Designing Play Environments that Integrate Manufactured Play Equipment with the Living Landscape

© 2009 PlayCore, Inc. and Natural Learning Initiative, College of Design, NC State University.

NatureGrounds and Putting Nature Into Play are trademarks of PlayCore

Proudly Sponsored By:

PlayCore believes that play enriches lives and as a company culture, we are committed to enriching play and fitness for children, families, and communities. We believe innovative programs like NatureGrounds are critical for challenging and inspiring the future innovation of play environments across our nation. The Natural Learning Initiative team members at the College of Design, N.C. State University, are invaluable partners in this quest. Their research, passion, experience, and technical expertise for bringing the living landscape into the manufactured play environment has allowed us to combine our efforts and truly offer the best of what we collectively know about both worlds. We hope that this guidebook, the best practice principles, and the multitude of on-line resources will be valuable for your community and that they will be a catalyst for impacting the way our children are able to play in nature at their community school and park playgrounds.

Research, documentation, and manuscr pt preparation by the Natural Learning Initiative:

Robin Moore, Dipl.Arch., MCP, ASLA, Director

Nilda Cosco, PhD, Education Specialist

Julie Sherk, MLA, RLA, ASLA, Landscape Architect

Brad Bieber, MLA, Design Associate

Shirley Varela, BA, Project Coordinator

Nataliya Gurina, graduate student assistant

Heather Vickery, graduate student assistant

Julia Murphy, undergraduate student assistant

PlayCore representatives that have supported this initiative.

Others who have assisted, both individuals and organizations.

Publ cat on des gn Humphrey Creative Co Ltd

The goal of the NatureGrounds program is to create innovative play environments that allow children, families, and communities to experience the many benefits of playing surrounded by nature.

Bob Farnsworth, CEO

Bob Farnsworth, CEO

The purpose of the NatureGrounds gu debook s to raise awareness and provide education about some considerations for a natura ized playground; it s not to be cons dered as an all inc usive resource

Please refer to the manufacturer specifications and safety warn ngs, which are supplied with the playground equipment, and continue w th normal safety inspect ons Safety goes beyond these comments requires common sense, and is specific to the playground involved Wh le our ntent is to prov de general resources for reconnecting chi dren and families to nature on playgrounds, the authors and program sponsor d sclaim any iability based upon informat on conta ned in th s publ cation Site owners are responsible to inspect repair, and ma ntain a l equipment and surfaces and manage site specific supervision sight ines, andscaping and safety requirements The Natural Learning Initiat ve, PlayCore, and its divis ons provide these comments as a publ c serv ce in the nterest of integrating nature into the p ayground while advis ng of the restr cted context in which it is given

Remember when time stood still as you played outdoors with best friends, enjoying the wonders of the world around us? We learned to interact with each other and our natural surroundings climbing trees, swinging on branches, playing games, or enjoying the quiet contemplation of leaves floating down a stream Elements of nature created magical expressions of childhood musings about the world.

Like children throughout the ages, we experienced the universal childhood delights of discovery and fascination set free by boundless imaginations and unstructured play in nature even in a few square feet

New health research recognizes everyday outdoor play in nature as a powerful preventive strategy for healthy childhood development including protection against childhood obesity.

A generation ago playing outdoors in nature was usually taken for granted, but times have changed Now, nature must be deliberately designed back into children’s lives In today’s urban and suburban environments, natural spaces are often too remotely located for visiting on a regular basis.

The Natural Learning (NLI) has conducted several studies that support the benefits of playground naturalization. The benefits and findings listed throughout this guidebook are derived from studies at one or more of the following research sites:1

1 The Environmental Yard, Washington Elementary School, Berkeley, C A , where study results showed play activity equally divided between community-built play structures, a hard surfaced games area, and a richly diverse, custom-designed nature area. These findings suggests that children enjoy a mix of permanent, anchored play structures, open areas, and natural settings

2 Blanchie Carter Discovery Park, Southern Pines Primary School, N C , which demonstrated the attractiveness of a playground containing a mix of manufactured and natural elements.

3 Kids Together Playground, Cary, N C (see case study, pages 7–9)

4 Research at a variety of childcare centers throughout North Carolina produced findings, which showed that higher levels of physical activity are supported by curvy pathways, anchored play structures, open areas, and compact layouts A further study demonstrated that children were more active in playgrounds where equipment and nature were integrated or “mixed.”

5 Bay Area Discovery Museum, Sausalito, C A , where study results demonstrated the attractiveness of settings designed for socio-dramatic play.

More information about these studies can be found at www.NatureGrounds.org.

Kids Together Playground, Cary, NC, intentionally designed as a naturalized facility, provides diverse play opportunities for children and families. The site continues to offer equally rich research opportunities.

The industrial playground model based solely on manufactured equipment is being reconsidered

A greater diversity of play opportunities is desired to extend curricular activity in schools and to meet the needs of a broader range of children and their families in parks. The integration of natural components helps fulfill these needs as well as creating richer play experiences for all users

Contemporary playground components are manufactured to meet high quality industrial design standards of health and safety. Constant upgrading and innovation are recognized characteristics of the playground industry National injury statistics show compliant playgrounds to be much safer than other everyday childhood environments

Playground safety, which has been the focus of playground design for the last fifteen years, has reached the point where children may find playgrounds boring and therefore not attractive for everyday use or for repeat visits

To counteract this trend, naturalization is an effective strategy to stimulate, motivate, and encourage children’s play and to increase the attraction of playgrounds for children and caregivers

Playgrounds cannot fully eliminate risk and indeed should provide children with opportunities to engage in healthy risk taking and activities that provide developmentally appropriate challenges. On the other hand, providing safer environments must continue to be a priority with every effort made to reduce unforeseen hazards.

Naturalization adds value to play equipment structures by enhancing their visual quality as focal points, thereby attracting children outdoors to use parks and school grounds Equipment, combined with natural elements, tells children that playgrounds are their special places The added comfort and aesthetic enhancement of nature also encourages accompanying adults to become enthusiastic users

Naturalization strategies and the best practice principles outlined in this guidebook offer a new, alternative paradigm for the playground industry, responding directly to the need for children to be outdoors engaged with nature.

Inspired by Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods, a grassroots movement advocating outdoor play in nature is growing across the USA and Canada, driven by parents, environmental educators, recreation and health promotion professionals, naturalists, and others. Naturalized playgrounds can support the outdoor play in nature movement in several ways:

• Play structures are heavily used by children, as demonstrated by NLI behavior mapping studies of actual use of school grounds and community parks designed to high standards of best practice.

• National, state, county, and municipal “children and nature” and “active childhood” community initiatives and legislation are focusing attention on the spaces of children’s daily lives, including playgrounds.

A mix of manufactured and natural play components creates an inclusive, friendly atmosphere where all ages feel comfortable and welcomed. If playgrounds are attractive to adults, they will stay longer and return more frequently.

• Innovative projects that promote nature play generate positive press and new funding streams to help implement naturalization initiatives

• “Mixed” play environments of equipment and natural components are more attractive and comfortable for adults. As a result, caregivers may spend more time outdoors with their children

• Well-designed playgrounds are a primary attraction for families using neighborhood and community parks. Naturalization adds visual interest, shade, and comfort resulting in

sustained repeat visits, a relaxed and playful social atmosphere, and growth of community social capital

• Users of all abilities discover a wider range of play opportunities in naturalized playgrounds These inclusive, universally designed environments attract multicultural families with members of all ages

• Curvy pathways weaving around and connecting equipment and natural components provide attractive, accessible, active settings for children, and social strolling by adults.

• Naturalization provides new opportunities for nature-based professionals such as naturalists, environmental educators/programmers, artists, playworkers, animators and volunteers to offer rich outdoor education and recreation programs for a wide range of children.

Play value recognizes that different types of play environments stimulate different forms and amounts of play

• Plants increase the diversity of social, construction, symbolic, dramatic, and physical play and related learning opportunities by encouraging children to explore and discover the wonder of the world around them

• Plants improve natural habitat conditions for wildlife species that fascinate children such as butterflies, caterpillars, ladybird beetles, and salamanders.

• Selected plants can attract songbirds to add sensory appeal to the playground.

• Plants offer sensory stimulation by providing sounds, textures, tactile interaction, fragrance, and visual interest

• Trees, shrubs, and flowering perennials increase playground aesthetic appeal, which stimu-

Naturalizing a swing use zone can have a dramatic impact on this highly utilized element of play. Trees were installed in small planting pockets, enclosed by curb edging, between and in front of the extended swing use zones. After five years (lower photograph), mature trees offer shade and a sense of enclosure to the space, which has become a place where adults can play with their children or sit, relax, chat, and watch the ever-changing activity. The treatment of this area with small “planting pockets” was simple, yet had a dramatic effect.

lates higher levels of use, a greater variety of play behavior, increased social interaction, and diverse habitat for wildlife

• Plants respond to seasonal change and add novelty and visual interest, which makes playgrounds more attractive and interesting to children and adult caregivers. This means adults are more likely to take children to naturalized playgrounds, spend more time there, and return for repeat visits

• Increased play value is a primary measure of community benefit for public funds invested in naturalized playgrounds

Integrating manufactured play equipment with natural components directly addresses health promotion by extending the range of options for children’s social, physical, and cognitive behaviors. Evidence of the health effects of outdoor play redefines naturalized playgrounds as preventive health assets that support active lifestyles in children, helping them avoid the negative health consequences of sedentary behavior. Additional benefits of playground naturalization include the following:

• Naturalized playgrounds increase diversity of play opportunities, thereby supporting social interaction and physical development of a wide range of children. Diverse play settings meet individual needs according to stages of development, learning styles, personality types, friendship patterns, and culture

• Children in nature are enaged in more creative and cooperative play.

• Naturalization provides broader inclusion of children of various abilities and increases social interaction between children with different socioeconomic and ethnic/racial backgrounds

• More creative play opportunities around play equipment can reduce social conflict on multi-use structures where crowding and boredom can increase the potential for bullying and the risk of slipping or tripping

• Increased levels of physical activity result from chasing and hide-and-go-seek games stimulated by topographical variety, curvy pathways, and shrubs and shade trees located around manufactured equipment This may reduce the possibility of children running on the equipment, which is discouraged by the industry.

• Naturalized playgrounds are aligned with education philosophies that consider the outdoor environment as an educational resource supporting child development as a holistic psychological, social, and cognitive process Naturalization provides hands-on experiences and opportunities to bring classroom learning outdoors.

• Gains in student competence, social studies, science, language arts, and math occur for children attending schools with outdoor classrooms

• Heightened sensory stimulation, exploration, and discovery of natural objects and phenomena stimulate active learning, creativity, and imagination

• Environmental educators see nature play as a key strategy for engaging children in urban communities with the experiential richness of the natural world. Opportunities for extending

learning processes outdoors increase options for meeting state-mandated curricular objectives, certifications, and learning through play

• Changing seasons and daily natural environment dynamics contribute to novel play experiences for children.

• Deeper emotional attachment to nature and increased understanding of the natural world by children can increase long-term environmental stewardship as adults

In summary, naturalized playgrounds can be designed, managed, and programmed to integrate three crucial agendas for children’s healthy development: active living; educational success through engagement with diverse, living environments; and healthy social and psychological development through spontaneous, creative play.

In addition to the foregoing research results, recent studies provide powerful evidence across many child development domains underscoring the importance of engagement with nature for healthy childhood Findings suggest that exposure to nature: 2

• Reduces attention deficit disorder symptoms in children as young as five years old

• Produces feelings of peace, self-control, and self-discipline within inner city youth, particularly girls.

• Reduces stress in children through contact with plants, green views, and access to natural play areas

• Increases children’s ability to focus and enhances their cognitive abilities.

Naturalization increases playground plant diversity, a primary principle for healthy ecosystems. Not only is this good for the environment but it offers environmental educators, teachers, and programmers natural material to work with to motivate learning and help bring curriculum outdoors.

Naturalization increases healthy behavior among children by making manufactured play environments more intriguing and visually appealing, thus stimulating exploratory behavior, social interactions, and active play.

• Develops capacities for creative problem solving, as well as intellectual and emotional development

• Motivates children to be more physically active, more aware of nutrition, more civil to one another, and more creative by experiencing diverse, natural school playgrounds.

• Enhances self-esteem, self-confidence, independence, autonomy, and initiative in teens.

• Provides sun protection and skin cancer prevention

Playground naturalization can provide an important community-based demonstration of environmental stewardship and sustainable site design practices. Research indicates that when a child explores nature outdoors with an enthusiastic parent, grandparent, or other trusted guardian, the child is more likely to take action to benefit the environment as an adult

These objectives support the national Sustainable Sites Initiative 3 by improving ecosystem health, enhancing wildlife diversity, demonstrating natural drainage systems, and reducing the carbon footprint of playgrounds

Sustainable site development is mandated by a growing number of municipalities and is expected as a normal aspect of best practice and responsible development In this regard, naturalized playgrounds can contribute to reducing the heat island effect in cities by increasing the tree cover, which at the same time contributes to reducing the carbon load and improves air quality.

Playground naturalization, especially when employing hardy, native plants, can dramatically improve wildlife habitat conditions for local flora and fauna, particularly birds and butterflies, which can animate playgrounds with color, movement, and birdsong.

Well-designed stormwater drainage systems such as rain gardens and naturalized swales integrated into the playground area improve local ecosystem quality by increasing plant and animal diversity Naturalized stormwater systems ensure that the maximum amount of water percolates on site to recharge the groundwater. This in turn increases natural irrigation to plant roots to keep plants healthy

Naturalized stormwater system design is a specialized area of interdisciplinary professional expertise linking landscape architecture and civil engineering Cooperative Extension Service County Offices, university departments of civil engineering, landscape architecture, or the local chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects can offer professional advice

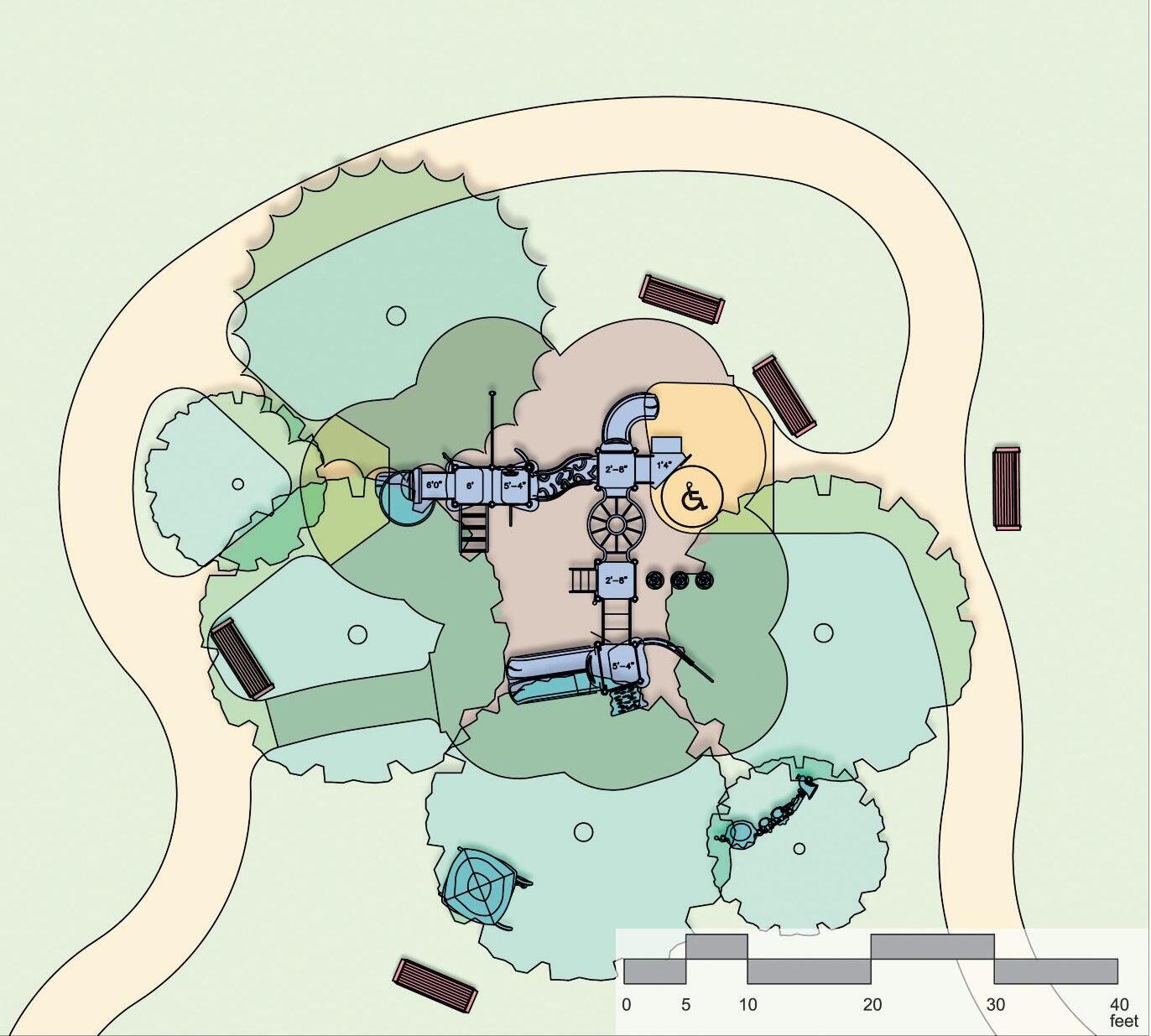

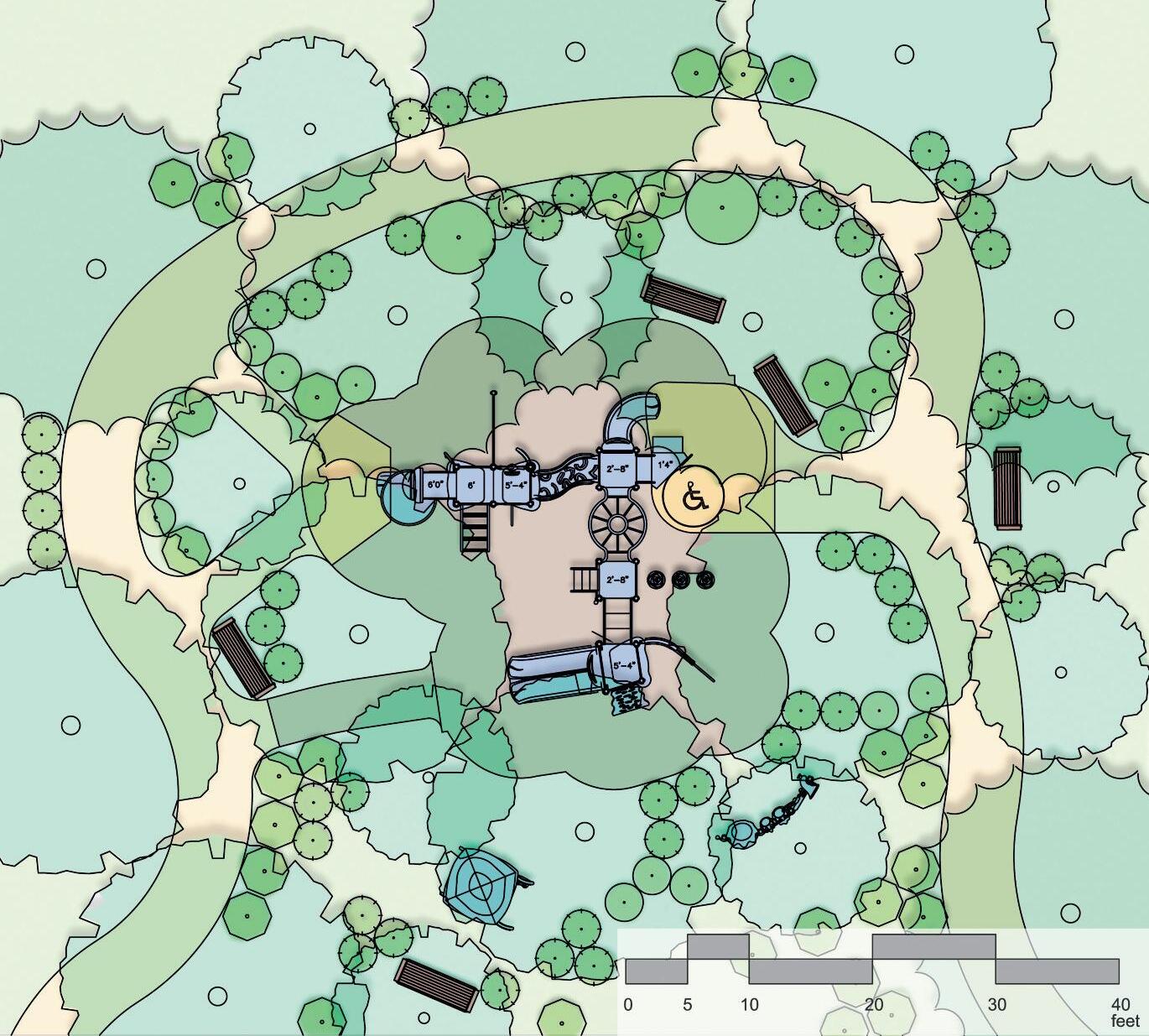

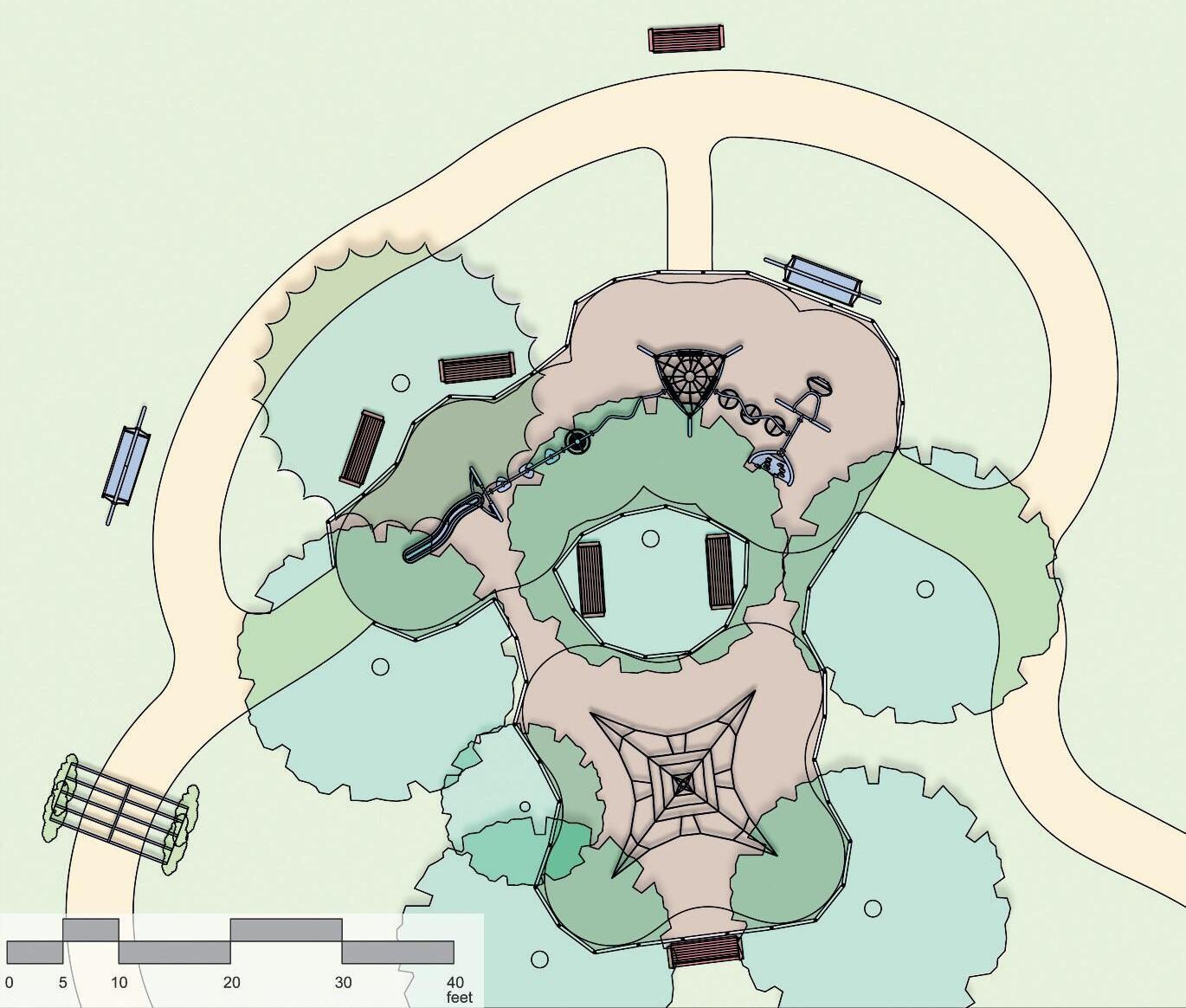

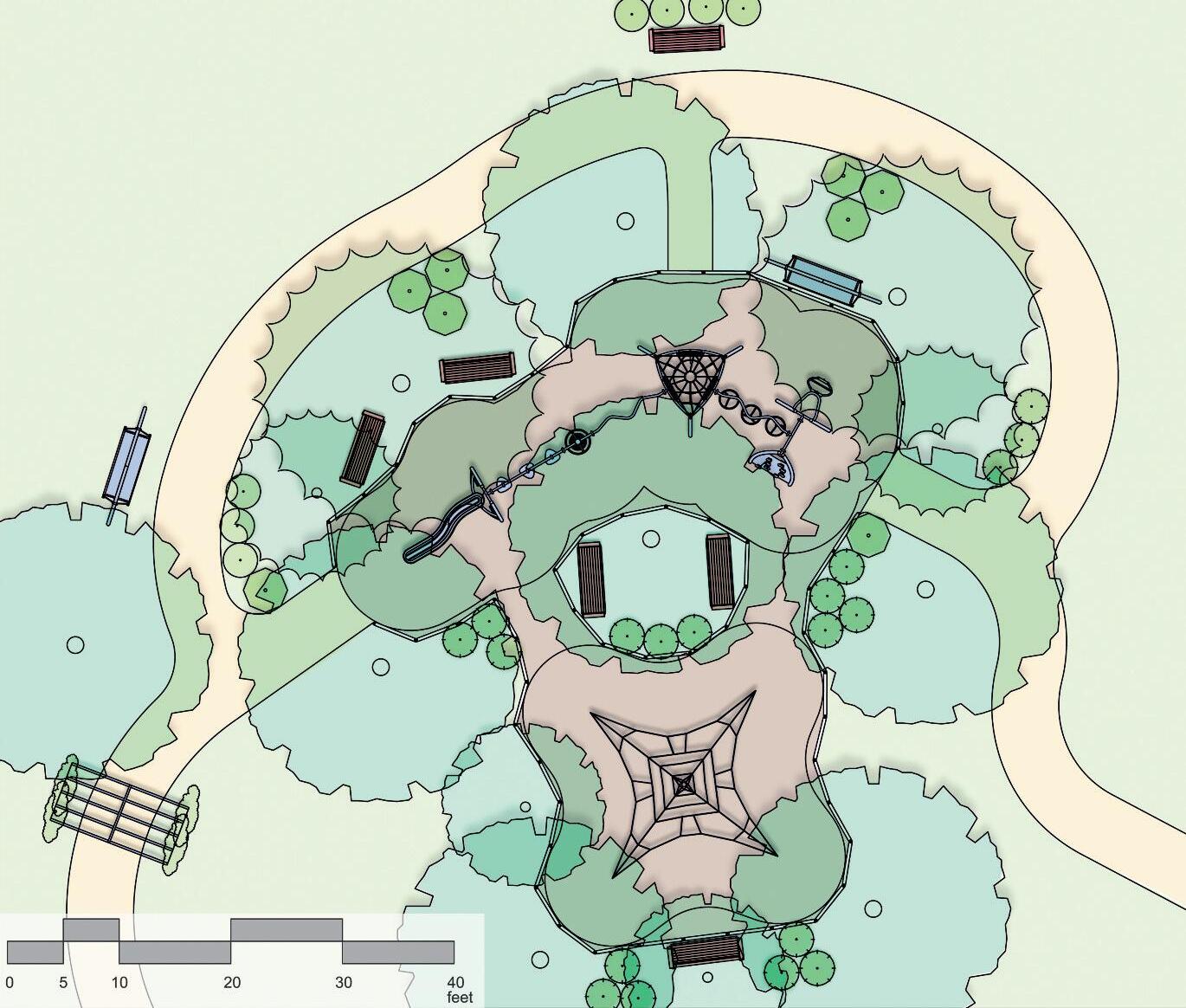

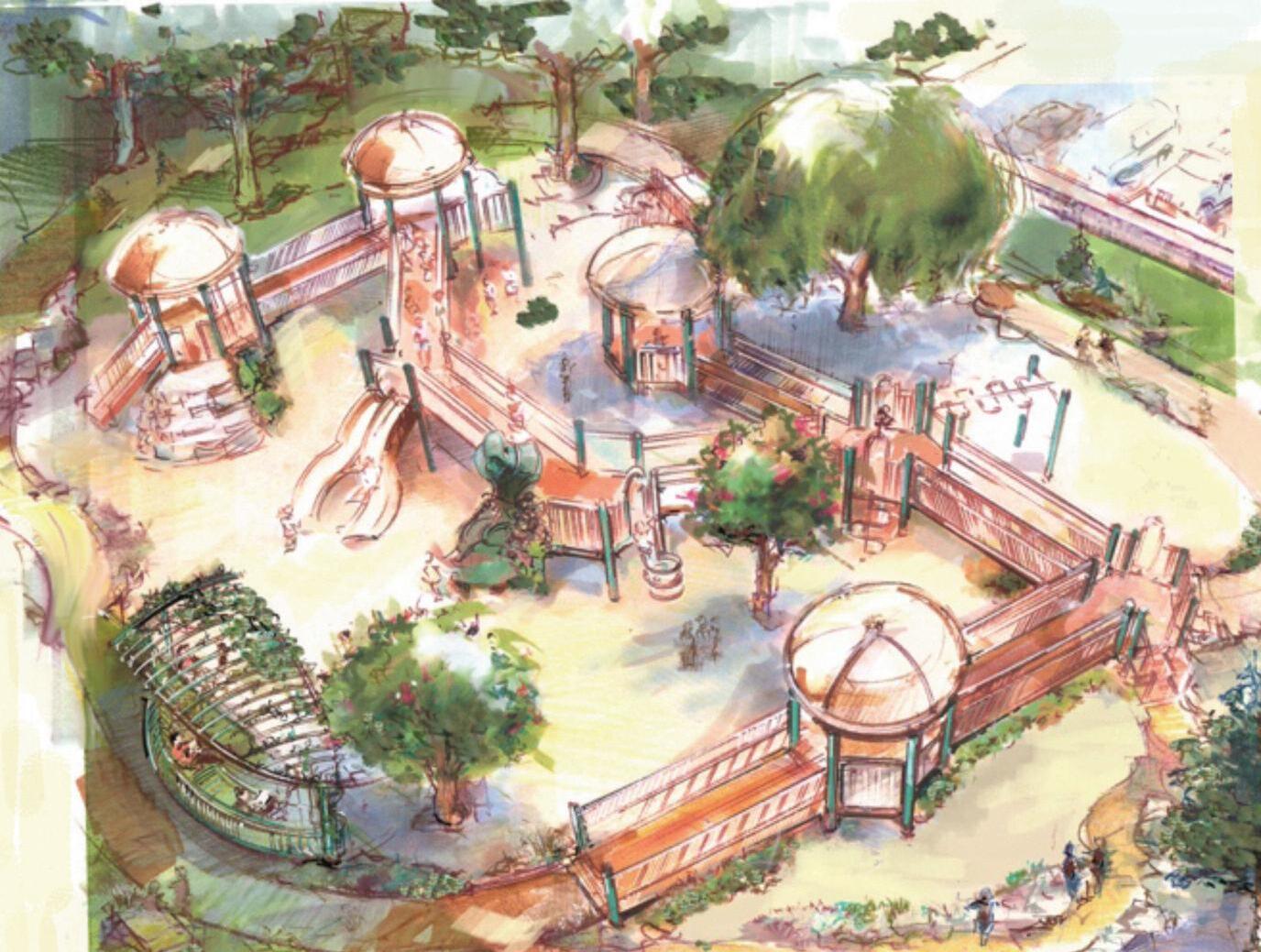

Kids Together Playground (KTP), Cary, North Carolina, is an example of the new naturalization paradigm, which integrates manufactured play equipment and the living landscape This universally designed 1 3⁄4 -acre family recreation facility contains many innovative settings and features Design started in 1994 with community workshops involving children and adults Several years of fund-raising preceded the opening in June 2000 at a cost of 850,000 U.S. dollars, excluding ancillary site works 4

By integrating manufactured play equipment and natural components, KTP accommodates a wide

Stormwater management is a critical aspect of playground design. The primary goal is to keep rainwater on the site so that it percolates back into the ground to replenish the ground water, which is best sustainable practice. Rain gardens, as pictured here on a school ground, are a solution that creates a rich wetland habitat by increasing plant and animal diversity, as well as offering environmental education opportunities.

spectrum of recreational needs, including gross and fine motor development, sensory stimulation, resting, nature contemplation, social gathering, and a friendly environment for children and adults with various abilities Research indicates that users found the playground particularly attractive, and different from other regional destinations, particularly for family members with disabilities. Due to the naturalization and social atmosphere, all children could play comfortably together at ground level. This was viewed as more important than the accessibility features of equipment.

Community artists contributed substantially to the overall aesthetic appeal of the playground by designing benches as art objects. A dragon-like play sculpture (KATAL “Kids Are Together At Last”) rising out of the hillside also was the work of a local artist

Research findings indicate that KTP attracts multigenerational, multicultural users seeking satisfying family recreation experiences. The mission-driven design created a community play environment supporting the needs of all family members, including children, parents, grandparents, caregivers, and friends regardless of ethnic or racial background KTP also serves community groups such as childcare centers, special education programs, and summer camps. Those involved in implementing the project were committed to high quality design as a crucial vehicle for bringing together all sectors of the community.

KTP demonstrates the role of parks as communal backyards for children and other family members, where they can play freely together and be exposed to experiences that may be unavailable in more constrained domestic settings

Because the space is bounded, with few entrances, KTP provides a secure place for natural child development by allowing safer access to an ever-widening range of experiences for children alone, with peers, or accompanied by caregivers KTP constantly challenges children to explore further, while at the same time responding to parents’ differing levels of tolerance towards children’s risk-taking.

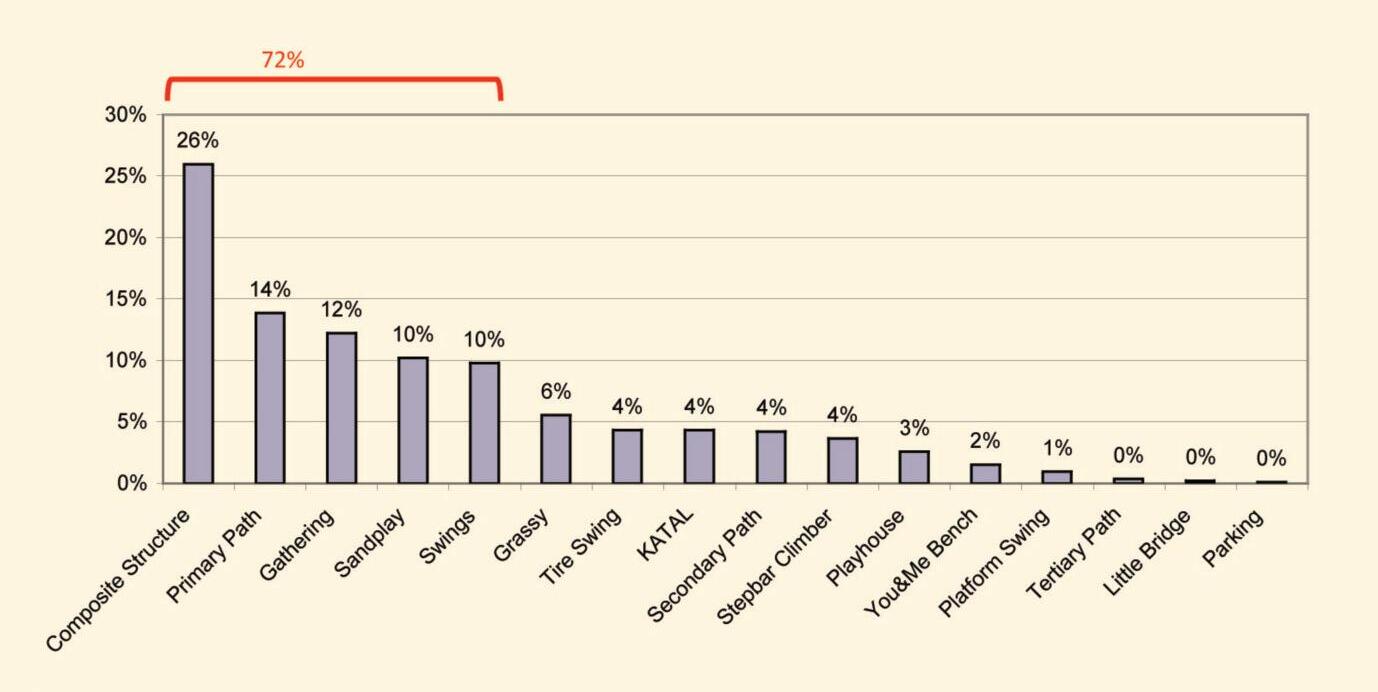

The most heavily used settings by children (measured by behavior mapping) were composite structures, swings, primary pathways, gathering areas, sand play, and the open lawn area with KATAL The universally designed compact zone with sand play, accessible, horizontal equipment, and swings, joined by a curvy path, was the most heavily used area of the playground.

The most efficient site utilization (Use/Space Ratio) was exhibited by the composite manufactured equipment, sand play settings, a stepbar climber, and swings

KATAL, the ground-level dragon sculpture stimulated the most playful interaction between adults and children

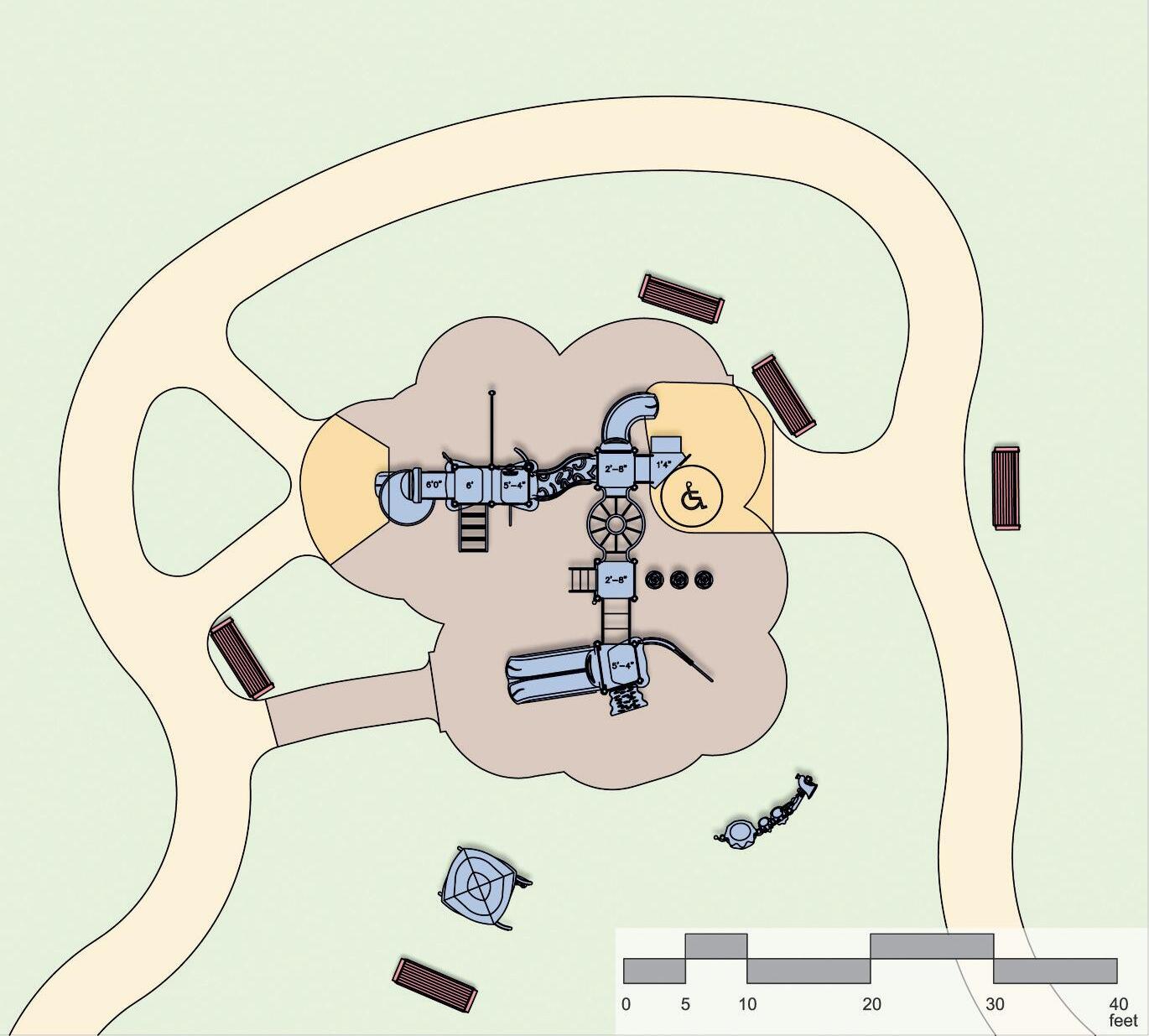

KTP children’s behavior map shows the relative attraction of the compact active play area (top left). The area includes swings, a play structure accessible to a higher level, and sand and water play, interconnected by a wide, curving, primary pathway. This area accounted for 45% of children’s use of the playground.

KTP demonstrates the community value of high quality, compact, diverse, naturalized family playgrounds that not only support child development but also provide crucial vehicles for inclusion because they can stimulate free flowing, positive interaction among park users of all abilities

An analysis of KTP children’s behavior map shows distribution of use across different types of play settings, clearly showing that almost three-quarters (72%) of use occurred on composite play structures, pathways, social gathering areas, sand play, and swings.

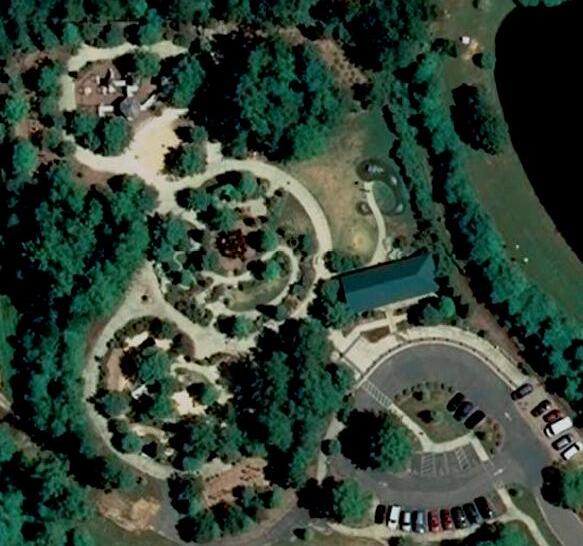

KTP from the air (2007) contains three main play areas, each accessed by a 10-feet wide curvy, primary pathway. The central area, designed for school-aged children, provides a low hill surmounted by a vertical play structure. Secondary and tertiary pathways are clearly visible within the area. The lower left area, designed for families with preschoolaged children, is bounded by a low fence so parents feel secure. The area contains playhouses for dramatic play, various active play elements, and sand and water play for additional sensory experiences. Upper left, an area designed for active play contains an easily accessible play structure, swings, and accessible sand and water play. An entry plaza (photo left) welcomes visitors from the parking area and connects to the bathroom/picnic shelter to the right. The head, tail, and two humps of KATAL the dragon can be seen rising out of the sloped lawn above the building.

Best practice in playground design is an outcome of informed consideration of three main guideline factors: 1. Playground siting (where and how it is located in relation to its functional surroundings); 2. Identification of playground users and consideration of their particular needs; and 3 Site layout to configure design components in a multitude of ways through innovative design. Careful, balanced consideration of these factors leads to a cost-effective, highly valued, well-used resource in the community Each factor is translated into the following best practice principles for consideration as you begin designing or retrofitting a naturalized play environment

This playground (left) was sited so that users could benefit from the existing trees and the stream flowing along one edge. Here, children can enjoy the universal pleasure of natural water play while accompanying adults can relax on adjacent park benches.

Access to this playground (above) was implemented by creating a landscaped berm to lift the accessible route from the school building to the main platform level of the play structure, utilizing existing site topography. Donor bricks along the pathway recognize major funders of this project.

Locate naturalized playgrounds in relation to site features and functional surroundings

Access

• Locate the playground within easy walking distance via accessible routes to parking area, recreation or school building, and important facilities such as bathrooms and picnic shelters

• Connect the playground to an existing park trail or school ground pathway system

• Connect the playground area to local greenways or trail systems for pedestrian or cycle access from the surrounding community

• Consider topography as an important asset in playground design.

• Appreciate any change in topography as it will attract children and stimulate running up and down and rolling, which children love

• Conserve topographical variation as an existing site feature or create playful topography by design.

• Embed slides into slopes for unique aesthetic and play value qualities

• Offer elevations as children are attracted to the “prospect and refuge” quality of higher elevations.

• Create topographical variation (if not present), which is easier with natural settings as they do not require as much flat surface as most equipment settings

• Align topographic features with creative play equipment to facilitate unique opportunities for creative and socio-dramatic play and physical activity.

• Ensure well-designed surface drainage systems as they are essential to the functional success of naturalized playgrounds

• Employ contemporary landscape engineering practice, which offers innovative solutions such as rain gardens and vegetated swales to accommodate stormwater surface runoff These components can add play value, aesthetic enhancement, and educational opportunities to naturalized playgrounds.

• Make every effort to conserve existing delineated wetlands as added natural value, which may be required by law

• Consider mature trees as they are crucial site assets that add shade and aesthetic quality to the site making it attractive to more users

• Make every effort to conserve trees and other significant vegetation such as existing woodland.

• Appoint a certified arborist to determine health of existing trees

• Seek professional advice from a licensed landscape architect or landscape contractor concerning appropriate construction methods near mature trees.

• Do not encroach with new construction (including use zones) into the dripline of existing mature trees as the risk of root damage will increase Roots may spread beyond the dripline If disturbed during construction, they should be cleanly pruned, particularly roots more than an inch in diameter

Shade trees incorporated into the playground layout offer children a shady, comfortable spot for socio-dramatic play on the edge of the use zone.

Combining a wide primary pathway, park bench, and other social gathering areas support intergenerational family birthday celebrations and meeting opportunities where users linger and socialize.

Orientation in relation to the sun

• Locate manufactured playground equipment close to large, deciduous shade trees (while following preceding “Mature trees and other significant vegetation” guideline) so that users are both protected from direct rays of the sun during hot summer months and exposed to the warmth of the sun at other times of the year

• Locate manufactured playground equipment on the north side of mature shade trees to maximize shading effect.

Identify user groups and design to universally support their needs

Research demonstrates that naturalized universal design of playgrounds produces an environment that is more attractive to a diverse group of people Naturalized universal design attracts higher use levels by multigenerational family groups, with children in strollers as the major beneficiary, as well as people who use wheelchairs Naturalization helps create playgrounds that are attractive and usable by all people no matter their age, cultural background, economic status, and level of ability or personal skill Naturalized playgrounds can become social crossroads in the community

Design for multigeneration use: Early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, and families, including adults of all ages

Early childhood: Provide a separate, enclosed area for families with toddlers/preschool children in parks. It is important to emphasize naturalized dramatic play settings, sand and water, music, cozy spots, motor play, and free exploration of nature in both school grounds and park playgrounds

Middle childhood: Provide a full range of naturalized settings in parks and school grounds, including gross motor play equipment, play with sand and water, socio-dramatic play settings, and open areas for multipurpose play

Adolescence: Provide naturalized play areas in public parks and school grounds that welcome adolescents Consider play equipment options that provide developmentally appropriate challenge and interest along a continuum of physical and social play. Research suggests that female adolescents enjoy the social ambience of naturalized playgrounds because they offer “prospect and refuge” allowing withdrawal from the center of activity while still enjoying people-watching. Other adolescents may enjoy ball games Like any other age group, adolescents are attracted to

the natural environment.

Adults: Provide naturalized play areas that offer comfortable social gathering spaces for adult caregivers and universal design features that allow adults of all abilities to access and engage in play activities with their family Consider supervision needs for sight lines and security

Since parks cater to all ages, site plans should locate age group territories adjacent or overlapping each other. Similarly, school grounds should also include age-appropriate design specifications as recommended by the playground manufacturer Age appropriateness allows maturing children to explore play opportunities with each new visit and continue to acquire developmentally appropriate skills.

Design to bring families together

• Provide shady social settings with comfortable group seating for families (children, parents, grandparents, and other relations), who represent the bulk of park users.

Inclusive design ensures that children with special needs have equitable play opportunities with friends and family members. Swings are always a popular choice for children of all abilities. The elongated planting pocket creates a natural enclosure and cue to the users of the space.

• Offer tables and benches for picnics, reading, writing, or computer work as important design considerations for school and park playgrounds

• Consider comfortable, universally designed settings for birthday parties and other outdoor family celebrations.

Ensure design of inclusive environments for children and adults with disabilities

• Consider naturalization design to promote accessibility and usability for individuals that have physical, communication, social/emotional, sensory, and cognitive needs

• Playground naturalization adds value for children and adults with disabilities by diversifying the experiential landscape, catering to different learning styles, increasing play value, enhancing aesthetic quality, and improving comfort

• Many children can enjoy the natural ambiance of the site, including those who are interested in play experiences beyond manufactured equipment, those who have difficulty accessing components, or those who seek a continuum of sensory experiences

• Elevated planting systems and/or vegetation that grows to accessible heights can greatly broaden the variety of play experiences for children and adults using mobility devices

Design to promote physical activity

• Include developmentally appropriate playground equipment that stimulates higher levels of physical activity through a rich variety and developmentally appropriate continuum of swinging, spinning, sliding, balancing, brachiating, and climbing elements

• Add trees and shrubs to stimulate chase games by providing “bases,” cozy places, and objects to run around, encouraging children to become part of the play experience

Design to promote sun protection

• Consider adequate protection from the sun for children when they are physically active outdoors, especially during summertime in the middle of the day.

• Provide sun protection with manufactured shade structures, shade trees, or a combination of both

• Use large pergolas to support growing vines, in order to create naturalized shade in and around playground equipment zones

• Use integrated shade structures with tree planting in the same equipment zone When trees have matured and offer sufficient shade, shade structures can be removed. Several small shade structures as extensions of playground equipment are easier to integrate with tree plantings

• In cold climates ensure adequate sun penetration during the long, cold season by planting evergreen trees only on the north side of equipment settings

Design for community special events

• Successful parks and school grounds are attractive venues for community special events such as musical and dramatic performances, ethnic festivals, national holidays, reunions, family celebrations, etc

• For special events consider including multipurpose open lawns surrounded by shade trees,

In this park, the play area has been tucked between existing deciduous trees that offer lightly mottled shade in the summer and warming sun penetration during the leafless season, thereby increasing the level of user comfort.

benches/seating, and a stage. Depending on predicted use, stages may be large and elaborately furnished or simple raised platforms with modest accoutrements such as lighting

• In addition to accommodating special events, multiuse lawns support informal ball play and group games, which promote physical activity and social play.

• Even small multipurpose lawns (30 feet diameter or less) provide useful settings for active play

Plan for outdoor education and curriculum programming

• Naturalized playgrounds offer support for outdoor educational activities. The more diverse the environment, the more likely it will support and enhance the curriculum

• Naturalized playgrounds offer additional possibilities for school and park recreational programming, after school programs, community events, camps, etc.

Configure site layout to organize design components and network the play environment

Use entrances, pathways, and boundaries to structure the layout

• Entrances, pathways, and boundaries provide the basic site infrastructure of playgrounds in parks and school grounds.

• Entrances provide a welcoming sense of arrival They can offer social places with comfortable seating where family groups or friends may meet up before or after a visit An entry sign can express community values and a commitment to naturalization as well as being an art object For example, a vine-covered arbor can offer a message about commitment to naturalization.

There are many ways to design a welcoming sense of entry to a playground such as this vine-covered tunnel, which sends an immediate message to visitors, that natural components are an important part of the overall playground design.

The curvy path on this universally designed playground provides an accessible route to each setting. The mulch to the left and grassy area to the right are designed for phase two installation of trees and shrubs after fundraising efforts to create planting pockets along the pathway.

• Playground boundaries offer a sense of security, provide organization to the play area, and create natural enclosures, especially for preschool children Boundaries may be as simple as a vegetated chainlink fence (cost effective solution) or pockets of plantings between play areas

• Pathways function as the social arteries of playgrounds and school grounds. In large playgrounds containing several equipment settings, hierarchical networks of pathways (primary, secondary, and tertiary) offer maximum experiential choices to children of different ages and abilities.

Primary pathways are usually hard surfaced and wide (8ft to 10ft) to allow for side-by-side conversations of strolling groups including caregivers using strollers, individuals using mobility devices, and access for small service vehicles. Curvy alignments provide a sense of discovery (“What’s around the next corner?”) Placement of shade trees on the south side of primary pathways is a crucial method of moderating sun exposure and increasing comfort in hot weather

Secondary pathways with hard or soft surfaces (5ft to 6ft wide) allow users to explore “off the beaten track” in quieter social settings. Again, placement of shade trees on the south side of secondary pathways is crucial

Chainlink fencing can be naturalized to be less noticeable, while still providing necessary security. The fence line is set back from the edge of the primary path 3 to 4 feet, allowing space for varied flowering perennials. The fence provides a natural boundary to protect the plants and results in a beautifully rich border.

Tertiary pathways can be as narrow as 3ft with soft surfaces or stepping stones that allow children to explore nature and create their own adventures in the undergrowth around play equipment

• Research indicates that vigorous physical activity (especially running), which is important for children’s health, varies in relation to equipment layout. For example, closely clustered play equipment may stimulate less running compared to dispersed equipment configurations

• Consider interconnected, continuous, circular, hierarchical pathway layouts without dead ends, which facilitate running, chasing, and hide-and-go-seek games between dispersed play structures, thus increasing vigorous physical activity and adding active lifestyle benefits

• Connect the playground to the larger park or school ground pathway or trail system to expand the possibilities for active, mobile play.

• Provide seamless access from the playground to settings such as interpretive outdoor education, community gardens, gathering places, performance areas, and trails to increase walking or mobility.

A curvy path flowing through this woodland park setting has been designed to connect the parking area, walking trail, and playground, while providing an enhanced entry experience.

The entry to this enclosed preschool area is marked by a beautiful vine-covered arbor. Ahead, adult visitors see an inviting, shady spot for meeting their friends and socializing while their children play in a secure, bounded play area.

• Design landscaping along pathway routes, around and within the spread out features, to encourage movement and exploration by children

Integrate planting pockets

• Identify opportunities for installing small planting pockets between and beside manufactured equipment settings beyond the use zones

• Identify opportunities for elongated planting pockets as vegetated buffers between manufactured equipment use zones and pathways.

• See further discussion of planting pockets (pages 21–27)

Define play settings to maximize active, social, and sensory play opportunities along a developmental continuum

Design active play settings

• Recognize settings that promote active play as the most important because they motivate moderate and vigorous physical activity Examples include many forms of well-designed, manufactured play equipment that promote swinging, sliding, spinning, balancing, brachiating, and climbing

• Locate trees to shade active play settings so that children do not get overheated and dehydrated.

• Integrate active play settings into the living landscape as part of the play experience. Carefully install plantings under, around, and beside the play equipment to stimulate active play. Care must be taken to avoid plantings that could obstruct the use zones of dynamic play components like slides, swings, whirls, and overhead equipment

• Provide active play settings for toddlers/preschoolers in a separate zone where smaller scale equipment can support early childhood needs.

• Include shade trees as critical features for very young children.

In this play area, an engineered wood fiber safety surface provides a natural appearance to visually integrate the manufactured equipment and planting pockets located between the active play use zone and primary pathway.

Create socio-dramatic play settings

• Socio-dramatic play settings engage a wide age range of preschool and school-aged children Examples include play houses, music, vehicular play such as fire trucks, spring riders, etc

• Locate stages and decks as places where children can gather and create spontaneous dramatic play episodes These settings can be installed close to the ground or underneath upper deck areas

• Recognize that socio-dramatic play can occur in any type of play setting, including gathering spots with benches and tables as well as on and underneath manufactured play structures

• Install shade trees with related plantings that produce loose parts (leaves, nuts, cones) in socio-dramatic play settings to offer natural materials for children to play with.

Design sand play settings

• Accommodate a wide age range of users, including caregivers, by designing large sand play settings that offer rich sensory play experiences

• Include elevated components accessible to individuals using mobility devices or those that cannot bend or sit on low surfaces

Sand play settings should be designed to be accessible to individuals using wheelchairs, both children and adults, so they can actively play together.

Drinking fountains, garbage receptacles, and other site furnishings are important playground amenities and easy to naturalize.

• Install adequate shade in sand play settings.

• Add vegetation adjacent to sand play settings to provide natural loose parts to stimulate and extend imaginative play

• Integrate water in sand play settings so sand can be molded to extend play value

Include elements for hands-on water play

• Accessible, hands-on water play in playgrounds can be best provided with elevated troughs and tables with devices for children to manipulate the water flow Troughs and tables at various distances above ground provide for different ages and heights of children and increased accessibility for individuals using wheelchairs, other mobility devices, and older adults

• Alternatively, hands-on sand and water play can be installed at ground level with accessible diggers that can be accessed by individuals outside the sand and water area.

Include water for cooling, washing off, and drinking

• Provide water for cooling off in the form of showers or misters Devices can be activated by infrared sensors.

• Provide water for washing off (after sand or earth play) in the form of low level faucets, which can be activated by infrared sensors

• Include drinking fountains as an important playground feature and consideration throughout the play environment to offer accessible places for hydration.

Evaluate appropriate ground surfaces for naturalization, safety, accessibility, and play value

Naturalized ground surfaces

The most common natural ground surfaces are lawn turf and wood mulch.

Lawn turf is installed on clean, graded soil as commercially cultivated rolled out turf or turf cultivated from seed in-situ. In both cases, turf quality is influenced by the grade of underlying soil and adequate drainage Advantages of lawn turf include its natural quality and pleasant aroma. Disadvantages include vulnerability to wear and erosion where foot traffic is intense and the frequent mowing requirement during the summer months

Wood mulch is a highly versatile ground surface material, which can withstand heavy foot traffic It is a renewable resource and is ideal for surfacing around plants Disadvantages include the risk of being washed away by heavy rain (therefore it is unsuitable for slopes) and requirement of periodic replenishment.

Two types of safety surface are most commonly specified for play equipment safety zones: engineered wood fiber and poured-in-place rubber

Engineered wood fiber safety surfaces are manufactured from harvested timber (a renewable resource) and vary in size, shape, and texture according to the type of processing employed, and adherence to ASTM guidelines. Primary advantages are ease of installation, the natural visual appearance, and the unit cost Depending upon use, loose-fill surfaces require “topping off” or replenishment of approximately 25% of the material annually to maintain required depth for attenuation.

Poured-in-place safety surfaces are manufactured from granulated synthetic rubber bonded with a liquid polymer, which hardens to provide an even, resilient surface topcoat poured over an undercoat, laid on a concrete subsurface. Primary advantages include multiple color choice, the possibility of creating nature inspired designs in the surface, accessibility, and permanence after installation. It is easy for children to run and move on poured-in-place surfaces, which may increase the level of vigorous physical activity A disadvantage is the higher initial cost but it may be offset over time, as it does not need the topping off required with loose-fill surfaces.

Alternative surfaces like loose-fill rubber, rubber tiles and even attenuating turf products can also be considered for use under and around the play equipment

This playground, located adjacent to an existing multipurpose field, shows a successful combination of engineered wood fiber and synthetic safety surface tiles, which work well as a landing pad for the multiple slide element. Planting pockets add play value.

Poured-in-place safety surface can be used to create steeply undulating, ground level play surfaces, which would not be possible with natural surfaces.

Planting pockets

A range of possibilities is available for achieving phased naturalization in retrofit or new construction projects. Using planting pockets is a simple approach to integrating plants as closely as possible with manufactured play equipment, while still designing safer play environments that enrich the overall experience of users

• Planting pockets can be combined with freestanding playground equipment to become part of the play experience and to create natural boundaries.

• Planting pockets can be as small as one or two grasses or flowering perennials under the sunny edges of perforated decks (so rainwater can still get through)

• Planting pockets can be installed as individual trees within extended mulch/engineered wood fiber surfaces beyond equipment use zones, in effect within equipment areas. Large, multi-unit equipment layouts can be configured to integrate planting pockets

• Planting pockets can be ground level or installed as raised beds several feet across adjacent to equipment use zones.

• Planting pockets can be shaped to fit available space, for example to provide narrow, elongated planting buffers between pathways and equipment use zones Even a 24-inch wide planting pocket can support a variety of hardy perennial plants. Points of access to equipment use zones should be provided between planting pockets to avoid trampling

• Planting pockets can be created by integrating equipment with naturalized berms

• Planting pockets can be combined with seating and picnic table social settings to provide patches of comfortable shade for users

Integrating planting pockets into playgrounds is an effective approach to achieving naturalization while providing plants as part of the play experience. In this playground, the entry promenade (left) is lined with planting pockets wide enough for trees, which in a few years will become a shady, green tunnel. A large tree in the central, circular planting pocket will soon fill the space with a lush canopy. In the foreground, curved planting pockets visually define play settings. Planting pockets can support a variety of flowering perennials and shrubs, and decorative grasses.

Planting pocket criteria

Planting pockets outside use zones:

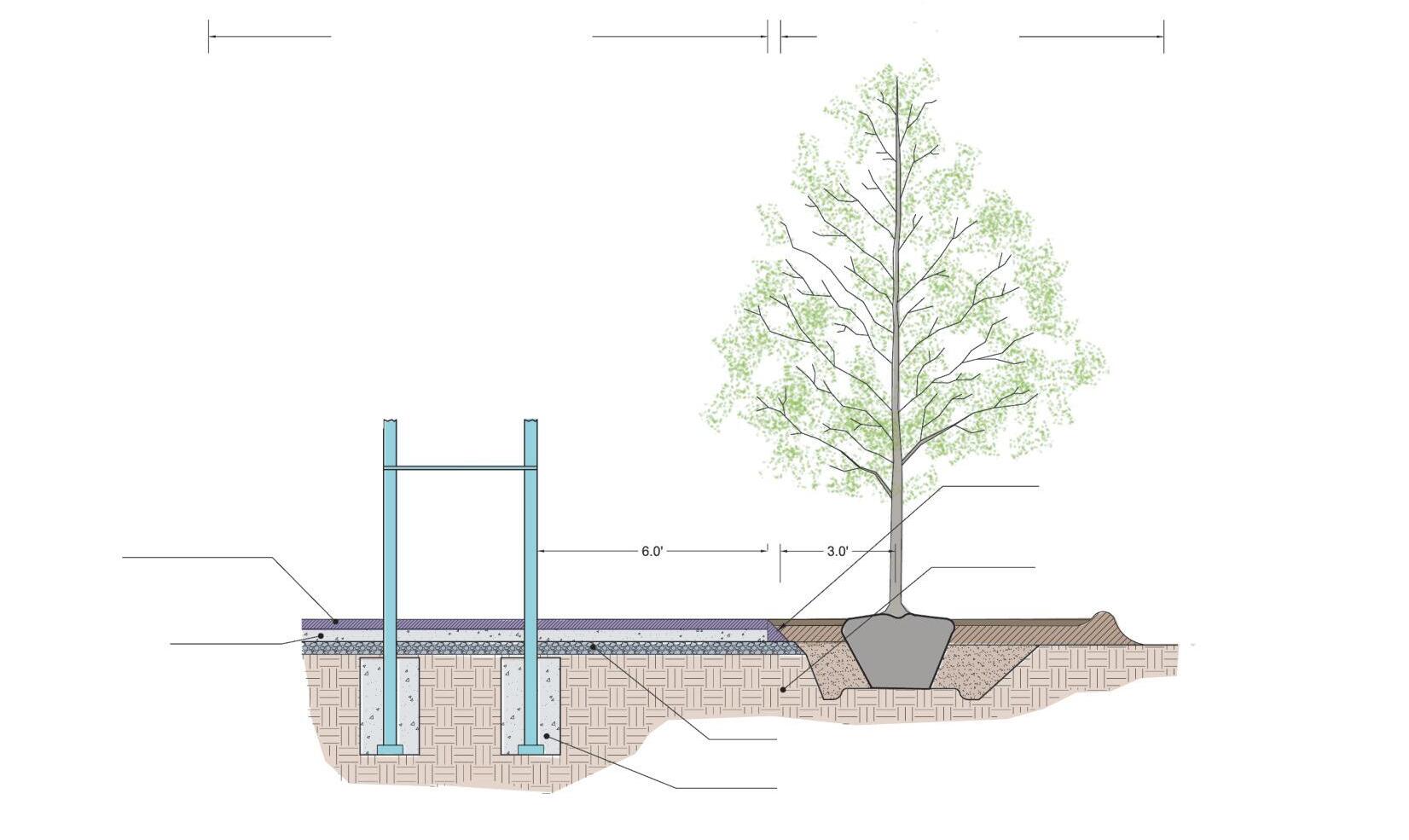

• Plant trees at least 3ft from use zone surfacing and other paved surfaces (i e , paths, sidewalks)

• Shrubs and ornamental grasses can be planted more closely, with their expected mature size reaching the edge of the use zone

Planting pockets between adjacent use zones (where possible, design layout with planting pockets):

• A tree planting pocket should be at least 6ft x 6ft (determined by the 3ft use zone planting buffers of the two adjacent use zones). This also provides enough root space for healthy

This six feet wide planting pocket is large enough to support the growth of a medium-sized birch tree with lovely weeping branches and a small evergreen tree, while still honoring appropriate use zones.

tree development.

• A planting pocket designed for shrubs and grasses should be at least 4ft wide to allow space for the plants to mature without encroaching on the use zone

Planting pockets under the edges of decks:

• Soft grasses and vines (no branching plants) can be planted under decks and bridges that have a minimum height of 3ft

• Space beneath decks and bridges should be sufficient for plantings to reach expected mature height

Planting pockets along low elevation platforms or ramps:

• Soft grasses and vines can be planted along low elevation platforms and ramps (up to 2 feet in height), but must be outside the use zones of adjacent manufactured play equipment

• Trees and shrubs can be planted at least 3ft from low elevation platforms or ramps as long as they are outside the use zones of adjacent manufactured play equipment.

Planting pockets around freestanding play equipment with no designated play surfaces where children's feet remain in contact with the ground (like play houses, telescopes, talk tubes, music, sand and water tables, etc.):

• Adjacent plants should allow a minimum of 3ft of access around all playable surfaces of freestanding play equipment.

Shading priorities

If a limited number of trees is available, place trees along the southern 3ft use zone buffer If additional trees are available, place them as close as possible to the northern 3ft use zone buffer without violating minimum spacing rules Necessary distances between trees may require that trees along the northern edge have an additional offset from the use zone

• In cooler climates, plant deciduous trees on the southern side to allow the sun to warm equipment in winter.

• In warmer climates, plant a mixture of deciduous and evergreen trees on the southern side

Minimum tree spacing

• Large trees: 25ft on center

• Medium trees: 15ft on center

• Small trees: 10ft on center

• Large with medium trees: 12ft on center

• Large with small trees: 10ft on center

• Medium with small trees: 10ft on center

Plant location rules

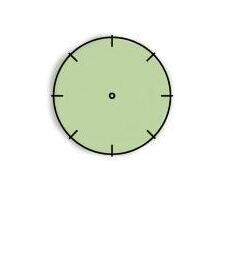

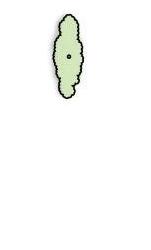

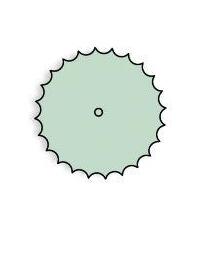

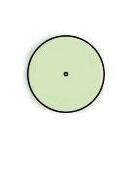

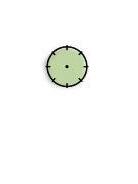

These rules are illustrated on the layouts opposite “Symbol” refers to the graphic representation of the trunks (left layout) and tree crowns (right layout).

• No symbol should overlap a like symbol. (i.e., a large tree should not overlap a large tree, regardless of whether one is deciduous and the other is evergreen)

• A large tree can overlap a medium tree, but the edge of the large tree symbol cannot overlap the medium 5ft buffer around the trunk.

• Large trees and medium trees can overlap all other symbols with a 5ft buffer around the trunk (i e , the edge of the small tree symbol should not touch the 5ft buffer)

• All other symbols should not overlap (i.e., a small tree should not overlap a shrub).

Naturalization phasing rules

Naturalization phase one:

• Space large shade trees a minimum of 30ft on center

Naturalization phase two:

• Space large shade trees a minimum of 30ft on center.

• Place small shade trees along 3ft use zone buffer equidistant from large shade trees along southern edge of use zone

Naturalization phase three:

• Space large shade trees a minimum of 25ft on center.

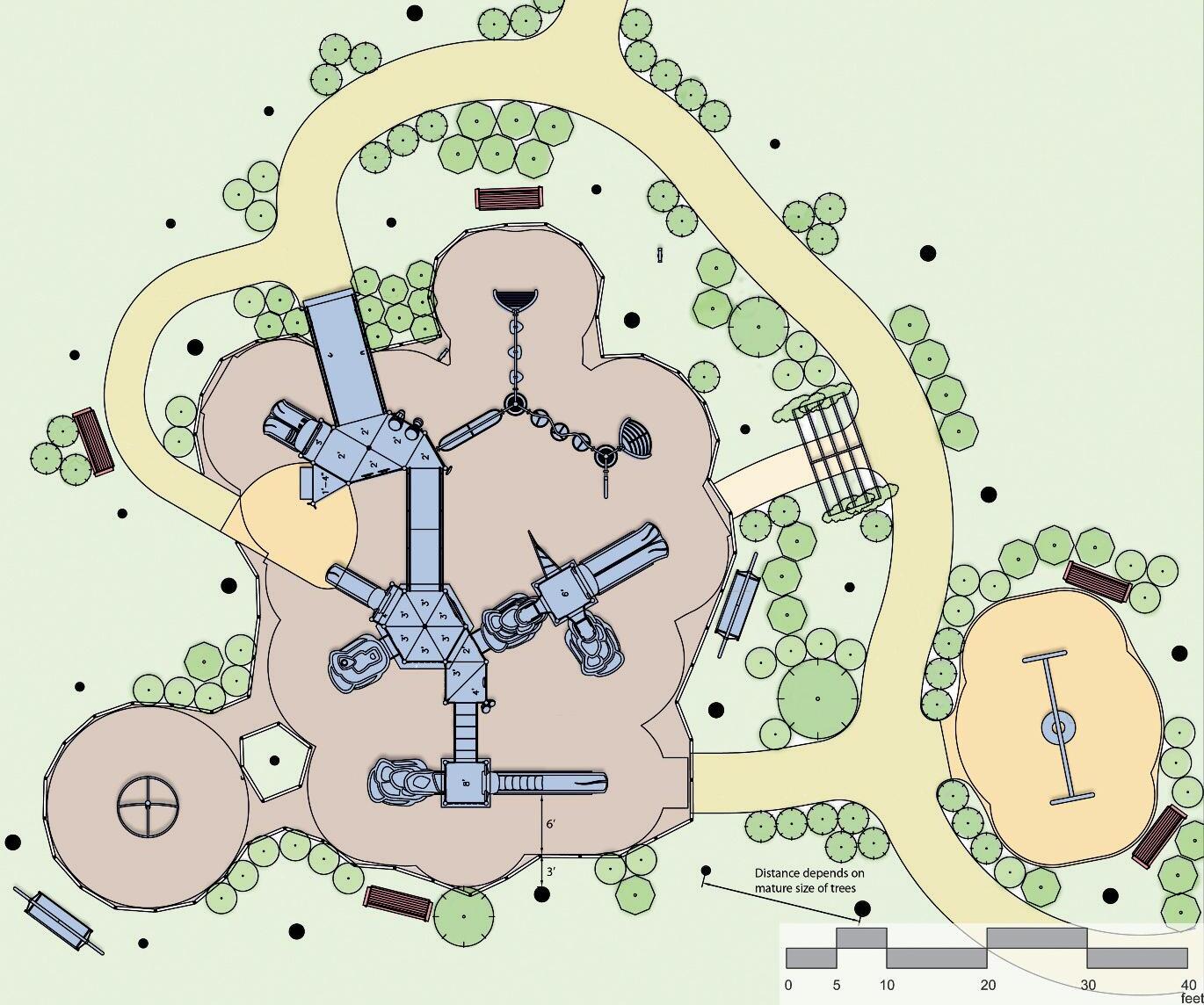

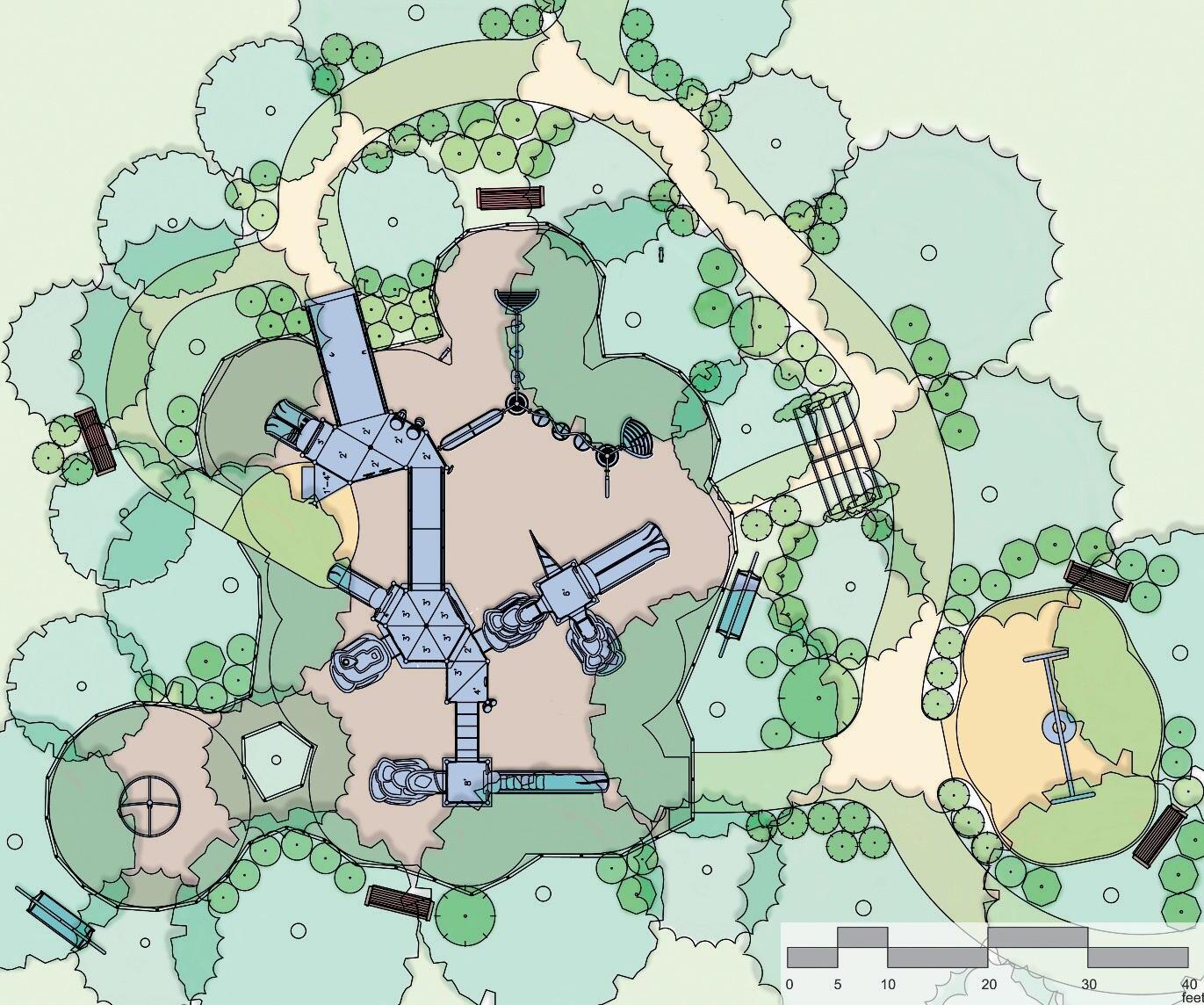

Application of planting pocket criteria and plant location rules: These layouts show how the planting pocket criteria and plant location rules can be applied to create a richly naturalized playground

• Place small shade trees along 3ft use zone buffer equidistant from large shade trees

The playground layouts above illustrate application of the planting pocket criteria in a moderately-sized playground. Broad planting pockets are defined by the location of the adjacent pathway connecting the playground to the rest of the park.

In the layout on the left, a small planting pocket is located between the main use zone and the stand-alone equipment (lower left). The tire swing zone (lower right) is defined by a line of shrubs. Benches are tucked into the planting pockets. The locations of tree trunks are shown, indicating the large number of trees possible when the planting pocket criteria are applied.

The layout on the right shows the same layout but with the tree canopies added to demonstrate the minimum tree spacing, plant location, and phasing rules.

The photograph shows how a planting pocket can take the form of a berm installed adjacent to an ADA access route onto equipment.

Single composite play structure and use zone phased naturalization: This set of layouts shows the phased naturalization of a moderately-sized playground with unified post and platform equipment and overhead components located adjacent to a park or school ground primary pathway system

The single equipment use zone is located far enough from the main pathway to create spaces for planting pockets. Short pathway spurs provide accessible connections to equipment and facilitate easy movement through the use zone Benches are included for social gathering

Phase One: Three large deciduous shade trees are located close to the southern edge of the equipment use zone and a fourth large evergreen tree is located NW of the equipment use zone to add year-round interest Two medium-sized deciduous trees increase the visual interest

Phase Two: Additional evergreen trees on the north side of the park benches offer shade and additional seasonal interest. Additional deciduous trees shade play settings and park benches south of the equipment use zone Shrubs add ground level visual interest and complexity

Phase Three: Substantial deciduous and evergreen shrub planting and large decorative grasses add ground level visual interest and complexity, creating places where children can explore and play hide-and-go-seek and chase games in and around the trees and pathway segments

Multiple play structures and use zone phased naturalization: This set of layouts shows the phased naturalization of a moderately-sized playground with a composite climbing structure and climbing net located adjacent to a park or school ground primary pathway system

The subdivided equipment use zones define a central planting pocket and social setting with park benches. Each subset of equipment occupies its own use zone, which increases spatial complexity and exploratory possibilities. Park benches offer social gathering settings. An arbor adds shade and visual interest to the main pathway and a sense of entry

Phase One: Five large deciduous shade trees and one medium-sized tree surround the climbing net structure and shade the central social setting and composite climbing equipment. A large evergreen tree north of the composite climbing equipment adds shade to the two park benches and seasonal interest

Phase Two: Additional deciduous and evergreen trees north of the composite climbing equipment provide additional shade and increase visual interest. Shrubs add ground level visual interest and complexity.

Phase Three: Substantial deciduous and evergreen shrub planting and large decorative grasses add ground level visual interest and complexity, creating places where children can explore and play hide-and-go-seek and chase games in and around the trees, central pocket planting, and pathway segments

Playground planting and its integration with manufactured equipment is the core topic addressed by this guidebook as the primary playground naturalization strategy. A broad range of possibilities are available for achieving naturalization. Plants in this publication are grouped into deciduous trees (large, medium, small), evergreen trees (large, medium, small), deciduous shrubs (large, medium, small), evergreen shrubs (large, medium, small), deciduous vines, evergreen vines, and groundcovers Flowering perennials add a compelling variety of colors, textures, and fragrances to the naturalization plant palette

Preserve, select, and integrate trees and other plants in the playground site

Preserve existing trees

• Use a qualified arborist to carefully examine existing trees for disease before a playground is installed, to ensure that existing trees are worth preserving If a tree is judged to be seriously diseased or near the end of its life, it may make sense to replace it with a new, carefully selected, large caliper specimen tree

• Locate playground equipment beyond the dripline of existing trees to avoid damage to tree roots, preferably on the north side to provide shade. Protect tree trunk flare area and limit disturbance of tree roots within the area under the tree canopy dripline

• Install a tree protection fence as required by local regulations, if appropriate

• Take advantage, where possible, of existing trees on a playground to add a sense of identity to the site At the same time, be sure to honor the manufacturer’s suggested use zones when incorporating trees into naturalized play areas

The two flowering cherry trees in this playground say, “welcome to spring,” as well as adding strong visual identity. During the summer months, the deciduous trees shade the seating under their crowns. Additional naturalization is offered by the vine-covered fence enclosing and securing the playground from the surrounding park.

Select child-friendly, high play value plants

Consider the following play and learning criteria when selecting plants for children’s play areas:

• Contrasting leaf textures for sensory stimulation: evergreen with deciduous, shiny with rough, serrated with smooth edges, thin with thick

• Variety of sizes and shapes of plants.

• Seasonal change for novelty and interest: evergreen contrasted with deciduous, seasonal color, early leaves, late flowers, etc

• Color variety of trees, shrubs, vines, ground covers, and flowering perennials

• Fragrance for sensory stimulation and exploration.

• Natural elements like berries and cones that can be used for craft activities.

• Auditory stimulation Some plants, especially in the fall, produce interesting sounds when the wind blows through their dry leaves Plants such as clumping bamboo and pine trees produce sounds year-round.

Consider plants as design elements in naturalized playground design to perform the following functions:

Enclosure. The size, shape, and enclosure of play spaces can be enhanced by being wholly or partially defined with plants

Shade. Deciduous trees offer summer shade and let winter warmth through when leafless. Evergreen trees and shrubs add green interest during the dormant season of deciduous trees

Identity. Distinctive plantings provide visual identity and a sense of place to children’s environments.

Movement. Using plants in relation to topography can enhance the experience of movement through play areas Grasses in particular add an element of movement

The richly planted border enclosing this playground is protected by an elegant post and chain assembly that is hardly noticeable but effective. Large deciduous trees provide a shady ambience to the play equipment.

A generous planting opportunity is provided by the sloping side of a berm which provides color, texture, and fragrance to the play space for a multisensory experience.

Play props. Vegetation supplies a wide variety of play resources or loose parts that children can harvest for themselves and/or their friends

Sensory stimulation. Plants can be selected to provide a full range of sensory experiences.

Accessibility/inclusion. Plant settings can create intimate, touchable spaces that are accessible to users of all abilities and therefore offer particular advantages as inclusive settings.

Landmarks. Objects such as specimen trees offer visual identity and function as landmarks.

Seasonal change and novelty. Plants mark the passing of seasons and introduce children to a sense of time and natural processes as plants grow and change

Wildlife enhancement. Plants provide animal habitats so that children can interact with wildlife in play areas

Compile site specific plant lists

• Use the NatureGrounds on-line, searchable plant selection database at www.NatureGrounds.org to select playground plants.

• The plant list should include the genus, species, size, quantity, quality, and variety of plants to be used for ease of identification by the supplier

• All plants should comply with applicable requirements of the American Standard for Nursery Stock (ANSI Z60 1), 2004 (see Resources)

Select healthy, appropriate plants

• Choose drought-tolerant, deer-resistant plants that are hardy in the playground site hardiness zone for your region. Refer to the USDA Hardiness Map (page 31).

• Choose native species if possible or species that are adapted to the region and have an established reputation for hardiness.

• Avoid invasive species introduced from other geographic areas, to prevent aggressive competition with native species

• Choose plants with healthy, full, well-shaped root systems

• Choose fully branched plants with evidence of vigorous growth and dense foliage.

The NatureGrounds on-line, searchable plant selection database

The on-line, searchable plant selection database (at www.NatureGrounds.org) includes plants that are “hardy natives,” which are likely to thrive in specified regions, and exhibit appropriate naturalization characteristics for playgrounds located in parks and school grounds.

A variety of database variables allows users to customize their playground planting searches based on plant type preferences, plant characteristics, culture characteristics, play value, and regional distribution

To compile the database, two primary print references were used: Plants for Play by Robin Moore (1993) and The Manual of Woody Landscape Plants by Michael Dirr (1998). Authoritative, web-based plant data sources were also used as they are constantly updated and are regarded as the best source of current information Further plant data references are listed under Resources

A screenshot of the on-line, searchable plant selection database is shown at right with variables contained in the pulldown menus listed below.

Plant database variables

Plant type

Plants are listed by botan cal name (linked to the USDA Plant Database) and common name. They are organ zed alphabet cally by botan cal name by type of plant

Trees (dec duous/evergreen) large, medium, small

Shrubs (deciduous/evergreen), large, medium, small

V nes (deciduous/evergreen)

Grasses

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Hardiness Zone Map (above) defines areas in which specific categories of plant life are capable of growing, as defined by climatic conditions, including withstanding zone minimum temperatures. The map shows the eleven hardiness zones, where Zone 1 is the area with harshest conditions for plant growth. The six regions used in the NatureGrounds on-line, searchable plant selection database are also identified.

Plant characteristics Native Tree Shape Vine Physical Attachment Leaf Texture Shade Quality Bark Texture

Exfoliating Bark

Planting success: Prepare and care for plants

Ensure proper soil preparation

• Soil preparation is the most important factor ensuring planting success

• Conduct a soil test using the services of the local Cooperative Extension Service to assess suitability for healthy plant growth. Results will recommend nutrients needed and correction or removal of any problem salts, minerals, or heavy metals

• Soil properties include texture, structure, organic activity, profile, compaction, water movement, and nutrient holding capacity. Good quality planting soil contains 70–80% solids, 20–30% void space for water and air, and approximately 2% of organic matter

• Maintain soil texture by protecting from compaction during construction Minimize areas for parking and storage, and use tracked grading machines.

• Stockpile native topsoil at 4ft to 6ft deep to avoid damaging soil structure and soil biology

• Reuse native topsoil formed under natural conditions Otherwise, use imported or manufactured topsoil. Topsoil should have a pH value from 5.5 to 7.0 and contain approximately 2% organic material

• Use clean soil without debris such as roots, sod, stones, clay or sand lumps, concrete pieces, cement, plaster, building debris, and other materials that can be harmful to plants.

• Loosen subgrade to at least 8–18” deep to encourage drainage and root growth.

• Spread topsoil to a minimum 6” depth to meet finished grade and rake to a smooth surface Add amendments and blend thoroughly.

• Amendments include inorganic types such as lime, sulfur, iron sulfate, perlite, gypsum, and sand; organic types such as compost, peat, bark, and manure; and fertilizers such as bone meal, superphosphate, and slow-release fertilizer.

• After planting, top dress with organic mulch, such as triple-shredded hardwood mulch, which should be well-composted, weed-free organic matter spread 2” deep

Accommodate root space

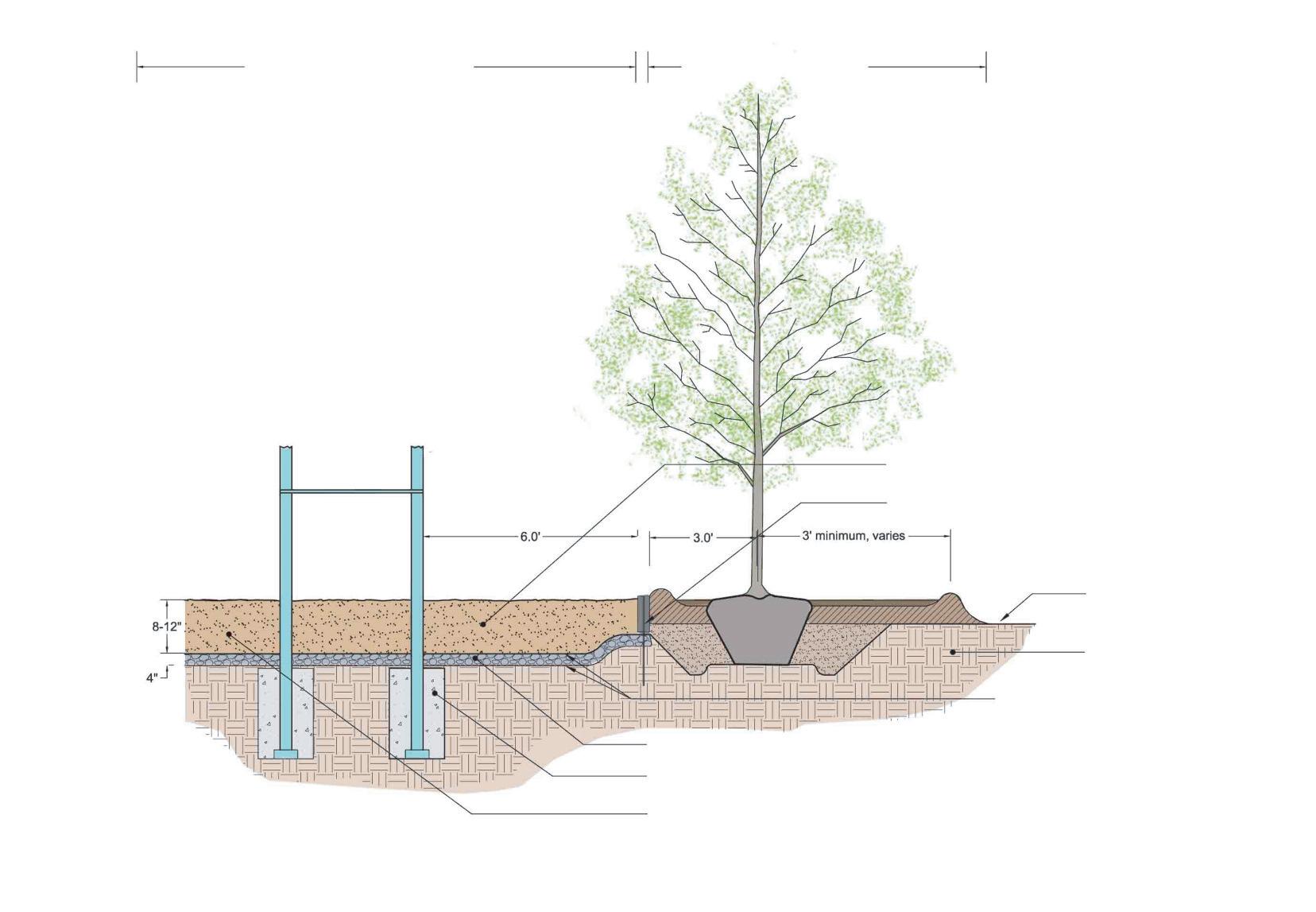

• Dig planting pit about three times the width of the root diameter and deep enough to accommodate root ball but no deeper

• Raise bottom of pit to support root ball and to allow the top of the root ball to extend above the finished grade elevation Root ball should sit on compacted base soil to prevent settling Depending on the method used to dig the pit, ensure that the sides are scarified after pit is dug. Where possible, an excavator should be used to break up sides of tree pit as an auger may not

• Consider where roots may eventually grow and protect those areas from compaction Where possible, locate circulation and other potential disturbance away from future root zones.

• Plan for future root growth Ideally, a 5-ft radius area is necessary to support healthy growth of large canopy trees; however, this will not be possible for trees planted adjacent to (3ft away from) equipment use zones.

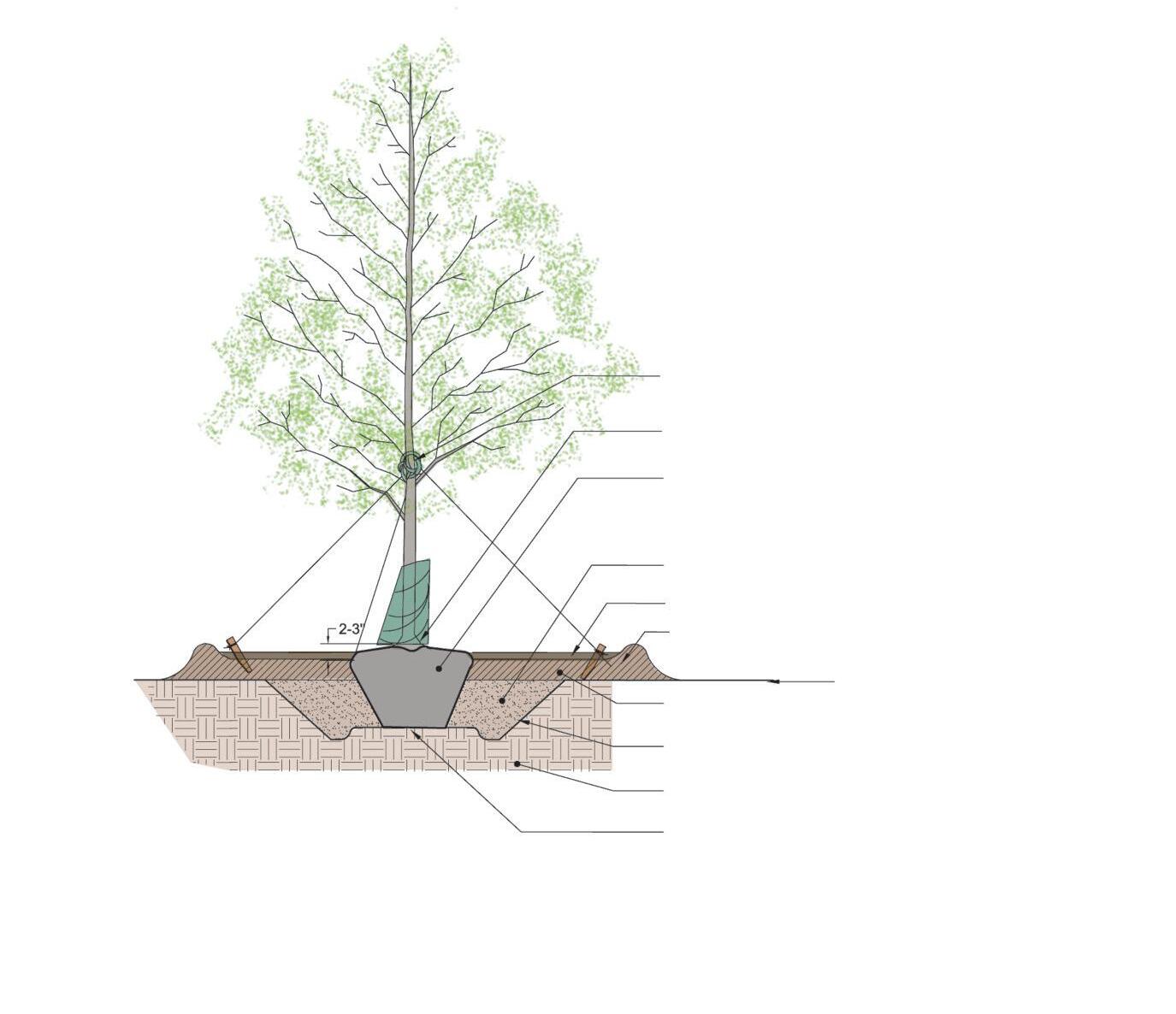

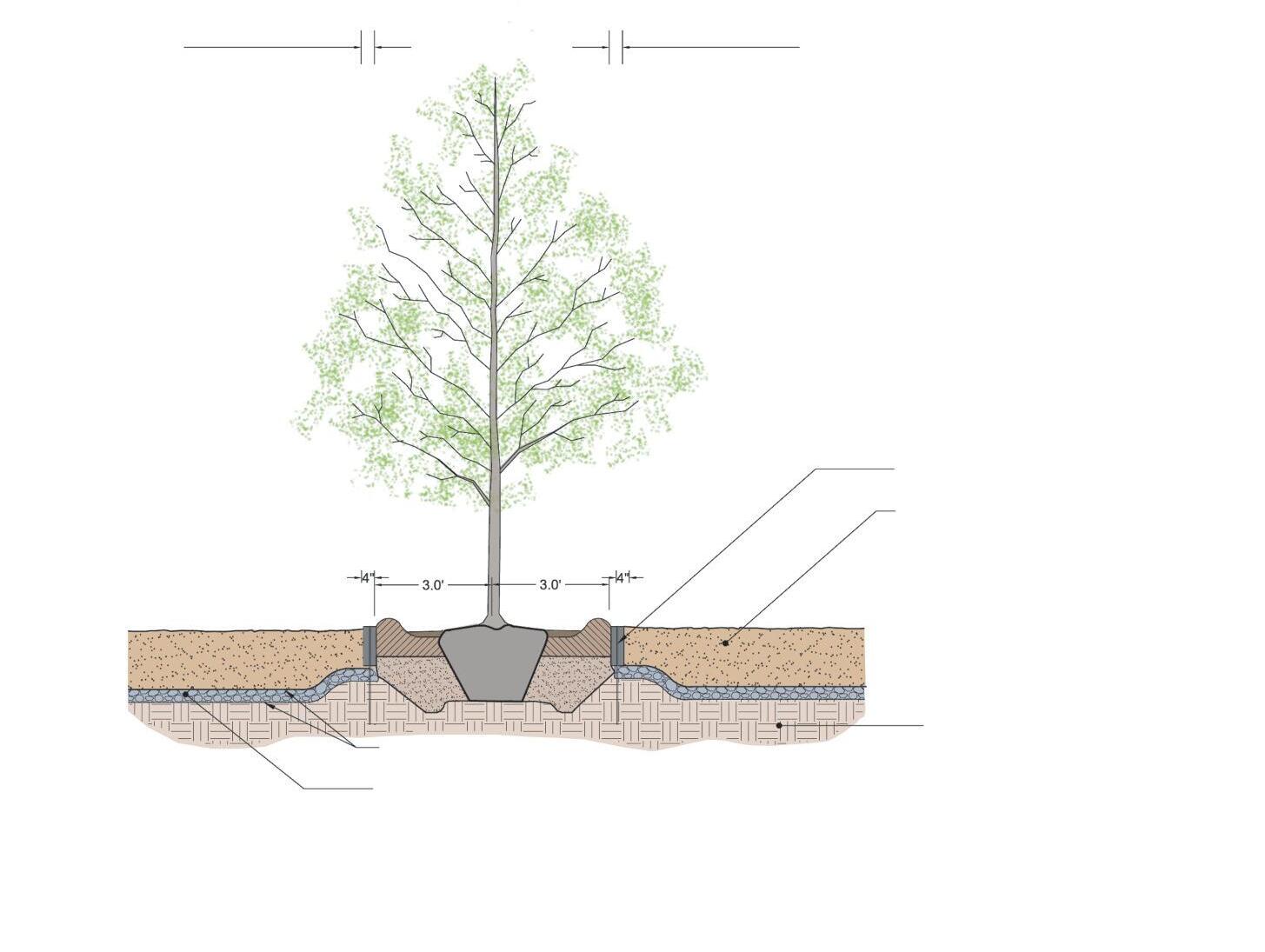

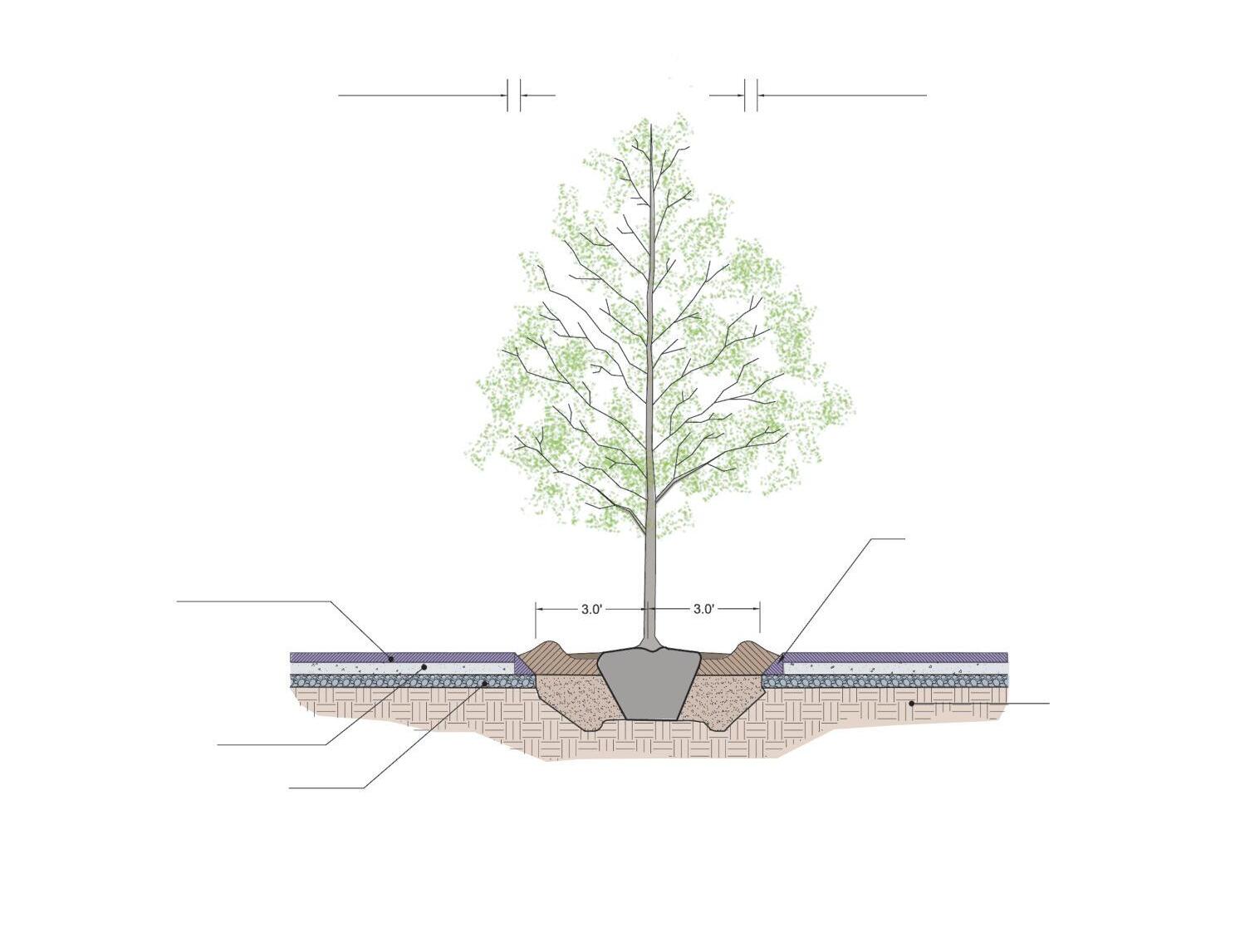

Stand-alone tree: Ball and burlap 1 1⁄2” to 2” caliper tree. Cross-section detail. See tree planting steps sidebar on page 33.

• Check that tree has strong central leader.

• Ensure trunk is plumb (upright).

• Build watering saucer around tree pit.

• Install irrigation bag to water tree.

• Ensure that trunk taper/root flare and basal roots are not covered.

• Remove burlap from around trunk and cut off wire basket and string.

• Set root ball crown 2”–3” above finished grade.

• Slope sides of pit toward center at a 45-degree angle and scarify sides.

• Do not prune or thin canopy unless directed by landscape professional.

• Protect branches from damage.

• Remove trunk guard after planting.

A–The tree pit has been dug with a backhoe and the tree location is being re-marked.

B–The depth of the planting pit is being checked using a spade across the grade and a tape measure. C–The 1” caliper tree root ball is being maneuvered into place suspended from a backhoe.

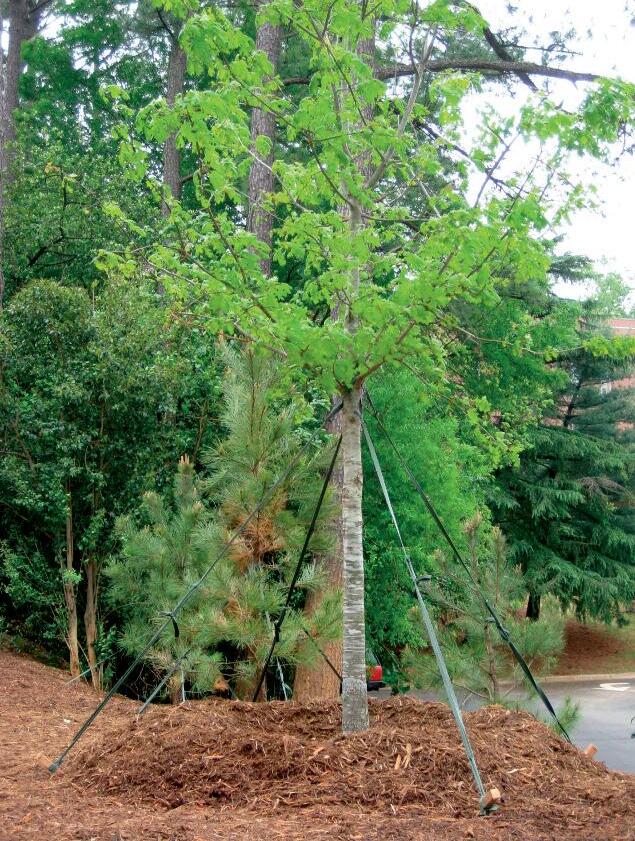

D–The root ball level and trunk verticality have been verified and the tree planting team is backfilling loose soil around the root ball. E–The burlap root ball bag top section is being cut off and removed. F–The tree has been planted at the correct level and the saucer edge is being tamped to ensure that it holds water. G–This planted tree has been secured with four staked guylines tied to the tree trunk with arborist’s knots.

• Install a 3-to-8-ft diameter area of mulch around the base of trees, depending on size. Avoid planting turf in such areas

Ensure effective drainage

• Effective surface drainage is essential for the overall functionality of the playground site

• Well-drained soil provides plant roots with essential oxygen and water. Stormwater should move steadily toward the site drainage system to avoid plants in standing water

• Alternatively, if rain gardens are installed, choose rain garden plants that can withstand variable wet and dry soils for extended periods.

• Compaction will inhibit drainage for both topsoil and subsoil.

• Create a saucer around plants to hold water (see cross-section illustrations)

• Water thoroughly immediately after planting (several gallons per tree or shrub, depending on size).

• Plants take 2 to 3 years to become established and need plenty of watering especially during hot, dry summer months

• The issue of irrigation should not be avoided for newly installed landscapes, particularly for the initial 2–3 year period while the new landscape becomes established. Healthy lawns require summer irrigation in most regions

• A variety of irrigation approaches, systems, and price points are available for playground naturalization.

• Regardless of irrigation system, hose bibs should be installed at regular intervals (every 50–60 ft if possible) along primary pathways so 25-ft hoses can be used Long hoses are difficult to manage

• Quick couplers provide the easiest access for hose irrigation. Otherwise, traditional spigots or hydrants provide watering sources, particularly during the two-to-three-year establishment period

• Irrigation demand can be minimized by using native, drought-tolerant species.

• Planting success can be maximized by installation during the dormant season when irrigation demand is lowest

• Use slow release, 20-gallon irrigation bags (also known by the brand name Treegator™) as a recommended irrigation method for trees 1” to 4” in diameter, especially during critical summer periods after planting

• Planting beds and lawns may require sprinkler irrigation systems that should be designed by an irrigation specialist

Offer plant protection

• All plants need protection, especially during the first two to three years post installation, if they are to thrive and grow vigorously.

• Use low-to-medium-height barriers such as hoops, low railings or raised beds to provide minimum protection to planting beds to inhibit children running through them

• Use playground equipment and/or site furnishings as boundaries to help protect plants. Elongated elements such as music stations can also be located along pathways and used to protect planting behind the element

• Use staking as an effective method of supporting healthy tree growth during the post-planting phase (2 to 3 years)

Naturalization projects can be created by either new construction or by retrofitting existing playgrounds. In either case, the foregoing principles provide a road map for success.

Retrofitting of playgrounds can vary in project scope A retrofit may entail replacing old play equipment or site furnishings and upgrading safety surfaces, or it may focus mainly on naturalization of an existing play equipment installation It may also involve retrofitting manufactured components and adding natural ones for an ideal naturalized play area.

Naturalizing existing play environments can be a meaningful way of sustaining current resources, engaging community volunteers, activating new community partnerships, and increasing the overall play value of the site for the community

New construction and retrofit projects can be implemented at different levels of investment and/or in phases as available resources dictate.

Successful implementation of naturalized playground projects involves a step-by-step process, which is usually driven by a community-appointed design committee or task force that offers multidisciplinary expertise for planning, designing, advocating, executing, sustaining, and funding the project

Appoint a playground or retrofit development taskforce for playground design.

For both parks and schools, stakeholders may include local chapters of national environmental organizations and/or professional design organizations

Appoint additional representatives from health promotion organizations, neighborhood associations, “friends of park” groups, arts organizations, disability groups, garden clubs, etc The potential list depends on the characteristics, history, and interests of the local community.

For parks, work with the parks and recreation staff and citizens board to include administrators, parks board citizen members, neighborhood organizations, and parks promotion/friends organizations

For schools, work with the PTO/PTA and other interested parties Include administrators, teachers, students, and parents.

Develop the playground design program. For parks, assess programmatic needs and potential of the proposed naturalized play area to support recreational and educational programming after school, on weekends, and during the summer Assess the potential for family and community activities such as birthday parties and family celebrations, cultural festivals, seasonal events, and arts performances

This playground site was large enough to accommodate a wide range of universally designed play settings and equipment areas, including a water spray area (blue circle, bottom right), a large scale acoustic play setting on the central hill, an embankment slide taking advantage of the higher elevation (left of hill), poured-in-place play “hillocks” behind the slide, and a large acoustic play gong in the foreground. Existing trees have been carefully preserved and additional trees added to increase shade and visual interest. A local artist contributed the colorful mosaic totems as wayfinding elements and aesthetic enhancements. Surrounding “field” areas remain available for informal games and ball play.

For schools, assess potential classroom curricular programs as well as after school and summer programming

For both parks and schools, seek sources of potential program funding and if necessary modify the design to accommodate such prospects.

Create a playground master plan. For both parks and schools, the primary task is to develop a master plan and plan of action to implement the project, including possible phases If necessary, consult with a landscape architect/designer

Define a budget. A crucial component of successful implementation is a cost effective budget The following steps need consideration:

• Define the scope to complete the project in phases, if required because of budget limitations.

• Create a project budget and solicit funding partners.

A playground development taskforce works on a master plan to integrate the living landscape with selected manufactured equipment to create an innovative play environment that offers children, families, and communities the many benefits of playing in nature.

Children contribute design ideas for the master plan, helping adults see a play environment from the child’s perspective and providing children a sense of ownership in the process.

• Consider price points, phases, and overtime plan.

• Create a contingency plan.

• Seek assistance from www NatureGrounds org and/or NatureGrounds field representatives to guide discussion and decisions about project priorities and cost tradeoffs

Develop the playground layout and define the use areas. Propose locations of equipment items, planting, and site features in relation to each other. If necessary, consult with a landscape architect/designer or landscape contractor For new and retrofit projects, connect with a NatureGrounds field representative to analyze the current layout, define opportunities for integrating plants, and create CAD designs

Select play equipment. For new construction, decide which equipment will best fit user needs within the available budget For retrofit projects, decide which components will be removed and/or replaced and what new equipment is to be installed within the available budget. Verify where new safety surface must be replaced or replenished and decide where new curbs or edging need to be installed Consider opportunities for naturalization around, beside, and/or under play equipment.