Designing Public Spaces to Promote Intergenerational Play & Recreation

©2021 PlayCore Wisconsin, Inc.

All rights reserved. The purpose of Transformational Impact™ is to provide an educational overview and is not to be considered as an all-inclusive resource. Please refer to manufacturer specifications and safety warnings for all equipment. While our intent is to provide a general resource to encourage communities to design and program public spaces for an intergenerational audience, the authors, partners, program directors, and contributors disclaim any liability based on information contained in this publication. Site managers are responsible to inspect, maintain, repair, and manage site-specific elements. PlayCore and its brands provide these comments as a public service in the interest of building healthier communities through play and recreation, while advising of the restricted context in which it is shared.

Combat Loneliness

Promote Social Capital

Bridge the Racial Generation Gap

Extend Lifespans

Expand Richer Everyday Experiences

Promote Respect

Promote Cultural Diversity

Expand Local and Public Services

Develop Educational/Learning Opportunities

Break Down Barriers and Stereotypes

Promote Social/Emotional Health and Wellness

Build Equity by Sharing Cultural History and Identity

The world’s population is changing. The global population aged 60 years or over numbered 962 million in 2017, more than twice as large as in 1980 when there were 382 million older persons worldwide. The number of older persons is expected to double again by 2050, when it is projected to reach nearly 2.1 billion.1 Accordingly, interest in using intergenerational strategies to create relevant community programs and social policy is growing.2 Most relative to this growth is the understanding that our civil society is based on the giving and receiving of resources across the lifespan, and understanding that intergenerational relationships promote the greater good of society.

In times past, older generations were much more involved with younger people, and vice versa. But times change, and that isn’t as much the case with today’s society for a number of reasons. Non-profit groups Generations United and The Eisner Foundation published a study titled “I Need You, You Need Me: The Young, The Old, and What We Can Achieve Together” in which all surveyed admitted we live in an age-segregated society. In this study,3 53% of American adults say that they don’t regularly spend time with individuals much older or younger than they are, outside of their family. Parents are having children later in life, and living greater distances from their own parents. Lives are busier and more scheduled as many households have two working parents and children with a busy calendar of extracurricular activities. Young people are more apt to move to new cities and/or states for meaningful work. A large number of people, including older people themselves, see social disengagement among older people with young people as a natural part of aging. There may also be differences in physical and cognitive functioning between different age groups, which leads to the occupying of separate physical spaces and different activities.4

Additionally, age-segregated institutions are growing and housing centers for older people are often set apart from where younger generations live, and in fact can be entire small townships unto themselves, often in warmer climates, causing older people to move away from family resources in order to live in one of these communities. Funding streams and service delivery systems create silos that limit our ability to work together and encourage competition for scarce resources. Perceptions of older adults and youth as problems may prevent us from mobilizing these groups as valuable resources who can support each other and contribute to their communities.5

All these things can drive a wedge between generations and cause people across a variety of ages to miss out on time together. Along with a poorer understanding and awareness of each other, it’s a downward spiral where negative stereotypes and attitudes can take hold too easily, and valuable opportunities for learning and social exchanges are lost.

Some causes for intergenerational separation include:

• Parents having children later in life

• People living greater distances from their parents

• Busy, over-scheduled lives

• Young adults move to new cities to find work

• Social disengagement being viewed as a natural part of aging

• Differences in physical and cognitive functioning

• Growth of age-segregated housing and institutions

• Funding streams and service delivery systems encourage competition for resources

• Perceptions of older adults and youth as problems

Social contact is good for people. While people tend to gather with those closest to their age group, there are symbiotic opportunities with intergenerational friendships and activities. Adults may have more chances to share knowledge and resources with younger generations, and as they continue to age, they are also more likely to depend on the support of younger generations for transportation and other basic needs. While there are many shared issues that are relevant to all people, they may be experienced in different ways depending on the generation. Intergenerational activities, in the form of social engagements and interactions, bring together younger and older generations for a common purpose. They build on the strengths that different generations have to offer, nurture understanding and mutual respect,

and challenge the stereotypes of ageism. All parties have the opportunity to give as well as receive, and to feel a sense of ownership and achievement. Research has shown that amongst the oldest generations, social contact with non-family members has a greater impact on their mental well-being than their health status.6

Age segregation and stereotypes build silos between generations and prevent us from mobilizing these groups as valuable resources that can help build communities. So how do we promote contact between generations for the common good? How can we strengthen social relations to reflect a commitment to one another? Intergenerational play and recreation have a multitude of benefits to foster inclusion, and bring people together to improve life for people of all ages. In fact, various stakeholders have for some years been concerned with improving relations between the generations at the societal level. Two broad approaches can be identified: first, the creation of ‘inclusive’ spaces, environments, activities and cultures that provide a platform for strong intergenerational relations; second, the deliberate exposure of groups and organizations from different generations for the purpose of improved intergenerational understanding, empathy, and exchange.7

Multigenerational simply refers to a composition — people from different generations are present. Intergenerational refers to an active exchange or connection between and among the generations, and this is where there is a great opportunity to enrich both people and the environment, while promoting a wealth of positive benefits for all.

People of all ages benefit from the increased physical activity, access to vitamin D, fresh air, and reduction of health risk factors associated with outdoor activity.8 For children, play can provide positive impact across all five developmental domains: physical, social-emotional, sensory, cognitive, and communicative.9 Being in an outdoor environment helps people relax, and can help to restore the mind from specific age-related stresses such as school, work, family pressures, or loneliness.10 Green spaces may be particularly beneficial for older adults as they can provide safe opportunities to be active and interact with other people, while stimulating the mind and senses.11 Additionally, access to shared public spaces can reduce overall stress, improve coping abilities, encourage multigenerational interaction, reduce social isolation, enhance relationship building skills, and improve or maintain cognitive function.12 The demand for quality children and youth services compounded with the increasing need for creative older adult programs creates an environment ripe for innovative intergenerational spaces.

However, it’s important to note that while a space may be multigenerational, it may not be intergenerational. Multigenerational simply refers to a composition—people from different generations are present. Intergenerational refers to an active exchange or connection between and among the generations,13 and this is where there is a great opportunity to enrich both people and the environment, while promoting a wealth of positive benefits for all.

Loneliness is one of the most pressing current public health issues.14 Being socially connected is not only influential for psychological and emotional well-being, but it also has a significant and positive influence on physical well-being.15 A study published in 2018 found that socially isolated people may be more likely to have a heart attack or stroke, compared to people with strong social networks.16 Loneliness can occur at any age; in childhood it may be a feeling of being left out, as a young adult, it could be an exclusion from after work gatherings, or for a young stay at home mom, a feeling they have no connections outside their immediate family. As people age, there are a number of factors that elicit a feeling of loneliness, including the death of spouse or friends. Loneliness need not be age-related, it may be related to moving to a new community, the inability to connect easily with others, a limited scope of travel, or any number of other reasons.

A national survey17 conducted by AARP on adults age 45 and older found that 35% of adults in the target age group reported they are lonely. Of those individuals who are classified as lonely, 4 in 10 (41 percent) claim that feelings of loneliness and isolation have persisted for six years or more, nearly one-third (31 percent) indicate they have felt lonely for one to five years, and 26 percent report having these feelings for up to a year. Another report published by Cigna18 found that people aged 18-37 lay claim to being the loneliest, with those age 18-22 being significantly more likely than any other generation to say they experience the feelings associated with loneliness (e.g., feeling alone, isolated, left out, that there is no one they can talk to, etc.). In fact, more than half of those aged 18-22 identify with 10 of the 11 feelings associated with loneliness. Feeling like people around them are not really with them (69%), feeling shy (69%), and feeling like no one really knows them well (68%) are among the most common feelings experienced by those in this age group.

Intergenerational relationships can help combat loneliness by opening a wider circle of potential acquaintances, the opportunity to learn new skills, and other life lessons not as familiar to certain age groups, and in creating a sense of purpose.

Social capital can be greatly expanded by exposing more generations to each other and interconnecting networks to help communities function more effectively. The Communities For All Ages project (CFAA) is a place-based community building effort that helps organizations and individuals break away from age-specific silos, create shared visions, engage in collective action, and expand social capital.19 In their pilot project, in 23 sites across America, multiple generations who worked on and participated in CFAA’s work and activities in all sites report increased trust and interaction with others across traditional divides such as race, ethnicity, class, and age.

Through a variety of activities and programs, personal connections were formed between older and younger participants from multiple generations. Examples include community planning, where residents of multiple generations assumed leadership roles in the assessment and planning phase (decision making, facilitation of focus groups, mapping resources, reviewing data, building participation,) and participating in resident design teams that worked with architects and public officials to plan new intergenerational spaces. Many of the intergenerational teams were able to affect social capital in ways that hadn’t been achievable before their efforts, for example, using their advocacy skills to gain increased access to university and city resources for their health work, petitioning successfully that surplus weather radios be made available for low income older adults, and advocating for a recording studio to be used by all age groups. One community formed a cadre of intergenerational leaders who are charged with staying on top of the local budget and policies that affect their neighborhoods, and advocating for important changes in the city’s quality-of-life plan.

All of the sites share stories of the ways in which younger people and older people celebrate their joy, and help each other, building a sense of community that brings people of all backgrounds and socioeconomic groups together around collective resources. In sharing their wisdom, older adults seek to promote the positive functioning of society in the future. They prioritize helping others, especially guiding future generations, and are motivated by meaningful legacy.

In 1975, 13 percent of seniors were people of color, compared with 25 percent of youth under age 18, for a racial generation gap of 12 percentage points. Over the next four decades, all age groups became more diverse, but this shift occurred much more rapidly among the young. By 2015, 22.3 percent of seniors were people of color, compared with 48.7 percent of youth, for a gap of 26.4 percentage points.20

Research suggests that the racial generation gap can have serious consequences. Society relies on a kind of intergenerational compact, whereby seniors invest in younger generations because they share a stake in their success—both for their own security in old age and for the future of their community and country. But studies have shown that America’s seniors are less likely to support spending on youth when they are from different racial groups. This trend is particularly disconcerting given recent scholarship showing the positive impact that adequate school funding has on closing the educational achievement gap that persists for low-income students and students of color.21

Multigenerational communities and spaces can facilitate social interactions across age and race, potentially building greater social cohesion and intergenerational altruism that can align young people and seniors around common policy goals, including campaigns to increase awareness and build political support for investing in youth, strategies to specifically enhance senior support for school funding, efforts to increase voting among youth, and the development of approaches that link education spending to programs that benefit other community residents more directly, such as multigenerational facilities and communities.

Being socially connected is not only influential for psychological and emotional well-being, but it also has a significant and positive influence on physical well-being and longevity.22 Research has shown that social interaction even outweighs physical and mental health condition in affecting the successful aging of older people, and that using one’s wisdom and abilities in a meaningful way is critical to well-being in later life.23 More specifically, fulfilling the urge for intergenerational impact can mean the difference in overall well-being, as giving to others involves a sense of social belonging and value.

Although the mechanism for how social interaction affects successful aging is not clear, it is found that social interaction is associated with higher levels of quality of life,24 and lower levels of depression, anxiety disorder and hopelessness,25 neuroendocrine stress, and distress of social separation.26 However, research also suggested that the size of social networks decreases with advanced age.27

As with any generation, older people reap benefits from setting and achieving positive, meaningful goals.28 In using their wisdom and abilities to achieve those goals and to divert negative situations, they experience fewer mental health problems and improved wellbeing. Alternatively, well-being suffers when they face social isolation or other situations that impede the ability to achieve life goals. Finally, the almost universal preference of elders is to “age in place.”29 However, their increased risk of developing health issues as they age often challenges this preference. Open space and the positive influence that it can have on elders’ health may help elders continue to “age in place.” Moreover, neighborhood open spaces may also be considered “places of aging” or locations outside of the home that also influence the well-being and quality of life of elders.30

With the fast-changing technological advancement of our world there is a rich history waiting to be discovered by all generations through conversation. Consider the growth in popularity of history programs, online quizzes to identify objects not used in today’s culture, and other popular historically-focused activities. Imagine the rich stories waiting to be discovered simply by asking someone of another generation to share a favorite story, memory, or perception of a world event. While this rich library grows with age, there is knowledge to be shared by younger generations too as they relate stories of school, sports, etc. that have changed dramatically since older generations have participated. Sharing stories with interested people creates a sense of self-value and can be a catalyst for relationship building.

Intergenerational playgroups in aged care are an example of setting the stage for story sharing, but programs are limited and little is known about the perceptions of individuals who have participated in such programs. Most research is focused on intergenerational programs that involved two generations of people – young people and older people. However, in one study, a number of generations participated in the intergenerational playgroup intervention that included older people, caregivers who were parents, grandparents or nannies and children aged 0–4 years old. Each group was enriched by the experience, parents seeing their children interact in a whole new way and develop caring toward older people, and older generations feeling a sense of value, and renewed energy brought about by the younger people.31

One benchmark of successful intergenerational spaces is when people from different generations first realize that the other person, once a stranger, has value, deserves respect, and is now an important part of their life. As younger generations experience the usual benchmarks of maturation such as getting married, living independently, becoming parents, and developing a work pattern, it is meaningful to be able to confide in older generations that have been through these life phases and can help navigate the changes associated with major life events. Older generations, therefore, can have a greater role and build selfesteem by knowing they are viewed as a knowledgeable resource. The challenges and joys of marriage, independent residence, employment and adulthood encourage younger generations to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of older generations and, as a result, many younger family members develop a respect for their parents and grandparents. This building of respect is an important aspect of building intergenerational relationships, as the relationships themselves will not self-sustain unless responding elders perceived respect from younger generations, and vice-versa.32

Culture is a strong part of people's lives. It influences their views, their values, their humor, their hopes, their loyalties, and their worries and fears. Therefore, when you are working with people and building relationships with them, it helps to have some perspective and understanding of their cultures.33 Working from the premise that all residents deserve similar access to good parks, not just as a matter of right, but for the collective benefits that parks have on health, environment and other outcomes, it is important to bridge equity gaps in parks and create safe, well-maintained spaces for communities to gather and interact.

Recreation promotes positive contact between different ethnic groups and provides a means for open dialogue in a nonthreatening atmosphere. Recreation opportunities offer an open stage for social interaction that can help to break down the barriers of unfamiliarity, fear, and isolation. Community strength is increased through recreation activities that allow people to share their cultural and ethnic differences. When parks make intentional efforts to collaborate on design and programming with the cultural communities living within walking distance of a park they may be able to foster social cohesion and a collective sense of ownership of a public space, which can contribute to vibrant intergenerational activity.

As you think about diversity and setting goals related to building relationships between cultures, resolving differences, or building a diverse coalition, it helps to have a vision of the kind of cultural community you hope for.

• In order to build communities that are successful at improving conditions and resolving problems, we need to understand and appreciate many cultures, establish relationships with people from cultures other than our own, build strong alliances with different cultural groups, and bring nonmainstream groups into the center of civic activity.

• Each cultural group has unique strengths and perspectives that the larger community can benefit from.

• Understanding cultures will help us overcome and prevent racial and ethnic divisions.

• People from different cultures have to be included in decision-making processes in order for programs or policies to be effective.

• An appreciation of cultural diversity goes hand-inhand with a just and equitable society.

• If we do not learn about the influences that cultural groups have had on our mainstream history and culture, we are all missing out on an accurate view of our society and our communities.

©Community Toolbox, (1994) Center for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas

Intergenerational environments build strong social networks that foster connections across age, race, socio-economic class, and other divides. Utilizing skills and resources that may be unique to generations can help expand services and create richer environments for all. Some examples may be establishing policies that make it easier for people of all ages to find housing appropriate to their needs by considering housing that is built with multigenerational needs in mind, or programs that allow youth to prove services that can help older generations to stay in their homes. The latter has proved successful in the Age-in Place program of Seabury Resources for the Aging in Washington, DC, where youth volunteer to provide basic home maintenance services such as cleaning and yardwork to older adults who may be physically unable to, so they may stay in their home.

Utilizing available transportation is another potential program where youth can assist in expanding public services. As an example, the Council on Aging in St Augustine, FL, created a program where teens help seniors in the community understand how to read schedules for the public bus system, helped them learn how to transfer among routes, and generally gave the older residents confidence to overcome their fear of public transportation, thereby opening their circle of travel and independence dramatically, providing access to parks and open spaces, and other services, that may not have been accessible without transportation assistance. It also created a bond between the two age groups as they broke down barriers and embraced a greater understanding of each other.

Skills and knowledge are acquired through experience, and the experiences we have at different life stages can be passed on to others. Additionally, when knowledge and skills are marketable and economically useful, there is a benefit to sharing them beyond generational boundaries. Most commonly, these skills are shared within educational or employment settings as students and employees learn new skills from their teachers/supervisors. In particular, the workplace is a crucial site of intergenerational relations and exchange of human capital that may be vital to company survival and continued competitiveness.34 The continual sharing of this human capital between generations is clearly vital for economic growth, and in fact, the functioning of society. But there are limits to these processes in education and the workplace. Companies may be limited in what can be invested in the training of staff, and individuals may not have the funds, or be too risk-averse, to invest in further education. This means that every other site and mechanism available for the transmission of human capital between generations is vitally important, whether through community activities, social networks, mentoring opportunities, or other meaningful ways.

Interestingly, as individuals experience longer careers, they often undertake re-training and re-skilling at several points from younger peers. As a result, the transmission of human capital

also occurs upwards between the generations, and not just downward. It’s also important to note that educational opportunities between generations are not just limited to marketable skills. Adults can help young people develop their talents and knowledge, while advising on work relationships, finding meaning in life and work, and managing daily life conflicts.35 Reaching mature adulthood offers an ability to communicate and model non-cognitive skills and to help young people develop these key traits. The perspective that comes with age helps older adults to nurture development of social skills and a sense of purpose among the young people with whom they form meaningful relationships. The linkage between aging and wisdom is a logical one. Accumulation of life experiences creates a knowledge bank as aging people encounter complex problems and develop strategies to solve them. Aging also involves the ability to maximize success, leading older people to be more strategic in their interactions with others. In short, as we age we develop more ability to control our environment and navigate our lives within it.36

Conversely, there are experiences gained by younger generations that older ones may not have exposure to, utilizing emerging technology for example. People tend to master technologies available at their peak ability. However, past this ‘peak’ many individuals struggle to adapt to emerging technologies that are quickly adopted by younger cohorts. The implications of this can have a lasting effect; being unable to use a computer, cell phone, or new system can promote exclusion from conversations, social media, learning, and interaction. It is therefore no surprise that examples of the transmission of computer skills from young to old can be found in many families and communities. Research shows that pairing young and older people has positive consequences for each. In promoting the well-being of the next generation, older adults experience fulfillment and purpose in their own lives.37 For example, one study38 showed how children in Big Brother/ Sisters programs were less likely to begin using drugs or alcohol, less likely to skip school, and less likely to get in fights after only 18 months in the program. The study also found that the children were more confident in their schoolwork and got along better with their families due to the intergenerational relationships formed.

• At age 2, Bonnie Blair began skating, going on to win five Olympic Gold speed skating Medals.

• At age 3, Wolfgang Mozart taught himself to play the harpsichord.

• At 8, three-time gold medalist Wilma Rudolph took her first step after having polio.

• At age 11, pilot Victoria Van Meter piloted a plane across the US.

• At 19, Abner Doubleday devised the rules for baseball.

• At 20, Charles Lindbergh learned to fly.

• At 29, Alexander Graham Bell transmitted the first complete sentence by phone.

• At 32, Alexander the Great had conquered a large portion of the world.

• At 40, Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run.

• At 49, Julia Child published her book “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

• At 57 Frank Dobesh competed in his first 100 mile bike ride, exactly 10 years after being diagnosed with an inoperable brain cancer.

• At 62, J.R.R. Tolkein published “Lord of the Rings.”

• At 71, Michelangelo received the greatest and final commission of his life-chief architect of the sprawling St. Peter’s Basilica.

• At 82, William Baldwin crossed the South Boulder Canyon, CO, on a tightrope.

• At 95 Nola Ochs became the oldest person to receive a college diploma.

• At 99, Teiichi Igarashi climbed Mt. Fuji.

People, no matter their age, have many things in common. However, when primary contact in day to day life are with those in similar age groups, inaccurate stereotypes can form and be shared among the group. However, research has found reduced stereotyping of older people, and in fact a sharing of similarities in cases of intergenerational groups with regular contact.39 This demonstrates the importance of positive contact in tackling the psychological processes that underlie age discrimination. While this is most common in the workplace, where generations are brought together by a shared goal and a structured workweek, examples are less common in the non-work environment.

Studies in psychology have explored ways that contact with younger generations in positive and negative contexts affects the cognitive performance of older people in tests40, showing how positive contact with younger people can reduce feelings of intimidation. Other research has found that positive intergenerational settings were associated with more social behavior in adults, and higher cognitive performance in older adults.41

These outcomes highlight the role of positive intergenerational relations in preventing age-based prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping. Reducing such discrimination is an important ongoing sphere of policy development, and the potential of intergenerational contact and interaction to advancing such objectives underlines the importance of intergenerational relations for public policy.

People of all ages like to feel useful, valued, and accomplished, but as people age, especially into retirement years, that feeling can be diminished as they often play a lower-key role. However, older people’s qualities, and their affinity for purpose and engagement, position them to make meaningful contributions to the lives of youth, helping fulfill their desire for a sense of meaning and purpose, and promote social/emotional well-being.

Youth need non-cognitive emotional skills-the crucial attitudes, behaviors and strategies required to maneuver in a complex and technical world. These skills include critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, confidence, social interaction, influencing social connections, and sense of purpose, all of which are important for success in school and work, as well as contributing meaningfully to society. Emphasizing non-cognitive development has been shown to improve concrete performance in reading, writing, and mathematics. Unfortunately, the deficit in noncognitive skills is most acute among socioeconomically disadvantaged youth.42

Older people are well positioned to step into this mentoring role as they can possess emotional stability that improves with age, and the wisdom that grows as experience deepens. Emotional stability and willingness to forgive make older adults especially well-suited to mentor younger counterparts on complex interpersonal problems. They have strategic communication skills and are motivated to contribute to the lives of future generations, thereby building emotional wellness and a sense of good in both older and younger generations.

Older people’s qualities, and their affinity for purpose and engagement, position them to make meaningful contributions to the lives of youth, helping fulfill their desire for a sense of meaning and purpose, and promote social/emotional well-being.

While a great deal of history is written and published, the types of learning that can occur from hearing stories, verbalized by those who have played a role in the story, should not be overlooked as a valuable medium for sharing culture and increasing equity through education. Most families can share at least one historic tale involving an ancestor that has been passed down through generations. The creation and transmission of ‘collective memory’ occurs through intergenerational dialogue at a family level,43 and by extension, can also occur at the community and societal level. Such historical memories are crucial to the formation of communities, as well as the personal identity and community attachment of individuals. Cultural art, music, dance, etc. are often passed down through the social interaction of different generations, and can be shared across cultures and generations through active behavior, storytelling, and gathering. Settings that encourage dialogue increase the opportunity for rich social history to be shared, and therefore not lost.

There is much to be shared and gained when multiple generations recreate, collaborate, and learn from each other. Local parks and open spaces offer the perfect opportunity to introduce these generations and give them a safe space to enjoy impactful dialogue and activities with each other.

Communities are made up of people of all ages. However, a study conducted by the RAND Corporation44 found that parks are increasingly geared toward the young. The study focused on cities with a population of more than 100,000; data collectors were sent into 174 parks in 25 major cities, asking them to describe the facilities and conditions, and the demographics of users during a typical week during the spring or summer of 2014.

Parks, of course, varied from neighborhood to neighborhood. But looking across the entire survey sample, almost all had lawns and play areas. About half had outdoor basketball courts and baseball fields. But just 29 percent had a walking loop, and the percentage of parks with a dedicated exercise area or fitness space was in the single digits. Adults ages 60 and up made up only 4 percent of park-goers, even though they're 20 percent of the population. Thirty-eight percent of park users were children and 13 percent teens, though those demographic groups represent 20 percent and 7 percent of the U.S. population, respectively.

Parks and open space are meant to be used by all people, regardless of age or other demographics. A well-designed environment provides a wealth of benefits for all generations. However, as suggested by the aforementioned RAND study, many parks and public spaces may not be set up for maximum enjoyment by all generations. One of the most important aspects in creating intergenerational relationships is paying attention to how the physical environment plays a role in promoting, or inhibiting, intergenerational engagement. While most will recognize the importance of multigenerational settings, where the physical environment is designed to

accommodate the physical and psychological needs of people across the age and ability spectrum, there needs to be an equal consideration to the ways these environments afford opportunities for meaningful engagement between members of different generations.

Understanding the unique balance (and ongoing change) of a community’s residents, maintaining the right balance of infrastructure, programming, and amenities, and obtaining meaningful feedback to react to perceptions and need, all while balancing budgets and competing priorities can be challenging. However, studies have documented the connections between nature experiences and human health and wellness, and evidence confirms that natural environments can aid with attention restoration and stress reduction, contribute to positive emotions, and can promote social engagement and support45 across generations in a variety of ways.

While the use of outdoor space to create settings that encourage the benefits of intergenerational relationships just makes sense for all the reasons discussed in the previous chapter, and more.

Recent years have seen a resurgence in the protection of the natural environment, from people moving to urban areas away from nature, to schools looking to “green” their schoolyards, to the growth of organizations intent on preserving green space for the future. However, research shows the barriers that disconnect people from nature are significant and society-wide, but despite this challenge there is opportunity. People of all ages and backgrounds recognize that nature helps them grow healthy, be happy, and enjoy family and friends. Restoring relationships with nature requires collaboration not only within the nature conservation community, but across broad sectors of society such as education, urban planning, policy making, and community development.46 Adults who are concerned about the world they leave behind are tasked with ensuring this love, appreciation, and concern about the state of the world is curated among the young who will inherit it, and intergenerational opportunities in nature is a valid catalyst for making this happen.

Parks and open space are meant to be used by all people, regardless of age or other demographics. A well-designed environment provides a wealth of benefits for all generations.

Our parks and public spaces have great potential to change our communities for the better. By bringing together people from all backgrounds and ages, the public places we all share can combat generational silos, segregation and other age-related issues we are facing as a nation, while helping to ensure equitable access for all. Intergenerational design aims to bring people together through purposeful, mutually beneficial activities that promote greater understanding and respect between generations. Additionally, investing in these spaces fosters value creation by building cohesive communities, encouraging additional investments in neighborhoods and local businesses, and changing the perception of safety.

Percentage male person-hours in parks

Total = 867 (SE=153)

Percentage males by age group in US population (2010)

Percentage female person-hours in parks

Total = 664 (SE=135)

Percentage females by age group in US population (2010)

As demonstrated in the previous chapter, a RAND study of 174 parks in 25 major cities with population over 100,000 demonstrated the generational disparities found in the subject parks. Neighborhood parks and programmed activities tend to be geared toward youths more than adults. Disparities in park use include low use by adults, seniors, women, and girls, and lower use in high-poverty areas. Designing public spaces to attract and hold the attention of multiple generations is an important strategy for encouraging intergenerational play and recreation, and can be achieved with a meaningful design plan that considers the many ways people can gather and participate across intergenerational groups. Think first about the types of intergenerational behaviors, like walking, reflecting, exercising, and playing, then give consideration to the amenities that can be added to each behavior zone to encourage participation. It is not enough to simply add amenities that are exclusive to a single age group, but rather we must understand the behaviors and activities that people of all ages may be interested in, and how the environments we create foster a feeling of inclusion, not exclusion, across the age spectrum.

Additionally, even within multigenerational spaces there may be some highly active areas where observation rather than the event itself is the more enjoyable pursuit. As an example, seating/bleachers around sport courts, skateboard areas, and similar “high energy” active spaces provide ways to passively enjoy the activity, with the addition of clearly marked routes to and from the seating areas to avoid conflict with more dynamic participants. However, there may be times when people would prefer solitude or gathering with their own generation, so providing choice and flexibility in how to engage is key, and organizing park spaces to facilitate interaction while considering people’s need for privacy is important so that interaction isn’t forced and the park is meaningful in terms of how much or how little one chooses to interact.

Walking Paths

Gathering Hubs

Gardening Spaces

Quiet Spaces

Playgrounds

Fitness Areas

Cycling Support

Game Play

Dog Parks

Swimming Pools

Splash Pads

Outdoor Music Areas

Camping Spots

Climbing Centers

Sports and Open Fields

Parklets

Additional Considerations

To help encourage intergenerational recreation opportunities, we first need to understand the physical environment and how it influences social behavior. Great intergenerational spaces must go beyond “activities and programs” and align the physical environment with the infrastructure needed to open dialogues and encourage gathering in intergenerational settings. Well-planned outdoor environments that remove barriers to participation and give consideration to the preferences, habits, and comfort of a broad collective across the age spectrum can set the stage for meaningful interface between all people. Layering activity options to broaden intergenerational experiences is important. Lessons can be learned from the publication, Why People Love Where They Live and Why it Matters,47 and the same factors identified in why people of all ages are attracted to a community can certainly be applied to parks:

AESTHETICS - The physical beauty of the community including the availability of parks and green spaces.

SOCIAL OFFERINGS - Places for people to meet each other and the feeling that people in the community care about each other.

OPENNESS - How welcoming the community is to different types of people, including families with young children, minorities, and people of varying ages and interests.

By promoting these attributes through thoughtful design, communities can build social and emotional capacity, as well as overall community capital. There are a variety of activities and infrastructure that can help increase this appeal.

Walking is a popular activity for older generations, it promotes mobility, cardiovascular health, reduces risk of hypertension, certain cancers, osteoporosis, and more. It also promotes balance, strength and flexibility.48 However, walking is increasingly popular with younger generations as it is an easy form of exercise, it’s safe, easy to stick with, and low- or no-cost. It doesn’t require any special skills or equipment, and for such a simple activity, it has so many benefits.49

Enhancements such as walking loops and programmed activities could help boost intergenerational park use, which may be enhanced further by adding walking trails around playgrounds and ball fields, so parents can keep an eye on their kids while getting some exercise for themselves, and older adults can delight in the sound of children at play. Walking may also serve as a catalyst for intergenerational conversations and spontaneity.50 Beautiful walkways, parks, and gardens51 provide people with a focal point or means to follow their own interests. Not only can they walk, bike or run, they can, for example, bird watch or enjoy ornamental gardens. Pathways can also be augmented with planting pockets that feature natural or manmade shade and benches for reflecting. To promote a sense of calm, angle this type of seating away from the path, and use plants as a screening buffer to reduce noise from the path.

Paths can also benefit from a variety of amenities designed to draw people along the walking route, engage them in activity, and provide appropriate destination points for those who need to take short sitting breaks. Play pockets, fitness equipment, musical instruments and spaces to sit and reflect are important attributes for intergenerational paths. Spaces should also provide shelter and shade to offer comfort options in all types of weather.

Additionally, paths should be created with access in mind, paths or trails for pedestrian use must have a firm and stable tread and be at least 36” wide, excepting places where natural plantings may narrow the trail to 32” wide. The Access Board provides ADA Accessibility Guidelines to assist, see Resources section for more information. Additionally, paths should connect to parking, restroom facilities, water fountains and other amenities throughout the space.

Finally, consider the overall design of the pathway network as an important attribute for its usage. If the option is available, designing short, subsidiary loops in the path provides choice of path length and potential for repeat visits as these loops provide a variety of ways

to experience the overall path.52 Curving forms make the pathway experience inherently more exploratory and stimulating because of the anticipatory excitement. Looping forms add further interest by ensuring that users do not need to turn around and return by the same way they came. Also keep in mind the importance of slope, surface and width, and how they will affect level of use, type of use, user group, and extent to which various design criteria may be met. For example, a narrow tread could limit three individuals from being able to walk abreast and converse, or prevent groups of children being able to play together. A rough uneven surface may limit use by older adults using mobility devices. A steep grade would limit use by people who use wheelchairs.

In a study of racially diverse seniors, gardening was identified as important because it connected them to their past and future generations, was a source of memories and social events, and brought opportunities for spiritual healing and therapy. 53 Gardening in community or institutional settings also improves quality of life, fitness, cognitive abilities and socialization, and may reduce the risks of dementia54 and improve mobility and dexterity. 55 Gardens can create multigenerational connections and strengthen relationships as older, experienced gardeners share their knowledge with young adults who may be looking to garden at their first home. Youth also can benefit from gardens as they learn where human sources of food originate, the many ways plants provide food for wildlife, and the natural beauty and function that nature can provide. This shared knowledge of the natural environment can help encourage appreciation for nature in younger generations and create future stewards of nature and natural settings.

In a joint publication between Generations United and the Penn State Cooperative Extension, a variety of overlapping benefits between environmental education and intergenerational programming were identified,56 including the empowerment of coming together with others to amplify the ability to affect and improve the environment, creating an intergenerational framework of pedagogy, utilizing multiple disciplines and settings to create learning

opportunities for various age and ability levels, examining the effect of nature on different stages in the lifespan, emphasizing sustainability across generations, and creating learning opportunities through social interactions. Environmental education, shared through the multidisciplinary benefits of gardening, simply creates a variety of opportunities to bring youth and adults together. Gardens can also help address food insecurity in underserved communities, providing valuable whole food resources while teaching younger generations the importance of giving and sharing to promote community equity.

Plants can also provide play value for younger generations, they can be selected for specific play value attributes, like those that promote sensory stimulation, attract butterflies or birds, provide "loose parts" for play, or a host of other playful traits. Specific databases are available to sort and select zone-appropriate plants for their play value, see Resources section in the back of book. Plant databases can also provide opportunities for intergenerational learning as facts about plants are shared.

Additionally, when designing garden spaces, consider multiple levels of view, from children to adults to those who may be using mobility devices. Creating multilevel spaces also provides opportunities for people of all ages and abilities to share regarding their view and perspective of the plantings. If you create community participatory gardens, consider raised gardens to allow adaptive use for those who may be unable to or uncomfortable accessing ground-level gardening.

Environmental Education

Empowerment

Interactive pedagogy

Multiple disciplines and multiple settings

Lifespan perspective

A garden doesn’t need to be participatory to be effective, passive enjoyment is also beneficial. The Portland Memory Garden in Portland, OR, created in 2002, serves the needs of those with memory disorders and their caregivers, but is open to all users. The park offers places to simply sit and enjoy as well as a smooth, walking pathway that has landmarks to assist with way-finding. The plants in the garden were uniquely chosen to provide sensory stimulation through seeing, smelling, feeling, tasting and hearing. Located in the southeast corner of Ed Benedict Park, this garden is especially designed for people with Alzheimer's disease and other memory problems: the site is relatively flat and is away from other park activity and significant traffic noise. Spaces for active recreation include sports fields, playgrounds, and a skate park, which are separate from passive observation spaces, the gardens, and accessible picnic areas and restrooms to facilitate multigenerational engagement.

Sustainability

Create learning communities

Intergenerational Programming

Green spaces, such as community gardens or even the shade of a large tree, encourage social contact by serving as informal meeting places and sites for group and shared activities. They can provide quiet, secluded areas specifically designed for storytelling, reading, telling jokes, fun discussions, and observation.

Structured areas can be created to encourage family gathering, and increase comfort for older generations. Combining a picnic shelter with seating, trash receptacles, grills, and play/game options creates an environment that encourages gatherings around like interests, such as games, farmers markets, car shows, group meetings, or other events where intergenerational sharing can take place. In these instances, shelters can be grouped together to create an easily identifiable hub for event attendees. Infrastructure is key and providing picnic shelters with tables is one way to create a “marketplace” or you can partner with a local agency to provide rented tables to interested participants. A series of shelters placed in a row can add comfort for vendors at these events, and make your venue the popular choice. Revenues from site and table rentals can help augment maintenance and increase the budget for new amenities. Shelters could be installed in different areas throughout a public space, using color as a wayfinding opportunity to direct people to their specific functions. (ie. Green shelters are for picnics, Black shelters indicate the farmers’ market, etc.)

Creating storytelling hubs in a public space is another strategy to encourage intergenerational sharing of information. As an example, a path could lead to a “cul-de-sac” of benches, positioned around a central fire pit, or other focal point low enough to permit eye contact around the circle. Such areas are a perfect visual cue to invite talk and meaningful discussion between generations.

Provide plenty of choice in places meant for reflection and restoration. As people of all ages can benefit from quiet time, a restorative space should make one feel “at home” and comfortable. Most importantly, consider the culture and attitude of the users. For older adults whose youth was spent in other cultures, nearby nature should be culturally meaningful to provide the most benefit. If a place feels familiar and has features that connect to one’s cultural roots, people may be more likely to walk to the area, maintain interest and engagement, and derive meaning and satisfaction from their time spent in the space.57

Adding water features to a reflection area can help mitigate sound from surrounding areas, especially in smaller parks, to encourage peacefulness. Similarly, dense shrubs and plants can help to mitigate sound and create the feeling of a quiet oasis. Some quiet spaces also add a single outdoor instrument with deep low tones, to provide gentle relaxing sounds similar to a wind chime, or a labyrinth wrought in a colorful rubber surfacing material, which can promote fun for younger generations and safety for older participants.

While these spaces are intended for quiet reflection, they are another meaningful way for people of all ages to recognize a shared need for introspective concentration.

While these spaces are intended for quiet reflection, they are another meaningful way for people of all ages to recognize a shared need for introspective concentration.

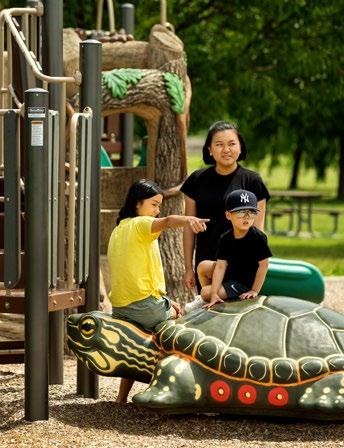

Play is a common activity between generations. It can involve a variety of motivating activities associated with fun and enjoyment. Play acts as a connecting force between age groups, providing them opportunities to build relationships and enjoy each other’s company. A great example of the positive attribute of multigenerational play can be found at Glenrose Hospital, in Alberta, Canada, where family-centered care is their primary focus. Their outdoor enclosed courtyards feature inclusive experiences for children and adults of all ages and abilities, including activities that encourage imagination, discovery, creativity, and physical development as they explore play areas, basketball hoops, benches and picnic areas, and movement activities designed to stimulate the vestibular and proprioceptive senses. Physical and gross motor rehabilitation opportunities for adults and seniors include fitness equipment that promotes strengthening activities, and others designed to improve balance, coordination, and motor planning. Patients can also adapt play skills they gain as they integrate back into community settings. Users include individuals and families accessing both the pediatric and adult services at the hospital, and children attending school through the School Rehabilitation Service.

Creating accessible playgrounds is critical, not just for children with disabilities, but for parents and grandparents as well, as it contributes to providing play opportunities that are “age neutral.”

Creating accessible playgrounds is critical, not just for children with disabilities, but for parents and grandparents as well, as it contributes to providing play opportunities that are “age neutral.” Ramped structures ensure the greatest access by the greatest number of people to the greatest extent.58 While ramped play structures are most commonly built to allow children with disabilities their right to experience equitable play, the considerations created in these environments are equally critical for parents with disabilities who may wish to play alongside their children or be afforded an opportunity to retrieve an unhappy or disobedient child from the elevated structure. Similarly, grandparents or older family members who may wish to play alongside younger family members may not be comfortable ascending a ladder or climber, but would be perfectly happy to reach the highest areas of a play structure if an accessible path was afforded to them.

Locating play areas near adult fitness spaces, picnic areas, trash receptacles, seating, and shade helps to ensure people are comfortable, have options for use and rest, and may encourage them to stay longer.

Fitness is important at any age, and fitness habits established young may be an important instrument to optimize educational achievements, cognitive performance, as well as disease prevention at the societal level later in life.59 While children often reap the benefits of physical activity while at play, adults may prefer more “fitnessbased” exercise to promote overall development and preservation of health and wellness attributes. Finding ways to incorporate all generations within a fitness setting that is comfortable for everyone is an important strategy to promote intergenerational fitness.

Some parks are intentionally creating trails where both adult fitness and youth play opportunities are positioned along the trail so family members can choose ageappropriate activities within sight of each other. Others are placing adult fitness areas within sight of playgrounds so parents can exercise while supervising their children. Still other opportunities involve intergenerational activities, like challenge and race courses, where the activities are age-appropriate for most family members to encourage playful competition in an intergenerational setting. For pathways, adding distance markers (for example every quarter mile) throughout the space is also a good way to encourage people to walk or run, note the distance they have traveled, and focus on increasing walking distance in subsequent visits.

People of all ages love to ride bikes in nice weather, and while some riders are interested in cycling as a leisure activity, others use bikes as a preferred mode of transportation. According to a 2015 survey conducted by People for Bikes,60 bicyclists age 55-plus hit the road and trails more often than any other adult group with 42 percent riding more than 25 days a year. At the time of this writing, People for Bikes also states that the year 2020 will likely stand as the biggest year for U.S. bicycling since 1973. Sales — particularly of low-cost bikes, e-bikes and kids models – should approach all-time annual highs. Riding participation is breaking all records, increasing by 20 percent or more in just about every category, on pavement, on dirt, at parks and hopefully soon to work and school. Given that Americans traditionally take nearly five billion bike trips a year, this rise is significant. Lifestyle changes imposed by COVID-19

have been a huge factor in this growth. The pandemic inspired millions of Americans to reassess what’s important and ask themselves how they want to live, and a new concept of modern living is taking shape. It’s slower paced, more focused on people and simple pleasures, and better for the planet. Bike riding is a growing part of it, as is the importance of parks and spending time together as a family.

Ensure cyclists are able to enjoy intergenerational parks by providing ample bike parking. There are bike racks that can be easily added to primary gathering areas, trailheads, picnic areas, etc. Consider bike shelters for optimal protection in areas with a greater occurrence of inclement weather. Be sure to observe and plan for bicycle traffic throughout the entire environment, if riders don’t feel safe at your venue, they may not come, especially if riders in the group include children. If you have paved trails, be sure to post rules for people using multiple modes of transportation, from pedestrians to walkers, runners, skaters, and cyclists.

Including ways to play games is another strategy to encourage intergenerational activities. Surfacing options offer a vast array of opportunities to infuse active fun and games into the overall design of the environment, promote meaningful experiences, provide multisensory features, and encourage creativity, imagination, and learning.

Many color options exist when considering poured-in-place (PIP), tile, or other surfacing material. Using various colors can help visually organize play and recreation environments so that they make sense to the user. Colors can provide visual cues and contrast to remind users that this is an active area and to proceed with caution, to create visual pathways throughout the environment, or to help with wayfinding assistance.61

Using designs or shapes in various colors can provide ground level ways to promote fitness without trip hazards, like with embedded agility ladders, or to encourage multigenerational learning opportunities, as with maps, or designs that promote cultural/ community history. Game tables for chess and checkers can be easily create with alternate colors of tile, or poured in place rubber.

Dog owners and advocates come in all ages. From our first puppy as a child to our faithful companions that keep us company or act as a service partner in our later years, the power of a dog’s love cannot be denied. Dogs add love and companionship to their households and families, which can help to reduce stress. Additionally, owning a dog may keep people in better physical shape simply by the act of walking the dog every day.62

Dog parks are gathering places for pet parents of all ages. People bring their pets to the park to get exercise and socialize with other pets, and dog owners do the same thing. While the dogs are playing, community members can form relationships, participate in conversation and exchange helpful information around upcoming dog events, veterinarians, and breed related questions. The common bond of pet ownerships transcends age barriers and provides opportunities to connect. Children may be more comfortable asking questions of other dog owners when the pet acts as an adorable ice breaker. Adults can share knowledge and training tips with all generations. Everyone can revel in the fun antics of the dogs as they play. Connections among dog park visitors help to bring neighbors together and build stronger communities in a manner similar to neighborhood watch programs.63

It’s no surprise that dog parks are one of the fastest growing amenities in public parks today. Adding trash disposal, leash posts, benches, shade, watering stations and waste bags help to make the dog park more comfortable and user friendly.

Swimming is an activity that can be enjoyed by people of all ages and abilities.64

Swimming provides a unique activity for people who have been inactive, as well as for older people with reduced mobility to be active and improve health. It can strengthen muscles, promote balance and fall prevention, and help to prevent high blood pressure. It burns calories and improves cardiovascular health. It can increase energy expenditure and lower all-cause mortality risk, while enhancing brain blood flow and arterial health, all of which are valid and critical health markers in older adults.64 Swimming is an enjoyable activity for youth and teens, and pools are great meet up places for them to be together and enjoy friendship in and around the pools.

For the younger generations, ensuring the ability to swim can save lives and build confidence, and as older people have the knowledge to do so, it provides intergenerational teaching and learning opportunities.

For the younger generations, ensuring the ability to swim can save lives and build confidence, and as older people have the knowledge to do so, it provides intergenerational teaching and learning opportunities.

Splash pads are a fun intergenerational amenity where parents and grandparents can bring kids. The kids can play, and the adults can choose to play as well, or simply socialize. While the visiting experience may be multigenerational, splash pads will need to offer a variety of experiences to ensure comfort for all. A stable non-slip surface is an important consideration, as is a variety of water experiences, including gentle, non-intimidating sprays or mists for the youngest and oldest users, and higher-volume sprays and dumping elements for tweens, teens, and young adults.

Splash pads are a great way for people to cool off in warm weather and prevent overheating, but that same cool feel can reduce the awareness of sunburn so it’s a good idea to have shady areas and/or shelters with ample seating and picnic tables for when it’s time to take a break from the water.

Musical experiences add to people’s lives at any age. From lullabies we hear as babies to our favorite artists over our lifespans to the memories that certain songs recall as we age, music is a powerful force. Students who take music lessons can improve confidence and academic achievement, and choir singing has been proven to positively impact the physical and emotional well-being of older adults. 65 Music is a universal language. You can sing to it, dance to it, teach lyrics or dance steps, or simply relax and listen, whether alone or in a group. All of these musical activities are catalysts to establishing connections, relationships, and friendships. Multigenerational users can collaborate in these musical spaces in interesting and creative ways. A well-designed outdoor music environment promotes engagement among diverse users, accentuates natural attributes of the outdoor setting, and provides intentionally harmonizing musical elements that facilitate discovery and bring joy to every experience.42

Including seating, shade, open areas, and even embedding dance steps into the surfacing around the instruments can help facilitate all of the aforementioned ways to engage.

The positive experiences that are generated by intergenerational camping are many. Adults have the opportunity to teach valuable skills to younger generations, and help ensure the love of camping, and the outdoor environment itself, endures into future generations. Because camping takes people away from their normal surroundings and creature comforts, the experience of camping creates new situations where different roles emerge, “normal” life is suspended, and people must work together to create a workable and enjoyable experience. Food preparation is no longer a matter of heating something in the microwave, as cooperative behavior, through assigned chores, is required for wood gathering, fire building and tending, food preparation, cooking, serving and clean up with more primitive means that is customary. Besides strengthening family units, camping promotes skills like perseverance, physical endurance, teamwork, and cooperation among generations. Camping has recently seen a huge upswing in popularity, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with half a million new campers in 2016.66 As of 2020, 43% of leisure travelers say that spending time outdoors is more important than ever and 60% saying it’s more important for children and families.67

To help ensure camper comfort, consider seating, shade, shelters, raised grills for cooking, trash and recycling receptacles, as well as bike parking.

For all the reasons children enjoy climbing — fun, challenge, development of manual dexterity, grip strength, coordination, and balance, adults can benefit as well. Climbing walls need not be super high for these benefits to be achieved. Traversing, or climbing side to side is a great way to promote the benefits of climbing, and when combined with required safety surfacing, offers even younger or older climbers the opportunity to develop skills in a compliant, non-intimidating way. It makes a great intergenerational, confidence building activity.

Sports fields represent a context where many intergenerational activities can take place. Organized sports is the obvious one, and while age and ability differences between generations may preclude a hearty competitive game of football, roles can be assigned to non-players to ensure the activity is enjoyable and communal. For example, local amateur football clubs could target older members who may not actually continue to play competitive football, but can nevertheless contribute to the functioning and community of a club through promotion, coaching, and encouraging behavior for example. Providing shaded bleachers can help encourage parents, caregivers, and grandparents who aren’t on the field to participate as cheerleaders and lend support.

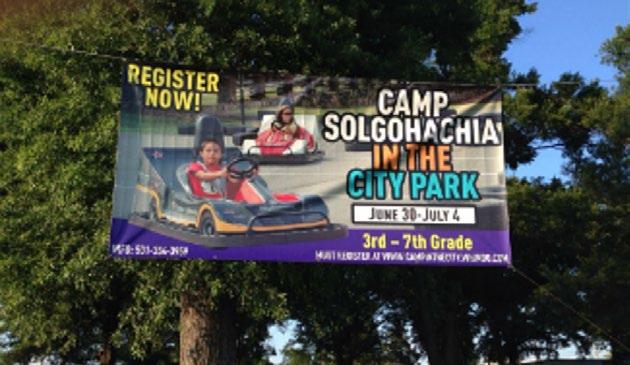

Large open spaces can also provide sites for concerts, scavenger hunts, geocaching, “learn to play” sport camps, family competitions and gatherings, picnicking, conversations and storytelling, and walking. When complemented with simple comfort amenities like seating, shade, trash receptacles, etc, the space becomes an open canvas for families and multiple generations to use their imagination and create opportunities for engagement.

While parklets are generally thought of as raised platforms set into urban parking spaces to create park-like areas, the raised platforms used in parklets can also create ideal mini gathering spaces within more traditional park settings. In communities that may have more asphalt than green space, parklets can help bring recreation spaces to neighborhoods that may not have a traditional park. Set them off high speed bike/running trails to create safer gathering areas for children and families, use them in wooded areas to create stages or bandstands for performance, or create VIP seating areas close to the action in concert or sport settings.

No matter what the overall activities, it’s important to think of design considerations that transcend specific pursuits and are applicable to all settings.

It’s critical to think about the abilities of people across a diverse generational span, as people of different ages vary in their physical functioning. Using best practices for inclusive design is a good way to ensure active independence across generations and to ensure physical and social opportunities for all, including those with and without disabilities. Now, more than ever, communities are seeking innovative ways to unite children, families, and communities through the power of play and recreation.32 Using these inclusive design principles will help to facilitate intergenerational integration in the activities that occur in play and recreation spaces, and help to provide spaces that all can enjoy.

While specific amenities within a space can be designed to be inclusive (i.e. playgrounds, picnic tables), it’s important to think of the overall space design. The US Access Board provides great information (see Resources) but also consider comfort and wayfinding, especially for our oldest generations and the normal biological changes that come with increasing age: reduction in muscle strength; higher levels of fatigue; reductions in agility, coordination, equilibrium, flexibility, joint mobility and increased rigidity in the tendons, and reductions in sensory capacities (hearing and vision.) It’s important to give consideration to well-placed handrails, contrasting color on steps, fall attenuating surfaces, adequate lighting, park maps, route markers, shade, etc. to enable people of all ages and abilities to navigate the overall space comfortably and confidently. Be sure sidewalks are free of wide cracks, holes and trip hazards and that vegetation is not allowed to encroach on walkways. Where possible, consider fall attenuating poured rubber surfaces for primary paths. Provide ample trash receptacles, as carelessly discarded trash can also present trip hazards.

Now, more than ever, communities are seeking innovative ways to unite children, families, and communities through the power of play and recreation.

In addition to benches being added throughout active and passive environments, it’s important to consider benches “along the way,” for those who may need to rest as they walk through the space, especially in larger parks where target amenities may be farther from parking areas than some users are comfortable with. Include benches with high backs and arm rests to make sitting and standing from a seated position easier for those with hip or knee replacements and/or limited mobility. As mentioned previously, don’t forget shade options, especially in warmer climates.

A Recent NRPA survey found that 91% of residents who were asked are interested in attending nighttime park activities.68 Make it easier for them by providing good lighting options, minimally from the parking lot to the area where evening events will take place. Evening lighting can also help reduce crime. Harvard Park, in Inglewood, CA was once known for gang conflict at night, making it a less than desirable family destination once the sun set. The launched a program called Summer Night Lights, which not only added lighting to parks, but also programming such as athletics, arts, and family programs. The initiative has resulted in community comfort and increased usage, which has improved the park’s usership and safety.69

Public restrooms are an important amenity in a park. Many people will avoid using a park or revisit it less often if restrooms are either unavailable or inadequate. Providing a restroom for visitors is generally recommended if budget allows. Restrooms should be located near areas that people congregate, so before choosing a location, consider where people are entering, exiting, and gathering. If you have a large park, you may wish to consider multiple smaller restrooms instead of one large one. Locating near existing sewer, water, and electric connections can help save budget on new restrooms.

Be sure to consider traffic planning when striving to include all people. Lower income neighborhoods see a disproportionately high number of pedestrian fatalities.70 Older adults and children are also extremely vulnerable to being struck by a motor vehicle due to ambulatory ability and various other contributing factors.71 Pedestrians struck by vehicles traveling at 40 mph die as a result 80 percent of the time. When struck by a vehicle traveling 20 mph, pedestrians survive 90 percent of the time.72 Slower speeds, safe crossings and continuous sidewalks are key ingredients for connecting parks to the people who need them the most.

To be effective, we must look at building intergenerational spaces in two ways. First, existing parks must be evaluated for their intergenerational settings. According to one study,73 most cities have an average of 18,000 acres of parkland within their borders. These cities have a great opportunity to evaluate usage by residents and leverage these existing assets to create parks that appeal to intergenerational users. Additionally, planners and advocates may need to think creatively and look for opportunities to create new parks in unconventional spaces, to grow capacity for intergenerational recreation spaces within walking distance of where people live. Most importantly, to create truly intergenerational settings, it’s essential to avoid “cookie-cutter” park design and engage the local community as advocates and contributors. Utilizing input, creativity, and innovation in park design can help focus a community’s recreational activities to intergenerational ones that are appropriate for all. Considering landscape detail and infrastructure are both key components of success, as is ensuring the people who will use the park have input into what features are important to them.

There are many ways to begin implementation of intergenerational settings in communities. Pulling a group together to work on community assessments, feedback, and a specific set of outcomes for people of all age groups is a strong start to creating shared goals, and offers hope of making allies out of competitors for public attention and public resources. Every group has its own interests and it’s the challenge of park planners to meet those needs and expectations to adequately serve the population they represent, as well as show support and commitment. In a survey from Generations United and the Eisner Foundation, it was determined that 89% of Americans think serving multiple generations in the same space is a good idea. Additionally, 82% feel multigenerational spaces are a good use of tax revenue.74 Forge partnerships between like-minded organizations that may be able to help further the mission. Senior centers, hospitals, senior living, day cares, schools, and universities are just a few potential partners.

Advocates also need to challenge local leaders to champion the effort and help prioritize intergenerational use of outdoor spaces, and begin gathering answers to important questions, like:

• How do we include opportunities that intentionally promote intergenerational connection, not just parallel age use?

• What is the best way to train our staff to encourage intergenerational activity?

• How do we shift our mindset to think of people of all age groups as community partners with valuable resources to share?

• How do we fund investments in these critical spaces, while investing in the surrounding community itself?

• How can we work to establish intergenerational policies, standards, and best practice centers of excellence to help make implementation easier?

It makes sense to invest in shared sites.

89%

Nearly 9 in 10 (89%) Americans think that serving both children/youth and older adults at the same location is a good use of resources.

82%

A majority (82%) of Americans would support their tax dollars going towards the creation of a facility that serves both children/youth and older adults in their community.

73%

About three quarters of Americans (75%) think the government should appoint a person/group of people specifically responsible for creating opportunities (e.g. facilities, programs) for children/youth and older adults to come together.