THE NEW SPACE RACE UNVEILED: A COSMIC POWER STRUGGLE IN THE 21ST CENTURY

RWANDA: DEMOCRACY IS AT RISK OF DISAPPEARING

3print editions, almost 30 podcast episodes and over 100 articles later I cannot believe we’ve come to the end of our time as the Perspectives team. This edition is especially exciting as we’re experiencing one of the most significant election years in history, with more than 64 countries who combinedly represent almost half of the world’s population either having already taken to the polls or gearing up to do so in the coming months. Drawing this election theme throughout the edition, our writers tackle critical electoral issues from border disputes to farmer protests to rises in nationalism. Yet we may be taking democracy itself for granted, as we see corrupt elections rife across the world, such as the article tackling Rwanda as a well-camouflaged dictatorship. In such a momentous election year, we are of course drawn to reconsider how democratic the world we live in actually is. In a brilliant feature, you’re taken through the trajectory of some of this year’s most major elections, as well as the realisation that democracy may not be working as well as we’d hoped, though this doesn’t mean an uphaul on democracy itself. Coming back to our own doorstep, the For and Against presents a great portrayal of our very own democratic system – the SU – and whether it is actually democratic, having recently seen controversial All Student Votes and amendments.

Now having officially said the words ‘election’ and ‘democracy’ too many times, an election year doesn’t call for us to ignore every other major global issue; if anything, elections encourage us to consider what issues matter to us even more than before, as we hope to elect leaders that embody (at least some) of our values. Amongst two major conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, both our UK and Europe articles have a military focus, from the downfall

As all of these elections probe us to reflect on our democratic systems, you may also be brought to consider if there are any other solutions. Our Oceania article tackles just this, exploring the idea of benevolent dictatorships in the continent with a Lee Kuan Yew style of rule. While every country won’t swing to benevolent dictatorship, the rise of corruption and coups across the world in Africa brought about the increasing prominence of the African Union, where one of our articles explores the actual usefulness of the Union.

of our own military to the continent’s rearmament aims and whether they can or should do so. This edition also reflects on the past and looks to the future, from the evolution of the US’ role in the Middle East 35 years after Desert Shield, to the modern Space Race, with Asian countries potentially standing to become the new USSR.

The past year has also especially shown us that the political isn’t just politics. Taylor Swift’s global rise to power puts her in a position to be marvelled at, from the influence she holds over politics as a music

artist to a tight legion of fans that could likely elect her president should she run. Across the pond, the insider portrayal of the elite British upper-class in Saltburn is unpacked in our film review, following a new angle on class dynamics that strays from the classic ‘eat the rich’ tale. Staying in the UK, the book review is a great retrospective of the last 14 years of the Conservative government ahead of the election that could break this streak (of course I had to throw in the word election once more).

Bringing me to the end of my letter, all I have left to say now are the thank yous. First and foremost, the biggest thank you goes to the incredible Perspectives team. Rania, Will, Mathieu and Tom, you have been the best deputy editors I could have asked for and this magazine would not be nearly as interesting and insightful without you. Jesse and Zak, you are honestly the coolest design editors ever; from the uphaul of the Instagram and website, to the complete revamp of the print editions, the magazine has levelled up and taken on an entirely new form because of you and I’m sure everyone who is reading this agrees it looks incredible. To all of our incredible writers, both featured in this and previous prints as well as online, and to everyone who has come on Beyond the Page, Perspectives would of course be nothing without you, and it’s been an honour for us to publish such nuanced, diverse and engaging perspectives. And finally, to you, the reader, I hope you enjoy this edition as much as we enjoyed creating it! And of course, in keeping with the edition theme, make sure you vote in any election you’re eligible for – hopefully this magazine has convinced you that your perspective matters.

Perspectives goes to print once a term, whilst our online edition is updated weekly to give us students a chance to have our voices heard.

We also have a radio show, which is then uploaded as a podcast, where we hold weekly discussions to discuss pertinent political issues. We will be inviting interested writers/ podcasters on board!

@warwickperspectives

@Perspectives

@Perspectives Writers

@PerspectivesUoW

@PerspectivesMagazine

Profile: Taylor Swift

By Devina SinghJolted into life: How EU policymakers are finally waking up to the imperatives of rearmament

By James BeamishFrom masjid to mandir: Ayodhya’s political aftermath

By Rania Sivaraj2024 elections: the biggest year for democracy

By Jamie MutchThe authoritarian creation of a radiant tomorrow: applying Lee Kuan Yew’s benevolent dictatorship to Oceania

By Yusuf Khalid

A ‘Cold-Civil War’?: Texas faces off with Uncle Sam

By Tom LoweIs the African Union worth the hassle?

By Raphael HammondHow a relationship spawned out of warfare led to almost immediate collaboration with Kuwait - the tale of US intervention and opportunism in the Middle East

By Taylor GreenThe New Space Race unveiled: a cosmic power struggle in the 21st century

By Kate O’MahonyA wake up call for a post-war generation

By Kara EvansThe 2024 Venezuelan election: from humanitarian crises to border conflict

By Taran DhillonThe War on Farmers is a byproduct of the revolt against globalism

By Ethan Harvey ByDEMOCRACY

2024 elections: the biggest year for democracy

20

BOOK REVIEW

A meticulous examination of Britain’s decline and who’s responsible

A Book Review of James O’Brien’s ‘How They Broke Britain’ By

Ben Tanguay Brown

FILM REVIEW

Welcome to Saltburn: A masterpiece on British class commentary?

A Film Review of Emerald Fennell’s ‘Saltburn’

By Milly OwenTAYLOR SWIFT

How does a pop star become Time’s Woman of the year?

22

IS THE WARWICK SU DEMOCRATIC?

Warwick’s Student Union: democratic by design

By Ben AlthenFOR AGAINST

Democracy in crisis: unpacking Warwick SU’s plant-based menus decision

Louis Samarasinghe“Her trajectory into becoming a household name all over the globe has been unprecedented”

Taylor Swift is arguably the most famous person in the world. Her trajectory into becoming a household name all over the globe has been unprecedented, aided by chart-topping albums and the viral, sold out Eras tour.

At 34 years old, Swift has spent over half her life in the public eye. Consequently, she has been the subject of much scrutiny. Did she write this song about that person? Did she paint her nails black to tease reputation (Taylor’s Version)? Despite all this, Swift’s involvement with politics (at least in the public lens) was first witnessed in her 2020 documentary,

“Swift’s influence is unparalleled, especially when compared to any other public figure today, even in the realm of politics.”

‘Miss Americana’. The documentary presented Swift’s decision to be open about her political views, from LGBTQIA+ allyship to voting.

have gone to great lengths to welcome her - from Rio de Janeiro projecting the junior jewels T-Shirt onto the Christ the Redeemer statue, to Glendale (Arizona, USA) changing its name to Swift City in her honour. Not many artists can boast of the fact that Heads of State have asked them to tour in their country, but Swift can. In 2023, Chilean President Gabriel Boric mentioned that he wrote to her asking her to come to Chile.

Art is rarely apolitical. To what extent is it acceptable for artists to also be apolitical? One of the most interesting aspects of Swift’s participation in politics, ironically, is her resounding silence. Considering how ‘Miss Americana’ represented the process of her being more outspoken about her beliefs (in a very dramatic fashion), many have pointed out that her ‘idea’ of politics is rooted in ‘white’, liberal feminism. When she chooses to express her views about politics, they are typically one of two things. The first dealing with misogyny, through songs such as ‘The Man’ (“I’m so sick of running as fast as I can, wondering if I’d get there quicker if I were a man”), ‘Mad Woman’ (“And women like hunting witches too”), and ‘Lavender Haze’ (“All they keep asking me is if I’m going to be your bride”). The second expression is her encouraging her (American) fan base to vote.

For the entirety of my time at Uni, I have been on the exec of the Taylor Swift Society (more affectionately, SwiftSoc). An advantage of this is being able to witness, close up, just how powerful she is. There are both pros and cons to this. The pros being the fact that her music has created a really close knit (yet massive) community, and the cons being that she is often treated as a golden, un-criticisable figure that is incapable of wrongdoing. Measuring her on a political scale is hard, considering that even the President of the United States can’t say he has a following so very protective in nature.

“many believe that Swift has the ability to sway policy decisions”

In December 2023, Swift was named Times Magazine’s Person of the Year. This decision did not go without backlash. Why pick a musi cian when there are so many people risking their lives everyday? Whilst there is so much weight to this argument, calling Taylor Swift just a musician is reductionist. Swift’s influence is unparalleled, es pecially when compared to any other public figure today, even in the realm of politics. Recent reports of the Bid en campaign hoping to gain her en dorsement shows just how important she is. The cities that Swift has toured in throughout her coveted Eras tour

However, issues such as her private jet emissions, or her association with two sexual offenders (albeit through her friends) are primarily brushed under the rug. Although I will not say that her jet emissions are justifiable, her decision to use a private jet is. Lately, it has been her silence on Gaza that has gotten her flak - many believe that Swift has the ability to sway policy decisions, and by choosing to not use her platform in an intersectional way, she is effectively causing harm. To argue that celebrities should simply stay out of it is not something I agree with. Her hesitation to be political, however, is understandable. Swift toes a delicate line. Her politics, like any other person, has been dictated by her own experiences. Simply being honest could, in fact, be self-destructive for her.

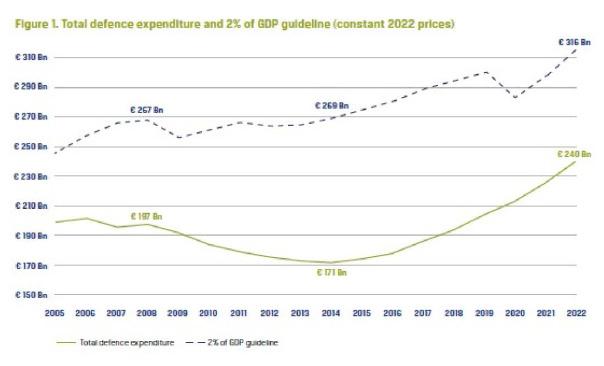

By Devina Singh, a 3rd year History and Politics student from Delhi, India.Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Europe seemed to slip into a state of perpetual lethargy. People partied amidst the rubble of the Berlin Wall, whilst Francis Fukuyama, writing in 1992, declared ‘the end of history’ to be nigh as the final ideological enemy of liberal democracy slipped beneath the crushing waves of jubilation. Like Joshua before the walls of Jericho, it was not force of arms which triumphed in this battle but rather righteous trumpets blasting sounds of liberty and democracy.

What this idealistic narrative ignores, however, is the role which concrete military power played in the downfall of Soviet Russia. It was largely American military might which halted the westward spread of communism in the first decades of the Cold War, while it was also, to a large extent, American investment in weapons development which provoked Soviet fiscal collapse in the late 1980s.

Now, these warnings should be taken seriously, and used as impetus to spark a greater focus on Europe’s defence capabilities. No matter who the President will be come 2025, Europe can no longer simply rely on Uncle Sam to come to its aid when it cries for help. Europe must grow up and learn to look after itself.

Specifically, two things must happen for Europe to better equip itself in this increasingly unstable geopolitical context. Positive progress is being made on both of these issues, though more must be done to make up for years of inaction.

only 18 percent of defence investment is done in cooperation with other EU countries. Most recently, this has caused the EU to drastically undershoot its munitions commitments to Ukraine, where less than a third of the promised one million rounds of artillery ammunition have been delivered.

It is therefore vital that the EU reforms regulations around defence, particularly regarding antitrust, to enable greater defence cooperation. It is also imperative that Europe puts its money where its mouth is and invests in joint procurement programmes.

Only now are European lawmakers waking up to this fact. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has jolted European politicians into life, while renewed conflict in the Middle East and threats to shipping in the Red Sea are highlighting the world order’s exit from the long period of stability which followed the conclusion of the Cold War.

In addition, as the US pivots towards China and the South Pacific, European security is bound to take a back seat in their strategic thinking. Typical of European bureaucratic hubris, EU policymakers only ridiculed and laughed at President Trump as he warned of European over-reliance on Russian energy and criticised EU underinvestment in defence, even threatening to withdraw from NATO.

Firstly, increases in military spending amongst EU member states is vital. Currently, only Greece is committed to NATO’s defence spending target of 2 percent, indicative of woeful underspending in the bloc for many years. Though it is true that EU defence spending has increased since Russia’s first incursion into Ukraine in 2014, average spending across the bloc remains at only 1.5 percent of GDP. It is estimated that an additional €76bn is necessary to make up for the shortfall and bring defence spending in line with NATO expectations.

Secondly, European powers must assess how money is being spent, not merely how much. Europe’s defence industrial capacity is underdeveloped and fragmented, causing vast inefficiencies in procurement and production. Currently,

Progress is being made here.

In a recent speech before the European Defence Agency, President Charles Michel of the European Council declared that “we must be more coherent, we must be more effective”, and proposed the creation of a “true defence single market”. Programmes such as the European Defence Reinforcement Through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) have been established to encourage co-operation, though only with a budget of €500m. Meanwhile the European Defence Fund has a budget of €7.9bn to invest in defence R&D, though even this is less than the €15bn proposed.

In an increasingly unstable world, it is thus vital that Europe steps up to the plate. There are signs that the beast is awakening, though progress to full enlightenment remains only partial. It is perhaps Robert Schuman, former Prime Minister of France, who put it best: “Europe will not be made all at once, but it will be made”.

By James Beamish, a 3rd year History and Politics student from St Neots, UK.

Along Hindu nationalist campaign concluded on 22 January. Narendra Modi inaugurated the incomplete Ram Mandir to thousands of devotees, proclaiming that “after years of struggle and countless sacrifices, Lord Ram has arrived”. This sprawling temple complex has cost $217 million to build so far on a 70-acre plot, and represents the volatile anti-Muslim sentiment and iconoclasm fostered by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for over thirty years.

1980s. Yet this movement was also what catapulted the BJP into political prominence in the 1990s. By acting as the Vishva Hindu Parishad’s political mouthpiece, the BJP were aligned firmly with Hindutva – the political ideology that follows Hindu nationalism and hegemony. This temple-building movement has thus been realised in Ram Mandir and its 70 acres, as well as the BJP’s sweeping results in general elections.

done very well, winning the 2014 and 2019 elections; in the latter, they won 303 seats out of 543 whilst the INC won 52. Modi’s approval ratings have been consistently high throughout his premiership, and in a 2023 poll 61% of participants favoured him over any alternative.

Ram Mandir’s history is a tumultuous one. Built in the city of Ayodhya – birthplace and home of the Hindu deity Ram –its existence is a physical manifestation of the devotion that surrounds Ram’s life and victories. Yet it is also a monument to other means of victory: that of Hindu nationalist attackers over Muslim places of worship. The mandir has been built on the ruins of the Babri Masjid, a Mughal-era mosque that had stood for almost 400 years until its destruction by protestors in 1992. Muslims in the community remember the day of Babri Masjid’s destruction as one marked by violence and terror; the weeks, months and years that followed were plagued with Hindu-Muslim riots.

The destruction and replacement of Babri Masjid is part of a wider phenomenon: the attempt to redefine India as a Hindu country for political gain. The masjid was destroyed by the Vishva Hindu Parishad, an independent right-wing Hindu organisation that had campaigned for a temple to be constructed on the site since the

Perhaps then it is clear as to why Narendra Modi has led inauguration ceremonies at the temple despite it being incomplete. On 5 August 2020, Modi performed the groundbreaking ceremony and served as chief of rituals for the event by performing the temple’s consecration on 22 January this year. Political commentators have lambasted this decision, stating that consecration should only be done by priests, and the premature celebrations sparked critique and confusion as the temple will only be completed by the end of 2024. Yet by harnessing the beliefs of the majority, quashing their fears of Muslim expression and commemorating Hindu hegemony, Modi is effectively capitalising the temple for votes as a general election is imminent, planned for April 2024.

The largest democracy in the world will elect 543 members of the Lok Sabha (the lower house of India’s parliament)

The politicisation of Ram Mandir through Modi’s involvement validates his and the BJP’s status as a pro-Hindu beacon, and the premature inauguration ensures that the memory is prominent in the voter’s minds. The involvement of the BJP in Babri Masjid’s destruction is echoed in the mandir’s building and consecration, galvanising the vote of India’s 80% Hindu population and ensuring what will most likely be a sweep in April against the INC. The INC’s commitment to secularism is easily dwarfed by the ceaseless ideology of the BJP and its nurturing of Hindutva.

The aftermath of Ram Mandir is already evident. Indian courts are considering demolishing more mosques and replacing them in temples in various cities such as Varanasi. Thousands flocked to the inauguration on the 22nd, and the Indian government plans to invest over $3 billion into Ayodhya to make it an attraction for devotees and tourists. The flames of Hindutva have been well and truly stoked in this erasure of India’s Muslim past - one with ramifications that will persist for years to come. Despite its incomplete state, the Ram Mandir will be a catalyst for the BJP’s imminent win in April and

By Rania Sivaraj, a 2nd year History and Politics student from Warrington, UK.

By Rania Sivaraj, a 2nd year History and Politics student from Warrington, UK.

If you look for it, I have a sneaking suspicion… elections actually are all around. From Indonesia to Iceland, Mexico to Madagascar. In 2024,

Trump presidency would be a disaster for the West and all we hold dear. He will almost certainly pull the plug on military aid to Ukraine - that is, if he doesn’t end

not the result China was looking for. In the run-up to the election, the Chinese government framed Lai as a “hoodlum”, a “liar”, and someone who would lead his people to war. But in staunch defiance of this view, the people of Taiwan have spoken and stood up for democracy in the face of authoritarianism. This is a positive and refreshing result the West should celebrate. Our support for Taiwanese autonomy should be resolute, if not for the principles of democracy then, with the island being a large producer of valuable semiconductor chips, for economic

This brings me, of course, to the biggest counter-balance to China in the region: India. The biggest democracy on Earth will once again earn said title during legislative elections expected in April/May. This will come at a time when Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party have been ramping up expressions of Hindu nationalism, threatening India’s proud existence as a secular state. In January, Modi stirred up controversy by opening a Hindu temple on the site of a 450-year-old mosque which had been destroyed by a violent Hindu mob in 1992. Beneath the obvious religious devotion of the ceremony lay a political statement - Modi is the candidate for Hinduism. It’s acts such as this which demonstrates Modi’s vision for a new India, one that is increasingly unsettling its Muslim minority and one likely to be entrenched at the polls.

Across the border, in Pakistan, elections to the National Assembly have been rocked by the surprising success of jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan and his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). Faced with extensive election inference, including having to run individually as independents, PTI-affiliated candidates have won more seats than any other party in the legislature. This has come as a great upset for the military establishment in Pakistan which exerts great po

litical influence. Khan was once the military’s golden boy, but following his criticism of their influence in Pakistani politics, was toppled from power and sentenced to a combined 24 years in prison in January. It was intended another former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and leader of the Muslim League, would once again become PM following February’s election, but his route to doing so has now become far more complicated. Both the PTI’s support and electoral ingenuity were underestimated. In an intriguing display of how artificial intelligence may come to play a role in other elections this year, the PTI utilised an AI hotline employing Imran Khan’s own voice in order to instruct supporters how and who to vote for in their constituency. The hotline was thus capable of circumnavigating the removal of the PTI’s logo on ballot papers. In the face of such a miscalculation and with no energy given to the thought of allowing Khan to rule, there may come a time in the near future where the military decides a democratic government is no longer feasible. The result of this year’s election, therefore, brings a significant chance of a revolutionary moment in Pakistan, a nuclear-armed nation with volatile borders.

de -

mocracy isn’t working.

“...in this year of elections it is important for us to remember that democracy cannot work in isolation from the people it is supposed to serve.”

Now, you might be thinking to yourself: this all seems a bit doom and gloom. Behind the headline - the biggest year for democracy - lies the rather bleak reality that

Elections certainly aren’t guaranteeing democ- racy. Of the 43 countries expected to hold free and fair elections this year, 28 don’t even meet the requirements of a democratic vote, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit. In Africa, the continent experiencing the most elections this year, support for democracy has rapidly declined over the past decade. This includes a 20 point drop in support for elections in South Africa, according to a poll by Afrobarometer, which has been home to a relatively stable democratic system since the end of apartheid. What on earth is going wrong?

In places like Pakistan and sub-Saharan Africa, democracy and elections have become compatible with corrupt governments, human rights abuses and militarism. As such, civilian populations have become fed up with the promise of democratic dividends that have never been

delivered. The trend of failed governments, rigged elections, and coups d’etat in the developing world can be blamed, I suppose, on the unsustainable and flawed nature of young democracies. Growing pains if you will. But the same anti-democratic sentiment can be felt across the Western world too. A study by Open Society Foundations in 2023 found that a third of young people in the UK aged between 18-35 thought a dictatorship was a good idea. The same study found that only 29% of Americans believed national politicians had their interests at heart. Hundreds of years of maturing democracy, increasingly energetic and informed populations, politicians who mostly come from reasonably impressive backgrounds and professions, yet there is a deep sense of disappointment in the final result.

The answer is not to blame democracy. Rather in this year of elections it is important for us to remember that democracy cannot work in isolation from the people it is supposed to serve. Rather than give up on democracy all together we should do the opposite. Double down our commitment to a system that requires the support of its citizens as much as its politicians. Sir Winston Churchill once said “democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”. It is easy to criticise democracy. It is easy to enjoy the irony that the most ‘democratic’ year will be largely undemocratic. But trying to find a system as free, fair, and dignifying, is impossible.

By Jamie Mutch, a 1st year Politics student from Northampton.In a 1994 interview with Canadian academic Michael Ignatieff, famed British historian Eric Hobsbawm uttered a very controversial statement. Having previously discussed that history decreed the Second World War was necessary, despite the death toll, Hobsbawm was asked by Ignatieff if Stalin’s purges may have been justified had ‘the radiant tomorrow been created’. To this, he replied simply - “Yes, this is exactly what people said about WW1 and WW2”.

The thought-experiment posed by the interviewer and interviewee here relays in my mind as I consider the view of ‘benevolent dictatorship’. The belief in an authoritarian ruler who exercises their power for the benefit of their people over self-interest, whilst desirable, seems fantastical and riddled in a moral tangle between otherwise objectionable means for increasingly desirable ends. The case study of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first Prime Minister from 1959-1990, thus poses a challenge for me.

Presiding over an apparent economic miracle (at the cost of human rights, according to his harshest opponents), Yew has been lavishly praised by Western politicians, from Henry Kissinger to Tony Blair, who have all sought to emulate his success story. The question of whether benevolent dictatorship should be applied to other small Oceanic countries is thus a fascinating one, and yet I shall reply more bluntly than Hobsbawm - unequivocally not.

Unlike Stalin, Lee Kuan Yew never killed anyone. Instead, his rule operated on a foundation of crackdowns against supposed threats and interference, under the country’s Internal Security Act. This featured encroachments on various civil liberties, from freedom of speech to micro-managed fertility policies.

The creation of a ‘radiant tomorrow’ however is not a falsehood, and can be seen today in Singapore’s subsequent transformation from fishing village to the 21st century metropolis it is today. Yew’s pragmatism in combining unregulated free market cap italism with generous welfare policies have yielded ben efits that have altered the country of Singapore beyond recognition.

After its formal independence in 1965 from Malaysia, Yew inherited an undeveloped nation with little natural resources and a half-literate multi-racial population subject to frequent race riots. By the time he left office in 1990, the country’s GDP per capita had skyrocketed, from just over $500 in 1965 to almost $12,000, whilst policies encouraging literacy and multi-racialism have resulted in an educated and uniformly integrated English-speaking population who exist in near harmony with one another.

Looking across the wider region at Oceanic countries beset by ethnic tensions and less-developed economies, the prospect of Lee Kuan Yew’s style of rule seems like an attractive prospect.

This is especially pertinent in the Pacific region, as we can recognise similarities to an early Singapore in countries such as Papua New Guinea. Boasting over 800 languages and 1,000 distinct ethnic groups in what is one of the most diverse countries in the world, Papua New Guinea is also punctuated by an estimated 40% of the population living below the extreme poverty line; the current state of the country is saddening to say the least. Particularly, land disputes in the Highlands region of the country from 2021 onwards have resulted in both massacres and division along tribal lines, laying waste to residential areas and causing great loss of both life and prosperity.

Yet, the trouble with the theory of benevolent dictatorship seems rooted very simply in its own essential nature - it is often only theoretical.

For while we all desire a Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore’s resulting socio-economic miracle, the bestowal of such power and elevation of a politician is much more likely to create a Stalin-esque dictator, with all of the associated atrocities (such as mass purges and executions). Whilst my conversations with Singaporeans have revealed their gratitude to their benevolent dictator, they acknowledge the sheer luck that Yew was the person who led them. Had it been only a self-interested dictator without any benevolence, the prosperity Singapore enjoys may not exist today.

Furthermore, a persistent problem in Singapore and any subsequent theory of application to other Oceanic countries would be the institutional legacy a benevolent dictatorship creates. Whilst perhaps necessary in developing a poor country, the resulting prosperity would create a new generation whose desire for greater democracy would clash against an elite comfortable with the status quo.

For while a ‘radiant tomorrow’ can always be created, relying on a dictator’s benevolence to do so is far from the safest option.

By Yusuf Khalid, a 2nd year History and Politics

In a bid to curb immigration from the southern border, and in direct defiance of a Supreme Court ruling, Texas has continued putting up a razor-wire fence that extends over 30 miles along the banks of the Rio Grande, leaving many migrants injured. Three people are confirmed to have drowned at the border following the Texan Military Department’s barring of US border officials rescue efforts. The United States now stands on the precipice of removing the ‘United’ from its name, whilst The Lone Star State is certainly living up to its nickname.

This is an unprecedented turn of events. Not since the Civil War (1861-65) has a state shown such open defiance of the federal government, with Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton consistently refusing federal access to the border. Governor Greg Abbott is playing an unconstitu tional game of chicken with President Joe Biden. If Biden does not act, he gives de facto legitimacy to Texas to just ignore federal orders, yet if he does act, he risks aggravating an already incredibly tense situation.

So… what happens now? Twenty five states with Republican governors have signed a statement backing Governor Abbott, citing Texas’ right to defend itself as justification for violating the authority of the federal government. Partisan divi sions in the US are coalescing around this issue, and whilst no material support has been pledged towards Texas, the situation continues to highlight the sheer size of the gulf between Democrats and Republi cans when it comes to issues at the border.

Governor Abbott has called the situa tion at the border an ‘invasion’, and has accused Biden of failing to secure the US against illegal immigration. Abbot has also drawn upon ‘compact theory’ to justify himself. ‘Compact Theory’ is a rejected interpretation of the Constitution, claiming that as the States initially agreed upon the Constitution, the federal government should be understood as subservient to the states in all situations. This anachronistic theory has appeared

in arguments by southern leaders in the runup to the Civil War and during desegregation in the 1950s-60s.

The situation is, quite frankly, dire. Texas is using historically racist rhetoric to attempt to justify itself, whilst the federal government appears to be producing a lacklustre stance on the issue. Naturally, with an election looming, Biden may be attempting to shore up his support and is therefore unwilling to alienate Texan Democrats - yet history will judge the President’s inaction as well. Migrants continue to attempt to enter the US through Texas

Government. The prospect of Civil War is attractive to very few people, even those who live and die by the Gadsden ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ flag, so it is likely that when push comes to shove, both the Fed and Texas will try to avoid further confrontation by any means necessary. Nevertheless, we are right to feel uncomfortable in the current situation; both Texas and the US are entering uncharted political territory, the outcome of which is likely to shape the trajectory of the US, for better or for worse, for decades to come.

By Tom Lowe, a 3rd Year PAIS student

Fed using military force against them is near-zero, as this would be seen by many as an attack on the US’ own citizens. Ultimately, the way forward is going to be a quagmire of delicately difficult negotiations between Texas and the Federal

With the global context in early 2024 dominated by elections worldwide amid a cost-of-living crisis, worldwide far-right resurgence, rapidly approaching climate apocalypse, major power tensions and continued horrific wars in both Ukraine and the Middle East where the West has taken sides, Africa hasn’t often made it to the forefront of the Western news cycle. And yet, with a rising, young population, significant natural mineral and renewable resources, and rising emerging regional power actors such as Nigeria, the continent is of ever-expanding geopolitical importance, and deserving of attention. So, we should ask, how well is its supranational government organisation serving it?

The African Union (AU) has taken an increasingly prominent role on the continent recently. Earlier this decade, the AU and African Center for Disease Control garnered praise for their Covid pandemic supply chain strategy; while the continent suffers from weak healthcare provision, this effort limited issues with procurement and acted as a valuable form of prevention and damage control. In January 2023, the African Union Space Agency was finally activated 10 years after its initial announcement, as buildings in New Cairo were handed over to staff. And in September 2023, the AU announced plans to launch a credit ratings agency to encourage investment into the continent, as it considered S&P and Moody’s ratings ‘unfair’. That same month, the organisation permanently joined its sister continental union, the EU, in the notoriously exclusive and influential G20 group. The African Union’s accession can be taken as a sign of acceptance and preparation from G20 members for Africa’s movement to

centre stage over the coming years. At first glance, this flurry of activity may make the AU appear like Africa’s future.

However, the AU is not without its issues. Legitimacy is a prominent one. While the African Union can and often does act as one voice for a continent that has been exploited and used as a pawn for far too long, it arguably suffers even more from democratic deficiency than its European counterpart. Although the pan-African parliament ‘aims’ to be elected by universal suffrage in the future, currently representatives have been appointed by the member countries’ governments, whose democratic and human rights records vary, to say the least. At the time of writing, there are no polled approval ratings for the African Union. Its officials, consisting to a significant extent of members of existing governments, appointees, and unelected bureaucrats, must fight for legitimacy. The tagline of the African Union’s flagship Agenda 2063 objectives, “The Africa We Want” – stands in stark contrast to the relative lack of accountability of the AU itself.

This disconnect between the AU’s priorities and member states and citizens is exemplified by the issue of free movement. As part of work on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), an agreement working towards a common market, the AU proposed treaties enabling free movement of persons and goods. While member states were quick to ratify the free movement of goods, the element of free movement of persons has been more complicated. While the AU stresses this can mean more border controls, not less, to ensure security, member states are rightfully hesitant. As it currently stands, many border zones in the AU have been sites of tension and conflict within living memory. The security problem is compounded by a lack of state capacity across the AU – many states lack centralised citizen identity databases, and much of the AU’s population possess no formal ID. Furthermore, political issues around migration echo those in Europe – local populations cite concerns around em-

ployment opportunities and cultural tension. The hesitation on free movement is understandable, but AU officials are quick to highlight the interconnected nature of these initiatives, saying that if one measure lags behind “the whole integration agenda will be held back.”

The AU and its members have a long road ahead. African democracy remains weak; 6 AU member states are currently suspended, on account of coups and non-peaceful transfers of power. In the Sahel, in the Eastern Congo, Somalia, Mozambique, and Ethiopia, the guns have not gone silent. Meanwhile, many of the AU’s objectives seem ambitious and perhaps naïve, requiring colossal expansions of state capacity, reductions in corruption, and miraculous ends to conflict to appear achievable. But the potential for the African Union as a force for good is very significant and should not be discarded. While there may rightfully be disagreements or concerns on the liberal direction of AU economic policy, migration, or AU goals and legitimacy, these concerns are secondary. The AU is ultimately an adaptable political vehicle, at the centre of which lie its key responsibilities, as an organic unifying and stabilising force for the continent. The AU serves this role and must continue taking these responsibilities, enshrined in the Lomé declaration, seriously. Africa needs both unity and stability to face up to modern challenges and make the most out of its position and resources – and the continent’s rising geopolitical importance means the world needs African stability too.

By Raphael Hammond, a 1st year Politics student from London, UK.

he US has a long and unwavering stake in the Middle East, mostly owing to its erratic funding of regimes, opportunism, and unilateral action that has led to its massive destabilisation. Only a few nations haven’t felt the flaming hand of the American war machine, and Kuwait is one of the very few that have flourished in their relationship with the US. From almost their first encounter, Kuwait has seemed complicit in America’s role in the region. It makes you ponder how that can be so. That a relationship of utter compliance can be maintained in a region surrounded by such instability.

their way through the heart of Kuwait in an effort to completely push Iraqi forces out of the country.

The answer to such a question is that Kuwait required defence from power-hungry states and organisations that the West had directly contributed to. In 1990, Kuwait was ultimately found embroiled in a conflict they weren’t prepared for. A state wrapped up in a barbed wire fence while its supplies were swallowed up by the powerful Iraqi forces. But the state of Iraq was no accident, its power emerged as a direct result of funding from the US and UK during Saddam’s near-decade long war against Iran. They received everything from military aid, to weapons, and intelligence.

Kuwait, following Iraq’s ascendency, had to keep a close eye over their border because of their proximity to these massive Arab powers, and in case a battalion came marching, and it did. Iraq sent 140,000 troops storming into Kuwait with 18,000 battle tanks trundling along the beaten track. In response, in January 1991 American troops supported by military personnel from Britain, France, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union (with authorisation from UN Resolution 678) began attempting to reach the Iraqi army, storming and bludgeoning

The US’ primary reason for pursuing the alliance was to bargain and create conditions for reducing global oil prices. The US inter- vention ensured that Iraqi oil monopolisation was off the table and that risks to suppliesand thus scarcity in the market, and a price hike did not occur. Oil price hikes and scarcity during the war have always been contentious issues, and there is all the more reason for states to inter- vene internationally to ensure a stable supply for the proliferation of such sacred resources. The post-Cold War era also allowed the US to centre their focus away from the Soviet Union to the pursuit of liberal intervention in the Middle East. This surely played a part in US motivations for intervention in Kuwait. Their mission, under Bush during this time, was acting in the role of a global police force, cracking down on the visible growth of terrorism in the Middle East. During the Persian Gulf War, in particular, prices rose – as a result of Iraq’s invasion of Gulf states. Prices reached $40 a barrel in October. Following Operation Desert Storm, the price soon fell back to an acceptable $20 a barrel. There was also the suspicion that Iraq’s forces were deliberately attempting to put global powers in jeopardy for their threat to the West’s reliance on oil from the Gulf. They had dumped well over 100,000,000 gallons of oil into the Persian Gulf, which amounted to reportedly 4,000,0000 barrels worth.

In the 21st century, Kuwait signed a binding Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA), in 2004. This helped to strengthen and solidify already intimate relations. The US could provide security and economic liberty through a binding deal, in return for gaining a link to Kuwait’s massive oil supply. This shows

that the US has built this relationship by the barrel. It imports 3,634 barrels monthly on average, resulting in Kuwait pocketing a generous $279.73 million. Kuwait is the fourth largest supplier of oil to the US, a remarkable feat, considering the nation is roughly 14 times smaller than the UK.

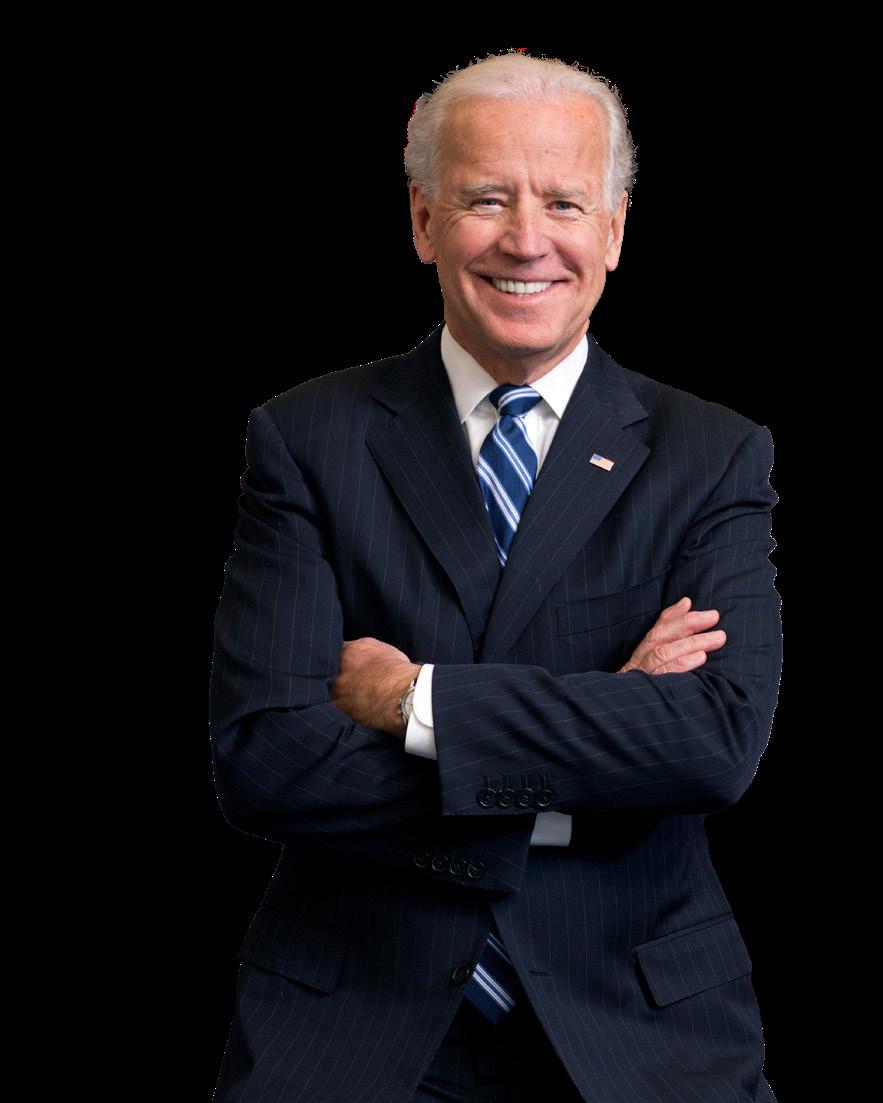

Kuwait is a state that now relies on security provided by the US. In recognition of this, the US works to finance Kuwait to resist the spread of terrorist groups in the region. Joe Biden recognised the nation as a key player in reducing the power of terror groups, in a speech dedicated to the incumbent leader of Kuwait, suggesting in a statement that the US “recognized Kuwait’s constructive diplomatic role in lowering regional tensions.” However, Kuwait’s special relationship with the US paired with the US history of intervention in the region has made Kuwait a threat to terrorist groups. Subsequently, Kuwait is now a target of both ISIS and Al-Qaeda.

The US has become a key player in the Middle East, obliterating nations in the name of handing out democracy. It is most telling however, that its closest relationship is with Gulf States – often the furthest from democracy. Kuwait’s current leader is the most recent in a hereditary monarchy, taking over the position in December 2023 after his brother died – who took over from his half-brother. Generally, if states harbour natural resources they are valued. If states harbour such resources they become sacrosanct grounds for relations to blossom, those states that fail to provide such an intriguing benefit to the US are rarely given thought or prominence in US pursuits for international relations. Those illustrious, head-turning benefits, that procure the heightened attention of many a great power create opportunism for lasting relationships to be formed.

By Taylor

In the grand tapestry of human history, the space race between the USA and the USSR remains a pivotal chapter. An apt reflection of the power balance in the world at the time, the two superpowers were looking to dominate in space as they did on earth. Five decades later, celestial competition is again reflective of such power dynamics. As we look towards a new world order with significant challengers for global dominance, it has become increasingly apparent that there are new players in the cosmic arena.

China:

2030s: Launch of the International Research Station project. anti-satellite weapons + space nukes

Japan:

2023: Successful moon landing mission.

Russia:

Pursuit of the Luna-25 mission to conquer the lunar South Pole.

India:

2023: South Pole moon landing. privatisation of rocket launches + plans for foreign investment.

South Korea: 2023: Launch of a military spy satellite. alignment with the US

China’s space program has transcended just scientific exploration by intertwining it with its military ambitions. The development of anti-satellite weapons and space nukes highlights the strategic nexus between space exploration and national defence. Worries surrounding such exploration have been heightened by the launching of the International Lunar Research Station, a project in collaboration with Belarus, Pakistan, Russia, and South Africa which aims to build a lab on the moon by the 2030s. A move I would say signifies a geopolitical recalibration challenging Western dominance, echoing the alliances of the Cold War era. Yet the United States has not pandered to its challengers. In response to China’s assertiveness, the US has found itself compelled to revitalise NASA and reassert its prowess in space missions – take the new

Space Force for one example.

Another noteworthy disruption to the established narrative comes from Japan, which, armed with a substantial $6.6 billion mission, recently etched its name as the fifth country to achieve a successful moon landing. This technological feat not only showcases Japan’s advancements but also introduces a dynamic shift in the traditional power dynamics of space exploration, reflecting the ever-evolving geo- political order. Meanwhile, Russia, unfazed by sanctions and western condem - nation, pursues its Luna25 mis- sion with unwavering determination, aiming to con- quer the lunar South Pole. Beyond the scientific significance, this mission represents a potent political statement, affirming Russia’s enduring strength in the realm of space exploration and continuing its role as a major player on the cosmic stage.

Meanwhile India’s South Pole moon landing is setting precedent for the BRICS with their moon landing last summer, marking its place among key spacefaring nations. Like many other countries, India has privatised its rocket launches and plans to use foreign investment to further its launch into space. The privatisation of rocket launches and plans to utilize foreign investment underscore India’s commitment to carving a niche in the increasingly competitive space domain. A country set to become the most populous in the world in the near future, India beckons us to consider whether we might be overlooking its potential ascent in the global race for superpower status, often dominated by discussions centred around China.

South Korea, strategically aligning with the United States, launched a military spy satellite in December 2023, marking its charge into the dual realms of space exploration and national security underscoring the interplay between space exploration and militarisation. The alignment between South Korea and the US

in the space arena, particularly in dealing with common adversaries like North Korea and China, showcases a burgeoning alliance; indicative of wider strides taken by the US and its allies to combat challenges to their hegemony.

‘Does the investment in space exploration, often intertwined with military implications, stand justified when such pressing issues persist on earth?’

Amidst these cosmic manoeuvres, a pivotal question emerges. Does the investment in space exploration, often intertwined with military implications, stand justified when such pressing issues persist on earth? Throughout this new space race, the US and China have traded accusations of weaponizing space, each well aware of their intentions. We are clearly yet to move beyond an era in which nations engage in futile battles for symbolic dominance in the extra-terrestrial.

‘The moon, once a unifying symbol of human achievement, now becomes a theatre for transnational rivalries, capturing the attention of the world.’

The space race, once symbolised by Neil Armstrong’s historic steps, has transcended its historical confines, heralding a new chapter where China, alongside other emerging powers, ascends into the stratosphere, marking a 21st-century contest for global dominance. The moon, once a unifying symbol of human achievement, now becomes a theatre for transnational rivalries, capturing the attention of the world. As the celestial power play unfolds, the ultimate question persists: Who will emerge triumphant in this cosmic saga, shaping the trajectory of the new world order? Only time, and the vast expanse of space, will unveil the answer.

By Kate O’Mahony, a 1st year PAIS student from London, UK.

Calls for the re-establishment of what many are labelling modern-day conscription have been circulating through our Twitter timelines since the beginning of the year. Speaking at a Military Conference, General Sir Patrick Sanders lit a fire under the British government warning that the public must be prepared to take up arms in a war against Vladimir Putin’s increasingly aggressive Russia –even if NATO estimates seven years till Russia is back to full fighting power. With the country moving from a “post-war to pre-war world,” the point stands that if war broke out today, troop numbers would be too small and the British army would be overwhelmed. Without a government that can accept they have a nurtured a weak military and the overwhelming mindset of a country that does not feel like it is about to go to war, it is unlikely that any worth while change will be made.

General Sanders has made it clear the nation cannot afford to make the same mistakes it did back in 1914 when we observe the escalations that led to World War One. The Conservative government has “hollowed out and underfunded” the army, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace ad mitted – he himself a former officer. With claims that the UK Army is no longer a top-tier fighting force from American and British Generals alike, surely airing out the government’s dirty military laundry will encourage sufficient change to the current state of the army?

the British Army needed to be 120,000 strong with the addition of reserves. The army must be designed to expand rapidly to “enable the first echelon, resource the second echelon, and train and equip the citizen army that must follow.” This drastic reduction in size is only made worse by a terrible procurement service – with the Ajax Fighting Vehicle entering its 14h year of development and expected to be operational by 2028 (11 years overdue). Is it just an unfortunate coincidence that the Conservative Party took over Downing Street around that many years ago, or

to make up a fleet? Never mind the fact that both are suffering from technical difficulties exacerbated by a lack of maintenance personnel. The Air Force too is suffering, primarily from the lowest levels of retention of all the branches as “extreme” levels of red tape make the service mind-numbingly boring. In fact, the only service that seems to be ‘cracking on’ as we like to say are the Special Forces – perhaps because the government does not comment on their activities and so cannot screw things up with political actions like building aircraft carriers with

Unlike the UK many other European nations have already placed their populations on a “war footing” amidst threats from Russia. Some, including Sweden and Norway, have already established partial conscriptions where some civilians are drafted. Finland, NATO’s newest member, has an estimated 80 per cent male population who complete some form of military service, with refusal leading to possible

In the last 30 years the British Army has halved in size, with a 28% reduction of troops in the last 12 years. General Sanders added that within the next three years

However, it is important not to continue the army-centric approach that has dominated the military in the public eye. It is not just the army that is suffering from size and procurement problems. Under David Cameron, £3.7 billion was spent on HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales – two new stateof-the-art aircraft carriers. Good news, right? Wrong. For what use are aircraft carriers without the aircraft to carry, nor the support frigates and warships

Although for General Sanders it seems that “regular armies start wars” and “citizen armies win them,” the probability of Boris Johnson being Prime Minister again is higher than the likelihood of the UK government establishing a citizen’s army. We may be entering a pre-war world much like we did in the twentieth century, but there are stronger and quite frankly scarier factors at play. A citizen’s army made up of Gen Z is unlikely to intimidate Vladimir Putin’s nuclear arsenal.

By Kara Evans, a 2nd year PAIS student from Dudley, UK.2024 is a general election year in many countries across the globe. In this digital age, this means that this year will be even more so filled with intense campaign periods, powerful newscasts, and anticipation. Venezuela is one of these states and this is the first general election the country has held since the 2018 boycotted elections. After more than a decade in power, President Nicolás Maduro and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela still retain a significant influence in the country, despite years of economic downturn and international sanctions implemented by global institutions. Feelings of political uncertainty, instability and general mistrust are current attitudes expressed by many towards the Venezuelan authorities. This is highlighted by the fact that since 2014, 5.9 million ordinary Venezuelan civilians have been leaving the country in search of better economic opportunities elsewhere (which is approximately 20% of the estimated population), according to the Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants.

254 political prisoners as of 25 October

19,000+ people killed by security forces in 2016-2019

11 in 3 Venezuelans are food insecure

Uncertainty is upheld by the fact that there is no set date yet for the general election. Maduro is coy about a re-election and has ensured that the main rival candidate (Maria Corina Machado) has been prohibited from holding a position in office for the next 15 years, which intensifies these feelings and opinions. Despite being banned days after officially joining the presidential race in June last year, Machado is still participating, in her bid to win; she believes she will be

able to pressure the authorities to remove her ban from holding a position in office. For example, she won a primary election in October 2023 with 90% of the votes. In a recent interview in the central city of Valencia, Machado says “This is my purpose… everything we are doing is for this, because in the end Venezuela must profoundly change.”

The history of exploitation of Maduro’s regime provides some further insight into these feelings of uncertainty and turbulent times. According to the U.S. Embassy, Venezuela ranks 169 out of 180 countries on the Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perception Index. Also, Maduro declared that 12% of the country be a part of the ‘Orinoco Mining Arc’ and awarded himself authority to oversee exploitation of resources for personal gain in 2016 – he has been ruling by decree since 2015. Therefore, Venezuela is currently facing a humanitarian crisis due to economic mismanagement and fear mongering. A United Nations Fact-Finding Mission found ‘patterns of violations and crimes that were part of a widespread and systematic course of conduct that it concluded amounted to crimes against humanity.’ As of 25 October, Penal Forum (a network of pro-bono defence lawyers) has reported 254 political prisoners. Additionally, between 2016 and 2019, police and other security forces killed more than 19,000 people, alleging ‘resistance to authority.’ The World Food Programme also

estimates that 1 in 3 Venezuelans are food insecure.

Furthermore, Venezuela and Guyana have a longstanding border dispute, and this has recently become increasingly heated due to a referendum held last December on Venezuelan rights to annex the oil-rich Essequibo region in Guyana. The area in question covers two-thirds of the country. In 2015, oil was found there by an ExxonMobil-led consortium. Companies started pumping oil in 2019, transforming Guyana into the fourth-largest oil exporter globally. Especially as the economy has faced severe recessions, Venezuela maintains that the oil-rich area was certainly part of Venezuelan terrain during the 19th century Spanish colonial period. Additionally, it is argued the 1966 Geneva agreement nullified a previous border drawn in 1800 by international arbitrators. Maduro’s reason for interest in this was to drum up internal support and distract from US pressure to release political prisoners and wrongfully detained Americans. The referendum was promoted for weeks, faming participation as an act of patriotism and conflating it with a show of support for Maduro.

This year marks an important year for President Maduro and the United Socialist Party. Despite some bilateral support within Latin America, many still don’t consider Maduro as the legitimate leader (including the U.S.) – they recognise Juan Guaidó, the opposition leader who declared himself as interim president in 2019.

The humanitarian crisis, the Guyana-Venezuela conflict, and domestic economic issues make this year’s elections a crucial one to watch.

By Taran Dhillon, a 1st year Politics and Sociology student from Surrey, UK.As farmers rebel in defiance of repugnant regulation and unfettered free trade, many have expressed disdain at what is at first sight a ‘war on farmers’. This may evoke a sense of déjà vu in those who can recall the Dutch farmer’s revolt of 2019 when restrictions placed on nitrogen, since overturned, were met by a deluge of dissent. But when you dig deeper, this war merely foreshadows the coexisting war waged by a class of globalist technocrats - committed to a cosmopolitan future - against the belittled and increasingly marginalised working person. Albeit less amicable, this uprising is inspired by the same paradigm of populist nationalist thought – opposition to the global centralisation of authority –that Brexiteer and Trump voters exhibited in 2016.

The disorder, which has manifested over many months, no longer resembles the civil disobedience of yesteryear. Farmers across Europe, specifically France, Belgium, Portugal, Greece, and Germany, have engaged in a contagious grassroots effort - now transnational in reach - in support of the overthrow of destructive and crippling measures - issued in the name of the environment – that have stifled food production, crop yield and the productivity of mundane agricultural practices. Under the banner of ‘no farmers, no food, no future’, farmers are directly coalescing against a conglomerate of governments and international governmental organisations, such as the EU and the UN, in seek of the abolition of top-down heavy farming restrictions.

The German tractor revolt saw 5000 farmers protest measures to reduce CO2 emissions, which tax diesel used by agri-

cultural vehicles, at an unwarranted and unprecedented level. This would deliberately create scarci ty in food production as farm ers can’t afford to buy enough diesel to grow food. Meanwhile, another proposition was made in Ireland to cull 200,000 cows to reduce methane emissions produced by flatulence. This is moronic on not only a moral but also practical level, as it actively endorses the destruction of the countryside, since cattle can cultivate the Earth and restore spent land.

Farmers have rebelled in numerous ways: tractors were used in Portugal to block the three roads that linked the country to Spain; Greek farmers drove tractors across Thessaloniki with black flags (denoting the death of farming); and supermarket distribution centres were disrupted in Belgium. Whilst this behaviour is difficult to comprehend, in a sector already demoralised by debilitating surveillance - from tidal waves of paperwork to drones monitoring compliance with the new directives - farmers have little to lose in an industry falling by the wayside. Tragically, in France, a farmer commits suicide every two days. In the past few years, fifty farms have ceased operation.

Myriad regulations designed to reduce greenhouse emissions increase pressure on an industry already in financial ruin. But the EU’s 2019 Green Deal, responsible for the new directives, is not the only catalyst to have galvanised farmers.

Romanian and Polish farmers protested unfair competition from Ukraine after the EU decided to import wheat without quotas or import duties. The general re-

not subject to the same regulation, can be equally applied to the EU’s trade deal with Chile – another country immune from EU standards. This anti-protectionist, hyper-liberal approach to free trade, justified under the veneer of neoliberalism and the global common good, makes life hellishly unaffordable for farmers and henceforth intensifies the war on farmers.

All is not lost for the farmers, who, after a summit in which EU leaders convened to deliberate these issues, have persuaded the European Commission to work with Belgium to reduce the administrative burden on and limit farm imports from Ukraine. Whilst the farmers make some ground, the ubiquitous nature of these regulations in an era of climate anxiety, combined with the ascendancy of globalist power structures, the likelihood that farmers will be liberated from state interference to recapture their sovereignty is evaporating. The future projection of the European farming industry is a bleak one. With deindustrialisation and net zero on the horizon, farming may become a thing of the past.

By Ethan Harvey, a 1st year Politics student from Suffolk, UK.“In the rush to get the

deportation

plan

onto the statute

books, the

UK

government is still choosing to turn its back to legitimate concerns about Rwanda’s domestic rights situation.”

Numerous peers in the House of Lords expressed much dismay at the Tories’ Safety of Rwanda Bill, rebuking the idea that Parliament can arbitrarily declare Rwanda absolutely ‘safe’ for migrants. One crossbench peer even compared it to legislating ‘the sky green, and the grass blue’. In the rush to get the deportation plan onto the statute books, the UK government is still choosing to turn its back to legitimate concerns about Rwanda’s domestic rights situation.

President Paul Kagame rose to power in 2000, following several years in the Rwandan Patriotic Forces (RPF) - the rebel group that seized control of the country after around 100 days of horrific genocide. For many years, he has been laser-focused on building Rwanda’s image in the Western media and internationally. He has defended his strong leadership style, suggesting that Rwanda needs it post-genocide, and has overseen a cleansing of the government’s image.

Such cleansing has sometimes taken on grim physical forms. In 2021, advocacy group Human Rights Watch reported that street vendors, homeless children and LGBT+ people had been rounded up off the streets of Kigali and detained before high-profile international meetings were due to be hosted there. Many were detained in the Gikondo transit centre,

known for its extremely poor conditions, and suffered frequent beatings there.

Most were not charged or convicted with anything, indeed their only crime was being seen as ‘un-Rwandan’ by a government seeking to hide anything which may undermine its delicately-constructed image on the world stage. This is a significant blot on Kagame’s claimed record of defending the Rwandan people. He himself sinisterly declared that “anyone who wishes our people ill will fall victim. What remains to be seen is how you fall victim.”

The limited place for political opposition is not so much well-camouflaged as it is widely apparent, and hiding in plain sight, for those willing to acknowledge it. The problem is that journalists and dissidents who live and work in Rwanda, or even report on it from abroad, have faced sustained campaigns of online harassment, and in the case of former Rwandan Intelligence Chief Patrick Karegeya, have paid with their lives. Whilst the Rwandan authorities focus principally on what people can see and read, for example, the impressive economic and development projects in the capital and the provisions in Rwanda’s constitution which enshrine political freedoms, in practice it is enormously difficult for critics in the country to question the political status quo without falling foul of some law.

“A free and robust opposition, however undesirable it may be to Rwanda’s ruling coalition, would revitalise Rwandan democracy, not least as proof of change amidst allegations of electoral fraud.”

In July this year, Rwandans will once again head to the polls to elect a president. It is unsurprising that Kagame has indicated he will run again; he was explicitly afforded an exception to new two-term limits introduced in 2015 constitutional reforms, allowing him to remain president up to 2034. In 2017, during the previous

election, the country’s National Election Commission barred those critical of the government from running. Diane Rwigara, one of those targeted and subsequently imprisoned on charges she denies, noted that “our government has invested in the visible…but they have forgot or ignored our people.” A free and robust opposition, however undesirable it may be to Rwanda’s ruling coalition, would revitalise Rwandan democracy, not least as proof of change amidst allegations of electoral fraud.

Paul Kagame: Rwandan Patriotic Front; Ideal Democratic Party; Democratic Union of the Rwandan People; Prosperity and Solidarity Party; Rwandan Socialist Party

Frank Habineza: Democratic Green Party of Rwanda

Rwandan society has transformed beyond recognition under Kagame’s presidency, and there have in fact been a couple of positives. The inter-ethnic hatred and attacks on the Tutsi minority that once divided families and neighbours have been slowly replaced by a climate of remembrance and community cohesion. One example is Umuganda, the national program of community work, with sessions held monthly. Also, in the Parliament’s lower house, women are well-represented with 64% of total seats as of 2016, even if opposition parties are unfortunately not. In the Rwandan government’s quest for belonging on the world stage, it is easy to conclude that aesthetic triumphs over all else. Ideas and individuals deemed undesirable or unsightly are regularly denied visibility. As the saying goes: ‘out of sight, out of mind’. In this election year, it is imperative that democratic values are not left to disappear into the horizon.

ByRavi Maini, a 2nd year PAIS and French student from Leicester, UK.

In PAIS we value your feedback; we know this is a challenging time and we want to do all we can to support you to succeed. Based on your ideas, we have put together an exciting agenda of events, activities and opportunities this term and beyond - please check our emails, social media and webpages for more details.

Academic support for students is a top priority for PAIS so please:

- Sign up for our Virtual Common Room chats on a range of topics including essay wrtiting, wellbeing and the liberated curriculum.

- Benefit form our online workshops on essay writing for second years and finalists.

- Benefit from our online workshops on preparing for your online open book exams.

In response to your feedback, we have put together detailed online guides on making your study choices, including whith modules to takes, which assessment methods to choose and advice on applying to postgraduate study.

We want to hear from you and have a number of opportunities for you to feed-back on your course throughout the year including via your Course Reps and our end-ofyear module evaluation surveys. There is also the National Student Survey (NSS) which will open for finalists on Monday, 8th February - we would love you to complete it!

Following your feedback, we are running an Employability Series with a number of exciting speakers from a range of careers speaking at events this term. Details will be shared shortly.

Embed yourself in the PAIS research culture and ettend our Wednesday Research Seminar Series which is open to all PAIS staff and students. Finalists are also encouraged to join the Burning Issues: Geopolitics Today MA lecture series which focuses on contemporary world politics.

Follow Us on Social Media to find out more:

www.twitter.com/PAISUndergrad www.facebook.com/paiswarwick www.instagram.com/paiswarwick

#WeArePais

Faced with a rapidly approaching general election, it is worth reflecting on the past 14 years of Conservative government: the catalogue of catastrophe, corruption, and ignominy which the country is still reeling from today. James O’Brien attempts to explain how Britain has broken down to such a shocking extent.

Britain’s decline can doubtlessly be attributed to any number of incompetent or malicious personages, but O’Brien narrows down this extensive line-up to those whom he deems the ten main culprits, most of whom will be familiar figures to the casual political observer. His chapters on Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss are predictably brutal (Truss is granted an appropriately short section), while Andrew Neil and Jeremy Corbyn may at first appear incongruent in the company of the aforementioned charlatans.

shady, neoliberal think tanks. Laid out in such plain terms, it is no wonder that our current political system is wholly dysfunctional, giving a carte blanche to conmen and reprobates (Sunak’s reappoint ment of Braverman comes to mind). The degeneration of British politics was in no way a product of poor fortune, but an inevitability.

“One must only look to the zealous right wing of the Conservative Party, or even Starmer’s obsession with “fiscal rules”, to see that the appalling ideology behind austerity is alive and kicking.”

“The degeneration of British politics was in no way a product of poor fortune, but an inevitability.”

In audiobook format, How They Broke Britain resembles the best of O’Brien’s monologues on his popular LBC show, stuffed full of his usual aphorisms concerning, for example, what he terms the populist right’s denial of “observable reality”. He recognises many of the root causes of modern Britain’s problems, such as the malignant hegemony of the rightwing press, the private school system’s inculcation of arrogance and ignorance in future leaders, and the rising influence of

wing of the Conservative Party, or even Starmer’s obsession with “fiscal rules”, to see that the appalling ideology behind austerity is alive and kicking.

O’Brien’s chapter on David Cameron is perhaps the most nauseating, unexpectedly so. Even overlooking Cameron’s blasé approach to the economic calamity that was Brexit, his policy of austerity appears truly unconscionable, considering the evidence that O’Brien has meticulously compiled. He analyses the links between austerity and the result of the 2016 referendum, citing Warwick professor Thiemo Fetzer’s research as evidence of the strong correlation between deprivation of public services and support for UKIP. Now consider the recent resurgence of Victorian era diseases like rickets and tuberculosis, as well as the sickening fact that British children growing up during austerity are on average shorter than their European counterparts due to malnutrition and NHS cuts. The socio-economic impacts of Cameron’s austerity are evidently re pulsive, and O’Brien makes it clear that such an absurd attitude to cuts in public spending remains preva lent in Britain today. One must only look to the zealous right

Other topics covered include the deeply reactionary racism of Paul Dacre, Corbyn’s (partial) culpability for Brexit, and bogus claims of left-leaning BBC bias, yet for me the key takeaway is the long-term impact of Brexit upon honesty and competence in O’Brien suggests that

lusion in the highest levels of government resulted in more principled, prudent fig ures being confined to the backbenches, leaving shameless opportunists like Johnson free to take the reins.

“a must read which is crucial for understanding the current state of British politics”

It is notable that O’Brien’s account never strays into the polemical; he retains a firm factuality, allowing a thorough, albeit understandably emotive, analysis of the prejudice and division promoted by the political class, aided and abetted by an increasingly populist media establishment. How They Broke Britain is undeniably a must read which is crucial for understanding the current state of British politics, as well as how to reverse its undignified decline.

By Ben Tanguy Brown, a 1st

By Ben Tanguy Brown, a 1st

year English Literature student from Cambridge, UK.

Emerald Fennell’s 2023 film Saltburn has taken the world (and TikTok) by storm due to its incredibly disturbing scenes. It’s a beautifully shot psychological thriller with a brilliant storyline. Filled with suspense and a sense of unease, the film completely drew millions of viewers in. It goes without saying, but if you haven’t seen the film, please stop here, spoilers ahead!

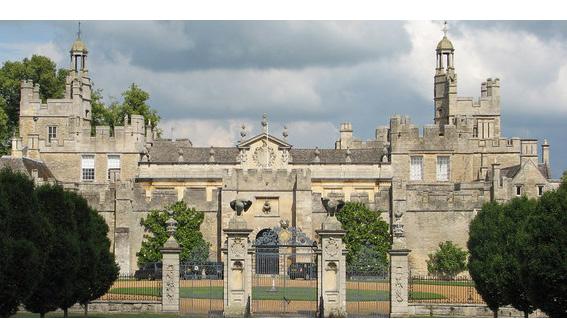

A ‘period piece’ set in 2006, Saltburn follows the story of Oliver Quick, a seemingly lower-class man trying to climb the social ladder into the upper classes of his friend Felix Catton at Oxford. After the tragic death of his father, Oliver is invited to spend the summer with Felix’s family at their estate: Saltburn. But looking at this film through a different lens uncovers a deeply rooted theme of British class dynamics that Fennell highlights through the relationships of her characters, and the mouth-watering desire to achieve the status of the ultra-rich mega-money class of the Catton family. Oliver embodies this desire, as he goes through the deepest darkest extremes to achieve it.

there is an element of saviourism to this dynamic, as Felix subtly flexes his wealth and Oliver paints himself as the victim, with his parents both being drug users and his having a deeply traumatic childhood. At points, Oliver begins to annoy Felix, and he is then discarded, like an unwanted object, just as easily as he was picked up. So, Oliver escalates his scheme, claiming his father had died, gaining him an invitation to the Catton family estate for the summer.

It is here where the class dynamics are magnified, as Oliver is clearly an anomaly in the Catton family setting. He doesn’t know the right protocols or where to eat breakfast, and the Cattons are deeply out of touch with reality, not even knowing where Liverpool is. Oliver makes himself unexpendable to the family, assimilating, creating deep relationships with each individual member, and serving their individual desires.

By Milly OwenThe film opens on a shot of the University of Oxford; an obvious symbol of elitism, it shows Oliver, an outsider, though it is later revealed he is not the underprivileged child he once presented himself as, who is still not at the status needed to assimilate at this institution. There are circles of friends, clearly families having known each other prior, and Oliver is a firm outsider to these circles. Through his interactions with the faculty, we see them favour other students due to their last

Following a series of tragic events, we see the family process grief in a very standard English sense, by not doing so. “We don’t want your bloody American feelings” is the best way to sum this up, with their use of artificial cover ups and paying for things to be removed. As the family members are gradually killed off, Oliver works his way up the ranks until he is made the sole heir to the Catton estate; it is discovered he was ultimately the mastermind of this plot to reach the ultra-rich upper class.

Saltburn shocks in a myriad of ways, but mainly in the expectations of the film; it’s not the ‘eat the rich’ tale told before. Ol the insecurities of these and infiltrating this old film, Fennell’s deep dive

“the SU is committed to listening to the student voice - all you have to do is be willing to engage.”

Warwick’s Student Union is democratic. There’s no other way of seeing it. Whether it be through its organisational structure or general values as an institution, the evidence is overwhelmingly on my side. I will admit, as a Student Councillor, forum member and person who is generally quite involved in the SU, I might be biased. I’ll do my best to not ramble about the minutiae of SU politics, but I make no promises.