Project Scrapbook: Skybridge

Project Scrapbook: Skybridge

Welcome to the Summer 2024 issue of The Narrative, which captures our culture and reflects our priorities. At Perkins Eastman, communication in its many forms is key to our work—and to the topics in this issue. For example, we find ourselves introducing clients to net zero energy, embodied carbon, and other critical earth-friendly concepts with increasing regularity. “Speaking of Sustainability” clarifies the jargon around these terms, and “Healthier Materials, Healthier People” stimulates the conversation.

Convening in person to exchange bold ideas is in the Simons Foundation’s DNA and at the heart of the challenge to create a pedestrian connection between its two noncontiguous buildings in the Flatiron District of Manhattan. Learn how the firm communicated the appropriateness of its boundary-pushing, glass-and-carbon-fiber design to the client and city officials in “Skybridge.”

Medical campuses are being dramatically transformed to increase interactions among staff, students, patients, their families, and local communities. Dive into the master plans in “Rx for Change.”

Design competitions give firms a chance to “make some noise” and, in some cases, catapult them to the global stage. These competitions are also opportunities to experiment, sharpen skills, and spur lively discussions. See “The R&D Dividend.”

In “Proof Positive,” learn how a new Perkins Eastman-Drexel University study reveals that school modernization significantly improves key educational indicators. Our K-12 Education practice is communicating the findings and deploying valuable tools developed for the study to help school officials make educated decisions regarding facility improvements.

In addition to settings conducive to learning, students reap big benefits from mentoring. Through long-established programs with nonprofits, our PEople teach critical thinking and collaboration skills to aspiring architects in “Engaging Young Minds.”

Consensus building is another way our firm communicates. In “Studio Spotlight,” we highlight one of our affiliates, BFJ Planning, a small team that makes a big impact on communities in the Northeast and farther afield.

In “Perspectives,” discover the “happy people” drawings that Principal Frances Halsband, one of our esteemed architects, creates to imagine the interactions taking place in her projects. And meet intriguing PEople from our 1,000-strong staff: At 16, Jason Abbey, a co-managing principal in our Washington, DC, studio, bicycled from New Jersey to Oregon. Our Director of Sustainability Heather Jauregui used 96 percent less water per month compared to the average American when she volunteered in Africa after college. Enjoy their stories and more in our Summer 2024 edition of The Narrative

Communications Team

To view The Narrative online, go to https://perkinseastmanthenarrative.com/summer2024/

LET US HEAR FROM YOU

Please send questions, comments, or story ideas to: humanbydesign@perkinseastman com © 2024 Perkins Eastman. All Rights Reserved.

EDITOR IN CHIEF

TRISH DONNALLY

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

ABBY BUSSEL

CONTRIBUTORS

EMILY BAMFORD

JENNICA DEELY

TANYA EAGLE

NICK LEAHY

JENNIFER SERGENT

EDITORIAL DESIGNER

BROOKE SULLIVAN

GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITOR

KIM RADER

PHOTO EDITOR

SARAH MECHLING

WEB DEVELOPER

NICK PUGLIESI

On the Cover

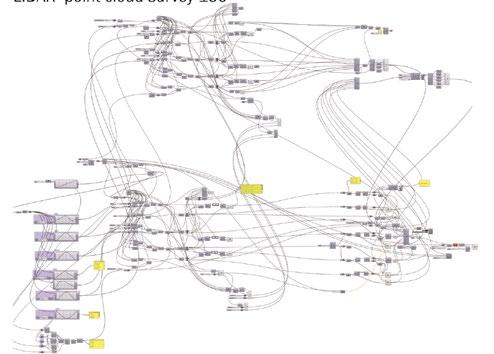

The cover design is a point cloud façade detail of 162 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. It’s derived from Lidar survey data and used to refine structural connections and architectural intersections between the Simons Foundation Skybridge (page 12) and its historic host buildings. Point cloud reconstruction and postprocessing by Pablo Cabrera Jauregui | © Perkins Eastman

Opposite Page Top

A modernized elementary school classroom corridor. Photograph © Joseph Romeo

Opposite Page Center

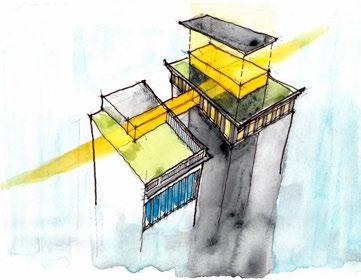

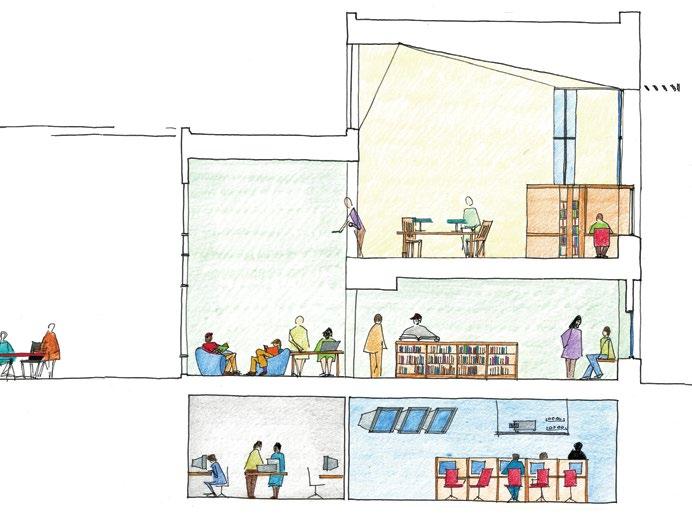

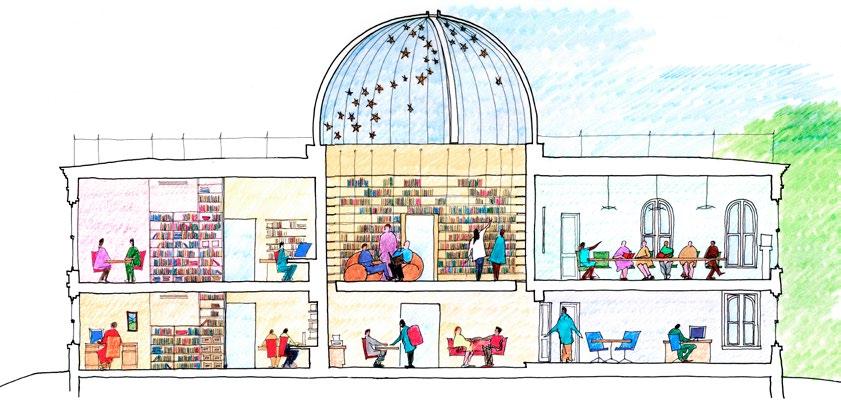

The Simons Foundation’s “light of knowledge” concept. Watercolor by Andrés Pastoriza | © Perkins Eastman

Opposite Page Below

The “happy people” of Vassar College’s English Department. Drawing © Frances Halsband | Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Project Scrapbook: Skybridge

studio stories

Proof Positive | 02

Children, teachers, and communities win in modernized schools

Engaging Young Minds | 06

Mentorship motivates aspiring architects and enriches the profession

Studio Spotlight: BFJ Planning | 08

A small team makes a big impact

design lab

Project Scrapbook: Skybridge | 12

Connections across time and space inspire a unique design

Rx for Change | 20

Treating what ails them, medical institutions are being transformed

Speaking of Sustainability | 26

Carefully defined goals counter the pitfalls of vaguely defined terms

Healthier Materials, Healthier People | 32

Gallery: People, Places & Things 12

Upending old practices has material benefits

The R&D Dividend | 36

Win or lose, design competitions test ideas and sharpen skills

perspectives

Gallery: People, Places & Things | 44

“Happy people” activate the space between floor and ceiling

Take 5: Conversations with PEople | 48

Five Perkins Eastman PEople muse on life and work

Children, teachers, and communities win when the performance and quality of educational environments improve, a comprehensive study suggests.

BY JENNIFER SERGENT

It may seem like common sense to assume that comfortable temperatures, abundant natural light, and a welcoming civic presence would benefit a school’s occupants. But Perkins Eastman has backed that assumption with a decade of research, recently culminating in a multiyear study with Drexel University. “Addressing a Multi-Billion Dollar Challenge” reinforces the firm’s previous work with larger samples that make it statistically significant. The increasingly indisputable message is that the quality of a school’s structure, layout, interiors, and landscape—even its standing in the community—has a material impact on the performance and well-being of those who work, teach, and learn there. The study’s implications for school districts across the country are far-reaching: nearly 50 million children were enrolled in public schools in 2021, and the average age of public schools in the United States is 49 years, based on the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics, yet the nationwide shortfall in maintenance, operations, and capital expenditures at those schools has reached $85 billion annually, according to the “2021 State of Our Schools” report published by the 21st Century School Fund, International WELL Building Institute, and National Council on School Facilities.

The Perkins Eastman-Drexel study, published earlier this year, was funded in part by the Latrobe Prize, a biennial $100,000 grant from the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows that supports “research leading to significant advances in the architecture profession.” J+J Flooring provided an additional $30,000 as

part of its continued support of Perkins Eastman’s research. Testing indoor environmental quality, a school’s “educational adequacy,” and its community connections, the study compared conditions at 28 modernized and non-modernized schools across District of Columbia and Baltimore City public schools. The K-12 Education practice has since put the assessment tools created for this study to effective use in other school districts. “They are significantly enhancing our strategic planning capabilities,” says Perkins Eastman Principal Sean O’Donnell, who leads the practice. “With the addition of these tools, we can help clients really understand the performance and the quality of their learning environments.”

O’Donnell and his team knew they were onto something when the new building they designed for the historic Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School opened in 2013, replacing the deteriorated facility it previously occupied in Washington, DC. In achieving its LEED Platinum certification two years later, Dunbar became the highest-scoring LEED for Schools project in the world. Student test scores increased faster than they did at any other school in the district the following year, and graduation rates rose. (The rates have continued upward, from 60.3 percent the year before the new building opened to 83.4 percent in 2022.)

Based on those early numbers, “Sean started to say, ‘I think this is proof that high-performance, sustainable projects contribute to better educational outcomes,’” notes Perkins Eastman Associate Principal and Director of Sustainability Heather Jauregui. That’s when they asked Senior Associate and Design Research Director Emily Chmielewski to begin a regular practice of performing pre- and post-occupancy evaluations on new schools and renovations. Her work led to “Investing in Our Future,” a 2018 white paper that compared the indoor environmental quality—thermal comfort, daylight, acoustics, and air quality—at nine modernized and nonmodernized schools in the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) system. That study found a statistically significant correlation between a modernized school’s indoor environmental quality and its occupants’

improved satisfaction and well-being. Perkins Eastman Principal Patrick Davis, who at the time was the DCPS chief operating officer, presented the results of “Investing in Our Future” to the city. The mayor and city council “fully bought into really trying to understand and acknowledge that the building modernization program at DCPS was having a positive impact,” he says, “and after that, we saw increases in our budgets.”

O’Donnell acknowledges, however, there were still unanswered questions: “When we conducted the nine-school study, we didn’t focus on the programming of the buildings—do they support contemporary teaching and learning practices, curricula, and pedagogies?” When the AIA College of Fellows opened its submission process for the 2019 Latrobe Prize, the timing inspired O’Donnell, Jauregui, and Chmielewski to expand their line of inquiry. Davis agreed to be a stakeholder representative for the grant application. And by coincidence, O’Donnell had just met Bruce Levine, a Washington, DC-based clinical professor at Drexel’s School of Education and director of its Education Policy Program. One of Levine’s primary research interests is community schools. “I was interested in exploring how the school building itself impacted various stakeholders and, specifically, the community surrounding it. I hadn’t seen much work done around that,” Levine says.

The group’s collective expertise and interests proved a winning combination. The Perkins Eastman-Drexel research collaboration, formalized as the Consortium for Design and Education Outcomes (CDEO), secured the 2019 Latrobe Prize, plus the additional funding from J+J Flooring. Although the pandemic delayed some of the fieldwork and altered the collaborators’ approach to some degree, the study showed statistically significant results that confirmed and expanded upon the earlier research. “Now we have the data to support all the beliefs and approaches Perkins Eastman has been preaching for years,” says Associate Principal Karen Gioconda, the study’s project manager.

The study’s findings indicate that modernized schools outperform non-modernized schools in several areas,

The modernization of this elementary school changed the layout of its existing building, turning double-loaded classroom corridors into single-loaded corridors that allow light to enliven passageways and flow into classrooms.

Photograph © Joseph Romeo

Below

The difference between the learning ambiance of modernized (left) and unmodernized (right) classrooms is stark. Modernized

Photograph © Robert Benson Photography; Unmodernized

Photograph © Perkins Eastman

including indoor environmental quality (echoing the smaller 2018 study); first impressions on arrival; better safety measures and strategies; and “enhanced learning ambiance.” Evidence also emerged, in line with those first indications at Dunbar, that modernization correlated with increases in test scores, graduation rates, and enrollment over time. A modernized school’s strength in the community was harder to quantify due to the pandemic, though early indications were positive and will receive further investigation.

Even before the report was completed, Davis was using the study’s Visual Assessment Tool (VAT) for strategic consulting. Traditional school assessments evaluate building conditions, O’Donnell explains. “While assessing the physical integrity of a building is important, these assessments typically ignore whether the building is actually a supportive place to learn. Is it a good 21st-century school?” The VAT, conducted using a smartphone app, enables users to survey and document conditions such as safety and security, classroom organization, ease of navigation, and indoor and outdoor “ambiance.” The VAT is already in its third generation and in use with multiple clients. “We’re able to show them where they’re deficient in terms of meeting what we identify as a 21st-century learning environment,” Davis says. “It’s opened up a lot of eyes in terms of what a school building could and should be.”

Last November, the Colorado Springs school district awarded $80 million for improvements to Palmer High School, which the VAT showed to be most in need of modernization among its four high schools during a district-wide assessment. “That probably wouldn’t have been done if we didn’t share the VAT data and help the district understand the importance of it,” Davis notes.

The “Addressing a Multi-Billion Dollar Challenge” researchers were unable to interview as many students, teachers, parents, and community members as they would have liked during the pandemic. But COVID-19 demonstrated that many people relied on their schools for multiple forms of assistance such as meal pickups and social services, Chmielewski says. “In some ways, it was interesting for COVID-19 to happen during this study because the community-connectivity piece of it became so much more valuable—we saw clear examples of how a school serves more than just an educational purpose.”

The CDEO has already embarked on a second, related investigation, examining how a school’s design can make it a better community partner with features such as food distribution, adult General Educational Development classrooms, health clinics, and publicly accessible recreational and meeting facilities. In this respect—not to mention the enduring benefits for students, teachers, staff, parents, and other local stakeholders that modernization has already brought about—Perkins Eastman’s decade of groundbreaking research continues to transform the landscape for public school education and its community-wide influence. N

Above

Modernized schools break free from their walls to bring learning outside—a recognized benefit for student performance, Perkins Eastman’s design researchers have found. Photograph © Joseph Romeo

Below

The visual assessment tool created for this study features 234 questions to assess eight factors defining the educational adequacy of a school’s learning environment. Diagram © Perkins Eastman

“Children start establishing their interests much earlier than college, and it’s through engagement and mentoring that you reach a more diverse set of populations for the next generation of design professionals,” says Mindy No, a principal in Perkins Eastman’s New York office and longtime advocate and mentor of children in the city’s public school system. Her comments reflect the firm’s multifaceted approach to building and diversifying its talent pipeline and deeply rooted tradition of giving back to the profession and allied disciplines.

Starting with the youngest potential designers, Perkins Eastman has long supported the Salvadori Center in New York, a program that creatively integrates Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) through real-world applications, utilizing the built environment to address gaps in instruction and, in the process, educating students about architecture, engineering, and community planning. Perkins Eastman Co-Founder and Vice-Chair Mary-Jean Eastman served on the board for many years, and, today, Co-CEO and Executive Director Nick Leahy is a board member who participates in the center’s fundraising and curriculum development efforts. Russell Scheer, an associate in the firm’s New York studio and member of the Salvadori Center’s Emerging Leaders Advisory Council, contributes much of his spare time to the center’s after-school programs and summer camps for elementary and middle schools, as well as other youth education organizations in the city. “I’m always reinvigorated by the passion I see in these students to become architects or to become engineers. When I meet their parents at the end of the year and get to see how proud they are, that is the best,” Scheer says.

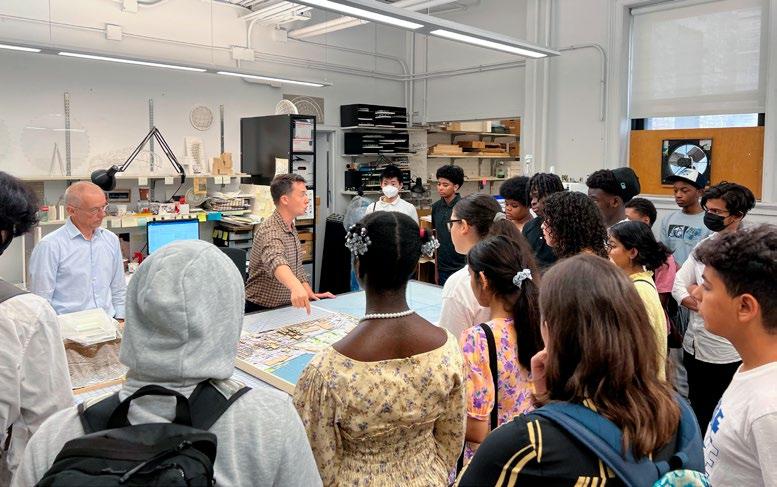

Opposite Page Students from Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School (top) in Washington, DC, participate in the ACE Mentor program, working with Perkins Eastman volunteers, including Sustainability Specialist Juan Guarin (far left in photo), to create structures with spaghetti and marshmallows.

Gordon J. Lau Elementary School students (below) design and build a sandcastle with volunteers from the firm’s San Francisco and Oakland studios at the Leap Sandcastle Classic held on San Francisco’s Ocean Beach.

Above

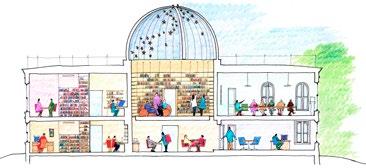

Associate Russell Scheer presents a recent project to middle school students participating in a Salvadori Center after-school program in Perkins Eastman’s New York studio.

All Photographs © Perkins Eastman

Across the country, Perkins Eastman’s Oakland and San Francisco studios participate in Leap Arts in Education’s Sandcastle Classic, an annual competition that playfully engages elementary school students interested in the built environment while raising money for the organization’s arts programming for local students.

The ACE Mentor Program (ACE), a national after-school program for high school students, picks up where programs for younger students leave off. In New York, the firm sponsors Team 18, a group of 30-plus high schoolers from all five boroughs led by No and Scheer, following in the footsteps of Associate Principal Ty Kaul, who has mentored ACE students for many years.

The team meets for more than 30 weeks each year, working on projects, learning industry software, and visiting construction sites. And the firm’s ACE team in Washington, DC, led by Miranda Ford, mentors students from Paul Laurence Dunbar Senior High School, a Perkins Eastman-designed school. In addition, studio volunteers teach architecture to fifth graders through the Washington Architecture Foundation’s Architecture in the Schools program.

Perkins Eastman also participates in programs established by the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA). In Pittsburgh, the funding the firm provides as a sponsor of the local chapter is applied to initiatives that include NOMA’s Project Pipeline winter workshop and summer camps benefiting middle and high school students from under-resourced schools. “I have found a lot of meaning in my work with NOMA.

Because of our outreach and initiatives, I know that we’re going to see diversity in the profession continue to increase in the coming years,” says Dalenna Carrero-Rivera, an associate at Perkins Eastman and current executive board member and secretary of NOMA Pittsburgh.

NOMA’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities Professional Development Program (HBCU PDP) is an avenue for the firm to attract students already in architecture school. Partnering with the seven HBCUs with accredited architecture programs, the PDP facilitates mentorship, recruiting, and networking opportunities with architecture firms across the country. Though Perkins Eastman has recruited from these institutions for many years, the NOMA program deepens the firm’s commitment.

“The major growth in the diversity of our teams and leadership in the last few years is a credit to the strong foundations we already had in place prior to 2020. The relationships we’ve established with ACE and NOMA have been essential,” says Emily Pierson-Brown, associate principal and people culture manager. By reaching students early, providing mentorship, and actively participating in industry-wide initiatives, Perkins Eastman is playing a crucial role in shaping a more inclusive future for the architecture profession. Jarvis Cook, senior associate and talent acquisition manager, sees headway as well: “We’re making progress. We just can’t take our foot off the gas.” N

A small team makes a big impact through community outreach.BY EMILY BAMFORD

BFJ Planning affects the daily flow of life in cities and towns both in the Northeast United States and much farther afield. The firm, which celebrated its 25th anniversary as an affiliate of Perkins Eastman in 2023, is a multidisciplinary practice with expertise in planning and zoning, urban design, environmental planning, real estate consulting, transportation planning, and sustainability and resiliency.

The New York City-based firm was founded in 1980 by Principal Paul Buckhurst (now retired) and Principal Frank Fish and is officially known as Buckhurst, Fish & Jacquemart; Principal Georges Jacquemart, who was recently named a Fellow of the American Institute of Certified Planners, became a partner in 1991. BFJ places great emphasis on collaboration both internally among its staff members and externally with its clients in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. The firm is also supported by its affiliate Urbanomics, Inc., a consultancy led by Principal Tina Lund that has provided economic development planning studies, market studies, tax policy analyses, program evaluations, and economic and demographic forecasts since 1984.

Perkins Eastman’s Co-Founder and Chairman Brad Perkins says, “BFJ’s joining with us was really a reuniting of old colleagues. MaryJean Eastman (co-founder and vice chair) and I had worked with Paul Buckhurst and Frank Fish when we were all at the British firm Llewelyn Davies. Our practice has always been built on our ability to act as an advisor to our clients from the earliest stages of their projects. BFJ brought us a number of important, complementary skill sets that greatly strengthened our pre-design services.”

BFJ has completed more than 1,000 projects in the United States, East Asia, Europe, and South America—many of them transformative in nature.

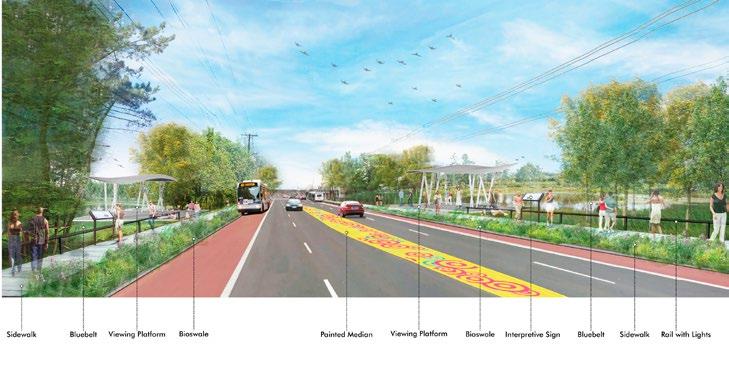

The firm has led the New York State Downtown Revitalization Initiative, an economic development project, since 2016. “We help communities throughout New York dream big while selecting strategic projects that will jump-start the revitalization of their downtowns,” says Principal Susan Favate, who has been with the firm for 18 years. Equally impactful is the NY Rising Community Reconstruction Plan for Staten Island, which was developed in response to Hurricane Sandy. Principal Sarah Yackel managed the multidisciplinary team, led by Perkins Eastman, that worked closely with community representatives to gain consensus on the use of federal rebuilding funds. “The critical importance of this project, coupled with the emotional weight of the damage done to the community, including the loss of life, homes, businesses, and critical infrastructure, made this project both challenging and incredibly rewarding,” Yackel says.

Founded: 1980

Joined Perkins Eastman: 1998

Staff: 18

Practitioners: architects, economists, environmental planners, fiscal analysts, land-use planners, planners, project managers, transportation planners, urban designers

Completed Projects: 1,000-plus

Recent Awards: 2023 Outstanding Community Engagement Award, American Planning Association New Jersey Chapter: OUR Jersey City Master Plan; and 2021 Heissenbuttel Award for Planning Excellence, New York Planning Federation: Mount Kisco Comprehensive Plan and Downtown Overlay Zone

BFJ Planning staff members gathered for a portrait in the firm’s New York studio (left to right): Planner Eshti Sookram; Senior Planner Mark Freker; Planner Nile Johnson; Principal Sarah Yackel; Associate Principal Noah Levine; Principal Georges Jacquemart; Associate Principal Jonathan Martin; Planner Emily Tolbert; Planner Suzanne Goldberg; Principal Frank Fish; Urbanomics Principal Tina Lund; Senior Planner Christine Jimenez; Planner Lucy Pidcock; Principal Susan Favate; and Associate Principal Thomas Madden. Not Pictured: Associate Silvia Del Fava; Office Manager Françoise Mohamed; and Evan Accardi, an intern. Photograph by Sean Duggan | © Perkins Eastman

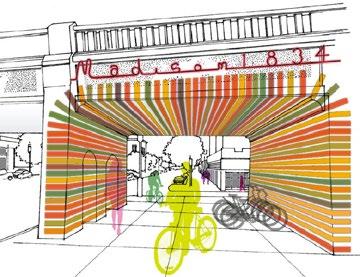

Opposite Page

BFJ’s conceptual design for Waverly Place in Madison, NJ, includes ideas to enliven a railroad underpass. Rendering © BFJ Planning

Above

BFJ Planning staff members gathered for a portrait in the firm’s New York studio (left to right): Planner Eshti Sookram; Senior Planner Mark Freker; Planner Nile Johnson; Principal Sarah Yackel; Associate Principal Noah Levine; Principal Georges Jacquemart; Associate Principal Jonathan Martin; Planner Emily Tolbert; Planner Suzanne Goldberg; Principal Frank Fish; Urbanomics Principal Tina Lund; Senior Planner Christine Jimenez; Planner Lucy Pidcock; Principal Susan Favate; and Associate Principal Thomas Madden. Not Pictured: Associate Silvia Del Fava; Office Manager Françoise Mohamed; and Evan Accardi, an intern. Photograph by Sean Duggan | © Perkins Eastman

Opposite Page

BFJ’s conceptual design for Waverly Place in Madison, NJ, includes ideas to enliven a railroad underpass. Rendering © BFJ Planning

Above

Top Left

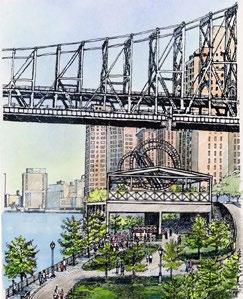

BFJ’s comprehensive plan for the revitalization of the Manhattan side of the Queensboro Bridge called for improved waterfront access and open space connections, more street greenery, and view preservation. Drawing by Paul Buckhurst | © BFJ Planning

Top Right

The firm’s vision plan for the West Side Rail Yards (now known as Hudson Yards) in Manhattan advocated for a residential neighborhood and park facing the Hudson River, with community facilities and office buildings on the city-facing side of the site. Drawing by Paul Buckhurst | © BFJ Planning

Right

Perkins Eastman and BFJ Planning’s collaboration on the Hanoi Capital Master Plan to 2030 produced a land-use plan for the greater Hanoi region with distinct satellite cities and large swaths of green areas for rice plantations and flood-control efforts. Site Plan by Paul Buckhurst | © Perkins Eastman

Another project by the firm involved long-term planning for the Perkins Eastman-led Hanoi Capital Master Plan to 2030 in Vietnam, which Jacquemart, who directs BFJ’s infrastructure work, describes as “a memorable project that provided a unique opportunity to work in a world with different planning rules and modes of travel.” The firm also produced a property assessment of Hartford-Brainard Airport in Hartford, CT, which included development constraints and recommendations, environmental impacts and a remediation plan, and a community engagement plan. And a particularly challenging downtown waterfront plan for Duluth, MN, was ultimately recognized by the American Planning Association’s Minnesota Chapter with a Waterfront Center Outstanding Planning Award.

The firm’s small team approach—and supportive environment—is vital to its success. “We pride ourselves on having a culture that is, first and foremost, collegial,” says Fish, recipient of the New York Planning Federation’s 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award. Yackel echoes his thoughts: “There’s an openness of communication and level of respect given to independent thought here that I truly love. Plus, we’re known for fostering young talent. We like to give staff opportunities to participate in a meaningful way, from presenting work at public workshops to contributing to plan recommendations.”

Associate Principal Thomas Madden, one of the newer members of the team, was drawn to the firm’s inclusive environment and multidisciplinary approach. “We work on amazing projects with incredible clients both small and large, public and private. That flexibility was very appealing,” he says. Favate agrees: “I’m constantly learning and being faced with new challenges. We work on so many different types of projects, and, in the process, do our best to improve the diverse places where we work.”

Office Manager Françoise Mohamed, who has worked for BFJ for nearly a decade, says it best: “I feel like I’m working with family, and I look forward to settling at my desk every morning.” N

Top Hylan Boulevard, the longest commercial road on Staten Island, NY, features natural, cost-effective drainage systems such as bluebelts and bioswales—part of the reconstruction efforts following Hurricane Sandy. Rendering © Perkins Eastman

a unique design.BY TRISH DONNALLY

Cities thrive on a dynamic interplay of economics, politics, and design. They host a rich blend of uses and serve as magnets for talent and tourism. Great cities are engines of innovation; they are never static and always full of surprises—part of their allure for world-class companies and institutions.

“Maintaining a city’s vitality depends, in part, on how well it preserves the past while adapting to and accommodating the future,” says Nick Leahy, co-CEO and executive director of Perkins Eastman. “Promoting the intelligent reuse of existing fabric through sensitive adaptations is central to the firm’s approach to our work with the Simons Foundation in the Ladies’ Mile Historic District [aka the Flatiron District] of Manhattan.”

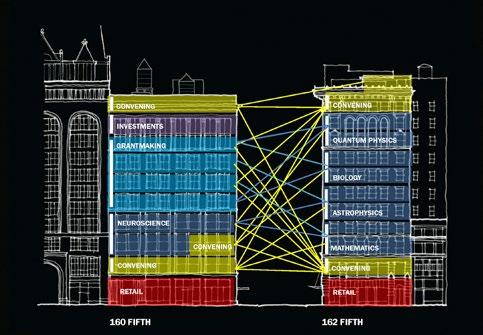

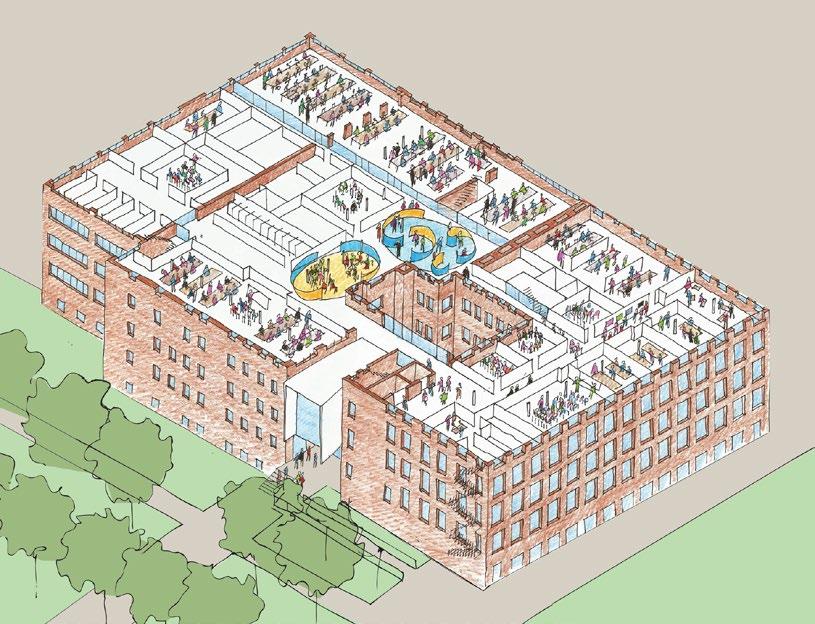

The Simons Foundation is a philanthropic organization founded in 1994 by Jim Simons, a renowned mathematician, and Marilyn Simons, an accomplished economist with expertise in the nonprofit sector. It works to advance frontiers of research in mathematics and the basic sciences through the support of computational scientists and makes grants in several areas, including education and health. In 2016, the foundation, which is headquartered at 160 Fifth Avenue, established the Flatiron Institute at 162 Fifth Avenue. The historic buildings, both constructed at the turn of the 20th century, face one another across West 21st Street.

The foundation and the institute employ a total staff of 500 and host more than 5,000 visiting academics and researchers from around the globe each year. In addition to conducting critical research, the institute serves as an important economic driver and vital nerve center for both the Flatiron District and the city at large. Perkins Eastman master planned, designed, and executed the gut renovation of 162 Fifth Avenue to create a collaborative research facility for the institute, one of several projects the firm has completed for the Simons since the early 1990s. Essential to the client’s research philosophy is the idea that insights and innovations happen when people convene in person. The institute renovation, for example, includes a variety of formal and informal convening spaces, and it is equipped throughout with chalkboard walls for scribbled formulations and discussions.

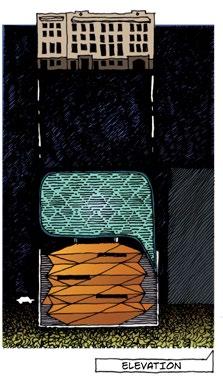

In 2019, with robust activity occurring on both sides of West 21st Street, Jim Simons proposed a skybridge to improve access and increase interaction between the two buildings, while enabling development of the 160 Fifth Avenue rooftop as another convening amenity. Perkins Eastman set about developing concepts to span the street.

The challenges were apparent from the outset: the city’s planning commission rarely approved skybridges (believing they take pedestrians off the sidewalks), and historic district restrictions increased the level of scrutiny. The firm’s solution needed to be unique, contextually appropriate, and able to navigate the revocable consent process, the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), and regulatory approvals.

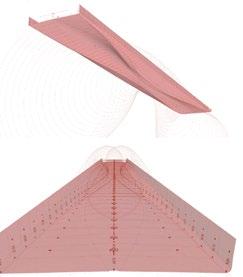

After studying the architectural character of the two buildings, which have very different expressions, and assessing the best place to connect them, the firm proposed a structural glass enclosure—formally precise and visually light. Two options for the bridge deck were explored: folded steel plate and carbon fiber. The latter was selected for its structural and visual lightness, ability to accommodate integrated services within the deck’s depth, and reduced structural impact on the existing buildings.

The next step was to build a team that could make the skybridge concept a reality. Engineer Michael Ludvik is a long-time collaborator with a keen sense of design. The creative thinkers at Derive Engineers were brought on as the mechanical consultant due to their ability to “think outside the catalog.” Façade consultancy Walter P. Moore, TM Light, and fire and life-safety specialist AKF rounded out the group.

Together, the team set out to gauge the city’s appetite for the project. At an initial meeting with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the skybridge was viewed with bewildered enthusiasm—a positive sign, but the project stalled during the pandemic. By 2022, however, efforts to revive the city also sparked renewed interest in the bridge.

When Jim Simons suggested a skybridge to link 160 and 162 Fifth Avenue and address safety and efficiency concerns, he also inspired the vision: a modern, cutting-edge design to reflect the advanced research happening inside these buildings. The result is a sleek glass and carbon fiber structure 135 feet above ground level. The 63-foot-long skybridge will link the shared program and convening spaces currently separated by the noncontiguous nature of the SimonsFlatiron campus.

After studying the differences in architectural styles and structural systems of the two existing edifices, the design team concluded that “the most respectful and elegant connection between the buildings should contrast with their massiveness and be as technologically advanced as construction has progressed today,” says Project Architect Andrés Pastoriza of the Neo-Renaissance 160 Fifth Avenue (1892) and BeauxArts 162 Fifth Avenue (1903) buildings. “We’re trying to dematerialize the bridge as much as possible and to maintain the integrity of the two existing historic buildings.”

Left: The Center for Computational Neuroscience is within the Simons Foundation building at 160 Fifth Avenue; center: diagram showing the web of interactions between 160 and 162 Fifth Avenue and demonstrating the need for a physical connection between the two buildings; below: watercolor illustrating the client’s “light of knowledge” concept.

Photograph by Andrew Rugge | © Perkins Eastman; Diagram © Perkins Eastman; Watercolor by Andrés Pastoriza | © Perkins Eastman

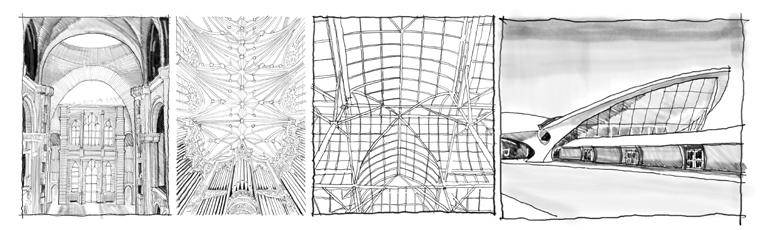

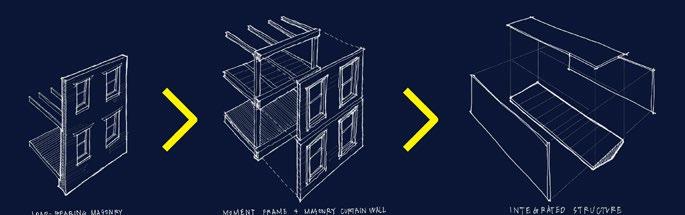

Sketches illustrate the legacy of the architectural expression of structure in and around New York City (left to right): load-bearing masonry and vaults at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine; ribbed stone vaults at St. Patrick’s Cathedral; cast-iron and glass vaults at the New York Botanical Garden Enid A. Haupt Conservatory; and cast-in-place concrete at the TWA Flight Center terminal. Sketches by Nick Leahy | © Perkins Eastman

The team began a journey to prove the design would be an appropriate connection both between the client’s buildings and within the historic district. Working with historic consultants Higgins Quasebarth & Partners (HQ) and planning and development attorneys Kramer Levin, the team crafted an argument for the skybridge, the appropriateness of the design approach, and the reasons why it would not set a precedent for future bridges. HQ noted that the Ladies’ Mile Historic District designation cited the area’s rich mix of architectural styles and technologies, reflecting the latest structural systems of the day. The 22-story Flatiron Building (1902)—the namesake of the institute, one of the city’s earliest steel-framed structures, and one of its first skyscrapers—was a case in point. Also noted was the history of businesses’s growth in the area, which involved connections between buildings, including bridges. Using these findings as a framework, the team studied the district and developed a visual lexicon of the city’s pedestrian bridges.

“By proposing a minimal connection using advanced materials, we created a complementary design that continued the district’s history of embracing advanced technologies,” Leahy says. The proposal also demonstrated that the architectural expression of a structure was a function of the materials it employed, illustrating this with local landmarks such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan and the TWA Flight Center at JFK International Airport in Queens.

In consultation with Kramer Levin and the advocacy group Kasirer, the team worked with various city agencies to build support for the project, emphasizing the Simons Foundation as an important asset for the city. Perkins Eastman’s previous work with the client to increase the presence of ground floor retail and activate sidewalk interactions, which involved designing an entrance to 162 Fifth Avenue on West 21st Street, was also conveyed to alleviate the city’s concerns about losing foot traffic to the skybridge.

LOAD-BEARING MASONRY MASS IN COMPRESSION

MOMENT FRAME AND MASONRY CURTAIN WALL RIGID CONNECTIONS

INTEGRATED STRUCTURE STRENGTH THROUGH LIGHTNESS

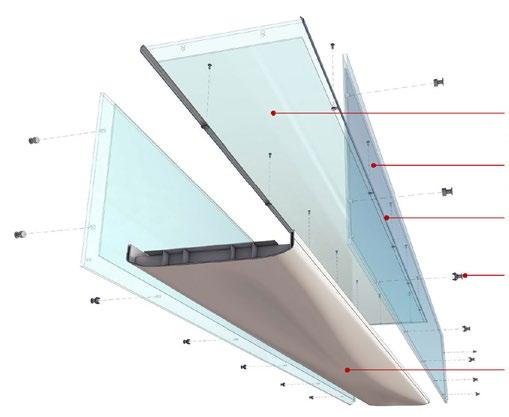

EXPLODED DIAGRAM OF MAJOR SKYBRIDGE COMPONENTS

The skybridge is a unique advanced solution; it pushes the boundaries of materials. The team selected structural glass and carbon fiber, which is lighter than a conventional glass and steel assembly. This decision reduced the need for reinforcement within the existing buildings and eased construction challenges. “Both glass and carbon fiber lend themselves to a prefabricated strategy, which is what is needed to span a busy street in Manhattan and avoid unnecessary delays during installation. The structure can be lifted into place and installed in one day,” Leahy says.

(1) 63-FOOT-LONG TRIPLE LAMINATED STRUCTURAL GLASS ROOF

(2) 63-FOOT-LONG TRIPLE LAMINATED STRUCTURAL GLASS WALLS

STAINLESS STEEL TRIM

STAINLESS STEEL FITTINGS

LIGHTWEIGHT OPTIMIZED CARBON FIBER DECK

While the design of the skybridge is complex, it radiates simplicity. Advances in the use and size of structural glass enable the specification of 63-footlong single sheets of triple-laminated glass, thereby increasing the visual lightness of the bridge. Glass is an extremely strong material, but it’s brittle too. However, when laminated using high-performance interlayers, it is an efficient combined structural and enclosure element. The structural glass offers multiple benefits: the roof’s ceramic frit will help with glare, heat gain, and other energy issues; and a pattern on the laminated interlayers of the wall glazing will alert birds to the skybridge’s presence. Glass will also reduce the skybridge’s impact on sight lines from the street, within the buildings, and from neighboring structures.

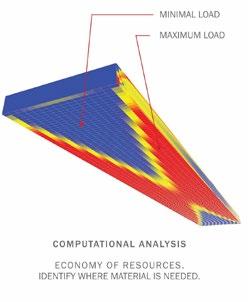

A sequence of diagrams illustrates the concept of structural optimization afforded by carbon fiber and computational analysis, shape, and economy of material.

MINIMUM LOAD

MAXIMUM LOAD

BASE SURFACE STANDARD PROFILE: SIZED FOR MAXIMUM LOAD REDUNDANCY

COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSIS

ECONOMY OF RESOURCES: IDENTIFY WHERE MATERIAL IS NEEDED

OPTIMIZED SHAPE PROFILE SCULPTED FOR PRECISE LOAD EFFICIENCY

GEOMETRY SCRIPT

DEFINING THE OPTIMUM GEOMETRY SCRIPT FOR THE CARBON FIBER DECK

Carbon fiber is extremely strong. It’s also lightweight and easily shaped. It has long been used in transportation and nautical sectors, and more recently in architecture. The carbon fibers and resin are cast in a mold, a process that reflects the use of cast terra-cotta on 162 Fifth Avenue and in the district. Just as the two institutions use computational methods, the latest technology is being used to create the skybridge design. The team developed an optimized structural shape for the carbon fiber deck to address the forces that will be acting on the bridge. Using Rhino

RHINO GEOMETRY

ADVANCED COMPUTATIONAL DESIGN HELPED SHAPE THE DECK

and Grasshopper software, the team customized the geometry of the deck to support the exact load for maximum efficiency. Energy performance was also an important consideration, and the project was modeled and designed to meet local energy codes. The high-efficiency mechanical systems for the fully conditioned bridge interior will be housed in the deck. Aware that the underside of the skybridge would be the most visible element of the project from the street, the team designed soft illumination for the deck to highlight its sculptural contours at night.

Precision is fundamental to the design of this project: structural glass and carbon fiber require it, as does the architectural sensitivity of the historic buildings. A thorough understanding of the geometry of their façades and ornament is necessary to determine how to make precise connections.

The design team used the data from a Lidar survey (light detection and ranging), a remote sensing method that employs lasers to survey an object or surface in three dimensions, to map the façades. The resulting point clouds (collection of data points) helped the team detail the structural connections and architectural intersections between the skybridge and each building.

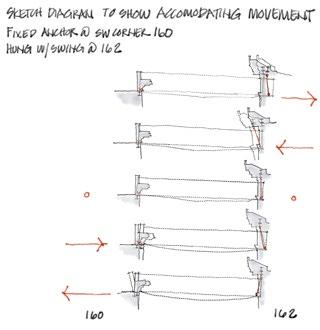

To accommodate movement of the two buildings, the skybridge is fixed at 160 Fifth Avenue and features a flexible connection at 162 Fifth Avenue. Throughout the design process, careful consideration has been given to the installation and construction sequence, which impacts detailing decisions.

At 162 Fifth Avenue, with only inches to spare between the finished floor and the bridge, “We had to make a structural connection that was minimal, so we hung it from the floor above,” Pastoriza explains. “We can then reinforce it from the roof without impacting a lot of the existing structural elements or the façade elements around the opening.” Steel rods hung from brackets on the underside of beams will support the bridge. “It’s a swing that’s receiving the bridge, and it allows for four inches of movement between the two buildings [in case of seismic activity],” he adds.

Simons Foundation Skybridge West 21st Street, New York, NY

Client: Simons Foundation

Owners Rep: Cushman & Wakefield

Program: Pedestrian skybridge

Size: 500 square feet; 63 feet long, 10 feet high, 8 feet, 4 inches wide

Site: 135 feet above West 21st Street (The skybridge will connect at the 11th floor of 162 Fifth Avenue and a proposed 10th floor addition of 160 Fifth Avenue.)

Completion: Expected 2026

Last December, the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the design, marking an especially important milestone in a long engagement with multiple agencies and community organizations that started in 2019. It is the first of many important steps, and the team continues to work together to shepherd the project through the regulatory process in addition to refining the document packages for bid. Next steps include the revocable consent approval process and ULURP, which typically takes up to a year to complete. While there is much to be done before the skybridge is installed, including completion of a rooftop amenity on 160 Fifth Avenue by TPG Architecture, Leahy notes, “The momentum toward bringing this design to fruition and connecting the scientists and researchers of the Simons Foundation and Flatiron Institute is very exciting.” N

Design Team: Nick Leahy, principal in charge; Andrés Pastoriza, project architect; Amra Kulenovic, job captain; Giaa Park, senior designer; Pablo Cabrera Jauregui, Yujin Lee, Maggie Zou; Coco Mong (intern)

Model Builder: Kazimierz Rzezniak

Renderings: Michael Kane

Design Consultants: M. Ludvik Engineering (bridge structure); Derive Engineers (MEP); Walter P. Moore (façade and building maintenance); AKF (fire and life safety); Severud Associates (existing building structure); TM Light (lighting)

Agency and Advisory Consultants: Metropolis Group Inc. (code and expediting); Higgins Quasebarth & Partners, LLC (historic preservation); Kramer Levin (zoning attorney); Kasirer (lobbyist)

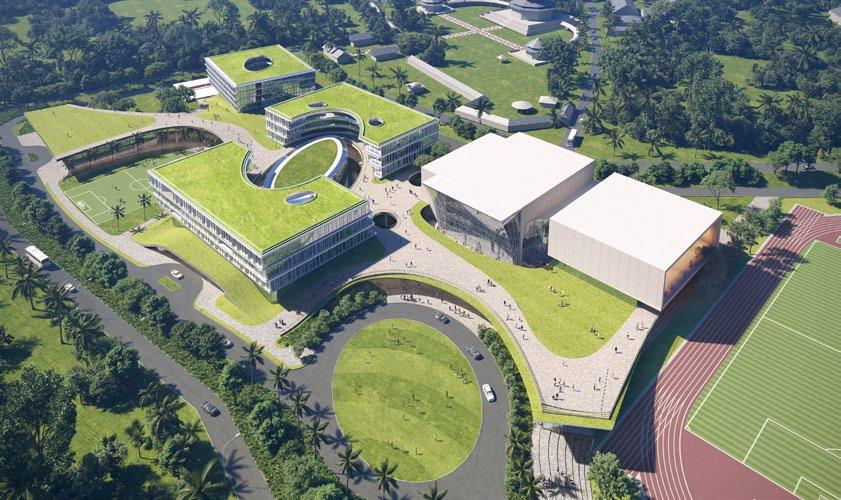

Treating what ails them, medical institutions are being transformed from insular islands into collegial communities.BY JENNIFER SERGENT

At their best, top health-science and academic medical campuses perform like small towns, accommodating “thousands of daily stakeholders with diverse activities, needs, and destinations,” says Jeffrey Brand, a Perkins Eastman executive director and principal. To create opportunities for productive interactions among their stakeholders, the firm is helping major institutions—such as the University of Miami, University of California San Francisco, and University of Kuwait—replace an outmoded tradition of placing medical care, academics, and research in silos, separate and removed from each other. As advances in each of these three areas become ever more sophisticated and integrated, it’s important to recognize that “one person’s science in a lab may be the medical solution for a patient. That’s why bringing people together and letting them talk about what they are doing is essential for discovery both in and outside the lab setting,” says Brand, who co-leads the firm’s healthcare practice with Principal Jason Harper.

Perkins Eastman has established a brain trust of experts to guide health and science institutions as they chart their next generation of growth. Perhaps more than any other business or academic sector, medical master planning often requires contemplating growth not only on a single campus but also across multiple sites with additional networks of outpatient facilities and nonclinical support buildings. Such efforts demand layers of expertise that blend healthcare and highereducation design with urban planning, transportation, mixed-use development, and hospitality. “It’s about putting these different components together to create a different outcome,” says Perkins Eastman Executive Director and Principal Hilary Kinder Bertsch. The firm has completed many medical-campus master plans for large institutions in the past, and it continues to work on and pursue more.

Each campus master plan must respond to an institution’s culture, size, location, and budget, but above all, Brand says, “We want these folks who are at the highest level of academia to collide and talk about their research, help the learners, and try and invent new protocols for medicine. The master plans we’re designing now are meant to funnel these folks together.” They must support the goals of the clinical, educational, and research population, in addition to their overlaying operations and leadership, and the community in which they all can thrive. It is a response to what clients and stakeholders have expressed to the healthcare team. “They are requesting places for respite, engagement, social interaction, work collaborations, stimulation, equitable access to care, ease of moving around a campus, and other meaningful, town-like features,” Brand says.

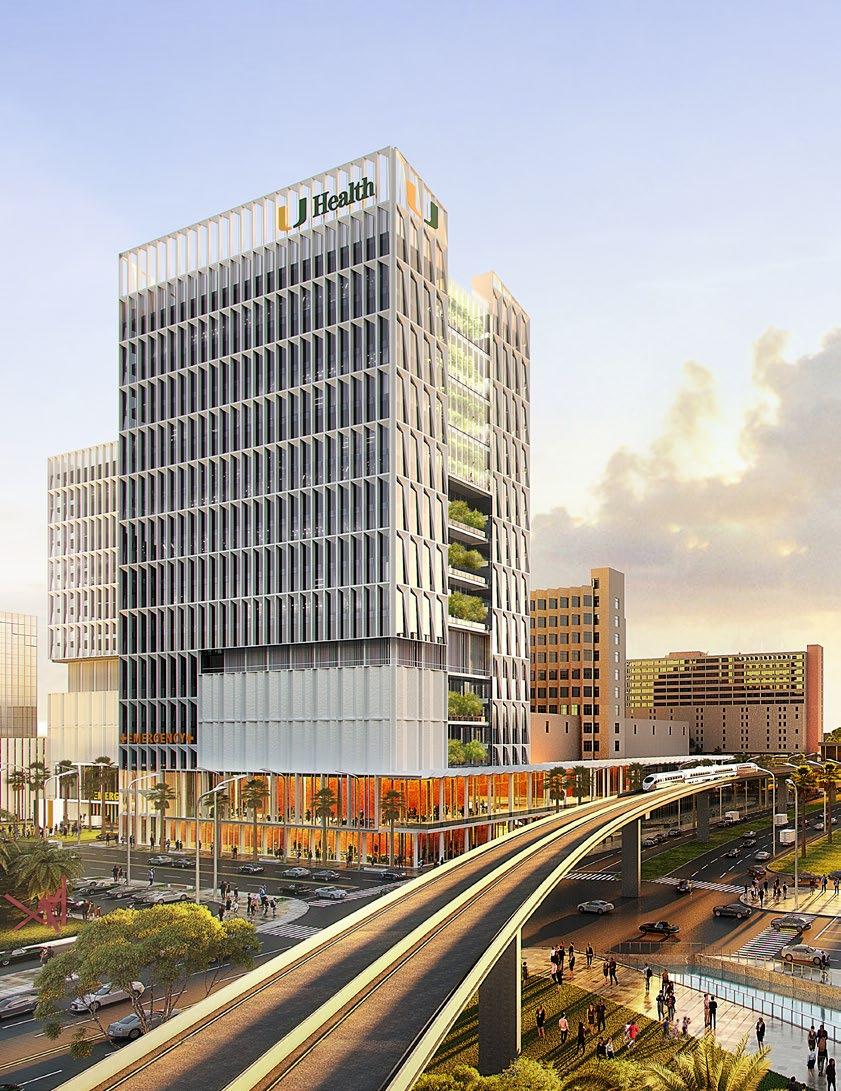

That is the goal at the University of Miami, which hired Perkins Eastman to rethink how its medical campus could use existing buildings and design new ones across more than 100 acres of its downtown setting in addition to satellite outpatient centers up to 30 miles away. The downtown plan carves quadrangles and greens into the university’s dense urban fabric to create a more

Previous Pages

The master plan for the University of Miami’s downtown medical campus calls for direct links to public transit, making it easier and more equitable for people to access its facilities.

Opposite Page

The University of Miami medical campus master plan (top) carves quadrangles and promenades into its dense urban location. A rendering (below) illustrates a new quadrangle that unites both existing and new buildings.

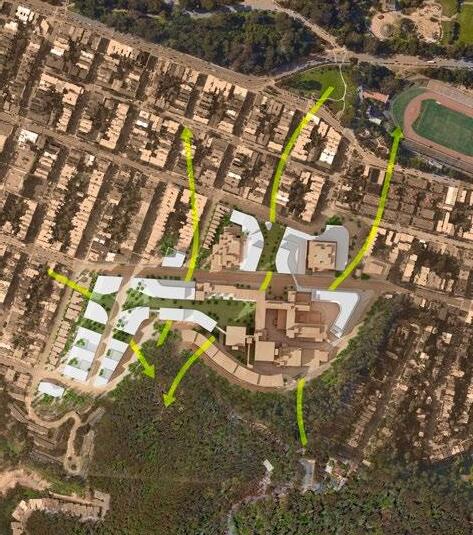

Left and Below

The “Park to Peak” master plan for the University of California San Francisco’s Parnassus Heights medical campus illustrates the pedestrian flows between Golden Gate Park to the north and Mount Sutro to the south. A rendering shows the terraced landscape along one of the pathways that traverses the campus as it steps up toward Mount Sutro.

All Images and Renderings © Perkins Eastman

welcoming, garden-like environment for pedestrians. It also creates a precinct of research, clinical, and academic buildings, all connected within a five-minute walk along pleasing pathways lined with plantings, benches, shops, and cafés. Significantly, the plan places the medical district directly on the city’s transit and bus lines, providing “equitable access to care, so it’s not all about the car anymore,” Brand says.

Seeking to foster a similarly vital environment, the firm has crafted a 30-year comprehensive plan for the modernization and expansion of the University of California San Francisco’s Parnassus Heights campus. The “Park to Peak” plan, which commenced in 2021, calls for a new “front door” to the campus at an existing transit stop, transforming a forbidding wall of parking garages into a welcoming streetscape that opens views toward Golden Gate Park to the north. It also calls for a series of terraces and walkways that guide people through campus buildings to Parnassus Avenue on the southern border and onto the adjacent parkland surrounding the peak of Mount Sutro. The plan’s guidelines inform the design approach of a new 700-bed hospital along with research and academic buildings and proposed new campus housing, as well as the adaptive reuse of many existing buildings. The intent, says Principal Vaughan Davies, is to blur the lines between the campus, the neighborhood, and the natural bounty that embraces them. “Everything on the ground level had to reflect this ‘Park to Peak’ ethos with a park-like environment that makes you realize you’re in this very special place in San Francisco,” Davies says. The guidelines for the new buildings also call for expansive,

publicly accessible roof terraces that enjoy broad views of Mount Sutro and San Francisco’s skyline. “It’s transforming the campus with new hospital and research buildings and a huge interface with the community to get it right,” Brand says, noting the effect will resemble an Italian hill town, with the buildings gradually stepped up toward Mount Sutro via placemaking plazas and courtyards.

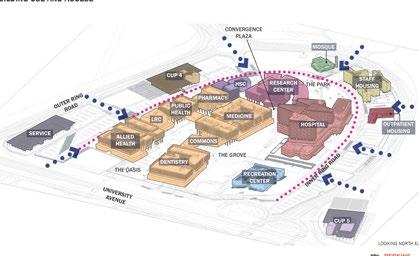

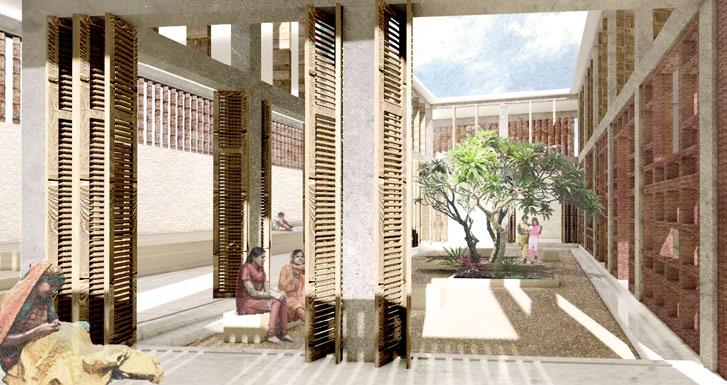

The firm’s experts are now applying their ideas to the new University of Kuwait campus being developed on the outskirts of Kuwait City—a rare opportunity to integrate medical, research, and academic buildings from scratch. Key to the plan is a pedestrian network that speaks to the area’s extreme climate, where summer temperatures can exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit. “We

conceptualized the entire campus around a wadi, a dry riverbed. The buildings all interface with it, with parking either underground or on the periphery,” Brand says. It is an entirely walkable environment, he adds, “where everything flows together as a campus” along its metaphorical riverbed. The Oasis anchors the campus’s five medical colleges, student center, and learning resource center. The research center, hospital, and recreation center branch off to frame an additional green space called The Grove.

To help people avoid the heat, the design calls for an air-conditioned underground concourse, referred to as the garden level, where students, staff, and visitors can access the campus’s main buildings. The concourse features glass-enclosed sunken gardens, which bring natural light into this subterranean space. It also features a Commons with a café, retail outlets, banks, and other amenities. Additionally, a third-floor “rampart” offers both indoor and outdoor walkways between the university’s five medical-college buildings, giving students and professors access to meeting spaces, gathering areas, and the buildings’ green roofs with broad vistas. “It’s all about creating paths to connect people to places—a bench, a small meeting room, or a

larger conference area,” Co-Managing Principal Jason Abbey says. “That’s how we enrich and enliven the connective tissue of the campus.”

As healthcare delivery models have evolved from single, isolated structures to networks that spread out across cities and regions, Perkins Eastman has leveraged its diverse, multidisciplinary talent and global studio network to achieve the best outcomes for its clients. “These master plans recognize a crucial factor that goes beyond healthcare, research, and academics,” Bertsch says. “It’s about the quality of experience. People have choices, and they’re demanding that the environment meets the level of the services that the institution delivers.” It is a complex challenge whose benefits carry a multiplier effect, Brand notes, because repositioning on a large scale tends to bring everything else along with it. “If you define the campus characteristics that make it a good neighbor, then the neighborhood around you also rises to the occasion beyond your campus perimeter. You’ve now made this integrated community that’s even better.” N

Opposite Page

Kuwait University Hospital’s main student entry (above) is a nodal point along an underground concourse, which connects more than a dozen buildings and allows students, faculty, and staff to traverse the new health-sciences campus protected from the heat in a setting with plentiful daylight. It also abuts a sunken garden. A diagram (below) identifies the campus buildings and uses.

Below

A rendering of the University of Kuwait’s health-sciences campus illustrates the central Grove connecting its complex of medical colleges to the left and the main hospital at right.

All Images and Renderings © Perkins Eastman

Carefully defined sustainable design goals counter the pitfalls of often vaguely defined terms.BY TANYA EAGLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BROOKE SULLIVAN

Good design is sustainable design. It adds social, economic, and environmental value to projects and communities, and it informs every aspect of Perkins Eastman’s work. The language of sustainability’s triple bottom line is critical to setting and achieving clear project goals. It is also continuously evolving. Many regulations, trends, and market standards have arisen out of the imperative to address climate change and create healthier communities, and the associated terminology is often unclear and ill-defined. This guide aims to bring a common understanding to several significant—and often misunderstood or misused—topics and terms. The goal of an aligned terminology is to more readily advance design performance and create better places for people and the planet.

Simply put, net zero energy (NZE) is the ability of a project—a single building or an entire campus—to produce as much energy as it consumes on an annual basis. At Perkins Eastman, the NZE approach prioritizes reducing a project’s energy consumption through a deliberate design process that focuses first on reducing the energy needed by including all stakeholders and considering all energy uses. Energy use intensity (EUI) measures the total energy consumed by a building per square foot over the course of one year. Once the EUI has been lowered as much as possible, the remaining energy consumed is offset by renewable energy (typically photovoltaics) onsite when feasible.

Achieving NZE is often viewed as a technical or systems challenge. But the efficiency of a building’s design significantly impacts NZE goal achievement. Within an NZE framework, Perkins Eastman first employs passive design principles suitable for both current and future local climate conditions when shaping, sizing, and detailing a building. Once passive opportunities have been maximized, the next step is to include high-performance, all-electric systems to avoid the burning of fossil fuels and allow for a true offset of consumption to production. NZE is part of an encompassing approach to holistic wellness, and the wellness of people and planet should always be the ultimate goal.

Like NZE, carbon neutral is an equation looking for a net-zero balance. Carbon neutrality requires absorbing and/or offsetting (through the purchase of offset credits that reduce greenhouse gas emissions) as much carbon from the atmosphere as is emitted. Since carbon emissions from human activities are driving global warming and climate change, the architectural profession has an imperative to work toward carbon-neutral or even carbon-positive outcomes that actively reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

As with an NZE approach, design plays a major role in achieving a carbon-neutral building. Design decisions impact both operational carbon (the carbon a building emits through energy usage across its lifetime) and embodied carbon (the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the life cycle of building materials, from extraction through manufacturing, transportation, installation, and end-of-life disposal, recycling, or reuse opportunities). Passive strategies and renewable technologies can reduce operational carbon, and reducing the quantity of new materials and selecting materials based on their life cycle can reduce embodied carbon.

However, designing carbon-neutral buildings is only one step toward achieving a carbon-neutral society. The larger goal is a cross-industry global challenge that involves transitioning transportation infrastructure and utility grids away from fossil fuels and toward green solutions; it also requires the reinvention of material pipelines. Today, carbon neutrality is not possible without carbon offsets, but with collaboration across industries, pulling carbon out of infrastructure systems altogether is possible.

Resilience is the enhanced capacity of buildings, systems, and communities to respond and adapt to, as well as recover from, adverse events such as natural disasters, climate change, and human-caused hazards both current and future. A resilient design maintains functionality and minimizes negative impacts; it contributes to the ability of broader socioecological systems to cope with change.

In design, the term resiliency is often used in reference to disaster response preparations. But resilience encompasses much more: the durability of built structures and the strength and vitality of their social, economic, and environmental context. A truly resilient design serves as a community asset in the face of varied challenges such as power and utility interruptions, extreme weather events, or changing populations.

The first step in designing for resilience is to proactively assess natural disaster risks and potential human-induced hazards, such as a utility disruption due to error or deliberate act, civil unrest, or technological failure. A resilient design process implements hazard-specific measures and prioritizes passive strategies to extend project functionality even when HVAC and other systems are down. Examples include a school that accommodates community use for emergencies or regularly occurring events, a hospital that remains functional after an earthquake, offices that can be repurposed into residential units, and renovations tailored to changing climate conditions.

In the natural world, diversity is essential to the health of ecosystems. Similarly, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) are critical to the long-term sustainability of every community’s economic, social, and environmental fabric. A commitment to diverse, equitable, and inclusive practices and policies must be embedded in a firm’s culture and design process to create vibrant spaces and places that truly support people and communities. There is much to learn from DE&I efforts both within and beyond the design world. For example, Gallaudet University, which educates deaf and hard of hearing students, is rethinking how the word “inclusion” is expressed in American Sign Language. The university believes that the sign, which involves one hand attempting to squeeze into a small hole formed by the other hand, suggests that one must adapt to fit a certain mold to be included. Its proposed alternative is a new sign that depicts one hand freely placing fingers onto the open palm of the other hand, representing the true meaning of inclusion. To achieve better design outcomes, a sustainable process deliberately invites all stakeholders to meaningfully contribute.

A circular economy is a model that minimizes waste, maintains and extends the value of products and materials, and avoids extracting new resources. In a linear economy, buildings and materials are designed for one use, and significant waste is generated at the end of a project or material’s lifespan. Architects and designers contribute to a circular economy by designing for disassembly, deconstruction, reuse, future renovations, and adaptability for future uses.

The best way to move closer to a circular economy is to prioritize renovation and reuse projects that maintain buildings and materials of value and preserve the community fabric. Waste reduction can be as straightforward as limiting the number of new materials used in a project. For example, the recent design of Perkins Eastman’s Pittsburgh office streamlined materials by eliminating wall base and unnecessary bulkheads to reduce the quantity of materials used and enable more time to vet the final materials.

Indoor environmental quality (IEQ) refers to the conditions inside a building, such as air quality, daylight, acoustics, and thermal comfort. It encompasses how a building makes its occupants feel, and whether it positively or negatively contributes to their well-being and productivity. IEQ is fundamental to the firm’s “Human by Design” principles. Design impacts occupant experience and health.

With sleeves rolled up, the firm’s teams regularly go into the field to evaluate IEQ measures from pre-design to post-occupancy, and they use software tools throughout the design process to model IEQ parameters. The models and measurements are paired with on-site post-occupancy evaluations to assess the achievement of wellness and performance goals quantitatively and qualitatively, and the lessons of these data-based assessments are applied to future projects.

It is critical to holistically evaluate and specify materials for their impact on the health and well-being of people, communities, and the planet. “Healthier materials” is a term often associated with the impacts of hazardous chemicals in building materials, but it encompasses a wider range of impacts. Perkins Eastman is a signatory of the AIA Architecture & Design Materials Pledge, which commits the firm to prioritizing materials that foster human health, social health and equity, ecosystem health, climate health, and a circular economy throughout their life cycle.

To assess a material’s impact, Perkins Eastman balances a variety of considerations and studies product disclosures and certifications:

• Climate health: seek products that reduce or even sequester carbon emissions.

• Human health: avoid products that include hazardous substances and materials that negatively impact the health of occupants and communities throughout their life cycles.

• Ecosystem health: give preference to materials that support natural water, air, and biological cycles.

• Circular economy: reuse buildings, select materials that can be repurposed, and minimize waste.

• Social health and equity: look at the operations and supply chains of the manufacturers to ensure that they honor human rights.

The goal is to improve the quality of the air people breathe and the materials they touch, protect the health of communities affected by supply chains, and be responsible stewards of the environment. Every material specified should have a net-positive benefit throughout its life cycle.

Biophilia refers to humankind’s innate biological connection to nature: human health is inherently connected to the natural world. The term biophilia is rooted in psychology and biology, and built environment applications have been developed by research scientists and design practitioners. Biophilic design strategies are employed to improve cognitive function and performance as well as physiological and psychological health and well-being.

Biophilic design is more nuanced and layered than the inclusion of green walls or views of nature. The research-based biophilic strategies outlined in Terrapin Bright Green’s “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment” are a good guide.¹ The environmental consultancy organizes its patterns into three categories:

• “Nature in the Space” refers to the presence of natural elements (plants, water, breezes, scents, sounds) in a space; it seeks to address the five senses.

• “Natural Analogues” include forms, patterns, textures, materials, and other sensory information that mimics and evokes connections with nature; it is often organized into a spatial hierarchy in which elements are highlighted or presented in multiple levels of visual detail.

• “Nature of the Space” reflects relationships and spatial compositions found in nature that support the human desire to feel safe, overlook large expanses, experience risk, or discover new places; for example, humans seek places of prospect to survey an expansive area or refuge to withdraw into a protected space.

Perkins Eastman combines these strategies to create places to live and work that engage the senses, support joy, and facilitate wellness. N

1. Browning, W.D., Ryan, C.O., & Clancy, J.O. (2014). 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. New York: Terrapin Bright Green, LLC. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/14-patterns/

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (Milkweed Editions, 2015)

Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things by William McDonough and Michael Braungart (North Point Press, 2002)

Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming edited by Paul Hawken (Penguin Books, 2017)

Healthy Buildings: How Indoor Spaces Can Make You Sick—or Keep You Well by Joseph G. Allen and John D. Macomber (Harvard University Press, 2022)

The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design by Lance Hosey (Island Press, 2012)

Every material selection impacts people and the planet; Perkins Eastman works to upend harmful, outdated practices.BY JENNICA DEELY

It is no secret that every element of a building—the foundation, exterior envelope, structural system, mechanical systems, and interior finishes—has an outsized effect on indoor environmental quality and the natural environment. Making informed material selections is both increasingly complex and critically important. “Buildings account for at least 39 percent of energy-related global carbon emissions on an annual basis. At least one quarter of these emissions results from embodied carbon, or the carbon emissions associated with building materials and construction,” according to the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute. And that’s only the carbon impact. There is much more to consider when making material choices.

Efforts to reimagine the design profession’s specification of materials have a long way to go, but progress is being made. Perkins Eastman is digging deep into its own material research and selection processes and helping to inform larger industry initiatives. Among those leading the way are Heather Jauregui, director of sustainability; Tanya Eagle, leader of sustainability standards; Christine M. Vöhringer, a sustainability specialist; and Jane Hallinan, the interior design liaison for material health.

In Eagle’s role outlining sustainability standards, she explores the many elements that make a material healthier. “The big picture is so important, and carbon is a huge component,” Eagle says. “But to get the whole story, you have to ask other questions as well: Are you focusing on the impact to human health? Are you focusing on issues of equity in the supply chain? What about materials’ impact on ecosystems?”

Identifying and specifying holistically healthier materials and products is a challenging process. A plethora of product labels denoting “healthy” or “green” attributes, differing standards across third-party rating systems, a lack of transparency in the manufacturing process, and competing or contradictory certifications and data make material specification a time-consuming endeavor. “If you don’t know enough about how those certificates or labels have been vetted, or if they’ve been vetted at all, then it’s really hard to make an informed decision,” Jauregui says.

Eagle is participating in groundbreaking efforts to simplify both the selection and codification of healthier materials through her work with industry organizations and initiatives.

In 2016, Eagle joined the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) materials working group and contributed to the creation of the institute’s Architecture & Design Materials Pledge and Healthier Materials Protocol—its official position, language, and guidelines. She is now co-chair of the AIA Materials Pledge Working Group, which recently released new reporting benchmarks for the industry to track progress related to material selection and specification.

Her involvement with the AIA has influenced Eagle’s engagement with mindful Materials (mM), a nonprofit focused on aligning the building industry around a common language for holistic material sustainability. As a Catalyst Member of its AEC Forum, Eagle, along with Hallinan and architects and designers from other firms, is working to coordinate language and standards. The “mM Portal,” a free online database of healthier products launched in 2023, employs the Common Materials Framework to enable users to search by sustainability impacts, as well as by certification or standard. The comprehensive database aims to streamline the sourcing process and foster a united and consistent materials message within the industry.

projects aiming for net-zero energy and LEED and WELL Platinum certification. With school projects, Vöhringer says, “We are targeting quality materials that meet sustainability and wellness standards but are also incredibly durable and can be sourced in large quantities.” Collaborating with school leadership, the teams draw from an established collection of qualified products.

To drive change in the building industry, “we must address the problems from a holistic perspective. To do that, alignment and collaboration are imperative.”

— Annie Bevan, CEO of mindful Materials

Along these lines, Vöhringer is working to standardize commonly used materials for Perkins Eastman’s other practice areas, so designers don’t have to search high and low for the appropriately vetted product from one project to the next. To streamline the process, Vöhringer is using the Boston studio as a test case for the firm-wide material library protocol, which dictates that materials must either be entered in the mM Portal or have a minimum threshold of sustainability criteria. Moving forward, material libraries in the firm’s 24 studios aim to only store materials that support Perkins Eastman’s commitment to the AIA’s materials pledge.

Previous Page and Left

The wide variety of sustainable materials on the market, such as natural cork, recycled terrazzo, reclaimed wood, products approved by the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), and biodegradable and PFAS-free (free of “forever chemicals”) textiles, makes sourcing easier and more effective than in the past.

Palettes prepared and photographed by Colletta Conner of ForrestPerkins (previous pages) and Jane Hallinan (opposite page)| © Perkins Eastman

Spreading this message among clients is equally important. “There is so much information out there, and I can talk with them all day about the many details that make a great product, but what’s most important is getting the client to understand why one material choice is better than another,” Hallinan says. “To champion it, we have to make healthy, sustainable materials part of the design narrative.”

This comes into play, for instance, in Perkins Eastman’s K-12 Education practice. The firm has set the standard for holistic design in public schools, with multiple

Annie Bevan, CEO of mM, underscores the vast amount of research pointing to the harmful effect materials— from the beginning to end of their life cycles—can have on humans, climate, ecosystems, and social health and equity. To drive change in the building industry, she says, “we must address the problems from a holistic perspective. To do that, alignment and collaboration are imperative.”

“As architects and designers,” Jauregui says, “we have a lot of influence on both the health of the planet and the health and well-being of the occupants who are using our buildings and spaces.” The time is now to upend the building industry’s approach to materials. N

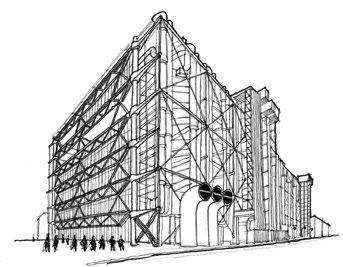

Win or lose, design competitions are fertile ground for testing bold ideas and sharpening essential skills.

BY NICK LEAHY Perkins Eastman Co-CEO and Executive Director

“This is going to make some noise,” remarked French President Georges Pompidou on seeing the competition-winning drawings for a new arts and culture center in the historic Les Halles neighborhood of Paris. While highly controversial in 1971, the design looked to the future and set a mark in the chronicle of architecture. It also launched the careers of Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, who went on to become giants of the architectural world. More than 50 years on, the Centre Pompidou is a beloved landmark of modern architecture. It reimagined what a museum could be and prompted a new approach to the materiality and expression of structure in architecture.

The design competition has long played a key role in the tradition and practice of architecture, and it is an essential ingredient in a thriving design-led culture. Competition-winning designs such as the Pompidou can change the course of architecture or reimagine city skylines, and there are many other influential examples: Filippo Brunelleschi’s Duomo (1436), Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace (1851), the Gustave Eiffel-led team’s Eiffel Tower (1889), Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House (1973), and Zaha Hadid’s The Peak (1982–83) among them. Besting the competition in a highly publicized contest can also be a springboard to international recognition and new commissions. Much like Piano and Rogers,

Perkins Eastman’s Wanshan Lake Eco-Tech City competition-winning design (above) aims to be a magnet for the tech community in Wuxi, China. A half-century earlier, an international contest for Paris’s Centre Pompidou (below) put a different kind of high-tech architecture on the map. Wanshan Rendering © ATCHAIN; Sketch by Nick Leahy | © Perkins Eastman

Above

The “Archipelago of Learning” won the competition for the pre-K-12 Canadian International School in Thailand, though another firm received the commission. Local conditions inspired an “eco-canopy” that connects learning “islets” and shelters open spaces. Rendering © Perkins Eastman

Right

Perkins Eastman, one of the finalists selected by the organizers of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, developed master plan concepts for the riverfront site. Site Plan © Perkins Eastman

Opposite Page Above

The competition-winning “Moonrise” scheme for Wuxi Symphony Hall will be a hub of creative energy for Wuxi, China. Rendering Courtesy Perkins Eastman

Opposite Page Below

Two competitions held some 400 years apart produced groundbreaking structural feats: the 15th-century, monumentally scaled Duomo (left) of the Florence Cathedral; and the prefabricated cast-iron-and-glass Crystal Palace (right) in 19th-century London. Sketches by Nick Leahy | © Perkins Eastman

Utzon and Hadid were unknown on the global stage up and until they, too, won notable competitions.

While such examples are both instructive and inspiring, competitions offer something even more valuable: important opportunities to develop design ideas and skills. Design is a process of continual learning and refinement. It’s honed by practicing our craft and taking on challenges that expand our creativity—competitions among them. At Perkins Eastman, we aspire to “make some noise” of our own. Yes, we must balance design aspiration and commercial pragmatism, but design competitions are important opportunities to experiment and test boundaries. They teach critical thinking, decision-making, and problem solving, and they sharpen presentation and storytelling skills.

To capture the imagination of a jury or client, each competition submission pushes us to distill a concept to its essence—an art unto itself. Such lessons are learned

quickly in the competition environment, with its tight deadlines and pressure to stand apart from competitors. In this setting, there is a strong impetus to think differently, challenge conventional wisdom, and refresh the lens through which we evaluate our ideas. At Perkins Eastman, the competition format speaks to our culture of innovation, emphasis on learning and growing, and better outcomes for clients and communities. It is part of the R&D DNA of our firm and the profession.

Many of Perkins Eastman’s prominent commissions are the result of design competitions. For the firm, competitions present opportunities to break into new markets, regions, or building types. They can enhance our design reputation on the world stage too. Wuxi Symphony Hall (currently under construction) is our first performing arts facility in China, while Wanshan Lake Eco-Tech City (won in 2023) expands our mixed-use portfolio of large master plans and raises our profile, as we beat out several well-known international design

Above

An exterior plaza with tracery sunshades is part of a confidential master plan competition entry.

Rendering Courtesy Perkins Eastman

Below

The competition-winning designs for the Eiffel Tower, Sydney Opera House, and The Peak Leisure Club (unbuilt) in Hong Kong set forth influential ideas about form and structure.

Sketches by Nick Leahy | © Perkins Eastman