1 TOLERABLE INEQUALITY AND THE POLICY PROCESS

Introduction

Housing for the homeless can be provided, but it is not, and homelessness is tolerated (Donovan, 2011). Women can be paid equally, but they are not, and income inequality and sexism are tolerated (Fox, 2015). Ramps can be installed at every building and beach for those using a wheelchair, but they are not, and ablism is tolerated (Harahap and Santosa, 2019). People’s individuality, sexuality, and gender-identity can be respected, but they are not, and transphobia and homophobia are tolerated (Mayo, 2004). And the very few succeed wildly, while a great many struggle mightily, and the intentionally unfair winner-take-all system is tolerated (Ku and Salmon, 2013). Each of these issues reflects an epidemic of tolerance toward the inequalities of those who can least afford the prevailing norms. Therefore, this state of Tolerable Inequality asks just one question:

Why Does the Public Policy Process Tolerate Inequality?

One Word: Power

Power is built on the illusion of differences that grant agency to ‘social status’ in ways that allow for sanctioned inequality to be distributed at the discretion of the ruling class. With this in mind, power is defined as the ability to exercise individual choices; and to influence the systems and structures that may constrain those choices. The toleration of inequality stabilizes unequal power dynamics and in so doing solves many of the political problems that equality imposes. The use of the public policy process to reinforce the illusions of inferiority and superiority that constrain the choices of some to keep power in the hands of others is Tolerable Inequality.

DOI: 10.4324/9781003488866-1

This chapter has been made available under a CC BY NC ND 4.0 license.

Tolerable Inequality is defined as the way incumbent policy actors use the policy process to make social, political, and economic inequalities value-acceptable for high-value constituencies in order to maintain power dynamics and avoid political penalties. The three tactics of Tolerable Inequality include: (1) focused inattention (Bachrach and Baratz, 1962) and inaction (Feldblum, 2008: 131–133); (2) deviation harmonization between expectations and perceived reality, and (3) equality governance, where equality is both conditional to compliance and relative to identity (Pepin-Neff, 2021). Tolerable Inequality relies upon a hierarchy of difference in which a ranking of essentialized identities preserves the social status of high-value constituencies (Festinger, 1954), and involves systems of attention, expectations, and identity which function in the policy process to locate or avoid political penalties.

To illustrate the present state of Tolerable Inequality I look at examples from the queer, trans, and gender-diverse (LGBTQ+) communities. For instance, Tolerable Inequality can be seen where fixations on small moments of progress (i.e. one trans person on a swim team) lead to large counter-reactions from the policy process (i.e. banning all trans sports across dozens of states), and where a focus on large inequalities (i.e. anti-trans violence) leads to small counter-reactions from the policy process (i.e. hate-crimes laws). The three Tolerable Inequality tactics that incentivize the continued dominance of existing power dynamics in the policy process include:

• Focused Inattention: Inattention and inactions send a message about what types of inequalities are socially and politically acceptable, limit access of vulnerable identity groups to the public policy agenda and reduce conflicts with existing power dynamics. Focused attention also transitions to focused inattention, where salient issues are seen to be resolved.

• Deviation Harmonization: Harmonization is about decreasing the attention to negative social reactions by high-value constituencies regarding unacceptable deviations by meeting expectations in ways that reinforce existing social status and power dynamics by reducing the perceived occurrence of unacceptable deviations.

• Equality Governance: Equality without power is not equality. Equality governance looks at the use of Soft Equality policy reactions to address Hard Inequality issues in order to relieve the discomfort of high-value constituencies.

Tolerable Inequality is on the rise in the United States and around the world as power dynamics are reproduced by public policies that both overtly and covertly support transphobia, classism, ableism, homophobia, racism, and sexism. The deterioration of democratic principles including civil liberties could be seen in 2023, when the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA, 2023: 18) reported, “In 2022, GSoD data show that countries with net declines in democratic performance again outnumbered those with net advances, as has now been the case

for six consecutive years, with 2021 the worst year on record.” The rise of Tolerable Inequality is also evidenced in disparities in economic inequality. Inglehart and Norris (2017: 448) note that “Economic inequality declined in advanced industrial societies for most of the twentieth century, but since about 1970 it has been rising steeply, as Piketty has demonstrated.” This includes premeditated policy design to defuse moments of attention that generate an opening for policy reactions and the policy reactions themselves, which are constructed with toleration incentives that prevent systemic policy change.

Examples of Tolerable Inequality in the policy process examine the ways incumbent policy actors access inequality as a resource to protect themselves from political penalties. This happens when the answer to crime is more jails (Lurigio, 2017), when the solution to the transphobia high schoolers face is to ban their use of bathrooms (Murib, 2020), when the issue of homelessness means banning public parks (Giamarino and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2024), and when the solution to antiLGBTQ+ bullying in schools is to pass laws so school children “don’t say gay” (Goldberg, Toomey, and Abreu, 2024). However, the structures and institutions of the policy process do the most damage in the secrets they keep, the disruptions they avoid, the silence they expand, and the inaction they tolerate. Exposing the scandal of Tolerable Inequality is one piece of this book; however, the book also proposes a new policy cycle that centers the role of political penalties which motivate incumbent policy actors to contest the way policymaking systemically establishes socially desirable suffering, promotes prejudice, and invites value-acceptable discrimination as a convenience for the powerful.

This book speaks to the analysis and question raised by Druckman and Jacobs (2015: 133) who note, “The question, however, that has beguiled generations is how to control or, more realistically, mitigate the threat of elites, especially as they attempt to short-circuit democratic checks by manipulating citizens into supporting their narrow interests.” This role of elites and the social vanguard who dominate the policy process, democracy, and government have been central questions of social order and polity for generations. In Leviathan, Hobbes notes, “Riches, joined with liberality, is Power, because it procureth friends and servants” (Hobbes, 1651: 100).

In Tolerable Inequality, this book argues that under conditions of penaltyavoidance, where political penalties are predicated on attention to social reactions, incumbent policy actors have three main choices to keep power: (1) limit the attention given to a social reaction through inattention or stigmatizing the issue as a “loser” issue, (2) limit the social reactions from high-value constituencies by harmonizing the deviations (either by legitimizing the idea that policy has gone ‘too fast or too far’ by introducing more inequality to the system), or (3) by mitigating any potential sympathy toward a marginalized identity group so there is no perceived deviation at all. If an identity group is expected to be inferior or is getting what they deserve, then there is no deviation from the expected norm to worry about. This also means the incentive structure and accountability mechanisms of the policy process are not focused on solving the underlying social or political issues.

Incumbent policy actors use public policies to manage the social reactions of high-value constituencies in such a way as to avoid political penalties and keep them in power. This includes preserving durable discrimination, state-sponsored suffering, and value-acceptable inequality against vulnerable identity groups. Importantly, in Tolerable Inequality the stabilization of power dynamics allows discrimination to occur in an acceptable way. Or put another way, in a state of Tolerable Inequality there exists the occurrence of prejudice or inequality; however, these are not seen as deviations even when there is attention and a social reaction from high-value constituencies because this reaction is not one of unacceptability and therefore imposes no political penalty. Hurrell (2005: 13) notes, “Inequality and rising disparities may also reduce trust in political institutions and promote a sense of powerlessness, which in turn may contribute to the acceptance of the status quo.” This is where the toleration of inequality comes in because inequality is a reliable, predictable, and familiar political resource that can be distributed throughout the policy process to satisfy the biases and stereotypes of the people that incumbent policy actors need to stay in power.

Because attention to negative social reactions is the primary factor in political penalties, this means that inattention, and mitigation of social reactions are the best choices for avoiding and not addressing an underlying issue. Solutions then come from the harmonization of deviations by inattention, distraction, and expectation setting – which opens the door to stereotyping and appeals to biases that direct people’s social reactions. This also reveals the practical political and policy effects of “loser” issues. For instance, addressing or solving an inequality such as the economic inequalities that those living in poverty face does little to generate attention that inspires social reactions (positive or negative) because poverty is not often media salient, and even if it were, there is little incentive to solve such a complex social issue because incumbent policy actors may not receive credit. In addition, the policy reaction may not be able to provide immediate satisfaction to alleviate a penalty condition created by attention to an unacceptable deviation from the norm (i.e. the homeless of veterans at Christmas time). Whereas, blaming the poor for poverty gains both attention from the media and harmonizes the deviations by saying the homeless prefer homelessness, therefore, satisfying the need to alleviate the social reaction from high-value constituencies.

This book examines the way power, inequality, and the policy process interact to protect those with authority and status from political penalties. These conditions of toleration affect most social justice issues and are successful because the political consequences of equality are dangerous to the political survival of elected officials and those in power. Governments and elected officials believe that if equality is made real in the lives of all their citizens this will cost them their political survival because power dynamics will change, including the influence of the people who keep them in power. As a result, policy solutions create the conditions that reinforce and tolerate inequality in order to avoid these political dangers. Indeed, the connections between norm-development, expectation setting, and policy design

are not an objective exercise. Politics influences the construction of policy on the terms that deliver the most power to the person designing the system. Policies cue the public to the importance or significance of certain norms, expectations, and issues and imbed the issue and social expectations in institutions and structures.

This book makes two propositions: (1) the policy process responds to political penalties which requires a new way to look at the elements that influence the policy process, referred to as the Expected Penalty Policy Cycle (EPPC), and (2) Tolerable Inequality is a state of premeditated policymaking that uses both inequality and versions of equality as resources in the policy process to protect incumbent policy actors from expected political penalties by introducing more inequality. To illustrate this, I highlight the concepts of “Soft” and “Hard” Equality policy settings relative to “Soft” and “Hard” Inequality. Here, Soft Equality may be used to advance Hard Inequality.

In Tolerable Inequality, I argue that the leading factor that influences the toleration of inequality in the policy process is the fear that incumbent policy actors will lose political power. This obvious point is the basis of the U.S. Constitution. In 1788, James Madison wrote in Federalist 48, “It will not be denied, that power is of an encroaching nature, and that it ought to be effectually restrained from passing the limits assigned to it” (Madison, 1788). To address the concentration of power in any one person or institution the separation of powers doctrine was put forward by Madison in Federalist Papers 51, where Madison wrote, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary” (Madison, 1788). With power located as the motivating feature in the politics of the policy process, this allows the rest of this book to examine policy dynamics that use inequality to insulate certain actors (at certain times) from expected political penalties that pose a threat to incumbent power.

Tolerable Inequality contributes to policy studies by proposing the Expected Penalty Policy Cycle (EPPC). Under this analysis, political penalties arise from the policy process when there is an unacceptable deviation between real or perceived normative expectations and perceived reality by high-value constituencies that generate attention to negative social reactions, which impose political penalties on incumbent policy actors. The goals therefore for establishing Tolerable Inequality in the policy process are to introduce systems and structures that distribute inequality in ways that match the expectations of high-value constituencies. The distribution of economic, political, social, health, environmental, and educational inequality through policies and processes harmonizes real or perceived injustices embedded into social and political issues and eliminates the perception of events and issues that deviate from established norms in ways that create political penalties. Pressures and penalties motivate policymaking with policy reactions designed to mitigate threats by producing stigma, discrimination, and sanctioned behavior. Inequality is a preferred public policy option because it maintains power dynamics and is a predictable resource with which to control both those favoring the sanctions or discrimination associated with injustice and those opposed. However,

for inequality to work more effectively as a policy solution than equality, it needs to be perceived as value-acceptable or emotionally satisfying to those high-value constituencies that keep incumbent policy actors in power. This value-acceptability can occur because the inequality is out of sight, the parties are perceived to deserve the inequality as a sanction or punishment, the solution costs too much or takes too long, or the problem has already been solved. Cobb and Ross (1997: 213–214) identify agenda denial tactics including “symbolic placating strategies” and “showcasing” which “gives the appearance that the problem is being addressed.”

Hall and Jones (1997: 52) highlight this connection between the presence of penalties and the defensive nature of the policy process, noting, “when threatened, participating institutions rally around the policymaking status quo. Because the power of subsystems to stabilize an issue area, scholars have inferred a whole system of government based on mutually noninterfering subsystems, a system that is highly resistant to democratic change.”

There is a common misperception that the public policy process is used to solve the problems of inequality. This is incorrect, it is equality that is the problem and inequality that is the solution. Under overwhelmingly risk-averse conditions, political actors do not have an eager appetite for systemic change and public policy works for the interests of the incumbent government. Part of this misunderstanding comes from the academic research, where political theorists have argued that inequality is bad for government stability and social cohesion, while public policy scholarship states that policies are made by the powerful for the powerful. This tension is identified by Dahl (2007), who connects the equality of people, the desirability for equality in democracies, and the role of democracies in delivering equal rights, while also noting, “Whatever the intentions of rulers may be at the outset of their rule, any commitment they may have to serving ‘the public good’ is likely to be transformed in time into an identification of ‘the public good’ with the maintenance of the their own powers and privileges” (Dahl, 2007: 5).

The reconciliation of inequality politics, power, and policymaking may be seen in selectorate theory (de Mesquita and Smith, Silverson, and Morrow, 2005) in the way elites under threat move to manage the policy process to protect themselves, and whose approach is affirmed by Inglehart and Norris (2017: 443) who state “insecurity has the opposite effect, stimulating an Authoritarian Reflex in which people close ranks behind strong leaders, with strong in-group solidarity, rejection of outsiders, and rigid conformity to group norms.”

The benefits of using the policy process as a tool to enforce inequality are found in the variety of policy reactions, some of which are loud and quick and others which are silent and slow. Link and Hatzenbuehler (2016: 666) highlight the power of inattention, noting “inaction might be strongly motivated, as when powerful groups directly benefit from the lower placement of stigmatized groups and can thereby pay lower wages and horde access to the best housing, schooling, and medical care.” But such inaction may also occur when powerful groups simply attend to what matters most to them, allowing themselves to remain unaware of and

inattentive to the needs of those who are “them” and not “us.” This inaction and inattention are useful because the cause of equality can be contagious and requires constant pushback from episodes of attention that can sway elite sympathy. Thus, the motivating principle of the policy process is that policy reactions result from the ways incumbent policy actors respond to expected political penalties. Tolerable Inequality argues that this anticipation follows attention to negative social reactions by high-value constituencies from an unacceptable deviation. Equality is the unacceptable deviation from the norm of inequality that these actors are trying to avoid.

Tolerable Inequality diverges at important points from much of the political science literature. While the Aristotelian argument acknowledges the difference between equality and equal merit with, “treat equals equally and unequals unequally” (Christman, 1992: 287) and inequality for the unworthy. Baluch (2018: 93) suggests that equality is a cornerstone of democracy and too much inequality undermines this effort, stating, “Political equality then is a necessary precondition for a healthy republic.” In addition, Boix (2015: 7) argues, “That inequality led to the breakdown of a stateless order where cooperation had been sustained by informal rules and the personal interactions of men and women with similar capabilities and interests.” Here, the argument is not that there is a presence of total inequality but rather proportional, targeted, and distributive Tolerable Inequality, where thresholds are set by government institutions to manage the attention and social reactions of varying identity groups. However, it is important to note the way tolerable levels of economic inequality in the policy process can facilitate distorted expectations because the impact of social inequality can be clouded by narratives of American exceptionalism that include the endless pursuit of the 'American Dream' (Wyatt-Nichol, 2011). Here, populist performance lies and Baluch, (2018: 103) notes, “Increasing economic inequality combined with equality of spirit explains how an individual like Donald Trump can become the candidate of choice for the working class.”

The concept of Tolerable Inequality is a device to examine the way the policy process is used to thwart equality and keep power dynamics stable by converting inequality into a value-acceptable deviation by: (1) focused inattention to inequality deviations and related social reactions, (2) harmonizing the real or perceived occurrence of deviations from the expected norm, and (3) using equality governance to shape the social reactions of high-value constituencies that lead to political penalties. This book focuses on different types of policy reactions (e.g. responses, legislation, statements, regulations) that contribute to situational and interpersonal comparisons that encourage value-acceptable discrimination, which invites hostility against the equality that vulnerable identity groups seek as a way to facilitate consequence-free political environments.

Tolerable Inequality builds on the philosopher and mathematician Edna Ullman-Margalit’s (1977: 139) identification of the “status quo of inequality,” in which she later adds, “these norms function as stabilizers and fortifiers of a

certain discriminatory status quo” (Ullman-Margalit, 1977: 182). It is this utility to inequality that I examine because norms (including inequality) serve purposes, from the identification of dominant actors to the ease of social coordination (Ullmann-Margalit, 1977). For instance, Dahrendorf (1968: 32) notes, “the core of social inequality can always be found in the fact that men are subject, according to their attitude to the expectations of their society, to sanctions which guarantee the obligatory character of these expectations.”

Tolerable Inequality is a concept that provides a new analysis of the functions of inequality in the policy process by looking at the politics of policymaking. Under this analysis, incumbent policy actors are incentivized to promote Tolerable Inequality in the policy process because it is a low-cost way to stay in power by delivering on the prejudicial expectations that a high-value public already hold. The public is incentivized to tolerate inequality that can be uncomfortable to endure, difficult to fix, may take a long period of time, and will introduce costs that challenge their status and social superiority.

I argue that the state of Tolerable Inequality constitutes a perversion in the public policy process where incumbent policy actors (namely elected officials, bureaucrats, and policymakers) use policy dynamics to avoid political penalties by sustaining postures of inequality and conditional equality as a means of retaining power. This policy analysis looks at the construction of problems that matter to the people that matter, at a time that matters (Pepin-Neff, 2019). For instance, there are policies that are fast-tracked in the policy process so that the timing will satisfy the prejudices of the high-value constituencies and keep incumbent policy actors in power. This is consistent with the Trump Administration’s introduction of a ban on transgender military service over Twitter in 2017 (Williams, 2019; Pepin-Neff and Cohen, 2022). In this case, public policy was used to weaponize inequality (Giroux, 2020). This perversion highlights the importance of Tolerable Inequality as a framework to examine policy psychology. In this case, it considers the ways the policy process rewards those who assimilate to normative behaviors and expectations with access to greater resources and power – and argues that this can make inequality a resource when the policy process rewards the underlying biases that police deviations from the norm through discrimination.

LGBTQ+ Inequality

As queer, trans, and gender-diverse rights have risen on the political agenda there is a tendency to incorrectly presume that either present-day challenges are few, or that the progress for one is progress for all. Smith and Lee (2024: 56) examine “What’s Queer about Political Science” and, in their account, they note the need “to uncover and critique how particular moral orders become normalized, necessitated and thus positioned as being beyond ethical scrutiny.” Queer, trans, and genderdiverse communities have a long history of experiencing intolerable horrors, from forced lobotomies (Drescher and Merlino, 2007), to forced sterilization (Carastathis, 2015), to concentration camps (Röll, 1996), to police brutality (Leighton, 2018),

murder (Tomsen, 1994; Tomsen and Goerge, 1997), and the “geo-political structural violence” connected to the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Oinas, 2019: 90). The consistently motivating force has been certain Christian churches. The ultimate goal of RightWing extremists in the United States is a kind of ‘Christian Darwinism,’ which makes tolerable the cruelty of queer, trans, and gender-diverse people through multiple means that are seen as value-acceptable policy reactions. Religiously justified malice (even when limited to the extremes) requires a different type of public policy analysis than the conventional approach. Indeed, this book argues that we have entered a new era of policymaking governed by de-institutional chaos. The resulting Hate Renaissance of the 2020's is a period of boldly unchecked inequality that is exemplified by the return of Donald Trump as U.S. President.

Under Tolerable Inequality, inattention, harmonization, and equality governance legitimizes and normalizes hate speech and value-acceptable discourse regarding the threat a deviant target population poses as well as the need for the state to criminalize both the identity group and those who aid the identity group. This includes permissible prejudice against queer, trans, and gender-diverse identity groups in the policy process that creates an environment where hate speech, hate laws, and hate crimes are joined. This includes the 23 U.S. states where “medically necessary” (Coleman et al., 2012: 168) “gender affirming care” is banned (Dawson and Rouw, 2024). An ABC news report stated, “As a transgender kid in a conservative region, Susan said Elsa could feel the growing tensions concerning people like her – she told her parents to ‘just let them hurt me,’ instead of moving out of state.” In the same report, a parent of a trans child in Texas in 2023 reported that the parent stated, “That did not feel like normal teenage stress, in Texas. Knowing that your governor and the top officials in your state literally don’t want you to exist – That’s a different kind of stress. It felt very genocidal there.” Tolerable Inequality, therefore, creates the conditions that inflame and legitimize extremist behavior and lead to violence against queer, trans, and gender-diverse groups. This violence includes the agonies that lead to high rates of crushing depression, suicidality, and suicide fatalities.

Too often missing from public policy equations are those marginalized identity groups that bear the burden of inequality, whether this is economic, social, political, health-related, or based on gender and sexuality. These vulnerable groups are important in the current model only to the extent that their plights garner attention to the unacceptable situation that attracts the social reactions of sympathetic high-value constituencies. Otherwise, their present sufferings present strategically manageable political penalties. For example, Link and Hatzenbuehler (2016) identified the health consequences of (specifically lesbian, gay, and bisexual) people and the impact of anti-same sex marriage legislation. They note, “Those LGB adults living in states that passed same-sex marriage bans experienced a 37 percent increase in mood disorders, a 42 percent increase in alcohol use disorders, and a 248 percent increase in generalized anxiety disorders between the two waves (Hatzenbuehler et al. 2010)” (Link and Hatzenbuehler (2016: 662–663).

The story of LGBTQ+ inequality is a story that illustrates the contemporary state of Tolerable Inequality in the policy process. The LGBTQ+ communities

know that incumbent policy actors fear equality that is distributed through the policy process. The LGBTQ+ experience teaches us that our identities and those of our children are attractive sites of cultural warfare. In addition, the policy process is used to diffuse the pro-LGBTQ+ sympathies of high-value constituencies in order to maintain oppression-based power dynamics. The government is not here to solve problems of homophobia and transphobia, but more often to erase identities and provide refuge for hate speech and structural violence.

For instance, in May 2024, four lesbians were set on fire in the Barracas neighborhood of Buenos Aires in Argentina (Padgett, 2024). In CNN’s report on the hate crimes, it states, “the attack represents an extreme manifestation of what they consider a growing wave of hostility against them. Those they blame most for this rising intolerance are the people in power (Rios, 2024).” This is just one horrific example of the terror, violence, and suffering that is ignored by the policy process. More attention to LGBTQ+ examples in political science and public policy specifically provides a valuable way to reconsider the incentive structures and existing accountability mechanisms of the policy process.

There is social and political infrastructure that is needed to sustain unnatural states of inequality. This includes a position in favor of inequality that is widely accepted, enforcement mechanisms that validate the inequality, and a conscious effort to view individuals based on essentialist elements to establish a social hierarchy. The implications for the policy process raise the stakes of this analysis because if the relationship between the state and the individual is based on a model where inequality is seen as the solution, then the policy process can isolate vulnerable identity groups from the government they empower and disenfranchise their participation in the democratic process.

The politicization of HIV/AIDS and demonization of those living with HIV/ AIDS across a range of categories created a state of second-class citizenship. The tolerability of social and political narratives harmed people and communities. It was argued that HIV/AIDS was a result of the wrath of God as the UK’s tabloid, The Sun, reported on its front page from a Vicar (Pendergast, 1990). It was also argued that pestilence and disease were retribution on homosexuals for gay sex (McAnulty, 1993: 111). Narratives also included the discourse “God hates fags” as a “rhetoric of violence” noted by Cobb (2006). Cobalt Sovereign notes that following an incident in May 2023, in a school bathroom in Minnesota in which they were attacked, they stated, “The moment after I was hit, there were pieces of tooth in my mouth.” Adding, “there was blood dripping down my teeth” (Alfonseca, 2023).

In the queer context, Bronksi (1984: 63) questions “How tolerant society would be if individualism and especially sexual individualism was made explicit.” Tolerable Inequality focuses on examples from queer, trans, and gender-diverse (LGBTQ+) policies and politics that are designed to ignore critical issues (i.e., HIV/ AIDS) and introduce discrimination as a way to punish, demoralize, and invalidate vulnerable identity groups so that their perceived inequality and inferiority can be used to maintain predictable support from and control of those actors (voters and

special interest groups) that gain satisfaction from feeling superior to others and want to maintain this status, which helps keep incumbent policy actors that deliver inequality in power. Naylor (2020: 11) identifies this connection by stating, “at the core of inequality is animus.” It is the introduction of animus and affirmative hostility that necessitates an analysis framework of the politics of policymaking. This animus against the LGBTQ+ community has been evidenced repeatedly.

In 2010, Bryan Fischer, the American Family Association director of issue analysis for government and public policy stated, “Homosexuality gave us Adolph Hitler, and homosexuals in the military gave us the Brown Shirts, the Nazi war machine and six million dead Jews” (SPLA, 2010). In addition, in 2019, Tony Perkins from the Family Research Council stated, “For years, LGBT activists wanted to keep the goal of luring children into sexual confusion under wraps. Now that they’ve hoodwinked a lot of the country on their agenda, these extremists no longer have to hide. In fact, they are increasingly bold–even boastful–about their real intentions of recruiting kids” (SPLC, 2024). Finally, in 2022, the American Principles Project issued a report, “Transgender Leviathan” authored by Pedro Gonzalez, who wrote “Public exposure to transgender ideology and its advocates, particularly those in the education system promoting radical ideas about sex and gender to children, often deliberately without parental consent or knowledge, has led to increased public skepticism and outright anger. The attempts to indoctrinate children have personalized the issue for millions of Americans in a way that few issues do” (Gonzalez, 2022: 5).

The Right Wing’s adoption of 'queer' ways to discriminate against queer populations demonstrates the importance of highlighting the politics of inequality and hostility against this population. The queer, trans, and gender-diverse communities know what it means to be invisible in society and to be the recipients of unmeasurable hostility. Tolerable Inequality examines both unobservable conflict and observable political phenomena. This can include a conspiracy of silence because silence about an issue or toward a group sends a message to the target group and the broader population about their social worth and value-acceptability in the policy process. For instance, former President Ronald Reagan refused to say the word AIDS until 1985 (Travis, 2022). The New York Times reported that this was “the first time he has publicly addressed the issue of the lethal disease that has claimed thousands of victims, primarily among male homosexuals, intravenous drug addicts and hemophiliacs” (Boffey, 1985). In his dissent against the Windsor Supreme Court decision, Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Alito wrote about the power of government silence in policy and law because same-sex marriage was not innumerate in the U.S. Constitution in 1789, the “silence of the Constitution on this question should be enough to end the matter as far as the judiciary is concerned” (U.S. v. Windsor, 2013).

It has, therefore, become necessary to rethink the visible and invisible politics of the policy process. This book is an effort to diagnose the variables that control the policy playing field and set up a framework for understanding how biased the policy process has become and what can be done to repurpose it. Policy can be

used as a source of disruption to the norm rather than a device to reproduce the norm (Wison, 2000). Ultimately, Tolerable Inequality is a malfunction in the policy process that stains the relationship between the individual and the state. The battle for the future of the policy process must therefore rethink the incentive structures and accountability mechanisms of the current operating system and establish new pathways for policy development.

For instance, the current policy process affirms the righteousness of inequality as a resource of the hetero-patriarchal Christian state to disenfranchise the queer, trans, and gender-diverse communities. McCloud (2018: 16) notes, “Economic Arminianism can be seen in the writings of some contemporary evangelical figures such as Edward Silvoso (2002), who suggests that God prefers capitalism, and that prayer can bring prosperity to one’s business.” McCloud (2018: 17) adds, “This theology, in its various guises, has offered a divine apologetics for class inequalities. In blessing the rich, the poor get damned. The socio-economic forces and material conditions that lay outside any one person’s control disappear within this imaginary, replaced by conjurations of individual will, free choice and moral status.” In this view, inequality is a necessary condition to distinguish those blessed by God and those sinners smote by God. Equality is evidence of God’s showering affection, which affirms both, the existence of God and the righteousness of inequality. Inequality, therefore, proves that God exists to her followers and to challenge the divine order of inequality is to challenge the existence and divinity of God which poses an institutional heretical threat to Christian theology.

Inequality as a successful policy outcome comes from a deeply rooted view that inequality is an act of God – and that inequality proves the existence of God. Many Christians believe that “a man reaps what he sows” (Galatians: 6) which means that disparities in wealth, health, reproduction, celebrity, and social status are indicators of God’s favor as well as the most visible and tangible evidence of God’s existence. The Bible says that God will provide (2 Corinthians 9:8) blessings and prosperity as signs of righteousness (Deuteronomy 8:18). In Proverbs, it states that “the rich rules over the poor, and the borrower is the slave of the lender” (Proverbs 22:7). This scripture establishes the incentive structure that more is better, and that prosperity is a sign of a good life from God.

Mary Douglas (1992) also connects religiosity and policymaking with risk theory. She notes, “risk, danger, and sin are used around the world to legitimate policy or to discredit it, to protect individuals from predatory institutions or to protect institutions from predatory individuals. Indeed, risk provides secular terms for rewriting scripture: not the sins of the fathers, but the risks unleashed by the fathers that are visited on the heads of their children” (Douglas, 1992: 26).

There are specific religious influences from the “Christian Bible” (Barrera, 2023) on policies and governance structures that establish incentives and accountability structures based on perceptions about the way God shows her favour. For instance, Psalms states, “Blessed is the man who fears the Lord, who greatly delights in his commandments! His offspring will be mighty in the land; the generation of the upright

will be blessed. Wealth and riches are in his house, and his righteousness endures forever” (Psalm 112:1–3). Similarly, Elder and Cobb (1983) connect Puritanism to our treatment and the underlying pursuit of plenty. They note that “to conquer the land and extract its riches was to do God’s work” (Elder and Cobb, 1983: 86). In addition, Merton (1968) explains that “The basic article of faith in this mystique is that you prove your worth by overcoming and dominating the natural world. You justify your existence, and you attain bliss by transforming nature into wealth.”

The impact of divine governance theory (Uche, 2019), “biblical capitalism” (McCloud, 2018: 15), and providencial private property on the policy process can be seen in many countries, but perhaps especially in the United States. Conger (2019) notes a key policy entrepreneur in Paul Weyrich. She writes, “Perhaps the most important, though largely underappreciated, architect of the Republican mobilization of conservative evangelicals was Paul Weyrich, a conservative Republican activist and operative who helped found the Heritage Foundation, the Free Congress Foundation, and the American Legislative Exchange Council.” The effect of free-market faith-based governance models is the idea that there must be “losers” for there to be winners. And if there is no difference between the prosperous and the poor then how does a concerned Christian know if they are acting correctly or if they are going to heaven? In this way, the promotion of equality may be considered an act of religious heresy that erases a person’s ability to measure their godliness (2 Peter 1:3) relative to others.

The infallibility of inequality and the subsequent artifice that equality represents are obviously much contested. Some would refer to seemingly opposite verses of the Bible and point out that in Matthew 19-20, Jesus Christ said: “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moths and vermin destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moths and vermin do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal.” As well as Psalms, which notes “For the needy shall not always be forgotten, and the hope of the poor shall not perish forever” (Psalm 9:18). The point of this analysis is to highlight the way the policy process can be seen to obey religious tenets and commandments and influence underlying cultural and political worldviews. Simply put, the public does not view winning the lottery, accumulating wealth, or even getting a “sugar daddy” as a punishment or sign of God’s wrath. Instead, the wealthy are elevated in the policy process to include the highest offices in the land. And both the public and policy support models of accumulation, “social envy” (Zitelmann, 2021: 211) and capitalism, which celebrates and necessitates that some will accrue wealth and be perceived as “winners” and some will be impoverished and be viewed as “losers.”

When pro-LGBTQ+ rights policies are enacted, the delivery of equality in the policy process is often not intersectionally sensitive because of inattention to the issues of inequality, the number of different groups affected by inequality, and the systemic reach of inequality across different identity groups. A common policy reaction is to stratify LGBTQ+ inequality by focusing on the identity group

that is the most complicit within existing policy dynamics and to reward them. This has the effect of reinforcing the inequality, underlying inferiority, and vulnerability of the entire community. The conditional and selective nature of LGBTQ+ equality grants legitimacy to the inattention that other members of the LGBTQ+ community receive, the stymied nature of social reactions, and is connected to an essentialist hierarchy of identities that is designed by those in power to maintain power.

The “durability of inequality” (Savage and Vaughan, 2024) and the resilience of equality in the policy process are relative to the structural biases that compromise the socio-political integrity of policy products related to inequality or equality and the power dynamics of identity groups involved. To be judged as unequal by a system and then to rely on that same system for relief requires a greater duty of scrutiny and care to the level of analysis and theoretical development than public policy and political science has yet to demonstrate (Prilleltensky and Gonick, 1996). Indeed, the systemic conditions of oppression that dominate the policy process to preserve inequality do not evaporate from structures and institutions when the same policy process is put under pressure to access an equality agenda as a way of avoiding political penalties. Here, we see many of the same conditions repurposed to establish the behaviors and identities that are required to qualify for equality from the state and the high-value constituencies that keep them in power. I refer to these policy reactions as “Soft Equality.”

In short, the queer, trans, and gender-diverse communities in the United States are highlighted here because they epitomise Tolerable Inequality. It is also worth noting that, as a field, political science does not have an unendingly successful record in addressing the connections between power; queer, trans, and genderdiverse lived experiences; and inequality. Smith and Lee (2014: 59) note, “although the scope of political science has, mercifully, expanded beyond a narrowly focused analysis of the exercise of power in the public realm of the state and the society of states, it has yet to fully incorporate analysis of the power relations in the ‘private’ realm and in particular around issues of sexuality, gender and the body.”

Literature Review

The academic literature across several disciplines supports the important roles these elements play as key aspects of policy studies. This includes the role of attention within bounded rationality (Simon, 1957), and the impact of affective primacy and risk to decision-making (Downs, 1972; Douglas, 1985; Slovic, 1987). In addition, expectations are part of a cognitive anticipatory framework (Miceli and Castlefranchi, 2015) that is linked to policy reactions and inactions based on the preferencing of loss aversion (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) and political self-preservation or “selectorate theory” (de Mesquita and Smith, 2002) by incumbent policy actors to negative feedback of expected penalties from highvalue constituencies. Lastly, the concept of identity is understandably broad, but

here it is used to highlight the way identity influences policy by organizing people (Crenshaw, 1991) and power (Lasswell, 1936; Schneider and Ingram, 1993) in ways that attract attention to collective social reactions. This includes evaluating the role of select identities as “political communities” (Arendt, 1973: 293) whose actions influence the policy process. In addition, the costs on institutions and actors in the policy process for working with or engaging on certain identity-based policy issues is revealed through intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991; Lorde, 1984), administrative burdens, (Spade, 2015), “loser” issues (Pepin-Neff, 2021), and the social construction of target populations (Schneider and Ingram, 1993).

This framework leans heavily on “selectorate theory,” where de Mesquita et al. (2003) note “Our theory depends partially on an understanding of coalition politics, and so we extract insights from the literature that ties coalition strategies to officeholding.” They add, this theory and analysis builds on work, “toward the pursuit and selection of policy outcomes and their linkage to maintaining oneself in office or throwing the rascals out (de Mesquita et al., 2003: 90).” In addition, political insecurity is instructive and defined by Rozenas (2016: 232) as “the degree of threat the incumbent faces from the opposition, in the form of a rebellion, a protest, or a coup. Incumbents who are facing a high degree of threat have an incentive to use elections to generate a public signal of their wide popular support and thereby deter challenges from the opposition.”

The issues related to inequality have been a priority across the social sciences. Erikson (2015: 12) highlights how “social scientists have taken the question of political inequality to heart.” The systemic way inequality is preserved in the policy process to serve as a political resource requires an examination using both existing policy studies literature and new ways of considering policy dynamics. To this point, Weible (2023) identifies public process research as, “the study of public policies and the complex interactions involving people and organizations, events, contexts, and outcomes over time. It involves various dynamics and manifestations of politics as people strive to influence the design and adoption of public policies that might ultimately change the course of societies.” As well as others like Easton (1955: 130) who note that “a policy … consists of a web of decisions and actions that allocate … values.” Here we see the way policy content is influenced by a system making it indistinguishable from the policy process itself. Public policy, therefore, is not a set of decisions about a set of problems operating independently of each other. But rather, public policy is a set of biased decisions upon which new conditions are filtered through calculations of survival. The goal of Tolerable Inequality is to provide an additional option to contemporary policy analysis and challenge the stratifications that incentivize essentialism, which provides both social status to elites and a way for incumbent policy actors to promote predictability in the policy process.

This book makes a proposition to add a new theoretical concept and policy cycle framework to understand the policy process. The underlying arguments that inform this Tolerable Inequality framework are based on (1) public policy literature and

research and (2) practitioner political experience, much of it outlined in a participant observer study in my research, including my previous book “LGBTQ Lobbying in the United States” (Pepin, 2021). In a review of the literature, there are important common threads as well as points of divergence between the popular policy studies research and the proposition that Tolerable Inequality and the Expected Penalty Policy Cycle (EPPC) make. Public policy literature has key frameworks and concepts that inform ways to look at attention, expectations, and identity in the policy process.

In one leading policy concept, Cobb and Ross (1997: xi) define agenda denial as “the political process by which issues that one would expect to get meaningful consideration from the political institutions in a society fail to get taken seriously.” Driving this agenda denial is the motivation of actors whose “interests would be ill served” by the policy process.

In this analysis, political penalties are the motivating principle of the policy process (Althaus, 2013). Penalties are defined as the pressures “that may reduce their [political actors’] ability to hold onto their office or further their ambitions” (Neff, 2016: 191). There is a strong connection between expected penalties and perceptions of political risk by incumbent policy actors. Althaus (2008: 67) reports on a study where “the interview results show that political actors principally understand a political risk to be a decision involving negative electoral impact or loss of government.” A penalty is perceived within an evaluative framework that includes both the expected presence of multiple (A) factors and the expected absence of multiple (B) factors. Pepin-Neff (2019: 51) notes that policy reactions are “based on the degree of political damage an individual actor or collective institution is willing to assume for the benefit of inaction.” In this analysis, there are two types of political penalties: expected and unexpected. However, the political penalty itself is based on the attention to negative social reactions by high-value constituencies regarding the unacceptable nature of a real or perceived deviation.

In many of the leading policymaking theories there is a focus on the nature of attention, including the “issue-attention cycle” (Downs, 1972) and the way policymakers focus selectively on certain issues based on the policy image that puts them on the agenda (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009), with the more attention they receive the greater likelihood of a policy window opening (Howlett, 1998) and greater potential to expand the conflict (Schattschneider, 1960) and introduce additional actors into a policy domain to challenge a policy monopoly (Jones, Baumgartner, and Talbert, 1993). In addition, Baumgartner and Jones (2009: 116) highlight the connection between attention and social reactions, stating “In reaction to the negative attention associated with the failed eradication campaigns in the late 1950s, of course a number of congressmen began to pay attention to pesticide issues where they had ignored them in the past.” They add, “issues can hit the agenda on a wave of positive publicity, or they can be raised in an environment of bad news. These two different mechanisms of agenda access have different policy consequences. High attention and positive tone can lead to the creation of powerful

institutions of government given broad jurisdictions over the policy, while high attention and negative tone often lead to subsystem dissolution” (Baumgartner and Jones, 2009: 119).

With regard to expectations in the policy process, there are two chief contributions. First,

Lowi (1964: 688) highlights the importance of expectations in the way they contribute to the nature of policymaking and the relationships they convey, the way expectations contribute to routine policy reactions, and the role of expected expectations in influencing policy. Here, Lowi (1964: 688) writes:

The scheme is based upon the following argument: (i) The types of relationships to be found among people are determined by their expectations-by what they hope to achieve or get from relating to others. (2) In politics, expectations are determined by governmental outputs or policies. (3) Therefore, a political relationship is determined by the type of policy at stake, so that for every type of policy there is likely to be a distinctive type of political relationship.

In addition, Lowi (1964: 689) notes the role of patterns and path dependent behavior that build expectations for the types of policies and policy tools that are enacted. He writes, “Issues as such are too ephemeral; it is on the basis of established expectations and a history of earlier government decisions of the same type that single issues are fought out.” Lastly, in the footnotes, in this analysis, Lowi highlights an important element (1964: 707) regarding the anticipatory (but not necessarily material) nature of expectation, stating, “As I argued earlier when defining redistribution, it is not the actual outcomes but the expectations as to what the outcomes can be that shape the issues and determine their politics.”

Two pieces of policy research stand out here: first, Hill and Varone (2021: 10) make an important argument in stating that “policy change is expected only when a particular issue attracts the attention of the media, interest groups, and elected officials.” Adding to this is Brandstrom and Kuipers (2003) contribution that “the political construction of the consequences matters more than the social consequences.” In this way, we see the incentives of incumbent policy actors tilt toward the pressures and penalties that come with attention and political consequences.

Cairney (2019) notes that “the study of power focuses on the extent to which inequalities in the possession of power translate into political outcomes.” The social reactions by high-value constituencies become negative and can potentially receive attention when there is an evaluation (social reaction) regarding a state of affairs, whose perceived reality deviates in unacceptable ways from the expectations that high-value constituencies hold. We often talk about this as a “deviation from the norm” and they are often linked to issues of identity and work across two directions. These deviations include when high-value constituencies feel LGBTQ+ rights have “gone too far” or “things are changing too quickly” from

the expectations that certain people had. Deviations can also be caused when highvalue constituencies are sympathetic to a deviation when a policy or law is at odds with an expectation and leads to a backlash, for example, wheret “same-sex loved ones should be able to visit their partners in the hospital.”

Secondly, the use of frames and narratives (Entman, 2007) determine the nature of the conflict (the size of the problem or deviation from expectations) that is played out through problem definitions (Houston and Richardson, 2000) and causal stories (Stone, 1989) discourse. For instance, the Multiple Stream Framework focuses on the role of policy entrepreneurs (Mintrom, 2000) to connect the three streams through the use of problem definitions that link problems and solutions (Kingdon, 1984).

In addition, identity is located in policymaking through the distribution of benefits and burdens in the social construction of target populations (Schneider and Ingram, 1993; Schneider and Ingram, 2005) as well as intersectional vulnerability (Crenshaw, 2013). While in sociology, the policy approach to moral panics (Young, 2011) is based on the social reaction to the perceived deviant action and the way socio-political labelling creates the deviants the state is trying to control. The policy challenge of addressing LGBTQ+ inequality centers focus on the need to shift this literature and expand on the roles of political penalties and power.

The EPPC is different in the direction and priority given to aspects of attention, expectations, and identity in the policy process. This includes the central functions around the presence or absence of political penalties as motivating factors in the policy process. This is important because it shifts the attention in the policy process from “issue attention” (Fagan et al., 2024) to a focus of attention on the social reaction of high-value constituencies. EPPC is connected to inequality in the policy process through the choices of actors and actions to use inequality to maintain their political positions. Ullman-Margalit (1977: 10) states, “In inequality situations the state of inequality is not completely stable; owing to its structure it is potentially threatened. The problem here is for the participant(s) favoured by the inequality to determine how to fortify the state against upset, or, put otherwise, how to maintain their favoured position.” Normative behavior is a social reaction including rulemaking, policing, obedience, repetition, convention, and conformity.

In the EPPC framework, it is the real or expected political penalty (Neff, 2016) that is motivated by political survival (de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson, and Smith, 2004), and political risk (Douglas, 2002; Althaus, 2013), in order to mitigate any negative attention to the social reaction by high-value constituencies. It may be that simultaneous attention (Birkland, 1997) to the deviation and the social reaction can impose the political penalty, but it is otherwise difficult to achieve in the absence of attention to a social reaction. The policy process, therefore, is focused on boundedly rational attention to social reactions, deviations (problem stream), harmonization (problem definitions and causal stories), and identity (the social construction of target populations). In addition, where the EPPC is different regarding expectations is on the relationship that matters, which is the one between the incumbent policy actors and the high-value constituents. It is the way their

expectations create negative social reactions to unacceptable deviations that may attract attention.

Indeed, the media are important members of the high-value constituency that keep incumbent policy actors in power driving attention to social reactions, establishing the nature of real or perceived deviations, and by constructing a common social reality. This includes networks, platforms, influencers, and celebrities. If there is an expectation or deviation that is out of alignment within a high-value constituency this increases the potential for attention to the negative social reaction that they and their fellow constituents are experiencing. Billard and Gross (2021) highlight the role of media, attention, and the policy process. They note, “Media play a key legitimating role for minorities in American politics. That is, it is media asserting the legitimacy of minority groups’ social and political claims that political elites and the public alike come to view their issues (and, oftentimes, their very identities) as worthy of attention” (Billard and Gross, 2021: 1343). This is particularly important to conceptions of social reality. In cultivation theory Billard and Gross (2021: 1346) note, “over time, media consumers come to view the real world as being like the mediated world, adopting factual, attitudinal and ideological perceptions that align with those dominant in the media’s message system.”

Finally, the connections between the identity of high-value constituencies, sympathy for deviations, and the identity of vulnerable identity groups locates identity in a slightly different position (closer to Lukes, 1974) because it considers the role, social reactions, and feelings of elite actors almost exclusively in the policy process. This uncomfortable element is contested by Tolerable Inequality by shining a light on power dynamics that motivate policymaking and the connections between power and policy and the nature of the social value of high-value constituencies, the diversity of actors in the policy process, and the dependent relationship between incumbent policy actors and high-value constituencies. Imbedded in this are systems and structures such as colonization that produce entrenched power dynamics. Hernandez-Truyol (2020: 1181) notes, “European colonization was inherently religious as European powers sought to “civilize” their colonial subjects through the influences of Christianity, civilization, and commerce. The religious influences that were embedded in the domestic laws of the colonizing nations were imposed on their colonial possessions, and they did not suddenly evaporate when the colonized peoples won their independence.”

This research distinguishes itself and makes an original contribution to policy studies by promoting a research agenda that examines the role of political penalties in the distribution of power and design of the policy process. This book represents an introductory study that also builds off the work of Bovens et al. (2008: 330) who note “the political dimension of policy evaluation refers to how policies and policymakers become represented and evaluated in the political arena. This is the discursive world of symbols, emotions, political ideology, and power relationships. Here, it is not the social consequences of policies that count, but the political construction of these consequences of policies, which might be driven by

institutional logics and political considerations of wholly different kinds.” In this case, I review how value-acceptable transphobia and homophobia are legitimated by public policies at local, state, and federal levels in governments around the world (Schneider and Ingram, 2005; Hellman, 2008). It is also important to note the contributions from the broader social movement literature, specifically Relative Deprivation Theory and the social psycology and sociology of political violence (Stouffer et al, 1949; Runciman, 1961; and Gurr, 1970). Smith and Pettigrew (2015: 2) define relative deprivation “as a judgment that one or one’s ingroup is disadvantaged compared to a relevant referent, and that this judgment invokes feelings of anger, resentment, and entitlement.” In all, I propose Tolerable Inequality as a conceptual lens to examine the promise of escalating marginalization across more groups of people through the policy process as the solution to many of the pressures, frictions, and penalties that elite actors face.

Tolerable Inequality and the Expected Penalty Policy Cycle

Public policy is part of the grand democratic experiment regarding how groups organize community because it is in policy that we look to establish the process for deciding on the collective rules of self-government, the prioritization of problems that matter, the identification of the people who matter, and the times and moments that matter (Pepin-Neff, 2021). Public policy is one mechanism that tests and affirms the relationship between citizens and the state in a continuous manner that is made real in the lives of individuals. The policy process is one of the foundations of trust and legitimacy that establishes a social contract between citizens and the state that underpins democratic governance. This test occurs one policy issue and problem at a time.

To understand the public policy cycle’s role in Tolerable Inequality, I center the influence of expected political penalties on incumbent policy actors. The policy process distributes inequality in unequal amounts and forces its citizens to endure agonizing episodes in a given time period. In these times and circumstances, incumbent policy actors galvanize all the powers of the state to minimize the damage they experience at the expense of some groups who will surrender their liberties and equality as a casualty of the terms under which the powerful are granted greater access to power.

The framework of the Expected Penalty Policy Cycle (EPPC) requires a focus on key variables and underlying assumptions. Kamarck (2013) identifies some of these variables, stating, “As many political scientists have noted, the challenge in studying policy change is that it encompasses everything from public opinion to institutional behavior.” “The problem,” according to Peter John (2003: 483), writing in the Policy Studies Journal, is the “absence of a clear chain of causation from public opinion to parties, and bureaucracies and back again.”

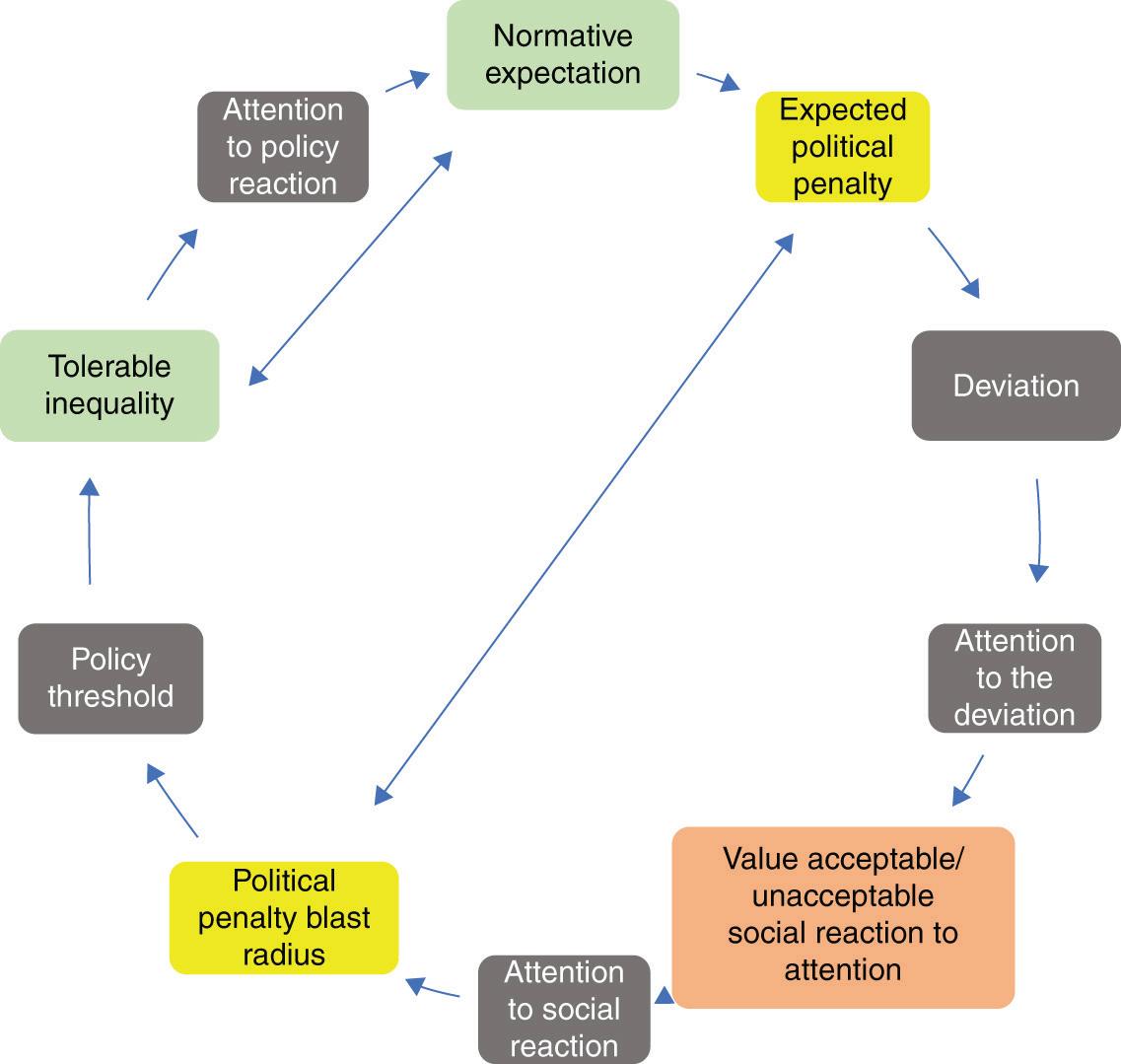

Chart 1 highlights the EPPC relationships between the (1) underlying normative conditions, (2) the occurrence of a real or perceived deviation, (3) attention to the real

or perceived deviation, (4) social reaction by a high-value constituency, (5) attention to the social reaction of the high-value identity group, (6) incumbent policy actors reacting to the expected political penalty, (7) the lowering of the policy threshold to facilitate a reaction, (8) the introduction of a Tolerable Inequality product as a method of mitigating attention to the deviation and social reaction either by reducing the occurrence of deviations, harmonizing the deviations to reduce the social reaction, or reducing attention to the social reaction. The cycle concludes (9) with attention to the policy reaction.

Tolerable Inequality analysis views the policy process as boundedly rational (Simon, 1990). Simon notes that, “the term ‘bounded rationality’ is used to designate rational choice that considers the cognitive limitations of the decision-maker –limitations of both knowledge and computational capacity. Bounded rationality is a central theme in the behavioural approach to economics, which is deeply concerned with the ways in which the actual decision-making process influences the decisions that are reached” (Simon, 1990: 15). The limitations and boundaries that are present in the policy process are used to institutionalize inequality against identity groups through points of resistance in policymaking, including social thresholds before policy windows will consider solutions (Kwak, 2017), administrative burdens to engage with bureaucracy (Spade, 2011), and material and emotional taxation for engaging on policy issues (Pepin-Neff and Caporale, 2018).

There are three additional behavioral assumptions that underlie either: the expected political penalty from negative social reactions from high-value constituencies (de Mesquita et al., 2005), the anticipated satisfaction that dynamics of comparable inequality will provide to high-value groups as the solution to status-based expectations (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999), and the level of expected resistance and taxation that vulnerable groups expect to receive from incumbent policy actors in exchange for a remedy to the deviation of inequality from the policy process (Johnson, 2012). These assumptions establish the predictability of high-value constituencies to both unacceptable deviations from the norm and value-acceptable discrimination, which return equilibrium to the policy process and affirm power dynamics.

As a consequence of this perverse incentive structure, public policy is designed to elicit certain shared social reactions from different constituency groups that ultimately support and legitimize the underlying governance structure of the policy process (Ellis and Faricy, 2011). For instance, Ellis and Faricy (2011: 1105) reflect on their study of thermostatic responsiveness to social policy by stating “the public is responsive not to the total amount of social spending, but rather to the ideological direction of that spending, and the relative balance of spending across direct and indirect means.” However, if state systems and institutions prioritize only those whose social reactions and lived experiences are deemed politically valuable and relevant to the policy process, then this may inhibit the potential for shared experiences with sympathetic communities and attract attention to the shared social reactions. These are the factors that serve as current incentives for the policy process to care about an individual or group relative to their own self-preservation and therein lies a problem.

The inattention to inequality, harmonizing of prejudice, and equality governance shape value-acceptable social reactions that incentivizes state-sanctioned suffering toward certain groups without political penalties directed at incumbent policy actors. Here, inequality is viewed as an asset of incumbent policy actors because it provides them with a predictable device with which to manage potentially unpredictable (and politically dangerous) situations. The obfuscation or introduction of inequality into the policy process helps incumbent actors satisfy the expectations of high-value constituencies that keep them in power. Indeed, Tolerable Inequality is a preferred set of policy reactions to policy problems for the incumbent powerful because they are based on the precept that the behavior of high-value constituencies is predictable when it incorporates social stigma and stereotypes.

Tolerable Inequality is useful as a lens for examining policy dynamics because it identifies the ways incumbent policy actors try to keep power through incentive structures and accountability mechanisms that reward the mitigation of political penalties through the introduction of harmonization tactics. Velthuis et al. (2021: 1106) defines tolerance as “a counteracting force against suppression and negative interference, allowing dissenting others the right to lead the life that they want.” Here, the Council of Europe notes, “material deprivation and disempowerment create a vicious circle: the greater the inequality, the less the

participation; the less the participation, the greater the inequality” (Carmona 2013: 5, quoting Council of Europe 2013). These policy reactions, tactics, and solutions distribute Hard and Soft Equality as well as Hard and Soft Inequality products. This includes resistance points to restrict and balance expectations and promote consequence-free environments that lack accountability. Moreover, it is not just that other penalizing variables are not there, but that the design of the policy thresholds and structural flexibility of institutions that cue the penalty excludes their absence intentionally. The blast radius of expected political penalties is therefore based on the way certain elements create pressures on incumbent policy actors and others do not. In other words, the penalty is created by the presence of certain variables and by the absence of others – you cannot put bars on a prison and ignore the importance of the space between the bars. The fact that incumbent policy actors can rely on the absence of certain forces (namely vulnerable groups) that may not introduce penalties in the policy process establishes a boundary to the blast area of an expected penalty that is relied upon in the critical way actors judge the expected nature of political penalties.

Pepin-Neff (2019: 39) note:

The distribution of penalties from highly emotional issues and events often present foreseeable political circumstances. Policy subsystems and domains are designed with political penalties in mind because the strength of a subsystem may mitigate the degree of penalty elected officials face. Tiplady et al. (2013: 882) notes these expectations around animal cruelty stating, “politicians are well aware of community concerns and expectations about this ‘emotionally charged’ issue.”

This analysis embraces Lukes’ (1974) position regarding the three faces or dimensions of power. This book asserts that the ability to exercise power for one’s own benefit (A’s control over A), is consistent withe the literature which is referred to as the first face of power. This is relative to systemic and structural oppression that deprives individuals of the resources and capacity needed to oppose oppression (A’s resistance to B) which includes increasing the costs imposed, resistance structures introduced, and the enactment of administrative burdens. Perhaps most important is the agreement that both measurable and unmeasurable aspects of power relations are exercised in the policy process. Inattention and inaction are deliberate actions that stabilize policy monopolies of inequality. Inattention and the ability to keep issues off the agenda is referred to as “covert power” (Lukes, 1974). In the policy process, attention is a device of Hard Inequities whereas Soft Equality is translucent where equality withers under the light of attention like Target (AP, 2024), Bud Light (Holpuch, 2023), and corporate equality measures (HRC, 2024). Hard Inequality is a hardship and cost. It is about the resistance to the direction of the social and political cost. Equality should be cost-free based on the distribution of basic human rights we are all born with.

Tolerable Inequality is distributed through Hard and Soft Equality to avoid the political penalties that make incumbent policy actors vulnerable.

Policy thresholds that open and close policy windows manage the implementation of different faces of power. Policy thresholds that require certain levels of activity or action before a policy window opens provide an important way of identifying levels of tolerability for certain issues and groups in the policy process (Howlett and Cashore, 2009). Thresholds provide a means of avoiding penalties by distributing Tolerable Inequality in the policy process because the distribution of inequality can limit the number of actors and issues involved as well as offer pre-packaged solutions and policy options that possess value-acceptable discrimination, including policy actions, statements, and tools to align with biases that produce behavioral predictability and give the incumbent policy actors an advantage. Crucially, the natural state of the policy process is closed to protect those in power. Therefore, policy is most often about how to avoid political penalties through inaction. Pepin-Neff (2019) noted that “policy threshold levels are based on the degree of political damage an individual actor or collective institution is willing to assume for the benefit of inaction.” Democratic policy processes negotiate the threshold for responding to highly emotional issues based on political distress.

Boven and t’Hart (1996: 12) discuss thresholds as “zones of tolerance” in which an issue or event has moved something from a normally accepted situation to something problematic. This institutionalization of second-class status allows incumbent policy actors to escape the expected blast radius of any political penalties associated with this discrimination. Moreover, public policy can be designed to distribute emotions in ways that limit how many people care, how much they care, and for how long they care because this can lead to political penalties (Pepin-Neff, 2019). This enacts the third face of power: latent power. Under this analysis, policies and processes also filter how many people experience a deviation, how large the deviation between expectation and reality is perceived to be, how many people share the reaction of an unmet expectation, and for how long there is focused attention on this deviation (Lukes, 1974).

Policy thresholds are also designed to allow for emotional expressions (PepinNeff, 2019). These may include public apathy and inattention or public concern and catharsis. Policy can be a primal scream or carefully honed tool. Policy is one way that society communicates through tragedy. It is important from the outset to highlight the role of emotions in public policy. There are times when the public desperately needs a policy to work in response to a social problem, which means there is a degree to which policy action and inaction can provide a symbolic but effective placebo effect that allows the public to shift its emotional disposition and move forward to find relief from a moment of need. The result is a system of cooperation and negotiation between citizens and the state that demonstrates tolerance and intolerance to different groups and issues at different times.

In all, establishing prejudice as a pillar of the policy process allows governments to contain or re-direct attention, contain or re-direct social reactions, shift the valuation of social reactions or change the expectations regarding deviations in order

to harmonize perceptions of expectations or reality, and limit the real or perceived occurrence of unacceptable deviations. Therefore, when Tolerable Inequality is weaponized in the policy process, it applies pressure to marginalized groups across the three faces of power, affirms the expectations of high-value groups, and grants predictability incumbent policy actors regarding public behavior.

Inattention, Harmonization, and Equality Governance in the Policy Process

A key feature of Tolerable Inequality are the tactics of inattention, harmonization, and equality governance which are the way incumbent policy actors have designed the policy process to avoid political penalties by creating policy environments that satisfy the expectations of high-value constituencies. These policy reactions are designed to normalize the dynamics of inequality by quelling attention toward deviations, quelling resources, ensuring “oser” issue status, and shaping social reactions that ensure the vulnerable are unsympathetic and stigmatized. Each of these tactics delivers inequality (Soft or Hard) as a reliable tool of control in the policy process and resource for incumbent policy actors that they use in varying degrees and duration to avoid exposure to political penalties and maintain power.