Dear Readers,

Halloween is over, but the trees have begun shedding their leaves to reveal eerie skeleton bodies. I once wrote an article for post- about struggling to enjoy other seasons just as much as autumn. It has to do with my love of being cozy, of being indoors, of spooky things, and— perhaps in largest part—of the colors on the trees. Even though I know they’re the same leaves, just reduced in chlorophyll, their transformed and multicolored versions always feel like special visitors. While they’re here, all manner of magical things can happen. So, it’s always hard to see them fall, and the satisfying crunch of them beneath my feet is bittersweet. They’re certainly not gone yet, but each day I feel myself taking inventory.

And yet, as I find every year, life doesn’t halt when the trees are bare. Pivotal moments and memories take place in winter, spring, and summer— some of them even wonderful. I can’t reverse-hibernate through the warm months to save my waking hours for my favorite season, and despite my current mourning, I know I wouldn’t want to. Each has its unique charms, and each is necessary. Counterintuitively, this realization helps me savor autumn all the more. Acceptance of what’s to come, knowing I’ll be okay no matter the season: This is how I let go of the urge to

count the remaining leaves.

This week, our writers are also figuring how to be amidst change.

In Feature, Dolma grows a personal historical archive, and Sasha confronts ambivalence about one messenger of the world’s present moment: The New York Times. In Narrative, making pasta for loved ones is a constant for Ana, and it takes an adrenaline-racing experience for AnnaLise to accept the birthdays to come. In Arts and Culture, Ann celebrates the link from past to present that is Minecraft, and, on a roll this week, Sasha links poetic legends Poe and Pitbull. In Lifestyle, Elaine adjusts to life not spent in constant dancing motion, and Sara dissects just a couple of moments from one morning. In addition, we have a crossword from Alayna full of friends from the farm, and in this week’s postpourri, we have a comic strip from Selena where we encounter a few new pals!

It’s my last semester here at Brown. As I graduate in December, the end of autumn seems laden with greater significance this year. After this, the coming seasons are among the only things I know to expect. Even if the inevitable coatings of snow, spring allergies, and summer heat are not always preferred, they are at least familiar. All I can do is cling to their comforts as I proceed into the great unknowns of the future. That and, of course, read post-; I hope that you will do the same!

Finishing up here,

Daniella Coyle

Lifestyle Managing Editor

by sasha gordon

It took seeing one friend repeatedly reassure another that nothing was wrong and then, in their absence, proceed to describe everything that was, in fact, wrong for me to realize that I’m a very direct person. Obviously, I’ve told half-truths and stalled a confrontation for another day, but in a relatively deceit-free way— is it obvious I’ve been told that I’m a pretty terrible liar? I was, however, unfamiliar with stating one thing and doing another, outside the realm of the cartoonishly evil and obviously untrustworthy. In real life, this wouldn’t happen. And so, while I happily discuss how the curtains “were not just blue” in seminars, I tend to believe that good-faith actors truthfully tell me what they’re doing.

One such good-faith actor in my life was The New York Times. I’m not sure when I first encountered it, but certainly by age 12, I was a regular visitor of the website. There was just nothing quite like typing in the 10 letters of “nytimes.com” and seeing its reassuringly familiar crest at the top of the page, beneath

which a list of sections boasted wide-ranging coverage, from U.S. public schools to foreign policy to public health issues. Now I was able to browse and inform myself independently, instead of waiting for someone to explain something to me, or, heaven forbid, trawling Wikipedia. Reader, I spent upwards of an hour each and every day perusing the Times’ archives, admiring its staff writers, and absorbing its opinion section, all in the pursuit of being a gold-star informed citizen. And it was exciting! Compared to the other outlets I had access to—kid-friendly news sites, whatever National Geographic editions remained at my school library—the NYT was obviously the top banana, and I, by proximity, felt a little prestige rub off on me.

The print edition began to arrive on my doorstep in the middle of COVID-19’s doldrums, and only served to increase my consumption of this sacred text. COVID itself increased my reliance on its work—now I had an impetus to read the paper, not just for self-edification, but

Illustrated by Jenny Chen

to protect my health and that of those around me. More of its coverage began to inform more of my life, and I don’t know that I was reading much other news. I heard some NPR and other local news on KQED, and I might have seen some NBC News when I watched my mother get ready for work each morning, but neither of those were “real” in my eyes. Total supremacy of the Times. Bored in a high school class? Pull up the Magazine section. Can’t think of an essay topic? See what’s under the “Breaking” tab, or randomize something out of its stillbroken search function. The Times was always there for me, for schoolwork just as much as for entertainment, and I could trust it. It was the ship that carried me from headlines like “BIDEN BEATS TRUMP” to “ONE MILLION” to “TRUMP STORMS BACK,” and it was unsinkable.

Ok, Sasha. Sure. You read the Times. It was awesome or something. But you’re not really convincing me that I should care that you cared. Fine! Be that way. Here’s more: Hand in hand with my commitment to reading each word of the daily paper was my long-standing commitment to cynicism. Not skepticism and its raised hackles, but cynicism and its stony belief in bad-faith actors. Ask my mother, my first-grade teacher, my pediatric dentist—they would avow that I was a cynic through and through, and had been since I could speak. Never taking anything for granted, never assuming the best outcome was the most probable, never carefree—young me understood cynicism to be something like discernment. Having an immediate cynical approach would help me sort the good from the bad and stop any kind of deception from occurring, right? When people I looked up to in my life remarked on my nascent cynicism, it felt like a nod to my intellectual achievement. It was praise, in a

way. Combine this with the seventh-grade need to do battle with annoying boys in history class and bring something interesting to the Model UN practice session, and I got the idea that cynicism made me “informed” and that being “informed” helped me be more cynical. It’s still unclear to me what “informed” means or what the real value of being it is, but if I didn’t think too hard about it, I could simply leave it there. Eventually my mega-brain was so full of NYT that I could discern good from bad and trustworthy from dishonest at a glance, and never again doubt what I had already classified as informative. I had so much information. I was informed, I promise. Don’t think less of me, I’m not uninformed! I’m up to date! (With what? For who?)

This may have been a foolish attitude, but until June 5, 2025, it served me.

You may not remember this particular day, a Thursday broadly unremarkable. That evening, in the 22 minutes between arriving home and my father announcing dinner was ready, I opened the NYT app on my phone in the hopes of finding something for us to chat about. Boy, did I ever. Splashed across the front page (or the top of my screen), in all caps: “TRUMP AND MUSK SHATTER ALLIANCE.” The striking part of this was the formatting. Historically, the Times reserves this all-caps banner (or “hammer”) headline for truly momentous news. “MEN WALK ON MOON” should provide a sufficient example. This is an atypical presentation of a headline, and it should strike you as odd. Between “ONE MILLION” COVID-19 deaths in the U.S., “TRUMP STORMS BACK” headlining his reelection after felony conviction, and “TRUMP AND MUSK SHATTER ALLIANCE” describing a series of unfriendly tweets, one of these things is not like the others. It was a profoundly bizarre experience to see these events given similar import by this newsroom that had previously never led me astray.

If you had read beyond the headline on this day, or honestly on any of the days in the following week, you would have seen dozens of subheadings and features and clip reels all agonizing over the Trump-Musk “meltdown.” An army of reporters pressed into service to catalog tweets, index “Truths,” and deliver pithy jabs about the “bromance.” For days, the airwaves were flooded with stories primarily reporting on social media interactions surrounding this breakup and sensationalizing the drama. As the Times referenced, “The girls are fighting.”

In this world where the executive administration is powered by the raw hunger of swarming locusts, in this world where the Times has explicitly recognized that a reliance

on overwhelming press channels is essential to their rapacious tactics, in this world where a fake story about Elon Musk’s hypothetical Super Bowl ads received more attention than the actual struggle of people losing support from USAID, it’s pretty damn weird that the Times would spend a week rehashing and reheating this stale tidbit that is, at base, celebrity infighting. Piece after piece from the Times editorial board implored the reader to look past Trump’s circus of misdirection, and instead see the reality of the dismantling of government services, while the Times itself hosted the circus as its big-top headliner. It published opinions to this end at least twice (in February and again in that very same summer), but you wouldn’t know it from its simultaneous coverage of the failing relationship.

There must have been something more newsworthy that day in June, right? A way to discuss this breakup from the perspective of the American people, or the policy they were fighting over, or anything other than sheer spectacle. The Times didn’t seem to think so.

I felt betrayed. This was the paper to which I had near-total devotion. Its word was law. I savored its print edition every day for years and labored over each paragraph (I even braved The Athletic, reader) in an attempt to absorb some kernel of something into myself. Legitimacy, perhaps. I think that’s what the cynicism and quest to “be informed” were for.

My cynicism, however, turned out to be bolstered primarily by this specific tool that I could use to rebuke everything. I had a magic dictionary of infinite knowledge at nytimes. com. I had a compulsive need to “be informed about….” Attempting to understand the second half of that phrase, the one that starts with “about” and ends somewhere still unknown to me, only led to frustration.

I knew that cynics, with such a strong sense of doubt armoring them, couldn’t be blindsided or misled. I knew enough as a cynic-in-training to ask “Why are they saying this to me?” and “Who’s funding this source?” but I didn’t know that one could say the right thing while doing the opposite. My reliance on immediate cynicism only went so far as to address the message, but perhaps not its delivery. Only in such a blatant example as the Trump-Musk breakup did I begin to see that.

Once I saw it, I began to see it everywhere. It was in social dynamics and false advertising, sure, but it had even become embedded in the fabric of my hometown. Last summer was the first real span of time I’d spent at home since Trump was sworn in, and I was feeling real whiplash. I love the Bay, the evershifting landscape of sea to forest to sea again, and the slow rise of SR-120 into the mountains, but

I did not love returning to it. Sure, I’d been dissatisfied with it before—SF’s pressurecooker high schools, social climbing, and emphasis on success were tough as a teen—but the torrent of AI-wrapper companies and their associated political maneuvering was new(ish). There had been iffy apples but they had felt like exceptions. Apparently they weren’t. The Bay being a top-down liberal hotbed was convenient, until it wasn’t financially advantageous for a select few CEOs. Apparently I wasn’t a Bay Area cynic in the areas where it mattered. I believed my qualms regarding its odd value structures were anterior to the immutable reality of some beautiful, glittering Bay that I now see was temporary. I thought the political landscape was as sturdy and dependable as the physical one, somehow physically intertwined and inseparable—but the politics can change. This shook my attachment to the physical reality, too. A slap in the face.

I now see that my cynicism mostly taught me to assign value to an entity on my first encounter with it, and apply very rigid categories of “reliable” and “unreliable” that would break before they would flex. I had decided that my friends were good and thus wouldn’t lie, the Times was the way to be informed and legitimate, and perhaps the Bay, even, was somehow incorruptible beyond its ever-present social climbing. I was then able to be skeptical of people or other press institutions I didn’t necessarily get on well with, because I had a shining beacon to compare these murkier ideas to. Once the bulb died in the beacon, I was adrift. I no longer know what to do with cynicism—or I don’t know what to do without it. I don’t know what it is to “be informed,” and I don’t think it’s a real phrase.

I do not believe there is a conspiracy at the heart of this. I do not want you to believe I do. I believe the Times is, at base, a forprofit enterprise that operates much like its peers, generating revenue from our clicks and attention. I wouldn’t class this as rage-bait, but I will say it’s shitty. That particular week of press in June was fodder for the Trump machine that the Times claims to work against. Feeding the dog that bites you, or whatever. I’m still grappling with this internally. Moral people read the news, right? And good people know what’s happening around the world. I don’t know what either of those sentences really mean right now, but I guess I’m aware. I call my father, tell him about an earthquake in the Philippines. The Times says dozens of people died.

What does it mean to learn from preservation and reimagination?

Letters to my future self, sketchbooks of crayon drawings, and origami works lay on the family decor shelf, assembled for the purpose of having connections to my childhood. The letters, written in curvy handwriting, are filled with ideas of what kind of person I thought I would grow up to become. The sketchbooks carried attempts to articulate the world as I saw it then. The origami flowers were folded with patience. Grounding me where I started, these materials create a valuable archive for my life.

In my sociology class this semester, I have been tasked with handling a folder of letters from those incarcerated in Rhode Island prisons. With these personal works, I am to create an archive of theirs, ensuring that I build their narratives off how they have chosen to vocalize their reflections, rather than others’ interpretations. Focused on a collection of letters from those currently incarcerated, I am able to dwell on their handwriting and articulate their personal troubles, struggles, and moments of resilience within the justice system. Alongside this assignment, this class has aimed to mark the importance of preserving such personal materials to allow for the retelling of a story beyond present verbal inquiries. From the mass incarceration issues within our country to the clear discrepancies in court systems, my professor calls us to discuss the flaws within the current system of law. Tasked to read and analyze current work on the jailing and prison system, I am assigned to write journal entries weekly about what I learned in class. This journal, in itself, is a form of archival work where the content and analysis is wellpreserved, viewed through my current self’s understanding of the system and its ties to my personal life.

I had often viewed archiving as an act of storage, a means to keep things from disappearing. Looking at the constant display of written books in my hometown museum, I found archiving to be full of the sentiment of striving to preserve, not accounting for what it can do in the present as well. But as I engaged with the art of archival practice in my first sociology class at Brown, I realized that archiving is not merely to preserve, but also to create. This

act of authorship is to decide what deserves to be highlighted in remembrance. Giving those who aren’t typically heard a platform to preserve their voices is a form of resistance to the confinement of today’s societal norms.

Many of the incarcerated people we work with in class, who allowed the creation of an archive about their lives, wrote letters about more than what the system has recorded about them. Instead, their files tend to document their humanity, including humor, reflections, and heartbreak. The system likes to place statistics on their stories as a means of accounting for efficiency and performance-based legitimacy. But these letters enable a place for self-expression that extends beyond the walls of confinement, confirming their presence within a world that has rendered them dismissible.

As my professor mentions the role of archivists in the field of sociology, I am invested in the notion that artists and archivists share the ability to reimagine the past, to make it lively and legible in more personal ways. Oftentimes, when learning the history of someone’s life or an event, books depict facts, statistics, and overarching narrative associated with it as a means to produce an efficient and fact-based description. Archives, however, give breath to the stories. Instead of using a detached outsider perspective, archives let me hold the ink and feel the hesitations of the person behind the

with objects that make

by dolma

document. Reading through someone’s writing has a touch of humanity that textbooks and articles often skip over. When an archivist is able to preserve the documents and materials of an individual’s life, we are brought to humility, an awareness that the stories we translate are not ours to control, only to hold.

Archiving can be seen as reconstruction. As an individual holds onto memories, histories, and materials, they have resources to collage an arrangement of something already lived. This

make up our personal archives

by Ellie Lin

reimagined space can be articulated through care. By caring for what has been left behind, we can stop diminishing the original story and promote learning through preservation. The ability to listen and to allow materials to speak their own stories breeds authenticity, providing resistance to the urge to edit someone’s experience into something “neater” than what it truly was. These acts of humility resist societal expectations in favor of authenticity, and amplify the original voice without

changing it. To learn from this reimagination is to understand how preserved fragments of an individual's life can amplify their original voice.

The opportunity to write a letter or create a document about one’s own beliefs and ideas is a freedom that gives one the respect and ability to preserve their own stories that they are entitled to. Being trusted with the responsibility to hold materials that are considered precious to others has shown me how easily stories can be lost when not given the patience to evolve. The act of archiving is restorative and gives control to the storyteller. The ability to capture the essence of who a person is based on their own creation of writing or artwork evokes a more personal connection. This allows the person to be heard in new ways.

This process has changed how I see my personal letters and items from childhood. I once thought of them as clutter and relics of a self

I had outgrown. But looking back, I can see them as evidence that memory can be a kind of valued art. The old Justice tank top I would wear every day in third grade reminds me of the endless playground adventures I would take on, from monkey bars to slides. A sketchbook filled with uneven self-portraits reminds me of the worlds I would face in my head, usually reflecting whichever Disney Channel show I was obsessed with at the time. These objects don’t feel like past relics, but instead conversations I continue

to have with myself through different mediums. Each document acts as a version of me that is stuck in the past, but still informs who I am. To archive one's life is to trace between the past and present, always in dialogue with our own past.

When I see the shelf at home, those childhood artifacts feel vivid, resisting being sealed off by time. They are not static memories, but living archives. Like those who are unable to amplify their voices because of confinement, I am learning to speak with those same fragments of who I was to guide who I will be.

Maybe what it means to learn from preservation and reimagination is to understand that stories don't end where they are confined. They are able to expand and adapt. The archive is never truly finished because, as a living artwork, it teaches us how to understand the past while leaving room for what continues to be revoiced. What we learn from preservation is the ability to recognize what we hold, whether it be scribbled notes or photos, and continue to tell a story if we take the time to listen.

Some of the items in my current personal archive:

Prayer ring - worn everyday and everywhere, this gold and metal ring is a personal fidget gadget that holds the weight of my unspoken wishes.

Sony ZV-E10 - with its lenses scratched, my camera catches the light to preserve small moments of my environment and the people that fill up my life.

Black claw clip - always attached to my bag, holding my hair together when things get too overstimulating.

Beaten-up blue water bottle - dented yet persistent, the water bottle has been a part of every place I have traveled to.

Thrifted mixed-metal watch - this piece of jewelry, useless in its ability to count time because of its broken face, now measures the traces of its past owners and the moments of my present days.

Describing a continuity of experience, these archival pieces enable a meeting between my past and present. As I expand my archival collection, I hope to continue to carry these small reminders that who I was still shapes who I will be.

by ana vissicchio

My three friends squabble next to me, all packed together in our 100-square-foot kitchen. They’re all making a quick lunch; I’m making pesto from scratch. I’m not sure why.

Despite growing up on pesto pasta, I’ve never made it from scratch. I embarked on this endeavor with memory as my only recipe, ushering my friend Amina into my car to accompany me to the grocery store and hunt for forgotten ingredients that had just popped back into my head.

Pine nuts were never in my mom’s pesto. She swore by walnuts. I remember her telling me that walnuts were good for my brain because of their unique shape—a little pea-sized noggin. She’d tell me that sort of stuff all the time: that carrots were good for my hair because the two words sounded the same (c-hair-ots), that blueberries were good for my eyes because they resembled my own round blue irises.

Amina and I stood in front of the nuts section and stared at the teeny, tiny, $15.99 box of pine nuts.

I grabbed the walnuts.

We left the grocery store, narrowly avoiding a collision with the bollards in the Whole Foods parking lot, and returned home. I’m now back in the kitchen, staring at the NutriBullet that’s overflowing with a mushy, vibrant green substance. My mom would always use her food processor, but I’m working with what I’ve got, the Bullet left over from the girls who lived here before us.

I hold the container out for Amina to try. She dips her pinky in, tastes, and immediately sticks her tongue out. I follow suit. It’s a typical garlic flavor, but it’s stronger and much more bitter—10 times more bitter than usual. I return to the chopping board.

I guess I do know why I’m making pesto. Graham’s visiting tonight, driving four hours from New York to stay the weekend. This is our favorite meal, and I want to surprise him by making it from scratch.

Graham and I met in the winter. We watched that season’s first snowfall together. That night, he walked me home, so worried I’d get sick since I was wearing ballet flats. Whenever we looked

Graham cooks like I do—simple ingredients and no recipes. One of those chilly winter nights, he made a sauce his dad always made: just half an onion, a stick of butter, and crushed tomatoes. A few spices. We sat at his kitchen table. We were awkward and smiley, and to be honest, I don’t even remember what the pasta tasted like.

Two weeks ago, my parents visited for Family Weekend. They bustled out of their big truck, wrapped in coats and scarves in the 60-degree weather, carrying bags and bags full of homemade veggie chips and, at last, jars

rummaging around, asking me why I had fruit that wasn’t organic and which side of the freezer was mine. She lined up the eclectic containers of pesto—from reused jars to little Pyrex dishes with red lids, all labeled with my name in Sharpie—along the side of my freezer.

On Friday night, I offered to cook my parents dinner. They came over to our apartment and ambled about as I prepared carrots, onions, cauliflower, and a big pot of soup. The soup was one of those dishes I would whip up all the time, and as usual, I made up the recipe as I went, without any measurements or ratios. In an

attempt to impress my parents, I made way too many dishes at once. While I wasn’t looking, my mom would turn off a burner when a pot was about to boil over, or dial down the oven when she was afraid of the teeniest amount of char.

We sat down at our dining room table and ate a meal I’d cooked for them for the first time ever, save for the strange desserts and mudpies I’d made for them as a kid.

The evening after they left, I checked my fridge and pantry and found nothing fresh or interesting to eat. I unraveled a rubber banded bag of pasta, brought a pot of water to boil, and took out a jar of my mom’s homemade pesto.

After much trial and error, with my hands and kitchen now smelling like garlic, the pesto was finally at a stage that I’d label as edible. I packed it away: in repurposed jars, and little Pyrex containers with red lids, all labeled with my name in Sharpie. I lined them up on my side of the freezer; I now had 12 receptacles of pesto at the ready.

As Graham pulls into the driveway, I follow the foolproof steps that always bring me peace due to their comforting routine. I boil the pasta, drain it in a colander, and use the same hot pot to defrost the frozen pesto, watching it transform into a luxurious sauce when mixed with the starchy pasta water. I mix in some peas to my mom’s plain and simple recipe because I know they are his favorite vegetable.

Every morning growing up, my mom would ask me what I wanted for dinner that night. I can’t recall a time when I didn’t answer back, “pesto pasta!” She would chide me that it’s not good to have pasta every night, but, most of the

time, she would cave, and when I came home late from a student council meeting or cross country practice, a large pot of pesto pasta would await me, more than enough to feed an army, let alone our little group of three.

As I finish up the dish, Graham saunters around and helps me out, washing miscellaneous spoons and used pots. We sit down and enjoy our favorite meal in each other’s company. After not seeing each other for a while, I soak in how good it feels to complete a labor of love.

Every Sunday, my friends and I take turns hosting what we call family dinners. I’m always amazed at how Amina can whip up a casual nine-dish meal or how Lucy roasts vegetables to perfection. We sit down after a long week and eat a delicious dinner cooked with love by our dearest friends, and it is simply the best feeling in the world, my favorite part of the week. It’s my turn next Sunday, and I think I know just what to make for everyone.

Senior year has been a stretch of college that's felt different from the rest, and I have come to realize that a lot of that comes from having a space of our own, a little taste of adult life. When I'm homesick and hungry, I can whip up my favorite childhood meal in no time. When I'm getting a bad case of the Sunday blues, I can rely on my friends to be there for me in the form of a warm, home-cooked meal. And when I want to show the ones closest to me how much I love them, I turn to the kitchen, giving way to ingredients and recipes that remind me of home, ones passed down, improvised, or rediscovered; the act of cooking is a love language in itself.

by annalise sandrich

What’s scarier than aging?

For one thing, falling out of the sky. Plummeting to the ground in a lifeless hunk of metal. This I discovered on my 20th birthday, sitting in the copilot seat on a runway of the Oakland International Airport, imagining for the first time all my mother’s greatest fears.

It had been a while since I’d enjoyed a birthday. Matter of fact, I’d come to dread them. The big ones especially—16, 18, 20— held disproportionate weight. I disliked birthdays the way I disliked New Year’s, the end of a semester, the scheduled end of anything, really. Days that force you to confront the fact that time is passing whether you want it to or not. Days that force you to confront what you have or haven’t accomplished in a given time frame. Days you’re supposed to celebrate, but in reality they terrify you with their supposed importance—the fear of time

from my early childhood

once possessed a weightlessness, aided by bouncy castles and sugar highs. When I was a kid, my mom would go all out on parties. I’d select a theme and she’d see to every detail meticulously. For my eighth birthday, my mom typed out “Hogwarts acceptance letters” (invitations) on parchment paper, burned the corners by hand to make them seem more mysterious, and stamped a homemade wax seal onto each envelope.

The one thing my mom would never let me do was fly.

I have wanted to pilot a plane ever since I was 10 years old. It seemed the ultimate expression of freedom, a way to translate the magic of the middle-grade fantasy novels I obsessed over into real life. To be able to take yourself anywhere, to see the world from a high vantage point, to soar over it all.

Shortly after moving to the Bay Area, I soft-launched this idea to my parents by suggesting that we take a family ride on

one of the seaplane tours just one town over in Sausalito. We passed the cute, little, yellow planes sitting on the water every drive back from San Francisco. Various agencies advertised short voyages over the bay—the opportunity was to be a passenger, not a pilot, but it still held appeal.

It was an instantaneous and obvious no from my mother. Decades ago, her uncle passed away in a gyrocopter accident. Any airborne vehicle smaller than a commercial plane has been offlimits to every member of our family ever since.

Which was why the headset covering my ears and the control yoke in front of me was almost harder to believe than the fact that I was newly 20 years old.

While I was no stranger to excessive birthday melancholy, 20 was an especially frightening number: a new decade of life, a symbolic marker of my introduction to real adulthood. For my final act of teenage angst, I adopted a woe-is-me character the week leading up to my birthday, almost reveling in the dread of the arbitrary end of my youth. When my parents asked if I wanted to do anything to celebrate, I gave disinterested responses.

And then, sitting at the kitchen table during those last few days of being 19, my mother told me she had booked a pilot lesson for me in Oakland.

We drove together to a part of the Oakland Airport I had never seen before and met the instructor, barely older than I was, dressed casually in jeans and a T-shirt. He claimed to have over a decade of experience, so at least one of us had achieved their goal of flying at age ten. My mother waited in the lobby while we traversed the airfield, passing dozens of planes that seemed to get tinier and tinier the further we walked. We finally arrived at a blue-striped Cessna with a cute propeller on its nose, smaller than the Subaru my mother and I had driven across the Richmond bridge to get there. Adorable, if not very confidenceinspiring. The sort of plane that looked like a scaled-up toy, the kind you see in cartoons, usually talking. Not the sort of thing you really comprehend as a vessel capable of supporting the air travel of two adults (newly two twenty-somethings!) But I suspended my disbelief in order to suspend myself in the air.

Various checks had to be done before we could take off, a clipboard and a checklist of items that had to be verified and completed. I liked the clipboard. The clipboard was good. If anything, maybe not long enough. It suddenly struck me as strange that they’d let you fly a plane for just $200, a few forms, and a short waiver. Even if, as the twenty-somethingyear-old pilot instructor explained, this was technically supposed to be just the introductory lesson—the first in a long series of classes on the route to obtaining a pilot license. In theory, I was supposed to follow up and schedule more lessons, but it didn’t seem to bother my instructor that I was here as a one-off. He told me

we would sit side-by-side the whole time, two steering controls each capable of maneuvering us through the air. Reasonable.

So maybe the thing that actually suddenly struck me as strange was that they made planes this small in the first place. This thing was a Mini Cooper with wings.

I tried to pay attention as he explained all the dials and meters in the cockpit, the function of the various buttons and dashboards. But for today, all I really needed to know (and all I’d remember a year and a half later) was that pushing the yoke forward would tip the plane’s nose down, while pulling it back would point us up. The rest of the steering was straightforward: more or less left to go left, right to go right.

We waited for our turn on the tarmac. My stomach dropped a little, the instructor’s voice garbled as it pitched through the headset, him spurting jargon I didn’t understand to someone on the other side. I pictured my mother’s uncle, two decades’ worth of warnings against the exact undertaking I was about to embark on.

Turning 20 was the last thing on my mind.

But whether you think about it or not, whether you want to or don’t, you turn. You turn—left onto the runway, and then you pull the yoke back, nose tipped to the air, engines firing. One way or another, you leave the ground.

Tiny as we were against an endless sky, I could feel every bump as turbulence rattled us across the East Bay, shaking with the plane at every gust of wind. Our path was in my hands, save for the moments when we drifted off course and the instructor gently nudged us in the right direction.

Oakland is a good 45-minute drive from my house. More with traffic. By plane, that’s no distance at all. We flew over the San Francisco skyline, the iconic Salesforce Tower, the Transamerica Pyramid, made our way over to the shore, above the bridge—and to think I thought I’d already marveled at it from every possible angle. Across the water, I could spot the stretch of land where I knew my house must be one of the dots way down below.

A shaky flight, yes. But a magnificent one.

Shortly after I declined the instructor’s offer to do a flip, we began our return to Oakland and our descent to the ground. He handled the landing. My mom was there waiting once it was over. I haven’t dreaded a birthday since.

take a picture of that bird with a kodak

by Sasha Gordon Illustrated by Angelina So

Fine! Fine. You got me, okay? I said all week that I wasn’t going to write a piece that started with two lines from a song that unexpectedly has deep and personal relevance to me, cut to some narrative, cut back to two lines from later in the song, rinse and repeat. But here I am. It works! I get it now, and I’m a fan.

Me not workin’ hard?

Yeah, right, picture that with a Kodak Or, better yet, go to Times Square Take a picture of me with a Kodak

I love this. It’s so bad. It’s Pitbull’s first No. 1 single, “Give Me Everything.” These are the first lines of his most famous song. If you were hearing Pitbull for the very first time, these would be the first ten seconds of your experience. This IS Pitbull. And it’s bad, right? We know this. He rhymes “Kodak” with “Kodak” without even burying it deep in a fourth verse that never gets airtime—nope, it’s at the very start. “Kodak” rhymes with so many things. Blowback. So wack. Show track. Okay, maybe none of those are good rhymes, but I never said I was Mr. 305. The point, though, isn’t whether these are good rhymes or not. It’s the phenomenon of it all. Pitbull has told you what he wants to say, and now he’s telling it to you again, almost verbatim. Almost.

What if it was verbatim, actually? What would that sound like?

Mr. Mid-Atlantic, Edgar Allan Poe, wrote a number of poems that serve as examples. Fun bonus fact: Poetry is named after Poe. On the count of three, tell me the first thing that came to mind when you read his name. One, two, three: “The Raven.” Oh, hey! You too? Crazy. So. Poe’s first No. 1 hit single, 1845’s “The Raven,” is more similar to 2011’s “Give Me Everything” by Pitbull than you’d expect. Here’s the first stanza:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Poe uses “rapping” and “tapping” four times in just six lines. We hear the tapping, we have it described as rapping, the phrase is repeated, and then the narrator mutters this fact aloud. It’s a lot, and for me it entirely chokes the poem. Maybe my gripe with “The Raven” reveals my hamartia: I’m a worshipper of Mnemosyne, mother of muses, and in middle school I really thought I could memorize most of what you think of as the poetry canon. Reams and reams of poetry, at minimum. I’m still working on it.

I learned around seven stanzas of “The Raven” by heart—not quite the entire American canon, and not without struggle. Poe’s raven haunts the narrator with the “whispered word, ‘Lenore,’” but my raven muttered “rapping” and “tapping,” and later “chamber door,” incessantly. It would not let me be! I’m chugging along, reciting the familiar contours of souls growing stronger and imploring forgiveness, and then I splutter. Gently tapping? Faintly rapping? No, obviously, the adjective that comes later in the alphabet goes with the verb that comes earlier. Clearly, then, it’s “gently rapping” followed by “faintly tapping, tapping at my chamber door.” Pretty asinine mnemonics, I think. Poe does use internal rhyme in a generally pleasant, suspensebuilding fashion that I can appreciate, but my patience wears thin at times. In some Poe-ms, it feels like he left in two versions of the same line for the editor to cull. The editor never came.

“Ulalume” is a less famous Poe work, but it was the first one I ever read, and it still holds a prominent seat in my pantheon of spooky things. Poe skillfully weaves a world around the reader and pulls them along a dark path through forests of his creation, arriving somewhere deep and treacherous before they’ve fully realized what’s happened. It’s beautiful, glamorous, evocative:

The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crispéd and sere— It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year; It was down by the dank tarn of Auber, In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

Stunning, right? Poe lays out a big-picture description, a smaller detail of the scene, another part of the big picture, and a reason why that’s important too, just in the first four lines. Great stuff. It’s concise, immediately sets the scene, and already gives the reader key observations to chew on. “Ghoul-haunted”?

“Most immemorial year”? I knew I was in for a treat. Reader, I’m so sorry, but what I just showed you isn’t actually the first stanza of “Ulalume.” Here’s what Poe really published:

The skies they were ashen and sober; The leaves they were crispéd and sere— The leaves they were withering and sere;

It was night in the lonesome October Of my most immemorial year; It was hard by the dim lake of Auber, In the misty mid region of Weir— It was down by the dank tarn of Auber, In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

And it’s just not quite the same. Why do the leaves need to be “crispéd and sere” and “withering and sere”? Hearing Auber and Weir described twice in parallel to the same effect feels more like Poe is confused than writing intentionally. I like repetition, I like internal rhyme, but I get this little twinge of disappointment when I read “Ulalume” these days, wishing that someone had come in and just tightened it up a little. The argument Poe scholars make around this poem is typically that the repetition is in service of the poem being incantatory, almost hypnotic, and that the lines being repeated almost verbatim adds to the listener’s experience and sonic satisfaction. It doesn’t land for me. I try to recite it—not even

from memory—and it just sounds garbled. Twothirds of this stanza is direct repetition. Reader, please try reading this aloud:

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber, In the misty mid region of Weir— It was down by the dank tarn of Auber, In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

I don’t find myself enchanted. There is a kind of droning hypnotic that I do understand, but if that’s what Poe’s trying to achieve, he should honestly go harder. The published version feels like it’s primarily quibbling with itself, like Poe wasn’t really sure what he wanted to write. This duplication is present in at least two lines in all ten stanzas of “Ulalume,” and it weighs it down. Maybe, then, confidence is what is missing. “The Raven” is confident in its repetition, frustrating as it may be for those of us trying to memorize it, and “Give Me Everything” is unabashed—Kodak does rhyme

with Kodak, after all. I’m pretty sure Pitbull knows it’s bad, and “The Raven” is meant to be somewhat troublesome, but “Ulalume,” not so much. I enjoy the recitation of my abbreviated version of it far more.

I listened to more of Pitbull’s oeuvre for this piece, and found one more gem to leave you with:

Look up in the sky, it's a bird? It's a plane? Nah, it's just me, ain't a damn thing changed Live in hotels, swing on planes Blessed to say, money ain't a thang And he’s right. Plane rhymes with plane.

minecraft released the horse mob over 12 years ago. . . feel old yet?

by Ann Golpira

Illustrated by Julie Sok

During your young adulthood, the only thing more inevitable than acne is the three-week Minecraft-playing phase you’ll undergo at least once per year. For me, the game once again infiltrated my computer following the release of the 1.21 update this past June—the internal peace I gain from mining the same cobblestone blocks for hours on end is something years of therapy can’t even begin to rival.

It all started when one of my best friends and I started a joint survival world through the Hypixel server—a free-to-play, public Minecraft world home to a multitude of mini-games (even writing out the server name gives me vivid flashbacks to my early teenage years). I would stay up late into the night trying my best to recreate my Pinterest board’s aesthetic designs in the game, then wake up in the morning and continue the endeavor with my breakfast right beside my keyboard. My productivity was truly unmatched.

Returning to the game always induces a flood of nostalgia—I think back to the hours upon hours I used to pour into the game as a kid while playing with my cousin and the way those blocky, virtual worlds connected my real world to my cousin’s, despite us living in different states. I even remember throwing a Kardashian-level tantrum when my dad began enforcing a Minecraft limit of no more than three hours a day—which, looking back, was arguably for the best.

But the game seeped into my life even outside the realm of the program itself. From the ages of eight to twelve, my YouTube feed consisted solely of The Ellen Show clips (a

story for another day) and Minecraft YouTubers. My gateway drug was Stampy’s Lovely World, which followed an aggressively British Minecraft player who would build various mini-games and structures inside his “Lovely World.” At the beginning of each episode, Stampy (an orange and white cat whose design is forever cemented into my brain) would shout out a fan by placing their name in his “Love Garden”—an accomplishment just above a Nobel prize.

Later on, I discovered the wonders of PopularMMOs and GamingWithJen, an online couple named Pat and Jen who would experiment with mods, games, storymode maps, and more. While other kids were curled up watching Disney and Nickelodeon (although admittedly I did my share of that as well), I was propped in front of my family’s desktop computer watching these playthrough-style videos with the concentration of a surgeon.

The day Pat and Jen got a divorce was the day my childhood died. Still reeling from the death of their cat, I remember watching intently as they awkwardly explained their failed marriage to a YouTube audience of barely-showered preteens and avid Minecraft followers. Turns out Pat has since been arrested for a multitude of crimes (including assaulting a police officer, probation violations, and trespassing during a Jacksonville Jaguars NFL game), and even now, I gasp when reading the articles and judging his mugshot.

Throughout middle and high school, while I navigated the move from Minecraft YouTube to Netflix, I still found myself drawn back to the game. I continued playing with my cousin and later also found a friend group of Gamer Kids ™ to

supplement my adventures. Whether we played Murder Mystery, Build Battle, Bed Wars, or Sky Wars, Hypixel became the ultimate meeting spot for our afterschool hangouts.

The game—while undoubtedly still a meme—has served as a common thread and conversation starter with so many people in my life. Even now at Brown, I remember voraciously running through a Bed Wars arena during a late-night Mock Trial social event.

In a similarly sentimental domain, I raise the subject of Minecraft: Story Mode. Released as a collaboration between Telltale Games and Mojang Studios in 2016, this choose-your-ownadventure style game allows players to navigate the world as the character “Jesse.” The plot of the game’s first season follows the reconstruction of an old group of heroes known as “The Order of the Stone” (composed of Gabriel the Warrior, Ellegard the Redstone Engineer, Magnus the Rogue, Soren the Architect, and Ivor the Potion Brewer and Enchanter).

The team bands together to defeat the Wither Storm—but not before killing the game’s most beloved character, Reuben the pig. Reuben’s death forever remains one of the deepest, most impactful plotlines in all of cinema. Imposters like The Notebook and Dead Poets Society could only dream of evoking that same raw, human (and pig) emotion.

I tried rewatching the scene as part of my in-depth research for this article, and I had to throw my phone aside for a second to regain my composure. The number of edits set to depressing TikTok audios was honestly quite overwhelming, and I was forced to scroll

through Trisha Paytas compilation videos as a palate cleanser.

Another interesting lesson from my Minecraft days is the distinction of different archetypal players, whether that be the miner, the redstone inventor, the builder, etc. You can truly tell so much about a person’s personality by the role they take on in a Minecraft survival world—the information is arguably more useful than their MBTI. If you were the “aesthetic builder” archetype as a kid, you most likely have a multitude of saved Pinterest boards amidst your organized, color-coded laptop home screen, and there’s a very high chance you’re now concentrating in the humanities. On the other hand, the “crazy builder” archetypes—a.k.a. those who made Brutalist-style kingdoms and loot farms—are likely now majoring in some sort of STEM (I don’t make the rules, I just know the facts). If you were one of the kids who would break into servers and blow everything up with TNT. . .you're likely just as horrible and evil a person now as ever.

All in all, no matter the archetype, I've connected with so many people through a shared love of this game. Whether in the fleeting, comedic moments of a server chat or the lifelong memories I’ll cherish of me and my cousin frantically running from mobs and building luxurious bases, Minecraft holds so much nostalgia for me.

So, for anyone who hasn’t reentered their threeweek Minecraft phase in quite a while, I urge you to pick up the controller, play the YouTube video, or even just download the app once again. No matter how long it’s been, it’s something I don’t think I’ll ever grow out of—and that’s completely fine by me.

by Elaine Rand

Illustrated by Candace park

On January 28, the thought hit me. Or rather, I hit the thought, as if I’d been standing in front of it for a long time and had only just now had the bright idea to take a step forward into it: “What if I quit my ballet job?”

There were plenty of factors that brought me to the wall of “holy shit!” that stood in front of me. I’d been dancing with an injury, though not a major one: a midfoot sprain that was on the mend, despite feeling fork-tender and crunchy-boned all at once. I was working on a solo for a famous ensemble piece that I’d long pined to perform, but I wasn’t satisfied. I felt underrehearsed and understimulated, despite spending whole days at the studio, a common dancer gripe about our company’s piecemeal schedule. Yet, I found I had no desire to audition for other companies, where there would certainly be similar structural issues to those of my own. I felt the invisible shimmer of something about to shift. I just didn’t yet know what it would mean.

Ballet had been a constant for 21 years of my life, starting with creative movement classes at my local Indiana community center that evolved into structured ballet rehearsals six days a week, and spiraled outward until I arrived in St. Louis for my salaried position five years prior to that shimmer. Despite my dissatisfaction, the idea of retiring from the profession had not yet occurred to me. I did not know life without the constant pull back into the daily routine of maintenance, the anticipation of each upcoming performance, the rigor, the restraint.

I think of the world of ballet as an aquarium. The dancers are mermaids; they are only halfhuman, and much more special. They are mythologized and lusted after by those who live on land, who come to stare into the water and wish they could move with their grace. But, to maintain their magic, the mermaids must make sacrifices: They cannot walk, they cannot live on land.

As a mermaid, as a dancer, you live in a bubble with others like yourself, secluded from the world’s expanses. You can pay the sea witch and give up your fins and gleaming tail to gain your freedom, but there’s no going back. You can only peer in through the glass and watch with amazement as the mermaids that remain swim in spirals without you.

******

The change was in the air but not yet in my hands. I bargained with myself: “If I stay in ballet, I’ll dye my hair dark brown, but if I leave, I’m chopping it all off!” My 2025 Pinterest moodboard betrayed my preference, suggesting

endless images of shaggy pixie cuts. I was sick of pulling back my hair into a tight-coiled bun; I was sick of working under a contract that didn’t allow me full control of my appearance, of my body.

The contract came in late February, goading me to sign on for next year or to take my leave quietly. I hemmed and hawed, but I sensed what I needed to choose. I am not an impulsive person, so I knew that feeling an impulse at all meant something big. When I decided to leave, my fears—of identity loss, my peers’ judgement, my boss’s disapproval—popped like huge helium balloons. For the first time in what felt like forever, I no longer needed to hold my breath.

My throat caught when I told my coworkers I would be leaving in an impromptu announcement after our daily class one Friday in March. I sniffled through a little speech of thanks. But there were no great sadnesses in my retirement. My love for the art form never faltered, but little grievances (complicated workplace power dynamics, constant physical pain, the 16-mile drive to work every day) grated at me. I think I metabolized my grievances throughout my time in the company, so by the time it was done, there was no more sadness left to burn off.

That’s not to say there weren’t many moments of happiness in my time as a professional dancer. There was plenty of joy in movement, satisfaction in executing complicated combinations of steps, and mischief shared with my fellow dancers. But the label of “ballerina” was an archetype I had to mold myself to fit. The dream I had romanticized and longed for had started to feel like a burden.

Now, “ballerina” is not my label to claim. Maybe it never was: Its formal usage is only supposed to indicate a senior female ballet dancer of the highest rank. Me, I danced in an unranked regional company confined to a strip mall-addled suburb of the city it claimed to represent. I try to hold my pride for my work in the same hand that I hold all that it did not live up to. Out of the studio and back in school, I’m free to dance when I want to and not when I’m told to, to do the steps as I see fit, to live life unconstricted. I am relieved that there is no more of it.

No more corseted costumes that dig into my ribs or scratch at my lower back. No more orders to strip off my legwarmers so the front of the room can see my body at its almost barest. No more sitting criss cross applesauce on the sweat-slick studio floor for a talking-to from

the company’s administration, in which we’d be compared to a baseball team, to one big happy family, and told to behave, or else (or else, what?).

No more breathing in the sharp and acrid smoke from the fog machine in the middle of a show, even after the dancers’ union said it wasn’t allowed. No more choking on mucus running down my throat as I flit across the dry expanse of the stage.

No more hours spent rolling out my calves and hips with a lacrosse ball so I can move my body in the morning, no more lying down with legs above my heart to elevate my feet on every five-minute break. No more needles stuck hard into the undersides of my feet, piercing the leathery muscles. No more purpled toenails or ragged blisters.

No more asphyxiating anxiety in the wings. No more crashing down after a leap.

No more comedown after each performance.

Life is steadier now, more predictable. Life is a space of comfort. The studio, that aquarium that kept me paddling, is no longer habitable to me since I turned in my fins.

And, oh, all the things that are possible outside of the tank: the trips to the farmers’ market on Saturday mornings, the physical energy to go on a long walk at the end of the day, the ability to take time off to travel for weddings or family Thanksgivings, the interactions with people who live on solid ground. Seems to me that being fully human is worth the price. *****

In May, a week before my final performance as a professional ballet dancer, an elderly beneficiary of the company told me, as he gestured to the stage: “Nothing else you do in your life will be as important as this, remember that.” Already, I know he is wrong.

by Sara harley

I was sitting on the steps of Hope when a woman asked to pray for me. The late morning sun peeked through a web of elm and oak leaves, and the breeze carried the springtime revival in its wisps. Shades of pink, ivory, and violet magnolia blossoms had begun to flower, enticing the beetles and the bees with their sweet fragrance. Below the sunshade, little warblers with orange bellies hunted for seeds and sundots, while the squirrels prepared for the invasion of hammocks and frisbees. In a matter of moments, a barrage of protests, Egyptian battle reenactments, pilates classes, petting zoos, and campus tours seemed ready to sprout from the very grass. Swashbuckling pirates sang sea shanties while Wall Street wannabes, academics, and celebrity descendants lounged on picnic blankets. Even with all the action, time on the Green was still better described as languidly moseying. I was taking a brief intermission from tapping the delete key— drafting arguments and untangling evidence to convince my certainly socialist, possibly communist, literature professor that I had, in fact, done the reading.

The undisturbed morning reminded me of home: frosty windows, the old kettle, and curly steam that rose from the surface during early practice at the pool. When I moved east, buoyed by caffeine and a new beginning, I chased the early sun to outshine the things I couldn’t see. I thought it made me see clearer. I learned later that light and darkness can exist together.

This particular morning was not a joyous occasion. I had wasted hours contorted in a large armchair, hidden behind my computer, inventing new ways of writing the exact same sentence. Sitting between the tall stacks of books warped my perception of time. The hours ticked past as if they were bored too. The blueish hue of my screensaver reflected off the filters in my glasses, and sleep—or the lack of it—had collected between my eyes and left me slouched on the curb of inspiration. Deciding to cut my losses, I finally emerged from the dark caverns of the library seeking mercy. But, preoccupied with textual analysis, allegory, and metaphor, I forgot to watch the trees glimmer.

The concrete steps were still defrosting beneath me. I was wearing baggy shorts, and moved the fabric to avoid the chilly stone. Readjusting, I heard the door open behind me, and leaned to the side to let a trombone case pass. It looked inconvenient and heavy. The click of the automatic door refocused my attention to the parchment package before me: my double chocolate muffin. Ripping the

corner of the paper like a gift, I remembered why my flex points always seemed to fall from my fingertips.

I began to pull the still-warm dome from the base to reveal the chocolate chips in the center. The crusty bit is the best part; it crunches and crackles from the hot oven. But its decapitation proved messier than I anticipated. Before I could take a bite, crumbs exploded everywhere. Chocolate entrails lodged between my thighs and the creases in my clothes; I snatched the edge of my crumpled napkin before it escaped in the wind. Wiping away, I looked about to count witnesses. I had chosen these steps for their seclusion, more from my self-consciousness than from those around me. The early light seemed to help me exhale.

Satisfied with my clean-up, I noticed the cavernous pit in my stomach. I had waited too long to eat, and probably to drink water. Using the parchment to protect my fingers, I tore the muffin’s base in half. As I peeled a section from the wrapper, I paused for a moment, like how one honors a deer before its sacrifice. I listened to the birds, smelled the flowers, and finally locked eyes with an older woman across the way. She smiled and began to walk toward me.

I scrambled to hide the evidence, but it was no use. The lawn was empty except for the two of us and a few stragglers. This was not the time. With a longing glance, I set my disobedient breakfast aside. She was older, old enough to have grandchildren. Tight silver curls fell loose from a tousled bun held together with a barrette that resembled a pencil, or a decorative chopstick. The delicate lines around her smile lines gleamed with traces of happy memories. A delicate pair of metallic semi-circular glasses sat on the bridge of her nose, a sign of wisdom or necromancy. She wore dark wash skinny jeans that made her legs look like delphinium, and a long, pinkish button-down with a gold-printed “VS” on the right breast pocket. Her clothes reminded me of Haight & Ashbury, thrifty finds from San Francisco. She looked like she enjoyed eating her vegetables.

By far the most distinguishing feature of her outfit, though, was her shoes. Platform neon green slippers in sport mode—I had never seen anyone, let alone a woman of her age, wear them. Clutching a gallon-sized plastic water bottle against her hip, I determined I didn’t recognize her; she must’ve been a stranger. Finally, as she drew nearer, she whispered:

“Would pray…you?”

“What? I—uhm…sorry. I can’t,” I responded. I was too hungry to ask her to repeat herself.

Chocolate-covered, I felt like a child caught sneaking candy.

“Could I pray for you?”

“Oh! Of co—I mean…sure.” My Catholic school days sent a shiver down my spine. The lesbian in me smirked. What gave me away? I shrugged the thought away and decided: I had a few assignments looming, and a shout in God’s direction couldn’t hurt. My muffin could wait.

“You can eat, if you want,” she said. I liked her. She asked my name.

“I’m Sara.”

“Thank you, Terra.” I didn’t bother to correct her. It didn’t really matter, anyway. She closed her eyes and clasped her hands at her navel. Together, we bowed our heads. She proceeded to pray for almost 15 minutes. I was frozen by how her conviction strengthened her. The rhythm beneath her hushed tone emboldened her to speak louder. She spoke with a sense of an urgency about everlasting love. Intermittently, I raised my eyes to watch her speak. Her eyes were glued shut and her eyebrows pushed together like caterpillars trying to wriggle free.

She appeared to forget I was sitting there, except that she repeated my name, over and over, and soliloquized: “Please Lord, give Terra the courage to carry on. Let the singing birds be a sign of you.” I didn’t realize until later that she never told me her name. When I went to Mass as a teenager, prayer seemed like begging. For forgiveness or guidance, I thought it was simply better to be patient. But to her, it seemed to be an ode to her faith. It gave her purpose. Confession, sin, piety, and pain—I didn’t agree, but I understood.

Growing up without a mother or grandparents, I was always a bit afraid of the elderly, particularly of older women. Wisdom hidden behind a curtain of cognitive and physical decline, there seems to be a divide between an older person’s memory and their ability to communicate about the past. But, through prayer, I could see the decades behind her eyes. Someone who grew up under the pressure to find herself. As a witness to her faith, I wondered if my life lacked direction without it. With a last breath, she said she loved me, and left. As she walked away, I noticed the trees, smelled the flowers, and heard the breeze. Finally, I looked to the morning sky, and said I loved her too.

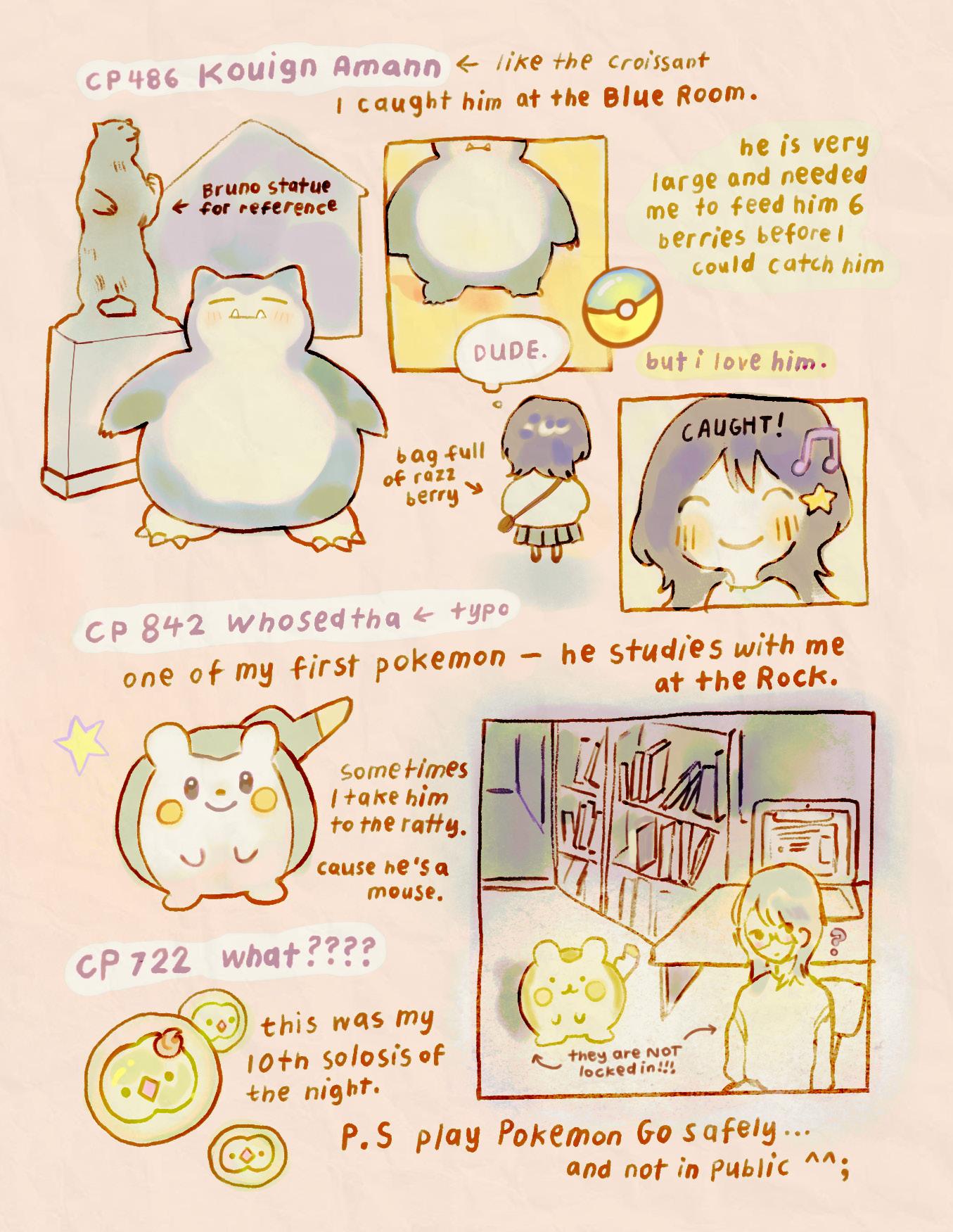

by Selena Zhu

post- mini crossword

2 3 8 7

Across Down 4

1. Original "Harvest Moon" platform, for short

5. Assists

7. Letters in a nursery rhyme

8. Urged someone on

9. Science dept.

1. "Baa" animal

2. Horse sound

3. Lamenting poem

4. James Bond and others

6. Grass seed alternative

Thank you for reading magazine. New issues every week.

“The fresh cold made us gasp until our blood and the steady air reminded us we were warm. Plumes of mud flowered from the river’s floor where the current tripped a rolling stone or the crawfish pranced or we shuffled and kicked. Our arms gestured high and droplets flew around us like crystal flies.”

— Nina Lidar, “about fire”

“We walk along the lake’s circumference and its green is something I want to inject into my hippocampus and remember, too. I reach for your hand hesitantly, as I am still afraid of being too forward, even after more than a year of knowing your calluses.”

— Ellyse Givens, “send my love” 11.2.23

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Emilie Guan

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Elaina Bayard

Section Editors

Anika Kotapally

Chloe Costa Baker

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

AJ Wu

Section Editors

Lizzy Bazldjoo

Sasha Gordon

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Gabi Yuan

Section Editors

Chelsea Long

Maxwell Zhang

LIFESTYLE

Managing Editor

Daniella Coyle

Section Editors

Hallel Abrams

Gerber

Nahye Lee

POST-POURRI

Managing Editor

Michelle Bi

Section Editor

Tarini Malhotra

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Junyue Ma

Lesa Jae

COPY CHIEF

Jessica Lee

Copy Editors

Indigo Mudbhary

Lindsey Nguyen

Rebecca Sanchez

Tatiana von Bothmer

LAYOUT CHIEF

Amber Zhao

Layout Designers

Emma Scneider

Emma Vachal

James Farrington

Tiffany Tsan

SOCIAL MEDIA

Rebecca Sanchez

Yana Giannoutsos

Yeonjai Song