The Official Publication of the Illinois Nurses Foundation Quarterly publication direct mailed to approximately 4,500 RNs and electronically via email to 90,000+ RNs in Illinois.

The Official Publication of the Illinois Nurses Foundation Quarterly publication direct mailed to approximately 4,500 RNs and electronically via email to 90,000+ RNs in Illinois.

The 24th annual Student Nurse Political Action Day (SNPAD) was held on April 5, 2022, at the Bank of Springfield Convention Center in Springfield, Illinois. Each year, SNPAD brings together nursing students from across the state for a day of learning, networking, and advocacy, and this year was no exception. Over 650 nursing students from 26 schools attended (see list below). The event is again supported by a generous gift donated in 2013 by the former Chicago Nurses Association. This year, a big THANK YOU to our lunch sponsors, Illinois HIV Care Connect, U.S. Navy, and Saint Xavier University School of Nursing and Health Sciences. Mennonite College of Nursing at Illinois State University was honored at the event for having the largest number of students attend, with over 100 students present. This annual event continues to excite and inspire students and has become a tradition for several colleges across Illinois.

This year ANA-Illinois launched an interactive event app to encourage member interaction. The app was incorporated into a photo contest that took place throughout the day, with each photo posted counting as an entry to win $100. Thank you to the many students and faculty that participated, and congratulations to the contest winner, John Moushon from St. John’s College of Nursing. The event also held its annual poster contest, with this year’s theme being “Self-Care as an Ethical Obligation for Nurses.” Congratulations to the 1st place winner Ally Pruser from Millikin School of Nursing, and 2nd place winners Kimberly Spencer & Abigail Bam, also from Millikin.

We appreciate Loyola University Medical Center’s willingness to provide STOP THE BLEED Hands on Skills training to students and faculty in attendance. Hands on skills classes took place in the morning prior to the start of

the formal presentations. Over 100 students participated in the hands on workshop. The number one cause of preventable death after an injury is bleeding. A bleeding injury can happen anywhere. Life-threatening bleeding can happen in people injured in serious accidents or disasters. The training helped to prepare the participants to become an immediate responder to STOP THE BLEED.

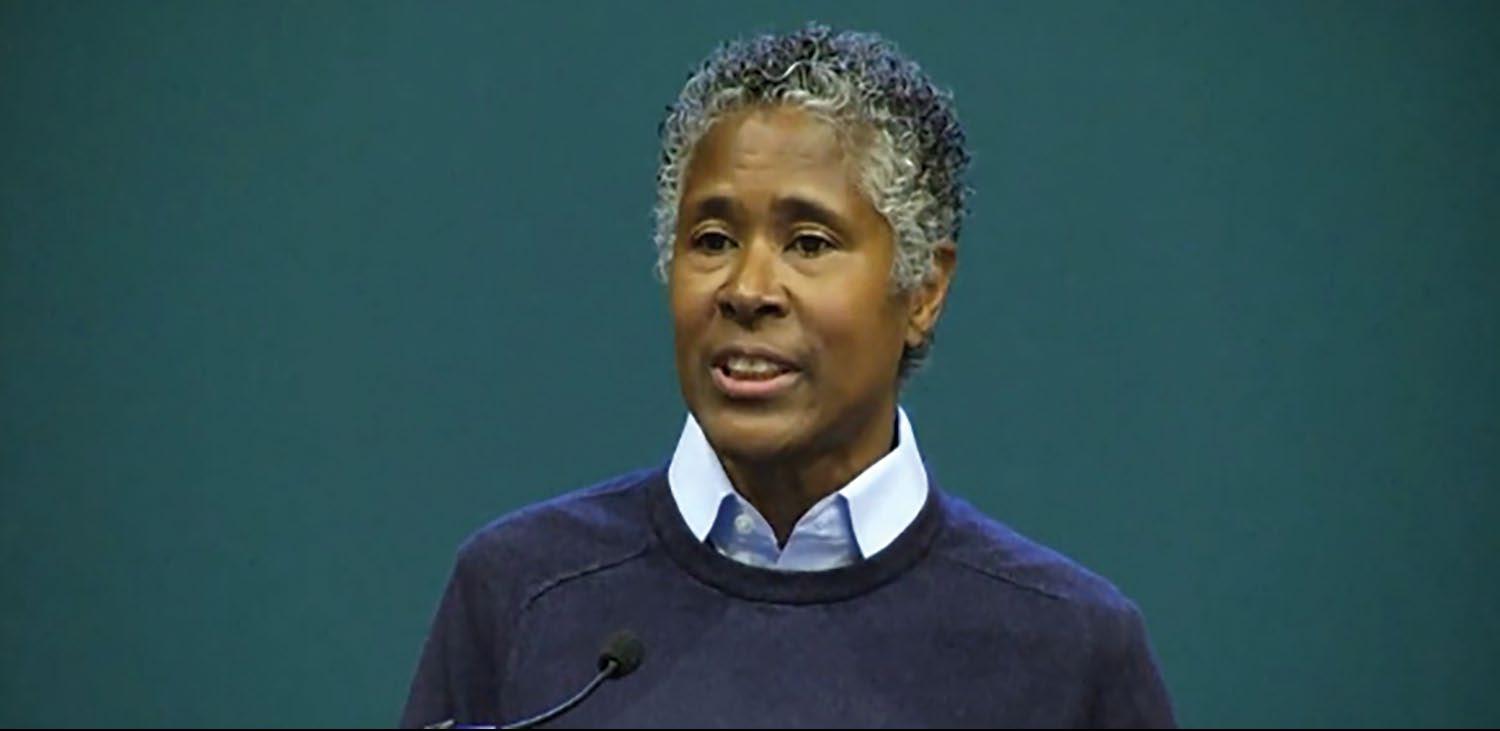

Students spent time visiting with exhibitors throughout the morning before our keynote event. Dr. Elizabeth Aquino PhD, RN - President, ANA-Illinois served as the emcee for the day! The keynote address was given, Feyifunmi 'Feyi' Sangoleye PhD, RN. Feyi's inspirational session focused on finding balance in chaotic times, giving great advice to both students and faculty. Throughout the day, nurse leaders presented various topics, including advocacy, healthy stress management, and getting involved with nursing associations, including ANA-Illinois and the Student Nurse Association of Illinois (SNAI).

After lunch, Debbie Broadfield and Kristin Rubbelke from Capitol Edge Consulting provided an update on what’s happening in the 102nd General Assembly. This session included an update on important bills and issues that are being addressed during the 2022 Legislative Session.

The event closed with the selection of the SNPAD Scholarship Recipient. ANA-Illinois selected one student attendee for a $500 scholarship. This year's recipient was Rush University College of Nursing student, Alyssa M. Persons.

Thank you to all students and nurses who made the 2022 SNPAD an overwhelming success. Whether the topic was advocacy, public health, or healthy stress management, many attendees contributed insightful comments on these topics. They helped to bring awareness to some of the major issues in nursing.

A big "thank you" to all of our sponsors for their financial contributions.

List of colleges participating in SNPAD 2022:

● Blessing-Rieman College

● Carl Sandburg College

● Herzing University

● IECC - Frontier Community College

● Illinois College

● Illinois State University - Mennonite College of Nursing

● Illinois Wesleyan School of Nursing

● Indiana Wesleyan University

● Lewis & Clark Community College

● Lewis University

● Loyola University - Marcella Neihoff School of Nursing

● Malcom X City Colleges of Chicago

● Methodist College – Unity Point Health

● Millikin University

● Northern Illinois University School of Nursing

● Oak Point University

● Purdue Northwest University College of Nursing

● Rush University College of Nursing

● Saint Xavier University School of Nursing and Health

Sciences

● St. John’s College of Nursing

Student Nurse Political Action Day...continued on page 4

The Illinois Nurses Foundation’s Editorial Committee would like to get feedback from our Nursing Voice readers. The brief survey will help the committee better tailor our content to our readers wants and needs. We appreciate you taking a few minutes to complete our survey at the link below or QR code.

https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/FS2Y3W9

Summer is just around the corner, which is hard to believe with snow still on the ground in mid-April. May was a time to celebrate Nursing with Nurses Week celebrations and activities. The message from the American Nurses Association for Nurses Week was “Nurses Make a Difference.”

Cheryl Anema PhD, RN

This is such a true statement and concept! Without nurses there would be no hospitals. Think about it. Why are there hospitals? Because clients need nursing care. We have outpatient clinics, outpatient surgical centers, outpatient care centers. But when someone needs ongoing care and observations, they are admitted to hospitals and other facilities for 24/7 care by nurses.

Nurses are teachers, caregivers, advocates, leaders, policy makers, influencers, and specialists at client care. Nurses DO make a difference! Where would we be without nurses?

As we look to today and our future, we know that many of our “baby-boomer” nurses and nurse faculty

members are retiring. There are more nurses leaving the profession than entering the profession which is leading to a crisis in nursing and nursing education. When adding in the factor of Covid and nursing burnout, the nursing profession needs to look at where we are at and be creative in our strategies to meet the healthcare needs of our clients. What can we do to provide resources for those individuals who have a desire to help others, to care for others, to become a professional nurse?

The IL Nurses Foundation is looking to expand its support of nursing students, in an attempt to decrease the burden on students and improve the ability for some otherwise underprivileged individuals, to afford a nursing education. We would also like to look at ways to increase the availability of nursing faculty, mostly through additional graduate scholarships.

This is where each of you come in. As a Foundation, we are a 501C3 philanthropic organization. All donations we receive could potentially be a tax donation for our donors. We do not have a membership fee or steady stream of income. Our income comes through our fundraising events and individual and corporate donations. Please Help US Help Nurses. Please consider a small monthly donation, even $10 / month goes a long way with the Foundation. Go to www.illinoisnurses. foundation/donations/ and make your donation today.

INF Board of Directors

Officers

Cheryl Anema, PhD, RN

Brandon Hauer, MSN, RN

Karen Egenes, EdD, RN

Directors

Maureen Shekleton, PhD, RN, DPNAP, FAAN

Alma Labunski, PhD, MS, RN

Linda Olson, PhD, RN, NEA-BC

Amanda Buechel, BSN, RN, CCRN

ANA-Illinois Board Rep

Susana Gonzalez, MHA, MSN, RN, CNML

Jeannine Haberman DNP, MBA, RN, CNE

ANA-Illinois Board of Directors

Officers

Elizabeth Aquino, PhD, RN

Monique Reed, PhD, MS, RN

Jeannine Haberman, DNP MBA, RN, CNE

Beth Phelps, DNP, APRN, FNP, ACNP

Directors

Holly Farley, EdD, MS, RN

Susana Gonzalez, MHA, MSN, RN, CNML

Elaine Hardy, PhD, RN

Dorothy Kane, MSN, RN

Zeh Wellington, DNP, MSN, RN, NE-BC

Editorial Committee

Editor Emeritus

Alma Labunski, PhD, MS, RN

Chief Editor

Lisa Anderson-Shaw, DrPH, MA, MSN

Members

Deborah S. Adelman, PhD, RN, NE-BC

Linda Anders, MBA, MSN, RN

Cheryl Anema, PhD, RN

Ellen Bollino RN, MSN, ED, CEN

Kathryn Booth, MSN, RN, CNL, CSRN, NPD-BC

Nancy Brent, RN, MS, JD

Pamela DiVito-Thomas PhD, RN

Amanda Hannan MSN, RN

Phoebe Maholovich MSN, RN

Irene McCarron, MSN, RN, NPD-BC

Linda Olson, PhD, RN, NEA-BC

Lanette Stuckey, PhD, MSN, RN, CNE, CMSRN, CNEcl, NEA-BC

Executive Director

Susan Y. Swart, EdD, MS, RN, CAE

ANA-Illinois/Illinois Nurses Foundation

Article Submission

• Electronic submissions only as a word document attachment using current APA guidelines.

• Email: info@ilnursesfoundation.com

• Subject Line: Nursing Voice Submission: Name of the article

• Must include the name of the author and a title.

• INF reserves the right to pull or edit any article / news submission for space and availability and/or deadlines.

• If requested, notification will be given to authors once the final draft of the Nursing Voice has been submitted.

• INF does not accept monetary payment for articles.

Article submissions, deadline information and all other inquiries regarding the Nursing Voice please email: info@ilnursesfoundation.com

Article Submission Dates (submissions by end of the business day)

January 10th, April 10th, July 10th, October 10th

Advertising: for advertising rates and information please contact Arthur L. Davis Publishing Agency, Inc., P.O. Box 216, Cedar Falls, Iowa 50613 (800-626-4081), sales@aldpub.com. ANA-Illinois and the Arthur L. Davis Publishing Agency, Inc. reserve the right to reject any advertisement. Responsibility for errors in advertising is limited to corrections in the next issue or refund of price of advertisement.

Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement or approval by the ANA-Illinois and Illinois Nurses Foundation of products advertised, the advertisers, or the claims made. Rejection of an advertisement does not imply a product offered for advertising is without merit, or that the manufacturer lacks integrity, or that this association disapproves of the product or its use. ANA-Illinois and the Arthur L. Davis Publishing Agency, Inc. shall not be held liable for any consequences resulting from purchase or use of an advertiser’s product. Articles appearing in this publication express the opinions of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect views of the staff, board, or membership of ANA-Illinois or those of the national or local associations.

Dear Illinois Nurse Colleagues, I hope you are well and enjoyed the festivities of Nurses Month.

As the public begins to seemingly return to pre-pandemic activities, I know many of you continue to feel the strain of the pandemic in the clinical setting. Please remember many ANA resources are available to support you, including access to Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation, which engages and empowers nurses to improve their health with many resources and activities. You are not alone; we are here for you. We appreciate you and thank you for continuing to make a difference in the lives of your patients every day.

If you are looking for more ways to get involved with ANA-Illinois, there is an open call for nominations to serve on the Board of Directors including: Vice President, Treasurer, Directors, nominating committee, and ANA representatives. We are seeking nurses working in all settings and representing nurses across Illinois. I hope you will consider running for a position so that you may share your experiences and perspective to advance the mission of the organization. Please go to www.ana-illinois.org to learn more.

Let's continue to work together to celebrate and elevate one another and the nursing profession.

Sincerely,

President, ANA-Illinois

@LatinaPhDRN

ANA-Illinois Nominating Committee is seeking nominees for the ANA-Illinois Board of Directors for 2022.

Nominations are now being accepted for the following three positions:

• Vice President

• Treasurer

• 2 Directors

• 1 Director – Recent Graduate (to serve within 5 years post-graduation from a prelicensure RN program)

• 3 Nominating Committee Members

• 1 ANA Representatives

• 1 Alternate ANA Representative

All ANA-Illinois Members in good standing may apply.

All positions will commence immediately following the 2022 Membership Assembly except the Treasurer’s position which begins 30 days after the meeting per the bylaws.

Position Description

The Board of Directors shall have the authority delegated to it by the Membership Assembly, including the duty and power of acting for the membership in the intervals between meetings of the Membership Assembly, and other duties and powers as defined in the bylaws. Officers, Directors & Representatives shall be elected as follows by the membership to serve for two years or until their successors are elected. Alternates-ANA Representatives serve a one-year term.

The slate of candidates will be presented to the membership on August 3, 2022 . A virtual Candidates’ Forum will be hosted on September 9, 2022 at 6pm. The voting period begins on September 17 and ends October 1 . The new board of directors will be announced at the ANA-Illinois Membership Assembly on November 5, 2022.

Deadline for Nominations: Friday, July 15, 2022 at 11:59 pm.

For more information use this link https://bit.ly/3FcHqha or the QR code.

● Southwestern Illinois College

● Trinity Christian College

● Triton College

● University of Illinois Chicago, College of NursingSpringfield, Chicago, and Champaign Campuses

● Western Governors University

● Western Illinois University School of Nursing

THANK YOU to our SNPAD 2022 Sponsors:

• Chicago Nurses Association

• Illinois HIV Care Connect

• Saint Xavier University School of Nursing and Health Sciences

• U.S. Navy

THANK YOU to our SNPAD 2022 Exhibitors:

• Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing & Health Sciences

• Grand Canyon University

• Herzing University

• HIV Care Connect

• IDFPR/Nursing Workforce Center

• Illinois Association of School Nurses

• Illinois College

• Illinois Nurses Foundation

• Indiana Wesleyan University

• Loyola Medicine

• Memorial Health

• Northern Illinois University

• Purdue University College of Nursing

• RekMed

• Saint Xavier University

• Student Nurses Association of Illinois

• UIC College of Nursing

• University of Michigan School of Nursing

• Western Governors University - WGU

Provision 8 of the ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements (2015) states the “nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.” (ANA, 2015, p. 31). This provision addresses some of the ethical aspects of access to health care, which is an issue of health care equity and the care of vulnerable populations, and the need for nurses to collaborate with other health care professionals and providers to address barriers to health. One of the barriers to health care exists across the United States in small and rural communities.

Access to health care services in rural areas of the United States is limited, and can be very challenging. A recent report of the National Conference of State Legislators noted that there are “More than three-quarters of the populations or facilities with insufficient access to health care providers and

professionals in primary care, dental care or mental health (NCSL, 2020. 1). Americans in rural communities are more likely to travel farther distances to the nearest hospital than those who live in suburban or urban environments. In addition to longer travel times, there is often no public transportation that can be used to get to medical care services from rural areas. Health care services are limited in rural areas, and rural hospitals are closing due to lack of funding. Along with the economic fallout from loss of jobs, this directly decreases access to health care services.

Advance Practice Registered Nurses (APRN’s) are in a very critical position to provide health care services in the small and rural areas where hospitals have closed and where home care nursing services are not available. APRN’s provide home and community-based services and work with larger institutions to provide telehealth services. The growth of telehealth has exploded during the pandemic, enabling more people in rural communities to access health care. Policy waivers put in place during the pandemic expanded this access. Telehealth practices and modalities provide ways to increase access to healthcare in rural health. These include remote clinical services, videoconferencing, the internet, and other forms of electronic and telecommunications technology, including patient education. Telehealth improves access to providers and healthcare for patients who would have limitations due to the need to travel long distances. The expanded use of telehealth has been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mobile health clinics are an opportunity to expand health care access to rural communities, especially for primary and preventive care,

thereby reducing use of emergency rooms in lieu of traditional health provider visits. Other initiatives include the use of mobile apps that allow for monitoring of blood pressure, blood glucose, and emotional support for stress and sleep issues.

An option that states have for increasing health care access in rural communities includes expanding the scope of practice for APRNs through legislation and policy changes. A 2018 study that examined scope-of-practice regulations found no significant differences in rural health outcomes and quality when scopes of practice were expanded for nurse practitioners (Ortiz, J., et.al., 2018). In order to improve access, policymakers and states should remove restrictions to practice for APRNs and allow them to practice within their full scope of practice (Buerhaus, 2021).

References

American Nurses Association (2015). Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements. Silver Spring, MD: NursesBooks.org

Buerhaus, P. (2018). Nurse Practitioners: A solution to America’s primary care crisis. American Enterprise Institute. National Conference of State Legislators, 2020, Improving rural health: state policy options for increasing access to care. 1-6.

Ortiz, J., Hoffler, R., Bushy, A., Lin, Yi-Ling, Khankjahani, A., & B., A. (2018). Impact of nurse practitioner practice regulations on rural population health outcomes. Healthcare, 6(2). Available: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare602065

Question

A reader asked what constitutes “unprofessional conduct” by a nurse under The Illinois Nurse Practice Act and its Administrative Rules.

Answer

Including all the possible behavior that might encompass unprofessional conduct is well beyond the scope of this Practice Corner. Moreover, it is the Illinois Board of Nursing that ultimately decides what behavior is considered to be unprofessional.

However, for the purposes of this Practice Corner, I can share some information for you to consider about this phrase. The Illinois Nurse Practice Act (INPA) lists possible grounds for disciplining any nurse licensee. One possibility reads:

“Engaging in dishonorable, unethical, or unprofessional conduct likely to deceive, defraud or harm the public, as defined by rule” (225 ILCS 65/70-5(7)).

Section 1300.90 of the Administrative Rules further define unethical or unprofessional conduct. The Section clearly states that the examples listed are not the only acts or practices which might be considered unethical or unprofessional conduct. Some listed include:

“Engaging in activities that constitute a breach of the nurse’s responsibility to a patient;”

“Engaging in behavior that crosses professional boundaries (such as signing wills or other documents not related to client health care);”

“Engaging in activities that cause actual harm to any member of the public;” and,

“A departure from or failure to conform to standards of practice as set forth in this Act or in this Part. Actual injury to a patient need not be established.”

In addition, incorporated by reference in this Section are the ANA’s 2015 “Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements” and the 2007 “Standards of Practice and Educational Competencies of Graduates of Practical/Vocational Nursing Programs” by the National Association for Practical Nurse Education and Service, Inc.

The examples listed alert you of conduct to avoid in your practice of nursing and in your relationship to patients. However, unprofessional conduct can, and has, been expanded to include acts outside of a direct connection to nursing practice.

One such instance includes being convicted of driving under the influence (DUI).

The reasoning behind the expansion of the definition of unprofessional conduct in nurse practice to non-clinical acts is that once licensed as a nurse, which is a privilege and not a right, you must act as a professional person in all walks of your life.

“Off duty” unprofessional conduct raises questions about your decision-making in being involved in such conduct, which indirectly may raise questions about your ability to practice nursing safely, competently, and with your patient’s best interest in mind.

Moreover, the public’s perception of nursing can be negatively impacted when unprofessional conduct unrelated to your nursing practice is involved and you are identified as a nurse.

Keep in mind that other listed grounds for disciplinary actions in the Act or the Rules that do not involve nursing practice may be charged against a nurse and those other grounds may form the basis of an additional charge of unprofessional conduct.

As an example, a standalone ground for disciplining your license is a failure to file and/or pay Illinois state income taxes. In addition to charging you with this misconduct, unprofessional conduct may also be added.

All disciplinary actions by the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation against nurses (and other professions the Department regulates) are available online at: idpfr.com/News/Disciplines/DiscReports.asp. You might want to review some of those reports to determine which disciplinary actions were solely based on the nurse licensees’ nursing practice and which were not.

Disciplinary actions by the Board of Nursing include, but are not limited to, refusing to renew a license, revoking a license, suspending a license, placing a license on probation, and assessing a fine.

Ways in which you can avoid an allegation of unprofessional conduct by the Illinois Board of Nursing include:

• Know and adhere to the Illinois Nurse Practice Act and Rules

• Keep current on any updates or changes in the Act and Rules

• Conduct yourself professionally at all times, not only when practicing nursing, but also when you are “off duty”

• Know and incorporate into your practice the tenants of your applicable Code of Ethics

You can read the entire Illinois Nurse Practice Act and its Rules by going to: https// www.ncsbn.org/npa. Place “Illinois” in the State Search Bar and the Act and its Rules will be accessible.

THE PRACTICE CORNER IS DESIGNED FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND IS NOT TO BE TAKEN AS SPECIFIC LEGAL OR OTHER ADVICE. SHOULD SPECIFIC ADVICE BE NEEDED IN A PARTICULAR SITUATION OR INCIDENT, THE READER IS ENCOURAGED TO OBTAIN ADVICE FROM A NURSE ATTORNEY, ATTORNEY OR OTHER APPROPRIATE PROFESSIONAL IN THEIR STATE.

McKayla Weis, MSW, LSW Program Coordinator Carle Advance Care Planning

While most individuals don’t anticipate difficult healthcare decisions needing to be made for themselves or their loved ones, that time will inevitably come for most people, so the sooner planning starts, the better.

Research indicates the undesirably low rate at which “approximately one in three US adults completes any type of Advance Directive” (Yadav et al., 2017, para. 25) instructing on their future healthcare. However, contrary to popular belief, Advance Care Planning is not exclusively about the completion of Advance Directives.

A consensus definition of ACP exists describing it as “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care” (Sudore et al., 2017); as collectively developed by a large multidisciplinary expert Delphi panel (Sudore et al., 2017). This unified definition further specifies how “the goal of advance care planning is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness’’ (Sudore et al., 2017) which critically enmeshes the multitude of conceptual variations that exist in ACP.

As ACP is not solely about end-of-life, an unexpected accident, sudden illness, or surgery are examples of events when one may not necessarily be near end-of-life, but information gathered during ACP is utilized to provide medical care until the person is well again. Conversations are tailored to each individual addressing healthcare decisions that could

need to be made yet simultaneously examining how their preferences play a role. This interactive process is generally done through self-reflection on one’s preferences followed by engaging with trusted persons to share key information.

For the Advance Care Planning team at Carle Health, educating and assisting with this process for patients in rural and outlying communities is something that always remains forefront. People in rural and outlying areas face unique challenges such as transportation, access to certain medical providers, limited social services, and distinct cultural-socio-economic dynamics within their inner circles that can impact how or when they seek healthcare.

To reduce the constraints on patients, Carle has roughly 80 employees trained across the system as certified facilitators who can competently yet sensitively start this type of planning and conversations with patients and other family members. Adult patients may be asked during routine appointments if they would like to meet with a facilitator to talk about Advance Care Planning, learn how to designate a power of attorney for health care, and how to make their wishes known.

Carle Health has invested in developing multifaceted ACP services that include one-to-one primary care inoffice visits for rural and outlying clinics, telephonic appointments, monthly virtual group sessions, and community gatherings at public libraries, church events, or hosting a booth at the local farmers market. Patients can request an ACP visit or informational materials by phone, email, online, in person, or through the MyCarle patient portal. Visits can be held using virtual resources so patients can stay right at home, while written information is sent directly to them via USPS or email. Offering multiple modalities

for ACP visits and resources allows patients to choose the method that works best for them based on their needs and capabilities.

The ACP team is continually exploring opportunities for bringing ACP services closer to patients’ homes than they would otherwise be able to access and patients are encouraged to utilize the service option of their choice. Efforts to offer services closer to where rural patients live, or even from within the home utilizing virtual options, provides the opportunity to more easily engage in ACP by reducing barriers. Whichever method patients choose, they can feel confident in seeking the value and wealth of benefits that ACP provides for their future care.

Visit carle.org for more information on how Carle Health is redefining healthcare around you.

To learn about Advance Care Planning at Carle Health, visit carle.org/ACP

References: Sudore, R., Lum, H., You, J., Hanson, L., Meier, D., Pantilat, S., Matlock, D., Rietjens, J., Korfage, I., Ritchie, C., Kutner, J., Teno, J., Thomas, J. & Heyland, D., 2017. Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel (S740). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53 (2), 431-432. Yadav, K. N., Gabler, N. B., Cooney, E., Kent, S., Kim, J., Herbst, N., Mante, A., Halpern, S. D., & Courtright, K. R. (2017). Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Affairs, 36 (7), 1244–1251. https://doi.org/10.1377/ hlthaff.2017.0175

On Tuesday, March 29th, ANA-Illinois Executive Director Susan Swart, EdD, MS, RN, CAE, addressed the nursing shortage with the Illinois Senate Health Committee. She urged the committee to address the shortage—at all levels of nursing—that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic.

“While the nursing shortage is not just an Illinois issue, the pandemic has laid bare the issues facing the profession,” says Swart.

Nursing Shortage by the Numbers

Based on the 2020 RN workforce report prepared by the Illinois Nursing Workforce Center, Illinois will face a shortage of nearly 15,000 RNs by 2025.

Plus, while 52% of the almost 195,000 RNs in Illinois are over the age of 55—with 27% planning to retire in the next five years—less than 8,000 nurses graduate each year.

“There is no easy fix to the nursing shortage, and we have an urgent need for workforce planning to meet future healthcare needs,” says Swart.

ANA-Illinois Recommendations to the Senate Health Committee

Some of the recommendations Swart presented include the following:

• Require workforce-related collection data at the time of license renewal to give a more complete picture of the nursing workforce

• Pass the Nurse Licensure Compact to remove barriers to nurses working in nearby geographical areas and protect current Illinois Nurses while performing interstate practice via telehealth

• Increase focus on nursing education by increasing enrollment and funding faculty investment

• Invest in nursing programs and provide loan forgiveness to nurses

• Allow new graduates and student nurses to practice with limited, temporary licenses under the supervision of an RN

• Address the salary of nurses at all levels

Schools, Long-Term Care & Hospitals Identify Needs & Make Recommendations

Swart’s panel included two other experts. Glenda Morris Burnett, PhD, MUPP, RN, Assistant Professor at Rush University, who shared about the dire need for investment in nursing faculty. Gloria E. Barrera, MSN, RN, PEL-CSN, presented on the high need for school nurses.

In panels that followed, experts in long-term care and hospital administration spoke on the efforts they’re making to increase pay and benefits to retain their staff.

“The workforce challenges we’re facing will require investment and that will require buy-in from everyone involved and thinking outside the box,” says Swart. “Failing to invest in the nursing workforce will cost systems and our state greatly and delay progress on our goals for health equity and improved outcomes.”

Nurses want to provide quality care for their patients.

The Nurses Political Action Committee (Nurses- PAC) makes sure Springfield gives them the resources to do that.

Help the Nurses-PAC, help YOU!

So. . . . . . . if you think nurses need more visibility if you think nurses united can speak more effectively in the political arena if you think involvement in the political process is every citizen’s responsibility.

Become a Nurses-PAC contributor TODAY!

❑ I wish to make my contribution via personal check (Make check payable to Nurses-PAC).

❑ I wish to make a monthly contribution to NursesPAC via my checking account. By signing this form, I authorize the charge of the specified amount payable to Nurses-PAC be withdrawn from my account on or after the 15th of each month. (PLEASE INCLUDE A VOIDED CHECK WITH FORM)

❑ I wish to make my monthly Nurses-PAC contribution via credit card. By signing this form, I authorize the charge of the specified contribution to Nurses-PAC on or after the 15th of each month.

❑ I wish to make my annual lump sum Nurses-PAC contribution via a credit or debit card. By signing this form, I authorize ANA-Illinois to charge the specified contribution to Nurses-PAC via a ONE TIME credit/debit card charge.

❑ Mastercard ❑ VISA

Credit card number Expires CVV

Signature:

Date:

Printed Name:

E-Mail:

Address:

City, State, Zip Code:

Preferred Phone Number:

Please mail completed form & check to:

ANA-Illinois

Atten: Nurses-PAC PO Box 636 Manteno, Illinois 60950

Nursing Career Path

At Amedisys, we build on skills throughout our careers and provide opportunities for growth with ongoing training and support. Join our family and see how you can step into a new role and make a difference today! Learn more at amedisys.com/careers.

A typical nursing student’s day … 7:00am and I wake up from an eight-hour restful sleep, to the aroma of freshly brewed coffee. I see on the breakfast table a toasted piece of bagel with creamy butter slowly melting on it, and yes, eggs and crispy bacon. I turn on the TV and hear news about forgiveness of student loans, special low-cost housing for new grads, and guaranteed employment in a hospital of our own choice. Good news indeed! I have a simulation class in an hour but I’m just five minutes away from campus. I have prepared for a quiz; I have completed my assignments at least a week in advance. I have time to go shopping before I head to school. wwPOP!

In reality, we woke up this morning to face just like any other busy day. Some worked the night shift. Some are rushing to drop off their kids to daycare or to grandma. Most, if not all, are juggling work, family and other responsibilities before they can think of the pressing deadlines of schoolwork. There are no eight-hr restful sleeps nor breakfast waiting at the table, nor the luxury of watching the news, much less good news. Many drive tens of miles to get to campus or to the clinicals. We never had time to adequately prepare for an exam or even an assignment. We barely had time to sleep … for whatever is left of school responsibilities, it is spent on work, family, and last and the least, self.

As we stand here today, we feel a sense of accomplishment. Yet, we are still living in the days of a pandemic, global unrests brought about by an ongoing war, economic instability, employment insecurity, and other uncertainties. How will we find our place in the vast arena of the nursing profession? The news of a Tennessee nurse deeply trouble us, are we prone to the same risk of human error? Will we be protected by socalled “Culture of Safety” practices? A looming global war, will be caught in its crisis challenge? The NCLEX worries, will we succeed?

Our instructors have tirelessly and generously given us not only the tools, instructions, tips and techniques needed in order to learn effectively; they have given us their precious time. They have shared with us an abundance of personal experiences we can learn from. They went above and beyond the call of true mentorship for us to hurdle past disappointments, frustration and even fatigue. They cheered us on, they gave us many chances to pass our unit exams and excel in every academic challenge we faced. They listened to us, not just to problems about our PICOT projects or care plans, or clinicals, but to our personal woes as well. To you our teachers, we can never thank you enough.

Our families, loved ones, and friends likewise labored with us just so we can go past a challenging week of exams and other activities. They drove us to where we needed to be. They cooked us a meal, they helped us with childcare, and even provided us with other material needs. Most of all, they helped us to stay emotionally balanced. They prayed for us, cheered us on as well, and lifted our spirits up when we felt like giving up. You too have our deep gratitude, and we can never thank you enough.

And to you classmates, we stand together today because we committed to work together to get to this day and reach our goal. Many more challenges lay ahead. But the camaraderie we developed, the training we went through together, the times we spent working on our group projects, review sessions, virtual meetings and other activities have bonded us to emerge hopeful for our future as nurses.

Yes, somehow, amidst the realities of medication errors, or raging wars, pandemic and all, we will find our niche in this arena that we have chosen. We have received the training, the discipline, the self-determination needed to succeed. To our Alma Mater, our instructors, families, and friends, thank you for the overwhelming support you have given us. As we look forward and beyond, to you classmates, I say, let us put on our sunglasses, our future is bright!

Acknowledgment:

I would like to thank Dr. Deborah Adelman, PhD, RN, NE-BC, for her assistance with edits, review, and overall presentation of this article. Her work and encouragement has inspired me to write and share my experiences.

It was 11:30 p.m. I was just getting ready to don my pajamas and climb into bed knowing that I would have a long day of work ahead when I was called over the 2-way radio, “Lauren, Code Brown in Cabin 1.” I knew this would mean a good hour of helping clean up a camper but little did I know the impression this would leave on me and others on my team. I hurried to the cabin where I found the camper in bed with his volunteer at his side. The camper was lying in a pool of sweat as a result of autonomic dysreflexia, completely drenched, shaking from spasms and near hypothermia and yet still putting on his brave face and having a good attitude as he thanked me for helping him. I knew this was no ordinary experience and no ordinary place.

I am a registered nurse and I run an adapted camp for adults with traumatic spinal cord injuries (SCI) located in rural Indiana. I founded the camp in 2014 and have run it as the CEO and medical director since. Initially, the camp was started for those with physical disabilities, and the camp transitioned into one that focused solely on those with traumatic spinal cord injuries. The camp is a unique place where young adults with this condition are able to travel to a rural location and enjoy the outdoors while all medical care is provided for them. An opportunity like this presents many challenges, starting with training both professional and lay volunteers so that they are prepared for any emergent situations which can occur at the camp. A typical day at home for Individuals with SCI include many medical interventions (e.g., catheterization, bowel programs and digital stimulation, and frequent skin checks) that make up their daily routine care and these are also needed at camp. There are multiple medical situations that must be addressed with this population. All of these issues combined with being in a rural setting can present many challenges as well as opportunities for creativity and resourcefulness. Preparedness is vital to camp week success.

Autonomic dysreflexia

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD), an uncontrolled episode of increased systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more that is often accompanied by bradycardia, is a daily concern in the best setting and dangerous in a setting located far from emergency help if needed (Morgan, 2020). AD can be caused by anything from overheating to having a clogged catheter tube, and is seen in anyone who has an injury at the T6 level or above. Noxious stimuli below the level of the injury can increase blood pressure and cause a person to have a cerebral or spinal stroke, seizures, or pulmonary

edema if the stimuli is not removed quickly due to the inability of spinal cord signals to cross to the brain. In a typical individual, the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems provide balance but for someone with a spinal cord injury, these systems do not work in sync (Morgan, 2020).

When having an episode of autonomic dysreflexia, a camper may sweat above their injury site, have increased spasms, feel lightheaded, or suddenly feel like they are going to vomit. This is due to a pain stimulus that is rapidly firing but not reaching the brain due to the injury. This requires quick action on the part of the healthcare provider. The best way to treat this quickly is to know each camper’s specific needs and norms, and what their triggers for autonomic dysreflexia tend to be. It is very important to trust the camper and listen to their instructions when they say they are not feeling well as they live with these issues every day and they know best what works for them. Reverse full body checks are typically the best way to resolve these issues, checking each camper from their feet to their head with concentration on their bladder and bowel needs.

The main causes of autonomic dysreflexia are issues with urination, bowel elimination, and pain, called the “3 P’s” of pee, poop, and pain. These should be checked first. If the patient does intermittent catheterization, they should self-catheterize or the healthcare provider should catheterize them. If they have a suprapubic catheter, they should make sure that the catheter is not clogged. They may need to flush the catheter to ensure it is flowing without obstruction and no sediment is blocking it. Pain is also a consideration. The camper’s toes may be curled inside their shoes. Their feet may not be in the right position. Their pants may have a wrinkle or crease that the camper is sitting on. They may have gotten injured or scraped and not realized it, or they may need to change positions in their wheelchair. If no cause can be identified quickly, a rapid dose of blood pressure medication, such as nifedipine, should be administered to return the blood pressure to an appropriate level. Upon arrival at camp, healthcare providers must ensure that campers arrive with the medication they would use at home, keeping it on or near the camper in case of an emergency.

Autonomic dysreflexia is a daily part of life for many with spinal cord injuries. For others, it only occurs occasionally. Regardless, its effects can have devastating consequences if not treated quickly and efficiently. Many patients with SCI are afraid to go to clinics or the emergency room when they experience an episode of autonomic dysreflexia because they fear that their providers do not know what it is or how to treat it. In the camp setting, having this knowledge not only equips healthcare providers for providing appropriate care, but it also allows campers to have an amazing outdoor experience, and helps provide the best, safest, and highest quality care to these campers.

Temperature Regulation

Temperature regulation is a serious problem for patients with high level cervical SCIs who can overheat from the lack of ability to sweat appropriately or they become cold from the inability to self-regulate. Decreased muscle mass in combination with a lower blood pressure and inability to sweat below the injury level make temperature control difficult (Price & Trbovich, 2018). Because most activities of the camp are outdoors and during summer months, this is something that has to be planned for. This includes making sure the campers have water sprays to cool off or have personal fans. Campers need to have wheelchairs that are covered when not occupied as they participate in the most strenuous activities. These activities are best performed during morning hours when the temperature is cooler. They should also have overhead tents to sit under in areas that are in full sunlight. When considering the other extreme condition of hypothermia even in the summer time, it also means having someone check cabin temperatures each night so that the campers do not get too cold. Camp staff and attendants must ensure that the campers dry off quickly after showers or after spending time in a pool or lake. Campers are also instructed to bring plenty of warm pajamas or blankets for nighttime. Since many of the campers have no sensation in parts of their body, volunteers and medical professionals have to be aware of the campers’ body

temperature. They must physically touch their skin to check temperatures as well as watch for other cues such as increased spasms or changes in skin color. Attention to these important cues can prevent bigger issues from arising and are extremely important in rural medicine as monitoring equipment is not available.

Syncope is an issue well known to the population with spinal cord injuries. Campers with spinal cord injuries often have very low blood pressure. Blood pressure as low as the 90s/50s is not uncommon, thus, activities such as those that increase dehydration, or cause them to hold their breath such as when singing, and those that involve overexertion, and changes in elevation can cause them to pass out. Because the sympathetic response to the heart is affected after SCI, the parasympathetic system, especially the vagus nerve, controls the heart functions (Taylor, 2018). This causes individuals with SCIs, especially those involving high level cervical SCIs, to have a low resting heart rate. This low heart rate combined with a loss of sympathetic control of the vasculature and kidneys leads to a low blood pressure (Taylor, 2018). Those with high level SCIs cannot easily compensate for changes in blood pressure which can cause their syncope.

Healthcare providers need to be aware that this could happen quickly and need to be ready to do a chest rub if necessary, check vital signs, and provide increased hydration. In these cases, it is important to know the camper’s norms. If they pass out frequently, continuous monitoring and increased fluids are typically adequate to avoid further issues, but, if the camper has not passed out before or it is an unusual occurrence, emergency services need to be called. If in doubt, a call to emergency services is warranted every time. It should be noted that it can take 30 minutes or longer for EMS to arrive in rural areas, so the medical team has to be prepared to keep the patient stabilized until they come.

Pressure wounds can be devastating and leave the campers in bed for years waiting for a wound to heal. They can develop quickly since people with spinal cord injuries have limited to no feeling or sensation in their core or extremities, thus, unable to feel pressure, burns, or pain stimulus. Wounds can lead to infection, osteomyelitis, sepsis, and even death. Skin checks save lives for this population and are a part of everyday care to mitigate the chances of pressure wounds developing. Every night at camp, the medical team should do full body skin checks, examining every inch of the camper’s skin from head to toe. This is especially necessary for areas that are bony such as the back of the head, shoulders, elbows, back, hips, buttocks, backs of legs, and heels. Breasts, underarms, groin, and genitals are areas that harbor sweat and grow bacteria or yeast.

Regular checks allow treatment to occur quickly and prevent issues from escalating. These medical skills are honed in a rural setting, and campers rely on the medical team’s skills to help keep them safe and healthy.

There is often a misconception that because a person with a spinal cord injury has limited feeling or sensation, they cannot feel pain. This is far from the truth. People with spinal cord injuries may have nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, or both. Both types of pain can affect sleep, mood, and level of activity, with neuropathic pain significantly impacting sleep (Felix et al., 2021). Neuropathic pain can be caused by the injury itself and is often chronic, whereas nociceptive pain is the body’s response to pain stimulus. After SCI, the nerves still sense pain but the signal cannot get to the brain appropriately. This may result in severe neuropathic pain for some and for others it may result in feeling ill every day. There is often no treatment or cure and is a part of life for those with SCIs. Some campers take high amounts of pain medications, others use medical marijuana, and some prefer to cope with it rather than take substances that oftentimes make them feel worse. While medical marijuana is not legal in Indiana, other alternatives are used at our camp and may work for other camps across the nation. The best medical intervention that I have seen providers give for this pain is emotional support. Campers need to have this pain acknowledged and they need to be asked about it rather than have people assume it does not exist. Acknowledgement goes a long way in providing good healthcare.

Team Preparedness

In addition to medical preparedness, team preparedness is indispensable. Nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, and students in these fields may be working at a camp and need to function as one unit to provide camper care. The whole team also sees camp administrators working with them in any situation to provide proper and emergent care for the campers. At camp, nurses and physicians work side by side doing

urinary catheterizations, skin checks, medication administration, and bowel programs/digital stimulation. The work is entirely hands-on and every person has a role in providing that care. Physical therapists oversee all transfers and they teach other medical professionals how to safely move campers without getting injured themselves. At our camp, we have phenomenal physical therapists who individually worked with me to ensure that my transfers were safe and effective. This allowed me to fully participate in all aspects of camper care and provided me with skills that have continued to aid in my nursing career. It also showed the whole team and the campers that, as the camp director, I had an interest in being part of the team by providing hands-on care. When every team member works as part of a unit, teamwork becomes invaluable in providing the best, safest, and highest quality care, even more so in rural medicine when other resources are not readily available.

Team preparedness also involves intensive training. Each year before camp I conduct Zoom sessions with all volunteers. This involves all aspects of disability awareness, appropriate terms to use, safety protocols, medical needs, and wheelchair safety. We discuss how volunteers can help the medical team with skin checks and how to alert the team if they see issues before the nurses or physicians do. When the volunteer team arrives, they have intensive training with physical therapists to practice safe transfer skills. The medical team participates in this training as well so that they can help in all aspects of camper needs. The healthcare providers and volunteers work together as a team to provide best camper experience.

The medical team does additional online training. I provide education to teach many aspects of spinal cord medicine. This includes doing full body skin checks and treating autonomic dysreflexia episodes. Physicians have commented that “they learned more about rural care for SCIs from these trainings than they did in medical school.” Typically, two campers arrive at camp early and participate in the training so that they can tell camp care providers how their SCIs are different, and what medical needs they have. This provides camp staff additional perspective coming from the camper in addition to my healthcare program perspective. Many providers have said this combination training was practical and effective. We also added in-person bowel program/digital stimulation training. In here, two campers and I taught the medical team how to perform

bowel program. We provided teaching while the care providers demonstrated their skills. The campers share their daily life experiences and techniques in managing their situations while nurses and physicians get handson skills training.

Training is an essential component of the camp that I continue to develop each year. Future improvements will include:

• Meeting with local EMS teams to teach staff about the specific needs of patients with SCIs

• Dramatization of medical emergency and simulations with the volunteers and medical team;

• Having medical bag packing and unpacking relays so that every participant knows where to find all emergency items, and

• Having volunteers practice techniques of dressing/ undressing while incorporating skin care on mannequins before staff can provide hands on care with campers.

Every new aspect of training involves funding and many hours for training and development but it is always worth the time to improve medical knowledge and new care techniques.

Preparing for an adapted camp that is at least 30 minutes away from the nearest hospital involves a great deal of preparedness and mitigation efforts related to possible emergencies that go beyond those Continuing Education continued on page 16

200 Wacker Drive, Suite 3100, Chicago, Illinois 60606

Email: jgoldberg@jbglawfirm.com | Goldberglicensing.com

typical of a camp that does not deal with special-needs populations. Our camp is set up much like a small hospital with equipment that includes adapted shower chairs and Hoyer lifts, supply of over-the-counter medications, urinary catheters, suppositories, and other items for daily needs. Emergency medical bags including AEDs, blood sugar monitors, blood pressure cuffs, stethoscopes, first aid supplies, limb supports for injuries, and bandages are supplied for every camper group. Medical volunteers likewise are regularly trained in all aspects of medical care for adults with spinal cord injuries.

There are other pieces of equipment that are needed for providing adapted activities. These are provided by rental companies such as adapted sites rentals that provide many of these pieces of equipment. Our company has purchased some of our own as well. It has an adapted climbing tower where campers can sit in a special chair and be hoisted to the top or they use a special seat and hoist themselves up with just their arms. There are adapted sports chairs that campers can use for basketball, relays, and other games. We also use Bellyaks which is a cross between a kayak and a surfboard, enabling campers to paddle on the water using just their arms. We have archery equipment that is adapted for those with limited hand dexterity. Volleyball nets are lowered so that campers can play from their wheelchairs. At the pool, we use pool noodles and netted swim hammocks so campers can have as much independence as possible. We have card holders for card games and we provide plenty of games with thicker pieces such as Blokus that campers can play with if they have little hand strength. We also use a type of glove called Adapted Hands that allows campers with no hand dexterity to grip objects. A favorite part of camp week is an adapted dance where everyone dances together using whatever movement and abilities they have. At camp, I say that if the highest level quadriplegics cannot participate, we will not do an activity. All in all, there are very few camp activities that cannot be adapted to meet the needs of everyone.

The Most Important Aspects of Care

While medical knowledge, a good team, and adequate supplies are a must, the most important

aspect of providing care in rural medicine is the willingness to learn and to listen to what the campers tell us. A camper once told me, “You know more about me and my medical care than anyone else and you seem to be able to turn off my quadriplegia whenever you want to; but I still have to live with it and I cannot turn it off.” This made me evaluate my own perspective as well as I learn deeper empathy for the campers I serve. I have learned more about spinal cord injuries from the campers who have attended my camp than I did in any nursing program. Learning about their specialized needs encouraged me to do further searches, study more deeply about SCIs, and connect with others who have studied spinal cord injuries so that I could provide the best medical care and train my team to do the same.

The willingness to listen is a key to providing the highest quality care. Most individuals with spinal cord injuries live with other chronic issues every single day. Who better to alert the staff to potential issues that may occur or how to provide the care they specifically require than those who interact with them more closely? Many situations exist such as catheter leak, bowel accidents, pain that never goes away, sympathy given although often unwanted, social isolation that can become a norm, independence thwarted by overzealous bystanders seeking to do good without understanding the realities our campers live with each day. These issues cannot be fixed and there is no cure for what these individuals live with each day, but compassionate friends and medical staff who can normalize the unexpected can make the day much better and provide support that is more meaningful than medicine.

As I helped clean up our camper, he told me he felt bad that his care required late night work when he knew I was tired. Unbeknownst to him, that night changed many of us. I was able to tell him that I was doing what I loved doing and our team had an opportunity to work together which gave value to their roles. We worked together to take care of his medical needs, hugged him goodnight, and turned out the lights. His volunteer met me on my way out of the cabin and started crying, not out of pity but because he had seen firsthand the daily struggle and the strength of his camper that night. The volunteer told me that he would never treat people Continuing Education continued from page 15

We are currently moving to a new technology platform that, while it should make the renewal process easier for licensees in the future, has resulted in additional time being required for IDFPR to open license renewals online. Nurses, you will receive an email notifying you when the renewal period begins, and you will have an extended renewal deadline of August 31, 2022 (please see our variances for the nursing professions here: https://lnkd.in/ ekbAkWeb).

Please make sure your email address is up to date with IDFPR by logging in here: https://lnkd.in/gtNpVt8g In addition, nurses who renew their RN, APRN, and FPA-APRN license prior to the August 31, 2022, expiration date will have their renewal fee waived. Please note that those renewing late will be charged a late fee in accordance with existing Administrative Rules.

with disabilities differently again because he realized their value and the fact that any of us could have a disability or a spinal cord injury at any point and would want to have the best care. What our camper saw as an inconvenience that night, we saw as a blessing and a moment in time that we would treasure forever with a lesson we would never forget.

Camp medicine, just like any type of rural medicine, requires preparation and quality care. The medical team has to be prepared for anything. What they may not be prepared for are the lessons they will learn and the impact those patients will have on their lives.

References Felix, E. R., Cardenas, D. D., Bryce, T. N., Charlifue, S., Lee, T. K., MacIntyre, B., Mulroy, S., & Taylor, H. (2021). Prevalence and impact of neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain in chronic spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation [ahead of print]. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j. apmr.2021.06.022

Morgan, S. (2020). Management of autonomic dysreflexia in the community. British Journal of Community Nursing, 25(10), 496–501. https://doi.org/10.12968/ bjcn.2020.25.10.496

Price, M.J., & Trbovich, M. (2018). Thermoregulation following spinal cord injury. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 157, 799-820. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0444-64074-1.00050-1

Taylor, J.A. (2018). Autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical, 209, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2017.09.015

CE Offering

1.0 Contact Hours

This offering expires in 2 years: June 9, 2024

Learner Outcome:

80% of those reading the article and completing the post-test will self-report increased knowledge of the preparation necessary to care and treat camp participants with spinal cord injuries.

CONTINUING

This course is 1.0 Contact Hours

1. Read the Continuing Education Article

2. Go to https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/202206-043selfstudy to complete the test and evaluation. This link is also available on the INF website www.illinoisnurses.foundation under programs.

3. Submit payment online.

4. After the test is graded, the CE certificate will be emailed to you.

HARD COPY TEST MAY BE DOWNLOADED via the INF website www.illinoisnurses.foundation under programs

DEADLINE

TEST AND EVALUATION MUST BE COMPLETED BY JUNE 9, 2024

Complete online payment of processing fee as follows: ANA-Illinois members- $8.00 Nonmembers- $15.00

ACHIEVEMENT

To earn 1.0 contact hours of continuing education, you must achieve a score of 80%

If you do not pass the test, you may take it again at no additional charge

Certificates indicating successful completion of this offering will be emailed to you.

The planners and faculty have declared no conflict of interest.

Illinois Nurses Foundation is approved as a provider of nursing continuing professional development by Ohio Nurses Association, an accredited approver by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. (OBN-001-91)

CE quiz, evaluation, and payment are available online at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/202206-043selfstudy or via the INF website www. illinoisnurses.foundation under programs.

By Salah Issa (Salah01@illinois.edu) Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist; UIUC

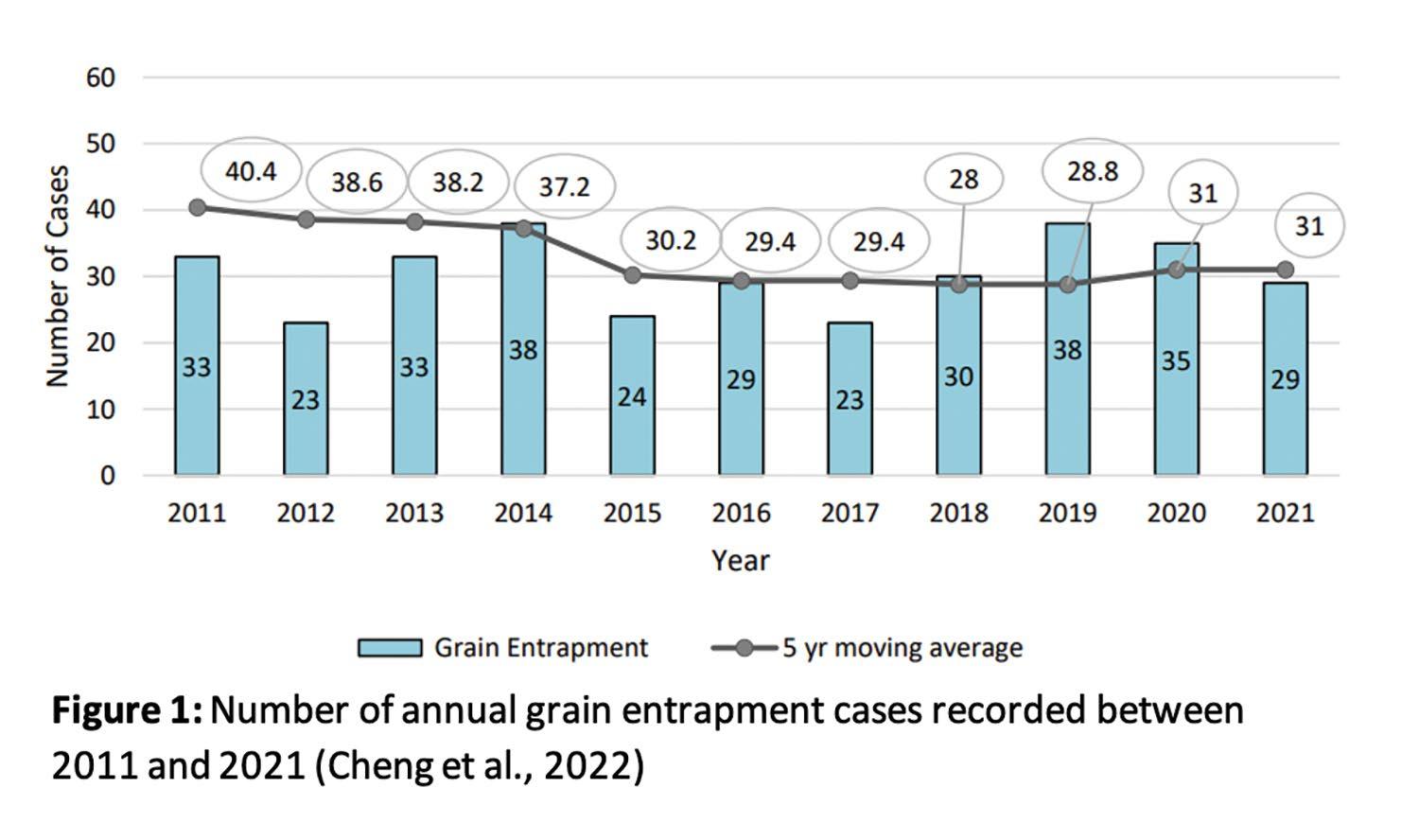

For the second year in a row, Illinois had the largest number of grain entrapments in the US with 10 in 2020 and another five in 2021 (Cheng et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2021). These 15 cases represent approximately one quarter of all cases reported in 2021-2022 by Purdue University’s Agricultural Safety and Health Program.

What are Grain Entrapments?

Grain entrapment is an agricultural injury in which a person enters a grain bin or silo to dislodge a blockage caused by out-of-condition grain and then becomes partially entrapped or fully entrapped in the grain (Issa et al., 2016). An entrapment in which the victim is completely under grain is known as engulfment. Every year in the United States, roughly 30 grain entrapments occur with on average about 50% of the people who become entrapped dying. From 1962-2021, more than 1,325 such incidents have been documented, but the number could be higher due to nonreporting (Figure 1; Cheng et al., 2021).

Cause of Entrapment

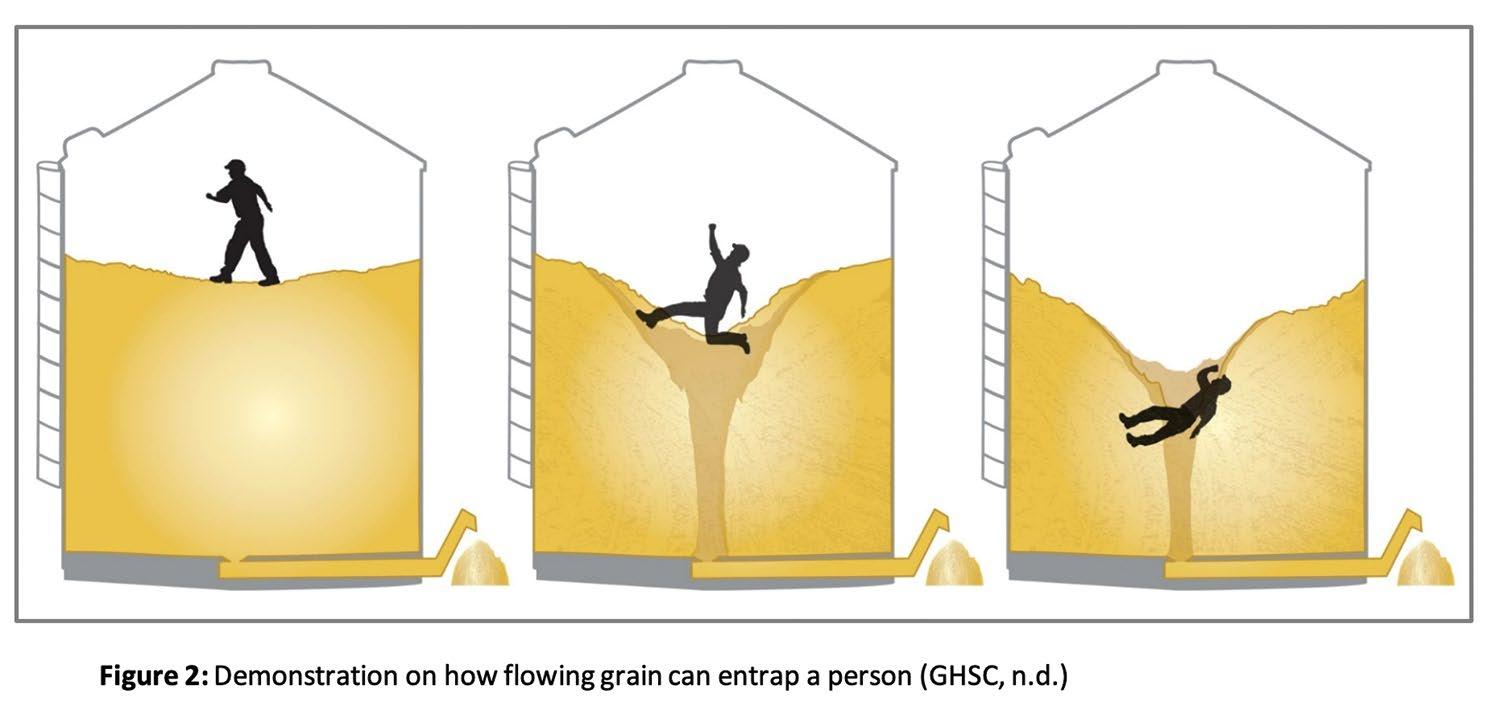

While there are seven different ways a person can get entrapped within grain, the most common method is getting caught in flowing grain (Figure 2). This usually occurs when a worker goes into a bin to either “walk the grain” or breakup grain stuck at the bin sump while the unload auger is left on. The worker either stumbles, gets too close, or reacts too slowly and in about 30 seconds is fully engulfed under grain (Roberts & Field, 2008). Approximately 70% of all documented grain entrapment cases are due to flowing grain of which approximately 63% end up being fatal (Issa et al., 2018). Even when the victim is only partially entrapped (i.e., head is exposed), 7% still die. This is probably due to grain pressure on the chest which is 50% to 120% greater than the pressure at which lungs can operate (Issa et al., 2017; Issa et al., 2018b; Deep Blue Diving, 2020).

Volunteers are need for our Holiday Gala & Fundraiser to be held at the DoubleTree by Hilton Lisle Naperville in Lisle on Saturday, December 3rd.

The 2022 Illinois Nurses Foundation Annual Gala Planning Committee is a group of individuals who work to support INF's largest fundraising event of the year that takes place every December.

Position Description:

• Responsible for sitting on the Gala Planning Committee to help with the overall success of the event

• Secure auction items for both the raffle and online silent auction

• Promote the gala to friends and colleagues

Position Start Date: June 20, 2022

Time Commitment:

• Approximately 1 hour every other week from home, however time commitment may vary.

• Attend committee meetings virtually or by phone once a month. Additional committee meetings may be added as the event approaches.

Preferred Skills and Additional Details:

• Enthusiasm for planning a charity event

• Experience fundraising or soliciting auction items and prizes

Can't serve on the committee? Other options to support the event include making a donation to the raffle and/or online silent auction.

Please indicate your willingness to help by completing this survey (link or QR code)

https://bit.ly/2022INFGALA

Preventative Measures

It is important to note that the number one cause of grain entrapments is the grain going bad (out-of-condition grain), forcing the farmer/worker to go into the bin to remove any blockage and empty the bin. By the same thread, the most effective prevention method is preventing the grain from going bad. This can be accomplished by properly drying grain, maintaining the grain bins, and constant monitoring of the grain (temperature, moisture content sensors, etc).

What

This is where preparation becomes crucial, because even with all the preventative methods implemented above, grain can still go out-of-condition. It is important to study your grain bin and evaluate strategies that you can use to empty out the bin without entering the bin. Many of these strategies involve prepping the bin while still empty. The goal is to develop a strategy where you can address out-of-condition grain without going inside the bin. Training trainings programs and local extension can help you plan how to handle out-of-condition grain.

References

Cheng, Y.-H., Nour, M., Field, W. E., Ambrose, K., & Sheldon, E. (2021). 2020 summary of U.S. agricultural confined space-related injuries and fatalities. Agricultural Confined SpacesInjury/Fatality Summary Report. https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/grainsafety/pdf/2020_ Confined_Space_Summary.pdf

Cheng, Y.-H., Nour, M., Field, W. E., Ambrose, K., & Sheldon, E. (2022). 2021 summary of U.S. agricultural confined space-related injuries and fatalities. Agricultural Confined Spaces - Injury/ Fatality Summary Report. Purdue University.

Deep Blue Diving. (2020). How deep can you go when snorkeling? Retrieved April 15, 2020, from Deep Blue Diving: https://www.deepbluediving.org/snorkel-depth/#Going_Underwater_ with_a_Snorkel_Tube

Issa, S. F., Chng, Y. H., & Field, W. E. (2016). Summary of agricultural confined-space related cases: 1964-2013. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health, 22(1), 33-45. https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/27024991

Issa, S. F., Field, W. E., Schwab, C. V., Issa, F., & Nauman, E. A. (2017). Contributing causes of injury or death in grain entrapment, engulfment, and extrication. Journal of Agromedicine, 22(2), 159-169. https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28129077

Issa, S. F., Nour, M. M., & Field, W. E. (2018). Utilization and effectiveness of harnesses and lifelines in grain entrapment incidents: Preliminary analysis. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health, 24(2), 59-72. https://elibrary.asabe.org/abstract.asp?aid=48926

Issa, S., Wassgren, C., Schwab, C., Stroshine, R., & Field, W. (2018b). Estimating passive stress acting on a grain entrapment victim’s chest. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health, 24(3), 113-126.

Roberts, M., & Field, W. (2008). Flowing grain dangers. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University. https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/grainsafety/pdf/classInfo/FlowingGrainDangers.pdf

Linda Anders, MBA, MSN, RN, CSRN, NPD-BC

Pam Askew, BA, RN

When it comes to rural healthcare, it is no shock that there are challenges such as staffing and provider coverage, financial concerns, and keeping staff abreast to ever changing practice to align with current evidence to provide high quality care. One thing that is not mentioned frequently in conversations related to rural healthcare is the vast opportunities that exist to do great things despite being rural. Small healthcare centers in rural communities have the opportunity to be a hub for pilot projects through the implementation of change in a short amount of time, empowerment of staff to drive that change, development of innovative ideas, and even be a catalyst for change within the community itself. “Rural community hospitals situated at the interface between primary, secondary, and community care services, can contribute to enhanced access and integration of service delivery and benefit the health of rural remote populations” (Blattner et al., 2020, p. 39).

Staffing and Provider Coverage

Recruitment and retention of nursing and ancillary staff along with providers can be a challenge as there is less of a draw due to lack of local university opportunities in addition to the lack of urbanization. Due to provider shortages, there can be concerns related to a work/life balance with call coverage for providers. This concern also carries over to nursing as there is less of a staffing pool to pull from when a call-in occurs or there is a staffing shortage for a shift when there is high influx of the patient census.

However, the beauty of rural healthcare lays in the retention of individuals who are invested in the small community. A key component of staffing for rural

communities is developing a culture that people want to be a part of. We know that organizational culture has an impact on healthcare outcomes. A recent systematic review of literature demonstrated that there is a consistent positive association relationship between healthcare culture and performance (Mannion & Davies, 2018).

Financial concerns for rural communities are evident. “In every year since 2011, more hospitals have closed than opened” (Frakt, 2019, p. 2271). Knowing that, hospitals in rural areas can face severe financial challenges to remain profitable as citizens migrate out of rural communities and care shifts from an inpatient focus to an outpatient focus. The concern remains that if rural healthcare dissipates, reduced access to care will increase (Frakt, 2019).

Community support is essential for rural healthcare. Rural healthcare can be successful with community support and connection. This can occur by keeping the key stakeholders informed on philanthropic ventures that are occurring. Rural communities can rally together to support the rural healthcare that is local.

One main struggle for rural healthcare is the concept of keeping staff up to date whether this is the nursing staff, ancillary staff, or providers. Onboarding new providers can be difficult as there may be no established providers to mentor them as they transition into this new role in the rural setting. For nursing, being creative with competency management can lead to better patient outcomes when those low frequency, high risk situations

come up. Utilization of high-fidelity simulation can promote education and competency of clinical skills for staff while keeping them up to date on evidence-based practices.

For leadership, it is essential to keep engaged with other leaders through nursing organizations. The interaction with other leaders and nurses can help stimulate ideas, bring to light best practices, and highlight evidence-based concepts that could be implemented at rural healthcare locations. Networking with others can be truly beneficial to the rural healthcare community.

Rural healthcare comes with a variety of challenges but can also allow staff to work up to the entirety of their licensure and aid in change practices. Financial concerns, keeping staff up to date on evidenced-based practice, and staffing are all concerns but do not need to dictate how rural healthcare function as they are pivotal in providing care to local members of the community. Healthcare that is available locally is vital to small communities, so members of these small communities have care within reach.

References Blattner K., Stokes, T., Rogers-Koroheke, M., Nixon, G., & Dovey, S. M. (2020). Good care close to home: Local health professional perspectives on how a rural hospital can contribute to the healthcare of its community. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 133(1509), 39-46. PMID:32027637 Frakt, A. B. (2019). The rural hospital problem. Journal of the American Medical Association, 321(23), 2271-2272. https:// doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2019.7377

Mannion, R., & Davies, H. (2018). Understanding organizational culture for healthcare quality improvement. The BMJ, 363, k4907. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4907

Sharon Broscious, PhD, RN

Program Director South University RN-BSN Online Program

Reprinted with permission from Virginia Nurses Today, August 2021 issue

As the COVID-19 pandemic winds down, you may be asking yourself questions about your professional future. What’s my next career step? What does my professional future hold for me? The stress of the COVID-19 pandemic may have created these nagging questions for you, and you might be unsure what steps you should take to answer them. The physical, emotional, psychological, and financial impact of the pandemic on nurses has been well documented. A plethora of publications in professional journals and on websites as well as newspaper and television reports have discussed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses. Terms such as burnout, compassion fatigue, moral injury, PTSD, and healthcare worker exhaustion are used to describe the physical and mental effects of COVID-19 on healthcare providers (Chan, 2021; ICN, 2021). In an interview on NPR, the phrase “crushing stress” of the COVID-19 pandemic was used (Fortier, 2020).

Not only did the nursing workload change – increased number of patients per assignment, increased number of shifts, increased length of workday due to insufficient staff – but also other factors compounded the stress on staff. Lack of equipment such as PPE, the unknowns about the disease itself with policies changing almost daily, and perceived lack of support from leadership have also contributed to the COVID effect (ICN, 2021) on nurses. Some facilities attempted to prepare and support staff for the pandemic surges, to varying levels of successful impact. While providing meals to nurses who could not take time for a meal break was helpful, as the pandemic persisted, nurses needed more support from their leadership teams.

The recent COVID-19 report released by the International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2021) describes the exacerbation of burnout and exhaustion of nurses during 2020. National nursing associations reported approximately 80% of their members identified as feeling stressed. In a survey of healthcare workers conducted by Mental Health America (Lagasse, 2020), 93% indicated feeling stressed, and 76% reported feeling burned out with 55% questioning their career focus. Similar results were found in a survey from Brexi (2020) with 84% of responding healthcare workers identifying some burnout and 18% reporting total burnout. In addition, almost half had considered quitting their job, retiring, or changing their career focus. The top five stressors that respondents identified, in order, were “fear of getting COVID-19, long hours/shifts, general state of the world, fear of spreading COVID-19, and family responsibilities/issues” (Berxi, 2020, para 2). Additional stressors identified by Shun (2021) include physical, emotional and moral distress related to ethical issues faced by nurses such as dealing with patient deaths, scarce resources, and forced changes in practice.

The 2021 Frontline Nurse Mental Health and Well Being Survey (Trusted Health, 2021) revealed for nurses under age 40, 22% indicated they were less committed to nursing. Ninety-five percent of the nurses responding indicated their physical and mental health were not a priority in their workplace or the support received from leadership was inadequate. Finally, 66% of respondents indicated they were experiencing depression and a decline in their physical health. A poll by the Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation (2021) indicated 62% of healthcare workers felt mentally stressed from the pandemic with their greatest fears of them getting infected, infecting their families, or other patients. Another challenge identified was working while wearing PPE (Kirzinger et al., 2021).

Prior to the pandemic, Shah, et al. (2021) reported burnout was the third leading cause of nurses leaving their jobs. However, the pandemic intensified levels of stress and burnout. From the perspective of Maslow’s hierarchy, Virkstis (2021) described the need for leadership to focus on basic needs of staff, not high level self-actualization. The basic needs were identified as: a safe working environment, clear mission, time to reflect on what was happening, and time to connect with peers. Considering the factors identified here, it is no surprise that you may be asking what is the next step for you in handling stress, burnout, and career questions.

Step 1 – Do I stay where I am?

You may be asking the following: Do I leave my job as other nurses have? Do I want to, or can I continue working where I am? Do I just need some time off?