playful PLACEMAKING

Community Engagement Strategies Using Social Science in the Design Process

Empowering communities, through play and the use of social sciences, to support architects and designers with new community perspectives in order to design successful public spaces where funding optimally aligns.

playful PLACEMAKING

Community Engagement Strategies Using Social Science in the Design Process

Developed in Partnership:

©2022 PlayCore Wisconsin, Inc.

All rights reserved.

The purpose of Playful Placemaking is to provide an educational overview and is not to be considered as an all-inclusive resource. Please refer to manufacturer specifications and safety warnings for all equipment. While our intent is to provide a general resource to encourage communities to engage in public participation when designing public spaces, the authors, partners, program directors, and contributors disclaim any liability based on information contained in this publication. Site managers are responsible to inspect, maintain, repair, and manage site-specific elements. PlayCore and its brands provide these comments as a public service in the interest of building healthier communities through play and recreation, while advising of the restricted context in which it is shared.

Table of Contents

2 Partner Bio & Forward

5 History of Placemaking and Inherent Limitations in Engagement

8 Utilizing Social Science to Engage Communities Through Play

14 Evidence for Playful Placemaking

22 Strategies for Hosting Playful Placemaking Events

} Community Conversations

} Site Analysis Tours

} Team Building Games

} Trying It On

31 Measuring Outcomes and Planning for Success

} Prioritizing

} Funding

34 Case Studies

42 Where to Begin with Playful Placemaking

44 Resources

1

Joy Kuebler

PRESIDENT, JOY KUEBLER LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT (JKLA), PC AND PLAYCE STUDIO, LTD

A graduate from Cornell University’s Landscape Architecture program, Joy is a licensed landscape architect and entrepreneur. Her professional practice includes a variety of public landscapes including community parks, streetscapes, waterfronts, college campuses, elementary schools, hospitals, and multi-modal centers. Throughout her career, she has been drawn to designing for children and play with over two decades of experience in environment-based curriculum, school yards, and community nature play, as well as a founding role in Pop Up Park Buffalo, a non-profit organization that brought adventure-style free play to vacant lots throughout Buffalo, NY for more than 5 years.

Today, her work includes the development and training of a playbased social science methodology, PLAYCE, that invites those rooted in designing the public realm to become facilitators, co-discoverers, and to become those who empower communities and their agents to be more than they thought possible, all through the common language of play.

2

Forward

In the 1990s, before arriving at Cornell, I studied engineering and interior design, graduating with an Associates of Applied Science in 1994. Landscape architecture allowed me to play in both large and small spaces, in ways that let me leverage both the “tech” and “arts and people” side of my brain, all while positively impacting communities.

It was during my third year of landscape architecture school that I proposed a large “playful experience” to bring respite, joy, and exploration to all who “happened upon it” in the center of Cornell’s campus. It was to be my first of many play landscapes.

That time also marked a shift in education and practice philosophy from “architect as expert” to one that encouraged designers to communicate with the public; the users of the landscapes, owners, and stakeholders to help determine a project’s programmatic direction. After graduation, I entered the professional world that was not yet practicing in ways that fostered community listening or participation. It was here that I first saw the disconnect, as well as an opportunity.

I have been an active voice for considering problems from new perspectives and my considerations for utilizing the power of play to support design-based community engagement began to coalesce after I first met Dr. Stuart Brown and Tom Norquist of the National Institute for Play. From Dr. Stuart Brown’s research, we know that play fosters imagination, leads to creative solutions, enhances learning about risk that is tolerable and is exploration of the possible - this is what drives my work. PLAYCE is a methodology for shaping public spaces through playful interactions, and is an opportunity for communities to see possibilities for themselves.

Using social science to engage communities, I have seen communities move from immovable attitudes to a place of forgiveness and openness to new possibilities. Through the PLAYCE strategies, we use play to offer a podium that works for every voice. Through the power of play, communities can reveal what is in their hearts and step into that power of helping realize their needs alongside their design team.

My vision for PLAYCE is to change the view of designing for health, safety, and welfare from preventing injury and mitigating hazard to supporting people in having an engaged and fulfilling life right in their own community. I want to change design as a transaction to design manifested from the hearts of the community. The more facilitators and designers that can be brought around to this way of thinking and practicing the more hearts are invested, the more hearts are engaged, the more hearts are making change.

So just lead with Heart!

Joy Kuebler

Joy Kuebler

3

4

History of Placemaking and Inherent Limitations in Engagement

IN VERY BROAD TERMS, the turn of the 19th Century saw the emergence of urban planners and designers of the built environment as new professions. The industrial revolution created wholly new landscapes and a need to rethink how urbanizing western cities and communities should be organized. Real people lived real lives in and amongst factories, green grocers, tenement apartments, livery stables, train yards, school houses, and slaughterhouses. New industries literally grew overnight, leading to rapid urbanization, but also pollution and often inferior infrastructure. All of this was made worse by disease, crime, and political discontent. The need for social and spatial reform, to ensure community health through the separation of industry and factories from people’s homes and schools, led to the emergence of visionaries of the urban form; people such as Ebenezer Howard, Frederick Law Olmsted, Baron Von Haussmann, and Daniel Burnham advocated for neighborhoods with doctors, shops, and schools as well as safer factory environments, and public parks offering clean air, access to nature and socialization, and recreation for the entire community1

Their revolutionary ideals transformed the way cities were developed, literally saving millions of lives, transforming both urban and

rural landscapes, creating access to clean water and nature while supporting continued industrialization. This grew the professional field of design and the management of urban environments to one of “expert,” and the bureaucratic role of land use, zoning codes, building codes, and designers as the caretaker of health, safety, and welfare was born.

These useful solutions to ever-growing problems were not without their own challenges, leading to greater issues in the following decades. Municipalities treated the modern visionaries of city-making as authorities in the field, producing and reproducing their ideals in diverse settings and spaces without considering the unique sets of topography, landform, histories, or cultures that would remain and impact the overlay of the “ideal.” In the United States in particular, the wide separations of uses such as industrial areas and residential neighborhoods in addition to Ebenezer Howard’s call that every resident should require access to small private greenspaces and single-family homes led to the development of low-density suburbs1. These suburban areas limited social activity and cultural interaction and favored expensive personal transportation options over consolidated and less expensive public transportation. This in turn brought only people with the means to afford private car ownership,

5

and neighborhood elitism based on personal wealth, eventually leading to discriminatory housing practices. Daniel Burnham’s regional transportation ideas were abused by Robert Moses as he divided urban neighborhoods with highway infrastructure making room for more and more cars to enter and exit quickly from the suburbs2. Le Corbusier’s demand for social housing was misappropriated into unmaintained public housing infrastructure such as Cabrini Green and Pruitt Igoe-which publicly failed as they filled with the most vulnerable and marginalized people, began to be symbols of urban blight, and were subsequently demolished.

These challenges led to a new level of awareness and an emergence of grassroots planning and architecture in the 1960s. As the urban centers in the United States were being dominated by Urban Renewal planning, a process that included the razing of historic downtowns, areas perceived as blighted and/or economically disinvested were considered a “blank canvas” for opportunities with perceived higher economic returns. Rural farmland was also being taken in favor of sprawling, low density development. It was here where revolutionaries such as journalist Jane Jacobs and sociologist William Whyte noticed the inequities and detached urban form and called for different and new approaches to the profession.

Jacobs revered the inner city neighborhood which she saw built a sense of community through social interaction and neighbors. In her book, she noted that the city is “owned” by the residents who cocreate it, and how people actually lived in cities was more important than how visionaries thought they should live3. Similarly, Whyte, while working for the New York City Planning Commission, literally sat and watched people interacting in and with spaces. These observational studies, which spanned

“The city is ‘owned’ by the residents who co-create it, and how people actually lived in cities was more important than how visionaries thought they should live.” — Jane Jacobs

years, documented how very different actual human behavior was from conventional expertise in the areas of engineering and public safety. He is best known for his observation that our human social life in public spaces contributes not only to the quality of life of individuals, but the quality of life for society as a whole. These studies, writings, and ideals transformed the approach to planning and architecture throughout the design professions. Jacobs and Whyte’s insights favored a “bottom up'' approach to creating communities by way of understanding environments through inquiry and a person’s use of space. This consideration for human behavior reshaped the profession on a grand scale and introduced conversations on community engagement.

As a result, we know that successful placemaking is important for a variety of reasons. By creating places where people can participate in the ways they prefer, they are more likely to stay, return, and spread the word. A great public space creates a feeling of belonging, camaraderie, pleasure, and joy. This doesn’t happen without careful listening. In the decades following Jacobs’ and Whyte’s work, the design world made great strides in moving past “expert” and asked the community to be involved in the design and planning process.

6

The difference between space and place is like the difference between ‘house’ and ‘home’. Many tangible and intangible elements combine to create a memorable experience. Good placemaking demands that we consider the end-users by inviting them into the conversation as an important part of the design process. It requires decision-makers to have genuine regard for long-term success and social, cultural, environmental, and economic sustainability. As users and advocates in placemaking efforts, we relish the opportunity to empower communities; engage in meaningful dialogue, facilitate opportunities to listen, and empower communities and design professionals to see possibility all around them.

The more recent decades have seen some challenges from both communities and design professionals due to inherent barriers, including:

} The process and practice often intimidate both professionals and participants.

} ●There is a strong disconnect between the literature and research around the value of engagement, versus its practice and implementation.

} There can be a “Check the Box” attitude, which can reinforce the lack of trust between groups.

} There is often a perception of an imbalance in power, where one side “knows better” than the other.

} There can also be a sense of forced collaboration which can lead to challenging experiences and unsuccessful outcomes.

} Interest limitations and lack of bandwidth on the part of both professionals and communities, often leads to empty meeting rooms.

} Communities can be highly divided with contesting viewpoints, causing challenges for meaningful engagement.

} There is a prevalence of ‘hard to reach groups’ such as young people, older people, minority groups or socially excluded groups, giving the impression that reaching people is just too hard.

} There is no common language between designers, municipal leaders, and community members.

7

Utilizing Social Science to Engage Communities Through Play

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT SESSIONS traditionally have taken the form of public meetings, design workshops, or charrettes with children and adults or even open community forums. These sessions, if mindfully developed and presented, can bring energy and productivity and create a rewarding experience for those involved. If not, they can be very limited in their capacity to bring forth the authenticity needed in making a successful project come to life. We’d like to introduce the use of social science and play to create completely new engagement opportunities, or to strengthen community engagement techniques you may already use.

DEFINITIONS OF PLAY:

“Play is voluntary, and takes one out of the sense of time, has improvisational potential, and while it may appear to have no purpose, is engagingly Fun!”

- Dr. Stuart Brown, National Institute for Play

“In a world continuously presenting unique challenges and ambiguity, play prepares these bears (humans) for an evolving planet.”

- Bob Fagen, Ronin Institute researcher

“A free activity, standing apart from ordinary life as being “not serious” but at the same time absorbing. Not connected to any material interest or profit.”

- Johan Huizinga, Dutch cultural historian

“A ‘give and take’ experience, the playing back and forth with an idea, without any expectation of finding a solution, but engaged in the inquiry.“

- Joy Kuebler, President, Joy Kuebler Landscape Architect and PLAYCE Studio, Ltd

8

A Facebook survey asked the question: “Taking the inference of children out of the responses, how would you define Play?”

} ●Play means safe exploration of physical and/or social interactions.

} Play can be a guiding spiritual framework, a lens of how we view the world, an approach to living.

} Play is doing something for any reason, or no reason, for pleasure or to learn.

} Play has to do with imagination, innovation and presence.

} Play is a willingness to try things.

There are some interesting similarities to notice in these definitions:

} ●There is a sense of safety.

} There is a willingness to explore.

} There is an acceptance of fun being for fun’s sake.

} Play includes activities that are without a goal but always valuable.

Dr. Stuart Brown quotes the work of noted animal play scholar, John Byers when he shares, “Byers speculates that during play, the brain is making sense of itself through simulation and testing. Play activity is actually helping to sculpt the brain.5”

For Joy Kuebler, as a landscape architect, the big “ah-ha moment” came in the following statement:

“In play we can imagine and experience situations we have never encountered before and learn from them. We can create possibilities that have never existed but may in the future. We make new cognitive connections that find their way into our everyday lives. We can learn lessons and skills without being directly at risk.”

This5 captured how Play could be the common language supporting community engagement for the design of the built environment. Traditional community engagement does not create an environment where individuals or a community can imagine a future, play and explore in that imagined future, and then share what they created in their imagination.

9

BUT WHY PLAY?

PLAY IS INSTINCTIVE IN HUMANS AND ANIMALS AND SUPPRESSING THE INSTINCT TO PLAY IS ACTUALLY HARMFUL. Without play, children and adults are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, impulsivity, and sedentarism. Our creativity, ingenuity, and willingness to work cooperatively are also limited when play is not present in our lives. However, if we are safe, otherwise healthy, and well-fed, play can actually bubble up spontaneously in its wide variety and highly individual patterns, from infancy to old age. Play strengthens the mind and body, straightening the path towards social competency, emotional stability, physical capacity, and success. All people play, and lack of play limits how we interact with the world around us and our capacity to shape it. There is increasing mastery that is part of early play and that helps humans cope with an ever-changing world (economic, climate, etc.).6

All people play, and lack of play limits how we interact with the world around us and our capacity to shape it.

For many years, charrette-style engagement invited participants to pick up a pencil and draw their ideas. The outcome often included a large group of people who felt intimidated by the request to draw, so rarely would. While the designers see pencils as a tool to “scribble and play around”, often the general public sees themselves as not skilled at making marks on paper and therefore do not. Designers are trained to see and understand a wide range of drawing types, and these drawings are included in

10

engagement presentations even when the public has very little experience with or understanding of them. Computer-generated illustrations can create the impression that a design is further along than it is in reality, making it hard for the community to object or feel that their input will have any impact on the outcome. Information sessions also often rely on digital presentations and open microphone opportunities rather than real conversations.

When we move from a language of drawing and presentation to a language of play, the community CAN imagine situations they have never encountered before and share what they see as possible, as well as envision obstacles to what is possible. They can see connections that find their way into their everyday lives and most importantly, they can try on possibility without risk. Avoiding risk and the fear of failure is what is often heard from community members in opposition to a project, even when the project is intended to support improvements to

their basic infrastructures. For these groups, play could create a major breakthrough in how they see themselves, as well as how they imagine the project would impact their lives.

Play research shows that every human plays, regardless of age, ability, culture, or language. It is likely our earliest language, both as individuals and as a species. Play is a very interesting beginning place for community engagement, because when one is playing, one is involved as a collaborative problem solver.

There is also something profoundly important that is created in play. As noted in the barriers to present day engagement, trust is the fundamental requirement for any relationship to be successful7 So, why would the world of design be any different? Owners or municipalities often say, “We don’t want to spend a lot of time on engagement, they have no idea what is needed or what we want to do.” or

11

“everything they want to do is unrealistic or expensive.” On the flip side, communities say, “Why should I believe you, you ask my opinion all the time and you never listen.” or “You just do what you want to anyway. We are only here to check the box.” There is absolutely NO TRUST in those experiences. How could engaging there ever be successful?

However, through play we find common language, common interest, and common concern. We can come from being related. We can trust. Additionally, in play, we create empathy. Empathy is REQUIRED for communities and individuals as they explore what possibilities are available to empower ALL through the design of WHATEVER it is that is being considered. Empathy allows a group to see beyond their individual self and come to a consensus, even if it is not unanimous.

In recent decades there has been an explosion of information emerging from social, psychological, behavioral, and biological sciences all citing the benefits of play, and we believe the design of our public realm can benefit as well.

Empathy allows a group to see beyond their individual self and come to a consensus, even if it is not unanimous.

Playful placemaking includes four primary types of play and engagement models to empower communities and innovate the built environment:

Community Conversations

} Go to where people already are

} ●Ask compelling questions

} Include engaging activities

} Make it fun for all ages

Site Analysis Tours

} ●People power: walking, biking, boating

} Invite ALL stakeholders to walk together

} Play along the way; discover possibilities and barriers together

Team Building Games

} Key tools in building trust, empathy and collaboration

} Specifically crafted for project needs

} Value in a variety of both physical and thinking games

Trying It On

} Test designs in real time

} ●Low cost, quick, and temporary

} Fun and festive atmosphere

} Create programming to showcase the potential impact of the project

12

13

Evidence for Playful Placemaking

OBSERVATIONALLY, THERE IS MUCH TO SHARE about the alignments of how all people, young and old, benefit from play and how playful placemaking methodologies leverage those benefits to support community empowerment, whether the design is for a community center and playground, a housing subdivision, streetscape, a nature preserve, or an urban schoolyard. As adult human demands increase, we often lose sight of how much of the world is enhanced by keeping much of it as a playground instead of a proving ground or battle ground.6 The traditional public meeting forum is too often seen as a “proving ground” or “battle ground”, between the design team, community members, and project leadership, whether it be private or municipally led. This knowledge can be seen as a “call for something better.” Playful Placemaking can be that something better.

14

THE HEART OF PLAYFUL PLACEMAKING

Trust — Trust is a crucial element of human need, and the heart of playful placemaking, which supports the development of trust between community and design team as well as the community and project owner or leader.

Empathy — We note this as a primary outcome of playful placemaking. Cultivating empathy through play and activities, building the capacity to agree, even if one is not benefiting from the agreement, is a crucial outcome of empathy.

Optimism — Playful placemaking supports an opportunity to generate from possibility, reinforcing optimism as an outcome of the participation. The feeling of optimism rises overall across the community, leaving the participant with a positive outlook on how the project impacts them, as well as the contribution they have on both the community and the project.

Flexibility — Designing the built environment takes a great deal of flexibility and willingness to discover the answers together. Playful placemaking supports people and groups being flexible as they discover and analyze the community, as well as flexibility in how they participate. The activities support letting go of “this isn’t how we do it.”

Attunement — This biological phenomena is rooted in newborn relationships with parents and caregivers, allowing individuals to feel deeply connected with others throughout their lives. The heart of playful placemaking is to generate an experience of collaboration and co-discovery when designing the built environment. Attunement is a highly sought after state, occurring when participants play together in such a way that

evokes joyfulness and reactivates innate play natures of individuals. Creating emotional bonds, building investment in the project, strengthening the community to project team relationship, as well as committee member to committee member relationships are examples of attunement.

Problem Solving — This is the most obvious applicability as the design process is used most regularly as a mechanism for problem solving. Shifting from “Designer as expert” to “Community as collaborative problem solvers” is one of the most natural benefits of playful placemaking. Play allows all who participate an opportunity to not only inquire and study the problems, but to play in the brainstorming and consideration of opportunities and constraints. Play encourages the community to consider much wider solutions to deeper problems while feeling trust and empathy, making those solutions feel more impactful.

15

Joy in Movement — Many playful placemaking activities start in movement or are movementbased. When our participation with a group begins with movement, we are immediately shifted to a joyful state, and our willingness to participate and contribute increases. Additionally, there are therapeutic benefits realized when experiencing joy in movement, making playful placemaking unique in this outcome for all communities, but particularly in challenged or marginalized communities.

Three-Dimensional Thinking —

Much like problem solving, designing the built environment is a three-dimensional activity. A typical constraint found in engagement is the challenge for participants to easily understand three dimensionality, as it is a skill that needs to be fostered to use well. Playful placemaking activities support “seeing a project” with new eyes. Tours empower participants to be with the team in the real areas and spaces, while games and activities explore the many dimensions of the space beyond the physical three dimensions, including dimensions of culture, society, resiliency, etc.

Perseverance, increased mastery — Design

is a willingness to consider opportunities and possibilities over and over. Playful Placemaking creates a space to consider that the iterative nature of the design process is a delight rather than a waste. The project finds its design and its consensus in the perseverance of the team and the community the more it plays.

Emotional regulation and resiliency

— Typical design engagement meetings, as we know them today, may evoke a sense of powerlessness that can often escalate feelings of frustration, anger, or hopelessness with either the community or the project leaders. Playful placemaking activities, by their nature, support exploration in a setting that naturally supports emotional regulation. Engagement events often see participants “come ready for a fight” and then shift through play to be willing to explore considerations, or even better, to become advocates for the project.

Openness to receive inspired “Aha

moments” — The very best designs come from the community: their needs, their passions, what they find beautiful, and most importantly what would improve their quality of life. Eliciting this information

16

can be challenging. Many community participants are not even aware of what could be possible for their community, or the community itself has a low sense of self-worth. They may also be very rigid, sharing very few ideas, or believing “we can’t have this or that.” Each of these impact possibilities. Conversely, when designers come with “great visions,” the community may feel like the designers aren’t listening, or are pushing their agenda. Playful placemaking activities are designed to help the community discover for themselves and learn where they hold themselves back, where they limit their value, and what possibilities could be available for them if they were willing to see themselves and their community differently. “Ah-ha moments” are generated out of playful placemaking activities, allowing their possibilities to be realized fully as THEIR OWN.

Cognitive growth, innovativeness —

Designing for the built environment can often be limited to the designing of the actual THINGS that will go into the space, yet playful placemaking supports innovation, growth and development opportunities in the multi-dimensionality of

community. Activities may link economic innovation that might be needed in order to support social justice initiatives or economic innovation may be an anticipated outcome of the design that now needs a social system to better leverage these outcomes.

Belonging — Basis of Community and altruism

The most basic understanding of why community participation is needed can be understood in the idea of “belonging.” Belonging is a fundamental human experience and without it both individuals and communities are left incomplete. Designers, even with the best of intentions, do not “belong” without a willingness to listen, explore, and inquire. Community participants may feel as though they do not “belong” in the process of designing, saying “that’s why we hired you, the professionals.” Individuals may feel they do not have anything to contribute, and will stay away from speaking or participating. Playful placemaking activities naturally create a space for inquiry and exploration, where ideas and contribution are openly accepted and considered, but also ACKNOWLEDGED, with the design team and participants thanking one another for their contribution.

17

Much like the benefits of play, there is much to see in the alignment between what can be observed about play and the benefits and outcomes of playful placemaking when used to generate empowerment and possibility in the designing of intergenerational play and recreation spaces, sensory gardens, transportation centers, pocket parks, or any part of the built environment.

Observations about Play

It is voluntary, people want to do it and do it on their own accord.

It appears purposeless, but really isn’t. It supports long term life needs.

It is fun, pleasurable, and makes the player want to continue.

It is engaging, takes the player out of the sense of time.

Playful Placemaking Alignment

Playful placemaking is an invitation, participation is an opportunity, and it can be declined.

It really is a separate “state of being”.

Playful placemaking activities are often “at work” on the players even when they are not noticing. On the surface, many of the activities, from ice breakers to card games to collaging, often seem purposeless, but as the activities progress, participants generate and acknowledge their value for themselves.

Whether as part of a larger community event, or a workshop, playful placemaking sees people rotating through workshop exercises and repeating them, people staying later, and engaging in longer conversations.

Playful placemaking events regularly see participants staying late to finish collages, or to make several collages. Activities like community tours regularly see participants sharing more freely throughout the tour, people linger afterwards, and even connecting with others on the tour to “do something next”.

Playful placemaking regularly sees people shift from their standard story or complaint of “we can’t do that here” to sharing with new words and language, and to generate new possibilities. We regularly hear from people on tours that they’ve “never experienced their community this way”.

It does not occur if the player is fearful, sick or otherwise threatened.

All who engage in play, engage in movement or body play.

Often, traditional engagement events can have a perception of power where one side are experts that “know better” than the other. Interestingly, this can be felt by both the team and the participants simultaneously, each feeling like they either have the power or not. Playful placemaking is unique in that it supports a safe, collaborative environment to foster creative tension and exploration.

Many playful placemaking activities include movement, and can be seen as being therapeutic in and of themselves. Whether it is just standing up and moving towards the table with game cards, visiting workshop stations, using scissors and glue for collages or walking or biking on a community tour, movement is a key component of playful placemaking.

18

Humans are dynamic creatures, which results from rich and varied types of play activities. Research has identified five types of play that are an integral part of human development:

Movement Play

Object Play

Storytelling-Narrative Play

Creative Play

Social Play

Movement Play — Humans’ awareness about themselves and the environment around them begins through movement. Movement is primal and accompanies all the elements of play, forming the structure of human knowledge of the world. It is, in fact, a way of knowing everything around us4. We understand and experience that humans dance (moving their bodies) as well as hum and sing (movement of vocal cords and mouth). We understand running, jumping, swimming, etc. as forms of play; often seeing these as the most universal forms of movement play. But humans think in movement, and have crafted our written and oral languages to use terms like “close, distant, open, closed” when describing emotions or using “grasp, wrestle, or stumble upon” when referring to ideas5

Biologically, movement fosters learning, innovation, flexibility, adaptability, and resilience, making it an important part of keeping minds and bodies healthy at every age, as well as a useful communication tool.

Movement Playful Placemaking Experiences:

} In playful placemaking, we see a shift in participation and interest when we shift our movements. Many participants resist at first, as it is out of their normal experience for a project meeting or community event. Even small changes in movement; standing up from the table, or gathering around anything can make a real difference in how participants approach the activities.

} This small shift in movement through a kick-off activity, sets the stage for the rest of the experience to be fun and productive.

} Movement is invited at nearly every stage of the process. Community conversations are often held at markets, festivals, or other community events and they include a wide range of games and activities as part of the experience. Tours to explore places through some human-powered or “slow” movement are also important components.

} Trying It On is an even deeper exploration into movement and knowing a site through movement. Participants can experience the space in a way that no drawing or rendering can ever provide. Being able to literally move in the design concept shifts participants to a new relationship with the world.

19

Object Play — Our curiosity about and willingness to play with “objects'' is ingrained in us as humans, and we are not alone in our interest in this form of play. Humans and animals alike find joy and value in playing with toys. and starting at an early age, toys take on highly personalized characteristics, and as skill support in manipulating objects (i.e., banging on pans, skipping rocks, etc.). As we grow, those early manipulation skills expand with tinkering, building and taking apart, creating richer, more complex circuits in the brain.5 Hands playing with all types of objects help brains develop beyond strictly manipulative skills, supporting effective adult problem solving, with play as the driver of this development.

Object Playful Placemaking Experiences:

} Team Building and Kick Off games regularly include holding and sharing objects as well as games centered around name tags. Visualization activities include everything from flipping through magazines to using scissors and glue sticks. Try It On activities might include the use of physical object props such as hula hoops, buckets, boxes, chairs, trees and plants, food trucks, wooden palettes, inner tubes, and even musicians.

Storytelling-Narrative Play — Scientists note that storytelling has been identified as a central piece of human, and even species development.8 A critical function of the left hemisphere of the human brain is to continually create stories about why things are the way they are, putting disparate pieces of information together into a useful context.5 We learn from story and analogy, we share information in the form of story, and that information is retained more often when we relate personally to the story.

Storytelling-Narrative Playful Placemaking Experiences:

} Through storytelling, the community is able to relate to one another and to their physical space quickly. Using different visual activities, participants can share a wide range of stories about obstacles or opportunities, limitations or vulnerabilities, or the wide possibilities of dreams. When community members capture each other’s stories in ways that they can see and measure, they build trust and actively listen to one another.

20

Creative Play — Play is all about trying on new behaviors and thoughts, freeing us from established patterns.5 In healthy children, creative play is a constant part of their world and often goes unnoticed. This creative and imaginative play stays with us throughout our lifetime and forms the backbone of creative endeavors. When we engage in creative play at any age, we are free to explore new ideas without risk, which can generate new scientific breakthroughs, help us take on new hobbies that lead to business ventures, imagine our dream home or invent new devices that change the world. In each of these cases, people are using their playfulness to innovate and create.

Creative Playful Placemaking Experiences:

} Trying It On is an activity that is well-connected to creative play. It is an opportunity to wholly imagine and create a “make believe” version of the world the community wishes to create in real life. The group tries on, over and over, various design ideas and imagines themselves and others in each design. They can see constraints and opportunities that may have eluded them before. In order to build trust and find consensus it is important that play and fun continue as the building blocks of each Try It On experience.

Social Play — Humans are social creatures, and play forms the building blocks of human social health and wellness. Play experts note that subtypes of social play such as “Friendship and Belonging” as well as “Rough and Tumble” play are important in human development. Humans begin social play in a state of what is called “parallel play”, sitting next to one another, each engaging in their own activity. This play serves as a bridge to cooperative play.9 While we typically understand this as a childhood phenomena, we see this play out in adolescents and adults as well, particularly in new social circumstances or when undertaking a new task at work or new type of recreational activity. Humans will align themselves to observe, and try the tasks on their own, often before jumping into cooperative activities. Being able to jump to these mutual play opportunities is the backbone of developing empathy for others. Observing and seeing the contributions of others to the overall value of the experience supports their understanding of other points of view. This mutual play is the basic state of friendship that will be at work throughout our lives.

Social Playful Placemaking Experiences:

} Group dynamic experiences are perfect opportunities for social play. Notably, all versions of team building games, particularly the kick off games, set the tone for the social dynamic of the project or committee. Both large and small-group sharing games support active listening, empathy, collaboration, and negotiation. Acknowledgment is a key component of strong social play, and is equally valuable when the team is acknowledging public participants, as well as when participants are supported in acknowledging one another.

21

Strategies for Hosting Playful Placemaking Events

IT’S EASY TO GET STARTED WITH PLAYFUL PLACEMAKING. Through play, everyone can see the world with a unique perspective, letting go of the burden of “impossible”. After nearly a decade of public facilitation, Joy Kuebler has used her well-tested PLAYCE methodology to empower communities through the design of the built environment. Consider the next generation of community engagement, and it’s as easy as playing a game! You may be an architect, landscape architect, planner, engineer, or a student of any one of those professions. You may work for a municipality, act as a project leader for a community-based or private development organization, or are active in your block club, local historic preservation, or environmental stewardship organization. Whether you are leading, designing, or passionate about projects in your community, playful placemaking offers YOU a unique opportunity to lead facilitation through play. Use the following overview to get started.

22

When starting a project, you’ll want to identify who you will be playing with. Key participants for utilizing playful placemaking strategies include: Project Leaders, your Vision Group, and the Public at Large. The success of a project will rely on outreach and diverse engagement at various scales.

Project Leaders

The group that originated the project (i.e. municipal department leaders, business and market development partners or steering committee). These are the people that traditionally make the final decisions of what a project design turns into.

Vision Group

This group operates as the go-between for the public and the project leaders. They are the sounding board that helps you determine if you “got it right”. This group can include:

} Business Owners

} Community Activists

} Local Artists

} Residents AND Visitors

} Children and Students

} Older Adults

} Others that represent local demographics

Public at Large

These individual are your most valuable players and can be the most elusive. Unlike a vision group or project leaders, these folks are not “required” to participate. They bring broad community knowledge with their participation which can spell long term success for any project.

23

Through playful placemaking, you will create how and where you want to play. These strategies will help your community engagement sessions be more effective and valuable. You’ll be creating a new consideration for what is possible for a project or for a whole community. As stewards of the design process, it is important that your community partners understand that it may not be possible to incorporate all suggestions in the final plan, and that the input received will be documented and is critical to setting priorities in the overall design process.

Community Conversations — These correspond to the traditional public meeting, and offer a playful twist for participation. First and foremost, playful placemaking recommends “going to where the people are” rather than asking them to come to you. Farmer’s Markets, free music

Playful Placemaking recommends “going to where the people are” rather than asking them to come to you.

events, and youth sports tournaments are all great options because they include such a wide range of participants, young and old, locals and visitors alike. Additionally, one may consider coordinating with and setting up at the local grocery store, library, or medical center to connect with a wide range of people for a short but meaningful conversation. Because you’re going to where people are already gathering, you’re not spending resources on getting people to pay attention to and make space in their lives for your information session. That alone is a great advantage. Additionally, your awareness and

information gathering efforts are now including people who may not have sought you out, but have something to contribute to the conversation now that you have asked. It is important to have fun at these events; when you are having fun others will too, which will increase engagement.

In the playful placemaking process, your team should employ a variety of tools, the most important of which is the open ended “Compelling Question”. This is your opportunity to have a purposeful 2-3 minute conversation with a wide and diverse audience about what ways their quality of life could be improved, what they love from other communities, or what it would take for a neighborhood park to “feel loved” by the community. Be sure to include meaningful ways for the children to contribute as well, by empowering them with unique and fun ways to participate.

In addition to conversational opportunities, consider including a series of ranking questions and short open ended questions that can be answered easily by people walking by. These can also be used throughout the analysis phase in different areas, allowing a building of data points. Be sure to consider the season, the weather conditions, the

24

venue, and the diverse needs of the participants when designing and planning the event and activities. It is also important to consider how to gather outcome data from the event. Determine if some of the activities or compelling questions will be utilized in future events to have a data set gathered over a longer period of time. These Community Conversations can be held at any time, and even several times during the design process. They are a great way to launch a project, build champions, and support but are equally effective as a way to gauge the community’s response and gain feedback later in the process.

Public Meetings — Traditionally advertised public meetings are still valuable for an audience that is used to seeking them out for highly publicized or controversial projects, and are strongly recommend for the opportunity they bring. It is also strongly recommended to change up the programming and content to support more play. Playing keeps the experience rooted in cooperation, visioning, consensus, and building across many voices, making it more challenging for a single voice to dominate the meeting. Short presentations with workshop activities and a chance for community-led inquiries are great options.

When you are facilitating with play, you can connect, communicate, and positively interact with everyone and fully engage them in the process. Whether for a large public meeting workshop, or a smaller project committee workshop, consider hosting at unique and interesting venues, being mindful of event times that support your specific community or committee, and include access to refreshments if possible. You will want to craft a range of activities to support community relationship development, authentic sharing, and open dialogues about possibility.

TIPS FOR PLAYFUL PUBLIC MEETINGS

Nurture everyone’s imagination. Keep things at a high level, include a variety of playful activities that accommodate the needs of a wide range of participants, choose interesting locations, and make it family friendly. Consider having music, entertainment, and/or food to help create a welcoming atmosphere.

If possible, hold the meetings at the project location. People are very visual, and it’s easier for them to understand a place when they are in it.

Ask open ended questions. Consider asking “What makes a downtown vibrant?” or “If you could create anything within this space to make your family want to come back over and over what would it be?” These are questions that spur great conversation.

25

Tips for creating successful events (regardless of the scale):

} Identify a variety of key participants you are looking to have at the event:

A specific target audience should receive specialized invitations with as much advance notice as possible.

A wider public audience can receive information from flyers, direct mail, or email distribution lists. Consider coordinating with local agencies to have your event information displayed on their physical or digital signs. If possible, be a guest on a local radio or television spot that highlights community events.

Offer accommodations that meet the diverse needs and cultures of those in your community. For example, invitations may be created in multiple languages, sign language interpreters can be present for the deaf community, or food options meet a wide range of dietary needs.

Word of mouth is valuable, ask key figures in your community to share and spread the word.

Social media can be a terrific asset, and can include information before the event as well as the creation of a special event #hashtag for use during the event. If possible, consider having someone live streaming during your event, asking the online community to participate as well. Because the digital divide is a challenge in some communities, be sure to use a wide variety of marketing strategies techniques that work for your community.

} Great events include everyone knowing each other’s names. Have plenty of name tags and of course a sign-in sheet. Include a sign-up sheet for future events and activities as well, ensuring people know what events to look for as you build your invitation list.

} Share a clear agenda for the event, directions and facilitators for the various workshop stations, and an anticipated ending time, while allowing people to linger and ask questions.

} Capturing stories and activity outcomes is very important; Create the activities to support how you want to gather information and include one or more scribes from the team to capture more details. Photography and video are also wonderful considerations.

} Smaller community events or committee workshops should include time for sharing and debriefing between each activity, culminating in consensus around the workshop outcomes before proceeding with the next design process steps.

} Be sure to follow up with thank-yous, a recap of the outcomes, suggested next steps, and invitations to get involved.

} Invite public input through a wide range of electronic facilitation including online survey tools, Social Media polls, QR Codes placed on flyers or signage throughout the community for site specific surveys, or a simple email address where the community can send ideas. Electronic communications should be curated to support your individual project area, community needs, and skillset, and should not be relied upon for communities that may not have digital access and ease of use.

26

An update to the well known suggestion box may be a Community Chalkboard, strategically positioned throughout the community to gather input, and build champions. Be sure to place these in the project areas, as well as often visited locations like grocery stores, community centers and of course City or Town Hall community message board.

Site Analysis Tours — Site Analysis Tours are crucial to successful design outcomes. Often project owners and community members want to quickly move past them to create beautiful drawings. This critical component of design can be a valuable opportunity for community awareness and empowerment to generate a sense of ownership. The community knows so much about their place, and has much to share. It is also an opportunity for everyone to see the space with new eyes, allowing an opportunity to visualize potential outcomes. It may be tempting to host a variety of tours for various stakeholders, but suggests connecting with and inviting a wide range

of participants and voices for the tours will not only leverage those most knowledgeable about a site, it can create a collaborative problem-solving environment across varied interests, long before concept ideas are ever drawn.

Be sure to include a wide range of ages, as well as abilities. Consider specific invitations to school groups and families with children. Connecting with local groups that serve people with disabilities can help identify potential committee members and event participants. Additional targets include community groups, elected officials, community and business leaders and their representatives, potential funders, educators, parks/arts/public health/youth service advocates, parents, and children, among others. Department heads and public works personnel are important considerations as they may play key roles in everything from permits and approvals to long term management and/or maintenance projects after the ribbon cutting.

27

Moving at a human pace through spaces allows us to know them in ways that driving them, or remotely navigating them through interactive mapping software just can’t provide. It is at the human scale, that our body movement supports our brains to really know places. Utilize good old fashioned walking whenever possible. Understanding the context of a place is important to selecting the right tour mechanism. Covering more ground can be accomplished on bicycles, or “party bikes’’ that hold 10-12 people at a time. Golf carts can be provided as an alternative for people unable to bike ride. Waterfront access can be accommodated through water bikes, kayaks, or boats large enough for a group. A consideration for streetscapes or larger parks might be electric scooters or other personal motorized transportation.

Providing a tour packet with information to answer common questions or offer cues for your various activities can be helpful to participants. Consider how you will collect the data derived during the tours.

Team-Building Games

— These are key to building trust, empathy, and collaboration. Teambuilding games work well with a wide variety of participants in the settings of community conversations, public meetings, and site analysis tours. It is particularly powerful to use these activities for events with both adults and children. Children feel right at home with games and activities, particularly thinking, drawing, and collaging activities, and can sometimes help to facilitate the adults in the room.

It is important to identify what your project needs are and to select or craft games that will support the project needs as well as ease data collection. Adapt games from various sources and formats to create unique experiences that challenge participants to consider a wide swathe of possibilities.

28

Trying It On — For this activity, utilize low-cost, quick-to-build objects coupled with temporary activities and scenery to see and experience a place in a new way. Small scale Try It On activities can include using props such as boxes, buckets, hoops, paint, tape, chalk and other objects to continually try-on design idea after design idea. This is particularly well suited for community empowerment as design ideas generated from the group can be “experienced” right away and the benefits and challenges of the design can be visualized and discussed in real time. Sometimes groups will experience things they did not anticipate and the group can then design something “new” together to try on and then follow up with the same questions.

Larger Try It On activities may include the mockup of the determined design solutions, again using lightweight, low-cost materials to create a temporary experience to test the design in real time. This method can be used for testing actual spatial considerations of the design such as fire truck radius, lengths of crosswalks, or how in-street rain gardens will work with parallel parking. A second and important outcome of this technique works at the fundamental level of community identity, and aligns to the knowledge that “In play we can imagine and experience situations we have never encountered before and learn from them. We can create possibilities that have never existed but may in the future. We make new cognitive connections that find their way into our everyday lives. We can learn lessons and skills without being directly at risk.”5

During Try It On, the community experiences a transformation in its willingness to see themselves and their community in completely new ways. In order for the community-at-large to be willing to try it on, there must be an accompanying festive atmosphere about the activity, with programming

that closely aligns with the intended design thinking. Streetscapes may include “pop-up” food or shopping opportunities alongside the newly painted bump-outs with borrowed trees and shrubs filling in the rain gardens. Park projects may include sprinkler arrays and blow up kiddie pools to represent a splash park, or buckets with fresh, compost-rich topsoil next to tables of fresh produce and cooking demonstrations where the proposed community garden will be. Don’t forget food, drinks, and music for your community party as well. For these projects borrow as many materials and resources as possible, coordinating with municipal departments and local nonprofits for support with labor and awareness. This event will need a marketing and awareness plan, so coordinating with local media and other organizations can be highly beneficial.

“In play we can imagine and experience situations we have never encountered before and learn from them ... We can learn lessons and skills without being directly at risk.” — Dr. Stuart Brown

29

30

Measuring Outcomes and Planning for Success

WHEN MEASURING THE OUTCOMES GENERATED THROUGH PLAYFUL PLACEMAKING; CAPTURING DATA IS KEY TO SUCCESS.

} Collect, organize, and record results of each activity and game, community tour, conversation, survey, and collage. Ask a few community members or members of your team to be scribes for each event, ensuring there are several listeners for the wide range of conversations. Encourage scribes to verify with the group if the sentiment of the conversation was captured correctly.

} Video and photography are very important. There should be photographic documentation of all visioning activities, meetings, and tactical interventions. Take the opportunity to make short interview videos with participants as well.

} Summarize and organize your results. Through the use of frequency matrices, you’ll be able to identify where the participants are or are not in alignment. Results will identify consistencies from the most macro data to the most micro, as well as “outlier” ideas that were valuable but not widely shared across groups. Data will reveal disconnects and how they will impact the project’s mission as well as possible design outcomes.

} As project findings are produced and design solutions become clear, reach out to the community again to gauge support and request feedback.

Prioritizing — Deciding what areas to prioritize and timing is one of the final outcomes of the process. A strictly linear process may not be as implementable as one that reaches towards what will empower a community at the onset. For example, looking at what is most easily attainable can be one of the easiest ways to launch a project, or to determine appropriate phasing. Generating alignment on what the community sees as implementable in the next six to twelve months and what resources would be needed to advance those ideas is crucial to this phase.

Identifying the “bigger version” projects that take more time and funding sets the larger planning efforts in motion. These are the projects that could be realized in the next five to ten years. These larger, more impactful projects are built directly from the engagement outcomes, but take greater coordination and planning. It is important to note that these projects may have a greater chance of success when they can leverage earlier successes rather than being the first projects out of the gate.

Projects not yet implemented in a seven to ten year period should review the engagement process.

31

Project ideas that remain likely fall into the “bite sized & easy to handle” category and can be achievable when timing aligns to leverage funding or community will. These projects can also share resources across agencies to increase impact when available. These can be taken on when community enthusiasm is high and when they have realized a positive return on previous project efforts.

Funding — When using the playful placemaking process, a story of community support and participation emerges as participants align around a common cause and goal. Utilizing this story, in partnership with evidence-based data to support the need and potential outcomes, can help make a compelling case to funders about the positive benefits the project can have on the community.

In August of 2020, via the Great American Outdoors Act, the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) was permanently funded at $900 million annually, offering funding opportunities for eligible projects to support land acquisition, recreational facility improvements, and park planning projects. Every project starts with a great idea, and members of the

community play a critical role in addressing needs, challenges, and even providing new ideas that play a valuable role in the overall outcome of these projects. Applicants are required to demonstrate ways community impact was collected and used to inform the planning and development of proposed projects. A detailed outline of public meetings, surveys, and the public engagement process is part of successful applications for funding sources such as the LWCF State Assistance Program.

Often clients ask how to facilitate these more participatory community engagement meetings with a limited budget. In the typical construction contract or project outline, there are generally opportunities to conduct a site analysis. As a component of the site analysis, invite the public and play games to ensure the site analysis is as meaningful and worthwhile as it can possibly be. There may also be opportunities to assist in conducting the public meetings that are already in the project budget or scope. This is a great way to utilize budgets that are already allocated for public meetings to ensure playful placemaking can be part of the process to gather feedback and generate creative ideas.

Great visioning provides a framework that has been generated at the widest community level, allowing for pursuit of funding that is truly in alignment with the community’s vision.

For internal project managers such as city planners or parks and recreation professionals, when considering or interviewing landscape architects or design teams, be sure to discuss how they are seeking public feedback or input. You can also request a specific level of engagement in the request for proposal (RFP) process for architects and designers to include different engagement activities and make them part of your contract requirements.

For landscape architects, design the engagement processes to support the project you are working on. Outline the process you will use, using this document as a guide. Include language in your proposal on the benefits to the client, project, and community in your proposal and contract.

32

It’s also worth noting that the successes of Try It On experiences often lead to more advocates and an even greater drive to pursue additional funding for project ideas generated from the activity. This leads to an organization continuing the process to obtain more funding and additional community support through championing, volunteerism, and funding.

This resource serves as an opportunity to link what we know anecdotally about the role of play and playful placemaking methods to the real and documented science of play. Its purpose is to empower collaboration among communities, their agents, and designers to create meaningful built

environments for everyone. Play may be the key to transforming the conversations currently prevalent in the world of design, community development, and investment in placemaking because PLAY works.

Play allows access beyond limitations such as language, culture, cognitive ability, age and mobility while encouraging inclusivity and support for the equitable expression of diverse voices and viewpoints. As an engagement tool, playful placemaking is a generative process that meets communities where they are, and offers a deeper way of participating and influencing the creation of their built environment.

33

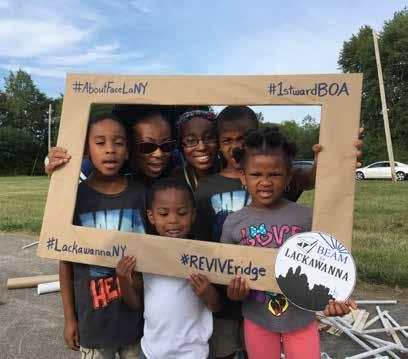

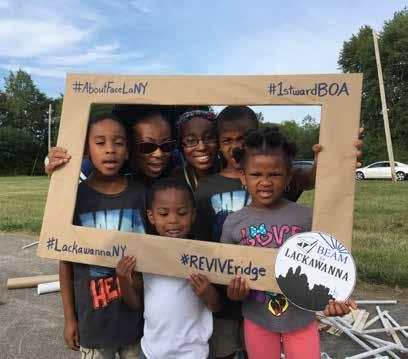

Case Study: Lackawanna Brownfield Opportunity Area

Lackawanna, New York

LACKAWANNA, NY IS RESPONSIBLE FOR PRODUCING THE STEEL USED THROUGHOUT

MOST OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES. At the time it opened, Bethlehem Steel’s Lackawanna facility was the United States’ second largest steel manufacturer and it continued to support the US and western New York until the 1980s. Lackawanna was created by Bethlehem Steel specifically as a “Steel Town'' to house everything from factory buildings, administrative buildings, to a complete neighborhood for its vast labor force. It was carved out of nearby Cheektowaga, and placed directly on Lake Erie’s waterfront.

Like many rust belt communities, decades later, Lackawanna now faces the challenge of containing and cleaning these now contaminated landscapes. But beyond Brownfield cleanup is the greater challenge of restoring citizen trust and confidence, physically rebuilding communities, establishing new industry, and finding ways to create jobs, all while being true to the diversity and values of these communities.

In a “playful planning” approach utilizing Joy Kuebler’s PLAYCE methodology, the community is identifying high priority areas, including returning Ridge Road to its useful state as a thriving Main Street for the Old First Ward neighborhood.

“All this is about incrementally building a resilient and sustainable wave that will make future generations look at Lackawanna differently.”

– Fred Heinle, Lackawanna Director of Development

34

Steering committee meetings and neighborhood tours have focused on eight specific areas within Lackawanna’s Old First Ward including portions of the former Bethlehem Steel factory itself, the former Administrative staff neighborhoods, an adjacent creek corridor, and the Ridge Road corridor.

As part of the public engagement process for the Brownfields Opportunity Area (BOA) the team decided to use a tactical urbanism event to supplement traditional “public meetings” in ways that helped the community better understand the BOA planning process, as well as explore design ideas.

The neighborhood surrounding Ridge Road is filled with modest, yet well cared for private homes sprinkled amongst vacant buildings and lots. The neighborhood is one of the most diverse in Western NY, but also amongst its poorest. Walkability within the neighborhood is high, but upon reaching the “Main Street” area, it is obvious that essential services like grocery stores and restaurants have moved too far away to reach on foot.

The “Revive Ridge” tactical event became an opportunity to explore what restoring basic daily needs could look like, in addition to exploring how

building mass, scale, setbacks, and even facades could marry Lackawanna’s past with its future. This festival “fit” out the store fronts with food trucks to act as restaurants, a mobile vegetable market to be the grocery store, local merchants providing goods for “specialty shops” and even a famous local blues band to replicate a long gone, but infamous, blues bar.

Residents and visitors came to experience all Ridge had to offer and to have significant conversations with the team about the positive and negative implications of this type of urban infill in their neighborhood.

This particular project unearthed a great many ideas through the playful placemaking methodologies and continues to reap benefits from the original engagement process. Years later, sections of this planning document are coming to life. After the original desired outcome of the project, the waterfront trail, became reality, Lackawanna is now implementing other pieces of the project that came to the forefront during the community conversations, and implementing important community stories through art and artifacts from the steel manufacturing era of the area.

35

Case Study: City of Tonawanda

Local Waterfront

Revitalization Plan

Tonawanda, New York

WATER WATER EVERYWHERE… The City of Tonawanda is surrounded by water and has a history that is steeped in it, but today it plays a limited role in daily life. Through Urban Renewal work in the 1960s much of the Erie Canal legacy was removed. Now, Western New York has been leveraging the heritage of the Erie Canal as part of its revitalization story, and one of the canal’s most important locations can once again be part of the conversation. As part of the local waterfront revitalization (LWRP) process, the city will be strengthening the role of water in everyday community life, and reimaging key areas of the waterfront to once again tell the story of the Erie Canal.

The LWRP process creates a plan to allow Tonawanda to leverage its water story for business development opportunities both at the water’s edge and into the downtown business area. The plan will address environmental concerns at all waterways, and support the environmental health of the waterways for habitat areas and eco-recreation tourism opportunities.

At the heart of the plan is the goal for Tonawanda to once again be a true waterfront community, so the power of the water enhances daily life for residents, proximity to it drives job growth and business development, and the community is the driving force behind the health of its surrounding ecosystems.

Partnering with Joy Kuebler, they used her PLAYCE methodology in a playful placemaking approach to engage citizens with the LWRP process. Water is a vital and important part of Tonawanda. While industry uses the water less, the opportunities for recreation and commercial uses that leverage the water and lure and retain citizens are prevalent. Additionally, more than 75 families and individuals took part in the Niawanda Art Walk where Community Conversations took place about how they interacted with the water now and what they would like to see in the future.

“I’ve lived in Tonawanda my entire life and I have never seen the water the way I have today… thank you…”

– Resident and project participant

36

Site Analysis Tours were conducted along Two Mile Creek, the Niagara River, Erie Canal, and Ellicott Creek. The tours consisted of walking and boating excursions that allowed participants to see the sites up close and to discuss their conditions and opportunities. Each tour used a facilitation game to get the project team to become collaborative problem solvers.

Upon seeing the untapped potential of Ellicott Creek, the Steering Committee decided a tactical urbanism event would be a good opportunity for the community to see the creek in a new way. The “Crazy Creek Party,” complete with inner tubes and canoes, focused on leveraging both the ecotourism and natural conditions of the creek heading east, as well as identifying potential business development opportunities heading west where the Creek meets the Erie Canal. The family-friendly event had something for every visitor and partygoer and provided a venue for valuable discussions around balancing the health of the environment with commercial interests, and data collection about how often the creek is used by residents and visitors and for what purposes.

This engagement process formed the foundation for a “living document” style plan for the City of Tonawanda to reconnect its community to its waterways. This document paved the way for Tonawanda to pursue funding and plan the use of its existing resources for many years to come. Since the community engagement sessions, Tonawanda has received a special $2.5 million grant to reroute traffic through their downtown from a water edge road and convert the road into a water edge park with a newly created water edge pavilion. Additionally, the State chose to route its new Empire State Trail, now the longest contiguous trail in the state, through this newly created waterfront park.

37

Case Study: East Spring Street

Williamsville, New York

THE STORY OF THE VILLAGE OF WILLIAMSVILLE CANNOT BE PROPERLY TOLD WITHOUT INCLUDING MENTION OF THE MILL. In 1811 the Mill became the center of industry for the Village of Williamsville, and 200 years later the Mill is once again at the heart of the Village’s story. After decades of neglect, this historic industrial area along East Spring Street has become a much beloved Village Center through economic redevelopment and green infrastructure.

The introduction of green infrastructure (GI) allows East Spring Street to have a pedestrian focus for the first time ever. Greenspaces between public and private properties, permeable sidewalks/parking lanes, and large shade trees planted in engineered soils all work together to capture and filter stormwater. These GI interventions help strengthen the visual connection to the adjacent Glen Falls Park as well as create an inviting plaza suitable for everyday retail and weekend farmer’s market/seasonal festival use. The space now balances people and automobiles while celebrating Williamsville’s original industrial center.

“The green stormwater retention project right here on Spring Street will help the village preserve the pristine beauty of Glen Falls and allow the village to decrease the amount of stormwater that goes into the sewage treatment plant, all the while improving the quality of life, both for residents and those who come here to visit and shop”

– Senator Charles Schumer

38

Because the project area had languished for decades, it was important that the community be part of creating a new vision for the Mill and East Spring Street. After some discussion, Village leadership created a new temporary streetscape design which became the focal point of a weeklong festival that allowed residents and visitors to “try a new design on for size”. Over the course of this festival the automobile dominated street and parking lots were transformed into a pedestrian friendly streetscape and plaza replete with opportunities for the community to engage and respond to the new design before it was even constructed.

As the design moved forward a liability was identified — stormwater run-off, would be its strongest opportunity for redevelopment. Through New York State (NYS) Environmental Facilities Corporation and NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, green infrastructure became the driving force behind bringing the community’s vision of “a pedestrianfocused Village Center at the historic Mill” to life. Joy Kuebler’s Try It On activities led to greater community support and interest for the project. It received nearly $3 million in funding to capture and filter stormwater run-off through sidewalk planters and permeable pavers installed on the new pedestrian plaza at the Mill It also later received an additional $250,000 to support the finishing touches on this newly imagined place. In addition, the design included the elimination of erosion and sedimentation through the innovative use of a living wall system to both stabilize the escarpment and filter stormwater.

39

Case Study: Bailey Green Neighborhood

Revitalization

Springville, New York

HARMAC MEDICAL PRODUCTS HAS BEEN HEADQUARTERED IN THE BAILEY GREEN NEIGHBORHOOD FOR 40 YEARS. 25% OF THEIR 400 EMPLOYEES LIVE IN THE AREA AND AFTER YEARS OF DISINVESTMENT AND CHALLENGES SUCH AS CRIME AND VIOLENCE, HARMAC chose to deepen their commitment to the neighborhood. They chose to stay on Buffalo’s East Side and be a catalyst to stabilize the neighborhood with support and opportunities. They began to partner with organizations big and small to clean up vacant buildings and land and bring further stability and opportunities to the community.

n 2014, HARMAC engaged the University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning to complete a master plan for revitalization, with a primary focus on a neighborhood structural plan. After some years of success revitalizing the community, HARMAC engaged the University again to be involved for a longer period, in order to revisit and strengthen the plan while encompassing community engagement to ensure local residents’ voices were heard. The University reached out to Joy Kuebler, JKLA, PC to join as an adjunct professor with a dual purpose of teaching engagement strategies to the students while facilitating the community interaction. This doubled the impact as the students learned more about engagement as the community interacted with them as the facilitators.

“I think it’s time to get the Community Block Club back together.”

– Raymond Moss, Community Neighbor

40

In February 2022, the first community event was held, where residents and key project stakeholders toured the neighborhood playing games together to build trust and understand each other on a different level. This event also helped JKLA and the students meet residents and get a better sense of the community from them. From this meeting and their own research, students gathered demographics and information about the context of the neighborhood and put together their own site analysis.