the battle for britain

Che Wheeler

Gaza: The Deathly Cost of Indecision

Biology, belief, and the ballot: a review of ‘what’s your bias’?

Che Wheeler

Gaza: The Deathly Cost of Indecision

Biology, belief, and the ballot: a review of ‘what’s your bias’?

Welcome to the 50th edition of Perspectives magazine! We’re thrilled to introduce our freshers edition, full of fresh ideas, impassioned students, and thoughtful opinions. Perspectives is your space to speak up and debate, and this edition demonstrates that beautifully. Our feature piece dives into the dynamic between the left and the right wings in Britain, a potential future under Reform UK, and what’s really needed to revolutionise British politics. Our writers offer their solutions to pressing global issues, addressing fascinating topics with a passion and insight characteristic of student journalism here at Warwick and within Perspectives. As ever, none of what lies ahead could’ve been achieved without our amazingly dedicated editorial team and community of writers. Our deputy editors — Evan, Alice, and Dan — crafted the pitches for this edition’s articles and found time in their summers to help make this edition the best it could be. Our fantastic design editors, Zita and Rio, continue to produce stunning layouts with our incredibly talented cartoonists, Lily and Ben, who always work wonders with their illustrations. And, of course, coEIC Will, whose enthusiasm for Perspectives makes every challenge seem less daunting. Each member’s creativity and work ethic was invaluable to making the magazine we have now. When I first arrived at Warwick, this magazine encouraged me to get involved with Politics Society and Perspectives, both of which became central to my university experience. I hope our first edition as Editors-in-Chief sparks the same excitement in you. Enjoy!

including our writers WhatsApp group and website.

We proudly launch the 50th edition of our print-magazine to kickstart what, I am sure, will be another fantastic year of student journalism at Perspectives. For students at Warwick, Perspectives is the home of student political commentary but, to Khushi, myself and many others, it is also much more than that. It represents a vibrant community of young people writing about topics that interest and matter. For me, that is what makes our paper so exciting. We are able to give students a voice, publish their work and see that it gets the recognition which it deserves. Ultimately, Perspectives is just the platform, and we are nothing without our community of passionate and committed writers. We sincerely hope that you, like us, can find that same freedom and excitement with Perspectives during your time at Warwick. We would like to thank all of the team who make this possible. When it comes to the print editions, Khushi and I would be lost without the superb efforts of our designers, Zita and Rio, as well as our ever hard-working cartoonists, Lily and Ben. I would also like to thank our deputy-editors, Evan, Alice and Dan, who helped throughout the year and who also crafted the pitches for this edition. Finally, I would also like to thank Khushi, my co-Editorin-Chief, without whom none of this would have been possible. We hope you enjoy this edition, and we thoroughly look forward to meeting all of our new writers in the coming weeks, and welcoming back many familiar faces too.

Write for us! send articles and ideas to perspectiveseditors@gmail.com AND join our WhatsApp group for first choice of print and online pitches.

Best specialist publication in the midlands

The recent introduction of the UK’s Online Safety Act has been subject to varying response. The bill, which was originally passed in October 2023, requires the compliance of social media companies with several key duties to protect users. It has involved watchdog Ofcom developing guidance for online platforms, and includes restrictions on illegal content, categorised services and content which may be harmful to children. Most notably, several social media platforms have enforced age verification for sensitive content since the Act’s implementation in July.

The importance of protecting those utilising the internet from potential harm has been recognised by many, particularly for children who could access inappropriate content. YouGov’s polling, asking Britons whether they support “requiring age verification to access pornography sites” elicited strong support, with eighty per cent of respondents agreeing with these measures. Similarly worded polling from More In Common also drew strong support for such online safety measures. The result of this polling is hardly surprising; the necessity of safeguarding young people from threat, digital or otherwise, is a commonly held sentiment.

However, the potential implications of age verification checks have also been advanced. These age checks require sharing identification documents or inputting credit card information, which many share reservations about. Eighty seven percent of those polled by More In Common shared concerns about personal information being compromised during age verification, as well as seventy four percent being worried about young people’s ability to bypass these checks using VPNs. The Act has also attracted considerable opposition online within its first month, with individuals citing ramifications for free speech, as well as personal information being leaked. This all raises a vital consideration; could tools designed to curb one kind of harm be used to facilitate another? In addition, are age verification methods even effective in what they set out to do?

These questions sit at the heart of the debate over the Online Safety Act and should be an imperative source of discussion for any future developments, both in the UK and abroad. As the new restrictions are in their infancy, it is impossible to gather a full picture of their efficacy. Indeed, other countries have also introduced legislation to minimise online risk, such as New Zealand’s Harmful Digital Communications Act and the EU’s Terrorist Online Content Regulation.

Specific age restriction mandates for pornographic websites have previously been implemented in France, as well as some US states. However, this marks the first occasion where platforms have agreed to comply with this government decree, as opposed to blocking access entirely as seen in the US and France. Whether the polled public opinion concerning the Act in its proposal stages will stay consistent remains to be seen.

Party politics also has the potential to skew public opinion towards the Online Safety Act. Nigel Farage’s vocal dissent at this policy, and pledge for Reform to scrap it if they come into power, is notable. This objection may incentivise his supporters to oppose it, as well as influencing Reform’s detractors inversely. In addition, despite the Act being passed under the Conservative government in 2023, its introduction under Labour leadership could affect its reception across the political spectrum. This complicates the minefield of public opinion, blurring the lines between genuine criticism regarding issues of privacy and effectiveness, and resolute party preference.

Despite this, the consequences of government access being granted to our sensitive data is a concern shared across party lines. The law has already been dubbed by Reform as ‘dystopian’, with many echoing the sentiment that it is a Draconian infringement on both privacy and autonomy. The consequences of data leaks, particularly for vulnerable groups like the LGBTQ+ community on dating platforms, could be devastating. Furthermore, as the law restricts illegal content, this could jeopardise freedom of speech. For example, the recent proscription of activist group Palestine Action could engender the censorship of any content deemed to be pro-Palestinian, under the Online Safety Act’s curtailments. Asserting that governmental authority trumps public freedom and security sets a dangerous precedent for future regulations.

As the Online Safety Act becomes an established feature of the UK’s digital sphere, its enduring implications will be revealed. Only time will tell whether the legislation does indeed succeed in minimising online harm, or whether it has unintended consequences for privacy and data protection. Nevertheless, discourse surrounding protective means to filter online content, as well as information security being preserved, will no doubt persist. It is imperative that the most efficient and secure method of digital safeguarding is established, with the least possible compromise involved. Regardless of whether the Online Safety Act is the country’s solution to digital danger, would public reception truly reflect this? I am inclined to disagree.

As a professional denizen of the internet’s murkier corners, I’m usually immune to digital absurdity. But a Pop-Base update on 20th June, 2025, had even me questioning my immunity. I am, of course, referring to The Government of Pakistan’s official nomination of the US President, Donald Trump, for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Trump has long curated the image of the ultimate deal-maker, the maestro of conflict resolution, who can end wars with charm and sheer theatrical force. He claims to have been the driving force behind the resolution of six major conflicts. Trump’s method of peacemaking is a simple two-act play: first, declare the situation a “total disaster.” Second, execute a swift exit or a dramatic gesture that creates the illusion of resolution. The substance is irrelevant; the headline—the spectacle of it all— is everything.

To verify all of Trump’s claims would be an arduous process, and warrants a whole book’s worth of discourse on its own. For the sake of brevity, I’ve chosen three key claims to examine Trump’s diplomatic prowess.

Act-1; Afghanistan: This was his magnum opus. The “peace deal” was struck not with the US-backed Afghan government, but with the Taliban. The result was the abandonment of a state and its people. The government collapsed, the Taliban marched into Kabul, and two decades of progress on human rights evaporated overnight.

Act-2; The Abraham Accords (Israel-UAE/Bahrain): This is the one claim with substantive weight—the intention behind which, was more about realigning Arab powers against a common Iranian threat, than solving a crisis. It sidestepped the Palestinian aspiration for statehood entirely, while the brutal Israeli occupation on their lands continued. It may have brought consensus between governments, but not peace on the ground.

Act-3; India-Pakistan: Trump’s crowning jewel in conflict resolution, was his repeated offer to mediate on Kashmir—the diplomatic third rail that has plagued relations between India and Pakistan since their independence in 1947. Trump’s role was less that of a mediator and more of a bull who briefly wandered into the china shop of Indo-Pak relations, admired the ceramics, and wandered out again, destroying a couple precious items here and there. The conflict remains frozen, perilous, and utterly unresolved.

To credit these claims to Trump alone, however, would be doing a disservice to the very many hardworking individuals behind the curtain, whispering small words of affirmations to the

benevolent Trump. So, who are the stage managers for this grand performance?

There is, of course, J.D. Vance, who provides a highbrow, intellectual gloss to a fundamentally isolationist impulse. His best-selling memoir’s worldview now conveniently doubles as a foreign policy doctrine. Then you have Richard Grenell. As former Acting Director of National Intelligence and a favoured troubleshooter, his role is to be deployed, cause maximum disruption and confusion, and claim victory in the ensuing haze. This ensemble is less a cabinet and more a production crew for a “Trump’s Greatest Deals YouTube compilation”, scouting locations for the next spectacle and ensuring the lighting is just right. Their job is to affirm that the emperor’s new peace accords are real and are also the most beautiful agreements anyone has ever seen.

For this administration, a sustainable peace agreement, brokered through diplomatic dialogue and consensus, is boring. It lacks theatre and, crucially, it lacks a dramatic third act that a soapopera would provide. The true cost of this performance is measured in the human beings who become unpaid extras in this geopolitical drama.

It’s the Afghan girl who can no longer go to school. The Syrian youth living in destitution. The Palestinian families that don’t exist anymore. The Kashmiri teenager living under a militarized curfew. The Iranian people choked by sanctions. It’s entire populations that become mere set dressing for a show that’s already moved on to the next season, their lives and stability a trivial casualty of the plot.

So, is Trump’s image as the world’s premier conflict resolver justified? If resolving a headache by decapitation counts, then sure. But if resolution requires a future that doesn’t immediately collapse into a worse version of the past, then we have bigger concerns to address. We’ve learned to brace for scandal and crisis, but perhaps the most chilling headline isn’t the one that shocks us, but the one that numbs us. The real danger isn’t that a Nobel Prize becomes a trophy for performance art; it’s that we, the audience, become so accustomed to the spectacle we forget to ask what happens after the curtain falls. We stop wondering about the silence that follows the tweet. And in that silence, the real world burns.

Meghana Pappu; 2nd Year, Politics and International Studies, Manama, Bahrain

On the surface, the results from the first round of Bolivia’s election may suggest that a sense of stability is landing in Bolivia after years of political upheaval. With the right attracting close to 60% of voters, the assumption that Bolivia is becoming unified against the last twenty years of left-wing rule might be made. However, beneath this current shift, division and disunity remain rife across the nation. To many Bolivians, improvement still seems something that is out of reach.

With supporters of right-wing Rodrigo Paz (a former interim president) and Jorge ‘Tuto’ Quiroga celebrating the fall of ‘socialist dominance’ as they both head into an unprecedented runoff in October, the question is whether Bolivia’s next leader will address the resounding political polarisation and challenges facing the nation in the years to come—vital if Bolivia is to regain its economic and political prominence in South America.

The polarisation of politics, the economy and ideologies across Bolivia has undoubtedly played a central role in limiting its success. For years, it has eroded public trust in institutions, divided communities on matters of ethnicity, regionality and ideologies, as well as triggered a number of governmental and economic problems. Since the removal of Evo Morales in 2019 following widespread allegations of election fraud, Bolivian politics has been deeply impacted by the divisions exposed by his ousting. Combined with the years of economic growth and poverty reduction led by Evo Morales and the Movement for Socialism (MAS), the period since 2019 has caused many Bolivians to view institutions (such as the judiciary and military) as tools of partisan interests, rather than ones of a functioning democracy.

The ongoing election vividly reflects this polarisation across Bolivia’s political landscape. Shockingly, but expected by many, the Movement for Socialism which has governed Bolivia for twenty years, received just 3.2% of the vote, narrowly passing the threshold for party survival. This sharp decline not only reflects a collapse in left-wing support, but also highlights the impact of fragmentation within the party itself, with figures like Andrónico Rodríguez previously breaking away. Simultaneously, the substantial number of null and blank votes (summing to around 20% of all ballots), further signals widespread disillusionment among voters. With many suggesting that this was a protest vote in support for the MAS, Bolivian politics in the present is still seen to be made unstable by its recent past.

George Marshall; 2nd Year, History, Northampton

This polarisation, which has been left to expand for many years as a result of little meaningful reconciliation following Morales’s ousting, has left all sides of the political spectrum entrenched in their own narratives of justice and victimhood, delaying any form of progress. For many, it is this fractured landscape which has brought two right-wing candidates and caused no candidate in the first-round vote to win a majority. With this polarisation clear to be persisting, even as Bolivia chooses its new chapter, the rebuilding of trust in institutions and addressing voter alienation and resistance—symbolised by null votes coming third—are urgent tasks for Bolivia’s next leader.

While polarisation will be a central issue to whoever wins this election, economic instability and governing without the MAS and how these are tackled will define this new era of Bolivian politics. The next president will face immediate economic challenges: declining natural gas exports (Bolivia’s primary source of revenue), growing fiscal debt, and foreign reserves dropping to below £1.5 billion. The polarising impact of inflation nearing 25% and rising public debt across the country will also be of major concern, limiting the space for social spending and infrastructure investment. With Bolivia’s economy weakened by interim governments since 2019, particularly by the COVID-19 mismanagement and public spending cuts of Jeanine Áñez, whoever wins will have the challenging task of beginning to reduce economic inequality across the nation.

Furthermore, with the MAS experiencing a dramatic decline in the first round of this election, Bolivia and its new leader will face a challenge not seen for over two decades: governing with a party which does not have widespread and grassroot support like the MAS did. This shift undoubtedly demands building greater cross-party relationships, regaining public trust among minorities and generating policies which are inclusive and beneficial to many across Bolivia under the strain of economic and institutional collapse.

As Bolivia heads to the polls and turns the page on left-wing rule, its next leader must confront the deep-rooted political division, economic fragility, and above all, its fractured electorate. Though large focus has been given to the ideological change pending regarding politics, its new leader’s success, be that Quiroga or Paz, will depend on inclusive governance and their ability to unify a nation still impacted by turbulent recent years.

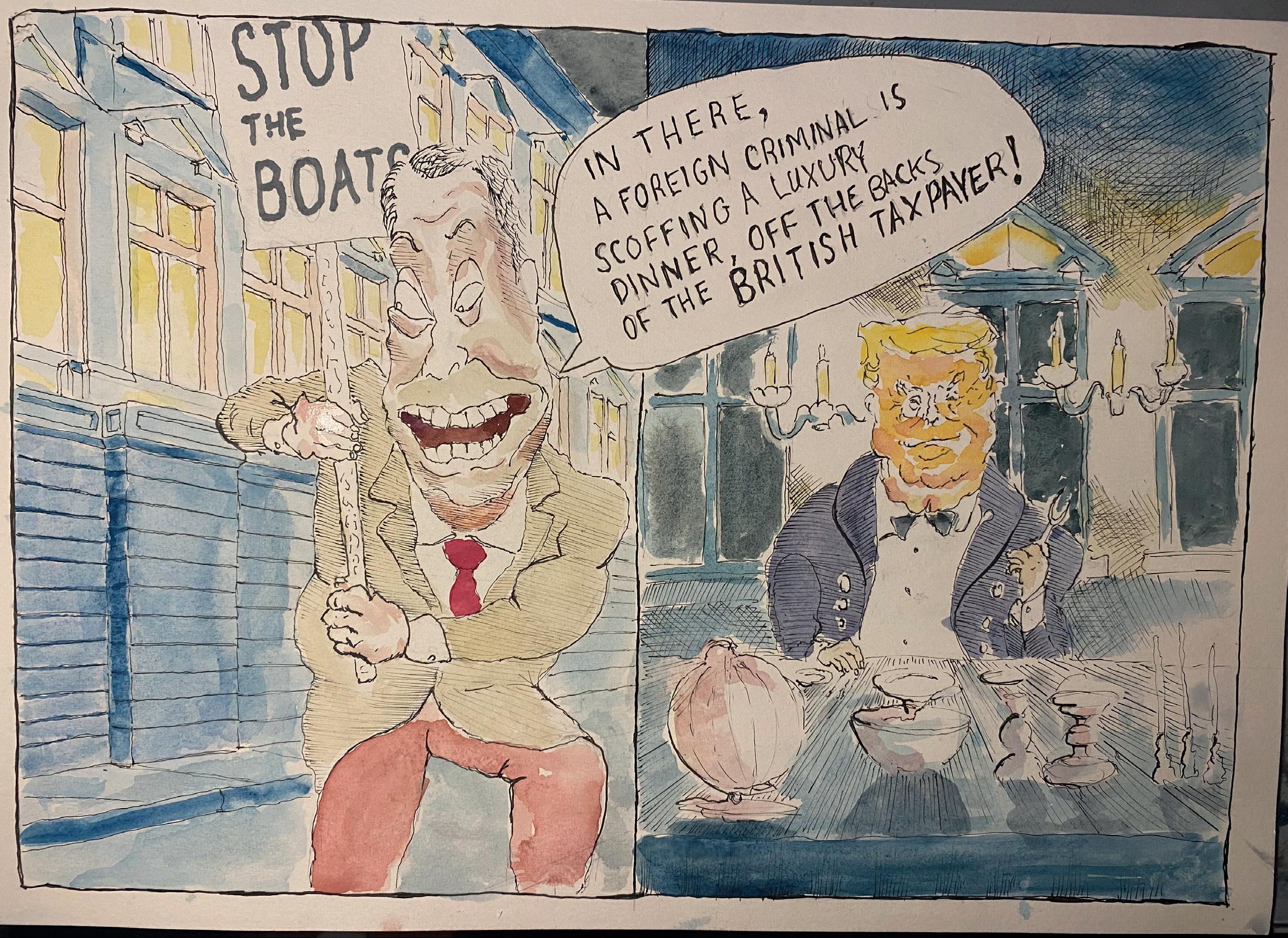

The past century of British politics has, until recently, seen a damning duopoly between the Tories and Labour. While it certainly wasn’t a balance which remained static, no one ever really doubted either party’s legitimacy. It was a paradigm in Britain, that one would always win a general election. In a telling testament to the shaky and aging pillars of British institutionalism, it appears that this precedent is finally being usurped.

Labelled as a “wannabe Trump” by his opponents, and as the saviour of British politics by his followers, former Brexiteer turned Prime Ministerial hopeful, Nigel Farage, has shaken Britain, with a wave neither red nor blue, but instead a distinct turquoise. In the span of just a year, Farage’s Reform UK has catapulted itself to be the most popular among the British public, polling at around 30% of the popular vote and projected to form a majority government at the next general election. On the surface, his movement might seem revolutionary. Farage has managed to portray himself as a strong suit against his peers, perceived as willing to speak out, and to do things other politicians aren’t willing to. Yet,when one breaks down Farage, and the tapestry of both his party and supporters, a Reform government may not be the champions of justice many hope them to be.

Firstly, Reform’s economic policies are balancing on thin ice. Their “contract for you” attempts to break down their ambitious five-year national spending plan into a cost-efficient exercise. They have vowed to pour more cash into vital services, such

as an additional £17 billion for the NHS, while simultaneously seeking to cut back on “wasteful government spending” of up to £50 billion. Anyone who has kept up with US politics in recent times, should sound alarm bells at the rhetoric, which Farage is taking inspiration from.

Trump’s butchering of the US federal government has exposed nothing of the so-called “deep state”, instead, it has stripped at least 200,000 talented personnel, vital in providing the government expertise in relevant fields. The consequences of this have ranged from stopping vital medical research, to the weakened containment of a bird flu epidemic.

If it is the case, that this is the model Farage seeks, any benefit from monetary injection into public services will be short-lived at best. While it is often portrayed in popular discourse that funding alone will prop up public services, civil servants are vital in thoroughly reviewing and implementing policy. Little, if any of that process, is “wasteful”. Furthermore, the government is already suffering from funding restraints, a prominent example being the failure of the Office of National Statistics to produce reliable data, which has had major consequences on the recent implementation of government policy, such as taxation. Further budgetary reduction would only make this worse. Even Reform’s own supporters are aware of these risks: a Survation poll conducted for Channel 4 found that only a fifth believe that Reform’s fiscal policies will come without higher taxes or further spending cuts.

So, what else has kept Reform sailing? There is the seemingly more convincing argument of immigration. Much of the frustration is directed against the issue of illegal immigration via “small boats” across the Channel, and the ongoing tension surrounding asylum seekers being housed in British hotels. Such concerns have boiled over this summer into full-scale protests, after an Ethiopian asylum seeker housed in Epping was found guilty of two counts of sexual assault. Here, Reform has taken a much firmer stance compared to its contemporaries. While the government has said it will only gradually move asylum seekers out of these hotels, Reform have made bold pledges to nip all arrivals in the bud. Farage’s promises here include the immediate detention of all asylum seekers who arrive illegally, and a “freeze” on the arrival of “small boats”. In addition to these pledges, Farage has recently announced plans to deport up to 600,000 migrants in the UK. Regardless, such plans do not come without their flaws: though they are projected to eliminate the costs associated with housing these migrants, the cost for the deportations will cost at least £10 billion. A similar plan by Reform defector Rupert Lowe, valued at almost £50 billion, alludes to even higher costs once the plan is implemented. Controversially, such a plan would also involve paying host countries to take migrants back, among that list, regimes well-known for moral ambiguity and human rights abuses, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Eritrea.

Looking once more across the Atlantic, Trump’s own immigration plans have seen ICE deport 200,000 people in the first seven months of his Presidency. But even on his bread and butter, Trump holds limits. In a press conference in June, Trump recognised that Mexican labourers for American farmers, even if they were illegal migrants, were vital for the latter, and as such, he would pursue caution around them. Farage is likely to take a similar approach, maximising his rhetoric now, to appear bold and decisive, but scaling back on his plans later. In politics, the most important skill to have is the illusion of progress, so Farage will likely highlight what immediately happens through media fanfare, rather than sticking regimentally to overarching targets.

Ultimately, beyond the barrage of rhetoric, the current confrontation between Reform, and the Labour government, must be seen for what it really is: an inter-capitalist civil war. In all their political games, both Farage and Starmer hold one thing in common; a rigid refusal to touch the other alternative to the crisis of austerity, tackling the super-rich. Instead, both have taken it upon themselves to deceive most of Britain’s population into sacrificing ordinary people first.

When looking at the protests which have rocked Britain, while many are committed to the hateful ideologies of the far-right, others are simply frustrated with our stagnant politics and the cost-of-living crisis. Unfortunately, it is the latter who are deceived, and who stand to lose the most.

Outlets like GB News and the Daily Mail, promote toxic discourse against immigration, and seek to inflame the costs of it as much as they can. And it’s not just migrants who are used as shields. As seen through the government’s attempted welfare reforms, and Farage’s own comments on the oversaturation of special educational needs, both Reform and Labour are seeking to pin the blame for financial drain on the most vulnerable sections of

society, hoping that silencing a few will keep the many complicit. Reform UK, for all its attempts to be a new brand of British politics, has its funds oozing from both former Tory donors, and those concentrated in tax havens. On the other end of the spectrum, Labour, a far-cry from its days as solely a collective of trade unions, now receives many high-profile donations from those who see confidence in its centrist and selectively pragmatic platform, including those who have originally donated to other parties. This is while its support from unions has continued to dwindle, highlighting the rationale of Starmer’s decision to chase Reform’s talking points, rather than listen to Labour’s traditional base of support. The Trade Unions Congress, which contains many Labour-aligned unions,has recently urged Starmer to finally consider a tax on the super-rich in the November Budget.

The end result? A phenomenon which has played out all too well since 2010: successive efforts to cannibalise Britain’s population, offering minimal savings and minimal benefits. If Farage does come into power, do not be surprised if the steam from his rhetoric runs out, and the UK is dead-set for another five years of austere policies.

So how should we truly revolutionise British politics? Turning our heads towards those who sought to put us in this predicament in the first place is another critical, yet overlooked answer. While such a solution is not perfect, it is a more viable route to increase government funding to essential services, without risking the quality of those services in the process. It is also a method which means all of Britain’s population is accounted for. A study at King’s College London, albeit from three decades ago, found that even a 2% tax on assets over £10 million in the UK, could raise up to £160 billion in finances. Such policies have already proven effective in Spain, where €3 billion is expected to be raised from their own taxes on wealth.

Until this is considered, Reform will continue to charge through their fragile agenda nearly unopposed. Regardless of Labour’s shift to harsher immigration policies, Starmer simply lacks the same energy and persona as Farage, which is why such moves have not borne fruit for Labour. As happened to Starmer, there is no doubt that the British public will eventually see through the twisted puppet show of Reform, and yet again demand something new.

Charles Wawn; 2nd Year, Law, London

Pedro Sánchez came to power in Spain in 2018 after winning a motion of no confidence that he tabled against his predecessor, Mariano Rajoy, whose party had become embroiled in a corruption scandal that led to the jailing of its former party treasurer. In his speech, he spoke of political corruption that “erodes society’s trust in its leaders and consequently weakens the authority of the state...it strikes at the very root of social cohesion”.

In the seven years since then, his grip on power has been severely weakened, hemmed in by corruption allegations against close party colleagues. One of those ex-colleagues, Santos Cerdán, the former ‘Organisational Secretary’ of Sánchez’s Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), has been held in pre-trial detention since June this year after he was denied bail. The former number three in the PSOE is on trial for allegedly receiving bribes to secure government contracts, in connection with the ‘Ábalos case’. Additionally, Cerdán and his former aide were allegedly recorded graphically discussing sharing prostitutes. This tarnishes the reputation of a Prime Minister who touts his feminism through his support for outlawing prostitution to combat human trafficking. The recording also reignites allegations that Sánchez’s father-inlaw used to operate brothels.

To British readers, the chain of scandals is reminiscent of the later years of the 2010-24 Conservative government. Cerdán has been caught up in the ‘Koldo’ case, which involves Koldo García, who was the aide to former Transport Minister José Ábalos. García and his wife were arrested in February last year and are being investigated for corruption. They, along with Ábalos, have maintained their innocence. The attorney-general and Ábalos are also being investigated for allegedly leaking court documents about the partner of an opposition politician.

Sánchez’s family is also under scrutiny. His brother, David, has been placed under investigation for suspected embezzlement, influence peddling, misuse of public funds, and social security fraud during his tenure as a music director in a provincial government. David Sánchez resigned from his role in February this year when the investigating judge suggested that the post may have been created specifically for him. Meanwhile, the Prime Minister’s wife, Begoña Gómez, and her aide in the Prime Minister’s office were charged with embezzling public funds in August. Gómez is alleged to have misappropriated software financed by her employer, Complutense University in Madrid and by having issued contracts for the University without authorisation. She will stand trial on 11 September.

Sánchez has dubbed the investigations into his family members

‘lawfare’. Indeed, the investigations into his wife and brother were initiated by complaints from an association called ‘Manos Limpias’ (Clean Hands), an anti-corruption activist group which considers itself a trade union with an interest in fighting political and economic corruption. However, the group also has links to the Spanish hard right.

The pool of corruption allegations occurs in the context of Mr Sánchez’s political precariousness as the leader of a minority coalition government whose popularity has steadily declined to the benefit of the centre-right Partido Popular and the hard right party Vox. As such, Mr Sánchez’s political survival depends on the support of his coalition partners and his party, which is declining in opinion polls.

Sánchez’s wish to promote an image of a feminist and anticorruption government has become difficult to defend in light of the numerous scandals that have hit the government. Even if many or all allegations turn out to be false, the feeling of mistrust will remain cemented in the minds of millions of Spanish voters, and it remains unknown what knowledge the Prime Minister had about the allegations of sleaze before they were made public. The scandals over the past two years have overshadowed Spain’s strong economy, which is expected to grow by 1.9% next year and 1.7% in 2027.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court cleared Sánchez of any criminal liability for the 228 deaths caused by floods in Valencia last year. However, the perception of wrongdoing in the public mind is far more potent than a mere legal ruling. In 2023, his decision to U-turn and grant Catalan separatist politicians amnesty in exchange for a coalition agreement angered anti-separatists in Catalonia and attracted accusations of writing a “blank cheque to the independence movement.”

Since he became Prime Minister of Spain seven years ago, Sánchez has tried to argue that not all politicians are the same. However, as he leads a deeply mistrusted administration, Sánchez may be destined to suffer the same humiliating fate as his predecessor.

11 years have passed since the 2014 overthrow of Yanukovych during the Revolution of Dignity, the Russian occupation of Crimea, and the outbreak of the War in Donbass. As many Western analysts predicted, the 2014–15 Minsk Agreements did not guarantee peace. We are now over three years into the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation and (despite limited changes in the frontline) the shift in the politics of the conflict cannot be understated as a lame-duck Biden presidency in the US is replaced by a second, more radical Trump Presidency. As Trump and the GOP rapidly decouple the US from global geopolitical norms and their security commitments from Europe, the fate of Ukraine has become much less certain.

Trump made it clear during his 2024 election campaign that he would be changing the fundamentals of US foreign policy and famously boasted of his ability to end the Russo-Ukrainian War within 24 hours of his inauguration, if elected. His actions have spoken much louder than his words. Eight months on from his inauguration, Trump has not brought peace, but has instead flipflopped between halting military and intelligence aid to Ukraine, reinstating aid and threatening further sanctions on Russia, to simply signalling his disinterest and seemingly ‘washing his hands’ of the war. The motivations of President Trump are rarely clear to the public, but his recent disengagement with the Ukraine ‘issue’ lines up perfectly with his rare Anchorage Summit on August 15. Trump gambled his foreign policy prestige at the meeting and lost, humiliated by Russian President Vladimir Putin and his entourage. So, what went wrong and why was there no concrete action in Anchorage?

Putin, his government, and his armed forces have stubbornly held onto the same set of conditions throughout the entire three years of conflict. The Russian government has continued to assert its right to maintain control over five Ukrainian provinces post-war: Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia (only Crimea and Luhansk are fully occupied). Russian negotiators have also demanded that Ukraine be forced

Coby Saxby; 2nd Year, Politics and International Studies, Eastbourne

to adhere to a number of political, economic and security concessions — including demilitarisation, special treatment for Russian language and culture, as well as one of the most contentious issues of the peace negotiations: a ban on Ukrainian accession to NATO. Ukraine views joining NATO as a method of deterring a future Russian invasion post-war. The unwillingness of Moscow to scale down their long list of demands, and the unwillingness of Kyiv to accept a nigh-suicidal peace deal, means that this war has continued with no sign of stopping.

To maintain such a state of affairs is unsustainable, immoral and damaging to not just European democracy but global stability. The strength and unity of the NATO alliance has already been broken through its continued inaction; a lack of common policy or clear direction amongst members has damaged the deterrent value of Article 5 of the NATO Charter — placing European citizens at risk and empowering not just Russian aggression, but aggression from other authoritarian states. Most importantly, every day this war continues to cause further death and destruction to Ukrainian life and property. There is no reasonable excuse to delay an end to this war, and if peace cannot be achieved through negotiation there is little other realistic option than to escalate indirect pressure on the Russian economy and armed forces.

To achieve a sustainable and just peace that will preserve Ukrainian political sovereignty and territorial integrity, the European community must agree on a swift — but realistic and fiscally-stable — timeline for the expansion of shipments of military and economic aid to Ukraine. The West paid the price for its misplaced drawback of aid to Ukraine following months of Ukrainian offensive victories in the early months of the war, and it would be prudent not to make such a mistake again. To codify this reformed program, the EU and NATO should work in defiance of Moscow’s demands and accelerate efforts to integrate Ukraine into the European economic and security frameworks rather than delaying efforts until the cessation of hostilities. Ukraine has managed to hold Russian forces at bay in a state of nigh-stalemate for the past year, expanding its indigenous longrange strike capabilities to a point where Ukrainian strikes are now placing noticeable pressure on Russian energy. The costs of this war for Russia are mounting as territorial gains falter. With this summer’s offensive operations providing little gain for Russian forces the best method to end this war is not to give Putin respite, but to convince him this war is unwinnable. Only then can a just peace be agreed upon.

This August marks the 60th Anniversary of Singapore‘s emergence as a sovereign state. In 1965, few observers believed this tiny, resource-scarce, underpopulated island could survive, let alone thrive as much as it has. Yet six decades on, the “Lion City” is one of the world’s most developed economies.

The development of Singapore is the definition of an anomaly. It consistently ranks near the top for infrastructure, education, and quality of governance. The story of Singapore’s nation-building is remarkable, but 60 years on, the state faces some defining questions: is its model sustainable, and is the city-state starting to show signs of drift?

Singapore’s transformation is often reduced to “discipline and efficiency” under the People’s Action Party (PAP), but it was a multitude of policies that brought the small nation prosperity.

The PAP built the institutions that underpin its development: a meritocratic civil service, a trusted judiciary, and a strong anticorruption framework. These have all worked to attract foreign investors by building a level of trust and reliability.

The government deliberately constructed a shared national identity built out of its diversity. It succeeded in mixing Chinese, Malay, Indian and Eurasian communities through policies such as public housing quotas to prevent ethnic enclaves.

Equally important was an ethos of strategic pragmatism. Without natural resources, many countries would struggle, but Singapore positioned itself pragmatically. It cemented itself as a global trading hub and invested heavily in education to develop a skilled workforce that could deliver in high-tech industries and services. This meant the economy was not based on manufacturing, where the economy becomes a race to the lowest price, but a quality-

Jack Keen; 2nd Year, Politics and International Studies, Hemel Hempstead

based, sustainable service centre.

It also developed sovereign wealth funds such as Temasek and the Singapore Government Investment Corporation (GIC), which became long-term anchors for national savings.

The result: from 1965 to today, Singapore’s GDP per capita has risen from under $1,000 to over $80,000, and it is considered a highly developed country.

The PAP has been in uninterrupted power since independence, a feat matched by few parties worldwide. This stability reassured investors and allowed long-term planning without the volatility seen in many young states, but it has raised questions over democratic freedoms.

Yet, as the May 2025 general election showed, this dominance is no longer unquestioned. The PAP has secured another term, but with its thinnest margin in decades. Younger voters, more exposed to global media and less tied to the founding generation’s gratitude, increasingly view one-party rule as complacent, unnecessary and arcane.

Alternative parties such as The Workers’ Party have tapped into concerns about inequality, housing affordability, and climate resilience. For many young Singaporeans, the question is not whether the PAP has delivered; most concede it has, but whether it can still innovate in an increasingly uncertain and pluralistic world. Furthermore, ironically, the PAP’s greatest asset, its reputation for stability, risks hardening into its greatest liability. Young Singaporeans are viewing this inflexibility as a weakness in a society that is now far more diverse in opinion and rapidly changing.

The media often highlights Singapore’s public debt as a key crack in the otherwise thriving economy. It often makes headlines because it is among the highest in the world when measured per capita. On paper, the state owes more than 160% of GDP.

Although, as is often the case, the headline figure is misleading. Unlike other heavily indebted countries reliant on foreign borrowing, Singapore’s debt is issued mainly to develop a domestic bond market and to provide safe investment vehicles for its citizens’ compulsory savings under the Central Provident Fund. The proceeds are invested by GIC and Temasek, generating returns that usually exceed the cost of borrowing. In short, the debt is backed by assets, a rare situation globally.

While fiscal pressures are rising due to healthcare and ageing demographics, Singapore remains in one of the most secure fiscal positions worldwide. Debt, then, is less a crisis than a technical feature of the city-state’s unique financial system.

Critics argue that Singapore at 60 feels more cautious, less

Myanmar, a country which has long grappled with deep ethnic divisions and political unrest, now finds itself at a crossroads following the military’s announcement of December elections. This will be the nation’s first election since 2020, when the National League for Democracy (NLD) saw a landslide win which was soon overturned by the military in the 2021 coup. Since then, the military, also known as the Tatmadaw, has been in power, initially sparking peaceful anti-coup protests, escalating into the nationwide civil war seen today.

The humanitarian impacts of the conflict have been devastating, with more than 3.5 million displaced people and nearly 6,800 civilians killed. While the announcement of elections may present itself as an opportunity to return democracy for the people of Myanmar, questions are raised on the extent to which these elections can facilitate genuine progress, the significance of the country’s dependence on China and the risk of permanent war.

On paper, the military’s announcements of an election suggest a path back to democracy. In reality, the elections are regarded by many as a tool for the military to consolidate and legitimise its power, and this can be seen through many of its own actions and responses from both opposition groups and the international community. Firstly, the degree to which these elections will be free and fair is severely constricted by the fact that the junta have introduced strict new penalties for those protesting its planned elections, with consequences including various prison terms and even the death penalty at the extreme. Essentially, this legislation silences dissent, creating the illusion of support for the military when, actually, dissent is stamped out.

On top of the new laws, opposition groups will play a key role in the validity of the planned upcoming elections. The NLD have notably pledged to boycott the election, with other anti-junta opposition groups also refusing to take part. In fact, in addition to this, the junta have also barred some opposition groups from standing in the election. With little to no contest, the concept of a democracy is undermined and this highlights the role the election will play as a mere narrative for continued military rule rather than a pathway to resolution and an end to the violence.

visionary than in its earlier decades. The city is wealthier but also more unequal, its housing policies are under strain, and its education system is criticised for stress and conformity. With growth slowing, some worry the model that once looked exceptional now risks the same stagnation other boom countries now experience.

However, to call this a “loss of direction” may be premature. Singapore’s leaders, from Prime Minister Lawrence Wong onwards, recognise the need for renewal. Already things have changed: climate adaptation projects such as massive coastal defences, investments in green finance, and attempts to reposition as a hub for AI and biotech show a continued willingness to adapt to modern issues, and show how Singapore continues to seize the opportunities that the 21st Century presents it with.

The political atmosphere has also shifted: policies now face more scrutiny, and often have more dissent and public debate than before. Whilst the country’s political system is far from perfect, it is improving and modernising to meet the demands of the youth.

While at first glance the election may seem like a promising thought, it seems more likely than not that it is a facade. A thought echoed by much of the West and even those on the ground, with one citizen stating, “I don’t think the election will hold any significance for the people. I think this election is only being held to give power to military dictators until the world ends.” Beyond this, consideration must also be given to China and its role in the country.

In the past year, in particular, China has been a lifeline for the junta, providing crucial support at the Chinese border by helping broker peace agreements, negotiating ceasefires, and providing much-needed financial support. For China, its own interests undoubtedly remain a priority. While it was initially wary of offering support, Myanmar‘s position as a source of rare earth minerals sparked economic interest. Now, most of Myanmar’s rare earth minerals mined are sent to China, and the junta are propped up with China’s backing. However, while it is viable to believe that China will want military rule, as it protects their economic interests, this support does not necessarily extend to Min Aung Hlaing, the armed forces chief currently holding primary power. As such, for China, elections must take place as planned and are seen to them as a “quid pro quo” for supporting the regime.

With this and the likely outcome of the election in mind, the risk of a permanent war is real. Despite the junta currently controlling less than half the country, violence has intensified, and prospects for negotiations with opposition groups seem weak as the military is unwilling to concede and opposition groups are increasingly angered.

The election results could also prompt new waves of violence. Moreover, problems arising from the conflict, such as environmental damage, poor public health, and low aid, are likely to add fuel to the fire, further angering citizens and groups, prolonging the war. As such, what Myanmar may see is a continuous war with fractured governance and local powers dominating certain regions despite the elections. For any hopes to overcome this, there needs to be coordinated international action, and there must be an environment for a free and fair election to take place.

Recently the news has been filled with instances of world leaders expressing widespread condemnation of Israel’s military actions in Gaza. Yet reports of murdered journalists, hospitals struck by missiles, and the loss of life due to man-made starvation still file in on a regular basis. Whilst the eventual outcry is welcomed, the belief that issuing statements of condemnation and criticism is sufficient to alleviate the suffering of innocent people in Palestine is callous.

This hesitation from politicians worldwide has resulted in a death toll of over 60,000 Palestinians since October 7 2023. Food, clean water and medical aid has been severely restricted – resulting in one of the most extreme humanitarian crises in recent times. According to WHO, nearly one in five children living in Gaza City is now acutely malnourished with over 5000 children admitted for treatment in June and July alone. Whilst famine has now formally been declared in Gaza, the health infrastructure continues to stay under siege, with 94% of Gaza’s hospitals damaged or destroyed. As of May 2025, only 19 of 36 hospitals remained operational, yet there has been a clear sign of intent that the targeting of hospitals will not cease.

On August 25 2025 a double Israeli strike on the ‘Nasser’ hospital in Khan Younis killed 20 people including five international journalists working for outlets such as Reuters, Al Jazeera and Associated Press. Once again, these attacks were deemed “horrific” and “intolerable” from leaders like Emmanuel Macron, yet the intentional targeting of medical infrastructure and journalists are official war crimes under the Geneva Convention (1949). The question is raised as to why world leaders are so hesitant to hold the Israeli government to account, especially when their intentions are clear; to achieve “maximum territory and minimum (Palestinian) population”, as articulated by Israel’s finance minister Bezalel Smotrich.

The barring of international journalists from Gaza further obscures the reality on the ground, allowing potential war crimes to unfold away from global scrutiny. Instead, fragments of testimony from doctors and aid workers provide the outside world with a glimpse of the crisis. When external journalists attempt to challenge this lack of transparency, their questions are too often deflected with the argument that it is too ‘dangerous’ for journalists to operate there.

One of the most significant tools the state of Israel has employed is the cultivation of fear. In the aftermath of Hamas’ attack on October 7 2023, Israel has effectively leveraged the horrors of that event to frame almost any criticism of its actions as support for the terror group. This strategy has been reinforced by the dangerous practice of labelling critics as antisemitic, a tactic that has become a key factor in the reluctance of many politicians to pursue stronger measures to hold Israel to account. Israel has fostered a widely accepted narrative that advocating

Zaid Patel; 2nd Year, Politics and International Studies, London

for a Palestinian state, or calling for an end to ongoing bombardment, is equivalent to supporting Hamas and opposing the Jewish people as a whole. It is this conflation – between criticism of government policy and hostility toward an entire religious population – that has left many political leaders paralysed. Regarding the US, strong action against Israel is almost non-existent due to the vehement influence of AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) on US politicians. AIPAC themselves state that they supported 362 pro-Israel Democratic and Republican candidates in 2024 and “stand with those who stand with Israel”. This influence often translates into unconditional support for Israel as it allows for a better chance at winning elections, regardless of the illegality of the actions that the Israeli military carry out in the Gaza strip. As a result, many lawmakers have limited themselves to simple symbolic gestures of condemnation, whilst avoiding legislation that could reduce arms sales that would directly affect the bombardment of civilians.

At the moment, it feels as though little can be done to truly help the Palestinian people. Israel has repeatedly rejected recent ceasefire proposals from Hamas, signalling that the conflict is no longer centred around the rescue of the hostages, but rather on the systematic destruction of an entire population. Meanwhile globally, voices are growing louder: families within Israel itself demand the release of the hostages and an end to the conflict, a film about Hind Rajab-the young girl killed in Gaza- received a standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival, and leading scholars from the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) have declared that Israel’s actions amount to genocide. Yet despite this mounting recognition, those with the power to intervene are seemingly unmoved. The world is awakening to the reality of Israel’s end goal, but the decision-makers continue to adopt a cautious approach.

Condemnations, criticisms and press releases have proven meaningless against the daily starvation, displacement and inhumanity that covers the news on a weekly basis.

What is needed is not more rhetoric but decisive political will. Leaders that are prepared to confront the backlash of a genocidal state, challenge powerful lobbies, and act on the principles of the same human rights that have been defended numerous times throughout history.

Alice Richardson; 3rd Year, PPE, Buckinghamshire

‘Greenwashing’ or an Infringement on Democratic

The Gulf states are notorious for their production and exportation of oil. However, as more countries move away from non-renewable energy sources, they have faced the dilemma of what to replace such a major contributor to their economies with when oil loses its value relative to other forms of energy. The process of economic diversification has been a major priority in recent years, with tourism and some investment in renewables being the main solutions to the inevitable problem of the demise of the oil industry. Scepticism, however, surrounds the sincerity of these projects, as, rather than a reduction in their oil production, many countries in the region have continued to seek deals abroad to make the most of the value of oil while it is still retained.

The efforts of Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE to economically diversify with the planet in mind are known internationally. Qatar constructed a solar power plant in preparation for hosting the World Cup in 2022, which would have the capacity to generate 10% of its maximum usage at peak times of the day. Saudi Arabia is currently in the process of constructing Neom, a carbonneutral, net-zero city. The UAE hosted the COP28 conference in Dubai in 2023. All these projects point in the direction of an overtly more climate-conscious future for the region, and perhaps as international pioneers of how other nations could take a primary role in the efforts to protect the environment. But, as ever, we must remove our rose-tinted glasses and consider the reality of these efforts. The treatment of migrant workers in Qatar from South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, and Nepal following their successful bid to host the World Cup resulted in 6,500 deaths. Saudi Arabia’s Neom project has posed similar concerns. Meanwhile, the COP28 conference was considered controversial internationally, with trade deals signed with the host country at the heart of the debacle. Without going so far as to say their actions were hypocritical, there is certainly sufficient evidence to support concerns about the genuineness and sustainability of efforts to compensate for the damage caused by the oil industry.

The growth of the tourism industry beyond these events introduces another layer of complexity to the story. While international

investment into projects such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi should be positive indicators that oil will soon be left in the past, with the intention of seeking revenue through the celebration of art and culture, human rights abuses in the production of these projects are still rampant in the region. It seems that, whenever a clean slate has seemingly been turned over, the same oppression and mistreatment of workers remains the backbone of its ‘success’. In no context does it seem right that this would be a reasonable sacrifice to make for the sake of a greener future. It should not be that the two scenarios are mutually exclusive. The solution seems pretty self-evident: to improve the laws protecting the migrant workers to break the vicious circle of abuse in which they are trapped. In doing so, perhaps we could look at the projects with less scepticism about their earnestness and instead be filled with hope for the future, both for the region and the planet’s sake and for those who work to make those projects a reality.

Is it fair, therefore, to describe the projects to reduce the carbon emissions of the Gulf States as a façade, or even greenwashing? If we consider the current state of affairs as discussed above, I don’t think describing them as the former would be unreasonable. The countries and organisations that financially support these in the name of reducing emissions should also consider themselves complicit in the continued human rights abuses. In the build-up to the World Cup in Qatar, FIFA openly advised the football teams to “focus on the football”, as Qatar had introduced a number of reforms to protect its migrant workers. If organisations and countries that wish to invest in a greener future do not stand up for the labour force that will make these projects a reality, how can we consider these to be progressing the fight to protect our planet and everyone and everything that lives on it?

Whether we should consider the human rights abuses that come with expanding tourism projects to be greenwashing is perhaps debatable. There is no excuse for allowing the continued mistreatment of workers in the name of economic diversification, but whether this fits the definition of greenwashing is another matter. If the Gulf States are to continue to find new avenues to acquire wealth, it should never be at the expense of foreign labourers losing their lives. This is not just a matter of greenwashing – it is a matter of democracy, and the entitlements that should exist alongside it.

If you were to compare maps to university subjects, then the Mercator projection would be Politics. It is ubiquitous, everyone has an opinion on it and competing alternatives abound. Yet the Mercator is now coming under sustained pressure, with the African Union (AU) having thrown its weight behind the Correct the Map Campaign, which calls for the Mercator’s replacement by the Equal Earth Map.

First conceived of by Gerardus Mercator in 1569, it has become beloved amongst navigators due to its ease of use. Whilst I won’t bore you too long with the technical details (there’s a reason I didn’t study geography), the Mercator map was designed to preserve loxodromes. These are lines of constant bearings which are easy to utilise for sailors using charts and compasses to navigate.

Fast-forward to the present day and the Mercator map retains its usefulness by being the only map projection appropriate for online mapping services. The Mercator’s properties mean that a Google Maps user can zoom into the image and see their location mapped out with no distortion of shape or direction, with that image matching any other local maps they might own.

However, the often quoted statistic around the Mercator is also the most damning, namely that Greenland and Africa appear the same size on the map, despite the former being fourteen times smaller in actuality than the latter. As a famous clip from the show The West Wing states, we as humans unconsciously tend to equate size with importance. According to this line of thinking, the Mercator leaves Africa misrepresented and underestimated.

Therefore, proponents of a change away from the Mercator believe it is long overdue. If this is to be the ‘African century’, when the continent achieves the peace and prosperity that has eluded many countries post-independence, should the world not adopt a map which reflects its true magnitude?

The Correct the Map website includes a petition which has to this point garnered around as many signatures as your local NIMBY group. This perhaps points to a general ignorance around the unrepresentativeness of the Mercator and to the issue’s lack of salience in a time where the African continent faces more immediate issues. Additionally, its proposed Equal Earth map, while doing an admirable job at preserving the actual size of nations, distorts their shapes. This renders it useless for everyday navigation.

Joakim Mol Romero; 3rd Year, Politics, Denmark

According to the AU itself, its decision to back Correct the Map is aligned with its goal of “reclaiming Africa‘s rightful place on the global stage”. The AU appears to hold the belief that a change in cartography can lead to a meaningful change in attitudes. Fara Ndiaye of Speak Up Africa, says the African Union’s adoption of the cause is “a historical milestone”, which “transforms a cultural demand into a political one”.

Yet to wantonly dismiss and ditch the Mercator map is to ignore the various purposes maps serve. The reason it first gained prominence and is still going to this day is not because of an imperial conspiracy on behalf of European countries, but because it offered the most accurate representation of the seas. It is not as if there exists a powerful pro-Greenlandic lobby preserving its inflated size. As a letter to The Guardian recently put it, European civilisation is guilty of centuries of crimes against the global south, but the Mercator projection is not one of them.

The main reason the Mercator is here to stay comes down to the C-word, convenience. The landscape of different map projections is so extensive that it is difficult to navigate (excuse the pun). Yet so long as alternatives such as the Equal Earth projection prioritise accurate size over practical convenience, they might be useful as educational tools but not for navigation- the original and eternal function of maps.

Nevertheless, there has been significant progress amongst global organisations in shifting away from the Mercator. Given the maps they use are for purely representative purposes and not practical ones, they seem ripe avenues for reform. The World Bank primarily uses the Winkel and Equal Earth projections and has begun phasing out the Mercator in its web maps. Pressure is mounting for the UN to make a similar change. It is vital for these decisions to not remain symbolic, and to be accompanied by a shift in treatment for Africa.

Another fruitful avenue for change is in the education system. Instead of unquestioningly hanging Mercator maps in the classrooms, geography teachers would do well to explain different projections and their respective drawbacks.

Overall, this has not been an attempt to de-problematise the Mercator given the way it diminishes humankind’s cradle, but rather an acknowledgement of its continued necessity. At the end of the day (as an avid Shakespeare fan would say), there is nothing better than the globe.

Cameroon stands at a crossroads as it heads to the polls in an election that could reshape

On July 13 2025, President Paul Biya, 92, announced he would seek his eighth mandate in the October election – potentially keeping him in power until nearly 100 years old. The world’s oldest head of state, Biya, has ruled since 1982 and continues to avoid naming a successor, fuelling speculation surrounding his health, which the government has publicly denied. Calls for the president to step down have grown from opposition parties, civil society, the Church, and even political allies. Despite this, Biya has pledged to prioritise women and youth. Meanwhile, the election is overshadowed by armed separatists’ conflicts, Boko Haram attacks in the north, and economic struggles. Against this turbulent backdrop, the spotlight turns to who among Cameroon’s opposition can pose a serious challenge to the man who has long defined the state itself.

Maurice Kamto, the leader of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (MRC) and Biya’s most formidable opponent in 2018, has been disqualified from the presidential race – a significant blow to the opposition. Kamto had emerged as the leader capable of unifying disparate opposition forces, drawing cross-ethnic support, winning 14% in the 2018 election, and having sympathisers within rival parties. Yet the Constitutional Council barred his candidacy, citing a rival Manidem faction’s endorsement of another candidate – a technicality his lawyers denounced as a political manoeuvre. His exclusion has left the opposition scrambling. Only 12 candidates were validated, in a process many argue was carefully managed. Among those approved, two candidates stand out: Cabral Libii (45) a young parliamentarian with growing grassroots momentum, and Akere Muna (72) the international lawyer and anti-corruption crusader presenting a bold five-year plan to transform Cameroon. While they are the biggest threats to Biya’s presidency, others could shape the race. Northern figures, Bello Bouba and Issa Tchiroma Bakary, could chip away at Biya’s stronghold, though decades of loyalty to Biya’s system undercuts their message. The central question remains: can these candidates unite to form a winning coalition?

Cameroon’s opposition would need a miracle in October, not because Biya has a firm grip on the country, but because it is its own worst enemy. Cameroon has more than 150 registered parties, with over 50 parties pledging allegiance to the ruling CPDM. This fragmentation has crippled any prospect of a

unified front. For decades, Biya has benefited from the divideand-rule politics, exploiting the deeper problem of opposition leaders’ inability to overcome personal egos and mistrust. Efforts at coalition-building collapse as quickly as they are announced. In 2024, two alliances were declared illegal, and the most recent meeting on August 2 – which included figures like Prince Michael Ekosso of the USDP – ended without a candidate, highlighting the opposition’s inability to reach consensus despite agreed criteria.

Biya has cracked down on the opposition, imprisoning Kamto’s allies, silencing civil society, and suspending NGOs, the real barrier to change lies in the opposition’s persistent fragmentation. The opposition has the potential to challenge the regime, but unless it demonstrates a real commitment to unity, its leaders will continue to undermine themselves, striking out against their own chances long before Biya needs to act.

Breaking the CPDM’s dominance wouldn’t come from destroying Biya’s system alone, but overcoming two deeper issues, voter apathy and opposition solidarity. While the president’s allies control the Constitutional Council and the electoral system gives the incumbent an advantage, these are not decisive barriers. The real advantage lies in the disillusioned electorate. In 2018, 46.7% of people abstained from the election, compared to 19.6% in 1992. Cameroon should take inspiration from its Senegalese counterparts, who in 2024, guarded vote tallies to unseat the ruling party. If Cameroonians want change, they must turn out in numbers and defend their votes.

Additionally, unity is crucial. The closest Biya came to losing power was in 1992, when the Union for Change coalition mounted a serious challenge; many observers still believe that the election was stolen. That precedent remains instructive – only a unified opposition can consolidate discontent into a credible threat. Without cooperation and mass participation, Biya’s eighth mandate will not be won at the ballot box; it will be handed to him.

As Cameroon heads into October, its future depends less on Biya’s promises than on the resolve of its citizens and leaders. Structural bias gives CPDM an edge, but systems do not vote, citizens do. If Cameroonians stay home and the opposition continues to splinter, the result is already written. Yet Africa has shown another path. In Senegal last year, voters stood watch over their ballots and, through solidarity and determination, unseated a ruling party many thought unshakeable. The lesson is clear, when citizens unify and defend their votes, even the most entrenched regimes can fall. Cameroon is no exception.

Lily Hatch; 2nd Year, Politics and International Studies, Windsor

On May 22 2025, New Zealand’s government announced their budget for the fiscal year of 2025/26. One of the most notable aspects of the budget is the new Defence Capability Plan (DCP), which outlines a controversial plan doubling defence spending to 2% of the nation’s GDP. With a population of only 5.3 billion, such staggering shifts considering the military have always been a difficult sell, and so it comes as no surprise that the change has been met with a flood of opinions. With the increase in defence spending directly affecting the monetary attention other departments receive, particularly those addressing social issues, the DCP has many critics — is the drastic change well founded, or is it an overreaction?

New Zealand has made it clear that over the next four years, they intend to invest roughly NZ$12 billion under a long-term blueprint for their defence forces, NZ$9 billion of which is new funding. The long-term plan is a deliberate decision designed to allow the country to “adapt as the world around us changes” and “scale up as the fiscal situation allows”, according to the DCP. The government has repeatedly made clear that the change is in response to an international “deteriorating strategic environment”, and the increasing necessity of military equipment due to geopolitical developments. This includes the RussoUkrainian war and Russia‘s “blatant disregard for international law”, current conflicts in the Middle East, and tensions between China and the USA over the Indo-Pacific region. With these conflicts taking centre stage in global affairs in recent years, New Zealand’s concern is surely well-founded, but disquiet persists over the wider repercussions of the plan.

The majority of complaints surround where the funds for the new budget is being taken from; which other departments are being disadvantaged to redistribute money into defence? The New Zealand government has cut multiple social care programmes in order to facilitate their new military budget, which naturally concerns the public. Critics have outlined three main social care programmes that have received major cuts as a result of the Defence Capability plan, affecting the working class, pensioners, and the homeless. To begin with, 33 separate pay equity negotiations have been cancelled, which were set to increase the pay of workers in female-dominated industries such as teaching. Secondly, the government has reduced funding for ‘KiwiSaver’, a retirement scheme which provides pensions for most workers

(as of 2023, almost two-thirds of Kiwis held a KiwiSaver account). As it stands, people can claim NZ$521 per year from the state — however under the new budget, this amount has halved in aid of the DCP. Third, NZ$1 billion is set to be cut per annum from emergency housing plans for the homeless, which many view as the main drawback considering 2.3% of the population are ‘severely deprived’ of housing.

With workers, pensioners, and a deepening homelessness crisis finding themselves victims of the new budget, we’re seeing a clear prioritisation of national security over tackling pressing social issues from a nation with historically low defence spending. The defence budget has remained consistently low at 1% of GDP since the turn of the century, following on from a gradual decline from the budget’s highest point of 3% in the 1970s and 80s. Whilst it is true that hostilities are spreading across the globe, the fact that these issues outweigh addressing pay equity, living standards, and social housing, could be more than just a symptom of increasing geopolitical tension.

For example, the shift in policy and spending focus could indicate where New Zealand’s aspirations lie on the international stage. The country’s eagerness to enter a state of military readiness could foreshadow a future in which New Zealand is not just prepared to but distinctly willing to enter global conflicts. With such a drastic increase in funding, the nation is clearly preparing itself to fight back against its perceived security threats, but also to become a stronger ally in international unions. With concepts developing such as CANZUK — a proposed alliance between Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK — it stands to reason that New Zealand is putting itself on an upwards trajectory in the international order, beginning with major upgrades to their military.

Ultimately, New Zealand’s decision to redirect billions from social programmes to defence spending highlights the difficult balance between safeguarding national security and meeting the immediate needs of citizens. New Zealand must now carefully navigate this trade-off, whilst it shifts to a potentially more assertive role on the global stage.

In PAIS we value your feedback; we know this is a challenging time and we want to do all we can to support you to succeed. Based on your ideas, we have put together an exciting agenda of events, activities and opportunities this term and beyond - please check our emails, social media and webpages for more details.

In PAIS we value your feedback; we know this is a challenging time and we want to do all we can to support you to succeed. Based on your ideas, we have put together an exciting agenda of events, activities and opportunities this term and beyond - please check our emails, social media and webpages for more details.

In PAIS we value your feedback; we know this is a challenging time and we want to do all we can to support you to succeed. Based on your ideas, we have put together an exciting agenda of events, activities and opportunities this term and beyond - please check our emails, social media and webpages for more details.

Academic support for students is a top priority for PAIS so please:

ACADEMIC SUPPORT

Academic support for students is a top priority for PAIS so please:

-Sign up for our Virtual Common Room chats on a range of topics including essay wrtiting, wellbeing and the liberated curriculum.

-Benefit form our online workshops on essay writing for second years and finalists.

-Benefit from our online workshops on preparing for your online open book exams.

-Sign up for our Virtual Common Room chats on a range of topics including essay wrtiting, wellbeing and the liberated curriculum.

-Benefit form our online workshops on essay writing for second years and finalists.

-Benefit from our online workshops on preparing for your online open book exams.

In response to your feedback, we have put together detailed online guides on making your study choices, including whith modules to takes, which assessment methods to choose and advice on applying to postgraduate study.

In response to your feedback, we have put together detailed online guides on making your study choices, including whith modules to takes, which assessment methods to choose and advice on applying to postgraduate study.

We want to hear from you and have a number of opportunities for you to feed-back on your course throughout the year including via your Course Reps and our end-ofyear module evaluation surveys. There is also the National Student Survey (NSS) which will open for finalists on Monday, 8th February -we would love you to complete it!

We want to hear from you and have a number of opportunities for you to feed-back on your course throughout the year including via your Course Reps and our end-ofyear module evaluation surveys. There is also the National Student Survey (NSS) which will open for finalists on Monday, 8th February -we would love you to complete it!

Following your feedback, we are running an Employability Series with a number of exciting speakers from a range of careers speaking at events this term. Details will be shared shortly.

Following your feedback, we are running an Employability Series with a number of exciting speakers from a range of careers speaking at events this term. Details will be shared shortly.

Embed yourself in the PAIS research culture and ettend our Wednesday Research Seminar Series which is open to all PAIS staff and students. Finalists are also encouraged to join the Burning Issues: Geopolitics Today MA lecture series which focuses on contemporary world politics.

Embed yourself in the PAIS research culture and ettend our Wednesday Research Seminar Series which is open to all PAIS staff and students. Finalists are also encouraged to join the Burning Issues: Geopolitics Today MA lecture series which focuses on contemporary world politics.

Follow Us on Social Media to find out more:

www.twitter.com/PAISUndergrad www.facebook.com/paiswarwick www.instagram.com/paiswarwick

Follow Us on Social Media to find out more: www.twitter.com/PAISUndergrad www.facebook.com/paiswarwick www.instagram.com/paiswarwick

Talia Marie; 3rd Year, Politics and Sociology, South-West London

‘Identical twins (raised separately) are more likely to share political views than non-identical twins… having the same genes makes us more likely to agree.’

What’s Your Bias? (2017) showcases some scientific studies on the psychological and sociological factors that influence how humans make decisions on how to vote. Interestingly, this book suggests that we might not be as rational as we think, as humans often vote based on factors we’re not aware of. Overall, I believe that this book succeeds in informing the reader of the surprising biases they may have not thought of before, encouraging more self-reflection on one’s leanings.

Lee De-Wit is a psychologist and neuroscientist; currently a political psychology lecturer at Cambridge University. In his opinion pieces, he refrains from revealing his own political views, instead writing objectively about how others form judgements on public affairs. Rather than push a certain political viewpoint, his work aims to encourage more openness in discussion.

What’s Your Bias has nine chapters. The main claim is that we have less control over our voting behaviours than we think, because genetics and our upbringing are reliable predicting factors for which way we will vote. A fascinating study presented is one on the amygdala, which is an “almond-shaped part of the brain” responsible for fear and how we process and remember emotions — shaping our perception of threat. In a paper titled ‘Red Brain, Blue Brain’, an experiment, led by Darren Schreiber, put people with different political views through a simple gambling game. Overall, the amygdala activity was a lot greater in conservatives’ brains than in liberals’ brains. Essentially, conservatives have a higher sensitivity to potential threats, translating into higher fear of societal changes such as immigration increasing. Genetic experiments like these made me question if it’s ever possible to change one’s fundamental views.