Have The Disney Princesses Kept Up With The Times?

This essay discusses ethnic diversity and female gender roles in the Disney Princess films. These topics are explored further in a case study comparing online reactions to Disney’s live-action film remakes of The Little Mermaid and Cinderella. Analysis suggests that Disney recognises the need for greater diversity and has made some efforts to incorporate this into the Princess characters. However, there are challenges associated with doing so when personal childhood memories of the Princess characters are valued by the public; the demand for Disney princesses to remain all that they ever were, despite originating in a different era, whilst also embracing the values of the current time is a difficult path to navigate, both for Disney and the public.

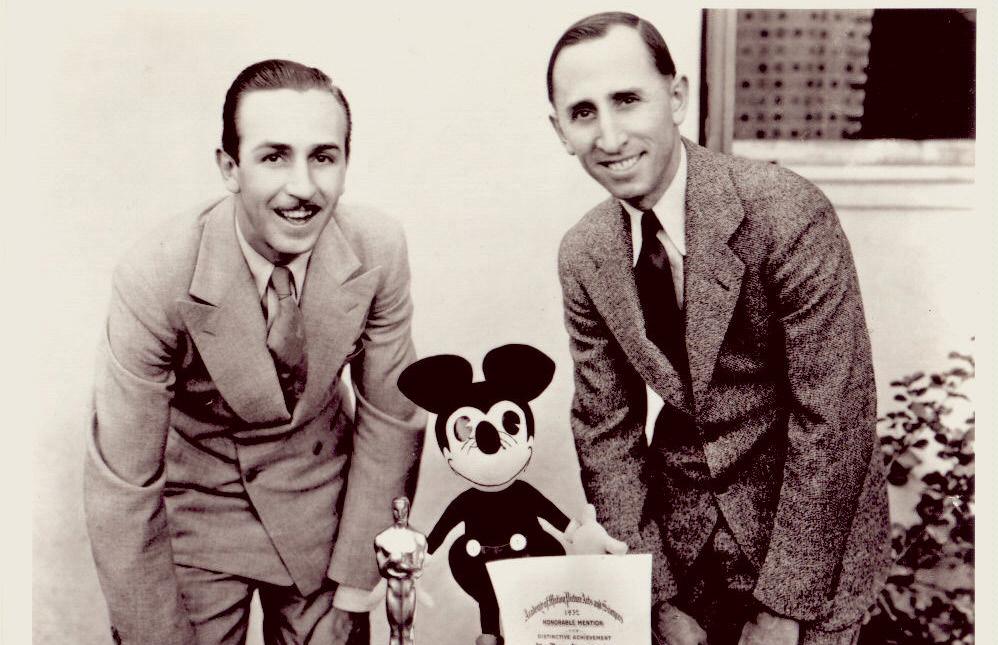

The Walt Disney Company is one of the largest conglomerates in the world with a net worth of $170.93 billion, as of 13th March 2023 (“Disney Net Worth 2010-2022 | DIS”). The company was founded a century ago by Walter E. Disney, better known as Walt Disney, and brother Roy O. Disney in October 1923 (“Walt Disney Company is founded”). Walt Disney, a talented artist, alongside Roy, launched the company in their Uncle Robert’s garage at Kingswell Street, Los Angeles, California (fig.1). The garage is now located in the Stanley Ranch Museum, a short distance from Disney World, (“Stanley Ranch Museum (Walt Disney’s Garage)”). From humble beginnings the Walt Disney Companies first feature-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938), was produced and the film quickly grossed an unheard-of $8 million worldwide becoming the highest-grossing film ever by 1939 (Hamilton). Now, 100 years on, there are 13 official Disney Princesses. What began as a handful of animators producing short children’s cartoons has grown into one of the most iconic and successful conglomerates in the world; with around 200,000 employees, 36 Disney theme/amusement parks around the globe, the Disney Cruise Line, Disney on Ice, the Disney Store chain, and Disney Theatrical Productions to name a few subsidiaries.

Due to the centenary anniversary of the start of Disney, it feels timely to ask, 100 years on, have the Disney Princesses kept up with the times? With over 800 animated characters, including the 13 official Disney Princesses, who are loved and cherished by millions around the world, it is important how Disney choose

to represent their characters and their female leads. Disney’s decisions have the power to influence the way in which people see themselves, or don’t see themselves, in their films. In this essay I will explore diversity in Disney, both generally and historically in relation to the storylines and characters in the animated films as well as the presentation of the Disney Parks and more specifically in relation to ethnicity and female gender representation in the Disney Princess films. To examine the issues of ethnicity and female gender role representation in the wider social context I will analyse the portrayal of Cinderella and Ariel, in the live-action remakes of Cinderella (2015) and the soon to be released The Little Mermaid (May 2023). For both films, the actors playing the princess roles have been subject to media and public scrutiny in terms of their physical appearance. Although these films only appear eight years apart, during the intervening years between 2015 and 2023 there have been significant shifts in society’s attitudes towards the need for diversity and inclusivity to be prioritized.

These shifts arose due, at least in part, to significant social change movements which have led to global changes: The #metoo movement aims to expose and change sexual violence and harassment experienced by women. It was founded in 2006 but became prominent in 2017 when several high-profile actresses revealed their experiences with sexual harassment in the film industry; The Black Lives Matter movement is dedicated to fighting racism and anti-Black violence. It was founded in 2013 in response to the acquittal of the murderer of an innocent black man, Trayvon Martin, but again, gained more widespread

acknowledgement in 2020, with the release of a bystander video showing an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, being killed by a white Minneapolis police officer, who knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes. Social media has played a significant part in developing the prominence of these movements and consequently there have been radical changes in the way we view, talk about, and tolerate certain matters, including sexism, misogyny, assault and racism. Diversity and inclusion (i.e., respect for, and acceptance of, our differences) have become important global values, with wide application (e.g., in educational and workplace settings, as a consumer, in personal relationships and daily life).

I will question how these societal changes are addressed and represented by Disney in these films and captured by public reaction to Disney’s decisions, by examining both the presentation of the characters and public opinion about these films and the Princesses more generally. I will suggest that there are tensions between some of the fundamental characteristics of Disney Princess films and society’s attitudes towards diversity and inclusion which raises challenges for Disney. At the same time, for the public, there can be difficulties associated with accepting this shift in attitudes when put into practice in the context of the Disney Princess films.

I chose this topic as in my own work I often find myself drawn to the portrayal of women, both real and

fictional, throughout history. As someone who loves film, especially old Hollywood black-and-white films, and the Disney classics, I have been aware of the need for change in the representation of the Princesses. It’s a reoccurring theme that women tend to be judged and criticised more harshly than men for their actions and appearance, and often by other women. As Naomi Wolf states in Beauty Myths “If a woman loves her own body, she doesn't grudge what other women do with theirs” (25), but with the unrealistic and sometimes unattainable bodies shown to us by Disney, whether a cartoon or human, it is hard to ensure that the young girls watching the films will love their own un-corseted and un-edited bodies happily thereafter.

Historically, there are a number of spheres in which Disney Princess films (and broader Disney films) have lacked diversity, including the similarity of the essence of the plot and the physical presentation of characters via the animation.

The fundamental points in the storylines of the original Princess films were unfailingly identical, each one beginning with “once upon a time” – princess meets prince and falls in love at first sight – and then ending with the welcomed and familiar “and they lived happily ever after”. Because the Princess films were based on pre-existing fairy tales/folktales, one might think that the plotlines were determined by the original story, rather than by Disney; however, many of Disney’s animated films were greatly changed from the original story to maintain the ‘Disney magic’ that they became known for. By removing the less palatable elements of the original stories, Disney’s adaptations ensured that the plot conformed to the positivity of ‘making everyone’s dreams come true’, which are to this day reflected in their company values of: “optimism”, “innovation”, “decency”, “quality”, “community”, and “storytelling” (Cotter).

In more recent times the storylines for the Disney Princess films have become less formulaic, perhaps because the future of the brand is secure, and they can now afford to take the risk of a film being unsuccessful. For example, Disney’s 2012 film Brave is an original story, not a retelling of a classic fairy tale or folktale; the 2013 film Frozen, ends with the Queen being saved, not by a man but rather, by the love of her sister, another first for the Disney Princess films.

Also important when considering the development of the diversity of work produced by Disney Studios are the technological advances since 1923. Walt’s original animation team was made up of only nine men, working around the clock drawing each frame by hand (Widmar). Twelve to twenty-four drawings were needed per second for usable footage with believable movement (Widmar). This tedious and laborious process of making an animation led to the Walt Disney team reusing the same templates for various films to save time and money. This is perhaps a reason why there was such a lack of diversity in the characters’ appearance in their earlier films. The images above (fig.2, 3 and 4) show this with side-by-side comparisons of stills from the films: The Jungle Book alongside Winnie the Pooh; and Robin Hood alongside Snow White. There is an uncanny resemblance in pose. Despite animation still being a slow and expensive process today, the scope of what animators can now do with CGI and special effects is limitless, especially alongside the handsome budget that Disney can now allow for. Understandably there is therefore less sympathy in the present day for any lack of diversity in their films because Disney now has the time, money and technology to be able to create more diverse characters. However, whilst overlapping character poses in animations no longer feature, it is questionable whether they have achieved diversity in some other respects of characterisation, as will be considered further in later parts of this essay.

Lack of ethnic diversity is something the Walt Disney Company have been regularly criticised for by the public. Many of the films are retellings of classic stories as highlighted by Hoffmann: “imbued with the values of a different time and place” (60). However, they often end up stereotyping and perpetuating: “the values of one class, ethnic group, or other social segment” (Hoffmann, 60). This dominant white, male viewpoint is problematic for a contemporary audience.

Twenty-six years after Walt’s death in 1966, Princess Jasmine (1992) was introduced as the sixth Disney Princess. She also became the first non-white Princess. Three years later in 1995, Disney made Pocahontas and then three years later Mulan, finally adding racial diversity to the collection. Eleven years later, the next colored Princess was Tiana from The Princess and the Frog (2009). Although Tiana is an African American Princess, she only gets a small amount of screen time as a black Princess before being turned into a frog, limiting the time where the viewer can see her skin colour.

As well as lack of ethnic representation, Disney have tried to move onward from the uncomfortable images of racial and ethnic stereotypes so prominent (in retrospect) in some of the Disney classics. Controversy has arisen due to the ethnic caricatures depicting Asian (e.g., the Siamese cats (Peggy Lee) in Lady and the Tramp (1955) (King et al. 2); the cats in The Aristocats (1970) featuring thick accents and playing the piano with chopsticks, and black African ethnicities, e.g. the crows in Dumbo (1941); and King Louie the ape (Louis Prima) in The Jungle Book (1967). Criticisms have been placed on films such as Peter Pan (1953), with the stereotypical interpretation of Native Americans as “redskins”, although at the time, this portrayal wasn't controversial. The song "What Made the Red Man Red" and lines such as "Peter Pan save me, me his velly nice friend” and “Me no let pirates hurt him" from the chief’s daughter Tiger Lily is clearly a very crude stereotype. There are examples of Disney more often and more accurately, depicting other cultures in their more recent films, for example Encanto (2021) which depicts a Colombian family, and Coco (2017) which is a story about a Mexican boy (Towbin 37). However, these characters from other cultures are typically not a Princess, “non-dominant groups are (still) portrayed negatively, marginalized, or not portrayed at all” (Hoffmann 65).

The fact that in 2023, only four out of the thirteen Disney Princesses aren’t white is a source of frustration for many (fig.5). Not only is this misrepresentation shown in the films but also in Disney’s retail stores (in person and online), which attract millions of visitors each year. Stores sell a wide variety of merchandise to go along with the films, including toys, costumes, clothing, and collectables (Fisher). But if only four out of the total thirteen Princess films feature women of colour, this means that less than 30 percent of the store will sell items featuring non-white characters. Children of colour likely do not see themselves represented by the Princesses in the same way that white people are. The impact of this marginalization and lack of recognition was noted by black, feminist writer Audre Lorde who stated, “in our world, divide and conquer must become define and empower” (Lorde 19). As a global brand it is Disney’s responsibility to ‘define and empower’ people of all shapes, sizes and colours.

During Lockdown in 2020, in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement, there was heightened awareness of the need to improve representation of black and minority ethnic people in television and film. On the 13th of June 2020 large numbers of films were censored from viewing, such as the 1939 Hollywood classic Gone With The Wind, for including representations of slavery. Disney’s awareness of some of their controversial and problematic choices related to ethnic representation in their past films predated this, as Disney have been self-censoring plots, dialogues, characters, and images for decades.

An example of a film where images and sections of the film are erased is the 1940 film Fantasia. Figure 6 shows screengrabs from both the original and the updated censored version. The original shows a racist caricature of a centaur named "Sunflower", cleaning the hoofs of the white centaur. In 1969 with the re-release of the film, and all versions since, the character Sunflower has been cut, with all traces of her character removed. Censorship also occurred in the Disney Princess films too; in Aladdin (1992) three lines of dialogue were removed from film’s opening song “Arabian Nights,”, due to complaints about sexism and racism (Fox). The original lyrics were:

And were replaced with:

For other unsuitable films, Disney’s solution has been to have a warning shown before the film starts: “This program includes negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures. These stereotypes were wrong then and are wrong now. Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together” (Brenner). One Disney fan, Frederik Vezina, wrote on an open chat page: “Disney is a family brand. They are stuck between a rock and a hard place because they have parents who want a 100% wholesome safe place for their kids to watch whatever, and grown-ups who want to watch the movies of their youth the way they remember them. Content warnings seems by far the preferable solution” (Vezina).

Following the widespread film and TV censorship in 2020, The Guardian newspaper’s headline read “Censoring old films and TV shows misses the point, say BAME leaders”, “Critics warn that ‘panic-erasing’ distracts from what really matters: employing more ethnic minorities on and off screen”. Disney’s attempts to embrace this alternative approach by casting a black actor in the role of Princess Ariel will be considered in the case study below.

-THE GUARDIAN NEWSPAPER

“CRITICS WARN THAT ‘PANIC-ERASING’ DISTRACTS FROM WHATREALLY MATTERS: EMPLOING MORE ETHNIC MINORITIES ON AND OFF SCREEN”

Disney’s portrayal of the female gender in the Princesses, both their physical appearance and their role, have been characterised by a lack of diversity until very recently. In relation to the visual characteristics of the Princesses, some of this at least can be attributed to the animation production process used. In the earlier films, Disney would use actors in costume to serve as live-action reference for the animators to draw from. For Walt this was an important step for ensuring his team’s drawings of human form and their movements were "as real as possible, near flesh and blood". Helene Stanley was the “Performance model” who would pose and dance in front of the animation team for both Princess Cinderella and Princess Aurora. Figures 7 and 8 show stills of Stanley in a blonde wig and costume designed by Alice Estes for a scene of her dancing with the woodland animals in Sleeping Beauty (Kalmakurki 16). By using the same woman as the “performance model” for multiple Disney princesses it meant the movements of the characters, and the bodies of the characters themselves, were similar across the films and the millions of children watching were exposed to the same idealised version of beauty. Peggy Orenstein in Cinderella ate my daughter argues:

Each thing is ‘a cog in the round-the-clock, all-pervasive media machine’ aimed at our daughters – and at us – from womb to tomb; one that, again and again, presents femininity as performance, sexuality as performance, identity as performance, and each of those traits is available for a price. It tells girls that how you look is more important than how you feel. More than that, it tells them that how you look is how you feel, as well as who you are.

(Orenstein 183)

However, the visual depiction of the Princess characters, even the earlier ones, were influenced by external cultural and social factors too. These are particularly evident in the design of Aurora. Sleeping Beauty was released not long after the hugely popular production of Mattel, Inc.’s Barbie doll in March 1959, and Aurora’s figure also bears some resemblance to Barbie’s. Compared to earlier Princesses, Aurora more closely resembled the American beauty- ideal in this post-war glamour period (Kalmakurki 17)(fig.9, 10). Her appearance also differed from the rest of the film’s characters, being less derived from medieval fashions and more consistent with the hair and wardrobe fashions of the time. Such adaptations evidence how the wider social context influenced Disney’s choices about how to represent their character.

Judy Attfield in the ‘Barbie and Action man’ case study from the book The Gendered Object explains how the Barbie doll provides unrealistic features, such as tiny hands and feet and a waist twice as small as her bust, which parallels how Disney had created similarly gravity defying proportions in their cartoon depictions of the Princess characters (Attfield 82). Perhaps understandably, public concern about this presentation of the characters was increased once the cartoon characters were translated into films with “real” people with supposedly “real” bodies.

The roles of the female characters have also been highly gender stereotyped. In the hands of male tellers in a predominately male company, the leading ladies and heroines in the Disney films tend to be depicted as passive, if not helpless, without a man to help them. Barbra Ehrenreich highlights:

Disney likes to think of the Princesses as role models, but what a sorry bunch of wusses they are. Typically, they spend much of their time in captivity or a coma, waking up only when a Prince comes along and kisses them. The most striking exception is Mulan, who dresses as a boy to fight in the army, but–like the other Princess of color, Pocahontas–she lacks full Princess status and does not warrant a line of tiaras and gowns. Otherwise, the Princesses have no ambitions and no marketable skills, although both Snow White and Cinderella are good at housecleaning. (Ehrenreich)

Films are vehicles for self-exploration and understanding of the world and how it works; young children constantly seeing either the same body type, or females being rescued by a handsome strong man, will certainly have implications for how they view not only themselves but also others around them. As Audre Lorde said, “As women, we have been taught to either ignore our differences, or view them as cause for separation and suspicion” (Lorde 18). In Disney, differences between males and females are emphasized in a way that unhelpfully creates division.

Studies have shown that children’s behavior, attitudes, and self-esteem are impacted by the films and TV they watch (Livingston and Bovill). The portrayal of the Princesses in Disney’s films helps make ‘crucial contributions’ to the most paramount view of the self, subconsciously informing children how women ought to act, think and dress (Miller and Rode 86). In Sleeping Beauty, Princess Aurora only had 14 lines throughout the whole film, along with her songs (Griffin, et al 880). Altogether in the Disney Princess animated films the male characters speak between 68% and 77% of the time, effectively silencing female characters (Fought & Eisenhauer, 2016). Amy M Davis examined the Princesses in ‘The Classic Years’ (1937-1967) stating their representation was “largely static” (Davis 137). She argued that the princesses were at their least active and dynamic as they carried out traditional feminine roles such as domestic work and passivity. The lyrics from Snow White’s song ‘whistle while you work’ (on the right) quite literally give the message that cleaning up after seven lazy men is good fun (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, ‘Whistle while you work’, 1937).

‘Just whistle while you work

And cheerfully together we can tidy up the place

So hum a merry tune

It won't take long when there's a song to help you set the pace

And as you sweep the room

Imagine that the broom is someone that you love

And soon you'll find you're dancing to the tune

When hearts are high the time will fly so whistle while you work

So, whistle while you work.’

There is a stark contrast between ‘the Snow-White (fig.11) type of Disney Princess’ and some of the more contemporary counterparts which circulate a more modern set of gender norms (Davis 35). The era of more self-sufficient Princesses emerged; Princess Merida (Brave)(fig.12) for example, a Princess who doesn’t need a prince, who saves herself and her family on her own, and who ultimately remains single at the end of the film. More empowering storylines have also appeared in other Princess films such as Mulan, Frozen and Princess and the Frog. In Good Girls and Wicked Witches Davis argued this shift arose after Walt’s death, releasing them from traditional gender roles, giving them more independence and a stronger sense of purpose and personality in the films. The change may also have happened organically along with gender norm changes in the real world, especially when coupled with the expansion of social media use, which gives a greater voice to public opinion, and which encourages responses in reaction to this opinion.

Another area which contributes to perpetuating lack of diversity and where the appearance of the Disney Princesses is strictly regulated is in the Disney theme parks; the ‘happiest place in the world’, where the characters’ outfits, hair, and makeup are tightly controlled (Spector). With a total of 36 theme/amusement parks they are a huge source of profit; in 2019 they generated 20.2 billion dollars of revenue (Fisher). Part of the reason for their popularity and success is due to having believable ‘real’ life characters there to meet the visitors, creating a truly magical experience (fig.13 and 14).

Due to the importance of the actors in the parks, the audition process is long and competitive. Their voice, body, facial proportions, height, teeth and body movements are scrutinized, to ensure consistency within the film characters and maintain the uniformity of the brand. Ex-park actor Melanie in an interview with Insider stated that most of her auditions consisted of “standing in a line and smiling with a number” as casting directors closely inspected her. She reflected upon this uncomfortable experience: “They’re getting really close up in your personal space to see your bone structure, to see how your skin is, to see your eye color, to see your eye shape, to see all these different things about you. They don’t say anything. So it’s really, really awkward” (Bennett).

Disney’s desire to keep close connections between the film characters and the park-actors is seemingly designed to enhance the magic for attendees. However, this also perpetuates the lack of ethnic diversity and the physical ideals apparent in the films, with the casting process evaluating potential actors purely based on their physical characteristics. This has implications for both the actors and those to whom they are ultimately exposed.

In this case study I will be comparing Disney’s live-action film Cinderella (2015) and the soon-to-be-released The Little Mermaid (2023). Lily James, playing the role of Cinderella, and Halle Bailey playing Ariel, provide a lens through which to explore the ‘ideal’ beauty standards Disney helps create. This case study discusses the backlash associated with each film and analyses press and red-carpet interviews with the leading actors. It also presents an analysis of their curated social media presence to illustrate how this is used to maintain the Disney ‘magic’, despite the parallel criticism in wider online discussion. To do this, I refer to public online sources along with data from my own online survey to examine public opinion. Due to the nature of the topic, the range of sources I refer to necessarily includes many non-academic sources.

In the 2015 live-action film, insights were given into Cinderella’s childhood, her relationship with her parents, and a more intimate and longstanding relationship shown with the Prince. This contrasts starkly with the original Disney animation, where Cinderella and the Prince fell in ‘love at first sight’ without having ever spoken a word to each other. Despite Disney adapting the storyline substantially from the 1950 animated version of the tale, the live-action film turned out to be a great success with a box office of 542.4 million USD (“Box Office Mojo – Cinderella”). But a prominent criticism arose: the size of the actor’s waist. The controversy started as soon as the official theatrical poster was released on the 19th of November 2014, ahead of the film’s release in March 2015 (PBADMIN). There was instant uproar with many newspaper headlines disapproving of how small Lily James’ waist appeared in her costume. For example: “‘If you’re nice to rats, you too can have a waist the circumference of a Coke can’: Cinderella makes $70m on its opening weekend, but filmgoers hit out over Lily James’s tiny waist” published by The Daily Mail (Robinson).

The image led many to believe that James' waist was digitally altered, and people were furious that Disney would set such an example for young girls. Some speculated that Disney must have used CGI in order to make her waist appear so minute, thus creating unrealistic standards for women. Disney vehemently denied this saying “Lily does just have a small waist” and that it was the voluminous skirt and corset that gave such an extreme hourglass illusion. Kenneth Branagh, Cinderella’s director, denied that airbrushing was used on James. In an interview with HuffPost Live Branagh said, "To all the airbrush conspiracy theorists I can answer now: no. The simple truth is, we didn't alter anything". In a Live interview with HuffPost James reflected on the negative attention by saying, "On one hand, it's upsetting. On the other hand, it's just boring. Why do women always get pointed at for their bodies? And why is this whole thing happening that I'm constantly having to justify myself? I'm very healthy and I always have been."

In 2015 Twitter and Facebook were the most prominent social media platforms (Martin), with the former specifically used for the sharing of opinions. The below screengrabs show the type of Tweets which were circulating at the time regarding James’ waist.

Thirty-four years on from the animated version, Disney have a live-action film of the tale set to release on the 26th of May 2023. Despite the film having not aired yet, from the release of the theatrical poster (on the left)and the one minute and twenty-four second trailer, there has been a worldwide conversation focused primarily on one thing: the colour of biracial American actor Halle Bailey’s skin and hair colour. Almost all the discussion about the film, both positive and negative, has surrounded the question of whether it was right to cast a black woman to play Ariel.

The official teaser trailer on YouTube has currently gained more than 28 million views, but also over 3 million dislikes, and sparked the hashtag “#notmyariel” on social media (Ta and Chiriguayo). Celebrating the significance of what this casting choice means for ethnic equality has been somewhat clouded by the views of some people; that the difference between Ariel being a Caucasian redhead in Disney’s 1989 animated film and being black in the live-action film is unacceptable, as evidenced in the screengrabs on the next page (fig 15 and 16).

Social media has changed a lot in the eight years between the releases of Cinderella and The Little Mermaid. When Cinderella was released, the current no.1 virtual app TikTok, where people share videos (and opinions), didn’t exist and the main source of online opinions came from Twitter and Facebook (Martin). Unfortunately, due to the way Twitter and Facebook organize their data it is not possible to access the number of Tweets/posts related to criticism of Cinderella as neither platform presents the total number (of views, posts/tweets) for each hashtag, like TikTok and Instagram do. This in itself is interesting and perhaps reflects that more recent platforms recognize the importance of transparency and the need to demonstrate public opinion. For Ariel I have therefore created a data table, shown to the right, displaying the trending hashtags on both TikTok and Instagram and the total number of views and posts for each. Videos with #notmyariel having over 14.9 million views, and #disneyexposed having over 85.8 million views, indicate the wide public engagement with this matter.

With both films there is/was contention over the appearance of the leading female actor and what Princesses should look like. For James the subject of concern was her unrealistic body shape and the negative message this would give young children; with Bailey the concern was her race, questioning why Disney would make such a considerable change to a pre-existing character. However, for both these criticisms there were also people questioning why these issues had even been raised in the first place. Although criticism for Cinderella was widespread on Twitter there were also some who defended Disney’s portrayal on Twitter; Shannon Ellison wrote, “When did being thin, or wearing clothes that make your waist look small, cause this self-righteous anger and condescending pity? #Cinderella”. There were also many videos showing ethnically diverse children reacting positively to seeing Ariel in the trailer for the first time.

In this section I present an analysis (particularly in relation to these criticisms of the films) of fourteen interviews with James and eight with Bailey, where they discuss the films that they star in. The interviews contrast in important ways between films, suggesting possible differences in the reactions (of both Disney and the media) to the criticisms that the films have received. It seems likely that, in least in part, this is because in today’s social context it’s acceptable (or even encouraged) to question and be opposed to the unrealistic beauty ideals that Cinderella’s body presented but it’s not acceptable to be opposed to the realistic, and diverse representation of skin colour as presented in The Little Mermaid. As such, the media have felt more able to directly address the online criticisms of Cinderella than Ariel and, anticipating this, Disney appear to have approached the interviews differently, for Cinderella, trying to ‘contain’ bad publicity, but not needing to for The Little Mermaid.

For example, in James’ interviews she appeared to be somewhat protected by rarely being interviewed alone, typically having her ‘Prince charming’ co-star Richard Madden, or other crewmembers (co-stars, producers, directors and costume designers) alongside her during interviews. In contrast, all except one of the interviews with Bailey have been unaccompanied, whether on a red carpet or in a set up interview space, perhaps suggesting there is less fear that she will need support to deal with difficult questions.

Fitting with this idea, there are striking differences in whether the criticism is addressed in the interviews. With James, on multiple occasions the size of her waist was discussed, including whether the image represented an attainable reality. In one of the few unaccompanied interviews, with Peter Travers, James discusses accidentally tightening one of the stepsisters’ corsets while filming. Travers remarked “People said that about yours too…people say is that your waist?!” to which James replied “Yeah, lucky mine was not that tight”. Travers continued to probe, “But let’s make sure we admit that’s you, they didn’t do any photoshopping?” to which James had to respond “No. It’s also the silhouette of the dress” before discussing her liquid diet, required so she could fit into the corset (“Lily James, Right Fit for the Classic Fairy Tale”).

Another significant interview when a question came up about her waist size was an open panel interview,

containing James, where the audience could ask questions. When the matter of her waist was raised, many of the panel members tried to mitigate the criticism. Firstly, the costume designer (Sandy Powell) said “I don’t understand what the concerns are actually” and “Lily’s dress in particular is an optical illusion I must say”. A producer (Allison Shearmur) added that her waist size had got too much attention and that people weren’t paying attention to the right things, before James questioned, “Why on earth are we focusing on something so irrelevant, you know there’s so much…” before being curtailed mid-sentence by a person off-camera who said, “Let’s move onto the next question!” (“Cinderella's Lily James & Cast React to Waist Size Concerns”). It is not clear whether this censoring of James was designed to change topic to keep the show engaging, to specifically divert the conversation away from the criticisms or to ensure that James herself, and thus the image of Cinderella, was not associated with potentially damaging and controversial comments.

As The Little Mermaid hasn’t premiered yet, the nature of the eight analysed interviews with Bailey are primarily to build-up press for the film’s release. This means there are many red-carpet interviews where the questions are unable to be pre-approved by Disney beforehand. It is therefore particularly interesting that the criticisms about a black woman being cast as Ariel have not been raised at all, indicating that the media are not engaging with this criticism. On the contrary, the interview questions have afforded an opportunity to celebrate the implications of this casting for equality and diversity. Over half of the analysed interviews with Bailey include her talking about what it means to be a black woman playing this role. For example an interviewer for Hollywood Reporter asked, “What’s been the most magical part of making this film?” to which Bailey replied, “Never thinking that somebody like me would be doing this is beautiful, and the fact that I get to kind of represent all of these little young black and brown boys and girls is really special to me because I know that if I had that when I was younger it would have changed my whole perspective on life” (“Halle Bailey Talks About Putting Her Own Spin On Ariel For Live-Action ‘‘Little Mermaid’’ | D23 Expo”). Of note, none of the analysed interviews specifically addressed concerns of her looking different to the animated Ariel character, nor asked her to comment on this online criticism.

As discussed earlier, significant social changes in attitudes towards equality and diversity, including associated with the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, appear to be represented in these interviews. The #MeToo movement changed the way we talk about gender issues in society, including sexism. Although acknowledgement of the need for fair and equal, non-sexualised gender representation of women has existed for decades (e.g. The Sex Discrimination Act, 1975), this is no longer considered a contentious or minority opinion in the Western world but rather there is open discussion, with active steps taken to try and work towards this. The online backlash associated with the Cinderella film appears to reflect these accepted opinions. The media therefore felt justified in raising these matters for discussion, with those involved in the film, which required some measures being in place to limit the damage this could cause (to the Disney brand and to the success of the film).

Similarly, the Black Lives Matter movement completely radicalized the way in which we discuss race and highlighted that there is room for improvement with respect to racial representation. However, the online criticisms levelled at the casting of The Little Mermaid do not represent this accepted social position and thus have not been prominent in mainstream media publicity surrounding the film. The fact that the first new live-action Princess film to be released since the Black Lives Matter movement ignited in 2020, will star a black woman as the lead role demonstrates Disney’s continued attempts to respond to social change. That this is the first time Disney have changed the skin color of a previously existing character is also significant; in the past Disney have kept the appearance of actors very close to the original cartoon characters, just as they do in the casting of Disney theme parks’ actors.

These recent attempts to adapt to social change may appear accelerated compared to the other changes seen in Disney films over the last 100 years, and indeed between 2015 and 2023 when these two films were released. But perhaps they simply reflect the accelerated wider social change which has taken place over the last few years. Of course, it is not known if Disney’s awareness of the need for change stems from idealistic reasons; an alternative explanation is that they want to avoid again facing any difficulties, such as with the live-action Cinderella, associated with not fully embracing the accepted social position in a world which is increasingly willing to be openly critical of any failure to do so.

Whilst the nature of the interviews differed between films, how the actors presented themselves when off-screen was consistent between the films. For both, they maintained the illusion of a magical version of their character. Disney’s lead actors are often required to sign restrictive contracts to maintain the appropriate ‘Disney’ image (Rae) and James’ and Bailey’s social media curation and wardrobe choices illustrate this. Figures 17, 18 and 19 are examples of James’ official Instagram account from the time of the film’s premiere. With a ‘Cinderella blue’ colour theme, the images exude glamour, in wardrobe and setting, creating the impression that she really was living the life of a princess, beyond her role in the film. James’ birthday cake (fig.19) was even shaped like her ballgown costume from the film.

There is a similar trend with Bailey’s Instagram (fig.20, 21, and 22), where watery colours of blue/green and tight-fitting clothes are reminiscent of her mermaid role and there are ocean settings consolidating the actor’s link with the film character.

Similar strategic choices are seen for red carpet and public appearances of other Disney character actors, ‘keeping the magic alive’ through their wardrobe. Angelina Jolie and Elle Fanning, who played Aurora and Maleficent respectively in Disney’s 2014 film Maleficent (fig. 23) exemplify this. The images above show how Fanning often wore light, flowing, and floral outfits, resembling her character’s costumes in the film. This was a high contrast with co-star Jolie who wore black, bold, and structured dresses that emulated her intimidating and powerful Maleficent character.

Similarly, for both Cinderella and The Little Mermaid, public appearances of the leading actors have been consistent with the characters they play. For example, Cinderella premiered at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival (13th February 2015) where Lily James’ hair was in a bun, and she wore a ballgown covered in sparkling diamonds befitting a Princess (fig.24). James even wore ‘glass slipper’ Jimmy Choo heels (fig.25).

Of note, given the controversy in the run-up to the film’s release, her outfit didn’t feature a corset. Similarly, Bailey’s glistening silver dress for the films premiere is reminiscent of both a mermaid (shimmering water, shell-shapes) and Princesses (fig.26). This shows some consistency across the Disney live-action films, with the magical escapism of the films being merged with the real world, through the actors’ portrayal of themselves on their social media platforms and at public events.

(Dates on air from the 29th of March till the 6th of April)

An online survey was conducted to explore participants’ views about the Disney Princesses and the live-action films addressed in the case study. A full copy of the survey questions is available in the appendix. One hundred responses were received. Details of the full sample are given in Table one.

Whilst the majority of the sample could name a Disney character who was Black, Asian or minority ethnic (88%), only 44% could name a Disney character with a disability and 43% any with a mental health condition. Due to the small number of participants in some demographic categories, for analysis, groups were collapsed to allow comparison of males and females who were young (18-35) or older (36+) and White or Other (Asian/ Black/mixed). Results (percentages of all responses) concerning their views about Disney characters and Princesses (and the number (n) of participants in each cell) are shown in Table Two. Explanations for how the open-ended free-text responses were coded are given in the table legends below.

Females and younger males could identify with Disney characters; for females this was primarily due to the physical similarities they perceived, whereas for males this was more due to personality similarities. Older males and females particularly saw the Princesses as good role models, but young males disagreed; seeing the Princesses as too dependent and gender stereotyped. Reasons why they were seen as good role models included their kindness and strength, as well as their ‘magical quality’, providing an escapist dream for children. Interestingly, men were more likely than women to see the Princesses as ‘strong’. Older women noted the positive change over time, and that Princesses had become increasingly diverse and better role-models. Participants of all genders, ages and ethnicities considered the storylines to have become more empowering in later films, compared with the earlier ones.

The sample’s favourite Disney Princess is represented in Figure 27. Reasons why this Princess was selected as the favourite are shown in Table Three. For white women (and men), of all ages, personality was a salient factor in their choice but for people of other ethnicities, a liking for the story/ film itself was also a significant factor. Across age groups and genders, another important reason was that they considered their choice a ‘classic’, traditional Disney character, with which there were particular childhood memories associated.

Reactions concerning the Live-action films are shown in Table Four. Women (particularly younger women) were more likely to have seen the Live-action Cinderella. The majority of all groups did not see anything wrong with the actor’s appearance but where a problem was perceived (only by women – and particularly young women of all ethnicities) the unrealistically slim body of the actor was a key concern. Young white women were especially positive about the casting of a black actor in the Ariel movie with reasons of aiming for equality and diversity being the most common reason across the groups. Older males and females also raised concerns about changing the original character, saying that it ‘just didn’t feel right’. Young males also suggested such a change being confusing for the audience. Younger participants (especially women) were aware of the backlash surrounding the casting of a black Ariel but the majority of the participants in this survey reported they would not mind if their favourite Princesses was cast as a person of a different

colour from the original, seeing diversity as important and ethnicity of the actress as generally irrelevant. However, there were some white women and men, of all ages, who were less accepting of this, saying that such changes were associated with a loss of familiarity/consistency with their childhood memories which, for some was upsetting. A number suggested that introducing ethnically diverse new characters (rather than changing the ethnicity of existing characters) would be preferable. Other research has shown that humans can form vivid and detailed memories for movie events (Tang 2016) and that the positive childhood memories associated with escapism of the Disney films specifically elicit positive emotions which are so powerful and long-lasting that they could even be used to facilitate associative learning in adulthood (Knudsen and Thomas). My current results also suggest that for some people these memories are significant, salient and they value them being intact.

“They’re totally removed from real life”

“Girls who act like princesses are very irritating”

“Unrealistic expectations for what you should look like, my 7 year old self shouldn’t have been crying about wanting straight blonde hair”

“Children need to believe in the power of good over evil and happy endings”

“Most of the characters are very kind and compassionate and inspire younger people to be the same way”

These findings are based on a small sample which, unfortunately, was not very ethnically diverse so it is not possible to generalise from these findings. However, they suggest that women, and particularly young women of all ethnicities, are critical of the presentation of Cinderella in the live-action film. Across participants groups there also appears to be a recognition of both the need for diversity but also an acknowledgment of how, by changing the existing characters, there is also for some people, a loss of something to do with the magical ‘essence’ of Disney which is rooted in people’s childhood memories.

Once upon a time, the 'magic' of Disney was as simple as the existence of an animated fairy ..............tale, involving a beautiful Princess, designed to enchant and entertain children and adults alike. Since those early days there have been changes in how films are evaluated. This essay aimed to explore whether the Disney Princesses have kept up with the times in relation to ethnicity and gender roles. Based on my research, including the results of my survey, I have presented evidence that Disney have continuously attempted to adapt to the world around them, in how they present their characters both through the storylines and visually. However, they face a difficult balancing-act of keeping intact a strong Princess brand identity, consistent with the publics’ cherished memories, whilst also responding to current social values.

As outlined in the case study, criticism with the live-action Cinderella was due to Disney keeping the lead actors’ appearance almost too close to the original, giving James the same (unrealistic) waist size as in the animated cartoon. However, when taking the opposite approach with the live-action The Little Mermaid, the backlash also stemmed from the Princess’ appearance, but this time for differing from the original. This highlights the challenges Disney faces when trying to keep up with the times and also navigating the varied and infinite public opinions so easily expressed via social media.

One of the valued core features of Disney’s films is the characters fixed form, both over time and across settings. Disney’s choice to adapt the appearance of Ariel in the live-action film raises questions about how Disney will translate this radical change, and having two different ethnic portrayals of Ariel, into the theme park characters and merchandise, where continuity between film and park characters is a hallmark feature. The possibility of extending this to the other Princesses is also highlighted. My survey results suggest that public reaction to this would be mixed, although generally accepting.

Part of the magic of the Disney Princesses is that they do not represent the times and worlds that we live in; their unreality is part of their escapist charm. However, as viewers are people of all ages, genders, races, cultures, and shape, they should see themselves appropriately represented in the Disney Princesses. A balance of both these aspects is required so we can all live ‘happily ever after’!