The Murillo Bulletin

About PHIMCOS

The Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) was established in 2007 in Manila as the first club for collectors of antique maps and prints in the Philippines. Membership of the Society, which has grown to a current total of 49 individual members, 8 joint members, and 2 corporate members (with two nominees each), is open to anyone interested in collecting, analysing or appreciating historical maps, charts, prints, paintings, photographs, postcards and books of the Philippines.

PHIMCOS holds quarterly meetings at which members and their guests discuss cartographic news and give after-dinner presentations on topics such as maps of particular interest, famous cartographers, the mapping and history of the Philippines, or the lives of prominent Filipino collectors and artists The Society also arranges and sponsors webinars on similar topics. Most of the talks are recorded and can be accessed by members through our website. A major focus for PHIMCOS is the sponsorship of exhibitions, lectures and other events designed to educate the public about the importance of cartography as a way of learning both the geography and the history of the Philippines. The Murillo Bulletin, the Society’s journal, is normally published twice a year, and copies are made available to the public on our website.

PHIMCOS welcomes new members. The annual fees, application procedures, and additional information on PHIMCOS are available on the website: www.phimcos.org

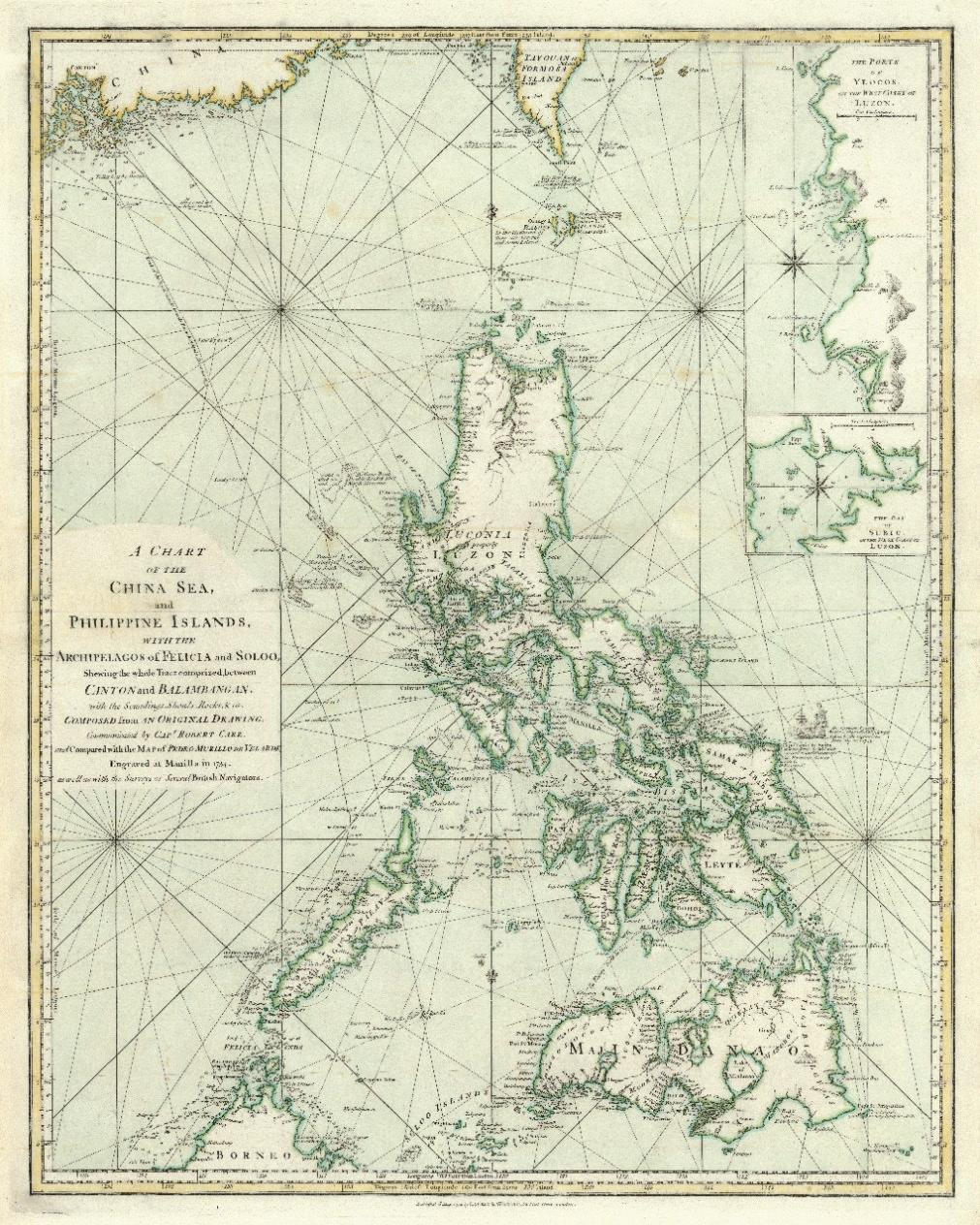

Front Cover: A Chart of the China Sea, and Philippine Islands by Robert Laurie and James Whittle, London, 1794 (image courtesy of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps)

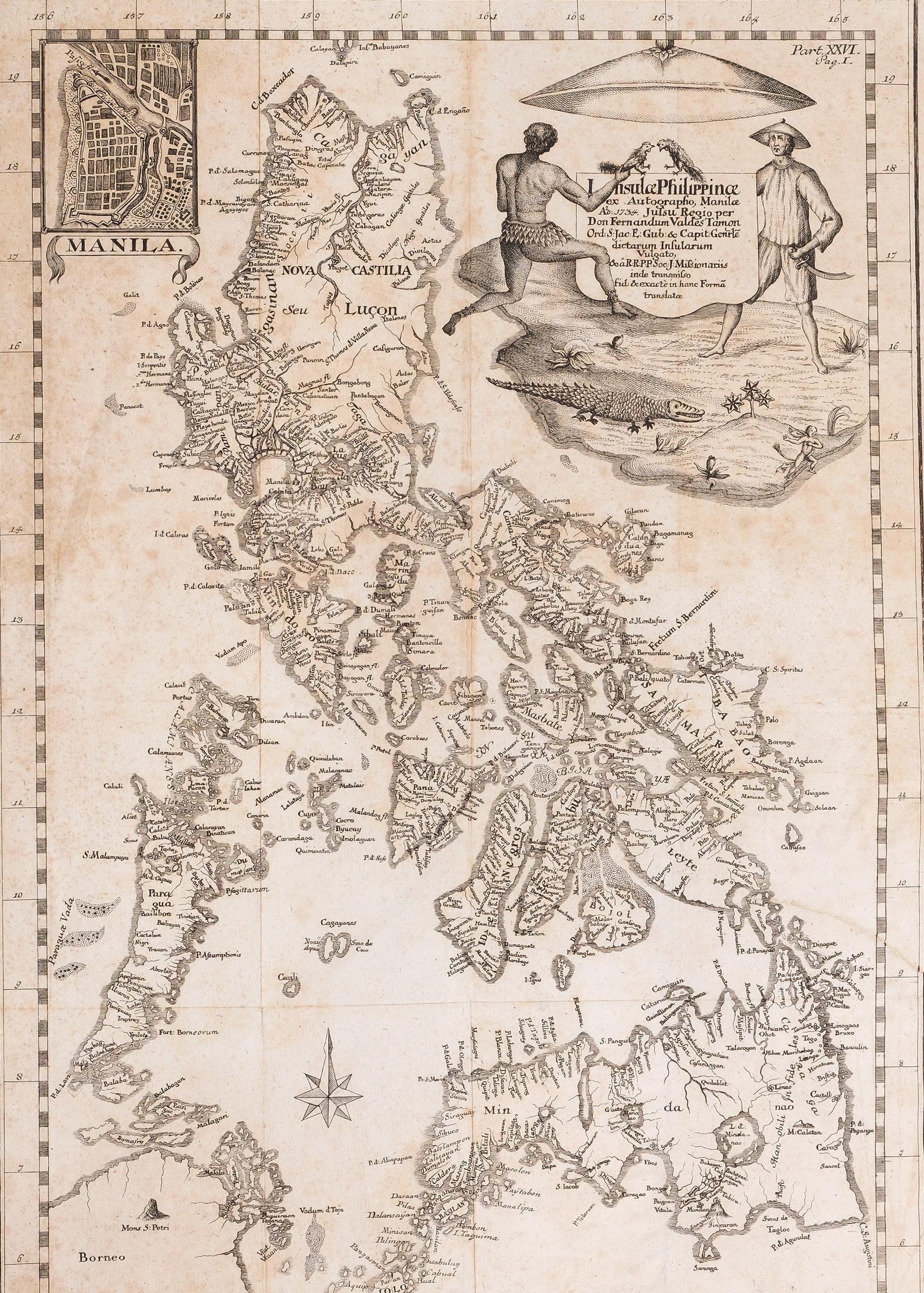

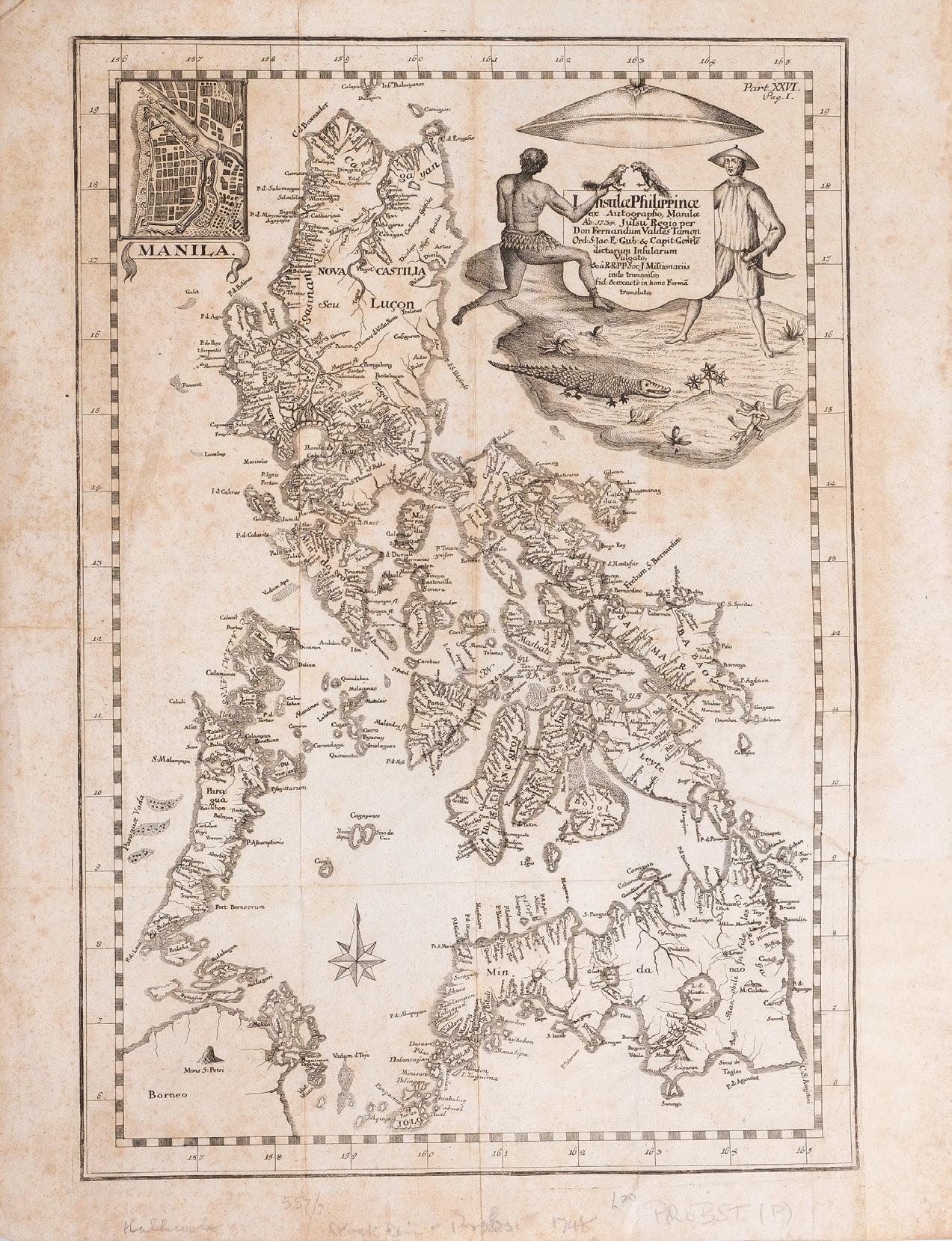

Insulae Philippinae ex autographo, Manilae Ano 1734. Julsu regio per Don Fernandum Valdes Tamon Ord. S. Jac. E. Gub. & Capit. Genrle. dictarum insularum vulgato, RRPP Soc. J. Missionaris inde transmisso fid. & exacte in hanc Forma translate

PHIMCOS News & Events

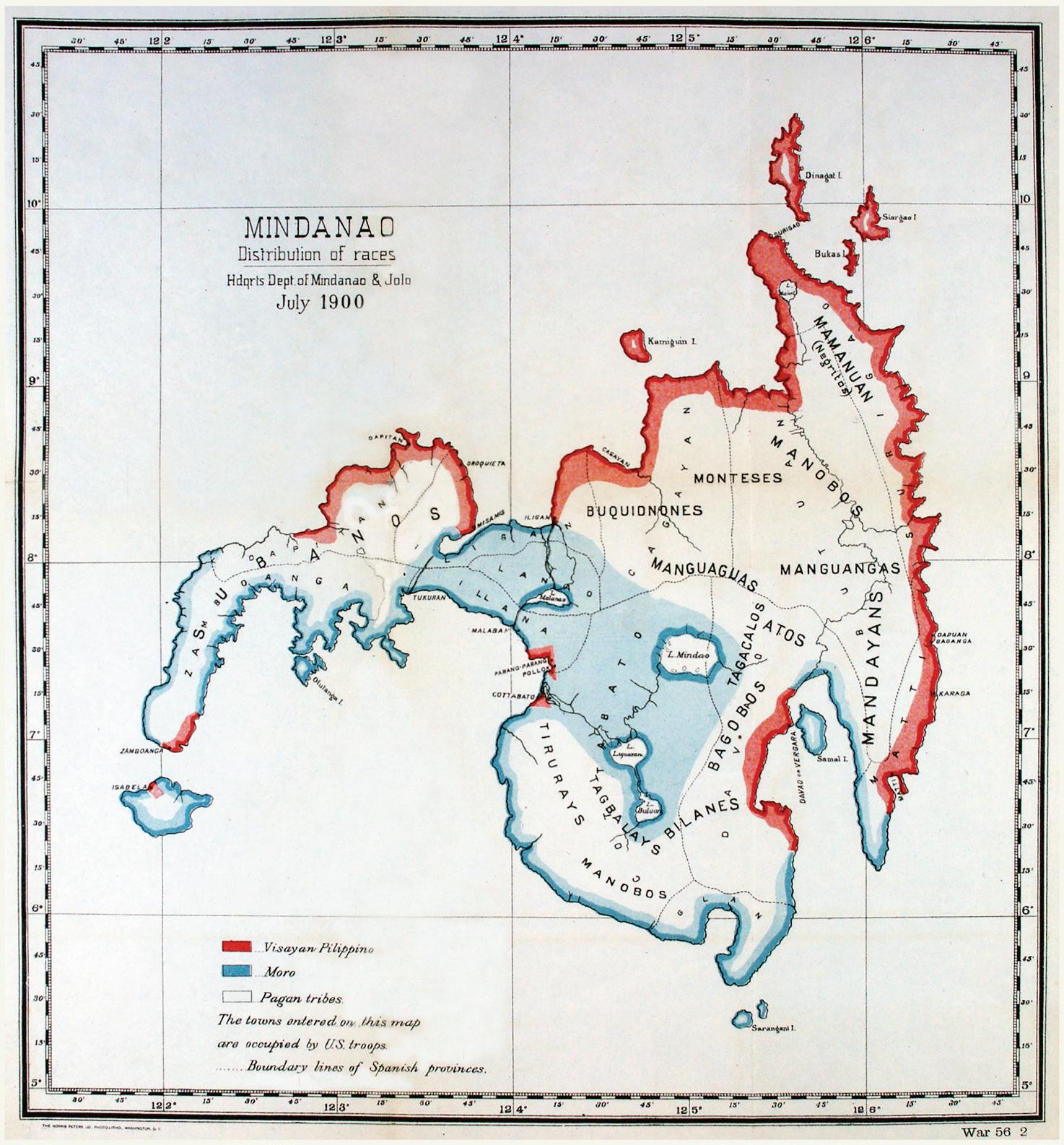

THE SECOND PHIMCOS meeting of the year, held on 14 May, 2025, was attended in person by 19 members and 12 guests, and via Zoom by 6 members and 5 guests. That evening we enjoyed two talks, the first of which was ‘The Lost Walls of Joló and the Palace of the Sultan’ by Carlos Madrid His presentation explored the use of historical cartography and georeferencing to unravel remnants of colonial structures, tracing the continuity of 19th century urban patterns and the connections between cartography and lost heritage with present- day communities. Carlos’s article on the subject is on page 31.

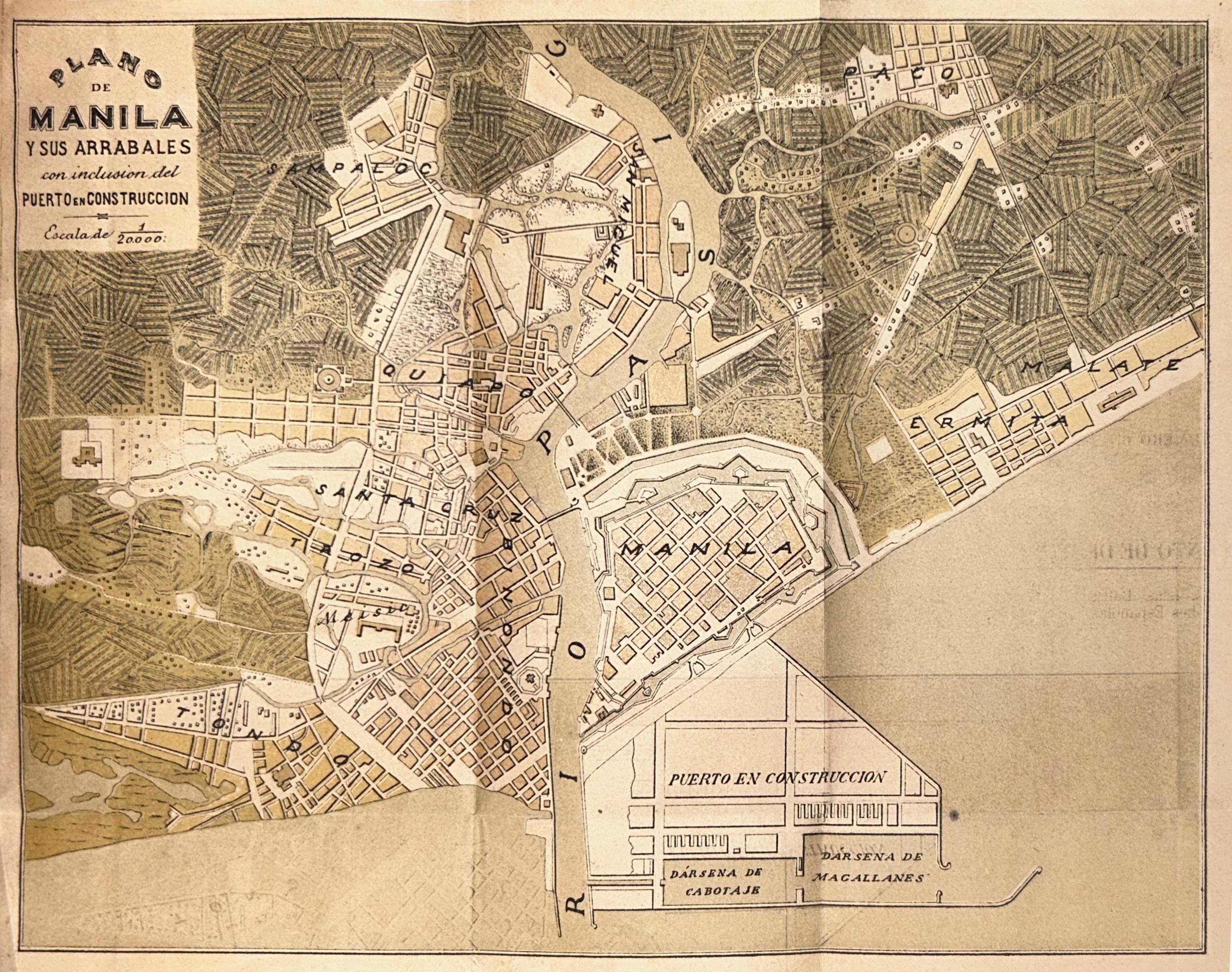

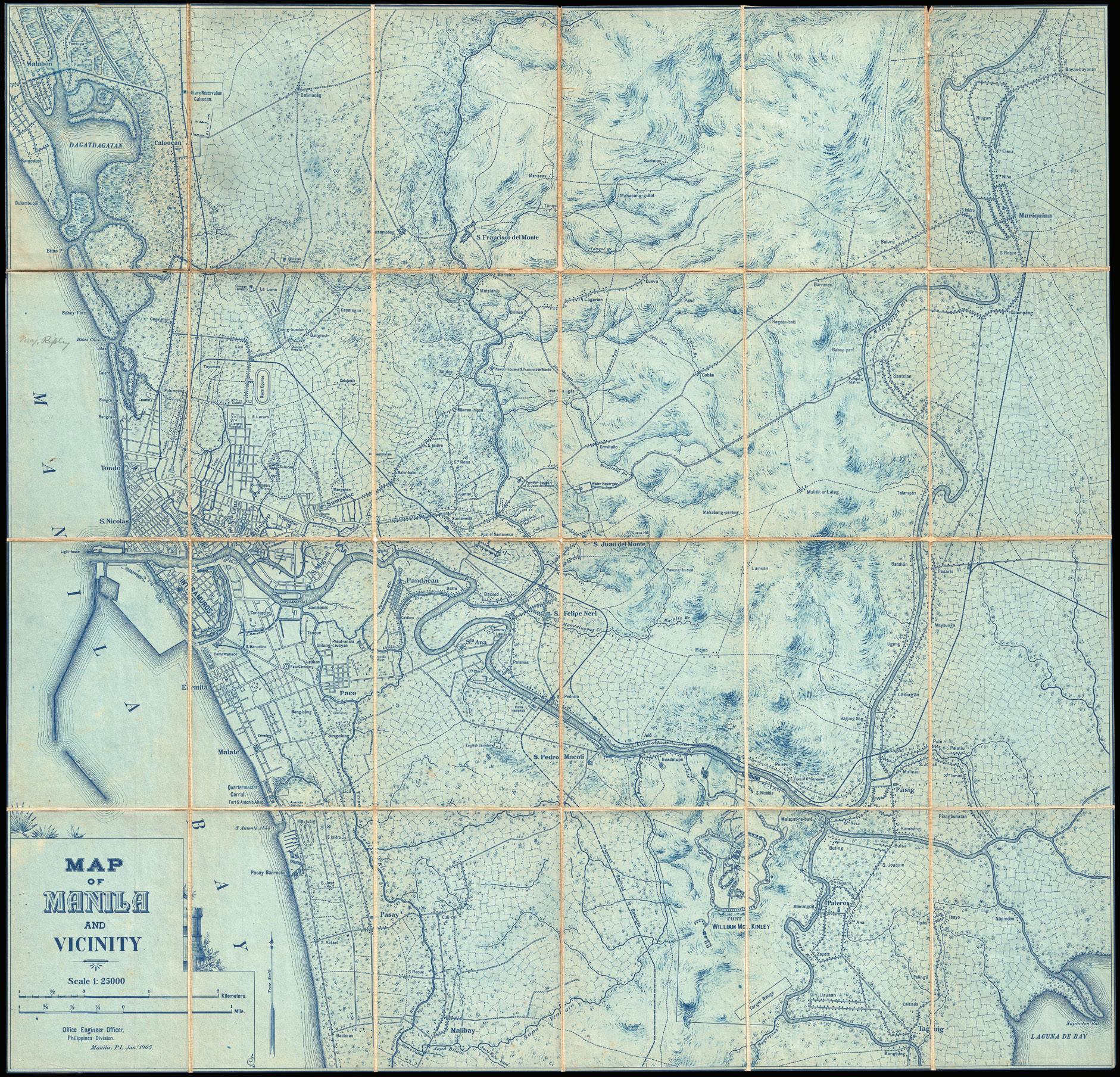

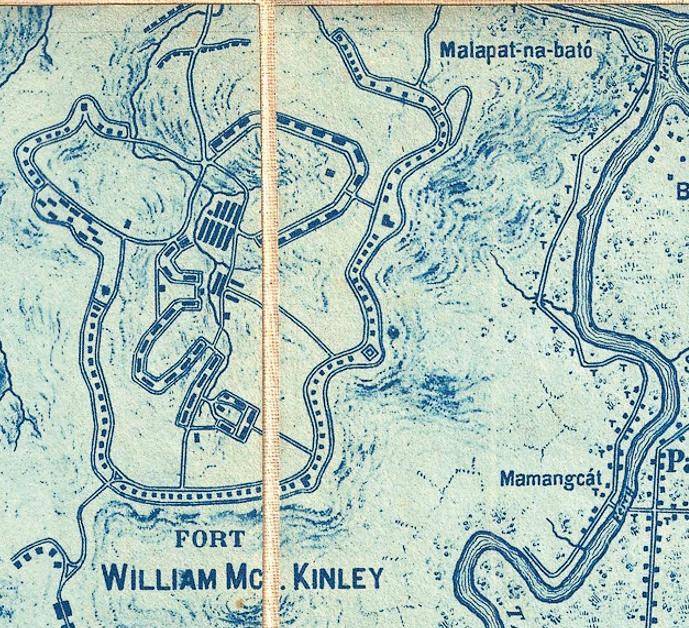

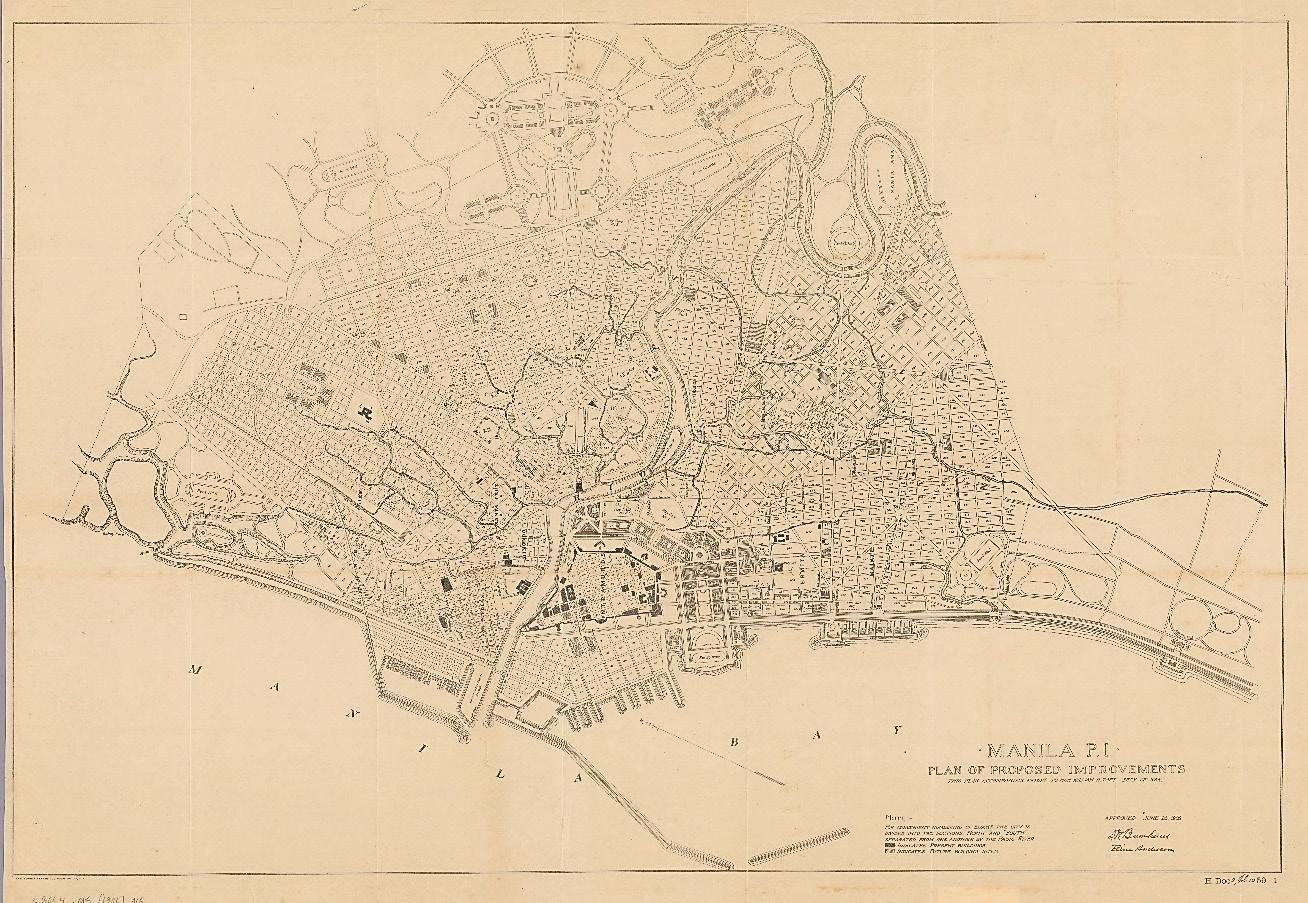

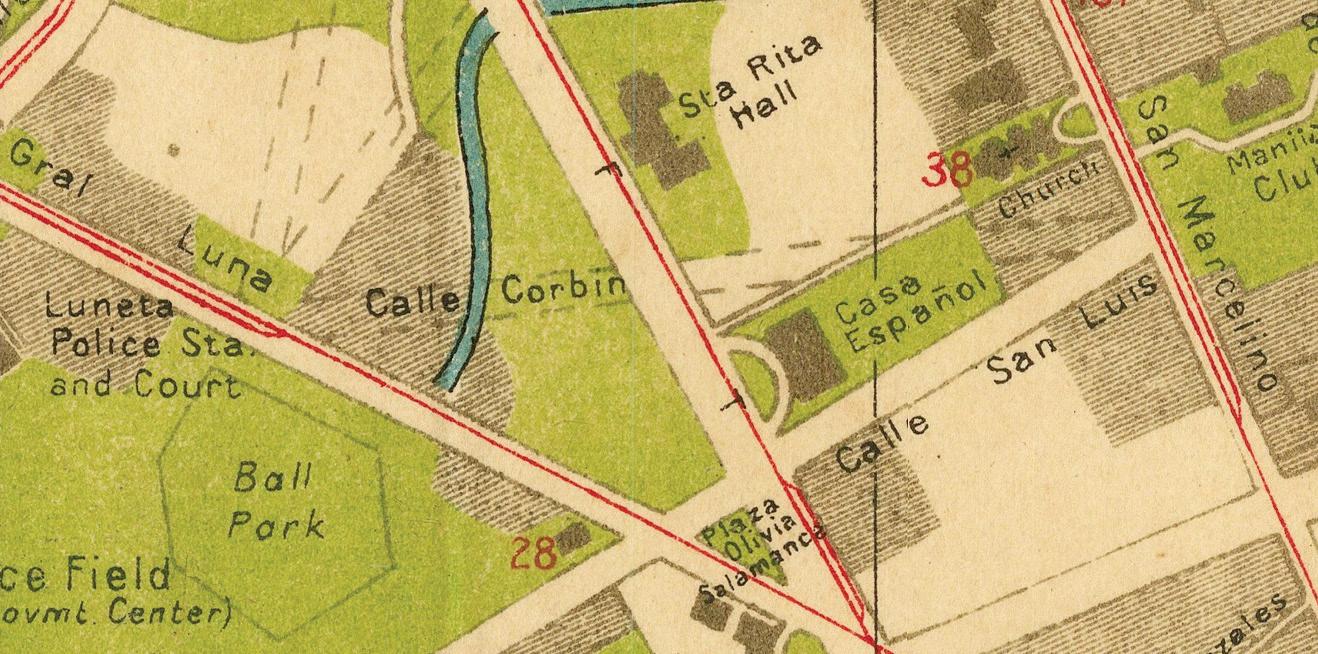

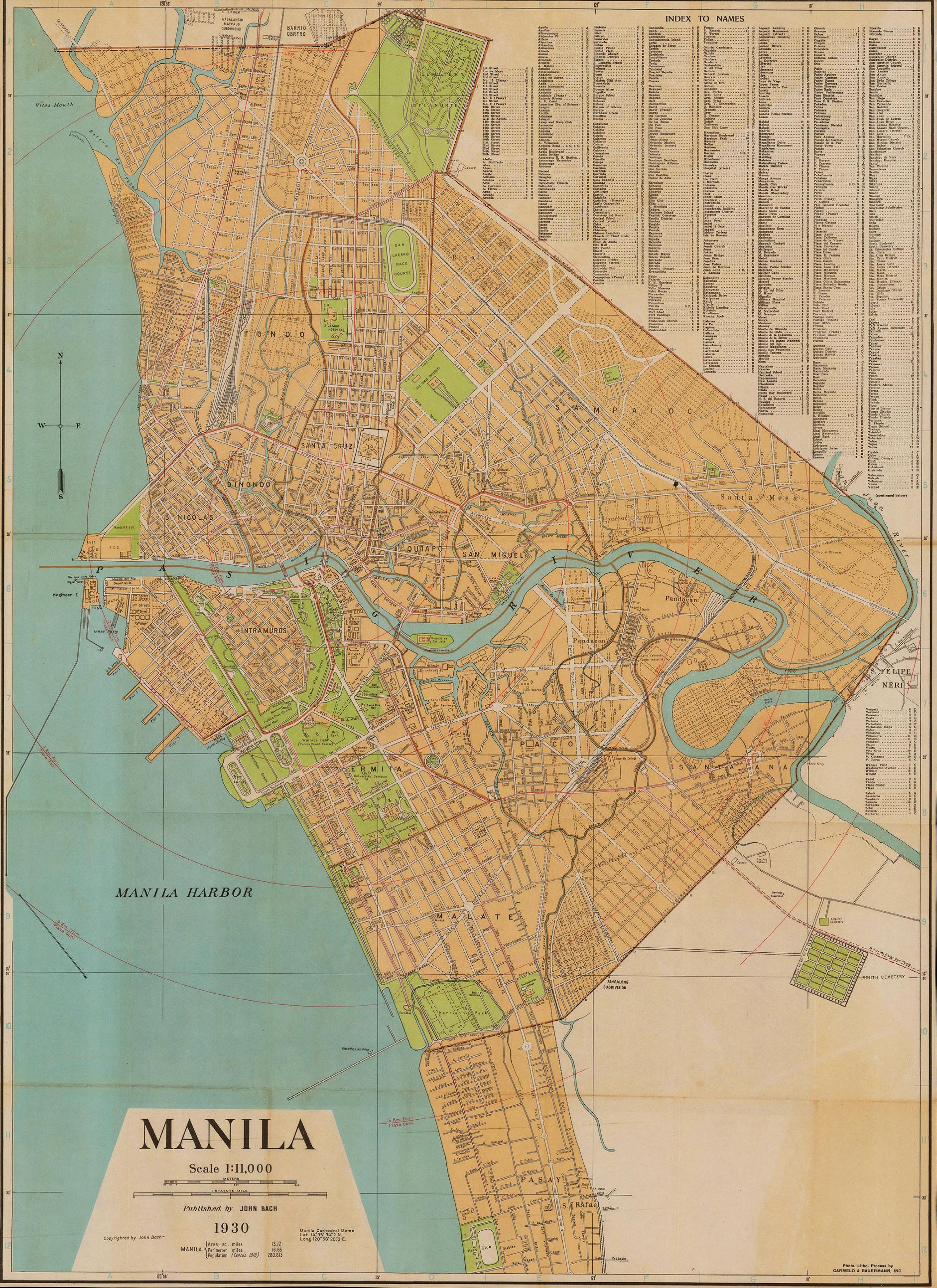

In the second presentation Miguel Santino Alvarez gave us his observations on ‘The Planning of Manila ’ , illustrating his talk with maps of the city illustrating its development from 1878 to 1942. Afterwards members were able to view the originals of many of these maps from the collection of Peter Geldart. Santino has expanded the topic in his article on page 37.

The third meeting of the year was held on 13 August; 27 members and 14 guests attended in person, and 6 members and 4 guests joined via Zoom. Jaime González and Sebastian Kroupa, a historian of science and medicine who is Assistant Professor at McGill University, gave a joint presentation on ‘Georg Kamel (1661- 1706): Medicinal Plants of the Philippines in the 1700s’. They spoke about the historical significance of Kamel’s manuscripts, now held in the Natural History Museum and the British Library, and how indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants influenced global knowledge during the colonial period.

In July more than 30 PHIMCOS members, family and friends travelled to Cebu for the opening on 4 July of ‘Classics of Philippine Cartography from the 16th to the 20th Centuries’, the exhibition at the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) in Cebu jointly sponsored by PHIMCOS and the NMP. The article by Bunny Fabella on page 9 describes the exhibition, as well as the events we enjoyed before and during the grand opening.

On 14 August 16 PHIMCOS members and spouses were invited to visit the Manila Observatory, which is located within the Ateneo de Manila campus in Quezon City. Our hosts were Executive Director Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin, S.J. , Research Scientist Emeritus Dr. Celine Vicente, and Research Assistant Maria Ysabella Y. Gonzalez.

Having welcomed us, Fr. Villarin recounted the history of the Observatory, which was founded in 1865 by Fr. Federico Faura , S.J. as the Observatorio Meteorológico. Initially tasked with weather observations, the Observatory eventually began recording seismic and volcanic events. In 1901, the American c olonial g overnment established it as the Philippine Weather Bureau, but a fter World War II the Manila Observatory ceased to function as the Weather Bureau and resumed its operations conducting seismic, geomagnetic, radio physics and (more recently) solar physics research.

We were given a guided tour of ‘ Seeking Light since 1865’ , an exhibition commemorating the 160th anniversary of the Observatory Included in the exhibition a re the original manuscripts of the maps Climate Map Showing Seasons and Rainfall and Mete orological Stations Operated by the Philippine Weather Bureau that were published in 1920 Also in the exhibition were photographs of the Observatory pre- War and post- war and its employees, and the various types of equipment used to observe and measure the atmosphere and climate systems. Our visit concluded with a tour of the facilities, from the instruments on the rooftop of the Main Building to those in the Solar Building

Ano ther event to which PHIMCOS members were invited was ‘The Destruction of the City of Pines’, a n exhibition at the Museo Kordilyera from 3 to 30 September of o ver 80 rare photographs (from the collections of Albert Montilla and Rosario Ortigas, Ricardo Jose and the Ortigas Library) of Baguio City prior to and after World War II . The exhibition commemorated the 80th anniversary of the end of the war, when articles of surrender were signed by General Tomoyuki Yamashita in Baguio on 3 September, 1945.

CARR, Captain Robert.

Our Covers

A Chart of the China Sea and Philippine Islands

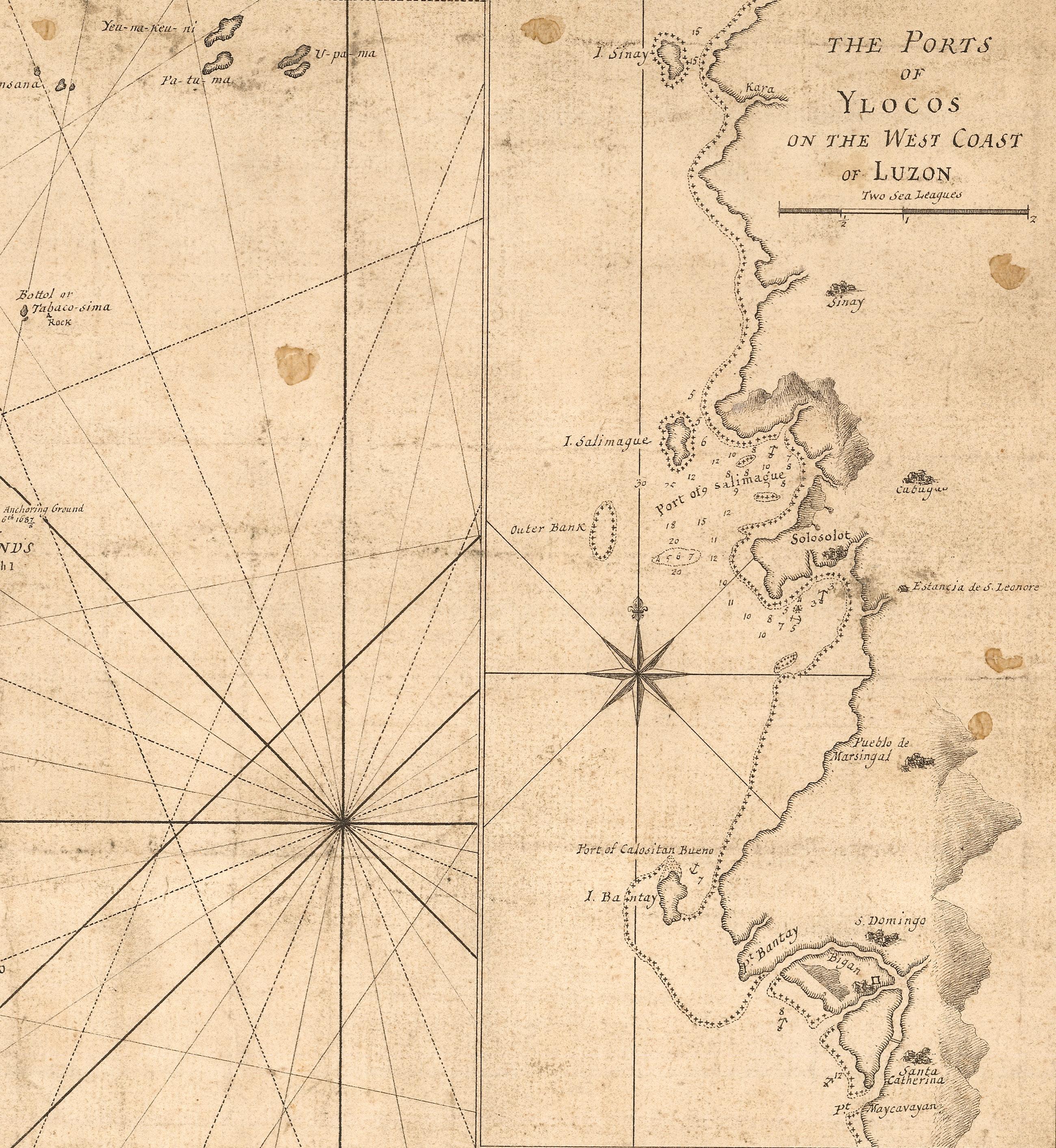

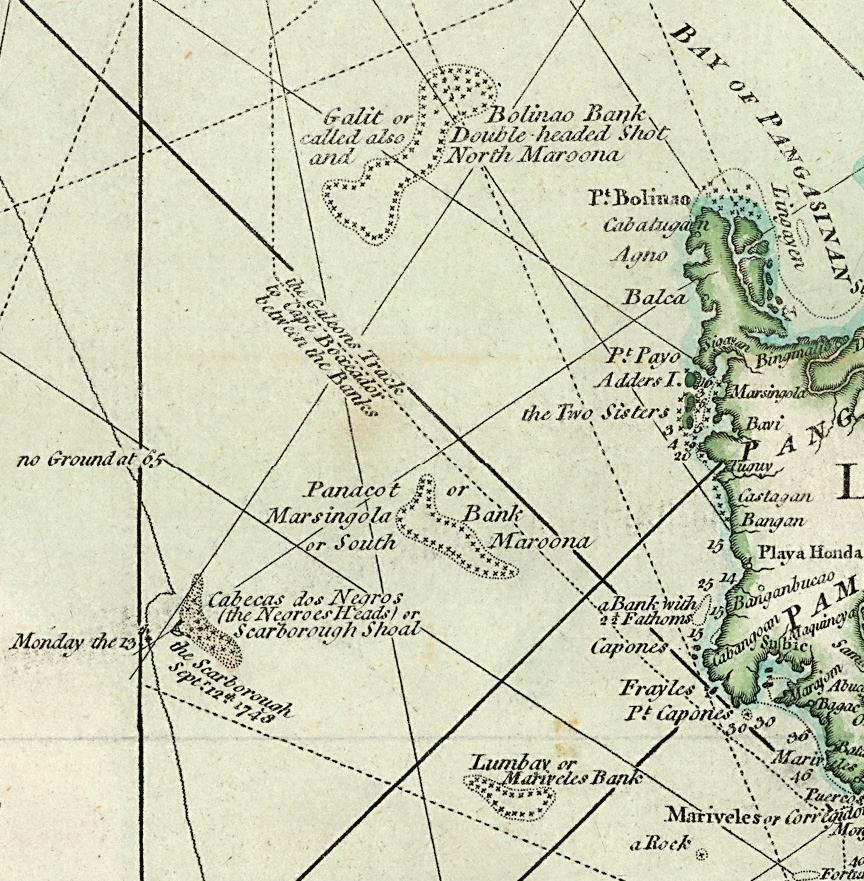

OUR FRONT COVER shows A Chart of the China Sea, and Philippine Islands, with the Archipelagos of Felicia and Soloo, Shewing the whole Tract Comprized between Canton and Balambangan, with the Soundings, Shoals, Rocks, & ca. Composed from an Original Drawing Communicated by Cap.t Robert Carr and Compared with the Map of Pedro Murillo de Velarde, Engraved at Manilla in 1734, as well as with the Surveys of Several British Navigators There are two insets: The Ports of Ylocos on the West Coast of Luzon and The Bay of Subic on the West Coast of Luzon.

This chart, which measures 75 cm x 60 cm, was first published by Robert Sayer and John Bennett on 20 April, 1778. With a revised imprint dated 12 May, 1794, it was re-issued by Robert Laurie and James Whittle, the successors to Sayer & Bennett. The map was then included in the collections of charts titled the East India Pilot or Oriental Navigator, published by Laurie & Whittle in a number of editions (with variations to the title) from 1797 to c.1818

The title states that the chart is based on the 1734 Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica delas Yslas Filipinas by Pedro Murillo Velarde, but with amendments and additions communicated by Captain Robert Carr and from surveys by ‘Several British Navigators’. From 1757-58 onwards Carr made nine voyages to the Far East with the East India Company, the last of these as captain of the East Indiaman Barwell in 1784-85(1) .

One notable addition is the small vignette of ‘the Spanish Galeon Nostra Señora de Cabadonga (sic) taken by the Centurion June the 20th 1743’ , shown above ‘Cape Espiritu Santo of a moderate height with several round Hummocks’. This refers to the battle in which Commodore George Anson seized the Manila galleon Nuestra Señora de Covadonga on his circumnavigation of the world during the War of the Austrian Succession.

Another interesting detail is the ‘Track of the Royal Captain towards Balambangan in December 1773‘, which begins south of the

mouth of the Pearl River and can be followed southwards past Scarborough Shoal until it stops to the west of southern Palawan with a note stating ‘the Royal Captain Strikes at ½ past 2 AM Saturday the 18th‘. The chart also shows the ‘Track of the Royal Captains Longboat to Balambangan‘. The Royal Captain was an East Indiaman which struck an uncharted reef 76 km west of Palawan; the ship sank, but all six passengers and 99 crew survived the wreck bar three seamen who had got hold of some barrels of arrack and ‘were so intoxicated with liquor that they could not get them away‘ (2)

Many of the names that appear on the Murillo Velarde map have been changed or anglicised ‒for example, La una hermana and La otra hermana have become ‘the Two Sisters’, and Isla de Culebra is ‘Adders Island’ – and many new names and maritime hazards such as banks, rocks and shoals have been added. To the west of Luzon four shoals are shown: ‘Galit or Bolinao Bank called also Double-headed shot and North Maroona; ‘Panacot or Marsingola Bank or South Maroona’; ‘Cabecas dos Negros (the Negroes Heads) or Scarborough Shoal’; and ‘Lumbay or Mariveles Bank’ (see detail on back cover). South of ‘Mariveles or Corregidor’ and the entrance to the Bay of Manilla, Fortune island is described as ‘High & Rocky’, the ‘Y a. de Cabras or Goats I.’ as ‘Flat & Rocky’, and the island of Luban as ‘very High’.

The Batanes Islands have the name ‘Bashee Islands’ given to them by William Dampier when he visited, with to the east of Grafton Island ‘Dampier’s Anchoring Ground Augt. 6th 1687’. ‘Anson’s Pass’ is shown between the islands of Orange, Grafton and Monmouth, together with a note ‘to the Westward of these are Several unknown Islands’. Below the South Point of ‘Tayouan or Formosa Island’ are the ‘Vela Rete Rocks as high as a Ships Hull but surrounded with Breakers on all Sides’, with to the west of these ‘a Rock according to Mr d’Apres de Mannevillette’. Shown to the northwest of the ‘Babuyanes and Batanes Islands’ is a ‘Rock above Water according to the First Dutch Charts’.

Surprisingly, the original working manuscript for this chart has survived. It is one over 200 manuscript charts comprised in the archive of the maritime chart publisher Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson. The whole collection, which covers the last quarter of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century, has been catalogued, digitised and published in three volumes by Altea Gallery and Daniel Crouch Rare Books.(3)

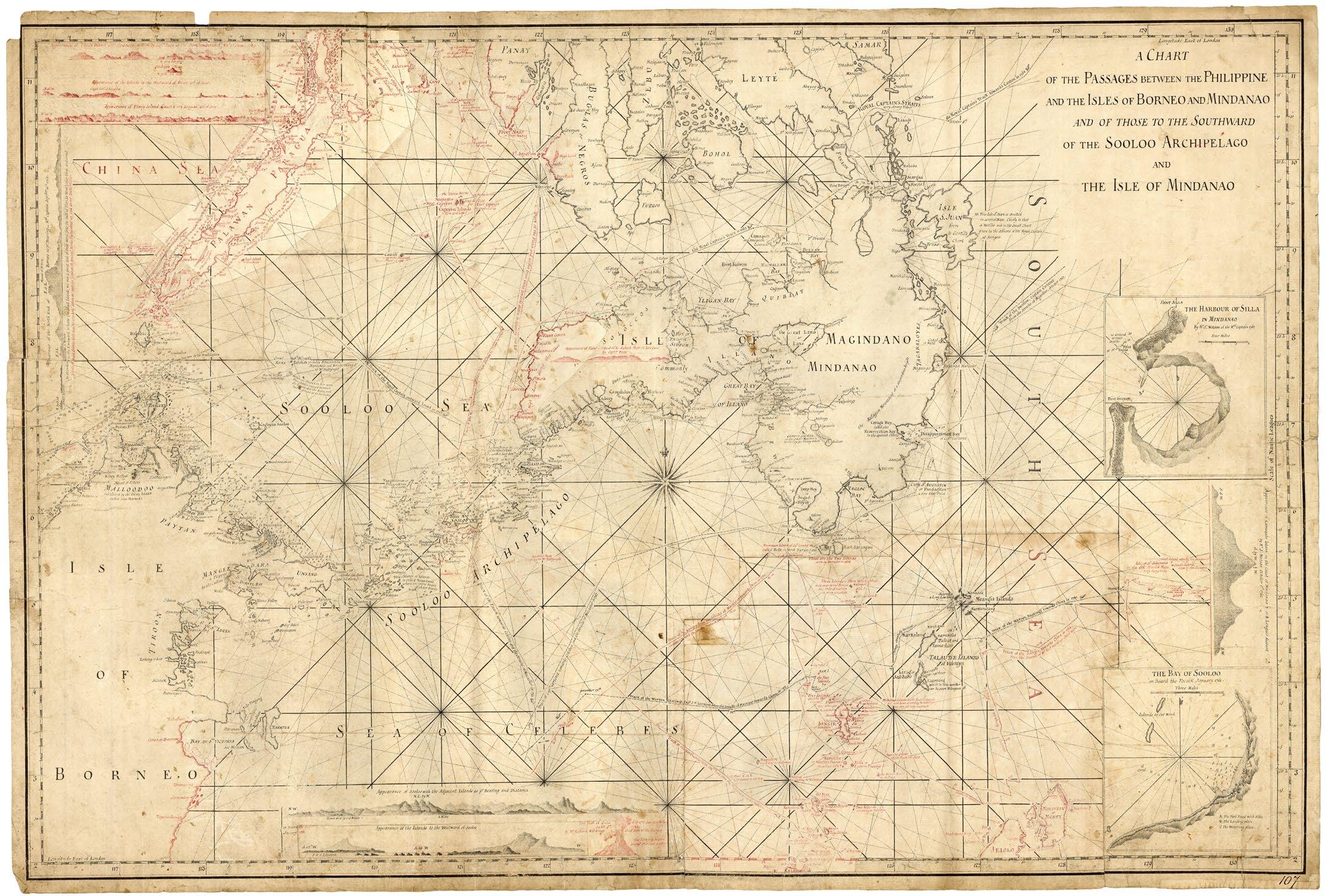

Some of the working manuscript charts in the archive show extensive corrections, updates and revisions made in red pencil. For example, on the manuscript of A Chart of the Passages between the Philippine and the Isles of Borneo and Mindanao and of those to the Southward of the Sooloo Archipelago and the Isle of Mindanao, most of Palawan and north Sulawesi have been redrawn, as well as parts of the coasts of Panay, Negros, Mindanao and Borneo. Many islands

and descriptions have been added, along with an inset of coastal views of Panay; the tracks of the Pocock and Griffin, the Northumberland, and the Ganges; and an image of the ‘Peak of Siao’, a smoking volcano. In 1794 Laurie & Whittle published the chart with all of these changes incorporated

There are no annotations in red pencil on the Robert Carr manuscript; all the geographical and nautical details on the manuscript chart have been copied accurately by the engraver of the copper plate. However, the published chart shows significant changes to the lettering. This is most visible in the title, which has different fonts, spacing and punctuation from the manuscript draft ‒ notably the insertion of the word ‘with’ in the last line. Indeed, across the printed chart all of the lettering is neater and better spaced than on the manuscript

A Chart of the Passages between the Philippine and the Isles of Borneo and Mindanao manuscript chart from the archive of Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd. (image courtesy of Altea Gallery and Daniel Crouch Rare Books)

the

(

A Chart of

China Sea and Philippine Islands, with the Archipelagos of Felicia and Soloo, manuscript chart from the archive of Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd.

image courtesy of Altea Gallery and Daniel Crouch Rare Books)

From the late-17th century until the end of the 19th century, merchant ships seeking safe sea passages from Europe to India, China and Japan via the China Seas, the islands of Indonesia or the coasts of the Philippines largely relied on charts produced by commercial chart publishers in London These firms dominated the growing demand for accurate charts of the eastern seas, and competed with each other.

The charts came to be known as ‘blueback’ charts because of the greyish-blue or royal blue ‘manilla paper’ used to strengthen the unbound charts, which was originally made from abacá or ‘Manila hemp’ But despite their sturdiness, most of these charts are rare today, partly because of the ravages of time, climate, insects, fire, water, war and shipwrecks, but also because it was the active policy of shipowners to destroy charts when they became out-of-date

At the turn of the 19th century there were half-adozen commercial blueback chart publishers in London, of which four were dominant, especially for the production of charts of the East Indies: Sayer & Bennett / Laurie & Whittle; William Heather / J. W. Norie; Steel & Goddard; and Moore & Blachford / James Imray.

In 1795 Alexander Dalrymple was appointed as Hydrographer to the Admiralty Board. The Hydrographic Office began to produce its own charts in 1800, many of which were at first editions of those produced by Dalrymple for the East India Company (EIC) In order to supply the Admiralty with the best available charts, before his death in 1808 Dalrymple helped to set up a chart committee to examine over 1000 charts

References

bought from the commercial chart publishers, of which 200 were recommended for use.

The later Admiralty charts look quite different from blueback and EIC charts because Royal Navy captains often sailed to remote parts of the world and required large-scale charts that were unadorned but with the details finely engraved. In contrast, merchant mariners usually sailed along familiar routes in open sea, and continued to prefer the smaller-scale blueback charts with heavy coastlines and large-scale plans of ports (included as insets) that continued to be published throughout the 19th century.

However, in 1904 legislation mandated the use of Admiralty charts by all vessels sailing under the British flag. As a result, Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd. was established that year through the merger of the successor firms of the original blueback chart publishers (4)

The archive is a testament to the extraordinary output of the firms that would eventually come together as Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson It contains not only over 200 manuscript charts but also 24 atlases, catalogues, sailing directions, oil paintings, associated ephemera, Lord Nelson’s favourite chair, and even one of only two known copper plates for a chart by James Cook The survival of the archive is remarkable, especially as many of the firm’s papers were destroyed in 1941 when its offices at 123 Minories were gutted by incendiary bombs during the Blitz. The collection is now being offered for sale en bloc, although currently subject to a temporary export ban by the U K government in case any British institution should be able to acquire it

1. Anthony Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers 1600-1834, The British Library, London, 1999, p. 135.

2. Franck Goddio et al., Royal Captain: A Ship Lost in the Abyss, Periplus Publishing, London, 2000, p. 14.

3. The Art of the Chart: The Archive of Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Altea Gallery Limited and Daniel Crouch Rare Books Ltd, London, 2025.

4. For a comprehensive history of the blueback chart publishers see:

‒ Elena Wilson, The Story of the Blue Back Chart, Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd., London, 1937.

‒ Susanna Fisher, The Makers of the Blueback Charts: A History of Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson Ltd, Regatta Press Limited, Ithaca, New York / Imray, Laurie, Norie & Wilson, Ltd , St. Ives, 2001

‒ Daniel Crouch, ‘The history of the blueback chart’, in The Art of the Chart (op. cit.) Vol. 3, pp. 169-190.

PHIMCOS Travels to Cebu in July 2025

by Maria Paz K. Fabella

JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE once said that collectors are happy people; and there were no happier collectors than the members of PHIMCOS who descended on Cebu City in July 2025 to attend the opening of the exhibition Classics of Philippine Cartography from the 16th to the 20th Centuries. The exhibition, a joint collaboration between the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) and PHIMCOS, is on display at the NMP‒Cebu until the end of January 2026.

Over 30 members of the Society, with family members and friends, were present at the formal opening held on July 4, 2025. And, as with most PHIMCOS outings, the Cebu excursion included other activities that complemented this main event

The 1730 Jesuit House Museum

Our first membership activity was a cocktail reception on the evening of July 2 hosted by international conservator Ephraim ‘Eddie’ Jose at the 1730 Jesuit House Museum located at 26 Zulueta Street in the Parian District of Cebu. The district was a part of the old city designated by the Spanish colonial administrators to house the city’s Chinese and Filipino-Chinese population. Also known as the ‘Museo Parian sa Sugbu’, the Jesuit House was the Order’s provincial headquarters before the Jesuits departed from the country in 1768. It is estimated to be 280 years old and may be the oldest ‘dated’ house in Cebu or even in the country.

The Jesuit House sits inside a warehouse property belonging to Ho Tong Hardware, once the largest hardware chain in Cebu, owned by the family of Jaime Sy. The importance of the house was discovered when Sy, browsing through a book on old Jesuit houses by Fr. William Repetti, S.J. ‒ a seismologist who also gathered data about the history of the Jesuits in the Philippines ‒ recognized a picture of the family warehouse. There is a carved plaque in the house that bears the inscription ‘Año 1730’, and the museum anteroom displays three original stone seals of the Jesuit Order along with Certificates of Appreciation given to the Sy family by Pope Francis I. On arrival, the PHIMCOS group was treated to a most informative lecture on the history of the Jesuit House given by Jimmy Sy.

A tour of the museum revealed a beautiful, wellpreserved structure of stone, narra wood and molave wood. A short walk through the warehouse brought us to a ground-level exhibition on the Parian District’s commercial history from the

Inside the Jesuit House Museum (above) with stone seals and certificates of appreciation (left)

16th century to the present day. There are also displays of old coins and ceramic ware found during excavation of the building’s foundations. This was followed by a visit to the House proper, which showcased its original beams, walls and flooring alongside small eclectic collections of early-20th century analog communication devices.

We rounded out our visit to the 1730 Jesuit House with a simple yet delicious merienda arranged by our hosts It was an excellent start to what would be an informative trip.

Two museums and a dinner

The following morning, July 3, began with a visit to the BPI Museum at the bank’s main Cebu branch located at the corner of Magallanes and P. Burgos Streets in Barangay Sto. Niño. The Cebu office was the bank’s third branch outside Manila, established in 1924 (after Iloilo in 1897 and Zamboanga in 1916). The building was designed by Juan Marcos Arellano around 1938 and its construction was completed by Agustin Montinola Jereza in 1941. In 2024 it was designated an Important Cultural Property (ICP) by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and the NMP.

The museum’s collections of numismatics and bank memorabilia are impressive. The exhibits

of PHIMCOS and our BPI hosts at

straddle two wings of the old building, with the fully-operating BPI branch ensconced in the middle. In one wing are displays of old bank equipment – vaults, safes, teller cages, old stock certificates and bank ledgers, among others ‒and a historical explanation of the building and banking in the Philippines.

We also had the opportunity to view the museum’s prized collection of antique gold coins and valuable numismatic collectibles stored in their dedicated vault, including the Php 100,000 banknote issued by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in 1998 to commemorate the centennial of Philippine independence, acknowledged as the world's largest legal tender banknote.

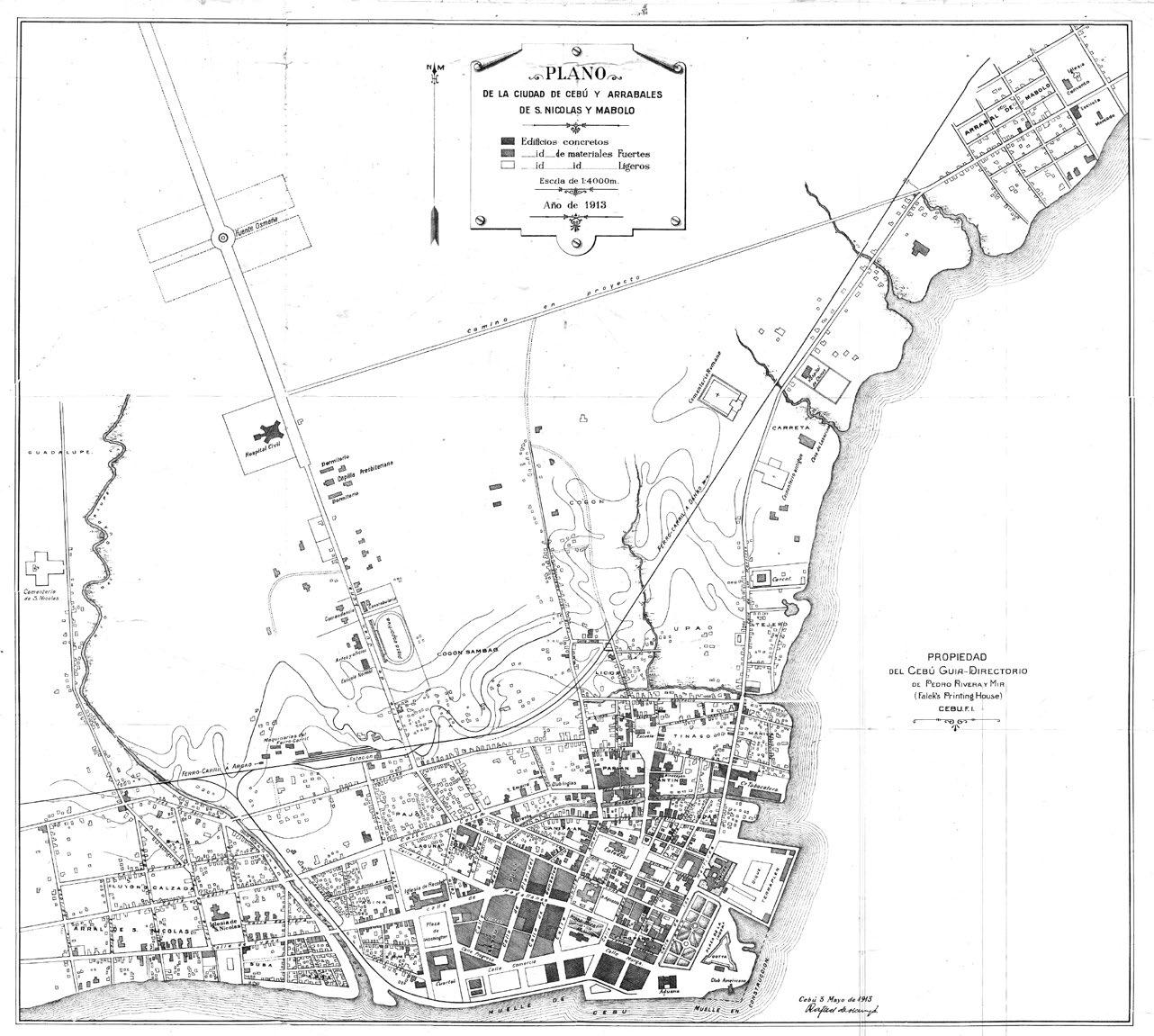

˂ Plano de la Ciudad de Cebú y Arrabales de S. Nicolas y Mabolo by Rafael de Ocampo, 1913 (image courtesy of Dr. Jose Eleazar Bersales)

Members

the BPI Museum Cebu

In the second wing, on the other side, are showcased items and bank artifacts which trace the story of Philippine monies, along with displays of old bills and coinage from colonial times and various periods of the Republic. A reconstructed cashier’s teller cage greets visitors at the entrance. For us the best exhibit was in a small room at the rear of the museum exhibiting maps. There we saw a 1897 Mapa General del Archipiélago Filipino and (of particular interest to the PHIMCOS visitors, none of whom had seen it before) a Plano de la Ciudad de Cebú y Arrabales de S. Nicolas y Mabolo dated 1913. The map, by Rafael de Ocampo, was published in the Cebú Guia-Directorio de Pedro Rivera y Mir printed by the Austrian immigrant David Leopold Falek

After the BPI Museum we stopped by the Cross of Magellan and the Basilica Minore del Sto. Niño de Cebu, before continuing on to the Sugbu Chinese Heritage Museum across the plaza. The museum, established in 2013 and situated in the Gotiaoco Building on M.C. Briones Street, consists of two floors dedicated to the history of the Chinese community in Cebu. The museum was the first in Cebu and outside of Manila to focus on this community. The main attraction is a detailed model of a 12th century Chinese junk assembled using a 1:6 ratio and positioned within a recreated Chinese port.

The Gotiaoco Building itself was declared a heritage structure by the City of Cebu in 2012 and underwent restoration work in 2016-19. It was built in 1914 during the American Period by Manuel Gotianuy, son of Don Pedro Gotiaoco, who named it after his father. According to information plaques in the museum, the original building was Neoclassic in design, irregularly shaped, and consisted of three levels. An arcade surrounded the ground floor, and the edifice was topped by a parapet in a style that recalls the European Renaissance. The original building is also believed to have housed the first elevator in Cebu, the remains of the original shaft of which form part of the exhibits.

The day was capped with a sumptuous dinner hosted by Andoni and Doreen Aboitiz at the Casino Español de Cebu on Ranudo Street. Established in 1920, the club is still a popular recreation and dining destination for its members and their friends. Our members dined on a buffet which featured a Salad of Roasted Vegetables with Cashew Nuts, Lapu-lapu Pescado a la Veracruzana, Salade Niçoise, Paella Valenciana and, of course, the unforgettable sight of two steaming lechons from Zubuchon (courtesy of Marga and Joel Binamira), with desserts to round out the meal.

Model of a Chinese junk at the Sugbu Chinese Heritage Museum

The National Museum of the Philippines‒Cebu

PHIMCOS members at the preview (from left): Yvette Montilla, Jenny Burger, Mark Lim, Fed and Peter Geldart, Marga Binamira, Jimmie González, Albert and Chari Montilla, Jonathan and Vicky Wattis, and Connie González

Preview and Grand Opening

On the morning of July 4, PHIMCOS members, friends and members of the press were invited to visit NMP-Cebu in order to have an exclusive preview of the Classics of Philippine Cartography exhibition ahead of its formal opening that evening.

NMP‒Cebu occupies the historic Aduana, the former colonial Customs House designed by the American architect William Parsons and built in 1910. Damaged during World War II and subsequently used as government offices, following earthquake damage in 2013 the building was restored and converted into a museum six years later.

The exhibition is displayed in the museum’s Gallery 4, a large, well-lit space with high ceilings ideal for viewing the maps. On view are 87 impressive objects ‒ lent by 12 members and friends of PHIMCOS and nine institutions in the Philippines, Spain, England and the Netherlands ‒ that highlight the cartographic history of the Philippine archipelago from the early-16th to the mid-20th century. The majority of the exhibits are original maps, sea charts, city plans and books However, in order to present a comprehensive view of Philippine cartography across five centuries, the exhibition also includes highquality reproductions of a number of especially important maps

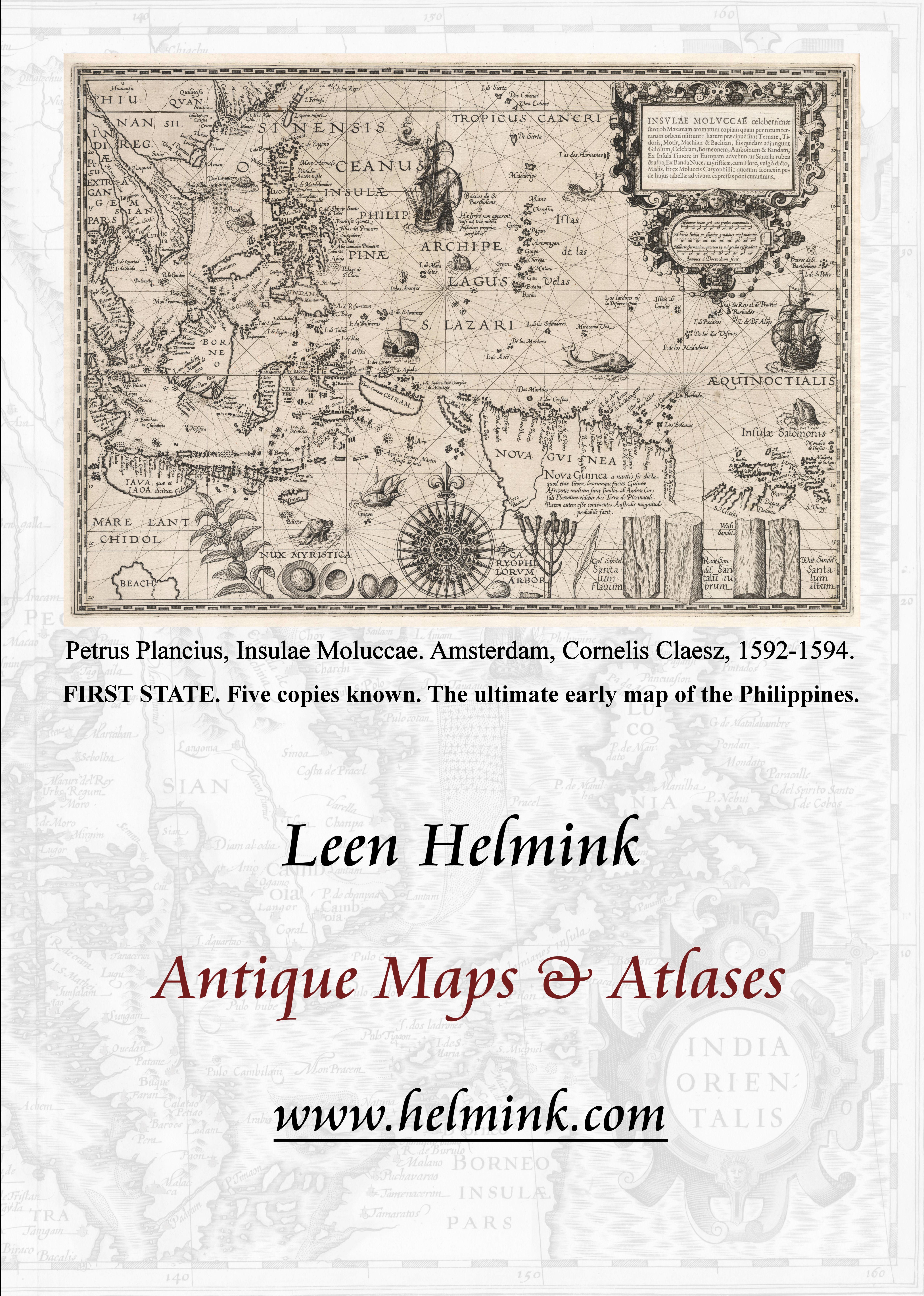

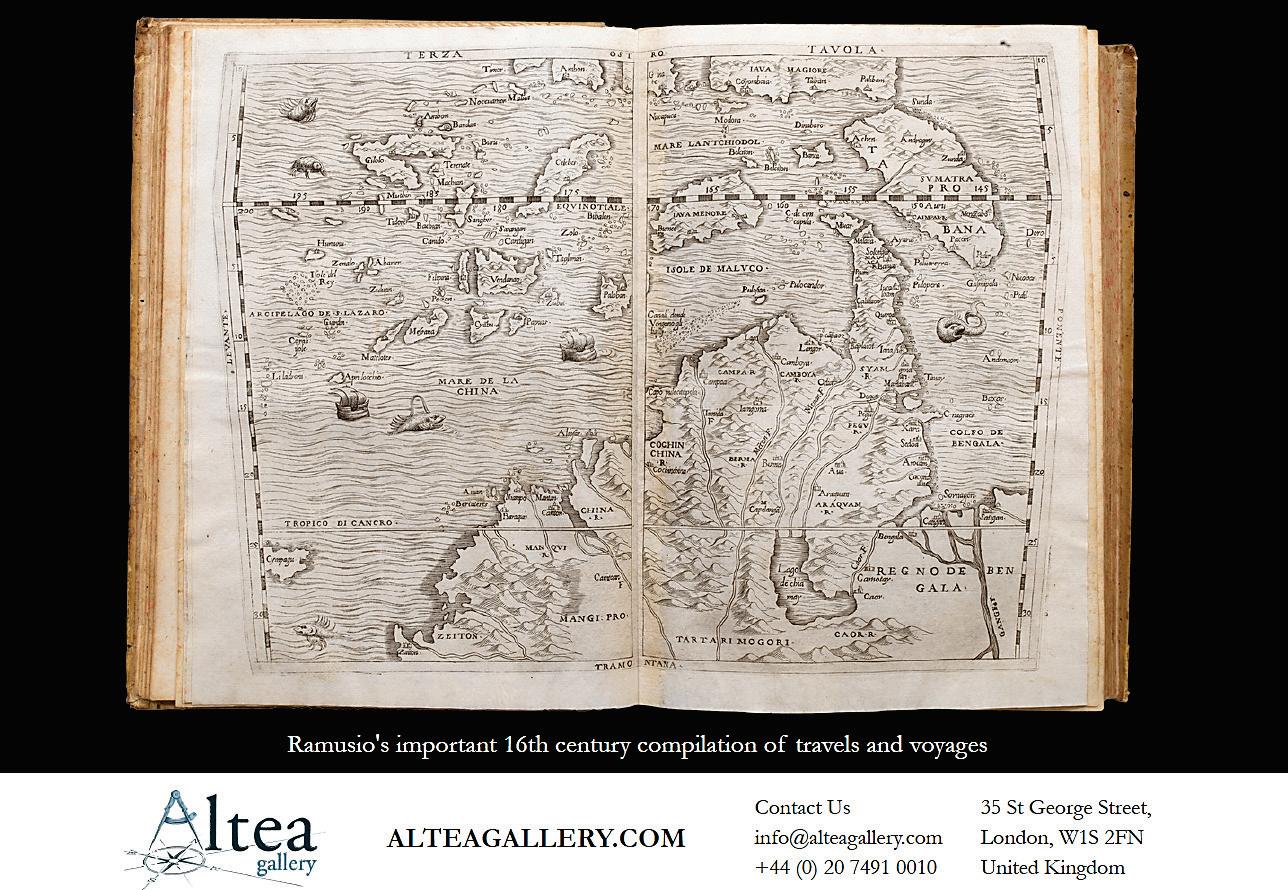

Maps in the exhibition include one of Cebu with the island of Mactan by Antonio Pigafetta, who chronicled Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage through the Visayas in 1521; the English edition of the famous ’Spice Map‘ produced by the FlemishDutch mapmaker Petrus Plancius in c.1594; the first miniature maps of the Philippines; and both editions of Terza Tavola by Giacomo Gastaldi, the first map on which the name ‘Filipina’ appears.

During the preview, Marga Binamira and Peter Geldart led a coterie of representatives from the press and media on a lecture tour of specific maps and displays. The viewers were particularly interested to see the charts, published by Robert Dudley in Florence in 1646, that use the name ‘Mare delle Filippine’ (Sea of the Philippines) for that portion of the South China Sea now officially

Jeremy Barns, Marga Binamira, Andoni Aboitiz and Jimmie González cutting the ribbon

designated as the ‘West Philippine Sea’, and show ‘La Seccagna di Bollinao’ (Shoal of Bolinao), the reef later named ‘Panacot’, ‘Bajo de Masinloc’ or the ‘Scarborough Shoal’.

A reproduction of the iconic 1734 map by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde is on display, together with originals of the smaller editions published in 1748, 1749 and 1788, and a number of later editions produced by European mapmakers. As well as European maps, the exhibition shows maps by Asian, Filipino and American cartographers, some of which are being exhibited in the Philippines for the first time.

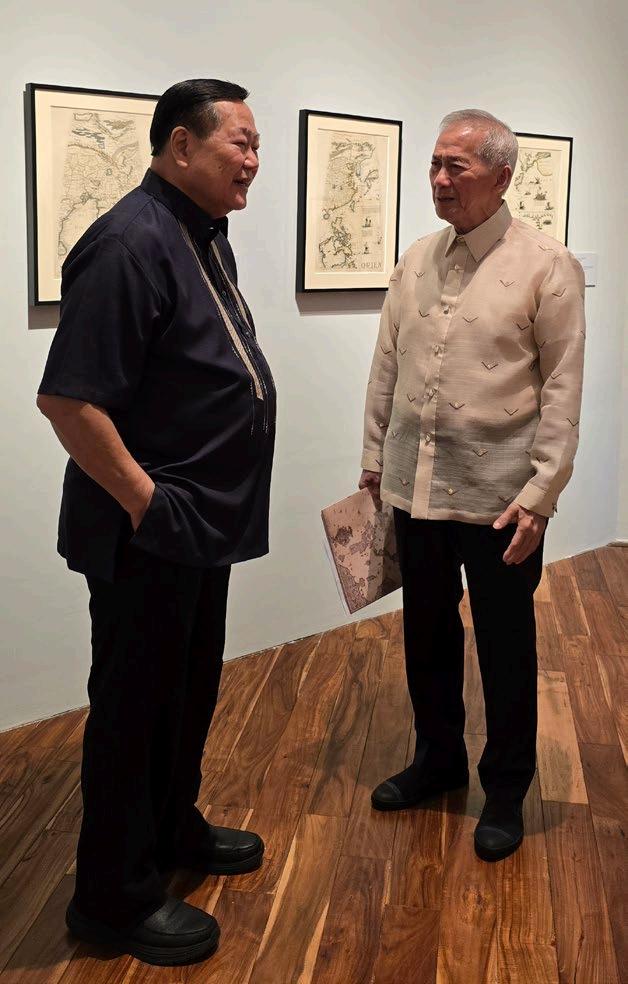

At 5:00 p.m. the formal opening of the exhibition and ribbon cutting took place on the second floor gallery. Introduced by Ma. Cecilia Cabañes of the NMP‒Cebu, speeches were given by NMP Director General Jeremy Barns, PHIMCOS President Jaime González, and the exhibition’s co-curators Andoni Aboitiz and Marga Binamira. Special guests included H.E. Miguel Utray, Ambassador of Spain to the Philippines; Alvaro Garcia Moreno, First Secretary for Culture, Scientific and Administrative Affairs at the Spanish Embassy; Department of Tourism Undersecretary Myra Paz Valderrosa-Abubakar; Supreme Court Justice (retired) Antonio Carpio; Dr. Jose Eleazar Bersales, Head of the NCCA National Committee on Museums; and National Artist for Literature Dr. Resil Mojares. The event

was very well attended, and the stream of visitors continued to enjoy the drinks and dinner (above) provided in the museum’s foyer until well into the evening.

Detailed information and images of the objects in the exhibition can be found in the catalogue, which is available from the PHIMCOS website and at the NMP‒Cebu. As well as the contributions from the PHIMCOS curators and lenders, the exhibition would not have been possible without the dedication and hard work of the NMP teams in Manila and Cebu. We thank all of them for their efforts to ensure the success of the exhibition.

On July 5 the exhibition opened to the public, and many of the previous day’s visitors returned for a more leisurely viewing of the maps. Some PHIMCOS members also took advantage of this most successful trip to visit other sights in Cebu, including Fort San Pedro, Casa Gorordo, Sirao Flower Garden, Cebu Taoist Temple, and the panoramic view of the city from TOPS Cebu

At the opening (left) Andoni Aboitiz, Dr. Jose Eleazar Bersales, Marga Binamira and Dr. Resil Mojares; (right) Justice Antonio Carpio (Ret.) and Jimmie González

Addendum to ‘The Map That Never Was’

IN ISSUE No. 17 of The Murillo Bulletin the article titled ‘The Map That Never Was’ discussed Alexander Dalrymple's unpublished Chart of the Philipinas. The author acknowledged the many contributions to the article made by Andrew S. Cook, and Dr. Cook has now clarified and corrected a number of points:

“ Like you, I have difficulty in getting beyond thinking of Draper as the recipient of the letter. I have been looking for a connection between Robert Orme and Sir William Draper, geographical or otherwise, but without success. The deferential tone of the start of the letter, and of its subscription, suggests more than the standard formality of letters between professional equals.

I do no t think we should doubt the letter was indeed sent and received, even though it looks in pristine condition, without folds. It was most likely rolled with the map of Bengal by William Bolts which accompanied it, with the addressee’s name on the outer packaging. ‘Envelope’ is here, I think, an anachronism: envelopes as separate folded cover sheets, were a mid- 19th century invention, dating from the discontinuation of the practice of charging postage by the sheet, letter or cover. In the 18th century letters were standardly folded twice, ends inward, wax- sealed at the join, and the addressee written on the blank back panel.

At the foot of the first page of the letter, ‘N 17 & 16’ refers to section 16 ‘Magindanao’ and section 17 ‘Philipinas’ of Dalrymple’s list of his private collection of manuscript charts and plans, a list which he had issued in General Introduction to the Charts and Memoirs in 1772, where it is preceded by a three- page (pp. viii- xi) discussion of his ‘work in progress’ in that year, and of his sources, including work on his chart of the Philippines. This could provide a useful intermediate statement between the D’Après de Mannevillette letters and the Maggs/Crouch letter. This 1772 discussion was omitted from the second (1786) edition of GICM, the occasion for a chart of the Philippines from Dalrymple’s own sources having passed with his new 1779

scheme for a series of coastal charts for the whole East Indies navigation.

By the way, your reference to ‘a Separate Work not yet published’ on page 16 of General Introduction to a Collection of Plans of Ports (1783) is not to the Philippines but to a proposed chart of the Natunas and Anambas. Dalrymple’s note is keyed by the bold letter ’S’ to entries for plans of those islands in the list of printed plans which follows it.

Dalrymple’s interest in publishing charts of the Philippines enjoyed a mild revival in 1781, with progress on the unfinished chart of Luzon in September. Two of the four charts bear the sequence of marginal dots for users to draw radial lines, introduced by Dalrymple to his plans in 1780 or 1781, which implies a temporary recurrence of interest on his part.

I had wondered why the three dated proof charts of the Philippines bear 1775 dates, and have come to the following conclusion. The Panay chart of January 1775 is, I think, to be associated with the Philippines number three of Plans of Ports of 1774- 75. The two charts with April dates (as well as the undated chart) represent Dalrymple tidying up his affairs before departing for Madras. He had known from March that he was due to accompany George Pigot in [ the East Indiaman] Grenville, sailing at the end of April, and I think he may have wished to preserve his copyright in the charts by printing proof copies with a full ‘Published according to Act of Parliament …’ imprint, envisaging future work on them.

It is interesting that, though Dalrymple did no t carry his Philippines project significantly forward after his return from Madras in 1777, he kept these proofs carefully together for the rest of his life. Your excellent illustrations show one set going into the Hydrographic Office, and numbered sequentially in the Original Documents series as v50 to v53 on Bb2. Another set he included in the extensive collection of his printed charts which he sent to Francis Beaufort in 1805 and is now in the Library of Congress. ”

Elizabeth Keith: Pictures of the Philippines in 1924

by Jonathan Wattis with

contributions from Peter

Geldart

IN 1924 the talented young Scottish artist Elizabeth Keith visited the Philippines, where she painted vivid and joyful scenes of places and people. Fortunately, a few of these were made into attractive woodblock prints and etchings in small, limited editions of which a number survive. These include images of her visits to Manila, Baguio, Zamboanga and Sulu. What makes her story particularly interesting is that, as a young woman travelling to remote places, she was able to produce fine quality pictures of her unique vision as a record for posterity. A number of books and catalogues about Elizabeth Keith have been published, and exhibitions of her work were held in Japan, Korea, China, Hong Kong, Britain, Paris and the United States. However, little has been written about her visit to the Philippines, and the prints that survive from that time are scarce.

To begin, Elizabeth Keith was born in Macduff, Aberdeenshire, Scotland on 30 April, 1887. With her large family she moved to London, where she went to school and spent most of her young life. In 1915 she travelled to Japan, intending to stay for a short holiday with her elder sister Elspet and her husband J.W. Robertson Scott, who were living in Tokyo at the time. Both were engaged in literary careers; Scott was the editor and publisher of The New East, a bilingual EnglishJapanese propaganda magazine published during World War I, and Elspet wrote. In these early days Keith spent much of her time drawing and painting watercolours, although she had had no formal training in art.

Keith had a sparkling character and, influenced by the colour and life of the countries she visited, she was motivated to paint. Initially finding inspiration in the Japanese landscape and people, she said later ’I was prepared for ages of beauty, but I had never dreamed of such colour’. Keith sold her return ticket to England and stayed in East Asia for another nine years. During that time she journeyed throughout Japan, Korea, China and the Philippines, creating sketches and

watercolours. In her travels she met Christian missionaries who enabled her to travel to remote and otherwise barely accessible places, where she recorded the local scenes and customs.

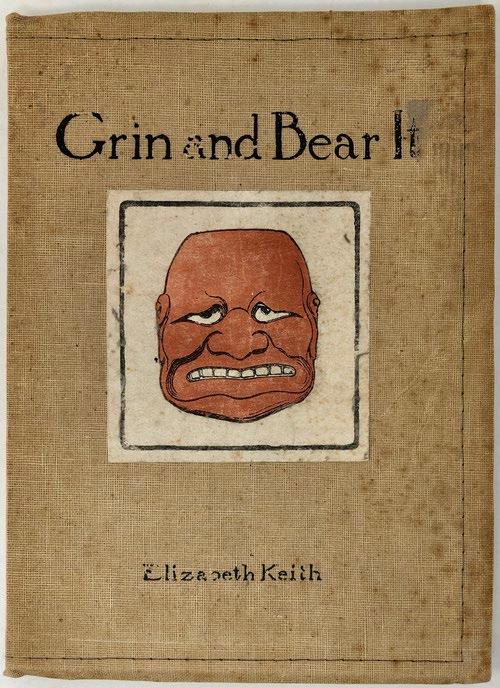

Within her first year in Asia she held an exhibition at the Peers’ Club in Tokyo of caricatures of Japan’s social elite. The show was controversial and enraged a few, but resulted in a limitededition book titled Grin and Bear It published in Tokyo in 1917 by her brother-in-law as a charity fund-raiser for the Red Cross.

Keith first travelled to Korea in March 1919, and held an exhibition of her watercolours of that country in Tokyo later that year. Regarded as the first on Korea to be held in Japan, the exhibition was well attended. Among the attendees was Watanabe Shōzaburō, the pioneering publisher of prints known as shin-hanga (new prints), who

Elizabeth Keith (left) with Kate Bartlett c. 1915; photograph by Y. Shimiozu (image courtesy of Darrel C. Karl)

Grin and Bear It by Elizabeth Keith, Tokyo, 1917 (image courtesy of AOBANE Antiquarian Bookshop)

told her that her pictures would work well as Japanese woodblock prints. He urged her to let him produce a woodblock print of one of her watercolours, East Gate, Seoul, Moonlight. This was a wonderful opportunity, and was the start of a cooperation that would continue until 1939.

The colour, the light, and the sensuous details of the locations of Keith’s drawings translated well into woodblock. Her eye for detail in capturing images of people going about their daily lives was reflected in the prints. The skilled craftsmen of Watanabe’s studio worked with her and taught her about this delightful and skilled art; together they created over 100 prints. As one of only a few Western women shin-hanga printmakers in Japan, Keith was introduced into a world few people would experience: that of the Japanese Hangiya Nakama (the Blockcutters Guild). A separate cherry-wood block for each colour was finely incised after the original drawing, and the prints were then printed layer by layer. Keith spent many days kneeling beside the artisans, watching their skilful work.

Another first came two years later when, in 1921, she held an exhibition of her paintings in Seoul ‒the first by a foreign artist. In a letter to her sister, published in Eastern Windows in 1928, Keith wrote:

My first show of pictures here in Seoul has been an astounding success. Everybody came to it, from the wife of the Governor-General to the school children. By the end of the day the place was redolent of kimtchi! What better testament of Korean interest can there be?

She continued to travel within Japan, with visits to Korea and China, painting subjects in bright colours. Upon first visiting Peking she observed:

The days have been bitterly cold, bright, sunshiny, and dry. Every building stands out clearly in the light; gateways touched with bright green, red, and blue, and the outer wall grey; or temples with bright yellow tiles and walls of red orange. Along the dusty road move strings of camels on their special pathway, passing under wonderful gateways. Who can describe the mien of a camel? Who can portray his pride and lofty contempt as he marches on bearing enormous loads? He is ageless, remote.

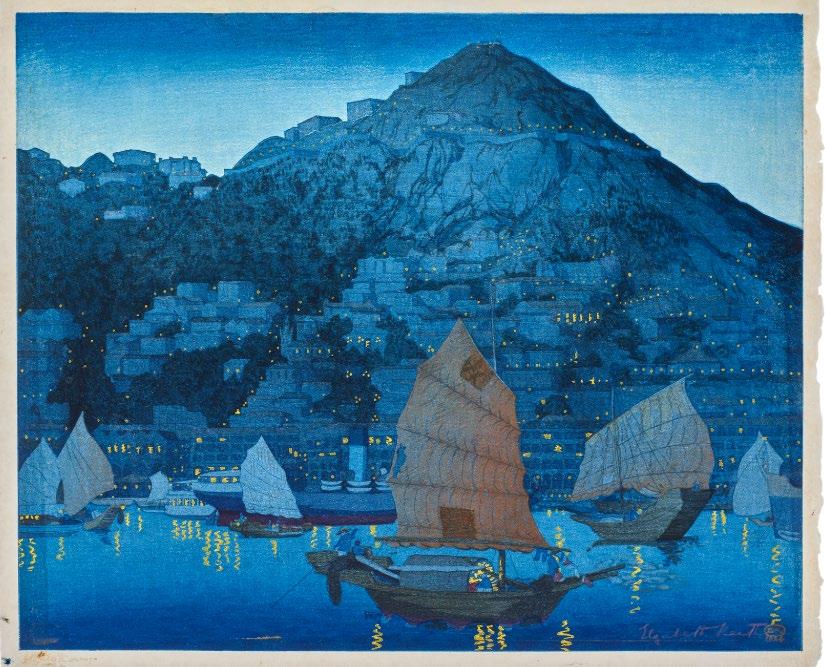

She also visited the cities of Soochow, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and described her impressions:

I take great delight in the shops here. The shopmen are dignified figures and have great courtesy. In each silk shop there are about twenty or more young men serving, with the manners of old-world China. Although we do not understand each other’s language we get on well. Most attractive of all are the painted silk banners, that float at the doorway of every shop and store. The gorgeous golden characters on the banners are lovely in the sunshine.

When I came back to Hong Kong the second time, I thought it the most beautiful place I had ever seen. It is lovely at seven in the morning, but it is best of all at night. In the early morning the sea is deep green, but it changes colour as soon as the smoke of the day rises and shadows the peak. The varied boats in the harbour with their many-coloured, tattered sails, the Eastern figures on their decks, make the whole thing like a dream. Indeed, you might think you were looking at a vision instead of a scene of the workaday world. At night, the wonderful peak, rising sheer out of the water, with the houses built right up its side, made me think of a lighted altar. It was all sparkle with lights gleaming from the moving water-craft, from the shore, and glittering right up to the hilltop.

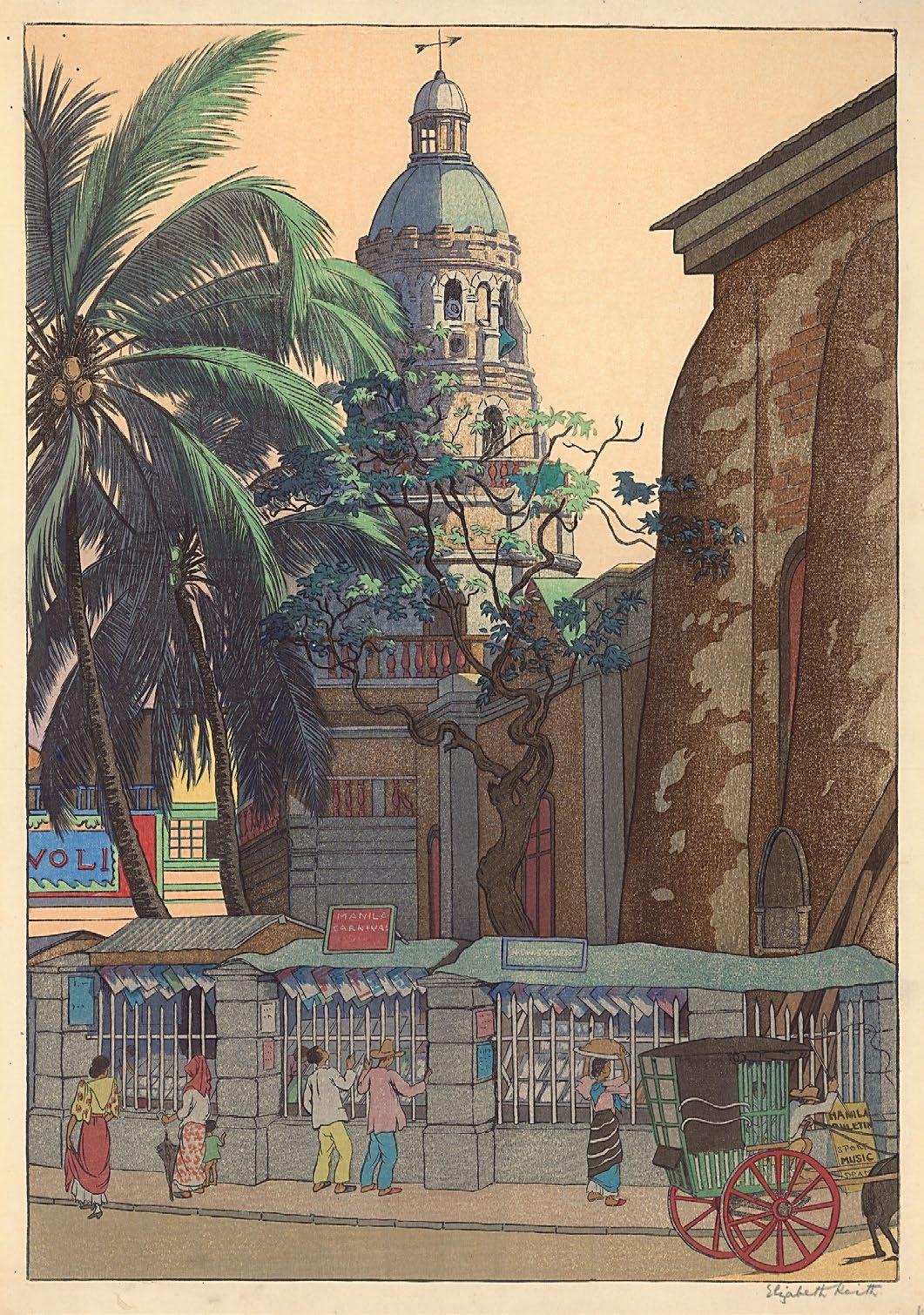

Woodblock prints of Manila: Santa Cruz Church (left) and almsgiving at Santa Isabel Tower (right) (author’s collection)

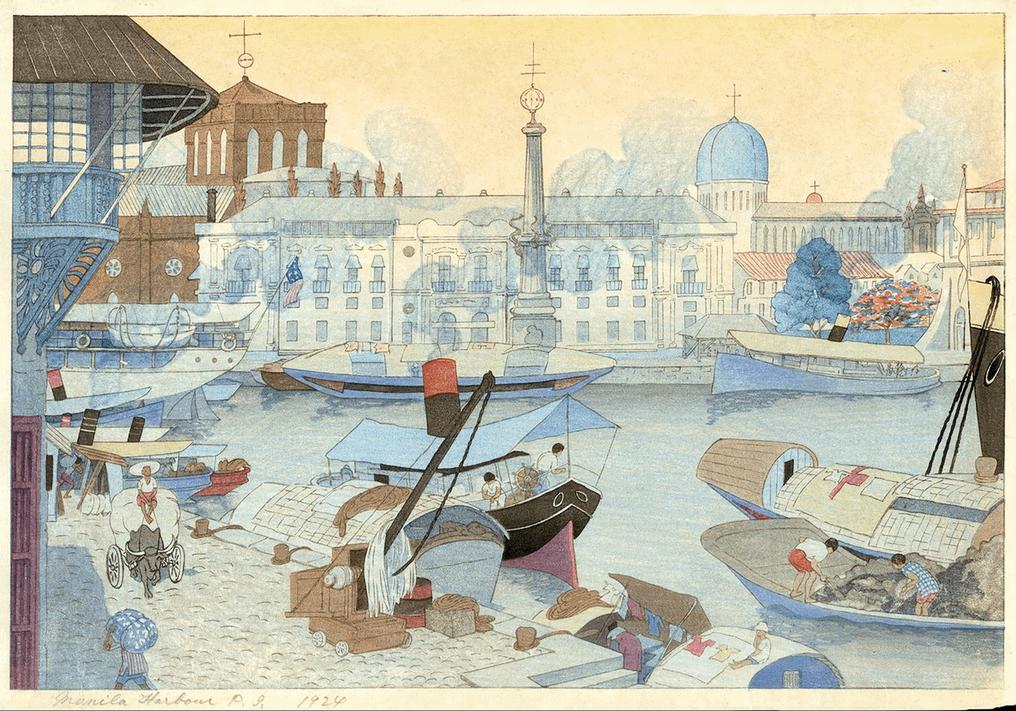

Woodblock print titled Manila Harbour P.I. 1924 (image courtesy of Moonlit Sea Prints)

In Hong Kong she held an exhibition of her paintings; the show was a success, and she made some new friends. The quotations above are from her book Eastern Windows. An Artist’s Notes on Travel in Japan, Hokkaido, Korea, China and the Philippines, published in London in 1928. In the book Keith recounts her travels in East Asia and the Philippines between 1919 and 1924, with details of the places she visited and the subjects she painted. The book was edited by her sister Jessie, and the narrative is based on the letters that Elizabeth had written to her over the years.

Keith enjoyed travelling and painting in China, but to quote the critic Malcolm C. Salaman in his Introduction to Masters of the Colour Print 9: Elizabeth Keith, (The Studio, London, 1933):

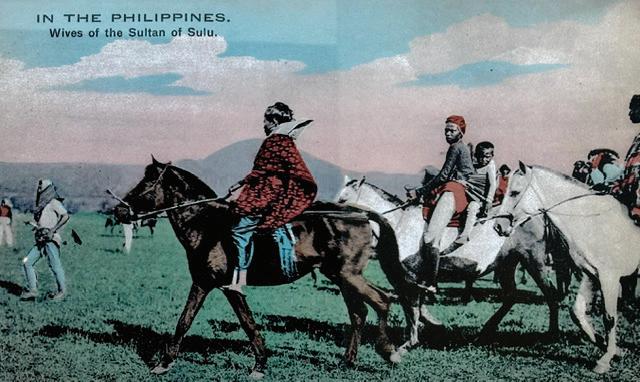

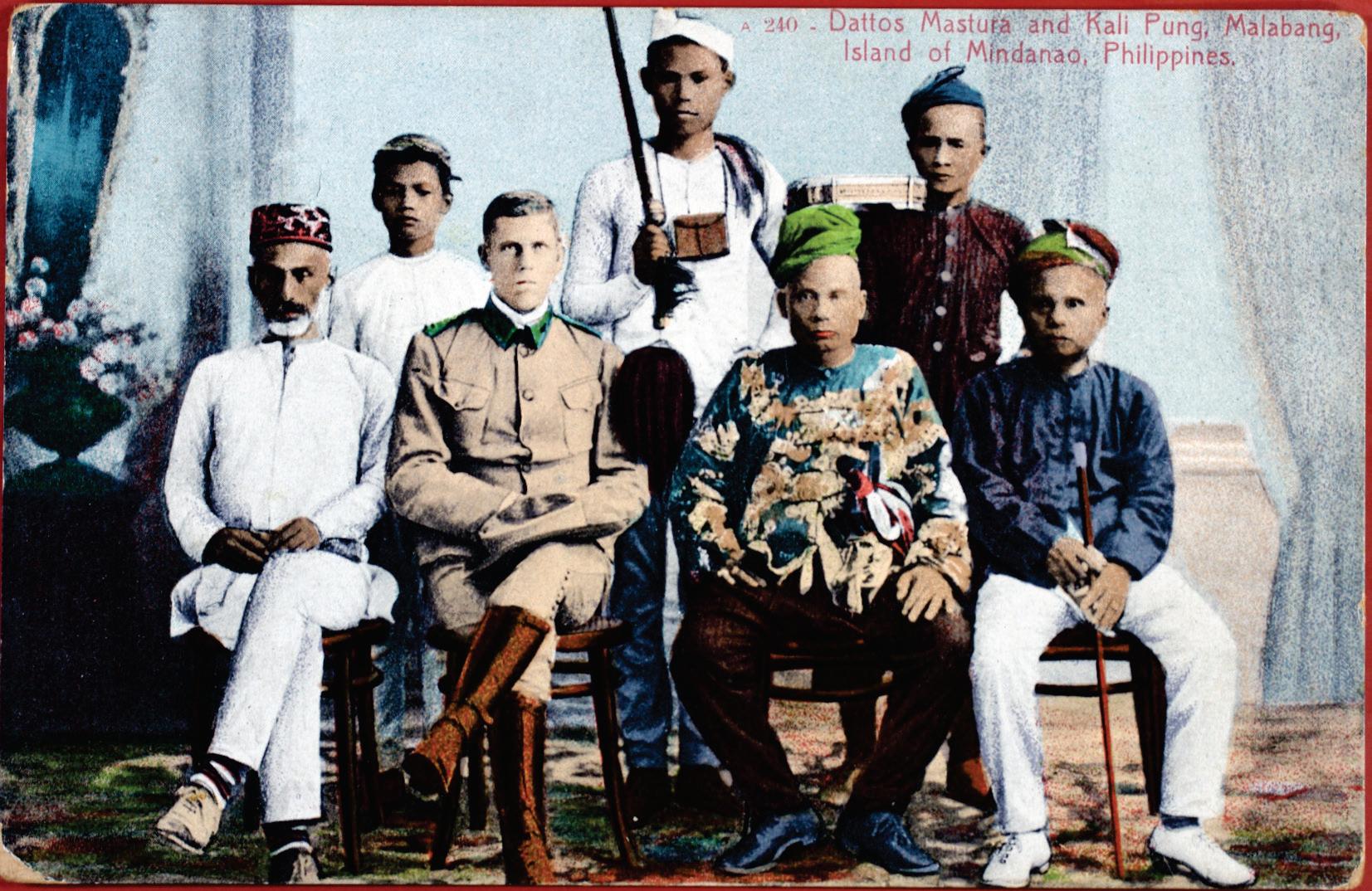

Things were looking threateningly hostile, and the Philippines were suggested as a happy alternative. Her prints being popular in Manila, and the prospect was a new adventure so she promptly decided to go there. She found a variety of new subjects there, for beside the Filipinos, she travelled among some half dozen native races, each segregated on their native islands with differing civilizations, from the beautiful Moros, of Spanish and Muslim traditions, to the Danguet [Benguet] tribesmen in their coloured blankets, living in huts without windows.

Keith arrived in the Philippines in 1924 and noted ‘Manila was even better than I had hoped’. There she painted Santa Cruz Church, a baroque church located in the arrabal (suburb) of Santa Cruz district that was established by the Jesuits in the early 1600s. The resulting large (dai oban) colour woodcut shows the church and its tower behind palm trees, with a row of shop stalls and a calesa (horse-drawn carriage) in the foreground.

In Manila she also painted a vibrant picture titled Manila Harbour (which may include a stylised image of the Governor-General’s yacht Apo), and a scene of a nun from the Daughters of Charity giving alms to the poor in the doorway of Santa Isabel Tower. Salaman described the resulting woodblock print (also dai oban) as follows:

In Friday Morning Almsgiving, Manila she has given us one of the best of her prints. Within a green doorway that opens on to a pink façade, sits a man [in fact, the nun] dispensing his alms to the needy. A woman abases herself to receive them, while a man, a woman and a girl await their turns, and in the sunshine across the gateway an old woman, with her bundle in her hand, stands with a sardonic grin of mockery. This is perhaps the finest of all Miss Keith’s prints, and it is entirely of her own work. It makes us wonder what next she will do, for her work must advance.

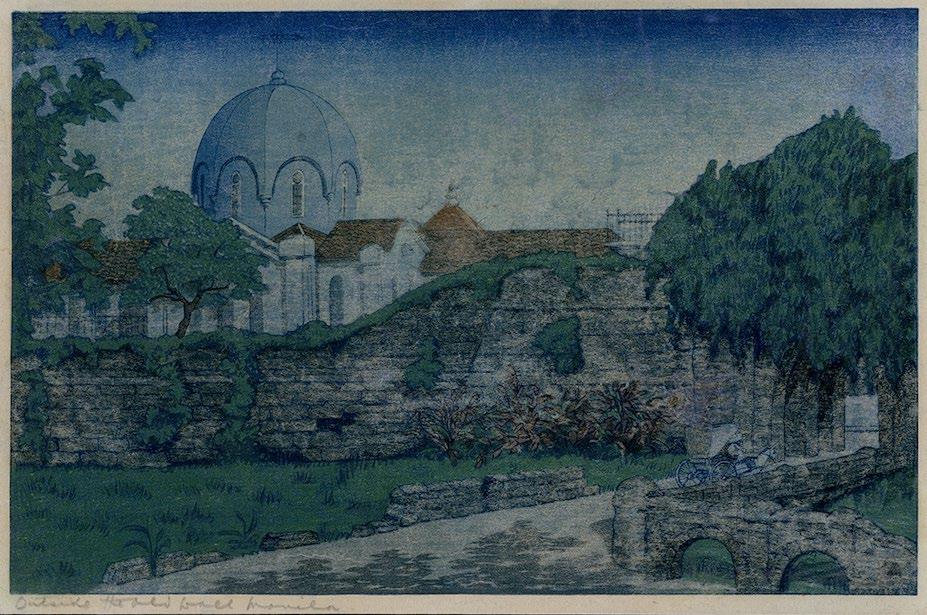

Woodblock print titled Outside the Old Wall, Manila (image courtesy of Moonlit Sea Prints)

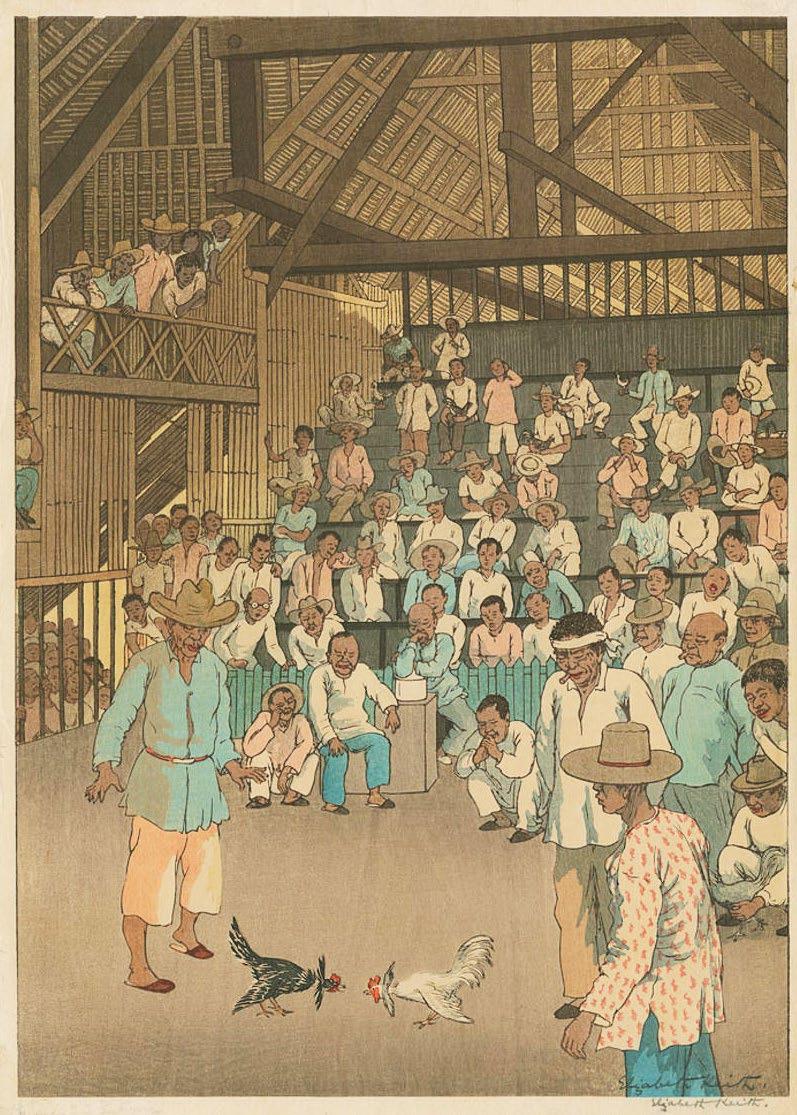

Woodblock print of a cock fight in the Philippines (image courtesy of Japanese Art Open Database)

For an exhibition at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena in 1991-92, Richard Miles compiled a catalogue raisonné titled Elizabeth Keith: The Printed Works, in which 17 prints of the Philippines are listed (including two unsigned proofs that were never printed). However, although in his Acknowledgements the author claims that ’all of Elizabeth Keith’s known prints are included in this catalogue’, after more recent research Darrel Karl has commented in his blog Elizabeth Keith: The Uncatalogued Prints:

At the time it was a seminal catalog, illustrating 108 of Keith's woodblock prints and etchings. However, [it] was prepared when the World Wide Web was in its infancy and before museums and art dealers started to make digital images of Keith's prints readily available. Despite what I'm sure were Miles' best efforts, the catalog is riddled with errors. Woodblock prints are labeled as etchings or vice-versa, dimensions are reversed, erroneous titles or dates are ascribed to certain print designs, etc. Miles' source of information about the number of sheets printed is unclear and in many cases questionable in light of copies which have since come to light. Although print variants of many Keith designs exist, none are illustrated and only one is specifically mentioned.

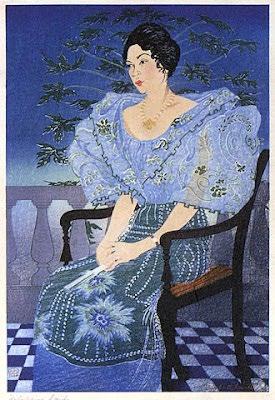

Of the 20 additional prints discovered by Karl, five are of the Philippines, including the one of Santa Cruz Church described above; The Cock Fight, Manila; and two portraits of ladies wearing Filipino dress. No. 74 in the catalogue is Outside the Old Wall, Manila, which shows the walls of Intramuros with the moat, a bridge, a calesa, buildings and the stylised dome of Manila Cathedral in the background. However, Miles incorrectly titles this print Friday Morning, Manila, which in fact appears to be the print shown as no. 77 in the catalogue, incorrectly named Market Day, Baguio. The print illustrated shows a man in a straw hat driving a calesa past a shop selling bird cages, baskets and brooms, with a lady in a blue dress in the foreground.

Following a recommendation, Keith went to the summer hill capital, Baguio, in order to see the different northern tribes, known collectively as Igorots, which include Apayao, Benguet, Bontoc, Ifugao, Kalinga and Kankanay. Having arrived in Baguio she thought she could cover her objects of interest in a week, but ten weeks later she was still there as there were so many of the subjects that she loved. She was given the name of a native school for weaving to visit, and with her eye for detail wrote: ’The Benguet blanket is usually blue and white with touches of red. The women wear strings of beads round their necks, and their skirts and jackets are of richly coloured stripes, or checks.’

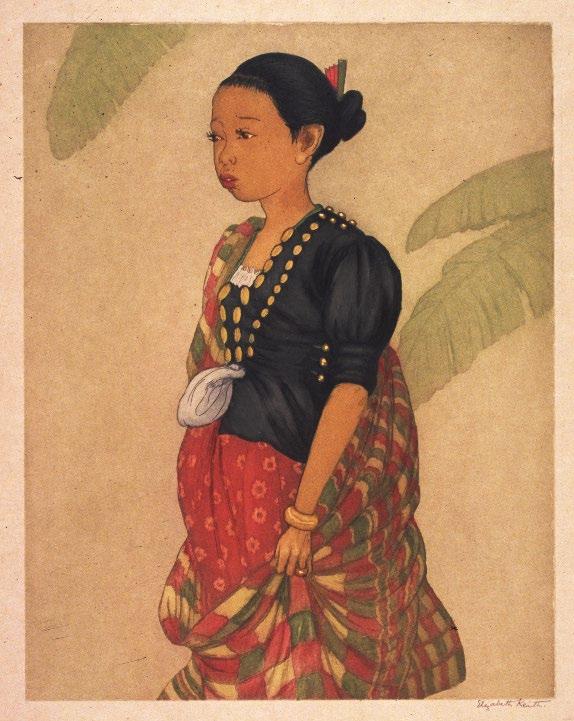

Woodblock print titled Philippine Lady (image courtesy of Hanga Gallery)

titled

There Keith painted The Kanaow, Baguio, P.I. (Benguet Tribe), which would later translate as a beautiful woodblock print. In Eastern Windows she explains the background of the image, which shows a traditional Cañao tribal celebration with joyful drum beating and dancing by a log fire, as follows:

One beautiful moonlight (sic) night I begged the interpreter to ask some Benguets to come out in the open and dance. So, to please me, they lit a big bonfire and danced by its light and the light of the moon. … The music at these festivals is so exciting that I never hear it without feeling the magnetism of the dance.

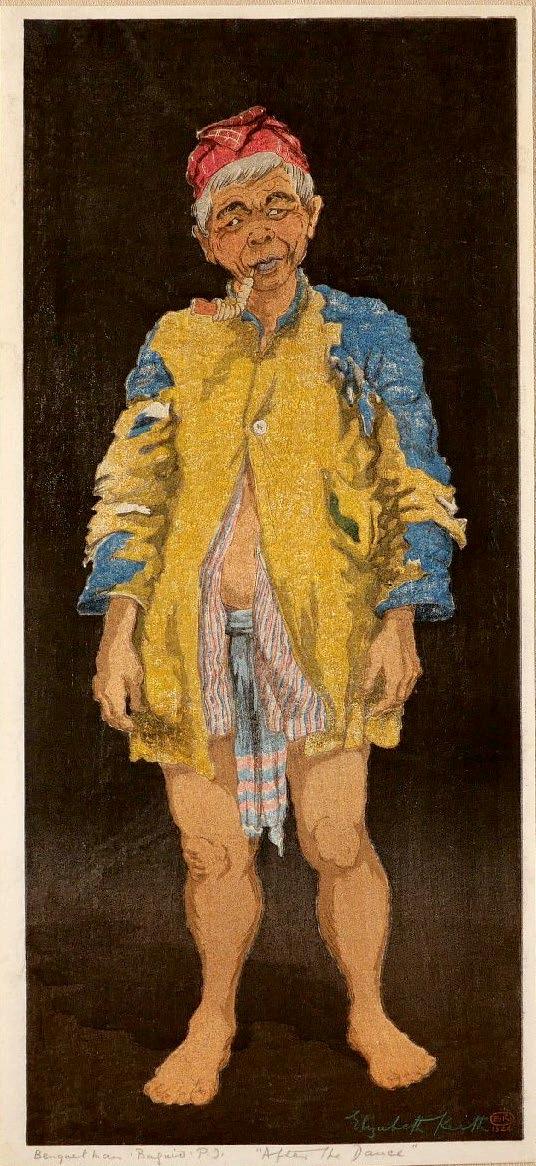

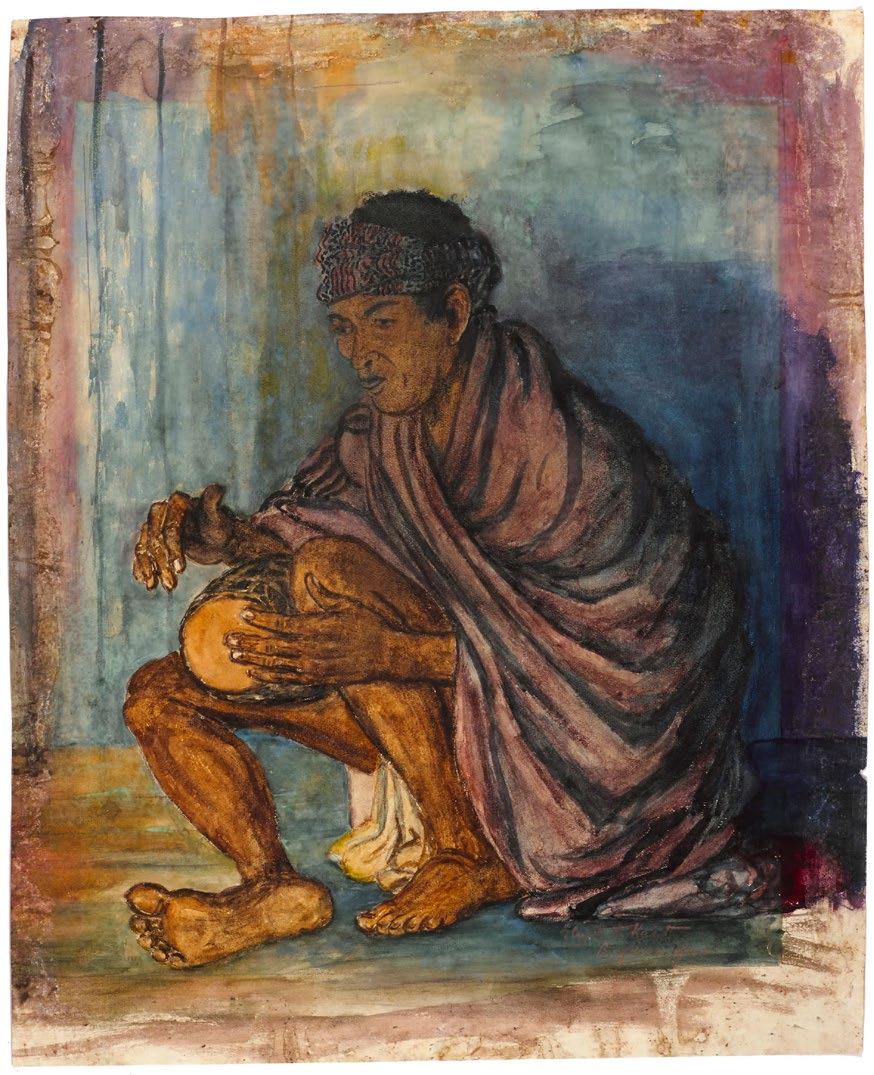

Another print, Benguet Man, Baguio ‘After the Dance’, depicts an elderly man with squint eyes, smoking a pipe and wearing a red cap, with tattered blue, yellow and striped clothes. Market Day, Baguio P.I. shows the market traders in front of their stalls and wagons below the hills of Baguio, with Igorots carrying umbrellas and a chicken, native pigs, a water buffalo, and cows in the background. Keith also painted a watercolour of a seated man from Baguio playing a drum, and a portrait of an Ifugao boy.

Woodblock print

The Kanaow, Baguio, P.I. (Benguet Tribe) (author’s collection)

Woodblock Benguet Man, Baguio ‘After the Dance’ (image courtesy of Artelino)

Having spent some months in Baguio Keith returned to Manila, where she boarded a ‘little inter-island boat’ for the south, which she called

‘Moroland’. Having survived ‘cockroaches too numerous and too big to kill’ and a terrible storm, she arrived in Zamboanga, from where she visited the Sulu Archipelago. Mindanao and Sulu were a rich source of inspiration for Keith.

A particularly vibrant print titled Moro Village, Zamboanga shows a cluster of native houses on stilts beneath towering coconut trees. The scene teems with activity as the women in colourful clothes dry their washing and look after the children, while a man drinks tea and another carries bamboo. Bananas, jackfruit and other tropical fruit, fish, eggs, a painted boat, a water jar and, in the foreground, a black cock and a white hen are depicted.

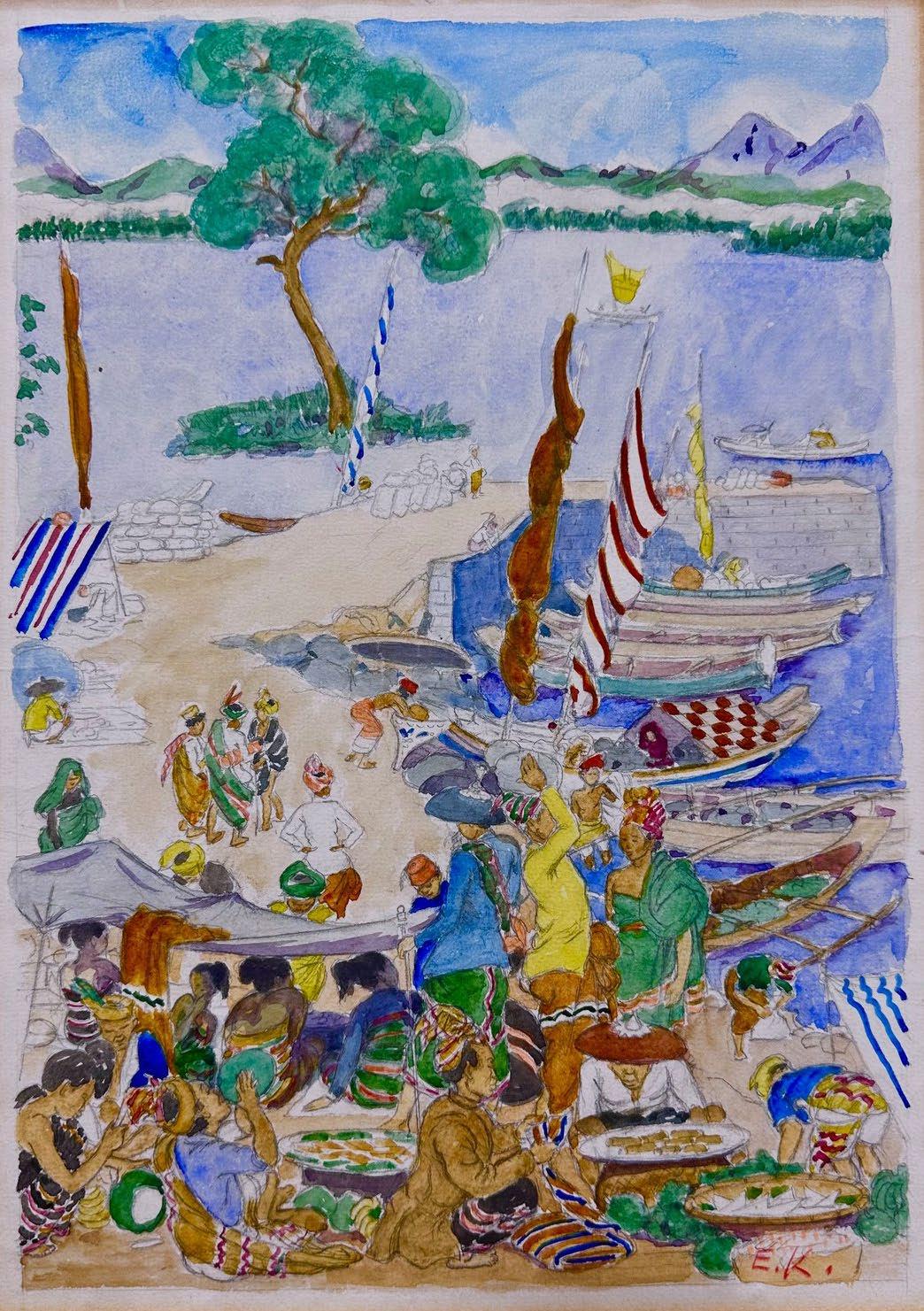

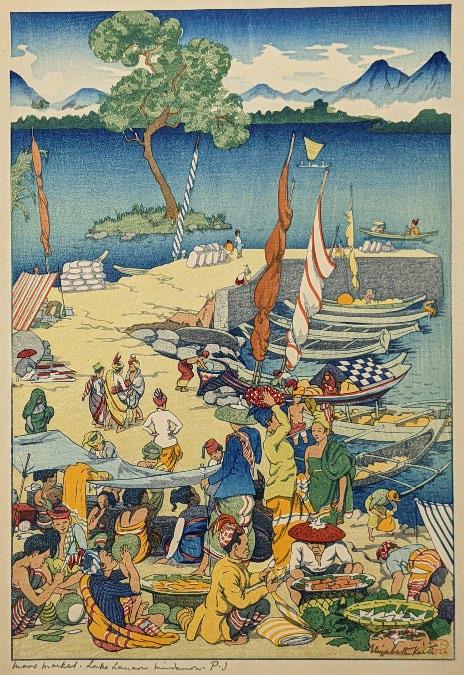

In Moro Market. Lake Lanao. Mindanao, P.I. the lively foreground is dominated by market traders selling buko (young coconut), food laid out on trays, and textiles; behind lie the wharf, boats with furled sails, and piles of sacks. A tree and the lake are shown, with mountains in the distance. The original watercolour painting for this print is held in a private collection. Without specifying the location, in Eastern Windows Keith describes a similar market ‘in Moroland’:

Watercolour of a seated man, Baguio (image courtesy of Bonhams)

Woodblock print of Market Day, Baguio P.I. (image courtesy of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon)

Woodblock print titled Moro Village, Zamboanga (Peter Geldart collection; image courtesy of Bonhams)

In this place, market day is the event of the week. The market was a joyful sketching place. Boats kept arriving from every part of the lake. These long narrow boats are often hewn from a single tree and each boat has a number of rowers. The sails are striped or in squares of different colours, and the boats are carved and gaily painted. The dresses and hats of the men and women are glorious in variety. Every boat was piled high with fruits and vegetables.

Throngs of people had gathered on the hill-side where the market was held. The sky was the roof, and everywhere were delightful groupings of people and things. Women were cooking savoury messes, while people stood or sat around and ate. Others were drinking coco-nut juice. The sweet cakes were green and red and white. There were cassava roots, and other tropical fruits and vegetables. Big bales of cloth ‒ alas, much of it foreign ‒ were piled high, and there were hats with wide, drooping brims.

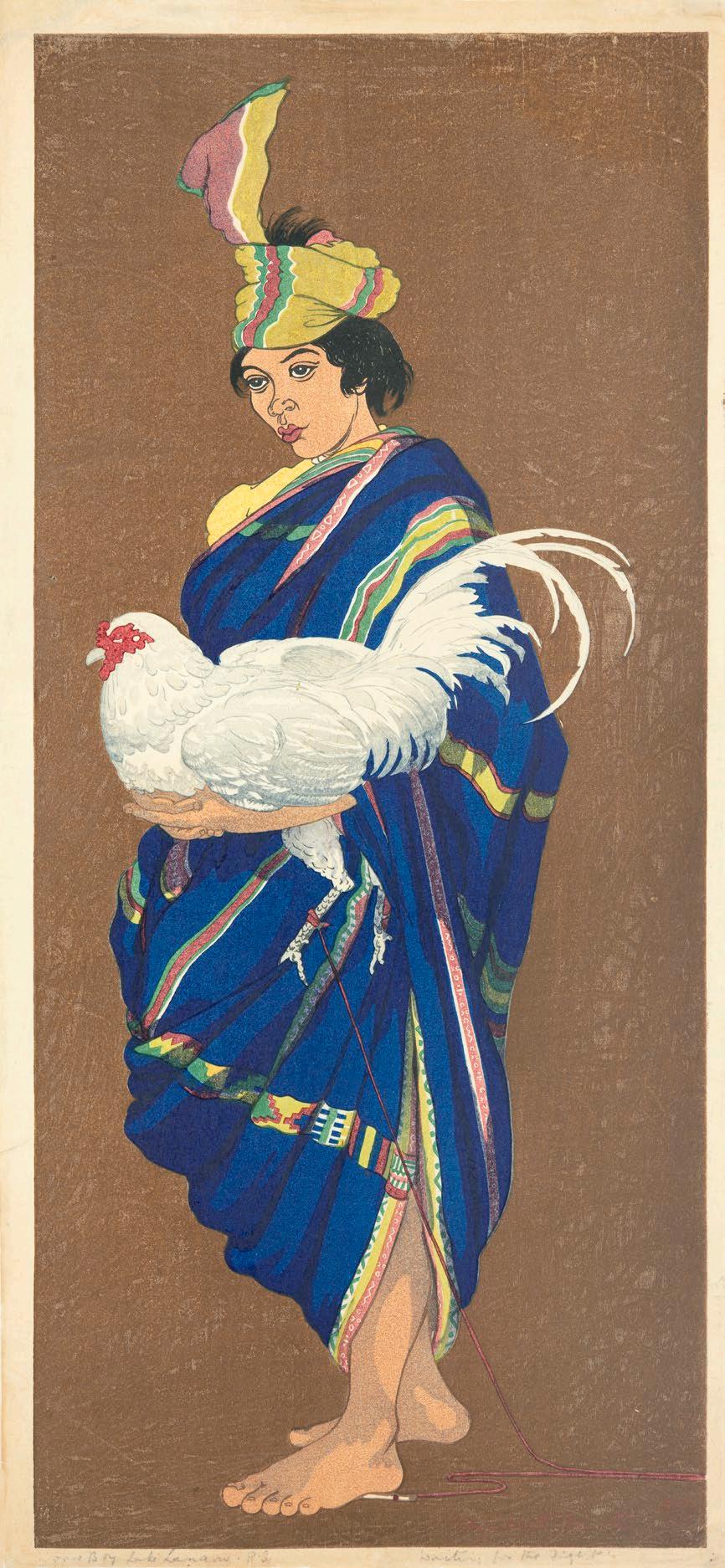

Among many pictures of the people she found especially interesting, she made one particularly striking colour print. Moro Boy. Lake Lanao P.I. ‒Waiting for the Fight shows the boy standing

with a white cock in his arms He wears a graceful striped blue garment with a twisted yellow headdress as he waits keenly for the combat, cockfighting being a national sport.

In Jolo she writes about the ‘handsome men’, the ‘slender, small and graceful women’, the ‘rushcovered huts built on piles’, and the ‘elaborately carved Datus’ houses’. In another evocative print, Moro Vintas. Jolo. Sulu. P.I., a man and a woman are in an outrigger boat, fishing at dusk; in the background another boat displays a checkered sail.

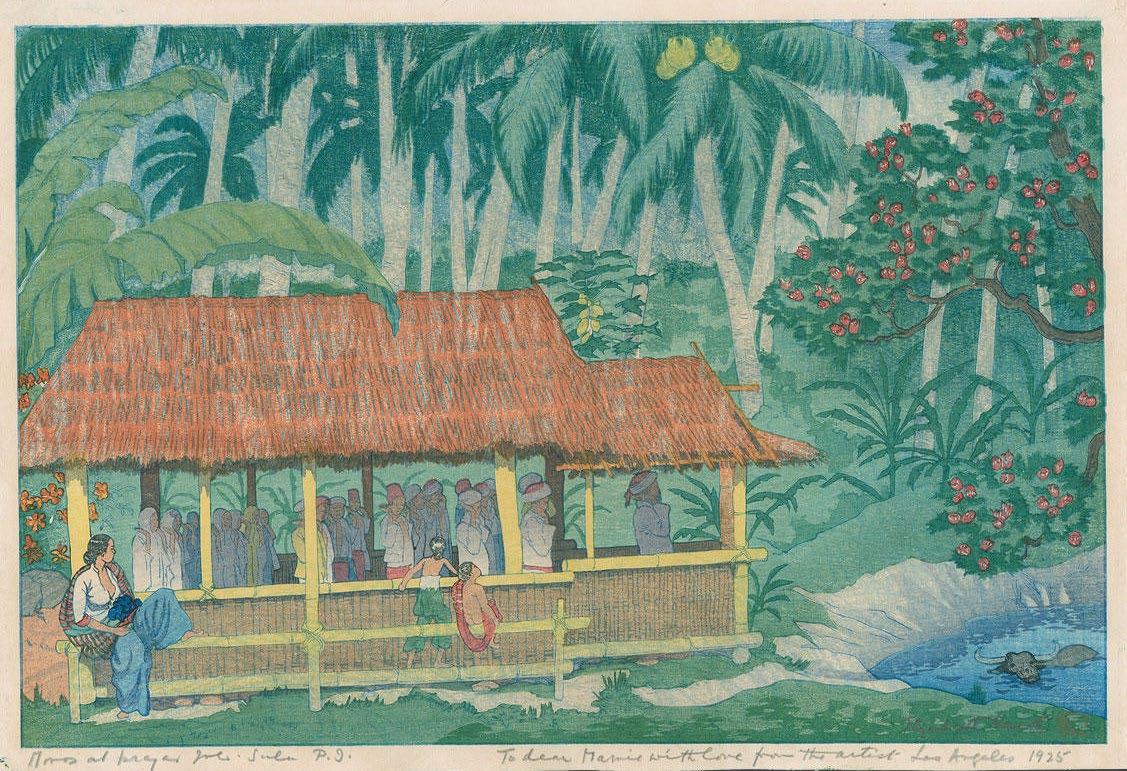

Moros at Prayer. Jolo. Sulu. P.I. depicts a village mosque with the men standing at prayer with the women standing behind them or looking in from the outside, while under the tropical vegetation a water buffalo wallows contentedly in a pool. A Moro Umbrella. Jolo. Sulu. P.I. shows a woman sheltering from the driving rain under a large banana leaf with two green parrots flying overhead. There is also a print of a Moro Dance, where a man with a fan dances to the music of drums and gongs, and an etching of a ‘Moro Princess’

Watercolour (left) and woodblock print (right) titled Moro Market. Lake Lanao. Mindanao P.I. (watercolour from a private collection; woodblock image courtesy of Tremont Auctions)

Woodblock print titled Moro Boy. Lake Lanao P.I. ‒ Waiting for the Fight (author’s collection)

Keith was enchanted by the colours and the landscape of Sulu:

Green and white parrots flit about in Moro land. The trees have long, long stems, and parasitical plants stream gracefully from their sides. The fruits have strange, luscious smells. The horizon is outlined by beautifully rounded hills, where upright trees of great height are arranged as if by design. The skies and clouds are marvellously beautiful.

Etching of a ‘Moro Princess’ (image courtesy of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon)

Woodblock print of A Moro Umbrella. Jolo. Sulu. P.I. (image courtesy of Tremont Auctions)

print titled

(image courtesy of The Art of

)

Woodblock print titled Moros at Prayer. Jolo. Sulu. P.I. Inscribed ‘To dear Mamie with love from the artist Los Angeles 1925’ (image courtesy of Japanese Art Open Database)

Woodblock

Moro Vintas. Jolo. Sulu P.I.

Japan

The people of Sulu were even more fascinating:

I had long heard of ‘Mama’ and his ten wives. On the day I was leaving Jolo, ‘Mama’ invited me to a feast. Being a rich man ‒ how otherwise could he maintain such a seraglio? ‒ his house was very ‘grand’. Children peeped from all corners. The gentleman himself, if not beautiful, had rather ‘a leg’. He was excited at our approach. He had been superintending the ladies at their various jobs. I had some difficulty in retaining more than three at a time. At last I got the two latest ‒ the favourites ‒ and placed them one on each side of their master so that I might sketch them.

‘Mama’ was too restless to sit still for long, but the ladies were docile. While I was sketching this group, three other wives were going through an elaborate toilet. In the end, I managed to sketch seven wives, but before I could finish the sketch an excited messenger arrived to say that the boat was leaving three hours earlier than scheduled and I had to stop. Alas for the injustice of this world! The earliest and oldest of the wives, who, I believe, has only one eye never even appeared

Keith returned to England in late 1924. On her return journey she travelled across America; she had established patrons there, and her prints were admired in a number of cities. In 1928 her

first American exhibition was held at the Nicholson Gallery for Oriental Art in Pasadena (which became the Pacific Asia Museum). Back in Europe she spent nearly a year in France, where she had an exhibition in Paris The following year she exhibited two of her prints at the Royal Academy At home in London, where for a time she lived in St. John's Wood, she studied the art of etching with William Palmer Robins at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Here she learnt etching and printing in colour from copper plates, which added another dimension to her knowledge of Japanese woodblock printing.

She continued to travel and paint, with Watanabe publishing prints of her designs until 1939. During her collaboration with Watanabe, Keith created over a hundred woodblock prints. As she was one of only a few Western women shin-hanga printmakers in Japan her lovely works became a wonderful choice for collectors of Japanese-style prints. Her woodblock subjects are beautifully detailed and drawn, with a marvellous sense of location and a respect for the activities of the people as they go about their daily lives. Watanabe's skilful prints successfully translate the look of her watercolours into the difficult medium of woodblocks, capturing nuances of colour and tone that give these images a painterly appearance.

Mama and His Wives, Jolo, c.1924 (author’s collection)

In 1933 Keith was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. In 1937 she held an exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London at which Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother purchased seven of her prints, including two that are now in the Royal Collection Trust. Her works are also held in the British Museum and in public collections in America, Canada, Paris and Sweden.

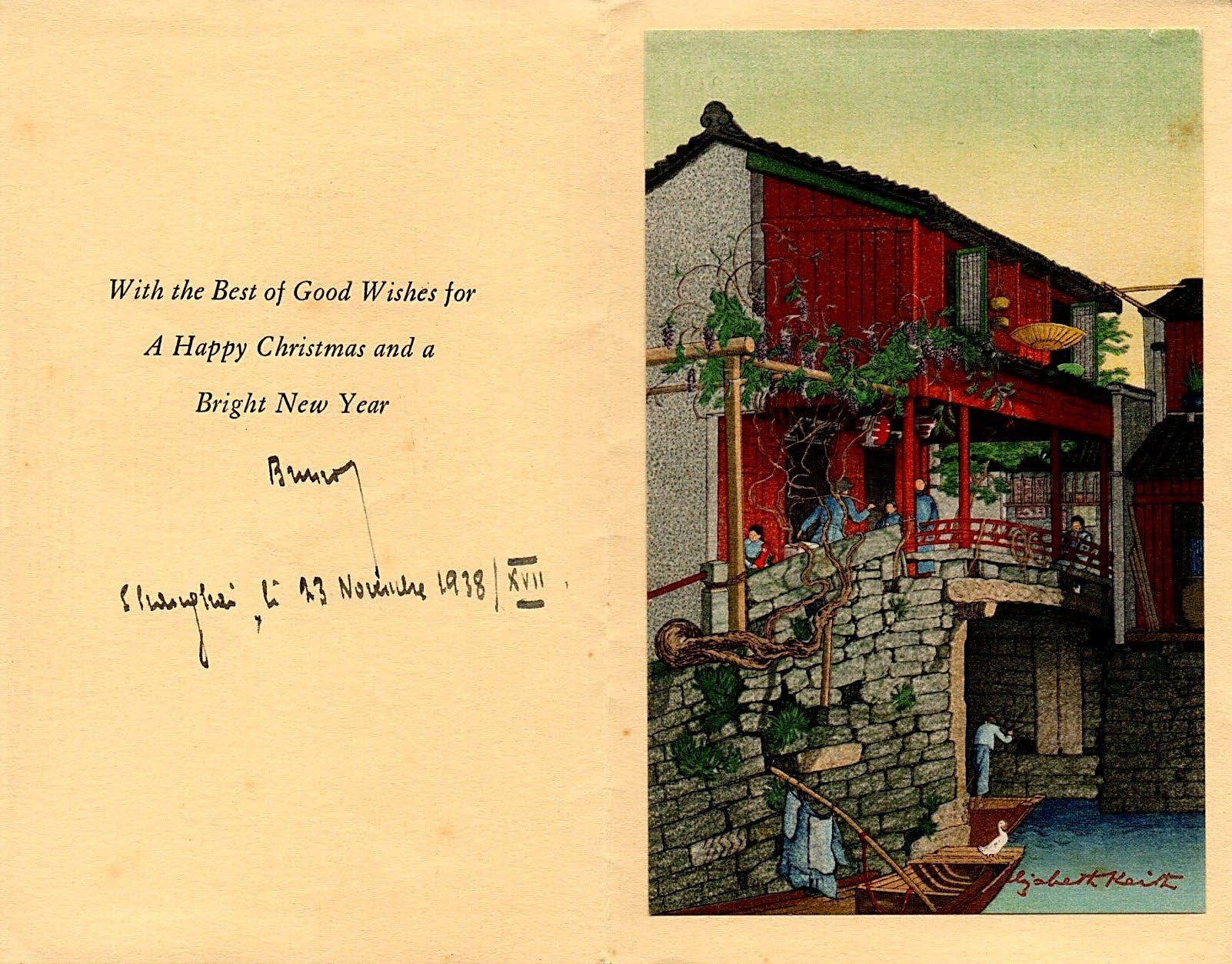

Keith visited Japan again in 1932-33, and made her last trip there in 1935-36, when she made sketches for a series of prints. In 1936 and 1937 she again had exhibitions in the United States. At this time even postcards and Christmas cards of her pictures were published in Shanghai. However, with World War II on the horizon she became caught between East and West as the market for Asian-influenced art deteriorated, and she was no longer able to support herself from the sale of her work.

Although virtually abandoned by collectors, her dealer and even her friends, Keith was comforted by her Christian Science faith. She continued painting and making prints of the landscapes and people she loved, and demand for her pictures revived 20 to 30 years later. In 1956, the year of her death, an exhibition of her work in Tokyo had 59 woodblock prints and eight coloured etchings.

One of Keith’s best patrons was Gertrude Bass Warner, a fellow Christian Scientist who had met her in Japan and bought some of her prints for the collection she amassed together with her husband Murray Warner. For over 20 years Warner corresponded with Keith and continued to collect her etchings, watercolours, drawings

and woodblock prints. Warner became the first Director and donor of the Museum of Art at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon. In 1974 the museum held an exhibition titled ‘Elizabeth Keith (1886-1956): The Orient through Western Eyes’; to quote from the catalogue:

This exhibition, showing for the first time our complete collection of Elizabeth Keith graphics and sketches, includes most of her major work from China, Japan and especially Korea. Also included are seven prints resulting from a brief visit to the Philippine Islands, where she was greatly impressed by the Moro people ‘walking singly against their green background’ like a frieze, seeming ‘free as tropical birds’.

Keith’s prints were often issued in quite small numbers, some with print runs of 30 copies or fewer. Although her works have been quite well researched and documented, there are still discoveries to be made. Today her prints, etchings and paintings have a global following with quite a number of collectors competing to buy them; at auction her prints regularly sell for more than the high estimate. To date, the highest price recorded for an Elizabeth Keith print was Hong Kong Harbour at Night, which sold at Christie’s New York in 2024 for US$52,920.

Elizabeth Keith’s prints of the Philippines are particularly rare, and we hope this article will encourage collectors in the Philippines to look out for them. Please let us know if you find any that are not described or mentioned here!

This article is based on the talk given to PHIMCOS by the author on 12 November, 2025

˂ Elizabeth Keith

Hong Kong Harbour at Night Woodblock print (image courtesy of Christie’s)

Christmas card with Elizabeth Keith woodblock print of Wisteria Bridge, China, (1925) 1938 (image courtesy of the Bill Savadove collection)

Bibliography

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs, third edition, Vol. 6., Librairie Gründ, Paris, 1976.

Dongho Chun, Selling East Asia in Colour: Elizabeth Keith and Korea, ResearchGate GmbH, 2020.

Elizabeth Keith, Grin and Bear It, The New East Press, Tokyo, 1917.

Elizabeth Keith, Eastern Windows. An Artist's Notes of Travel in Japan, Hokkaido, Korea, China and the Philippines, Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London, 1928.

Elizabeth Keith and E.K. Robertson Scott, Old Korea, The Land of Morning Calm, Hutchinson & Co., Ltd., London, 1946.

Elizabeth Keith and Jessie Keith, ‘Letters to Gertrude Bass Warner, 1925-1948’, files of the Museum of Art, University of Oregon.

Richard Miles, Elizabeth Keith: The Printed Works, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena,1991.

Richard C. Paulin and Barbara Zentner, Elizabeth Keith (1887-1956): The Orient Through Western Eyes, Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, 1974.

Malcom C. Salaman, Masters of the Colour Print 9: Elizabeth Keith, The Studio Limited, London, 1933.

Weblinks

The Annex Galleries https://www.annexgalleries.com/artists/biography/1216

Jacques Dumasy, Far-Orientalism / Far East, A Western Look: https://far-orientalism.com/collection/keith-elizabeth.html

East Carolina University, Old Korea from the Eyes of Four Western Artists: https://www.oldkorea.net/about-1-1

John Fiorillo, Viewing Japanese Prints: https://viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/shin_hanga/keith.html

Hanga Gallery

https://www.hanga.com/prints.cfm?ID=26

Darrel C. Karl, Elizabeth Keith: The Uncatalogued Prints: https://easternimp.blogspot.com/2015/08/elizabeth-keith-uncatalogued-prints.html

Moonlit Sea Prints, Elizabeth Keith ‒ A Westerner in Japan: https://elizabethkeith.art/

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon: https://jsmacollection.uoregon.edu/mwebcgi/mweb?request=advanced;_tkeyword=elizabeth%2A%20keith%2A OsakaPrints.com: https://www.osakaprints.com/content/information/artist_bios/bio_keith_elizabeth.htm

Royal Collection Trust: https://www.rct.uk/collection/exhibitions/watercolours-and-drawings-in-the-collection-of-queen-elizabeththe-queen/spring-in-soochow

Anastasia von Seibold Japanese Art: https://www.avsjapaneseart.com/artists/77-elizabeth-keith-%281887-1956%29/biography/

Ukiyo-e Discussion Forum / The Art of Japan: https://ukiyo-e.org/search?q=elizabeth+keith

Ross Walker, JAODB ‒ Japanese Art Open Database: https://www.jaodb.com/

WATTIS FINE ART Est. 1988

Specialist Antique & Art

Dealers

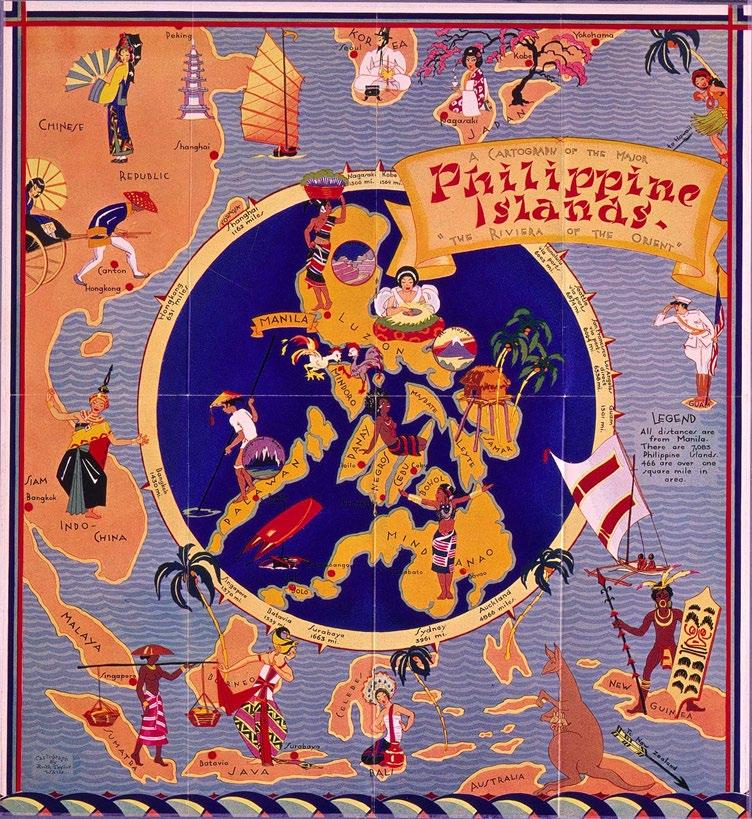

A Cartograph of the Major Philippine Islands c.1930 by Ruth Taylor White www.wattis.com.hk Antique maps, prints, photographs, postcards, paintings & books

Tracking the Lost Palace of the Sultan of Joló

Field reflections on how a 19th -century Spanish map can enhance a historic site

by Carlos Madrid Ph.D.

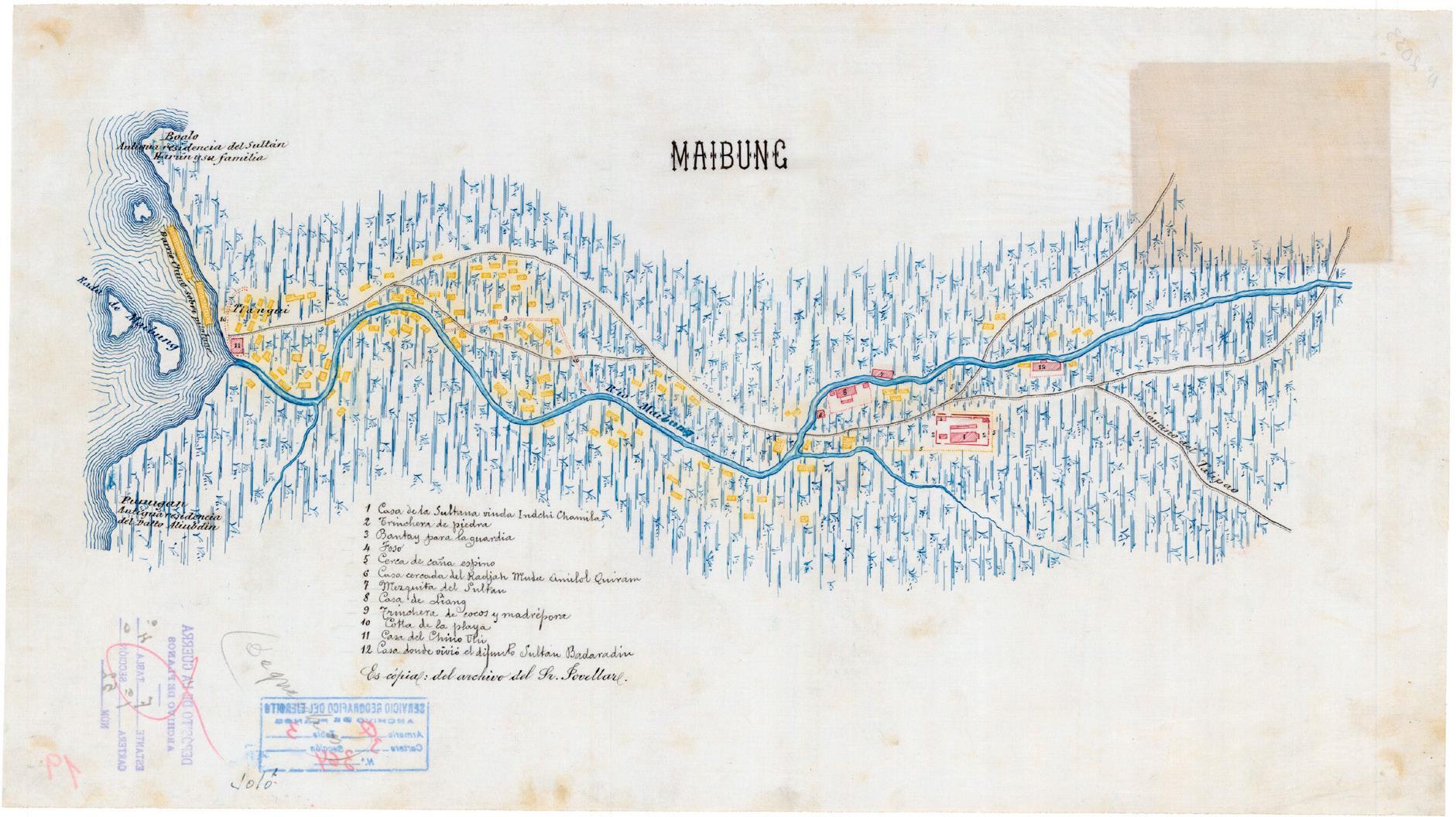

MAPS MAY be drawn for political or military purposes, but they often register features that resist time. In that sense, maps are time capsules. The one discussed here, a manuscript titled Maibung from the mid- 1880s preserved in the Servicio Geográfico del Ejército in Madrid, (1) became a working instrument for the community in Sulu today when it revealed details about where a royal complex once stood.

The map depicts the bay and settlement of Maimbung, on the southwest coast of the main island of Joló, then the political heart of the Sulú Sultanate. Its delicate lines in bright blue, yellow and red ink, annotated in black, trace the path of a river with its mouth at the Maimbung roadstead where two small islets fac e the coast N earby waterways are shown, and a few place names such as Bualo and the Camino del Talipao, each carrying historical weight. A modern archivist first dated the document to 1885, later amending it to 1888. Internal evidence suggests

1883–85 and that this version is a clean duplicate. The legend reads ‘ Es copia del a rchivo del Sr. Jovellar’ , confirming that it was copied for Governor- General Joaquín Jovellar, who ruled the Philippines during those same years.

Arrival in Sulu

In the early hours of 29 September, 2024, I crossed the Sulu Sea on the open deck of a creaking ferry, lying on metal trunks under a magnificent sky. I had been invited by the Cultural Hub of Notre Dame of Jolo College to join a delegation from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), led by its indefatigable chairman, Regalado Trota José. Our mission was to identify historic sites that might be included in the National Register of Historic Sites. In my backpack were copies of Spanish maps, a notebook and, like my fellow travelers, a generous measure of anticipation for the fieldwork ahead.

The author in front of the site of the Astanah Darul Jambangan

Manuscript map of Maibung c.1883 – 85 (image courtesy of Archivo Cartográfico y de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército, España )

The map I carried seemed to have been commissioned under Governor- General Jovellar amid the political turmoil that followed the death of Sultan Diamarol (Djamârol) on 18 April 1881. His widow, Indchi Chamila ‒ also known as Panguihan Yulfi Yamilá or Sultana Jamila ‒ was left to face a contested succession (according to Spanish sources) between Diamarol’s natural

son, Badarud- Din II, who became sultan but died in Maimbung on 22 February, 1884, and his 14- year- old legitimate son, Mohamed- AmirulQuiram, the Rajah Muda or hereditary Prince. Diamarol’s brother, Datto Alimbdín (or Aliubdin), a Spanish- leaning claimant based in Patikul, also pressed his case.

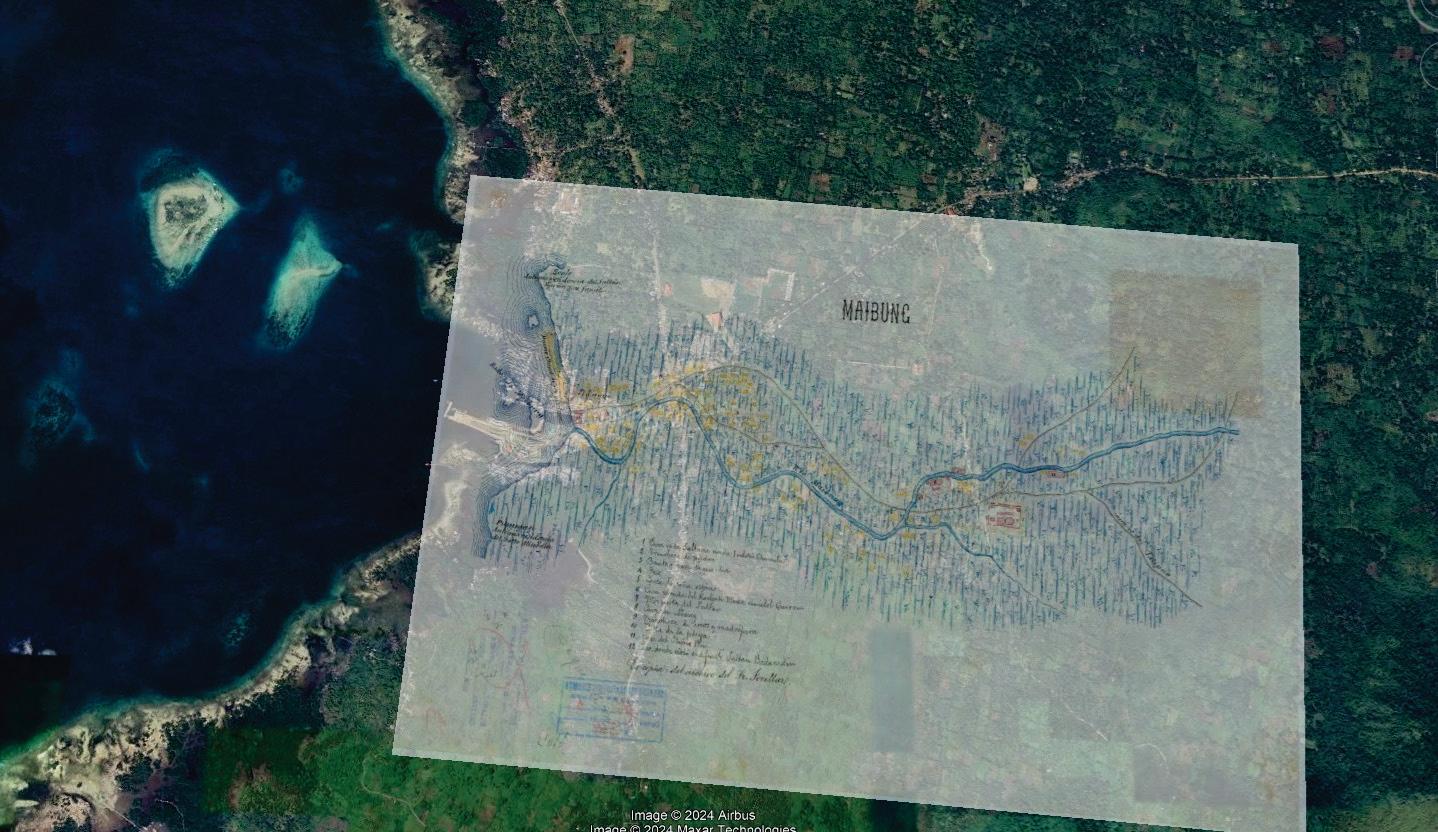

Overlay of the map by the author on Google Earth satellite image ©2024 Airbus / Maxar Technologies

The dispute, despite Spanish mediation, pitted uncle against nephew, as summarized in a report from 1884 published in 1887:(2)

Nothing that could affect the regime and governance of the aforementioned island had occurred since the agreement we referred to, until the death of Sultan Buderodin [BadarudDin II]. Two candidates presented themselves to govern the fate of the Joloan archipelago: The Radjah-Mudah or Heir Prince, MohamedAmirul-Quiram, a fourteen-year-old legitimate son of Sultan Diamarol and brother of Buderodin, who was natural son of Diamarol; and Datto Alimbdín, uncle of both of them as brother of the said Diamarol.

Both claimants, recognizing our sovereignty, requested the Governor General of the Philippines to act as a mediator to resolve the dispute in which they were engaged. The higher authority, the illustrious General Jovellar, known for his skill and diplomacy , dispatched to Joló the Arabic interpreter of the Governor General, Don Pedro Ortuoste, to discuss means of reaching an agreement on the matter, given that a more convenient one had not been found yet, regarding the final election of the Radjah.

Ortuoste, a little known figure deserving deeper study, was a Philippine- born Spaniard married to a Filipina, Casimira Seyson Known in Jolo as ‘Panoy’ , he was fluent in both Tausug and Maguindanao n. He had served as interpreter for the 1878 treaty between Spain and the

Sultanate. Governor General Jovellar sent him back to Maimbung to convince the sultan to accept recognition from Manila. It is plausible that this map, annotated with military features and local names, emerged from that 1883- 85 mediation and reconnaissance. Ortuoste or someone in his party may have drawn it, turning field notes into a visual report for the governorgeneral’s files.

Reading the map in the field

Maimbung lies on Jolo’s southwest coast, its bay sheltered by two small islets. In the late 19th century this was not a mere anchorage but the seat of Sultan Mohammed Badarud- Din II, spelled in Spanish reports as Buderodín or Badarudín. Today, the provincial government has revived that royal presence by reconstructing the Astanah (palace) using materials and structures inspired by photographs from the 1930s

On 1 October, 2024, Engineer Sarid Makiri and his team, who were overseeing the reconstruction of the Astanah Darul Jambangan, generously guided us through the site. He explained to architect Edgardo Mar Castro and me that the project rises atop the original foundation lines, documented by American and Filipino surveyors over the 20th century. The remaining stone walls, sadly demolished to allow access for construction machinery but preserved nearby for future reconstruction, ha ve several access gates that c an be traced in the field.

Detail of the buildings and enclosures from the map of Maibung (image courtesy of Archivo Cartográfico y de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército, España )

By aligning the drawing s in the 1880s map with satellite imagery and testing the alignments on site with local informants, we could recognize some features shown in the map. But to match the surviving wall fragments we had to rotate the palace section of the map 90o over the satellite images. The map refers to the enclosures as trincheras, not trenches in the modern sense but raised earthworks or stone walls (as defined in the Diccionario de Autoridades) (3) The map also shows the palace at a slight diagonal within its rectangular enclosure, a deta il confirmed in the current reconstruction.

Turning the palace area of the map, however, disrupted other relationships. The Camino del Talipao no longer pointed toward Talipao , a town about seven miles northeast of Maimbung. The map placed the palace within a rectangular stone perimeter beside the river and labeled adjacent structures: the Sultan’s mosque, the house of Rajah Muda Miram, and that of a Chinese adviser named Liang . These names fit known historical figures, giving the sketch social accuracy.

Still, the discrepancies are telling. The two islets in the bay, for instance, are not drawn to scale; suggesting the map’s aim was not geo graphic but schematic. It should be read as a visual report, showing relationships and directions more than distances. The essential elements are the sinuous path of the river, the village and the royal compound, placed deliberately at the center, both symbolically and as the probable reason for the map’s creation. On paper, the palace block aligns north- south, perpendic ular to the shore.

Satellite image showing the current s ite of the reconstructed Astanah marked in red, and the s ite shown on the Spanish map marked in yellow (image courtesy of Google Earth / Maxar Technologies ©2024 )

But in the current site, surviving foundations indicate an east- west orientation, parallel to the sea. More troubling, the modern reconstruction stands nearly half a mile north of the river, whereas the 1880s map places the palace directly beside it

Near the current Astanah lies a royal cemetery about 50 meters to the northeast, absent from the Spanish plan. Perhaps it did not yet exist, or the Spanish were not shown it, or they visited a different royal site altogether. The possibility that the team led by Ortuoste was intentionally misoriented by local escorts in a contested landscape is plausible. But it seems more likely that the palace they visited simply stood elsewhere, and their map faithfully recorded that location.

Two sites, two palaces?

If the 1880s map is accurate, there may have been another royal palace, with a different orientation and used at a n earlier time than the later one. The map’s detailed depictions of the mosque, the tiangué (market) and the neighboring houses match other sources, including a photograph taken by the British naturalist Francis Henry Guillemard in 1883. (4) Guillemard’s side view of Maimbung’s market includes buildings that fit with the Spanish sketch.

Such corroboration suggests the map derived from direct observation. Its toponyms ‒ Bualo and Talipao ‒ and the individuals named, Rajah Muda Mohamed- Amirul- Quiram, Liang , and

Sultan Badarud- Din II, fit the historical record. The plan places the royal compound beside the river and its tributary, noting the Sultan’s mosque, the houses of the Rajah Muda and Liang, and above all the residence of the widow Sultana Indchi Chamila Yamilá, along with that of the recently deceased Sultan Badarud- Din II.

If so, the 1880s palace stood not where the 1930s photographs locate what must have been a later Astanah, but about 500 meters northeast, near a meandering portion of the river. That area not only matches the river feature drawn by the Spanish map, but there is a natural pool where locals swim, referring to the area with a name that still resonates with its use by religious men, the Tubig Imam (Imam’s Water), which is about 500- 600 meters north of the area I suggest here.

During the October 2024 fieldwork we could not conclusively resolve the discrepancy between the map and the present Astanah. Yet several steps could help test the hypothesis:

a. Consult local hydrological knowledge to verify whether a tributary once flowed near the site marked on the Spanish map;

b. conduct an ocular survey of the area with local experts; and

c. collect oral histories regarding past land use and settlement patterns.

Why historical cartography matters

This case embodies a larger argument: historical maps are not mere collectibles. When preserved and shared, they become civic tools, capable of rediscovering forgotten sites, tracing the continuity or rupture of urban and sacred spaces, and aiding the reco gnition of heritage landscapes.

In a province often branded as the most dangerous in the Philippines, fieldwork must proceed with sensitivity, respect for local authority, and an awareness that the story belongs to the community. Researchers can only gather evidence, raise questions and connect the dots. Maps can provide the framework through which that dialogue unfolds.

Overlaying an archival plan on a modern basemap is only the beginning. The essential work lies in walking the terrain, listening to local memories, and allowing past and present to inform one another. Because a map compresses time into space, it becomes a meeting ground for written, spoken and built memories.

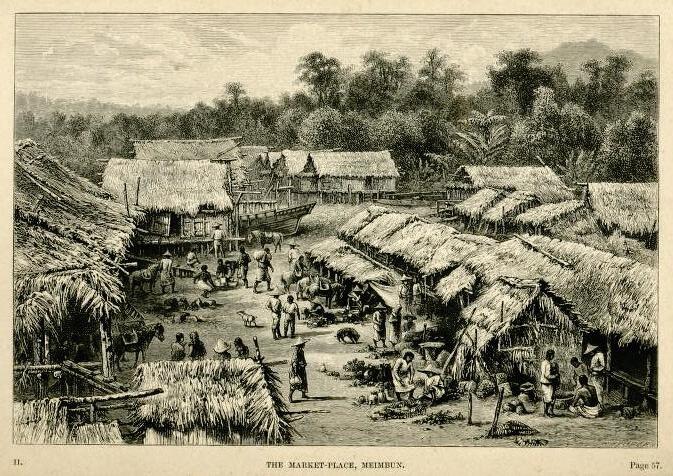

Sketch of The Market -Place, Meimbun from a photograph by Francis H.H. Guillemard (image courtesy of University of California Libraries / Internet Archive)

I owe special thanks to the Heritage Hub at Notre Dame of Jolo College; architect Edgardo Mar Castro ; Fr. Eduardo Santoyo ; Jarsun and Jenevieve Cagatin; and the NHCP team for their insight and generosity on site. I am particularly grateful to the Mayor of Maimbung , Honorable Hja . Shihla A. Tan- Hayudini, who presented me through the Heritage Hub with a locally crafted kalis (sword) as a graceful token far exceeding the modest contribution represented by this study.

To bring a map from Madrid to Sulu, and to let archival and field evidence converse, shows how cartography can enlarge our understanding of

References

history. The dialogue, however, belongs not to the researcher but to its rightful heirs: the people of Maimbung, of Sulú, and of the Philippines at large. To help strengthen community stewardship, guide reconstruction choices, or reconnect inhabitants with their historical landscape, represents the highest function of historical cartography: to serve as a civic instrument for the common good.

This article is based on the presentation given to PHIMCOS by the author, a Professor of Spanish Pacific History, on 14 May, 2025. He thanks Peter Geldart for his assistance in editing the article.

1. Maibung , Archivo Cartográfico y de Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército, Ministerio de Defensa, España, ref. Ar.Q-T.3 -C.3_364.

2. Enrique Taviel de Andrade, Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid el a ñ o de 1887 , Vol. II, Imprenta de Ulpiano Gómez y Pérez, Madrid, 1887, p. 186.

3. Diccionario de la lengua castellana, en que se explica el verdadero sentido de las voces, su naturaleza y calidad, con las frases o modos de hablar, los proverbios o refranes, y otras cosas convenientes al uso de la lengua , Real Academia Española, Madrid, 1726 -39.

4. A sketch of the photograph taken in 188 3 , ‘The Market -Place, Meimbun’, was published in Francis H.H. Guillemard, The Cruise of the Marchesa to Kamschatka & New Guinea with Notices of Formosa, LiuKiu, and Various Islands of the Malay Archipelago, Vol. II , John Murray, London, 1886, p. 57

Planning Manila: A Collection of Observations

by Miguel Santino Alvarez

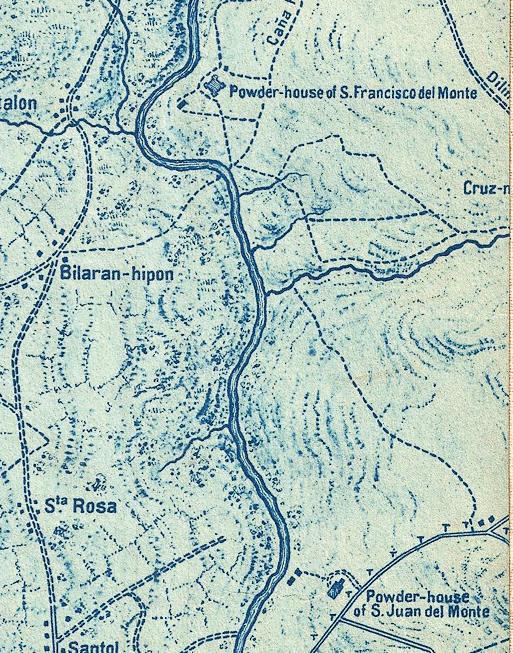

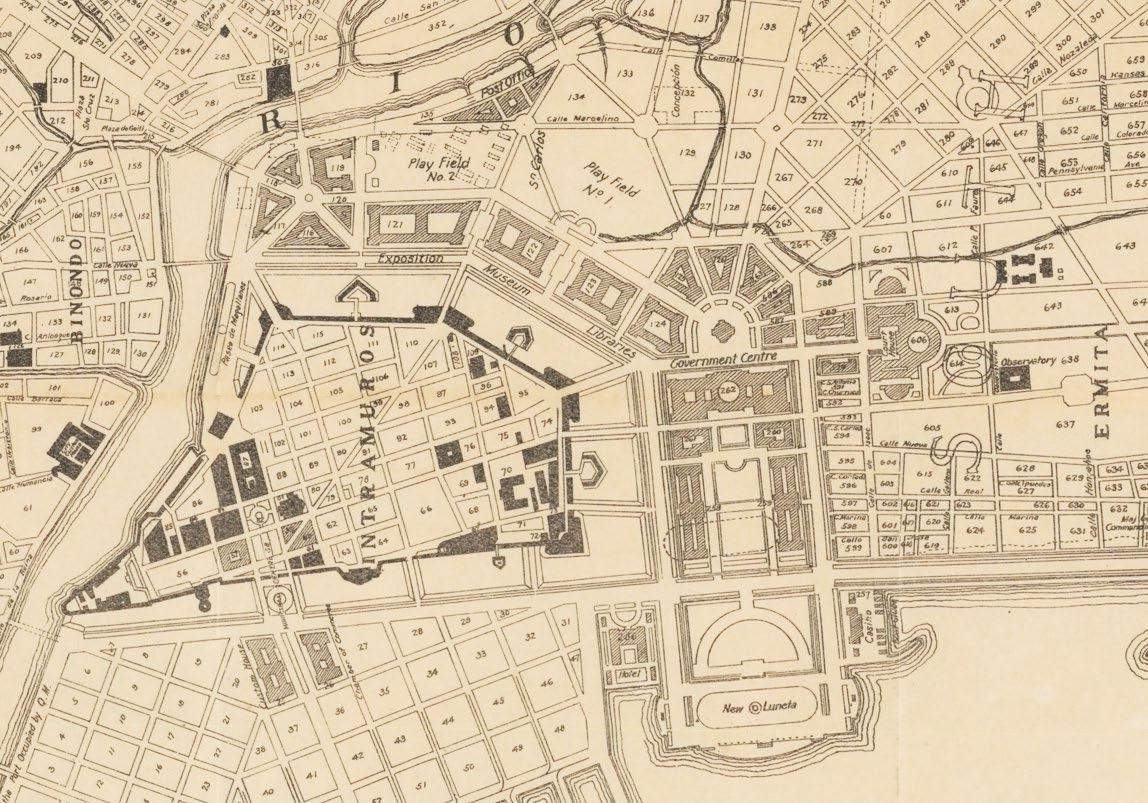

THIS ESSAY contains my observations of interesting cartographic features to be found on some of the less- well- known plans of Manila from the late- 19th and early- 20th centuries.

‘Plano de la Plaza de Manila’ Canal Network

Flooding has been a perennial problem in Manila. Spanish maps from 1780 to the mid- 19th century depict parts of Hermita (Ermita ) adjacent to a stream east and south of Intramuros labeled Rio Bago as Ynundacion or Inundacion (flood). (1) The flooding in this area might be one of the reasons why there was a lack of urban development in Ermita in the 19th century beyond the land adjacent to the coastline. One of the solutions to flooding in Spanish Manila was to build canals; the ‘specific establishment of a separate administration (Junta de Obras del Puerto de

Manila) endowed with huge financial resources represented the first serious attempt to bring about a solution’. ( 2)

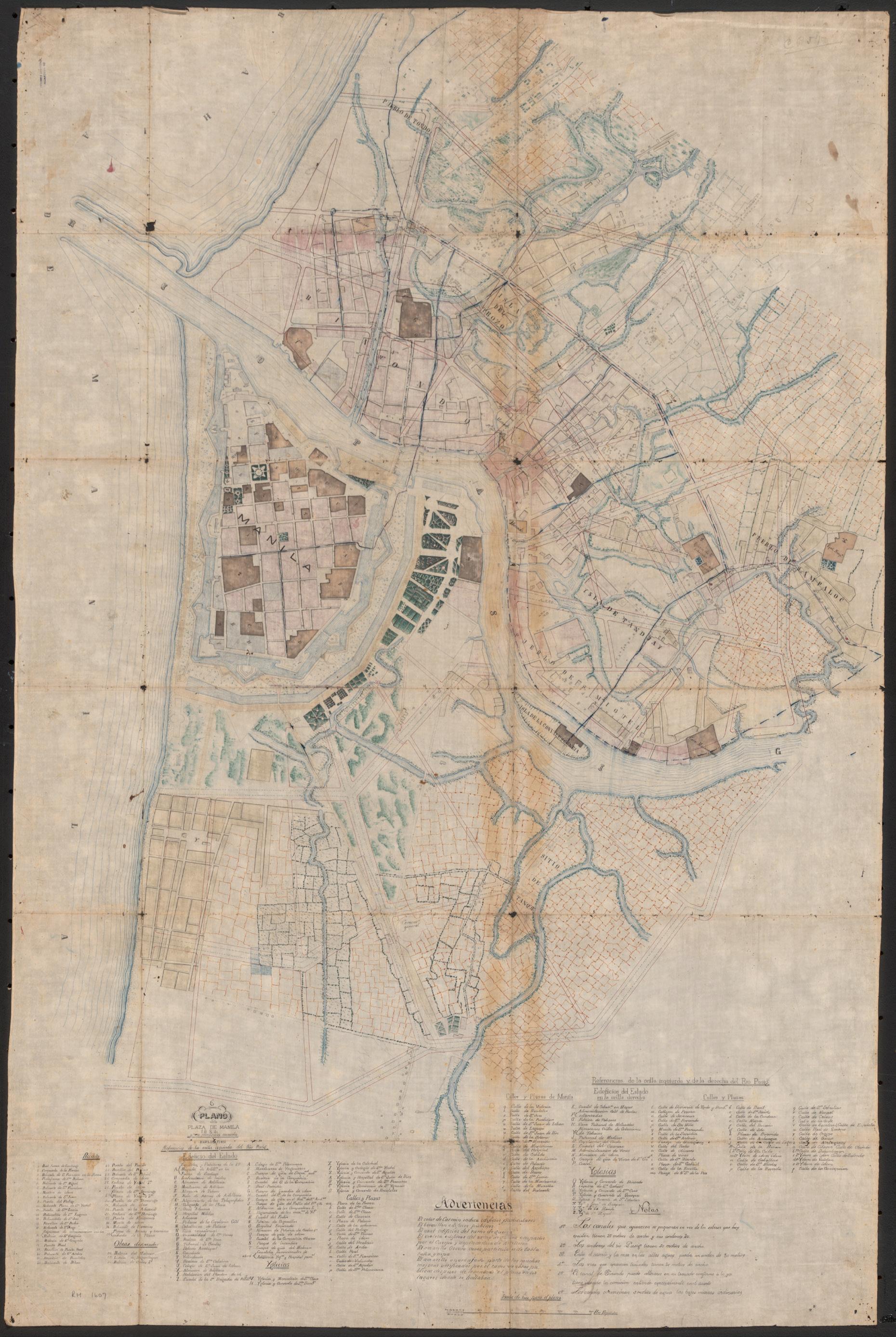

While most other maps and plans of Manila at that time ‒ for example, the 1905 Burnham Plan ‒ show the existing esteros (inlets) and streams, one map titled Plano de la Plaza de Manila is unique in showing the proposed construction of a canal network in Manila in the 1880s.

One cannot understate the uniqueness and potential of this manuscript map in terms of the planning of Manila. Held in the National Library of Australia (NLA), (3) the map does not specify its author. According to the NLA it came from the collection of the art collector and dealer Rex Nan Kivell, who did not keep a detailed record of its provenance.

Detail of Ynundacion east of Hermita from Plano Topográfico de Manila y sus Contornos by Tomas Cortes, (1823) 1826 (image courtesy of Archivo Histórico de la Armada - J.S. de Elcano / Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa )

Anonymous Plano de la Plaza de Manila , (1863 -72) 1884 (image courtesy of National Library of Australia )

Detail of the network of canals on both sides of the Pasig River from Plano de la Plaza de Manila (image courtesy of National Library of Australia )

The map is dated 1884, but the date has been added in pencil a little off center from the title and I believe the map was in fact made between 1863 and 1872. The map features a Puente de Barcas (pontoon bridge) over the Pasig River that was built only after the earthquake in 1863 had destroyed the earlier Puente de Piedra (stone bridge). But it must pre- date 1872 as it does not show the two Ayala Bridges crossing the Pasig River via the Isla de la Convalescencia (sic ) or other details (such as the development of the Calle Azcarraga ) shown on contemporary maps of Manila , for example the 1882 inset plan of Manila by Antonio Olleros ( 4)

The Notas (Notes) section of the map in the lower- right corner gives details of the proposed canal system in Manila, as follows:

1. Los canales que aparacen se proponen en ver de los esteros que hoy exsisten tienen 25 metros de ancho y sus andenes 20 (the proposed canals through the inlets are 25 meters wide with 20meter easements on each side).

The canal system features three circumferential canals and five radial canals forming a network. The first circumferential canal, located only on the southern side of the Pasig, is the nearest to Intramuros; it separates Intramuros from Ermita and runs fro m the Pasig at the Barrio de la Concepcion to the northern edge of Ermita. The second circumferential canal runs eastwards on

of the Isla de Convalecencia from Manila y Sus Arrabales by Anselmo Olleros, 1882 (image courtesy of Archivo del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Madrid

Detail

the northern side of the Pasig from San Nicolas, alongside Binondo Church and the rear of Quiapo Church, passing near San Sebastian Church before heading south and reaching the Pasig just to the side of San Miguel Church. On the southern side of the Pasig, this canal continues beside Sitio de Tanque and the Paco Cemetery to the southern edge of Ermita , where it exits into Manila Bay.

The third circumferential canal runs on the northern side of the Pasig in a slightly zigzag manner from Tondo, past undeveloped parts of Santa Cruz and Sampaloc , until reaching the Pasig in San Miguel beside where Saint Jude Catholic School is located today. On the southern side of the Pasig, the canal starts at Pandacan, passes Paco and exits to the Pasig at Malate.