At Perkins Eastman, we strive to impact people’s lives in positive ways, an effort at the heart of our Human by Design ethos. Our Summer 2025 issue of The Narrative reflects how we make this happen. In “Walk the Talk,” our story about the Just label, a measure of transparency (akin to a nutritional food label) we earned last year, we reveal where we stand in terms of DE&I and recognize where we can still grow. We are one of only eight large AEC firms in the world to achieve this designation. In “Kicking the Habit,” we calculate our progress toward reaching the goals of the 2030 Challenge. With fewer than five years on the clock, we must go full bore, and we implore the AEC industry to do the same—now. In “Roundtable: Accessible Cities,” a new feature we’re introducing with this issue, our PEople reimagine obstacles—the nationwide housing shortage and climate change, among others—as opportunities for new thinking with far-reaching effects.

“Project Scrapbook: Learning by Design” unveils an exceptional new high school in Alexandria, VA, that is a model of equity. “Aging with Dignity” explores how the silver tsunami requires a new way of thinking when it comes to housing. Intergenerational developments, affordable senior living environments, and sustainable spaces promise to be key. The building of academic libraries on university campuses surged following World War II, especially in the brutalist style. However, in 2025, clients are embracing biophilic design and the many positive benefits of natural light. See how our firm has applied its expertise in adaptive reuse to transform dark, midcentury libraries into light-filled learning centers in “Here Comes the Sun.” And while Perkins Eastman uses advanced software to create designs daily, little is more compelling than simple paper and cardboard models to communicate the potential of urban design projects. Read “Model Matters” to learn how a handmade model can clarify concepts during a presentation. In “Studio Spotlight: Los Angeles,” we celebrate a creative and energetic group of professionals who deftly design healthcare, urban planning, and arts and culture projects among their dozen practice areas.

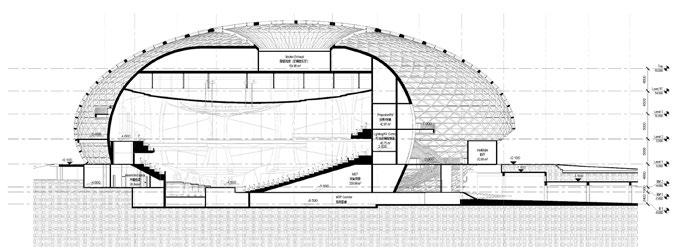

“Wuxi Wonderland” provides a rare, behind-the-scenes glimpse into a scale model erected to perfect the acoustics of Wuxi Symphony Hall, the epicenter of the Wuxi Cultural Arts Center in Wuxi, China, due to be completed later this year. And don’t miss “Take 5,” where you’ll meet five fascinating designers, including a third-generation, Ecuadorian architect, as well as one whose work is inspired by poets’ “wonderful economy of words.”

Happy reading,

The Communications Team

To view The Narrative online, including previous issues, go to https://perkinseastmanthenarrative.com/summer2025/

LET US HEAR FROM YOU

Please send questions, comments, or story ideas to: humanbydesign@perkinseastman com

© 2025 Perkins Eastman. All Rights Reserved.

EDITOR IN CHIEF

TRISH DONNALLY

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

ABBY BUSSEL

CONTRIBUTORS

EMILY BAMFORD

JENNICA DEELY

HEATHER JAUREGUI

PAMELA MOSHER

TANIA PHILLIPS

JENNIFER SERGENT

EDITORIAL DESIGNER

BROOKE SULLIVAN

GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITOR

KIM RADER

PHOTO EDITOR

SARAH MECHLING

WEB DEVELOPER NICK PUGLIESI

On the Cover

The cover, designed by Brooke Sullivan, is based on a model built to test the acoustics of Wuxi Symphony Hall (page 52). Inspired by The Beatles’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, the design incorporates portraits of contributors and other PEople.

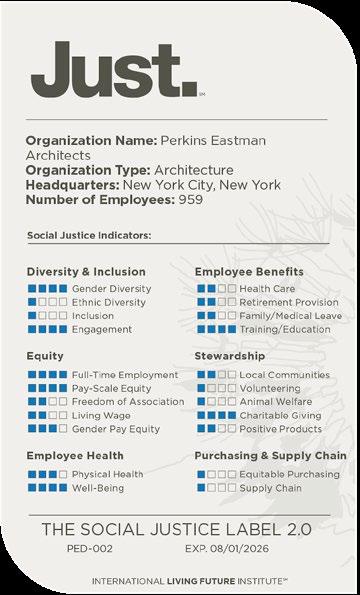

Opposite page, top: The Just label life-cycle

Data Collection start the process create policies Turn Into Action Prioritize action items improve resubmit (every 2 years)

Walk the Talk | 04

The Just public disclosure tool helps the practice live up to its ethos

Aging with Dignity | 06

Housing for older adults goes beyond the basics

Studio Spotlight: Los Angeles | 10

Cross-disciplinary collaboration seeds creativity

Kicking the Habit | 16

A clarion call rallies designers to prioritize carbon reduction

Model Matters | 22

Paper and cardboard remain agile tools for urban design projects

Here Comes the Sun | 30

Light-filled renovations reinvigorate aging academic libraries

Project Scrapbook: Learning by Design | 36

Community connections elevate a new high school

Roundtable: Accessible Cities | 44

Voices from across the practice grapple with opportunities and obstacles in the metropolis

Gallery: Wuxi Wonderland | 52

Acousticians fine-tune a model-sized symphony hall

Take 5: Conversations with PEople | 56

Five Perkins Eastman designers muse on life and work

The International Living Future Institute’s voluntary public disclosure tool helps Perkins Eastman live up to its Human by Design ethos.

BY JENNICA DEELY

Corporate websites are awash in language about DEI commitments, but measurable, meaningful results require more than clever wordsmithery. This is where the Just label comes into play. In 2024, Perkins Eastman Architects, specifically the practice’s 17 US studios, became one of only eight large AEC firms in the world to achieve the Just label designation. The label, administered by the nonprofit International Living Future Institute, known as Living Future, is a transparency framework for “social justice indicators”—akin to a nutrition label—that enables the practice to establish, review, and refine its policies on diversity, health, supply chain, and more.

“What we really wanted to understand was, ‘Are we actually fulfilling the commitments that we’re talking about out loud in our day-to-day practices?’ ”

—EMILY PIERSON-BROWN Associate Principal, PEople Culture Manager

“This milestone is not the end goal but a significant step on our journey,” says Koray Aysin, Perkins Eastman’s leader of corporate sustainability. The effort began in 2021 as a pilot project in the Washington, DC, studio and expanded nationwide after that location earned the label in 2022. PEople Culture Manager Emily Pierson-Brown led the nationwide effort to gather qualitative data, distributing engagement surveys and visiting every US studio. “What we really wanted to understand was, ‘Are we actually fulfilling the commitments that we’re talking about out loud in our day-to-day practices?’” she says.

The data collection process led to significant updates to Perkins Eastman’s employee handbook, incorporating enhanced policies on benefits, compensation, diversity, and environmental quality. The label, displayed on the Living Future and Perkins Eastman websites, requires public transparency. Increasingly, requests for proposals require transparency, too, as potential clients seek information about policies on DEI, health,

and sustainability. “The Just label simplifies our response when pursuing projects,” says Nick Leahy, co-CEO and executive director.

While the label acknowledges existing policies, it also highlights areas for growth. For example, Perkins Eastman’s Ethnic Diversity, Inclusion, and Equitable Purchasing indicators currently meet baseline standards, but more progress is needed. Improvements, now underway, will be evaluated during the label’s next update in 2026. At the same time, measures that perform at the label’s maximum level, such as Gender Diversity, continue to be a focus for the firm.

Securing the label for the practice’s US studios “reflects our belief that transparency and continuous improvement are essential to creating a positive impact,” Leahy says. In addition to updating its current label, Perkins Eastman is committed to expanding its Just efforts globally, one studio at a time, and embedding its values-driven culture deeper into its design philosophy. N

• Does your firm have diversity and inclusion policies?

• Does your firm have any external sustainability certifications (DJSI, GRI, GBB, Green C, Certified B Corporation, Green America, Green Plus)?

• Does your firm have any external ratings, certifications, or awards related to diversity, inclusion, or employee engagement such as GPTW or Just?

• Does your company produce an annual corporate responsibility report?

Creative and sustainable independent living solutions for older people go beyond the basics, contributing to wellness, longevity, and happiness.

BY TANIA PHILLIPS

Aging has its joys and challenges, with sky-high housing costs a major factor. Inclusive communities that offer care and comfort to seniors within a sustainable ecosystem are especially important for those navigating their retirement years with limited financial resources. While the substantial costs associated with assisted living settings for those needing mobility and cognitive support remain a hurdle, creative design solutions can broaden independent living options for people at both low- and middleincome levels.

The supply of affordable environments that enable independence and promote wellness must keep pace with an aging global population. According to the World Health Organization, “Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double from 12 to 22 percent.” Additionally, by 2050, 80 percent of older people will be living in low- and middleincome countries.

“Demand is surging for senior housing as America’s population ages, but supply continues to lag,” writes Michele Lerner in a recent Urban Land article. “Supply and demand dynamics don’t tell the whole story, though: senior housing development tends to thrive at the upper end, where seniors with means can afford to live in a continuing care retirement community. It also thrives at the lower end, where government subsidies support housing and healthcare for seniors with fewer resources.”

Zooming into demographics in India and the United States—the world’s first and third most populous countries, respectively, offers more evidence of the rapidly growing need for affordable senior housing. A 2023 report on aging in India, published by the International Institute for Population Sciences and United Nations Population Fund, projects the country’s population of people aged 80-plus will grow at a rate of some 279 percent between 2022 and 2050 with a “predominance of widowed and highly dependent very old women.” The Administration for Community Living, a division of the US Department of Health and Human Services, paints an equally vivid picture in its 2023 Profile of Older Americans: in

2022, people aged 65 and older represented 17.3 percent of the population—a number expected to grow to 22 percent by 2040— while the median income of older people was $29,740 in 2022.

Affordability and quality of life must go hand in hand. Sensitivity to the location of housing options, for example, would benefit millions of older adults in the coming years. “Many senior living and care options have made it necessary for older people to move away from their neighborhoods. Land and development costs, zoning, and other barriers have made it difficult to create good senior living within existing communities. A large portion of today’s seniors would prefer to live in intergenerational communities near or within their own neighborhoods but in a more supportive living environment,” says Perkins Eastman Chair Brad Perkins. “As a result, we have seen a slow but steady increase in senior developments within cities and established communities, which create virtual intergenerational communities.”

How does intergenerational living help the forgotten older adults in the middle, those who can neither afford luxury senior living nor qualify for Medicaid? “Intergenerational living in senior environments helps combat social isolation and shifts perceptions of aging,” says Principal JinHwa Paradowicz, who co-led a 2024 task force on intergenerational living that surveyed 490 people, including residents and family members, designers, operators, and owners. According to the survey, which was a joint effort of SAGE, AIA Design for Aging Knowledge Community, and The Center for Health Design, 95 percent of respondents believe intergenerational living should be a priority in senior housing. “Unlike age-segregated communities, this model enables seniors to age within a diverse community, offering more affordable options for them,” Paradowicz says.

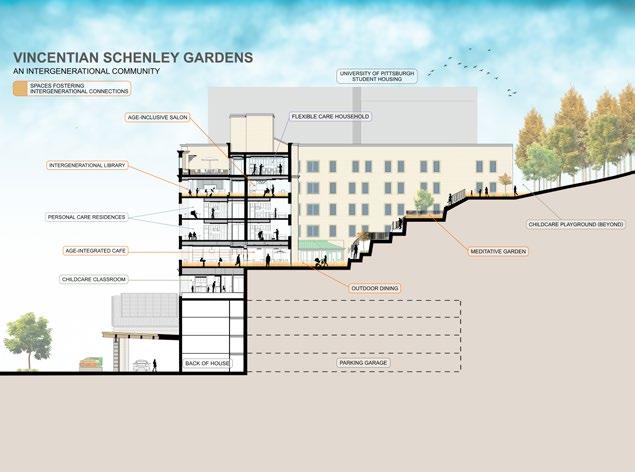

Intergenerational living developments accommodate older adults and younger people to support and strengthen relationships across generations. For example, Vincentian Schenley Gardens,

1. A library is among the spaces designed to foster connections across generations at the Vincentian Schenley Gardens in Pittsburgh, PA. 2. The intergenerational community will transform a licensed personal care building into an inclusive environment for people of all ages and abilities.

a Perkins Eastman project in Pittsburgh, PA, is an intergenerational community with student apartments incorporated into the design alongside assisted living apartments for older adults. Students pay below market-rate rent in exchange for providing services such as leading exercise or cooking classes or serving meals to older residents within the community. Schenley Gardens also includes childcare, so older adults can interact with children on a programmed basis—such as reading books to them—and hear peals of laughter and experience other spontaneous joys in return. Senior care can incorporate intergenerational living in an integrated model, such as Vincentian does, or it can operate in a dedicated tower within a larger multigenerational setting. This enables the operator to provide the necessary services, including meals, health checks, and fitness and care specific to older adults.

When intergenerational living is integrated into mixed-use developments designed with safe and accessible connectivity, seniors have access to a variety of culinary and cultural experiences, and other amenities, without loading the cost for those activities onto their monthly services. Choice in Aging, in partnership with Satellite Affordable Housing Associates, commissioned Perkins Eastman to create a multigenerational

community on its campus in Pleasant Hill, CA. This empathetic model aims to welcome people, regardless of age, gender, or socioeconomic status, with a preschool program, adult guest care, affordable housing, and other programming, all in a less costly environment.

“In India, Thailand, Singapore, and other countries where intergenerational living is the traditional lifestyle, we are beginning to see the development of high-quality, intergenerational communities with senior living and care being developed in conjunction with housing for all other age groups,” Perkins says.

With the exception of assisted living offerings, often termed “high care services” in the international market, independent senior living units are typically owned, unlike in the United States, where renting is more common. The success of independent living solutions for middle- and lower-income seniors lies in the economy of scale and the design of smaller, more compact units. This market typically sees one- and two-bedroom units ranging from 460 to 800 square feet. A third scenario is a one-bedroom unit with

a den, which provides an economical alternative for a second, short-term sleeping arrangement.

In fact, the most effective affordable senior living solutions prioritize adaptability, allowing residents to remain in their homes for as long as possible, unless they experience severe cognitive or mobility challenges. Compact units with open floor plans offer flexibility for personalization and increase opportunities for natural light and airflow; such units are particularly beneficial in hot, humid climates, where they can improve indoor environmental quality and overall comfort. Cross ventilation via large, operable windows is an effective passive design strategy, decreasing reliance on mechanical ventilation while also reducing the need for artificial lighting.

Spaces for shared amenities are expensive to operate and directly impact the monthly costs to the resident. Designing flexible spaces, with the appropriate lighting, acoustics, and finishes, can serve multiple interests and programs and remain in use throughout the day. A combination of indoor and sheltered outdoor amenity spaces provides residents with additional benefits: exposure to fresh air and sunlight.

Investing in a variety of affordable and sustainable wellness programs while leveraging economies of scale can reduce the cost per resident. Proactive preventative care, for example, supports a healthy lifestyle and reduces the risk of costly medical interventions in the future. Similarly, volunteer programs in nonessential services such as gardening, library management, or event planning can help promote an active lifestyle and a sense of purpose and community while reducing labor costs.

Opportunities to support senior wellness can be leveraged through both design and operational strategies. For example, affordable senior housing developments typically face site constraints, limiting opportunities to incorporate outdoor amenities that promote wellness. In such cases, a podium roof can serve as a car-free outdoor area. Roof gardens offer safe and easy access to green spaces and expansive views of the surroundings, particularly in urban settings. Balconies provide another opportunity to connect residents to fresh air and views. With safe edge conditions and seamless indoor-outdoor transitions, they offer immediate access to an exterior space. Residents also gain the benefits of morning sunlight, when the rays are not too hot, particularly in tropical climates, with proper building and balcony orientation.

Simple sustainable strategies can also offset operating costs: rainwater for non-potable uses, solar heat collection, and recycled greywater for drip irrigation. Durable materials for the architectural shell and core appropriate to the local climate can minimize maintenance and repair costs over time. Shared transportation can help lower costs for residents and reduce the community’s carbon footprint.

The modular, Phius-certified La Mora Senior Apartments, a project designed by Perkins Eastman, is an example. This Passive House development with 60 affordable apartments in Yonkers, NY, is oriented to provide residents with abundant natural light, and it includes units for the hearing impaired, a multipurpose community room, a landscaped courtyard, and a roof deck.

Designing sustainable and flexible solutions empowers older adults to thrive in their later years within affordable, comfortable, and stimulating environments. N

BY JENNICA DEELY

As dynamic as the metropolis it calls home, the Perkins Eastman Los Angeles (LA) studio thrives on projects that foster cross-disciplinary collaboration. “It’s about different people and approaches coming together,” says Co-Managing Principal Derek Hamilton, referring to the cooperative spirit that has shaped the studio’s trajectory—one marked by steady growth and strategic mergers and acquisitions.

Perkins Eastman’s 2011 union with Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn expanded its expertise in urban design and planning, while the 2015 acquisition of LBL Architects deepened its healthcare credentials. Together, this joining of talent set the stage for the LA studio’s establishment and rapid evolution into a powerhouse of design and planning that same year. The 2021 merger with Pfeiffer Partners Architects (its celebrated roots dating to the founding of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates in New York in 1967 and the establishment of HHPA’s Los Angeles office in 1987) further broadened the firm’s portfolio, adding performing arts, higher education, libraries, historic preservation, and civic design to its repertoire.

“I appreciate the dynamic of how we’re now working together,” says Principal Vaughan Davies, an original member of the LA studio. The studio is designing projects for senior living, healthcare, and higher education clients, among others, and leading and collaborating on urban design and planning projects in Southern California, Vancouver, Seattle, Oakland, and further afield in Nashville and 1

Founded: 2015

Staff: 62

Practitioners: architects, designers, interior designers, planners, project managers, urban designers

Completed Projects: 1,000-plus (includes work completed by Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn, LBL Architects, and Pfeiffer Partners Architects prior to merging with Perkins Eastman)

Recent Awards: 2024 Engineering News Record Southern California Best Renovation/ Restoration: University of Southern California Dick Wolf Drama Center; 2024 AIA New York State, Urban Planning and Design: Nashville Imagine East Bank Plan; 2022 United States Institute for Theatre Technology (USITT) Merit Award: Gonzaga University Myrtle Woldson Performing Arts Center; Healthcare Design 2021 Showcase Award of Merit: MarinHealth Medical Center; 2019 AIA/ALA Library Building Award: Colorado College Tutt Library; 2018 AIA/LA Design Awards Presidential Honoree 25-year Award: Los Angeles Public Library Rehabilitation and Tom Bradley Wing; 2018 AIA Richmond Design Merit Award: Science Museum of Richmond; 2017 USITT Merit Award: Chapman University Musco Center for the Arts

the Pacific Northwest. “We want our people to feel they are part of one unified West Coast studio and the greater Perkins Eastman family,” he adds. This approach allows the LA studio to take on complex challenges and deliver transformative results in a wide range of practice areas.

One such project is the Reconnecting Pasadena vision concept plan to repurpose a 50-acre freeway stub in the heart of the city’s downtown. The LA and Oakland studios are leading this historically significant revitalization effort and benefiting from the expertise of colleagues based in Perkins Eastman’s New York, Pittsburgh, and Washington, DC, studios.

Another advantage of the LA studio’s cross-disciplinary emphasis is the opportunity for staff members to broaden their experience. Senior Associate Jim Sarratori has spent much of his career working on higher education, renovation, and cultural projects. With the Pfeiffer merger, however, he has recently taken on the role of project architect for a large senior living project, Livelle Mulholland life plan community in nearby Woodland Hills. The studio’s expertise in urban and campus planning has informed the project’s “Main Street” and extensive outdoor amenities, reflecting Perkins Eastman’s dedication to creating vibrant environments that enhance well-being and support aging in place. “By virtue of its new approach, this project is bringing a lot of different practice areas together,” Sarratori says.

Adaptive reuse projects also benefit from multiple perspectives. The recently completed University of Southern California Dick Wolf Drama Center, for example, occupies and expands a 1931 church in a National Register Historic District. The vibrant new hub for education and performance underscores the studio’s

expertise in arts and culture, higher education, and adaptive reuse. “It’s all about convergence—a historic building with a major arts component to it, and it’s also adaptive reuse and certified LEED Platinum,” says Principal and Executive Director Stephanie Kingsnorth.

Associate Principal Shehani Fernando came to Perkins Eastman in 2019, bringing a wealth of California-specific healthcare industry expertise to the LA studio. As the principal in charge and lead medical planner for the Outpatient Pavilion and Ambulatory Surgery Center at the Olive View-UCLA Medical Center campus, she serves as an advocate for person-centered healing environments that are also operationally efficient. Fernando is a trusted advisor on her projects and with the LA team. “I love being able to educate clients and mentor staff,” she says.

Fostering a supportive and creative studio culture is vital to successful project delivery, says Cydney Anderson, a senior associate. “This emphasis on creating space for human connection aligns seamlessly with Perkins Eastman’s Human by Design ethos, which prioritizes our humanity as a firm, as individuals, and within the communities we serve,” she adds.

In addition to project design reviews and pinup sessions, notes Hera Brunel, a senior associate, happy hours and community volunteer events provide opportunities for staff members to express themselves and get to know one another. By welcoming new staff members and practices into the fold, the LA studio tackles design challenges with creativity, empathy, and focus, advancing its broader mission to positively impact people’s lives.

5

1. Building and site improvements at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center to foster a campus-wide integrated approach to treatment. 2, 3. The USC Dick Wolf Drama Center transformation and expansion of a 1931 church within a National Register Historic District. 4. The Museum of Riverside renovation and addition with a state-of-the-art gallery, accessible entrance, rooftop terrace, and event spaces for community engagement. 5, 6. Livelle Mulholland, an 18.75-acre life plan community in Woodland Hills, CA, with a robust program of outdoor activities on its “Main Street” and walkable campus.

A clarion call rallies designers to prioritize carbon reduction.

BY HEATHER JAUREGUI

Is anyone else alarmed by how close we are to the year 2030, or is it just me? Eleven years ago, Perkins Eastman committed to the 2030 Challenge, which called for all new buildings and major renovations to be designed to be carbon neutral by or before the year 2030. To reach its goal, the challenge proposed simple steps that ratcheted up percentage reductions from the baselines every few years. Good in theory, the process has been challenging in practice, as we (and the rest of the AEC industry) have started to plateau around the 50 percent reduction line, and we can’t seem to shake it.

So, how are we going to meet our commitment with fewer than five years to go, especially when we are swimming upstream with the federal government’s aggressive rollback of its climate commitments?

In the early aughts, Architecture 2030 was established as a nonprofit research organization in response to the climate emergency. Knowing the projected growth in global building stock required in the coming decades, and the role the built environment plays in carbon emissions (42 percent of annual global CO2 emissions, or more), Architecture 2030 challenged the AEC industry to reduce carbon emissions

and mitigate exceedance of the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold in 2006. A few years later, the 2030 Challenge was adopted by the AIA, which created the 2030 Commitment, inviting architecture firms to sign on and transparently report their progress on an annual basis.

Today, more than 1,350 firms are signatories of the commitment, and 490 of them are reporting data, but the average predicted energy use intensity (pEUI) reduction is only 50 percent from the 2003 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) baseline—a benchmark allowing projects to compare against a national average by building typology. According to Architecture 2030’s challenge, we should have achieved an 80 percent reduction by 2023 and a 90 percent reduction this year. Well, actually, Architecture 2030 revised its initial target, arguing that carbon-neutrality should have been achieved by 2021, a year now in the rearview mirror. If more evidence of urgency is needed, the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report shows that, even in the lowest emissions scenarios, there is a 50 percent likelihood of exceeding the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold between 2030 and 2035. Drastic changes are needed—now.

When Perkins Eastman signed onto the commitment in 2014, we had no in-house, practice-wide sustainability support. The

1. Improved insulation at roof and exterior walls adds to thermal performance of building envelope.

2. New high-performance, triple-paned glazing improves performance of building envelope and provides comfort.

3. Energy-efficient HVAC system: electrified heat recovery units and direct-outside air system minimize duct work and pipe sizes.

4. Reuse existing structural components to reduce new steel and concrete elements.

following year, we built a team and rolled out a reporting process for 2030 because we needed to know where we were before we could begin to make reductions. We established energy modeling guidance documents for project teams—and started to introduce training. For a firm our size (939 PEople), it was challenging to gather the information needed to assess every project, and it took us years to get there, but by 2019, we were reporting close to 100 percent of our portfolio. In 2020, we created a 10-year plan to meet our 2030 goals, with an initial focus on ramping up energy modeling. Building code updates are starting to drive up the bottom, but not nearly as quickly as needed to meet the challenge. If all our projects are conducting energy modeling across our firm, we know higher energy reduction is more easily achievable.

So where are we? Our 2023 dataset hit a 48.97 percent pEUI reduction from the 2003 CBECS baseline, plateauing over the previous four years. However, we have made strides in increasing our energy modeling, with 49 percent of our whole-building projects providing modeling data. This has helped: more of our projects met the 2030 Challenge target in 2023 than ever in the past, with 37 of our 299 projects meeting or exceeding the current challenge target for the year, and 12 of them targeting net zero energy.

Educational projects are leading the 2030 charge, meeting the challenge at an exponential rate within both our K-12 Education and College + University practice areas. Some of this can be attributed to changing jurisdictional regulations, such as the Greener Government Buildings Amendment Act of 2022 in Washington, DC, which requires net zero for all publicly funded buildings (including schools), and the updated stretch code in Massachusetts that sets thermal energy and Passive House-level requirements. However, before these more aggressive jurisdictional regulations came into play, we were already seeing progress among our education clients; sustainability has become deeply connected to their missions, and many of them have developed climate commitments either individually (higher education institutions) or as part of

their community commitments (public school districts). Certainly the school building typology lends itself very neatly to achieving these goals as well, with oftentimes low energy demands paired with larger roof expanses and nearby fields to accommodate renewable technology, but another factor is the evolving cultural component in our studios. The more experience our teams gain in delivering high-performance projects, the more it becomes embedded in their design thinking and processes regardless of market sector, client goals, or jurisdictional requirements.

Energy modeling, when done well, is starting to provide more valuable input for our teams at the right time in the process, and we have found the most successful energy modeling plan pairs rapid in-house energy modeling with more skilled or extensive out-of-house modeling conducted by consultants. Even in our developer-driven project typologies, we have seen mindsets changing. Some of this can be attributed to the increased

“When vision aligns with action, the power to change the world lies within the hands of those who design it.”

—ED

MAZRIA Founder, Architecture 2030

availability of funding and incentives in recent years for the green transition, specifically through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, essentially making it cost neutral or cost negative to invest in higher performance systems. Nothing spurs change in a capitalist society more than money.

We can and should celebrate and learn from our successes, but we are not in this for a participation trophy. We are at the point where we need to catapult forward. This year, we are embedding new layers into our design processes to drive change, and we intend to be agile in identifying successes and failures along the way. We are requiring project teams to conduct an energy model on all building-scale projects. By not accepting code compliance as our minimum, we gain a better picture of where we stand as a firm and the remaining progress we need to make, but more importantly, we will arm our designers with valuable data to inform their design decisions. Moving forward, we are looking at other requirements

to layer into our design processes, such as drafting up a carbonneutral option from day one and looking at the envelope and system selections as a combined unit to break down the cost barrier associated with high performance. With each new layer in our processes, we are fostering a cultural shift—one in which we lead our clients to carbon neutrality, because it is our responsibility as the experts in the room to do so.

While we are at it, we also need to stop glorifying glass boxes. They are the opposite of good design. Newsflash: our feet do not need a view, our eyes do, and the most important glass for daylighting is at the ceiling, where it can be drawn deeper inside. Rooting our definition of good design in basic passive design principles should be a priority for the global AEC industry. Passive design (and a reasonable window-to-wall ratio) is the key to unlocking high-performance, cost-effective solutions that create better quality indoor environments for all.

The time for the simple steps outlined in the 2030 Challenge has come and gone. We cannot afford to plateau, and we certainly cannot afford to relinquish our climate action efforts. As proposed by architect Doug Farr of Farr Associates during the Phius Passive Building Summit at Greenbuild 2024, we need to kick the carbon habit as a global community faster than our long goodbye to cigarettes (starting in the 1980s), if we want to have any hope of reining in our spiraling climate disaster.

We have very nearly exceeded the global temperature rise threshold and are already experiencing the impacts of climate change—increasingly severe and frequent wildfires, landslides,

hurricanes, flooding, and more. It is no longer a question of if we will exceed the threshold; it is a question of by how much, and can we stop the bleeding? We cannot continue to politicize this issue. It is negatively affecting the daily lives of countless people around the world. It is a livelihood issue, an economic issue, and a life-or-death issue.

However, the new administration in Washington is taking significant steps backward, which means the private sector must step up, as we’ve done in the past. The America Is All In initiative is a great example of like-minded, forward-thinking companies confronting climate change as the public sector retreats. Meeting our 2030 commitment is critically important. Even as climate deniers are

sowing uncertainty in the technology needed to replace fossil fuels, we have been consistently designing NZE buildings left and right. Years ago, when the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency added Passive House into its incentives, it found there was a slight cost premium in the first two years, but by the third year the higher performing buildings were coming in cheaper per square foot than conventional construction. Just because the federal incentives disappear, doesn’t mean we are going to design low-performing buildings. As outlined in a recent CleanTechnica article highlighting the growth of solar energy, the green economy will continue to move ahead regardless of the political landscape. Private sector firms, including our practice, must take the lead. Perkins Eastman’s Human by Design ethos compels us to support

and repair a healthy interdependence between people and planet, because design matters and we play an important role.

If the architectural community continues to separate sustainability from design—as something that can be selected (or not selected) by the client—we are never going to reach our 2030 goal. We need to stop asking for permission to integrate sustainability. We need to just do it, regardless of client, project typology, budget, or schedule. No excuses. As Ed Mazria, founder of Architecture 2030, so aptly states in his recent Architectural Record article, “when vision aligns with action, the power to change the world lies within the hands of those who design it.” That’s us—and it’s time to change the world. N

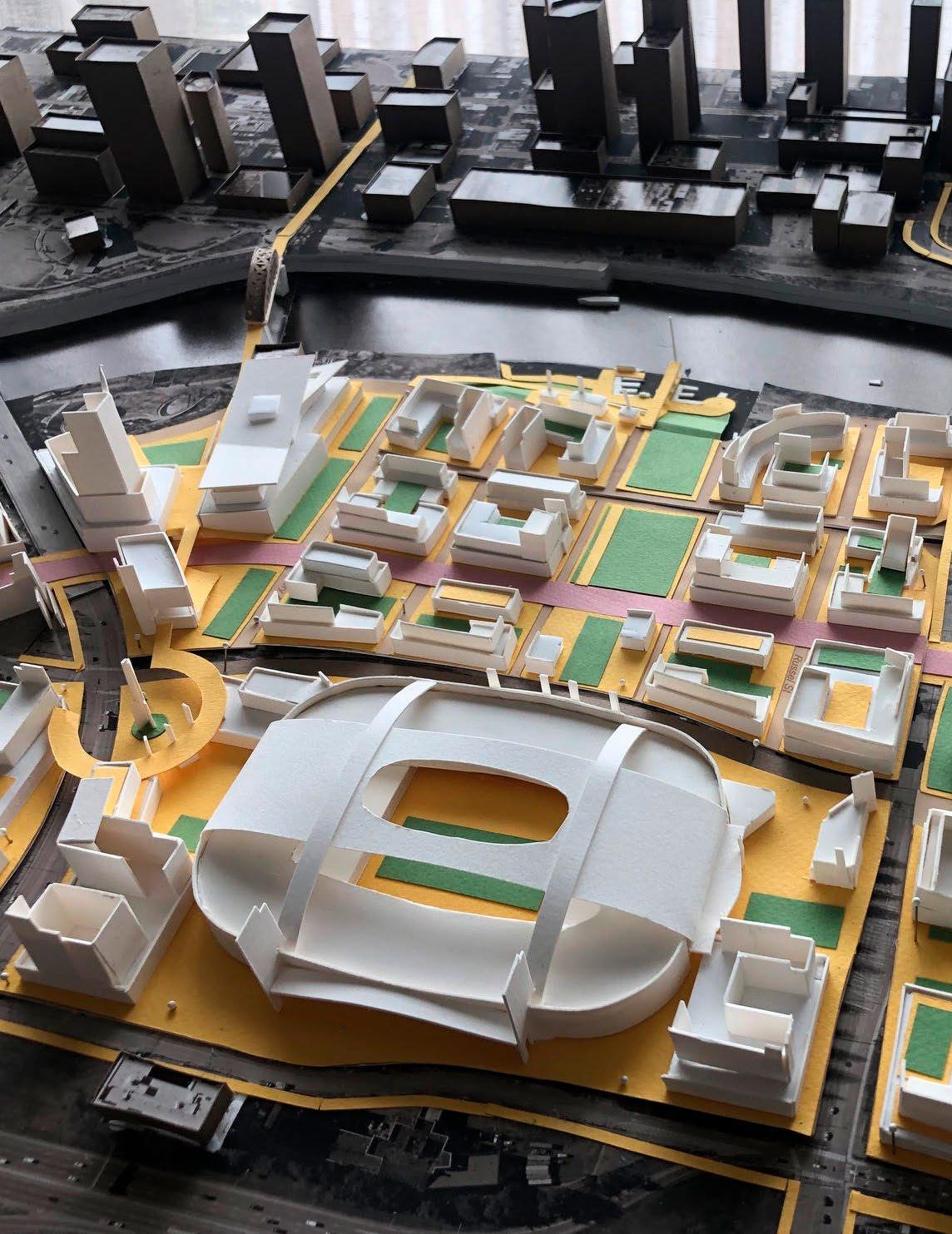

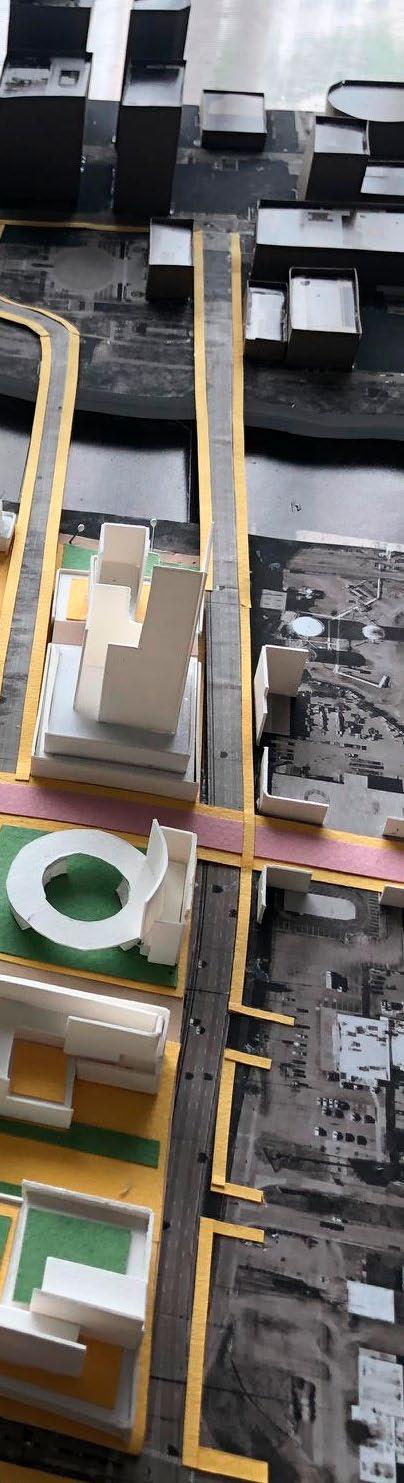

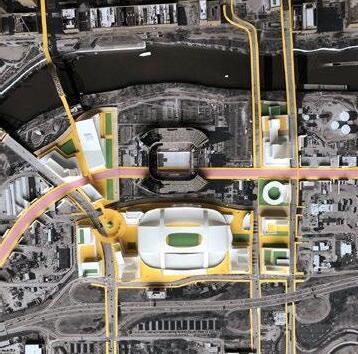

In an age of advanced computer graphics, paper and cardboard models remain remarkably agile tools for urban design projects.

BY JENNIFER SERGENT

“We’re co-creating solutions with citizens to shift decision-making from the top down to having more grassroots involvement.”

—KATE HOWE Project Manager, Reconnecting Pasadena

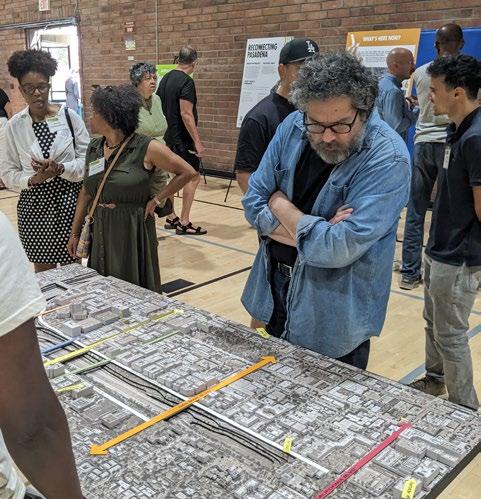

he end point of State Route 710 that bisects the city of Pasadena, CA, is known locally as “the ditch,” because the 50-acre strip of road lies 30 feet below the city’s street grid—and the life of the community. But that’s soon to change. The state relinquished this never-completed highway section to Pasadena in 2022, and Perkins Eastman is guiding an ambitious vision concept plan to reconnect a city where a large number of businesses and residents, including many living on low incomes as well as people of color, were displaced through eminent domain in the 1970s.

To imagine a new future for the site, the project team has been building cardboard study models atop aerial photographs of the existing city grid. They are using a kit of interchangeable parts to experiment with different types of building structures, urban block types, and green spaces that can fill the ditch. “It’s been a freeway for so long, I think it’s really ingrained in

people’s cognitive map of the place,” says Lowell Morin, a Perkins Eastman urban planner and architect. Without the use of models, he explains, “They couldn’t envision something else being there.”

In an era of increasingly slick digital visualizations and simulations, physical models continue to be exceptionally effective for large-scale urban design projects involving vast swaths of a city. “The study models help decisionmakers and the public understand the scale of the site, and it brings them into the design process,” says Kate Howe, project manager of the Reconnecting Pasadena consultant team. Howe, alongside the Perkins Eastman design team, has led many presentations to Pasadena city officials, staff, and the public over the past year. “The tactility of the models attracts people,” Howe says. “We’re co-creating solutions with citizens to shift decision-making from the top down to having more grassroots involvement.”

1. Colored construction paper defines the public realm surrounding a mixed-use development planned for the East Bank of Nashville’s Cumberland River, transforming the area into an extension of the city’s downtown.

2. When the new stadium is completed in 2027, the existing facility will be removed, making way for new developments, open space, and a central boulevard.

3. The new, pedestrian-focused neighborhood will lead to a waterfront promenade and piers.

erkins Eastman’s planning and urban design practice has also guided the city of Nashville as it redevelops a 308-acre industrial area along the East Bank of the Cumberland River. The project aims to convert the desolate area around the Tennessee Titans’ football stadium into a thriving, mixed-use community that will connect with existing residential neighborhoods and extend the downtown, which sits across the river. Practice leaders Vaughan Davies and Eric Fang created a model to help then Mayor John Cooper and his staff visualize the new landscape where the existing stadium will be taken down and a new one built further back from the river. Amid a stadium and other buildings made of cardboard, colored pieces of construction paper represented green space flowing toward the waterfront and a new boulevard that traverses the site.

“We won his approval right away. The meeting was a success because the mayor was able to see the change implemented immediately.”

—VAUGHAN DAVIES

Co-Principal in Charge, East Bank, Nashville

During one review session, Cooper had an idea for repositioning the open space, so Davies cut the paper with scissors and reassembled it on the spot. “We won his approval right away. The meeting was a success because the mayor was able to see the change implemented immediately,” he says. Even in their rough state, models have the power to grab the attention of business and political leaders who’ve seen it all, Fang notes. “These days, everyone is so inundated with digital media, it’s all the more important to have something that is tangible and that you can interact with directly.” 2 3

“It was an eye-opener for the client and the consultant team to see the actual conditions. Nobody understood the scale of the elevation change without the model.”

—VIJO CHERIAN

lanners and developers are also using models to figure out how a new development can nestle into a thicket of urban infrastructure in New York City. Perkins Eastman is in the early design stages for Fordham Landing North, a 1.5-mile strip of Harlem River waterfront in the Bronx that will become home to a mixed-use neighborhood of office, residential, and retail—a project similar in size to Perkins Eastman’s marquee project, The Wharf in Washington, DC.

The development of the northern end of the Bronx site needs to contend with a 40-foot change in grade between existing highways and a new waterfront boulevard, which will have to rise up and over railroad tracks to meet those arteries. “It was an eye-opener for the client and the consultant team to see the actual conditions. Nobody understood the scale of the elevation change without the model,” says Vijo Cherian, the project’s urban designer and architect. The model will help inform the development as it goes through multiple levels of city, state, and federal review.

While renderings can be used to illustrate certain angles or portions of large-scale, mixed-use developments, models can provide critically important site context. Davies says, “There’s a sense of immediacy and accessibility from the observer point of view—to really get to know the model and understand it and see [the whole project] the way they want to see it, from multiple angles—rather than an audited single view from a rendering.”

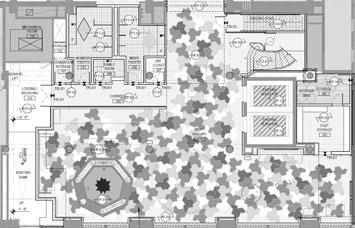

Walking into the model shop at Perkins Eastman’s New York headquarters is like entering a miniature construction site. A large central table fills much of the space where model builder Kazimierz Rzezniak assembles everything from sprawling developments such as The Berkley Riverfront district in Kansas City, MO, to the smallest details such as a bookcase design for a university library. On this day, the main level of a museum was taking shape on Rzezniak’s table. Multiple versions of a central stair were lying about, and the design team for the new Manhattan location of the National Museum of Mathematics (known as MoMath) was pondering which version would successfully twist up and around a ceiling-mounted sculpture planned for the space.

“It’s a fixed dimension that we need to design around,” says Pablo Cabrera Jauregui, an architect and computational designer who coded and 3D-printed the stair models—each of which takes about 10 hours to complete—before the team selected three options to show the client. “Having an object that you can see from everywhere—contrary to having something drawn on your screen that only gives you part of the full geometry—helps you comprehend the proportions,” he explains.

The model shop’s 3D printer, in addition to its laser cutter, can be programmed to mold and carve the intricate building components for designs that architects are creating in software programs such as Rhino, Revit, and SketchUp. And though these programs can be used to produce photorealistic renderings and create flythroughs of a virtual building, they don’t replace the impact of a physical model.

“We are always trying to make this dialogue between the digital world and real-world construction and manufacturing, and physical models can connect them,” Cabrera Jauregui says. In this respect, even the most basic cardboard study model can more effectively help a client understand scale and context in comparison to a 2D rendering.

Rzezniak has been building models for 36 years. And though he retains his reliable woodshop with traditional wood-shaping tools, saws, and drills, he says the computer-driven machines, including a CNC router, are a most welcome addition. Model making “was really hard work” before the new technology, he says. Site elevations had to be carved by hand, but the laser cutter takes care of them now. Building elements had to be glued individually, where the 3D printer can mold their assembly all at once. “Now it’s fun to make models with these new technologies,” Rzezniak says, “but you still need experience and hand skills to put the pieces together.”

As for the MoMath model, the team tried nearly two dozen iterations of a self-supporting stair to circumnavigate a conical sculpture that will hang from the museum’s second-floor ceiling. Each time, new calculations adjusted the stair’s contours—where it would begin at the bottom and land on the top, whether there would be any landings, how wide the handrail should be, and which materials should be enlisted for each element. “These are subtle things that only physically you can perceive,” Cabrera Jauregui says. The MoMath leaders were thrilled with the final model, he adds. “They totally understood what we were trying to produce.” N

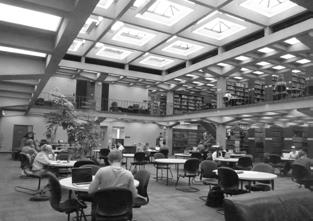

BY PAMELA MOSHER

s college and university construction proliferated with the end of World War II, the benefits of the GI Bill, and the start of the Baby Boom, there was a surge in the establishment of new academic libraries. Shaped by the confluence of postwar optimism and Cold War brutalism, many libraries of this period focused inward, creating both a quiet place for study and research and a repository for books—along with impenetrable-looking exteriors, limited fenestration, and a negligible response to context. More than half a century later, many of these buildings merit rehabilitation to meet contemporary programming and study predilections.

“Renovating midcentury academic libraries requires a strategic balancing of the priorities set by librarians, facilities teams, and university leadership,” observes Principal Gili Meerovitch, who co-leads Perkins Eastman’s

libraries practice. “These projects must respect the historical and architectural significance of the original structures while addressing modern demands such as technology integration and user-centered spaces. Through thoughtful reimagining, these libraries can continue to shape the academic experience while fostering innovation and belonging.”

Alignment with current library practices is the goal of three of the firm’s recent renovation projects: Columbia University’s Law Library in New York City, Colorado College’s Charles L. Tutt Library in Colorado Springs, and Johns Hopkins University’s Milton S. Eisenhower Library in Baltimore. Improvements include the introduction of natural light, prioritization of accessibility and comfort, broadened programmatic potential, and implementation of performance strategies and systems.

Columbia University’s Law Library has remained largely unchanged since it opened in 1961, despite significant shifts in learning styles, technologies, postures, and expectations for libraries. Located in Jerome L. Greene Hall, which was designed by Max Abramovitz of Harrison & Abramovitz, it is currently undergoing a transformation across three levels of its existing stacks and reading areas. Principal Mindy No, serving as project manager, is leading the renovation to reimagine the law library as a marquee space that reflects its central role in student learning, groundbreaking scholarship, and community engagement.

“The former library,” she notes, “had low ceilings, dark interiors, outdated finishes, narrow corridors, and limited seating and study options.” To introduce more natural light into the interior, a doubleheight reading room was created through strategic demolition of the floor slabs, along with added steel column reinforcements. The new space takes advantage of the existing glazing to frame expansive views of the surrounding campus and the university’s main quad.

The project team, she says, “had to navigate design and technical challenges presented by conditions that were not reflected in the historical as-built drawings as well as concerns about the concrete slab’s integrity.” For example, “demolition and removal of the floor finish revealed that certain slab locations were crumbling, which required removal and replacement with new slab and steel.” The result is a bold repositioning of the library to accommodate diverse learning styles and user experiences in a sustainable, collaborative, and inclusive environment. Flexible seating options are distributed throughout, and wide stairways facilitate connections between levels. In its pursuit of LEED Gold for Commercial Interiors, the team employed biophilic strategies, incorporating natural materials such as marble, wood, terrazzo, and metals, along with low-VOC finishes and recycled content.

This project represents one of the most significant capital investments in the history of the law school, helping Columbia maintain its Tier 1 status. When the library reopens later this year, it will serve as a model for peer institutions nationwide.

Facing similar challenges, the Milton S. Eisenhower Library, designed by Wrenn, Lewis and Jencks, is undergoing its first major renovation since its completion in 1964. The project aims to transform the building into a vibrant center for scholarly pursuits, leveraging improvements to physical accessibility, technology, systems replacement, and performance challenges into design opportunities that enhance the user experience.

A beloved campus landmark, the building’s iconic lobby features double-height spaces with full-height glazing on the east and west sides, travertine wall cladding on the north and south, and a custom chandelier, that, along with the cladding, is critical to the library’s identity. The wall cladding is being preserved and the chandelier restored, while other aspects of the lobby will be strategically improved. The renovation will also provide a new accessible entry and bring natural light deep into the four belowgrade floors that currently house the majority of collections and research/study areas in an artificially illuminated environment.

1. The Milton S. Eisenhower Library’s east-facing entry vestibule looking onto “The Beach,” an adjacent grassy area, has been redesigned to be more welcoming and accessible. 2. Iconic features of the original lobby, the chandelier and travertine cladding, will be retained. 3. The original east-facing entry vestibule was cramped and not easily accessible. 4. The C Level Reading Room will provide study seating options and zones designed for quiet or noisy conditions. 5. The existing reading room offers few seating options, a low ceiling, and artificial illumination. 6. To bring light into the lower levels, a multistory vertical space, level with the lobby, will be inserted and lined with glass panels.

Creating flexible, high-quality study spaces while optimizing natural daylight and other forms of lighting is a major impetus for the renovation. A new central stair carved through the building and a generous, walkable skylight above it will become the glowing heart of the building, providing wayfinding, circulation, and bringing visual warmth to all floors.

“A key piece of the modernization of the Eisenhower Library,” points out Dianne Chia, project architect, “is to update the building for access and inclusivity. The main doors to the original building were elevated above the lobby with a short flight of steps, making it a convoluted and unwelcoming entry. We addressed this by removing the elevated slab, creating an entry directly at lobby level that is coordinated with the enhanced lobby design and new exterior landscaping.”

Two-thirds of the university’s energy requirements are supplied by an off-campus facility with 500,000 solar panels. The library is targeting LEED Gold, and it is designed to be net-zero emissions and energy ready—the first building renovation on campus to do so—in preparation of immediate switch over when the primary campus infrastructure is replaced.

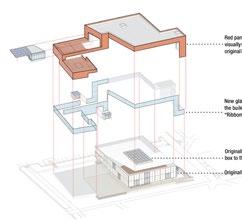

Designed in 1962 by architect Walter Netsch of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in the brutalist style, the library’s original fortress-like exterior belied finely detailed interior elements such as concrete ceiling coffers. When the college determined the library needed expansion and renovation, it also committed to achieving net zero energy (NZE), a challenge for most renovations, especially academic buildings from the postwar era. Major goals included bringing natural light into the library’s interior spaces and establishing visual connections to its surroundings, affording views of the Rocky Mountains, adding exterior terraces, and reestablishing the adjacent Tava Quad.

Exterior precast concrete panels were removed in select areas to maintain the required percentage of glazing to achieve NZE while opening student-centric spaces to vistas of the Rockies and campus. And technological challenges arose on all fronts: introducing new fenestration, exterior balconies, multiple exits, and a formal entry while achieving NZE performance; joining a new structure to an old one (aligning floors, accommodating new systems, HVAC, sprinklers, and lighting); and adhering to strict requirements for sensitive temperature and humidity controls for special collections, as well as the building’s 24/7 use.

To fulfill the project’s goals, “the team maximized the sustainable aspects of the existing building and the addition,” says Stephanie Kingsnorth, principal in charge. “Designing the building systems to work with the low existing floor-to-floor height of the 1962 building and transitioning the systems between the original structure and the additions were critical parts of the design process,” she adds,

“requiring careful coordination to work within the limitations of the original building and to embrace the opportunities presented by the expansion.”

Due to challenges like those Kingsnorth outlined, constant coordination throughout the design and construction phases was essential to the project’s success, especially with the design-build contractor and subcontractors. The subcontractors, who were used to hiding everything above ceilings, came to understand that even routing sprinkler lines in alignment with the original concrete coffers was crucial to the visual sensibility of the project, which called for exposed ceilings in public areas to highlight the original structure. Ceiling heights in offices and classrooms were constantly revised as new systems were integrated. Unfortunately, many of the design-build subcontractors weren’t aware of the unique column and beam intersections in the 1962 building. Working carefully, the trades rerouted elements and the design team added soffits and incrementally lowered ceilings to allow the systems to fit into the original building.

The NZE building is wrapped in a red ribbon of fiber-cement panels— inspired by the nearby Garden of the Gods geologic formations—that engages at the foot of the western edge of the addition and rises to encircle the original building, creating a visual dialogue between new and old.

The renovation of Tutt and the libraries at Columbia and Johns Hopkins—three architecturally significant structures—not only improves their function, accessibility, comfort, and sustainability, but also supports expanded programs, ensuring the continued existence of cherished campus buildings. N

4. The original concrete coffers enrich the renovated Colket Reading Room.

In addition to the skylight in the original reading room, artificial light was the main source of illumination.

Red paneling, visually connects the addition to the original structure

New glazing brings light and transparency into the building.

Original skylight, transformed into a light box, facilitated the addition

Original building

Community connections elevate the student experience at a Virginia high school.

BY TRISH DONNALLY PHOTOGRAPHY BY JUDY DAVIS

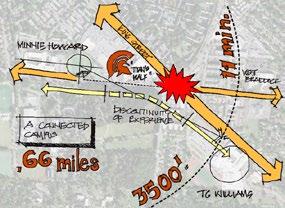

Alexandria City High School (ACHS) at the Minnie Howard Campus in Alexandria, VA, is a model of equity—designed to significantly enrich the student experience and strengthen community connections. Its amenities, including the Teen Wellness Center, Student and Family Resource Center, Early Childhood Center, and a new aquatic complex, all with separate entrances, foster inclusive learning and engagement.

At the heart of this school for 1,600 students is the visionary Creative Commons atrium, a dynamic space that blends Career and Technical Education (CTE) and specialty labs with social areas and dining services, creating a collegiate atmosphere. ACHS is LEED Gold certified and net zero ready.

1The Creative Commons transforms the traditional, institutionalstyle cafeteria, which would normally occupy a single sprawling space on one level, into a series of dining areas distributed vertically across all five floors of the school. Providing a student-centered ambiance for dining and socialization, these spaces become extensions of the surrounding arts, science, and CTE spaces during the rest of the school day.

In addition to classrooms for traditional academic curriculum, the school design accommodates enhanced CTE pathways, with links to local industries in fields like renewable energy, aerospace, cybersecurity, and surgical tech. Creating a healthy, high-performance place to learn sets students on a lifelong path to healthier, happier, more productive lives.

The community plays a large role in the new campus. The state-funded Teen Wellness Center has an on-site clinic, run by the Alexandria Health Department. A city-run Student and Family Resource Center operated by the Department of Community and Human Services has a home on the campus too. These two services, plus a 100-student Early

Childhood Center that offers a Head Start program, are meant to serve and enhance student well-being and the resilience of the larger Alexandria community. The school is also designed to welcome community use of its aquatic center, gym facilities, and fields after hours when operated by the Department of Recreation, Parks & Cultural Activities.

“As I stand here, my heart is full, knowing that this building is not just a structure but a symbol of our commitment to ensuring the equitable access to the best education for every student in Alexandria. It’s a place where dreams will be nurtured, talents will be cultivated, and opportunities will abound for years to come.”

—ALICIA HART ACPS Chief Operating Officer

Alexandria City High School: Minnie Howard Campus

3701 W. Braddock Road, Alexandria, VA

Client: Alexandria City Public Schools

Program: Primary and secondary education and social services

Size: 343,410 sf

Site: 12 acres

Completion: 2024

Architect and Education Planner: Perkins Eastman

Design Team: Sean O’Donnell, principal in charge; Omar Calderón Santiago, project designer; Ken Terzian, construction administrator; Huyen Nguyen, Sogol Alesafar

Associate Architect: Maginniss + del Ninno Architects

Consultants: CMTA Inc. (MEP/FP/IT/AV/security); Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. (civil/site/landscape); Ehlert Bryan Inc. (structural engineer); Polysonics Corp. (acoustics); ECS Mid-Atlantic, LLC (geotechnical/hazmat); Heller & Metzger, PC (specifications); Downey & Scott, LLC (cost estimator); Aquatic Design Group, Inc. (pool planning and design); Nyikos Garcia Foodservice Design, Inc. (food service); Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. (envelope/ life safety)

Construction: Gilbane Building Company

Sustainability: LEED Gold and net zero ready

To address projected high school enrollment in the city and avoid the need to build two potentially socioeconomically disparate high schools, the board of Alexandria City Public Schools established an innovative Connected High School Network that promises to help create a better, more equitable, and richer learning environment for all its students. Students travel between the ACHS King Street and Minnie Howard campuses enjoying the best of both. N 4

In the first installment of a new roundtable series, Perkins Eastman grapples with the interconnected opportunities and obstacles—affordability and sustainability among them—that impact the daily lives of urban dwellers.

EDITED BY ABBY BUSSEL

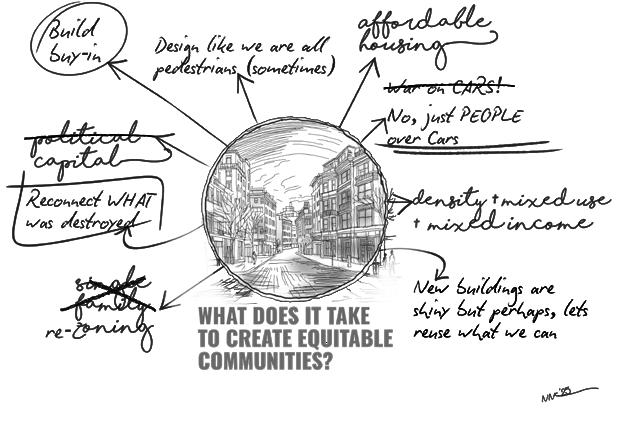

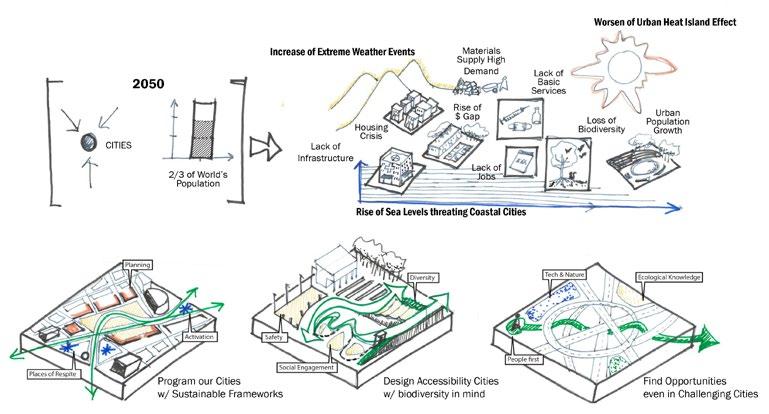

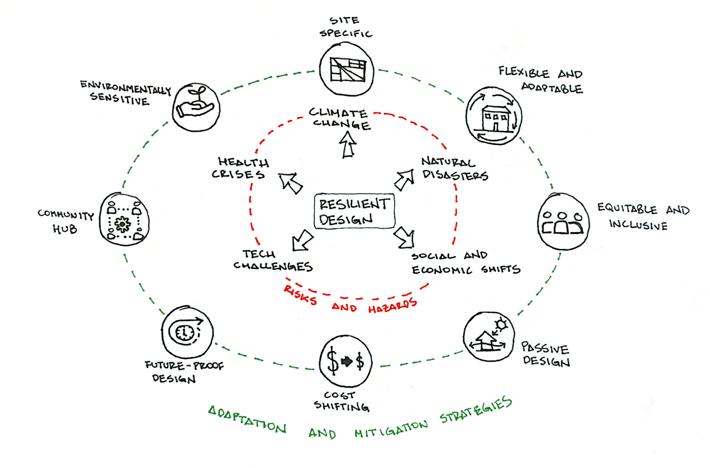

Rapid population growth and urbanization are driving climate change, housing shortages, health issues, inequality, and inequity. Yet cities are also uniquely positioned to address these crises. How can architects and planners, politicians and policy makers, developers and nonprofits reimagine the status quo to make cities more accessible? In a candid conversation, voices from across Perkins Eastman address issues at the intersection of affordability, mobility, and sustainability in their many facets—adaptive reuse, climate change, housing, lending practices, land-use patterns, zoning, and transportation infrastructure among them.

Nasra Nimaga specializes in K-12 Education projects, and she is interested in the intersections of architecture, advocacy, and policy. Silvia Vercher Pons works on Arts + Culture and Planning + Urban Design projects, serves as a Consortium for Sustainable Urbanization board member, and teaches at Pratt Institute. Both Nimaga and Vercher Pons are fellows of the Urban Design Forum’s Global Exchange, a program focused on New York City’s housing crisis.

Michael Friebele works across practice areas, contributing to civic, community health, cultural, and commercial projects. Dylan Glosecki focuses on residential and urban infrastructure projects and serves on the Seattle Planning Commission and the AIA Seattle board. Juan Guarin provides both sustainability support firmwide and performance-analysis tool training. Stephanie Kingsnorth leads Renovation + Historic Buildings and co-leads College + University practice areas. Brian O’Reilly is the West Coast residential practice area leader and a member of the firm’s Futures Council. Giaa Park works on projects in several practice areas, including Arts + Culture and K-12 Education.

Silvia Vercher Pons: The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 turns 35 this year. It has been transformative legislation, but we need to push beyond simple compliance to make our cities more accessible to all people. As Jean Ryan, president of Disabled in Action of Metropolitan New York, recently said, “What is good for us is good for you.” So how do you infuse accessibility—in its broadest sense—into your design work?

Giaa Park: We need to look at how we support people’s everyday lives. The ground floor and how people access it is very important. It’s the area they most interact with, so how do we activate it? We need to understand context and people’s abilities. How do we engage them and mix their lives into architecture at various scales, while creating a clear design focal point and hierarchies? The first part is understanding context, which includes lifestyle and social and cultural backgrounds. The second part is how to create connections within that context at the human scale.

Michael Friebele: The first thing that comes to mind is Interboro’s book, The Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion, which has been deeply influential to me. They think about the next level of things that inhibit accessibility such as defensive objects that might send a message—a surveillance camera, bollard, or landscape treatment. That those kinds of inhibitors can also be designed to make spaces accessible is a great opportunity. It builds on Giaa’s point about context. For example, Swope Health Village, a Perkins Eastman project in a historically redlined neighborhood in Kansas City, MO, is on a site designed in the midcentury and very much walled off à la Pruitt-Igoe. To make the site more accessible, we made its edges perform in a way that would welcome the community—such as through civic spaces.

Dylan Glosecki: We need to understand the point of view of others. For example, at a recent lecture, I heard someone talk about experiencing life from the point of view of a person who doesn’t drive. Because many of our cities have been designed around the automobile, there’s a lot of work to undo. If somebody can walk or roll into and around a building comfortably, then somebody who’s driving can also access it comfortably.

Nasra Nimaga: When does accessibility become a welcome driver of design that fully integrates people with disabilities—the most marginalized among us and the only minority group that any of us could join at any moment?

Stephanie Kingsnorth: We need to change our language, so it’s not only about code compliance, but also about making places for people. As Michael said, perception matters too. We have to take that into account as we design spaces to be accessible for all. It’s not just our perception. Sometimes, we tend to forget we are designing for the general population. We need to keep that in mind to make better spaces, better cities. I rail against the term “accessibility” because it can stymie us.

Nimaga: The Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual Global Liveability Index evaluates 173 cities based on stability, healthcare, education, culture, environment, and infrastructure. Not a single US city made the top 20 in 2024. Underscoring that point, current data shows we’re facing a shortage of some four million homes. What can we do to create housing that is affordable, inclusive, and abundant?

Brian O’Reilly: Removing barriers such as single-family zoning, which is both exclusionary and discriminatory, and legalizing the creation of missing middle housing are some of the first steps. Seattle is effectively doing this, as is Washington state. Eliminating parking requirements, which increase the cost of housing and put downward pressure on the supply, is another. Similarly, single-stair buildings, also known as point access blocks, improve efficiency and affordability for smaller apartment projects. There are all sorts of ways to incentivize housing creation.

Friebele: Our nonprofit client, the George Kaiser Family Foundation, provides $10,000 stipends to people who move to Tulsa. Our work

on Western Supply, housing designed for fully remote workers, looked at offering fewer amenity spaces in favor of civic engagement through nonspatial benefits. A real estate investment trust program was proposed as one idea, and an on-site market will provide health and wellness resources to tenants and the greater community. It’s investing money otherwise spent on wine tasting rooms and makerspaces, which are easily found elsewhere in the city. Expanding on Brian’s point, it’s a project that explores ways to make housing more buildable. This experience and other precedents in the industry lead us to question how fundamental elements such as corridors are considered or why investments with little cultural return are made. Western Supply shows there is value in alternative forms of civic engagement.

Park: With COVID and new technology, our challenge has changed in places such as New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, with offices being converted to residential uses. It’s not just about more housing. Depending on the location, the dynamics, and technology, it’s about how we can make inclusive, easily accessible, and vibrant communities.

Glosecki: I don’t believe we can decouple housing from the design of community. When we talk about housing, we need to think about needs and services that go along with it.

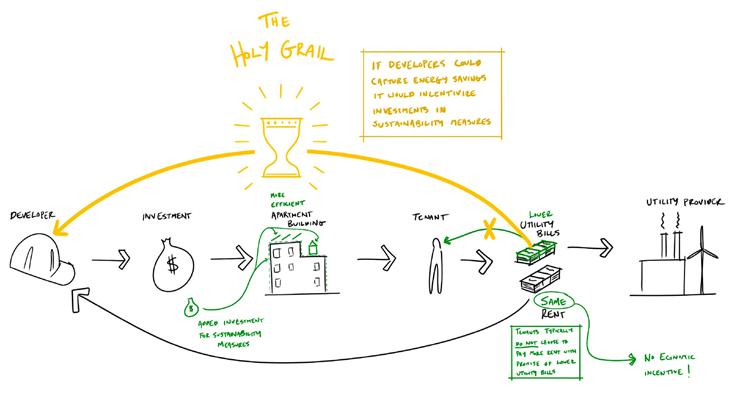

Guarin: A related topic is sustainability, which is not a priority for developers. But a lot of Passive House projects are affordable housing developments due to incentives. When developers ask why they should make it sustainable, why incur a cost for things, like Michael was saying, the key is incentives. It’s encouraging to tell people there’s no reason why affordable housing has to be lower quality than standard housing.

O’Reilly: I agree with Juan in spirit, but when we establish sustainability requirements, we should be certain we are not limiting housing creation. Developers say sustainability requirements prevent them from making their projects pencil out. The carbon footprint of someone living in a single-family home is dramatically higher than someone in an inefficient multifamily building in the city. Just living in a dense urban environment is a win from a sustainability perspective.

Kingsnorth: I’m going to switch to the adaptive reuse aspect. A lot of it is limited by zoning codes, building codes, historic preservation, and overlay zones, so there are reforms that need to happen. Right now, when you change the use, you have to be fully compliant with the code for new buildings, and that’s very hard with an existing building. But some cities and states are making changes. California’s AB 529, which passed in 2023, encourages adaptive reuse for residential projects. Renovation is not always more expensive than new construction. There needs to be more of a willingness to think differently about reuse.

“As we create new developments or rethink our cities, which can lead to gentrification, how do we make sure we improve, and not worsen, existing inequities?”

–NASRA NIMAGA Senior Associate

“I don’t believe we can decouple housing from the design of community. When we talk about housing, we need to think about needs and services that go along with it.”

—DYLAN GLOSECKI Senior Associate

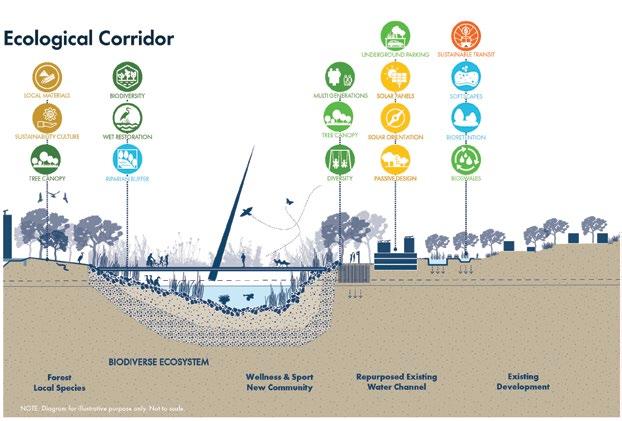

Program our Cities with Sustainable Frameworks

Vercher Pons: There is nothing more sustainable than not building anything or reusing what we have, as Stephanie points outs, so how do you see this reality in your cities?

Guarin: Climate change is real, and every day we get further away from our carbon reduction target, so how can we design our projects to be future proof? Instead of just designing a building, we can turn it into a community hub that, in case of a power outage or natural catastrophe, the entire community can go there for refuge. Let’s make sure our buildings respond to the different kinds of shocks and stressors particular to their regions. Silvia and I have done many projects together and the first thing we ask is, “What’s the climate?” Is it experiencing a significant amount of heat stress or cold stress, and how does our design respond to those

Urban Heat Island Effect

Coastal Cities at Greater Risks from Rising Sea Levels

Design Accessible Cities with Biodiversity in Mind

Find Opportunities Even in Challenging Cities

conditions? Some regions are going to get hotter over the next century, some regions colder. It’s our job to do the research and get the right data to understand how our project is going to perform now and in 100 years.

Vercher Pons: Recently, I spoke with a developer who builds affordable housing. I asked about the role of sustainability in his projects, and he answered: “We don’t contemplate sustainability because we lose money when implementing it.” How can we strike a balance within the people-planet-profit approach? And how can developers be inspired to create better spaces that not only enhance residents’ lives but also contribute positively to our cities?

O’Reilly: I’d like to raise a point that Juan made earlier, which is an economic conflict between sustainability and the financial

“Instead of just designing a building, we can turn it into a community hub that, in case of a power outage or natural catastrophe, the entire community can go there for refuge.”

–JUAN GUARIN Sustainability Specialist, Senior Associate

performance of a building. Tenants pay their energy bills; it’s not folded into rent or paid by the building owner or operator. It’s very difficult to make an incentivized connection from one to the other. Building owners can’t say, “You’re going to have $100 in energy savings per month, so we’re just going to raise your rent $50.” Renters don’t care. They’re making choices based on the rent. If there were mechanisms that allowed building owners to capture those savings, that would incentivize them to put sustainable systems into their buildings. With the expertise of our sustainability team and connections to industry partners, we could drive some of that innovation.

Guarin: We need to be very smart and very creative when proposing something that might cost a little bit more—better performing windows or more insulation in the building envelope.

We have to capture the savings from that strategy and try to offset that added cost somewhere else, and that’s why it’s critical for us to collaborate with innovative consultants.

Glosecki: I also want to add to what Juan brought up earlier about planning for building use 30, 40, 50 years into the future and considering climate change and increased weather events. It got me thinking about not only renovating buildings, but also renovating current urban land-use patterns and how we lay out our neighborhoods. Any new development in the middle of these largely single-family zones can become a community resource hub—a mixed-use building with a corner store or bodega in its base. If there is a natural disaster, households within walking or rolling distance of that location have access to food and drink in a conditioned space. It moves toward the 15-minute city idea.

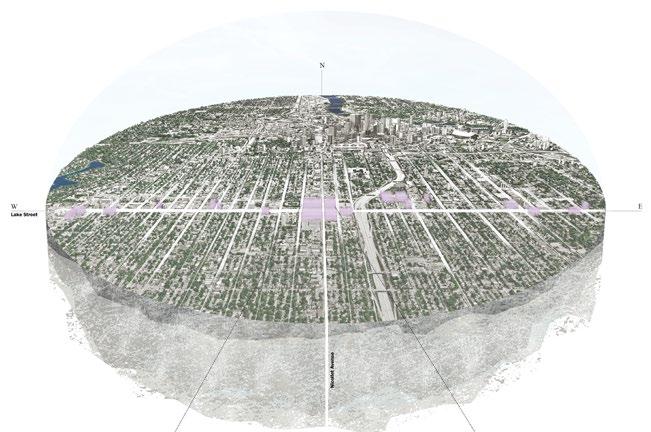

Nicollet Avenue is the main north-south access that connects into Downtown Minneapolis. In 1978, a new Kmart opened as the anchor of a shopping district conceptualized to turnaround an ailing part of the city. To accommodate it, a roughly four-block area of continuous streetscape was removed.

The store, vacated in 2018, was acquired by the city for redevelopment with the purpose of reconnecting Nicollet Avenue and forming a new center at the intersection of Lake Street. In 2023, the store succumbed to fire, ending the nearly 50-year socioeconomic divide it caused.

Nimaga: Let’s talk about mobility and navigating cities. As we create new developments or rethink our cities, which can lead to gentrification, how do we make sure we improve, and not worsen, existing inequities?

Glosecki: It’s not only about how do folks get from point A to point B, but also how do services get to people? If we can lay out our cities or adapt them to create more complete neighborhoods, so people can walk or roll to their services, then it’s not as important that they have bus access both here and there. A lot of US cities developed around a streetcar network. Car companies bought them out, and ripped out the tracks, but they didn’t rip out the development patterns. In Seattle, we still have a lot of small commercial centers throughout our single-family neighborhoods that have been forgotten, and we need to recapture them. This gets back to liberalizing our zoning, so we aren’t artificially constraining our supply, which increases costs and leads to gentrification and displacement.

O’Reilly: The amount of opportunity we have in our cities when it comes to single-family zoning is enormous. Legalizing duplexes, triplexes, and quadplexes—neighborhood-scale multifamily units— could make a huge difference. The economic issues we’re grappling with in our cities for the creation of housing is a heady brew of interest rates and the cost of equity and construction. The dirty little secret is that if rents are not high, it’s difficult to make a project viable unless all other costs are pretty low. Finding ways to get those

financials working and doing so with a connection to services is paramount.

Kingsnorth: Housing is not just one extreme, the single-family home, or the other, the high-rise. There are low-risers and midrisers. What do we do in a downtown environment or a suburban environment?

Nimaga: Right, we don’t talk about alternatives enough. In New York, basement apartment legalization, for example, could supplement housing supply. According to the nonprofit Citizens Housing & Planning Council, 10,000 to 38,000 potential basement apartments could be “brought into safe, legal use” in New York City without rezoning.

Guarin: I want to go back to what Dylan was saying about taking space back from the cars and giving it to the people. We’re going to give you more space to walk, to sit at a café on the street, and we’re going to take one lane from the streets and make it pedestrian. During COVID, it was fascinating to see cities start to take space from cars and give it to the people, who then started taking ownership of it—outdoor restaurants, playgrounds, and other activities in spaces that used to belong to cars.

Friebele: We’re going through that experimentation now in Minneapolis. Most of the major arterials are going under a lane diet. And, to Dylan’s point, there’s something overlooked in many cities, especially Midwestern cities, where the streetcar lines historically have created a number of the divides in our

SEATTLE NETWORK OF NEIGHBORHOODS LEGEND

NEIGHBORHOOD CENTER OPPORTUNITY

800 FT RADIUS (1/4 MI DASHED)

3 MIN WALK (5 MIN DASHED)

communities. If we were able to really think about what they mean, there’s a lot of [ameliorative] potential there. And it goes back to political capital. It’s where working with nonprofits, as well as public-private partnerships, is going to help. Our work with Swope as well as the Kaiser foundation allows us the opportunity to experiment and create proof of concept. We’ve started to bring similar things to our private developers and their feedback is, “It’s great, but lenders won’t understand it.” I’d like to see those efforts expanded. Nasra, when we met over the Dream Charter School in East Harlem, which is part of a mixed-use complex of affordable housing and community services, it was incredibly inspirational. It’s another model with untraditional uses coming together and a client who is rooted in the community.

Kingsnorth: Michael hit on a key aspect because we keep talking politics, but it’s the lenders. They’re not seeing the vision of developers with a passion to do the right thing, so it might not be an issue of political capital as much as it is capital.