Dear Readers,

Settling into this fall semester— which just so happens to be my last at Brown—has me feeling both eager to barrel forward, and longing to stop and look back. It’s among the busiest times I’ve experienced here, not only in sheer schoolwork, but in my ongoing and all-consuming attempts to prepare for what happens after I go into the dreaded Real World. But between my grinding sessions at the Rock, and my panic sessions about how I’m not grinding enough, I sometimes feel a different kind of pressure. It feels more important now than ever to commit to memory where I am and who I’ve been here. Call me overly sentimental, but taking a break to just walk around campus, look at the vast collection of pictures I’ve taken with friends here, or visit my favorite Providence haunts is as big a part of my life this fall as completing my readings and researching graduate schools. This also means giving myself time to just be in this place where I’ve spent the past few years. I’m trying to appreciate the things I love doing here, down to the trivial hobbies and predilections, so I can be the fullest version of myself wherever I go next.

In this issue of post-, many of our writers also ponder ways to remember and remain themselves even while

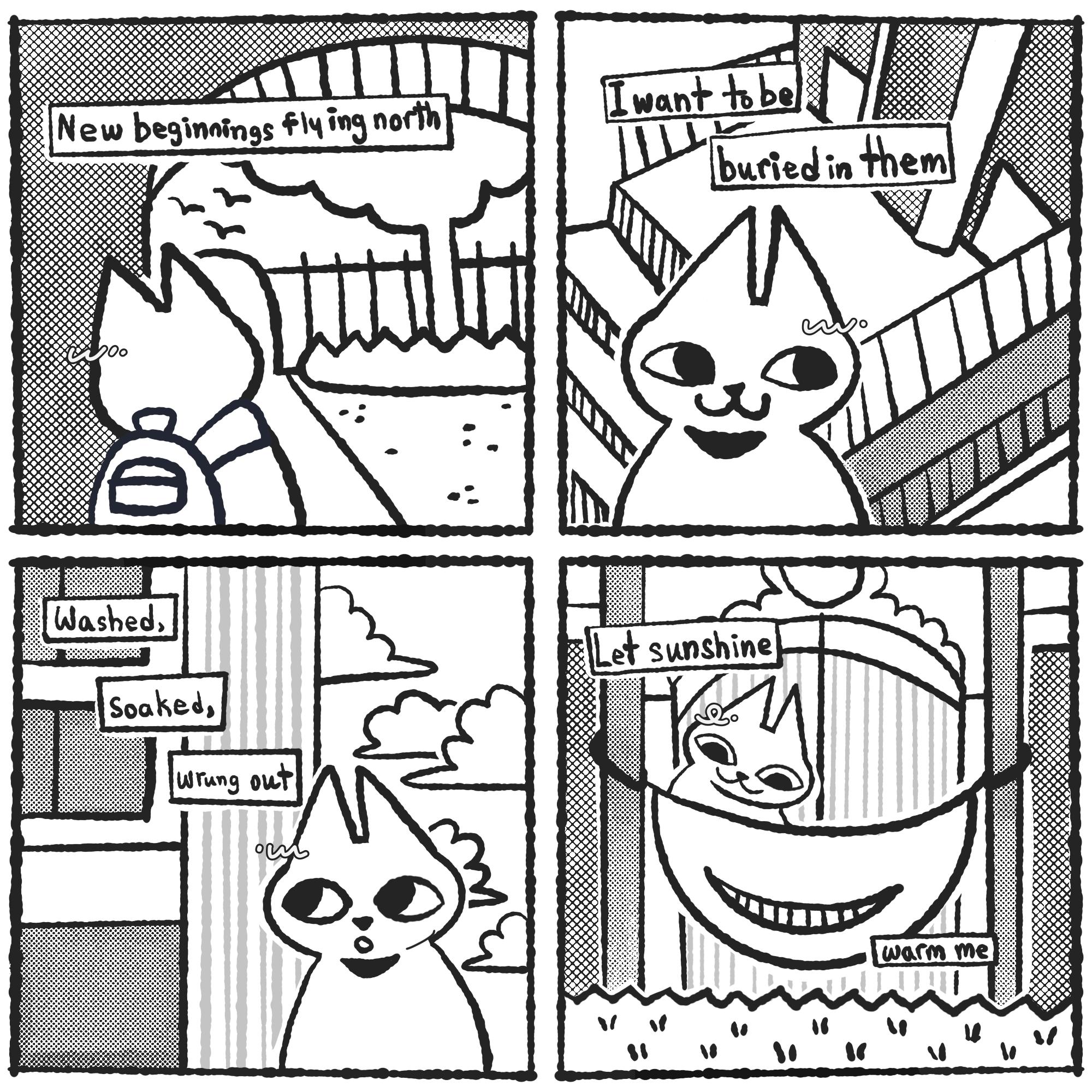

contending with external pressures. In this week’s Feature piece, Michelle grapples with the limited time we have, and how vital it is to be present with the people and things we love amidst a culture of bustling workaholism. In Narrative, Ana reflects on “filling your cup” in the face of productivity pressure, and Coco stops to look back (through her father’s eyes) on an unforgettable night in New York City. In Arts and Culture, Alyssa also remembers—in this case, growing up listening to Lorde’s coming-of-age album Pure Heroine—and Eleanor engages in careful self-reflection, inspired by Robert Lester Folsom’s “Situations.” Indigo urges research and respect for your study abroad country of choice in this week’s Lifestyle section, while Maria tells us how daily planner methods should organize and give, instead of drain, the time you spend in the present. Ina gives us both a comic that appreciates the sunlight in post-pourri, and a crossword that honors our furry/furries friends.

I’m struck by the mindfulness that the pieces in this week’s issue illustrate, whether it’s finding time to check in with yourself, or your surroundings, or your memories, or all of the above. As this semester continues to ramp up, I’m going to keep looking for moments to take my foot off the gas and look around. I hope this week’s issue of post- inspires you, dear reader, to do the same!

Stopping and Smelling the Roses (or whatever grows during fall),

Daniella Coyle

Lifestyle Managing Editor

do it on your own time

by Michelle Bi

Evening breeze winding through my small, soft hands. Tall grass tickling my ankles as I passed. It was just after sundown in the summer, and I was sprinting through a field, and I was still young enough to be unafraid of stumbling.

During childhood, my mom would regularly take me to the playground. Even today, I remember the sound of the kite flapping in the wind, the spool trembling in my hands. To my seven-year-old eyes, it seemed that the nylon had come to life, as if Southern California’s very first native scarlet macaw had decided to take up residence in the chaparral behind my elementary school.

It became a dance, me and the breeze. I chased the kite around and away and over the hill. As the air and I tangoed, I followed its every move, dipping and turning until I grew tired and flopped on my back into the grass. Still, the wind played with me, chasing itself through my hair, its rustle against the earth like laughter, and there in the field I was content.

In 2022, the Cleveland Clinic found that the global average life expectancy is 72 years. In the United States, it’s 77.

Right now, I’m barely 19. So, to me, those numbers are too large to comprehend. What does it feel like to genuinely grow old? For my entire lifespan to repeat again, again, again, and even again if I’m lucky?

The average American spends 5 hours and 16 minutes on their phone every day, according

to a 2025 survey. That amounts to—and please bear with my math here—about 80 days in a year, or almost 17 years in a lifetime.

Meanwhile, the average person spends about 26 years of their life sleeping, with an added 7 years of simply trying to fall asleep. 10 years spent working. 4.5 years spent eating. 6.7 years spent simply waiting around.

And here’s where I’ll stop doing math, because adding up all of those numbers scares me. None of us know how many years we’ll get— and how many of those are whittled away by things as banal as sleeping and doomscrolling. How long do we have left, after that, to holiday with family and pursue our hobbies and hang out with friends? How much of our lives is wasted on doing everything but living?

How much time do we have?

I moved back to college for my sophomore year a month ago, and instantly, my Google Calendar kaleidoscoped. Rainbow blocks of commitments stack on top of each other, week after week, like a child’s LEGO city.

And I don’t say this to brag, in some twisted sense, about how busy I am. I am trying to express that the past few weeks have felt more like decades. That at night, I can barely remember the morning.

I like this life, truly. Each time I found myself bored and aimless over the summer, I’d yearn for days with ever-changing schedules, responsibilities to fill my time with, the sensation of being stopped by four different

friends and exclaiming “we need to get dinner!” to each of them on the way to Andrews. My classes and reporting assignments fulfill me; my friends make me feel loved.

But there’s something curious about being busy so much of the time: You start to feel worse when you’re not.

Much has been written already about the pre-professional, perfection-focused rat race that is higher education. Multiple Brown faculty expressed concern to the Brown Alumni Magazine about the fact that firstyears walk through the Van Wickle Gates already considering internships. We apply for organization after organization, cram five classes into our schedule, complete mounds of p-sets and readings, all in pursuit of some nebulous, lucrative future.

Workaholism is a vital part of the conversation about collegiate mental health. But in my opinion, we are overlooking another factor: FOMO. There’s always something happening on campus—club socials, weekend functions, birthday parties, meals with friends. A 2023 study of 323 university students found that 15 percent reported feeling FOMO at least once a week, while another 35 percent felt it about one to three times every month.

At Brown, workaholism and FOMO have this curious way of morphing into one. Everyone somehow always turns their assignments in on time, and no one ever seems to be not working. Career opportunities are social events. Being

social advances your career.

And so often it seems like we are being swept forward by a pressure to be in constant motion. Neither our time at Brown nor our precious lifespans are infinite. In that sense, slowing down—even for a moment—feels a little like wasting the limited resources you’ve been given.

Allow me to set the scene: Jo’s at 1:50 a.m., for the third time this weekend. You’re swaying on your feet, and the tiles feel sticky. You’re a little tired of trying to crack jokes and engage in conversation, but you’re glad you went to that party—it was okay, you suppose, and what if you’d missed something life-changing beneath those strobing lights?

Or the EmWool hallways, a very long time after midnight and just a little longer till sunrise. The silence of the building seems to rise. There’s more orgo to study. There’s an exam to pass, and packets to finish, and an entire biology concentration that will be money-making in the end, you tell yourself. You just have to make it through one more hour of studying, one more hour.

Or your eighth club social of the semester. Or yet another night out, or another tutoring session, or just one more club, class, extracurricular, p-set—just one more. But you never have enough time for it all.

You never have enough time.

This past summer, I found myself aching to return to campus. My days consisted of going to work, going to the gym, and sleeping. Many of my best friends were spending their vacations at their respective college campuses doing

research, which meant that I had heaps of alone time and jealousy that hissed in the back of my skull. In the hot California haze, my life felt aimless; I drifted without direction.

The clock dragged through a month, then two. My calendar faded to empty. Even as I grew closer and closer to returning to Providence, my excitement was tempered by bitterness— while my peers had been researching and interning, I’d done almost nothing worthwhile with my summer. Who was I to walk back onto my Ivy League campus and mentor first-years, pretending I was capable when I felt anything but?

A week before my return flight to Rhode Island, my friends finally came home and demanded a beach trip. We spent the day hunting for the city’s best lobster rolls, jumping waves, basking in saltwater air.

Even stretched out on the sand, I found it hard to shake the intrusive thoughts that chased themselves around my mind. I didn’t truly deserve this break because I hadn’t done anything productive to warrant it.

At the end of the day, after we’d all loaded ourselves back into my car, I drove us along the edge of the beach. My friends insisted on rolling down the backseat windows, and we put Katy Perry on aux.

And as cliché as it was, I raised my voice to sing with them. We belted off-key down the Pacific Coast Highway; I eased my foot onto the accelerator. My world narrowed to the four of us, the thump of the bass, and the unrolling road. Me and my friends, shouting about California girls and golden coasts. I wondered if I could fold open this moment, climb inside, and live in it forever.

Then, the music seized me. So I cleared my mind and stopped wondering. I opened my window and let the wind come in.

I get it. I do. It’s cool to be busy because it means you’re in demand—countless friends and events jockeying for the privilege of having you in attendance. And it’s fulfilling to be busy, because it provides a sort of perpetual motion: Nothing can slow you down from your goals or ambitions.

But all of this fails in the face of the real-world effects of being overbooked. Yale psychologist Dr. Laurie Santos refers to this phenomenon as “time famine”: the inevitable feeling of being overwhelmed by responsibilities. In a 2018 study, four out of five employed U.S. residents reported that they felt “time poor.” Being overly busy has been associated with a slew of negative health effects, ranging from anxiety disorders to reduced medication adherence to compromised immune function.

At the heart of chronic busyness is denial, according to Dr. Kristen Beesley. When we push ourselves to be constantly productive, we deny our own limitations to others. And we deny to ourselves that we have emotions and needs beneath the surface. Our obsession with filling time bars us from truly living it.

So how do we reclaim it all? Our time, our mental energy,

our ability to understand and stand by our own boundaries? I would be lying if I told you I knew exactly how. The hardest part of being at Brown for me hasn’t been academics or social life. It’s been accepting the fact that I am not invincible and that I have limits; we all do.

We were sitting under a tree on Prospect Terrace, me and my orientation group, and the day was cooling into a breezy dusk. Despite feeling exhausted from a week of training and sidequests, I sailed through most of the questions they’d written down. The best study spot on campus is Rhode Island Hall, specifically the second floor. First-year friend groups fall apart sometimes, and that’s okay. Always run to Andrews for the dry noodle bowl, but never get the vermicelli.

It wasn’t until near the end that I stalled. Oddly enough, I remember becoming keenly aware of the sounds of the birds in the trees, the grass tickling my calves, as I looked down at the question scrawled on the sticky note. What’s

something you wish you’d done earlier at Brown?

The first thing I said was something along the lines of “used S/NC,” and that garnered approving looks, so I kept talking.

But it didn’t feel completely honest. “One more thing,” I said, even though I really didn’t know what I was about to say. “I wish I hadn’t made myself feel guilty about missing out on things.”

We were nearing the end of Orientation at this point. Looking around the circle of bright eyes trained on me, I was reminded of what it’d felt like to step onto campus for the first time, and the second, and the third. That unbounded, ceaseless energy, that desire to be part of everything. Then I thought of four lowered car windows and storming bass, a few minutes of bliss, of letting yourself feel it.

So I told them to make sure to reserve time for themselves. That it’s okay to take breaks and prioritize your well-being, that the world will still keep turning and that’s alright. The sun will rise again tomorrow, and you’ll be alright too. There are a lot of tomorrows.

As I often do when I write for post-, I have already pushed the word count far beyond its limit. Here is where I start trying to narrow it all down to a punchy conclusion, to convince you that I have it all together. Our time is coming to an end.

I could throw statistics at you about how leisure time, far from being a waste of resources, actually improves quality of life. I could extol the virtues of intentionally scheduling time for your hobbies and self-care rituals, committing just a little bit of energy a day to recharge

without stressing about the outside world. I could tell you to outline what’s essential in your life, and focus on the quality of your engagements instead of the quantity.

But I won’t (I packed it all into that paragraph instead). And now I’ll set the scene just once more.

I came back to my dorm from Prospect Terrace feeling drained, but happy. It’d been a long week, with my calendar blocked yellow and blue every day. I had a few minutes before dinner with my friends—some old, some new.

So for once, I decided to take my own advice. I rolled up my curtain to watch the sun slipping beneath Sayles, and I sprawled out on my bed with a notebook and pencil. I put on some music. I let my thoughts ramble out of my mind and onto the paper, and I didn’t bother organizing them.

I think we all yearn for moments in which we are fully and completely present; we had a lot of them back when life was simple, and then we got busy. But all that means is that sometimes you have to intentionally partition them out instead, to step back from the rat race and carve yourself an hour or two of joy.

And other times, beautiful moments can flutter into your lap when you aren’t paying attention. The best you can do then is cradle them, love them while they exist, remember them after they’ve faded, as everything does. Even now, all grown up, or at least partway there. The scratch of my pencil against paper. The crickets sounding the first beats of their nocturne outside. The evening breeze, gamboling through the open window to caress my sunworn hands.

by Ana Vissicchio

Illustrated by Selena Zhu

As my feet, clad in an obnoxious blue and orange sneaker combo, hit the pavement again and again and again, I can’t help but feel guilty. These days, that’s how a run—or a walk, or a break, or a pause to sit and chat with my roommate—feels. I start off with a mindbending, totally unnecessary weighing of ways to pass the time—do I run, or do I finish my book for class early? Do I start my discussion post? Do I put some dents in my thesis? A run will take just under forty-five minutes, plus getting changed and then un-changed, showering, and stretching, thinking about and adding up how long everything will take.

And after all that, I hurtle down the stairs, slam the door, and start to run. The guilt that follows my first few leaps trails in my wake on the uneven pavement I leave behind for the East Bay Bike Path, making way for an endorphininduced blank mind.

Lately, it feels like everything takes longer

than usual. I wake up with a start, overwhelmed by the sheer number of tasks I have to complete, and then, if I don’t check everything off, the feeling gets compounded the next morning, the heavy load of catch-up weighing me down. Just the other day, I got frustrated that making lunch took me an hour. Maybe it’s living off-campus that’s fueling these thoughts—now on top of school, clubs, and social activities piling up, so do the dishes, little piles of dust, and clumps of hair in the shower drain.

Yesterday, my roommate told me that she’s trying to listen to less music. “Imagine if we had shower thoughts way more often,” she had said.

With my everyday rush before class or work, I don’t remember the last time I had a good shower thought.

I’m trying to information-max, savemoney-max, sleep-max. Time-max. I’m just trying to shove more hours into the day, I’ve realized. When I’m not reading for English class,

conquering them. It’s about thinking about what to say in class, not losing sleep over it. It’s about overcoming crippling perfectionism by letting yourself relax into it a little, accepting it, absorbing it. It’s okay to strive for perfection, I think, but it’s not okay to beat yourself up when it’s inevitably unachievable.

I watch my roommate go on her daily runs, sometimes sans music, and relish in her bubbly energy as she chats and stretches in the kitchen. I hear how happy it makes my grandma when I take just fifteen minutes out of my day to call her. I look forward to the simple joy of

whisking matcha in my little ceramic bowl for an afternoon treat. I take the time to write a thought-out letter to send to loved ones at home.

Making time for running, writing, walking, sewing, talking, sitting, whisking, mailing, and doing absolutely nothing—it’s just as important as the work I feel guilty for not focusing all of my attention on.

I’ll stop filling my schedule and emptying my cup. And I’ll start drop by drop, a call to my brother, a walk for myself, a movie just for joy.

Every day, I’ll try to fill my cup.

How will you fill yours?

a (mostly true) account of my dad’s night in ’77

by Coco Kanders

Illustrated by Lesa Jae

You came to outrun last semester. The slacking, the smoke, the classes you let tip into a soft, resinous fog. You blamed Donnie Hazel. Hazel of midnight joints, floor-creak monologues, and the art of drifting out of the abstract world of collegiate commitment. So you hit I-95 and called it reform. New York would be your detox, you decided, the kind you walk block by block until it agrees you belong.

mousy brown hair to the shoulders in a notquite-curl, or maybe just uncombed; a dress that hangs on her like a small tapestry; thin gold medallions knocking softly at her wrist and throat. A cigarette rests in her left hand; her right cups her rib cage, holding on as if the city might jostle something loose. She looks at you, really at you, and you sense she’s decided.

“Would you like to go to Woody Allen tonight at Michael’s Pub with me? I’m getting tickets,” she says, and takes a drag, the smoke punctuating her invitation.

You and Shorb chorus a “Sure,” because of course Shorb loops himself in; that’s his sport. Still, the moment cleaves toward you, and you know with him it's got to be tit for tat. She picked you, and she goes to Harvard. And she picked you.

You and Shorb meet Tapestry at 8:30 sharp. She’s brought a friend for him—tall, long bones, hair like sun-faded rope. Both of them

It’s 1977, and you live in a studio on 57th and First, a shoebox with a brick wall for a view and FDR Bridge’s hum like distant surf. This is Sutton Place, the crème de la crème of New York in ’77, and you pay two hundred smackeroonies a month because you split it with Robert Shorb. S-H-O-R-B. Not “shore,” which is what people hear when you say it too fast, like he’s a beach and you’re washing up on him.

Shorb knows people—better, he knows the people who know the people who matter, which in this city is the same thing as mattering. You’re both Class of ’79, junior fall, freshly escaped from your bridge-and-tunnel origins to live not just somewhere, but in New York, which, at twenty-one, passes for a plan. You keep telling yourself you’ll become the kind of person Shorb already knows; in the meantime, you practice.

Most mornings, you and Shorb hoof it from 57th and First down to 40th; school’s right off Fifth, across from the public library. Your school is a penthouse situation: the top two floors of a mid-block building with a perpetually busted elevator and a lobby that smells faintly of turpentine and ambition. Everything is dirty and bohemian, and you, having traded slacks for high-waisted orange-tag Levi’s bell-bottoms, are likewise bohemian and dirty.

Today, though, Shorb is bored with the usual route—Shorb is chronically uninspired unless the night promises a club, a line, and a woman, and even then he tires. You angle west on 55th and end up outside Michael’s Pub. You’re not a regular, yet not a stranger. Monday nights, Woody Allen and his New Orleans jazz band play. Woody on clarinet. It’s not exactly your thing, but Shorb swears this is culture, and anyway, why did you come here if not to collect reasons to say you did?

That’s when she finds you. She isn’t beautiful so much as arresting:

look freshly rolled out from a Volkswagen and dusted with patchouli.

Inside, it’s a sauna of cigarette smoke and body heat. You catch yourself trying to breathe correctly, too self-aware, so you stop and let the room do the work. The light, the pub, the smoke, and Tapestry take your hand and walk you into the red-hot ether. Shorb leads, of course, holding Blondie and manning the room like he owns a controlling interest. Blondie links arms with Tapestry; you take Tapestry’s trailing palm and white-knuckle your way through the crush, shimmy and shove, and surrender your body to the small, exhilarating debauch of a Monday night that thinks it’s a Friday.

Four front-row seats open like they were saved with your names, a miracle you all pretend to deserve. You and Shorb bookend the women. He pops up on cue— “What’ll you ladies like to drink?”—already halfway to the bar. You go with him, because that’s the choreography: Shorb leads, you flank. The night complies.

At the far end: Him. Woody Allen, alone at the bar, hunched, tapping his foot, sipping something clear. The lenses of his glasses make his eyes look like they’re looking at everything all at once—including you. Your turn to order. You point at his glass, arrested.

“That.”

Then Louder, as if you’re placing an order with your future self:

“I’ll have that.” The bartender nods, professional, unfazed. “Gibson. Straight up. Onions.”

forward.

They start New Orleans slow, a sleepy river number, clarinet shouldering the melody like a man carrying a lamp through fog. The trumpet answers with something sour-sweet, bent notes that wobble and then stand up straight. The trombone laughs in brass; the bass walks a long hallway, never turning back. Behind it all, the piano keeps time the way a good friend keeps a secret, steady and unshowy.

Your sense of self loosens. The smoke becomes visible music. Gray ribbons thickening, thinning, a staff in the air. Heat slips under your collar. Your foot finds the floorboards’ hidden drum; your fingers conduct something only you can hear. The clarinet climbs. Not flashy, never flashy, but insistent, patient, like a man making his case to the night. A smear of blue becomes a line of red becomes a violet halo around the bell of the horn. You are in the color now; the color is in you. The Gibson acquires a second life as

the stage like it’s telling her a secret you’re barely qualified to overhear. She smiles without moving her mouth. The smoke makes a chapel out of the light. The bracelets at her wrist become a metronome; glass wind chimes in a minor key. They peel back for a chorus, clarinet alone, then piano braiding in, bass placing each step like a careful host. The melody comes home without saying goodbye to anyone. Applause detonates. Stomps, hoots, stinging palms. Shorb is first to his feet, of course, clapping high, auctioning for an encore. Blondie whistles through two fingers; Tapestry smiles with her eyes and claps her hands until they blush. You stay seated because standing would be imprecise. You have never liked imprecise.

When you find the courage to stand, the room tilts, one of those ocean-in-a-bottle moments. You realize you’ve drunk the Gibson down to its villainous little onions, which have sunk to the bottom like two corpses. You navigate the aisle, shouldering past a polite wall of bodies, and find the door by instinct, the way animals find water.

When you stumble outside, New York hisses. A bus coughs itself empty at the corner. The air feels refrigerated. Across the way a couple argues like dancers—turn, step, turn. You inhale the unflavored oxygen, and it tastes like being twenty and lying competently.

This, you think, is why you came “abroad” to New York. To sit in a red room and let a clarinet reassemble you. To point at Woody Allen’s drink and meet your future at the bottom of the glass. To be chosen by a woman in a tapestry dress and feel, briefly, like the kind of person who gets chosen. And yet, you can't help but think about your small campus with its varnished hush and its library lamps like moons at elbow height. The domestic tragedy of Donnie Hazel’s midnight joints. Of the soft discipline of small lives wellattempted. There’s a charm in knowing the snack bar closes at one and your friends at two. The city will always have another Monday, another room to be remade inside. But the other place—the one with the creaking floors and the undeserved grace of second chances—will be there too, uncomplicated in its very complications. You decide you can have both: this city that takes your pulse and returns it quicker, and that town that slows it down until you remember your name.

Shorb eagerly breaks your trance to guide you back to the table. The drinks land sweating. You sip and get the clean punch of chilled vodka and onion brine, whispering from the bottom. It opens a small door behind your breastbone and lets the night walk in. You take another swig just to prove consistency.

House lights cinch tighter. A spotlight finds the microphone like it’s been hunting all night. Tapestry is on her fourth cigarette and you don’t mind the smoke—it suddenly feels like the only sense of structure. The band strolls on, trumpet, trombone, piano, bass, and then the clarinet, that reed-thin question mark. No preamble. A count you feel more than hear, and the room tips

it circulates: It’s a solvent, a permission slip, a grammar for wanting.

Somewhere mid-set they swing harder. The room jolts awake. The waitress slaloms, ice cracks in a shaker like winter breaking, the trumpet drops a high note that sets the wall mirror trembling. A man two tables back keeps time with a matchbook; the bouncer nods on the off-beat, tender as a lullaby. You feel newly absurdly fluent in a language you didn’t know you were studying. The melody says: Here you are. The rhythm says: Stay as long as you need. Tapestry leans into your shoulder for one bar, maybe two. Everything after that is a fact of borrowed land. You watch her. She watches

The door burps heat and brass behind you. Tapestry steps out and threads her arm through yours as if ending a sentence you didn’t know you were writing. “Come on,” she says, and it’s not an order; it’s a route. You don’t negotiate. You let her steer you back toward the noise, where the band is already counting off a new way to be alive, and you, quick study, reforming slacker, future adult with onions in his glass, are finally ready to keep time.

on pure heroine & growing up in + growing out of the suburbs

by Alyssa Sherry

by kyra chen

I’ll be twenty-two before you know it, and my final year of college starts in three days. I am watching the sun slip through the openings in the fence and gilding the honeysuckle. I am pressing my palms against the pavement, still

warmed by the final day of August. I am listening to the cicadas. They will die soon, but they don’t know it yet.

A few minutes after the sheen has slipped from the flowers and trees, my mom comes into the backyard, and we walk a loop around the neighborhood. It’s too dark to see anything, but we know all of our favorite spots implicitly, trusting that they are always the same, whether or not they are visible. There is the quiet rumble of traffic in the distance, the crunch of leaves under our sneakers.

As we walk, I think about how my life will never be quite like this ever again. Maybe that’s dramatic, but it doesn’t make it any less true.

*

“All my life I’ve been obsessed with adolescence, drunk on it,” Ella Yelich-O’Connor, best known to us as Lorde, wrote on Facebook to commemorate her twentieth birthday in 2016. “Even when I was little, I knew that teenagers sparkled. I knew they knew something children didn’t know, and adults ended up forgetting.”

I’ve loved Lorde for practically all of my life, but I always find myself relating to each record on a few years’ delay, finally growing up enough to understand it just as she’s moved on. When she released her debut album, Pure Heroine, in September 2013, I was nine and she was sixteen, and I still had a long time to go.

Pure Heroine is a love letter to being young in the suburbs—a love letter to that feeling of invincibility that comes with growing up somewhere ordinary, the precocious pretense of maturity. Above all, it is a love letter to putting down roots, to growing up, growing alongside, and growing out of the streets more unchanging and better known to you than your own face.

My favorite piece of the album, and potentially of Lorde’s entire discography, is the second track, “400 Lux.” I fell for this song much later than I was meant to. I was nineteen, and I had only started to realize how much I loved my hometown now that I’d left it. The song is a celebration of, for lack of better words, how dumb shit never feels dumb when you are

stupidly in love. The first lines of the song ask, “We’re never done with killing time / Can I kill it with you?”

The chorus, too, has stuck with me: “(And I like you) / I love these roads where the houses don’t change / (And I like you) / Where we can talk like there’s something to say / (And I like you) / I’m glad that we stopped kissing the tar on the highway / (And I like you) / We move in the tree streets / I’d like it if you stayed.” Through these lyrics, Lorde captures the frivolous gravity of adolescence and how love between people becomes irrevocably intertwined with a place.

My favorite part of the song kicks in before the lyrics even begin: the sound of a car blinker ticking against the beat. I like to imagine Lorde singing “400 Lux” to herself as she drives around her neighborhood, blinker clicking, windows rolled down, pavement reflecting hot summer air in the twilight, dreaming of staying.

* Tomorrow, I am graduating high school.

It’s the end of June and the sun sets late and lightning bugs glitter like a memory. I am sitting on the curb a few streets away from my house, still sun-baked and warm at dusk, running my hands through the grass and pushing dirt under my nails as if my fingers might suddenly become roots. Spindly and winding and permanent. Last winter, it snowed over two feet for the first time in years. When I climbed the snowbank leading to the creek down the road, I sank all the way down to my waist, ice packed in the crevices of my sneakers. My neighborhood is right off Route 23, but back by the creek you’d have no idea; the snow fell so thick and clumpy and muting. The trees were wires. The sky was empty. My feet were cold.

I have a nosy neighbor across the street, like we all do. There’s a light above her garage door that flicks on when there’s motion in our driveway, and I’m sure she’s got all our comings and goings on videotape. I’m sure she’s caught me coming home past curfew from Daniella’s on countless nights. Daniella and I started dating back in October, and she’s going to college down the road. I’m the one who’s leaving after high school graduation, and in a few months, we’ll break up because I didn’t want to stay. But we don’t need to know that yet.

*

“That slow burn wait while it gets dark / Bruising the sun / I feel grown up with you in your car / I know it’s dumb” begins “A World Alone,” the closing track of Pure Heroine. It’s self-assured and self-conscious all at once. To me, this track celebrates a quintessential adolescent feeling: that no one in the entire world could possibly understand you, that you are fundamentally unknowable, that you are unique in a way that no one else has been. When I first heard Lorde declare, “Let ’em talk, ’cause we’re dancing in this world alone!” I felt known in this naive unknowability.

Once I grew up a little more, I’d realize what a beautiful delusion this had been—I was never tragically misunderstood, nor was I living a life so fantastically different from anyone else. But “A World Alone” was a companion to me in my adolescence, as I stood by the creek behind my neighborhood in the snow, as I popped the screen off my bedroom window and watched the stars from my roof, as I snuck onto the lake beach, as I tried desperately to exist within my town as deeply as it exists within me.

* There’s not much to do in my hometown except drive circles around Packanack Lake. This activity, famous to every high schooler with access to a car, is known as “doing lake laps,” and each rotation takes seven minutes. We spent hours every Friday night doing lake laps, which meant that most of our Friday nights were spent spinning around and around in a tight loop past the same landmarks—each of which holds a memory forever enshrined in our collective history. Like the East Beach Parking Lot, where Delaney broke up with her high school boyfriend, and the spot right next to it with the kayaks, where we all went swimming in the middle of November to win a scavenger hunt. There’s the peninsula, where we spent all our time in middle school, and the dam, where we spent all our time in high school, talking at the dark and the water. There’s Delaney’s house, where we made Musical.lys as twelve-year-olds, and Mady’s old house, where we threw a massive

party for our senior year Halloween. There’s the pizza place that closed, the hair salon I used to love, the church I grew up in.

A whole universe contained in a sevenminute loop; a history of my friends and me. All the silly, small moments of our adolescence that felt like everything at the time. Driving around and around and around.

We’re barely all home at the same time anymore, maybe only once a year. But whenever at least a few of us are back, we do lake laps. The lake smells strongest on humid summer nights. We drive by the houses of people we used to know. We play the same music we liked when we were seventeen. We tell stories about our new lives and we reminisce about our old one.

“In the underpass where we all sit / And do nothing, and love it,” Lorde sings to close out “White Teeth Teens,” another track off Pure Heroine. This lyric feels spiritual, evoking all those nights that my friends and I spent around the lake as teenagers: We did nothing. We loved it.

* Out of all of Pure Heroine’s magic, “Ribs” in particular has emerged as a cult classic and a coming-of-age anthem. In “Ribs,” Lorde reflects on growing up, telling us, “My mom and dad let me stay home / It drives you crazy, getting old,” and “I’ve never felt more alone / It feels so scary, getting old.” To me, the most resonant part of the song is when Lorde sings, “I want ’em back, I want ’em back / The minds we had, the minds we had / … / It’s not enough to feel the lack / I want ’em back, I want ’em back, I want ’em!”

To me, the scariest thing about “getting old” is not about facing what lies ahead—it’s about letting go of what lies behind. It’s the aching fear that I might lose touch with the girl I was, the girl who felt everything massively and loved recklessly and made all the small things big.

I think about her, often, that version of me, who was seven and ten and fourteen and seventeen in the same house on the same street in the same town. Really, to say I think of her sometimes is an understatement; I keep my grasp on her tight. And I grieve her, although I know she would be proud of me for moving on.

I think of her when I hear the crickets outside my bedroom window. I think of her when I braid my hair. I think of her when the sky turns deep blue and the streetlights flicker on. I think of her as my blinker clicks on the long drive home.

*

I am five years old and I am catching lightning bugs in my front yard. My hair hasn’t gotten curly yet, but it will. The heat bugs haven’t come out yet, but they will. The air is sweet. The sky is melting into navy. The neighbors are setting off fireworks. My mom and I are laughing together. There is golden light glowing warm in the front window. I will never really leave.

by ELEANOR DUSHIN

Illustration by CORA ZENG

me astray, and in this instance, it brought me to “Situations” by Robert Lester Folsom. I was struck by the song because of its last verse, one that spoke to much of my experience in college: I’m at an old friend’s party

And I’m sitting all alone

But I wouldn’t be so lonely

If I’d only go get stoned…

It’s just a situation that I’m in

It’s all because my friends don’t understand

I don’t drink or smoke. Obviously, this has stunted my ability to connect with my peers. But it was comforting to see myself as a sort of damsel in distress—someone who was surrounded by those who didn’t know how I felt. If I were just a victim of circumstance, the onus wouldn’t be on me to change. But RLF keeps singing:

It’s a situation I’ve got to live with or change

The situation at large wouldn’t change. I

a solution to anything. I was letting myself feel trapped and alone, but being hurt doesn’t always mean that someone needs to apologize to you; we have agency over our feelings. The options were to live with it or change, and I had been doing neither. But the time came when I grew tired of shrugging my shoulders and going home. Controlling what I could, I pulled away from those I felt uncomfortable with while they were under the influence and spent time with people whose company felt safer.

When I was younger, I visualized the endings of relationships as a binary: There was a winner and a loser. The breaker-upper and the one who’d been dumped. The player and the one who’d been played (the playee, if you will). The one with dignity and the one without. Relationships seemed to me a kind of competition; I sat on the edge of my seat waiting

the one to say that I pulled away from them— not the other way around.

By the time I got to college, I’d outgrown the competition I felt in relationships, but I hadn’t abandoned the binary thinking—I’d simply replaced it. What was once winner and loser became victim and villain. I knew I couldn’t avoid being hurt. The boys I was interested in weren’t interested in me and I hadn’t found the perfect friendships I thought I deserved, so I turned to thinking of myself as the victim of serious transgressions. Why are they smoking tonight when I’m the one who asked if we could hang out? Why did he hold my hand if he wasn’t interested in dating me? You don’t kiss someone’s forehead for no reason. I read too far into meaningless exchanges under the impression that their missteps were taken out of malice at worst and disregard for my humanity at best.

A friend who’d rejected me romantically in the fall put his head on my shoulder and looked between my eyes and my lips in the spring. Although this came at an opportune time (I had a draft due for my writing class that Friday), it stole my focus for days. I stood in the kitchen at a party, my eyes fixed on the cabinets: bottle of soy sauce, balsamic vinegar, why did he choose the Jeff Buckley CD, fusilli, rotini, farfalle, why were we holding hands, garlic powder, onion powder, soy sauce, does he think scrolling through Wikipedia together is romantic too, soy sauce, soy sauce, soy sauce.

“Are you okay?” the hostess asked me.

“Yeah,” I replied. “Sorry, I just forgot about an assignment that’s due tonight.” I walked home and wrote and submitted the draft.

The next day, I sat crying on Liliana’s couch. “If he changed his mind, great,” she told me. “But if he’s doing this just to do it, then he’s a dick and you should never speak to him again.”

The warmth of his fingers in mine had relit the candle: I wanted him to like me. But more than wanting him to like me, I wanted to be important. In the case that he liked me, I could be special to him, and doesn’t being special to him just mean being special? In the case that he didn’t like me, it was more complicated. Whatever hurt he caused had to be focused and intentional. If he had put thought into hurting me, then I was still at the center of something. If he was going to hurt me, it would be because he meant to hurt me. It would be because I meant something.

It was easier to narrativize my experiences if I lied to myself. If I told myself that I was the victim, that I was simply caught in the crossfire of masculine arrogance/inconsideration/whathave-you, I could keep myself at the center of the experience. Nevermind my failure to tell him how I felt, nevermind the fact that I knew he simply wasn’t thinking that hard. My selfpity and disregard for the two-way-street-ness of it all had nothing to do with his actions and everything to do with my desire to feel special. I wanted to be distinct from other girls he had (or, more relevantly, had not) been with.

However you spin it, there’s no denying the truth: Ignorance is bliss. But in the crumpledup, overdriven mind of a 21-year-old college girl, there is no ignorance. In “Situations,” RLF sings:

Stuck inside the basement

And I’m freezing half to death

And this dirty air I’m breathing

Is depriving me my breath

My catastrophizing over one night’s unevents was suffocating me. It was stircrazy pain that did nothing but keep my mind occupied. It was dirty air that I kept breathing under the assumption that I was locked in the basement. But he continues:

It’s just a situation, wrong or right

But did I have to close the door so tight?

I was the one who confined myself to selfpity. I closed the door to the basement. I had placed blame on him, given myself the badge of victimhood to wear proudly as a justification for the way I felt, lied to myself about the nature of the situation. The time comes when you have to tell yourself the truth: “It’s a situation I’ve got to live with or change.” Changing the situation can be an internal reframing. There was a sweetness to the night when my friend-via-

friendzoning looked at my lips. I was choking on the dirty air I’d made for myself, but if I had only opened the door, I would be able to breathe in the freshness of the light between us, even if nothing happened.

Looking toward my friendships with the non-sober, truth bubbled to the surface. I was the one who decided to go to parties I knew I’d hate. I didn’t tell people how I was feeling, I just assumed that my crossed arms were perceptible to the drunken gaze of a 20-year-old. I didn’t want to be the loser, so I made myself out to be the victim, closing the door tightly enough to feel that I didn’t need to change. I liked the dirty air for the excuse it provided for me, but I hated it for the pain it had caused me. Ultimately, I was mad at myself for keeping myself locked in the basement.

These weren’t bad friends, much less bad people. They weren’t villains for embracing their idea of the college experience, and I wasn’t obligated to be around them. Sometimes things are simple: I don’t smoke, they do. I don’t drink, they do. I’m not happy, so I’ll leave and place my time elsewhere. Our misalignments weren’t moral failures. There doesn’t need to be a push and pull of friendship ethics and misplaced anger. By letting go of ascriptions of right and wrong, of win and loss, of victim and villain, we open ourselves to the joy of simplicity, the bliss of saying: “It just didn’t work out.”

Overcomplications are easy; what’s hard is seeing the truth, and what’s even harder is operating in accordance with it. I’m not immune to pain, but I’m rarely the sole victim of a situation. It’s done me no good to lie to myself. The truth’s on the tip of my tongue.

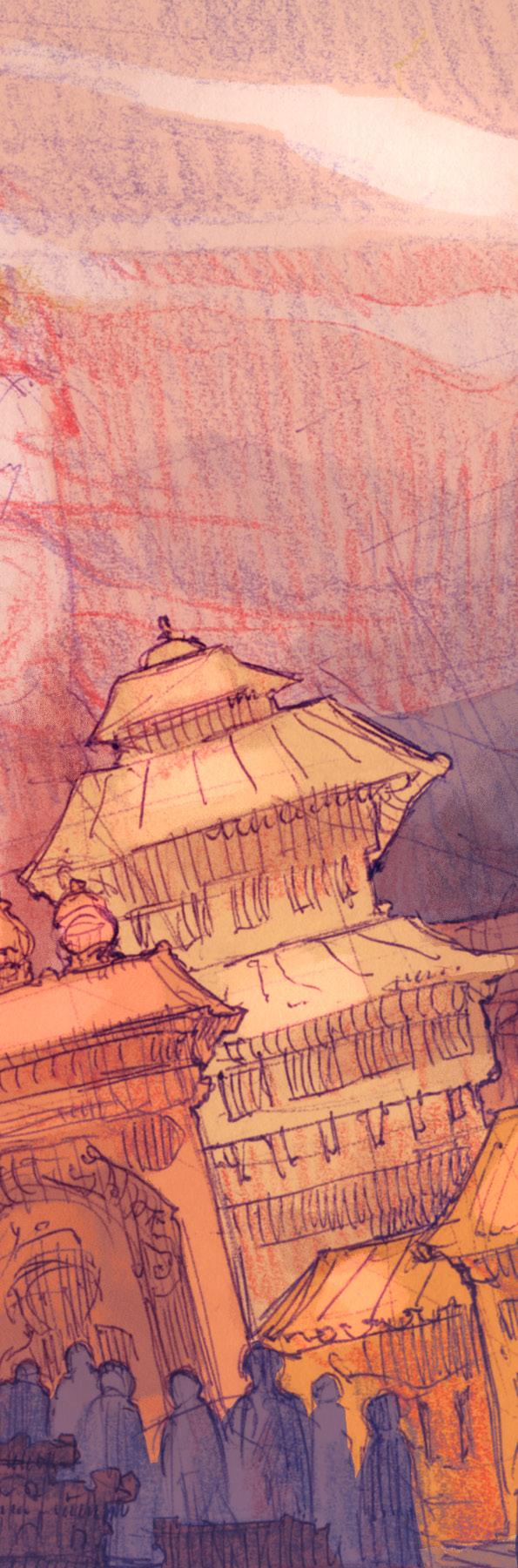

some advice for those who plan to go abroad

by Indigo Mudbhary

Illustrated by Ellie lin

If you’re in my life, you’ve likely heard about A. I hate A. Well, hate is a strong word. I deeply dislike A, to the extent that I’m still having imaginary arguments with her in my head despite the fact that it’s been two months since I last saw her.

While I am an easily frustrated person, it takes a lot for me to be totally unable to stand someone. When I first met A, I expected for us to be friends. We were both working at a rural development NGO in Nepal this summer, and we initially bonded over a shared love of hard classes and fuckass campus jobs.

However, it very quickly became clear to me that A had no knowledge of Nepal before deciding to live there for two months. She had no idea what the Nepalese Civil War (19962006) was, and asked me what the om symbol on the wall of my family’s house was. Normally, I would not fault a person for not knowing these things, but I found it genuinely bizarre that she had done no research about the history, politics, or religious life of Nepal before going there.

At first, I let it slide. I’m quite used to ignorance about the place where half of my family lives. A postdoc at Brown once questioned my desire to research anticolonialism in Nepal, saying, “I thought every Nepali loved the British.” If Dr. Redacted could be that ignorant about my home, I was willing to cut A some slack.

Regardless, A was working on a thesis about Indigenous languages, so she asked if she could tag along on one of my field visits for my thesis to interview people for her project. I gave her a hesitant yes, and off we went to a rural municipality in northern Nepal.

While there, A asked a question so illinformed and therefore offensive that it upset her interviewee, who bluntly said: “Why would you ask me that?” She repeatedly demonstrated complete ignorance of the very subject she claimed to be researching, which could have been remedied by skimming a Wikipedia article or a brief Google search. Despite the fact that I had sent her multiple readings on Indigeneity and language in Nepal, it was clear she didn’t think that she needed to learn anything before engaging with Nepali people.

The point of this piece is not to call attention

to how ignorant A was or how her poorly designed research questions ruined several Nepali people’s days. Nor do I seek to laugh at a particularly interculturally incompetent individual (though it was funny when she saw me receiving tikka and said, “I didn’t know people did that in real life”).

Rather, I think A is a good cautionary tale to all students who want to go abroad at some point for whatever purpose. After one of her shitty interviews, she turned to me and said, “Wow, it’s actually crazy that U.S. understandings of settler colonialism don’t work in Nepal.” No shit, A. I think that this points to a larger dynamic: ignorance is often framed as something to be celebrated. We say, “Wow, I never knew that before,” as if we’re announcing that we won an Olympic gold when maybe—just maybe—we probably should have known that before.

So, to any student going abroad for a semester or a summer: Your ignorance of that place is not an asset. Do some light research before you board the plane, try to learn the language at least a little bit, and be gracious as you navigate your inevitable blind spots. Doing so is an important way to demonstrate humility and respect for a people and a place.

So travel far, travel wide, but remember that the places that are new for you have histories and political contexts that you’d do well to know a little bit about. The world is your oyster, but it’s not a blank canvas.

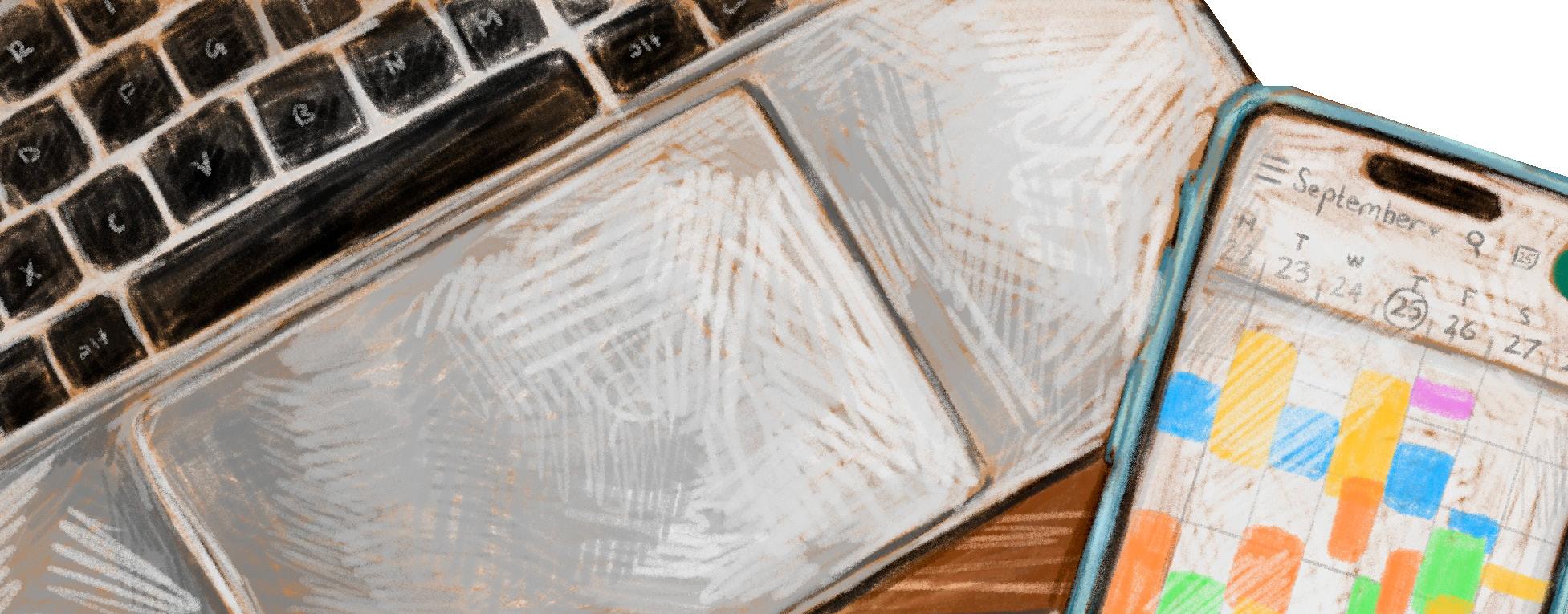

some solace for those struggling with GCals

by Maria kim

When I was in middle school, my friends and I loved to bullet journal. Each of us bought our own personal dotted notebooks that we carried around to class like little trophies, paired with pencil cases filled to the brim with felt-tip brush pens and mildliners and Zebra Sarasa pens. Taking inspiration from multiple online sources—Pinterest and AmandaRachLee’s YouTube channel being our favorites—we meticulously drew every line and detail, essentially creating our own planners complete with carefully placed decorations. Each spread, perfectly detailed and aesthetically pleasing once finished, would take us hours to complete, and we giddily compared our finished results with one another afterward, marveling at our artistic prowess.

However, middle-school assignments and activities started racking up; time for bullet journalling started to decrease. We’d fall into the pattern of completing a month’s spread, forgetting about the journal for the rest of the month, and taking the hobby back up once it was time for next month’s spread. After an unspoken agreement, we abandoned our hobby altogether once we became more preoccupied with making the eighth-grade club basketball team. Our bullet journals began to gather dust in the bottom drawers of our desks.

Why had we labored for so long over those pages of calendars drawn out to razor-straight perfection, stickers, and decals tediously placed in order to best frame the spread, only to neglect the journals once it came time to use them? Was watching dozens of “bullet journal with me” videos and drawing along to them for hours simply a means of procrastinating my actual homework? Though I started to realize the futility of hand-drawing my own planner near the end of eighth grade, I couldn’t make myself buy a store-bought one. It felt like accepting defeat. After my bullet journal phase, I tried out different organizational platforms, expanding my reach online: Notion, Apple Calendar, even just a stack of sticky notes piling up on my desk. However, everything I tried seemed to reach the same result: As life got busier and assignments stacked up, I’d end up neglecting the platforms I spent hours organizing. Planning out the perfect semester with the perfect organizational system was the easy, exciting part; committing to the act was a lot more difficult.

Each academic phase of my life can be recounted through my attempts to plan them out. Sixth through eighth grade marked the

Bullet Journal period; ninth through tenth the Notion period; eleventh grade the Notes app and Sticky Note period. Though each of these eras started with the same bouts of initial motivation, the end results were the same. Notion templates detailing habit trackers for the next six months went unused; sticky notes with unchecked tasks started to pile up on my desk. By the time senior year rolled around, it was obvious that I’d hit some sort of planning wall—I’d entered the Memory and iPhone Reminders era, where I’d rely solely on my memory and the occasional iPhone reminder to get schoolwork done, a strategy further encouraged by senioritis. Fueled by the excitement of starting college, my first year at Brown marked the beginning of my Google Calendar period; though, admittedly, my calendar went blank with disuse near the end of each semester. (This was before I found out about the “repeat” option for events, but even then, I’d scarcely open the app.) Was it purely planner burnout that I was experiencing? Was it something deeper, as if not following through with using my organizational platforms was a way for me to further procrastinate on my tasks for the day? Was I simply destined to be a naturally unorganized person, no matter how hard I tried to present myself otherwise?

This year—my sophomore year—is the first that I’ve approached planning without an end-all-be-all approach. In other words, I’ve started to use planning for its convenience— not as an ultimatum determining my worth as a student, but through the “I’ll use this because it gets the job done” approach. Ironically, it’s only been through this method that I’ve been able to stick to planning consistently. The green hardcover planner I bought on Amazon for this year, coupled with Google Calendar for events and post-it notes for urgent tasks like “WRITE PAPER” in red ink taped on my desk, have been extremely helpful so far for planning out my year. Writing this almost four weeks into the semester, and given my previous track record, it’s honestly quite impressive that I’ve been able to stick to this system for so long.

Taking out the aesthetics and perfectionism from planning—check. Yet even though I now don’t associate any special meaning to my physical planner, I sometimes feel bittersweet when writing down reminders within the printed-out pages, marveling at how simple the task of planning is when it doesn’t also

entail enacting a DIY, custom-built vision. The journals I hand-drew in middle school still sit on my shelf, and I leaf through them from time to time, marveling at the labor and precision folded into each and every hard-pressed page. Though the planners I made didn’t end up actually helping me plan, perhaps they served another purpose: creating memories with my eighth-grade bullet journal buddies, giving myself motivation for a hectic semester ahead, or making use of the dozens of fancy pens and mildliners I’d ordered off of jetpens.com, my favorite stationary site. Perhaps they were the stepping stone to finding a method of planning that worked for me. Regardless, I’m grateful for these keepsakes, which seem to teleport me into my eighth-grade self doodling sunflowers while zoning out in Algebra II. Perhaps this was the purpose of them in the first place.

At Brown and elsewhere, you’ll come across the occasional GCal-er (i.e. person that uses Google Calendar religiously) with limited-tono blank space in their weekly calendars, and events color-coded so their calendar looks akin to a rainbow or a very colorful tapestry. But an important lesson to learn is that packed GCal or not, each and every planner is different, just as each and every person has a different method of organizing their tasks. Our own “task,” therefore, is to simply find a method best suited to our own needs; the act of planning doesn’t have to be a task in and of itself. An organized, hand-drawn planner with dozens of decorative stickers along its borders can work just as well

post- mini crossword by

Ina ma

1 2 3 4 5 6 8 7

Across Down 9

1. Brown University's furry club

5. Word ending that means "characteristic of," such as for fish?

6. Brooder, like your dog after a scolding

8. Brown's fursona

9. Do not do this at the zoo

1. Disney baby deer

2. Use: Lat.

3. Lacerate, as a bad cat might

4. Fandom location

7. What a deceased animal might do

Thank you for reading

New issues every week.

“As always, I was late for my 10 a.m., but as always, I took a few minutes to fill in my eyebags, color them black—black like the void, black like dread, black like a scream into a pillow, but also black like the ocean at night, black like two crows spinning in aimless circles against a clear blue sky, black like the darkness of your eyelids as you drift off to sleep.”

— Indigo Mudbhary, “why do you wear so much eyeliner?”

“My pillow cover is a violent red, supposedly a symbol of luck in Chinese tradition. It is a constant reminder of all the superstitious beliefs my mother has instilled in me. While some measures I can’t help but feel burdened by, her act of changing my bedsheets (oblivious to her intentions) to brown ones the night before opening my acceptance letter to Brown, has softened my heart for her little gestures.”

— Gabi Yuan, “red cover” 09.28.23

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Emilie Guan

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Elaina Bayard

Section Editors

Anika Kotapally

Chloe Costa Baker

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

AJ Wu

Section Editors

Lizzy Bazldjoo

Sasha Gordon

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Gabi Yuan

Section Editors

Chelsea Long

Maxwell

Zhang

LIFESTYLE

Managing Editor

Daniella Coyle

Section Editors

Hallel Abrams

Gerber

Nahye Lee

POST-POURRI

Managing Editor

Michelle Bi

Section Editor

Tarini Malhotra

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Junyue Ma

Lesa Jae

COPY CHIEF

Jessica Lee

Copy Editors

Indigo Mudbhary

Lindsey Nguyen

Rebecca Sanchez

LAYOUT CHIEF

Amber Zhao

Layout Designers

Emma Scneider

Emma Vachal

James Farrington

Tiffany Tsan

SOCIAL MEDIA

Rebecca Sanchez

Yana Giannoutsos

Yeonjai Song