www.dentalabstracts.com

www.dentalabstracts.com

Editor-in-Chief

Douglas B. Berkey, DMD, MPH, MS

Senior Publisher

Annie Zhao

Journal Manager

Sangamithrai S

Abstract Writer

Elaine Steinborn

© September 2025, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the publisher.

Publication Information Dental Abstracts (ISSN 0011-8486) is published bimonthly by Elsevier Inc., 1600 John F. Kennedy Boulevard, Suite 1600, Philadelphia, PA 1910, United States. Months of publication are January, March, May, July, September, and November.

Customer Service Office: 11830 Westline Industrial Drive, St. Louis, MO 63146. Periodicals postage paid at New York, NY, and additional mailing offices. Annual subscription rates for 2018 (domestic): $144.00 for individuals and $71.00 for students; and (international) $194.00 for individuals and $105.00 for students.

USA POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Dental Abstracts, Elsevier Health Sciences Division, Subscription Customer Service, 3251 Riverport Lane, Maryland Heights, MO 63043.

Copyright 2025 by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Dental Abstracts is a trademark of Elsevier Inc. Dental Abstracts is a literature survey service providing abstracts of articles published in the professional literature. Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented in these pages. Statements and opinions expressed in the articles and communications herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Editors or the publisher. The Editors and the publisher disclaim any responsibility or liability for such material. Mention of specific products within this publication does not constitute endorsement.

All inquiries regarding journal subscriptions, including claims and payments, should be addressed to: Elsevier Health Sciences Division, Subscription Customer Service, 3251 Riverport Lane, Maryland Heights, MO 63043. Tel: 1-800-6542452 (U.S. and Canada); 314-447-8871 (outside U.S. and Canada). Fax: 314447-8029. E-mail: support@elsevier.com (for print support); support@elsevier.com (for online support).

Notice: Journals published by Elsevier comply with applicable product safety requirements. For any product safety concerns or queries, please contact our authorized representative, Elsevier B.V., at productsafety@elsevier.com

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds or experiments contained herein. Health care practitioners must exercise their professional judgement and make all treatment-related decisions based solely on the specific conditions of each patient. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, independent verification of diagnoses and drug dosages should always be made.

The content is provided “as-is” and Elsevier makes no representations or warranties, whether express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of any content. To the fullest extent permitted by law, Elsevier assumes no responsibility for any damages, adverse events, or liability arising from use of information contained herein including for any injury and/or damage to persons or property, whether as a matter of product liability, negligence or otherwise.

Inclusion of any advertising material in this publication does not constitute a guarantee or endorsement of the quality or value of such product or service or of any of the representations or claims made by the advertiser.

DentalAdvance .org is the gateway offering high-quality research, news, jobs and more for the global community of dental professionals.

Journal profiles with quick links to Tables of Contents, author submission information, and subscription details

Important information and valuable resources on how to submit a journal article

Dentistry Articles in Press from participating journals

Quick links to the leading dentistry societies worldwide Dentistry News from Elsevier Global Medical News (formerly IMNG)

Dentistry Jobs powered by ElsevierHealthCareers.com

Editor-in-Chief

DouglasB.Berkey,DMD,MPH,MS ProfessorEmeritus, SchoolofDentalMedicine, UniversityofColorado, Aurora,Colorado

AssociateEditor

DanielM.Castagna,DDS AssociateProfessor,DepartmentofPreventiveandRestorativeDentistry, UniversityofthePacific,ArthurA.DugoniSchoolofDentistry, SanFrancisco,California

P.MarkBartold,DDSc,PhD,FRACDS(Perio) ProfessorEmeritus SchoolofDentistry, UniversityofAdelaide Adelaide,Australia

RobBerg,DDS,MPH,MS,MA ProfessorandChair, DepartmentofAppliedDentistry, UniversityofColoradoSchoolof DentalMedicine, Aurora,Colorado

TylerH.Berkey,DMD GeneralDentist Aurora,Colorado

FionaM.Collins,BDS,MBA,MA ConsultantandEditor, GeneralDentist Longmont,Colorado

AnthonyJ.DiAngelis,DMD,MPH ChiefofDentistry, HennepinCountyMedicalCenter, Professor,UniversityofMinnesota, SchoolofDentistry, Minneapolis,Minnesota

RaulI.Garcia,DMD,MMedSc ProfessorandChairman, DepartmentofHealthPolicyandHealthServicesResearch, BostonUniversitySchoolofDentalMedicine, Boston,Massachusetts

MichaelSchafhauser,DDS GeneralDentist, St.Paul,Minnesota

JoeVerco,DClinDent PaediatricDentist NorthAdelaide,Australia

VOL.70 No.5

EndodonticCare Hands-On ArticaineAllergies377 TrueAllergytoArticaine

IndirectPulpCapping

SwimmingandTeethStaining386

DentalStainingandSwimmingExtentand Intensity

WaterlineTesting387 HowToShockandTestDentalWaterlines

WhiteCoatHypertension389 BloodPressureDiscussionsintheDentalOffice Inquiry

Mouthwashes392

ChoosingaMouthwash

Oral/SystemicConsiderations394

EconomicEvaluationsofPeriodontal TreatmentforType2DiabetesPatients

PosttraumaticStressandPoorOralHealth

OrofacialPain396

InitialTherapiestoRelieveOrofacialPain MeditationPlusTetracyclineforAphthous Ulcers

TMJ/SleepDisorders398 RelationshipsBetweenTMJDysfunctionand SleepDisorders

WeightedBlankets399 AcceptabilityandEffectivenessofWeighted BlanketsforPediatricDentalCare

WaterFilterTesting401 WaterFilterPitcherPerformance

404 Sleep andHowtoupYourShare WhattoPackforVacation

Notes

TofacilitatetheuseofDentalAbstractsas areferencetool,allillustrationsandtablesincluded inthispublicationarenowidentifiedastheyappear intheoriginalarticle.Thischangeismeanttohelp thereaderrecognizethatanyillustrationortable appearinginDentalAbstractsmaybeonlyoneof manyintheoriginalarticle.Forthisreason, figure andtablenumberswilloftenappeartobeoutof sequencewithinDentalAbstracts.

StandardAbbreviations

Thefollowingtermsareabbreviated:acquiredimmunodeficiencysyndrome(AIDS),humanimmunodeficiency virus(HIV),andtemporomandibularjoint(TMJ).

Doing nice things for other people feels good, but it feels even better when you do these things for no reason other than how it feels. Giving with authenticity beats giving with expectation, and the results of your generous giving will benefit everyone involved. The term esprit de corps is defined as sharing feelings of pride, fellowship, and loyalty among members of a group. This feeling is an essential component of generosity in an organization and must be modeled by the leader of the group. Having a mindset of abundance rather than scarcity and blending generosity into everything you do are attitudes that can contribute to a successful and satisfying personal and professional life.

Living generously tends to result in a generous return to you. This abundance mindset opens up opportunities that enrich your life. In contrast, acting from a scarcity view will lead to a paucity of opportunity and a withering of your organization as it reflects your cynicism and undermines those who work with you. Cutthroat conduct in business is always outdone by goodwill and generosity.

Generosity

The esprit de corps that you want to focus on is caring more about the well-being of employees and patients than about any other concern. Care for your employees will trickle down to these workers providing better care for patients, which leads to growth in your practice. Doing things that interfere with this cycle can compromise the results.

Generosity doesn’t mean giving patients a pass on their unpaid bills, because those who provide care, such as dentists, deserve to be paid. If you see a patient is struggling to pay, you can offer to work with him or her on a payment plan that fits his or her situation.

People who don’t ascribe to being a giver can take advantage of your kindness and goodwill. As a result, you may back off so you won’t be subjected to the pain of these incidents. People tend to fall into the categories of a giver, a taker, or a matcher. Givers give without expectation, takers take without limitation, and matchers value reciprocity. Most dentists are matchers who give often but attach strings to guard their self-interest. This protects them from the takers and keeps them safe, but whether this is the right thing to do depends. How you express your generosity and how you respond to skeptics, takers, and matchers will vary depending on your temperament. The best approach is to be upbeat and high energy. Having an eager anticipation regarding daily life and serving others can be your attitude both in business and in your personal life. This leads to an enduring willingness to help in any way you can.

The first step toward being generous is getting sufficient sleep and proper nutrition and taking care of your mental health. With these elements under control, your ability to be generous can thrive. You are content and can give freely without expectations because your needs have been met. Interactions with others can be a generous act that you get to enjoy, that allows you to embrace the camaraderie and collaboration, and that yields satisfaction related to having done a job well.

This mindset also draws people like you into your circle, which enhances your enjoyment of life. Others will continue to join in and outnumber the takers who might try to sabotage your joy.

People can tell when someone isn’t generous but instead is focused on the strings that are attached to his or her giving. It’s important to give without expectation so that you won’t be disappointed by others’ unwillingness to reciprocate.

Start the day well-nourished, rested, and in a good mood. Let this positive beginning carry you through the day, and spend your time helping others. This will make you successful and encourage the growth of your dental practice. Focus on what you can do for others, and eventually others will do the same thing for you. You will learn to consider every new blessing simply a bonus.

Murphy MB: Building a legacy of generosity: The power of giving. Dent Econ 115:54, 57, 2025

Reprints not available

Changes in health behaviors tend to gradually develop rather than take hold quickly. Sports, in particular, have proved resistant to change or at least slow to adopt health measures. For example, professional hockey players have seen damaged or missing teeth as a badge of honor or simply part of the game for many years. In 1979, the National Hockey League required all players entering the league to wear helmets, leading one coach to blame the “intellectual liberals” for demanding changes when he couldn’t recall any recent head injuries occurring during hockey play. Today, nearly all combat sports require mouthguard use to protect players’ orofacial integrity. The role of sports in mouthguard use and the value of wearing mouthguards were discussed.

National Basketball Association (NBA) star Steph Curry is widely known for his ability to sink long-distance (3-point) shots with unique skill. He is also widely known for how he keeps his mouthguard moving, removing it, readjusting it, and voraciously chewing it during any pauses in play. He’s been ejected from 3 NBA games in his career, with the infraction being throwing a mouthguard. Curry has likely influenced younger players to mimic not just his shooting form but also his distinctive mouthguard mannerisms. It’s

possible that he has protected children and youth basketball players from more chipping and tooth avulsions than any dentist has ever restored.

As mouthguards led to a widespread need for mouth protection during sports, many clinicians offered guidance regarding how to fabricate well-fitting sports mouthguards. In addition, more youth and college sports organizations now require mouthguard wearing because of their ability to protect against orofacial injuries during play. No conclusive evidence indicates if they protect against concussions, and little evidence shows that they improve athletic performance. Mouthguards are fun because they can be customized and allow athletes to create unique expressions in an atmosphere where regulations regarding uniforms and equipment tend to be strictly enforced.

Most professional athletes in high-impact sports now wear mouthguards, even if they aren’t required. This practice tends to trickle down and influence younger athletes.

Mouthguard use is seen by the American Dental Association as an appropriate requirement for 29 sports. As yet, no major basketball governing body requires them, but most NBA stars wear them voluntarily.

Seeing sports heroes wear protective gear such as mouthguards tends to exert a positive influence on youth sports participants. Even Steph Curry may be considered an honorary oral health advocate for his obvious engagement with his mouthguards. Taking up the wearing of mouthguards protects the teeth as well as other oral structures, which are vital areas of dental concern. Anything that promotes their use during hazardous sports participation is performing a valuable service.

Chaffee BW: Saving teeth, three (points) at a time. J Calif Dent Assoc 53:2477096, 2025

Reprints available from BW Chaffee, Univ of California San Francisco School of Dentistry, San Francisco, CA, USA; e-mail: benjamin.chaffee@ucsf.edu

The Trump Administration health care platform, Make America Healthy Again (MAHA), is designed to reform the health care system to focus on reducing chronic disease, prioritizing preventive health, increasing transparency in medical research, and restructuring federal programs. The American Dental Association (ADA) should be involved in these efforts, focusing on the specific aims of MAHA, how to advance the dental profession, and the importance of integrating oral health care into the proposed plans. A look at the priorities of MAHA and at the trajectory of oral health care in America’s future was taken to identify where progress is needed.

With the emphasis on chronic disease prevention, childhood health, lifestyle, diet, and nutrition, we face a significant opportunity to integrate oral health care more directly into national health policy determinations. Oral disease causes the United States economy a loss of $46 million each year. Prevention efforts are needed to address this problem.

Major Medicaid restructuring has been planned, with particular focus on funding reforms and restricting eligibility. These efforts risk a reduction in dental benefits coverage for lowincome families and are not in line with the evidence that supports the value of dental benefits in Medicaid programs. Coverage is essential to ensure better oral health, improve overall health and wellbeing, lower health care costs, and advance employment prospects.

Expansion of the Medicare Advantage (MA) programs is also planned. MA plans cover about half of the US population age 65 years or older, and most offer some dental coverage. Because challenges remain in these dental coverage plans, the ADA should advocate for better coverage standards, more transparency, better choices for consumers, and more equitable policies governing provider payments.

The safety and efficacy of community water fluoridation are being widely targeted for reform. The best available data and research must be incorporated into any decisions in these areas. Dental practitioners can participate in these efforts by spreading the word about the efficacy and safety of fluoridation, touting the science behind the practice, and educating both the public and policymakers about the effect of fluoridation on dental and overall health. With potential cutbacks coming in research funding, the ADA should ensure that efforts in oral health−related research remain strong.

At this point in time, we have the opportunity to incorporate oral health into overall health care, making it an essential part of the picture. The 4 key areas requiring our attention are dental insurance reform, oral health literacy, workforce issues, and prevention.

Dental care has the highest cost barrier levels, especially for adults. The current dental insurance model doesn’t function

properly. Areas requiring the most attention are the limits of annual benefits, the high costs patients must pay, the poorly structured administrative processes, a lack of transparency, and unregulated insurer loss ratios, but other areas must also be addressed. Coverage for the range of services needed to reach and maintain optimal oral health levels and the provision of adequate funding in US public insurance programs require reform as well. Dental care should be classified as an essential element in overall health and therefore worthy of proper coverage in insurance plans.

The extensive evidence supporting the linkage between oral health and overall health must be incorporated into the lives of everyday people, moving them toward taking preventive and health-affirming action. Persons who have chronic diseases such as diabetes, pregnant women, and those at risk for cognitive impairment such as Alzheimer disease must be established in a dental home so they can understand the link between oral and overall health and be supported in oral health behaviors.

A robust dental workforce of dentists and dental team members is needed to deliver the care required by US patients. This will require stronger efforts to recruit and retain dental care professionals and to overcome workforce shortages. Programs that train, develop, provide pathway initiatives, address loan repayment, and provide scholarship opportunities for dental team members in areas with inadequate dental coverage, including rural America, should also be established to ensure the future workforce will be adequate to the need for care.

Too many people in the United States don’t come for dental care until they experience infection and severe pain, which requires care that is more expensive than accessing ongoing care. With regular dental visits, dentists and dental hygienists can prevent many problems and save money for the US health care system. This pattern of dental care avoidance behavior is especially seen among low-income adults. Visiting the dentist regularly, brushing twice daily with a fluoride-containing toothpaste, flossing, eating foods low in added sugars and without ultraprocessing, and avoiding tobacco and alcohol products are behaviors that can reduce caries and inflammation.

The MAHA agenda is still in its infancy, so the ADA must remain engaged in efforts to include oral health as a national priority. It’s vital to ensure that oral health is seen as an essential ingredient in the overall health care structure that emerges from this new agenda. Achieving overall health for America will require a strong focus on oral health.

Kessler BH, Rosato RJ: Make American healthy again: What it could mean for oral health. J Am Dent Assoc 156:265-266, 2025

Reprints available from BH Kessler, American Dental Assoc, 401 N Michigan Ave, Suite 3300, Chicago, IL 60611-4250; e-mail: kesslerb@ada.org

Many dental professionals are hesitant to proactively introduce cosmetic options to patients. They may feel they’re overstepping or aren’t considering the patient’s affordability issues. They may also lack training and be uncertain how to confidently present these options. As a result, these practitioners miss the opportunity to improve both the patient’s life and the health of the dental practice. Patients may lack a clear understanding of cosmetic options and often won’t ask about them, instead making assumptions regarding cost or appropriateness of the cosmetic procedure. To overcome these issues, a plan was offered that addresses patient issues, offers a visualization approach, and promotes an understanding of the value cosmetic dentistry has for patients and dental practices.

Patients often make assumptions regarding cosmetic dental care based on a lack of knowledge, whether that involves the value of a confident smile, a misunderstanding of the dentist’s silence on the issue, their own self-perceptions or personality traits, or other issues. Most patients hesitate because of this lack of knowledge. Dentists may be waiting for the patient to initiate the conversation, creating a missed opportunity for care.

Having a confident smile can be powerful, enhancing self-esteem, confidence, personal relationships, and career success. However, many patients are unaware of the value they could see with a smile makeover. This extends beyond their personal enhancement to affect their interpersonal and professional interactions.

Often patients want a better smile but because the dentist is silent on the possibility, they assume that it’s not an option for them. They may assume that cosmetic procedures are only appropriate for people with severe dental issues or those who have a strong sense of their image. As a result, patients may see cosmetic treatment as only appropriate for those who are disfigured or vain, making it unnecessary as far as they are concerned.

Self-perceptions and personality traits can prevent patients from considering cosmetic treatments. Many don’t understand the impact even small enhancements can have. This may include whitening, bonding, or alignment correction. Both the patient’s appearance and his or her self-esteem may be impacted.

Overall, patients don’t ask because they aren’t aware of what’s possible, they forget to mention their interest, or the topic simply never comes up. The treatments are assumed to have a certain value only for certain patients.

Because patients don’t recognize what they don’t know, dentists need to take the initiative and show the patient the potential transformation that can be achieved and why it’s worth investing in. Visual tools such as intraoral photographs, scans, and artificial intelligence−powered radiologic detection software can simplify the clinical information and help patients better understand their oral health. The full-face smile simulation allows patients to see their potential transformation.

The full-face smile simulation is a natural-looking digital smile preview. Such simulations can be presented casually, yet they are a powerful tool to evoke emotion in the patient as well as a desire to engage in the experience. When patients see themselves with an improved smile, the procedure becomes more personal and impactful. This gives the patient some of the information needed to visualize outcomes and to be more confident and able to move forward with treatment.

For patients who assume full-arch reconstruction is too expensive, the dentist can show a side-by-side digital simulation of their current and potential smile. Seeing the transformation taps into emotions that drive buying decisions for procedures that will make them feel rather than those that are driven by logic.

Patients are more likely to accept costly treatment when they recognize the cosmetic benefits they will experience. Seeking care for worn teeth, bite issues, or missing teeth often leads the patient to view cosmetic procedures as needed repairs. Seeing the restorative effect on the smile makes the investment more satisfying, especially if full-arch reconstruction is done, when both enhanced oral function and significantly improved confidence and appearance result. Dental professionals can present the functional treatments as a health solution and a cosmetic enhancement, which shifts the focus from cost to value and increases the attractiveness of the process for the patient.

The financial impact of offering cosmetic dentistry can include significant growth opportunities. Practices offering cosmetic procedures have higher revenue, increased practice valuation, and higher profitability levels in the eyes of dental service organizations looking to purchase the practice.

Long-term financial health is also improved. The patients who receive cosmetic procedures are more likely to remain with that provider and agree to additional care from him or her. They also engage more often in preventive and restorative care and will refer others to that practice.

To overcome psychological and operational barriers to offering cosmetic dentistry will require the right approach, tools, and a proper mindset. This will allow for cosmetic conversations to take place. The specific ways to manage challenges include the following:

1. Implicit bias, where dentists assume only certain patients are interested. The solution is to make every appropriate patient a candidate for smile enhancement discussions.

2. Treatment inertia, where providers worry they will sound like a salesman. The solution is to shift their mindset from selling to educating.

Attracting great dental team members is based on principles related to career success, both short-term and long-term. Among the components of this process are the foundational goals of the practice. It should have high production levels, with a yearly increase in production goals. All the team members should come to work every day with an ownership mentality and pride in their work. Finally, the dentist should have a plan in place to reach financial independence at a specific age. Gathering an excellent team for the practice will require care in conducting the hiring process, in providing a structured interview, and in offering supportive onboarding techniques.

When a team member leaves the practice or isn’t performing at a satisfactory level and is let go, the dentist must have a strategy in place for seeking an excellent replacement, use ad language that targets the desired respondents, ensure good relationships exist

3. Workflow integration concern, where practitioners resist incorporating new technology. The solution is to make it easier to add digital smile previews to case presentations as standard practice. The practice may be to take a full-face, natural-smile photograph of each new patient.

Patients and dental practices both benefit from cosmetic dentistry. Patients become more confident and have renewed self-esteem when they undergo even minor improvements in their smile. Practices have more case acceptances and grow when dentists initiate the conversation about smile improvement. Using the digital smile simulations can break down barriers to these conversations and give the dentist the opportunity to explain the value of such treatments. Cosmetic dental approaches become a natural component of oral health care.

Reprints not available

with the remaining employees, and screen to eliminate people who aren’t the right fit.

Dentists should be proactive in defining how their practice will reach potential hires. Successful recruiting should result in potential hires who are eager to schedule interviews and get the job.

It’s essential to craft an ad focused on the types of individuals who would make good additions to the dental team. High-quality team members can become or may already be world-class performers. Often these individuals want to make a difference in the lives of patients. They desire a positive work experience with good team interactions that offers interesting, challenging, and rewarding employment. They aren’t in it for the paycheck but are energized and enthusiastic about the work, the team, and the environment where they will function.

The dentist should view team members as colleagues and not employees or subordinates. They should be encouraged to improve their patients’ lives and be proud to do their jobs.

A telephone screening should be instituted to determine if an individual would make a good candidate for the open position. Specific questions should be formulated to identify people who are or aren’t a good fit for the practice.

The interview should consist of 3 parts, with the first part focused on the candidate, the second part on the practice, and the third part making an offer of employment if the other parts go well. Although the ideal would be to conduct separate interviews for each of these topics, today’s tight labor market makes it essential to move quickly.

To learn about the candidate, the dentist should ask about his or her background, interests, strengths, weaknesses, and personality. People try to make a good impression during the interview, so the dentist should ask lots of questions and allow the candidate to talk at least half of the time to get to the person’s authentic personality. A checklist can be kept to guide this process of seeking to know the candidate more deeply as quickly as possible. It’s wise to ask questions that may be unexpected, such as what the person dislikes about his or her previous job.

The information given regarding the practice should create a positive image and outline the dentist’s vision for the practice going forward. It’s important to explain the mission of each employee and why he or she would come to work each day. Defining the culture of the practice should also be a part of this presentation. Many people desire to have more than a job and seek to belong to something special where they can contribute, will be welcomed by other team members, and will have support.

The dentist should be aware of how he or she feels during the interview. It’s important to hire someone who is the right fit even if he or she is less skilled than another, less likeable candidate. Personality and attitude can indicate whether an individual is a good fit for the practice.

The dentist should be prepared to make an offer. This includes knowing how much to offer, which can be based on what is being offered in online advertisements by other practices. The dentist should ensure that any offer is in line with current team compensation to avoid disruption in the team.

How an employee is onboarded will determine how they will perform. During the first 100 days of employment, the new team member will learn how the practice works, what the team is like, and the aspects related to the practice’s culture. The dentist should meet with new employees regularly to ask how they’re doing and offer any guidance or support that is needed. With this ongoing training and support, new employees will be given the foundation for performing at an exceptional level.

Excellent leadership is required to interest excellent employees in applying for an open position. The dentist should be prepared and not rush into hiring a warm body. He or she should set the parameters of the practice, the existing team, and the fit of any new employees. Taking steps to ensure that the team works well together and the new employee is given the opportunities to excel in the position will tend to yield a successful practice that is marked by less stress and more desire to invest in delivering excellent patient care.

Levin RP: How to attract a great team. Dent Econ 115:11-12, 2025

Reprints not available

Most dentists don’t build a hiring pipeline and are unprepared when they need to hire someone. At that point, dentists can be stressed and panicky, sometimes leading to poor hiring choices to avoid being short-staffed. Being proactive in hiring can allow the dentist to relax and choose an employee from the hiring pipeline who will fit well with the existing staff. The dentist must continually promote the practice as an excellent workplace and build relationships with local dental professionals and those who could become dental professionals. Team members should be reassured that this philosophy doesn’t mean you are looking to replace them, but is simply preparation for future needs. Several strategies can contribute to networking and help the dentist focus on cultivating a team of potential employees.

It’s important to establish that this practice is not only positive and supportive but is an outstanding place to work. The dentist should celebrate team members publicly, with clear expressions of his or her appreciation for the employees. Included in these ads, signs, or social media should be the assurance that the practice always welcomes new employees and patients. Social media for the practice should include fun, informal moments for the dental team. This is attractive to both patients and potential employees.

Employees should be engaged in team-building events. The dental practice may host charity races, volunteer activities, or other opportunities to build camaraderie. Local media should be contacted if photo opportunities exist.

In addition to conveying appreciation to the team, the dentist should give each employee rewards and recognition for excellent performance. If the team goes out together, they should wear branded clothing so the practice will be associated with their rewards.

The dentist should focus on finding experienced or credentialed employees who embrace growth. Often these people attend meetings of associations, conferences, and study clubs. The dentist may teach classes, host continuing education classes or

events, sponsor association events, or mentor students in local hygiene or dental assisting programs. The team may also be involved in scouting out potential colleagues when they attend conferences or other events. They may be given a referral bonus if they recruit a successful candidate. These activities build the dentist’s reputation as a supportive and accessible employer and establishes the practice’s reputation as a good place to work.

If candidates are few, the dentist may have to be willing to train potential team members. Working in an area other dentistry isn’t a barrier to being hired. Those who demonstrate exceptional customer service skills in retail, hospitality, or health care situations, for example, may become valued employees in the dental office. The dentist should take note of those who provide this degree of customer service in any situation and invite those who seem to be a good fit to come as patients. If they seem to be a good fit for the practice, the opportunity to work with the team may be offered.

Taking the time and effort to perform all the suggested strategies to reach out to excellent workers should create a pool of potential employees for the dental practice. The dentist should nurture these relationships and build connections, which can be strengthened by sending check-in e-mails periodically or offering holiday or birthday wishes. The dentist can also refer them to colleagues or invite them to events at the practice.

By building a pipeline of potential employees, the dentist can be prepared for the unforeseen loss of an employee and protected from the stress related to short-staffing. Taking these proactive steps can relieve stress and assure excellent patient care.

Weiss S, Perez H: 5 creative ways to “always be hiring” for your dental practice. Dent Econ 115:13-14, 2025

Reprints not available

When there are fewer patients and empty schedules, the dental practice can suffer from a poor bottom line. Returning to the fundamentals is a way to encourage patients to fill those empty chairs and improve the business stats. Several strategies can be used to reach out and draw patients back to their routine dental care or to encourage people who have neglected their oral health to check out your practice.

Returning to the basics can have a significant effect on the production of a dental practice. Strategies to use in the slow times vary from offering new services to revitalizing tried and true ways to encourage patients to come back to their dental home.

Offering only the basics means missing out on opportunities to capitalize on patients’ desire for more options and newer approaches. Adding cosmetic dentistry, clear aligners, dental implants, or sleep apnea treatments can differentiate your practice from others. Including big-ticket and specialized services can attract new patients who want more ways to improve their image. Even adding a free educational workshop or 2 to introduce patients to dental implants or orthodontics will showcase your expertise. Another free service is teledentistry consultations. Virtual interactions can allow patients to try you out without making an in-office visit.

Special pricing and discounts become especially alluring when money is tight, so patients may be eager to save some money. In addition, health savings account balances often must be used or lost, which can encourage patients to book some dental care rather than lose out on their health care bucks.

Referral programs are especially attractive because they encourage current patients to spread the word about the great dentist they have. Incentives for referrals can include a free service or discount. Spreading the word through an e-mail blast or social media post can also net some new leads. Adding a loyalty program that rewards repeat patients can increase the level of success.

You need to take a good look at your practice to see if it’s a place that feels welcoming and comfortable. If it isn’t, now may be the time to spiff up the furniture, add free Wi-Fi or coffee, or paint. Small touches to personalize care for each

patient can make all patients feel valued and remain loyal to the practice. When patients are feeling comfortable and happy, it may be time to ask for a referral or hand them a referral card to complete. Staff members can also be incentivized to make referrals by offering bonuses for successfully spreading the word.

To help patients stay on track with their dental care, you can offer automated referrals vial e-mail or text messages. Patients who miss an appointment can be quickly contacted to fill an empty slot. Having a consistent communication with patients keeps you on their minds. This may include sending out a monthly or quarterly newsletter highlighting new services, promotions, or dental team news, which can encourage patients to stay connected with you.

Your social media campaign should include patient testimonials, before-and-after photographs, and perhaps behind-the-scenes looks at the office. Social media offer easy, free ways to communicate with patients.

Patients who haven’t come in for 6 months or longer may need the push a reactivation campaign can supply. This may be a friendly phone call or e-mail or even a letter to remind them of the need to restart their care. Let them know that you’re still there and ready to help them—and adding a special incentive may seal the deal.

Patients may hesitate to schedule appointments because of the cost, so having flexible payment options can ease their minds. This may involve prepay discounts, an in-house payment plan, or third-party financing, but having a way to make payments easier and more manageable can keep patients coming back. Each patient should have access to all of the available options and should be given simple explanations of how they work. Once they feel they have control over their payment options, patients are more likely to agree to have major procedures.

Membership plans help both insured and uninsured patients by offering affordable and flexible options for dental care. The plans encourage members to stay with the practice especially during slow times, because they recognize the value they are getting. Signing up for the plan can include special offers and use patient testimonials to show how helpful they are.

Patients may be unaware of how great your services are, so it’s time to leverage modern technology so patients can visualize

their dental needs. This can include intraoral cameras or digital imaging—whatever makes them understand the value of your care. Patients need information and explanations to understand the value, so taking time to educate patients, telling them the what and why about each procedure suggested, can pay off in greater trust in your expertise and more acceptance of treatment plans.

Being present in your community is another way to connect with patients and the area where you practice, but it also testifies to the good you are doing for others. You may also want to sponsor local events, set up a booth at a health fair, or host an open house. People who see your name and face associated with good works are more likely to choose you as their dentist.

Slow times don’t last forever, so there will be an end to the challenges they present. Seeing down times as an opportunity to get back to the fundamentals and tune up your systems is a good perspective and helps to engage with current and potential patients. Improving the business’ presence in the community and keeping your name front and center will help to turn the slow times into highly productive seasons.

Wells B: Slow times call for proven measures, Inside Dentist 21:8, 10, 2025

Reprints not available

Having an internal employee manage brand recognition and public perception can be an excellent way to build trust with patients. This employee would manage social media marketing efforts, then develop the ability to helm campaigns that ensure the brand of the dental practice is well-publicized and wellregarded in the community and the dental world. The process of developing an in-house marketing manager was tracked.

The employee tasked with marketing responsibilities should demonstrate loyalty, be genuinely interested in marketing, understand social media, and be a trusted team member. Specific skills he or she should possess include being able to respond to reviews and comments quickly and professionally while using the practice’s voice; having skills in design and a sensitivity to meaningful moments worth sharing; demonstrating the ability to plan and execute content, organize community events, and build relationships with vendors and local media without the dentist’s hands-on oversight; and being excited to learn new skills and use marketing tools that both benefit the dental team and keep the practice current.

Beginning with a few extra hours a week, the employee should be able to manage the essential marketing tasks, including keeping the practice website and Google listing updated and accurate,

managing responses, and creating basic social media content. Posts 3 to 4 times a week can keep the relationship between the practice and patients solid and impactful. Content can include profiles of the providers with current pictures, patient testimonials (with consent), features about services, and contests.

Having an in-house manager allows for ongoing engagement, quick responses to reviews, control over the brand’s appearance and perception, and updated websites and business listings when there are changes in staff, hours of operation, or services offered. Patients will want to see how the practice responds to negative reviews or pubic social media complaints. The marketing manager can discuss these situations directly with the practice owner and employees and post quickly. This individual knows the patients, dentistry, and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) protocols. Having this internal manager allows the dentist and other dental staff to continue to focus on providing needed dental care rather than having to spend time on marketing.

Even when the manager is only functioning on a part-time basis, results can be seen. These include growth in the follower pool, having people engage with content through likes and shares, and providing reviews more often. Compensation for the manager’s efforts can include an increase in hourly pay commensurate with the new responsibilities. This conveys the dentist’s confidence in the manager’s abilities and supports his or her passion to grow both personally and as a practice employee.

With expansion of the manager’s role and the practice’s engagement, the dental team may be free to reach beyond fundamental tasks into more sophisticated strategies. The marketing manager will have expanded responsibilities, including arranging for community engagement, creating and maintaining a consistent brand voice, managing digital advertisements, and running targeted campaigns. The platform analytics can be tracked, and more complex video and educational content can be developed.

The practice should provide for the professional development of the marketing team member through certifications and dentalspecific education. The creation of social profiles and business profiles, website management, and content development are free or cost little. Making these internal investments will provide more authentic results with less outlay for marketing.

Growth in the dental practice can be readily seen and appreciated. The practice will expand, existing patients will remain loyal, and rates of engagement will be beyond expectations. With the growth in followers across the social media platforms, the

practice can expand locations and services, allowing it to reach more patients and provide dental care to them.

Most practices underestimate the value and need for internal marketing, and persons with advanced skills in these areas are rarely seen. However, the internal marketing manager role is becoming critical for growth and success. Having a dedicated employee who can implement a flexible marketing plan will encourage the retention of current patients and expand the new patient population. Through investments in staff and the expansion of marketing capabilities and responsibilities, the practice can see a costeffective growth in its ability to engage with more patients and provide optimal care opportunities.

Nona J: The in-house marketing manager. Dentaltown 26:50-53, 2025

Reprints not available

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools can be used to target patients for marketing messages, personalize content, and analyze phone calls, among other tasks. The use of patient avatars can help the dental office improve many aspects of marketing and patient service, such as creating content, tailoring ads to the patient population, providing valuable feedback, responding quickly without bothering a busy office team member, and tracking calls to identify patterns.

You should begin by uploading an anonymized patient list. It’s vital that all of the data uploaded have been stripped of any personally identifiable information to maintain compliance with Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements. The anonymized information can include demographics, treatment types, and zip codes, which can yield important insights without compromising patient identity. AI can then track patterns such as patient preferences, patient behaviors, age, income, and spending habits and create a patient avatar with the important characteristics of your patients. This “character sketch” of your ideal patient can be used to fashion an

appropriate dental website, create targeted social posts, and even answer the phone in ways that focus on patient needs.

The avatar can also run a check on your website to see if it addresses your target patients’ needs. AI can then give you suggestions for making adjustments that will achieve maximum appeal.

In addition, if your front desk team is busy juggling calls, checking in patients, and handling paperwork, AI chatbots can be trained to answer common questions, book appointments, and provide information about services. Patient calls are answered quickly, which has been shown to be an important feature for 85% of people, whose loyalty can be improved if the practice responds to calls quickly. The chatbot is like having an extra team member who is always available.

It can be taxing to come up with social media content and can require a considerable investment in terms of time. AI can be tasked to fulfill your goal, such as attracting patients who would want implants. AI can create a social media calendar so you have a

30-day dental social media strategy that includes ideas to post, hashtags, and visual suggestions. AI can suggest a mix of educational posts, patient testimonials, and reminders about the benefits of implants. The posts can include short videos or before-and-after images. All are created based simply on your instructions. You should still review it to make sure this approach feels natural. Some AI-generated content can feel too polished or stiff, so you may want to adjust it to make it feel real and relatable.

When crafting ads on Google or social media, it can be challenging to find the right words. AI can generate digital ad copy that fits your audience, giving you several versions. You can test out the variations, ask AI for alternative headlines, and receive tips on which keywords should be targeted.

AI learns from your feedback, so you may not want to simply accept the first response you get. With more feedback, AI offers better choices, eventually giving you just what you’re looking for.

For ChatGPT or any AI tool that is providing unacceptable responses, you should give them a “thumbs down” or simply respond that you don’t like that response. You are then directed to a feedback panel where you can register what you don’t like, if the response wasn’t on target, or if it seemed lazy. The feedback encourages AI to improve and give you more of what you want.

If you are using AI for phone calls, it has the capability of listening to the calls and providing detailed insights. Using real-time call

tracking, AI can review conversations and suggest patterns in patient questions, objections, or scheduling preferences. Reasons for missed appointments may also be identified. All of these insights can help in refining responses, adjusting language in marketing pieces, and handling common questions proactively. This saves time by summarizing what matters the most to you.

The prices of AI tools vary widely. Some AI tools are free and allow you to experiment with patient avatars or create content. If you’re trying out a subscription and in the free trial period, you can try cancelling the trial. Many platforms will offer a discount after cancelling a few times. Prices may actually drop by up to 75%.

AI changes how dental marketing is done today. From functioning as a patient avatar to managing social media, AI provides smarter, data-driven ways to engage with patients. Using these tools can add value to marketing tasks and avoid overburdening the dental team.

Winans X: How AI is changing the game in dental marketing (and how you can use it too). Dent Today 44:8, 10, 2025

Reprints not available

The onboarding process is an essential ingredient in the success of any business, but is especially important for small businesses. Ensuring that onboarding is effective and standardized can optimize the effects of even limited resources and can contribute to a lasting effect on the team. Several strategies can create a positive onboarding process, with some methods helping to prepare for the new hire and others focused on the onboarding process itself.

Onboarding should begin with a welcoming atmosphere for new hires where these individuals feel like they belong from the moment they begin their employment. This requires efforts

before the first day, when they should receive a welcome e-mail, introductions to their future team members, and an outline of what they should expect. The goal is for the first day to be organized and positive so the new employee doesn’t feel overwhelmed.

All of the things a new hire needs should be provided. Their workspace should be orderly, e-mail logins should be set up, and onboarding documents readily available, so that they can feel well cared for. If the new hire is located remotely, video tutorials and helpful resources should be delivered before the first day so the individual can have sufficient information to get up to speed quickly. Small businesses in particular can’t afford to ease into a position. With good preparation, new hires can quickly start contributing.

New hires need to know where they can find answers to their questions. To meet their needs, a system should be in place where they can access information they may need. A centralized digital folder can be created to provide all the key documents that outline everything from office procedures to team contacts. Even virtual employees should be given step-by-step guides and a list of frequently asked questions.

A dynamic, digitized standard operating procedure (SOP) manual should be provided that is easily accessed and continually updated. Having procedures included in the manual will maintain consistency in the work team. The digitized and cloud-based manual allows the new hire to obtain information without constantly interrupting team members with questions or having to rely on verbal instructions or paper copies that may not be as searchable. New hires tend to feel more independent with these resources, and seasoned team members can focus on completing their tasks.

Whatever was promised in interactions before hiring an individual should be honored. The interviewer is setting expectations for what the job will entail, whether that is the salary, benefits, job responsibilities, or flexibility. Promises made during hiring and onboarding should be kept to avoid frustration and a loss of trust and loyalty.

Because everyone learns in different ways, the onboarding approach should be tailored to meet the needs of each new hire. Whether this is a hands-on approach, written instructions, or visual aids, the method should be based on what the new hire shares as his or her preferred training method. It’s wise to ask new hires about their learning style and adapt the process to help them feel more confident and comfortable with the process.

Making a lasting impact on a new hire during onboarding may need to include emotional components. People want to feel

Risk management involves the forecasting and evaluation of risks coupled with the identification of procedures that can minimize or eliminate the impact of these risks. Orthodontic treatment involves some risk. Malpractice claims can be filed by a dissatisfied patient or parent if a problem arises that is related to the care delivered by the practitioner, whereas regulatory complaints

they matter, especially in a small business where everyone is important to the success of the operation. Onboarding is a time to connect with the new hires personally, noting their goals and aspirations and what they need to be successful. Showing genuine interest in who the individual is and not just what he or she does can be highly beneficial for the process. One approach may be to conduct structured reviews after 3 days, 3 weeks, and 3 months from the starting date. These aren’t performance reviews but are opportunities to see how the individual is doing through an open conversation. The new hire should be encouraged to share if added support is needed because his or her growth is an important investment in the future of the business.

To build a strong and successful team, the hiring process should create a welcoming environment, prepare the new hire for success, provide ready access to resources, and foster a culture of trust and growth.

The onboarding process is an essential part of creating long-term success. Not only should onboarding be a time of preparing the new hire to contribute to the vitality of the business, but the new hire should feel valued and connected to the business on a deep level. This will result in engagement, commitment, and loyalty even when resources are limited.

Greenberg J: All on board. Dentaltown 26:54-56, 2025

Reprints not available

are issued by a state dental board or other regulatory body in response to claims the practitioner failed to comply with governing rules. When any of these claims are filed, events are released over which the practitioner has little control, which is why risk management is important. A discussion of the most common causes of malpractice claims, the regulatory complaints seen most often, and how to avoid or mitigate claims was offered.

The most common causes of malpractice claims are undiagnosed or untreated periodontal disease, root resorption, impacted teeth, undiagnosed pathology, and decalcification and caries. Other events can also prompt a malpractice complaint.

The National Institutes of Health reports that 42% of adults over age 30 years have some degree of periodontal disease, with 8% having severe disease. All patients, but especially adults, should undergo screening for periodontal disease before treatment is begun. This screening may be done by the orthodontist or by the patient’s general dentist or periodontist through a referral from the orthodontist. The screening consists of periodontal probing and bitewing and periapical radiographs. Periodontal clearance should be documented in the patient’s chart, with a written communication from the general dentist or periodontist if they did the testing.

Once orthodontic treatment has begun, the orthodontist must continue to monitor the patient’s oral health, particularly if the patient has had periodontal disease in the past. If these measures aren’t taken and disease progresses, the patient can suffer increased bone loss or even tooth loss. The orthodontist will then be held responsible for the undetected disease progression.

Any orthodontic tooth movement can cause shortening or blunting of the roots. The problem is related to many diagnostic and treatment factors, but the orthodontist should diagnose the problem and monitor any root resorption through radiographs. Finding root resorption should prompt changes in the treatment plan to manage the risk of problems once the orthodontic appliances are removed. Patients and parents must be informed of the health of the teeth and supporting structures throughout treatment.

Among the more challenging treatments are those related to bringing impacted teeth into the arch. Often these teeth are engaged with other teeth, so the orthodontist must be aware of the vector of force needed to move the tooth without causing resorption of the roots of adjacent teeth or other problems. The orthodontist must inform the patient and parents about the risks and alternative approaches to recovering impacted teeth before treatment is begun. In addition, the orthodontist should obtain cone-beam computed tomograms of the area to aid diagnosis and treatment planning. In some cases, the teeth don’t move or become ankylosed during movement, with reciprocal movement. In these cases the orthodontist must reevaluate the situation before proceeding further.

Patients and parents should be informed of all these events as they occur.

When the orthodontist doesn’t diagnose pathological conditions, complaints about the care provided can be filed. The orthodontist can take measures to manage the risks, including the following:

• Keep good quality records that include the dental and medical history

• Perform in-person examinations

• Take intraoral and extraoral photographs and radiographs

• Develop pretreatment models

The orthodontist should thoroughly review all of these records, including progress records, and take note of anything that hasn’t been diagnosed. If it remains undiagnosed, a referral to a practitioner who can make the diagnosis is appropriate. However, it’s assumed that orthodontists are able to diagnose any existing pathology in the records or the oral cavity and make appropriate referrals for treatment. They should carefully read x-rays, record their observations in the treatment record, and inform the patient or parent.

Removable clear aligner therapy carries the risk of holding plaque or sugary fluids against the teeth for prolonged periods. As a result, patients who don’t follow appliance care and oral hygiene instructions are susceptible to decalcification and caries development. Patients must be properly educated and the orthodontist must conduct ongoing communication with parents and patients and the general dentist during treatment. Problems should be promptly addressed to prevent any claims against the orthodontist.

Among the other problems for which malpractice claims have been made are excessive enamel removal during debonding, etchant burns, accidental swallowing of appliances, and eye injuries. Many other situations can also prompt claims, but most can be minimized by establishing good quality systems and having properly trained assistants. If accidents happen, the orthodontist must be prepared to manage the situation and ensure emergency care is provided as needed.

Regulatory complaints are often filed by unhappy patients or disgruntled employees. Among the situations in the claims are the delegation of duties beyond the state dental practice act restrictions, improper sterilization, misleading advertising, or other situations in breach of the regulations. When the state

board investigates the complaint, they can examine any aspect of the orthodontist’s practice covered by the dental practice act, regardless of the complaint’s focus. It’s vital that the orthodontist is aware of what’s in the dental practice act and is following the rules.

Orthodontists can avoid or mitigate complaints by communicating clearly and properly with patients and parents, but also by understanding where claims are most commonly raised. Their diagnostic and treatment plans should be well-documented. A pretreatment conference with the patient and parent is required where the orthodontist identifies the recommended treatment, carefully explains the plan, and obtains informed consent. The American Association of Orthodontists and American Association of Orthodontist Insurance Company websites offer excellent informed consent documents. Many cases also should include additional, more detailed informed consent, and the orthodontist should be diligent in obtaining the needed consent.

Orthodontic treatment involves a degree of risk. Orthodontists should use the informed consent documents to initiate discussions of the risks of any proposed treatment so that patients and parents are properly aware of what they are agreeing to have. This discussion or discussions should be properly recorded in the patient’s record to provide evidence of the orthodontist’s careful adherence to risk management procedures.

Roberts CA, Varner RE: What is risk management (and why should I care?) Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 167:379-381, 2025

Reprints available from CA Roberts, 338 Pheasant Run Ln, Findlay, OH 45840-7082; e-mail: crobaanoic@outlook.com

At the Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global treaty was proposed to protect the environment and human health by limiting the use of mercury. In the European Union (EU), the use of amalgam, which contains mercury, has been phased down and will soon be phased out, but the United Kingdom (UK) completed phase-down efforts in 2017 and is focused on completing the phase-down by 2030. In the UK, practices under the National Health Service (NHS) tend to restore posterior teeth using amalgam more often than any alternatives. Composite resin is the only reasonable alternative to amalgam within the time frame for the phase-down and phase-out efforts. Glass-ionomer cements (GICs) and derivatives may offer an alternative for small cavities, but no single material can replace amalgam in all applications. Health systems with limited resources favor amalgam because of the higher costs of alternatives. In addition, the properties and clinical performance of alternatives tend to be less desirable than those of amalgam. Amalgam and alternatives were compared based on their respective clinical outcomes, needed skills and safety, economic costs and comparisons, and the perspectives of patients, clinicians, and other interested parties.

Caries associated with restorations (CARS) is the primary way direct posterior restorations fail, followed by fracture, and pulpal or endodontic complications. The risk of CARS is lower with amalgam than composites, but the evidence remains imprecise, with failure mode differences over time. The differences in clinical outcomes tend to be primarily related to the technical difficulty in performing complete restorations rather than being caused by the use of amalgam.

CARS detection methods are associated with significant diagnostic difficulty, especially when composite restorations are considered. CARS can be seen more often at the gingival margin of restorations, making repeat restoration difficult, especially with composite. A defective restoration may allow an accumulation of biofilm, usually as a result of gaps between the restoration and the cavity wall. Peripheral gaps occur more often with composites because their process is more technically challenging and can predispose to postoperative sensitivity. Cariogenic biofilm accumulation is more likely to occur with composite than with amalgam.

About three fourths of tooth fractures occur in teeth that have 3 or more surfaces restored. Vital teeth are more likely to suffer favorable supragingival fractures than non-vital teeth. Fracture risk is diminished when indirect cuspal coverage restorations are placed in posterior root canal−treated (RCT) teeth and in vital teeth with biomechanical compromise. These restorations are more costly and require more time to place than direct restorations, making it less likely that they will be performed. As a result, tooth survival is reduced.

Amalgam preparations usually are box-like, closed, and upright and include sound tooth structure that provides mechanical undercuts. Composite preparations generally have more flare and are open with a saucer-shaped style, but they lack the mechanical retention form. The composite approach is considered more minimally invasive, but the box-shaped preparations have been reported to offer superior survival compared to the saucershaped ones. However, laboratory studies fail to consistently support this finding and tend to indicate that amalgam restorations have a higher incidence of failure. Often the difference is skewed because the number of amalgam restored teeth tends to significantly exceed the number of composite restored teeth. In many analyses, the difference in failure rates between the materials remains unproven.

Amalgam is compacted with firm pressure into the cavity and expands very little, which results in more precise marginal adaptation and few if any gaps. Composite materials shrink on setting and have a softer consistency that keeps them from adapting during placement. In addition, composite is placed in multiple increments to manage the depth of cure and reduce contraction stress, which increases the chance of gap formation. Specialized equipment is needed to form contact points with composite, also contributing to material fracture, food packing, and CARS.

Bonding agents are applied to the tooth to prevent composite from pulling away from the cavity walls during polymerization. However, the bond can be compromised by numerous factors. Cavities whose margins are located subgingivally are especially challenging. Complications include incomplete light curing of

composite, washout of uncured components, and gaps after degradation of the composite bond over time. Amalgam restorations don’t require these measures and have fewer sensitivities to technique.

Posterior composite restorations require significantly more time to place than amalgam restorations. Many UK primary care dentists feel there are too many choices to consider when composites are indicated and that the recommended equipment is relatively expensive. As a result, private practice practitioners tend to be the only ones who follow the NHS recommendations (Appendix 1). Some health systems charge a fee for placement of a rubber dam (RD). When more tooth structure is lost and the margins extend more deeply into subgingival areas, placing a well-adapted matrix-wedge assembly to directly restore a tooth becomes considerably more challenging. Amalgam is often preferred for these situations because marginal seal adaptation isn’t as critical as it is with composites.

Most primary care dental practitioners in the UK are confident placing posterior composites in standard situations, but about two thirds of 1500 practitioners who were surveyed had no or low confidence placing composite in patients with limited cooperation. Only 7% of this group felt uncomfortable with amalgam placement. Restorations of subgingival cavities with composite sparked low or no confidence in over half of practitioners, but only 4% of practitioners were troubled when amalgam was used. This may indicate a failure in the education of dental professionals regarding the use of composites for such situations.

Most new UK graduates have predominately used composite during their undergraduate experiences, but when they are trained under NHS provisions, they place more amalgam. Predictors of low rates of postoperative issues are being trained with composites for total posterior restorations and not using liners, but using sectional matrices. These practitioners are confident when placing subgingival composites, tend to use an RD, and are usually private practice dentists. The NHS incentivizes using amalgam, usually based on the relatively large discrepancies between the remuneration for composites and that for amalgam.

When a restoration fails, the provider must consider the longterm impact of the restoration on that tooth. Removing composite restorations is consistently more time-consuming, involves the removal of more sound tooth structure, and leaves more of the existing restoration when compared to the removal of amalgam restorations. Repair is arguably less destructive of tooth tissue than replacement and can slow the restorative cycle. How often repair is done by primary care UK dentists rather than removal and replacement is uncertain, with limited evidence available.

The evidence shows no clinically significant differences in the safety of amalgam versus that of composite for patients as well as for dental personnel. A localized lichenoid reaction in the mucosa adjacent to amalgam restorations occurs in rare cases. Reports of resin allergy among patients and dental personnel remain to be investigated. Health concerns regarding the monomers used in composite and the inhalation and ingestion of microplastics haven’t yet been studied.

Nearly all health care systems show that posterior composite restorations require more time and cost more than amalgam. This tends to disincentivize their use. Remuneration of NHS dental care is considerably lower in the UK than in the rest of Europe. Fees paid to dentists for treatment should be increased to help retain dentists in NHS practices, with the loss of dentists posing a significant problem.

Economic evaluations (EEs) can be based on data gathered from a clinical trial over the course of that trial or extrapolated over a lifetime using modelling techniques. All EEs and health technology assessments (HTAs) comparing amalgam with composite posterior restorations show amalgam is more effective in terms of restoration and tooth survival and less costly. Models simplify the restorative cycle and use data sources to inform how restorations fail, both of which aren’t relevant to the UK primary care perspective. Up-to-date information on restorations placed under NHS provisions in England and Wales remains limited.

Previous EEs focus on the survival of restorations and teeth, which are clearly important to stakeholders. However, composite and amalgam restorations vary in ways that are important to patients, clinicians, and others, such as those who pay the bills.

Cost remains the most important factor when patients choose a restoration. Composites offer patients clear aesthetic benefits, with patients willing to pay to have a white compared to a silvery-gray restoration. They are also willing to pay twice as much to have no postoperative pain, about the same amount for the restoration to survive 14 years instead of 5 years, and the same for the wait to be reduced from 6 weeks to 2 weeks. Most favor the use of amalgam for cost’s sake, but the other factors noted must be taken into account if patient satisfaction and uptake of services are valued—which they are. Patients can benefit if interventions are done before more advanced disease develops, avoiding pain, morbidity, and higher costs for treatment. Cost can be direct and out-of-pocket for the patient and insurer, but it can also be indirect and involve the loss of

work, a resulting effect on the employer, and an impact on the general productivity of society. Traditional EEs only consider costs from a single perspective. Indirect costs are seldom accounted for in evaluating restorations.

Patient access issues are at risk if evaluations don’t consider or value clinician perspectives. When practitioners aren’t valued, they may leave health services or their time demands may result in long waits for care. Dentists are leaving the NHS in record numbers because of remuneration issues as well as a loss of trust in the NHS after the new contract. Composites take longer to place, longer to replace, and will likely need more frequent replacement than amalgam. In addition, the cost of composites is higher than that for amalgam, although the EU ban may change that. The majority of UK primary care providers believe that an amalgam phase-out will impact their ability to do their job, create delays in care, and lead to a need for more indirect restorations and extractions. This would tend to exacerbate the current access issues.

Some Canadian HTAs find that the environmental impact of mercury released from amalgam is small. Although amalgam separation, disposal, and crematorium costs have been considered, the actual impact from composites remains unknown. Other potential environmental issues and costs associated with composite restorations must be further investigated.

Another perspective is related to which patients will be most affected by the phase-down and phase-out of amalgam. Generally, those most in need will be preferentially affected, and this includes those of low socioeconomic status, those with disabilities, and older patients, who often have comorbidities. Amalgam performs better in patient groups at high risk for caries.

The appearance of restorations tends to be less valued among lowincome groups than in higher-income groups. Phasing out amalgam risks access issues because of the increased clinician time needed to place composites and perform replacements, the loss of workforce numbers from public to private practice, and an increased cost shouldered by the patient. Treatment uptake would be reduced, leading to more significant dental disease, greater morbidity, loss of productivity, and wider health inequalities.

The current phase-down of amalgam use is being accomplished by using amalgam only if it’s deemed strictly necessary by the dental practitioner based on the patient’s medical needs. Primary care clinicians believe that placing an amalgam restoration in children or pregnant patients carries a risk for them, one they don’t care to bear. The consent process is compromised, as is the justification for use and the support provided by an indemnifier if a complaint arises. The shared decision-making process is

compromised as well. High-caries-risk children, whose cooperation can be limited, will be affected.

The ultimate goal of a minimal intervention philosophy is a cavityfree future where restorations are unnecessary. This would eliminate the need for any phase-out or phase-down for restorative materials. Composite may be selected for its ability to adhere to tooth structure and allow more minimal tooth preparation, provide a tooth-colored option, and result in high levels of patient satisfaction. This future isn’t reality and doesn’t face the fact that most of the health care systems’ constraints tend to favor the use of amalgam. Alternatives need to be developed that will have minimal environmental impact. The techniques used to restore various cavity presentations with composite require training so practitioners can use them in difficult situations. Organizations such as the NHS need to clearly define their goals and design a service that incentivizes the achievement of the goals with minimal unintended consequences.

Amalgam offers a simpler, quicker, and more costeffective option to place and replace restorations compared to composites. Fewer postoperative complications are also associated with amalgam. Composites can be effective for extensive cavities but require practitioners to develop more extensive skill levels and involve the use of expensive, timeconsuming specialized equipment that is seldom available in NHS dentist offices. With its low remuneration and the disincentivization of recommended expensive and time-consuming equipment for composite, the NHS is probably contributing to dentists failing to develop the greater skill levels composites require and is instead incentivizing the use of amalgam. In addition, patients have limited access to care, with those at greatest need disproportionately affected. An oral health crisis in the UK may be on the agenda if amalgam is phased out in the near future.

Bailey O: The long-term oral health consequences of an amalgam phase-out. Br Dent J 238:621-629, 2025

Reprints available from O Bailey, School of Dental Sciences, Newcastle Univ, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; e-mail: Oliver.bailey1@ncl.ac.uk

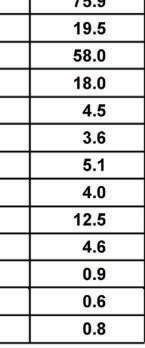

Key: *, ≥ 76% use rubber dam, no liner, wedge; ≥ 51% use sectional metal matrices. **, P<0. 0001 (Chi2). NHS, National Health Service. CDS, Community Dental Services. (Reproduced with permission from Bailey O: The long-term oral health consequences of an amalgam phase-out. Br Dent J 238:621-629, 2025.)