PARAGON OF A POROS‘CITY’

By PRIYAL NIMESH VANDANA PAREKH

GUIDED BY Ar. Rohit Shinkre

A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment

Of the requirements for SEM-IX

The Degree

BACHELOR OF ARCHITECTURE

MUMBAI UNIVERSITY MUMBAI, MAHARASHTRA.

5TH YEAR, SEM-IX, BARD 911, DEC’2020

Conducted at: RACHANA SANSAD’S

ACADEMY OF ARCHITECTURE, UN-AIDED COURSE

RACHANA SANSAD, 278, SHANKAR GHANEKAR MARG, PRABHADEVI, MUMBAI 400025.

A P P R O V A L C E R T I F I C A T E

The following Under-Grad Design Dissertation Study is hereby approved as satisfactory work on the approved subject carried out and presented in a manner sufficiently satisfactory to warrant its acceptance as a pre-requisite and partial fulfilment of requirement to the 5th Year Sem IX of Bachelor Of Architecture Degree for which it has been submitted.

This is to certify that this student Priyal Nimesh Vandana Parekh is a bonafide Final Year student of our institute and has completed this Design Dissertation under the guidance of the Guide as undersigned, adhering to the norms of the Mumbai University & our Institute Thesis Committee.

It is understood that by this approval and certification the Institute and the Thesis Guide do not necessarily endorse or approve any statement made, opinion expressed or conclusions drawn therein; but approves the study only for the purpose for which it has been submitted and satisfied the requirements laid down by our Thesis Committee.

Name of the Student: Priyal Parekh

Date: 13th December 2020

Approved By Principal Ar. Prof. Rohit Shinkre College Seal

By Thesis Guide Ar. Prof.

Shinkre Certified Seal

By External Examiner-1 External Examiner-2 ( ) ( )

Certified

Rohit

Examined

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that this written submission entitled “Paragon of a PorosCity” represents my ideas in my own words and has not been taken from the work of others (as from books, articles, essays, dissertations, other media and online); and where others’ ideas or words have been included, I have adequately cited and referenced the original sources. Direct quotations from books, journal articles, internet sources, other texts, or any other source whatsoever are acknowledged and the source cited are identified in the dissertation references.

No material other than that cited and listed has been used.

I have read and know the meaning of plagiarism* and I understand that plagiarism, collusion, and copying are grave and serious offences in the university and accept the consequences should I engage in plagiarism, collusion or copying.

I also declare that I have adhered to all principles of academic honesty and integrity and have not misrepresented or fabricated or falsified any idea/data/fact source in my submission.

This work, or any part of it, has not been previously submitted by me or any other person for assessment on this or any other course of study.

Signature of the Student

Name of the Student: Priyal Nimesh Parekh Exam Roll No: 2092UBARC030F

Date: 13th December 2020 Place: Mumbai

*The following defines plagiarism: “Plagiarism” occurs when a student misrepresents, as his/her own work, the work, written or otherwise, of any other person (including another student) or of any institution. Examples of forms of plagiarism include: the verbatim (word for word) copying of another’s work without appropriate and correctly presented acknowledgement; the close paraphrasing of another’s work by simply changing a few words or altering the order of presentation, without appropriate and correctly presented acknowledgement; unacknowledged quotation of phrases from another’s work; The deliberate and detailed presentation of another’s concept as one’s own.

“Another’s work” covers all material, including, for example, written work, diagrams, designs, charts, photographs, musical compositions and pictures, from all sources, including, for example, journals, books, dissertations and essays and online resources.

I am grateful, for this opportunity to be able to do this thesis with utmost passion, which would not be possible without the following.

The guidance, insightful discussions & questions of my guide Ar.Prof.Rohit Shinkre

The support of Harshada ma’am and Tushar sir has also been a guiding light.

The strength Apurva ma’am gave me throughout my architectural journey.

My mum for her creative genes and everything she ever does for me.

My dad for believing in me, pushing me & finding his dreams in mine.

My grandparents for all the wise words and blessings.

My friends and family for their motivation throughout.

Lastly, to my Dadi who is smiling somewhere

I will be thankful to all of you eternally, for giving me the drive & vigor to achieve this.

Thank you.

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

Paragon of a Poros‘CITY’

A story of Mumbai through the lens of its water edges

I. THE PROLOGUE

1. Preface 2 2. Abstract 3 3. Keywords 4

II. THE QUEST

1. Aims & Objectives 5 2. Architectural Questions 6 3. Methodology 7

III. THE PERSPECTIVES

1. Chapter 1 – Looking into the PAST 1.1History of Mumbai Literature Review - Gazetteer of Bombay 12 1.2 Mumbai’s Water Terrain Literature Review – Soak 15 1.3 City on the Water 18 1.4 Interviews with experts (Dilip da Cunha, Debi Goenka, Roberto Rocco) 19 1.5Perspectives 22 1.6Inferences

2. Chapter 2 – Delving in the PRESENT 2.1Qualities water adds to an edge 25 2.2 Power of a waterfront in urban environment 27 2.3Understanding the land water edge 30 2.4Duality of the edge 31 2.5Publicness and water edge 33 2.6The Urban Transect Method 35 2.7Architectural response to land water edges in India 37 2.8Analysis of various cities 40 2.9Living with Water – Humans & water relation 49 2.10 Multisensory human experience at water edge 53 2.11 Associations & Human perception 55 2.12 Types of coastal edges 58 2.13 Di (section) of Mumbai’s terrain i. Edges considered 63 ii. Mapping out various edges 65 1. Marine Drive 68 2. Haji Ali 71 3. Mahim Bay 75 4. Bandra Bandstand 79 5. Colaba 83

C O N T E N T S

3. Chapter 3 – TRIGGER - the Issue 3.1The impact 91 3.2Sea level rise 93 3.3Susceptibility Of Mumbai 94

iii. Observations 87 iv. Intentions 90

3.

5.

4. Chapter 4 – Reflection of the FUTURE 4.1Edging towards solutions 97 4.2Blue Green infrastructure 99 4.3Micro to macro level intervention 101 4.4Adaptive strategies against flooding I.Nature Based Strategies 104 II.Foundation 107 III. Structures 108 IV. Material Resistance 109 4.5Case studies 1. The Cove 111 2. Little Island Project 113

Resilience by Design 115 4. Jellyfish Barge 117

City Apps 119 CONCLUSION 122

1. Scope

2.

3.

4. CRZ

5.

6. Case

IV. THE POSSIBILITIES

124

Towards an architecture intervention 125

Selected site 127

norms 129

Proposed program 130

studies 131

1. Conclusion

2. Bibliography

3. References

4. List of figures

Appendix

V. THE EPILOGUE

136

137

138

/

139

1

PREFACE

Water is an important defining element of settlements across the world and can be traced back through a city’s historical structure and morphology. The relationship between a city and its waterfront is unique and always changing, depending on the functions carried out on adjoining land.

The city of Mumbai sings out two things – the sea and its monsoon. The essence of the city is its vast coastline on all sides, combined with various rivers and creeks making a lot of water edges prominent in it.

Often we ponder about ‘what ifs’, how a particular thing would have been if certain events did not happen. We definitely we cannot change them now, yet we try to shuffle and adjust between these. These are relating to memories of a place or person, or experiences good or bad that have impacted us in a certain way. One important aspect in everyone’s life is the ‘Place’, either their place of livelihood or a place of relaxation or a native place. A city, where millions toil & live, even more aspire to come, where even more create their aspirations into reality – Mumbai. Through centuries Mumbai has seen growth in all forms of infrastructure. From its economic infrastructure to social to colonizing land leading increase in grey infra, but in this the Blue-Green infrastructure have taken a hit in some way or the other. A compromise, in order to grow the socio-economic scene, the green spaces and water edges got neglected. Our development over decades has not respected these elements enough, and its high time since just in a few decades we will pay the repercussions will be much bigger and combating these issues will be almost impossible if not acted now.

Mumbai has a list of factors that make it how it is today, majorly the reclamation of the seven islands into one is what helped its growth so rapidly. Today studies show, in a few decades down the line the city is on the threat of coastal flooding to an extent to make the city like separate islands in water once more. This research will further talk about the city, through its own perspective a journey through the past - present and future, but all in respecting the aqueous edges

2

H E P R O L O G U E

T

ABSTRACT

The architecture for water transcends time and space in its proliferation across geographies and cultures. These unique and diverse structures articulated the anthropogenic relationship to water, seamlessly weaving in the spiritual with the mundane.

This book proposes that the architecture for water represents an ecosystem of entities forming a network of relations, perceptions and associations with water. The research tries to understand these networks and links. The potential needs to be realised to act upon, to prevent these edges from becoming obsolete, and informal. A revitalisation process needs to begin through this research which aims to tie these and pose a possible outcome to sustain in the future. This research is looked at in the contextual framework of urban scenario of the city of Mumbai, which is essentially a coastal city, but in the realm of infrastructure is losing out on its natural entities. This research aims to recognise these qualities that can bring out spatial and experiential narratives through place making power of a water edge. They must be ecologically and spatially coherent and responsive to a humanised scope.

Ebb & Flow

(By Priyal Parekh)

I am the giver of all birth, every organism on this Earth, is a part of me in disguise, yet why is it me you despise?

I constitute half of every living, aid create the non-living, yet why do you overlook my quality of giving?

In every shape and form I remain versatile, yet toward me it’s you humans who are hostile?

An indispensable cycle I follow, it contains of precipitation condensation and my ebb and flow, throughout these I help you grow.

I hide my tears in my bountiful expanse, rather I take you to a place of tranquil and trance.

In return a small request is what I pose, respect me as much as the motherland you chose.

I promise to not be the enemy you see, but a boon till eternity.

3

KEYWORDS (Definition of words in relation to this dissertation)

Edges - Edges are the linear elements not used or considered as paths by the observer. They are the boundaries between two phases, linear breaks in continuity: shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls.

Ubiquitous - seeming to be everywhere or in several places at the same time. The quality of water to be present in every place in different forms of precipitation and levels of wetness

Transect - The urban-to-rural transect is an urban planning model created by New Urbanist Andrés Duany. The transect defines a series of zones that transition from sparse rural farmhouses to the dense urban core. Each zone is fractal in that it contains a similar transition from the edge to the centre of the neighbourhood.

Porosity - is the volume of pores relative to the total space, and it's a good measure of how much water the ground can hold.

Place making - a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces. Place making capitalizes on a local community's assets, inspiration, and potential, with the intention of creating public spaces that promote people's health, happiness, and well-being.

Intertidal - of or denoting the area of a seashore which is covered at high tide and uncovered at low tide

Water urbanism – it is an innovative approach to design practice and pedagogy that holistically joins the study of social and physical infrastructures, public health, and hydrological systems. Water Urbanism posits that water and cities must be understood within an expanded notion of a constructed ecosystem.

Blue infrastructure - It refers to urban infrastructure relating to water. Blue infrastructure is commonly associated with green infrastructure in the urban setting and may be referred to as "blue-green" infrastructure when in combination.

4

AIM

To establish an understanding of various associative factors relating to the land water edges and delve out issues faced by users in the present. To also consider the future issues projected and draw out a parallel to define a paradigm by proposing an architectural intervention that affects the urban setting of the land water edge, forming an image of the city through it.

OBJECTIVES

o To deploy a sectional view then a plan view of the waterbody – land interface, and understand how intersections differ.

o To determine how development decisions played a role in the land water edge

o To analyse different land water intersections in the city of Mumbai, and comparatively differentiate between them.

o To determine the humanised aspect as well as de human aspect of the edge.

o To understand what is retained, what is proposed? What is changing? What needs change? All near the water edges of the city

o To understand different perceptions of people towards these edges – analyse the needs and issues from their perspectives

o Study human and environment responses to calamities like flooding

o Analyse data maps on issues of these areas – 1. Altitude 2. Sea level increase mark 3.Year projection 4. Risk zone map 5. Risk data analysis 6.Proposed land use

o To study solutions – both nature based as well as technological to pose an intervention to solve these.

o To propose a program as a solution against the issues – that would humanise the edge and increase the public dialogue with the sea.

5 T H E Q U E S T

ARCHITECTURAL QUESTIONS

Primary Questions –

1. How do people perceive an edge of land and water in the city?

2. What is the experiential and spatial quality of various edges in the city, what way does it impact the overall fabric?

3. How to assess the issues faced in these different ecological realms of the city?

4. What architectural intervention can be proposed to create an urban paradigm in the city for combating the issues assessed?

Secondary Questions –

1. Why do we draw a border between land and water that defines perceptions of only land as habitable?

2. Is the cartographic conventional mapping practice justified to understand the quality of understanding the estuarial nature of Mumbai?

3. Can an architectural intervention be made with adaptive biotechnologies or nature based solutions, which is a better solution?

4. How will nature claim back its pieces in the city, how can users be equipped for it?

6

METHODOLOGY

Delving from the past of the city to the future, this research is a bridge to understand the land and water edges of the city and make use of adaptive bio solutions to cope with the forthcoming problems. It is a futuristic approach to the city addressing a serious concerns that are rising in the urban fabric of the major metropolitan city.

It is a culmination of data showing the issues and impacts that will raise the load on urban area in upcoming decades. Architecture that is not only responsive but resilient and symbiotic with all the elements of the Earth. To give nature what is rightfully it’s and claim our space and make our place because there is no planet B.

The book will be divided into three POVs - Past, Present Future. The latter holding the most important in design forward.

1.

The Past - Point of View

Suggestively this chapter is the literature review of all that has been written about Mumbai and its relation of built, in sync with the water terrain of it. A historical analysis from books, articles, essays and drawings of the city’s development.

2.

The Present Point of View

This is the chapter which describes today’s developments in the city. The urban and environment connect. It will include the main issue of study. All firsthand interviews and data is necessary for this part, which will convince why it is the need for the future.

3.

The Future Point of View

This is the most technical part of the book, including inferences of all culminated data. It will be a projection on the adaptive technologies we need to adapt and the changes we need to make to be able to sustain the catastrophe. It highlights this kind of practice called Archi (Bio) tecture which is symbiotic style of design that includes adapting biotechnologies and biomimicry to create a sustainable and dependable future.

7

Three parts of architecture – 1. Site 2. People/User 3. Structure All of these aspects are prioritised and linked in this dissertation in the following ways.

1. Site – Context of Mumbai

Looking at the urban metropolis of the city of Mumbai, the dissertation talks about a site specific approach through the edges of land and water in the city. This is done by intensive mapping of various factors these different edges. A comparative analysis as well as comprehensive inferences are made. Furthermore after analysis and detailing out five specific edges, it is narrowed down to two which have the highest potential and requirement.

2. User – People using the various edges of the city

The relation of water and civilisations is what connects our past into the present. This is associations of various religions, traditions, cultures and personal memories of spaces with water edges. These qualities are mapped out and compared for different sites. The way different associate and use this edge in various contexts is extremely different. Potential is tried to be marked out from this as well to furthermore. Their needs for space and the quality of place making of water are what go hand and hand to create a proposal.

3. Structure – Resistant and inclusive technological responses

Taking various issues like flooding, monsoon waterlogging, runoff wastage and sea level rise as future triggers, the need arises to create something that would combat these. Architecture that is inclusive, and not sustaining but resilient to these as well helps positively pose solutions is what is aimed at. This architectural intervention involves the need for use of new adaptive strategies and technologies. Two lenses of technological advancements as well as selfsustenance can be taken as study measure. In accordance to the requirements of the function and responsiveness of the site a couple of the strategies will be designed in the proposal trying to pose as a paradigm for buildings to follow for a step towards a more blue and green future.

8

9

LOOKING THROUGH THE P A S T

10

11

1.1 HISTORY OF MUMBAI

A famous quote goes by saying “Mumbai is my heart, Bombay is my soul.”

Oh what a journey has the city seen, from Bombay to Mumbai, throttling at a speed that waits for none, and just grows. It is evolved into a beauty from seven separate island pieces to a conglomerate that is today one of the most prominent and strongest city in the world.

It has always been described as an archipelago, from historic times it was always chanced on. The Magadha Empire of King Ashok is assumed to be the oldest settlers in Mumbai, who left behind the Koli (fishermen) community, and various temples and stone carvings. One of which the Mumba Devi Temple, on which the city soon seem to be named. Bombay changed hands from many dynasties and rulers, the oldest structures in the archipelago the caves at Elephanta, and part of the Walkeshwar temple & Banganga Tank probably date from this time, are still present today.

“On the other side of the great inlet to the sea is a great point abutting against Old Woman's Island, a rocky woody mountain which sends forth long grass. Atop of all is a Parsee tomb, lately reared: on its declivity, towards the sea is the remains of a stupendous Pagoda near a tank of fresh water (Walkeshwar) which the Malabars visited it mostly.’ – Description of Banganga Tank.” – Gazetteer of Bombay, 1909

The seven islands were – Colaba, Little Colaba, Bombay, Mazgaon, Mahim & Parel namely. They started developing on their own, little trades flourished on the coasts, sea transport becoming one of the most important then. Soon the reclamations began when they transformed the archipelago into one landmass. The ecological boundary of Bombay being formed as the beautiful interface of land and sea, with many rivers and creeks making their way through the topography.

“In the north and east large schemes of reclamation have similarly shut out the sea anti partly redeemed the foreshore for uses. In the extreme north of the island a large tract of salt marsh still remains unclaimed. Old Marathi documents and the statements of early European writers have proved that Bombay originally consisted of several separate islands, which remained practically unaltered in shape until the eighteenth century. During the era of later Hindu and Muhammadan sovereignty, the two southernmost islands, afterwards named Colaba and Old Woman's Island, formed a broken tongue of rocky laid marked by a few fishermen's huts and divided from the third Island by a wide strait of considerable depth at high tide.” – Gazetteer of Bombay, 1909

Fig 1. Mumbai development through the years

12

The city has always had a major advantage of being a peninsula, surrounded on three sides by water. It was the only form of major transport at that time, thus having it on all sides could help it develop into a major port for the country. The waters were known to be rich in biodiversity. Sea farers have seem to have spotted whales in its waters. This not only gave a boost to the Koli fishing community for trade, but also made the city an attractive spot for all. It expanded beyond limits to become the metropolis of Mumbai it is today, due to various trades that were boosted due to its geography.

“From time to time whales have appeared in the neighborhood of the island...In April 1906 a whale, 63 feet in length and apparently belonging to the Greenland species, drifted ashore at Bassein in the Thana District. Sea-snakes are common in Bombay waters, and prior to the building of the causeway, Colaba was famous for turtles.” –Gazetteer of Bombay, 1909

Fig 2. Fig 3.

Original seven islands of Bombay First Reclamation by British in 1700’s

The Bombay Dockyard, 1983, explains how Colaba Causeway was built in the mid1800s. Like the iconic Marine Drive, the Causeway was also born out of extensive reclamation.

“In the beginning of the 16th century Colaba was joined to the Island of Bombay by a ledge of rocks over which the sea water flowed. This channel was usually crossed in a ferry...In later times it became a pleasant residential quarter, but often at high tide...it became difficult to cross the channel. This inconvenience was at length overcome by the erection of a solid and handsome vellard with a footpath protecting the level and elevated road.” – Gazetteer of Bombay – 1909.

13

Soon after the Portuguese, the British East India Company settled in the islands of Mumbai. They documented the city during summers, and saw much more land. They began to reclaim land from the sea to join the masses of islands in a conglomerated land parcel. Historian Gyan Prakash calls it ‘‘Double colonization of Earth and sea.” This has us battling still every year when the monsoons being back to life the contours of the old archipelago. The rivers and sea comes back fiercely every year proving it will claim back it’s rightful. The British aimed this colonization as an economic gain aspect, to develop the city to a major port just like they had of Surat and Ahmedabad in those times.

“The island of Bombay should now no longer be considered a settlement of a separate colony but as the metropolis...of an extensive domain. For this island, only 20 miles in circumference and almost covered with houses and gardens, will soon become a city similar to the outer towns of Surat and Ahmedabad.” – Gazetteer of Bombay 1909.

Fig. 4

Fig 5.

Reclaimed land map 2000s connections Flood prone areas current map

The above maps symbolize the evolution of associations throughout the decades. Figure 2 shows how the original seven islands were displaced from one another with water inlets making their way in and out. Until the British invasion, they began reclaiming in the 1700’s (figure 2). The city grew and became one of the biggest trading ports of that times. The reclamations continued further north, making Bombay to Mumbai, one of the biggest metropolitan cities today. With this exponential growth, it came with its own set of problems, lack of infrastructure to support this led in lot of issues especially every monsoon it saw flooding. Figure 5 shows the overlaid old reclaimed map with the current flooding areas which takes us back to Fig. 2 the original seven islands are spared and most of the areas that get flooded are the reclaimed bits, which support majority of the city. This shows how nature will rightfully claim back what is rightfully it’s.

14

1.2. MUMBAI’S WATER TERRAIN

Mumbai a city that smiles at you at any realm of life. As inviting as she is, as endearing as she is, as empathetic she is, absorbs everything in her stride. Today she is a pride for the country. What more can be said about the splendour. The development from the seven islands to the megacity that it is today, a lot has already been written and said about the city. A peninsula or island city as it is called, is the highlight of this chapter. The water terrain of the city.

The book ‘Soak’ by architect-activists Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, talks a lot about respecting the rich aqueous terrain of the city of Mumbai. They raise a question on our century long practice of cartography. An in-depth study from Mumbai’s first ever map to the recent ones is made by them, which shows a timeline of surveyors that took to make an accurate map of Mumbai. The city always had a changing terrain. The British who took to surveying the city, initially they even measured the water expanses between the seven islands as Bombay was known to be. Each developing connections in their own way. This is where the issue lies, they question why do we even draw this definite boundary between land and water everywhere? Why do we try to define only land as habitable? Is it all about land and land value and real estate? The practice of mapping shows as water a separate entity, and land as the valued possession.

“As designers we advocate approaches to water that accommodate rather than control its complicated nature approaches that do not position water as inevitably separate from land, as blue separate from brown. Water challenges us to consider ambiguity as a condition to embrace rather than erase. Water constructs a keen awareness of time through its absence and its presence; it draws us into a sectional world, an appreciation of depth.” – Interview for Places Journal by Anuradha Mathur & Dilip Da Cunha

The questions raised further are in numerable, is the element of water given as much respect in development? But we are forgetting one of the most important things, in the World Architecture Forum talks in Netherlands, Mathur said that water maybe somewhere, but wetness is everywhere. It is ubiquitous in nature, which is what we must be aware of. It creeps through cracks, it soaks, and it settles, it leaks, wetness is a quality that is not even understood properly today. How can we define such a transitional and abstract quality of water? Just maybe how we defined, how we made tough sea walls to push away the sea water, or how we mapped the boundary of a river to only limit between these two lines.

Is that all really true? Have we thought about how the landscape changed between monsoons to summer? They point out that on a rainy day we might not even see a boundary, that limited horizon line might just be a blur. This is the problem from centuries ago, none of the mapping practices ever thought to map a piece of land according to how the water landscapes change during monsoons. This is what has cost to so many cities losses through disasters like flooding etc. But water flows, it rises and falls, it seeps and soaks, it is stagnant, it forms ripples, it expands, it crashes into waves – it is a dynamic component. However we have made it into a static one that will only be defined with the line we draw it to follow, we think it is under our command to shape its nature.

15

“It takes a considerable effort to enforce firm ground anywhere, but it is particularly difficult to do so in an estuary, the primary ecology of Mumbai. Unlike deltas where rivers reach into the sea, estuaries allow the sea in. As such the rise and fall of the sea is not restricted to a coastline but is carried inland on a gradient that takes with it not just predictable tidal levels but the complexities of the world’s oceans where the unexpected reaches beyond the horizon and often beyond control. Here the war against the monsoon is also a war against the sea.”Soak

An estuary is the place where the river meets the sea, which means freshwater meets saltwater. This often forms the most fertile piece of land around it. Half of the city is filled with creeks and rivers that meet the sea at intervals forming an asset to the city, which remains unknown. Through their exhibition they tried to draw attention to this fact, that during the monsoon the city doesn’t flood but just becomes into the estuary it always was naturally. It is nature’s play of taking its form back. Of claiming her rightful territory.

‘An estuary demands gradients not walls, fluid occupations not defined by land use, negotiated moments not hard edges. In short it demands the accommodation of the sea not the war against it…’

Soak is an appreciation of an aqueous terrain. It encourages designs that hold monsoon waters rather than channel them out to sea; that work with gradient of an estuary; that accommodate uncertainty through resilience, not overcome it with prediction.’ – Soak

16

Fig. 7 Timeline from Bombay to Mumbai

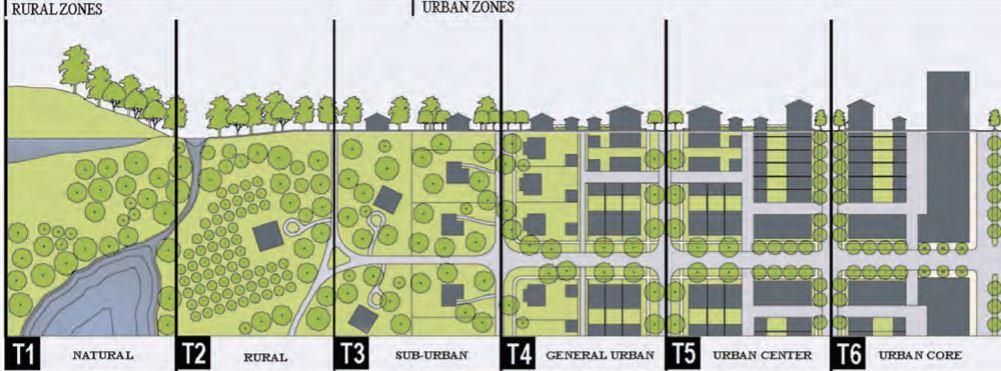

Their experiences are documented through a series of sections and elevations of the city.

The most important aspect to mark water is the topography of the land, the slope is what defines its flow. Hence they map out the land parcels, and correspond the sections on it. The concurrence, of monsoon waters and land is what must be documented, this will be kind of like an eye opener to the public as well as planners, as well as the government. This would help solve a lot of future prediction catastrophes that we might face.

“Is this time of water and watery imagination a moment to re-invent our relationship with water? Is it a time to look to the past, present and future and ask if in seeing water somewhere rather than everywhere we have missed opportunities, practices and lessons that could inform and transform the design project? What role has representation and visualization played in confining water on terra firma? Can we look at projects in history and projects emerging today – cities, infrastructures, buildings, landscapes, artworks – with a cultivated eye for water that rains, soaks, spreads, and blurs?” –Design on the Terrain of Water

With Mathur and da Cunha’s sectional techniques and iterative process, there is an experiential richness and temporality that simple orthographic projections and remote imaging cannot convey. These are the processes that would help us design with water for future potentialities. They express that the experiential gain of walking around photographing and studying the sites, is something no drawing or book could explain.

Fig 8. Mumbai water narratives through a sectional lens

17

1.3 City on the Water - A movie by Charles Correa, 1975

This short film is a documentation of the city of Mumbai in 1975. It was created by pioneer architect Charles Correa. It is named correctly on Mumbai since 300 years ago seven islands were joined by the British to make a trading port, which made it from Bombay to Mumbai. This is was them planting the seeds for an extraordinary future.

It talks about how Bombay grew phenomenally, attracting people from all over the country, and staggering amount of initiative, energy and imagination anything new tech, in Asia came first to Bombay. Due to its magnificent harbour, it soon became one of Asia’s finest port. This city had soon turned into the ‘nerve centre of the nation’s economy’. All the growth of the city through the post-colonial era was through the harbour that Bombay hosted. All new technologies came to the country through this port city. Good skills services exchange through here.

Nearly half the revenue of India came from Mumbai. The mill lands started developing near the Eastern harbours where trade to occur easily. With expanses of Cotton Mills booming, the workers started needing settlements to live close by, thus they started living illegally near the mills, around stations, near waterbodies on empty lands.

From 1975 till today 2020, these settlements have just kept increasing, almost all land and sea edges are lined with slums occupying acres of land.

Figure 9. Ships docking in the Port

Figure 10. Girgaon Chowpatty beach

Figure 11. Floods in monsoon (1975)

The British had set patterns for development when they ruled, after they left those were not altered and continued. The Eastern edge of the city was reclaimed into the sea, stretching out far and wide and as the map developed it soon was defined, The western edge was almost untouched by the British, which stayed almost organic boosting with development till date!

18

“Stretched into the Arabian Sea - Bombay lies, a great metropolis”

INTERVIEWS

Interview with Dilip Da Cunha – Pennsylvania, USA

INTRO : Dilip da Cunha, an architect and planner, has taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Parsons School of Design and Harvard University. He is currently Adjunct Professor GSAPP at Columbia University. He and Anuradha Mathur have published various books - Mississippi Floods: Designing a Shifting Landscape (2001), Deccan Traverses: the Making of Bangalore’s Terrain (2006) and Soak: Mumbai in an Estuary (2009), and co-editors of Design in the Terrain of Water (2014). Da Cunha’s new book The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2019. Mathur and da Cunha are currently working on a book and exhibition titled Ocean of Rain.

Interview:

- Disagree with the history of Bombay, the story of seven islands is a farce. How do you count seven islands? If you think of the sea rising falling and breathing, if it defines a ground is not necessary the idea of islands. It is an estuary. Sea is not the only edge.

- Make a decision, you must give up the idea of an island, it is a plan driven view of land with a surface. Sea does not have surface, when the rain is falling is it on a surface? Sea becomes an entire part. Plan is a very land centric. The sea does not have an edge

- Hydrological phenomenon, sea is constantly evaporating, precipitating

- What is site? Not a geographic space, it becomes a situation in time?

- Challenge what is happening in Chow patty? I don’t see flood, I don’t see a Mithi River. These are constructions that came up in 2005, it is nallah not a river, created to some extent as an overflow to the reservoirs the British built. It came from the Earth, the water rose.

- Rain soaks the ground and rises.

- Give up the notion of an edge, a lands edge. How do you define the past will define the present. People are land centric. Extend the edge in reclamation

- In soak they say it is not an island, it is an estuary.

- Not talking about inhabiting a surface, but a zone of wetness – from clouds to aquifers, there is no surface.

- Many farmers live in an ‘ocean of rain’, don’t look at floating not as floating on a sea, but swimming in a depth of wetness

- Sea surface – in the language of land; language of water is wetness

- Chose – colonial past and post-colonial past? – Mumbai in an estuary

- Ganapati in Chowpatty – clay idols made with wetness. – Idols made from mud of tank bed, then immersed back in tank – clay to clay – cycle of wetness –different modes of water appreciation, drying of idol – can become a practice to focus on.

- Informal living in Bombay – the live with a wetness, fishermen’s dwelling – mud adobe hut. Ways to negotiate wetness – inhabiting the sea.

- I see the scope – we need to be more inventive how we will, a broader concern, embrace the flood.

19

- Interview people – give them the possibility of another way of looking at something – situations where you can draw fresh water from salt water

- Aquifers underneath – building a sea wall? Does not register the sea already is coming inside

- The sea does not have an edge, people would say there is a freshwater well in the middle of saltwater

- Construct an alternate vision, play out sections, rising and falling intensity of wetness

- The sea surface coming inside the city

- Rain does not have to exit from the city, there is a field of backwaters – a place where you have monsoon and the sea mixing, you can go out a mile in the sea and there would be freshwater

- A temporal phenomenon

- Estuary as a rain ecology – it is not the mouth of the river, but RAIN and TIDE.

- SEA + MONSOON = Rain Ecology

- Permeability – the water channel is obvious in section, not in plan. Section in depth from aquifers to clouds

After land and water, the old demon builds castles in the air. (The Hindu 15.09.18)

Interview of Dr.Roberto Rocco – Delft, Netherlands

INTRO: Roberto Rocco, PhD, Associate Professor of Spatial Planning and Strategy at TU Delft; Section of Spatial Planning and Strategy, Department of Urbanism in Netherlands. He is currently a faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment of the Delft University of Technology. He recently worked on editing the book titled – “The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization”

Q: The Netherlands is a classic worldwide case study on Floating buildings and its response to the sea, do you feel it is the ultimate paradigm for hydrophilic sustainable design with water?

A: No, I think there are better solutions of designing with nature.

Q: Are callous construction techniques like land reclamation responsible for serious issues that cities are facing like coastal flooding?

A: No, they do not affect flood control in cities, but land reclamation can be very damaging for the environment (fauna and flora).

Q: For developing countries like India who are already combating with large problems, is this an investment of the present or should they act after a few decades?

A: It is more expensive to act after urbanisation has taken place. It is best to act now and prevent problems, designing with nature

20

INTRO: Debi Goenka an environmentalist, he is the Executive Trustee, Conservation Action Trust. He tries to spearhead the issues regarding the conservation and protection of the environment. He has pioneered several successful campaigns to protect the natural environment. Some of the most notable success stories have been the protection of mangroves, the protection of the Borivili National Park, Mumbai The Conservation Action Trust is a registered non-profit organization formed to protect the environment, particularly forests and wildlife.

Q. According to studies, the issue of rising sea levels is a major threat to coastal flooding in Mumbai, what other factors do you feel are contributing to this threat?1 response

A. The destruction of wetlands - mangroves, mud flats and salt pans. 2. Extraction of ground water and the construction of multi-storeyed buildings leading to sinking. 3. Continuing reclamation.

Q. Is Mumbai facing problems like flooding and loss of ecosystems due to callousness in development of urban infrastructure? For instance the land reclamation of the coastal road is it the reason for environmental damage?

A. Yes, very much so. Even the Bandra Kurla complex was built after destroying the mangroves.

Q This week Mumbai faced severe flooding and extreme loss of decade old trees falling from their roots, do you feel this will only worsen in the upcoming years? Is there any way to environmentally combat this problem? The only way is to stop the destruction of our natural assets, and decongest the city.

A. What part of Mumbai’s water ecosystem do you feel is the most adversely affected? Almost all our natural water bodies have been polluted, contaminated, filled up and destroyed.

Q. Could you suggest any possibilities of solutions that can be designed that can be used to rejuvenate our lost ecosystems and create a city with a great blue green infrastructure practice?

A. We should start with protecting what we have, and cleaning up what we have contaminated. We need to plant mangroves in areas where they have been destroyed such as the 500 acres of land off Malad Creek. We need to use our natural wetlands and constructed wetlands for sewage treatment.

21

Interview of Mr. Debi Goenka – Mumbai, India

1.5 PERSPECTIVES

The interviews with three professionals with tones of experience, gave a new perspective to looking at the water. Whereas some very radical views, and some eye openers they all are an important part of further analysis of this dissertation.

The perspective shown in ‘Soak’, iterated by the author himself Dilip Da Cunha is important in understanding the ubiquitous quality of water. If we look at it not like a boundary but a mingling of various ecosystems we would have far better solutions at hand. Whereas upcoming infrastructure is strongly declining what we already have, it’s time to act up. The countries like Netherlands who are the ‘water experts’ lived for years building sea walls and dykes but now experts there talks about adapting nature based solution strategies to adapt to the upcoming problems.

These interviews pushed me to find a middle ground, of how to increase the public connect to the sea, at the same time preserving and respecting it as much as land through solutions and strategies that benefit all.

1.6 ANALYSIS & INFERENCES:

o Trying to find solutions to not separate but include water in its most organic and natural way to create way for nature based solutions.

o Seasonal mapping, in the city during monsoon the landforms, and boundaries how different will our perspective be.

o The ubiquitous quality of wetness, how it surrounds us and how we try to avoid it whereas we must not make enemy of it, instead embrace as an opportunity for design.

o The importance of topography in understanding the flow of water, and how it cannot be imagined confined or restricted it.

o Importance of perception of experience of sectional observations of changes in tides, flows and seasons through documentation.

22

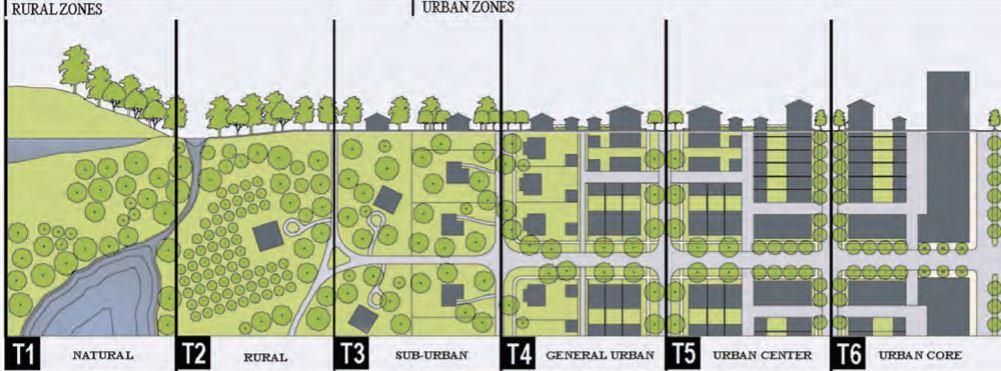

Figure 12. Sections of the city of Mumbai

23

DELVING IN THE P R E S E N T

24

2.1. QUALITIES WATER ADDS TO AN EDGE

Water is a prerequisite for life on our planet. Nothing can live without it. The history of water connects the cells of our bodies and all living creatures on earth to the oceans, rivers, icecaps, rain, and with water as it reliably pours out of the taps and, equally reliably, disappears down the drain. It moves, it flows it rises in highs and lows. The hydrological cycle of water is what defines the natural flows of almost everything.

Urban waterfronts are interface between city and water bodies of sea, river and lake. The host city maintains visual image as well functional characteristics of it.

Water is one of the most important elements of survival, and undoubtedly, for urban growth. And that’s why whenever we see traces of ancient cities, business centres, and the growth of modern cities, we see their unequivocal connection with water. But somehow, this thread snapped somewhere in history.

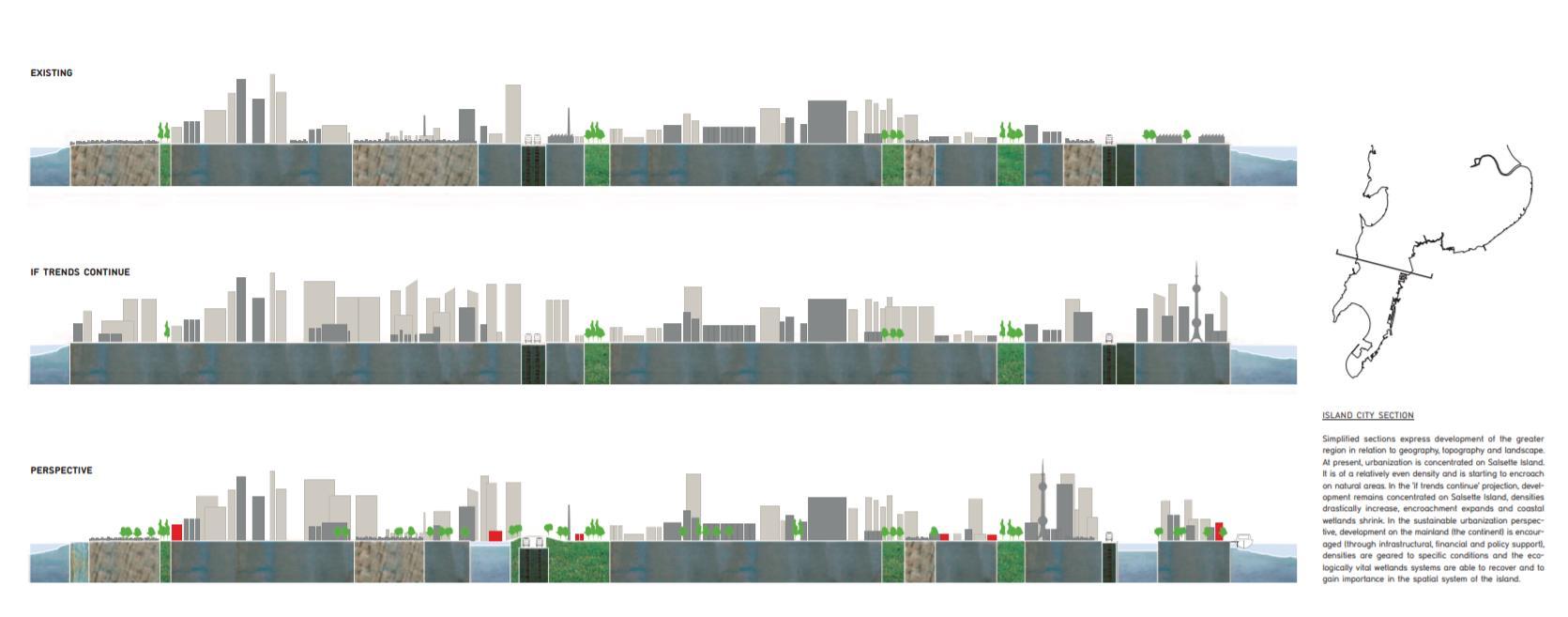

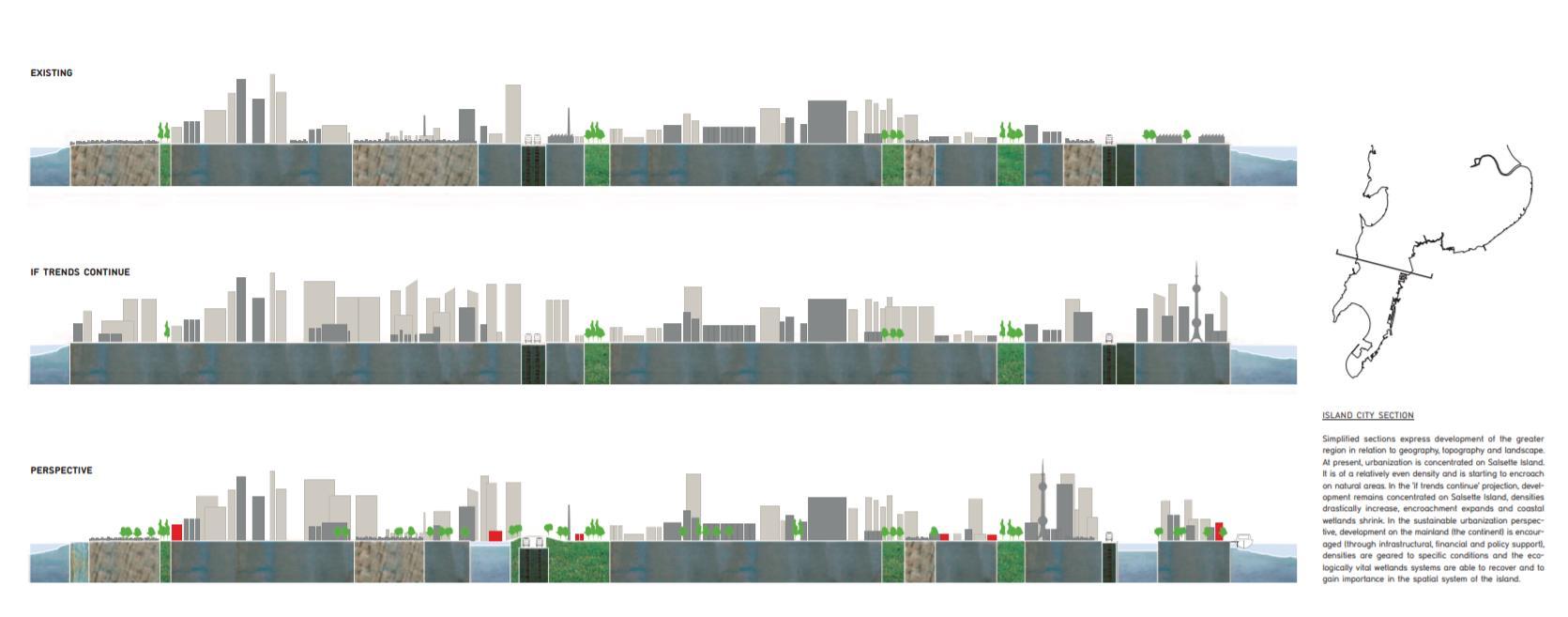

Figure 1. Evolution of waterfront development

It’s high time that we think of water as the driving force of urban development, which includes the context, topography, ecology, and the people living in cities.

This approach, known as “Water Urbanism”, opens an avenue leading to the sustainability of the new age, where we care for nature and solve urban issues by creating a synergy. In the age where many cities worldwide face natural disasters regarding climate change, resiliency matters the most. Water urbanism, thus, provides a unique toolset to the architects to make a resilient future.

Figure 2. Elements for waterfront development

25

We now see a break in the symbiosis between us and our surroundings. Why is it that urban life halts when we face seasonal floods which we know return every year? And in severe cases, like the flooding of Mumbai in 2005, why do all our protective measures fail? And at the same time, our rural population still can sustain their lifestyle in times of seasonal floods as they still maintain that connection. Water urbanism kind of points out this irony and urges to take measures from micro to macro level to establish that connection again.

As urban habitats continue to be governed through fragmented and disconnected processes, policies and departments will provide a path forward for urban regeneration that is based on integration to enable future generations to reconstitute their essential relationship to water and acquire meaningful ways of dealing with urban infrastructure.

The balance is established between nature and social life for a sustainable development of cities. Urban natural water elements play an important role in the establishment of this balance. Water is the most important planning element which is comfort of human physical and psychological. In addition, it brings existing environment in a number of features in term of aesthetic and functional. One reason for the importance of natural water source in urban area is aesthetic effects which are created on humans. These effects are visual, audial, tactual and psychological effects.

Figure 3. Effects of water as a planning element in an urban area

The primarily power of attracted people on waterfronts is visual landscape effects of water on relaxation. Throughout, designs related to water takes over motion and serenity factors. Moving water adds vibrancy and excitement to a space. Stagnant water creates the mirror effect in its space as a visual.

26

In Mumbai a city with water on almost all its sides, has all kinds of water ecosystems. It has a beautiful coastline, so a sandy shore on sides from Juhu to Chowpatty in South Bombay. Rocky shores on Haji Ali and Bandra interfaces, whereas a completely different mangrove system on Airoli or Sewri sides. Although different, they react in similar ways. They merge during the monsoons and often turn Mumbai into intertwined ecologies of an estuary. Our land and ecology are formed considering the fluidity of the elements, but in development practices we have often neglected the water terrain, and still are continuing to do so. Water Urbanism is a bold step to evolve from that.

If we try to impose infrastructure, problems like water-logging, water scarcity, etc. plaguing our city will begin to grow more and more sinister. What water urbanism proposes is to intervene by merging with our environmental factors, not impeding them. That changes with the cyclic aspect of nature. If developments are made looking at that it would create solutions for a lot of upcoming issues in the city’s fabric.

2.2 POWER OF A WATER FRONT IN URBAN ENVIRONMENT

1. ‘Place’ making = Urban blue green space + people

An urban waterfront has a special place in the modern resident’s heart because it connects them with nature. An urban water edge can enhance the association of its city with water Fostering people’s interaction with the water-land interface, lends it a distinct character. Hence, equitable access to urban waterfront if ensured at all times, proves fruitful.

In doing so, preserving the heritage and historic fabric of the city’s urban waterfront and its past connection with water should also be considered. A mixed-use development plan, celebrating the rich history, along the urban waterfront can make the place vibrant. An understanding of the broader context of how the society is involved in and around the urban waterfront area helps create inclusive spaces. This in turn fosters an area that is conducive of a plethora of socioeconomic activities. In order to develop and maintain this dynamic nature, these cities designed optimum and equitable public access.

2. Collaborative Governance

Developing an urban waterfront sees diverse sets of actors and organizations (Government, Private, Public, Services) come together. They are directly or indirectly dependent on this space and identifying their roles and interests at the inception of a project can be useful. Involving them through innovative and interactive governance mechanisms, like the multi-stakeholder engagement (example Bandra Carter Road) is valuable for holistic and inclusive transformation of any urban blue-green space.

A more bottom-up and participatory approach, with city leadership buy-in, might help in removing such road blocks, speed up approval process, and create mutual benefits for all stakeholders.

Collaboration between local government, planning and development authorities, and residents can help pave the way towards an inclusive and active urban waterfront management. Setting up of interdepartmental bodies, like the special purpose vehicle

27

or waterbody improvement trust/group, can also facilitate smooth collaboration between stakeholders.

3. Environment always at the heart

Ideally, urban waterfronts should be developed keeping nature and ecology at their heart. In the cases when they are not, it can prove to be detrimental to the surrounding environment like in the case of Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati riverfront. It is important to remember that the development of public spaces should happen in close association with environmental restoration. The proposal of any such regeneration project should take environmental and climate change impacts into consideration at the ideation stage itself, as it can influence the project cost estimation. Projects should aim for low impact and resilient design which will most importantly improve the quality of water and help adapt to any future climate vulnerabilities.

4. Financial viability and sustainability

Financing is one of the major challenges that urban waterfront projects face. Since the nature of most such projects is ambitious, and local governments lack the required funding, in many cases secondary sources are sought. The operations and maintenance cost of the project also play a key role in deciding the financial viability of such large-scale urban developments. Innovative funding options and partnerships involving the private sector have been tried by Singapore, Seoul, London, New York, etc. They feature a combination of phased land sale and value capture, TDR and zoning incentives that helped the local government generate revenue through the private sector. The financial success of urban waterfront projects lies in identifying multiple avenues for revenue generation. Combinations of direct (incremental revenue generation) and indirect (environmental and social) benefits should be considered together as return on investment.

5. Organic Transformation

Any regeneration project is time intensive so aiming for short-term benefits might not be sustainable. The development should seize the benefits of as many low-hanging fruits, but long-term vision is indispensable. Instead of a masterplan approach, a strategic vision which frames the shared community interests for the place are more holistic. Although a masterplan (a statutory document) for development helps by safeguarding it from political cycles, but its rigid nature hinders organic transformation that is incremental and flexible to the changing needs of the city and its people. A shared vision is adaptable and can be implemented gradually, starting with small changes, guiding developments as the transformation of the urban waterfront gains credibility.

Sustainable development of urban waterfront involves a number of physical and social considerations. 1A balanced approach to urban waterfront development, where ecological, environmental and water concerns are addressed harmoniously along with development can accrue multiple benefits to people and ecosystems while generating economic dividend for Indian cities.

28

1 https://wri-india.org/blog/reinventing-urban-waterfronts-indian-cities-five-ideas-step-way-forward

29

2.3 UNDERSTANDING THE LAND WATER EDGE

IMAGEABILITY OF EDGES

“The disruptive character of an edge must be reckoned with” – Kevin Lynch, Image of the City 1960

“

Edges. Edges are the linear elements not used or considered as paths by the observer. They are the boundaries between two phases, linear breaks in continuity: shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls. They are lateral references rather than coordinate axes. Such edges may be barriers, more or less penetrable, which close one region off from another; or they may be seams, lines along which two regions are related and joined together. These edge elements, although probably not as dominant as paths, are for many people important organizing features, particularly in the role of holding together generalized areas, as in the outline of a city by water or wall.”

Water bodies, the breathable spaces that majorly encompass the void in the urban fabric are naturally the key to healthy living environments. Right from the birth of the waterbody, it undergoes traceable morphogenesis over a period of time, witnessing diverse environmental conditions and user nature. With the steady increase in the density of the urban fabric, these breathable zones have become unnoticeably sizeable. This obscured the vision of the water bodies amongst the tall, dense skyline of the cities. Though the large water bodies occupied a major part of the skyline, small ones were left as the un-noticed ground in the middle of dense urban figures

The freshwater bodies that have a higher impact on the surrounding urban life tend to have a part in the lifestyle of the people. They are generally the major water source for the population and are traditionally a place of congregation. Farming communities of India are majorly dependant on freshwater bodies such as river for potable water & irrigation and worship them as a part of their living culture.

Saltwater bodies such as lakes are the recreation points for the population. Apart from having a rich saltwater ecosystem, it enhances the micro-climate and opens up opportunities for various water affiliated activities and entertainment. Lakeside recreation is considered to have a rich cultural impact and tourist attraction that would further provide economic support for local maintenance. Thus a flourishing neighbourhood is achieved.

“While continuity and visibility are crucial, strong edges are not necessarily impenetrable. Many edges are uniting seams, rather than isolating barriers, and it is interesting to see the differences in effect.

Edges are often paths as well. Where this was so, and where the ordinary observer was nor shut off from moving on the path then the circulation image seemed to be the dominant one. The element was usually pictured as a path, reinforced by boundary characteristics.”

30

2.4 DUALITY OF THE EDGE

There are two sides to an edge. Webster's II New Riverside University Dictionary defines edge as: "A dividing line or point of transition, the line of intersection of two surfaces of a solid." The water's edge is a dividing line between two zones: land and water, water and sky and the two sides of land as a river or harbour dissects a city. It can also act as a point of transition for two spaces, a line of exchange, a line or a plane of intersection that separates and joins two elements.

The waterfront is the edge that divides land and water. Historically, cities around the world have increased their footprints by infilling the water for more land. In some cases, the water disappears at the end of the process. This one sided expansion at the edge causes cities to overlook the value of waterfront.

Water, sky and land are the three main components of the earth. When one views the city from the water, the land divides the sky and from the water. However, when viewed from the city, the water and the sky merge into one at the horizontal line. From the sky, water and land share an adjoining line. Water, land, and sky knit with one another in three dimensions.

Types of Edge Conditions:

Besides being an in-between zone, an edge can in fact act as a zone with its own identity.

A Distinct Line of Separation

The waterfront acts as a city's boundary, there are cities surrounded by water-islands, or cities with inner harbours or dissected by a river, and lastly, cities with water on one edge-coastal cities. Harbour front, riverfront, seafront, lakefront, canal edge, all have different boundaries. The water's edge is a dividing line to separate the viewer from the city or the dense built form from the openness of the water. The skyline then becomes every city's urban identity. The containment of a large body of water allows people to look at a city or a building from a distance. Driving along the Bandra Worli sea link in Mumbai, one perceives a contrast between the openness of the water and the density of high-rises. These simultaneous views of different characters change constantly along the edge of the city.

Figure 4. The boulders form a boundary

31

An Adjoining Line

The horizon line joins the sky and water. In addition, the body of water on the surface of earth links the continents while the edge separates land from water. Therefore, a port city has a dialectic identity of being individual and being a part of a collective system.

A Line of Exchange

The water's frontier is the threshold where goods

Figure 5. Buildings adjoining sea and people from different parts of the world enter and exit. It is a line or an interface of exchange. The ports and harbours of Mumbai are the reason for it flourishing so much in trade since the colonial times.

An Inhabited Edge

One can interpret the dimensions of the water's edge and thus in a large scale the edge can be inhabited. Buildings by the edge of canals are often built up to the edge and let the base of the building open up as arcades or so. Activities like eating can happen at the edge.

Figure 6. A busy harbour for exchange of goods

The Changing Edge

Sometimes, the edge condition can be a blurred separation or an ambiguous zone since the edge changes constantly. The beach exemplifies this idea and the process of urban infill for land made cities creates a changing shoreline. Due to the land reclamation through centuries in Mumbai the edge has constantly kept changing and evolving. In such a densely populated city where even an inch of land has value, reclaiming land from the sea and developing it is a phenomena observed often, yet again the edges are set to change for the coastal road project.

Figure 7. Dynamics of an edge

32

2.5 PUBLICNESS AND THE WATER EDGE

Building Form and Public Space on the Edge -

A city should conserve some of its water's edge for developing active open spaces and protecting it from inaccessible privatization. View corridors should lead to the water where the public can easily gain access to the edge from the city.

Some well-developed and emerging relationships between cities can be analysed by understanding the city's association with water. We can differentiate city typologies based on their historic and current connections with water, such as cities on a river, harbour, bay, estuary, delta or ocean shore. Many cities have originated near or on the edge of water bodies, because water is essential in terms of sustaining life, having historically enabled trade and commerce, and, today water is still an essential part of cities and their transformative development. The sustainable design of water’s edge public spaces is an integral part of the realisation of the cities of tomorrow. Historically, trading posts and routes have facilitated cultural exchange and interaction at levels surpassing other spaces. Areas alongside harbours and docking points have been fertile ground for the display of commercial, social, architectural and cultural hierarchies. These dynamics are continually changing and, as populations and economic relationships alter over time, the physical manifestations remain visible in the architecture, buildings, structures and, most prominently, the design of public spaces.

Figure 8. Factors affecting water’s edge public spaces – Density, diversity & design

In association with physical manifestations, virtual aspects (i.e. online versions of reality, animated connections, gaming strategies, virtual landscapes and technological reminders) allow us to understand and appreciate changing architectural forms. Public spaces are constantly evolving due to people’s thoughts, views, interests and use of them. The nature of associated private space is also changing, from primarily retail and commercial to mixed use, recreational and technological.

33

P K Das writes in his book – On the Waterfront, about this edge changing and becoming a public space.

“The seafront is the largest open space and the most attractive and crucial feature of Mumbai’s landscape. For millions who live in this crowded city, the waterfronts, be it at Marine Drive or Chowpatty, Haji Ali or Worli Sea Face, DadarPrabhadevi, Shivaji Park, Mahim, Bandra, Juhu Beach or Versova, are the only major open spaces apart from few parks and maidans. People flock there to catch a breath of fresh air, to soak in the golden light of the setting sun in the far horizon or to share a moment of togetherness with a loved one, Bollywood style.

Open spaces along the seafront and other public spaces have been an integral part of Mumbai’s landscape. Old municipal gardens such as Victoria Gardens, now known as the Jijamata Udyan, and the Hanging Gardens, continue to be popular with morning walkers and picnickers. Big grounds like the Cross, Azad, Oval, Cooperage and Shivaji Park have hosted historically significant social movements, and today, are sites for community celebrations, political demonstrations and meetings, sports and cultural programmes, so integral a part of the public life of the city. One of the distinctive features of Mumbai’s coastline is the presence of many forts in Vasai, Bandra, Mahim and Worli which, unfortunately, are in a state of total disrepair at present. Temples, such as Mahalaxmi, Babulnath, Walkeshwar, the dargah at Haji Ali and the churches of Mount Mary and St Andrew’s at Bandra are important landmarks. Along the coastline of Mumbai, and attract large numbers of people within and outside the city.”

34

Figure 9. Haji Ali Bay fishermen’s boats

Figure 10. Sassoon Docks fisher’s wharf

2.6 THE URBAN TRANSECT METHOD

“A transect, in its origins (Von Humboldt 1790), is a geographical cross-section of a region used to reveal a sequence of environments. Originally, it was used to analyse natural ecologies, showing varying characteristics through different zones such as shores, wetlands, plains, and uplands. For human environments, such a cross-section can be used to identify a set of habitats that vary by their level and intensity of urban character, a continuum that ranges from rural to urban. In Transect planning, this range of environments is the basis for organizing the components of urbanization: building, lot, land use, street, and all of the other physical elements of the human habitat.”2

Analysis by transect was first used by geographers and naturalists to describe and understand the workings of natural systems, including human habitats. In this spirit, in addition to providing a place-based approach to planning regulation, the rural-tourban transect aims to better integrate environmentalist and urbanist values.

Urbanists often argue that well-meaning environmental regulations hinder the dense, contiguous form of traditional towns and cities, causing development to spread out over greater areas. But the relatively dense cities and towns urbanists advocate may conflict with environmental advocacy for uncompromised riparian corridors and animal habitats in even the densest human settlements.

Environmentalists also speak of a need to “green the city” which urbanists worry will damage the pedestrian continuity associated with successful urbanism. In general, urbanists believe the integrity of human settlements should be given equal standing with that of the natural world.

Environmentalists, on the other hand, believe that human settlements must conform to natural ecosystems to function correctly. They argue that cities must incorporate green strategies and technologies to reduce environmental impacts and improve the quality of life. Although many people take positions between the extremes, new tools are needed to reconcile these differences. By considering urban and environmental values on a regional basis, transect-based planning may be a step forward in this area. Its advocates argue that by reducing the impact of sprawl, it may enable both dense human settlement and healthy environmental performance. It remains to be seen how far the opposing views can be reconciled in practice, however.

35

2 https://transect.org/analysis_img.html

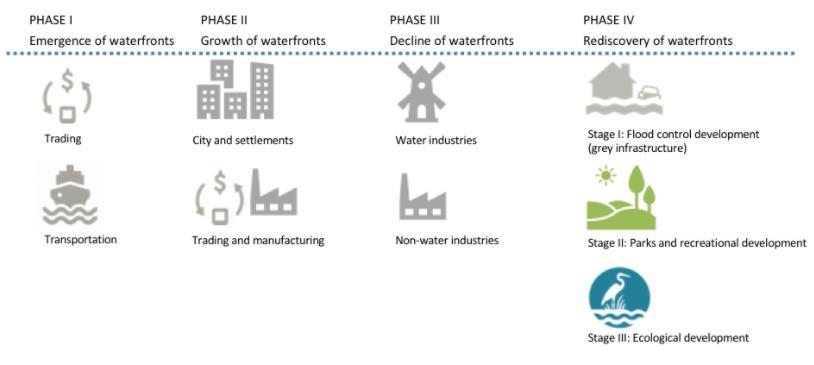

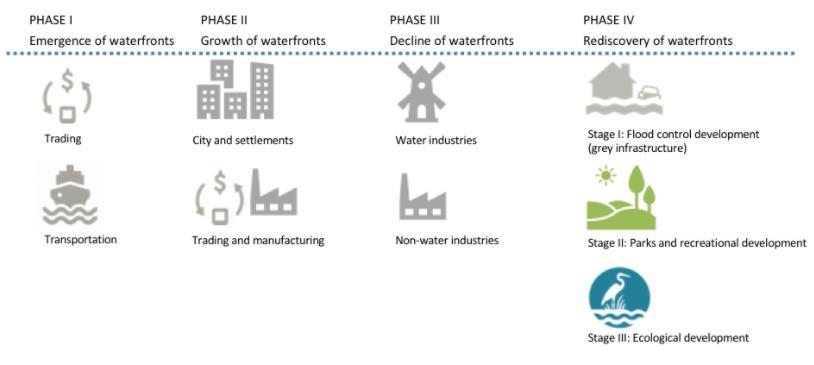

Figure 11. The Urban Transect of six zones

In ecological analysis, the transect method may be used to understand how physical and biological systems interact to create living environments. Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature (1963) used this technique to describe the eco-zones of a typical stretch of land from beach to inland bay. The transect may also be used to generate detailed environmental assessment. Similar techniques may be used to understand the character of urban districts.

"A town is saved, not more by the righteous men in it than by the woods and swamps that surround it."

— Henry David Thoreau

A transect is a cut or path through part of the environment showing a range of different habitats. Biologists and ecologists use transects to study the many symbiotic elements that contribute to habitats where certain plants and animals thrive.

Quadrat & Dissect in Nature

The environmental assessment of a site requires the identification of typical ecozones (or habitats) by means of a Synoptic Survey, which has two analytical protocols, the Dissect and the Quadrat. A natural transect is shown at the top. The Dissect (left) is a sectional cut that includes what is on the surface of the ground, above the ground (including the microclimate) and what is underground (the humidity and water table). For the Quadrat (right), a normative area is delineated within which all the flora and fauna are quantified. From this sampling, the characteristics of other similar zones can be assumed.

- Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company

- Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company

36

Figure 12. Landscape ecological transect

Figure 13. Axonometric of the different transect zones

2.7

RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF WATER LAND INTERFACE IN INDIA

Charles Moore in his book “Water and Architecture” mentioned that the key to understanding the water of architecture is to understand the architecture of water –What physical law governs its behaviour, how liquid acts and reacts with our senses, and most of all how its symbolism relates to us as human beings.

The nature of water can be termed as a fundamental soft element which is a sculptural medium unsurpassed in its potential to make the most of its form, transparency, reflectivity, sound, movement, refractivity, and colour.

The Architectural response to water is not only limited to the physical built form but it is also interlinked with the psychological response. Hence, the responses are in both ways where one is interrelated to the other. Further, the Architectural response can be manifested in many ways like Physical, Spatial, Visual, and Sensorial. It can be classified that these responses are tangible and intangible.

The physical and aesthetic properties of water give it a unique mythical-religious potential and therefore it has played an important role in myths and religious rituals.

The Rig Veda proclaims:

‘‘These waters are pure and auspicious (which cleanses); these are the medicines (healers, physical and spiritual) of all; these waters help growth and provide prosperity for all."

Hinduism believes that water has spiritually cleansing powers. Water from rivers is considered sacred, but the seven rivers in India namely the Ganga, Yamuna, Saraswathi, Godavari, Narmada, Sindhu, and the Kaveri have been accorded a greater sanctity than the others. Holy places located on the banks of rivers (Srirangam), coasts (Rameswaram, Tiruchendur), confluence of rivers (Mukkoodal) carry a special significance, where major festivals are celebrated. The waters in these sacred places are considered great equalisers people of different castes bathe together.

37

Figure 14 & 15. City of Varanasi, having a religious connection to River Ganga

Waterfronts are termed as those areas, which are located in an urban context having direct contact with water or adjoining lake, river, or harbour. Various activities are prevailing on the Waterfront which keeps the interface active. These activities can be classified into various types such as mixed-use, recreational, working activities, historic, cultural, environmental, residential, etc. It is said that Waterfronts provide a city level place for public enjoyment and engagement. These waterfronts provide an ample amount of visual and physical access. Cities do want a waterfront that serves multiple purposes such as a place to work, to live, to relax, etc. Therefore, Waterfronts contribute to aspects like Social, Cultural, and Economical.

Waterfronts are perceived very differently in the Indian context and have a diverse context. During ancient times, waterfronts in the Indian context were never celebrated as a recreational public place. Waterfront is not very well emphasized in the Indian culture if compared to the western concept of such waterfronts. Water and religion are intricately woven in the pattern of lifestyle of Indians.

Along with that due to the subtropical climate, the preference to the waterfronts is more on the socio-cultural aspects such as the bathing rituals. In India, many cities have flourished on the banks of waterfronts i.e. seafront, riverfront, and lakefronts which are marked in the map. All these cities have their own identity achieved due to the dominance of water as a core element. So, it can also be said that the city structure as a whole responds to the waterbody in a certain manner whereas, on a micro-level, the elements which are physically related to water have also evolved in the Indian context. In the Indian context, it is believed that rivers are sacred, the kunds and stepwells have shrines and idols of God, lakes were used to offer prayers and worship water as God. Therefore, layers of activities along with built form typologies and their architectural responses exist altogether with the current era.

“

The Ganges still retains a religious significance. The development of the Hindu religion in the I n d u s Valley endued the Ganges with a sacred role, and River cities, such as Benares, Hardwar and Allahabad, became important centres of pilgrimages and sacred festivals. T h e riverside temples and the steps (the Ghats) leading down to the water provide both access and a visual link between water activities and the sacred buildings.” –Aquatecture (book) – Anthony Wylson

The main feature of the waterfront can be said as the physical accessibility to water that also leads to a specific response to the water edge. Therefore, the particular architectural elements such as Ghats, Ovara (a gateway to access the water body), step-wells, and bathing pavilions can be said as the evolution of built form with architectural conceptions along the water edge. So, it can be said that the water edge also reflects the evolution pattern respecting all the socio-cultural aspects.

38

Historically, cities across the country expended resources in the creation of some of the most beautiful public spaces around water, the most prominent being the ghats of Benaras, the stepwells of Gujarat and the kunds of Rajasthan. These constitute some of the most vibrant, dynamic, diverse and multi-faceted manifestations of spaces within the fabric of traditional Indian cities. Emerging out of India’s climatic and socio-political and cultural composition, these spaces were public, inclusive and active participants of the daily life of people. They offered citizens opportunities of engagement at several scales for a multitude of activities. They were designed and carefully calibrated. They were spaces of social recital, of public participation, political deliberations and lived experiences that formed the base of celebration of life – Living waters museum

Indian rivers are mighty and have accredited for development of civilisation from the Indus valley, to the mythological significance of gods performing religious activities, to historic empires being formed at their banks. Cities flourished and grew only due to their proximity to a waterbody. Even ones in difficult terrains like landlocked ones develop due to presence of lakes or underground sources or even manmade tanks.

Architecture forms related and responded to water as though it is considered man’s best friend and worshipped as their sole source to survive. As times passed the development devil took over and they starting slowly forgetting the resource. Rampant growth led to a point that today it is neglected and growth is not only stunting but negatively affecting.

39

Figure 16. Collage showing religious significance

2.8 ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS CITIES

Points Ratnagiri Alleppey Haridwar Panjim Mumbai

Area 72. 6 sq. km 42.6 sq. km 12.3 sq. km 8.27 sq. km 603.4 sq. km

Kind of edge(s) Rocky edge meeting sea, at high terrain

Type of land use

Mainly Agricultural, residential. Less commercial

Sandy coastal edge + Soil loamy edge

Mixed use of residential & commercial, as well as lot of tourist activities

Soft soil edge meeting river freshwater

Mainly religious, commercial and residential

Impact of water edge

Livelihoods depend on it, agriculture and fishing are main occupations of the city

Developm ent through the years

Organic settlements through the years expanding not directly touching

Public Relations Commercial relations for sustaining themselves through livelihood

Development of the entire city has been due to its connect of backwater rivers in and out of the city

Organic growth, developed lot in recent years, keeping buffers to edges of various kinds

Close connect of individuals due to tourism & shelter in house boats in back waters

Utmost imp is its religious significance, flooded with tourists all year round, activities relate

Contained development due to high terrain and river flow, labyrinthine growth

Worship and daily ritual / festive relation with river water

Sandy coastal + rocky edge Sandy, Rocky, Mangrove, hard concrete, mudflats

Mix of commercial, administrative, residential & leisure

Planned developed as capital city due to inlets making its ports active, increasing settlements

Denser growth towards edges, lesser inwards, a balanced organic development.

Commercial relations to help the city develop through waterways

Mix use of ALL residential , cultural, commercial, industrial, recreational

Became largest port from colonial times, due to water on all sides. Trade caused it to flourish in dev.

A colonised development, of extensive reclamation and developments touching the edge

Earlier imp for trade, now only fishing, rest all edges for recreation. East for port activities

Hazards / Risks

Very less risk of getting affected by rising levels, or floods since dev is not close to edge.

Few chances of flooding in case of worse scenario, but water managed well through channels

Few chances of flooding, only in disaster like situations for river overflowing since close.

Less risk of flooding through coastal, since organically developed and altitude factor

High vulnerability to coastal floods & rise, especially in monsoon due to callous development & reclamation Diagrams

Table 1 – Comparative analysis of various cities having a connect with water

40

I. RATNAGIRI – Maharashtra

About: Surrounded by the Sahyadris (India's western ghats) and the Arabian Sea, The scenic beauty of Ratnagiri is mesmerising. The region is blessed with hills, beaches, rivers, hot water springs, forests and waterfalls. It is a jewel of the Konkan coastline due to its lush green and blue landscape.

Elevation: 77 M