Volume XXXV - Issue II - July., 2025

Volume XXXV - Issue II - July., 2025

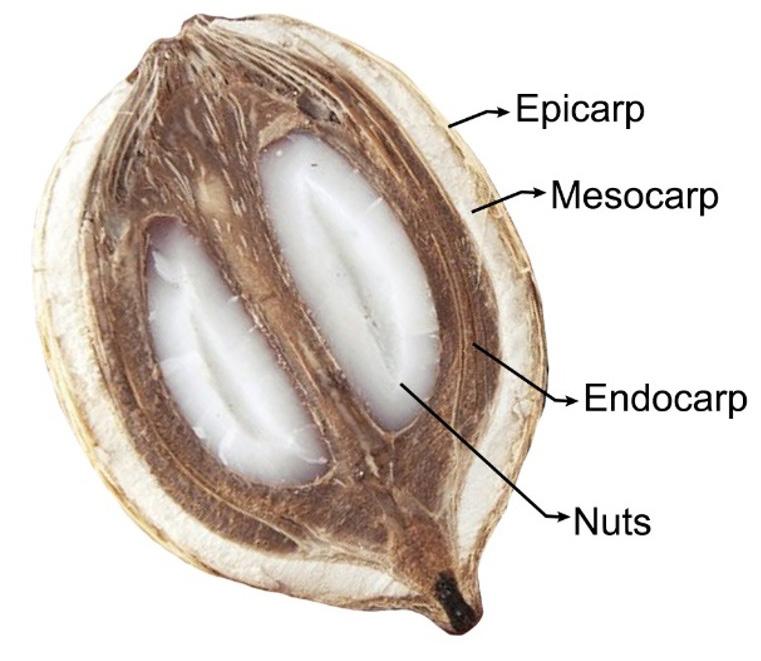

Morphological structure of a babassu fruit. Its mesocarp was evaluated as a green composite with polyethylene.

e d I tor I al C ou NCI l

Antonio Aprigio S. Curvelo (USP/IQSC) - President m ember S

Ailton S. Gomes (UFRJ/IMA), Rio de Janeiro, RJ (in memoriam)

Alain Dufresne (Grenoble INP/Pagora)

Artur José Monteiro Valente (UC/DQ)

Bluma G. Soares (UFRJ/IMA)

César Liberato Petzhold (UFRGS/IQ)

Cristina T. Andrade (UFRJ/IQ)

Edson R. Simielli (Simielli - Soluções em Polímeros)

Edvani Curti Muniz (UEM/DQI)

Elias Hage Jr. (UFSCar/DEMa)

José Alexandrino de Sousa (UFSCar/DEMa)

José António C. Gomes Covas (UMinho/IPC)

José Carlos C. S. Pinto (UFRJ/COPPE)

Júlio Harada (Harada Hajime Machado Consutoria Ltda)

Luiz Antonio Pessan (UFSCar/DEMa)

Luiz Henrique C. Mattoso (EMBRAPA)

Marcelo Silveira Rabello (UFCGU/AEMa)

Marco Aurelio De Paoli (UNICAMP/IQ)

Nikos Hadjikristidis (KAUST/ PSE)

Osvaldo N. Oliveira Jr. (USP/IFSC)

Paula Moldenaers (KU Leuven/CIT)

Raquel S. Mauler (UFRGS/IQ)

Regina Célia R. Nunes (UFRJ/IMA)

Richard G. Weiss Washington (GU/DeptChemistry) (in memoriam)

Roberto Pantani, (UNISA/DIIn)

Rodrigo Lambert Oréfice (UFMG/DEMET)

Sebastião V. Canevarolo Jr. (UFSCar/DEMa)

Silvio Manrich (UFSCar/DEMa)

Financial support:

Available online at: www.scielo.br

e d I tor I al C omm I ttee

Sebastião V. Canevarolo Jr. – Editor-in-Chief

a SS o CI ate e d I tor S

Alain Dufresne

Artur José Monteiro Valente

Bluma G. Soares

César Liberato Petzhold

José António C. Gomes Covas

José Carlos C. S. Pinto

Marcelo Silveira Rabello

Paula Moldenaers

Richard G. Weiss (in memoriam)

Roberto Pantani

Rodrigo Lambert Oréfice

d e S kto P P ubl IS h IN g www.editoracubo.com.br

“Polímeros” is a publication of the Associação Brasileira de Polímeros

São Paulo 994 St. São Carlos, SP, Brazil, 13560-340 Phone: +55 16 3374-3949

emails: abpol@abpol.org.br / revista@abpol.org.br http://www.abpol.org.br

Date of publication: September 2025

Polímeros / Associação Brasileira de Polímeros. vol. 1, nº 1 (1991) -.-

São Carlos: ABPol, 1991-

Quarterly

v. 35, nº 3 (September 2025)

ISSN 0104-1428

ISSN 1678-5169 (electronic version)

1. Polímeros. l. Associação Brasileira de Polímeros.

Website of the “Polímeros”: www.revistapolimeros.org.br

E E E E E E E E E E E E E E

o r I g IN al a rt IC le

Fabrication, characterization and mechanical behaviour of Tamarindus indica fruit fibre-reinforced polymer composites

Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan, Kathiresan Marimuthu, Prashanth Shanmugam and Moganapriya Chinnasamy e20250025

Quantification of elastomers in CR/NR/BR blends

Taynara Alves de Carvalho, Alexandra Helena de Barros, Rachel Farias Magalhães, Milton Faria Diniz, Lídia Mattos Silva Murakami, Jorge Carlos Narciso Dutra, Natália Beck Sanches and Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra e20250026

Assessment of modified poly(ethylene terephthalate) films under anaerobic conditions

João Gabriel Machado de Avellar, Gisely Alves da Silva, Renan Rogério Oliveira de Souza, Mariana Alves Henrique, Jorge Vinicius Fernandes Lima Cavalcanti, Yeda Medeiros Bastos de Almeida, Maria de Los Angeles Perez Fernandez and Glória Maria Vinhas ....................................................................................................................................................................... e20250027

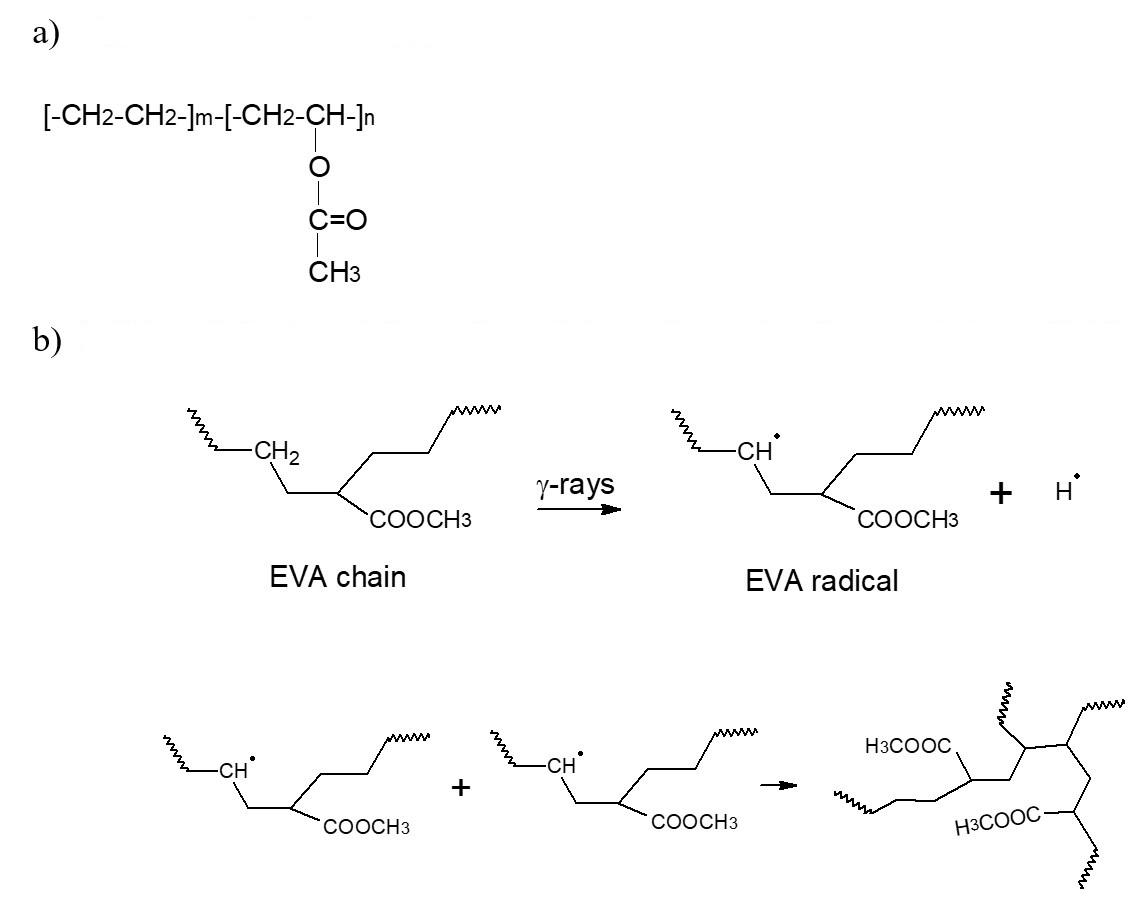

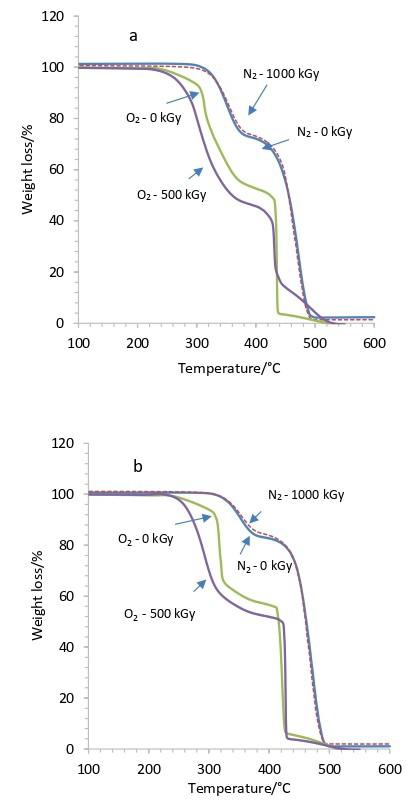

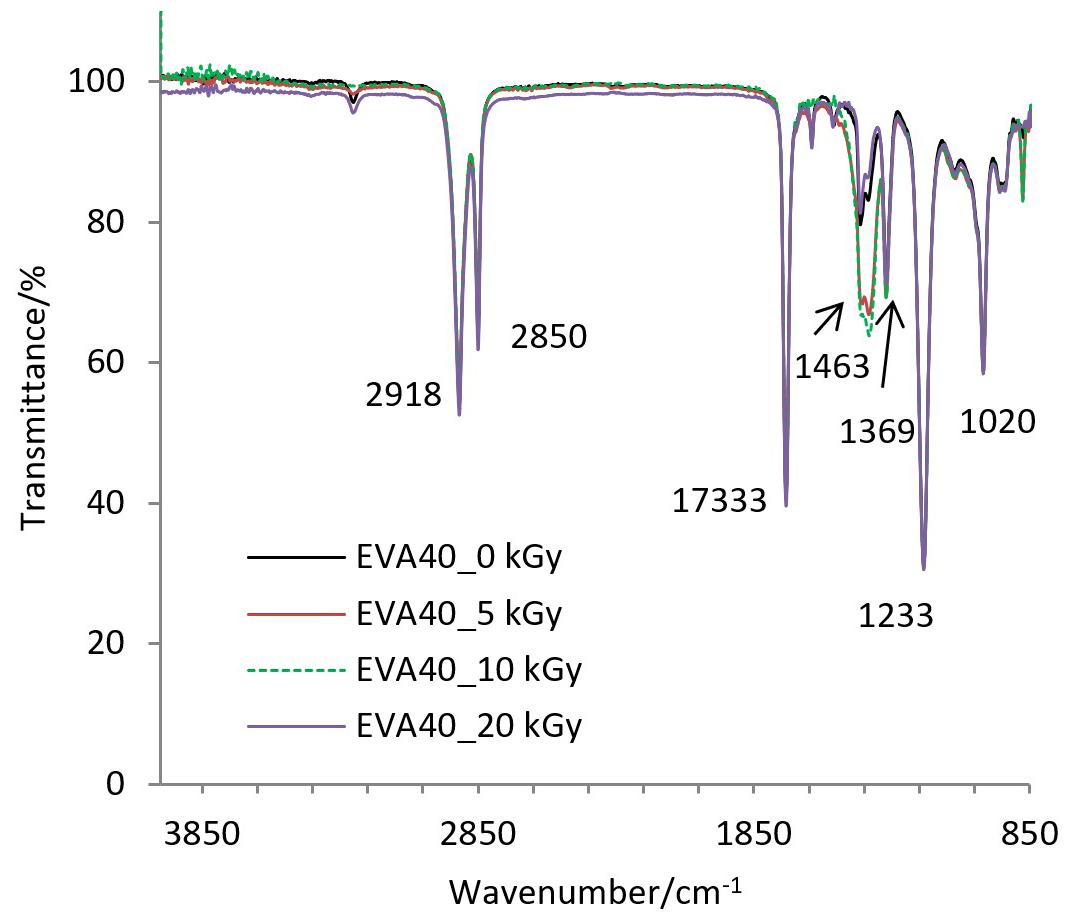

Gamma-irradiation effects on poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) (EVA)

Maria Thalita Siqueira de Medeiros, Thaíses Lima, Patricia Araújo and Elmo Silvano de Araújo e20250028

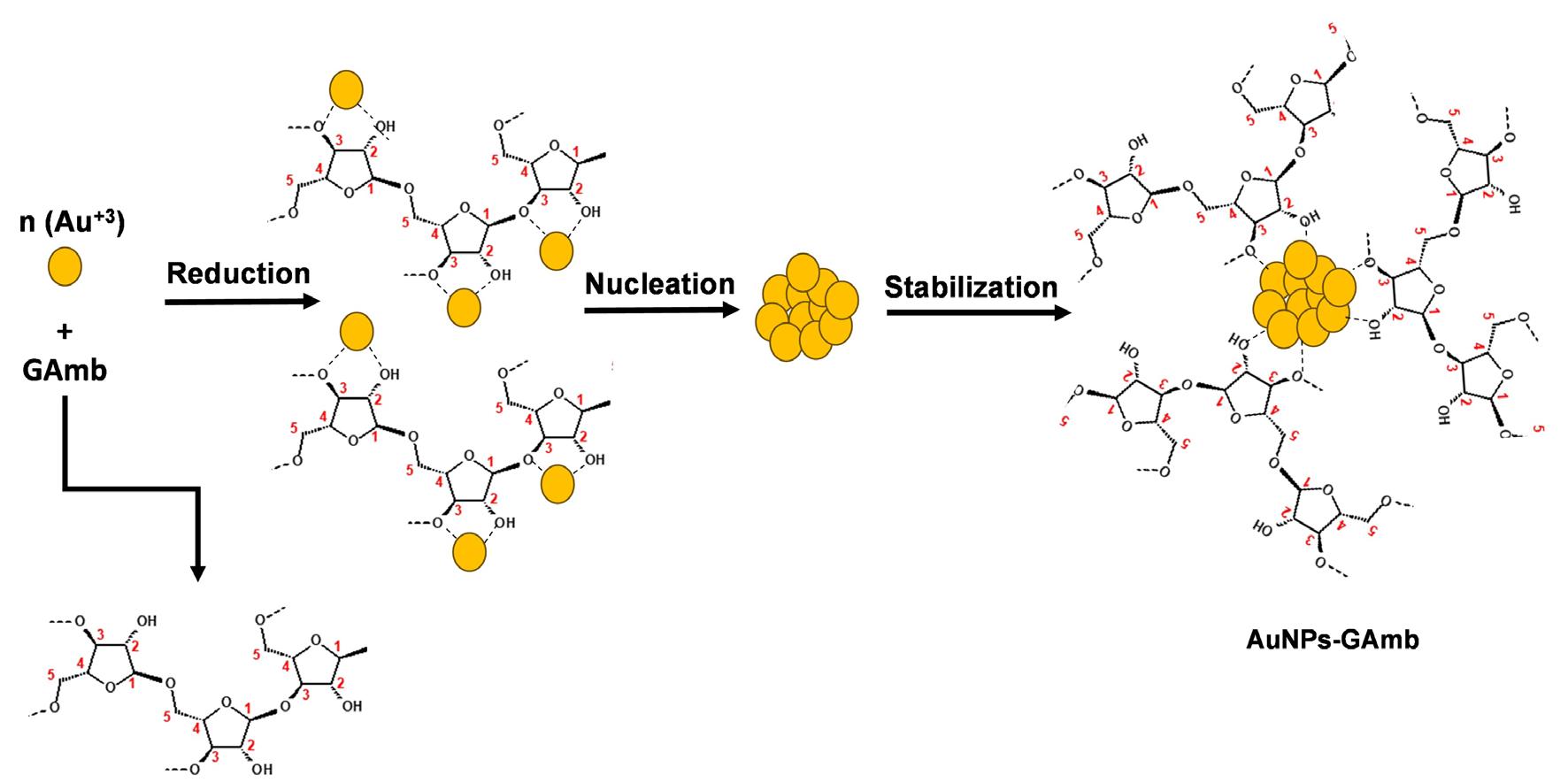

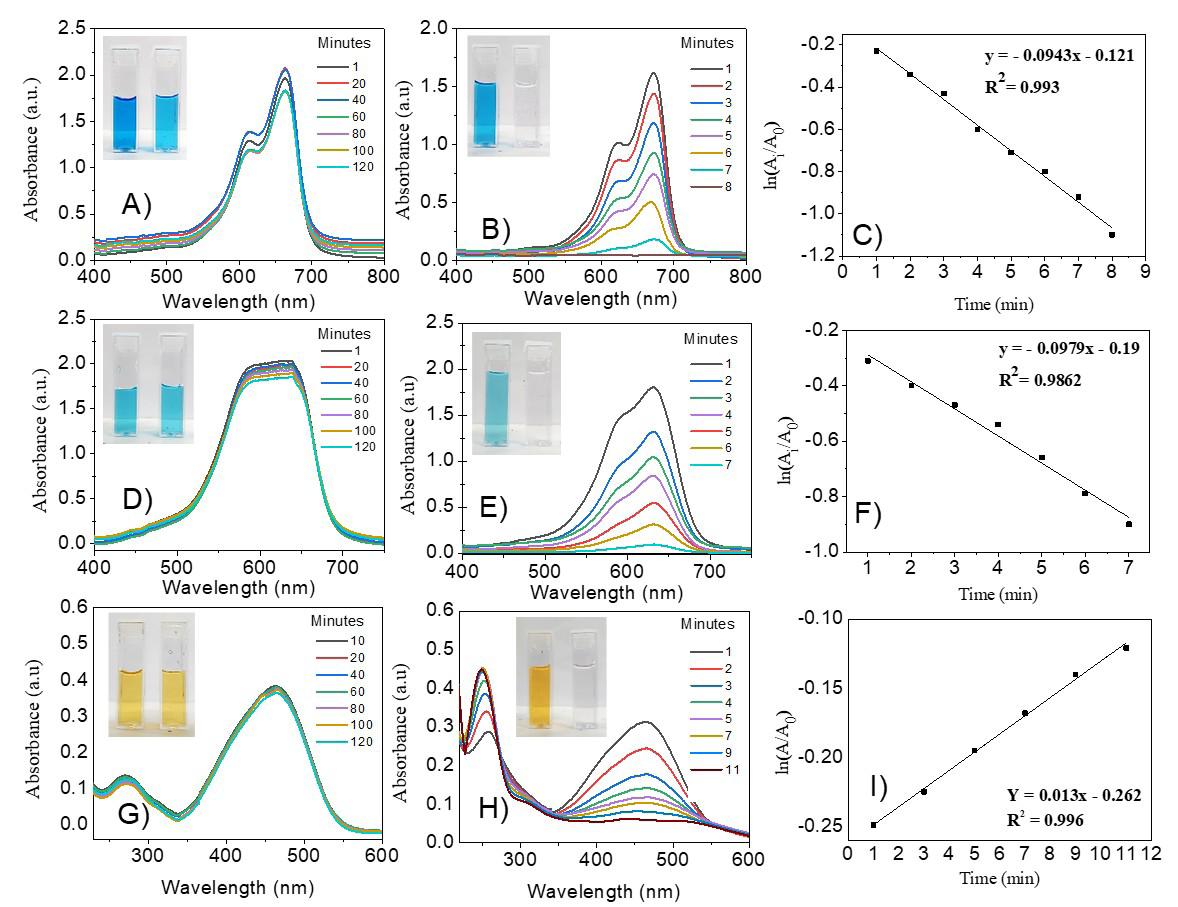

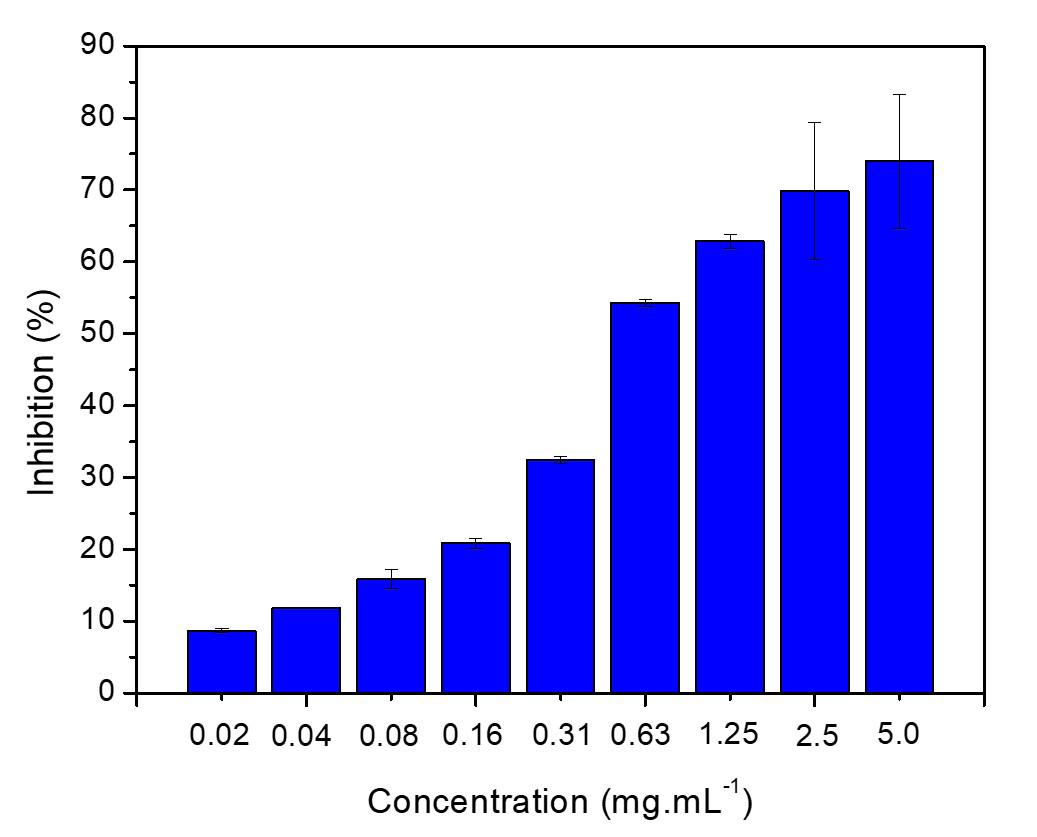

Gold nanoparticles based on polysaccharide from Amburana cearensis for organic dyes degradation

Eziel Cardoso da Silva, Emanuel Airton de Oliveira Farias, Thais Danyelle Santos Araújo, Alyne Rodrigues Araújo, Geanderson Emilio de Almeida, Lívio César Cunha Nunes and Carla Eiras e20250029

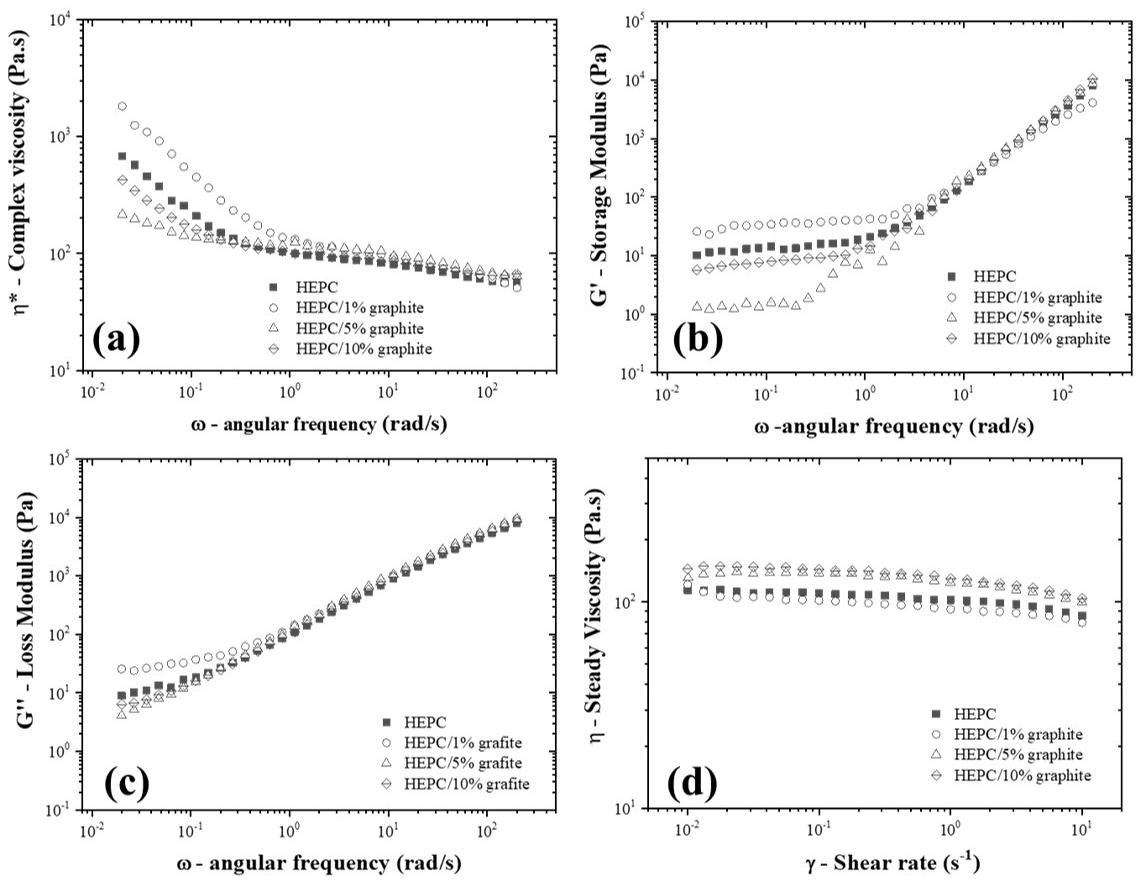

Sustainable heterophasic ethylene-propylene copolymer composites with recycled aircraft graphite for antistatic packaging

Ágatha Missio da Silva, Erick Gabriel Ribeiro dos Anjos, Thaís Ferreira da Silva, Rieyssa Maria de Almeida Corrêa, Thiely Ferreira da Silva, Juliano Marini and Fabio Roberto Passador e20250030

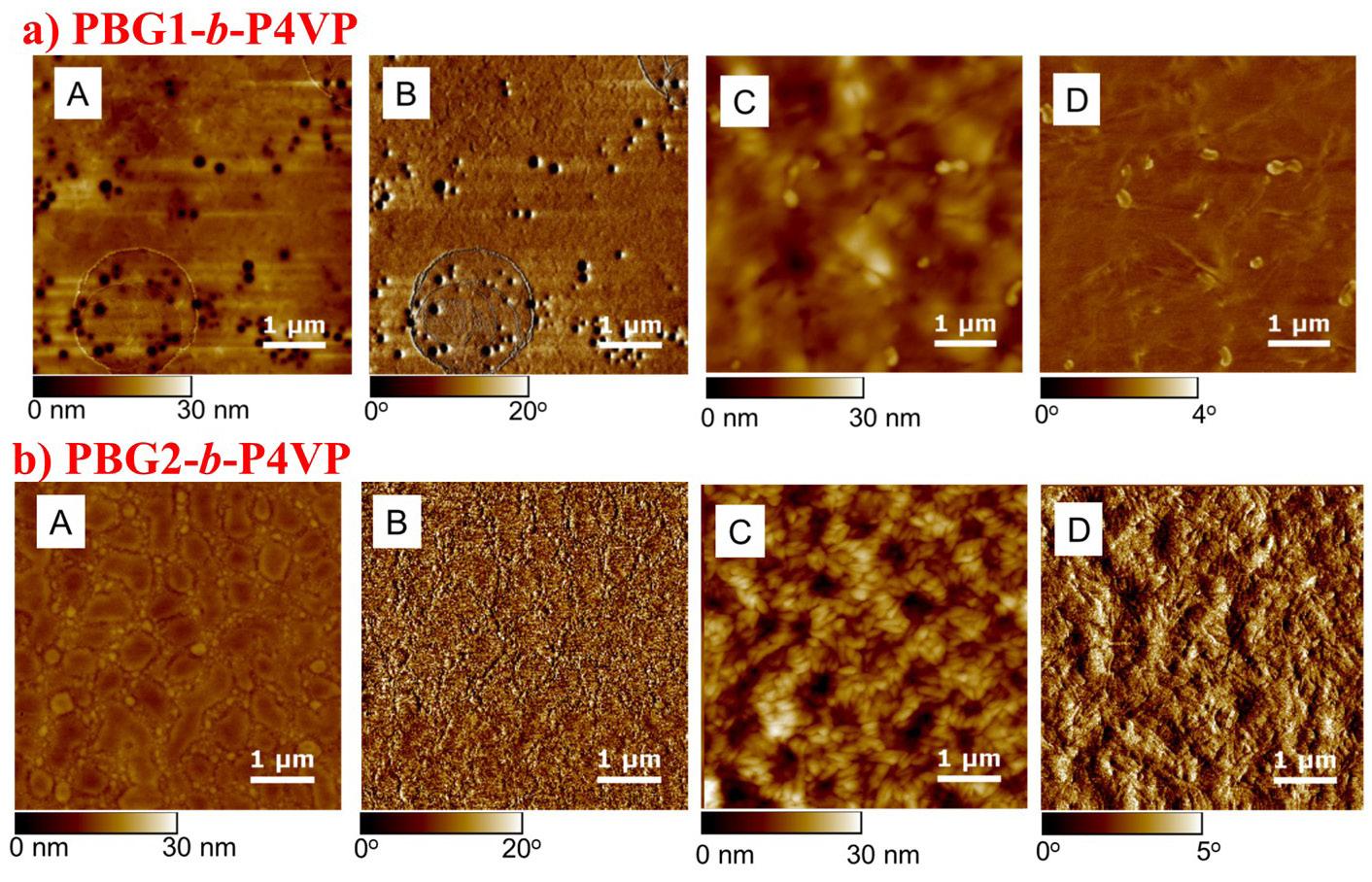

Synthesis of well-defined polypeptide-based diblock copolymers

Thuy Thu Truong, Luan Thanh Nguyen, Tin Chanh Duc Doan, Le-Thu Thi Nguyen and Ha Tran Nguyen e20250031

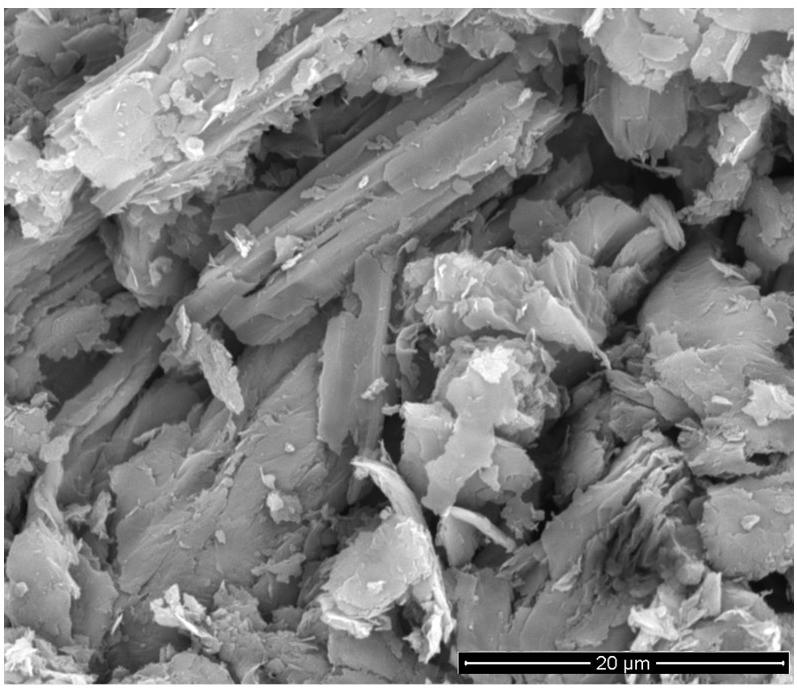

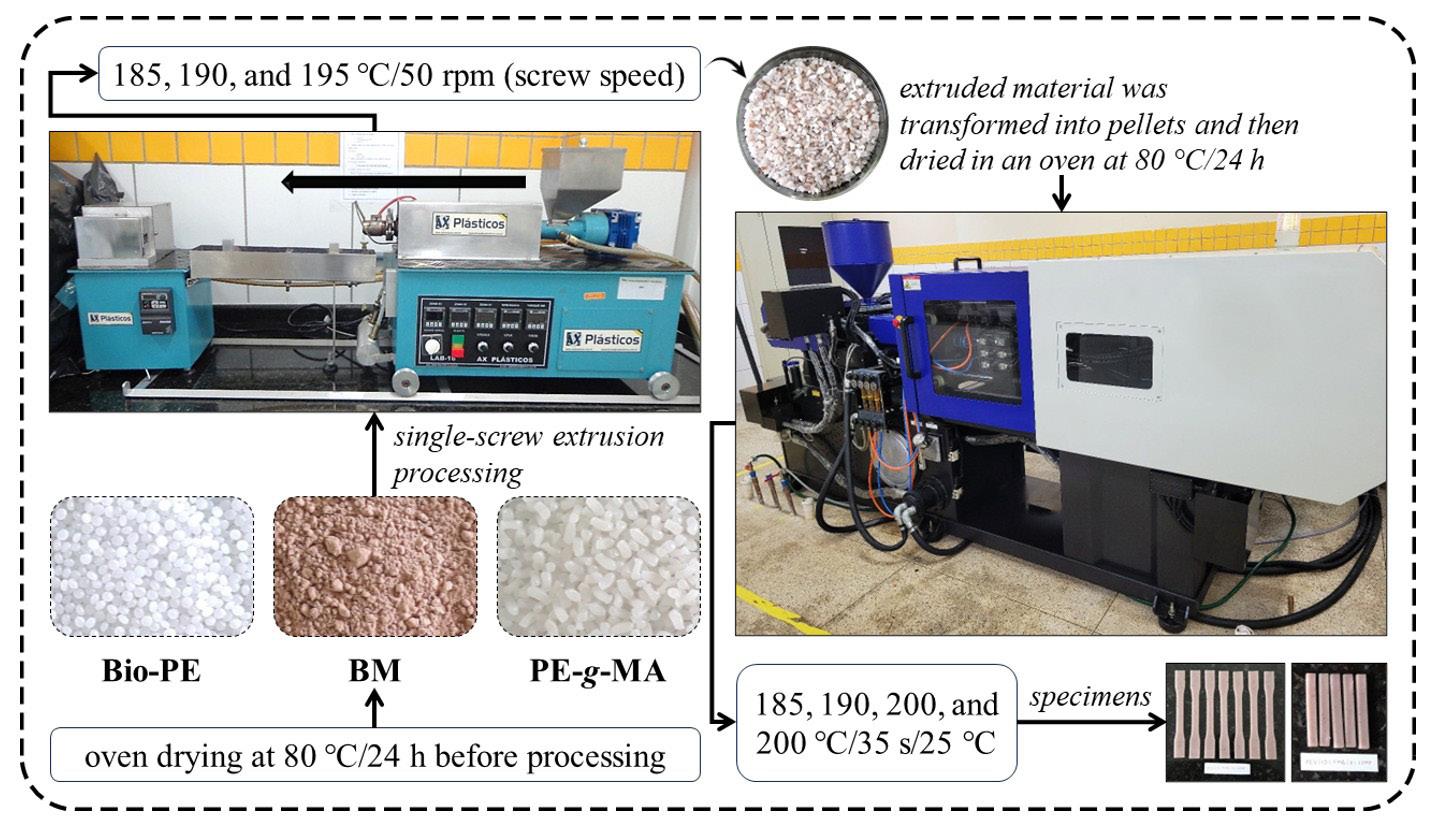

Development of green composites based on bio-polyethylene and babassu mesocarp

Crisnam Kariny da Silva Veloso, Lucas Rafael Carneiro da Silva, Ruth Marlene Campomanes Santana, Tatianny Soares Alves and Renata Barbosa e20250032

Magnetic poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-divinylbenzene) with amino groups for chromium VI removal

Washington José Fernandes Formiga, Henrique Almeida Cunha, Manoel Ribeiro da Silva, Ivana Lourenço de Mello Ferreira, Jacira Aparecida Castanharo and Marcos Antonio da Silva Costa e20250033

Crosslinking agent in the production of biodegradable whey-gelatin films

Carolina Antoniazzi, Jocelei Duarte, Wendel Paulo Silvestre and Camila Baldasso e20250034

Sustainable styrene-butadiene composites with sisal fiber and rubber waste from footwear Alexandre Oka Thomaz Cordeiro, Marcelo Eduardo da Silva and Cristiane Reis Martins

Sustainable recycling of butyl rubbers: an insight into the radiation processing

e20250035

Traian Zaharescu, Ademar Benévolo Lugao, Heloísa Augusto Zen, Radu Mirea and Dorel Buncianu e20250036

A new class of polymers has been used in patients for the first time. The compound is the first new drug solubilising agent in decades. Introduced in 2014 by chemist Matthias Barz from Leiden University, it offers a unique alternative to current options.

Getting your molecules into patients: that is the ultimate goal. Matthias Barz, chemist at LACDR, is extremely content with this milestone in his drug delivery journey. ‘When I started, people told me this would never work. Luckily, the company Lubrizol believes in these materials. And now, here we are. A phase 1 clinical trial has started.’

The polymers presented by Barz aren’t drugs themselves. They’re excipients: ‘helper substances’ that improve how a medicine works, for example by enhancing solubility or stability. While they don’t directly cause a therapeutic effect themselves, excipients can influence how well a patient tolerates a drug. The most commonly used ones are hardly or not at all biodegradable and remain in the body, leading to adverse effects over time.

The new class of polymers, called polypept(o)ids, are made from body-own building blocks, amino acids. Because the body recognises them as ‘self’, they are better tolerated and are broken down over time. This makes them less likely to trigger immune reactions even after multiple doses.

Polypept(o)ids combine two parts: polypeptides (similar to natural proteins) and polypeptoids (more stable and less likely to provoke the immune system). A key poylpeptoid is polysarcosine, a polymer that adds “stealth” and body suitability. The chemistry isn’t new, but Barz’s lab was the first to produce them in a pure and controlled way—making medical applications possible.

Barz found a way to turn short peptide chains into longer, functional polymers. These behave like polyethylene glycol (PEG), currently the most widely used polymer in biomedicine. ‘We wanted a polymer with PEG-like properties, but biodegradable into fragments, which are safe and familiar to our body,’ he explains.

Eventually, Kevin Sill and Bradford Sullivan patented a version of this polymer. They tested it across various drug types and found it worked well. The rights were later acquired by Lubrizol, a mid-sized pharmaceutical company. Lubrizol developed the product further, branded it as Apisolex®, and took the leap to bring the system to patients.

This is a rare achievement. Barz notes that no new excipient has been introduced in decades. ‘Pharmaceutical companies don’t like taking risks for very good reasons. The drug itself might already fail—so adding a new ingredient introduces more uncertainty. Most companies stick with what’s already used.’ But what’s already broadly used might have its downsides. It is known that PEG causes immune responses and can accumulate in liver and spleen.

But both Barz and Lubrizol believe polypept(o)ids are worth the risk. They are biodegradable and highly stable in water, which makes them ideal for liquid drug formulations or vaccines. ‘Many biodegradable materials degrade too quickly in aqueous solution,’ Barz says. ‘Ours stay stable.’

Besides Apisolex® from Lubrizol, other companies, like Curapath, make a broad range of polypept(o)ides commercially available for fundamental research and drug development, which enables now researchers around the world to explore the potential of the polymers introduced by the Barz lab.

‘People are hesitant, even when the science is solid’

Barz hopes the results of this first study in humans will be promising. In the long term, he believes regulatory agencies will demand that all injectable materials be either fully metabolised or fully excreted. That would give biodegradable excipients a big advantage.

Still, adoption will take time. ‘If you say we now have something better, you’re implying that older treatments, like the COVID vaccine, used something less ideal,’ Barz explains. ‘That makes pharmaceutical industry hesitant, even when the science is solid.’

He hopes this breakthrough will inspire young scientists. ‘Everyone said this wouldn’t work. But science should always strive for innovation. You need some luck and brave partners, but never stop trying remains a necessity.’

Source: Leiden University – universiteitleiden.nl

December

Fire Resistance in Plastics

Date: December 1-3, 2025

Location: Düsseldorf, Germany

Website: ami-events.com/event/5e2d20bb-0531-4947-9d805c827694a2cf/home?RefId=website

European Bioplastics Conference

Date: December 2-3, 2025

Location: Berlin, Germany (hybrid)

Website: european-bioplastics.org/events/ebc

Polymer Engineering for Energy

Date: December 2-3, 2025

Location: London, United Kingdom

Website: ami-events.com/event/d1969227-3d81-4adf-90332bdb782f9d71/summary?RefId=Website_AMI

Polyolefin Additives

Date: December 2-3, 2025

Location: Cologne, Germany

Website: ami-events.com/event/c4f01ff1-939e-4a06-aaac80dc63435792/summary?RefId=Website_AMI

2026

February

Polyethylene Films

Date: February 2-4, 2026

Location: Tampa, Florida, United States of America

Website: ami-events.com/event/c7892475-3923-495a-979580fd0384803a

Polymers in Hydrogen and CCUS Infrastructure

Date: February 10-11, 2026

Location: Vienna, Austria

Website: ami-events.com/event/024afd7e-7a6a-40b7-b4a893a6eb9b92f2

March

2nd Global Polymers and Materials Congress

Date: March 23-24, 2026

Location: Rome, Italy

Website: globalpolymersmaterialscongress.com

April

2nd International Conference on Advance Chemical and Material Science (ACMS-2026)

Date: April 12-14, 2026

Location: Kolkata, India (hybrid)

Website: ceie.org.in/acms2026

Inscitech Meet on Polymer Science and Composite Materials (IMPOLYMER2026)

Date: April 20-22, 2026

Location: Rome, Italy

Website: inscitechsummits.com/2026/polymer-science

May

Fire & Polymers 2026

Date: May 17-20, 2026

Location: San Diego, California, United States of America

Website: polyacs.org/2026fireandpolymers

Polymer Sourcing and Distribution

Date: May 19-21, 2026

Location: Hamburg, Germany

Website:ami-events.com/event/aa711e6d-2de5-4e11-82ba97fdd7d4e05b

41st International Conference of the Polymer Processing Society (PPS-41)

Date: May 31-June 4, 2026

Location: Salerno, Italy

Website: pps-41.org

June

Bordeaux Polymer Conference (BPC 2026)

Date: June 1-4, 2026

Location: Bordeaux, France

Website: bpc2026.u-bordeaux.fr/en

87th Prague Meeting on Macromolecules Smart Materials: Self-Organizing Polymers at the Interface of Technology and Nature (PMM 87 Smart Materials)

Date: June 21-25, 2026

Location: Prague, Czech Republic

Website: imc.cas.cz/sympo/87pmm

6th Global Conference on Polymers, Plastics & Composites (PPC-2026)

Date: June 24-25, 2026

Location: Barcelona, Spain (hybrid)

Website: polymers-plastics.org

Polymers 2026: Trends, Innovation and Future

Date: June 25-28, 2026

Location: Nanjing, China

Website: sciforum.net/event/polymers2026

Polymer Engineering and Sciences International (PESI 2026)

Date: June 28-July 2, 2026

Location: Kanazawa, Japan

Website: polymers-int.org

July

Polymers and Footwear Innovations

Date: July 22-23, 2026

Location: Portland, Oregon, United States of America Website: ami-events.com/event/749a47b2-12dd-4e1d-a1090febf35491e5

9th International Congress on Advanced Materials Sciences and Engineering 2026 (AMSE-2026)

Date: July 22-24, 2026

Location: Zagreb, Croatia

Website: istci.org/amse2026/index.asp

4th International Summit on Biopolymers and Polymer Science (ISBPS2026)

Date: July 23-25, 2026

Location: Prague, Czech Republic Website: polymerscience2026.spectrumconferences.com

51st IUPAC World Polymer Congress (MACRO 2026)

Date: July 28-31, 2026

Location: Sarawak, Malaysia

Website: macro2026.org

August

12th International Conference on Chemical and Polymer Engineering (ICCPE 2026)

Date: August 18-20, 2026

Location: London, United Kingdom Website: cpeconference.com

3rd Edition Global Summit on Polymer Science & Composite Materials

Date: August 24-25, 2026

Location: Paris, France

Website: globalpolysciencesummit.com

Global Summit on Sustainable Biopolymers and Polymer Applications (POLYMERS2026)

Date: August 26-27, 2026

Location: Venice, Italy Website: biopolymers.researchconnects.org

September

Bioplastics

Date: September 1-2, 2026

Location: Cleveland, Ohio, United States of America

Website: ami-events.com/event/a57ba0e7-de68-4cf6-b4c58c0955be8ef5

Annual Global Summit on Polymers and Composite Materials (AGSPOLYMERS2026)

Date: September 21-23, 2026

Location: Prague, Czech Republic

Website: vividglobalsummits.com/2026/composite-materials

October

5th International Conference on Polymer Science and Engineering

Date: October 7-9, 2026

Location: San Francisco, California, United States of America

Website: polymers.unitedscientificgroup.org

XIX Latin American Symposium on Polymers and XVII IberoAmerican Congress on Polymers - SLAP 2026

Date: October 19-23, 2026

Location: Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

Website: slap2026.com.br

Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan1* , Kathiresan Marimuthu2 , Prashanth Shanmugam1 and Moganapriya Chinnasamy3

1Department of Aeronautical Engineering, Excel Engineering College, Komarapalayam, Tamil Nadu, India

2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Excel Engineering College, Komarapalayam, Tamil Nadu, India

3School of Mechanical Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, India

*sreeraja2010@gmail.com

Obstract

In this work, a study was undertaken to explore the possibility of using leftover tamarind fruit fibres as reinforcement in PLA and HDPE matrix. PLA and HDPE polymers form minimum 75% of the total polymers used in the composites. PLA and HDPE was mixed with natural fibres (5 wt.%, 10 wt.%, 15 wt.%, 20 wt.% and 25 wt.%,) individually and also as a hybrid filler to enhance its mechanical properties. Characterizations, mechanical behaviour and microscopic investigation were performed to understand the excellent mechanical properties and good chemical resistance of the prepared composites, which demonstrated potential suitability for semi-structural applications.

Keywords: polymer composites, Tamarindus indica fruit fibre, mechanical properties, sustainability, morphological analysis.

Data Availability: Research data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

How to cite: Nagarajan, S., Marimuthu, K., Shanmugam, P., & Chinnasamy, M. (2025). Fabrication, characterization and mechanical behaviour of Tamarindus indica fruit fibre-reinforced polymer composites. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 35(3), e20250025. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1428.20240122

Growing global interest in the usage of environmentally friendly bio-waste materials-based polymer composites with the necessary mechanical properties that has been spurred by increased environmental consciousness[1]. Agro bio-waste fillers are a promising potential replacement for synthetic fibre polymer goods in environmental limits due to their wide availability and cost-effective processing[2] Natural fillers in a polymer matrix can offer substantial benefits over typical fillers used in composites, and their use is growing globally due to the influence of low cost, low density, renewable, biodegradable, desirable qualities, and environmental friendliness. Nagarjun et al.[3] showed the mechanical characteristics of PLA composites with tamarind and date seed Micro fillers. The composites were made using the compression moulding method. The seed filler reinforcement greatly enhanced the tensile strength of the PLA matrix, according to the tensile data. Both tamarind and palm particle reinforcements nearly increased the flexural and impact strength of PLA matrix. Stalin et al. [4] experimented the usage of tamarind seed filler (TSF) as reinforcement in vinyl ester composites. The composite plates have been fabricated by compression moulding machine with TSFs of varying wt% from 5 to 50 as reinforcement material, and their properties such as tensile, flexural, impact,

hardness, water absorption, heat deflection tests, and thermo gravimetric analysis are studied. On jute poly-lactic acid resin composite, Ramachandran et al.[5] performed different experiments such as Impact (IZOD and CHARPY tests), Differential Scanning Calorimeter test, Fourier Transform Infrared test, and Optical Imaging. The testing revealed that the results were comparable to synthetic composites such as polyester and epoxy. Mofokeng et al.[6] studied morphology, thermal and dynamic mechanical properties, and degradation patterns. SEM micrographs of the composites demonstrate more intimate contact and better interaction between the fibres and PLA than PP. The presence of hydrogen bonding interaction between PLA and the fibres was validated by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy data, which demonstrated the presence of enhanced interaction. The thermal stability of both polymers improved with increasing fibre content, with PP showing a more substantial improvement. Curcumin-loaded electro spun Poly (lactic acid) (PLA) composite membranes were created by Chen et al.[7] . Curcumin was loaded with varying concentrations of 1, 3, and 5 wt percent to investigate its anticoagulant properties as a drug-eluting stent. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to examine the structure of the composite membrane, and the results indicated that both

Nagarajan, S., Marimuthu, K., Shanmugam, P., & Chinnasamy, M.

PLA and curcumin were present in the composite membrane without any chemical reaction. In the recycling of polyethylene terephthalate, Aldas et al.[8] discovered certain biopolymers that were regarded as pollutants (PET). The results revealed that PET-PLA and PET-PHB miscibility is good. However, due to the high processing temperatures employed in PET recycling, PHB is damaged; in the meantime, PET and TPS are poorly miscible, which is reflected in the microstructure. Sachin et al.[9] developed a composite that can be utilised as a substitute for standard plywood in the automotive, airline, and railway industries for furniture, building infrastructure, and interior components. PLA and NWF were used to create a new bio composite, which was then tested for mechanical properties. Natural fibres can be employed as reinforcement in polymers made from renewable raw materials, according to Oksman et al.[10]. Flax fibres and polylactic acid were used as the materials (PLA). PLA is a lactic acid-based thermoplastic polymer that has primarily been utilised in biodegradable items such as plastic bags and planting cups, but it can also be used as a matrix material in composites in theory. Maheswari et al.[11] experimented with tamarind fibres recovered by the water retting technique from ripened fruits. The hand lay-up technique was used to construct composite samples using these fibres as reinforcement and unsaturated polyester as matrix. Jo et al.[12] investigated ABS-based automotive console boxes with better environmental friendliness using composites made of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer (ABS) and poly(lactic acid). Nuthong et al.[13] found that adding fillers or reinforcements to PLA improves its impact characteristics. The brittleness of PLA polymer necessitates the modification for more practical usage. Alternative reinforcements in PLA composites included bamboo fibre, vetiver grass fibre, and coconut fibre. Untreated and flexible epoxy-treated composites with varying reinforcing amounts were injection moulded. With increasing fibre content, the impact strength of natural fibre reinforced PLA composites dropped[13,14]. Natural fibre composites, as investigated by Siregar et al.[15] in the field of materials, have piqued many people’s interest due to their fundamental biodegradability property. As a result, unlike synthetic fibre, pineapple leaf fibre is not only biodegradable but also environmentally benign. Somashekhar et al.[16] investigated coconut shell powder, which has several advantages over other materials, including low cost, renewable, high specific strength to weight ratio, low density, low abrasion on machine, and environmental friendliness.

2.1 Matrix

The virgin PLA pellets and HDPE pellets were purchased from the local merchant Augment 3Di, Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu State, India and Kings Polymer, Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu State, India. As mentioned by the seller, PLA has the melt flow index of 10-30 g/10 min with density of 1.24 g/cm3 at 190 °C. 65, 120 and 180 °C are the glass transition, crystallization and melting point temperatures, respectively[3]. Both PLA and HDPE pellets were kept in a dry air oven before processing to remove the moisture. During injection moulding, both PLA and HDPE were melted at their melting point temperature. PLA is a

polyester manufactured from fermented corn, cassava, maize, sugarcane or sugar beet pulp. These renewable resources sugar is fermented and converted to lactic acid, which is subsequently converted to polylactic acid or PLA. HDPE is the most environmentally friendly of all plastics, emitting no toxic gases into the atmosphere.

The tamarind fruit fibre (TFF) of around 2.5 kg was collected from Salem District, Tamil Nadu State, India. The collected fibres were treated with water. After cleaning with water, the fibres were dried for 6 hrs in direct sunlight in order to remove the water content by means of evaporation. Moreover, the remaining moisture content is then removed by drying it in a hot air oven. The dry fibres were next processed into a powder form (25–60 m) in a local flour mill at 500 rpm for 1 hr. 450 gms of TFF powder were finally obtained after the grinding process.

Injection moulding is used to create various combinations of specimens (S1 to S18), as displayed in Table 1. The moulding process is carried out at Perumal Injection Moulding Company in Coimbatore District, Tamil Nadu State, India. The detailed process flow diagram of fabrication and testing of composites is shown in Figure 1. The machines hopper is filled with PLA pellets, HDPE pellets and TFF powder, as and when needed. Followed by material loading, the machine gets heated-up, melts and mixes the materials. The obtained paste is then injected into the die and specimen plates were created accordingly. A rectangular die with the dimensions of 147 cm × 98 cm × 4 cm is used in this study. A total of 18 plates were made, out of which pure PLA = 1, pure HDPE = 1, PLA + HDPE = 1, TFF powder + PLA = 5,

Fabrication, characterization and mechanical behaviour of Tamarindus indica fruit fibre-reinforced polymer composites

1. Overall process flowchart and obtained results.

Nagarajan, S., Marimuthu, K., Shanmugam, P., & Chinnasamy, M.

TFF + HDPE = 5, TFF + PLA + HDPE = 5. The different weight ratios for all the specimens are mentioned in Table 1

According to ASTM D 3039, tensile tests were performed on samples with dimensions 115 mm × 19 mm × 4 mm. The universal testing machine (UTM) with a load cell capacity of 100 kN was used for all the tests. During testing, the gauge length was set to 25 mm and the cross-head speed was kept at 5 mm/min. The displacement across the cross-head was measured using an external LVDT device. Five samples of each composition were examined and the average value was reported as the corresponding specimen’s tensile property.

The flexural characteristics of the test specimens were assessed using a three-point bending test. The test was carried out on samples with dimensions 115 mm × 12.7 mm × 4 mm, as specified by ASTM D 790. The support span was adjusted to 50 mm and the test was carried-out at a cross-head speed of 5 mm/min. Five samples were tested and the average flexural value was reported in all the cases.

The Charpy impact test was carried-out to determine the impact energy. The load is applied via an impact strike from a hefty pendulum hammer discharged from a fixed height location. The test material or specimen is placed at the bottom. The pendulum impacts the test piece and fractures it at the notch when it is released. The pendulum continues to swing lower than its original height. Simple calculations can be used to calculate the energy absorbed at the fracture. The technique can be used on both short and long fibre composites. The Charpy test is a defined method for determining how much energy a test material absorbs during a break. The test specimen is 4 mm thick as per ASTM D 4812. It is commonly used in industry since the results are inexpensive and rapid. The average value was calculated using five sample specimens for the Charpy test in all the conditions.

FESEM is a sophisticated microscope that provides higher magnification and the ability to view very tiny features at a lower voltage than conventional SEM. An instrument named CARL ZEISS (USA), model: sigma with Gemini column was used to observe the interaction between the TFF powder and the matrix (PLA and HDPE) with an accelerated voltage of 10 kV. The composite samples were coated with gold before the examination in order to avoid charging during the experiments. The sample portions were magnified as much as 3500 times during the examination.

FTIR testing is an analytical testing procedure that uses infrared radiation to identify organic and some inorganic chemicals (IR). It also identifies unfamiliar solid, liquid, or gaseous components. It mainly determines the presence of surface contamination on a material and, in some situations, quantify it. It is carried out in order to identify the chemical functional groups in the composite.

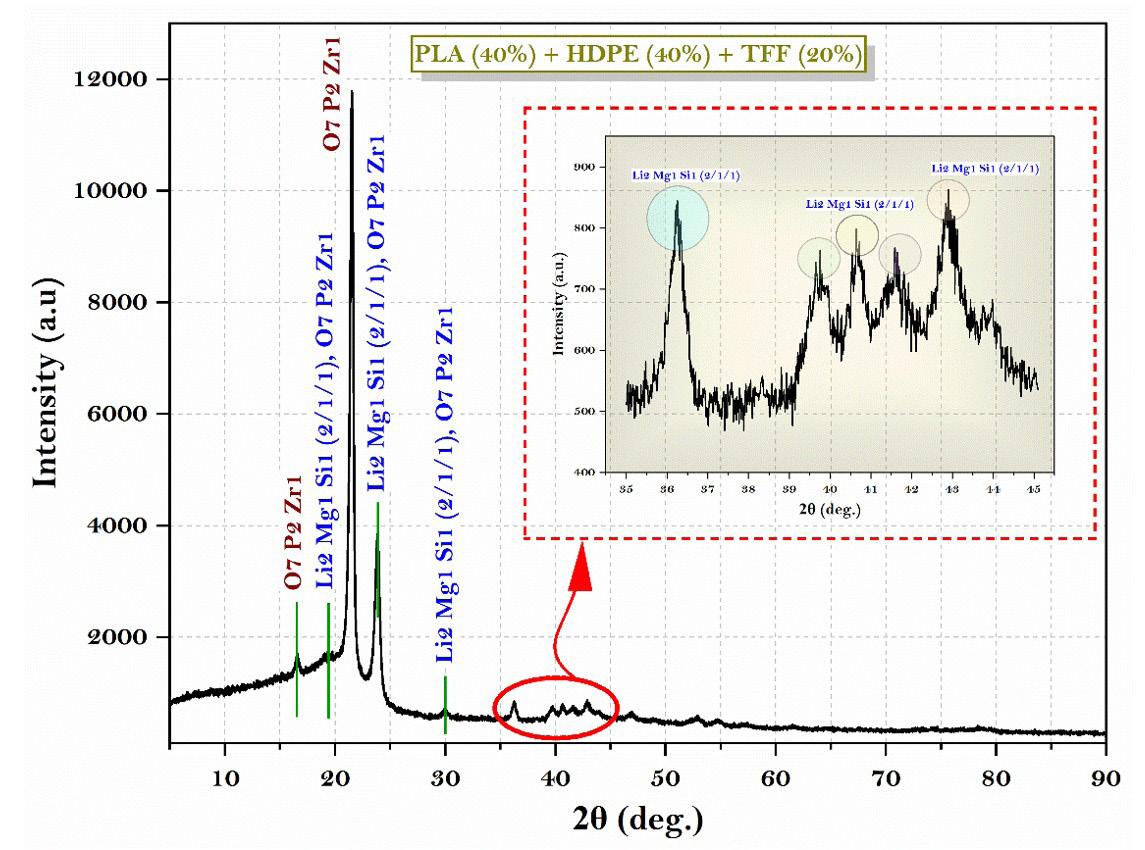

XRD analysis is used to detect the crystalline phases contained in a material and so reveal chemical composition information by studying the crystal structure. The phases are identified by comparing the obtained data to that in reference databases.

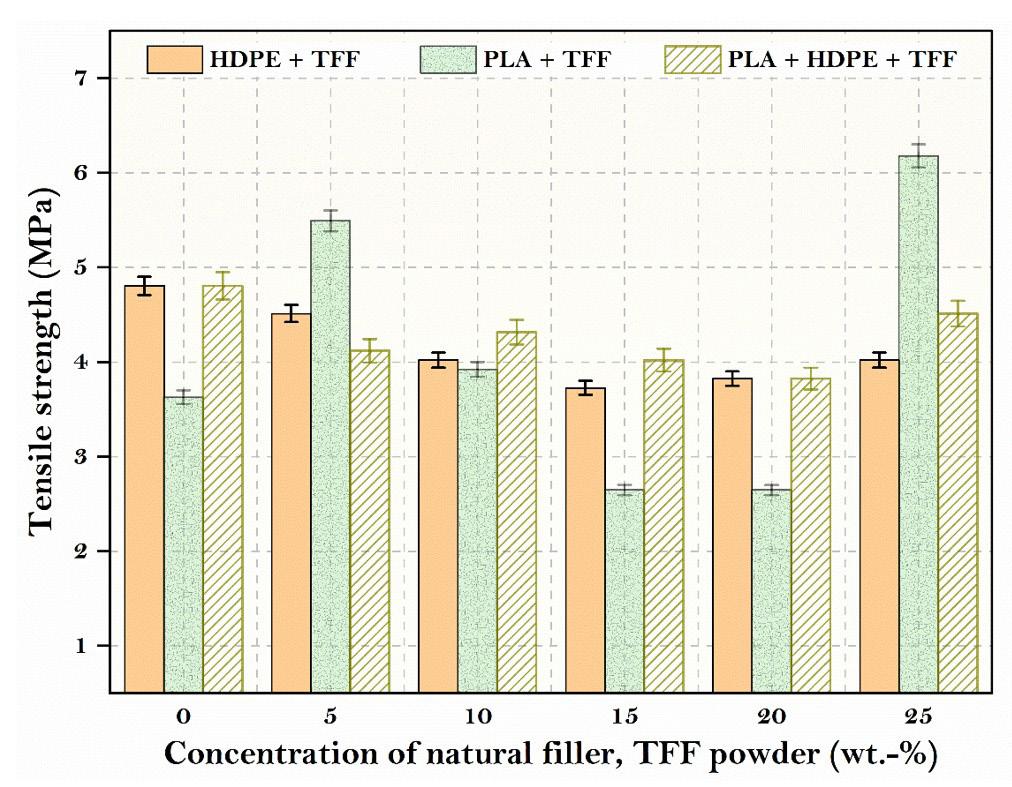

The addition of fillers (TFF powder) to the matrix has been demonstrated to improve the corresponding tensile characteristics (Figure 2). The tensile strength of the neat PLA matrix is improved by 2.55 MPa or 70.26 percent, when TFF powder was added. When the TFF powder concentration was 25 wt.-% with 75 wt.-% of PLA matrix polymer, the highest tensile property is achieved. Crack initiation and propagation at the inter-laminar area determines the strength of composites made with fillers in general. The addition of fillers reinforces the matrix material in this location, preventing crack start and allowing for excellent tensile strengths. The aggregation of fillers may have caused the tensile property to deteriorate. Overall, strong interfacial bonding has allowed stresses to flow from the matrix to the fibre, which increases the strength and stiffness.

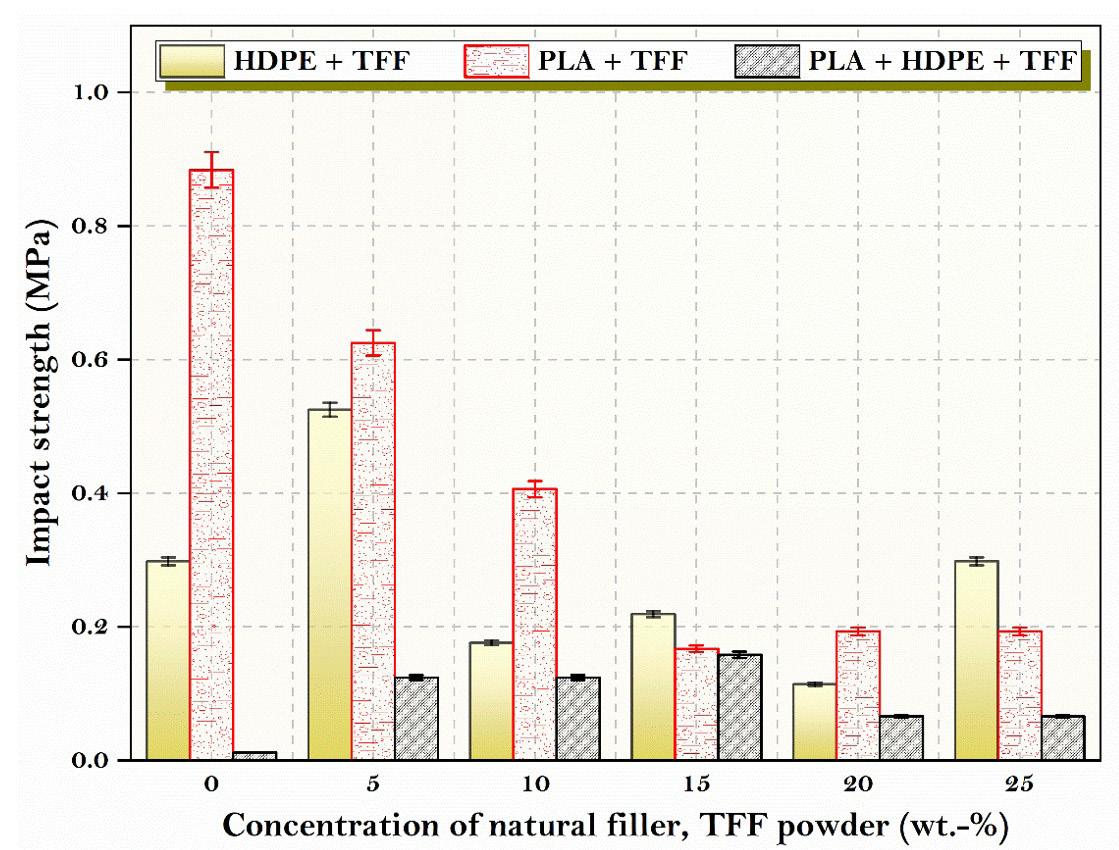

PLA was discovered to have higher impact strength than composites containing TFF powder fillers (Figure 3). This could be explained by PLA’s brittle nature at room temperature. The reduced impact strength was owing to

Fabrication, characterization and mechanical behaviour of Tamarindus indica fruit fibre-reinforced polymer composites

inadequate interfacial adhesion between the filler and the matrix, as well as the presence of larger voids, which caused specimens to break prematurely. The composites used in this investigation have 15 wt.-% TFF fillers and a PLA matrix. The impact strength of polymer was around 81 percent lower than that of plain PLA. The impact strength of HDPE + PLA composites was found to be lower than composites added with TFF, which could be due to HDPE + PLA’s ductile behaviour at room temperature. The composites with 15 wt.-% TFF fillers and an HDPE + PLA matrix polymer exhibit 31 percent better impact strength than the pure HDPE + PLA. Composites with 5 wt.-% TFF fillers and an HDPE matrix polymer displays 76 percent higher impact strength than pure HDPE.

3.3

Figure 4 shows the influence on the addition of micro fillers to the clean matrix which results in improved flexural characteristics. Flexural strength of HDPE is 4.22 MPa, PLA is 4.61 MPa and PLA + HDPE is 4.8 MPa. TFF + PLA, TFF + HDPE and TFF + PLA + HDPE composites all about doubled the flexural strength of its corresponding neat matrix. The flexural strength of PLA with TFF filler is enhanced by 13.64 percent or 4.8 MPa. The PLA composite with TFF filler has a higher flexural property due to its good size, which fills the spaces in the composites and effectively resists force. With 15 wt.-% TFF filler concentration and 85 wt.-% PLA matrix polymer, the greatest flexural strength of 8.06 MPa is achieved, which is 75 percent higher than pure PLA. The increase in flexural strength illustrates the superior matrix-filler absorption property.

3.4 FTIR analysis

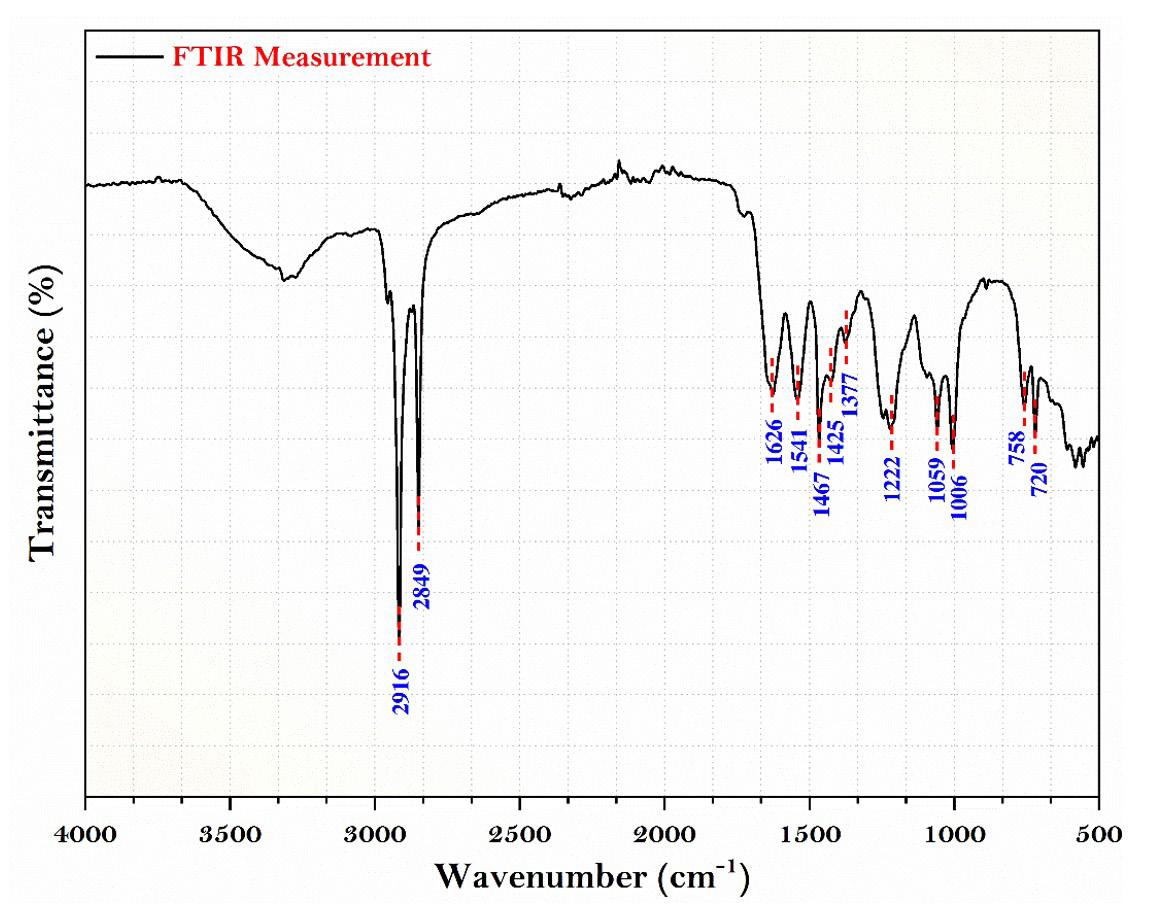

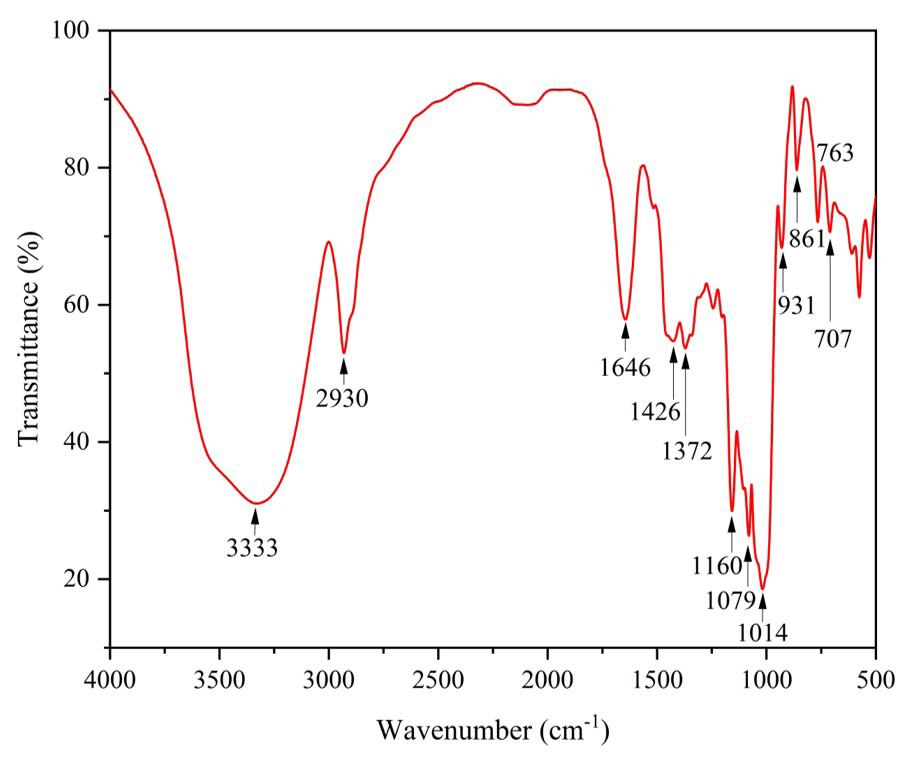

FTIR test is the straightforward method used to obtain an infrared spectrum of liquid, solid and gas absorption or emission. It can classify unidentified materials, determine sample quality and quantity the chemical component present in a mixture and so on. The stretches of different functional groups such as hydroxy isoxazole C4H3NO4 stretch, amide CO (Ninhydrin) stretch, polyetherimide (PEI) stretch are produced via the polycondensation reaction between bisphenol-A dianhydride such as tetracarboxylic dianhydride (produced from the reaction of bisphenol A and phthalic anhydride) and a diamine such as m-phenylene diamine and ethyl. The above composite result (Figure 5) is derived from the spectrum generated during an FTIR test and digitally cross-checked against established reference from libraries and databases to determine the type of substance.

3.5

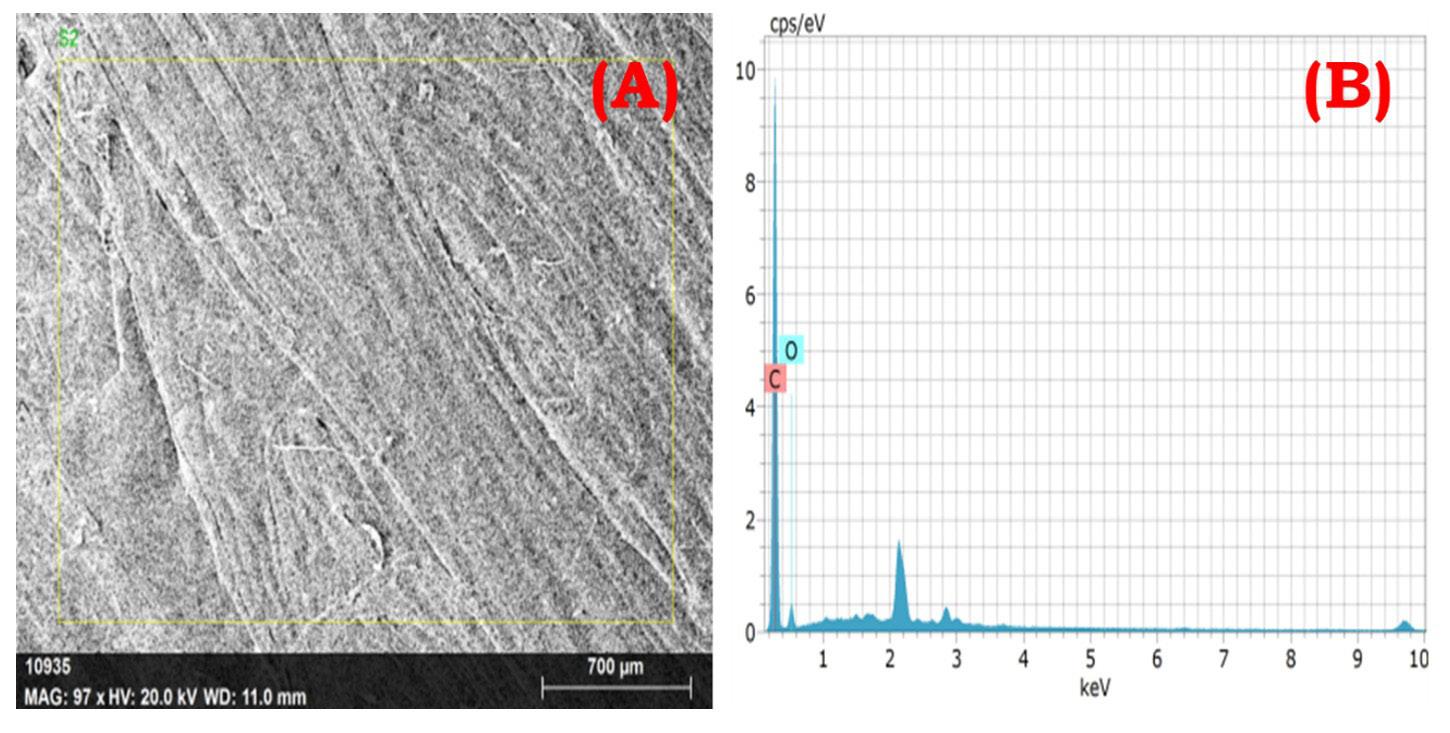

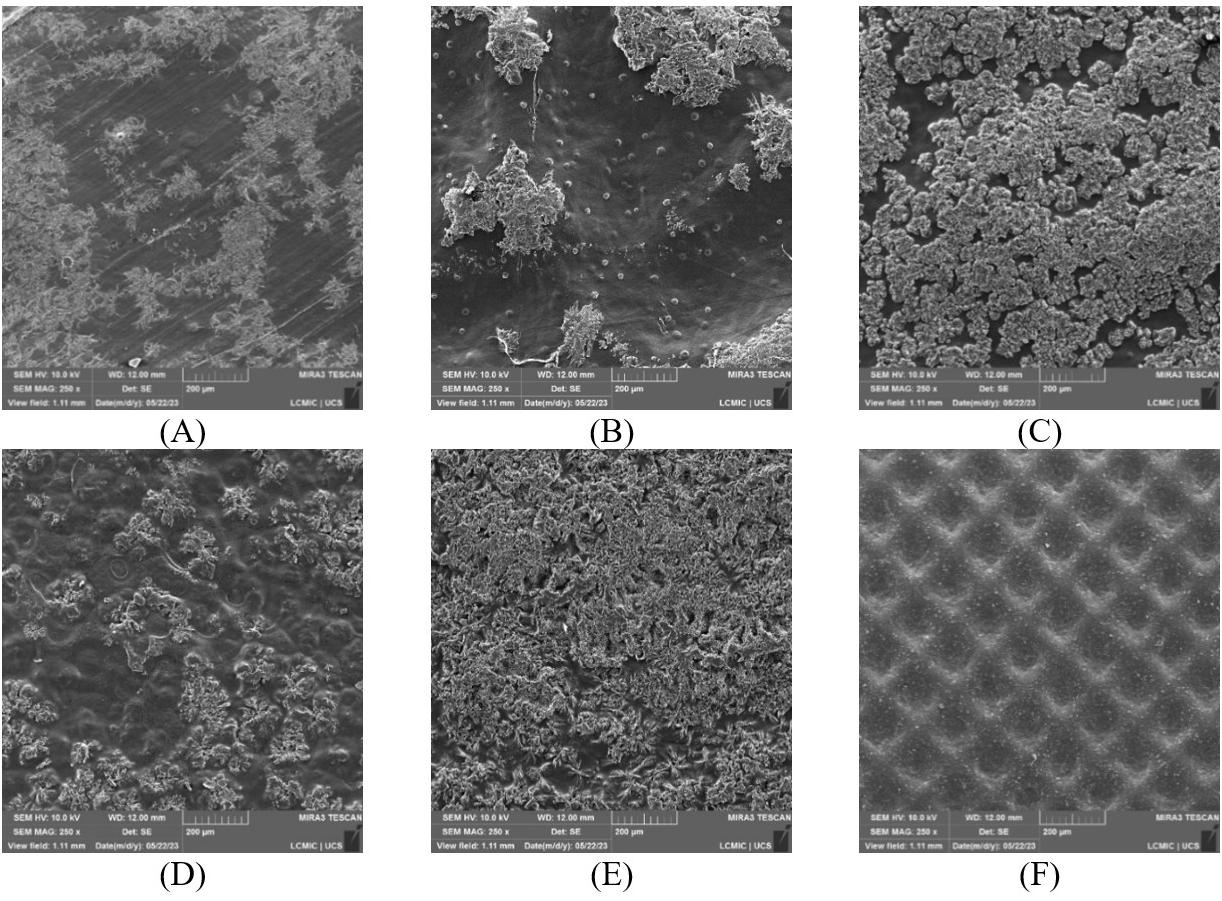

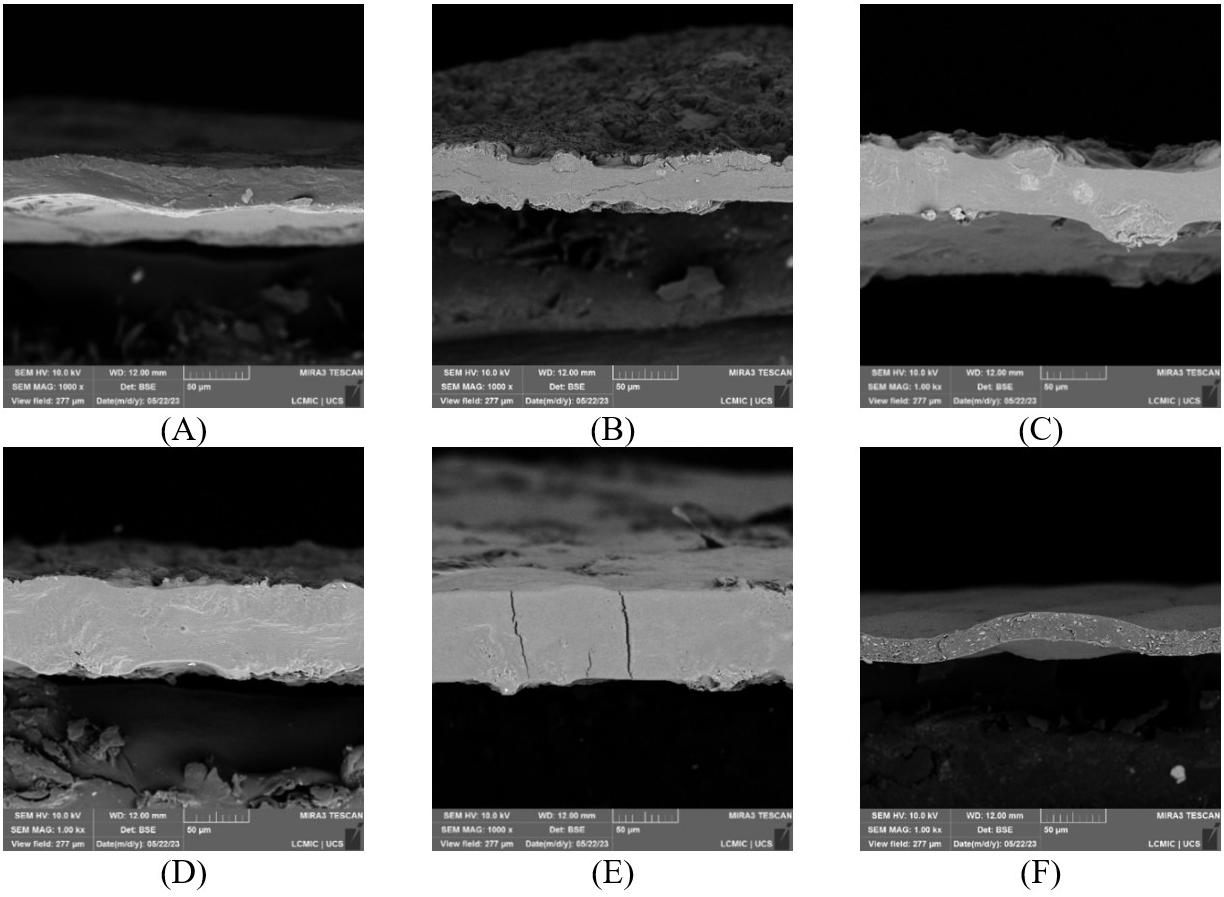

Figure 6A-6F illustrates the surface of TFF + PLA with 15 wt.-% filler concentration, which has the best tensile strength. Increased wettability is due to strong adherence between the filler and the matrix. It is due to the reinforcement and matrix’s increased interfacial contact. In the TFF + PLA composite, the filler dispersion was consistent, which helped to improve the tensile properties. In contrast, increasing the filler content in HDPE + TFF causes the fillers to clump together and separate from the matrix. It generates a discontinuity between the matrix and the filler, which aids

crack development and reduces the tensile performance. This is the main reason behind deteriorating the composite mechanical properties. Figure 7A and Figure 7B shows the chemical composition of TFF/PLA/HDPE. The elements spectrum of the TFF was obtained using a SEM with an EDAX instrument, Nano XFlash Detector model. The obtained peak demonstrates that carbon (85.82 percent) and oxygen (14.18 percent) make up the majority of the weight. The crystal structure of the PLA (40 wt.-%) + HDPE (40 wt.-%) + TFF (20 wt.-%) specimen was determined using XRD. The powdered particle is made up of several tiny and randomly oriented particles that are exposed to monochromatic X-ray radiation. Figure 8 depicts the appropriate XRD patterns of the specimen produced. The following peaks show the composites crystalline solid structure: 16.56°, 19.21°, 21.53°, 23.87°, 30.03°, 36.27°, 39.71°, 40.66°, 41.56°, 42.87°, 44.02°, 46.89°, 48.98°, 52.97°, 54.78, 57.31°, 61.64°, 74.36°, 78.46°, 36.27°, 39.71°, 40.66° and 41.00o. However, at 21.53°, the most intense peak of Li2 Mg1 Si1 can be seen, with a peak height of 10486.13 cts and a relative intensity of 100 percent. The discovered compounds Lithium Magnesium Silicide (2/1/1) (Li2 Mg1 Si1) with cubic crystal structure and Zirconium Diphosphate (O7 P2 Zr1) with orthorhombic crystal structure provide the crystal structure of PLA + HDPE + TFF composite.

Nagarajan, S., Marimuthu, K., Shanmugam, P., & Chinnasamy, M.

6. FESEM micrographs showing morphological features of the composite, highlighting agglomeration of fillers (A & B); rough surfaces (C & D); and uniform filler dispersion (E & F) at various magnifications.

the surface morphology of the composite at low magnification; and (B) corresponding EDS spectrum

Fabrication, characterization and mechanical behaviour of Tamarindus indica fruit fibre-reinforced polymer composites

4. Conclusions

In this study, compression moulding was used to create the TFF/PLA, TFF/HDPE, and TFF/PLA/HDPE composites. The mechanical behaviour of the composites was studied as a function of the concentration of TFF filler. The experimental findings led to the following conclusions:

The tensile results revealed that the TFF filler reinforcement enhanced the tensile strength of the PLA matrix substantially. TFF/PLA attained a maximum tensile strength of 5.98 MPa. With a 15 wt.-% TFF filler concentration and 75 wt.-% PLA matrix polymer, the greatest flexural strength of 8.06 MPa was reached, which is 75 percent higher than pure PLA. The impact strength of composites showed an opposite trend to that of neat PLA which is mainly due to brittle nature of PLA at room temperature. Thus, the TFF/PLA composite with 15 wt.-% filler concentration exhibited the highest tensile strength among the studied samples. In the TFF+PLA composite, the filler dispersion was consistent, which helped to improve the tensile properties. The above composite result is derived from the spectrum generated during an FTIR test and digitally cross-checked against established reference from libraries and databases to determine the type of substance. The discovered compounds Lithium Magnesium Silicide (2/1/1) (Li2 Mg1 Si1) with cubic crystal structure and Zirconium Diphosphate (O7 P2 Zr1) with orthorhombic crystal structure provide the crystal structure of PLA + HDPE + TFF composite. As a result, composites have shown exceptional matrix absorption by the fillers, resulting in enhanced mechanical behaviour. The material is suitable for low to medium-duty applications.

5. Author’s Contribution

• Conceptualization – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Data curation – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Formal analysis – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Funding acquisition – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu

• Investigation – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Methodology – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Project administration – Kathiresan Marimuthu

• Resources – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu

• Software – NA.

• Supervision – Kathiresan Marimuthu

• Validation – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Kathiresan Marimuthu; Prashanth Shanmugam; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

• Visualization – Kathiresan Marimuthu

• Writing – original draft – Sreenivasaraja Nagarajan; Prashanth Shanmugam

• Writing – review & editing –Kathiresan Marimuthu; Moganapriya Chinnasamy

6. References

1 Adeola, A., & Aworh, O. (2010). Sugar and dietary fibre components of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) Fruits from Nigeria. Nigerian Food Journal, 28(2), 32-40 http://doi. org/10.4314/nifoj.v28i2.62633

2 Jia, W., Gong, R. H., Soutis, C., & Hogg, P. J. (2014). Biodegradable fibre reinforced composites composed of polylactic acid and polybutylene succinate. Plastics, Rubber and Composites, 43(3), 82-88 http://doi.org/10.1179/1743289813Y.0000000070

3 Nagarjun, J., Kanchana, J., RajeshKumar, G., Manimaran, S., & Krishnaprakash, M. (2022). Enhancement of mechanical behavior of PLA matrix using tamarind and date seed micro fillers. Journal of Natural Fibers, 19(12), 4662-4674 http:// doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2020.1870616

4 Stalin, B., Nagaprasad, N., Vignesh, V., & Ravichandran, M. (2019). Evaluation of mechanical and thermal properties of tamarind seed filler reinforced vinyl ester composites. Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology, 25(s2), E114-E128. http:// doi.org/10.1002/vnl.21701

5 Ramachandran, M., Bansal, S., & Raichurkar, P. (2016). Scrutiny of jute fiber poly-lactic acid (PLA) resin reinforced polymeric composite. Journal of the Textile Association, 76(6), 372-375. Retrieved in 2024, December 7, from https://www. researchgate.net/publication/304246571

6 Mofokeng, J. P., Luyt, A. S., Tábi, T., & Kovács, J. (2012). Comparison of injection moulded, natural fibre-reinforced composites with PP and PLA as matrices. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials, 25(8), 927-948 http:// doi.org/10.1177/0892705711423291

7 Chen, Y., Lin, J., Fei, Y., Wang, H., & Gao, W. (2010). Preparation and characterization of electrospinning PLA/ curcumin composite membranes. Fibers and Polymers, 11(8), 1128-1131 http://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-010-1128-z

8 Aldas, M., Pavon, C., De La Rosa-Ramirez, H., Ferri, J. M., Bertomeu, D., Samper, M. D., & Lopez-Martinez, J. (2021). The impact of biodegradable plastics in the properties of recycled polyethylene terephthalate. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 29(8), 2686-2700 http://doi.org/10.1007/ s10924-021-02073-x

Nagarajan, S., Marimuthu, K., Shanmugam, P., & Chinnasamy, M.

9 Sachin, S. R., Kannan, T. K., & Rajasekar, R. (2020). Effect of wood particulate size on the mechanical properties of PLA biocomposite. Pigment & Resin Technology, 49(6), 465-472 http://doi.org/10.1108/PRT-12-2019-0117

10. Oksman, K., Skrifvars, M., & Selin, J.-F. (2003). Natural fibres as reinforcement in polylactic acid (PLA) composites. Composites Science and Technology, 63(9), 1317-1324 http:// doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00103-9

11 Maheswari, C. U., Reddy, K. O., Muzenda, E., Shukla, M., & Rajulu, A. V. (2013). Mechanical properties and chemical resistance of short tamarind fiber/unsaturated polyester composites: influence of fiber modification and fiber content. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization, 18(7), 520-533 http://doi.org/10.1080/1023666X.2013.816073

12 Jo, M. Y., Ryu, Y. J., Ko, J. H., & Yoon, J.-S. (2012). Effects of compatibilizers on the mechanical properties of ABS/PLA composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 125(S2), E231-E238 http://doi.org/10.1002/app.36732

13 Nuthong, W., Uawongsuwan, P., Pivsa-Art, W., & Hamada, H. (2013). Impact property of flexible epoxy treated natural fiber reinforced PLA composites. Energy Procedia, 34, 839-847. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.820

14 Suryanegara, L., Nakagaito, A. N., & Yano, H. (2010). Thermomechanical properties of microfibrillated cellulose-reinforced partially crystallized PLA composites. Cellulose, 17(4), 771778 http://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-010-9419-5

15. Siregar, J. P., Jaafar, J., Cionita, T., Jie, C. C., Bachtiar, D., Rejab, M. R. M., & Asmara, Y. P. (2019). The effect of maleic anhydride polyethylene on mechanical properties of pineapple leaf fibre reinforced polylactic acid composites. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology, 6(1), 101-112 http://doi.org/10.1007/s40684-019-00018-3

16 Somashekhar, T. M., Naik, P., & Nayak, V., Mallikappa, & Rahul, S. (2018). Study of mechanical properties of coconut shell powder and tamarind shell powder reinforced with epoxy composites. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 376, 012105 http://doi.org/10.1088/1757899X/376/1/012105.

Received: Dec. 07, 2024

Revised: Feb. 28, 2025

Accepted: Apr. 26, 2025

Editor-in-Chief: Sebastião V. Canevarolo

Taynara Alves de Carvalho1 , Alexandra Helena de Barros1 , Rachel Farias Magalhães1 , Milton Faria Diniz2 , Lídia Mattos Silva Murakami1 , Jorge Carlos Narciso Dutra1 , Natália Beck Sanches3,4 and Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra1*

1Divisão de Ciências Fundamentais, Departamento de Química, Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica, São José dos Campos, SP, Brasil

2Divisão de Propulsão, Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia Aeroespacial, Instituto de Aeronáutica e Espaço, São José dos Campos, SP, Brasil

3Centro Universitário Sant’Anna – UNISANT’ANNA, São Paulo, SP, Brasil

4Centro de Tecnologia da Informação – CTI Renato Archer, Campinas, SP, Brasil

*ritalazzarini@yahoo.com.br

Obstract

Using ternary blends is a technological solution to combine the best characteristics of different elastomers. Quantifying rubbers in a blend, in which each content influences the result, is a task complex and usually requires the coupling of techniques. Therefore, it is necessary to develop simple, fast and accurate methodologies for this purpose. This study presents the analysis of polychloroprene, poly-cis-isoprene and polybutadiene (CR/NR/BR) rubber, with the selection of bands A1116 (CR), A2960 (NR) and A738 (BR), by universal attenuated total reflection (UATR) infrared spectroscopy performed on the sample as received. The error found was 2%, with 98 to 99% of the data explained by the methodology. The methodology responds more adequately to CR and BR cis, but has the ability to detect up to 5% of NR and 10% of CR and BR. Acidresistance data are used quantitatively in the determination of BR rubber, satisfactorily confirming the spectral data found.

Keywords: acid-resistance, infrared spectroscopy, quantification, ternary rubber.

Data Ovailability: Research data is only available upon request.

How to cite: Carvalho, T. A., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Diniz, M. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Dutra, J. C. N., Sanches, N. B., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2025). Quantification of elastomers in CR/NR/BR blends. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 35(3), e20250026. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1428.20240130

In recent decades, polymeric materials have achieved a vital position in all branches of science and technology. Rubbers are widely used as vibration absorbers to dissipate vibrational energy[1] and are also of paramount importance for the space sector, in which are used as flexible thermal protections and flexible joints in rocket engines[2], as well as for the aeronautical sector, in which are employed in aircraft tires[3]. Furthermore, this material is also applied in the footwear industry[4], and mainly in the automotive industry, in tires and other artifacts[5]

One type of rubber alone does not have the ability to provide all the desired properties for an elastomer artifact. It is necessary to use the strategy of mixing or blending rubbers, which are formulated to achieve the final properties required according to each project, the process capacity and the desired cost[6]. Such properties can be controlled by changing the morphology of the processing conditions and the composition of the blend[7]

Regarding the morphological characterization of elastomeric blends, Kaliyathan et al.[8] provide a review on blends of various binary and ternary rubbers, with different contents, including, for example, natural poly-cis-isoprene

rubber and butadiene and styrene copolymer (NR/SBR) and ternary rubber containing NR, SBR and polybutadiene (NR/ SBR/ BR). In the case of elastomeric blends, microscopy is an essential tool to understand the morphology, that is, the size, shape and distribution of phases and filler particles in the elastomeric blend. In the review, the authors address studies that use optical microscopy (OM), scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM, TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). The conclusion is that the most suitable microscopy (OM, SEM, TEM or AFM) must be selected depending on the length scale (macro, micro and nano) of the heterogeneity. However, conducting a microscopy study is complex, particularly through TEM analysis, as several factors related to the characteristics of rubbers and microscopes must be considered before conducting an imaging process. Prior knowledge about the sensitivity of rubbers to irradiation, contrast enhancements for analyzing rubbers, the preparation of their surfaces, etc., is very important. Furthermore, the analysis of the morphology of each rubber constituent of the blend is necessary for the adequate interpretation of the image with corresponding physical and mechanical properties.

Carvalho, T. A., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Diniz, M. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Dutra, J. C. N., Sanches, N. B., & Dutra, R. C. L.

As future trend, Kaliyathan et al.[8] cite qualitative spectroscopy of the image obtained microscopically in conjunction with other spectroscopic techniques, such as Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), Raman spectroscopy, photoacoustic spectroscopy, atomic emission spectroscopy, electron spectroscopy and ions, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and mass spectroscopy.

Although there are fewer qualitative infrared (IR) studies than quantitative studies of polymer blends, some research on the latter has been published recently of binary[9-11] and ternary[12,13] elastomeric systems for different technological purposes. However, for ternary rubbers, most of the time, the use of coupling techniques is necessary[14] online or offline, due to the possibility of overlapping thermal events or spectroscopic bands. Therefore, there are gaps in polymer characterization research through techniques and laboratory tests with lower complexity and analysis time, such as in the evaluation of samples as received, which can give rise to the development of new methodologies.

The ternary blend of chloroprene, NR and BR rubbers (CR/NR/BR), for example, stands out in ternary elastomeric systems because it is used for engineering applications in which high performance, chemical resistance and excellent tribological properties are required, i.e., friction, wear and lubrication that take place during contact between solid surfaces in relative movement, however there are few studies in the literature available on this ternary system. However, the qualitative study by Castaño-Rivera et al.[15] can be highlighted.

The qualitative FT-IR analysis of CR/NR/BR is cited by Castaño-Rivera et al.[15], among other techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and rheometric analysis, to study the effect of the type of filler on the mechanical properties of nanocomposites prepared with the ternary rubber, and the correlation with its structure, compatibility and curing properties. Qualitative analysis by FT-IR reflection, specifically by attenuated total reflection (ATR), appears in the study as an important technique to investigate the reinforcement interaction of nanoclays in rubber nanocomposites.

Simpler laboratory tests on rubbers containing one or more elastomers, such as the assessment of resistance to oxidative degradation or the acid-resistance test, in which the sample is subjected to a mixture of concentrated sulfuric and nitric acids at temperatures of 70 and 40 °C, have also been cited in the literature. These tests can indicate the chemical nature of the rubbers used in a formulation[16,17], which is of great practical use in the industry, as this is one of the challenges that the company encounters when it needs to replace rubber parts.

The study by Dutra and Diniz[16] investigated the methodology developed by Mano and Dutra[17] for the case of binary elastomer blends in vulcanized artifacts, including those that show similar IR spectra. The acid-resistance test was useful for differentiating saturated and unsaturated rubbers, thus constituting an alternative methodology for the characterization of rubbers. In the samples analyzed by Dutra and Diniz[16], the test provided a clear indication of the degradability of the polymer chains, even when there is a great predominance of less unsaturated structures in the

mixture. The results indicate that it is possible to detect the component least resistant to the oxidizing mixture when its content is higher than 20% of the elastomeric total. The study can be considered as semi-quantitative for the binary rubbers analyzed.

Magalhães [13] evaluated the acid-resistance test quantitatively at 40 °C by subtraction, validating FT-IR data relating to the evaluation of BR content in the analysis of the ternary rubber NR/SBR/BR. Barros et al.[12] also evaluated quantitatively the BR content in mixture with the ethylene propylene diene monomer copolymer (EPDM/BR), by acid-resistance at 40 °C. The researchers recommend the methodology as an alternative to the FT-IR methodology developed for the binary blend.

The acid-resistance test was initially developed for the qualitative evaluation of saturated and unsaturated rubbers and was later applied in a semi-quantitative way to saturated and/or unsaturated binary blends that presented similar infrared spectra[16,17]. The method was then developed to the quantitative investigation[12,13] of ternary NR/SBR/BR rubbers. This study advances the aforementioned investigations, using the acid-resistance test to evaluate the influence of different BR contents on the degradation initiation time of another ternary rubber: the CR/NR/BR blend.

The development of fast, accurate, qualitative and quantitative methodologies to evaluate the composition of these systems becomes essential due to the commercial importance of elastomeric blends. These methodologies are important for industrial applications, in which the determination of a content range is sufficient for the evaluation of materials, and mainly in the aerospace sector, in which the costs of materials are extremely high and there is the critical factor of safety, which demands the detection of low elastomer content that would not be adequate to the project specifications.

Conventional determination of elastomer content in ternary systems are carried out using complex methodologies, which is time consuming and involve high costs, which often makes them impracticable for the industry. Therefore, there are opportunities for new developments in this area. Reinforcing the importance of the methodology developed in this study, no studies were found in the literature consulted that address the use of non-conventional FT-IR reflection techniques, not even in the most recent reviews[8,18], for determining the content of rubber components in ternary CR/NR/BR on samples as received, with data validation through test sample and acid-resistance tests. Therefore, it is clear that there is a gap in the scientific database on the characterization/quantification of this ternary elastomeric system. The importance of the contribution of this study lies in the development of accurate quantitative non-conventional FT-IR and fast, qualitative and quantitative acid-resistance methodologies for the analysis of CR/NR/BR.

2.1 Materials

CR/NR/BR vulcanized rubber samples, including test sample A1, were prepared and kindly provided by the companies Zanaflex Borrachas and Tenneco Automotive Brazil, with

Quantification of elastomers in CR/NR/BR blends

the following nominal content (wt. %): 10CR/40NR/50BR, 20CR/60NR/20BR, 30CR/5NR/65BR, 40CR/50NR/10BR and 50CR/10NR/40BR, according to the companies’ internal procedures. It should be noted that the BR base elastomer used by Zanaflex has a higher cis C-C content than the one from Tenneco. The CR used in both companies has a cis chemical structure. The contents of the cis structure are not provided by companies due to internal policy.

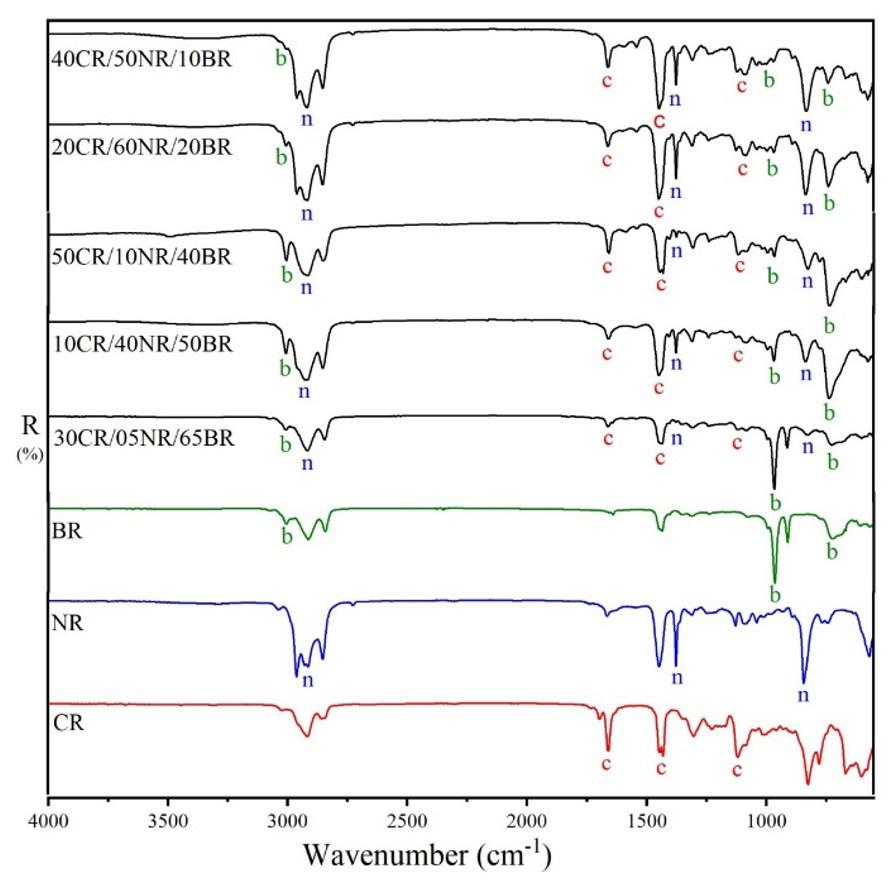

2.2.1 FT-IR reflection (UATR) and acid-resistance test of CR/NR/BR

The conditions for the FT-IR analyses were: PERKINELMER IR spectrometer Frontier, 4000 to 400 cm-1 (mid-infrared MIR), resolution 4 cm-1, gain 1, and 20 scans by universal attenuated total reflection (UATR). Samples were quantitatively analyzed as received. The samples were cut and the internal surface was analyzed, as the investigation of the surface could be interfered by the possible migration of additives from the formulation. The analytical bands used in this methodology were selected according to their variation in height (intensity) in relation to the content of each elastomer, in compliance with the Lambert-Beer law[19], at the following wavenumbers (cm-1), measured by the following baselines (BL): for CR - 1659 (1778 to 1502), 1431 (1502 to 1388) and 1116 (1146 to 927); for NR - 2960 (3110 to 2744), 1376 (1388 to 1341) and 833 (880-790); for BR - 3006 (3110 to 2744), 966 (1146 to 927) and 738 (790 a 624). The assignment[19,20] is: A1659 (cis C=C), A1431 (CH2), A1116 (C-C), A2960 (CH3), A1376 (CH3), A833 (vinylidene), A3006 (C-H), A966 (trans C=C) and A738 (cis C=C). Analyses were performed in quintuplicate. The calibration curves were constructed with the median[21] values of absorbance versus the elastomer content. The accuracy estimation is in accordance to the nonparametric statistical method used for spectroscopic data[21] (Equations 1 to 3) successfully used for IR spectroscopic data in different studies[9-11,22] The methodology error is estimated by the median of the relative error[22] .

Standard deviation:

σ = R K R

where: R = higher absorbance value - lower absorbance value; KR = 0.430 for 5 measurements[21].

Mean standard deviation:

where: n is the number of measurements.

(RD):

where: µ is the median value of absorbance.

The lowest methodology error and the highest linearity of the calibration curve (R2) were the set of results used for

selecting the best analytical band. The acid-resistance test was performed according to the methodology described in a previous study[16]. The test is performed as follows: small fragments of the sample are extracted in acetone and dried in an oven. 5 ml of a mixture 1:1 of concentrated sulfuric acid (density of 1.84 g/cm3) and concentrated nitric acid (density of 1.42 g/cm3) are placed in a test tube, which is then immersed in a water bath at 70 °C. After the contents of the test tube reach the bath temperature (around 5 min), the sample fragments are placed in the test tube and the time at which they begin to degrade is measured with a stopwatch. The degradation can be easily observed when small particles begin to appear on the surface of the sample, then dispersing in the mixture of concentrated acids. The authors[16,17] point out that if the attack is immediate and can’t be measured in minutes, it is necessary to repeat the test in a bath at 40 °C, which is a milder condition and should result in a longer time until deterioration. As immediate degradation of CR/NR/BR occurred at 70 °C, the test was repeated at 40 °C to reduce the aggressiveness of the test conditions and allow measurements. The time measured in the acidresistance test represents the onset time of degradation of the elastomeric material.

The tests were conducted in triplicate. The mean time was used for evaluating the relation between the onset time of degradation and the BR content. The CR/NR/BR sample coded “A1” was analyzed by the same analysis conditions to verify the effectiveness of the developed FT-IR and acidresistance methodologies.

3.1 FT-IR/UATR analysis of the CR/NR/BR blend

The content of each elastomer in the CR/NR/BR blend was determined separately, according to the methodology described in the experiment and discussed in the next topics.

3.1.1 FT-IR/UATR evaluation of analytical bands for determining CR, NR and BR content

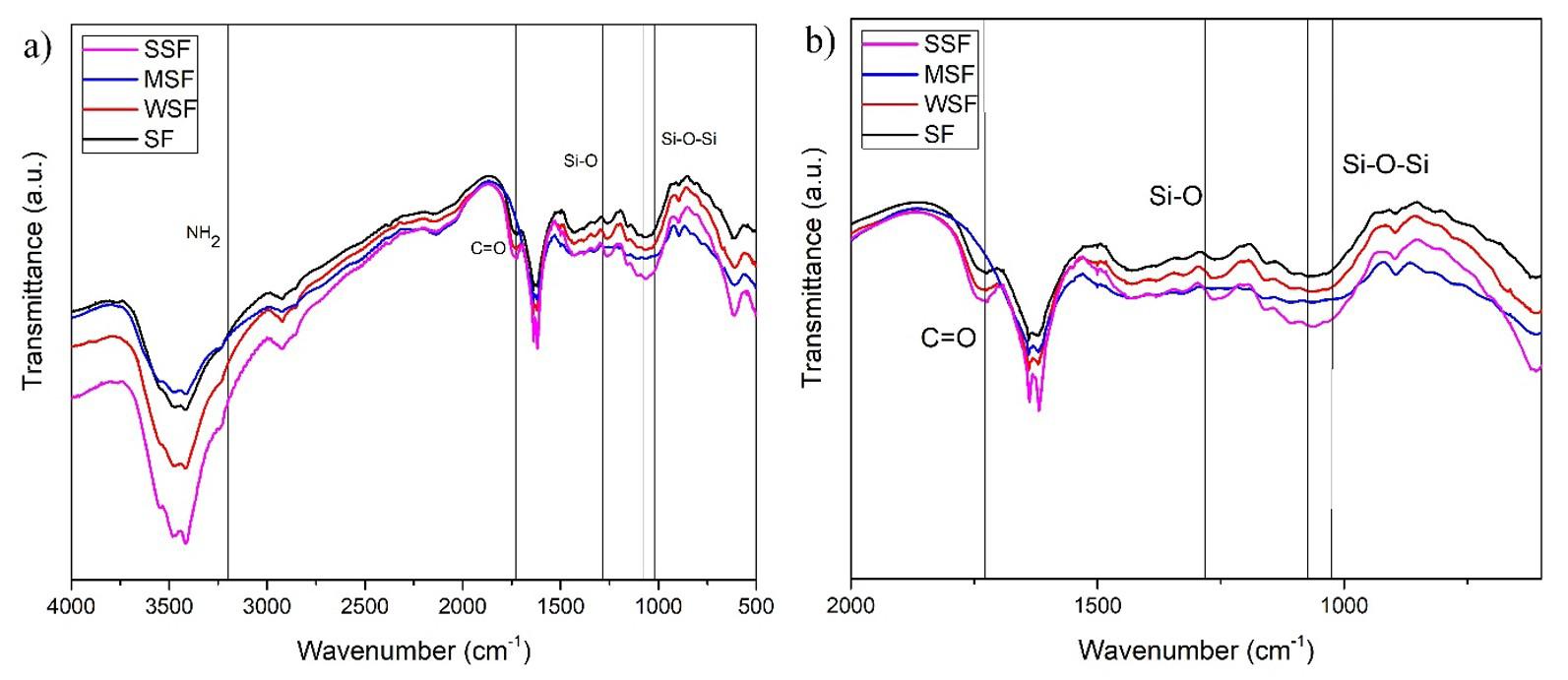

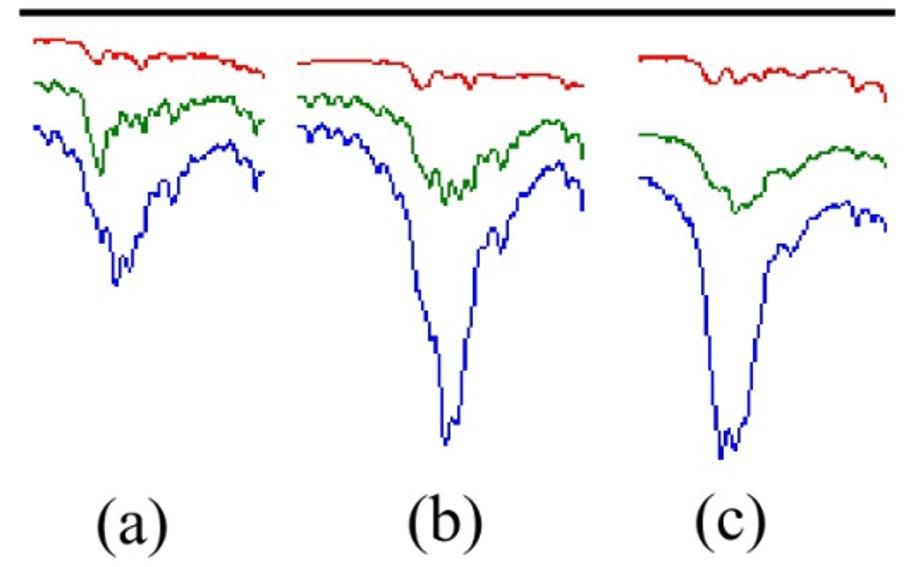

Figure 1 presents the set of UATR spectra (sample as received) of the vulcanized ternary rubber CR/NR/BR, containing different levels, compared to the reference spectra of each elastomer. Spectra were organized in increasing order of BR content to facilitate the visualization of height/intensity variation of their analytical bands, which were chosen and evaluated in accordance with the Lambert-Beer law[19]. In this manner, the bands at 1659, 1431 and 1116 cm-1 were selected for the evaluation of CR determination. The first band evaluated at 1659 cm-1 is assigned to the C=C group[19], and was also considered in the study by Sathasivam et al. [20] on the FT-IR absorptions of cis-1,4-polychloroprene.

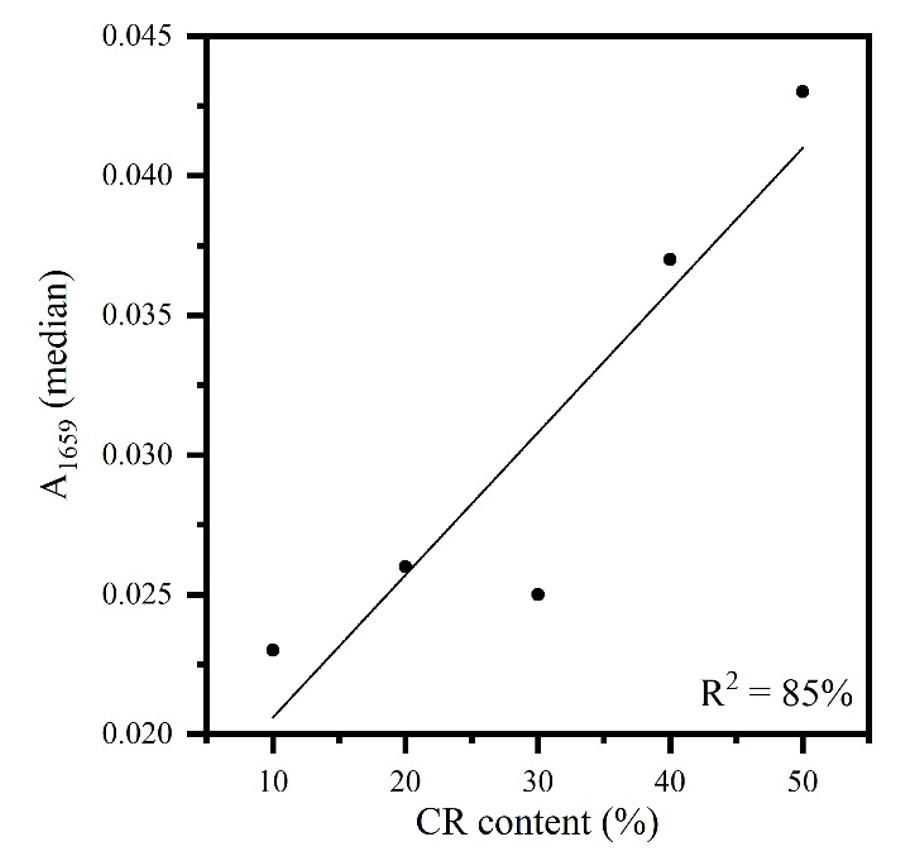

Table 1 shows the FT-IR/UATR data (sample as received) calculated for A1659, for the determination of the CR content in the CR/NR/BR blend using a calibration curve, as well as the errors involved. The samples were organized in increasing order of nominal CR content to facilitate visualization of the increasing in absorbance value. This procedure was also carried out for each band and its corresponding elastomer to construct the other tables in the study.

Carvalho, T. A., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Diniz, M. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Dutra, J. C. N., Sanches, N. B., & Dutra, R. C. L.

Results from Table 1 were plotted in a calibration curve of the analytical band A1659 (median) (CR) versus the CR content (Figure 2). The methodology error was around 4%, in accordance with to Barros et al.[12] and lower than the reported in another study[14] (5%), for another ternary system containing NR and BR (NR/SBR/BR). This methodology error for CR/NR/BR (around 4%) could be considered satisfactory for the industry, because a specification range is routinely adopted for material acceptance. Even though the methodology showed some limitation for the 30% CR content, which can be attributed to this sample lower cis content informed by the suppliers, a tendency in linearity was observed in Figure 2, with 85% of the data explained by the developed methodology (R2).

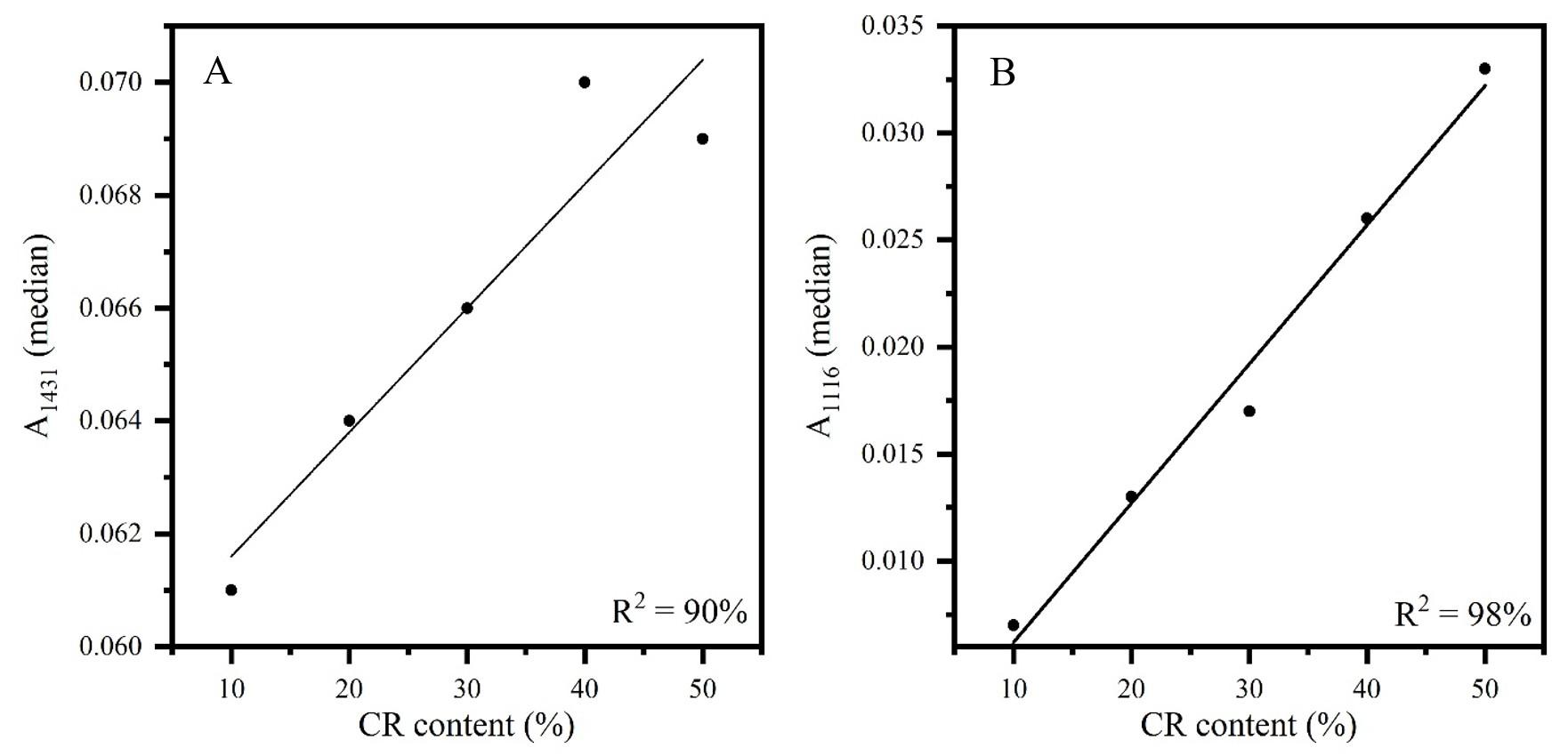

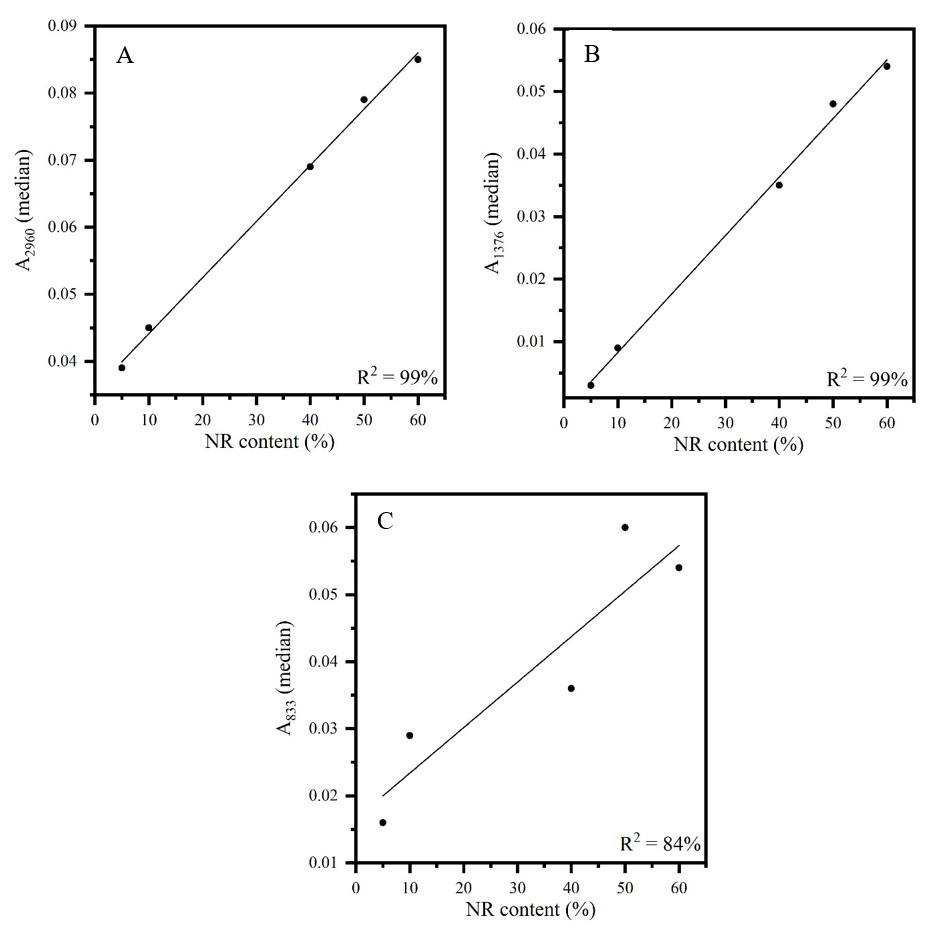

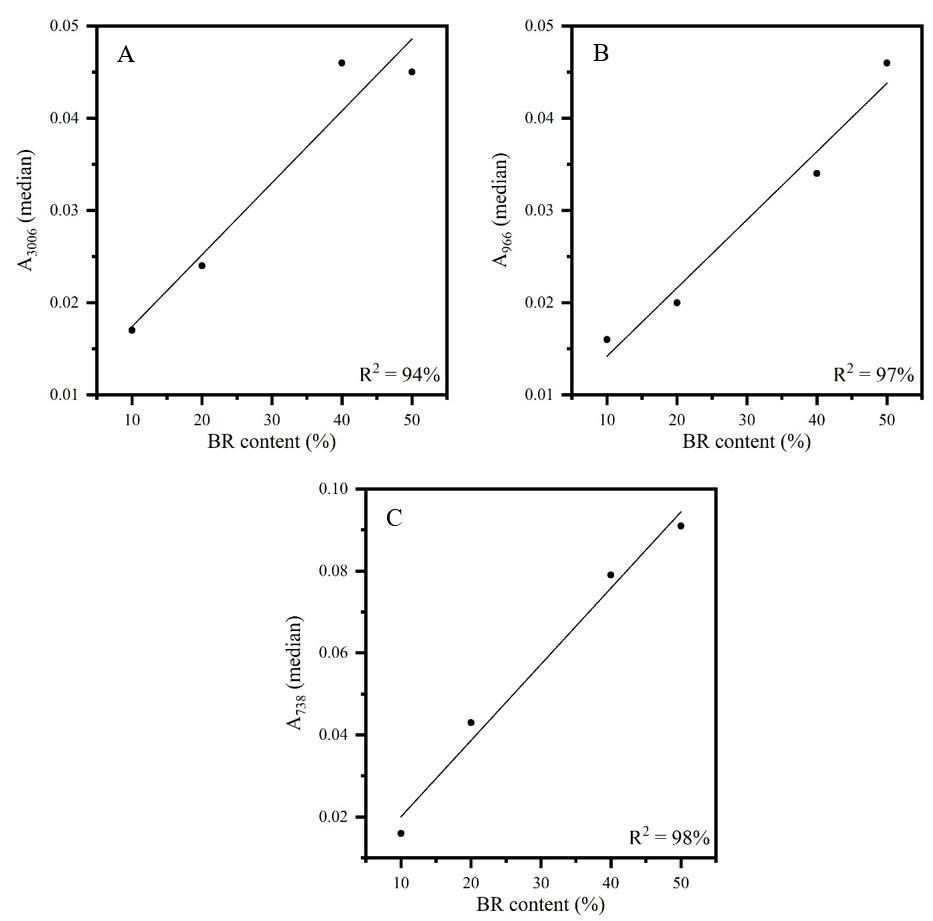

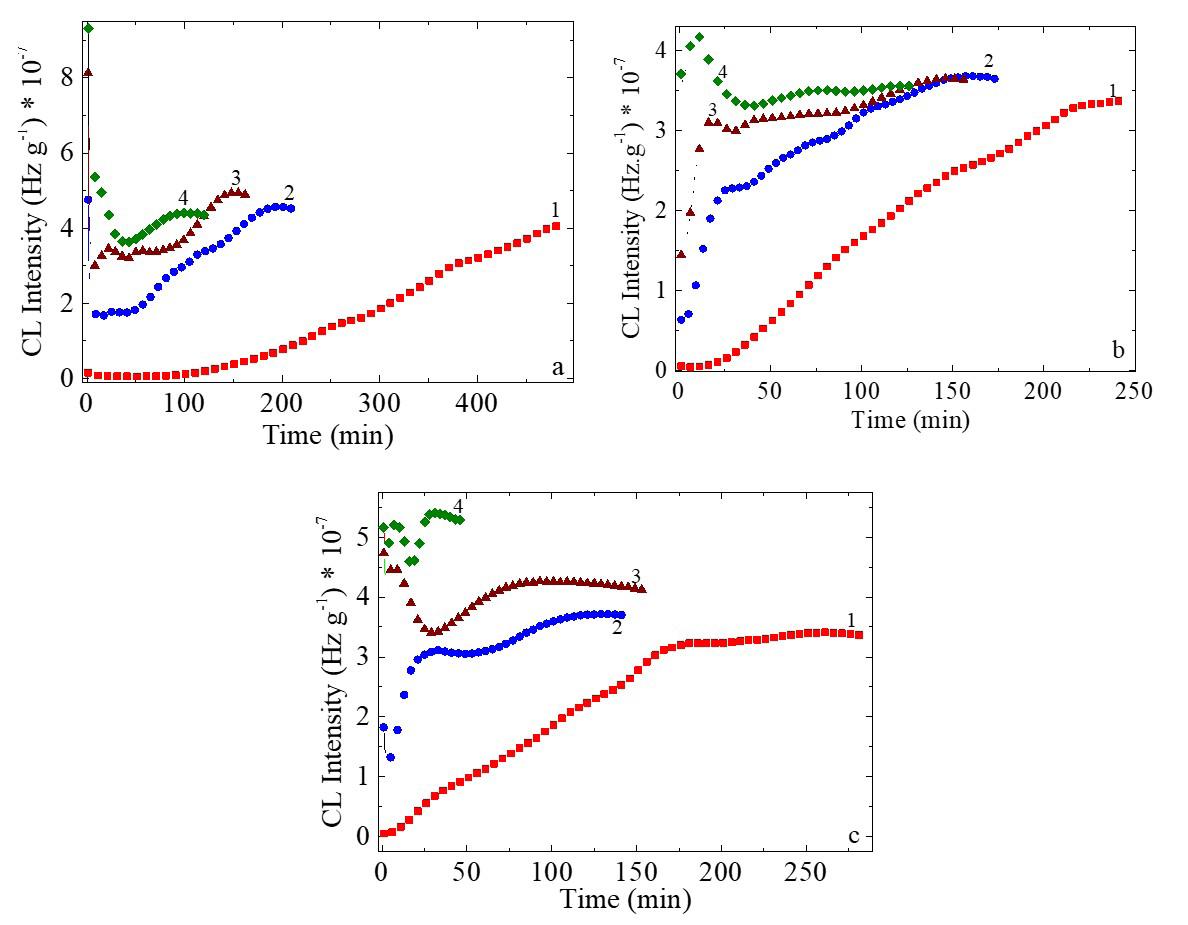

Figures 3 to 5 show the calibration curves of the other bands also evaluated for the determination of elastomer content in the CR/NR/BR blend: A1431 and A1116 (CR content), A2960, A1376 and A833 (NR content), and A3006, A966 and A738 (BR content).

All curves showed adequate linearity, varying between 84 and 99% of data explained by the developed methodologies. It should be noted that the sample 30CR/5NR/65BR was manufactured with a BR rubber with lower cis content and

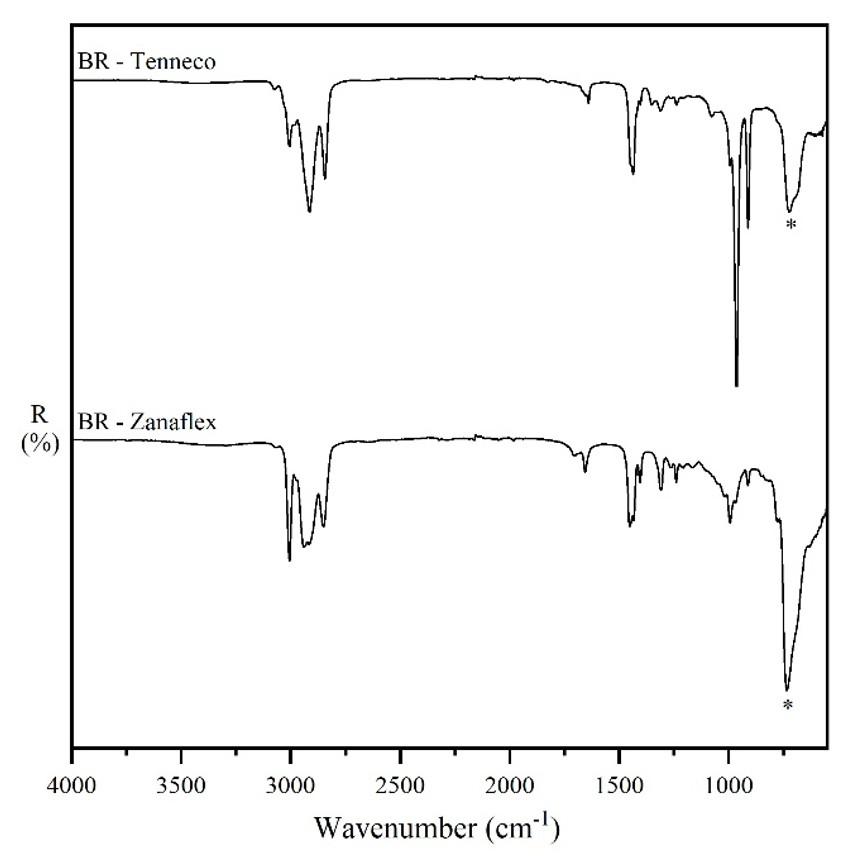

Figure 1. FT-MIR spectra/UATR reflection/ sample as received of the CR/NR/BR samples presented in increasing order of BR content, and of the neat rubbers. The bands evaluated for each elastomer are marked with the letters “c” for CR, “n” for NR, and “b” for BR.

thus was discarded, so only four samples were used to determine the BR content. The lower cis content is confirmed by the difference in the intensity of the band around 740 cm-1 (marked with an asterisk) in the spectra of the two neat BR types (rubber as received from the suppliers) shown in Figure 6. Therefore, the Tenneco sample presented the band around 740 cm-1 with lower intensity (see Figure 1) due to the lower content of C=C cis, despite having a higher content of BR (30CR/5NR/65BR). This occurrence caused a deviation in the measurement of the most characteristic band of cis bonds. On the other hand, it was possible to measure a 5% NR content in CR/NR/BR using all samples of the NR curves, which constitutes a contribution of this research, as it is the minimum acceptable content for a material to be considered as a blend[23]

Regarding the calculations, this study adopted the criterion of showing only one table (i.e. Table 1, already mentioned) of one of the bands chosen for each elastomer and grouping all the results obtained in Table 2 (Equations 4 to 12) for the bands studied for CR, NR and BR, as the calculation mechanism is the same. The results most suitable for determining the aforementioned elastomers in the blend were marked in bold.

Table 2 shows that, in general, the selected bands presented satisfactory results. However, to define the most appropriate analytical band, it is necessary to consider other parameters such as the linearity of the calibration curve, the error of the

Figure 2. Calibration curve of FT-IR/UATR sample as received (A1659) versus CR content in CR/NR/BR.

Table 1. FT-IR/UATR/sample as received (A1659) results for the determination of CR in CR/NR/BR.

*For mean standard deviation values close to zero, a value of 0.001 was assumed, in accordance with the decimal places of the absorbance value.

Quantification of elastomers in CR/NR/BR blends

Figure 3. Calibration curves of FT-IR/UATR sample as received: (A) (A1431) versus CR content in CR/NR/BR; (B) (A1116) versus CR content in CR/NR/BR.

Figure 4. Calibration curves of FT-IR/UATR sample as received: (A) (A2960) versus NR content in CR/NR/BR; (B) (A1376) versus NR content in CR/NR/BR; (C) (A833) versus NR content in CR/NR/BR.

proposed methodology, the possibility of overlapping bands, and the characteristic intensity of the band that facilitates or makes the measurement of low contents difficult[19]

For the determination of CR content in the blend, the highest percentage of data explained by the methodology was mandatory for indicating the band at 1116 cm-1 as the

T. A., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Diniz, M. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Dutra, J. C. N., Sanches, N. B., & Dutra, R. C. L.

curves of FT-IR/UATR sample as received: (A) (A3006) versus BR content in CR/NR/BR; (B) (A966) versus BR content in CR/NR/BR; (C) (A738) versus BR content in CR/NR/BR.

most appropriate, even though the error was around 6%. Errors of this order of magnitude are typically found in quantitative methodologies by reflection[12] or even through coupling techniques[14] for ternary rubbers.

In the case of NR, both the error and the percentage of data explained by the methodology indicated the band at 2960 cm-1 as the best option. This band is characteristic of CH3 [19] and has an intensity suitable for measuring low contents, as evidenced by the NR determination of 5% in the ternary blend. The band at 1376 cm-1, also characteristic of CH3 [19], showed adequate results but with lower intensity, which can yield higher errors, as observed.

For the BR determination, the band that showed the most appropriate result in terms of methodology error and linearity was found at 738 cm-1, which is characteristic of C=C cis[19,20]

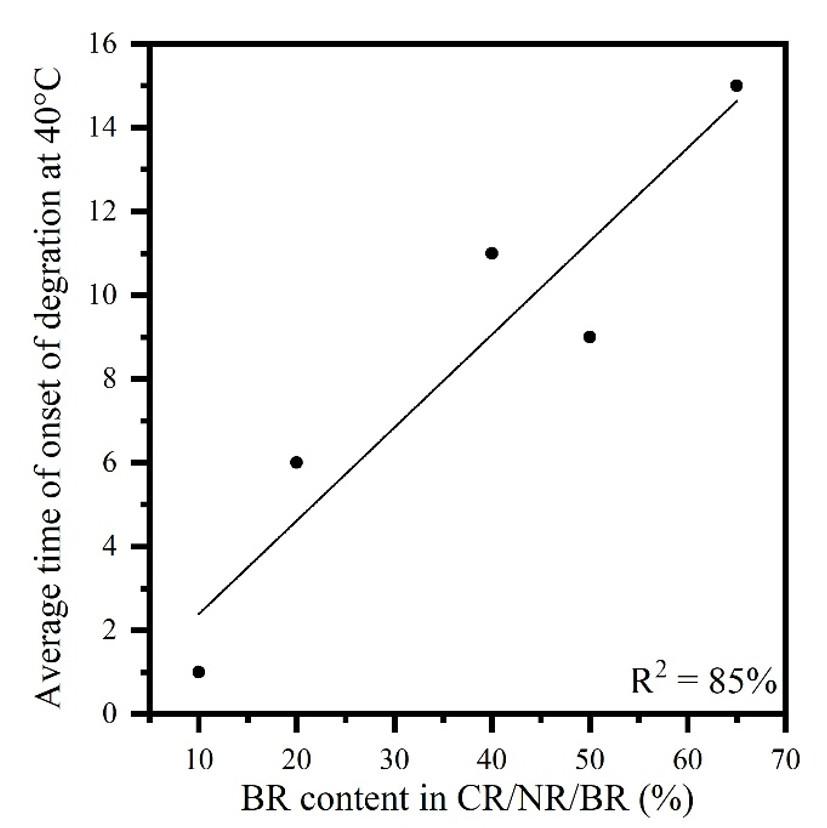

3.2 Acid-resistance evaluation of the BR content

In addition to the qualitative FT-IR/UATR analysis of the sample as received, which confirmed the characteristic

6. FT-IR/UATR spectra/sample as received of BR Tenneco and BR Zanaflex.

bands of CR/NR/BR (Figure 1 already shown), and the quantitative analysis that determined the levels of each elastomer, the acid-resistance test[16,17] was conducted to verify the quantitative relation between the increase in BR content and the degradation onset time of the CR/NR/BR blend. The test was carried out focusing on BR rubber because among the three elastomers, BR is the one with the longest degradation start time at a given temperature[16] .

According to Dutra and Diniz[16], unsaturated NR, CR, and BR rubbers degrade within ≤ 1 minute at 70 °C. Therefore, the CR/NR/BR blend is expected to have a quick degradation at 70 °C, making it impossible to establish any relation between the BR content and the degradation time. Because of this occurrence, the test was conducted at 40 °C (Table 3).

The longer time required at 40 °C to start the degradation of each rubber in the blend permits a better individual visualization. Furthermore, according to the literature[16,17], the elastomers combined in the blend have different degradation onset time at 40 °C. NR and CR degrade in less than 3 minutes, while BR degrades between 10 and 30 minutes. Therefore, the expected behavior for the increase in BR content in the CR/NR/BR blend is an increase in the degradation start time for the blend, which is observed in the linear trend of Figure 7. Some deviation can be attributed to the different characteristics of some elastomers used from different suppliers, such as BR provided with higher content of trans or cis C=C vinyl. However, the results show that the presence of BR in CR/NR/BR is more noticeable from 20% onwards, which confirms what was observed by Dutra and Diniz[16] for binary blends. Due to the longer degradation initiation time (6 minutes) for BR compared to that observed for NR and CR (around 3 minutes) at 40 °C, BR, despite also being unsaturated, is the most resistant rubber to the oxidizing mixture in this analyzed system.

It was observed a correlation (Equation 13) with an adequate linearity (R2 = 85%) between the data obtained through the acid-resistance tests and the BR content in the sample.

0.22420.3030 =+= yxy (13)

where: y is the degradation onset average time at 40 °C and x is the BR content in CR/NR/BR.

methodologies developed

To evaluate the effectiveness of the methodologies developed, the UATR and acid-resistance was performed on test sample A1 and results were presented in Tables 4 and 5. In the FT-IR analysis, the bands 1116 cm-1 for CR, 2960 cm-1 for NR and 738 cm-1 for BR were analyzed, which were, according to the methodology developed, the most suitable for determining the levels of these elastomers in the CR/NR/BR blend. The corresponding equations previously shown were used (Equations 6, 7 and 12). For the calculated values, whole numbers were considered for comparison with the nominal values.

The results of the FT-IR/UATR/sample methodology as received can be considered with adequate precision, as the methodology error is 1.80% (median of the 3 relative errors), considering the 3 bands selected (Table 2). Furthermore, considering the technological aspect[24] of rubber industries, which use specification ranges for the acceptance of their products, the calculated accuracy meets the requirements.

Table 2. Comparison of FT-IR UATR data (as received) for each CR/NR/BR band analyzed, including methodological errors and data from the respective calibration curves.

in CR/ NR/BR Band

median absorbance value of the analytical band and x= elastomer content.

Carvalho, T. A., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Diniz, M. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Dutra, J. C. N., Sanches, N. B., & Dutra, R. C. L.

Table 3. Results of acid-resistance (40 °C) for the CR/NR/BR blend.

40CR/50NR/10BR

50CR/10NR/40BR

10CR/40NR/50BR 10/9/9 9

30CR/5/NR/65BR 14/15/16 15

Table 4. FT-IR/UATR data/sample as received for test sample A1 from CR/NR/BR.

Table 5. Acid-resistance data (40 °C) for test sample A1 of CR/NR/BR.

The BR content calculated for sample A1 with Equation 13 (16%) in the acid-resistance test can also be considered satisfactory from an industrial point of view, even considering its lower precision, as long as the nominal BR content is not higher than 20%. In this condition, results from the acid-resistance test validate the FT-IR data, and are able to distinguish the content in which the influence of this elastomer on the beginning of degradation in the blend start to be noted[16]

The objective of this study was to develop a simple, fast and accurate methodology for quantifying the elastomer content in the CR/NR/BR blend. The purpose was achieved, which contributes to the state of the art of research in the determination of elastomer contents in ternary elastomeric systems. It is noteworthy that the proposed methodology is the FT-IR/UATR analysis with the sample as received, that is, without sample preparation. Therefore, time spent is reduced and accurate values are found without major complexities, especially for samples containing CR and BR cis. The methodology can also be applied to different CR/ NR/BR blends, even detecting the lowest possible content in a blend (5%). Results were validated through a test sample, both for the FT-IR analysis and for the acid resistance test, which is a simple and quick laboratory examination. The applicability of the acid resistance test was expanded in this study for the determination of BR in the CR/NR/BR blend.

5. Author’s Contribution

• Conceptualization –Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Natália Beck Sanches; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Data curation – NA.

• Formal analysis – NA.

• Funding acquisition - Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Investigation – Milton Faria Diniz; Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Alexandra Helena de Barros; Rachel Farias Magalhães.

• Methodology –Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Alexandra Helena de Barros; Rachel Farias Magalhães; Milton Faria Diniz; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Project administration – Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Resources – Lídia Mattos Silva Murakami.

• Software – NA.

• Supervision – Natália Beck Sanches; Jorge Carlos Narciso Dutra; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra

• Validation –Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Alexandra Helena de Barros; Rachel Farias Magalhães; Milton Faria Diniz; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Visualization – Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Natália Beck Sanches; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Writing – original draft – Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

• Writing – review & editing – Taynara Alves de Carvalho; Alexandra Helena de Barros; Rachel Farias Magalhães; Natália Beck Sanches; Rita de Cássia Lazzarini Dutra.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ) - Finance Code 301626/2022-7.

1 Zeng, Z., Qahtan, A. A. S., Hu, G., Xu, R., & Shuaibu, A. A. (2023). Comparative experimental investigation of the vibration mitigation characteristics of ballasted track using the rubber composite sleeper and concrete sleeper under

various interaction forces. Engineering Structures, 275(Part A), 115243 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115243

2. Wang, Y., Li, J., Wan, L., Wang, L., & Li, K. (2023). A lightweight rubber foaming insulation reinforced by carbon nanotubes and carbon fibers for solid rocket motors. Acta Astronautica, 208, 270-280 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2023.04.019

3 Jiang, B., & Wang, H. (2023). An integrated analytical model for friction characteristics of aircraft tire on wet runway pavement. Tribology International, 185, 108501 http://doi. org/10.1016/j.triboint.2023.108501

4 Anggoro, P. W., Bawono, B., Setyohadi, D. B., Ratnasari, L., Fergiawan, P. K., Tauviqirrahman, M., Jamari, J., & Bayuseno, A. P. (2023). Optimisation of the machining time required by insole orthotic shoes for patients with clubfoot using the Taguchi and response surface methodology approach. Heliyon, 9(6), e16860 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16860 PMid:37484398.

5 Utrera-Barrios, S., Verdejo, R., López-Manchado, M. A., & Hernández Santana, M. (2023). Self-Healing elastomers: a sustainable solution for automotive applications. European Polymer Journal, 190, 112023 http://doi.org/10.1016/j. eurpolymj.2023.112023

6 Yoon, B., Kim, J. Y., Hong, U., Oh, M. K., Kim, M., Han, S. B., Nam, J.-D., & Suhr, J. (2020). Dynamic viscoelasticity of silica-filled styrene-butadiene rubber/polybutadiene rubber (SBR/ BR) elastomer composites. Composites. Part B, Engineering, 187, 107865. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.107865.

7 Nawawi, M. A., Har, S. L., & Han, C. C. (2012). Miscibility of polymer blends comprising poly (ethylene oxide)-epoxidized natural rubber. International Journal of Chemical Engineering and Applications, 3(6), 410-412 http://doi.org/10.7763/ IJCEA.2012.V3.230.

8 Kaliyathan, A. V., Varghese, K. M., Nair, A. S., & Thomas, S. (2020). Rubber-rubber blends: a critical review. Progress in Rubber, Plastics and Recycling Technology, 36(3), 196-242 http://doi.org/10.1177/1477760619895002

9 Passero, A., Ferreira, K. M., Diniz, M. F., Sanches, N. B., Amado, J. C. Q., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2024). Quantification of natural rubber blends by reflection/reflectance infrared and confocal Raman spectroscopy: a comparison of statistical methods. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 96(3), e20230387. http:// doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202420230387 PMid:38865508.

10 Barros, A. H., Murakami, L. M. S., Magalhães, R. F., Takematsu, M. M., Diniz, M. F., Sanches, N. B., Dutra, J. C. N., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2023). Infrared quantification of binary rubber blends with overlapping bands. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 95(1), e20220289 http://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202320220289

11 Rigoli, P. S., Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Carrara, A. E., Dutra, J. C. N., Mattos, E. C., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2021). Determination of polychloroprene content in rubber blend containing ethylene propylene diene monomer by infrared techniques. Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management, 13, e0821 http://doi.org/10.1590/jatm.v13.1197

12 Barros, A. H., Magalhães, R. F., Murakami, L. M. S., Diniz, M. F., Sanches, N. B., Carvalho, T. A., Dutra, J. C. N., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2025). Determination of elastomer content in NR/SBR/BR blends. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 35(2), e20250023

13 Magalhães, R. F. (2023). Avaliação de técnicas FT-IR de transmissão, reflexão e refletância para a caracterização/ quantificação de polímeros e carga de diferentes setores industriais (Tese de doutorado). Instituto Tecnológico Aeronáutica, São José dos Campos

14. Lee, Y. S., Lee, W.-K., Cho, S.-G., Kim, I., & Ha, C.-S. (2007). Quantitative analysis of unknown compositions in ternary polymer blends: a model study on NR/SBR/BR system. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 78(1), 85-94 http://doi. org/10.1016/j.jaap.2006.05.001

15 Castaño-Rivera, P., Calle-Holguín, I., Castaño, J., CabreraBarjas, G., Galvez-Garrido, K., & Troncoso-Ortega, E. (2021). Enhancement of chloroprene/natural/butadiene rubber nanocomposite properties using organoclays and their combination with carbon black as fillers. Polymers, 13(7), 1085 http://doi.org/10.3390/polym13071085. PMid:33805582.

16 Dutra, R. C. L., & Diniz, M. F. (1993). Resistência à degradação oxidativa e comportamento aos solventes como indicadores da composição de sistemas elastoméricos vulcanizados mistos. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 3(3), 25-28. Retrieved in 2024, December 23, from https://revistapolimeros.org.br/ar ticle/588371347f8c9d0a0c8b47a4/pdf/polimeros-3-3-25.pdf

17 Mano, E. B., & Dutra, R. C. L. (1988). Identificação de borrachas natural e sintéticas cruas ou vulcanizadas. Revista de Química Industrial, 56(663), 24-26. Retrieved in 2024, December 23, from https://www.abq.org.br/rqi/edicoes_1989/1988/RQI-663.pdf

18 Workman, J., Jr. (2024). A review of the latest research applications using FT-IR spectroscopy. Spectroscopy Supplements, 39(s8), 22-28 http://doi.org/10.56530/spectroscopy.ak9689m8

19 Smith, A. L. (1979). Applied infrared spectroscopy: fundamentals techniques and analytical problem-solving New York: John Wiley & Sons

20 Sathasivam, K., Haris, M. R. H. M., & Mohan, S. (2010). Vibration spectroscopic studies on cis-1,4-polychloroprene. International Journal of Chemtech Research, 2(3), 1780-1785.

21 Hórak, M., & Vítek, A. (1978). Interpretation and processing of vibrational spectra. New York: John Wiley & Sons

22 Dutra, R. C. L., & Soares, B. G. (1998). Determination of the vinyl mercaptoacetate content in poly (ethylene-co-vinyl acetate-co-vinyl mercaptoacetate)(EVASH) by TGA analysis and FTIR spectroscopy. Polymer Bulletin, 41(1), 61-67 http:// doi.org/10.1007/s002890050333

23. Simielli, E. R. (1993). Principais características das blendas poliméricas fabricadas no Brasil. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 3(1), 45-49. Retrieved in 2024, December 23, from https://www.revistapolimeros.org.br/article/58837133 7f8c9d0a0c8b479e/pdf/polimeros-3-1-45.pdf

24 Mello, T. S. D., Diniz, M. F., & Dutra, R. C. L. (2018). UATR and NIRA evaluation in the quantification of ATBC in NC blends. Polímeros: Ciência e Tecnologia, 28(3), 239-245 http://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1428.16816

Received: Dec. 23, 2024

Revised: Apr. 23, 2025

Accepted: Apr. 27, 2025

Associate Editor: Artur J. M. Valente

João Gabriel Machado de Avellar1* , Gisely Alves da Silva2 ,

Renan Rogério Oliveira de Souza1 , Mariana Alves Henrique1 , Jorge Vinicius Fernandes Lima Cavalcanti2 , Yeda Medeiros Bastos de Almeida1,2 , Maria de Los Angeles Perez Fernandez2 and Glória Maria Vinhas1,2

1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência de Materiais – PGMtr, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco – UFPE, Recife, PE, Brasil

2Departmento de Engenharia Química – DEQ, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco – UFPE, Recife, PE, Brasil

*joao.avellar@ufpe.br

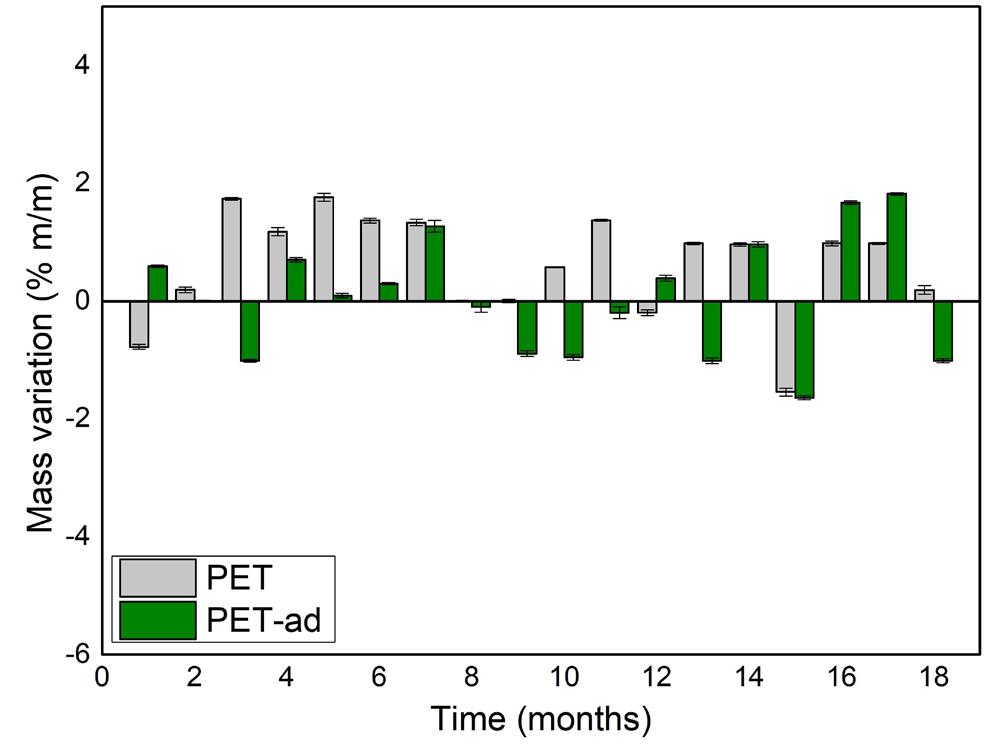

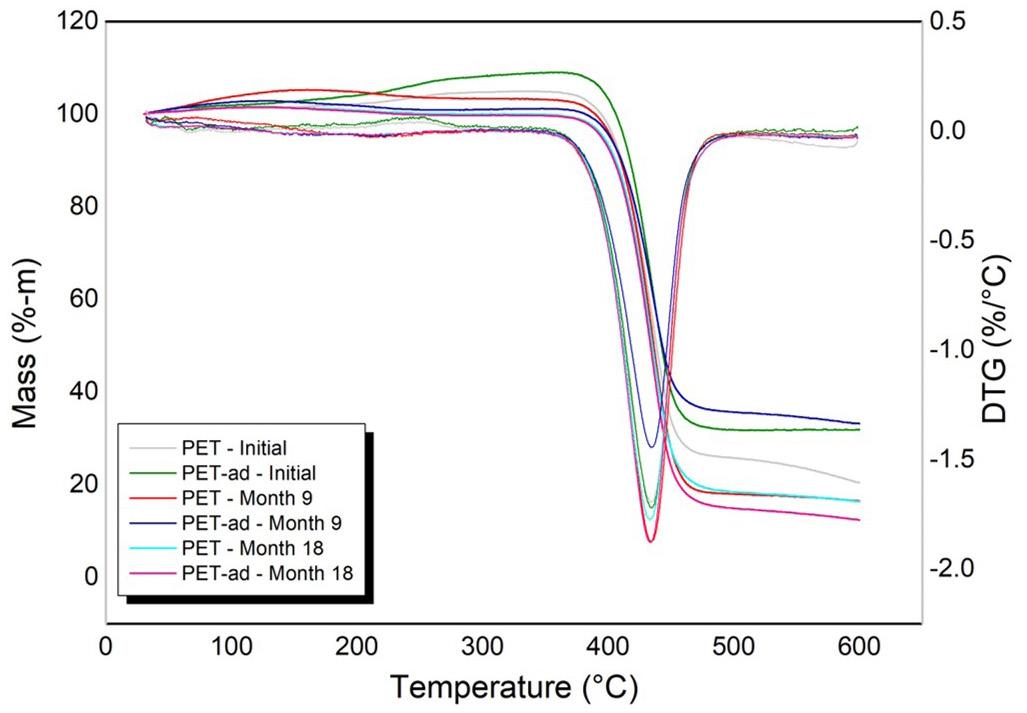

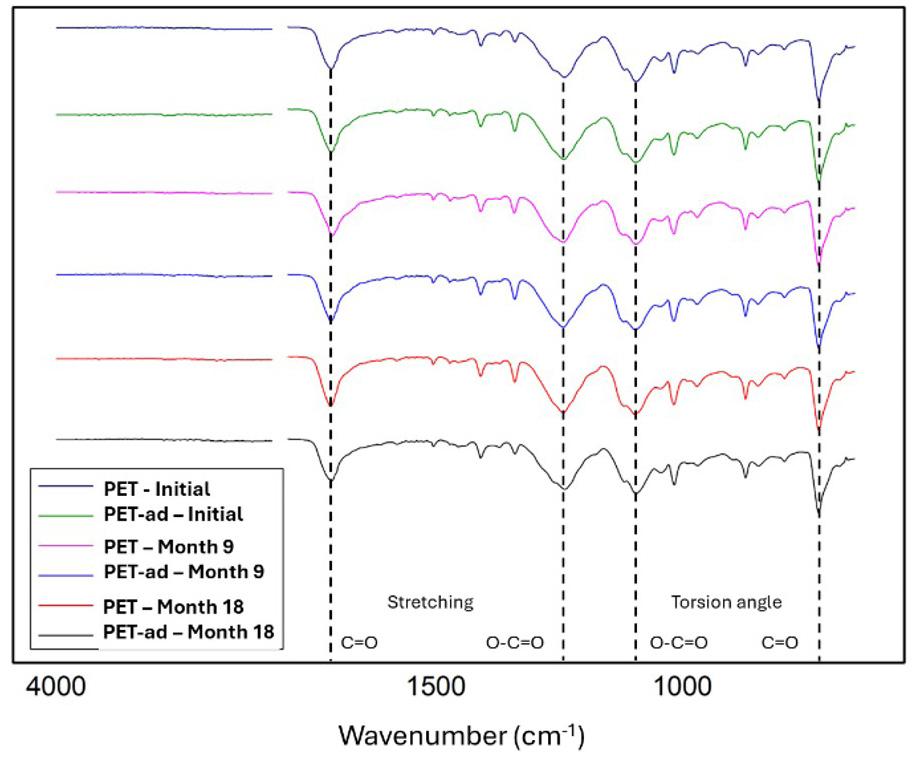

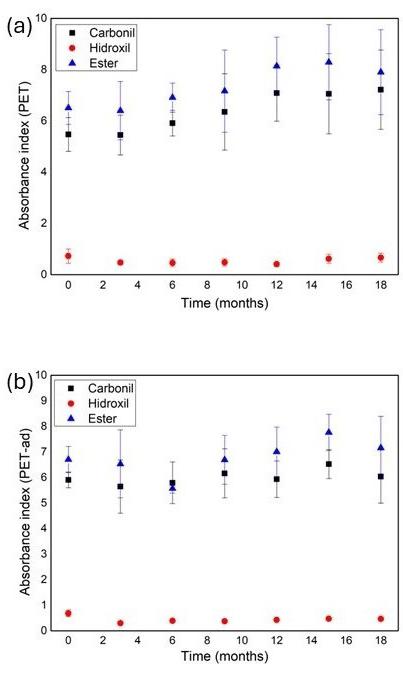

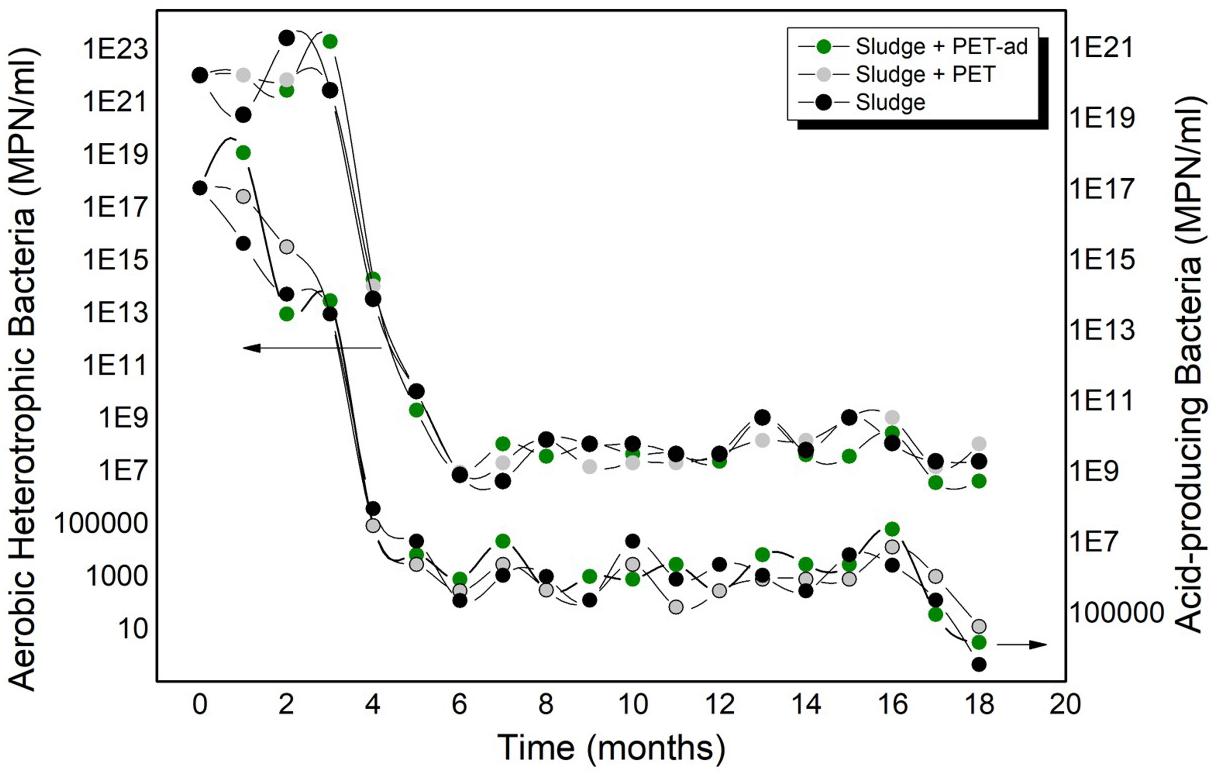

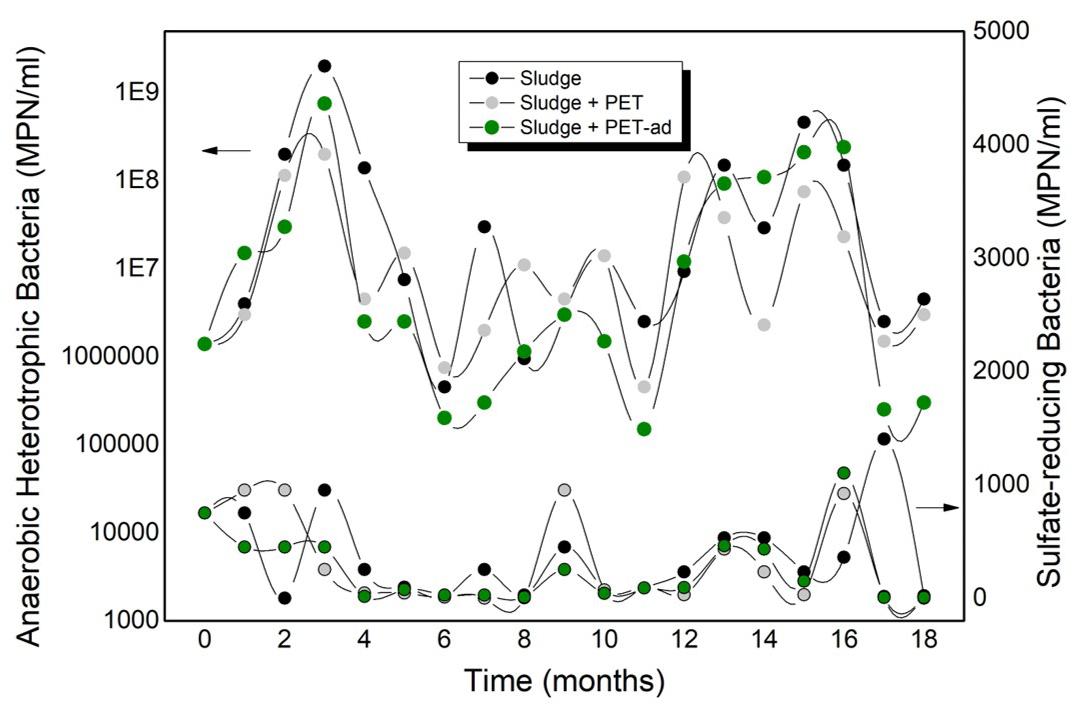

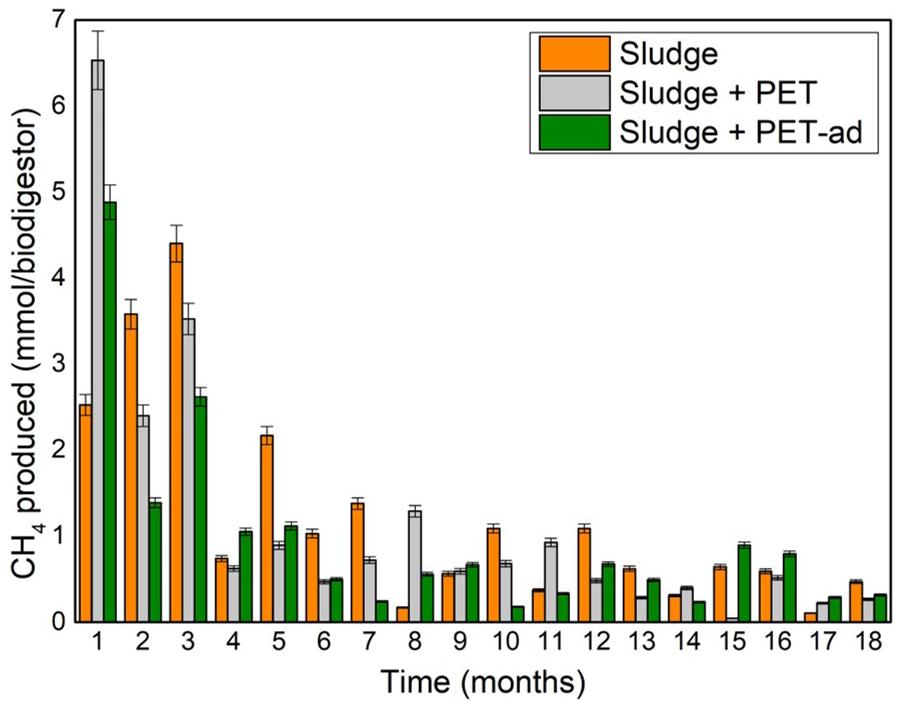

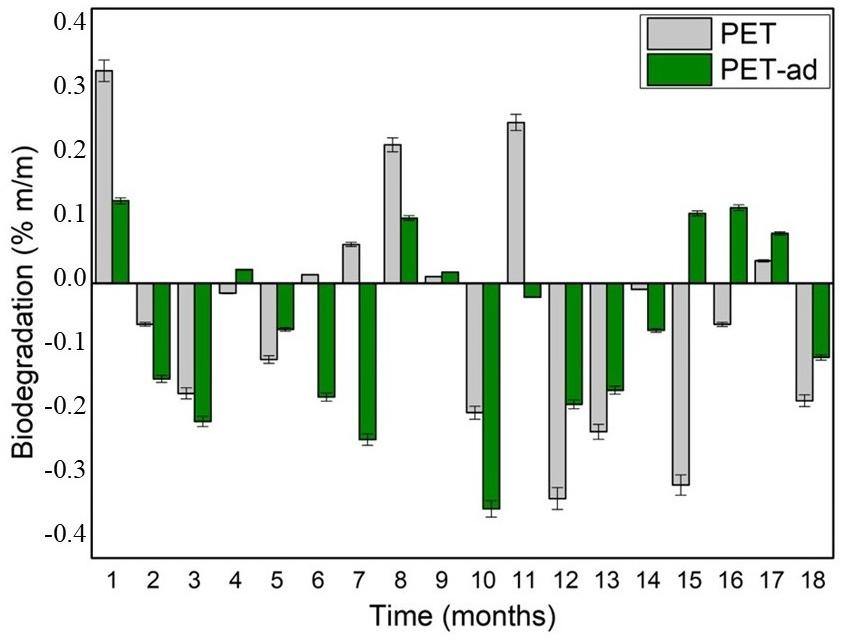

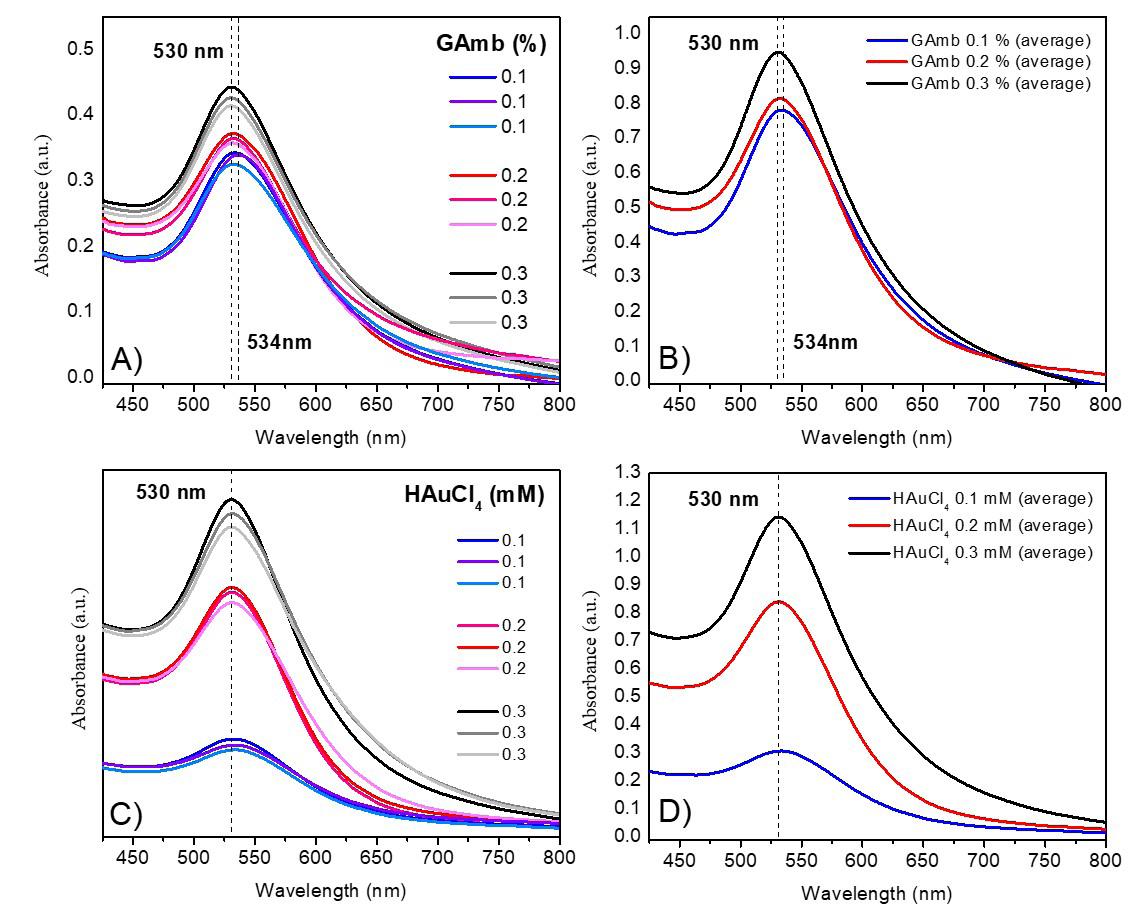

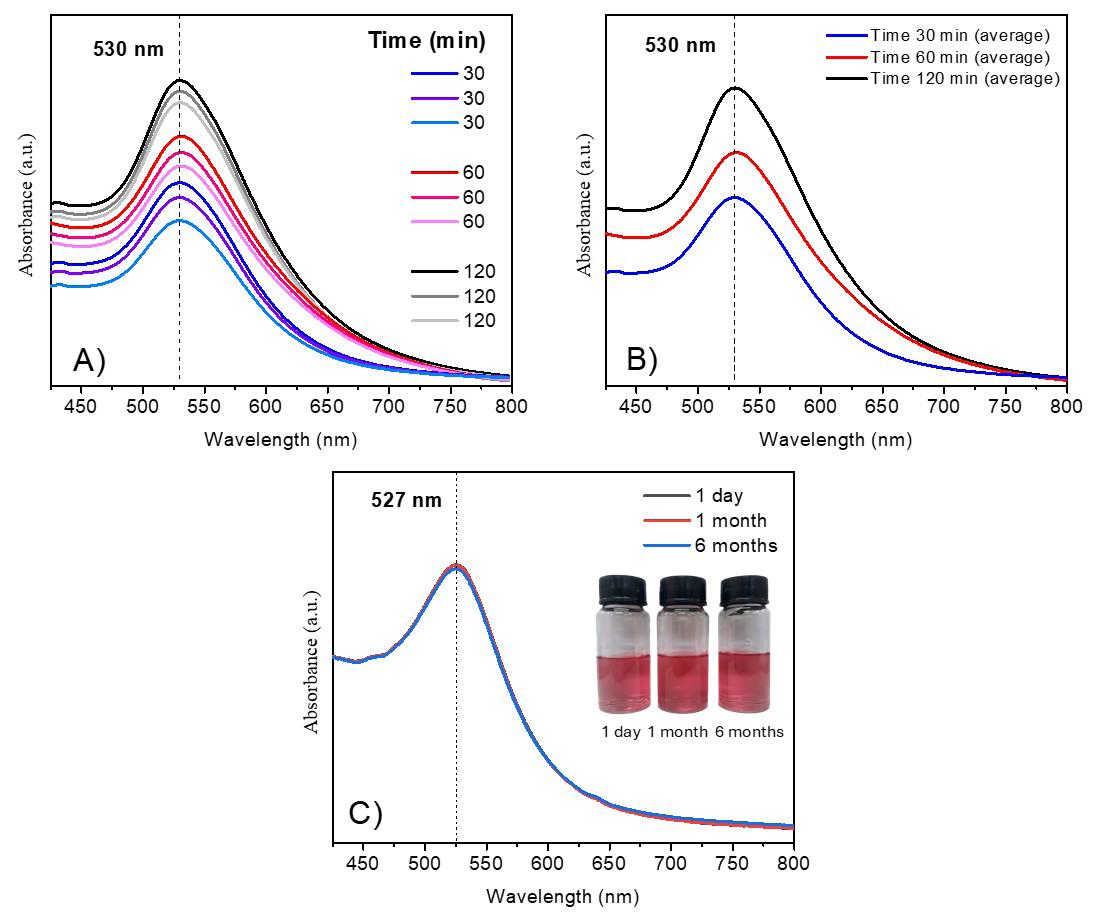

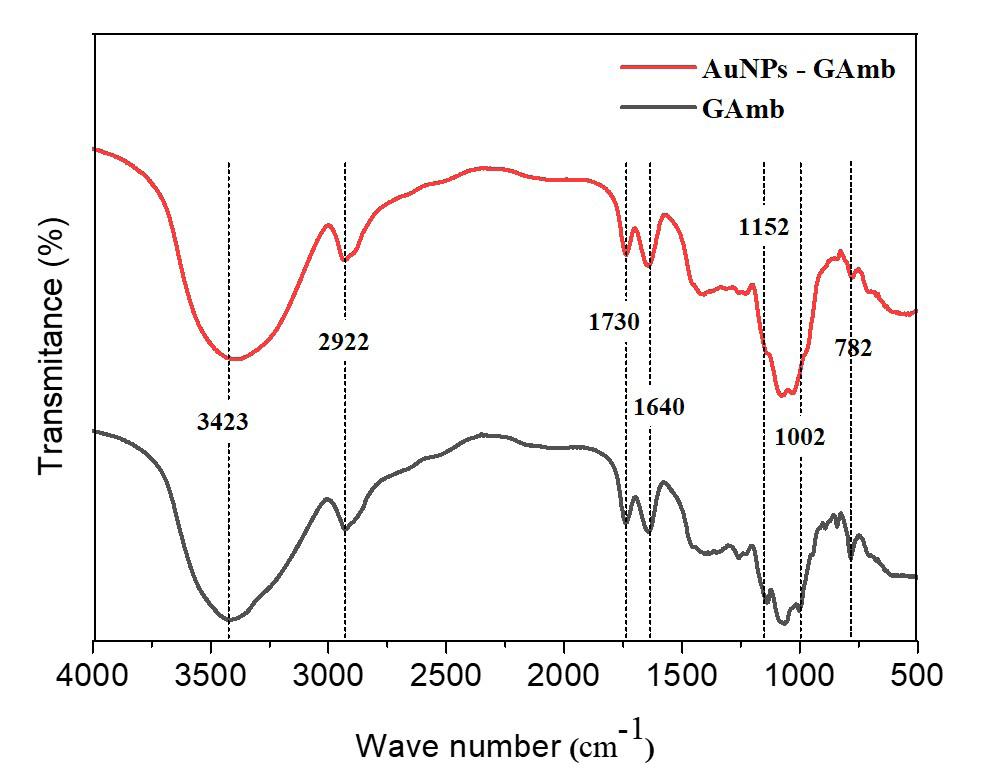

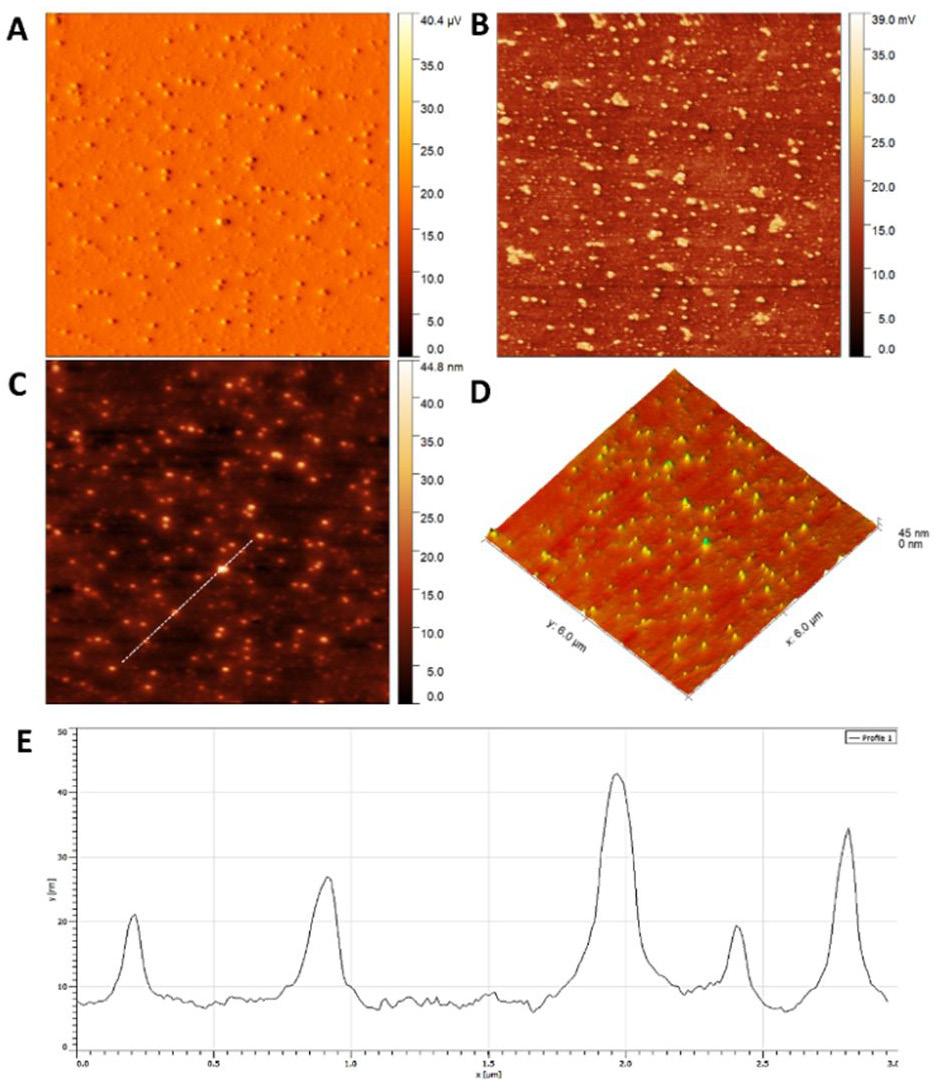

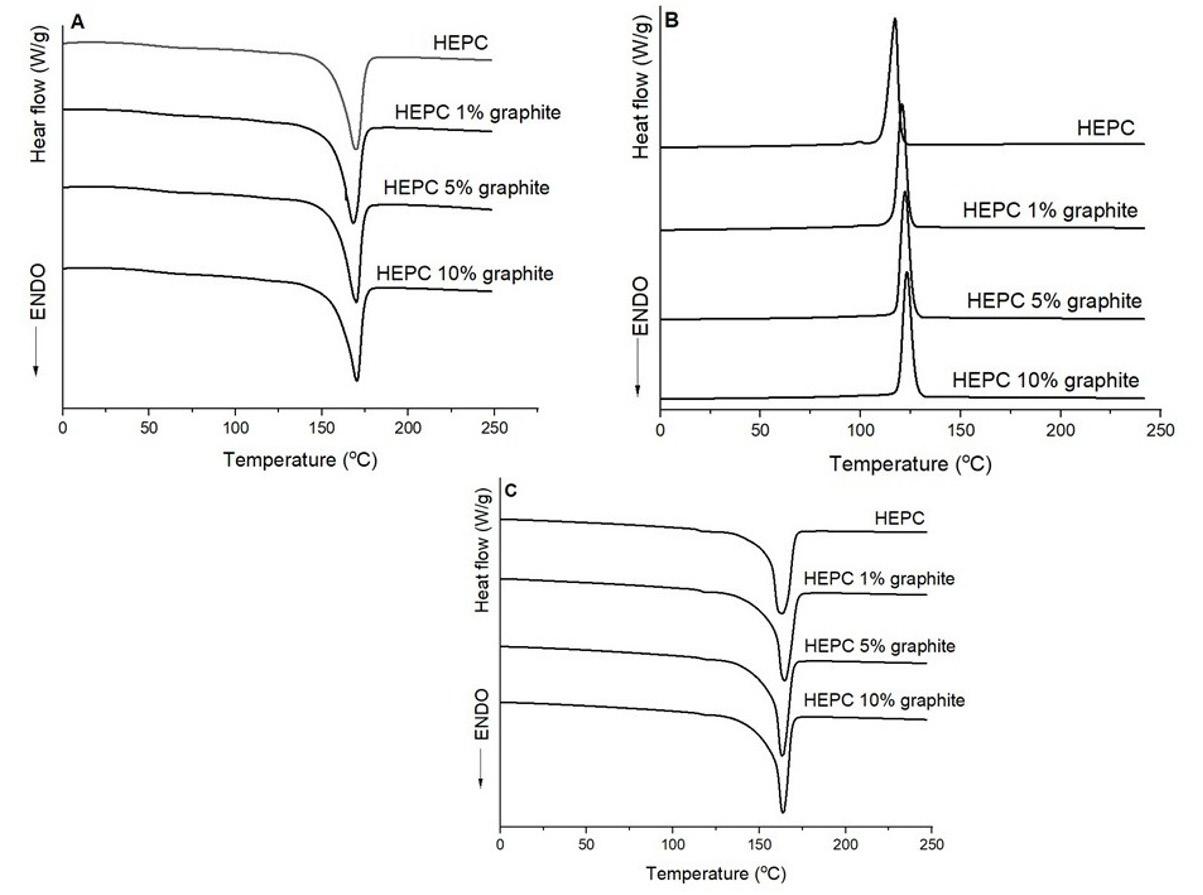

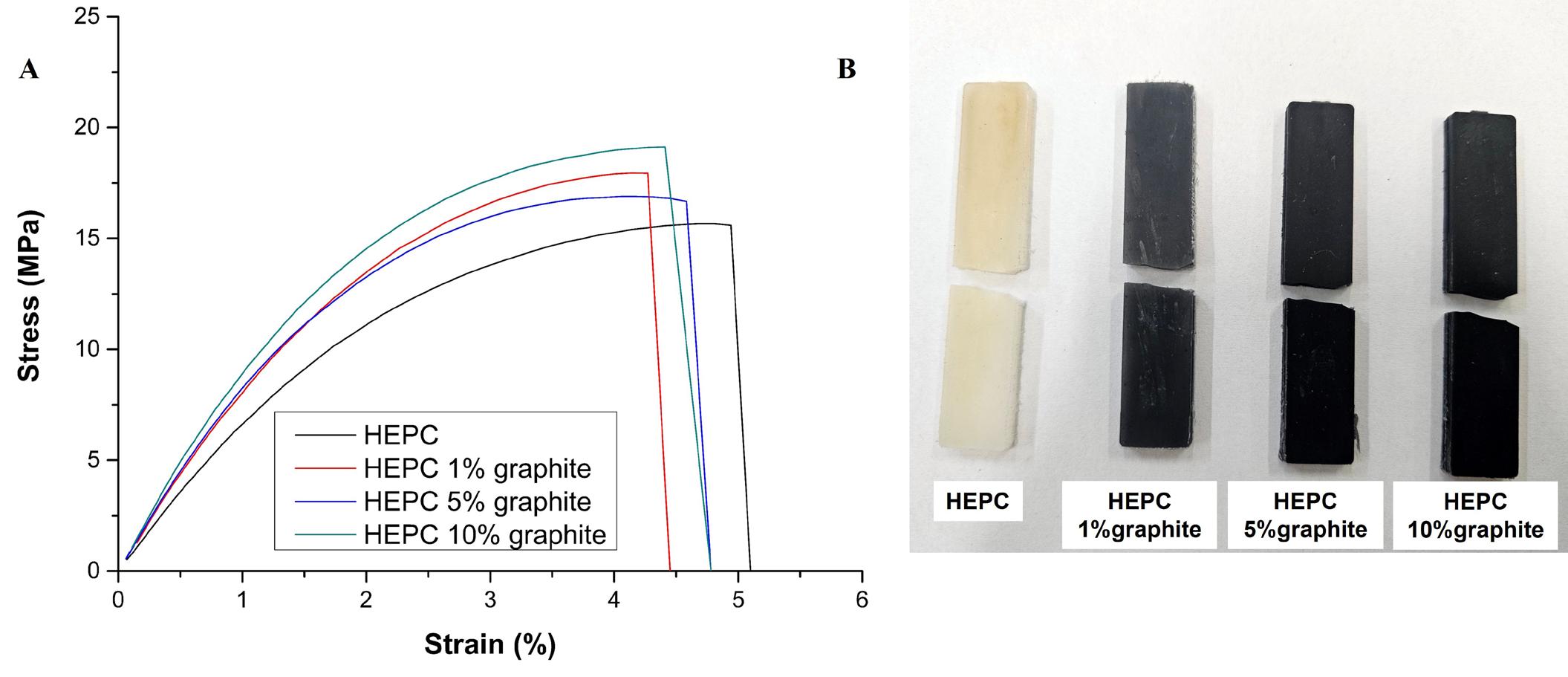

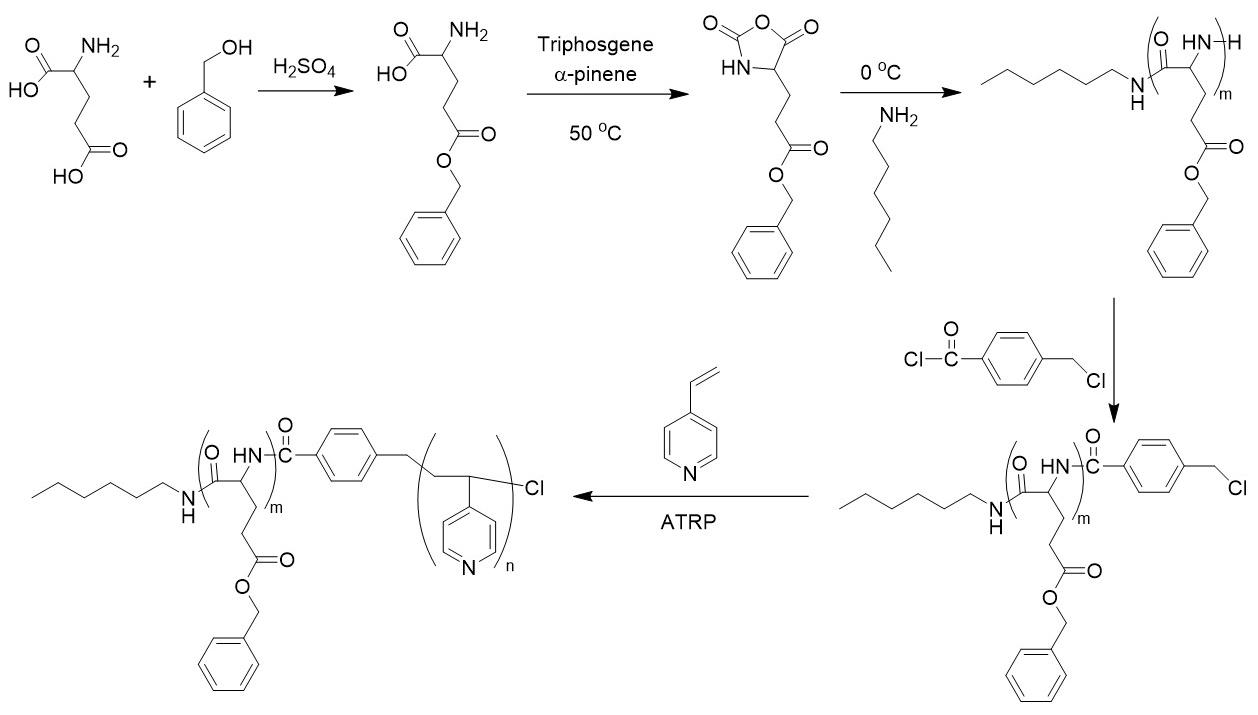

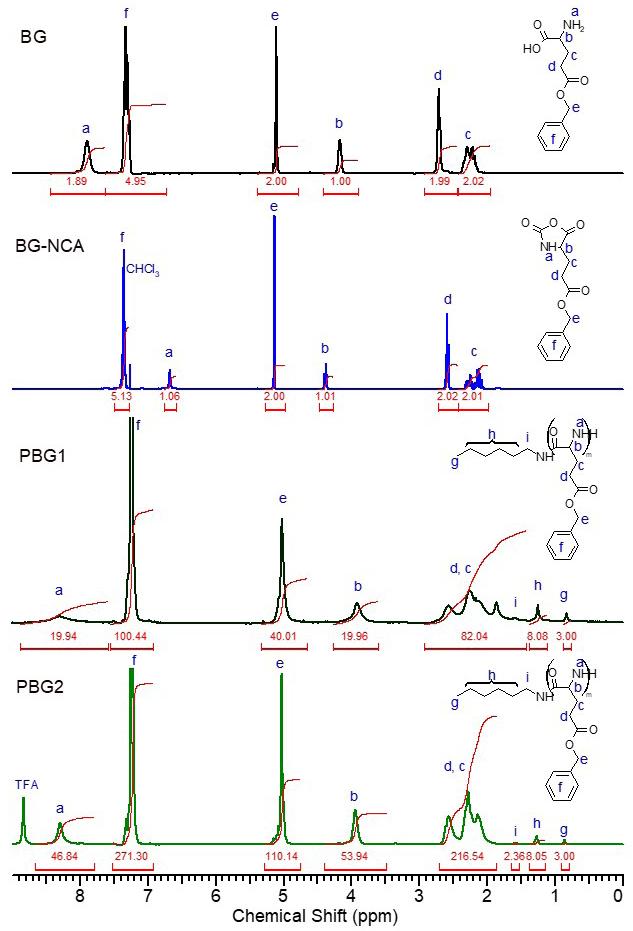

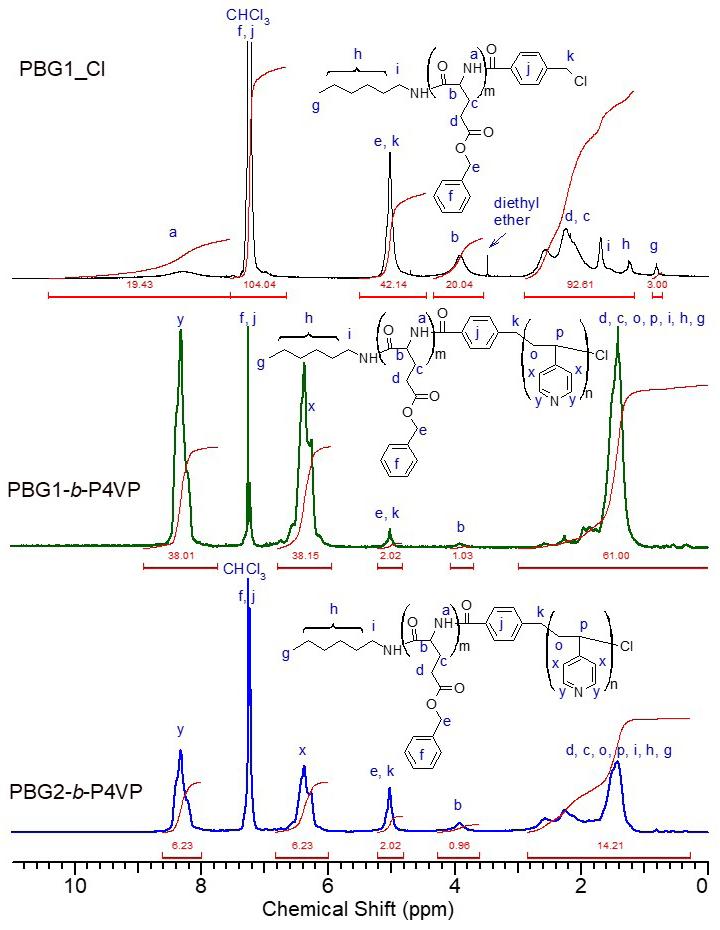

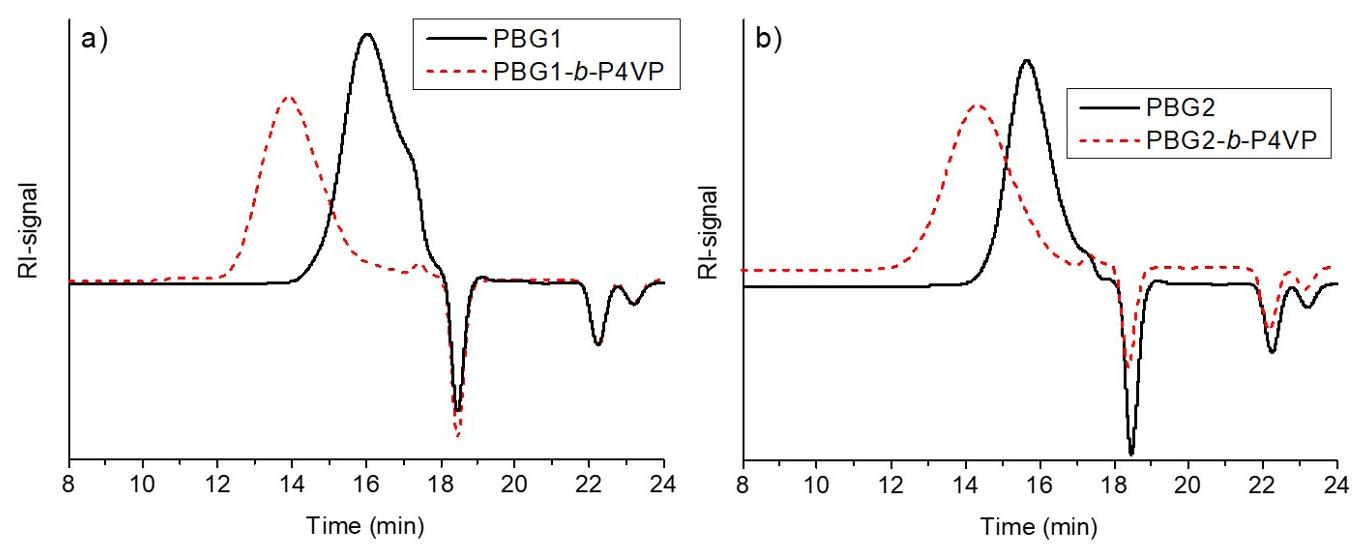

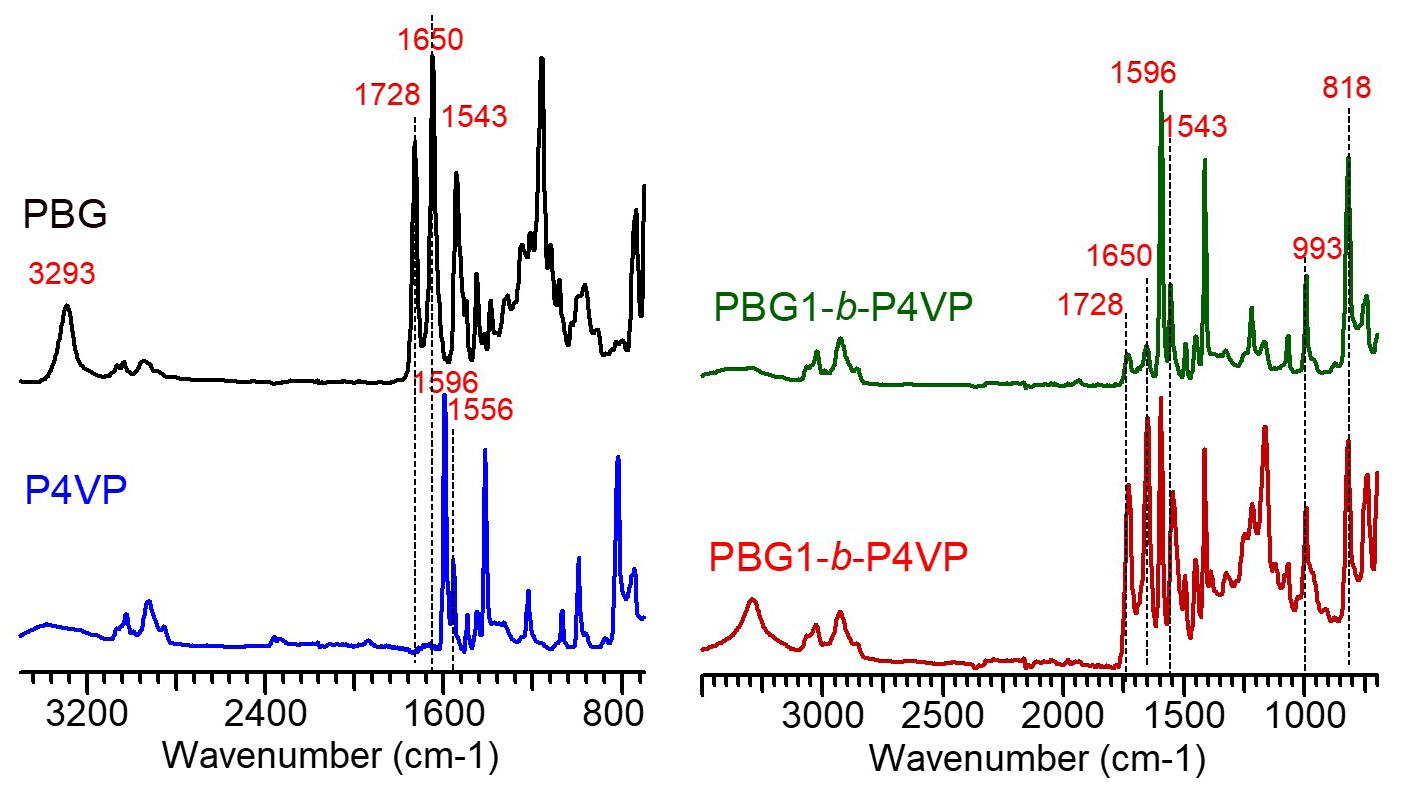

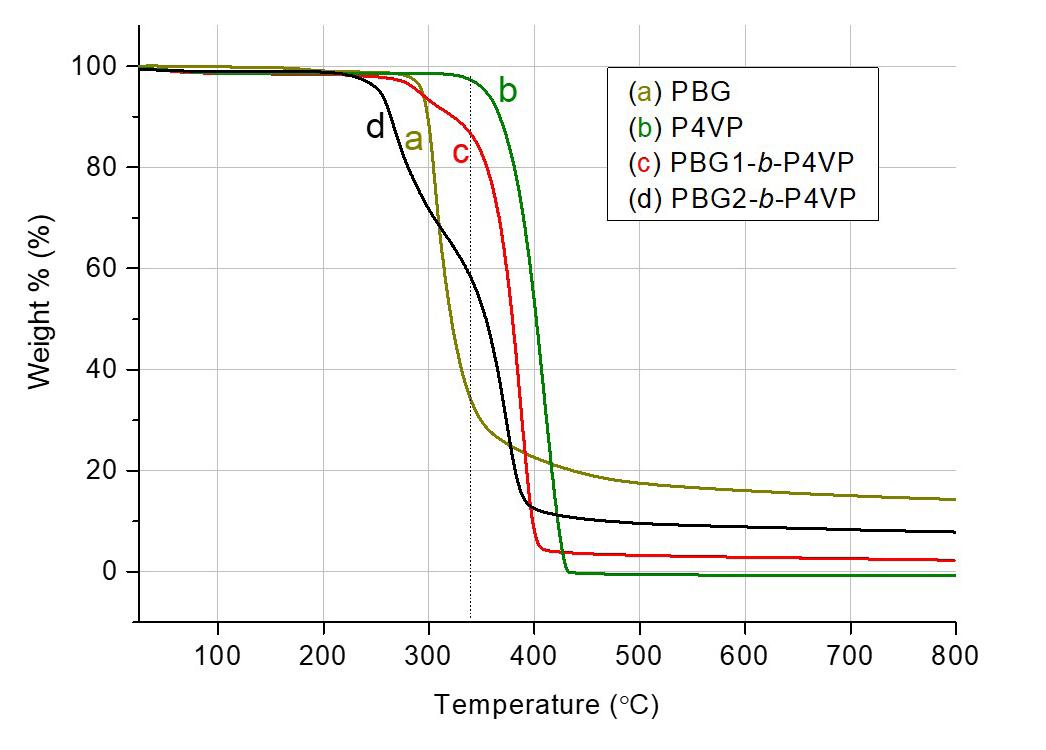

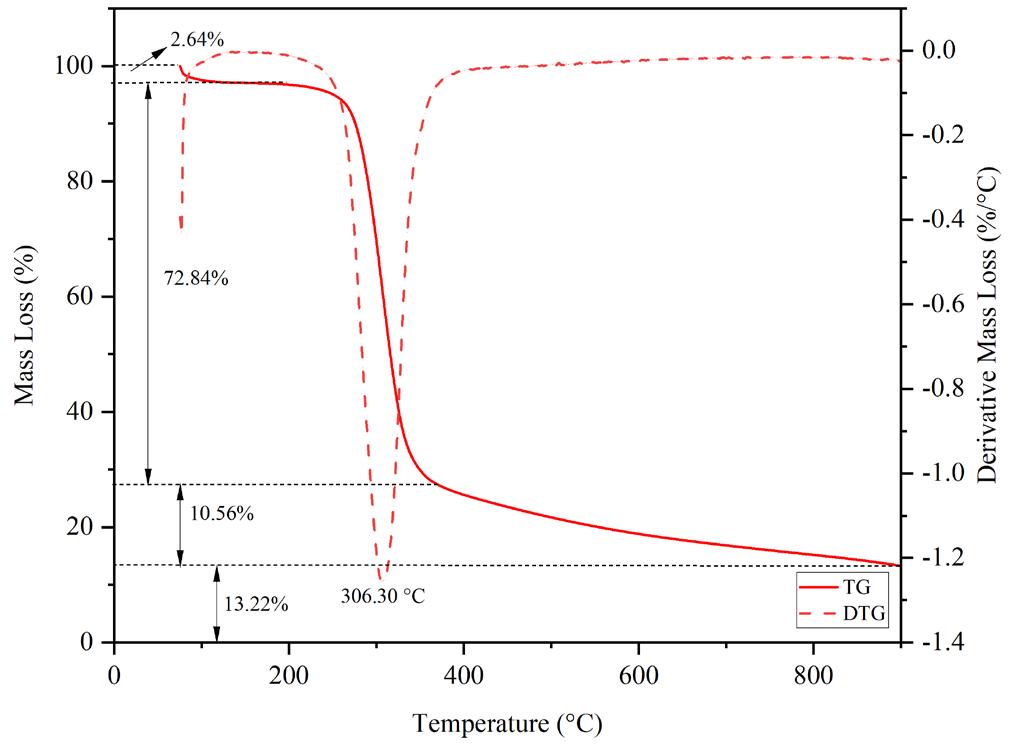

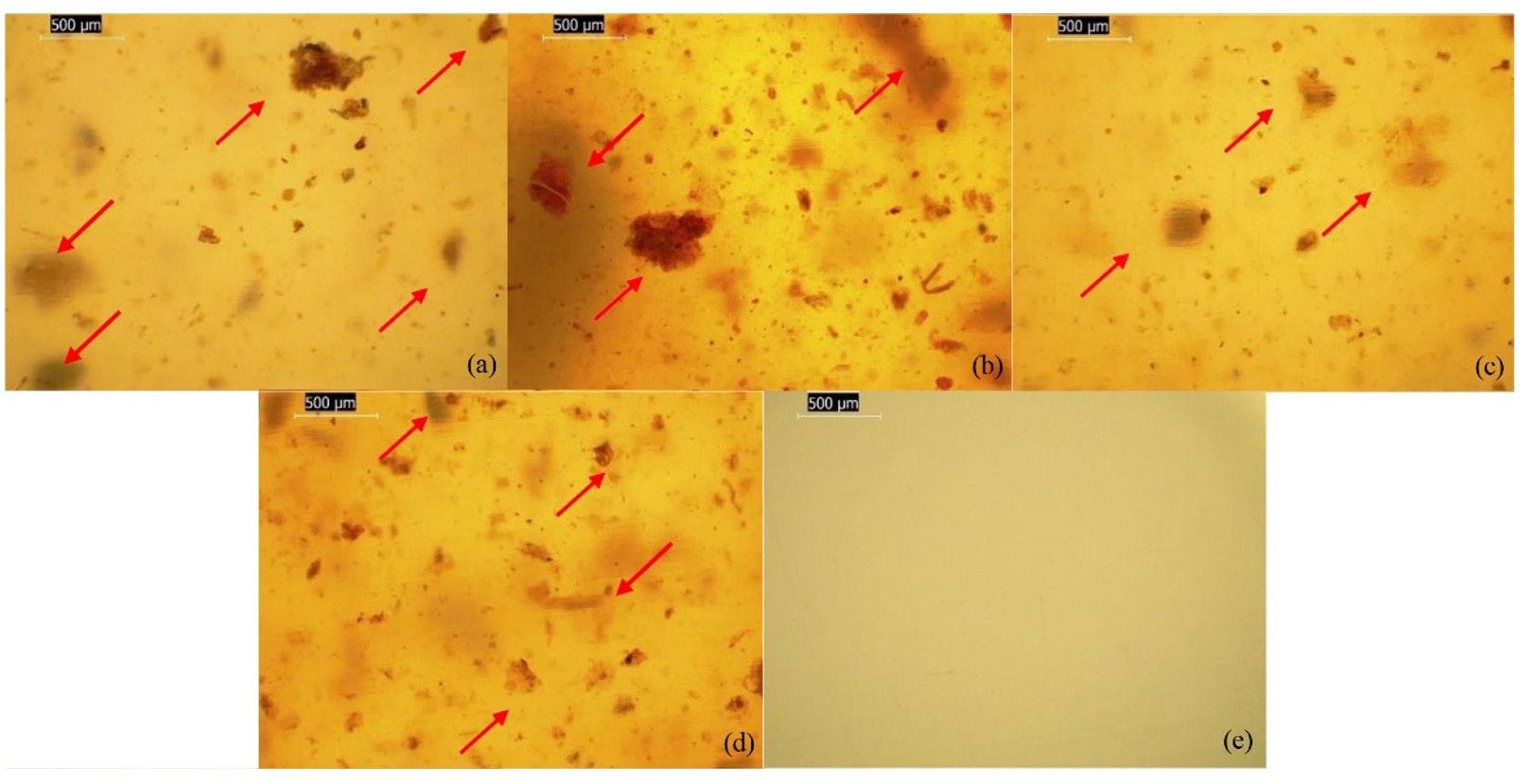

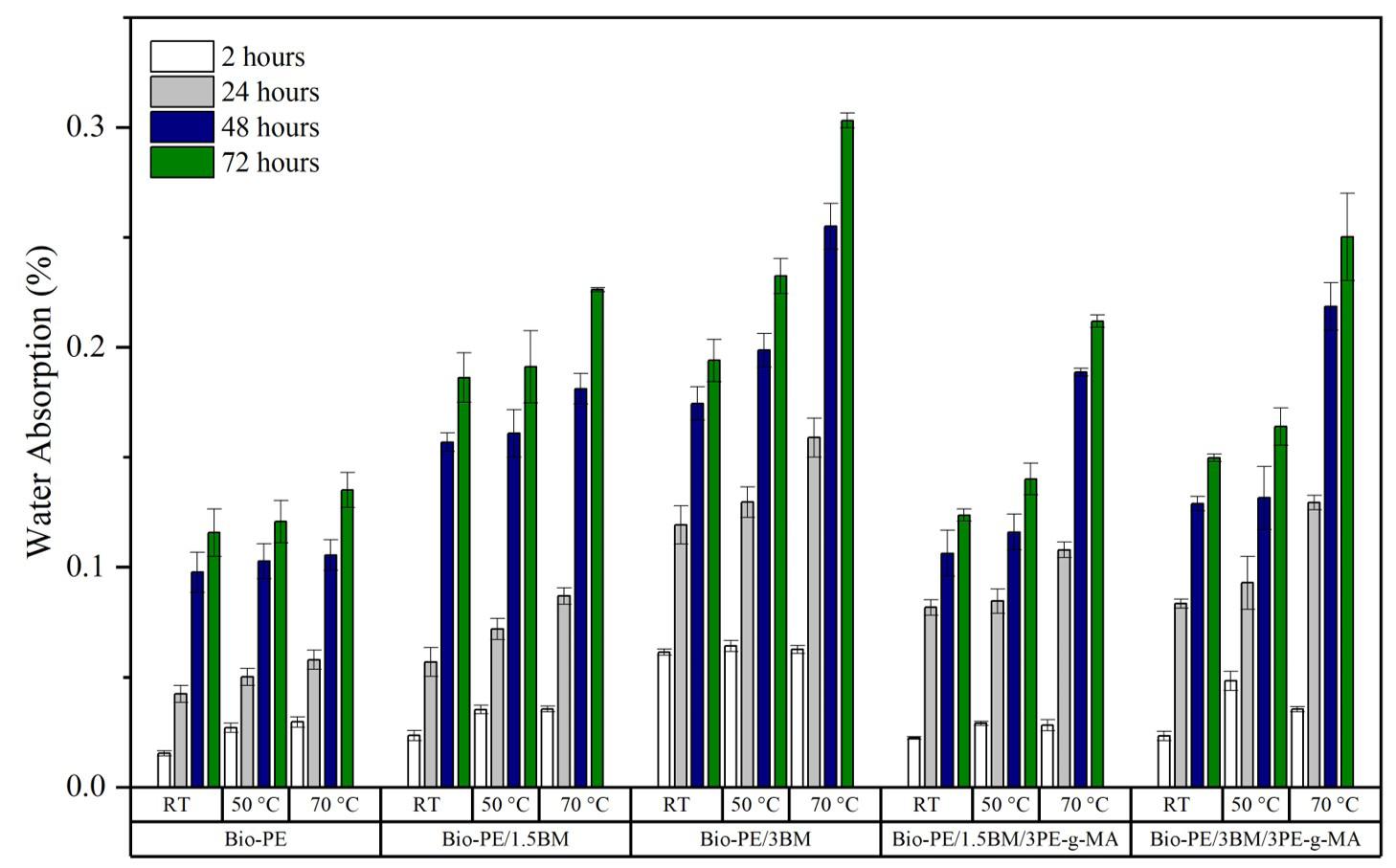

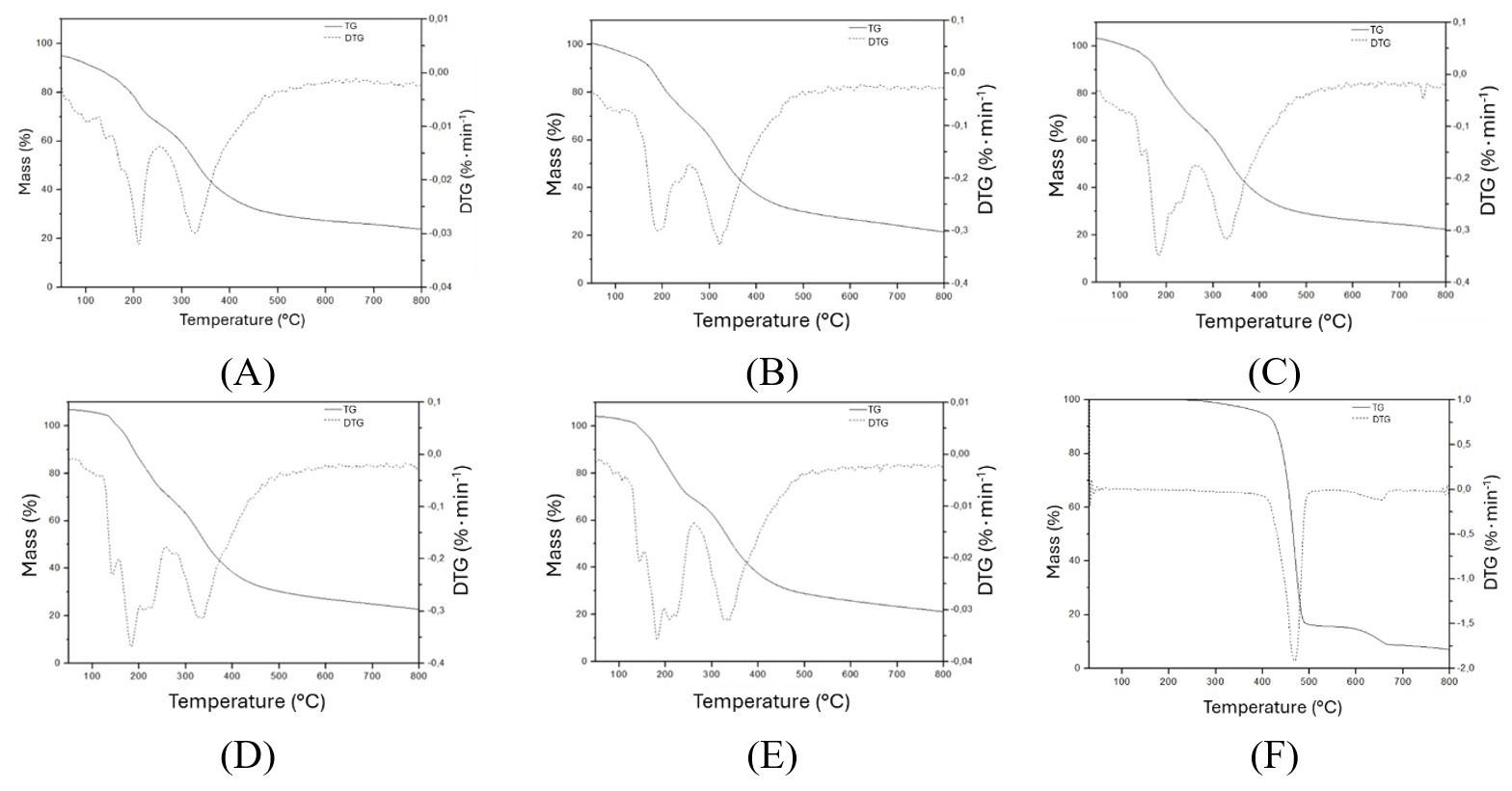

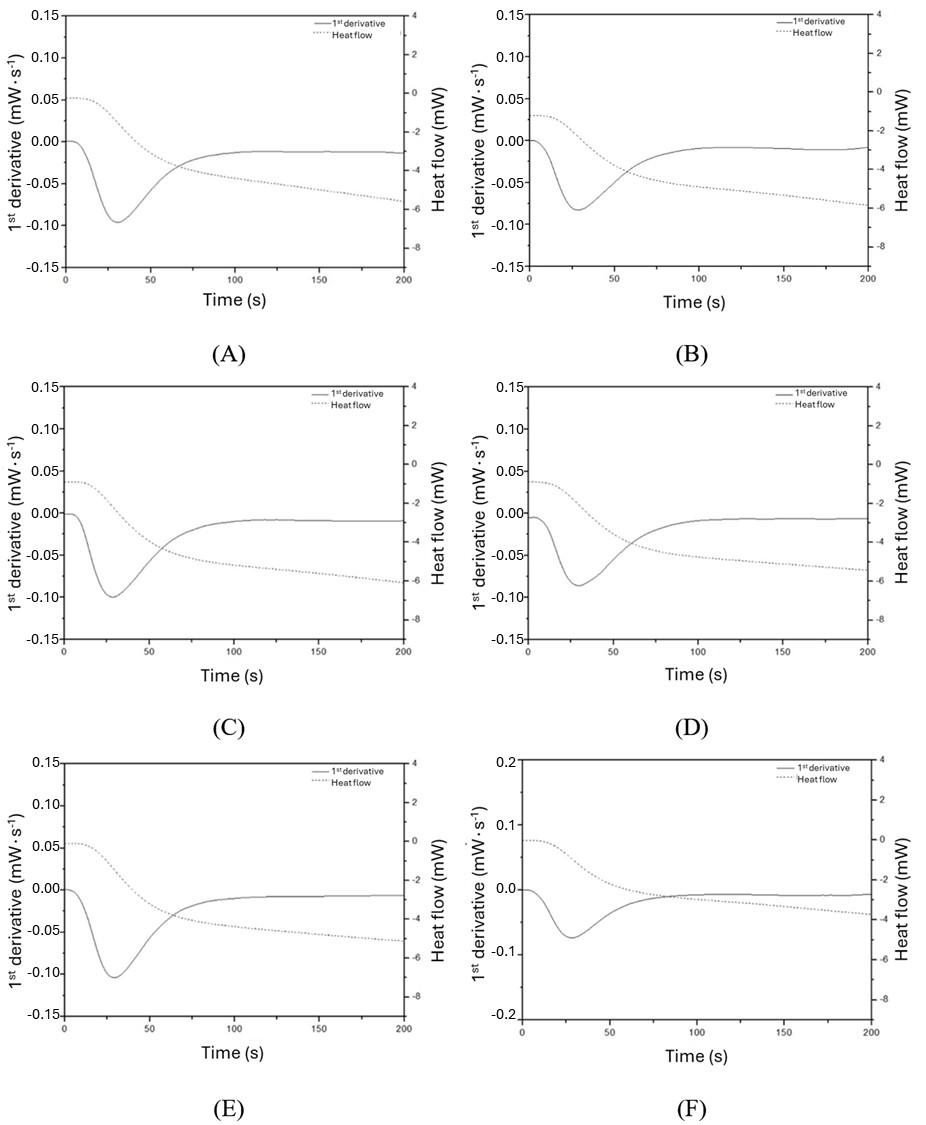

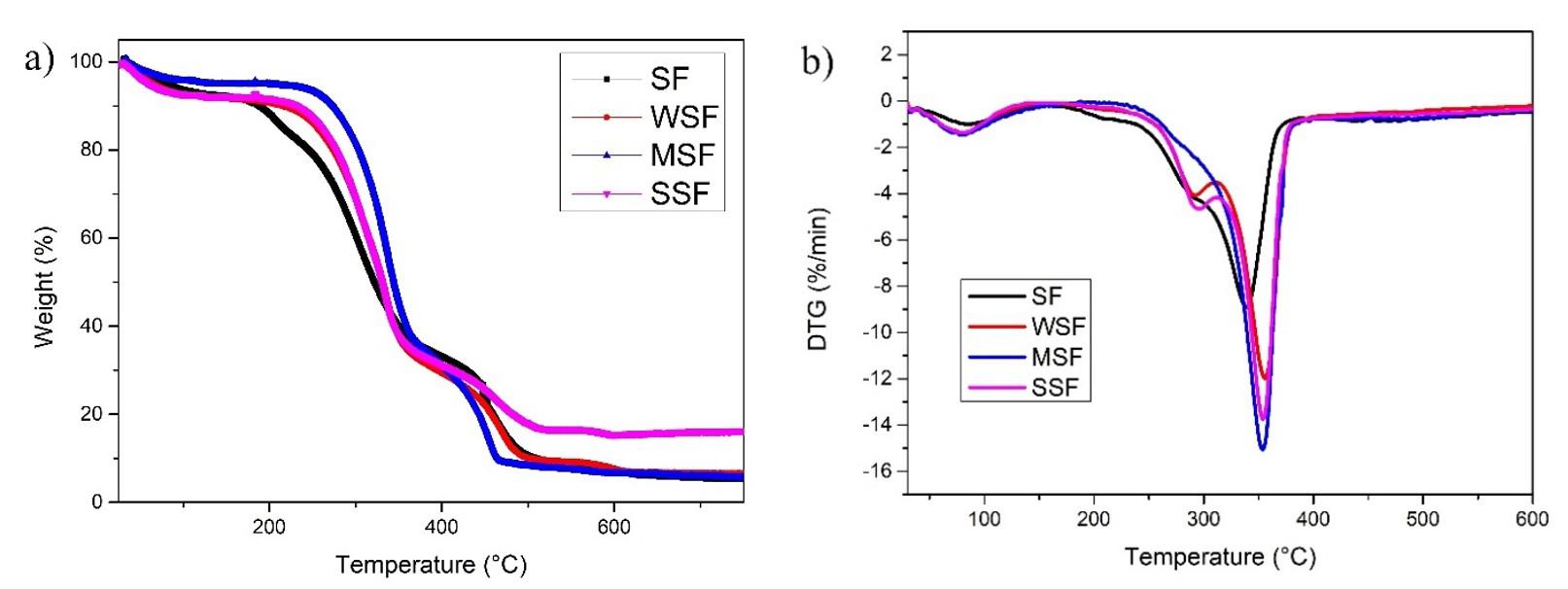

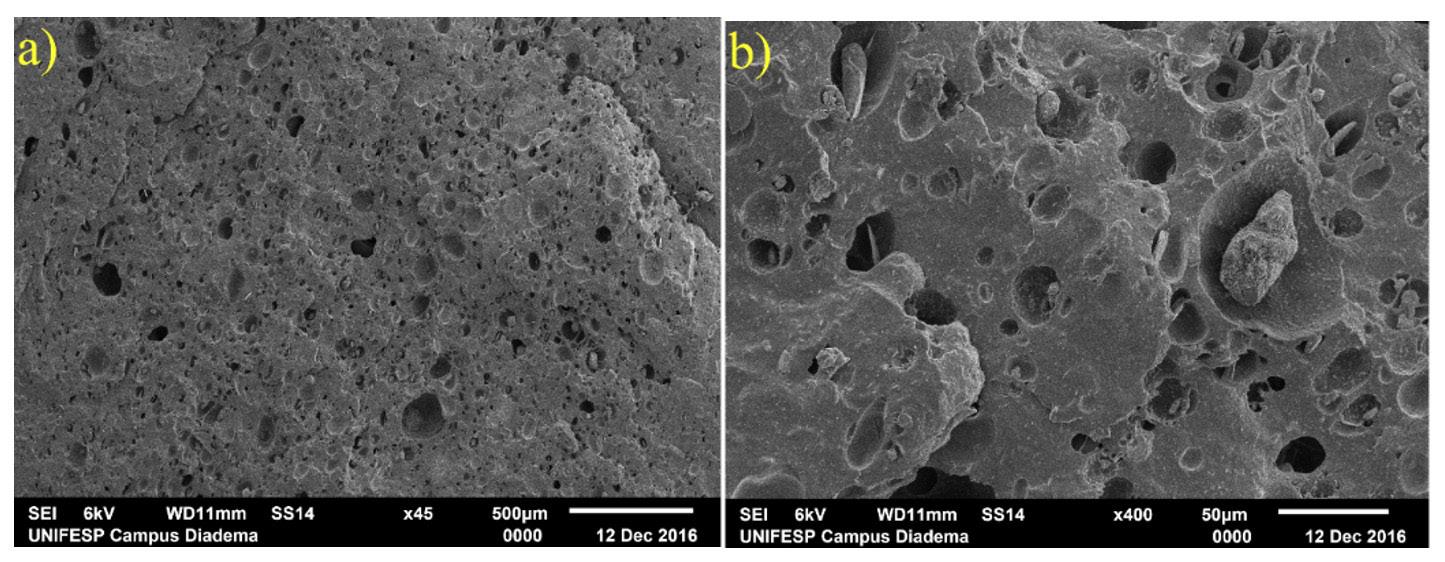

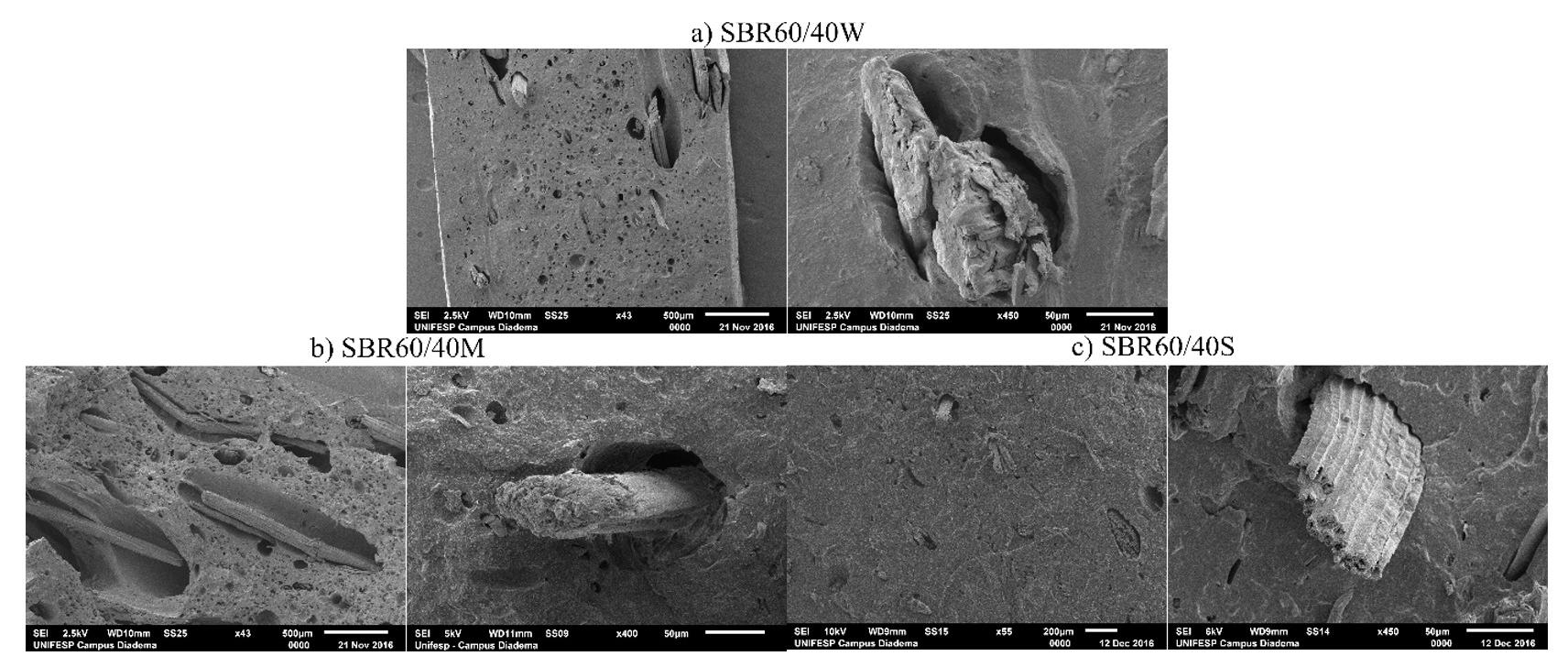

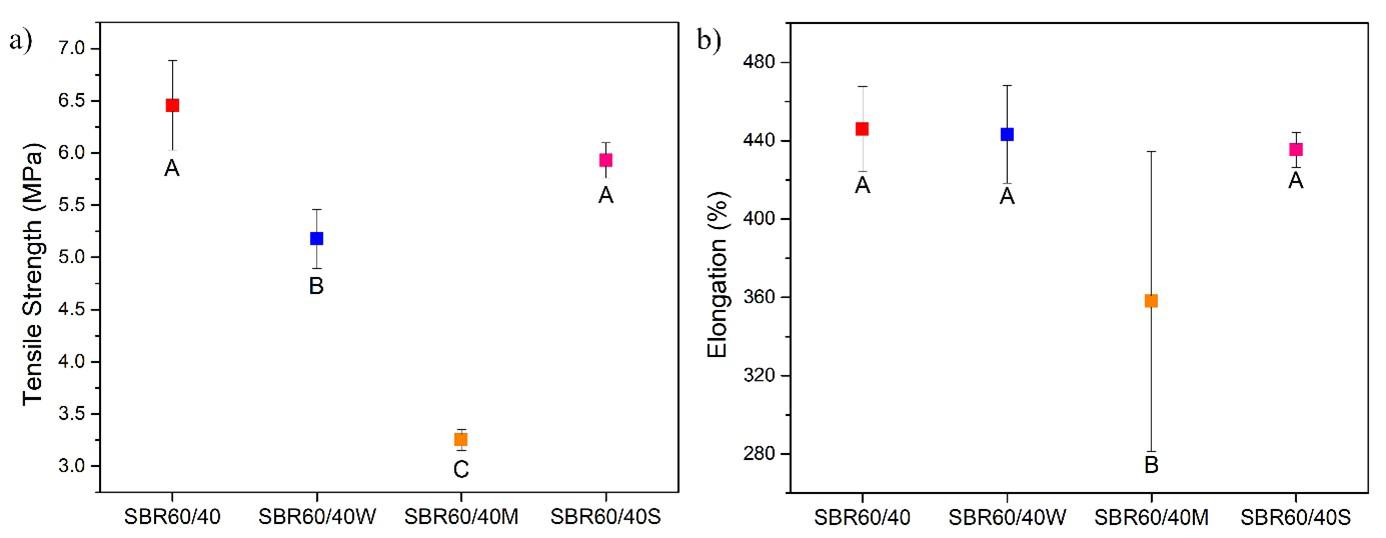

Obstract