28 minute read

Manfred Kirchheimer

from PLAY-DOC 2021

by PlayDocFest

Ser un Mensch / Being a Mensch

por / by Olaf Möller

Advertisement

a desde o principio, Manfred Kirchheimer foi recoñecido como destacado cineasta. E, no entanto, ao longo dunha carreira profesional que agora facilmente abrangue seis décadas, nunca tivo valedor, nin se cultivou o estudo da súa obra, nin o seu nome acadou altos cumios, nin foi un autor cuxo último traballo se esperase sempre con ansia. Os motivos son varios e teñen que ver coa escasa frecuencia da súa produción, así como coa duración dalgunhas das súas obras, que dificultou a súa distribución ou programación dentro das estruturas convencionais. Con todo, a razón máis importante probablemente radique en que o cinema de Kirchheimer nunca estivo de moda no tocante ao estilo. Cando en 1963 fixo o seu debut con Colossus on the River, causaba furor o cinema directo; unha estética e unha política de imaxes e sons que a el non lle daban esperanza ningunha. Para expresalo con termos lixeiramente polémicos: o cinema directo trata

X R ight from the start, Manfred Kirchheimer was recognized as a major filmmaker – and yet, over the course of a career now easily six decades long, he got never championed, cultivated, turned into a name, an auteur whose latest work was always eagerly awaited. The reasons for this are several and have to do with the infrequency of his output as well as some works’ length, which made them difficult to distribute or program inside conventional structures. Yet the probably most important one is that Kirchheimer’s cinema was never fashionable in terms of style. When he debuted with Colossus on the River in 1963, direct cinema was all the rage – an aesthetic as well as politic of images and sounds that never held any promise for him. If one wants to put it in slightly polemical terms: direct cinema is all about society as spectacle, a liberal-minded play whose outcome might change from time to time but not the rules – while for Kirchheimer, human endeavour, mankind itself

por enteiro da sociedade como espectáculo, un xogo de mentalidade liberal cuxo resultado pode variar de cando en vez, pero non as regras, mentres que para Kirchheimer os afáns humanos, a humanidade en si mesma, non son senón pasaxeiros, como pode verse, por certo, en Claw. A Fable (1968) ou Up the Lazy River (2020), por exemplo. Nova York móstrase case nun proceso de crecemento que transforma os bosques primixenios nunha «cidade situada na cima dun monte», cuxo futuro como ruína invadida polas herbas, os fentos e as árbores xa resulta visible para o ollo dun observador curioso. A referencia bíblica é acaída, pois a Kirchheimer encántalle amosar a arquitectura máis antiga de Nova York dunha forma que subliñe as súas semellanzas con esas catedrais góticas habitadas por infinidade de gárgolas, recordatorios todas elas da invariable natureza da gloria e a miseria humanas para aqueles que lle presten atención ao seu pétreo silencio omnisciente.

A Kirchheimer encántalle a grandiosidade, talvez porque a crean eses diminutos seres chamados humanos. Colossus on the River constitúe case un ensaio sobre esa particular relación: o SS United States —o meirande transatlántico construído nos EUA, así como o buque máis rápido do mundo entre os da súa clase— entra no porto de Nova York guiado polas manobras dun piloto que está ao mando dunha presa de remolcadores. O contraste resulta asombroso: un home capaz de ler a linguaxe das nubes e as ondas dirixe un feixe de pequenas embarcacións para elas efectuaren movementos minúsculos, con precaución pero tamén con decisión, que van salvagardar a seguridade e a integridade dun Behemot de aceiro e dos miles de persoas que fixeron del o seu fogar temporal, e todo isto baixo a mirada vixiante do seu pai intelectual, o arquitecto naval William Francis Gibb, quen, segundo afirman as crónicas, sempre está aí cando o barco chega á casa. A arribada dun buque de pasaxeiros despois dunha travesía atlántica aínda constituía unha vista que aos neoiorquinos daquela altura lles parecía bastante normal; e, porén, xa as vían vir: tal modo de viaxar non vai ser propio deste mundo durante moito máis tempo. Seis anos despois de se facer a película, o SS United States foi retirado do servizo tras a súa cuadrinxentésima travesía. Para entón, os viaxes por aire tomaran a remuda. É difícil non ler significados máis profundos en todo isto, como pode is but fleeting, as can be witnessed, by the way, in e.g. Claw. A Fable (1968) or Up the Lazy River (2020). New York is shown as almost growing from primeval forests to a City on a Hill whose future as a ruin overgrown with grasses, ferns and trees is already visible to the curious eye. The biblical reference is apt as Kirchheimer loves to show the older architecture of New York in a way that stresses its similarities with Gothic cathedrals inhabited by gargoyles galore – reminders of the unchanging nature of human glory and misery to those who pay attention to their all-knowing stony silence. Kirchheimer loves grandeur, maybe because it’s created by those tiny beings called humans. Colossus on the River is almost an essay on that particular relationship: the SS United States – the biggest ocean liner built in the USA as well as the fastest ship in the world of its kind – is manoeuvred into New York Harbour by a pilot commanding a handful of tugboats. The contrast is staggering: one man able to read the language of clouds and waves directs a bunch of small vessels to do cautious yet decisive minuscule movements that will protect the safety and integrity of a steel behemoth and the thousands that made it their temporary home – all under the watchful eyes of its intellectual father, naval architect William Francis Gibbs, who, the commentary claims, is always there when the ship arrives home. An ocean liner coming in from an Atlantic crossing was still a rather ordinary sight to New Yorkers of the time – and yet, the writing was on the wall: this mode of travelling won’t be too long any more for this world. Six years after the film was made, the SS United States got withdrawn from service after its 400th journey – air travel had taken over by then. It’s difficult to not read any deeper meanings into all this, including the demise of American power and influence in the world – towards the end of ‘63, President Kennedy will be assassinated, while the war in Vietnam escalates and escalates. The film’s maybe most overwhelming shot shows a Black sailor against the gigantic Stars and Stripes floating in the wind – a last salute to an empire collapsing. Did Kirchheimer arrive in the United States on a ship like the SS United States? After his birth in Saarbrücken in 1931, his family left the German Reich in 1936, when it became only too clear how serious the ruling Nazi party was about its

ser o colapso do poder e a influencia dos EUA no mundo: cara a finais de 1963, o presidente Kennedy será obxecto dun magnicidio, en tanto que a guerra de Vietnam se recrúa sen cesar. A que talvez constitúa a toma máis impoñente da película mostra un mariñeiro negro recortándose contra unha xigantesca bandeira de barras e estrelas que ondea ao vento: un último saúdo a un imperio que se derruba. Chegou Kirchheimer aos Estados Unidos a bordo dun buque como o SS United States? Tras o seu nacemento en Saarbrücken en 1931, a súa familia abandonou o Reich alemán en 1936, cando ficou patente, e como, o moi en serio que tomaba o partido dirixente, o nazi, a súa política de sometemento dos cidadáns xudeus da nación, a saber: os pavillóns de exterminio. Tamén as vían vir? Así foi como os Kirchheimer fixeron de Nova York o seu fogar. Canto de Saarbrücken seguiu vivo en Manfred Kirchheimer? Canto lembra el dos seus primeiros anos nese outro país? En Nova York Kirchheimer asistiu á escola e despois tamén á universidade, onde o seu mentor foi outro refuxiado alemán: o pioneiro do dadaísmo e axioma da animación abstracta Hans Richter, quen fundou o Institute of Film Techniques (Instituto de Técnicas Cinematográficas) do City College. Se ben Richter constituíu, sen dúbida, unha figura de relevancia para Kirchheimer, porque foi el quen o encamiñou, a experiencia práctica que adquiriu traballando con Leo Hurwitz na década de 1960 probablemente resultase máis importante para o seu exercer cinematográfico. De certo, o Essay on Death: A Memorial to John F. Kennedy (1964) de Hurwitz reflicte unha fonda afinidade entre ambos na maneira en que se amosa e se dramatiza a natureza, e en como se subliña a evanescencia da vida mediante a presenza de formas gargolescas e obras de arte como a escultura de 1953 Variacións nunha esfera, núm. 10: o sol, de Richard Lippold, aos que lles dedicarían un filme propio dous anos despois. Eles, como corresponsables, figuran entre ducias de persoas máis, na súa maioría destacadas figuras da vangarda, na longa nómina de contribuíntes ao monumento de propaganda política For Life, Against the War, de 1967. Ao ano seguinte tería lugar a estrea de Claw. A Fable (codirector: Walter Hess), a cinta que consolidaría o modo de expresión máis celebrado de Kirchheimer: a coreografía sinfónica de imaxes e sons, que tamén caracteriza Bridge High (1975; policies subjugating the nation’s Jewish citizenry – extermination wards. Was that writing also on the wall? Thus, the Kirchheimers made New York their new home. How much of Saarbrücken did stay with Manfred Kirchheimer, how much does he remember of his first years in that other country? Kirchheimer went to school in New York, and then to university there as well, where his mentor was another German émigré: Dada pioneer and abstract animation axiom Hans Richter, who founded the City College’s Institute of Film Techniques. While Richter was certainly of significance for Kirchheimer as he put him on his tracks, the practical experience he gained from working with Leo Hurwitz in the 60s was probably more important for his filmmaking practice. Hurwitz’ Essay on Death: A Memorial to John F. Kennedy (1964) certainly shows a deep kinship between the two in the way nature is shown and dramatized, and how the evanescence of life gets stressed by the presence of gargoylesque shapes as well as artworks like Richard Lippold’s 1953 sculpture Variations within a Sphere, #10: The Sun, to whom and which they’d dedicate a film of its own two years on. Playing a co-responsible role, they appear among dozens of others, avantgarde luminaries mostly, on the long contributors' roll call for the 1967 agitprop monument For Life, Against the War.

The following year would see to the release of Claw. A Fable (co-director: Walter Hess), the film to establish the Kirchheimer mode of expression most widely celebrated: the symphonic choreography of images and sounds, which also characterizes Bridge High (1975; co-director: Walter Hess), Stations of the Elevated (1980), in some chapters Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan (2004) and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution (2012), and then again the whole and all of Dreams of a City (2018), Free Time (2019), Up the Lazy River and One More Time (2021), the latter four made in good parts using material from his earlier films and shoots. Kirchheimer establishes himself here as a heir to the likes of Walter Ruttmann, Albrecht Viktor Blum or the Kaufman family in its aesthetic diversity – while going one or two steps further than all of them by making time, considered at an epic scale, the subject of his montages, which sometimes takes the shape of the above-described movement from the antediluvian to the high modern, then

codirector: Walter Hess), Stations of the Elevated (1980), algúns capítulos de Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan (2004) e Art Is… The Permanent Revolution (2012), e máis adiante, outra vez, a totalidade de Dreams of a City (2018), Free Time (2019), Up the Lazy River e One More Time (2021), das cales as catro últimas se realizaron, en boa medida, con material procedente dos seus primeiros traballos e tomas. Aquí Kirchheimer establécese como herdeiro de nomes como Walter Ruttmann, Albrecht Viktor Blum ou a familia Kaufman na súa diversidade estética, e simultaneamente vai un ou dous pasos por diante de todos eles ao converter o tempo, considerado a escala épica, no obxecto das súas montaxes, que por veces adopta a forma do movemento, antes descrito, que decorre do antediluviano á alta modernidade e que outras veces cristaliza en algo tan básico pero fundamental como os trens cubertos de pintadas que avanzan pola vasteza urbana como signos dos tempos que están por chegar. Neste punto, literalmente, un veas vir. Nas súas obras máis recentes, o tempo como obxecto está arraigado na textura das propias imaxes, igual que nas modas das épocas ou nos edificios que agora un sabe que xa son cousa do pasado. Esta modalidade, cunhas paisaxes sonoras coidadosamente elaboradas e unha imaxinería espectacular que mostra con orgullo a fascinación de Kirchheimer pola gloria gráfica da arte impresa, é o que máis se achega ao que se denomina cinema puro. Dito isto, podería afirmarse que as obras máis ricas de Kirchheimer son as de maior complexidade formal, o cal sempre significa que, nalgunha medida, efectivamente empregan a linguaxe de maneira fértil e evocadora, empezando por Colossus on the River, seguindo co seu magnum opus We Were So Beloved (1986) e chegando por fin a Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan e Art Is… The Permanent Revolution. Pero atención: estas non son as únicas cintas do autor nas que se traballa coas palabras. Así, Daughters (2020), por exemplo, non está constituída por case máis nada que palabras, mentres que a súa solitaria incursión na ficción, Short Circuit (1973), posúe moito diálogo, aínda que vaia encamiñado cara a unha longa secuencia de montaxe que ten lugar na mente do protagonista e na que se recorre case exclusivamente a sons e imaxes para insinuar unhas preocupacións e unha paranoia que van en aumento: o seu racismo burgués. othertimes crystallizes into something so basic yet fundamental as the sprayed trains moving through the urban vastness as signs of the times to come – the writing is here quite literally on the walls; in his most recent works, time as a subject is ingrained in the textures of the images themselves, just as it is in the fashions of the days or the buildings one now knows to be gone. This mode, with its carefully created soundscapes and dramatic imagery that proudly shows Kirchheimer’s fascination with the graphic glory of printing art, is closest to what one calls pure cinema. That said: Kirchheimer’s arguably richest works are the formally more complex ones, which always means that to some degree they do use language in a rich and evocative way, starting with Colossus on the River, then his magnum opus We Were So Beloved (1986) to finally Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution. Mind that these aren’t his only films to work with words – Daughters (2020), e.g., is almost only words, while his lone foray into fiction, Short Circuit (1973), has a lot of dialogue even if it’s headed towards a long montage sequence in the protagonist’s head that uses almost exclusively sounds and images to suggest his growing anxieties and paranoia – his bourgeois racism. Which connects it uneasily yet intimately with We Were So Beloved, a portrayal of the Jewish émigré community in Washington Heights at the far end of Manhattan – the world of Kirchheimer’s family, whose memories and opinions form the film’s core. Almost everybody here has lost next of kin to the Nazi death machine; some even survived being deported into an extermination camp. But as Kirchheimer has to find out: having escaped one of the 20th century’s worst atrocities didn’t humble everybody into a better human being – prejudices, e.g., are still there, with the Blacks of neighbouring Harlem getting sometimes perceived in ways not too dissimilar from that of the Polish and Russian (later Soviet) Jews back in Germany during the 10s, 20s, 30s: backwards and/or poor, in that a threat to their own position in society, the way they (still) feel perceived by the goyim majority. In many ways they remained who they always were – history barely touched them. And as Short Circuit, which can be read as a tacit portray in grey and black of Kirchheimer himself, brutally suggests: even trying to bridge

O cal a conecta, de forma precaria pero íntima, con We Were So Beloved, retrato da comunidade de refuxiados xudeus de Washington Heights, no extremo de Manhattan; o mundo da familia de Kirchheimer, cuxas lembranzas e pareceres constitúen o núcleo da cinta. Aquí case todos perderon algún parente a mans da máquina nazi da morte; algúns mesmo sobreviviron á deportación a un campo de exterminio. Pero, como Kirchheimer ten que descubrir, escapar a unha das maiores atrocidades do século XX non lle deu a todo o mundo unha lección de humildade que o fixese mellor ser humano: os prexuízos, por exemplo, seguen aí, e os negros do veciño Harlem por veces son percibidos dun xeito non moi distinto de como se vía en Alemaña aos xudeus polacos e rusos (despois soviéticos) durante as décadas de 1910, 1920 e 1930: atrasados, pobres ou ambas as cousas, e por iso mesmo unha ameaza á súa propia posición na sociedade, é como senten (aínda) que os percibe a maioría dos goyim. En moitos sentidos, seguen a ser os que sempre foron; a historia apenas os tocou. E, como apunta con brutalidade Short Circuit, que pode interpretarse como un retrato tácito, en gris e negro, do propio Kirchheimer: mesmo o intento de salvar a fenda, o intento de superar as divisións de clase e raza, pode ser percibido como algo condescendente por aqueles que tal intentan. O único que lle queda a un por facer é apuntarse aos actos de solidariedade e apoio e engulir a escuridade que leva dentro, íntegra e completamente, xa que, ao cabo, esta non é máis que outra forma de autoodio e autocompaixón, e tamén de orgullo, emocións que nunca axudaron a ninguén. Encaixa, pois, que Kirchheimer non descubrise ata acabar We Were So Beloved que algunhas cousas eran máis complicadas do que contaban os seus entrevistados. Nunha escena que se ten citado con moita frecuencia, o seu pai di que probablemente non lle salvaría a vida a ninguén, porque se tiña por covarde; non foi ata máis adiante cando Kirchheimer chegou a saber que o seu proxenitor si lle dera refuxio para pasar a noite a outro xudeu escapado, e obviamente coidaba que aquilo non fora nada, o que dá unha idea do que significaba o valor para este home en concreto: moito. Advírtase que Kirchheimer nunca fai un Lanzmann ou un Ophüls á hora de presentar a súa familia en particular e a comunidade de Washington Heights en xeral: poida que lles dea voz ás súas propias opinións e pensamentos, e cara ao final da cinta, en the gap, trying to overcome divides of class and race, can be perceived as condescending by those who try. The only thing that remains to do is to go with the acts of solidarity and support, and to swallow the darkness inside wholly and totally, for in the end, this is also only another form of selfloathing and -pity, and also pride – emotions that never helped anybody. It thus fits that Kirchheimer found out only after finishing We Were So Beloved that some things were more complicated than his interviewees let on. In a very often quoted scene, his father says that he’d probably not have saved anybody, for he thought of himself as a coward; only later did Kirchheimer learn that his father did shelter a fellow Jew on the run for a night; obviously he thought this was nothing – which gives an idea of what courage meant to this one man: a lot. Mind that Kirchheimer never goes Lanzmann or Ophüls in the way he presents his family in particular and the Washington Heights community in general: he might voice his opinions and thoughts, and towards the end of the film certainly summarizes his insights, but he’s never overtly judgemental – while he might sense some capital-t truths he’s too humble and generous, too much a Mensch to condemn others. And while he voices his disdain for all the Germans who collaborated with the Nazis if only through their passivity, he lets several US Americans his own age talk about this country’s history of persecutions, and how its citizens too often failed under far less terrorizing circumstances. Humans are mainly weak – and yet, as a collective they can very well defy their insignificance to create culture and progress, grow together beyond the boundaries of one, claim dominion over realms of the spirit and the soul their forefathers often would not have been able to conceive. On a formal level Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan and Art Is… The Permanent Revolution might be the more refined, multi-layered and ever-surprising achievements of Manfred Kirchheimer – but when it comes to the human spirit, few ever saw more greatness in it than he did in We Were So Beloved.

efecto, resume as súas apreciacións, pero nunca adopta unha actitude abertamente sentenciosa. Aínda que poida detectar algunhas verdades con maiúscula, é demasiado humilde e xeneroso, demasiado Mensch, para condenar os demais. E, ao tempo que expresa o seu desdén por todos os alemáns que colaboraron cos nazis, aínda que fose só coa súa pasividade, deixa falar varios estadounidenses da súa mesma idade verbo da historia de persecucións que ten este país, e de como os seus cidadáns, demasiado a miúdo, non estiveron á altura en circunstancias moito menos terroríficas.

Os humanos son maiormente débiles; e, con todo, en canto colectivo moi ben poden desafiar a súa insignificancia para crearen cultura e progreso, para creceren alén das fronteiras do un, para afirmaren un dominio sobre os territorios do espírito e da alma que os seus entregos a miúdo serían incapaces de concibir. Na escala formal, Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan e Art Is… The Permanent Revolution poderían constituír uns logros máis refinados, dotados de múltiples camadas e sempre sorprendentes, pero, cando se trata do espírito humano, poucos viron nunca nel máis grandeza que este autor en We Were So Beloved.

COLOSSUS ON THE RIVER

15′ / 1965 / EUA Sala 1 mércores Wednesday ás 20:30 h Sala 1 sábado Saturday ás 16:30 h As mareas, os cambios de vento e as contracorrentes converten o amarre dun xigantesco transatlántico nunha serie de complicadas manobras. Esta película, dotada dun entusiasmo desbordante, mostra a destreza e a delicadeza necesarias para atracar o lendario buque mercante SS United States no porto da cidade de Nova York. The tides, shifting winds, and cross-currents in New York harbor, make the docking of a huge ocean-going liner a series of tricky maneuvers. This exuberant film shows the skill and delicacy required in berthing the legendary ocean liner SS United States.

CLAW

30′ / 1968 / EUA Sala 1 sábado Saturday ás 16:30 h Mentres unha máquina terrorífica derruba edificios ata reducilos a entullos, este documental poético examina os efectos negativos da renovación e a demolición urbanas. Nas construcións antigas, os relevos de pedra de aparencia humana observan como a cidade é alterada por estas grandes máquinas, que acabarán por destruílos tamén a eles. As a terrifying machine demolishes buildings to rubble, Claw, bores into the ill effects of urban renewal and destruction. In this lyrical documentary, the human-like stone reliefs on older buildings watch the city being altered by the great machines which will finally destroy them, too.

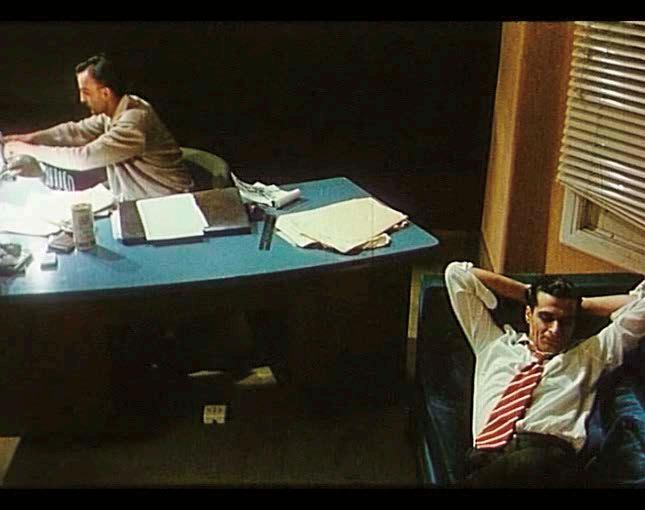

SHORT CIRCUIT

45′ / 1973 / EUA Sala 2 xoves Thursday ás 17:30 h No seu apartamento, na esquina da rúa 101 e Broadway, un cineasta comeza a cuestionarse as interaccións entre a familia branca e os empregados negros cos que se relaciona día a día. Esta inclasificable obra mestra, a única película seminarrativa de Kirchheimer, debería estar considerada como un filme de referencia por dereito propio, se non fose porque desde que se realizou foi practicamente imposible vela. Kirchheimer’s only seminarrative film. In his apartment on the corner of 101st Street and Broadway, a documentary filmmaker begins to question his interactions to the white family and black workers he shares his daily existence with. Constructed reality and documentary fiction, an unclassifiable masterpiece of ideas and technique that by all rights should be considered a landmark, had it not been virtually impossible to see.

BRIDGE HIGH

10′ / 1975 / EUA Sala 1 sábado Saturday ás 16:30 h Bridge High é unha pasaxe evocadora a través dunha ponte colgante. Indo desde o campo cara á cidade, esta película expande o minuto e medio que se tarda en atravesar a ponte en coche, converténdoo nunha viaxe de nove minutos e medio; unha danza eufórica, unha coreografía de vigas, cables e arcos. Bridge High is an evocative passage across a suspension bridge. Moving from the country to the city, the film expands the half minute it takes a car to cross, into a nine-and-a-half minute trip, choreographing cables, girders and arches into an exuberant dance.

STATIONS OF THE ELEVATED

45′ / 1981 / EUA Sala 1 sábado Saturday ás 22:30 h Stations of the Elevated é unha sinfonía urbana de 45 minutos, dirixida, producida e editada por Manfred Kirchheimer. Filmado en suntuosa película de 16 mm reversible, este filme mestura vívidas imaxes de trens cubertos de graffiti atravesando a áspera paisaxe da Nova York dos setenta cunha banda sonora que combina os ruídos da cidade co jazz e o gospel de Charles Mingus e Aretha Franklin. Deslizándose entre o South Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens e Manhattan —facendo un desvío polo penal do norte do estado—, Stations of the Elevated é un retrato impresionista dunha Nova York desaparecida hai xa moito tempo á que se lle rende homenaxe. Stations of the Elevated is a 45-minute city symphony directed, produced and edited by Manfred Kirchheimer. Shot on lush 16mm color reversal stock, the film weaves together vivid images of graffiti- covered elevated subway trains crisscrossing the gritty urban landscape of 1970s New York, to a commentary-free soundtrack that combines ambient city noise with jazz and gospel by Charles Mingus and Aretha Franklin. Gliding through the South Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan – making a rural detour past a correctional facility upstate – Stations of the Elevated is an impressionistic portrait of and tribute to a New York that has long since disappeared.

WE WERE SO BELOVED

145′ / 1986 / EUA Sala 1 venres Tuesday ás 16:00 h Entre 1933 e 1941 miles de xudeus procedentes de Alemaña e Austria fuxiron do nazismo e instaláronse nos Estados Unidos. Máis de 20.000 deles reuníronse no barrio de Washington Heights da cidade de Nova York, deixando atrás irmáns, irmás, pais e nais. Washington Heights converteuse así nunha comunidade de xudeus alemáns que os seus habitantes alcumaron o Cuarto Reich ou o Frankfurt do Hudson. We Were So Beloved indaga nas consecuencias emocionais e filosóficas desta comunidade, resultado da súa condición de sobreviventes. Between 1933 and 1941 thousands of Jews from Germany and Austria fled to America. Leaving behind brothers, sisters and parents, more than 20,000 of them came together in Washington Heights in New York City. It became a German Jewish enclave dubbed by the Americans who lived there, “The Fourth Reich” or “Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson." The film probes the emotional and philosophical outcome of their survival.

TALL: THE AMERICAN SKYSCRAPER AND LOUIS SULLIVAN

80′ / 2006 / EUA Sala 1 xoves Thursday ás 22:30 h Tall é a historia do ascenso imparable dos rañaceos que comeza en 1869, nas cidades de Nova York e Chicago. Ascensores, aceiro e electricidade combínanse para crear un frenesí de edificios cada vez máis altos. Rivais irreconciliables compiten por favores, diñeiro e poder. O enfrontamento definitivo entre os arquitectos Louis Sullivan e Daniel Burnham —entre a integridade e a vivenda— cambiará o futuro para sempre, moldeando o horizonte das cidades modernas do mundo. Tall is the story of the unstoppable rise of the skyscraper. Starting in 1869, in New York and Chicago, elevators, steel, and electricity combined to create a frenzy of tall and taller buildings. Fierce rivals competed for favor, money and power. The ultimate showdown between the Chicago architects Louis Sullivan and Daniel Burnham – between integrity and accomodation – changed the future, shaping the modern skyline throughout the world

DREAM OF A CITY

38′ / 2018 / EUA Sala 2 xoves Thursday ás 17:30 h Esta sorprendente película está composta por fascinantes imaxes en branco e negro de lugares de obras, da vida na cidade e do tráfico portuario. Filmada por Kirchheimer e o seu vello amigo Walter Hess entre 1958 e 1960 e con música de Shostakovich e Debussy, Dream of a City é como un sinal precioso e caprichoso recibido sesenta anos despois da súa transmisión. This astonishing new film, comprised of stunning black and white 16mm images of construction sites and street life and harbor traffic shot by Kirchheimer and his old friend Walter Hess from 1958 to 1960, and set to Shostakovich and Debussy, is like a precious, wayward signal received 60 years after transmission.

FREE TIME

60′ / 2019 / EUA Sala 2 domingo Sunday ás 19:30 h Free Time é un canto a aqueles tempos pasados máis sinxelos, aos fermosos barrios de outrora da cidade de Nova York e á forma en que as persoas adoitaban pasar o seu tempo libre. An hour-long paean to simpler days, to the beautiful neighborhoods of the New York City of yesteryear, and to the way we used to spend our time.

ONE MORE TIME

16′ /2021 / EUA Sala 1 mércores Wednesday ás 22:30 h Coda ao tríptico que ofrece unha gloriosa mirada final ao singular arquivo de secuencias rodadas ao longo de décadas na cidade de Nova York e os seus arredores. Unha combinación de imaxes en branco e negro e en cor, ningunha delas vista ata agora, que datan da época das primeiras tomas do autor e chegan ata Stations of the Elevated. A intercalación dos materiais, separados entre si por varios anos, non só serve de comparación entre a Nova York de antes e a de agora, senón que tamén constitúe un recordo asociativo libre que é típico de calquera que pasase a vida andando polas mesmas rúas, vendo cambiar o mundo ao seu ao redor e atopándose con que cada esquina e cada edificio tráenlle á memoria algo que tiña medio esquecido. A coda to the triptych, providing a final, glorious look at the singular archive of footage shot over decades in and around New York City. A combination of black and white and color footage, all never before seen, dating from the earliest shoots through Stations of the Elevated. The intercutting of material, separated by years, provide not only a comparison between New York then and now, but a free associative recollection of anyone who has spent their life walking down the same streets, seeing the world change around you, every corner and building reminding you of a halfforgotten memory.

UP THE LAZY RIVER

31′ / 2021 / EUA Sala 1 mércores Wednesday ás 22:30 h Elaborada a partir da interminable serie de imaxes que Kirchheimer e Walter Hess filmaron nunha Bolex en 16 mm, Up the Lazy River é a conclusión do tríptico iniciado con Dream of a City e Free Time. A cinta está chea de motivos que Kirchheimer fixo seus: a cámara que se despraza maxestosa entre os edificios, apuntando ao ceo, coa luz a reflectirse nos vidros, filmando a fronte dos establecementos comerciais e a vida diaria segundo percorre as rúas, sempre cunha abraiante capacidade que lle permite captar pequenos momentos entre veciños e as faces dunha metrópole, para chegar á súa culminación co extático son de Louis Prima e os tranquilos sons do río. Miren con atención: alcanzarán mesmo a ver fugazmente o propio Manny. Crafted from the endless wealth of images filmed in 16mm on a Bolex by Kirchheimer and Walter Hess, Up the Lazy River is the conclusion of the triptych begun with Dream of a City and Free Time. The film is filled with motifs that Kirchheimer has made his own: the camera traveling majestically through building, pointing skyward, light reflecting off glass, sweeping through the streets filming storefronts and daily life, always with an uncanny ability to capture small moments between neighbors, and the faces of a metropolis, culminating to the ecstatic sound of Louis Prima and the peaceful sounds of the river. Look close: you will even catch a glimpse of Manny himself.