Cogent Social Sciences

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: www.tandfonline.com/journals/oass20

The offices of the U.S. president as policy tools

Chris Pepin-Neff, William McManus & Ben Ormerod

To cite this article: Chris Pepin-Neff, William McManus & Ben Ormerod (2023) The offices of the U S president as policy tools, Cogent Social Sciences, 9:1, 2225335, DOI: 10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

© 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Published online: 04 Jul 2023.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1078

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www tandfonline com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=oass20

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

Received: 24 October 2022

Accepted: 09 June 2023

*Corresponding author: Chris PepinNeff, Discipline of Government and International Relations, School of Social and Political Sciences,The University of Sydney NSW, Room 460, Social Science Building A02, Camperdown, Australia

E-mail: Chris.pepin-neff@sydney.edu.au

Reviewing editor: Robert Read, Economics, University of Lancaster, UK

Additional information is available at the end of the article

POLITICS & INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | RESEARCH ARTICLE

The offices of the U.S. president as policy tools

Chris Pepin-Neff1*, William McManus2 and Ben Ormerod3

Abstract: White House spaces and offices are not created equal. The spaces that constitute the offices of the president are distinctive, familiar, and publicly translatable assets of statecraft. Whether in the Oval Office, the Treaty Room, aboard Air Force One, or even in the Rose Garden their use is designed to deliver information and send an influential signal to the public. Many of the offices of the president have their own cognitive profiles in the public’s mind. The utilization of physical spaces establishes a repertoire of routine and ritual that informs the public about how important a potential policy issue is. The question driving this research asks: How do the physical offices of the president function as policy instruments? We argue that physical offices can be considered policy tools under categories of (1) nodality, when they are employed as a tool to publicly rally around a policy decision and (2) authority, when they serve as a heuristic regarding command-and-control to the public. In short, the physical offices of the president facilitate policy adoption by serving as devices to communicate information about the direction and gravity of a policy decision.

Subjects: Congress; Presidency; Government; Public Administration & Management

Keywords: Presidency; policy tools; White House; cueing; visual politics

1. Introduction

The offices the President of the United States serve to further policy goals. The Oval Office in the West Wing of the White House provides a grand setting for announcements, and Air Force One commands attention. These physical spaces provide the backdrop for the Executive Branch. Indeed, they represent an important function as a communication device of both material and symbolic benefit to statecraft. This article is a theory building exercise that looks at the physical offices of the United States presidency as policy tools. We ask, how do the physical offices of the president function as policy instruments? We argue that the offices of the president serve as policy tools under two leading conditions: (a) nodality, where the offices themselves communicate information to the public in ways to rally the public around a policy decision, or (b) authority, which includes command and control of spaces that provide a cognitive heuristic about the gravity and direction of policy decisions. This article articulates the role of policy tools that relate to

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Chris Pepin-Neff is an American- Australian Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the University of Sydney. His research looks at agenda setting and emotions.

William McManus be a medical student at the University of Sydney, whose research also looks at policy tools.

Ben Ormerod is a research student in the Discipline of History at the University of Sydney. His research focuses on historical memory and propaganda.

© 2023 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The terms on which this article has been published allow the posting of the Accepted Manuscript in a repository by the author(s) or with their consent.

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

nodality and authority categories. Or put another way, there is a relationship between the use of policy instruments (nodality and authority) which highlights the selection of deliberate spaces, the perceived meaning behind these spaces, and the efforts of the White House to use these locations as sites of persuasion for the President. Here we see that the offices and spaces of the President illustrate the importance of optics and visual policy tools to cue the public in favor of a policy position (Pearson and Dare, 2016).

To begin, policy tools are defined as “the devices government have at their disposal for implementing policies” (Howlett et al., 2009, p. 87). The central policy tools of this analysis are outlined by Hood (1986) and include public information campaigns (nodality) and instruments of state power (authority). The offices of the president function as policy tools when they facilitate topdown policymaking or encourage policy adoption. These tools are an important area of study because the way in which policy tools are used to convey adoption of a policy illustrates relationships between the public and the president and between the state and the individual. Or more simply, we see a political environment built around certain visuals that connect specific buildings and spaces to feelings and ideas. The offices give people the feeling of reassurance and security. Walker et al (2020) note that information-based policy tools “communicate knowledge or information seeking to shift the audience’s behavior in a direction favorable to public policy objectives (Hood and Margetts, 2007; Howlett, 2019).”

Importantly, we consider what makes an office of the president an office. We define an office based on four factors: first, that an office is a room, group of rooms, building, or vehicle designed for the purposes of the president to carry out his or her work. This includes an assemblage of furniture and key furnishings that service the presidency and include the Resolute Desk and presidential rug in the Oval. In other words, a purposeful space and associated objects that furthers the functioning of the Office of the Presidency is an office of the president. In this way, the whole White House (from the Oval, the Treaty Room, or the Situation Room to the private study) are all designed to accommodate the president and meet his or her needs.

Second, an office of the president is relative to the president and does not extend to the staff who serve the formal Office of the Presidency. Third, offices can be temporal rather than stationary or moveable. The president determines the type of space, rather than the space determining the type of president. In Skowronek’s (1997) The Politics Presidents Make, he identifies a typology of time for change. In relative terms, the way a president makes use of the moment depends on how she makes use of the office. For instance, Carter could not really use the Oval Office effectively; however, Reagan often did.

Fourth, the physical space and offices around the president are part of the conveyance of authenticity, authority, and legitimacy to the officeholder. The office is a device for the staging of statecraft. She is recognizable as president, in part, based on the object’s proximate to him or her and their surroundings. The physical environment of the president is therefore an aspect in the execution of actions and the delivery of executive authority. In addition, the physical space and offices around the president confer legitimacy on the office-bearer.

The research question posed is important because the offices of many chief executives function as visual policy tools which make them an area for historical policy inquiry and research. Analysis of presidential offices—and the relationships individual presidents had with their offices—is an underdeveloped topic for academic analysis. Wider examinations of the American presidency often neglect how presidents came to utilise the spaces and optics available to them as policy tools, or indeed how the use of these offices changed between presidents.

Moving forward, we note the methods used to look at this information, conduct a literature review to build a theoretical concept, which looks at the utilization of presidential spaces, the role of policy tools, and the image of the space being recognized by the public as important and

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

appropriate. This is followed by three potential hypotheses to guide future research. We conclude this article with thoughts about the future of research in this area.

2. Materials and methods

The methods used to help explain this theory-driven article are centered on presidential utilization rates. To establish the principle of utilization rates for specific spaces and offices, three publicly available data sets are used. The relationship between the data sets and the theory-building goals of the paper center on the way spatial utilization helps the White House influence and persuade the public.

First, the Oval Office and presidential use of the Oval Office for national addresses is reviewed. Data was collected based on a combination of publicly available sources as well as the American Presidency Project. This data set highlights the shifting uses of the Oval Office, the potential theoretical opening regarding the Oval Office as a visual policy tool and persuasion and illustrates the need for further study.

Second, data is collected regarding the presidential use of space for Supreme Court nominations (1971–2022). Here, data is collected from Google searches and publicly available White House archives. This information connects a key persuasion element in the American presidency, Supreme Court vacancies, and the president’s intent to influence the Senate and the public to support his selection.

Third, data analysis regarding President Obama’s press conference venue utilization was generated through the cross-referencing of the American Presidency Project’s index list of Presidential News Conferences and the Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Barack Obama. The American Presidency Project’s database lists every news conference by a president, defined as an “interaction between the President and multiple members of the press in a relatively formal setting,” while the Public Papers include the location of every Presidential News Conference. President Obama’s potential venue shopping around the White House speaks to the deliberative nature of White House communication. Together, these examples of office and space utilization illustrate the nature of the questions this article raises and help to craft the initial hypotheses noted below.

3. Literature review

In this section, we build our theoretical lens around two sections to establish the terms for consideration of the research question. First, a review looks at the literature around nodality and authority instruments in the policy process. Second, empirical data is used to highlight three areas that illustrate a gap in the literature and an opportunity to connect spatial analysis with the White House and policy tools. This data is used to generate observations that can be used in the crafting of initial hypotheses in this section. In all, the empirical data underpins and establishes the nature of the theoretical question: How do the physical offices of the president function as policy instruments?

We propose that the utilization of space by a president is both an act of policy and politics. Empirical data is introduced around President Obama’s press conference locations. In addition, the potential usefulness of this analysis is highlighted by the way rooms and spaces around the president are used as visual policy tools to convey and cue narratives. Each element yields observational hypotheses to move this research forward.

4. Reviewing policy tools

Policy tools are instruments of implementation and adoption in the policy process. Weiss (2002, p. 1) notes that “a massive proliferation has occurred in the tools of public action, in the instruments or means used to address public problems.” These are rooted in the policy tools literature,

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

Table 1. Policy tools in the NATO model applied to

US Presidents Nodality Authority

Passive information sharing

White House Easter Egg Roll (Reagan)

Advice and Exhortation

Fire-side chats (FDR)

Reagan’s speech in West Germany

Obama’s speech at the funeral of John Lewis

Advertising

Just say no (Reagan)

White House campaign to prevent youth opioid abuse (Trump)

Campaign to convince Americans to get vaccinated from COVID-19 (Biden)

Commissions and Inquiries

Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States (Biden)

The President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (Johnson)

Command and control regulation

Ordering troops into the Persian Gulf (George H.W. Bush)

Ordering troops into Iraq (George W. Bush)

Issuing the order to kill Osama Bin Laden (Obama)

Self-regulation

Condom use when having sex (Clinton)

PreP HIV-prevention adoption (Obama)

National Maximum Speed Law (Ford)

Standard-setting and delegated reputation (Bar association)

Priorities of the DOJ Civil Rights Division (Obama) Service regulations for gays in the military (Obama)

Ready to Read, Ready to learn reading program (George W. Bush).

Advisory Committees and Consultations

The Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS (Clinton)

National Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee (Biden)

which includes: (a) nodality, which is political communication; and (b) authority, which refers to facilitating the execution of presidential orders (see Table 1).

The table below illustrates use of nodality and authority and examples where these might apply across Presidential behavior. For instance, nodality includes passive information sharing, such as the message from the president to the public on the White House Easter Eggs as well as advice (i.e. Fire Side Chats) advertising (i.e. Just Say No), and commissions (i.e. JFK assassination). Authority tools are noted and include command and control (i.e. Iraq War), self-regulation (i.e. speed limits), standard setting (i.e. environmental regulations), and advisory committees (i.e. HIV/AIDS councils).

4.1. Public information campaigns (nodality)

Hood (1983) notes that nodality is a passive instrument of information distribution that can include press releases, advice to the public, and advertisements (see Table 1). Government communication as a policy tool is addressed by Capano and Howlett (2022: 346), who highlights the nodality frame as “the use of government informational resources to influence and direct policy actions through the provision or withholding of ‘information’ or ‘knowledge’ from societal actors.” Public information campaigns are also a tool of government use that are noted by Schneider and Ingram (1990). Here they look at symbolic or hortatory actions that are underpinned by the fact that “people are overloaded and behave based on internal beliefs and values. They rely on heuristics to navigate decision-making. In this way, we see the use of offices as representative symbols to exhort and frame the greatness of America by connecting familiar images with attentiveness.

The offices have social value and hold political capital with the public. To employ an office as a government communication policy tool is to connect its positive valence with the president in ways that soften, toughen, amplify, both the present moment and the media replays where most people will catch a snippet of an orchestrated policy rollout by the White House (Durant, 2006). In this way, offices serve as a sort of information framing device item that has the potential to raise the level of emotional support for the president by being surrounded by these familiar, positively affected social instruments. Items such as paintings and adornments are displayed to highlight family values, pictures are selected that the President identifies with, and television or computers come and go as technology and security demands change.

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335 https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

Public information campaigns can also be seen in nudge theory where the focus of the individual or collective is shifted to influence behavior (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Nudging is a policy tool that was first developed in the United Kingdom as a means of dealing with austerity by addressing “choice architecture.” Nudge is a top-down strategy that adopts bounded rationality and prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Oliver (2013, p. 11) states that, “The core essence of the approach is that behavioral economic insights—such as loss aversion, probability weighting, present bias and a host of other findings can and should inform the design that Thaler and Sunstein (2009) call the choice architecture, or in other words, the context or the environment, so that people are more likely to make voluntary decisions that, on reflection, they would like to make and yet, due to bounds on their economically defined rationality and human error, ordinarily fail to do so.” Framing tools in nudge theory are a top-down model that involves “Altering the belief content” through problem definitions and causal stories backed by trustworthy authorities.” The offices of the president help establish who is publicly seen as a trustworthy authority.

4.2. Command and control (authority)

A second type of policy tool is command and control regulations (Hood, 1983). Authority tools are also noted by Schneider and Ingram (1990) as statements backed by authority in which the underlying understanding is based on the fact that people are “compelled with or without incentive based on power.”

The Offices of the President serve as devices that amplify the visibility of an issue and hasten the broad dissemination of information. Edelman (1985, p. 105), states, “the analogue for public policy formation is clear. Unless an appropriate political setting has been created, legitimizing a set of values and a mode of access, a group interest cannot be expressed in policy.” The setting of nearly every White House policy announcement is orchestrated by staff to meet a formula that maximizes the likelihood of public understanding and adoption. In this way, the offices of the president are integral to transmitting a message about a policy enactment and implementation of policy as a matter in the national interest. As a public information instrument, the physical spaces and offices of the president can, by their very incorporation in a policy environment, increase the level of salience for an issue and raise awareness.

To facilitate its use as state power, the White House received a $3.4 million upgrade in 2017 (Puhak, 2017). While Trump received some criticism for allegedly calling the residence a “dump,” current and former administration staffers have admitted the property could use some sprucing up. The renovation, approved during the Obama administration, included updating a 27-year-old HVAC system, upgrading IT systems, and repairing the South Portico steps for the first time since the Eisenhower administration. Much like any fixer-upper project, though, the structural changes gave the new administration a chance to change the décor.

In addition, there are reports that former President Trump was considering not leaving the White House following the 2020 election (Haberman, 2022). Presidents may act as advocates for themselves in the way they use the offices. President Lyndon Johnson used the Oval Office to impose himself on others, even raising his chair higher than his guests on Air Force One. And it is hard to get blunter than Nixon’s use of the presidential helicopter as the stage from which he waved a sign of victory before resigning the office and leaving the White House. The offices also provide a communications strategy. This was also seen recently by former President Trump, who used the White House in 2020 as a backdrop for a campaign event in violation of the Hatch Act (Behrmann, 2020).

5. Considering available data on White House utilization

In this section, we identify and demonstrate that there are potential implications for utilization trends around the physical spaces and offices of the president. This is essentially about the relationship a president may have with his or her surroundings in order to perform their work. Second, we note the literature that underpins visual policy tools to cue perceptions and feelings

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335 https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

towards the public. Understanding the interplay between physical space as a tool to send a message, signal and feeling to the public is important because it is here that three elements are distinguished. And third, we examine the way images of the space are recognized by the public. In this way our theory-building centers on the physical space, the orchestration of that space for policy gains, and the role of the public in seeing the visuals as expected and appropriate.

The president may occupy a White House room without a space serving as a policy tool. In addition, the public may be familiar with a room, but it does not act as a policy instrument. It is the combination political goals or policy outcomes and the utilization of spaces that activates the president’s offices as policy instruments. Or put more simply, when an office is used to influence the public, the public sees an office and are cued to take it onboard. Here, presidents rely on this affective response at certain occasions to facilitate visual policy toolmaking.

5.1. The utilization of space and rooms related to the presidency

The choice about which offices to use for certain events and how frequently informs the way visual policy tools are used in presidential persuasion. Edelman (1985, p. 96), notes that “the settings have a vital bearing upon actors, upon responses to acts, and especially upon the evocation of feeling.” Therefore, a president may venue shop (Pralle, 2003) around the White House looking for a setting to match the message. Additional literature generally looks at connections to space and policy. Stead (2021) notes that policy tools can be used to look at spatially in urban planning. In addition, Howlett et al. (2009) addresses government communication as a policy tool.

For instance, if an administration governs by press conference, then the location of the press conference is key. The setting defines the political actor as themselves as much as it defines the policy. An example includes President Bill Clinton, who chose the Roosevelt Room to issue his most memorable statement, “I want you to listen to me. I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky. I never told anybody to lie, not a single time, never” (Rothman, 2015).

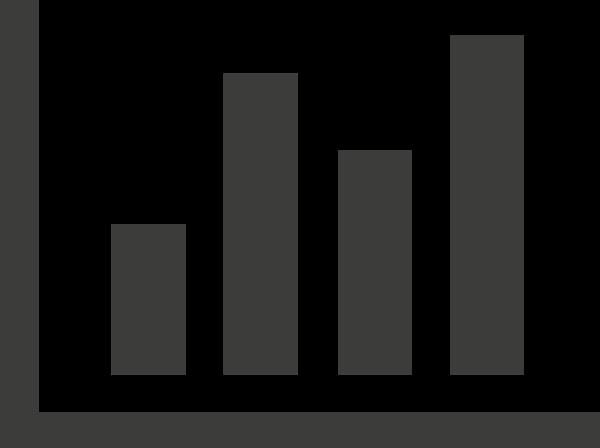

For instance, Figure 1 looks at President Obama’s space utilization over his eight years of press conferences. Here we see that President Obama utilized the East Room most frequently followed by the Brady Briefing Room and the White House Rose Garden. This useful data helps to establish trends in presidential behavior and space utilization (see hypothesis 1).

However, there is also a question regarding the relative availability of a president. Press conferences may be difficult to measure if the President prefers small gatherings of the media before getting on or off Marine One. Grossman and Kumar (1981, p. 304) note that, “while the White House is concerned with the President’s problems of sending communications to his various publics and constituencies, the representatives of news organizations are fulfilling institutional goals of keeping the public focused on what they consider to be the newsworthy activities of the President.” As a result, there may be degrees of access to the media that are established for press conferences and other public events.

Figure 1. Obama press conference utilization of White House venues 2009–2017.

These choices in usage can also be seen by Tchou (2010) who reported that “Obama does much of his day-to-day work—such as editing speeches and reviewing papers—in the President’s Study, located off the Oval Office, and in the Treaty Room, on the second floor of the White House.” Tchou (2010) adds, “Many recent former presidents—including both Bushes, Carter, Ford, and Johnson— chiefly worked out of the study as well.”

In addition, the HSS Treaty Room is part of the residence and is a study for the president. The treaty to end the Spanish-American War and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty were signed here. It was from here that President George W. Bush announced that the U.S. war in Afghanistan had been launched. President Obama’s use of the Treaty Room in the executive residence was a very public part of his presidency. It feels as if there was a concerted effort by Obama’s people to show him spending late nights in the Treaty Room working to the point that it became an image of his presidency. There were two important factors that made this a significant office to President Obama (a) his un-wavering demand for family time in his daily timetable, and (b) the work ethic he wanted to portray to his country.

Hypothesis one connects two of the elements of the theoretical lens: office utilization and public support. Here, we propose that the offices and spaces are used to promote and sustain turnout and support, which may be most likely among the core constituencies of a president.

Hypothesis 1: The use of Offices and spaces as policy tools will lead to an increase in public support for the President’s agenda

5.2. Use as a policy tool to convey and cue policy

Many of the offices of the president have their own cognitive profiles in the public’s mind. This includes establishing a repertoire of routine and ritual that creates an emotional connection (Pepin-Neff and Caporale, 2018) to certain objects, spaces, and rooms. From the West Wing and the Roosevelt Room to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), offices offer the visual, physical characteristics that constitute the publicly recognized trappings of the presidency. Or put another way, when the public sees familiar offices or adornments, this meaning is added to the context of the information (see hypothesis 2). Here, we see the use of the offices of the presidency to anchor public information efforts mentally or emotionally. Weiss (2002, p. 219) notes that “in fact, nearly all policy-related information has both cognitive and normative content.”

Policy tools make certain cognitive assumptions, including that people are boundedly rational (Simon, 1990). Bounded rationality is concerned with behavioral decision-making, not aggregate behavior. Under this concept, there are procedural limits on decision making (attention and time) and substantive limits (over-cooperation). The theory is based on the premise that attention is time dependent. Limited

Court Nomina on Announcement Loca ons (1971-2022)

Figure 2. Supreme court nomination announcement locations at the White House.

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

time, limited resource capacity for memory, and emotional coping mean that policy tools must consider and employ methods that tap into these elements to achieve policy adoption.

Figure 2 highlight that not all offices and spaces are used equally by the President. The data from President Obama’s SCOTUS nominee announcements specifically demonstrate that he went against the general trend by relying on the optics of the East Room, whereas the overall press conference data highlights the utilization of the Press Secretary Podium in the Brady Press Briefing Room in the West Wing as the most used with six announcements, followed by the Rose Garden, Cross Hall and the East Room with four announcements, and the Oval Office with two Supreme Court announcements. Two additional points come from this data. First, President Reagan seemed to prefer the look of the White House Press Briefing Room for SCOTUS nomination announcements and conducted four nominations in this location. Bill Clinton favored the pomp of the Rose Garden for his two nominations while George W. Bush appears to have preferred the Cross Hall except in light of the gravity of his nomination for John Roberts nomination as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and Harriet Miers as Associate Justice, which is demonstrated by the selection of the Oval Office for these events. Again, President Obama seemed to prefer the picture of the East Room but wanted to send a different message with Merrick Garland in the Rose Garden.

Human limitations on comprehending the environment and the complexity of the environment compromise the ability to optimize utility. Therefore, we see the use and reliance on heuristic short-cuts, causal stories, myths, symbols, and other path dependencies by governments. Edelman (1985, p. 172) notes “mass publics respond to currently conspicuous political symbols: not to ‘facts,’ and not to moral codes embedded in the character or soul, but to the gestures and speeches that make up the drama of the state.”

Hypothesis two suggests that there may be certain rooms for certain issues. The situation room comes to mind for military affairs, while the Rose Garden for Supreme Court nominations, and the East Room for press conferences.

Hypothesis 2: Presidents are more likely to select rooms or spaces to help covey a message consistent with a theme when nominating supreme court justices.

The familiar physical offices and surroundings of the presidency provide an important service as cognitive heuristics that convey both the symbolic and material authority of the president to enact policy to the public. In this role, the use of television and still pictures as principle mediums to transmit and communicate messages, information, and a picture that wraps around the delivery of the message and information are essential. For instance, Keltner (2009, p. 517) notes, “The American media have traditionally acted as an intermediary between the president and the public, thereby influencing public opinion of the president’s policies, activities, and personality traits.” Indeed, television has changed the functionality of presidential offices. For instance, the first television in the limousine was designed for Reagan. In contrast, there were three televisions in the Oval Office for LBJ.

5.3. Image of the space being recognized by the public

The third element that informs this lens and theory building exercise is the role of the public in recognizing the cues and coming into contact visually with the message being sent. This affects both nodality and authority and is important because the offices convey trust, and trust underpins legitimacy, which makes presidents more persuasive and better at influencing policy adoption (see hypothesis 3). Weiss (2002, p. 225) notes that public information campaigns are a key policy tool that “must deliver this information in a way that the audience will notice, believe, and act upon.” Indeed, there is a connection between research on the offices of the presidency and the roles and responsibility of the president. According to Neustadt (1960), “Presidential power is the power to persuade.” And some of this power resides in the prestige of the presidency that comes from the way in which she occupies the space. Neustadt (1960, p. 150) notes: “a President . . . makes his personal impact by the things he says and does.” Therefore, the presidential powers of the

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

executive branch rely on the benefits of the physical offices of the president. The offices are used to set the political stage and define the context of the situation for policy.

Figure 3 combines present data with information from the American Presidency Project. It highlights Oval Office utilization rate for national television addresses broken down by the average number of television addresses per year in Office. This data shows that Nixon and Reagan had the most Oval Office addresses, while President George W. Bush, Obama, and Trump had the fewest contemporary Oval Office addresses. Offices themselves can be used as blunt force venues of political action. For example, Figure 3 highlights the use of spaces by presidents to nominate justices to the Supreme Court. Here, we see the prominence of the Rose Garden, Press Secretary podium, and the East Room.

To be accepted and affirming as a visual policy tool, the instrument must be regarded as appropriate for the circumstance (e.g. the right room with the right environment) and be expected by the public. Edelman (1985) looks at the importance of political settings as symbols in the policymaking process. For Edelman, it is about both the appropriate framing and the expectation of the appropriate setting or staging and evocation of feelings by the public. Edelman (1985, p. 95) notes that “great pains are taken to call attention to setting and to present them conspicuously, as if the scene were expected either to call forth a response of its own or to heighten the response to the act it frames.”

We suggest that the offices of the president function as visual policy tools, which include campaigns such as “Smokey the Bear” and tobacco warning labels (Weiss, 2002, p. 217). This is consistent with Peter John (1988: 27) who states, “The speech communicating the enactment of a policy and the plan for implementation is a key action in the policy process.”

This research provokes a question about the selection of a room and the level of importance of an issue and their reliance on familiar spatial or visual environments.

Hypothesis 3: Presidents are more likely to select familiar rooms or spaces when delivering press

perceived as politically important.

In all, the operationalization of visual policy tools may translate into establishing the props and setting to frame the policy agenda. The key factor here is the way the setting reinforces the message, focus, and attention. Peters and Hogwood note (1985), “that officially scheduled political events, such as annual budgets, speeches from the throne, or presidential press conferences, can spark media coverage and thus draw public attention, reversing the purely reactive causal linkages attributed to political actors by Downs.”

Figure 3. Average Oval office television addresses per year in office.

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335 https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

6. Discussion

In this paper, we have introduced the idea that the offices of the president can be used as visual policy tools because they help cue attention from the public. This occurs based on the selection and utilization of certain spaces by the president, the built in cues that that establish emotions and meaning for those offices, and the public’s familiarity with the spaces themselves. These three elements are important because for this policy arrangement to work there must utilization and availability by the President, and feelings of expectation, familiarity, and acceptability by the public. The task now is to locate visual policy tools with examples in such a way that we highlight the connection of these three elements.

6.1. Serve as a cognitive heuristic regarding command-and-control directives to the public

The physical spaces of the presidency, his or her key offices, help presidents persuade policy actors and the public by serving as symbolic set pieces that establish the legitimacy of the presidency. This includes several roles, such as chief executive, head of state, commander in chief, or even leader of the free world. To facilitate the image of the presidency includes advertisements that are often photo-ops and television appearances, which establish publicly recognized norms around power dynamics. This includes the way the power of the offices can lead to intimidation. Whether that is Trump or LBJ, here, the offices serve as touch points of the presidency and an institutional mechanism (Hart, 1995). Exhortations facilitate the prestige and greatness of America. In this case, we highlight the role of Camp David, Air Force One, and Walter Reed Medical Center.

Air Force One serves as both the most functional and the most imposing asset of the presidency. According to the White House (2022), “Air Force One is one of the most recognizable symbols of the presidency, spawning countless references not just in American culture but across the world. Emblazoned with the words ‘United States of America,’ the American flag, and the Seal of the President of the United States, it is an undeniable presence wherever it flies.” Air Force One is one of the most iconic images of the might of the American Presidency. The plane is the bridge that connects the president to all of the U.S. and the rest of the world.

For instance, the first time that the oath of office was administered to a president in an airplane was at Love Field in Dallas, Texas, in 1963. The historical picture of President Lyndon Johnson taking the oath alongside Jacqueline Kennedy is an indelible element of American presidential history. Indeed, the visual theatre of that moment—to be sworn into office onboard the presidential plane following an assassination and to use the plane as a location of safety as well as a prop to affirm the presidential nature of the event—is tangible.

Second, the utilization of the office is designed to transmit an emotion to the public about the gravity or direction of a policy issue. Grave matters of state may be addressed in the Treaty Room, Situation Room, Oval Office, or aboard Air Force One. President George W. Bush famously stayed aboard Air Force One for eight hours following the events of 11 September 2001, using it as a War Room to devise a response. Graff (2016) recounts, “Shortly after the attacks began, the most powerful man in the world, who had been informed of the World Trade Center explosions in a Florida classroom, was escorted to a runway and sent to the safest place his handlers could think of: the open sky.” The picture of President George W. Bush on the phone in Air Force One was designed to convey calm and control in the midst of catastrophe.

In addition to historic occurrences on Air Force One, it was also designed around small details to establish the greatness of the president. According to Lim (2022) President Lyndon Johnson “had an infamous, special on-board desk chair that was equipped with a hydraulic lift to ensure that he was at least eye-level with or higher than the person he was speaking with.”

Obama made it very well known how important his family was to him. He was adamant that two hours were put aside each night for family dinner, a time where, realistically, most other presidents

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

would still be at work. Obama had to compensate for this allocated time by taking work home with him and reportedly almost daily spending the hours of 9 PM-1 AM working in the Treaty Room. Pragmatically this is a suitable office, away from the bustle of the Oval Office, in the comfort of his family home, still close to his staffers who were also no doubt more often than not working. Politically, it was an effective tool to show his “family man” image whilst highlighting his work ethic, which contributed to his popularity. We argue that this office, whilst practically sensible for his personality and needs, also served to develop his public image.

6.2. Rally the public around a policy decision

The Oval Office is the throne-room of the American presidency. Borchers (2015) notes for the Washington Post that there is no substitute for the gravitas of the Oval Office. Brooks (2011) outlines how the decoration of the Oval Office has been integral to the branding strategy of various presidents. These offices are part of the expression of the president. Franklin Roosevelt is the modern inventor of the most famous presidential office, the Oval Office. Hoover used the EEOB following the fire in 1929. The Obama White House notes that the Oval Office is the “Official office of the president and his primary place of work” (White House.gov, 2012).

The uses of the Offices of the President help to define the context and the nature of the policy adoption being sought. The White House is the stage that informs many policy discussions. The connections between pomp and policy presents an important facet of physical space as a form of political resource management. Indeed, the relationship between presidents and their physical surroundings has an impact on the policy process. Each office contributes to the presidency based on the interaction of the president with the space.

In addition to national addresses, the Oval Office is used to host guests and meetings. It is considered an honor to be invited into the Oval Office and it can be intimidating to attend a meeting there with the president. Indeed, one of the Oval Office’s real functions is as a device of persuasion (C. L. Pepin-Neff, 2021). President Lyndon Johnson maintained his vice-presidential office after the assassination of President Kennedy out of respect, and only used Oval Office as the public/ceremonial office. This is consistent with Edelman’s (1985) analysis that for the public to engage on an issue it must see the president as expectantly and appropriately using the offices at his or her disposal. This use as a public office seems to have carried forward to a degree. Indeed, the Oval is given contemporary designs to facilitate the needs of the president with a familiarity to the public.

In addition, there are more contemporary questions about designate access to technology in each room and the effect this has on office utilization. Lemire and Mcgraw (2022) report that, “the White House has largely abandoned using the Oval Office for press events in part because it can’t be permanently equipped with a teleprompter; Biden aides prefer the fake White House stage built in the Old Executive Office Building next door for events, sacrificing some of the power of the historic backdrop in favor of an otherwise sterile room that was outfitted with an easily read teleprompter screen.”

The final space to be noted as a policy instrument is Ground Force One, which was commissioned for President Obama in 2012 for his campaigning and was an important part of maintaining his responsibilities as president whilst travelling the country. The black bus was designed by the Secret Service, with security at the forefront of the design and was fitted out with a “full suite of office equipment.” This functionality limits the time cost and tactical vulnerability to the President of the United States. Ground Force One could be glossed over as a rather inconsequential part of Obama’s presidency but we argue that it played an interesting role in Obama’s public relations (Bender, 2016). It put into contrast the president’s selfless image whilst treating himself to a brand-new campaign wagon. It enabled Obama to fulfil his requirements as president whilst travelling the country campaigning. Travelling the country, visiting constituents, schools, universities, state organizations, hospitals, defense bases and so on would be an admirable duty for a president to take on.

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335 https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

Moving further afield, this research leads to more questions. For instance, are there other White House events or souvenirs (e.g., White House Easter Eggs) that convey mental shortcuts of information. Or international comparisons that can shed additional light on the connection between physical offices and policy tools? The French President works in the Golden Room of the Elysée Palace. This comparison with the uses of the Oval Office will be a focus of future research. In addition, how does the space influence the types of decisions that are made in those environments? For instance, would policy decisions be more likely in certain offices during emergencies (aboard Air Force One, Marine One, or the Situation Room)? Do the rooms function within a bureaucratic or procedural routine of policy protocol? Or put another way, are there matters of state that are distributed to certain types of offices, such as the Roosevelt Room and Oval Office for domestic policy and Treaty Room for international affairs? Finally, this research asks who the key political actor is influencing the decision who may affect the physical location of the president. Does the Secret Service, the White House Chief of Staff, the first spouse, campaign manager, or the president themself determine their location?

7. Conclusion

In closing, the physical spaces and offices that surround the president play a central role in the performance of the presidency. This study asked: How do the physical offices of the president function as policy instruments? We argued that the offices of the president serve as policy tools under two conditions: (a) when they serve as a cognitive heuristic regarding command-and-control directives to the public; or (b) are employed as a tool to rally the public around a policy decision. We have set forward a theory-building exercise in which the physical spaces that surround and facilitate the functioning of the American presidency are important policy instruments for each United States president. Interplay between offices and policy as a function of staging and ritual inform the policy adoption process. Whether used as props to reassure an anxious public, the setting for a tone of legitimacy, or to rally and unify a nation in one policy direction, the physical offices that encircle or travel with the president are designed to influence the way the public understands, accepts, and adopts policy decisions made by the executive. The representation that surrounds policy proposals is therefore crucial to their style of governance and effective policy adoption. This article looks at the offices of the president as policy instruments and tools that are designed to enrapture, intimidate, and glorify certain aspects of the policy process. In this way, the information conveyed is both familiar and clear because the physical surroundings establish a governmental hierarchy. The offices send a strong signal that is vital in the president’s role as persuader-in-chief.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Australia and recognize their continuing connection to land, water and culture. We have written this article on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present, and emerging. This land was never ceded, this is and will always be Aboriginal lands. We would also like to acknowledge a few individuals without whom this article would not be as complete. Emily Manche, Scott Penton, Ira Escandor with special thanks to Professor Rodney Smith and the anonymous reviewers.

Author details

Chris Pepin-Neff1

E-mail: Chris.pepin-neff@sydney.edu.au

ORCID ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4218-7040

William McManus2

Ben Ormerod3

1 Senior Lecturer in Public Policy, Discipline of Government and International Relations, School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney NSW, Camperdown, Australia.

2 School of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney NSW, Camperdown, Australia.

3 School of History, The University of Sydney NSW, Camperdown, Australia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Citation information

Cite this article as: The offices of the U.S. president as policy tools, Chris Pepin-Neff, William McManus & Ben Ormerod, Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335.

References

Behrmann, S. (2020). RNC: Trump criticized for using White House as a backdrop for the convention Retrieved August 25, 2020, from https://www.usa today.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/08/ 25/rnc-white-house-convention-speeches-ethicshatch-act-trump/5628864002/

Bender, J. (2016). Meet ground force one, the president’s $1.1 Million Armored Bus. Business Insider Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3Cgydn3 Borchers. (2015). Callum the Oval Office address ain’t what it used to be. But it’s still pretty powerful. The Washington Post Brooks, D. S. (2011). Political decorating and branding: A historical retrospective of the oval office interiors from 1934 to 2010. Journal of Interior Design, 36(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1668.2011.01063.x

Pepin-Neff et al., Cogent Social Sciences (2023), 9: 2225335

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2225335

Capano, G., & Howlett M. (2022). Instrumentation in policy design: Policy tools-from devices to activators Research Handbook of Policy Design Edward Elgar Publishing. Durant, R. F. (2006). A ‘New Covenant’ Kept: Core values, presidential communications, and the paradox of the Clinton presidency. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 36 (3), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5705. 2006.02552.x

Edelman, M. J. (1985). The symbolic uses of politics University of Illinois Press.

Graff, G. M. (2016). We’re the Only Plane in the Sky. Politico Magazine Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://politi.co/3CfY5Q5

Grossman, M., & Kumar, M. J. (1981). Portraying the president: The White House and the news media Johns Hopkins University Press.

Haberman, M. (2022). Confidence Man: The making of Donald Trump and the breaking of America Harper Collins. Hart, J. (1995). President Clinton and the politics of symbolism: Cutting the White House staff. Political Science Quarterly, 110(3), 385–403. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2152570

Hood, C. (1983). The tools of government (1st ed.). Macmillan Education UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-1-349-17169-9_1

Hood, C. (1986). The tools of government Chatham House Publishers.

Hood, C. C., & Margetts, H. Z. (2007). The tools of government in the digital age Bloomsbury Publishing.

Howlett, M. (2019). Designing Public Policies Principles and Instruments (Routledge).

Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., & Perl, A. (2009). Studying public policy: Policy cycles and policy subsystems (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

John, P. W. (1998). Statistical design and analysis of experiments. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Keltner, K. (2009). Residential leadership, symbolism, and television: A case study of the apollo program. White House Studies, 8(4), 517.

Lemire, J., & Mcgraw, M. (2022). A Biden-trump rematch is increasingly likely. But neither side wants to move first. POLITICO. Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://politi.co/3VaCW2h

Neustadt, R. E. (1960). Presidential power New American Library.

Oliver, A. (2013). From nudging to budging: Using behavioural economics to inform public sector policy.

Journal of Social Policy, 42(4), 685–700. https://doi. org/10.1017/S0047279413000299

Pearson, L. J., & Dare, L. (2016). Visuals in policy making: ‘See what I’m saying. In G. Stoker & E. Mark (Eds.), Evidence-Based Policy Making in the Social Sciences: Methods that matter (pp. 123–140). Policy Press.

Pepin-Neff, C. L., & Caporale, K. (2018). Funny evidence: Female comics are the new policy entrepreneurs. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(4), 554–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12280

Pepin-Neff, C. L. (2021). LGBTQ Lobbying in the United States Routledge.

Pralle, S. B. (2003). Venue shopping, political strategy, and policy change: The internationalization of Canadian forest advocacy. Journal of Public Policy, 23(3), 233–260. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X03003118

Puhak, J. (2017). White House unveils new $3.4 million renovations Fox News 9 https://www.foxnews.com/ real-estate/white-house-unveils-new-3-4-millionrenovations

Rothman, L. (2015). The story behind bill clinton’s infamous denial Retrieved January 26, 2015, from Time magazine. Available from: https://time.com/ 3677042/clinton-lewinsky-response/

Schneider, A., & Ingram, H. (1990). Behavioral assumptions of policy tools. The Journal of Politics, 52(2), 510–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131904

Simon, H. A. (1990). Utility and probability. In Bounded Rationality (pp. 15–18). Palgrave Macmillan. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20568-4_5

Skowronek, S. (1997). The politics presidents make: Leadership from John Adams to Bill Clinton The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Tchou, A. (2010). Does Obama actually work in the oval office? Slate Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https:// bit.ly/3T3po6W

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness Penguin Books.

Walker, P. G. T., Whittaker, C., Watson, O. J., Baguelin, M., Winskill, P., Hamlet, A., & Djafaara, B. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in low- and middle-income countries. Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 369(6502), 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc0035

Weiss, J. A. ( 2002 ). Public information. In Lester M Salamon & Odus V Elliott (Eds.), The tools of government: A guide to the new governance (pp. 217–254). Oxford University Press.

The White House. (2022). Air force one. The White House Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3Cg7UgN