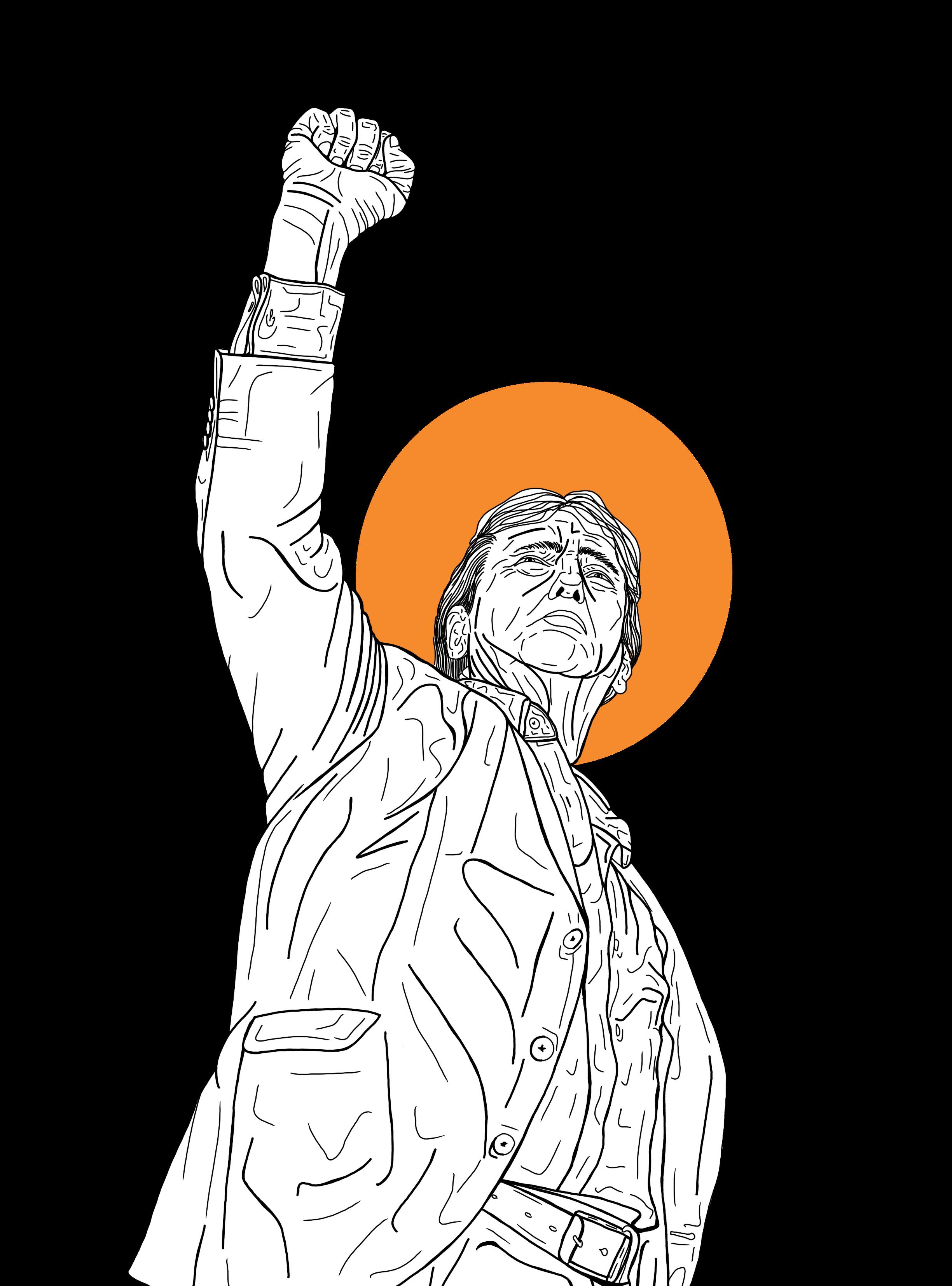

TRUMP 2025

William Raven

William Raven

Welcome back to Perspectives! We are looking slightly different this time around and I absolutely could not be prouder of what the Perspectives team has created in this beautiful magazine. Since taking over in April, this magazine has grown beyond anything I could have imagined, meaning we have had to expand our team and what a brilliant team we have found (truly, there is not enough positive adjectives to describe them). From Jamie, to our deputy editors; Alice, Dan, Evan, Khushi an Will, helping so much with the workload and pitching the articles you are about to read. Our design editors Zita and Rio, responsible for our visual rebrand and this stunning print edition, expertly integrating the work of our brand new additions: the cartoonists, Ben and Lily. Their hard work and creativity, drawing each and every writer in this edition is truly insane. This entire team together is an absolute dream.

This year, we have hosted writers workshops, speaker events, recorded podcasts, appeared in an overnight US election coverage, and launched a brand new magazine aimed at primary school children. I think our aim at providing as many opportunities for writers as possible has become a reality. Though it is hard work, I am loving my time as editor-in-chief, though time is very quickly coming to an end, I can’t wait to see what we can do before the end. Each editor probably says this, but I truly think this edition is the best yet.

including our writers WhatsApp group and website.

2024 marked the biggest year for democracy in history; with more voters worldwide heading to the polls in a single year than ever before. Now, we must deal with the consequences. Edition 48 looks to the future as we all come to terms with the brutal realities of a rapidly changing world. Accordingly, our feature article delves into the very question that is plaguing world leaders – what will a second Trump term look like? The answer to which will likely determine the success or failure of governments across the globe. Edition 48 also reflects on the changing nature of our politics; hosting a debate on the importance of economic growth and cost of living in determining elections and an article delving into the future of the Scottish independence movement. As always, there is something for everyone.

This edition would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of our newly expanded Perspectives team. From the amazing pitches produced by our deputy editors to the fresh new graphics curated by our design team to the brilliant cartoons drawn by our cartoonists; all of them have worked exceedingly hard to produce our best edition yet. As my time as editor-in-chief nears its end, I could not be more proud of what we have achieved since taking over early last year. Speaker events, insightful podcast episodes, live coverage of the 2024 US Election, Perspectives Jr, a new political magazine for primary-aged children, and the award of best specialist publication in the midlands, have all helped to enrich and expand our impact on university life and beyond.

Write for us! send articles and ideas to perspectiveseditors@gmail.com AND join our WhatsApp group for first choice of print and online pitches.

Best specialist publication in the midlands

After not even a month as Prime Minister of Japan, Shigeru Ishiba’s snap election gamble has miserably backfired. The centre-right Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has ruled Japan almost uninterrupted since 1955 and this result marks their second worst ever– leaving the LDP-Komeito coalition 18 seats short of a majority in the House of Representatives; throwing the government into an inferno of chaos and uncertainty. Whilst the Prime Minister would be wise to compromise on some key issues, these concessions could wreak havoc on party support and internal cohesion. Allow me to examine his best approach, the necessary trade-offs, and the likely future of Japanese politics.

Ishiba took the reins amid low approval for the LDP, which has been beleaguered by scandals. The assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe raised questions about the party’s links to the controversial Unification Church in 2022. Meanwhile, the recent ‘slush fund’ scandal provoked the resignation of numerous LDP lawmakers who failed to report ¥600 million (about £3 million) in campaign donations. Following the resignation of the previous Prime Minister, the LDP had slumped in the polls.

Ishiba was brought to lead the LDP as a reformer and ‘opposition from within the party’. Yet, he has alienated his supporters within the party by endorsing mainstream LDP policies and dropping his previously more critical stance. The LDP’s varied and powerful factions are part of why they have lasted in power for so long– they have waxed and waned with public opinion. Ishiba would have hoped that the snap election would capitalise on a poll bounce to solidify a mandate for his policies, but will now have to garner opposition support for legislation or face a short stint in power.

The Democratic Party for the People (DPP) holds the key for Ishiba– the party won 28 seats in the election. Despite being arithmetically able to hold up a coalition government, the DPP showed little appetite for entering one with the LDP. From their perspective, it would make sense to avoid the toxic turmoil of the LDP. It would be far more pragmatic to support the minority government’s legislation on a case-by-case basis, instead of risking losing public support by forming a coalition.

The DPP’s policy platform for the snap election centred around economic policies and the cost of living. Japan has experienced a recent hike in inflation– startling Japanese consumers unused to rising prices following the deflationary period after the pandemic. The DPP capitalised on this to draw support from

younger voters, emphasising its policies on raising the income tax threshold, and expanding tax credits to boost take-home pay.

The Prime Minister’s best response here would be to accept such demands in next year’s budget. Broadly speaking, Ishiba is a proponent of ‘Abenomics’ (the fiscally expansionist policy aiming to bring growth to Japan’s stagnant economy). The LDP and the DPP stance are not too far apart on the economy, and passing the next budget is make-or-break for his premiership. Ishiba would also be wise to collaborate with the DPP on proposed reforms to increase transparency in the wake of the ‘slush fund’ scandal.

Collaboration with the DPP is paramount for the LDP’s prospects in future elections. The latter’s rule in Japan has been marked by remarkable political stability under Shinzo Abe and Fumio Kishida over the last decade. Japanese voters value stability and certainty– providing this would mend broken bridges with alienated voters who defected to other parties.

This is not without its risks, however. If the DPP’s demands are rejected, a motion of no-confidence would likely be submitted and passed, leaving Ishiba’s cabinet with no choice but to either resign or call another election, where they may be punished further. The tail could end up wagging the dog, especially on foreign policy where Ishiba is more eager than DPP members in looking to consolidate ties with the US and regional allies.

The Liberal Democratic Party also faces internal difficulties. Since the election failed to consolidate a personal mandate for Ishiba, other factions– notably the staunch conservative faction led by Ishiba’s leadership contest rival, Sanae Takaichi– could be emboldened to challenge his leadership. He will face wrangling over the direction of the party, particularly on matters such as same-sex marriage and defence policy.

Overall, being able to strike a compromise with the DPP would help the LDP’s prospects in future elections and help prolong Ishiba’s premiership. Short-term collaboration would bring back the stability that has defined the LDP’s time in office. This would help the Japanese electorate forgive the LDP for the scandals that provoked this year’s result. Yet, a fine balance has to be found–if the minority government engulfs itself in chaos, it would not be a surprise to see the Liberal Democratic Party punished once again.

Xavier Fletcher; 1st Year, Economics, Politics and International Studies, Devon

Che Wheeler; 1st Year, History and Politics, London

Too often in the business of diplomacy are the fates of ordinary human lives disregarded and tossed aside in the name of a distant, ulterior narrative, and the need to pursue strong posturing at any cost. The Chagos Islands and its uncertain future is yet another episode, in a long line of instances of geopolitical chess, leaving pawns at the mercy of their king.

The islands, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean, were originally part of the British colony of Mauritius. Before 1973, they were home to the descendants of African slaves. After emancipation, they were known as Chagossians and became the islands’ permanent population. However, the US, looking to establish a base in the Indian Ocean for access to strategic hotspots such as the Middle East and India, signed a secretive deal with the British government that allowed the US to establish a base on the islands – in exchange for cancelling debt on the sale of Polaris missiles to the UK. To allow this, the UK proceeded to “buy” the islands from Mauritius for £3 million, holding onto them after Mauritius became independent. Following this, all 2,000 residents of the islands were expelled by 1973, through methods that would normally be immediately decried as abuses, such as gassing the local pets and buying up the coconut plantations of the islands to deprive the Chagossians of their income. The islanders were left to fend for themselves in either Mauritius or the Seychelles, having never worked outside plantations at home and lacking any form of social mobility.

Despite the botched agreement, Mauritius has continued to claim the islands along with the Chagossians – who desire nothing more than to return home. Although shockingly, following 45 years of legal dispute, the UK ruled out any repatriations for the Chagossians in 2016. Regardless, the International Court of Justice issued an advisory ruling in 2019, stating that the UK did not have sovereignty over the islands, had undermined Chagossian self-determination, and that the islands should be handed to Mauritius as soon as possible. This decision was later backed by the UN General Assembly and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Pressure from this finally caused the UK to renegotiate the status of the islands with Mauritius in 2022. A deal was finally reached in October 2024, which would see the islands returned to Mauritius, and the right to return granted to all islanders not born on Diego Garcia, the island where the US military base is located, in exchange for a 99-year lease for the base.

In purely military terms, despite Trump’s fears of Chinese snooping undermining the base’s integrity due to their influence over Mauritius, the deal is unlikely to change the status quo. Diego Garcia is already one of the most secretive US military bases in the world, with only military personnel present on the

island. Anyone else visiting requires clearance from the US Navy – measures which would remain under nominal Mauritian sovereignty. This is not to mention it has also previously been rumoured to be a CIA “black site”, where hundreds were captured and interrogated there in the wake of 9/11. After all, why is there not nearly an equal amount of concern over the fact Guantanamo Bay, another prominent US military base marred in similar controversy, is located right next door to Cuba, a longtime adversary of the US?

Diego Garcia’s deep seaports, capable of hosting nuclearpowered submarines, will continue to serve as a vital check in a broader US strategy, in cooperation with India, to growing Chinese naval power in the Indian Ocean. This is especially important, given China is increasingly influencing countries in the region and is also acquiring bases, such as its own 99-year lease over Hambantota in Sri Lanka. Diego Garcia ensured that the US Navy had the means to properly deploy naval and air assets in the Indian Ocean if ever an open confrontation with the Chinese Navy were to arise in a hypothetical future conflict.

For the islanders though, this represents nothing more than a sugarcoated justice. Around two-thirds of the islanders lived on Diego Garcia prior to expulsion, meaning the vast majority of the Chagossian community will actually be denied the right to return, continuing much of the struggle for full repatriation. In addition, though both share similar ethnic and linguistic characteristics, concerns have been raised over whether Mauritius, a country over 2,000 miles away, can really represent the islanders’ interests. Considering the Chagossian community‘s overall number of around 10,000 people today, it’s not unreasonable to consider a possible independent Chagossian state. States with a similar population, such as Tuvalu, have emerged in the international community, although this comes with its own issues. Could such a polity, with a projected tiny population and economy, reasonably sustain itself?

In the end, let me remind you that this is far from our choice, or the islanders’, to decide. The real power lies in the distant interests of elites, who see dots on a map rather than living, autonomous human beings, with a right to live freely. I will end this with a remark for you, the reader, to consider: if you and your family were forcefully evicted suddenly tomorrow, with almost no explanation, would you tolerate it?

Daniel Akerele; 1st Year, Law (with French Law), Leicester

How does a celebrity elegantly fall into irrelevance? From rubbing shoulders with some of the biggest names in Hollywood as the rising star of the progressive movement, Trudeau has fallen into the depths of unpopularity, tinkering on the edges of irrelevance. Canada’s Liberal Party has faced some of the most challenging problems of the early 21st century and their performance will be judged next year by the voter. Increasingly, Canadians are now disillusioned with the Liberal mandate. This sentiment is seen in the struggle in the polls, now consistently lagging behind the Canadian Conservatives. How did it get here?

In 2015, Justin Trudeau was able to overturn the electoral performance of the Liberal Party. From having 34 seats in 2011, the Liberal Party secured a comfortable 184 seats as Trudeau beat the odds and ended 9 years of Conservative rule. The election was lost because the Conservatives had expired their democratic mandate quicker than expected and Trudeau offered a strong alternative that renewed hope for the future. Not only a natural poster boy for the elite-endorsed progressive politics of the 2010s, the Liberal Party was able to hang on to this new mandate and instill confidence in the Canadians.This allowed the Liberals were able to maintain a reasonable share of the seats until 2021 when it needed the confidence-and-supply agreement with the NDP (New Democratic Party). This was the first symptom of Liberal decline and the consequences of blending politics, Hollywood and ‘hope’ for a radically different future. Between the pandemic and cost of living issues, Trudeau’s socially upmarket brand has angered Canadians.

A CBCNews poll thinks that there is only a 1 per cent chance that Liberal party could win a majority in 2025. Before discussing polls and predictions, it is well known that these should be taken with a pinch of salt. In 2015, the Liberal party was not predicted to win a majority, however they then defied odds. As this year has demonstrated, political polls always have a level of volatility, even when the winner seems clear. The general sentiment in the polls is that if a Canadian federal election were to be held today, the Liberal Party would be stripped of a majority of their seats. The same CBCNews poll also predicted that they would be down to 60 seats, predicting the Conservatives to reach an amount of 218 seats. However you view the data, one thing is clear: the Liberal Party mandate is rapidly expiring.

But then the question is why? This is first answered by looking at what other Canadian political parties are offering. Importantly, Canada’s political system is much modelled after the UK’s ‘Westminster model’ and electorally they use First-past-the-post, a system dominated by the Conservative and Liberal Parties since the start of the 21st century. The easiest alternative for Canadians is the Conservative Party of Canada, led by Pierre Pollivere. Since Poilievre became leader in 2022, he has run on

an image that is aggressive and bellicose. Columnist Andrew Coyne describes Poilievre not as a future prime minister, ‘but a perpetual opposition critic, someone who is seemingly incapable of taking the high road, who never misses the opportunity for a partisan cheap shot’. Yet despite this criticism, it seems as if Canadians have made up their mind and they desperately want someone else. But why have they turned on Trudeau?

An answer could be found in poor statesmanship. Trudeau admitted that he had ‘made some mistakes’ with his immigration policy. Having originally taken an open doors and liberal stance Canada took on immigration, Trudeau rightly made the decision to limit this policy and be frank with the Canadian people. The more convincing argument however, is the reversal of fortunes seen in strained public services (especially crime and housing), only accelerating the demise of the public perception of the Liberal party. Although no Canadian politicians experienced the same heights of the Truss fiasco that dramatically deteriorated the chances of the British Conservatives in 2022, the Trudeau charm is no longer what it used to be.

It is a trite observation to make that Canada, like other Western countries, is deeply struggling with its economy and that its people are not seeing significant improvements in their lives. And it is also obvious to say that the Liberal Party is more likely than not to lose badly because they were the ones that were caught in the crossfire of the, so far, depressing 2020s. Yet like all things in politics, but especially for celebrity politicians, as some stars dwindle and die, others shine brighter in the dark.

What will it look like?

The first results of the election came from the tiny township of Dixville Notch, New Hampshire, which in a tradition dating back to 1960 is the first to declare. In 2024 the result was to be an equal three-three split. This vision of parity matched the vast majority of polling going into election day which envisaged a tight race decided by a few thousand voters in seven swing states. The tight results were not to last and by the end of the night a jubilant crowd had amassed to celebrate at Mar a Lago. In contrast the crowd at “Harris HQ” was muted, apprehensive and thinning.

Donald Trump fought a hard campaign. On the final day of the campaign alone he managed to visit no less than three battleground states and it is difficult not to have respect for his indefatigability. This was reflected in the results as he achieved a clean sweep of all swing states as well as the popular vote, the first by a Republican since 2004. The seventy-eight year old also managed to survive the political turmoil of felonies, including being found liable for sexual abuse, and multiple assassination attempts. On July 13th, Trump’s “Fight, fight, fight” response to narrowly avoiding being shot became emblematic for the doggedness of both the campaign and man.

Despite this commanding victory Trump has been embattled on multiple fronts and his position appears weaker than it did right after the election. The Republicans were able to win the House of Representatives but only by a majority of one. This tiny majority is difficult for Trump as he will require all Republican representatives to be present and onside. Reminiscent of the 2023 Speaker saga, when fifteen ballots were required to elect a speaker, this could leave the house and entire government in logjam. The other main issue has been his extraordinary cabinet picks including controversy that many thought beyond even Trump.

Ramaswamy and Musk have been nominated to lead DOGE, a nod to the latter’s promotion of cryptocurrencies, a commission intended to improve government efficiency by slashing and burning to save federal funds. Musk is Trump’s new henchman, and he will be integral to the administration. Seemingly inseparable the only division between the pair has emerged recently over immigration policy but for Musk it is also the reward for his $250 million of donations during the campaign. Beyond the self-proclaimed “dark gothic MAGA” sidekick, Trump has faced backlash over his nomination of Gaetz to Attorney General, RFK Jr. to Health, Patel to the FBI and Hegseth to Defense to name just a few. Hegeseth, for example, is currently embroiled in alcoholism and sexual violence accusations as well as that of being generally unqualified for controlling over $842 billion. While that is ongoing, the Gaetz saga is over. Gaetz, already extremely unpopular amongst colleagues, has dropped out after details of illegal sexual encounters with women as young as seventeen came to light.

The domestic policy approach can be inferred from the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. During the election the project was extremely unpopular and Democrats attempted to highlight the connection of Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, to the project. Vance, a young senator from Ohio, modeled in the image of Trump had written the foreword although Republicans generally tried to downplay such connections. The project itself sets an agenda which includes nationwide abortion bans and a database tracking personal information. Ultimately, the prospect of this was not enough to change the minds of over seventy million Americans who voted for Trump although whether Trump will be able to use his narrow control of congress to implement the most draconian of measures remains to be seen. Likely we will see something somewhat in the middle that is more extreme in approach than Trump’s first administration but far more alike in practicality.

The most alarming implication of Trump’s return is abroad

as undeniably the world is more dangerous than it was when Trump left office. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reminded the world that total conflict was not relegated to the past. Recently the October 7th attacks and the following military response has been just one of many regional conflicts around the world. The situations in Sudan, Syria, Myanmar, Kosovo and Georgia also deserve attention and the fear is that with Trump‘s isolationist rhetoric this will not be the case. Israel’s disdain for calls of deescalation by Secretary Blinken demonstrated that America’s global power is no longer held with the same reverence that it once was and Trump’s approach will determine whether this slide continues. Trumps unpredictability, however, means it is just as probable that he assumes a stronger role especially in regard to any possible peace in Ukraine. Trump is known to hate being seen as soft on Putin and he additionally prides himself on his business background. Therefore he may not resign huge swathes of Ukraine but instead fight for a deal in the interests of Ukrainians, or perhaps more so his own ego. The more alarming prospects lie in the Middle East where Trump, who is staunchly opposed to Iran and an equally strong advocate for Israel, will possibly allow the region to be swallowed up by violence.

Picked as the top issue by voters, the economy would be a defining feature of the campaign and Trump’s relentless efforts on economic issues contributed the most to his reelection. This was aided immensely by Harris’s failure to distance herself from “Bidenomics” under which inflation peaked at 9.1%. This was only augmented further by “corporate price gouging” particularly felt in groceries. Comparatively the economy under the first Trump administration saw wages outpace inflation for the first three years and the price of gasoline was half that of the current cost. The result of this was a nostalgia among many to the Trump years. Looking forward, Trump will attempt to broaden supply-side economics focused on reducing taxes and regulation to encourage more growth and this “laissez-faire” approach promises the return of many traditional industries especially in fossil fuels. Trump has also pledged to bring in tariffs of 10% to 20% on all imports in a bid to restore American industry. Tariffs can result in long term job creation however their immediate impact is to directly shift costs to consumers but describing tariffs as “beautiful” Trump seems set on the policy despite the overwhelming criticisms of this policy. Ultimately, tariffs were one of the major policies on which Trump won the election and it would appear weak to back away from them now.

Meanwhile, Trump’s climate change denial and promise to “Drill, baby, drill” will fill many of the world’s poorest nations with dread. Accentuated by climate change, Storm Helene and Milton ravaged the US South-East killing hundreds and leaving thousands more without power. Trump denies the role of climate change despite the mountain of scientific evidence to the contrary. He has promised to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement and seems intent on ripping up initiatives started under the Biden administration for clean energy production. Trump alone will not cause climate breakdown, but it is certain his pro-fossil fuel position will accelerate it. Most significantly his decisions will shape the global narrative. America will be key to any future climate solutions but a second Trump administration will push this back by at least four years and it remains to be seen if this will result in irreparable damage. Additionally a second Trump term will result in further cultural change as the manner in which he brushes off scientific fact presents an alarming trend.

Another consideration is the impact this will have on the future of the Republican party. Currently the party is gripped by a cult of personality with many loyal to Trump more than the party itself. Trump labelled Republicans who did not align with the MAGA movement as “RINOs” (Republicans in name only) and moderates were forced out. Continued on page 5...

When the 2026 midterms are finished, allies and those opposed to Trump will begin to maneuver for the future. Presently devoid of opposition the most likely scenario sees Trump succeeded by MAGA loyalists and even after Trump the Republican party will foreseeably be shaped by his legacy. For the Democrats this will be a period of seismic changes too. The tumultuous fall out of the 2024 election will continue and Democrats must hope for a shift in focus by the party establishment in order to win back voters lost to Trump.

With all these elements considered it is difficult to be certain of how Trump’s second term will look. Perhaps all we can be certain of is that it will be a period of uncertainty. Current indications point to a more extreme administration than the first he oversaw although in practice it will be difficult for him to enact his policies to their full and most controversial extent. For Trump the 2026 midterms will be his final consequential elections and until then he is likely to act with these in mind. Nonetheless, the potential for damage is high and on issues of foreign policy and climate change these are most acute although the true approach is incredibly difficult to decipher especially after having run one of the least policy based campaigns in recent history.

The Chinese-backed mega port in Chancay, Peru, stands to redefine South America‘s global trade relations. Economic prosperity is promised for South America, but the project seems to entrench geopolitical rivalries and instability between China and the US.

This project is under the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the current financial investment is estimated to be USD $1.2 billion. President Xi Jinping attended the port‘s inauguration in November, reaffirming China‘s eagerness to extend its global influence. A significant geopolitical implication of this will be its impact on the China-US rivalry, inevitably leaving South America at a crossroads.

The port‘s capacity to accommodate larger shipping containers and enhance cargo handling efficiency is a promising development. It will not only facilitate smoother trade routes but also significantly reduce transit times between Chancay and Shanghai. This is a significant step towards enhancing trade efficiency. Global Times highlights that China is the largest trade partner and export market in Peru, and Peru is the fourth largest trade partner in South America. Therefore, this project promises significant economic prosperity which is mutually beneficial for these two nations. Additionally, it aims to have a multiplier effect because of its strategic location – aiming to open Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil to Asian investments while bypassing North America altogether.

Leaders and experts have come together to embrace this collaborative endeavour because it aims to improve trade relations and competition significantly. For example, Zhou Zhiwei (Latin American studies expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Science) says in a conversation with Global Times:

„Strengthening infrastructure connectivity is an efficient approach to promote China-Peru economic and trade cooperation, which will help the Latin American country transfer its geographical advantages into tangible benefits.“

This project is set to redefine trade between Latin America and Asia. It is the first project of this size and investment in Peru in recent years, and it has the potential to place Peru as a competitive player in international trade. The main ways that this port will benefit Peru and South America is through the

diversification of supply sources, access to global markets, increased quality and variety of goods, facilitating regional trade, increased job opportunities and arguably most significantly reducing transit times between Chancay and Shanghai. The reduction in time is significant, 35 days compared to 20 (over a week).

2nd year Politics and Sociology, Surrey

South America has been firmly in the US‘s sphere of influence for decades (a distinction highlighted by the Monroe Doctrine). However, in recent years, US influence has significantly diminished; for example, outgoing President Joe Biden‘s first visit to the region was in November 2024 for the Asia-Pacific Cooperation (APEC) summit hosted by Lima, Peru. Therefore, this manifested an opportunity for outside players to invest. The geopolitical implications of China‘s decisive action are a direct challenge to the US, encroaching on their ‚traditional domain‘. Additionally, Donald Trump won the US 2024 election because he would impose tariffs as high as 60% on Chinese-made goods –emphasising that this infrastructure project will inevitably cause uncertainty in the region.

When evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of the BRI as a whole or specific projects such as this one, it is not easy to find tangible examples of economic successes. Often, statistics present an idea of what could happen and estimations of whether BRI is successful. Various websites are dedicated to BRI and explain what the BRI aims to do, but very few state the specific details relating to its actual economic success. One article published by the Financial Times in July 2018 pointed out that 234 out of 1674 Chinese-invested infrastructure projects announced in 66 Belt and Road countries have encountered difficulties. For example, China has invested billions of dollars into infrastructure within Sri Lanka. However, few positives can be drawn from this. The Hambantota port was built in Southern Sri Lanka, and despite being open for years, there seems to be little activity. Hambantota was constructed by a Chinese company with Chinese loans. Sri Lanka was already in debt and is now struggling to repay the $8 billion used to fund the port.

South America stands at a crucial crossroads with the Chancay Port Project. It promises economic prosperity but is shadowed by the risks of mounting debt and geopolitical tensions. The future remains uncertain; however, only time will reveal the true significance of this ambitious endeavour.

-maybe just another win for the far right-

Călin Georgescu is a name that has come up in the last weeks’ newsletters out-of-nowhere. This dramatic development is proving why western media should turn its attention to Eastern Europe.

The 62-year old ‘independent’ candidate has won a sweeping victory in the first round of the elections. He totalled 22.93% of the votes and shocked the public. He ran his campaign almost solely on social-media platforms, predominantly Tik-Tok and had a relatively ambiguous platform. This included the establishment of a new socio-economic model based on sovereign-distributism, lowering energy costs, criticising the EU and NATO, and strengthening the state.

Before coming in to sweep the presidential race, Georgescu’s past was unknown to much of Romania’s population. He is a former member of AUR (The Alliance for the Unity of Romanians), the country’s far-right party that entered politics after the last parliamentary elections. His name was popularised as a potential nominee for the position of prime minister in 2011, 2012, and 2020—the last time on behalf of AUR—although the speculations never materialized into a nomination.

Building his support on being anti-system, Georgescu has been part of the same system he has vehemently criticised since the 1990s. An agronomic science graduate until the collapse of the communist regime, he went on ‘missions’ abroad both in the UK and US. This raises questions about his affiliation with the Communist Party in that time since it wasn‘t common to have such opportunities or ties with the West, without being a member. He denies any such affiliation.

At the core of Georgescu’s campaign is a strong feeling of antiglobalisation, although his CV shows that not only he was part of, but a very relevant actor in the institutions and NGOs that were aimed at bringing Romania on the european and global scene after two decades of communist diplomatic and economic isolationism.

So what made him so popular? His opponents have played an important part. Polls before the first round of the presidential elections didn’t include Georgescu among the top five candidates. However, they showed Marcel Ciolacu, the current SocialDemocrat Party prime-minister, present in almost all secondround predictions. George Simion - the president of the AUR ultra nationalist party - was also shown as most-likely to enter the second round. Although not as popular, the National Liberal Party candidate, Nicolae Ciucă also had an extensive campaign.

This mattered to voters for two reasons: they were once again since 1989 presented with options that did not represent them. They saw distanced politicians, constantly accused of corruption and hypocrisy, seemingly leading the country into a socio-economic crisis as long as EU funds were available for nepotism-based state contracts. To add to this, the fact that the opposition ‘patriotic’ candidate, Simion, previously seen as a potential saviour through his nationalist and populist discourse,

moderated his stances, hoping to appeal to as many voters as possible.

year Politics and International Studies, Romania

Despite all of this, after validating the first round, the Constitutional Court of the country decided a recount of all the votes, just one week before the second round, concerned by the impact of TikTok on Georgescu’s campaign and popularity. In the span of two months, he gained the views and reactions that all the main candidates accumulated together in 11 months.

How? A coordinated network of accounts (around 25.000 according to official records) directly promoted him. A large group of influencers that campaigned for an un-named candidate – ‘what traits should the next president have’ – used the same script, and the same adjectives that Georgescu uses to describe himself. The ‘stability & verticality‘ hashtag used in all such posts gained 2.4 million views.

Tik-Tok has a very strict policy on political campaigning, namely zero-tolerance aimed at depoliticizing the platform, but no frameworks in place to deal with unmarked political content.

Georgescu’s campaign was also called into question due to possible affiliations with the Kremlin, denied by both sides. However, a firm opponent of the war in Ukraine, often denying or offering justification for Russia’s actions, he has praised the leadership of Vladimir Putin which adds to the fact that the network of accounts linked with his popularity was connected to Russian propaganda outlet Sputnik.

With his political rise, and in the context of such popularity on a declared ‘zero-fund’ campaign, a national security council was also called by the current president, Klaus Iohannis. The documents presented in the meeting include intelligence reports showing multiple attempts by ‘foreign state and non-state’ actors to interfere in the electoral process. Analysis on russianled destabilization efforts through disinformation propaganda on NATO/US influence, current Romanian foreign policy and Romanian support for Ukraine have also been released.

This is the context due to which the elections were annulled by the country’s Constitutional Court, meaning that the second round was cancelled two days before voting. They now need to be reorganized from the beginning. Candidates will have to complete the sign-up and validation process again. The Court’s decision was motivated by the ‘clear and flagrant’ violation of the democratic process, the misinformation and manipulation of public opinion in the run-up to the elections, deeming it a necessary measure to protect the democratic regime.

Romania is left in a very unclear position with a new date to be set after the new government is formed, serious security concerns in a complex geopolitical environment and a deepened sociopolitical polarisation owed to falling trust in state institutions.

French politics hasn’t ever been known for its unity. More than ever, the French political scene has found itself splintered. Electoral alliances, personality complexes and last-minute deals have gripped the narrative of French politics throughout 2024. A disastrous snap election led sitting-duck President Macron fall from his perception as one of the most skilled political actors of his generation (being the first to win presidential re-election in 20 years) to an overinflated, overambitious elitist who failed to understand the country he governs.

The campaign, results and ensuing chaos of the 2024 snap legislative election have benefited one party more than most. The far-right populist National Rally is arguably the centrepiece of the French political narrative for the last seven years. It was against the National Rally’s Marine Le Pen that Macron won election and re-election to the presidency, and against whom he suffered defeats in both the 2024 EU and parliamentary elections. The National Rally (RN) now sits as the largest single party in the French National Assembly. Amidst a pressing austerity budget and unworkable political arithmetic, it would seem their chance to clinch the Presidency in 2027 is better than ever.

Yet not is all as it seems. Under the guise of anti-Macronism lies a key power battle that will undoubtedly define the next three years of French politics.

The French presidency remains one of the most powerful elected positions in the world. The scope and range of its powers across all three branches of government make it nothing short of mandatory for any political movement who seek to re-shape France, French politics or the French state.

Unity over presidential candidates is key. In 1981, Valéry Giscard d‘Estaing attributed his re-election defeat to the refusal of his rival Jacques Chirac to endorse him in the second round. He swore never to speak to Chirac again. Similarly, the failure of the left to agree on a candidate in 2002 led to Chirac being gifted a second term, with 82% of the vote.

Three-time presidential candidate and former party leader Marine Le Pen has been the favourite child of the far-right since 2011. Having inherited the RN leadership from her father Jean-Marie, the Le Pen family have been a stalwart of the French right since the 1980s. Le Pen has taken the party from a disgruntled radical-right organisation to a credible political force, culminating in her winning 41% of the presidential vote in 2022.

Despite the advances she has made in the last 14 years, Le Pen’s credible chance to run in 2027 is now anything but clear. Instead, the party stalwart faces a challenge from the new darling of the youth-right: Jordan Bardella.

“Under the guise of anti-Macronism lies a key power battle that will undoubtedly define the next three years of French politics.”

Evan Verpoest; 1st year History, London

Bardella is a compound of all that drives the populist wave in France. Born and raised in the banlieues of Paris, his underprivileged upbringing brings with it an anger that many French people feel at the political orthodoxy, neatly contrasting the Parisian elite that many feel typify the upper ranks of French politics — privately educated, grand écoles attendees who cut their teeth working in the La Defense private sector and growing up on the banks of the Seine, hopping nicely into various cushy government jobs. Macron is, unfortunately, no exception.

Bardella has enjoyed a meteoric rise through the RN ranks, elected to the European Parliament in 2019, the party’s vice presidency in 2021 and President in 2022 after Le Pen’s defeat in the presidential election. His rise culminated in widespread speculation that he could become Prime Minister amidst the 2024 legislative elections. His popularity is highest amongst urban and younger voters, to whom he makes the National Rally much more electable and personable. The success of the RN in the legislative elections is largely attributed to his charisma, messaging and political appeal. Hence, he is seen as a natural candidate for the presidency.

Yet Bardella’s rise is not the only thing that complicates Le Pen’s political future. Her implication in a criminal case accusing her of diverting EU funds to pay party assistants. Not only does said case have the potential to damage her politically, but a criminal conviction would legally bar her from running for the presidency in 2027. Bardella thus far has been coy about his intentions. Whilst he has stopped short of openly attacking Le Pen, he has made vague statements that have hardly strengthened her legal and political position.

With three years left in his term, the battle to replace Macron has already begun, and there is little chance that the reverberation of presidential ambition will die down quickly. French politics is anything but predictable. And whilst Bardella and Le Pen may

Like Magna Carta, the Treaty of Waitangi holds a mythic significance in the constitutional bedrock of New Zealand. A settlement between the Crown and Māori chiefs, the 1840 treaty enshrines the rights of British citizens to the Māori, including rights to property, fair trial, and freedom of religion in exchange for rights of government.

Since 1840, Māori landholdings have decreased significantly due to purchases, and confiscations. Deprivation is far higher in the Māori population with, as of 2018, 40% of the Māori population live in the two most deprived deciles, more than double the average.

Disproportionately deprived and socially conservative on contraception, Māori are more likely to have a greater number of children younger, meaning the median population age is far lower than the average. This combined increased ethnically mixed couples, the Māori-identifying population is forecast to grow significantly as a proportion of the population.

As signatories to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the courts and Treaty tribunal, the body that supervises adherence to the treaty, have historically chosen the Māori version of the treaty over the English one, meaning that under the modern interpretation by the law, the Māori chiefs ceded governance but not sovereignty, whereas the English version states all rights of government as under the Crown.

The bill was introduced in September by the right-libertarian party ACT under its leader, Minister for Regulation David Seymour, himself of mixed Māori heritage. The bill states the primacy of the English version, advocates for universal equality under the law, and that Māori rights are to be defined in the treaties and acts of parliament, rather than by precedent.

The bill has attracted critics, most memorably when the bill was torn up in parliament by Māori Party MP Hana-Rawhiti MaipiClarke, also of mixed Māori heritage, while performing the haka, for which she was suspended from the chamber. The main Hīkoi mō te Tiriti, March for the Treaty, had 42,000 attend in Wellington, and was led by the Māori Queen Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō, a practicing Catholic.

ACT has a history of opposition to special provisions. Don Brash, an ex-leader of ACT, founded Hobson’s Pledge, an antitreaty lobby, which advocates the removal of all references to the Treaty in law, and against affirmative action for Māori. In 2019 ACT published ‘One Treaty One Nation’, which called for the

abolition of Māori wards and seats, and the Waitangi tribunal, describing the Māori as being lifted out of “a violent stone age existence“.

The protests demonstrate the strength of feeling behind the changes to the legislation, but these are built on the theory that this is the first step down a slippery slope.

I can understand Seymour’s case against special Māori provisions. Seymour rightly points to the fact that 43.3% of people who identified as Māori also identified as European, and modern Māori culture is deeply linked to European Kiwis.

Through imperialist eyes, Māori seats were a masterstroke in colonial duplicity. A troublesome band of ‘savages’ legislatively ghettoised into a movement of protest, outflanked by enlightenment values. Four constitutionally accommodated dissenters out of eighty, sanctioned as Thatcher sanctioned Skinner, to rail against injustice, to give MPs something to chuckle about, and to consign justice to notions of grandeur allotted to the ignorant benches.

There can be no doubt that in the past, Māori seats gave a voice to the voiceless, but I see no practical benefit of Māori seats, because I cannot think of exclusive issues. If an employer discriminates against people of colour, will they for Indian kiwis? Show me the Māori cost of living crisis, the Māori housing crisis, if a bomb goes off in Wellington, is it a Māori national tragedy or a national tragedy? If China were to blockade New Zealand, how would it not affect Māori? How much in common does a destitute Māori truly have to one who was sent to Eton? Surely it’s less than a destitute kiwi of a slightly different ethnicity.

I don’t think constitutional reform is necessary. Upheaval of a national myth that promotes cooperation could have negative consequences, with the perception of rolling back Māori rights could inflame tensions. Māori seats may be unnecessary now, but as a piece of national heritage, like bishops in the Lords, they ought to remain.

The Bill will now have a six-month select committee stage before its second reading in June, where it is expected to fall. Should the bill become law, a referendum will be held. As of writing, polls show an even split.

The ACT is expected to fight the next general election on its constitutional reforms, to be called no later than December 2026. Parallels have been drawn to the Australian Indigenous Voice and Brexit, both of which saw a victory for the side supported by the populist right.

When you consider Russia’s malign involvement in internal state affairs, one’s mind naturally brings forth images of Russian tanks in Ukraine, bribery of Eastern (and increasingly Western) European politicians, or even its now ubiquitous massive foreign election interference via social media. Yet, one image that has left the spotlight over the last decade is their major involvement in the world‘s deadliest ongoing conflict – the Syrian Civil War, which has killed 400,000 and displaced millions since 2011. Recent developments however – notably the ousting of President Bashar Al-Assads’ regime– serve as sufficient glamour to drag the conflict and Russia’s involvement back into the limelight.

For most reading this article, the Syrian Civil War holds that uncomfortable position as being one of the most ‘normal’ events of our time. In the company of pandemics and populism, Brexit and BLM, the war was … habituated. Taught in school politics classes as an ongoing ramification of the broader Arab Spring, little care was given to the actual state of the war itself – or the possibility of its resolution. With both pro and anti-government forces contending not just with each other but with various Islamic extremist groups and Kurdish separatists in their state of Rojavia, by late 2014, government forces controlled just 25% of the country. Nearly 200,000 people had been killed, and nearly 4 million had been made refugees. Syria was designated a “failed state” – and the world moved on. No Western Kosovo-esque intervention appeared - even after the crossing of Obama’s “Red Lines”. The war looked to be that increasingly unique case of intra-state war that is resolved … internally.

Enter Vladimir Putin. On the 15th September 2015, the Russian Federation launched its own personal intervention, with its stated aim being ISIL forces working in the region. However, by 2016 80% of Russian aerial bombardment was against the very anti-government militias that ISIL was fighting. By 2017, the Russians had a “permanent” presence in-country, effectively granting pro-government forces total aerial supremacy for the foreseeable future. By 2020, several Russia-sponsored and government-friendly ceasefires had occurred and governmentcontrolled territory increased dramatically. Naturally, of course, Russia followed the imperialist playbook and got much in return for its ‘aid’. These include indefinite leases on Tartus Naval Port (satisfying that Russian obsession with ‘warm water ports’) and Hmeimim airport, as well as the blockage of the Qatar-Turkey Pipeline (ensuring Russia‘s monopoly on European gas). More broadly, the gall to and seeming success of a Russian intervention boosted perceptions of Russian power.

Whilst the West moved on, the Russians created a “stable” situation. Just one month ago, the majority of the country was controlled by Russian-backed government forces, with the only real fighting happening between Kurdish Rojavia (breakaway state) and Turkishbacked militias in the NE. Yet, on the 8th

Year, Politics and International Studies, Norfolk Virginia

December Assad threw in the towel as Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) led opposition forces stormed into Damascus, Hama, and Homs. In the space of just under two weeks, the status-quo and its Russian backers were overthrown. Commentators, stunned by the rapid change, point to the drain of the Russo-Ukrainian war and Israel’s various ongoing wars as exhausting Russian and Iranian will to support Assad. Regardless of the reason, there is now a more important question the world must ask – one that affects not just the 23 million in-country Syrians but the over 5 million refugees abroad. What next for Syria?

This is not an easy, or intrinsically hopeful question. Recent history has shown the toppling of a dictator does not lead automatically to peace – but rather to dangerous power vacuums. Look at Libya and Yemen. For Syria, a country racked by violent factionalism for over a decade, grievances are unimaginable, and retribution expected. Moreover, Turkey and Israel are all set to use this vacuum to push their own agendas – the destruction of Kurdish separatism and the annexation of the Golan Heights. This is all underpinned by the fact that the ‘liberating alliance’ is led by an Al-Qaeda-adjacent group, bringing with it the fears of Islamic fundamentalism. For many, Syria seems doomed to fall back into civil war.

Yet, despite all cynicism, hope can already be found. For one, look at real efforts the Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham-led opposition are making at reconciliation. Proclamations have already been made to many of the country‘s minority ethnic and religious groups promising pluralism, even one sent to Rojavia saying that “Diversity is our strength”. A blanket amnesty for soldiers of government forces – coming from a group that has a bloodied history of televised executions of enemy combatants – must be seen as a real effort to try for peace. These initial efforts are buoyed by a palpable euphoria from the populace at the downfall of Assad – scenes outside Saydnaya prison of freed prisoners show the appetite for further fighting is dwindling. Whilst we do not know yet how Syria will look in a month’s time – let alone a year – as one of these freed prisoners wrote “Forever is over, and history begins”. Syria has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rid itself of war, and

Making history on October 25, Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey was elected as the first Ghanaian and the first woman to lead the Commonwealth. With the imperial institution’s relevance dwindling on the global stage, Botcheway is faced with an opportunity to redefine and modernise the Commonwealth. Lobbying on a platform of climate resilience, realignment with democracy, economic transformation, and the creation of opportunities for the youth of member states, the prospect of reform seems ever closer. However, questions remain about whether these states are too diverse for the Commonwealth to survive in the modern day.

Historically, the Commonwealth has been incredibly powerful globally; from the pivotal role it played in decolonisation post-World War Two, to its promotion of trade and economic cooperation among former colonies. However, in a world veering towards nationalism, its future seems precarious. The rise in minilateralism has diverted attention from the Commonwealth as organisations such as the African Union, ASEAN, and the European Union have all become more central politically to their respective regions. Moreover, the decline of British power internationally also diminished the power held by the Commonwealth. Alongside this unfavourable political climate, there is the key issue of diversity among member states who have differing political systems, economic conditions, and priorities. As such, it is difficult to create conclusive, coherent policies that can be enacted across all (or even the majority) of the states within the institution. Whilst Botcheway’s appointment has raised the possibility of Africa’s needs and interests being brought to the forefront of the Commonwealth, these systemic issues present a real challenge to her endeavour to reinvent or retain the Commonwealth’s power in the first place.

However, if anyone has the foundation necessary to facilitate change, Botcheway’s credentials would put her at the top. To name a few, she chaired the council of ministers within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), navigated Ghana’s two-year tenure on the UN Security Council, and was fundamental in the passing of Resolution 27/19 (allowed for African Union-led peace operations to be funded by the UN).

Furthermore, the new secretary-general is clearly aware of the structural issues in the organisation. In an interview with the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Botcheway highlighted what she viewed to be the greatest challenge the Commonwealth is facing today– its ability to adapt in a fast-

Isabella Cottingham; 1st Year, Politics and International Studies, Hertfordshire

changing world in a way that benefits all of its members, with an emphasis on the way decisions affect its most vulnerable. She noted that it is crucial to revive the confidence and support of all its members for the Commonwealth Secretariat to be a “viable vehicle for transformation”.

Whilst the Commonwealth clearly needs to modernise institutionally, the future evidently holds strong leadership and ambitious goals under the new secretary-general.

Botchwey places an emphasis on achieving climate resilience–a reform essential for the future of several African nations. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, on average climate-related hazards cause African countries to lose 2% to 5% of their gross domestic product annually, with many diverting up to 9% of their budgets to respond to climate extremities. A transnational approach to tackling this issue would lower costs and mean economies across the Commonwealth could unlock vital financing, allowing them to reinvest in infrastructure and institutions.

She also aims to ensure “democratic resilience”, emphasising the importance of redefining the Commonwealth’s values to reflect a commitment to “democracy, peace, justice and human rights, and guarantee a high living standard for Commonwealth citizens”–to do this she suggests a stronger partnership between the Secretariat and the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. Moreover, as Chair of the ECOWAS Council of Ministers, she played an instrumental role in the prevention of coups in the region, and the reformation of the institution’s Supplementary Protocol of Democracy and Good Governance– a reflection of her capabilities in this area. The need for democracy resonates deeply with many citizens within African countries; this move reflects another attempt by Botchwey to prioritise African needs within the Commonwealth.

Ultimately it is clear that the imperial institution of the Commonwealth is dwindling in its relevance on the global scale and this could be its chance to redefine itself as an essential global leader. The profound diversity of its member states is in itself a double-edged sword. For all the challenges it creates, if Botcheway is able to unite the institution in a common agenda, then she may be able to craft a template that makes the Commonwealth fundamental to leadership in global political, economic, and environmental challenges experienced internationally. Success for the new secretary-general would implicitly impact Africa’s status as an actor in politics internationally, as well as giving the Commonwealth and its place in the world meaning, relevance and a direction for the future.

Kate

O’Mahony; year Politics and International Studies

Can they ever defeat the reign of MAGA?

Making history on October 25, Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey was elected as the first Ghanaian and the first woman to lead the Commonwealth. With the imperial institution’s relevance dwindling on the global stage, Botcheway is faced with an opportunity to redefine and modernise the Commonwealth. Lobbying on a platform of climate resilience, realignment with democracy, economic transformation, and the creation of opportunities for the youth of member states, the prospect of reform seems ever closer. However, questions remain about whether these states are too diverse for the Commonwealth to survive in the modern day.

Historically, the Commonwealth has been incredibly powerful globally; from the pivotal role it played in decolonisation post-World War Two, to its promotion of trade and economic cooperation among former colonies. However, in a world veering towards nationalism, its future seems precarious. The rise in minilateralism has diverted attention from the Commonwealth as organisations such as the African Union, ASEAN, and the European Union have all become more central politically to their respective regions. Moreover, the decline of British power internationally also diminished the power held by the Commonwealth. Alongside this unfavourable political climate, there is the key issue of diversity among member states who have differing political systems, economic conditions, and priorities. As such, it is difficult to create conclusive, coherent policies that can be enacted across all (or even the majority) of the states within the institution. Whilst Botcheway’s appointment has raised the possibility of Africa’s needs and interests being brought to the forefront of the Commonwealth, these systemic issues present a real challenge to her endeavour to reinvent or retain the Commonwealth’s power in the first place.

However, if anyone has the foundation necessary to facilitate change, Botcheway’s credentials would put her at the top. To name a few, she chaired the council of ministers within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), navigated Ghana’s two-year tenure on the UN Security Council, and was fundamental in the passing of Resolution 27/19 (allowed for African Union-led peace operations to be funded by the UN).

Furthermore, the new secretary-general is clearly aware of the structural issues in the organisation. In an interview with the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, Botcheway highlighted what she viewed to be the greatest challenge the

Commonwealth is facing today– its ability to adapt in a fastchanging world in a way that benefits all of its members, with an emphasis on the way decisions affect its most vulnerable. She noted that it is crucial to revive the confidence and support of all its members for the Commonwealth Secretariat to be a “viable vehicle for transformation”.

Whilst the Commonwealth clearly needs to modernise institutionally, the future evidently holds strong leadership and ambitious goals under the new secretary-general.

Botchwey places an emphasis on achieving climate resilience–a reform essential for the future of several African nations. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, on average climate-related hazards cause African countries to lose 2% to 5% of their gross domestic product annually, with many diverting up to 9% of their budgets to respond to climate extremities. A transnational approach to tackling this issue would lower costs and mean economies across the Commonwealth could unlock vital financing, allowing them to reinvest in infrastructure and institutions.

She also aims to ensure “democratic resilience”, emphasising the importance of redefining the Commonwealth’s values to reflect a commitment to “democracy, peace, justice and human rights, and guarantee a high living standard for Commonwealth citizens”–to do this she suggests a stronger partnership between the Secretariat and the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. Moreover, as Chair of the ECOWAS Council of Ministers, she played an instrumental role in the prevention of coups in the region, and the reformation of the institution’s Supplementary Protocol of Democracy and Good Governance– a reflection of her capabilities in this area. The need for democracy resonates deeply with many citizens within African countries; this move reflects another attempt by Botchwey to prioritise African needs within the Commonwealth.

Ultimately it is clear that the imperial institution of the Commonwealth is dwindling in its relevance on the global scale and this could be its chance to redefine itself as an essential global leader. The profound diversity of its member states is in itself a double-edged sword. For all the challenges it creates, if Botcheway is able to unite the institution in a common agenda, then she may be able to craft a template that makes the Commonwealth fundamental to leadership in global political, economic, and environmental challenges experienced internationally. Success for the new secretary-general would implicitly impact Africa’s status as an actor in politics internationally, as well as giving the Commonwealth and its place in the world meaning, relevance and a direction for the future.

Argentina’s President Javier Milei was the first world leader to meet with Donald Trump after his election. This was no coincidence. Under Milei´s leadership, Argentinian society has seen a marked shift toward aligning with Western, right-leaning democracies on economic and social aspects. Milei’s libertarian pro-market reforms, scepticism of climate change and DEI policies combined with fiery rhetoric, mirror Trump’s approach to governance. As the two leaders gradually shared their mutual ideological and governmental views on their friend´s libertarian platform, Elon Musk´s X, it appeared to be a match made in Friedman´s heaven. Nevertheless, this recent proximity also comes with challenges, both domestically within Argentina and in the broader international context.

Historically, the relationship between Argentina and the United States has moved in tandem with the political winds. During the mid-20th century, Argentina’s hard-left governments often clashed with U.S. administrations, particularly due to geopolitical and ideological differences, as Argentina pursued a non-aligned foreign policy during the Cold War and promoted a new form of hard-left populist Socialism known as Peronism. This led to the infamous Operation Condor in 1973, where US military and Intelligence services empowered the Argentine Military to stage a Coup successfully.

The 1990s saw a period of rapprochement, particularly under President Carlos Menem, who embraced neoliberal economic reforms and aligned Argentina’s foreign policy with Washington. However, in the 21st century, Argentina adopted populist and protectionist policies under Peronist Presidents Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, distancing itself gradually more from Western capitalist countries. More recently, Milei´s predecessor, Alberto Fernández, increased the Peronist populist machine to its maximum; erasing income taxes for 99% of the population, imposing substantial price freezes on basic supermarket goods, and printing pesos to finance government expenditure to the point of leading to 211% annualized inflation.

Under President Javier Milei, Argentina has made a significant pivot back towards neoliberalism and free markets. In his first months in office, he devalued the Argentine peso by 50%, removed energy subsidies and control price mechanisms, and laid off over 250,000 public sector employees and contractors. The shock therapy successfully tackled the country’s ballooning debt, soaring inflation, and chronic fiscal deficit, problems that have plagued Argentina for decades. This was met with both the public´s and financial markets‘ praise, a hard combination in Argentinian politics.

Enter Donald Trump. Among Milei’s supporters, many see Trump as a model for a strong neoliberal, pro-business, anti-

woke and anti-establishment leader. For them, stronger ties with the U.S., and specifically Trump, could unlock much-needed capital, technology, and expertise to help address its ongoing economic crisis. By prioritizing U.S. support, Milei plans to boost Argentina’s foreign reserves through an increased trade surplus in dollars which would enable him to dollarize the Argentine economy as he intends to eventually.

According to Zuban Cordoba, an Argentinian polling data consultancy, roughly 30% of Argentinians have positive views and 55% have negative views regarding Donald Trump. Still, listening to Milei speak, who has an approval rating of 52%, everything is so uncannily familiar to Trump: the brash persona, the radical proposals, the unapologetic ego. Most notably, both men are experts at successfully connecting to their electorate. They do not care about politically correct language or global problems such as climate change and DEI. They say they care only about improving Argentinians‘ and Americans‘ everyday lives, and that resonates with people.

Yet, many within Milei´s ranks, especially those previously close with the political establishment, disagree with the benefits of a Trump Presidency. Trump‘s protectionist and fiscal measures, which include imposing a global tariff of 10% to 20% on all imports to the US and borrowing to cover for his drastic reduction in corporate tax, inherently clash against Milei´s libertarian open markets policy and cost Argentina’s economy as an indebted commodities-oriented exporter. Doubling down on the increasingly inward-looking US is also seen as worrying, as Latin America is being continuously enticed by China, through its investment propositions in the region.

Nonetheless, opposing the US can also prove costly to anyone in Milei´s administration, as former Foreign Secretary Diana Mondino discovered in October, when she was fired and her foreign ministry “purged” for voting against the US embargo on Cuba.

Trump is definitely a valuable ally in the White House, potentially able to aid Argentina in negotiating better terms with the IMF, in increasing trade between both countries and in propelling the country to economic development. Milei´s and Trump´s general affinity also showcases how politicians increasingly foster relationships with countries that have an ideologically similar government leader rather than an inherently strategic partner. Yet, with so many domestic polarisation problems and conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, Trump could sideline the US´ relationship with Argentina. Ultimately, only time will tell if Milei´s bet on his prized Trump card will truly turn the game in Argentina’s favour.

Lily Hatch; 1st year Politics and International Studies, Windsor

The call for Scottish independence has been around since the beginning of the 19th century. While efforts to devolve powers from Westminster to the Scottish Parliament have been a significant step forward, many Scottish nationalists argue that these measures fall short of the independence they envisioned for their country; thus, Scotland‘s exit from the union appeared to be a natural progression. However, in recent years, the enthusiasm for nationalism among the Scots has waned, with the popularity of the SNP declining in tandem. The Scottish National Party (SNP), once the driving force behind the independence movement, in recent years has seen its popularity decline with leadership controversies, and an overemphasis on the independence agenda overshadowing other vital policy concerns – such as the NHS and rising drug death records. With this in mind, the future of the SNP is looking dimmer and dimmer; with the raging fire of Scottish independence fizzling out also.

In recent history, the campaign showed signs of at last becoming a success, however, in reality, it made little way of actual change. The 2014 Scottish independence referendum, in which members of the electorate were asked whether or not they would like to leave the Union, reflected this. While the SNP looked excitedly towards opinion polls, which suggested that their ‘Yes campaign’ would take to rain success, the actual outcome was much different. With 55% voting to remain within the UK, the SNP – amongst other Scottish nationalists –saw their first major hit to the independence movement. Moreover, whilst nationalists remained in disillusioned hope for an increase in support for their campaign over the years post-referendum, statistics once again proved them to be wrong. Opinion polls taken annually show that from 2014 up to 2024, not once have the majority of the Scottish public expressed a desire for Scotland to become an independent country. Thus, showing that there has never been

As a result of this, many were surprised when the notion of ‘IndyRef2’ (a second Scottish Independence referendum) was introduced by former SNP leader, Nicola Sturgeon; following the UK’s vote in favour of Brexit. But once again, independence plans were faced with yet another hurdle. A Supreme Court case debating the legitimacy of Scotland‘s legal ability to call a second referendum, ultimately ruled that under Scottish laws created in 1999, they did not have the power to legislate on areas of the constitution – including the union between England and Scotland. Although it would be possible for Scotland to appeal their case to the European Court of Human Rights, it appears as though any plans for a second independence referendum have been quashed for the foreseeable future.

Similarly, the once bright future of the Scottish National Party has also dwindled in recent years. The demise of the oncedominant party can be attributed to many factors, most notably – poor leadership. Across recent years, the party has seen many faces hold the position of party leader, yet one after another, scandal and failure have brought mammoth losses to the party. Two years ago, a scandal revolving around former SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon and her husband, ex-party chief, Peter Murrel, brought shame to the party. The pair were arrested for financial impropriety, with Murrel being charged with embezzlement of SNP funds, while Sturgeon, although released without charge, remains under investigation. As the modern face of the independence movement, the attack on Sturgeon’s image eroded trust in the party, as well as its pursuit of Scottish independence. Following on from this, Sturgeon‘s successor Humza Yousaf, stepped down following a humiliating loss in a vote of no confidence amongst his party. Furthermore, more recently, current leader John Swinney oversaw a mortifying general election result, securing just 9 of the 57 seats available to Scotland in Westminster (which pales in comparison to their 2015 general election result of 54 out of 59 seats) – undeniably representing the shortcomings of the SNP today.

With all this said, it is apparent that the future of both the SNP and the independence movement is not bright. With Scotland‘s major nationalist party suffering from a severe lack of trust and, as a result, a severe lack of seats in parliament – there is very little hope for Scotland’s exit from the United Kingdom. Neither Conservative nor Labour governments are willing to even discuss the notion of allowing Scotland to hold their ‘IndyRef2’. Alongside the SNP’s record-breaking low number of seats in Westminster, the nationalist party can make only very minimal efforts to debate the sanctioning of a Second Referendum. Without a clear vision for the future of Scottish independence nor widespread public support, Scotland’s push for ‘freedom’ is unlikely to pose a significant threat to the Union in the near future.

In PAIS we value your feedback; we know this is a challenging time and we want to do all we can to support you to succeed. Based on your ideas, we have put together an exciting agenda of events, activities and opportunities this term and beyond - please check our emails, social media and webpages for more details.

Academic support for students is a top priority for PAIS so please:

-Sign up for our Virtual Common Room chats on a range of topics including essay wrtiting, wellbeing and the liberated curriculum.

-Benefit form our online workshops on essay writing for second years and finalists.

-Benefit from our online workshops on preparing for your online open book exams.

In response to your feedback, we have put together detailed online guides on making your study choices, including whith modules to takes, which assessment methods to choose and advice on applying to postgraduate study.

We want to hear from you and have a number of opportunities for you to feed-back on your course throughout the year including via your Course Reps and our end-ofyear module evaluation surveys. There is also the National Student Survey (NSS) which will open for finalists on Monday, 8th February -we would love you to complete it!

Following your feedback, we are running an Employability Series with a number of exciting speakers from a range of careers speaking at events this term. Details will be shared shortly.

Embed yourself in the PAIS research culture and ettend our Wednesday Research Seminar Series which is open to all PAIS staff and students. Finalists are also encouraged to join the Burning Issues: Geopolitics Today MA lecture series which focuses on contemporary world politics.

Follow Us on Social Media to find out more: www.twitter.com/PAISUndergrad www.facebook.com/paiswarwick www.instagram.com/paiswarwick

A book review of Yanis Varoufakis’ Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism

Technology conglomerates are becoming modern-day feudal overlords and we are all doomed to be slaves to Elon Musk and his pals; at least thats the prognosis presented in Yanis Varoufakis’ Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. With arguably far too many words and anecdotes, a self-proclaimed dancer around the point, Varoufakis explains the transitional state that we are currently in, away from the capitalist system that we are so used to and towards techno feudalism.

As we move deeper and deeper into an age of intense technological development, Varoufakis sees global structures and the way that hierarchies exist changing. The power of tech companies is essentially growing exponentially, with many becoming more powerful than governments, reshaping the way that markets exist and the way we exist within them. To help explain how we are reaching this point of metamorphosis, Varoufakis outlines the journey that capitalism has already taken, with, naturally, reference to Star Trek and Mad Men to aid his explanation.

The transition, he explains, has been slow and capitalism has died ‘not with a bang but with a whimper’. This restructuring was induced by neoliberalism – the economic ‘it girl’ of the late 1900s – with lax regulations and decreased state control concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a few and waving goodbye to the competitive markets from which capitalism thrives.

The rise of big tech platforms, Varoufakis argues, has hamstrung the market system; no longer able to function freely, instead, controlled by companies like Amazon, Google, and Meta. They are flooding markets from every angle to control them from above as digital feudal lords. Take Amazon, one of the largest

global marketplaces. Not only do they control the sellers, but they also operate as the largest seller in the marketplace, essentially driving their own success.

Google operates in a similar way, as a primary search engine it controls what information can be accessed or hidden. Varoufakis warns these platforms are essentially acting as unregulated monopolistic powers, out of the reach of government control, and pose a threat to our democratic systems, as well as further entrenching inequalities by placing increasingly large amounts of wealth in the hands of a small group of elites.