A COLLABORATIVE STUDENT MAGAzINE ON GERMAN SOCIETY

EDITORS

HArry NELLIS

OLIVER LAWRIE

DESIGN

HOWE-YEE LAW

@HAL_ DESIGNS

EDITORS

HArry NELLIS

OLIVER LAWRIE

DESIGN

HOWE-YEE LAW

@HAL_ DESIGNS

04 06 09 13 16 19 23 26 Forgetting the Past: Is AntiSemitism on the Rise in Germany? Angela Merkel: A Pioneer for Political Equality Collective War Guilt Shaping German Identity 75 years on Does a sense of Gemeinschaft live on among former East Germans?

Hallo allerseits,

Herzlich Willkommen to the 5th edition of Politik:Perspektive! It’s so great to have you here and we really hope you enjoy reading through; we certainly did.

We’d like to start by congratulating all of our writers for their fantastic work on some very pertinent topics in the German-speaking space, despite all the challenges that the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is presenting.

Germany’s HS2: A Confirmation of Outdated Climate Policy? Representative Democracy in Germany and Beyond: An Imagined Ideal

COVID-19 in Germany: a Success Story Turned Nightmare Back To School For The UK: A Perspective OF a British Council Language Assistant in Mannheim

In this edition, you’ll read discussions, analyses and critiques on a diverse range of issues, spanning from the alarming rise of antisemitism in Germany, through to an assessment of Angela Merkel’s role in engineering equality in the liberal democratic political arena. Understandably, the response of politicians to the pandemic has been scrutinised, whilst we are also delighted to include a piece on the experiences of a student currently on their year abroad in Germany.

We’ve both been so impressed with the quality of the work submitted, something we hope you too will find after reading this. One day, you may even be reading this as a physical copy (within 2 metres of another person) outside of your household. Crazy to imagine, we know. That’ll be the day - let’s just hope it comes around sooner rather than later.

Viel Spaß und Liebe Grüße Oliver und Harry

German history will be forever associated with antisemitism. Today, Germany commits itself to values of self-expression, freedom and justice, but the wounds of the past remain. In response to this, Germans of all generations are expected to live, work and behave in accordance with the Kollektivschuld (collective guilt) attributed to their country’s role in the persecution of Jewish people. The term is very much anchored in German national consciousness, with the aim to prevent the country from repeating its past mistakes.

But what happens when these feelings of guilt begin to subside? What becomes of Germany when parts of the population’s commitment to combating antisemitism becomes lukewarm and half-hearted? Unfortunately, the answers to these questions need no longer be imagined; this transition is already taking place. Exacerbated in particular by the global pandemic, it is clear that antisemitism and associated prejudices are becoming ever more visible and emboldened in modern Germany. The growing prevalence of antisemitism in Germany is not a recent phenomenon. The country is experiencing a major rise in the number of criminal offences committed against Jews and Jewish institutions. In 2019 alone, there were 2,032 antisemitic attacks in Germany, a 13% increase on the year before.

October 9 2019: radicalised gunman Stephan B. failed to enter a Jewish synagogue in the East German city of Halle, instead killing two bystanders on the street. The synagogue’s highmeasure security precautions, specifically a locked door that kept the perpetrator out, saved the lives of many Jews worshipping in the synagogue that day. Similar scenes can be seen across the

country, where police officers and other highlevel authorities guard the gates and entrances of Jewish schools, synagogues and day care centres. Fast forward to October 2020: A man dressed in military fatigues attacks a Jewish man outside a synagogue in Hamburg.

Even more fearful for the Jewish community living in Germany is the knowledge that antisemitism is rife within state-run institutions such as the police force. In early June 2020, a police officer in Halle was disciplined after failing to document the existence of a paper swastika outside the city’s Jewish community office. Incidents such as these have of course worsened relations between the Jewish community and state powers. One of the reasons for this increased antisemitism is clear: complacency. Complacency seen here from the government and police shows that the issue of antisemitism has, intentionally or not, fallen by the wayside in terms of relevance. The German state is either failing to pay attention to the growth of antisemitism or choosing not to tackle it.

The global pandemic has been a defining moment in Germany’s handling of antisemitism, with analysts having identified a correlation between demonstrations against COVID-19 measures and a rise in antisemitic behaviour. In many ways, this correlation isn’t surprising; antisemitism often peaks during volatile times of crisis, seen, for example, during the plague in the Middle Ages or the Spanish flu in the early 1900s. Protesters against the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic have even gone so far as to compare themselves to Holocaust victims, wearing yellow Stars of David and replacing the label Jude (Jew) with Ungeimpft (unvaccinated). One woman even compared herself

to the famous Nazi resistance fighter, Sophie Scholl. Heiko Maas, German Foreign Minister, responded via Twitter, asserting the following:

“ Anyone who compares themselves to Sophie Scholl or Anne Frank today mocks the courage it took to take a stand against the Nazis. This downplays the Holocaust and shows an intolerable disavowal of history „ HeIKO MAAS

Maas’ words reveal some hope amidst a rather bleak landscape, but what are words if they are not followed by decisive and effective action?

It could even be argued that this statement is somewhat hypocritical given the actions of the German government. Angela Merkel, on the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Central Council of Jews, acknowledged that many Jewish people do not feel safe in Germany, and that antisemitism ‘never disappeared’. Yet, her claim that the German government has taken meaningful steps in

combating antisemitism, such as the establishment of a new cabinet committee, is suggestive of a national leader who is somewhat complacent, failing to acknowledge the strength of the actions required to combat the issues at hand.

Felix Klein, government commissioner on antisemitism, advised Jews to stop wearing their Kippahs in public. There is something gravely wrong, if not unconstitutional, if the person responsible for the protection of Jewish communities in Germany achieves this by imploring the affected communities to suppress their identity.

So, where does Germany go from here? Complacency and passivity are issues that must be overcome if it wishes to reaffirm its moral responsibility to the Jewish community. A committee here or a law there will not achieve anything meaningful if the fundamental attitudes within society do not change. Germany needs to keep its history in the forefront of its mind: after all, only in forgetting the past are we condemned to repeat it. This process of forgetting appears to be beginning, but people in Germany still have the power to stop the nation. Let’s hope they do.

KatIe McCarthy UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS

As Angela Merkel’s historic and influential career as a politician draws to a close, it is important to recognise that she has done far more than just take the helm of a ship that has had to navigate some troubled waters. Through her work, and the reputation that she has developed on the world stage, Merkel has legitimised the position of women taking influential roles in politics and, in doing so, has nullified the relevance of gender in determining one’s ability to lead a country effectively. Ultimately, this has contributed to the diversification of political spheres across the world.

This has, however, not happened by chance. Ranked fourth on the list of the most powerful countries worldwide, Merkel’s impact on Germany can be seen as an illustration of successful leadership in practice. In charge of her fourth consecutive term, her legacy and style of leadership as chancellor of the Federal Republic will surely go on to resemble, if not surpass, the likes of Konrad Adenauer and Helmut Kohl – two of the most powerful political figures in modern German history. Leading the development of the European project, Merkel has positioned Germany as the foremost country on the European continent, in both an economic and political context. Drawing on how she guided the EU out of the financial crisis in 2008, how she led the response to the socalled migrant ‘crisis’ of 2015, as well as how she has dealt with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, she is not only further strengthening her reputation as an effective and decisive leader, but she is also consolidating the success with which women can, and do, lead countries.

Taking her lead, with 15 consecutive years on the world stage, it is perhaps not surprising that we have seen other female leaders not only feel empowered to move into politics, but thrive with their new-found responsibility. Comparing the countries which are perceived to have responded most effectively to the pandemic, women at the forefront of liberal democracies consistently take all the spoils. Just as with Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, only the third female prime minister of New Zealand since 1856, has implemented a combination of strict border closures and policies of financial solidarity during the first wave of the virus. The largely effective response to the pandemic seen in these female-led countries, as well as the small economic impact compared to

other countries such as the UK, must be credited to the policy of the governments in question. However, just as you would not attribute the catastrophic death rate in the United States solely to Donald Trump being a man, the success of the women in charge is not defined wholly because of their gender - it is the substance and policy they introduce and how they deliver and communicate that policy that matters.

Merkel’s impact on Germany can be seen as an illustration of successful leadership in practice.

With Merkel as chancellor, is it any coincidence that participation of females in policy-making processes has also increased significantly over the last 10 years? There are many examples of successful women and their innovative ways of overcoming prejudice in the sphere of politics, allowing them to better the systems in which they exist. Angela Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, Dilma Rousseff, Ursula von der Leyen, Nancy Pelosi, Kamala Harris, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – these are but a few of the names that will pop up on your browser when you search for the most significant female figures in the political world over the last two years. The democratic socialist Alexandria Cortez, the youngest congresswoman in the history of the United States, publicly condemned Trumpism and relentlessly pushed the Green New Deal agenda despite intense criticism from governmental institutions. The wave of criticism that followed highlights the fact that there is a long way to go until society starts evaluating women’s key role in politics in the way they deserve. It is clear that each one of these aforementioned women has left their own prominent mark on their sociopolitical sphere, giving us more reasons than ever before to question the extent of their inclusion in their own corresponding liberal democracies.

This continued progress is, of course, welcome. Political scientists, such as Daphne Van der Pas, have addressed the issue by arguing that political

communication is one of the most significant determiners of how a population votes nowadays. Stereotypes are still taken into consideration in the political sphere and the media focuses primarily on the characteristics of a female politician, their background, physical appearance, and their family life. Therefore, it is more important than ever that individuals like Angela Merkel overcome these biases and that those who follow continue to do so.

Whilst her work as chancellor has often provided a platform for a more representative politics, this is not to say that there have not been mistakes, some graver than Merkel’s international reputation might reflect. The German chancellor has arguably deepened economic difficulties in Eastern and Southern Europe, take Greece and its growing unemployment rate as an example – unprofitable tax increases and credit rates destabilised the country’s economy. Equally, Merkel’s decision to continue with billions of euros of arms sales to countries with a track record of contravening the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights drew intense scrutiny. Such flaws are seemingly inevitable when faced with the complex challenges of modern politics - that is not to say that Merkel should not be held accountable. What is clear is that, once again, the gender of those in power does not directly correlate to the mistakes that may be caused.

Being on the right path to a more open-minded world, one filled with policymakers who are dedicated to enacting their agenda without prejudices, will take time. That being said, with the likes of Angela Merkel and Jacinda Ardern proving that gender equality is necessary, progress is now being made to fight the inequalities within the political world. There will always be division in politics, but the sooner we get rid of the gender bias, the sooner the best talent will rise to the top, and the sooner we can find the most effective solutions to the most pressing issues of our time.

Lia Stancheva UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS

there is a long way to go until society starts evaluating women’s key role in politics in the way they deserve.

75 years on

I would like to say the following very clearly…

We as Germans are responsible for what happened during the Holocaust, the Shoah, under National Socialism

- Angela Merkel, German Chancellor, 2018

November 20th 2020 marked the 75th Anniversary of the start of the Nuremberg trials. Germany has experienced many historically defining moments in the last 75 years, the fall of the Berlin Wall to name one, but the legacy of the Second World War lives on despite so few being able to remember it first-hand. For some, the preservation of memory and a lasting guilt for the war has become more important than ever. To others, notably for Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the shackles of the past are a hinderance to progress in a thriving Germany. The name given to this phenomenon is ‘Historikerstreit’, surfacing in the 1980s, a debate which is centred around how German society should deal with the lasting memory of Nazism and the Holocaust. The persistence of this debate, and the vehemence of both sides, has ensured that German collective guilt has remained relevant, and continued to play a role in shaping the political direction of modern Germany.

Notably, even international satirical programmes recognise the influence of this debate. Yes Minister, a British political television comedy from the 1980s, made it very obvious what the role of this war guilt was in directing political decisions. One of the characters, Sir Humphrey Appleby, Permanent Secretary to a Minister, suggested that the (selfish)

motivation for German entry into the EU was ‘to cleanse themselves of genocide and apply for readmission to the human race’. Although a crass joke in a fictional television programme, the sentiment highlights not only the role that guilt plays in forming policy, but also the international awareness of this reality. Although this comes from a fictional script, this sentiment has also been equally noted in the real world. Bernhard Schlink, a renowned German author and philosopher, maintains that ‘the country [Germany] has been able to retreat from itself by hurling itself into the European project’.

This ‘project’ established a political consensus in Germany – one where Germany took ownership of its past, specifically the Holocaust, and marked these war crimes as the worst in human history, never to be repeated, never to be surpassed. In this way, a negative pride seems to have prevailed in the very cultural fabric of Germany, with glorification of war largely absent. Ongoing recognition of this self-determined guilt produces outwardly tolerant policies from legislators, for example towards refugees. However, this goes well beyond just intricate policy decisions; the sentiment is even mimicked in the language. The German word, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, describing one coming to terms with the past, highlights a struggle to respond appropriately to the actions of the past, one which has since endured for 75 years.

noun (m)

A debate which is centred around how German society should deal with the lasting memory of Nazism and the Holocaust.

When considering German identity politics, collective guilt also has a significant influence on tolerance towards internationalist and nationalist rhetoric. German Federal presidents refer to ‘people in Germany’ rather than ‘the German people’, because the term Volk (people/Nation), a word used in other countries to stoke nationalistic pride,

is still primarily associated with the Nazi Party. Schlink has even claimed that this consensus has created a ‘burden of nationality’, accounting for the lack of nationalistic rhetoric in mainstream postwar German politics.

A notable representation of this burden is seen in backlash against nationalistic comments which understate the war crimes committed. An example of this was in 2017, when Björn Höcke the leader of the far-right faction within the already far-right AfD, claimed that the Holocaust memorial was a ‘monument of shame’ and that ‘German history is handled as rotten and made to look ridiculous’. Political figures in Germany openly condemned this rhetoric. The German Vice Chancellor at the time, Sigmar Gabriel, condemned Höcke, asserting that we ‘must not allow the demagogy… to go unchallenged’ – signifying an averseness to forget the past and break from this consensual consciousness of collective war guilt. Others, such as Jürgen Kasek, the Chairman of the Green Party for the State of Saxony, and Ralf Stegner, the Social Democrat Deputy Leader, accused Höcke of inciting hate speech and of violating antiincitement laws. There was even some backlash amongst less extreme sections of the party, notably by Frauke Petry, Chair of the AfD at the time. This almost fearful condemnation of anyone understating war guilt highlights the extent of its influence, while the very fact that Höcke chose to focus on rejecting this history portrays the potency it still holds in political circles.

Ironically, this rejection of nationalism, of labelling this kind of rhetoric as ‘Holocaust denying’ or ‘fascism’, has driven its political saliency. Mainstream parties in Germany have long eschewed charisma-driven politics and have avoided shows of overt nationalism, leaving an opening for a new type of politics, one which allows Germans to feel nationalistic without fearing retribution. The AfD has created an outlet for positive pride – a way to validate their right to live in a country that is heralded as Europe’s centrepiece for liberal democracy. It would seem, therefore, that arguments that the AfD, the party of nationalism, is starting to negate the influence of collective war guilt, hold some weight.

On the one hand, with AfD rhetoric directed at removing the narrative surrounding German

history, the growing electoral popularity of the party indicates that guilt politics is losing its traction in modern-day Germany. That being said, the growth of nationalism is further motivating those who adhere to the political consensus, rendering it politically salient for those with political power to hold tightly to it. It means that for as long as the political establishment propagates this war guilt consensus, there will continue to be a mainstream counter to overt German nationalism, and the influence of war guilt will remain.

With this being the case, at what point does collective war guilt stop shaping German identity?

noun (f)

Singular: Fault, Guilt, Blame, Responsibility.

Schulden (plural): debt (financial.)

As is the way in politics, there is, of course, no definitive answer. Karl Jaspers, a political philosopher, argued shortly after the war that ‘the consciousness of national disgrace is inescapable for every German’. What is to say that this consciousness is not now a fundamental aspect of German identity? Today, all of those who were alive in the war have retired, yet those with no direct experience of the war still accept collective guilt into their identity and attitudes. There is no telling how successful the right of the German political establishment will be in realigning the national narrative, but for now, the status quo holds.

With Holocaust education, emotional remembrance, and physical reminders ever present, Vergangenheitsbewältigung is something that Germany must do for itself. With the word Schuld meaning both ‘guilt’ and ‘debt’, the language itself hints that this collective war guilt will be continually present until they have, in a sense, paid off a debt that they have assigned to themselves since the end of the war. How long will it take to pay off this debt? That’s anyone’s guess. At what

point did Britain’s politics stop being dictated by guilt for colonial crimes? At what point did the Italians stop governing themselves based on the atrocities committed by Mussolini’s reign? It appears that they themselves decided what this history meant for them, and subsequently, chose when they stopped it influencing them.

In 2018, Angela Merkel used the word ‘we’ to describe responsibility under the National Socialists – this doesn’t seem like a country, at least in the political sphere, that is willing to give up its collective guilt any time soon. Whether this war guilt should no longer be felt in Germany is a very different discussion but, what seems to be clear is that until a shift in political attitudes towards Germany’s own history happens, this collective war guilt will not stop shaping the identity and, therefore, policy, of the de-facto leaders of Europe.

13 Does a sense of Gemeinschaft live on amongst former East Germans?

social relations between individuals, based on close personal and family ties; community.

The Mauerfall (The fall of the Berlin Wall) on the 9th November 1989 was a historic domino that instigated the toppling of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Soviet Union and ultimately the end of the Cold War. This had been a day that many, either side of the wall, had been hoping and vying for. To East Germans in particular this was a distinctly monumental day, as it was the catalyst for the disintegration of everything they had previously known, primarily the Marxist-Leninist ideology enforced by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) and the Kremlin. However, 31 years on since Germany’s reunification, do former residents of GDR still feel a sense of Gemeinschaft (community) when reminiscing about their former nation?

It is fair to say that many former East Germans still recall happy memories of the GDR, which account for a significant period of their lives. The clearest illustration of this would be within the media movement of Ostalgie, whose name even derives from the words Nostalgie (nostalgia) and Ost (east). Ostalgie is the answer to the call of numerous former East Germans, who wished for the GDR to be depicted in a more positive light that was in line with their own personal recollections. The most famous example of this is probably Wolfgang Becker’s award-winning film Good Bye, Lenin! (2003). Although this movement portrays the GDR more favourably and in accordance with the recollections of former East Germans, it does not necessarily mean that Gemeinschaft is present within this demographic today, which had once been such a pivotal element of their society and way of life. This is due to the implantation of Soviet Union’s own set vision of Gemeinschaft by the SED, arguably a cornerstone of its communist rule, of which consisted a proletarian population working together under the harmony of socialism. Alex, the protagonist of Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye, Lenin!, is a prime example of the large proportion of former East Germans still alive to remember the realities of this first-hand, and now find themselves at the standpoint to look back at the GDR.

This generation of Alexs’ were born and grew up entirely within the GDR, unlike the generation prior, of which the majority have most likely passed away,

having never known life in a unified Germany. It would be easy to assume that this cohort would have been whole heartly invested in their nation’s fixed socioeconomic construct of Gemeinschaft, and yet they were in fact the ones who protested against this status quo, as Alex does in Good Bye, Lenin!, thus contributing to the eventual fall of the Berlin Wall. Nonetheless, just because they may have demonstrated against the state is not to say that there was no sense of Gemeinschaft between them, it is probable that it was just not in the form being inflicted by the governance of the SED. As during the Montagsdemonstrationen (Monday demonstrations), where many marched together in protest against the regime of the GDR, could it not be argued that there was a sense of Gemeinschaft in rebellion?

Many from this age bracket developed an outward conformist façade and an inward revolt over time. This attitude is also displayed by Alex as like many his age, behind closed doors he seemingly opposed the policies being forced upon him. The former German politician and Bonn’s first Permanent Representative in the GDR, Gunter Gaus, coined this as a “Nischengesellschaft” (niche society). Herr Gaus himself describes the notion as follows:

“the preferred space in which people there leave everything – politicians, planners, propagandists, the collective, the grand objective, the cultural heritage – behind . . . and spend time with family and friends watering the flowers, washing the car, playing cards, talking, celebrating special occasions. And thinking about how, and with whose help, they can secure and organize what’s needed, so that the niche becomes even more liveable.”

just because they may have demonstrated against the state, is not to say that there was no sense of Gemeinschaft

WAS TAKEN

Does this not imply that Gemeinschaft can also exist in a private space too, or must it have to be something levied by the state? In the book “Re-Imaging the Niche: Visual Reconstructions of Private Spaces in the GDR” by Gabriele Mueller the author states:

“Gaus (1983) describes the niche as an apolitical private sphere into which East Germans retreated in order to withdraw from a system that they opposed and from its public institutions and spaces. Thus, the niche allows the pursuit of individual interests beyond the reach of state control.”

These last few words underline how this was something that the framework of which had been completely constructed by the people, and which the SED had no control over. Yet it was a sentiment that the SED and the Kremlin themselves had inadvertently evoked over the course of 40 years, given that the Gemeinschaft imposed by their communist governance was not in line with what the people desired. Through this there is a clear change of hands as to where Gemeinschaft lies.

As simplified as it may sound, many would agree that some of the strongest friendships are established on a mutual hatred or disliking of something. Similarly, this is conceivably the kind of unity and Gemeinschaft the people of east Germany were experiencing in their “Nischengesellschaft.” For example, it was thanks to Alex’s non-conformist stance in Good Bye, Lenin! that he and his girlfriend are brought together.

That being said, how the Gemeinschaft of this “Nischengesellschaft” manifested itself among the Leipzig Montagsdemonstrationen is still to be answered. The most obvious explanation of the development of Gemeinschaft in this capacity is simply

as a result of an eventual loss of patience of the people living under the constrains of a “Nischengesellschaft,” which had previously been the only social construct in which they could express their discrepancies with the State. This finally provoked them to protest for their freedom, illustrated by Alex’s revolutionary actions in Good Bye, Lenin!. The Montagsdemonstrationen started in Leipzig and spread across many major cities in East Germany, with the participation of well over 700,000 people between September 1989 to April 1991. It could be claimed that it was during these protests that Gemeinschaft was taken away from the State and became something which was truly owned by society itself.

Therefore, it is apparent that the unity in rebellion experienced by these protesters fighting for a common cause epitomises the essence of the Gemeinschaft felt by former East Germans today when looking back at the GDR, rather than that which the Soviet Union had intended. Furthermore, it could be reasoned that the motivations and unity felt in any joint activism, right to the present day, closely reflect the play out of the Montagsdemonstrationen, whether this be in the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests or in the 2021 storm of the US Capitol.

TOBY SHAY UNIVERSITY OF HULL

In the central county of Hessen lies the 1000-hectare Dannenröder Forest. For over a year, activists have occupied parts of the Dannenröder in opposition to the construction of the A49, a proposed Autobahn that would result in up to 200 hectares of the forest being cleared. In December 2020, the activist occupation was ended by the police. However, in their efforts to end the protests, the police inadvertently stoked the associated sentiment further. So much so that a new occupation has begun with the motto Danni lebt (The Forest Lives). Despite the relevance of these events to the ongoing politics around the climate crisis, there has been a considerable lack of analysis of this event from established media sources. This article aims to put that right, with an analysis of the A49 project as a whole, whilst also assessing the compliance of the Green Party with the project and what the potential damage for its reputation as the Ökopartei (eco-party) may be. In the context of the Dannenröder Forest, I will also question the direction of liberal democratic politics in Germany, asking to what extent the narrative of ‘greenness’ is used as a veil to avoid scrutiny whilst pursuing environmentally exploitative policies.

The A49 project was introduced as a project in the early 1970s, when, even 50 years ago, unseen costs and resistance from local communities halted construction plans. This resistance has only increased since, yet the project has never been abandoned by politicians and investors. As the project received legal approval from the Federal Administrative Court in June 2020, the green light was given for construction, and therefore the clearing of the forest, to begin. In a time where the devastating impacts of climate exploitation can already be seen across the world, it is important to question exactly why this new Autobahn is actually being built in this manner.

Given Germany’s commitment to the Verkehrs- and Energiewende (the idea of a transition towards implementing environmentally friendly transport and energy policy in Germany), how does this project do

anything other than undermine this very governmental policy? Before answering this question, it is important to consider the political context in which the project was approved. Since 2013 the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Green Party coalition has been in power in Hesse, with the Greens increasing their share of the vote by 8.7% in 2018. In the coalition contract that was later published, the following pledge was committed:

‘Dementsprechend wollen wir insbesondere weiter daran arbeiten, die verschiedenen Verkehrsmittel miteinander zu verknüpfen und unnötigen Verkehr zu vermeiden. Wir wollen gezielt das Klima schützen und die Lebensqualität noch weiter erhöhen.’

Translated, the Green Party and CDU politicians pledged in writing that they would continue to link different forms of transport whilst working to reduce unnecessary road traffic, as well as vowing to protect the climate with targeted measures and to further improve the quality of life of those they represent. With this in mind, it is important to refer to the aims of the project, with hopes to reduce traffic jams, shorten the length of journey times and cut noise pollution in the areas that are currently congested by motorists. This all seems fairly compatible with the CDU/Green statement, yet behind the headlines there lies a number of more serious and climate-damaging consequences to the project, which mean that the construction is simply not consistent with the CDU/Green statement. Indeed, the concrete actions taken by politicians seem to suggest they are saying one thing, and implementing exactly the opposite. It is about time that similar attempts to veil climate-damaging projects with halfhearted pledges to protect the environment are

criticised for what they are: political gamesmanship. The approval of a motorway construction that will destroy hectares of forest for a short reduction in journey time certainly seems to contradict any professed efforts to ‘protect the climate’, with promised replacement trees not set to have much impact for decades in comparison to leaving the existing ones. The project even goes against any aims to ‘avoid unnecessary congestion’, as originally claimed by the government. Ronald Milam’s work on transport planning can be used as a framework to highlight that when more road is built, more cars will use the road network in total, rather than those currently on the road dispersing across the old and new roads, a theory called induced demand. This study is particularly useful as it analyses the results of numerous studies, concluding that induced demand is a real, yet conveniently ignored phenomenon in transport policy praxis. Milam describes short term responses to road construction such as ‘new vehicle trips that would otherwise not be made’ as well as ‘longer vehicle trips to more distant destinations’ that come as a result of new road space being added. In the long-term, there can also be ‘changes in land use development patterns’ and ‘changes in overall growth’. Perhaps those building the A49 did it in good faith, but it is clear that a different course of action is needed if they are indeed intent on honouring their manifesto pledge.

As the construction was approved in the coalition contract, the same Green Party that once claimed to ‘conserve our nature’ became compliant in the building of a new motorway, not only at the expense of parts of a 250-year old woodland, but also the habitat of multiple protected species and the nearby water source which supplies a part of Frankfurt am Main. Along the proposed route, 85 hectares of trees are set to be cleared, 27 of which lie in the Dannenröder Forest. Such an anti-ecological project would hardly be a shock coming from the CDU, but the Green Party’s involvement will have no doubt tarnished their reputation as the leading party for the environment.

This is something that the party’s leadership has noticed, with the leadership positioning themselves against the project. In comparison, the Hessian Greens voted for the Autobahn’s completion, later claiming that they had ‘no influence on the construction of the A49’ due to the fact that it is a ‘federal motorway’ and had already been passed through the federal courts. On October 1st 2020, the Hessian Green Party even tweeted MP Katy Walther’s statement that climate activists should instead be protesting at the Federal Ministry of Transport in Berlin, a frankly desperate attempt to deny the Party’s role in the project. This outright denial of accountability and ambivalence shown is too prevalent within the arena of liberal democratic politics, where a radical re-imagination of a new world is too often stifled by the need to follow the preservation and creation of capital. This ultimately results in parties that claim to be (and often initially are) pro-ecological becoming guardians of the statusquo, as long as this serves their purposes of being reelected.

In the void left by a lack of climate-sensitive, ecological and social action on the mainstream political stage, members of grassroots movements themselves have stepped in to defend and promote ecological values in the German-speaking space. Barrios, tree houses and other structures were set up in the areas of the forest that were due to be cleared, with individual people playing their parts in a bigger network of resistance and re-imagination of the current system. The original occupations and protests in the Dannenröder Forest galvanised people across the German-speaking space to protest in solidarity, with naked activists occupying the German embassy in Vienna and demonstrations taking place in Munich.

Very similar to the ongoing situation with HS2 in the United Kingdom, the A49 is just one example which highlights a series of key issues: large parts of current climate policy in Germany and beyond are outdated, failing and, perhaps most importantly, not

radical enough to enact the level of change necessary to prevent the impending climate crisis. Protests have brought attention to the importance of the transformation of transportation, with alternatives to the A49 recommending the restoration and development of existing transport networks, most notably rail, cycle and bus routes. Yet all of these proposals have been ignored and the demonstrations which have countered the project have been met with a brutal police presence.

Whether the tree-felling will continue, or how the next few months will play out, remains unclear. Yet one thing cannot be denied: it is time for a radical restructuring of transportation networks and climate policy in the German-speaking space, for the system at present is not fit for purpose.

HARRY NELLIS UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS

Members of grassroots movements themselves have stepped in to defend and promote ecological values in the German-speaking space.

Ah, yes. Representative democracy. Equivalent to receiving two all access VIP tickets to the (insert your favourite sport here) World Championship Final, or finding that coveted golden ticket granting you access to Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. Or, at least, so goes the narrative in Western Europe.

One of only 19 full democracies in the modern world (as defined in the Democracy Index), Germany assumes the role of one of the most influential representative democracies on the world stage. A phoenix rising from the ashes of authoritarian rule, Germany now acts a bastion for the inclusive, democratic system of governance. Not only does Germany actively ensure the preservation of their domestic democracy, for example installing Centres for Democracy throughout the country, but it also actively imposes their democratic ideal, and its conjoined narrative, on its international partners. They are the powerhouse of an international organisation whose raison d’être is to promote, with initiatives such as ‘The European Democracy Action Plan’ aiming to ‘build more resilient democracies across the European Union (EU)’ through ‘promoting free and fair elections’ and ‘countering disinformation’.

And who can blame them?

The constituent parts of a liberal democracy are, on the face of it, beguiling. A system where egalitarianism thrives would be the envy of the world over; one with universal suffrage, freedom of expression, separation of power, and true accountability of those in power. Indeed, such characteristics are quoted by those who fervently defend democracy as the ideal system of government, with the German government included.

It seems, however, the reality is that these attributes are about as beguiling as they are utopian. Representative democracy, in its current state, empowers neither Germany, nor the EU, to overcome the issues faced in the modern world.

‘Theory states that a liberal society enables all interests […] to contribute to the political process. [In] Germany’s political and legal system […] in many ways, it remains a pretence’. So reads a report by Transparency International on German

Democracy from 2014, which begins to contextualise the impotence of (German) representative democracy in affecting the necessary change required to overcome both the number, and the magnitude, of the issues we are facing.

The flaws in representative democracy, in Germany and beyond, are numerous.

Were the architecture of the Bundestag to represent the conduct within accurately, perhaps its famed transparent dome would be opaque. Although some anti-bribery laws are in place, transparency within German government does not go far enough to meet the standards assigned to a representative democracy. Regulations surrounding lobbying are mostly voluntary, examples of which include political entities having no obligation to submit contacts to the lobbying register, or to disclose donations under €10,000. This is, however, not just an isolated issue with German democracy. €251 million, as reported by the Corporate Europe Observatory, was received by EU institutions from oil and gas firms between 2010 and 2019. Is it a coincidence that the necessary change in the oil industry has not (yet) been introduced by those in power? A system where capital has a greater influence on policy than the votes of the electorate creates an environment in which the sacrosanct power of the entire electorate to control the actions of their legislators has been eroded.

Even if every vote mattered equally, the system would still rely on 100% participation to be truly democratic.

Even if every vote mattered equally, the system would still rely on 100% participation to be truly democratic. 100% participation is, of course, unfeasible, but as things stand, governments are given a mandate to be responsible for every issue a country will face during its time in office without

being required to even have the majority of support of the population. In Germany, Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Unionists (CDU) formed a coalition government with the Social Democrats in 2017 after achieving just over 30% of the popular vote in an election with only 75% of those eligible to vote (which is by no means 75% of the population) actually having voted. The democratic mantra is that every vote matters, yet the current system rests idly as those in power claim a democratic mandate to govern all residents of Germany, however they see fit, assuming the prerogative to enact policy that makes and breaks people’s lives, while ignoring the fact that the majority of the population either opposed the government or did not, or was not allowed to, express an opinion on how the country should be run.

Even democratic tools outside of elections do not function. From petitions and protest through to referenda, democratically elected governments have no legal obligation to act upon the sentiment created by these very tools. Still, these are pointed to by the establishment as ways to hold them accountable for their actions. Just look at how efficacious the Black Lives Matter protests were in forcing legislators around the world to eradicate institutional racism.

All of this analysis assumes, however, that the power of the individual to enact meaningful change within the system existed in the first place. Representative Democracy at present, but even more so theoretically, provides a platform for any and every uninformed, corrupted opinion to influence the most important institution of any country - its government. In Germany and beyond, we are in a position where those with immense power need not demonstrate their competence and, secondly, those in the decision-making processes need no ability to critically assess the options and potential consequences before them. Just as you would not trust a banker to conduct life or death surgery on your nearest and dearest, why would you trust somebody to, just for the sake of argument, have the final say in how a country responds to a deadly, once in a century pandemic? (The success of which, coincidentally, also being a matter of life and death, but on a dangerously large scale.) In the current climate, it is time democracy moved towards a system by which competency is

held in higher regard than popularity, a failure to do so exposing provably awful consequences, as we have seen throughout the world to date.

All of this voluntary change would be political suicide for the mainstream party in power and, therefore, is unthinkable.

As is clear in Germany, a symptom of this reality is that the system is one which fosters populism, one where the priority is to be re-elected, rather than do what is best for the population. To contextualise this, let’s revisit the environmental crisis. An economic analysis is for another article, but an industry-devastating (namely oil), and most probably recession-causing policy, would need to be introduced in Germany to affect the genuine change needed to protect the environment for future generations. The fall out for everyone would be dramatic - a version of which Europe, with just the slightest hint of irony, is experiencing now as a result of the pandemic. All of this voluntary change would be political suicide for the mainstream party in power and, therefore, unthinkable. After the political vultures of opposing parties had scavenged the PR victories from the aftermath of this most extreme change in the lives of the voter base, the government that prioritised long-term security over short-term gratuity would be out of a job at the next election, regardless of how necessary that hardship would prove to be.

In the case of the environment, with failed harvests in Africa, hurricanes displacing citizens in the Americas, through to the bushfires in Australia, ChristianAid estimates that hundreds of billions of dollars of damage were caused this year as a direct result of climate inaction - with the numbers forecast to increase year on year. With a change of system, we stand the best chance of changing these soon to be irreversible problems. Without representative democracy as it is, we would at

If they are truly committed to serving their citizens, reform is desperately needed.

least be able to focus on preventing issues that will be catastrophic in the long-term, rather than eliminating simple inconveniences for small portions of society in the short-term. The populist agenda within a representative democracy could be nullified, were the voter base to be better informed, but once again, a representative democracy cares not for informed voters. Many informed voters are rational in their decision-making process, with an acceptance of the empirical evidence on a subject, but these opinions have the same merit as those who have done the opposite. Although in every other aspect of life we trust those with expertise to dictate our direction, such as scientists advising us which vaccine to use, this is not reflected in our governmental system. So, why has the narrative cemented itself that those with no expertise are the only fair and feasible option for governance?

With all signs pointing towards economic supremacy shifting away from the West within the next few decades, rather than debating, among other things, if extremists should be allowed to abuse minorities under the guise of freedom of expression, the premier economic power of Europe needs to be finding a solution to maintain their and, therefore, the EU’s economic competitiveness moving forward. Equally, as de facto leader of Europe, Germany must enact change at a quicker rate than is presently possible to preserve not only their future, but that of the EU as well. The only

feasible way of which at present is to reform their system of governance.

It is strange how the world works, isn’t it? Here exists a self-defeating paradox: enacting everything for which the EU and a reunified Germany stands, would be facilitated by a reform of their democracy, yet to reform is, according to the narrative, an unthinkable event with many knock-on effects which would ultimately lead to oppression. Working out the exact nature of its replacement would be for another article, written by someone significantly more qualified than myself (perhaps one day I will be in a position to write coherently on that very subject). But for now, one thing is clear. Whatever happens in the coming years, the current model will serve neither Germany, nor the EU, in overcoming the issues they face. If they are truly committed to serving their citizens, reform is desperately needed, and it is needed now. One can dream of a world where rationalism prevails over populism. Where intrinsic discrimination is replaced with thriving egalitarianism. But will this ever become reality? You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.

It is no secret that when the Coronavirus pandemic first struck Europe, Germany’s initial response was seen as one of the most effective by the rest of EuropE

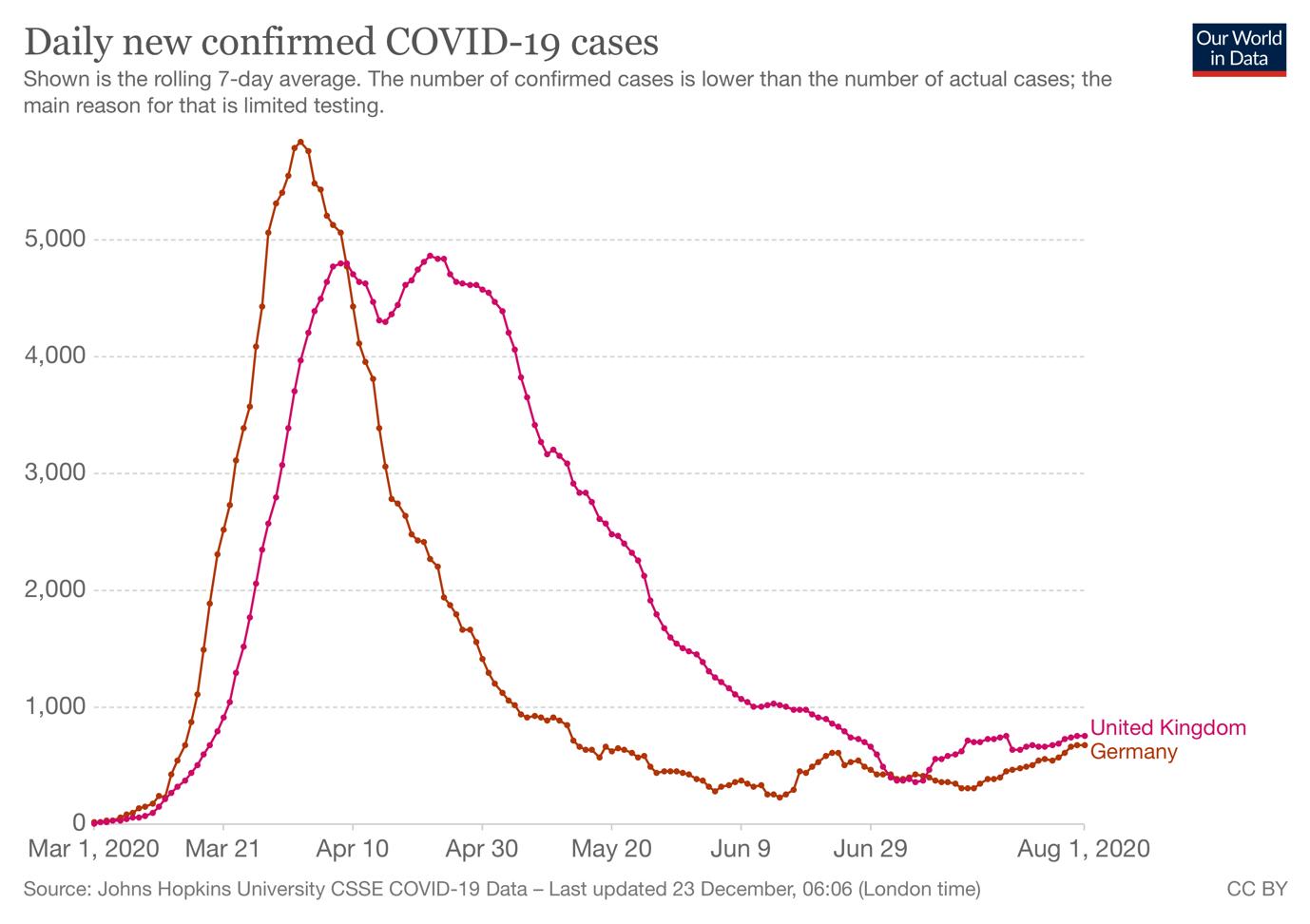

It is no secret that when the Coronavirus pandemic first struck Europe, Germany’s initial response was seen as one of the most effective by the rest of Europe and beyond. Britain’s Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty, was especially impressed, noting that the United Kingdom had a ‘lot to learn’ from their German counterparts with regards to their approach to mass testing in the early stages of the pandemic. As seen in the graph below, the swift response in Germany led to a dramatic fall in case numbers in comparison to the UK and a degree of normality was achieved much sooner than in the UK; non-essential shops reopened in April 2020 in Germany compared to June 2020 in the UK. Fast forward to December 22nd 2020 and Germany recorded five times as many cases at 25,000, and 3 times as many deaths at 944. This begs the question: how did the German government succeed during the first wave and why are they not replicating this success in the second?

Physician and health economist Reinhard Busse, professor at the Technical University of Berlin, emphasised the benefit of Angela Merkel being a

scientist and her chief of staff Helge Braun being a doctor in contributing to the country’s initial response to the pandemic. With those at the top of the decision-making process having scientific backgrounds, trust in, and therefore compliance with, the governmental policy may well have been heightened. The comparatively low number of deaths and high number of cases can be put down to the availability of tests, meaning potential carriers were informed of their infection earlier and therefore were able to isolate quicker, limiting the number of contacts each person would have had. The fewer deaths could also be due to preparedness of the German healthcare system, as shown by the number of intensive care beds that remained vacant during the first outbreak in Germany. 28,000 beds were available at the start of the outbreak, which then rose to 40,000 in the middle of April in case hospital admissions were to increase rapidly.

As we can see, infrastructure was in place to fight the Coronavirus outbreak, but what measures did the government take to restrict social contact between members of the public and how did the measures differ between the first and second outbreak? On April 2nd 2020 Germany reached their peak for the first wave: Around 5,800 cases. By this time, schools had been closed for two and a half weeks in 14 out of the 16 states of Germany and, on March 22nd, the government announced a ban on gatherings of more than two people and the closure of non-essential shops. These simple measures led to ‘intermediate success’, with Merkel repealing these restrictions in mid-April. In comparison, high-street shops did not reopen in the UK until June 15th. Despite this ‘intermediate success’, Merkel recognised that the situation remained fragile and that a second lockdown would be ‘unavoidable’ if

the cases began to rise again. On the face of it, this shows a sound understanding and a readiness to act if the situation were to worsen once again. By October 17, Germany had reached the same number of cases as it did in the first peak (around 5,800). However, it was not until October 28 when the government announced a partial lockdown from November 2nd until the 30th. 10 people from two households could meet. Schools, non-essential shops and hairdressers remained open (restaurants and bars were closed). The partial lockdown stabilised case numbers for a month, only for them to increase once more, prompting a full national lockdown from December 16th with schools closing as well. The dramatic increase in cases has put a significant amount of pressure on the German healthcare system. Gerald Gass (Head of the German Hospital Federation) had some shocking statistics from Saxony, one of the worst affected states in Germany. At the time of writing, there were five times as many people in intensive care than in April and hospitals were either at capacity or already above it.

It is true that Germany are testing far more people than in the first peak but if they have more information on the number of cases then it seems logical that they would be able to make a more effective decision on how to combat the increase in cases. Karl Lauterbach, an SPD MP in the Bundestag and professor of health economics and clinical epidemiology, wrote an article for the Guardian on October 19th stating that ‘it would be impossible to avert a second wave.’ We do not know for sure if this sentiment was shared throughout the Bundestag at the time, but it must be questioned, given all the information they had,

why did government leaders implement a partial lockdown knowing that a full lockdown would be necessary?

If Germany had a tried and tested, successful method for tackling the virus in the first wave, then why not reintroduce the same regulations once the case numbers began to rise to the levels seen in April? There is of course the economic argument, an argument which says that shutting Germany’s economy would cause more damage to people’s livelihoods in the long-term than the virus would do in the short-term. There are also questions around notions of personal freedom, as well as maintaining popularity with voters given the fact that German Federal Elections take place in September of 2021. With non-essential shops and schools staying open, it would always be difficult for the case numbers to decline. This ultimately led to another full lockdown, which, in retrospect, could have been introduced significantly earlier to prevent the added pressure on hospitals and the higher death rates.

it is clear that the

German government’s change of strategy has not worked.

It is of course easy to write about this in hindsight. However, given the statistics from the first and second wave, and the divergence between the two strategies used to counter each one, it is clear that the German government’s change of strategy has not worked. Was this down to a lack of proactiveness? Were they too complacent in the months preceding the second wave? Only they will know that, however, one thing is certain. The balance they tried to strike between managing the economy and public health did not work, and Germany will reel from the consequence of this for years to come.

At the moment, I am on my year abroad in Germany, where I work as a Foreign Language Assistant (FLA) in an Intergrierte Gesamtschule, the German equivalent of a secondary school. My job is to help the children learn English; I mark work and sometimes take lessons myself. Throughout my time at university I have always been interested in education, particularly the policy side of it. Despite my interest in education policy and theory, I’ve been pleasantly surprised with the amount I have enjoyed the hands-on aspects, too. I am a firm believer that good quality education is a right at all levels and one of the fundamental pillars of a happy and productive society.

Over the course of the past few months, I have observed some interesting differences between the British and German education systems, concluding that there are some important lessons that the UK could, and should, learn from Europe’s powerhouse.

My time as a pupil at school was relatively typical in that I went to a state school and we had uniforms. The only major deviation from the ‘norm’ is that I went to an all-girls school. In terms of foreign languages, French and German were offered to us, with some students doing both, while ‘lower-level’ learners only learnt one. This differs from the all-boys school in the same town, where it was not compulsory to take a foreign language at GCSE (the compulsory learning of a modern foreign language at GCSE-level was scrapped in England, Northern Ireland and Wales in 2004). Though I do remember my time with my friends at school fondly, I’m not one of those people that really misses my school days, and I knew I never would be. I always wanted to grow up, move out and go to university. I think this was a symptom of how the majority of our teachers treated us: with not one ounce of respect, which is something I will come back to later. From my experience as a foreign language assistant here in Germany, school seems so far away from how it was when I was there myself. There are two key differences that really stand out to me: the relationship between teacher and student, and how foreign languages are taught here.

Students in state schools do not wear school uniform, nor are teachers obliged to wear formal clothing, all of which means that most people wear casual clothing. This might seem like an unimportant element of school life, but it would appear that this helps to bridge the gap between the notion that the teacher is superior and the student inferior. Little to no dress code means that there is one less thing for which students can be punished, and therefore one less thing to distract the children from their school life. There were countless times we were disciplined for wearing the wrong uniform and shoes, even though the standard uniform was expensive, with a lot of families not necessarily being able to afford it. Students come to school in their own clothes, feeling more comfortable and therefore ready to learn.

languages are absolutely vital for the UK. They are key to diplomacy, trade, social mobility and cohesion.

Furthermore, in my first months at my school, it was very rare to see misbehaving pupils either being sent out of the classroom or being shouted at by teachers. This is not to say the students do not misbehave, because they do; the response of the teacher is what differs. At times when students are being disruptive at the back of the classroom whilst they are supposed to be working, the teacher will simply go over and ask them if they understand what they are learning, reminding them of the work they should be doing. This means that the children get on with their work more quickly, rather than wasting time resolving the conflict that would otherwise ensue. In addition to this, they are more likely to respect their teacher, as harsh punishment for developing social skills (which was commonplace at my school) does anything but foster a productive learning

environment. This approach promotes understanding in the student-teacher relationship: the student feels like they can talk, laugh and debate with their teachers, while being met with consideration and kindness. As a teenager, the only thing I wanted to be treated as was some kind of ‚mini-adult’; pupils in Germany are, and it shows.

In terms of learning foreign languages, it was as if I stepped into another world when I observed my first lesson, an 8th grade (13-14) class. The teacher used English for 90% of the lesson, something that my teachers could only manage during my German A-Level. 9th graders (14-15) were writing their CVs in English, which I didn’t learn to do until my second year of studying German at university. As well as this, students were learning about indirect speech, another topic students of German at my school could only touch upon at the end of their A-levels. 10th graders (15-16) were reading and analysing a book, something we could only dream at the same age while learning German. This shocked me and the other teachers alike when I explained that I did these things so late in my German education. I wondered how much better my level of German would be if the same emphasis were present. How many more students would be engaged with learning foreign languages? How many doors might this have opened for the average British student picking up life experiences or moving into the workplace? Language learning is incredibly difficult and after 9 years I am still yet to master the method of it. It requires a discipline that a lot of people might not have, but if students were encouraged and taught in more engaging ways from a younger age (or in some cases at all), this could be overcome. Children in German schools are required to start learning English at the age of nine, two years earlier than their peers in British schools. These two years are vital and could make all the difference in terms of the level and interest in modern foreign languages as a subject.

Up to now, this piece has been based on my personal experiences, both in the UK and in Germany. But do the numbers back me up? Statistically, Is the UK lagging behind?

In short, yes.

According to a report from the Higher Education Policy Institute, only 32% of 16-30-year olds in the UK feel confident reading and writing in another language, in contrast to Germany’s staggering 90% and the EU average of 89%. The report argues that this was a consequence of the removal of the compulsory additional language GCSE requirement in 2004. This has also led to less students studying languages in higher education – between 2010/11 and 2016/17, the number of degree-level students taking German declined by 43%. In the report is this damning sentence, which, in my opinion, sums up the direness of situation well:

‘Languages are taught sporadically at primary level in England; learning beyond age 14 is optional; and university languages departments and centres are vulnerable to cuts and closures.’

Is it indeed any wonder that we are lagging so far behind the rest of Europe?

Now, more than ever, languages are absolutely vital for the UK. They are key to diplomacy, trade, social mobility and cohesion, something that is crucial with the longer-term impacts of Brexit still to be ascertained. Relationships between teachers and students must be improved, not just in language departments across the UK, but within the entire education system. This will make for happier pupils and more productive teachers, creating a better working environment and thus resulting in increased engagement. Above all, however, it is clear that at a time when Britain is isolating itself from its European neighbours, it is those neighbours that could have the solutions to the critical issues we are facing within our education system. Somewhat ironic, don’t you think?

We are always looking for new contributors. If you want to write, or are even considering it, don’t hesitate to reach out to us.