THE 9th INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ON PLACES AND TECHNOLOGIES

EDITORS: Dr Tamás Molnár, Dr Aleksandra Djukić, Dr Aleksandra Krstić-Furundžić, Dr Eva Vaništa Lazarević, Dr Gabriella Medvegy, Dr Bálint Bachmann, Dr Milena Vukmirović, Dr Péter Paári, David Ojo

PUBLISHER: © University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology

PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE: Dr Gabriella Medvegy

PLACE AND YEAR: Pécs 2025

ISBN: 978-963-626-395-9

KEEPING UP WITH TECHNOLOGIES TO ACHIEVE LIVEABILITY

EMPHASISING HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN

CONFERENCE PROCEEDING OF THE 9th INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ON PLACES AND TECHNOLOGIES

CONFERENCE ORGANISERS

University of Pécs - Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology

University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture and Professional Association Urban Laboratory

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE

Founding members of the Organizing committee

Dr Aleksandra Đukić

Conference Director, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Milena Vukmirović

Conference Executive Coordinator, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Eva Vaništa Lazarević

University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Aleksandra Krstić-Furundžić

University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Associate members of the Organising committee

Dr Tamás Molnár

Regional Director, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

Dr Gabriella Medvegy

Dean, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

Dr Bálint Bachmann

Head of the Breuer Marcell Doctoral School, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

Judit Zoltai

Assistant to the Dean, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

Dr Péter Paári

Assistant professor, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

David Ojo

Assistant Lecturer, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

TECHNICAL COMMITTEE

Nikola Mitrovic

Researcher at the University of Belgrade - Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Balázs Gaszler

Technical Supporting Staff, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

Balázs Szentei

Technical Supporting Staff, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Pécs, Hungary

On behalf of the Organizing Committee of the International Academic Conference on Places and Technologies 2024, consisting of the PT Conference founding members, Dr Eva Vaništa Lazarević, Dr Aleksandra Krstić-Furundžić, Dr Aleksandra Djukić, and Dr Milena Vukmirović, and the host members, Dr Medvegy Gabriella, Dr Molnár Tamás and Dr Bachmann Bálint, we are very pleased and honored to realize the ninth season of PT Conference, done in collaboration with the University of Pécs – Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture and the Urban Laboratory Belgrade.

The Places and Technologies Conference has a tradition. The first conference was held in 2014 in Belgrade at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture with the aim of finding ways to improve places, the second was held in 2015 in Slovenia in collaboration with the University of Ljubljana, with the main topic concerning healthy cities, the third was held in 2016 in Belgrade at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture and was dedicated to the technologies for the creation of a cognitive city, the fourth was held in 2017 in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the University of Sarajevo – Faculty of Architecture and was devoted to urban and rural synergy, and the fifth was held in 2018 in Belgrade at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture, whose focus was the presentation and identification of new knowledge in the field of high technologies, which can be applied in the creation of adaptable cities. In 2019 the sixth conference was the first that was held at the University of Pécs – Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology with the main topic focusing on the possibilities how to turn the built heritage into the places for future generations. The seventh and the eighth conference was organized by the founders, by the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Architecture.

Each conference resulted in very reputable scientific conference proceedings, and all previous proceedings are available on the conference website. In addition to these, it is important to point out some other valuable results. Two notable results of the 2014 Conference include valuable publications Keeping up with technologies to improve places published by Cambridge Scholar Publishing and Elsevier’s Energy and Buildings Special Issue on Places and Technologies. Regarding the results of the Conference in 2016, we point out to the publication of papers by Elsevier’s Energy and Buildings International Journal and Facta Universitatis, Series Architecture and Civil Engineering Special Issue, as well as the book Keeping up with technologies to create cognitive city published by Cambridge Scholar Publishing in 2018. Regarding the results of the Conference in 2017 the book Urban-Rural Synergy Development through Housing, Landscape, and Tourism is in the process of publication by IGI Global. As for the PT conference held in 2018, in addition to the published proceedings, the planning of other publications is in progress. All these publications were based upon the evaluation of the most outstanding submitted papers from our conferences. This has proven to be a strong incentive and motivation for all professors from the Organising Committee of “Places and Technologies”, as well as for the members of the International Scientific Committee and all participants.

The Ninth International Academic Conference on Places and Technologies will be hosted on July 08 and 09, 2024 by the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology of the University of Pécs, the oldest university of Hungary that was founded in 1367. Keeping up with technologies to achieve livability emphasizing human centered design is the leading idea-motive of the

conference. Livability is a topic that is getting increasingly important as the number of humans on the globe continues to increase. The rapid urbanization phenomenon necessitates that various possibilities for affordable types of living and challenges of the livable urban environment are themes that should be widely discussed with an interdisciplinary approach. The aim of the Places and Technologies 2024 conference is to discuss methodologies and urban, architectural, or structural design ideas that can help increase the livability of the built environment.

Prof. Dr. Aleksandra Djukić, Dipl. Eng. Arch. University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Serbia Director of the Conference

Dr Tamás Molnár, DLA Habil., Dipl. Eng. Arch. associate professor, University of Pécs Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Hungary

Regional Director of the P&T Conference

Dr Laura Aelenei

Researcher at the National Energy and Geology Laboratory (LNEG), Lisbon, Portugal

Dr Bálint Bachmann

Professor and Head of Marcel Breuer Doctoral School at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Melinda Benko

Professor at BME in Budapest, Faculty of Architecture, Hungary

Dr Ágnes Borsos

Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Fernando Brandao Alves

Assosiate Professor at the FEUP Porto, Portugal

Dr Ana-Maria Branea

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Timisoara, Romania

Dr Christine Chaloupka-Risser

University lecturer in Traffic Psychology, Vienna, Austria

Dr Milena Dinić Branković

Assosiate Professor at the University of Nis, Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Serbia

Dr Grygor Doytchinov

Professor at Institute for Urban Design, Technical University of Graz, Austria

Dr Vladan Đokić

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Aleksandra Đukić

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Daria Gajić

Associate Professor at Univesrity of Banja Luka - Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Dr Bob Gidings

Professor Emeritus at the Northumbria Univesrity Faculty of Engineering and Environment, Newcastle, United Kingdom

Dr János Gyergyák

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Miklós Halada

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Cenk Hamamcıoğlu

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Department of City and Regional Planning, Yıldız Technical University - Istanbul, Turkey

Dr Jelena Ivanović Šekularac

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Arch. Milena Ivkovic

Founder of Placemaking Western Balkans, Serbia and Nederland

Dr Krisztián Kovács-Andor

Associate professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Aleksandra Krstić-Furundžić

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Jugoslav Joković

Assistant Professor at Faculty of Electronic Engineering, University of Niš, Serbia

Dr Sladjana Lazarevic

Associate Professor at Faculty of Architecture and Design, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Mr Vladimir Lojanica

Professor and Dean of the University of Belgrade - Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Ognen Marina

Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Architecture, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University Skoplje, North Macedonia

Dr Lucia Marticigh

Professor at University RomaTre, Faculty of Architecture, Rome, Italy

Dr Gabriella Medvegy

Professor and Dean at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Arch. Ljubomir Miščević

Professor at University of Zagreb – Faculty of Architecture, Zagreb, Croatia

Dr Miloš Mladenović

Associate Professor of Spatial Planning and Transportation Engineering at the Aalto University, Finland

Dr Tamás Molnár

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Pál Németh

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Florian Nepravishta

Professor at Universiteti Politeknik i Tiranës, Albania

Dr Juan Luis Rivas Navarro

Professor at University of Granada Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Granada, Spain

Dr Boris Radic

Associate Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Darko Reba

Professor at Faculty of Technical Science, University of Novi Sad, Serbia

Dr Donát Rétfalvi

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Ralf Risser

Principal research fellow at FACTUM, Vienna, Austria

Dr Lina Seduikyte

Professor at Kaunas University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Kaunas, Litvania

Dr Svetlana Stanarevic

Professor at the University of Belgrade Faculty of Security, Serbia

Dr Ljupko Šimunović

Professor at University of Zagreb Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia

Dr Olja Čokorilo

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Miroslava Raspopovic Milic

Professor at the Metropolitain University - Faculty of Information technologies, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Francesco Rotondo

Assosiate Professor at Università Politecnica delle Marche, Italy

Dr Alenka Temeljotov Salaj

Professor at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

Dr Katerina Tsikaloudaki

Professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Dr Theodoros Theodosiou

Professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Dr Stefan van der Spek

Associate Professor at TU Delft, Delft, Nederland

Dr Aleksandra Stupar

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Eva Vanista Lazarevic

Professor at University of Belgrade Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Gábor Veres

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

Dr Milena Vukmirović

Associate Professor at University of Belgrade - Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade, Serbia

Dr Bora Yerliyurt

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Department of City and Regional Planning, Yıldız Technical University - Istanbul, Turkey

Dr Erzsébet Szeréna Zoltán

Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Pécs, Hungary

8th July 2024

8:00 - 9:00 Registration

9:00 - 9:30 Opening ceremony (A007)

9:30 - 11:00 Keynote presentations (A007)

Dr. András Reith Ph.D. - ARCHITECTS: BLESSING OR CURSE?

Associate Professor at the University of Pécs CEO of ABUD

Prof. Arch. Adolfo F. L. Baratta Ph.D. - HUMAN(USER)-CENTERED DESIGN VS HOSTILE ARCHITECTURE

Associate Professor at Roma Tre University

Expert for the Italian Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport

11:00 - 11:30 Break

11:30 - 13:00 Conference sessions 01

- Urban design and planning for a better liveable urban environment session I (A007)

- Adaptable, resilient, and sustainable architecture session (A015)

- Architectural design session I (A017)

- Image, identity, and quality of place session I (A019)

13:00 - 14:00 Lunch

14:00 - 15:30 Conference sessions 02

- Urban design and planning for a better liveable urban environment session II (A007)

- Preservation of built heritage session (A015)

- Architectural design session II (A017)

- Image, identity, and quality of place session II (A019)

18:30 Conference Dinner (for those who registered)

9th July 2024

8:30 - 9:00 Registration

9:00 - 10:30 Keynote presentations (A007)

Olga Mihalikova - EMBRACING TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENTS TO FOSTER LIVABILITY: EVOLVING ROLE OF ARCHITECTS AND THEIR CURRICULA

Chair, European Network of Architects Competent Authorities

CEO, Slovak Chamber of Architects

Secretary General, Institute of Slovak Chamber of Architects

Prof. Dr. Gábor Zoboki DLA habil. - RICHTER CENTER

Full Professor at the University of Pécs

ZDA Lead Architect

10:30 - 11:00 Break

11:00 - 12:00 Roundtable (A007)

12:00 - 13:00 Lunch

13:00 - 14:30 Conference sessions 03

- Urban design and planning for a better liveable urban environment session III (A015)

- Adaptive reuse and Image, identity, and quality of place session (A017)

- Architectural design, Building Structures and Construction Technologies session (A019)

14:30 Closing Ceremony

Kondor Tamás

Juhász Hajnalka

Kalkán Dóra

Varga Dániel

Gyergyák János

Borsos Ágnes

Rácz Tamás

Medvegy Gabriella

Loddo, Gianraffaele

Ludoni, Daniela

Fülöp László

Loch Gábor

Goriel, Wafaa Anwar Sulaiman

Zoltán Erzsébet Szeréna

Molnár Tamás

SCHIZO-ARCHITECTURE:

Makri, Athanasia

Gourdoukis, Dimitris

INTEGRATING

Abu-Lail, Dana Maher Ayoub

Zoltán Erzsébet Szeréna

FEASIBILITY

Fu Ziqiang

Rétfalvi Donát

ASSESSING

Brkanić Mihić, Ivana

Koški, Danijela

Zečević, Timon Blaž

PARTICIPATORY

Finucci, Fabrizio

Masanotti, Antonella G.

Mazzoni, Daniele

Ramos González, Nicolás

Varga Konrád

Osman, Mahmoud

Kisander Zsolt

Medvegy Gabriella

Borsos Ágnes

Bittner Zsófia

Lovig Dalma

Medvegy Gabriella

Gács Boróka

Borsos Ágnes

Paári Péter

Halada Miklós

Széll Attila Béla

Széll Judit

Perényi László Mihály

Tošić, Jovana

Vrdoljak, Ivan

Miličević, Ivana

Calcagnini, Laura

Trulli, Luca

Accolla, Carolina USER-CENTERED

Baratta, Adolfo F. L.

Mariani, Massimo

Tonolo, Marina

Djukic, Aleksandra

Marić, Jelena

Lazarević, Eva Vaništa

Mitrović, Biserka

Antonić, Branislav

Jović, Emilija

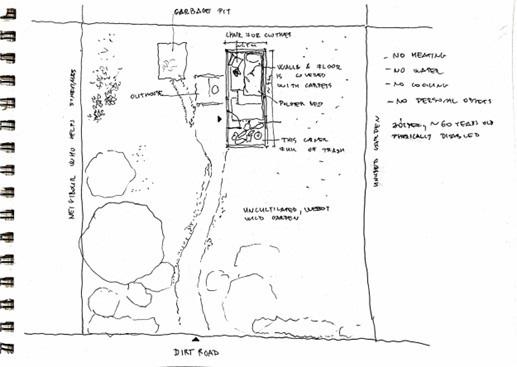

A MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDY OF SURVIVAL STRATEGIES OF MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES: THE ARCHITECT’S PERSPECTIVE

Dányi Tibor Zoltán

THE ACADEMIC ENVIRONMENT AND FACULTY WELL-BEING: A STUDY OF ZAGREB ARCHITECTURE STUDENTS’ COMFORT IN THE 2023-2024

Muraj, Iva

INVESTIGATING STRATEGIES FOR MAINTAINING THE PROSPECTIVE URBAN HOUSING IDENTITY AND LIVEABILITY IN THE CITY

Tomajian, Haik

Gyergyák János IN SHORT OF SPACE, SHARE SPACE AND SHARE POWERS TO CREATE BETTER PLACES

de Haan, Pieter

A COMPARATIVE STUDY ON THE REFURBISHMENT OF MONGOLIAN HISTORICAL WOODEN

Gombo-Ochir, Enkhjin

Molnár Tamás

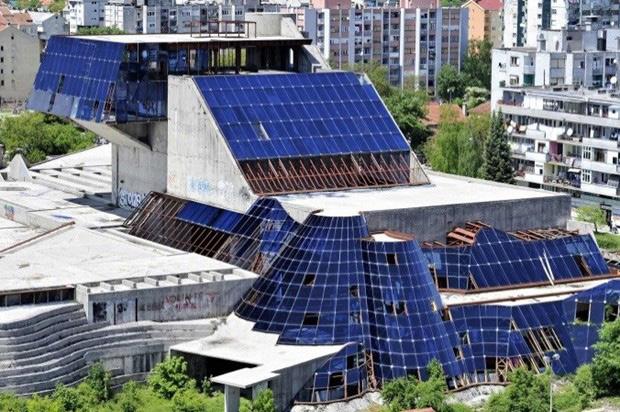

CULTURE CENTRES AS PREVIOUS POINTS OF CULTURAL DIFFUSION – CONTEMPORARY UNDERSTANDING AND IDENTIFICATION OF THE DYNAMICS OF SPATIAL

Jezdimirović, Dimitra

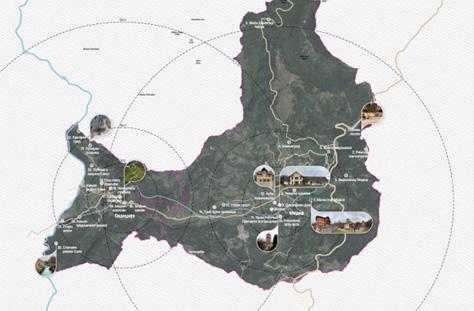

CREATIVE INDUSTRIES FOR RURAL SETTLEMENT

REGENERATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE VILLAGE OF MEDNA ��

Guzijan, Jasna

Đukić, Aleksandra

Cvijić, Siniša

Malinović, Miroslav

THE PRINCIPLE OF PERMEABILITY AND ABSORPTION OF THE CITY AS A POSSIBILITY OF CONCENTRATION OF MEANING �����

Alihodžić Jašarović, Ema

Milićević, Nemanja

Magarò, Antonio

Dukić, Anđela M.

Molnár Tamás

Špirić, Ana

Đukić, Aleksandra

Mitrović, Nikola

Djukić, Aleksandra

Stamenović, Pavle

Anja, Ljujić

Stojanovski, Mihajlo

Korobar, Vlatko P.

Igić, Milica

Dinić Branković, Milena

Đekić, Jelena

Ljubenović, Milica

Mitković, Mihailo

Khadra, Lujain Ben

Gyergyák János

Pál-Schreiner Judit

TRANSFUSION OF THE CRITICAL URBAN THEORY AND MANFREDO TAFURI’S CONCEPTUALIZATION OF CRITICAL ARCHITECTURE

Cingel, Ivan

Jurković, Željka

Lovoković, Danijela

ACTION PLACEMAKING IN BELGRADE, SERBIA: GARDENING AS A GAME-CHANGER OF AN ADAPTIVE URBAN SYSTEM

Stupar, Aleksandra

Mihajlov, Vladimir

Simic, Ivan

Grujicic, Aleksandar

Reith András1

University of Pécs,Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Boszorkány street 2., 7624 Pécs, Hungary, reith.andras@mik.pte.hu, reith.andras@abud.hu

The program for the UIA World Congress 2023 includes: Climate adaptation, Health, Inclusivity, Partnerships of change, Resilient communities, and Rethinking resources. The program does not feature “Architectural Beauty”. This is because being “just” beautiful is no longer sufficient; much more is needed. But what exactly is this “much more”?

The first step is to acknowledge and admit that architects have a significant opportunity and impact in their hands, which can be both a curse and a blessing depending on how we use it. Where do you want to belong?

Today, professions shaping the built environment, including architecture, have significant technological support. As a result, beauty can also be good - provided we make the right decisions. Across all areas, from small-scale interior design and family house interventions to urban design and various levels of spatial design, tools are available to measure and control the effects and extent of interaction. What is architectural design? It is interaction design, with all its elements and cross-effects (interactions) from the economy, through nature, to humans. This profession carries responsibility.

Architects like to shirk responsibility. However, in the end, it is we who draw and sign the plan. We must be aware that the construction industry is responsible for 50% of global resource usage. E.g. every time we sign a new construction project instead of a renovation, we create a 50% larger carbon footprint compared to renovation. Covering the roof with solar panels won’t really help with this.

However, good and happy decisions have never been made out of guilt. We should be proud that we have such significant capital in our hands, with which we can manage well. Let us change our design methodologies, professional practices, and educational formats to ensure this profession is a blessing in all aspects because being beautiful is no longer enough.

Keywords: Sustainable Design, Resilience, Interaction Planning, Integrated Design Process (IDP), Regenerative Architecture

Climate change is widely regarded as one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century, with far-reaching implications for ecosystems, economies, and societies. Among the many sectors contributing to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the built environment plays a pivotal role. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (2022), buildings and

1Corresponding author

construction are responsible for approximately 38% of global energy-related CO₂ emissions, highlighting the significant impact of the architectural profession in shaping sustainable futures. Architects, as key decision-makers in the design and development of built environments, have both the responsibility and opportunity to influence how these emissions are addressed through thoughtful design choices, material selection, and planning strategies.

Sustainability in architecture extends beyond the simplistic notion of reducing energy use or choosing eco-friendly materials. At its core lies the understanding of complex interactions between nature, the built environment, and humans - an “interaction triangle” (Figure 1.) that forms the foundation of sustainable design thinking (Reith & Brajkovic, 2021). This triangle underscores the need to balance environmental integrity, human well-being, and economic viability. Nature provides essential resources and ecosystem services, the built environment modifies these resources to meet human needs, and humans, in turn, shape both nature and the built environment through their behaviours, policies, and cultural practices. Failure to consider these interactions leads to designs that, while possibly visually appealing, may be environmentally harmful or socially disconnected.

Architects have the capacity to influence sustainability at various scales of intervention. At the component level, decisions regarding e.g. material selection, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, and façade design can significantly reduce a building’s embodied and operational carbon footprint. For instance, choosing low-carbon materials or implementing advanced glazing systems can enhance energy efficiency and reduce lifecycle emissions. At the building scale, passive design strategies, high-performance building envelopes, and integrated renewable energy systems contribute to reducing operational energy demand. Neighbourhood and city-scale interventions offer further opportunities for impact, through urban planning that promotes walkability, green infrastructure, and decentralized energy systems. Extending beyond the urban fabric, architects can engage at regional and global scales, addressing issues such as land use, resource management, and climate resilience planning (United Nations Environment

Programme, 2022).

The concept of sustainability can also encompass social sustainability, making it even more relevant for architects. The fundamental purpose of their work - designing for and with humans. Architectural design is inherently an act of interaction design, encompassing economic considerations, ecological impacts, and human experiences. Yet, in many cases, the human element remains underrepresented in the design process. Projects may prioritize aesthetic values, or client demands at the expense of occupant well-being or community needs. Humancentred design, which considers how built spaces affect health, productivity, and social cohesion, is essential for creating environments that are not only sustainable but also liveable and equitable.

Sustainability has even broader implications for architects than are often underestimated or overlooked. Each new construction project contributes to resource depletion, habitat loss, and increased carbon emissions. For example, opting for new construction instead of renovation typically results in a 50% higher carbon footprint, underscoring the importance of adaptive reuse and lifecycle thinking. While technological solutions like solar panels or green roofs are often touted as quick fixes, they cannot compensate for poor foundational decisions in planning and material use. A more profound shift in design methodologies and professional practices is necessary - one that prioritizes long-term environmental stewardship over short-term gains. The UIA World Congress 2023 program, which focuses on climate adaptation, health, inclusivity, resilient communities, and resource rethinking, notably excludes “architectural beauty” as a theme. This omission reflects the evolving understanding that visual appeal alone is insufficient in addressing contemporary challenges. The question arises: “What is this ‘much more’ that architecture requires today?” The answer lies in adopting a holistic, systems-thinking approach that acknowledges the interdependencies of environmental, social, and economic factors. Architects must embrace their dual role as creators and stewards, recognizing that the choices they make have lasting impacts not only on individual buildings but also on broader ecological and societal systems.

Positive change is achievable through a combination of innovation, responsibility, and collaboration. Architects have access to advanced digital tools and data-driven methods that enable more precise evaluations of environmental impacts. Technologies like Building Information Modelling (BIM), Building Performance Simulation and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) offer insights into how design decisions affect energy use, emissions, and resource consumption across a building’s lifecycle. However, technology alone is not the solution- It must be complemented by an ethical commitment to sustainability and a willingness to challenge conventional practices.

This paper seeks to illuminate the complex role of architects in the climate crisis, exploring how design decisions across various scales can contribute to climate-positive and energypositive outcomes. By examining key factors and strategies, it seeks to inspire architects to make informed, responsible choices that enhance both environmental health and human wellbeing. Ultimately, the profession faces a pivotal question: “Where do you want to belong?” Will architecture be a blessing, driving positive change and fostering resilient communities, or a curse, perpetuating unsustainable patterns of consumption and waste? The answer lies in the decisions we make today, shaping the environments of tomorrow.

The concept of regenerative architecture expands beyond the principles of sustainability by focusing not only on minimizing environmental harm but on actively restoring and enhancing natural and social systems (Mang, P., & Reed, B., 2012; He, Q., & Reith, A., 2022). Unlike restorative architecture, which aims to return degraded environments to their previous states, regenerative architecture seeks to create systems that thrive and improve over time, benefiting both the environment and human societies. In this discussion, four fundamental aspects are explored as pivotal in shaping a truly regenerative architectural practice: understanding humans, embracing systemic thinking through multiple scales, learning from nature by implementing nature-based solutions (NbS), and applying the Integrated Design Process (IDP). Each of these pillars offers significant opportunities for positive impact while also presenting distinct challenges.

Architecture is fundamentally about designing spaces for human use, yet there is a persistent challenge within the profession: the limited integration of human behavioural sciences such as sociology and psychology. Architects often prioritize the demands of investors or clients over the actual needs and behaviours of end-users—the individuals and communities who inhabit buildings and cities daily (Gehl, 2010). This disconnect can result in environments that are aesthetically appealing but functionally inadequate or socially alienating. By collaborating with sociologists, psychologists, and anthropologists, architects can gain deeper insights into how people interact with spaces, how cultural and social contexts influence spatial use, and how design can enhance well-being and productivity (Lawson, 2001). Understanding human behaviour informs decisions that promote inclusivity, comfort, and community engagement, which ultimately lead to more successful and sustainable projects. Integrating this knowledge into practice offers architects the chance to create innovative solutions that balance user needs and investor goals, inspiring designs that prioritize both functionality and human well-being.

Buildings do not exist in isolation; they are components within larger ecological and social systems. Regenerative architecture requires architects to adopt a systemic perspective that considers multiple scales - from materials and components to entire cities and regions (Reed, 2007). At the smallest scale, material choices significantly affect a project’s embodied carbon footprint and resource use. Selecting low-carbon, locally sourced materials can reduce environmental impacts while supporting regional economies. At the building scale, integrating passive design strategies and high-performance energy systems can lower operational emissions. Expanding to neighbourhood and city scales, urban planning decisions regarding transportation, green spaces, and energy infrastructure shape the long-term sustainability of urban environments (Ratti & Claudel, 2016).

System thinking also involves understanding the dynamics between people, groups of buildings, and broader urban systems. For example, energy communities can share renewable energy resources, creating semi-autonomous, resilient neighbourhoods (European Commission, 2020).

Urban agriculture initiatives offer exciting opportunities to enhance food security and strengthen community bonds. With thoughtful planning and collaboration, architects and planners can harness these solutions to transform urban spaces, overcoming challenges like regulatory hurdles and coordination complexities to create thriving, self-sustaining communities.

Nature-based solutions (NbS) harness natural processes to address environmental challenges while delivering social and economic benefits (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2016). In architecture, NbS can reduce energy consumption, improve air quality, and enhance urban biodiversity. Bioclimatic design strategies - such as green roofs, living walls, and natural ventilation—mitigate heat islands, manage stormwater, and provide psychological benefits to occupants (Dunnett & Kingsbury, 2008; Ulrich et al., 1991). Urban greenery can also foster community interactions and cultural identity, which are essential components of resilient neighbourhoods. Integrating nature-based solutions (NbS) into urban environments opens up inspiring possibilities to enhance ecological health and community well-being. With creative planning and strong collaboration, architects can overcome spatial and maintenance challenges, turning short-term investments into lasting environmental and social benefits.

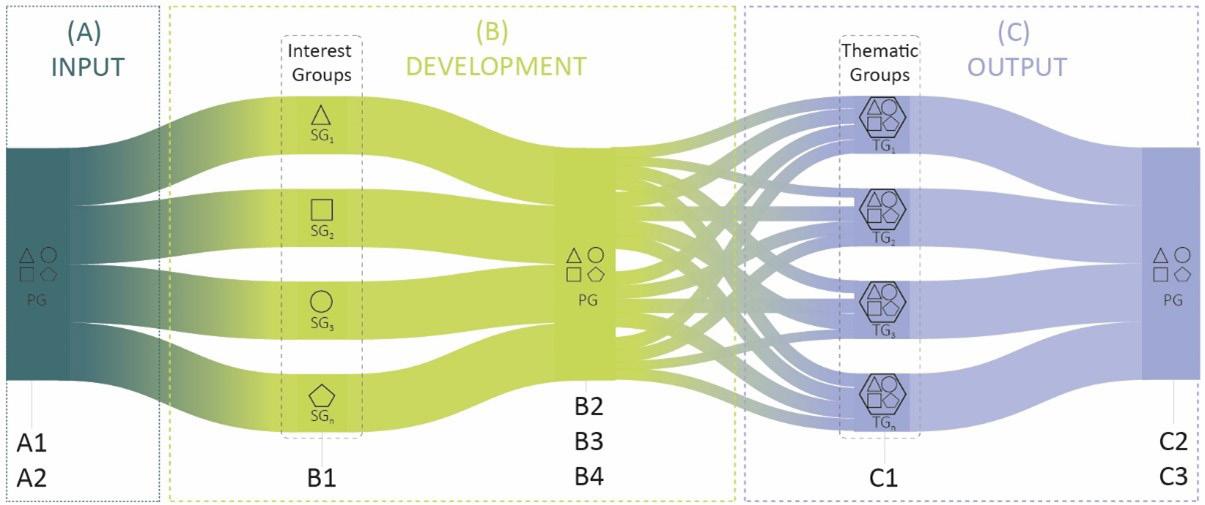

The Integrated Design Process (IDP) serves as a synthesis of the previous pillars while offering a comprehensive framework for delivering sustainable and regenerative projects. IDP is not a new concept (CIB, 1999; IEA, 2001); it has been employed for several decades to improve project outcomes by fostering collaboration among architects, engineers, consultants, clients, and end-users from the earliest design stages. Despite its longstanding existence, IDP remains underutilized, even though contemporary building and urban design challenges demand holistic and multidisciplinary solutions more than ever.

Unlike traditional linear design methods, which often involve isolated decision-making within separate disciplines, IDP encourages iterative, collaborative discussions that consider the interplay of systems, human behaviour, environmental context, and economic factors. By integrating insights from various fields early in the design process, projects can achieve higher energy efficiency, better resource management, and enhanced occupant well-being. For instance, designing a building’s HVAC system in tandem with its architectural form and material selection can lead to significant reductions in both operational and embodied carbon emissions. Likewise, community stakeholders’ involvement ensures that projects meet local needs while fostering a sense of ownership and social cohesion.

IDP is particularly valuable in addressing the complexity of contemporary building requirements, which often involve stringent energy codes, carbon reduction targets, and resilience planning. Moreover, the process aligns with regenerative principles by considering how buildings interact with natural systems and human communities at multiple scales. The use of digital tools such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) further enhances IDP by enabling detailed simulations and data-driven decision-making.

Implementing IDP offers immense benefits, and with clear communication and collaboration, diverse teams can unlock innovative solutions. While upfront costs and longer design phases

may arise, they are often outweighed by long-term savings and superior project outcomes, making the shift toward integrated approaches both worthwhile and rewarding.

In conclusion, IDP embodies the convergence of understanding human needs, embracing system thinking, and leveraging nature-based solutions to create highly efficient and sustainable environments. Its comprehensive nature makes it a vital tool for architects seeking to move beyond superficial sustainability toward genuinely regenerative design practices. If adopted more widely, IDP has the potential to transform how buildings and cities are conceived, constructed, and operated - ensuring that architecture becomes not just a blessing for present generations but a legacy of responsible stewardship for the future.

Architecture today holds the power to be either a blessing or a curse - a duality underscored by the profession’s significant role in shaping the built environment amid a climate crisis. With buildings contributing nearly 40% of global carbon emissions, architects face both a responsibility and an opportunity to drive transformative change. Moving beyond aesthetics, regenerative architecture can restore natural systems, enhancing human well-being, and designing for longterm resilience.

Central to this approach is understanding the “interaction triangle” - the dynamic relationship between nature, the built environment, and humans. Architecture has the opportunity to balance the needs of both end-users and investors by embracing human-centred design that considers behaviour, comfort, and social inclusion. Simultaneously, adopting system thinking enables architects to design across scales- from material components to entire urban ecosystems - maximizing resource efficiency and fostering synergies between buildings, communities, and environments.

Nature-based solutions (NbS) further reinforce this regenerative vision by reducing energy demands, improving air quality, and enhancing biodiversity. Despite implementation challenges, their long-term benefits in promoting resilient, healthier environments are undeniable. Complementing these strategies, the Integrated Design Process (IDP) offers a comprehensive framework that unites these principles through early, interdisciplinary collaboration. Though well-established, IDP remains underutilized, despite its proven capacity to deliver highly efficient, contextually responsive projects.

Ultimately, architects face a pivotal choice: continue conventional practices focused on immediate returns or embrace a regenerative paradigm that prioritizes planetary and societal well-being. The tools and methodologies are available - what remains is the collective will to act. By centring human needs, leveraging natural systems, thinking across scales, and adopting integrated processes, architecture can become a catalyst for positive change. The question “Architects: Blessing or Curse?” is thus answered by our decisions today, shaping a sustainable future for generations to come.

• Reith, A., Brajković, J. (2021). Scale Jumping: Regenerative Systems Thinking within the Built Environment. A guidebook for regenerative implementation: Interactions, tools, platforms, metrics, practice. COST Action CA16114 RESTORE, Working Group Five: Scale Jumping, printed by Eurac Research (Bolzano, IT)

• United Nations Environment Programme. (2022). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction.

• Mang, P., & Reed, B. (2012). Designing from place: A regenerative framework and methodology. Building Research & Information, 40(1), 23-38.

• He, Q., & Reith, A. (2022). (Re) Defining Restorative and Regenerative Urban Design and Their Relation to UNSDGs—A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(24), 16715.

• Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Island Press.

• European Commission. (2020). Energy Communities: Delivering Energy Efficiency and Social Innovation.

• Dunnett, N., & Kingsbury, N. (2008). Planting Green Roofs and Living Walls. Timber Press.

• CIB (International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction). (1999). Agenda 21 on sustainable construction (CIB Report Publication 237). Rotterdam: CIB.

• International Energy Agency (IEA). (2001). Annex 40: Commissioning of buildings and HVAC systems for improved energy performance. Energy Conservation in Buildings and Community Systems Programme. Paris: IEA.

• Lawson, B. (2001). The Language of Space. Architectural Press.

• Cohen-Shacham, E., Walters, G., Janzen, C., & Maginnis, S. (2016). Nature-based solutions to address global societal challenges. IUCN.

• Ratti, C., & Claudel, M. (2016). The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life. Yale University Press.

• Sanoff, H. (2000). Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. Wiley.

• Viljoen, A., & Bohn, K. (2014). Second Nature Urban Agriculture: Designing Productive Cities. Routledge.

• Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201-230.

Baratta, Adolfo F. L.1

Roma Tre University, Department of Architecture, Largo Giovan Battista Marzi, 10, 00153 Rome Italy, adolfo.baratta@uniroma3.it

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities requires all that have ratified it to “promote research and development of universally designed goods, services, equipment and facilities” and to encourage the conscious design in the development of inclusive solutions. The design of accessible and usable spaces, which puts people and the user at the center, is crucial since the most advanced research identifies disability as a condition determined by the relationship between the person’s health status and the environment in which that person lives. This is to say that condition is the product of health factors, which determine functional limitations, and environmental factors. In short, fragile people in fragile spaces. It can be deduced that accessibility and usability pertain to the attitude of spaces, goods and services to be used. This entails that they are identifiable, reachable, understandable and independently usable, under conditions of comfort and safety, by all.

Accessibility and usability are two key concepts that express the ability of an environment to ensure independent living for everyone. They pertain to inviolable personal rights, such as freedom of movement and self-determination, and are one of the indicators that measure a community’s level of social inclusion and quality of life. What is happening in our cities, however, often contravenes to these principles. Indeed, in order to prevent the occurrence of undesirable behavior, it is becoming increasingly common to implement hostile design strategies. These strategies are designed to introduce solution that make uncomfortable or, in some cases, impossible the use of urban furnishings and equipment. The hostile architecture wants to keep out of some places people who rely on public space more than others, such as homeless people and young people, turning our cities into inhospitable places not only for the recipients of such closure, but for everyone.

Keywords:Person, Environment, Human Centered Design, User Centered Design, Hostile Architecture

1Corresponding author

Vulnerable user identifies a category of people affected by a fragile condition associated with increasing risk or an overt permanent or temporary disability. In detail, Pope Francis, in his apostolic letter Vos Estis Lux Mundi (You are the light of the world), defined a vulnerable person as “any person in a state of infirmity, physical or mental deficiency, or deprivation of personal liberty which, in fact, even occasionally, limits their ability to understand or to want or otherwise resist the offense” (Pope Francis, 2019, Article 1, paragraph 3). This term, which would probably be better expressed as “people made vulnerable” so as to make explicit the external influence on the individual’s condition, includes a very broad spectrum of people. Italian law defines a person with a disability as “one who has a physical, psychic or sensory impairment, whether stabilized or progressive, which is the cause of difficulties in learning, relationships or work integration and such as to determine a process of social disadvantage or marginalization” (Law 104/1992, Article 3).

According to the International Classification of Functioning, disability and health, World Health Organization (WHO) disability represents “any limitation or loss (resulting from an impairment) of the ability to perform an activity in the manner or to the extent considered normal for a human being. Disability represents the objectification of impairment and as such reflects impairments at the level of the person. Disability refers to functional abilities expressed through acts and behaviors that by general consensus constitute essential aspects of everyday life” (WHO, 2001).

The evolution of the concept of disability corresponds to the cultural view that varies in different cultural and social contexts. Whereas in the past the person with a disability was seen as needing institutional help and medical care, slowly the view has shifted to the disadvantaged status of a person with a disability, which “is not an objective fact that belongs to people with disabilities, but is a social relationship, a relationship between the functional and social limitations that people may experience and the inclusion responses that society offers to their special needs” (Sedran, 2003, p. 13).

If we shift the paradigm from being people with disabilities to becoming people with disabilities, two concepts are reinforced:

1. That we all have been, are, or will be people with disabilities.

2. That the condition of disability is determined not only by physical issues, but also by environmental, social and economic factors.

Humans recognize themselves through the relationship they establish with the physical and emotional environment within which they move.

The translation of the term “comfort” in the German language is behaglichkeit, which contains within itself the word hag, meaning hedge: the etymology refers to the image of a protected, confined space within which the person can live and realize himself or herself in safety.

This means that a person’s well-being is determined by the boundary conditions, which are subjectively perceived and processed by the person. It follows from this that a person, albeit without a disability, may be in a hostile environment and not be able to perform a given activity just as, on the contrary, a person with a disability may be in an inclusive environment and be completely at ease.

On equal individual terms, therefore, the more inclusive the environment, the greater the person’s ability to self-determine his or her own existence: this indicates that by increasing the

accessibility and usability of an environment, it is possible to act positively on the well-being of the individual person and the growth of society (Baratta and Calcagnini, 2023).

The new conceptual model of disability starts from at least three categories of models that establish the magnitude of disability that afflicts a person:

- Medical model, which identifies disability with a pathological condition.

- Social model, which attributes the cause of disability to the environmental context.

- Biopsychosocial model, which identifies the limitations of the previous two models and introduces the perception of the individual facilitating the first edition of the International Classification of Functioning, disability and health (WHO, 1980).

It follows from the above that the synthesis is to define the conceptual model of disability that considers, at the same time, factors related to the person’s health and factors related to the environment. Thus, it is possible to calculate the magnitude of disability as the product of the variables consisting of the health limitations (motor, visual, hearing, cognitive, communication deficits, etc.) and the environmental variables identifiable in the barriers (physical, cognitive, communication, sensory, perceptual, cultural and social).

D = fs (Lv; Lu; Lmo; Lme; Lc) x (Eph; Es; Ei)

where:

- D is the magnitude of disability.

- fs is a function of the variables consisting of the health limitations dependent on visual impairments (Lv), hearing impairments (Lu), movement limitations (Lmo), memory loss (Lme) and communication problems (Lc);

- fa is a function of the environmental variables identifiable in physical (Eph), social (Es) and institutional (Ei) barriers.

This approach leads to a consideration of the concepts of barrier, obstacle and source of danger. In particular, it is possible to define:

• A barrier as something that prevents the performance of a normal activity.

• An obstacle as something that generates difficulties in the performance of an activity.

• A source of danger as something that may allow an activity to be carried out, but at the risk of one’s own safety.

It is evident that these three conditions can also coexist in the same solution just as it is evident that the three conditions are generically referred to as barriers.

The term “barrier” derives etymologically from “bar”, and indicates precisely a barrier that interrupts, temporarily or permanently, by its presence or absence, an action. Its association with the adjective “architectural” brings this term explicitly back to the built environment. It follows that, in detail, possible barriers can be declined according to the following model:

• Physical barriers understood as situations that prevent the free and autonomous mobility of anyone and, in particular, of people with temporary or permanent motor disabilities.

- Cognitive and communicative barriers understood as situations that limit or prevent the comfortable and safe use of spaces, equipment and services to whomever due to an unclear and immediate transmission of information to anyone and, in particular, to people with cognitive disabilities.

• Sensory and perceptual barriers understood as the absence or inadequacy of accouterments and markings (wayfinding design) that allow orientation and recognizability of places and sources of danger for anyone and, in particular, for people with sensory disabilities.

• Social and cultural barriers understood as the absence of social equity and selectivity, lack of sensitivity that leads to discrimination and social exclusion to anyone and, in particular, to people with disabilities.

USER-CENTERED DESIGN

With reference to computer science, in 1977 Rob Kling published the text “The organizational context of user-centered software designs,” in which the U.S. professor proposed a greater focus on the interface between machine and user, which is identified as introducing the concept of User-Centered Design.

User-Centered Design is a process and design approach in which the user is profiled, and the design is calibrated to the needs, desires and limitations of a specific user.

Over the last two decades, research and design of health and care spaces have changed consequent to a direction called “humanism in health care” (Alastra, 2020), a new approach to care that considers a broader framework of a person’s needs.

The principles of User-Centered Design applied to the healthcare space (so-called PatientCentered Design) contribute to this design evolution by expanding the technological culture of design from a specialized to a holistic view. Indeed, they make it possible to place at the center of the design process the interaction between the patient, with his or her capabilities and limitations, and the environmental context, where spaces play an active role in contributing to the user’s quality of life and the healing process (Del Nord and Peretti, 2012; Bosia and Darvo, 2015).

In the 1950s, starting with the reflections of psychologist Carl Rogers (Tartaglia, 2023), approaches termed Person-Centered Care were developed; the resulting scientific and cultural debate led to the definition of Human-Centered Design. In recent years, the User-Centered Design approach has been supplanted by Human-Centered Design because of its all-encompassing vision that allows diversity and uniqueness to be governed without a simplification or trivialization of problems, but by changing the reference context of design action that sees the human being as the generating element (Tartaglia, 2023).

The change of definition makes it possible to clearly mark the shift from a vision based on target groups to an approach in which human beings, in their complexity and variability and breadth of needs that are not only functional in nature, become the center of a holistic design activity (Giacomin, 2014) capable of contemplating the different facets identified and defined by the social sciences.

The Human-Centered technique starts from the concept of environmental and psychophysical well-being by establishing a correlation between person and environment aimed at healing their conflicts: it is a design approach that puts the person at the center.

Human-Centered Design is a design approach that involves people in observing the problem within the context, brainstorming, conceptualizing, developing and implementing the solution. This approach focuses on people, their needs, and, by applying ergonomics principles and usability techniques, improves human well-being, accessibility, and sustainability while counteracting adverse health and safety effects.

Accessibility and usability are constantly evolving areas of research and design, linked to the cultural and social growth that these issues have been able to solicit at the private and public, individual and collective levels, not without encountering obstacles because “even today guaranteeing or not guaranteeing inclusion means guaranteeing or not guaranteeing people’s rights and their self-determination” (Baratta, Conti and Tatano, 2023, p. 10).

In this sense, the use of a User-Centered Design approach first and then a Human-Centered Design approach has fostered the conditions so that each person will be able to do, to the extent and in the ways possible, what others can do, realizing the same opportunities for fruition for the widest possible range of people.

The future will see scholars direct research toward solutions that can match the scale of the person (microscale) with the scale of the environment (macroscale), moving toward Human&Environment-Centered Design.

• Alastra, Vincenzo. 2020. Umanesimo della cura. Creatività e sentieri per il futuro. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia.

• Baratta, Adolfo F.L., and Calcagnini, Laura. 2023. “Persone con disabilità.” In Manifesto lessicale per l’accessibilità ambientale. 50 parole per progettare l’inclusione, edited by Baratta, Adolfo F.L., Christina, Conti, and Tatano, Valeria. 226-232. Conegliano: Anteferma Edizioni S.r.l.

• Baratta, Adolfo F.L., Christina, Conti, and Tatano, Valeria. Edited by. 2023. Manifesto lessicale per l’accessibilità ambientale, 50 parole per progettare l’inclusione, Conegliano: Anteferma Edizioni S.r.l.

• Bosia, Daniela and Darvo, Gianluca. 2015. “Le linee guida per l’umanizzazione degli spazi di cura”, Techne, no. 9: 140-146.

• Del Nord, Romano and Peretti, Gabriella. 2012. L’umanizzazione degli spazi di cura. Linee guida. Rome: Ministry of Health.

• Kling, Rob. 1977. “The organizational context of user-centered software designs.” MIS Quarterly, no. 4: 41-52.

• Giacomin, Joseph. 2014. “What Is Human Centred Design?”, The Design Journal 17, no. 4: 606-623.

• Papa Francesco. 2019. “Vos Estis Lux Mundi”, Apostolic Letter in the form of Motu proprio. may 7. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/it/motu_ proprio/documents/papa-francesco-motu-proprio-20190507_vos-estis-lux-mundi.html.

• Law of February 5, 1992, n. 104, “Legge-quadro per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate”.

• Sedran, Daniela. 2003. Il Disabile. Persona o risorsa. Perugia: Morlacchi Editore.

• Tartaglia, Andrea. 2023. “Human/User-Centered Design.” In Manifesto lessicale per l’accessibilità ambientale. 50 parole per progettare l’inclusione, edited by Baratta, Adolfo F.L., Christina, Conti, and Tatano, Valeria. 190-193. Conegliano: Anteferma Edizioni S.r.l.

• WHO. 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Accessed November 13, 2024. https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-icf/en.

Mihalikova, Olga1

European Network of Architects Competent Authorities, CEO, Slovak Chamber of Architects

Secretary General, Institute of Slovak Chamber of Architects, Námestie SNP 18, 811 06, Bratislava, Slovakia, mihalikova@komarch.sk

The architectural profession in Europe is undergoing significant transformation, driven by technological advancements, sustainability imperatives, and changing societal needs. With over 620,000 architects and 150,000 architectural practices contributing to a €21 billion turnover, the sector plays a crucial role in shaping the built environment. This paper explores the evolving role of architects, focusing on the integration of new technologies and sustainable practices to enhance livability. It highlights key statistics on the profession, including the growing number of female architects, the internationalization of practices, and the increasing emphasis on sustainable design. The paper also discusses the importance of architectural quality, as outlined in EU policies, and the shift from human-centric to life-centric urban planning in light of the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Keywords:Architects, Sustainability, European Architecture, Quality of Design, Climate Change

The architectural profession in Europe is at a crossroads, shaped by rapid technological advancements, the urgency of climate change, and evolving societal expectations. This paper examines the current state of the profession, its challenges, and its future directions.

The architectural profession in Europe is characterised by a diverse range of activities, with 56% of architects primarily engaged in private housing work and 62% focusing on building design. The profession has reached a record high in full-time employment, with 86% of architects working full-time. Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the number of female architects, who now represent 46% of the workforce, marking a 10% rise. This shift has

1Corresponding author

been accompanied by a reduction in the gender pay gap, which now stands at 17%, half of what it was in 2012. Additionally, the profession has seen a decline in unemployment, dropping to just 2% in 2023, a notable improvement from 7% in 2020.

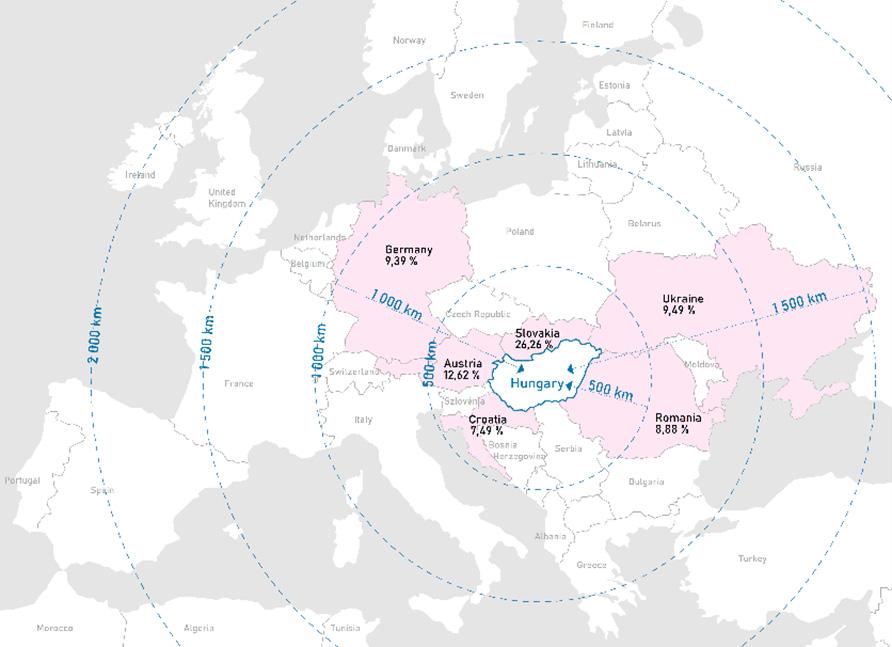

The internationalisation of architectural practices is another key trend, with an average of 2.5% of the total turnover of practices coming from projects in other countries. Approximately 7.5% of architectural offices operate internationally, and 19% of architects have considered working abroad, though many cite personal, practical, or relocation issues as barriers. Furthermore, over 20% of architects have gained part of their education abroad, reflecting the growing global interconnectedness of the profession.

The regulatory framework for architects in Europe is governed by two key directives: the ‘Architect’ Directive’ (No. 384/1985) and the ‘Directive on Recognition of Professional Qualifications’ (No. 36/2005). These directives ensure that architects who are fully qualified in one EU Member State have access to practice in all others. The framework emphasises learning outcomes, skills, and knowledge, providing a standardised approach to professional qualifications across the EU.

Sustainability has become a central focus in architectural practice, with nearly half of architects frequently incorporating sustainable concepts into their designs to create low-energy buildings. Among these, 16% focus on nearly Zero Energy Buildings (nZEB), 12% on Circular Design, and 9% on Plus Energy Buildings. These practices reflect a growing awareness of the need to address climate change through innovative and environmentally responsible design. The integration of sustainability into architecture is not only a response to environmental challenges but also a way to ensure long-term economic and social benefits.

The quality of architecture is a multifaceted concept that encompasses several key dimensions. Architectural integrity requires that projects be capable of stimulating, engaging, and delighting their occupants while maintaining environmental and economic sustainability. Projects should also demonstrate flexibility for future use and be detailed with rigour. Usability and context emphasise the importance of architecture responding generously to the public realm, contributing to the community, and addressing accessibility and social factors. Finally, delivery and execution focus on the project’s ability to meet the client’s brief, stay within budget and timeline, and provide value for money. The EU has increasingly prioritised architectural quality, as seen in initiatives like the European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture (Mies Award) and the New European Bauhaus.

In the context of the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, there is a growing need to shift from human-centric to life-centric urban planning. This approach seeks to balance ecological and human values, addressing global challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Multidisciplinary research highlights the importance of creating urban environments that not only meet functional and economic demands but also promote social interaction and a sense of belonging. High-quality design solutions are essential in achieving this balance, as they connect people, foster social interaction, and contribute to the overall well-being of communities.

The evolving role of architects requires a holistic approach that integrates technology, sustainability, and quality design. By embracing these principles, architects can contribute to a high-quality living environment that meets the needs of both people and the planet. The presentation concludes with a call to action for architects to lead the way in creating sustainable, inclusive, and culturally significant spaces.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of the ACE (Architects’ Council of Europe) and other organizations whose studies and reports provided valuable data and insights for this presentation.

• Davos Declaration 2018. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://davosdeclaration2018.ch/en/

• EUmies Awards. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://eumiesawards.com/

• Mirza & Nacey. 2022. ACE Sector Study. 2022. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://ace-cae.eu/ it/publication/ace-sector-study/ .

• Report of the OMC (Open Method of Coordination) of EU Member State Experts, 2021

• Royal Institute of British Architects. 2030 Climate Challenge. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://www.architecture.com/about/policy/climate-action/2030-climate-challenge?srslti d=AfmBOopwNopcvK93cLSSKCj4Pkhzozc4QF96H1ot0OntclQetsV4-KR_

• UN Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://sdgs. un.org/goals

Zoboki Gábor1

University of Pécs,Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, Boszorkány street 2., 7624 Pécs, Hungary, ZDA-Zoboki Építésziroda, Zugligeti street 3., 1121 Budapest, zoboki.gabor@mik.pte.hu, zda@zda.hu

The architecture of the Richter Center reflects the company’s dynamism and community orientation – A new era for Richter Gedeon

Designed by Zoboki Design and Architecture, the new Richter Gedeon headquarters marks the beginning of a new era for the company. This building not only pays homage to Richter’s history and tradition but also stands as an outstanding example of modern architecture, blending functionality, sustainability, and distinctive form. The aim of constructing this new headquarters was to create an inspiring and efficient workplace that reflects the company’s commitment to innovation and community values.

Richter’s tradition and vision

The Richter Center is located along Gyömrői Road, on a historical site that has been continuously expanded over the decades. Following a deliberate land use strategy, the company revitalises its original factory sites on the north side of Gyömrői Road while gradually developing the south side based on a long-term master plan created by ZDA 20 years ago. The new building, positioned centrally on the southern site next to the Chemical Research and Office Building, bridges the noble past of the company with its future developments.

Keywords: Gedeon Richter Plc., Gábor Zoboki, sustainability, innovation, architecture

1Corresponding author

The architectural concept is built on three main principles: functionality, innovation, and moderation. These goals guided every step of the design process, ensuring that the building meets user needs while being aesthetically outstanding.

• Functionality: The initial phase of the design process focused on shaping the interior spaces to maximally support the efficiency and well-being of employees. Offices, meeting rooms, and communal areas are designed to be humane and ergonomic.

• Innovation: The building’s form, appearance, and the modern architectural technologies and materials used all reflect the company’s values and future-proof nature.

• Moderation: The building’s exterior appearance is elegant and refined. The use of materials and the design of the façade are both modern and timeless.

The architectural concept aimed to combine the highest level of interior functionality with a unique exterior appearance. The connection between the new Center and the 2007 Chemical Research and Office Building, also designed by ZDA, is ensured by the conference unit. The central spaces of the buildings are linked by a generous bridge that unites research and corporate management both functionally and symbolically.

The façade reflects the two fundamental elements of research and development: invention and strict regulation. Each element is part of a rule-based system, yet they all take on unique forms. Viewed from a distance, the building appears as a unified work of art, while up close, the creativity and precision in the fine details are revealed.

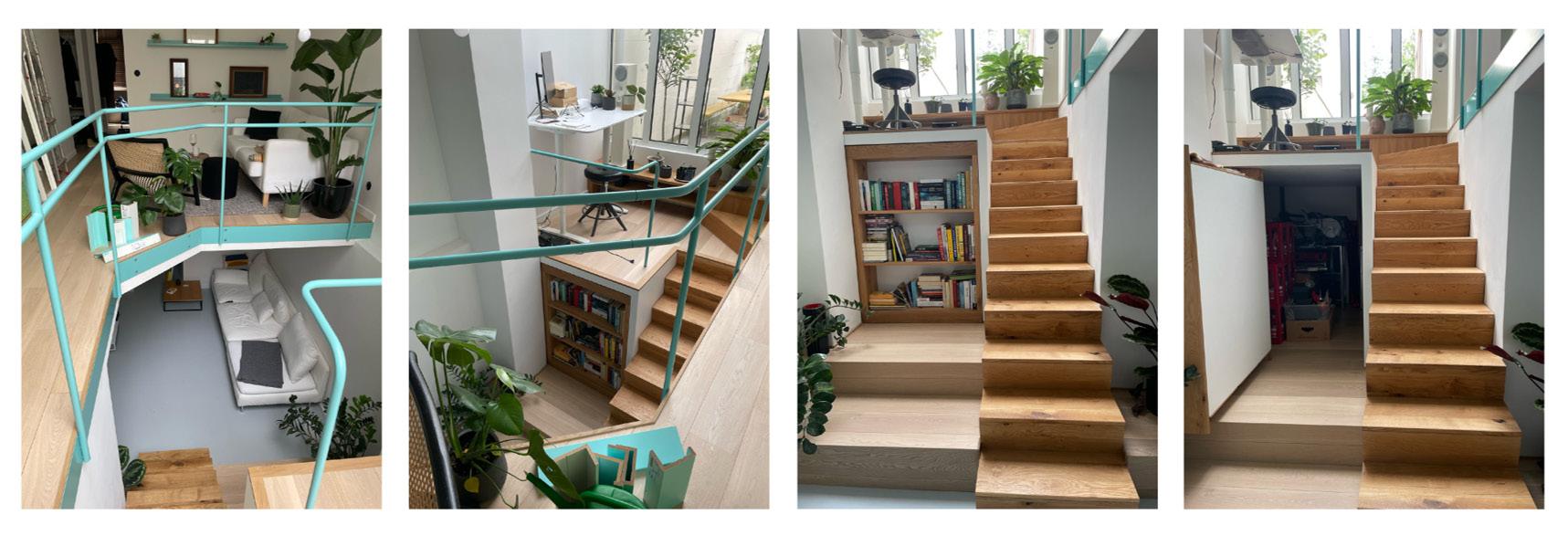

The undulating forms run through both the interior and the exterior spaces. This sense of flow is also reflected in the grand central space of the building: with the virtuoso stair structures it not only serves circulation but it is also a place for communication and meetings. While the arrangement of the interior spaces serves the daily life of the employees in a humane way, the exterior represents Richter’s brand identity.

At the beginning of the design process, the focus was on functionality and the optimal arrangement of the interior spaces. A number of interviews were conducted and discussions were held with the employees of Richter before the start of the design process. Community spaces and workspaces support one another in the building, ensuring the availability of colleagues and equally supporting collaboration and work processes that require focus.

The well-lit atrium – the central space of the building – is both generous and humane in scale. The dynamic forms of the atrium and the stair structure merge into one as they connect interior and exterior spaces, creating a notion of continuity.

Ergonomics and acoustic comfort were key considerations in the design of workspaces. This is also supported by the natural materials and the colours used in the interior spaces, contributing to a calm and inspiring work environment. The combination of wood, glass and render create a modern yet warm atmosphere that is in harmony with the exterior of the building.

Community spaces – the atrium, the connected cooperative and relaxation areas, the restaurant and the cafe – have a friendly and welcoming vibe, which is ideal for informal collaboration.

The undulating shape of the façade is strikingly effective from an aesthetic standpoint, symbolizing the company’s dynamic and innovative perspective, but it also serves a functional role. The boundary between the fully glazed lower communal floors and the upper, more enclosed workspaces defines the wave form. In the atrium space, the glass surfaces created by the wave provide visual connections between the interior and exterior spaces. The more

enclosed façade of the offices, protected by louvers, ensures ideal natural diffuse lighting for the interiors, promoting a pleasant and energy-efficient working environment. The use of different materials and forms creates a combination of unity and individuality, where each element is part of a larger system but also has a distinct character.

Creating the expansive communal spaces required the development of several large-span structures, which were challenging from a structural perspective. The building’s steel beams and glass pillars are of such dimensions that they required special technology to implement.

Additionally, various technical challenges had to be overcome in terms of sustainability, such as the heat absorbed by large surfaces. Special and precise design was essential to ensure ideal and humane interior comfort. The heating and cooling surfaces had to be harmonised with the workspaces’ acoustic and natural and artificial lighting conditions in the dynamically differentsized spaces within the building.

The louvers forming the undulating façade are all unique, yet they follow a uniform rule set, providing aesthetic and structural coherence. Achieving these virtuoso forms necessitated a new type of parametric tool-based collaboration between architects and engineers.

The dynamic and striking forms serve the principles of environmentally conscious building design. The building’s energy efficiency is supported by innovative technologies and solutions, such as ground probes that significantly reduce energy consumption and emissions. These probes utilise the Earth’s thermal energy to provide winter heating and summer cooling, minimizing the building’s energy requirements. In addition to natural diffuse light, the building employs energy-efficient lighting systems that contribute to sustainability.

Green roofs and water features improve the building’s microclimate and enhance local biodiversity, increasing insulation and reducing energy consumption. The rooftop garden actively contributes to sustainable water management by collecting and reusing rainwater within the building.

Incorporating sustainability aspects into the design and construction process has resulted in the Richter Center being not only environmentally friendly but also economically viable in the long term. The building’s design and the applied technologies ensure that this unique office building operates with a reduced ecological footprint, setting a precedent for future architectural projects.

The sustainability solutions in the building not only protect the environment but also reflect the company’s social responsibility, strengthening Richter Gedeon’s commitment to future generations. The building symbolises the effort to harmonise sustainability and innovation, creating a workplace that inspires and sets an example for the community.

Nenadović, Aleksandra1

PhD, Assistant Professor, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73/II, Serbia, aleksandra@arh.bg.ac.rs

One of the key aspects that is considered when designing building structures is related to climatic conditions. Current design standards for structural design are based on the assumptions of stationary climate conditions observed in the past. However, scientific community indicates that climate is changing, meaning that climate conditions of the past will not be representative of those of the future. The requirement to ensure liveability, which includes building users’ safety, and the uncertainty of future climate poses a challenge to structural engineers, because adaptation to climate change will require more than meeting the minimum requirements of current standards and regulations. As part of a new structural design paradigm, understanding of magnitudes and consequences of the future extremes is needed, which will be the basis for development of appropriate engineering practices and standards. Still, until these practices and standards are established, structural engineers need to apply strategies which will make building structures more resilient. This paper analyses the structural design strategies to address climate change, that is, strategies that anticipate and plan for immediate and future impacts of climate change. The present analysis pointed to the necessity of applying observational and adaptive approach to the structural design in order to respond to the changing needs in the context of future climate uncertainty.

Keywords: Climate change, Building users’ safety, Resilience-based structural design, Adaptive approach

Topics: Adaptable, resilient, and sustainable architecture

The structural engineers design building structures that should have a long service life (Orcesi et. al., 2022). One of the key aspects considered during design is related to climatic conditions. This suggest that the planning and design of new building structures should account for the climate of the future (Croce et. al., 2018). Current design standards for structural design are based on the assumptions of stationary climate conditions observed in the past. However, scientific community indicates that climate is changing, meaning that climate conditions of the past will not be representative of those of the future (Athanasopoulou et. al., 2020; Ivanov et. al., 2022; Saback et. al., 2024). Securing the users’ safety (Nenadović and Milošević, 2022)

1Corresponding author

poses a dilemma and challenge to structural engineers, because adaptation to climate change will generally require more than meeting the minimum requirements of current standards and regulations (Croce et. al., 2019; Mladenović and Ćirilović Stanković, 2020). As part of a new structural design paradigm, understanding of the magnitudes and consequences of future extremes is needed. Until new practices and standards are established, structural engineers need to apply strategies which will make building structures more resilient to future weather extremes. This paper analyses the structural design strategies to address climate change, that is, strategies that anticipate and plan for immediate and future impacts of climate change. This resilience-based structural design should reduce the impact from changing climate and hence reduce physical, social, and economic losses (Hao et.al., 2023).

The assessment of climate change, based on observations and global climate models of future weather and extreme events, indicates changes in all physical influences of importance for building structures: temperature, precipitation and wind. In the context of the above, numerous multidisciplinary research projects have recently been launched in Europe with the aim of investigating the possible effects from future climate extremes on structures. In Central and Eastern Europe, an increase in warm temperature extremes and a decrease in summer precipitation are primarily observed (Anders, 2014). Nevertheless, in some regions, regardless of the global trend of temperature growth, a larger amount of snow was observed compared to previous periods, especially in the mountainous and colder areas (Croce et. al., 2018; Ivanov et. al., 2022). The increase in snow load could have a significant impact on the structural safety, if not considered (Saback et. al., 2024). In that context, it is suggested that a European project on snow load map, taking into account the climate change implications, shall be started (Croce et. al., 2021). When it comes to thermal impacts, researchers are developing thermal design maps (Athanasopoulou et. al., 2020), taking into account the “factor of change” that uses differences between simulated current and future climate conditions derived from climate models (Croce et. al., 2021a). Climate scenarios provide an increase in the yearly maximum daily mean wind velocity and increase in extreme wind speeds (Steenbergen et. al., 2009). Also, recent studies reveal a distinct connection between the earth’s climate and its tectonic activity (Masih, 2018; Maji et.al., 2021), especially in areas that are already seismically active. An increase in seismic activity is noticeable (N1, 2024), which only complicates the problem of already observed seismic vulnerability of existing buildings in Europe (Palermo et. al., 2018). Based on the observed changes, the numerous authors emphasize the need for ad hoc strategies for future adaptation of design loads, in order to improve the climate resilience of structures and infrastructures. Also, they emphasize the necessity of improving the standards, that is, the current definition of climatic actions in structural codes (Croce et. al., 2019). The territory of Serbia is also exposed to various types of natural hazards. There has been a trend of increased air temperatures, accompanied by a redistribution of precipitation. Since the year 2000 until the end of 2023, material damages caused by the extreme weather events in Serbia have been estimated at a minimum of 6.8 billion euros, of which droughts and high temperatures are responsible for more than 70% (United Nations Serbia, 2024).

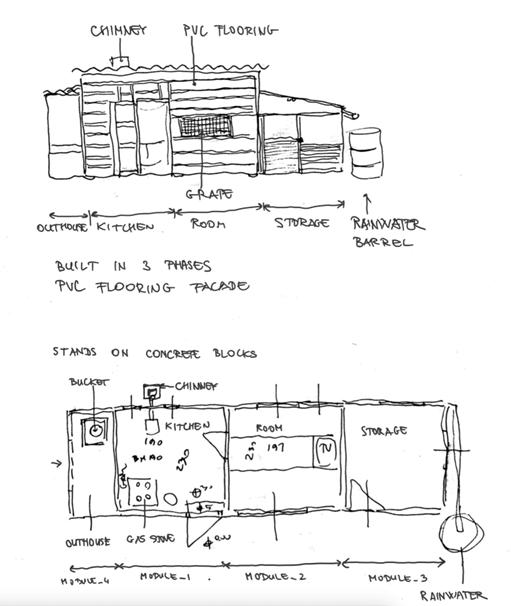

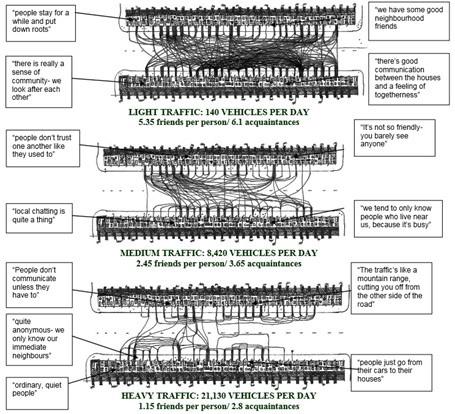

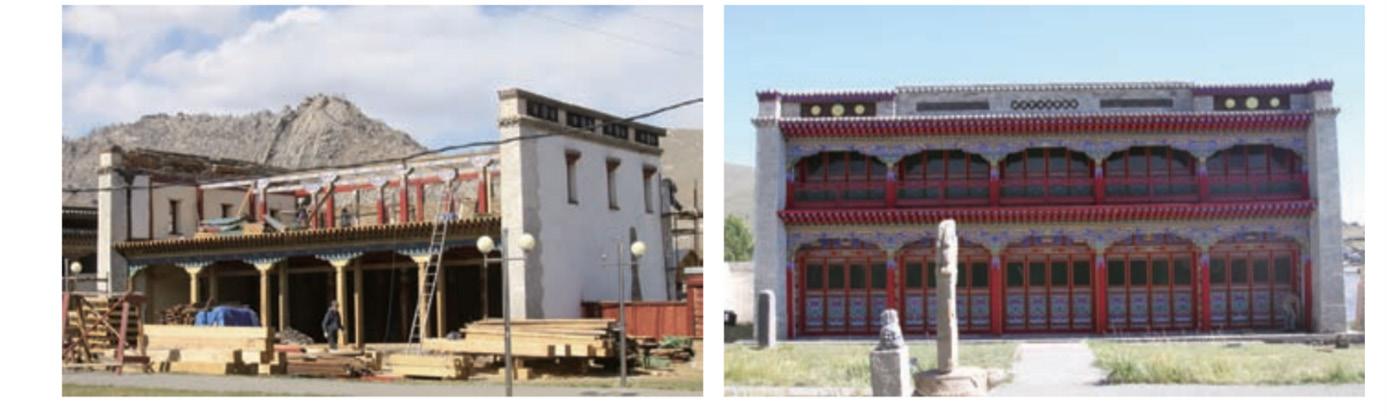

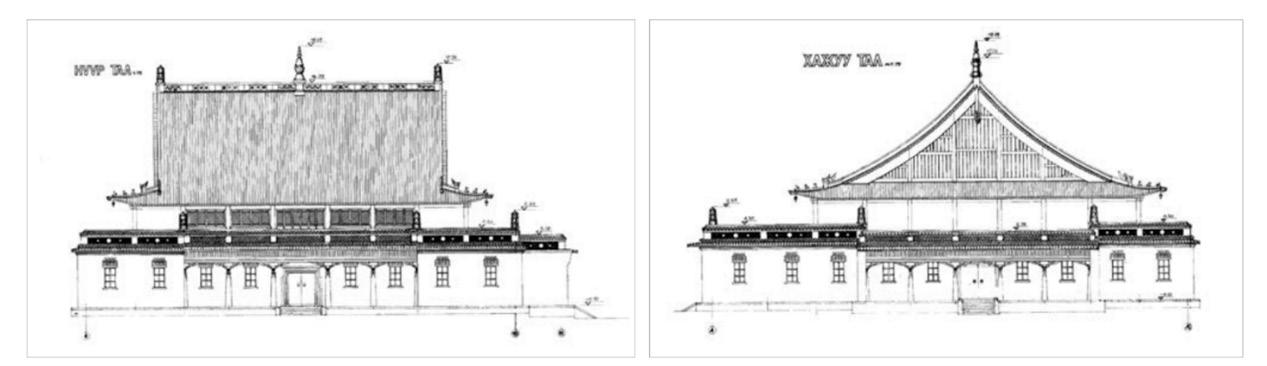

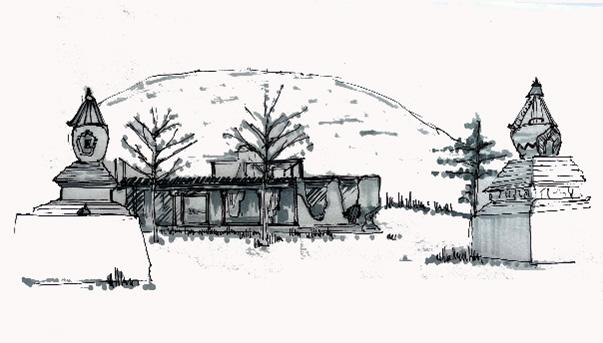

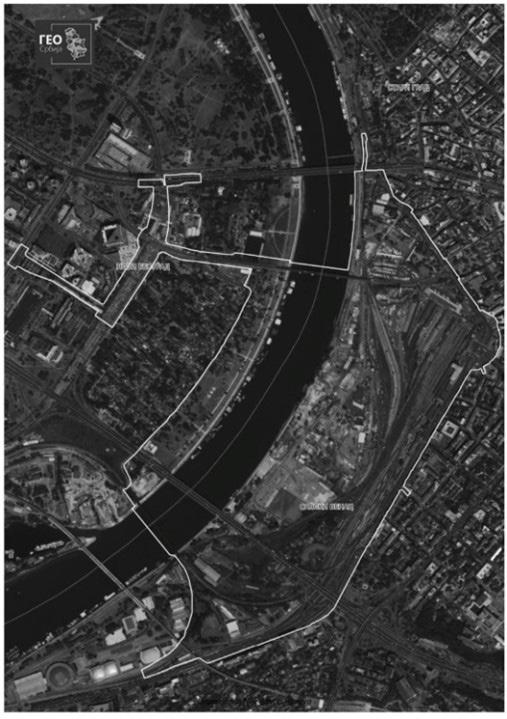

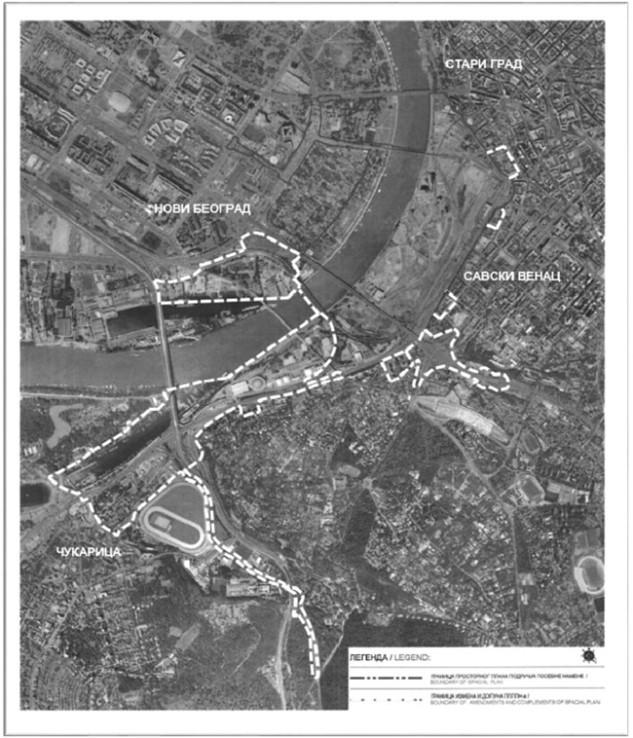

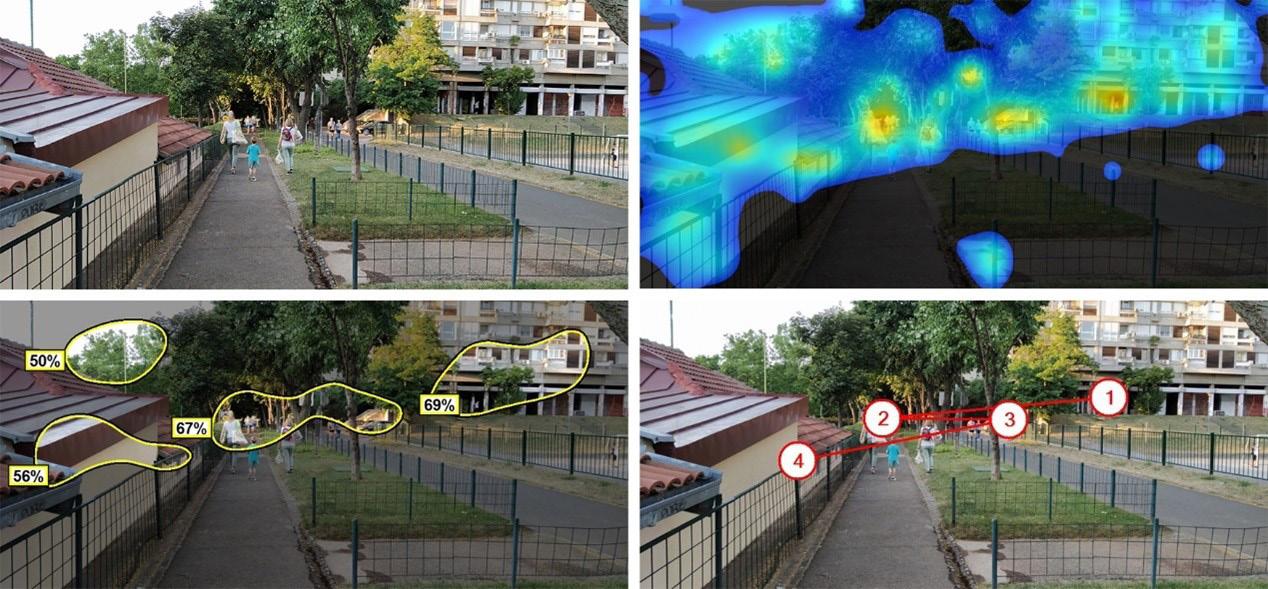

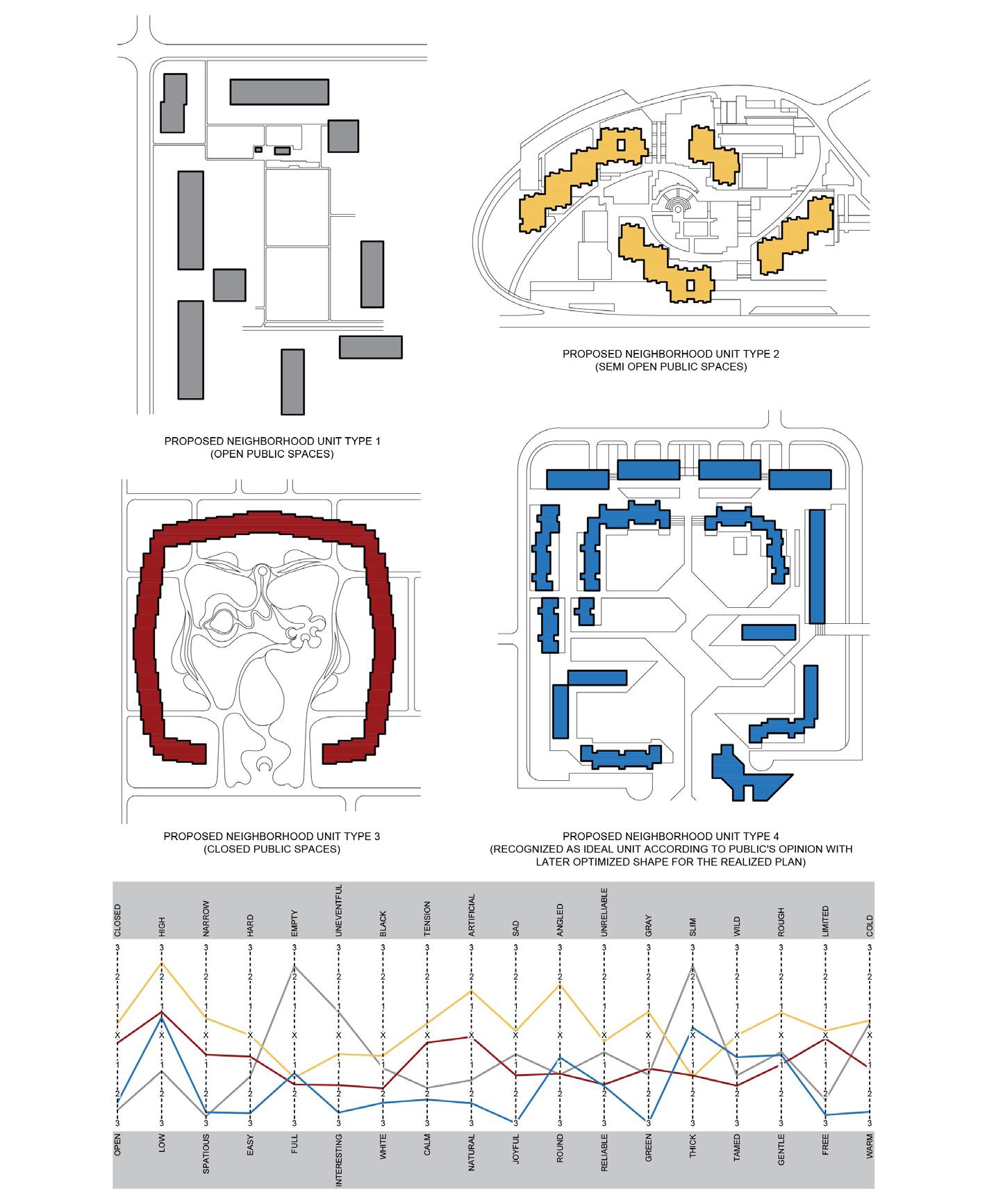

Most of engineering standards use stationarity approach which rely on historical data. This approach does not accurately reflect the future climate risk (Global Resiliency Dialogue, 2021; Croce et. al., 2018). Bearing in mind the currently significant changes in the expected loads, it is necessary to work on creation of standards for climate-resilient infrastructure (Committee on Adaptation to a Changing Climate, 2015). EU adaptation strategy also identified standards as important to guarantee the resilience to climate change of infrastructures across Europe (European Commission, 2017; CEN/CENELEC, 2022). Projects and their results, related to the improvement of standards, which is a relatively slow and extensive process, can certainly serve as guidelines for the work of structural engineers in practice. Many countries are working on changing the standards, which incorporate considerations of future climate scenarios, on a smaller or larger scale (Global Resiliency Dialogue, 2021). Within the European Union, work is being done on the second generation of Eurocodes, i.e. amendments addressing relevant impacts of future climate change. Key changes in Eurocodes, to be addressed as a revision, concern the following: actions from snow EN 1991-1-3, wind actions EN 1991-1-4, thermal actions EN 1991-1-5, actions due to atmospheric icing EN 1991-1-9 (Malakatas, 2023). The introduction of a ‘scaling factor’ for climate actions is suggested, which is more challenging for wind actions because of different storm types and less established research on different types, such as thunderstorms. There is no consideration of adaptation of exposure or durability factors as part of the Eurocodes. This should progress to ensure structural durability proportional to exposure to climatic actions (European Commission, 2017; Sousa et. al., 2020), bearing in mind that climate change causes accelerated deterioration (Sousa et. al., 2020). The research on blast resilience of structures is still in its early stage (Hao et.al., 2023). There is also increased risk of compound hazards or combined effects of different weather and climate impacts, which should be addressed (Wu et. al., 2023). Standards should provide sufficient guidance for the standard users to be able to look at more localized climate change projections to provide localized responses (CEN/TC 250/SC1.T6, 2021).