building and Environment, 237, 110313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110313

Burchett, M. (2014, April 14). How humble houseplants can improve your health. University of Technology Sydney. www.uts.edu.au/ about/faculty-science/partners-and-community/uts-science-focus/ medical-and-biomedical-sciences/how-humble-houseplants-canimprove-your-health

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)—MN Dept. Of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved August 24, 2023, from https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/air/toxins/co2.html

Claudio, L. (2011). Planting Healthier Indoor Air. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(10), a426–a427. https://doi.org/10.1289/ ehp.119-a426

Communication and Engagement, (2023, April 27). Ventilation. NSW Department of Education.

Hanmer, G. (2021, November 8). Schools need to know classrooms’ air quality. University of Technology Sydney. https://www.uts.edu.au/ news/health-science/schools-need-know classrooms-air-quality

Hashim, N. H., Teh, E. J., & Rosli, M. A. (2019). A dynamic botanical air purifier (DBAP) with activated carbon root-bed for reducing indoor carbon dioxide levels. IOP Conference Series: Earth and

With further funding and removal of time constraints a more robust 6-month study is recommended to allow for greater determination of research implications. The study should be conducted across classrooms of different uses, construction types and locations across New South Wales. This would inform the broader use of S. podophyllum for CO2 reduction within both primary and high school classrooms part of the NSW Department of Education.

To provide clear guidelines for plant implementation investigation into species type and optimal foliage area would provide clear guidelines for the best plant for implementation and optimising financial usage.

The null hypothesis can be rejected with it being established with a certainty of >99.9% that when a S. podophyllum is introduced into a Pymble Ladies’ College science room there is a decrease in CO2. This finding additionally supports the hypothesis from the modelled performance of the plant in an ideal chamber that the S. podophyllum plant will reduce CO2 by 10.08%. The average rate of reduction was observed as 37.1% with no change observed within the same period in the control classroom.

Environmental Science, 373(1), 012022. https://doi.org/10.1088/17551315/373/1/012022

HVAC HESS. (2013). HVAC factsheet—Energy breakdown | energy.gov. au. https://www.energy.gov.au/publications/hvac-factsheet-energy-breakdown

Myhrvold et al, (1996). Indoor environment in schools—Pupils health and performance in regard to CO2 concentrations. https://www.aivc. org/resource/indoor-environment schools-pupils-health-and-performance-regard-co2-concentrations

Rasoulinezhad, E., Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., & Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2020). How Is Mortality Affected by Fossil Fuel Consumption, CO2 Emissions and Economic Factors in CIS Region? Energies, 13(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13092255

Sadrizadeh, S., Yao, R., Yuan, F., Awbi, H., Bahnfleth, W., Bi, Y., Cao, G., Croitoru, C., de Dear, R., Haghighat, F., Kumar, P., Malayeri, M., Nasiri, F., Ruud, M., Sadeghian, P., Wargocki, P., Xiong, J., Yu, W., & Li, B. (2022). Indoor air quality and health in schools: A critical review for developing the roadmap for the future school environment. Journal of Building Engineering, 57, 104908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2022.104908

Satish, U., Mendell, M. J., Shekhar, K., Hotchi, T., Sullivan, D., Streufert, S., & Fisk, W. J. (2012). Is CO2 an Indoor Pollutant? Direct Effects of Low-to-Moderate CO2 Concentrations on Human Decision-Making Performance. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(12), 1671–1677. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104789

Stirbet, A., Lazár, D., Guo, Y., & Govindjee, G. (2019). Photosynthesis: Basics, history and modelling. Annals of Botany, 126(4), 511–537.

INVESTIGATION OF IMPACT SYNGONIUM PODOPHYLLUM HAS ON CARBON DIOXIDE CONCENTRATION IN HIGHSCHOOL SCIENCE CLASSROOMS

https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcz171

Wittlin, E. (1960). Self-Emitted Breath in Indoor Environment. Journal of the National Medical Association, 52(5), 329–330.

Woo Jin, Andamon Mary Myla, Rajagopalan Priya. (n.d.). Indoor Air Quality for Vulnerable Population—A Climate Change Innovation

Grant. Retrieved August 24, 2023, from https://www.rmit.edu.au/ about/schools-colleges/property-construction-and-project management/research/research-centres-and-groups/sustainable-building-innovation laboratory/projects/climate-change-innovation-grant

This paper was written for Year 12 Science Extension

ABSTRACT

The study aims to determine whether the shift in user experience in phones, from colour to black and white, reduces screentime in adolescents. The screentime of adolescents has become an increasingly prominent issue. The study investigated the use of greyscale on people aged 16 to 18 comparing individuals’ average screentime using both colour and greyscale over consecutive weeks. This methodology determined the results, which show no statistical difference in screentime, between the weeks, due to uncontrolled factors such as examination blocks. The study did, however, find some impact of greyscale.

LITERATURE REVIEW

As technology advances and phones become more prominent along with addictions, the importance of maintaining balance with how stimulating it can be is becoming increasingly important. A psychological study done by Burst (2021) found that colour impacts people’s emotional response and behaviour in marketing, which can be applied to the manufacturing of phones. They identified that grey symbolises ‘old age and solidarity’ and also found in some marketing schemes such as ‘Lexus’s use of light grey’, invokes a feeling of luxury as well as elegance and maturity. Unlike other colours, grey shows less emotional response. Furthermore, the effect of colour on the brain in Korkmaz, Özer (2016) inaugurated study that different colour formed different neural responses, through their analysis of brain activity using MEG. This develops new possible hypotheses into the impact of colour within the brain.

In addition, Haynes’ (2018) investigation found dopamine was released in response to stimulus such as colour. They identified the mesolimbic pathways developed pleasure and reward systems from behaviours such as addictions, emotions, and perception, which can arise from phone usage. The two factors which contribute to addiction include the re-enforcement and neuroadaptations to modulated behaviours, which is constructed through stimulus Roberts, A.J., Koob, G. F (1997). Constant consumption being withdrawn in addictions to drugs resulted in elevated heart-rates and blood pressure, as well as changes in mental state leading to anxiety, depression, and cravings for the stimulus. This can be engaged to the constant consumption of digital media in phones, which acts as a stimulus to mesabolic receptors in the neurotransmissions within the individual.

A further look into reducing screentime of smartphones

in teenagers becoming more necessary to help create more a more balanced life with less reliance on phone usage was done by Clayton, et al. (2015.) The study found that phone separation strongly affects the psychological wellbeing of individuals, and the inability to use phones can also affect physical wellbeing. In their investigation, when unable to answer notifications, people experienced increased blood pressure and heart rates, which led to feelings of anxiety. These symptoms are comparable with Roberts, A.J., Koob, G. F (1997) study of withdrawal from constant consumption of stimulus, being drugs in their study and phones in Clayton et al. (2015).

The implementation of controls on Apple devices that came with the 2018 software update IOS12, in order to help manage screentime, demonstrating the concern for addictions in young people and adolescents (2018), suggests ‘Screen Time is great for everyone to better understand and manage their device usage but can be especially helpful for kids and families’, clearly demonstrating the need for young people to reduce the amount of time on devices. Furthermore, a study by Stiglic N, Viner RM (2019) found evidence surrounding high levels of screentime being associated in CYP (children and young people) with variety of health harms including ‘adiposity, unhealthy diet, depressive symptoms and quality of life’. The evidence further found ‘moderate evidence for an association of screentime with lower HRQOL (Health Related Quality Of Life), with weak evidence for a threshold of >2 hours daily screentime’, indicating the importance of developing methodologies in limiting screentime in CYP, to maintain a healthy quality of life in psychological and physical aspects.

Furthermore, a study conducted by Lundqvist and Ljungblad (2019) developed a guideline methodology, finding the enticement of colour on phones and contrast of greyscale can affect screentime, with regards to user experience in Instagram and Facebook. Their data was limited during their investigation due to a short time frame and small sample size of 10 people. They further used adults, leaving room for research into the effects within adolescents. The initial hypothesis, ‘If you use greyscale, rather than colour, the amount of screen time will be reduced in 16 to 18-year-olds’, is increasingly pertinent in the field of research. Using greyscale to reduce phone usage has the potential for developing ways to help CYP experiencing mental health related issues from phone usage. This, therefore, shows the need for additional research, as technology develops.

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH QUESTION

How does changing phones to greyscale, impact the amount of screen-time used by people aged 16 to 18 help to reduce screen time?

SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESIS

If you use greyscale on phones, rather than normal colour, the amount of screen time will be reduced.

METHODOLOGY

The study utilised a controlled sample of individuals aged 16 to 18 who were enrolled in high school. To gather participants within the age range, the Heads of Year for 11 and 12 at Pymble Ladies College (PLC) distributed an email, detailing a broad understanding of the experiment and a link to a Google form where individuals volunteered their interest in participation. The link was also distributed to multiple social media (Instagram and Snapchat) to find a variety of individuals. The form was revised, leaving 59 initial participants out of the 64, who expressed a desire to take part in the investigation.

Each individual who expressed interest was informed one week prior to the beginning of the experiment the requirements of the study via emails provided in the Google form. Participants were required over a period of two weeks during 14/5/2023 to 21/5/2023 in week one and 21/5/2023 to 27/5/2023 in week two. The first week acted as a control, in which their settings were unchanged. The second week applied the greyscale setting, allowing for a comparison between the screentime usage of each day and overall average phone usage. The weeks were intentionally selected to occur during the school term, to provide a control for the individuals’ daily schedules from the hours of roughly 8am to 3pm. The participants were responsible for uploading their daily screentime to an individual Google folder. They were emailed over the two weeks, with reminders and encouragement. The data collected was converted from the individuals’ screenshots using the formula, xhr × 60 + xmin and collated into an Excel spreadsheet.

On the last day of the two-week period [27/5/2023], the participants were provided with a secondary Google form to reflect on their individual experience in using greyscale. After four days following the completion of the experiment, those who had not uploaded their complete data set were removed from the raw data which resulted in a total of 32 participants. The secondary Google form was then adjusted to accept only answers from the 32 participants, leaving 26 final responses. The data sets were then visualised using Excel.

The average from the 32 participants was visualised using Excel and used to create t-tests; paired for two sample means designating the alpha value as the critical value comparing the daily data from each day of the week to show the comparison.

32 final participants’ data was averaged for both weeks and put into a statistical t-Test: Paired for Two Sample Means. The t-Test (Table 1) has an alpha value of 0.05. The p-value one-tail is 0.38, which is higher than the alpha value and has no statistical difference. The two-tailed p-value is 0.77 which is higher than the alpha value and displays no statistical difference.

Table 1: t-Test comparing the daily average of week 1, variable 1 and week 2, variable 2.

The null hypothesis ‘there is no difference between greyscale and colour in screentime’ is failed to be rejected due to the p-values affirming no statistical difference.

Figure 1: Comparison of the weekly screentime average between colour and greyscale

Figure 1 further affirms the null hypothesis as there is a high similarity in the medians with a 0.43 difference. The standard deviation shows extreme similarities in the skew of the data. The only distinct variation shown on the box plot is the outlier during the normal colour, showing there was a decrease of an individual’s screentime. Therefore, there was no distinction in the deviation of data, and no relevant statistical difference.

Figure 2: Follow up survey from final responses - scale of feeling throughout the duration of the experiment.

The follow up survey (Figure 2) determined that the experience of individuals using greyscale was moderately, negatively skewed, identifying a greater sense of boredom rather than productivity, with a mode of three.

Figure 3: Follow up survey from final responsespie chart of activities completed in replacement of screentime

The survey found (Figure 3) that 36% of individuals were going to sleep earlier, when experiencing boredom from their phone, providing correlation between the impact of greyscale on daily life.

Figure 4: Follow up survey from final responses - scale of how much participants felt their screentime was reduced

The survey found that individuals felt screentime

reduction was minimally felt, with a mode of two and a decreasing skew (Figure 4).

The investigation being conducted as a quasi-experiment allowed for the selection of the participants to be within the specific ‘16 to 18’ age range to achieve moderate internal validity. The age range beginning at 16 meant participants did not require parental consent. Participants were made aware of what the experiment was aiming to do with the data and that they could withdraw at any time before the experiment began.

Participants were also informed that any data collection would be made anonymous post-submission to ensure that the data was ethically collected. The data collected from individuals in the first survey for interest did not ask for background on the individuals besides their age and gender identity. This results in an inability to determine whether the population of the study is able to accurately draw conclusions for a general population.

The completion of the data collection resulted in 32 final participants which were used to form statistical results. Relying on the individuals to upload their data created an uncontrolled variable in the collection of the results. This limited the amount of data provided at the end of the experimentation, resulting in a reduced data set. In the data, a clear set difference was observed where male participants comprised 12.5% and female participants 87.5%, meaning the final data favours women’s experiences of phone usage under greyscale treatment rather than a broad range of adolescents reflecting a general population.

The secondary data form resulted in 26 responses using only individuals from the final data collection’s responses. The refinement of the data further limited understanding of phone usage under greyscale treatment to the experiences of the other individuals; however, it improves accuracy within the final data set.

Statistical analysis of the data set included the use of t-Test’s as the most appropriate choice for the investigation, to test for variance between two samples within the same population. The test was conducted using the 32 final data sets, allowing for the distinction between the treatment groups: colour and greyscale. The data was converted into minutes following the data representation from the Lundqvist and Ljungblad (2019), study. This allowed for clear expression of the data to be comparatively analysed, to find the result of no statistical variances.

The representation of data from the secondary form was visualised using Excel. The visualisation of data using pie charts allows for a pictorial representation of data, showing the categorical, numerical data. The pie chart demonstrates individuals went to sleep at the highest frequency, rather than remaining on their phones. This provides suggestions that the use of greyscale at night can reduce screentime. This supports Stiglic N, Viner RM (2019) study conveying lower screentime leads to a higher HRQOL. The column graphs were based on the Likert scale, allowing for a visualisation to summarise the ordinal data. The column graphs found that using greyscale made them bored rather than productive and it did not feel as though their screentime was reduced. This indicates that the use of greyscale was ineffective.

The final data involved predominately female responses; this is a result of reduced marketing towards a male cohort. The data size was small and did not represent a general population as the majority of data was collected from females. Future research should aim to use an equal spread of male and female participants, in order to find a more generalised sample as well as a larger sample size. The variables which could not be controlled included daily schedules, as well as examinations and extracurricular activities the individuals were participating in, which created a skew in the data sets. Future research should assess the schedules of individuals and aim for participants to be compared based on similar external factors. Furthermore, the participants were able to change their display as they were responsible for their own participation. Individuals in future studies should aim to develop or introduce an app for the individuals’ devices, allowing for a measure of whether greyscale was turned off and for how long, to encourage maintaining greyscale and increasing the accuracy of the results.

REFERENCES

2018, A. (2018, June 5). iOS 12 introduces new features to reduce interruptions and manage Screen Time—Apple (AU). Apple.Com. Retrieved 15 August, 2023 https://www.apple.com/au/newsroom/2018/06/ios-12-introduces-new-features-to-reduce-interruptions-and-manage-screen-time/

(Multiple Authors) Microsoft Research Canada, Attention spans (consumer insights Microsoft Canada), (Spring, 2015), Microsoft, Retrieved November 11, 2022, from: https://dl.motamem.org/microsoft-attention-spans-research-report.pdf

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https:// www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd

Burst, Dash (September 7, 2021) How to use the colour Psychology of Colour When Marketing, (Small business trends) Retrieved November 11, 2022 from: https://smallbiztrends.com/2014/06/psychology-of-colors.html

Future research should consider the usage of other devices as a form of screentime, without the application of greyscale. Consideration should be taken of applying greyscale across all devices, as well as using a control group for the greyscale week. This can be done by using multiple groups with the same schedule to determine the distinction greyscale has on people with similar phone usage, or phone settings.

CONCLUSION

The study investigated whether the change of normal colour to greyscale in adolescents’ phones, aged 16 to 18, was capable of reducing screentime on their phone. The data collected failed to reject the null hypothesis there is no difference between greyscale and colour in screentime as the t-Test displayed no statistical difference as a result in shifting user experience.

The surveys informed the investigation of individuals’ diverse responses to the effect of greyscale in their everyday routines. The secondary survey expressed a moderate impact in experiencing boredom rather than productivity on the Likert scale, further identifying individuals did not feel as though their screentime was reduced and therefore demonstrated the ineffectiveness of greyscale. The use of t-Test’s comparing sample means effectively demonstrated no statistical difference, consistent with the users’ reflections of phone usage.

The study provides evidence of uncontrolled variables in the experiment and limitations such as examination timetables and a restricted sample size. These factors assist future research with plausible constraints and enable a broader understanding of variables. Therefore, the hypothesis If you use greyscale on phones, rather than normal colour, the amount of screen time will be reduced is not supported by the findings.

CK, Connors, (2014) Conners Continuous Performance Test – Third Edition / Conners Continuous Auditory Test of Attention (Conners CPT-3 / Conners CATA) Combo Kit | Psychology Resource Centre Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://psycentre.apps01.yorku. ca/wp/conners-continuous-performance-test-third-edition-conners-continuous-auditory-test-of-attention-conners-cpt-3-conners-cata-combo-kit/

Clayton, R. B., Leshner, G., & Almond, A. (2015). The Extended iSelf: The Impact of iPhone Separation on Cognition, Emotion, and Physiology. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(2), 119–135. Retrieved February 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12109

Hamill, Jasper. (2019, April 12). How to beat smartphone addiction by turning your screen black and white. Metro. Retrieved November 11, 2022 https://metro.co.uk/2019/04/12/making-iphone-display-black-white-boost-happiness-wellbeing-9181828/

Haynes, Trevor & Clements, Rebecca. (2018, May 1). Dopamine, Smartphones & You: A battle for your time. Science in the News https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/dopamine-smartphones-battle-time/

Korkmaz, S., Özer, Ö., Kaya, Ş., Kazgan, A., & Atmaca, M. (2016). The correlation between color choices and impulsivity, anxiety, and depression. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 13(3). Retrieved 15 August 2023 https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/81905

Lundqvist, J., & Ljungblad, V. (2019). Influence your screen time A study on how a grayscale display can affect the use of social media on smartphones (written in Swedish). 39. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from: http://hb.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1385002/ FULLTEXT01.pdf

Roberts, A.J., Koob, G. F (1997). The neurobiology of addiction.EBSCO [Full online text]. Retrieved 15 August 2023 https://research. ebsco.com/c/n4ycs7/viewer/html/edw7e3qrkf

Stiglic, N., & Viner, R. M. (2019). Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open, 9(1), e023191. Retrieved 15 August 2023 https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191

The Black-and-White Approach to Curbing Smartphone Addiction. (2018, January 18). MEL Magazine. Retrieved November 11, 2022, From: https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/the-black-and-whiteapproach-to-curbing-smartphone-addiction

Tinius, T. P. (2003). The Integrated Visual and Auditory Continuous Performance Test as a neuropsychological measure. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 18(5), 439–454. Retrieved on November 11, 2022, from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6177(02)00144-0

Trakulkongsmut, Phaisit, M.D (2020, June 11) 8 key factors behind the production of happiness hormones. (n.d.). Retrieved June 1, 2023, from https://www.samitivejhospitals.com/article/detail/happiness-hormones

Vera San Juan, N., Oram, S., Pinfold, V., Temple, R., Foye, U., Simpson, A., Johnson, S., Hardt, S., Abdinasir, K., & Edbrooke-Childs, J. (2022). Priorities for Future Research About Screen Use and Adolescent Mental Health: A Participatory Prioritization Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. Retrieved 15 August 2023 https://www.frontiersin.org/ articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.697346

Wright, Addy (October 21, 2018) Smartphones: Delivering Your Daily Dose of Dopamine in a Convenient, Pocket-Sized Package! Retrieved February 1st 2023 https://turnagain.alaskapacific.edu/smartphonesdelivering-your-daily-dose-of-dopamine-in-a-convenient-pocketsized-package/

ABSTRACT

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that is the leading cause of dementia. There is a global and urgent need to develop effective, potent, and specific therapeutic agents against AD, especially diseasemodifying therapies which would greatly improve the prognosis and quality of life of AD patients. The difficulty lies in a lack of understanding of AD pathology. AD is characterised by extracellular plaques and intracellular tangles, composed of beta-amyloid 42 peptide (Aß) and tau protein respectively. Existing research demonstrates that they have impacts on one another, but specifics are still unknown. I propose research into this relationship between Aß and tau. I aim to definitively explain how Aß causes tau neurofibrillary tangles. This research will inform successful treatment development and further our understanding of AD.

Key words: Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid 42, tau protein, tauopathy, hyperphosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder with an estimated prevalence of 416 million people worldwide (Gustavsson et al., 2023). It leads to a gradual decline in cognitive ability and loss of independence in daily activities. There is no cure for Alzheimer’s. Currently, AD treatment is generally symptomatic rather than disease-modifying, and the success rate for AD drug trials is a notoriously low 0.04% (Cummings, Morstorf & Zhong, 2014). This is, in part, due to an incomplete understanding of AD. Two key aspects of AD are extracellular Aß plaques and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangles, which both develop from normal forms of proteins and have distinguishable impacts on one another. Establishing the direct relationship between the two proteins (Aß and tau) has yet to be done, but this is vital to understanding AD mechanisms. Thus, I present my aim: To determine Aß’s role in tau hyperphosphorylation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

AD pathophysiology

Two proteins play an important role in AD: beta-amyloid 42 (Aß) and tau proteins. Aß is a peptide created through abnormal, enzymatic breakdown of amyloid precursor protein. These peptides form extracellular, neurotoxic plaques which contribute to inflammation, neuronal death, and resulting cognitive decline (Bayer, 2010; Breijyeh & Karaman, 2020). Tau proteins are normally

parts of microtubules but become abnormal through enzymatic processes. Enzymes, such as kinases, attach phosphates to the tau protein excessively, which interrupts normal function and structure. This is called hyperphosphorylation, and, as a result, the abnormal tau proteins form neurofibrillary tangles and gain neurotoxicity (Gong & Iqbal, 2008).

Aß and tau

Determining the specifics of the relationship between the two would be invaluable in informing future research and therapy development. We know that Aß plaques develop earlier in AD pathology and that Aß can lead to the hyperphosphorylation of tau, later in AD pathology. Despite the instrumental roles of Aß and tau in AD, their direct relationship is not yet clear, as studies usually isolate the proteins. My research aims to address the lack of holistic AD research.

Modelling AD in vivo and ex vivo

A mouse model is the most common research tool when investigating AD pathology, but raises ethical concerns and issues of translatability from mouse to human brains (Slanzi et al., 2020). There are many ex vivo models such as brain slice cultures, neural cell cultures (2D or 3D, and mono-, di- or tri-cultures) [Choi et al., 2016; Croft et al., 2019; Goshi et al., 2020; Batenburg et al., 2023]. These ex vivo models (specifically, 3D tri-cultures) are ideal for researching my aim. Batenburg et al. (2023) recently developed a 3D human co-culture of neurons and astrocytes. This high throughput, physiologically-relevant culture forms the basis of my methodology.

METHODOLOGY

3D tri-culture

I propose further developments upon Batenburg et al.’s (2023) 3D co-culture in order to understand Aß’s role in phosphorylated tau development (specific method as outlined previously [Batenburg et al., 2023]). This was a culture of only human neurons and astrocytes, and no microglia, which are key in AD pathology. I propose to use a 3D tri-culture of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia in my research. I believe that I can feasibly obtain human microglia with similar techniques to Goshi et al. (2020)’s 2D mouse tri-culture, and that it can inform the modifications required to make the 3D medium suited to supporting microglia.

Inducing and observing tauopathy

Using the 3D tri-culture, I intend to investigate the cause

of tau hyperphosphorylation and induce tauopathy through selective expression of Aß, and/or the kinases involved in phosphorylation. For example, one trial could look like introducing Aß to a culture where only one of the six kinases (Gong & Iqbal, 2008; Zhang et al., 2021) involved in phosphorylation are active. This selective expression could be facilitated by either genetic mutations (i.e. gene knockout through lentiviruses, CRISPR cas-9, etc.) or through enzyme inhibitors (Breijyeh

& Karaman, 2020). Thus, the presence of Aß and specific kinases is the independent variable, while the production of hyperphosphorylated tau becomes the dependent variable. This can be measured using immunofluorescent staining and microscopy (as outlined in Batenburg et al., 2023). By producing various combinations of Aß and kinases, I will be able to observe which combinations result in hyperphosphorylated tau. This will definitively determine Aß’s role in tauopathy.

REFERENCES

Batenburg, K. L., Sestito, C., Cornelissen-Steijger, P., Van Weering, J. R. T., Price, L. S., Heine, V. M., & Scheper, W. (2023). A 3D human co-culture to model neuron-astrocyte interactions in tauopathies. Biological Procedures Online, 25(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12575-023-00194-2

Bayer. (2010). Intracellular accumulation of amyloid-beta – a predictor for synaptic dysfunction and neuron loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnagi.2010.00008

Breijyeh, Z., & Karaman, R. (2020). Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment—PMC. Retrieved May 24, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7764106/#B59-molecules-25-05789

Choi, S.H., Kim, Y.H., Quinti, L. et al. (2016). 3D culture models of Alzheimer’s disease: A road map to a “cure-in-a-dish”. Mol Neurodegeneration 11, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-016-0139-7

Croft, C. L., Cruz, P. E., Ryu, D. H., Ceballos-Diaz, C., Strang, K. H., Woody, B. M., Lin, W. L., Deture, M., Rodríguez-Lebrón, E., Dickson, D. W., Chakrabarty, P., Levites, Y., Giasson, B. I., & Golde, T. E. (2019). rAAV-based brain slice culture models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease inclusion pathologies. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 216(3), 539–555.

Cummings, J. L., Morstorf, T., & Zhong, K. (2014). Alzheimer’s disease

drug-development pipeline: Few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 6(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/ alzrt269

Gong, C.-X., & Iqbal, K. (2008). Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: A promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 15(23), 2321–2328. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986708785909111

Goshi, N., Morgan, R. K., Lein, P. J., & Seker, E. (2020). A primary neural cell culture model to study neuron, astrocyte, and microglia interactions in neuroinflammation. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 17(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01819-z

Gustavsson, A., Norton, N., Fast, T., Frölich, L., Georges, J., Holzapfel, D., Kirabali, T., Krolak-Salmon, P., Rossini, P. M., Ferretti, M. T., Lanman, L., Chadha, A. S., & Van Der Flier, W. M. (2023). Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(2), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/ alz.12694

Slanzi, A., Iannoto, G., Rossi, B., Zenaro, E., & Constantin, G. (2020). In vitro models of neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 8, 328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.00328

Zhang, H., Wei, W., Zhao, M., Ma, L., Jiang, X., Pei, H., Cao, Y., & Li, H. (2021). Interaction between Aß and Tau in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 17(9), 2181–2192. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.57078

Loss of regenerative capacity is a normal part of aging. However, some creatures, such as the Mexican axolotl, retain amazing regenerative abilities throughout their lives. In addition, age-related diseases rarely develop in this organism. This Science Fair assignment will explore how the axolotl is used as a model system to study regeneration processes, what new technological advances are currently available with this model, and how the axolotl can consider how to apply lessons learned from regeneration research.

It may be possible to understand and treat age-related decline in humans. Rebirth is part of life. The ability to replace old or damaged cells in all organ systems is important not only for tissue homeostasis but also for the long-term survival of an organism. The ability to repair wounds is a property common to all living organisms, as are many mechanisms for healing these wounds. However, the ability to regenerate more complex structures such as limbs varies widely among tetrapod species. It is well documented that this ability to replace tissues during homeostasis and heal acute injuries is adversely affected by the aging process in most organisms. However, some species are better at reproducing to adulthood than others. Humans pass through several temporal stages throughout their lives, including embryonic and fetal development, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, middle age, mature adulthood, and ultimately death.

Each stage is characterised by important physiological changes. Some changes appear to be programmed, such as those caused by endocrine signals, while others are a response to environmental factors, such as diet or normal cellular metabolism. Determining exactly when human aging begins is difficult, perhaps because so many genetic and environmental factors can influence this process. However, these include loss of fertility, decreased metabolism, depletion of the adult stem cell pool, increased cellular senescence, increased DNA damage, altered immune responses, increased time to injury healing, and increased incidence of age-related diseases. There are several characteristics (cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, etc.) that are all associated with the aging process. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying age-related pathologies will play an important role in developing treatments that improve quality of life in later life.

Loss of regenerative capacity is a normal part of aging.

However, some creatures, such as the Mexican axolotl, retain amazing regenerative abilities throughout their lives. In addition, age-related diseases rarely develop in this organism. This essay will explore how the axolotl is used as a model system to study regeneration processes, what new technological advances are currently available with this model, and how the axolotl can consider how to apply lessons learned from regeneration research. It may be possible to understand and treat age-related decline in humans.

Although there is no data on mortality rates for these creatures, the maximum lifespan of axolotls in captivity is estimated to be up to 25 years. Despite the lack of agerelated studies in this species, changes in the animal’s body structure can be observed over time. One of these changes is size. The axolotl is an animal that grows indefinitely and grows larger throughout its life. Another reason lies in its skeletal structure. During the larval stage, the axolotl’s skeleton contains a lot of cartilage, which is replaced by bone as the animal ages. Changes in tissue composition are also evident as animals age, such as the skin layers on their limbs becoming thicker. Behavior also changes with age. Larvae of young animals are able to move and eat more frequently compared to older animals, suggesting that, as in humans, their metabolism also declines with age. Limb regeneration begins with amputation (although not all wounds regenerate). During the first few hours, the wound epithelium migrates to the wound site. Nerve fibers then innervate this wound epithelium. This signaling loop runs between the nerve and the wound epithelium. (This is called the apical epithelial cap). This center then produces several signaling molecules that cause the underlying mature limb tissue to dedifferentiate and proliferate into limb progenitor cells known as blastema cells. Interactions between cells from opposite axes of the limb in the wound determine the pattern of structure of the missing limb. Once this pattern is established, cells redifferentiate into the structure of the defective limb.

Several studies on axolotls have shown that there are three basic requirements for limb regeneration. 1) wound epithelium, 2) neural signals, and 3) presence of cells from different axes of the limb. One such study established a regeneration assay known as the accessory lime model (ALM) and showed that the combination of these three components is sufficient to generate limbs. In this study, an ectopic limb was created in a lateral wound on the side of the arm with both a deviated nerve bundle and

a skin graft from the opposite side of the limb axis. ALM has evolved into a powerful regeneration assay that provides a platform to examine each of these specific regeneration requirements in a gain-of-function sense. Therefore, ALM and other regeneration assays will play an important role in understanding the fundamental biology of limb regeneration. Axolotls retain amazing regenerative abilities throughout their lives. Although the success rate of regeneration decreases with age, they still exhibit regenerative abilities that far exceed those of humans and other mammals. This age-related decline in the regenerative capacity of axolotls can be caused and/ or influenced by many factors.

This age-related decline in the regenerative capacity of axolotls can be caused and/or influenced by many factors. The reproduction rate of axolotls slows as they get older, from several weeks for larvae to several months for sexually mature adults. This may be a result of the animal’s size. Small animals have smaller limb circumference and mass than adults, resulting in faster wound closure and tissue recovery. As axolotls age, the skin may thicken and lose flexibility, complicating the formation of wound epithelium, and sufficient positional interactions may not occur at the injury site for the formation of complete limb structures. It will be expensive.

Additional factors such as circulating factors and hormones may also play a role in the timing of regeneration in aging animals, but this possibility remains to be investigated. Metamorphosis can also negatively impact limb regeneration. In amphibians, metamorphosis is activated by thyroid hormone signals. Frog species that can reproduce as tadpoles have a reduced ability to regenerate entire limbs during metamorphosis. Spontaneous metamorphosis rarely occurs in axolotls, but the process can be induced by thyroid hormones. Although axolotls retain the ability to regenerate after metamorphosis, they are prone to pattern loss and are often missing fingers. This problem is probably related to changes in skin morphology and its impact on wound healing. Interestingly, the lifespan of an axolotl is significantly reduced after metamorphosis, with metamorphic animals typically only living for 1 to 2 years after the process is complete. However, because metamorphosis is not part of the axolotl’s normal life cycle, it remains unclear whether the regeneration failure in this situation is age-related or due to changes (and abnormalities) in the physiology of the metamorphosed axolotl. It’s difficult to judge.

Immune system: Chronic inflammation is associated with the development of age-related disease and frailty in humans. Age-related weakening of the immune system is associated with increased risk of infection and reduced effectiveness of vaccination. In both mammalian and amphibian models, immune system

development is associated with loss of regenerative capacity. Although immune system activity has not been studied in aged axolotls, inflammatory responses can have both positive and negative effects on regeneration. For example, the immune system appears to be suppressed in the regenerating limb, as allografts from transgenic animals show little or no rejection during the regeneration reaction. This may be due in part to the simpler adaptive immune system of axolotls compared to mammals. The presence of immune cells is also a prerequisite, despite anecdotal evidence that immune responses are suppressed during regeneration. For example, macrophages are essential for regeneration of both the heart and limbs of axolotls. Macrophages may play multiple roles in regeneration, removing tissue and cell debris within damaged tissues and removing senescent cells from regenerating tissues. Finally, both pro- and anti-inflammatory signals are induced in the regenerating limb environment. Therefore, the balance between suppressive and immune responses required for regeneration appears to be highly regulated and requires further investigation.