Best Practice Guidelines

Infusing play into pathway networks to encourage active lifestyles for children, families, and communities

Proudly Sponsored By:

Advisory Committee

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Roger Bell Vice-Chair, American Trails; Retired Owner, Bellfree Trail Contractors; Board Member, Professional Trailbuilder’s Association

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Research, documentation and manuscript preparation by the Natural Learning Initiative:

Robin Moore, Dipl.Arch., MCP, ASLA, author

Adina Cox, BLA, MNR, ASLA, Research Assistant

Brad Bieber, MLA, ASLA, Design Associate

Nilda Cosco, PhD, ASLA, Education Specialist

Julie Murphy, MLA, ASLA, Design Associate

PlayCore representatives that have supported this initiative.

American Trails Advisory Committee members.

Others who have assisted, both individuals and organizations.

© 2010 PlayCore Wisconsin, Inc. and Natural Learning Initiative, College of Design, NC State University.

All rights reserved.

Pathways for Play is a trademark of PlayCore.

Suggested citation:

PlayCore and Natural Learning Initiative. 2010. PathwaysforPlay:BestPracticeGuidelines. Chattanooga, TN: PlayCore.

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of the Pathways for Play guidebook is to raise awareness and provide education about some considerations for incorporating play into trails and pathway networks; it is not to be considered as an all-inclusive resource. Please refer to the manufacturer specifications and safety warnings, which are supplied with playground equipment, and continue with normal safety inspections. Safety goes beyond these comments, requires common sense, and is specific to the pathway system involved. While our intent is to provide general resources for encouraging children and families to utilize trail systems, the authors, program sponsor, and advisory committee members disclaim any liability based upon information contained in this publication. Site owners are responsible to inspect, repair, and maintain all equipment and surfaces and manage site specific supervision sightlines, landscaping, and safety requirements.

The Natural Learning Initiative, PlayCore, and its divisions provide these comments as a public service in the interest of infusing play into pathways while advising of the restricted context in which it is given.

John R. Collins , Jr., PhD, Board Member, American Trails; Associate Professor, Department of Kinesiology, Health Promotion, and Recreation, University of North Texas

Chuck Flink , FASLA, President, Greenways Inc.

Marianne Fowler , 2nd Vice-Chair, American Trails; Vice-President of Federal Relations, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

Pam Gluck , Executive Director, American Trails

Philip Grymes , Executive Director, Outdoor Chattanooga

Terry Hanson , Board Member, American Trails; Retired Project Manager, City of Redding Community Services; Independent Trails Contractor

Woody Keen Founder and Owner, Trail Dynamics LLC; President, Professional Trailbuilder’s Association

Scott Linnenburger , Board Member, American Trails; Principal, Kay-Linn Enterprises

Stuart Macdonald Advisory Board Member, American Trails; Manager, National Trails Training Partnership

Jim Meyer Founder and Executive Director, Trails4All

Candace Mitchell , Communications Coordinator, American Trails

Jennifer Rigby Board Member, American Trails; Founder, Acorn Naturalists; Director, The Acorn Group

Robert M. Searns AICP, Chair, American Trails; Founder and Owner, The Greenway Team

Sara Sundquist Program Coordinator, Safe Routes to School Program, Shasta County Public Health (CA); Program Coordinator, Healthy Shasta

Jim Wood Board Member, American Trails; Assistant Director, Florida Office of Greenways and Trails

1 Preface

2 Introduction

4 Background

6 Supporting Research

10 Benefits of Playful Pathways

- Extending play value

- Enabling health promotion

- Expanding inclusion

- Engaging with nature

- Reinforcing environmental literacy

- Walkable, bikeable community connectivity

- Growing community social capital

18 Case Example

- Hinshaw Greenway Cary, North Carolina

19 Infusing Play into Pathways

- Playing along the way

- Planning play pockets

- Assessing playful pathway potential

26 Case Study

- Riverpoint Park Chattanooga, Tennessee

28 Best Practice Design Principles

1. Infuse play and learning value into pathways

2. Create shared-use, inclusive pathways

3. Connect pathways to meaningful destinations

4. Locate pathways where children live

5. Apply appropriate themes

38 Case Study - South Creek Linear Park Springfield, Missouri

Building your

-

process - Frameworks for action 48 Sustainability - Building a community of interest - Sustainability checklist 52 Online Resources 53 Call to Action 54 End Notes 57 Glossary of Terms

40 Implementation

Pathways

Step-by-step planning

Introduction

All children need access to opportunities to activate, stimulate, and exercise their potential in mind, body, spirit, and social relations, including their creative abilities for understanding and transforming their inherited world. Pathways for Play is based on the belief that this multifaceted experiential life of the child is best supported by the rich natural diversity of the outdoors.

Olmsted is also credited with the first built example of a greenway (more like a linear park), the seven-mile “Emerald Necklace,” which started construction in 1878 to connect many of Boston’s prominent open spaces.

If you had the opportunity to go hiking with your family, friends, or youth group as a youngster, you can surely remember the smell of the trees, the texture of the natural ground surface underfoot, and the closeness of your family or peers as you played together and made discoveries along the way. Perhaps such trips were made by bicycle and covered a larger, more dramatic territory. Such lifelong memories reflect a rich childhood full of engaging, healthy activity.

Just a generation ago, the large majority of children found their own natural play spaces in the nearest city vacant lot, patch of woodland, or fenced backyard. Today, many children have lost easy access to natural play spaces due to urban sprawl, parental apprehension, perceptions of crime, and heavy street traffic. To confront these issues requires a paradigm shift in the way we design and re-design neighborhoods, intentionally taking into account promotion of children’s play and independent mobility – basic requirements for health promotion.1

This is not a new idea. In 1866 the concept of shared-use recreational pathways was launched by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux who conceived a network of wide, tree-lined avenues that would cut across the grid of Brooklyn and link its open spaces.2

The value of shared-use pathway networks is becoming recognized as a health promotion investment in municipal and county parks and open space systems3 but often they have tended to emphasize athletic, young adults as users, rather than children and families. Although most trail owners/operators include families and children in the description of core users they wish to attract, these populations represent a small proportion of actual users.4 In theory, pathway networks could at least be as interesting as urban parks because they provide family recreation opportunities for walking that are more interesting, quieter, and safer than city sidewalks. Adults interested in nature are more likely to find nature experiences along pathways.

PathwaysforPlay describes a new paradigm of traffic-protected, playful pathways connecting children’s homes to meaningful play destinations in the neighborhood and beyond. The main purpose of this publication is to advocate for children, youth, and families as pathway user groups and to demonstrate technically how this can be done to help dramatically increase use by infusing pathways with play value.

PathwaysforPlay is also an educational resource, designed to help professionals and community activists involved in planning, designing, and promoting playful pathways to increasingly make pathways more playful, usable, and attractive to children and families – in two possible ways: a) by upgrading existing systems, or b) by planning and designing new systems.

Pathways, trails, and linear parks have a long and highly respected lineage. In 1866, the prolific Frederick Law Olmsted (considered founder of landscape architecture in the United States) and partner Calvert Vaux (in 1858 they had collaborated on the design of Central Park) proposed a network of shared-use recreation pathways in Brooklyn. In 1878, construction began on Olmsted’s design for Boston’s Emerald Necklace - an interconnected mix of greenways, linear open spaces, and parks. (Above)

Our work is about our families, our friends, our kids, our future. We’ve finally figured out that our communities are living systems and that they have unique and important properties that must interrelate so they can thrive. When natural systems and built systems are in sync, they can begin to heal the damage done to our land and our culture and begin to regenerate our neighborhoods and communities.5

Rick Fedrizzi President and CEO Founding Chairman U.S. Green Building Council

2 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Introduction

n Introduction 3

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines

Courtesy of the National Park Service

Courtesy of Emerald Necklace Conservancy

Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Olmsted’s original drawing; (right) historic view of users of the broad pathway; (far right) the Emerald Necklace today, offering young cyclists a healthy ride and inumerable adventrues along a gently curving tread under mature shade trees, parallel to the watercourse on the left.

Background

The purpose of PathwaysforPlay is to integrate play – critical for children’s health, into walkable, bikeable, shared-use community pathway networks infused with “play pockets” providing opportunities for playing along the way.

In the last 40 years, the number of children and adolescents in the United States walking or bicycling to or from school has dropped from approximately half to fewer than 15%.6 Innovative pathway designs infused with play is a paradigm change that could increase children’s walking and biking habits by offering a network of intriguing linear play environments connecting children’s homes to playgrounds and other meaningful, daily life destinations.

The term pathway covers all forms of network infrastructure, including greenways, trails, and sidewalks, that are used by pedestrians and cyclists to move around urban/suburban neighborhoods and mixed use developments. A related, commonly-used term is shared-usepathway, which is a path designed to accommodate bi-directional mixed use, including pedestrians, bicyclists, joggers, in-line skaters, fitness walkers, people with dogs, strollers, and users of wheelchairs and other assistive devices. The term is also used for Safe Routes to School pathways that connect sidewalks and other active transportation segments. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Guide recommends a minimum tread width of 10 to 12 feet according to expected levels of use. Infusing play into pathway networks will encourage children’s playful, independent mobility – and create an everyday active lifestyle option for all family members.

The term playpocket covers all forms of spaces and facilities identifiable by children and caregivers as play environments integral to playful pathways. Play pockets may contain a mix of natural, living, and manufactured elements located on and linked by playful pathways. Play pockets may vary in size and complexity.

Trail and pathway building in locations ranging from city center to remote backcountry was galvanized nationwide in 1983 with passage of the National Trails System Act (NTSA). Today the system totals over 60,000 miles in all 50 states (longer than the Interstate Highway System) and includes 11 National Scenic Trails, 19 National Historic Trails, and more than 1,000 National Recreation Trails spanning over 11,000 miles in every state, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.7

The Rails-to-Trails Conservancy Urban Pathways Initiative makes trails available to children and families in inner-city neighborhoods across America. Where green space is scarce, these urban trails open up new worlds. You can exercise, run errands, meet your neighbors or just goof around after school. If you don’t have a yard and there isn’t a park nearby, the trail may be the only public space you have to enjoy and explore. Rarely does a strip of safe pavement become more meaningful…these pathways ensure that children everywhere—in rural, suburban, and urban communities—can experience the simple joy of riding their bikes and playing in a safe place.

Keith Laughlin CEO, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy

Contrasting development contexts include “greenfield” suburban development, which still accounts for the majority of new construction driven by population growth and lower land costs (and infrastructure government subsidies). On the other hand, “urban infill” options are increasing as the potential of “brownfield” and “greyfield” developments demonstrate the economic, social, and aesthetic possibilities for healing post-industrial landscapes. This latter development form typically involves varied stakeholders in existing communities trying to attract talented, discriminating workers by adding social value to the built environment. Health promoting, walkable, bikable environments are often part of the solution and typically result in interesting spaces woven into the surrounding land uses and building structures.

The two primary advocacy and technical assistance organizations promoting pathway and trail developments are American Trails, created in 1988 with the merging of two older organizations, and the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, founded in 1986. Both organizations advocate use of pathways and trail systems by children and families.

The potential of converting rail rights-of-way to public pathways, supported by the “railbanking statute” of the NTSA, is dramatically reflected in the conversion to date of 1,600 miles to pathways (with more than 9,000 miles of right-of-way waiting to be built) throughout the country.

PathwaysforPlay will broaden the range of local community options for improving children’s access to nature. NatureGrounds, the companion program to PathwaysforPlay is already underway to naturalize thousands of playgrounds at parks and schools across America through intentional site design, using existing topography, and integrating plant material, such as trees, shrubs, and perennial flowering plants with manufactured play equipment.8 Playful pathway design will extend play-in-nature by creating attractive, playful routes for children and families.

4 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Background

PathwaysforPlay helps communities create networks of shared-use pathways, infused with play pockets, usable by all for healthy recreation and non-motorized transportation to connect meaningful destinations.

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Background 5

Supporting research

Today, although trails exist in city, suburb, and open country, it appears that only a small minority of children and families are actually using them. Pathway use by children and families is underrepresented in research and practice. Why, is unclear. Perhaps it is because previous generations took children’s independent mobility for granted. When children were out and about, they traveled on pathways of one kind or another, and no one thought much about it, except for high-traffic streets, which parents used to set boundary limits.9 However, a convincing case for deliberately re-activating the pathway idea can be made on the basis of requirements for healthy child development and related built environment requirements as well as historic precedent.

Spontaneous play

Spontaneous play (children playing together without direct adult intervention) is recognized by child development experts as a crucial aspect of healthy childhood.10 Ideally, it should happen outdoors where sufficient space is available. Play and physical activity have a critical role in protecting and supporting children’s health and well-being.11 In a commissioned report to the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Kenneth Ginsberg, a leading pediatrician, wrote that “play…is essential to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children and youth.”12 The Academy recommendation reinforces the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) minimum recommendation of 60 minutes of daily moderate to vigorous physical activity for children.13

Outdoor physical activity and pathways u

When children are outdoors, they are more likely to be engaged in higher levels of physical activity.14 They are more fit than those who spend the majority of their time inside.15 In addition, children who play in natural areas also exhibit a statistically significant improvement in motor fitness with better coordination, balance, and agility.16

Pathways attract children’s physical activity. Studies conducted by the Natural Learning Initiative (NLI) in childcare centers, zoos, and parks consistently show pathways as high use settings supporting higher levels of energy expenditure by children.17 Cosco’s comparative study of three preschool outdoor environments showed that the site with a continuous, sinuous pathway and a mix of natural and manufactured components was the most active.18

Varied pathway use may result from differences in social and physical context, access conditions, and/or specific characteristics of the pathway tread and its immediate surroundings. Pathway planning and design factors such as these are under researched and inadequately understood even though trail development has been a national priority for almost 30 years. However, the dramatic rise in childhood obesity and related health issues linked to sedentary childhoods has forced a revaluation of the health and child development functions of outdoor play and the community infrastructures required to support them – including pathway networks. While specific pathway research related to children is lacking, it is possible to infer several potential impacts of pathway use.

Pathways can offer continuous exposure to natural processes for young users to explore. Insect life never fails to stimulate the curiosity of young children.

In contrast, a study that examined three rail-to-trail greenways located in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Dallas found that only 6% of trail users were under the age of 18 and only 2% were seniors.19 However, a recent study observed higher use levels for a winding, wooded pathway (Hinshaw Greenway), easily accessible from adjacent housing and connecting two neighborhood parks in Cary, North Carolina (see p.18). In this case, 30% of users were under 18 and 9% were seniors.20 Use by seniors is a relevant consideration because many seniors are grandparents, often with more time available to accompany children on pathway adventures. The success of the Hinshaw Greenway may be explained by comparing the intimate, leafy shade, and sinuous quality of its tread to the large scale “straight ahead” character of the three pathways in the earlier study, which may work well for adult cyclists but not for children.

Movement is essential to the healthy development of children while continuously exposing them to new experiences and learning opportunities.

Movement is a fundamental characteristic of children’s play and provides a special, multifunctional impact on cognitive development through several facets.

Proprioceptive describes movement of limbs connected to the rest of the body – a dancer’s sense of knowing where her or his arms and legs are and their intended contribution to the expressive gesture of the whole body.

Vestibular describes the body’s interaction with gravity and the pleasurable stimulation of the inner ear experienced as we swing, slide, or roll down a hill.

Kinesthetic describes movement through space, which is most relevant to pathway use; however, it is generally recognized that all three senses continuously work together.21

Range development is a further facet of movement, which describes the dynamic geography of a child’s experiential world expanding with maturity level.22

For infants and toddlers, play is continuous during waking hours. Play occurs wherever the child happens to be (home, childcare center, community) and in the care of parents or other caregivers (which may include older siblings).

As early childhood advances, children become both capable pedestrians and expert tricyclists as well as learning to ride two wheels. By primary grades, children are genetically programmed for independence and need play environments that support independent, spontaneous play –particularly outdoors, where sufficient space is available. Cognitively, children are still piecing together the geography of their daily territory, which may extend to sidewalk, cul-de-sac, interior courtyard or other close-to-home protected space. With parental help, children at this stage learn to judge speed and distance of moving traffic.

In the middle childhood years (approximately 8 to 12), children are sufficiently mature to rapidly extend their independent play territory away from home. At this age, access to extensive pathway systems, which parents perceive as being protected from traffic, is essential for range development and therefore neighborhood play.

Movement play lights up the brain and fosters learning, innovation, flexibility, adaptability, and resilience. These central aspects of human nature require movement to be fully realized.

Stuart Brown, MD23

6 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Supporting Research

u Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Supporting Research 7

Movement u

Independent mobility u

In middle childhood, children move away from home to explore and understand the physical and cultural characteristics of their community, to have adventures in company of friends, to take developmentally appropriate risks, and to overcome the challenges of exploring and learning. Independent mobility is social and typically involves a peer group of siblings and/or friends – or at least a pair of “best friends.” Natural groupings may include a wide age range whereby children learn from each other. A single child rarely ventures out alone. Attentive parents realize this and understand that meaningful childhood adventures are shared, peer group experiences – recounted when back home to parents willing to listen.

Through play, the developmental drive of childhood is exercised to its full potential. Neighborhoods designed to serve children must offer meaningful destinations and safe routes linking them so that children’s curiosity and drive to play are freshly prompted each day.24 The Safe Routes to School program and related research have become a rich source of understanding about children’s independent mobility. Physical health benefits are clearly demonstrated.25 Playful pathway connections provide additional play opportunities especially on the way home “from” school when children have more time to “play along the way.”26

Reducing traffic danger u

Fast moving, dense traffic has become a major deterrent to independent mobility and neighborhood play. Fear of traffic is a primary reason why parents will not let their children roam outdoors,27 which is highly justified given the risk of injury in traffic environments.28 When asked, children themselves rank a safe traffic environment high as a dimension of child-friendly cities.29

Designing pathways that maximize both actual and perceived traffic safety can benefit all users. Actual danger can be reduced by built environment interventions in the pedestrian/traffic interface combining elements such as curb extensions, pedestrian refuges, and raised road surface grade platforms at pathway street crossings. Perceived danger can be reduced by effective social marketing of pathway improvements (pathway signage, media campaigns, school site publicity, direct promotion to parents, etc.).

Cost effectiveness of such interventions likely will be greater in school zones, where risk of trafficrelated injury is greater.30 Recent studies suggest that children are more likely to enjoy walking if traffic is reduced and if their neighborhood is green31 (the shady comfort and aesthetic effect of trees). Designing pathways to meet safety and “green” criteria may therefore increase playful pathway use by children, simultaneously decreasing school-related traffic, associated risk of injury, and the school’s carbon footprint. The multiple benefits of building safe, convenient, playful pathways in school zones will also increase physical activity and help parents feel more secure about their child’s safety. This same rationale could well be used to support playful pathways in neighborhood “park zones” to increase safe access.

Contact with nature u

Because of their linear form, playful pathways offer children opportunities for engaging with nature in a special kind of way to enjoy the many benefits well documented in the scientific literature.32

But quality natural play spaces are generally unavailable to today’s urban and suburban children and youth. Fortunately, there is a growing movement to connect children with nature launched with the publication of Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods 33 Currently, the movement has spawned more than 60 state and regional coalitions, passage of proclamations, executive orders, and legislation, and publication of numerous articles.34

Much of this activity demonstrates a demand for practical solutions to create close-at-hand natural play areas for children. For example, the strategic plan launched by the Maryland Partnership for Children in Nature, developed at the state governor’s request, calls for natural play areas in all communities in Maryland.35 A similar call is included in an executive order issued by the governor of Kansas.36

Connecting meaningful childhood destinations u

Growing research evidence supports an agenda promoting playful pathways interlinking home with play destinations and other meaningful childhood places such as schools, parks, playgrounds, sports facilities, community recreation centers, and local stores.37 Underscoring the importance of neighborhood destination connectivity for children, a recent study from Canada demonstrated that children living within a kilometer of parks containing playgrounds were five times more likely to have a healthy weight than children without a playground nearby.38

Other studies have shown that parks with paved trails are more likely to be used for physical activity by adults.39 These findings suggest that combinations of playgrounds and paved pathways are more likely to create healthy, fun filled, family-friendly active environments that will increase social interaction and therefore social capital, as well as provide destinations that connect people to nature.

Because they provide for routine, direct experience of nature close to home, greenways also enhance connectivity between people and nature—typically more so than other forms of greenspace—because of their linearity, high ratio of edge to interior area, and thus greater accessibility. This, of course, creates opportunities for recreation and the experience of aesthetic beauty, but also can have a more profound significance because bringing nature into people’s daily lives influences how they think about and experience their home environment.

Paul Hellmund and Daniel Smith40

u

Attracting adults (and accompanying children)

Although research on the use of pathways by children is limited, a number of studies related to pathway use by adults offer implications for children as well.41 We know that pathway characteristics that lead to higher use by adults include access to meaningful destinations, residence in shared-use neighborhoods, and pathways with mixed and open views –characteristics closely aligned to “prospect and refuge,” which children also enjoy. Incorporating these features, or locating new pathways with these features in mind, would encourage parental use and therefore would increase use by accompanying children.

As part of the new walking and biking infrastructures of cities and suburbs, pathways offer children independent mobility, playful exploration, discovery, learning, and enjoyment. Through play, which research has shown to be essential to healthy child development, children can experience and learn about the world around them on their own terms, in their own time and space, without the sometimes limiting presence of adults. However, studies have also shown that appreciation of environments can be deepened for the child in the company of a knowledgeable, caring adult with patience enough to move at a child’s pace, allowing time for leisurely investigation and discussion.

Connecting meaningful destinations such as playgrounds and parks is an important function of playful pathways. Residents of all ages can walk or bike to the park and explore its natural settings. Parents and children can play together in a space that is accessible to all.

If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder without any such gift from the fairies, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in.

Rachel Carson42

8 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Supporting Research

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Supporting Research 9

Independent mobility, away from traffic danger, is an essential factor in middle childhood, supporting a sense of autonomy and self-efficacy, enabling children to fully engage with their friends and community.

The benefits of playful pathway systems implied by the preceding research review suggest that playful systems offer benefits to children and families that may not be achieved by another means.

Multiple benefits include:

Extending play value

Extending the types of play (especially in the physical and socio-dramatic domain) afforded by a continuous, complex, linear space where nature is omnipresent.

Enabling health promotion

Enabling kids and families to get outdoors, enjoy the fresh air, and experience meaningful physical activity on foot, bicycle, or wheeled toys.

Expanding inclusion

Expanding possibilities for people of all abilities, ages, and backgrounds to engage in playful interactions with each other and their surroundings, which continuously afford play opportunities as children and other users move along.

Engaging with nature

Providing a multitude of opportunities for interacting playfully with a wide diversity of plants and animals through the seasons.

Two best friends head home on a traffic-free greenway, carrying soccer balls after an energetic game in the park. The curvy, undulating greenway tread is bordered by park no-mow zones, which add the sensory stimulation of native flowering plants and diverse insect life.

Reinforcing environmental literacy

Benefiting from the learning opportunities afforded by pathways integrated with a “green infrastructure” of stream and river corridors and vegetation patches,43 transecting local habitats, exposing natural and sociocultural history of former land uses.

Walkable, bikeable community connectivity

Encouraging nonmotorized travel from home to local recreational and cultural destinations, thereby reducing both traffic and the carbon footprint.

Growing community social capital

Bringing residents together through shared lifestyle experiences focused on children and a sense of building healthy communities together.

10 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways 11

Extending play value

Play value is what children find by “reading” the play affordances of a play environment. If pathways offer play affordances at every step along the way, children will be motivated to keep moving –reinforced by play pockets at regular intervals. Playful pathway networks have the potential to spread play value through the neighborhood and beyond. Increased diversity of play value may support several developmental domains and increase inclusiveness by attracting a broader range of multi-age users than a conventional clustered playground.

Learning cognitive skills

The “richness and novelty” of being outdoors stimulates brain development.44 Research shows that direct, ongoing experiences with nature in relatively familiar settings remains a vital source for children’s physical, emotional, and intellectual development.45 Play creates a synergy between these outcomes in a process that helps children acquire an understanding of the world and how it works. The resulting cognitive skills grow and develop day by day as children continue to explore and discover phenomena in their expanding territorial range.

Building self-esteem

Children who spend time playing outside are more likely to take risks, seek adventure, develop self-confidence, and respect the value of nature.46 Outdoor recreation experiences like camping can improve children’s self-esteem.47 Children’s experience of green spaces outside the home can increase concentration, inhibit impulses, and improve self-discipline.48

“Self-efficacy” or “agency” describe the sense of being able to act on one’s environment and being in control of one’s own destiny. For children this means being able to take healthy risks, go on adventures, and solve problems by manipulating physical environments – preferably with others, to achieve a shared sense of accomplishment. Agency stimulates motivation, supports self-esteem and psychological health –the feeling of being in control of self and external events.49

Integrating the senses

Sensory integration, which is supported by children’s experience in multi-sensory rich environments, is critical to healthy child development. As sensory integration pioneer Jean Ayers says, “Intelligence is, in large part, the product of interaction with the environment.”50

u

Learning to live together

Pathway linear forms allow children to “go on adventures” together in their local area. Children can imagine they are explorers on a quest or safari. They love interesting terrain with natural objects to look at and clamber over. A small backpack can be used to hold interesting items gathered along the way. Family members can script an adventure together with masks and treasure maps, assign roles (actors, director) and film a movie “on location” as the pathway drama unfolds. Dramatic play scenarios facilitate collaboration as a group, enhance social skills, support emotional development, offer practice in working together to solve problems, and provide children a sense of collective achievement reinforcing self-esteem and competence in managing their own affairs.

As part of the pathway adventure, “hideouts” or “clubhouses” (provided by design or built by children themselves) offer space for rest and relaxation, play experiences with children from different families, and interaction with surrounding life forms. Opportunities to build these types of socio-emotional skills are essential to healthy, balanced development of individuals and sow the seeds for harmonious adulthoods that rise above differences in culture, religion, and ethnic origin.

Imagining a new world

At a time when creativity of American children is in decline, the need has never been greater to develop imagination and creativity, which are regarded as primary economic drivers in today’s rapidly changing world.51 Hannah Arendt evokes the fundamental need for each new generation to re-invent the inherited world to ensure that cultural evolution is relevant to the pace of change now facing global society.52

12 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways 13

u u u

u

Enabling health promotion

PathwaysforPlay is offered as a resource to professionals and community advocates as a health promotion strategy for children, youth, and families, to counteract declining levels of children’s time outdoors and the negative health consequences for society. Over time, the health value will accrue to the whole community with multiple long-term benefits. Children’s health is declining because of poor diet and sedentary lifestyles. However, the CDC emphasis on daily physical activity means that the environment beyond school must be included in strategies to support children’s active lifestyles when not in school (the majority of time).

Health promotion is possible through the creation of networks of shared-use playful pathways connecting residential neighborhoods to destinations that are meaningful to children and families. At the same time, playful pathways expand the possibilities for inclusion of all members of the community and their healthy engagement with nature.

Increasing daily physical activity. An advantage of playful pathways is that their linear form is likely to support sustained moderate to vigorous activity by affording longer spans of movement and running opportunities on the pathway treads as compared to conventional playgrounds. This may highlight pathways themselves as important play destinations (as well as leading to appealing destinations such as playgrounds and parks).53

The creation of Safe Routes to School programs such as the “walking school bus”54 have achieved success but are often limited by the geography of homes in relation to school locations. In recognizing the constraints of school-based health strategies, groups of families are discovering that children can be attracted outdoors if it is fun – especially in natural settings where real adventures can happen. Groups across the country have organized themselves to spend playful times together at weekends, typically using local parks, playgrounds, trails, and greenways.55 The ShapeoftheNation report contains key guidelines for children and adolescents that list aerobic, muscle-strengthening, bone strengthening activities, appropriate by age,56 which can be designed into pathway play pockets.

u u Improving attention functioning. Spending time outdoors increases “involuntary attention,”57 which may be why time outdoors can also reduce the severity of ADHD symptoms in children.58 Even short walks in urban parks can increase concentration and lessen other ADHD related symptoms.59

Reducing stress and aggression. Time spent in green spaces, including parks, play areas, and gardens reduces stress and mental fatigue.60 Children who were exposed to greener environments in a public housing area exhibited less aggression and violence.61 Even a green view through a window reduces stress, increases level of interest and attention, and decreases feelings of fear and anger or aggression.62

Expanding inclusion

In recent years, children’s outdoor play territories have become highly restricted, mainly because of parental fear of social harm (perceptions that do not match the reality of reduced outdoor crime in recent years) and the real dangers of automobile traffic. This means that children’s play places such as playgrounds and pathways must be comfortable and attractive to adults, including grandparents, parents, and other family members. Playful pathways can be designed to attract and accommodate all age groups through access, location, form, and content of the pathway environment. Successful play environments are also inclusive of individuals from diverse cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds across broad socio-economic spectra.

Engaging nature

Increasing daily physical activity can be achieved easily when playful pathways are integrated into children’s neighborhoods. At the same time, research shows that being outdoors in natural surroundings can reduce stress and aggression among young people.

Play opportunities provide value to children and caregivers with disabilities by ensuring both physical and social access, while meeting Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements. However, there are many other “special needs” to be considered, including the needs of children with autism or grandparents with onset dementia. For children and adults using wheelchairs and other forms of adaptive equipment, playful pathway designs can offer easily navigated, inclusive play environments that satisfy universal design principles while extending opportunities for playful interaction afforded by a linear, “wheelable” environment.

The basic truth is that play in nature is good for children. Playful pathways provide a movement channel to draw children into and through natural surroundings such as stream corridors, which offer multiple opportunities to playfully enjoy natural surroundings. Access to sticks, stones, and a multitude of other natural loose parts like pine cones amplify play opportunities, including socio-dramatic play, social interaction, and cognitive stimulation. Pathway themes can spin off into unscripted children’s games if natural loose parts are available.

Inclusion is a distinct function of playful pathways, which can be located and designed to attract a broad range of users: individuals with special needs, older family members, children of all ages (strollers included), and users from diverse cultural backgrounds - all able to enjoy adjacent natrue.

14 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways

u

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways 15

Reinforcing environmental literacy

Playful pathways facilitate access to environments and ecosystems that may otherwise be closed to children and families.

Multiple learning opportunities may be activated during informal play, through pathway excursions as part of school curricular experiences, recreation programming, or during family trips. The linearity of playful pathway networks offers children close proximity and “continuous experience” of nature that may not be possible in rectilinear park space.

Playful pathways offer the potential for children to learn both through and about the natural world as the first essential steps towards caring for it. When connected to schools and nonformal institutions such as children’s museums, nature centers, and botanical gardens, pathways offer educators new opportunities to integrate environmental literacy across the curriculum. Experience of playful pathways may help the next generation to acquire strong environmental values that will redirect human culture in a more sustainable direction.

Research demonstrates that early experiences of nature provide long term memories and a positive disposition towards the natural world. Playful pathways have an important biophilic role as they are more likely to be located in places that offer children play experiences with natural materials.65

Childhood contact with nature contributes to shaping a lasting environmental ethic and an interest in environmental professions.63 Environmental education and scouting programs during the teen years also contribute to an ethic of environmental stewardship.64 Edward O. Wilson, eminent Harvard biologist, world expert on ants, and prolific writer about nature and society, coined the concept of biophilia, which assumes that people are born with a positive disposition towards the natural world – not surprising as we are entirely dependent on it.

Opportunities to spend substantial amounts of time in a given location allow for the discovery of meaningful components of the landscape and the development of an emotional attachment to that place. For many people, landscapes that are readily accessible are those that are near to their home; these places seldom fit the image of wild nature associated with traditional environmental education.

Paul Hellmund and Daniel Smith66

Reinforcing environmental literacy is offered in a multitude of ways by playful pathways, here sister and brother have walked the town trail down to the river to fish and play along the banks of the shallow mountain stream. Such experiences extend eco-knowledge gained at school and provide enrichment to share with classmates and teachers.

Walkable, bikeable community connectivity

Society is at a point in history where new thinking about the connection between neighborhood development and healthy child development is imperative. Childhood sedentary lifestyles are resulting in new, extreme public health challenges. The highly successful pattern of private autodependent suburban development that has dominated the real estate industry since the late 1940s is now recognized as unsustainable in terms of energy demands, resource consumption, and human health.67

More compact development options have been the response, many with historical urban precedents, their health benefits supported by “active living research.”68 Playful pathway networks need to be recognized as part of this new urban livability model. Running outdoors, children must find safe, playful pathways connecting them to a diverse world of friends and meaningful play destinations.

Pathway networks may contain a variety of components such as sidewalks, alleyways, pedestrian crossings, greenways, urban trails, nature trails, promenades, in-park trail systems, and educational campus/schoolground trails. The over-riding criterion is connectivity, which can ensure safe pathways for spontaneous outdoor play,

integrated with a network of places that are both compelling and meaningful to children and families.

In TheOptionofUrbanism,69 Christopher Leinberger argues that reversing the model of car-dependent suburbs is producing “reverse families,” including empty nest grandparents wanting to combine the cultural offerings of urban life and closeness of the extended family. By choosing to move around more on foot and bicycle they have more time for each other because less time is spent on driving. These new walkable/bikeable neighborhoods provide environments where families can grow in place, where children have friends close by, where adolescents do not have to rely on parents to drive them to “cool places” to hang out with their friends.70 As a strategic component of “walkable urbanism,” pathway infrastructures support progress towards cities as healthy habitats for children and families – as well as supporting long term, sustainable increase in property values.71

Timing for creating walkable, bikeable childhoods could not be better. Play can be infused in pathway development by retrofitting existing pathways and by creating new independent mobility routes for children and families, especially Safe Routes to School.72

Growing community social capital

Playful pathways provide opportunities for local groups to organize family nature explorations, which are growing in popularity across the country.73 Playful pathways provide a great way for community members of all ages to share time and place together, to get to know each other, to become more informed on local issues, and to contemplate collective action to improve children’s outdoor environments. Local pathways such as greenways, waterfront esplanades, and rail-to-trail facilities may provide an important aspect of local identity, sometimes with deep historic meaning, for example the American Tobacco Trail in Durham, North Carolina.74 As pathways become valued social places, repeat visits may become more likely, resulting in children spending more time playing outdoors. As residents feel a sense of ownership, they may be more likely to invest in further infrastructure improvements.

Growing community social capital can be stimulated when playful pathways connect neighborhoods to local destinations such as parks that attract a mix of residents who can hang out and get to know each other.

16 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Benefits of Playful Pathways 17

This family walked to the Kids Together Playground along the Hinshaw Greenway to celebrate a birthday, which are such popular events that all the usual locations were occupied. Nonetheless, the group still enjoys a gathering spot on one of the playground’s internal pathways.

* http://www.sjparks.org/Trails/TrailCount.asp

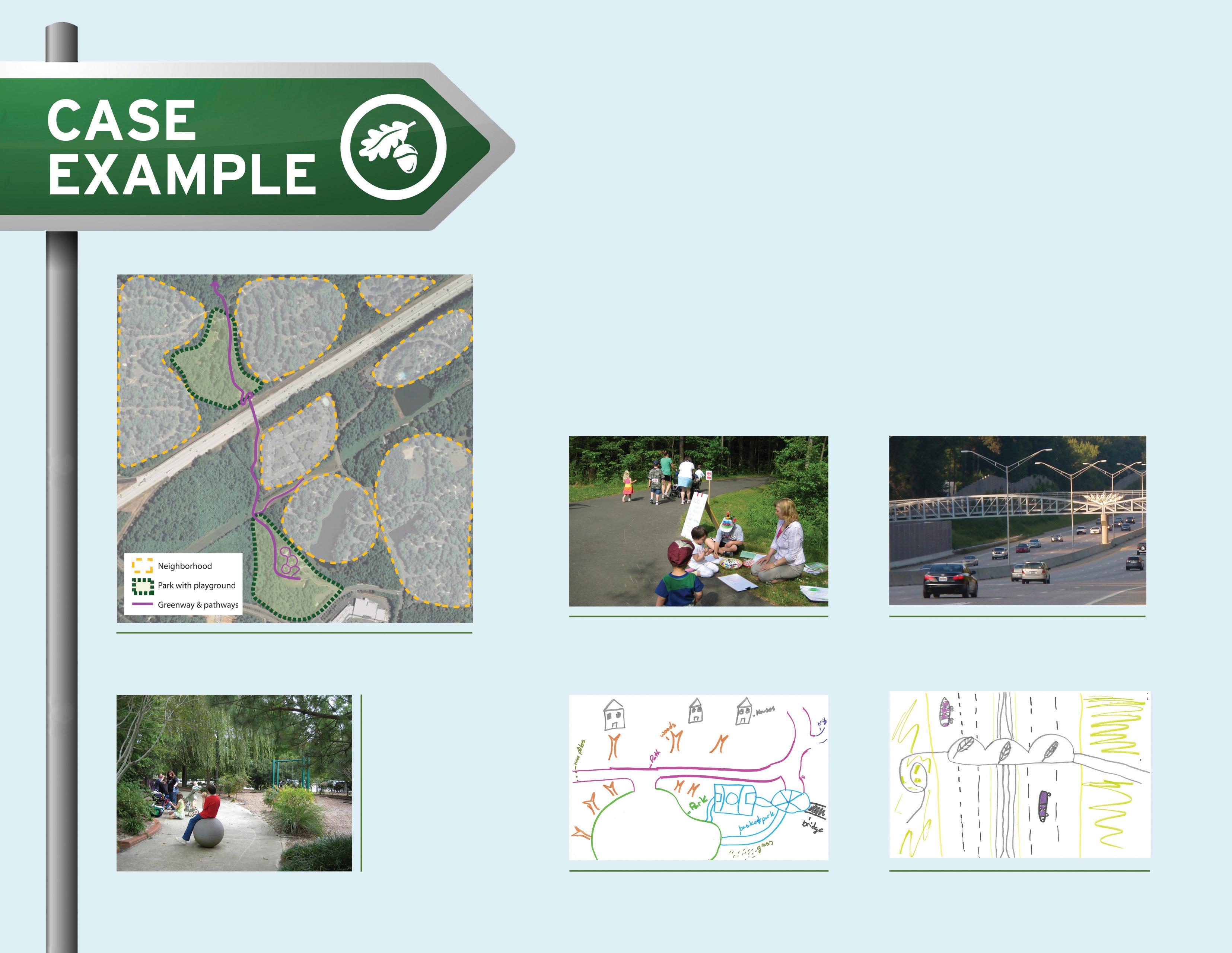

Hinshaw Greenway

CARY, NORTH CAROLINA - USA

The town of Cary, NC, greenway system links neighborhoods to parks and other important destinations. Residents report that this popular pathway system is well maintained and appreciated. The paved Hinshaw Greenway is a 1.66 mile segment that connects two parks across a busy freeway in the midst of residential neighborhoods. A group of volunteers conduct periodic user counts across the greenway system, walking the pathways and recording data such as the number, approximate age, gender, and groupings of users. Data indicates a higher proportion of child pathway users than reported elsewhere in the literature. The data gatherers also noted needed repairs and other issues requiring attention. User counts are an excellent way to calibrate pathway use, thus building evidence to support pathway development. San Jose, CA, has successfully used volunteer trail count data to secure grants for additional trail funding.*

A pilot study conducted by the Natural Learning Initiative investigated why children and families are drawn to the Hinshaw Greenway. Access to parks with attractive, well maintained playgrounds (meaningful destinations) was a major motivation. Linkage to a neighborhood gas station where children could go for refreshments was an added benefit. Adult users reported using the pathway for exercise, dog walking, and relaxation, (mentioned by children as well); however, the destinations were more often mentioned by children as their primary purpose for pathway use.

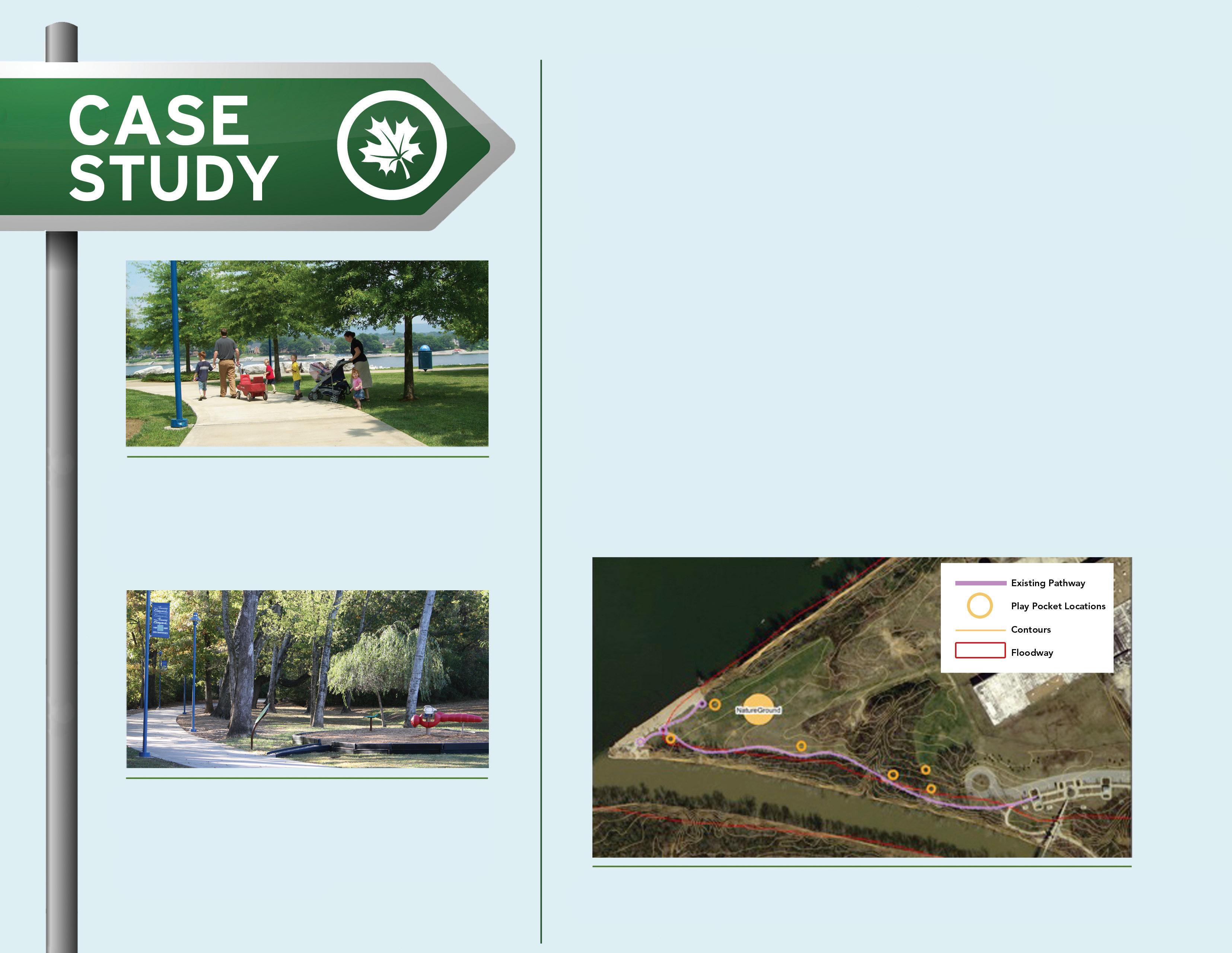

Hinshaw Greenway pilot study station where children are being asked to draw pictures of the pathway in order to understand what they found meaningful.

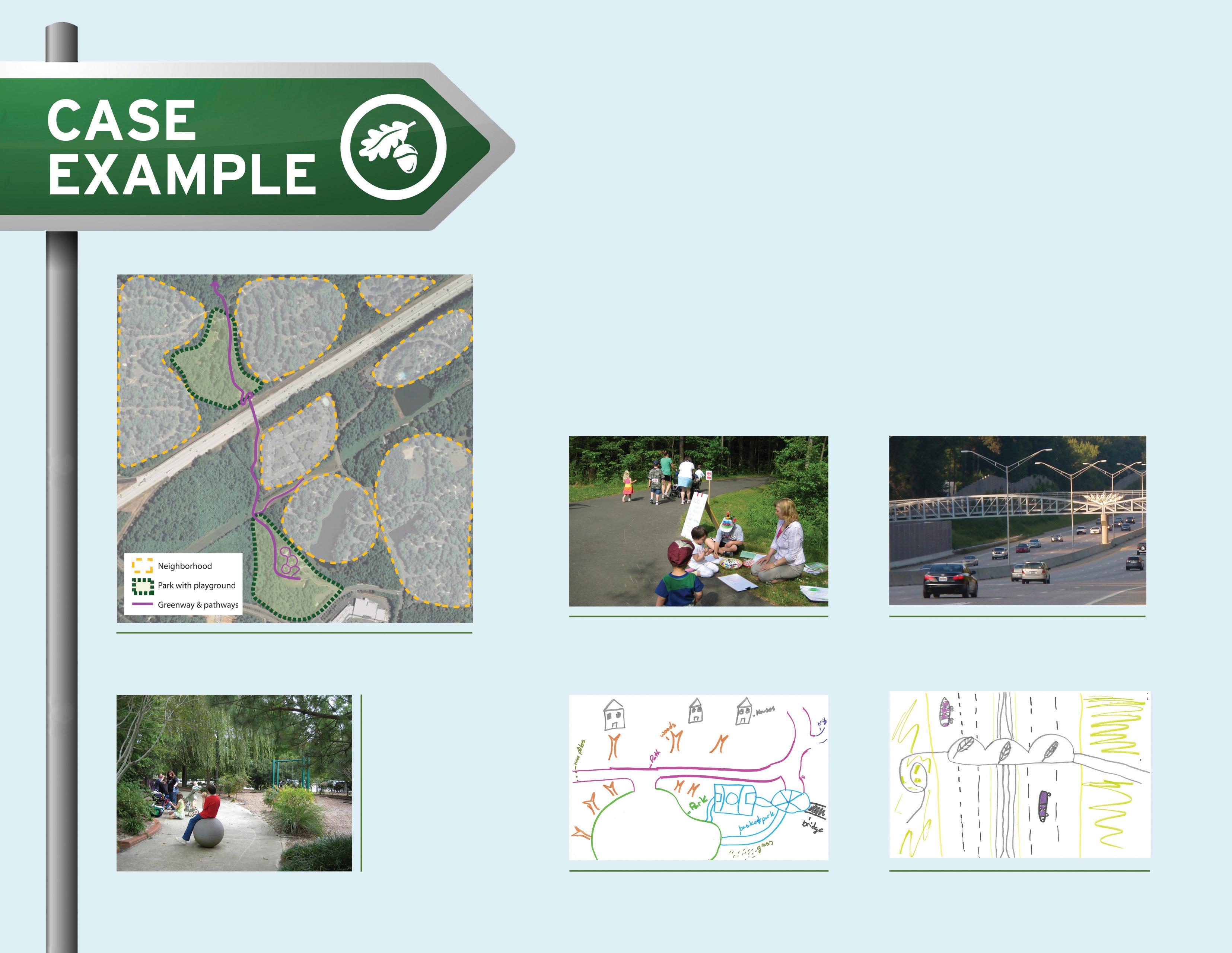

Pedestrian bridge spanning the eight-lane freeway, bejeweled with easily identifiable artwork.

This drawing shows how the Hinshaw Greenway connects children’s neighborhoods to parks and playgrounds.

The bridge and artwork was represented in nearly every child’s drawing. The bridge crossing offers children the thrill of feeling the rush of freeway traffic below.

Infusing play into pathways

Pathways for Play provides a new, linear form of play environment different to the typical clustered playground of manufactured play equipment. The linear form makes it easier to include play pockets and to mix specially designed, commercially manufactured components with natural elements to encourage discovery and continuous movement. Additional play pockets may be added periodically as funds become available over time or as the pathway is extended in length. This approach makes phased development easier. The linear form can be adapted to linear sites such as creek corridors and rail trails. Based on research from Kids Together Park, Cary, NC,75 playful pathway forms may be adapted to large parks, botanical gardens, and arboreta, to make them more attractive to family groups because strolling adults can exercise, enjoy the surroundings, and engage in conversation while children play.

18 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Case Example

The Hinshaw Greenway links neighborhoods and parks on both sides of a freeway.

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Infusing Play into Pathways 19

Playing along the way

Research by the Natural Learning Initiative suggests that curving pathway alignments with secondary loops off the main pathway may more likely motivate pedestrian use76 as well as stimulate more intense physical activity by children.77 Pathways have a temporal dimension. Like musical scores, pathways are “played” by users. Adventurous adults as much as playful children enjoy linear recreational experiences because anticipatory perception keeps the mind alert – even more so if the trail rises and falls as well as curves.

Playful pathways provide a trajectory through threedimensional space, enjoyable by all family members. The smaller and more intimate the scale, the more enjoyable by children. Since urban pathways typically follow a smooth, relatively flat grade, they are easily accessible to people using mobility devices, enabling them to participate naturally in play activity.

“Looping pathways are your best friend,” says prominent greenway designer, Chuck Flink. They tend to offer the most satisfying pathway experience for users in general and kids in particular, because looping forms integrate continuity and scale, and provide a choice of distance ahead of time. Users may more likely be motivated to make a return trip in the opposite direction.

Children’s spontaneous, independent play requires interaction with intimate, diverse physical surroundings to fully activate the type of social interaction that is such an essential characteristic of play. Spontaneous play has a particular tempo linked to the scale of children’s immediate surroundings. Play spaces need to be small enough in scale to afford continuous interaction. If linear spaces are too large with insufficient diversity, they will not hold children’s attention. Several key factors can support the infusion of play into pathways.

u u

Meaningful destinations

Pathways connecting places where children (including organized school and youth groups) want to go, such as playgrounds and parks, will attract higher levels of use.

Sinuosity or curves

A measurable, positive factor stimulating interest for children. Curvy tread alignments can reduce pathway scale and provide a sense of exploration and intrigue for children who anticipate adventures that await them “around the next corner” as they move through a constantly shifting visual field. This type of temporal, progressive disclosure, so well understood by Japanese garden designers, makes the small seem larger than it is by packing diversity into a small space but in an ordered manner so that choices are presented sequentially. City parks retrofitted with curvy, playful pathways could offer increased play value and ensure that the repertoire of play experiences is not fully disclosed within moments of arriving. Children have to “work” to discover the play value along the way.

Infusion of play into pathways can be achieved in a multitude of ways. Here a play pocket maze offset from the primary pathway was created with small scale, looping lines of evergreen shrubs and treads. Short, intimate loops surfaced with sections of tree grate add innovative play value.

Historical/cultural features

Historical and cultural features can offer cultural identity and educational value for children, helping them understand where they live and to appreciate their cultural roots.

Built features such as tunnels, bridges, and overpasses may reinforce place identity, increase visual interest, and encourage movement and a sense of adventure. Landscape design can reflect local natural history by using plants that may have special significance; for example, tree species that represent forest industry or fruit trees that reflect agricultural production and could be managed by 4-H youth groups. Stonework could be quarried locally. Pathway artifacts such as bridges may reflect local history.

Cultural artifacts could reinforce local racial/ethnic traditions (Native American/Inuit, Hispanic, African American, and a multitude of Asian and European cultural expressions). Pathway experiences could be enriched by art works, including “earth art” and “playful art.”

Natural features

Natural features can add fascination, mystery, intrigue, and educational value for children. Rock formations/outcroppings, special landscape views, historic or specimen trees, wetlands, and other unique habitats may influence pathway layout and add physical identity and meaning to the pathway corridor.

Built features

Play elements, tunnels, bridges, overpasses, etc., will affect visual interest of the corridor while encouraging continuous movement, adventure, and a sense of place.

Cultural features integrated with playful pathways can offer intriguing diversions for all ages. In this example, a large scale sculpture offers a playful diversion for young users of this “art park” trail.

20 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Infusing Play into Pathways

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Infusing Play into Pathways 21

u u u

FAMILY FUN

and adequate visibility can be achieved through careful site layout, equipment selection, and naturalization strategies.

PLAY POCKETS

are the primary means for infusing linear PLAY VALUE into pathways by intentionally designing them to stimulate play through a sense of adventure, exploration, and discovery for the whole family in nature.

LEARNING

can be promoted through visible adventure and exploration in nature. Developmental considerations should be addressed through play pocket designs, educational signage, and playful activities.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

can be achieved through innovative play pockets that engage the whole family while encouraging them to continue moving to explore the next discovery.

Planning Play Pockets: Ten critical considerations

Spacing - Are play pockets spaced at appropriate distances apart (5 to 10 minutes or approximately 300 to 500 feet) to encourage movement and discovery?

Setback - Are play pockets alternated and set back from the main pathway sufficiently to minimize conflicts with fast-moving bicycles?

Play value Have a variety of play elements been included to afford for children many types and forms of play (physical, social, emotional, cognitive, etc.)?

Loose parts and sensory stimulation Have surrounding plants been selected to provide natural loose parts to support children’s socio-dramatic play and discovery along the way? Have the play equipment, artifacts, and adjacent plantings been selected to maximize sensory stimulation of users of different abilities?

Learning - Does family-friendly signage promote play and extend learning in meaningful ways?

Usability Are play pockets designed to accommodate children and families of different ages and abilities in meaningful activities?

Caregiver comfort - Are play pockets shady with ample, comfortable seating for two or three family groups to relax and supervise while children play?

Amenities Have appropriate amenities (bike racks, seating, trash receptacles, drinking fountains, etc.) been considered to offer additional affordances for play so that families play longer and return often?

Safety - Does the play pocket equipment and safety surface in use zones meet American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) / Consumer Protection Safety Commission (CPSC) standards and guidelines? Are the pockets visible for supervision and easily maintained?

Naturalization and tree protection - Is the existing and/or installed landscape outside of use zones but as close as possible, so users feel immersed in nature? Are play pocket installations far enough away from the root zones of existing mature trees?

Sinuous playful pathway

Play pockets distributed at regular intervals along specified corridor section with defined entry and destination play pockets. Suitable for many contexts where right-of-way is sufficiently wide and visitorship justifies investment. Play pockets offer a potential upgrade of existing greeway.

Crisscross loop with rail-to-trail playful pathway

Secondary trail with play pockets added to specified corridor section. Suitable where right-of-way width allows (former siding, for example) and family visitorship justifies investment. Play pockets offer a potential upgrade of existing rail-to-trail greenway.

Cul-de-sac playful pathway

Playful pathway and play pockets created as a stand-alone project. Potential development on municipal, county, state, or federal parkland. Major destination required to assure users reach the end.

Subsidiary loop provides choice of shorter length.

Single looped playful pathway

Playful pathway and play pockets created as a stand-alone project. Potential development on municipal, county, state, or federal parkland – especially as a peripheral trail located in an urban park or school grounds. Closed loop assures users that they will return to entry.

Play pocket spur off-set

Play pocket is off-set (10 to 20 feet) from primary pathway tread, on a spur surrounded by buffer planting located so sightlines are not obscured. Seating and shade trees make the play pocket a comfortable resting spot for all users with potential for added site amenities such as picnic table, trash receptacle, and emergency call box.

Play pocket loop off-set

Play pocket is off-set (10 to 20 feet) from primary pathway tread, on a short loop buffered by planting located so sightlines are not obscured. Seating and shade trees make the play pocket a comfortable resting spot for all users with potential for added site amenities. A secondary playful pathway may be connected to other areas of discovery.

Pathway intersection node

Crossing of secondary and primary playful pathways creates a potential gathering and resting spot for all users to enjoy site amenities such as seating, picnic table, shade trees, trash receptacle, and emergency call box.

Multi-looped playful pathway

Playful pathway and play pockets created as a stand-alone elaborate project. Potential development on municipal, county, state, or federal parkland. Closed loop assures users that they will return to entry. Subsidiary loops provide choice of length and potential for repeat visits as children age and increase desire to explore further.

Compact looped playful pathway

Playful pathway and play pockets created as a stand-alone project where space is limited. Potential development on municipal, county, state, or federal parkland –especially in an urban park or school grounds, possibly around a central multipurpose field. Closed loop assures users that they will return to entry. Single loop is feasible length for children’s use.

Water body playful pathway

Playful pathway loop and play pockets created around a moderate sized water body (not so large as to deter use by families). Potential development on municipal, county, state or federal parkland. Closed loop form assures users that they will return to entry. Play value is enhanced by potential access to water and aquatic wildlife.

Flower playful pathway

Playful pathway and play pockets created as several mini-loops returning to a central destination where caregivers can relax yet keep an eye on things. Especially suited to the needs of early childhood or mixed age groups. Potential development on municipal, county, state, or federal parkland. Suitable for multi-theme or inter-linked theme development.

Primary trail

Secondary trail

Textural change in pathway surface

Corridor vegetation Seating

Creekside playful pathway

Secondary trail with play pockets created in specified corridor section, shown here on the bank opposite a greenway or major trail. Suitable where stream corridor width and FEMA floodway allows, and family visitorship justifies investment. Potential development on municipal, county, state or federal parkland. Play value is enhanced by potential access to water and aquatic wildlife.

Low plantings

Play pocket Water Parking and bathroom

22 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Site Specific Design Considerations

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Site Specific Design Considerations 23

Linear forms – may be more suitable for cyclists and can be made more interesting with installation of frequent play pockets.

Climatic region – offers educational potential. Temperature and rainfall affect diversity of plant and animal species.

Form Location Access Assessing playful pathway potential

Modal mix – increases accessibility. Is the pathway corridor accessible by foot and bike from users’ homes or is motorized transportation required to get to the “trail head”?

When infusing play into an existing or planned pathway, consider the context and variables that may affect the eventual play outcome.

Curving forms – make the pathway experience inherently more exploratory and stimulating to children because of the anticipatory excitement. Play pockets provide additional adventure.

Looping forms – add further interest by ensuring that users do not need to turn around and return by the same way they came. Disruptive, “when are we going back?” questions are avoided. Using play pockets in both directions encourages repeat visits.

Playful, curvy, sinuous pathways can be created in many forms, especially in urban contexts where the designer has a blank slate to work with. In this example, carefully selected rocks combined with a diversity of multi-textured horizontal plants lapping over the pathway tread offer a rich sensory interest for all ages. Larger trees set back from the tread provide a sense of enclosure but good visibility and visual separation from the urban surroundings.

Physiographic region – offers educational potential. Geology, soils, and topography affect corridor shape and tread width.

Urban/rural context – affects number of potential users in large, medium, or small metropolitan areas; in rural townships; and in open country.

Institutional context – offers benefits and constraints of contexts such as neighborhood park, botanical garden, nature center, and schoolground.

Corridor length – may affect perception of pathway as being too long to use or short enough to be easily usable. How long is the pathway?

Connectivity – can provide more options for young users as their play range expands, thereby encouraging them to retain user interest. How many meaningful destinations are connected?

Continuity – affects potential for safe exploration by protecting users from traffic and provides access to more play opportunities. Can the pathway be traveled without interruptions such as street crossings or grade changes?

Climatic and physiographic regions offer particular educational potentials and influences on pathway design according to local geology, rainfall, plant species, etc. Seasonal cycles may offer particularly attractive opportunities, as illustrated here. Connectivity and continuity are key requirements for infusing play into pathways. Meaningful places (greenway, school, park, and market) are connected to home base and friends’ homes. In the suburban layout illustrated here, cul-de-sacs (children’s safe havens) are connected to a community greenway. The Safe Route to School for the child in the yellow house includes sections of sidewalk and greenway, and spur to the school.

Tread slope, surface and width –will affect level of use, type of use, user group, and extent to which universal design criteria may be met. For example, a narrow tread could limit three individuals from being able to walk abreast, easily able to converse or groups of children being able to play together. A rough uneven surface may limit use by older adults using mobility devices. A steep grade would limit use by wheelchair users.78

Tread slope, surface, and width affect type and level of use, user group, and universal design effectiveness. Illustrated here, the broad, ten-footwide, gently sloping, asphalt-surfaced tread offers high capacity for diverse groups, including parents with strollers and individuals with special mobility needs. In this example, the adjacent residential internal sidewalk connects directly to the greenway, which connects to local parks (meaningful destinations) in both directions.

Separation from traffic – may affect both the perception of safety and actual protection from injury from motorized traffic.

Neighborhood context – may affect perception of crime and therefore level of use. Actual occurrence of crime may be quite different but that is not what potential users usually “read.” Abandoned buildings, neglected parks, potholed, and littered streets may deter use. Citizen patrols may increase feelings of security.

Level of maintenance – may affect perception of neglect and therefore level of use. A well-maintained, clean environment may encourage increased use.

Visibility – may make users feel more comfortable. Caregiver psychological comfort needs to be weighed against children’s desire to feel that they are in their own special place in an enclosed portion of the pathway invisible from outside. Site lines and vegetation management are important considerations for promoting safety.

Having crossed the narrow, low traffic internal residential street, this family “on wheels” continues in safety along the Rails-to-Trails Greenway.

Usability Safety Jurisdiction

Public pathways – may be affected by different regulations covering pathway installations at municipal, county, state, or federal levels of jurisdiction. For playful pathways installed in stream corridors, typically FEMA floodway regulations will limit the location of design elements allowed above ground level. Local floodplain regulations may further influence design decisions.

Private pathways – may be affected similarly by regulations, which still may apply to installations on private land or land held by nonprofit organizations. Use charges or membership requirements may apply.

Jurisdiction can be an important consideration when creating play pockets along a playful pathway. In this example, where the pathway follows a stream corridor, FEMA regulations defining the floodway could be an important factor potentially limiting installation of artifacts that would inhibit the flow of floodwaters.

24 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Infusing Play into Pathways

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Infusing Play into Pathways 25

Riverpoint Park is located on a former industrial site that overlooks the picturesque Tennessee River. It is a prominent destination for downtown cyclists and walkers, school groups, families, and individuals seeking an urban park experience for relaxation or exercise. A portion of the site is wooded. Large areas remain in turfgrass.

shady play pocket location in the forest brings play in to nature. The pocket is separated from the main pathway by a short distance which, in the future, could be landscaped with low growing vegetation to enhance visual appeal, create a physical buffer, and to provide loose parts for play.

Riverpoint Park

TENNESSEE RIVERPARK, CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE - USA

Chattanooga’s unique riverfront story has been recognized internationally as a series of successful public and private endeavors have helped create new national attractions, inspiring riverfront parks, new retail, restaurants and housing linked by a delightful riverfront park and trail system. Investments in outdoor recreation continue to foster pride from local residents, reconnecting members of the community with nature, while fueling economic development.

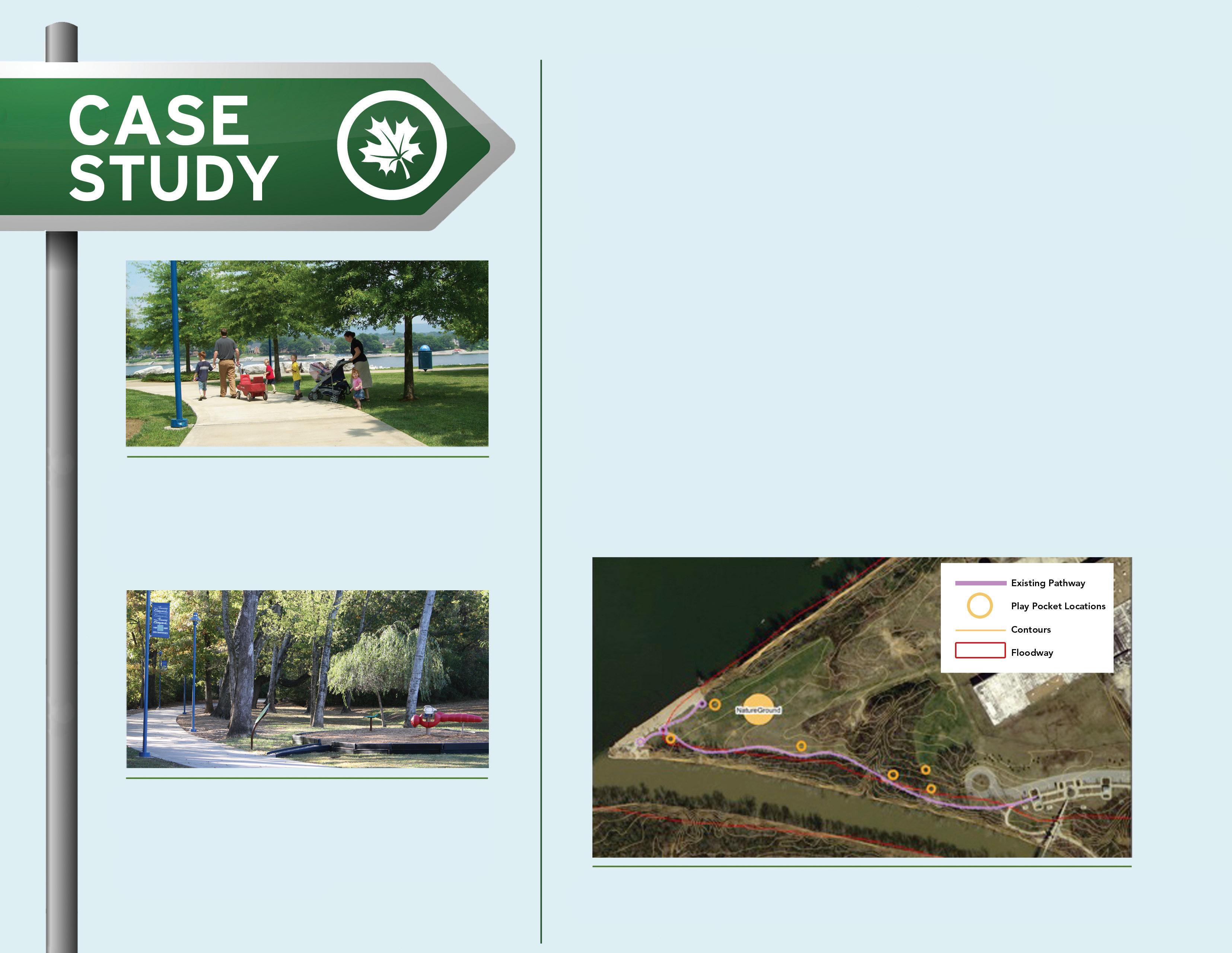

The City of Chattanooga and Hamilton County are dedicated to creating a family-friendly environment with play opportunities for children and decided to develop playful pockets along the existing South Chickamauga Creek Trail. Potential play pockets were initially located (gold circles below) using Geographic Information System (GIS) software with input from the Parks and Recreation Departments, which then produced a base for the final masterplan (right).

The final master plan shows proposed play pocket locations (numbered gold patches) chosen according to best practice guidelines and site constraints. Play pockets clustered near the pathway entrance take advantage of the environmental education value of the woodland setting, which also provides shade.

A large area of the park was recommended for reforestation (dark green). Chattanooga and Hamilton County, like many communities, are concerned about reducing their carbon footprints. Facilitating a return to a natural state promotes this policy by decreasing energy consuming turfgrass maintenance and adding carbon sequestration with the increase in trees.

Final master plan includes a major looping pathway, instead of the previous dead-end. Secondary pathways were added to provide circulation options for children moving between play pockets and future playground.

Signage provides families fun facts about the natural world while encouraging playful activities within the play pocket.

“We were so excited when we discovered the addition of play equipment and activities to do along the path. Our four lively children all found something to enjoy that matched their developmental levels. Riverpoint was already an amazing place, but we were wowed by these types of 'extras' that make our children so happy. What a gift that we can get them out of the house and away from the television, engaged with nature, being physically active, and enjoying family time.” These comments were expressed by Marzi Wiley, child psychologist, and her husband, Ben, pediatrician.

26 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Case Study

This

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Case Study 27

Initial master plan shows play pockets, which were located in GIS with aerial photography.

A family enjoys a playful spot nestled among the trees.

A play pocket around the corner motivates children to enthusiastically move to their next discovery.

Pathways for Play

Best practice design principles

Pathways for Play offers a powerful strategy for creating networks of play opportunities permeating the community, targeting the primary user groups:

u Independently mobile children

Family groups

Family groups most likely include parent(s) and child(ren) but also may include grandparent(s) or other relations. Growing in popularity across the country are self-organized groups of families enjoying the outdoors, often motivated by concern for their children losing contact with nature.79 Cycling family groups have the same motivation as walking but are able to extend their territory to a larger range of destinations.

u Organized youth groups

Out with friends, typically going “somewhere” (park, playground, neighborhood store, open space) is a viable image of a middle childhood active lifestyle as it was a generation ago – kids out playing independently. It needs to be deliberately supported today. One or more dogs may be part of the group – providing motivation for being “out.” Cycling groups of children have the same motivation as walking but are able to extend their territory to a larger range of destinations.

u

Schools could be frequent users of playful pathways with students engaged in “active curriculum” tasks from physical education to science and everything in between. In addition, summer camp, church youth, scouting, and any number of other organizations serving children and youth should discover new, exciting possibilities in playful pathways.

To motivate children, families, and youth organizations to get outdoors and engage in healthy, stimulating activity in natural surroundings, the PathwaysforPlay strategy is driven by five best practice design principles:

Infuse play and learning value into pathways Create shared-use, inclusive pathways

28 Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Best Practice Design Principles

Pathways for Play: Best Practice Guidelines n Best Practice Design Principles 29

Connect pathways to meaningful destinations

learning

Locate pathways where children live Apply appropriate themes for

Infuse play and learning into pathways

• Provide a diversity of play opportunities to attract a broad range of children by age, ability, and racial/ethnic background and to support all developmental domains: psychomotor, social-emotional, sensory, communicative, and cognitive – to satisfy multiple maturity levels of children.

• Ensure varied levels of healthy, developmentally appropriate risk taking and challenge for all children so that play value matches levels of children’s skill development and supports opportunities for play along a continuum of skills.

• Manage hands-on nature as an important means for motivating play along the way by providing robust, naturalized settings designed to withstand and recover from intended play activity.

• Provide a mix of native plant materials that offer additional play value, shade, wildlife habitat, natural loose parts, and year-round visual interest in color, flowering/fruiting, texture, and fragrance.

• Locate play pockets at regular intervals as allowed by corridor width and other physical limitations, located off adjacent main tread to provide additional, substantial play opportunities, elements of discovery, and healthy physical activity through natural play prompts. Research potential easement restrictions (floodway and wetland delineations, utility and sewer rights-of-way, fire access, etc.) early on to avoid later legal issues. design principle

Playfulness can be infused into pathways in a multitude of ways. In this example, the pathway suddenly becomes a maze of giant grasses where children can have lots of fun.