TheCostsofPride:SurveyResults fromLGBTQIActivistsinthe UnitedStates,UnitedKingdom, SouthAfrica,andAustralia

ChristopherPepin-Neff

ThomasWynter

UniversityofSydney

Acomparativeanalysisofemotionaltaxationwasconductedtoinvestigatetheaffectivecost ofenteringthepoliticalprocessamong1,019lesbian,gay,bisexual,transgender,queerand intersex(LGBTQI)activistsintheUnitedStates(n ¼ 355),theUnitedKingdom(n ¼ 230), SouthAfrica(n ¼ 228),andAustralia(n ¼ 206).Fourconsistenttrendswereidentified acrossthesefourcontexts,withimportantimplicationsforthestudyofsocialmovements, youthactivism,gender,sexuality,andrace.First,levelsofemotionaltaxationresulting fromLGBTQIactivistworkwereconsistentlyveryhigh.Second,emotionalburdens weresystematicallygreaterforyoung,nonwhite,andtransgenderactivists.Third, emotionaltaxationwascompoundedforactivistswhoseidentitiescrossedmultiple marginalizedgroups.Thisfindingsupportsthevalidityandimportanceofintersectional approachestoLGBTQIissues.Fourth,thesourcesofemotionaltaxationvariedgreatly amongactivists,andtransgenderactivistswereparticularlystressedbypublicengagements suchasmajoreventsandmarches.Transgendernonwhiteactivistsalsoindicated relativelyhighlevelsofemotionalstressrelatedtoonlineformsofengagement,suchas postingonTwitterandFacebook.Thesefindingscouldhelpidentifythekindsofactivists whoparticipate,thekindsofissuesadvocatedfor,andwhycertaintacticsareused.

Keywords: Intersectionality,socialmovements,agendasetting,emotions,emotional taxation,survey

Thetwomostcommonwordsusedbylesbian,gay,bisexual, transgender,queer,andintersex(LGBTQI)activistrespondentsto

PublishedbyCambridgeUniversityPress1743-923X/19$30.00forTheWomenandPoliticsResearchSectionofthe AmericanPoliticalScienceAssociation. # TheWomenandPoliticsResearchSectionoftheAmericanPoliticalScienceAssociation,2019 doi:10.1017/S1743923X19000205

498 Politics&Gender,16(2020),498–524.

describetheirexperienceofworkinginthemovementare“rewarding”and “empowering.”YetworkingasanactivistintheLGBTQImovementcan beextremelydifficult,withgreatpersonalcost.Thenextmostcommon descriptorswere“challenging,”“frustrating,”and“exhausting.” Understandinghowthepressuresofactivismimpactactivistsisacritical questionforgenderstudies,publicpolicy,socialmovementstudies,and thesocialsciencesmorebroadly.Weinvestigatedthefollowingresearch question:WhataretheemotionalcostsforLGBTQIactivistsinthe UnitedStates,UnitedKingdom,SouthAfrica,andAustralia?These countrieswereselectedbecauseeachhasacontemporaryLGBTQI history,allowsfortheorganizationofactivists,andhasresponsiveliberal stateinstitutions.EachofthesecountrieshasevolvedregardingLGBTQI rights.Althoughsomehavebeenmoreacceptingthanotherswithregard tobisexual,transgender,andintersexidentities,theacronymLGBTQIis broadlyusedasanumbrellarecognitionthateachidentityintheactivist communityplaysarole.

InAustralia,theAustralianFirstPeoplesengagedin“homosexual practices”(Baylis 2015,6).ThecolonialinvasionofAustralia1788setthe lawsthatwouldgovernhomosexualityandgenderfornearly100years.In 1970,theDaughtersofBilitisstartedasalesbiangroupasdidthe CampaignAgainstMoralPersecution(CAMP),demonstratingtheearliest organizationofLGBTQIactiviststhere(Moore 1995,319).Inresponseto organizedgroupssuchasthese,lawsbegantochange.Militaryservicewas legalizedin1992(Rimmerman 1996,21),andsodomywasillegaluntil 1997,whenitwasoverturnedfollowingadecisionbytheUnitedNations HumanRightsCommittee(Berman 2008).Same-sexmarriagewas legalizedinAustraliain2017(McAllisterandSnagovsky 2018).

IntheUnitedKingdom,theHomosexualLawReformSocietywas formedin1958toadvocateforthelegalizationofhomosexuality (DavidsonandDavis 2004).In1963,theMinoritiesResearchGroup wasformedforlesbianstoaddresearchtothedebateabout homosexualityinthemedia(Hopkins 1969,1434).TheCampaignfor HomosexualityEqualityfollowedin1964(KentCityCouncil 2011), andStonewallUKwasformedin1989tolobbyagainstunfairlaws (Barkeretal. 2011).In2000,theUnitedKingdomliftedthebanon homosexualsinmilitaryservice(HelferandVoeten 2014),andsame-sex marriagewaslegalizedinEnglandandWalesin2014(Eekelaar 2014).

IntheUnitedStates,theSocietyforHumanRightsinChicago,thefirst LGBTQIgroup,formedin1924(KepnerandMurray 2002,25),followed bytheMattachineSocietyin1951(Adam 1995,67),whichorganized

protests.TheGayActivistsAllianceofNewYorkformedinthe1969, followingtheStonewallriots(Armstrong 2002,87).Activismaround humanimmunodeficiencyvirus/acquiredimmunedeficiencysyndrome (HIV/AIDS)in1987alsoledtothefoundingofACTUP(Gould 2009, 129).Lawsbeganchangingafterthe2003 Lawrencev.Texas decision decriminalizedsodomy.Thesechangeswerefollowedin2011withthe repealofthebanongay,lesbian,andbisexualserviceinthemilitary (NeffandEdgell 2013,233).Marriageequalitywasgrantedin2015 (Faderman 2015,635).

InSouthAfrica,LGBTQIgroupsformedinthe1970sand1980salong racialorethniclines.Thedownfallofapartheidaccompaniedanincrease inrightsforLGBTQIpeople.In1996,SouthAfrica’sconstitution guaranteedtherighttonondiscriminationtotheLGBTQIcommunity (Currier 2010).Inaddition,thegovernmentallowedserviceinthe militaryin1996regardlessofsexualorientation(Cock 2003).Sodomy wasdecriminalizedin1998andgaymarriagewaslegalizedin2006 (Currier 2012).IntermsofNGOs,theLesbianandGayEquality Projectwasfoundedin1994.Notably,however,inSouthAfrica,alevel ofviolenceagainsttransgenderpeopleremains.A2016surveybythe OtherFoundationfoundthat“Abouthalfamillion(450,000)South Africansovertheprior12months,havephysicallyharmedwomenwho dressedandbehavedlikemeninpublic,and240,000havebeatenup menwhodressedandbehavedlikewomen”(7).

Ourhypothesisbuildsontheintersectionalityliterature(Crenshaw 1991;HillCollinsandBilge 2016)toanalyzethesurveyresultsfrom thesecountries.

H1: Peoplefrommultipleminoritygroupsexperiencegreateremotional costsandburdensimposedonthemfortheirengagementinthepolicyprocess thanthosewithmorepositivelyconstructedidentities.

Werelyontheconceptofemotionaltaxation,whichNeff(2016)defines asfollows:“Emotionaltaxation orthe taxationofemotions istheemotional cost,intentionalornot,thatapolicy,program,orschemeplacesonan individualorgroupforenteringintothepoliticalprocessoraddressinga politicalissue.”

Emotionaltaxationistheemotionalcostforengaginginthepolitical process(Pepin-NeffandCaporale 2018).Itfunctionsasanagendasettingandmobilizationconceptbecausetheleveloftaxationimposed onanindividualorgroupcanpushthemtowardorinhibitthemfrom politicalaction.Itisrelativetopower,capacity,andcollectivesupport,

whichmeansthatsociallyconstructedidentitieswithgreaterpowermay experiencelessemotionaltaxationandmayhavemorecapacitytobear thecostsofpoliticalengagement.Thisstressmaylessenwiththesupport ofothers.

H2: PoliticalpowerofatargetpopulationisconsistentwithSchneider andIngram’s(1993) analysisonhierarchiesofidentityandincludesthe waybenefitsandburdensaredistributedtogroupsbasedonpowerand identity.

Thevariabilityofcapacityofemotionaltaxationextendsfromthetheory ofemotionallabor(Hochschild 1983)definedaslaborthat“requiresoneto induceorsuppressfeelingsinordertosustaintheoutwardcountenance thatproducestheproperstateofmindinothers”(7).Accordingtothis theory,emotionsarearesourcethatcanbetapped.Theindividual’s capacityto“paythecost”isafunctionthatmaybehinderedby oppression,discrimination,orothersociallyorphysicallydebilitating conditions,connectedbystructuralinequity(Crenshaw 1991;Lang 2000).Thelackofcapacitytoabsorbtheburdenmakestheexperience oftheleveloftaxationhigher,whereastheabundanceofcapacitylowers emotionaltaxation.Asaresult,activistsmaydesignlesstaxingactivities orissueagendas.Alternatively,activismonhigh-taxationissuesortactics mayproduceburnoutand/orforceactiviststoleavethemovement altogether.Collectivesupportcanalsoaffectlevelsofemotionaltaxation inavarietyofways.Itcanreducetaxationwhensupportfromothers lessensthedegreeofindividualvulnerability.Thismayalsobethecase ifthemobilizationofothersdetermineswhethersomeoneisinitiatingor followingtheactionswithinthepoliticalprocess.Insummary,being singledoutcreatesamorevulnerablesituationandimpliesahigherlevel ofemotionaltaxation.

Theemotionaltaxationconceptextendstheworkon emotionalhabitus byBourdieu(1977)andothers.Anemotionalhabitusistheconnection betweenemotionsandpolicyissuesthatdefinesthenormsandthe politicaltrajectoryofanissueforacommunity.Forinstance,Gould (2009)looksattherolethatemotionalhabitusplaysindefiningthe politicalpossibilitiesaroundHIV/AIDS.Shearguesthatthe1986 SupremeCourtdecision Bowersv.Hardwick,whichdeniedLGBTQI peopleanyrightsundertheconstitution,createdarupturethatchanged theissueofAIDS.Whatbeganasanemotionalnarrativeofdesperation towardafatalmedicalconditionshiftedintoastoryinwhichgaymen

werebeingassassinatedbythejudicialandpoliticalprocessonthebasisof theiridentity.

Theconceptofemotionaltaxationisalsoconsistentwiththeway emotionalstimuliarediscussedintheagenda-settingliterature,which includestheoriesofthepolicyprocess,crisismanagement,and behavioralpublicpolicy.Forinstance,inresearchonmultiplestreams theory,Kingdon(1984)notestheimportanceofpublicmoodand Zahariadis(2007)postulatesthewayemotivefeaturesmaybeusedto manipulateactors.Policyentrepreneursusepublicattractiontocertain emotionalissuestoadvancetheirissuesintheagendaandinfluence policyoutputs(Mintrom 2000;Pepin-NeffandCaporale 2018).

Theadvocacycoalitionframework(SabatierandJenkins-Smith 1988) alsorecognizestheroleof“devilshift”(Sabatieretal. 1987)inmotivating actors,inwhichextremelynegativefeelingsaboutanopponentinfiltrate anorganization’swayofthinkingandoperating.Understandingthese motivationsisimportantbecauseofthepotentialforabuseinthe politicalsystem.Sabatieretal.(1987)state,“Devilshifthasallthe worstfeaturesofapositivefeedbackloop:themoreoneviews opponentsasmalevolentandverypowerful,themorelikelyoneisto resorttoquestionablemeasuresto preserveone’sinterests”(471).In addition,punctuatedequilibriumtheory(BaumgartnerandJones 1993)makesakeyunderlyingcontributionasatheoryofinformation processing.Itfocusesonattentiveness,whichisimpactedby emotionalityandinfluencesthepolicyimage.AsTrue,Jones,and Baumgartner(2007)state,“Policyimagesareamixtureofempirical informationandemotiveappeals”(161).

Overall,emotionaltaxesareorganizedininstitutions,structures, politicalgroups,andsociallyrecognizedhierarchiesofidentitytoconfer emotionalrewardsuponpoliticallypreferredgroupsandemotional burdensuponstigmatizedgroups.

H3: Drawingonintersectionalityliterature,weexpectthatbeinga memberofmultipleminoritygroupshascompoundingeffects.

Wetestedthishypothesisthroughacomparativeanalysisof emotionaltaxationrateswithinandbetweengroups.Inthe remainderofthisarticle,wedescribeourmethodologyandpresent theresultsofoursurvey.Wediscusskeyfindingsandexplainwhy thesequestionsandresultsmatter.Weconcludewithpolicy suggestionsandfutureresearch.

EMOTIONSINPUBLICPOLICY

ThisresearchregardingthelivedexperienceofLGBTQIpeoplehasbeen conductedatatimeofheightenedemotionalstakesfortheLGBTQI community.Followingvictoriesregardingmarriageequality(Ball 2016), significantgapsinequityforLGBTQIpeopleremainintheUnited States,theUnitedKingdom,SouthAfrica,andAustralia.Forinstance, transgenderpeopleofcolorremainsubjecttohighratesofviolenceand murder.Youthhomelessnessandyouthsuicideremainatepidemic levels,andreligiousexemptions(Haider-MarkelandTaylor 2016,46) threatenworkplaceemployment,housing,andcommerce.Additionally, restrictionson“safeschools”programstocombatbullyingarestill provocativeissuesinmanylocations.

Furthermore,webelievethat“groupswithingroups”deserveimportant attentioninthepoliticalscienceliterature.Resourcesaredirectedin heteronormativeandhomonormativewaystowardissuesthatfavorwhite, cisgender-male,andgayidentities.Oneexampleisthewayfundshave beendirectedtowardmarriageequalityintheUnitedStates.Thisissue isaluxuryitemforeliteswhencomparedtoLGBTQIissuesof homelessness,youthsuicide,domesticviolence,orseniorisolation. Moreover,Gorski(2018,13)positsthatintergroupconflictistheleading contributortoactivistburnout.

Thisstudyaddsquantitativedataandanalysistoconsiderationsof burnout,minoritystress,andintersectionality(see,e.g.,Crenshaw 1991; Srivastava 2006).Forinstance,Herman(2013)buildsonMeyer’s(1995, 2003)modelofminoritystressforLGBpeople.Meyer(1995)states, “Psychosocialstressderivedfromminoritystatus”functionsonthebasis that“gaypeople,likemembersofotherminoritygroups,aresubjectedto chronicstressrelatedtotheirstigmatization”(699).Herman(2013) extendsthisanalysistothetransgenderpopulation,statingthat “TransgenderandgendernonconformingpeopleacrosstheUnited Statescertainlyaresufferingthenegativeimpactsandconsequencesof distalandproximalminoritystressors”(66).Indeed,theeffectof directingpoliciesthatimposeanemotionaltaxonanalreadyoppressed targetpopulationsuggestsadisproportionateimpact(Schneiderand Ingram 1993).Ourfindingsareconsistentwiththeliteratureon intersectionalityandthewayoppressedgroupswithmultiple marginalizedidentitiesexperienceacutediscriminationatthe intersectionofthoseidentities(seeCrenshaw 1991;Pepin-Neffand

Caporale 2018).Fundamentally,structuralandhierarchicalsystemsrender theseidentitiesvulnerable.

Theutilityofemotionaltaxationisthatitallowsfortheinterrogationof theroleofemotionsinsocialmovements,interestgroups,lobbying, politicalengagement,andotherpoliticalsitesofpower.Marcus(2000) states,“Aconsensusontheeffectsofemotioninpoliticsremainstobe achieved”(222).Incorporatingemotionaltaxationrelatesnotonlytothe literatureoncapacity(Lang 2000)butalsotoburnout(ChenandGorski 2015;Gorski 2018;Pines 1994).Theissueofburnoutisparticularly importantforpoliticalactivismbecauseitinvolvesbothphysicaland mentalstressorsforlong-termactivists.

Pines(1994)notesthatforpeoplewhochoosepoliticalactivism,“The stakesinvolvedareveryhighbecausetheyaretryingtoderivefromtheir workorpoliticalinvolvementasenseofmeaningfortheirentirelife” (390).Toanalyzepotentialburnout,“interviewersinquiredaboutthe mostpressingmentalhealthproblemexperiencedbymembersofthe protestmovement”(ibid.).Thesestressorscancomefromexternal influencesaswellasinternalones.ForGorski(2018),internalconflicts presentthegreatestthreattoburnoutwithintheracialjusticemovement: “All30participantsattributedtheirburnouttohowactiviststreatone another.Manybecameworndownattemptingtonavigateactivist communitiesinwhichin-fightingandegoclasheswerecommonplace” (679).Intheirstudyof1990speaceactivists,MaslachandGomes(2006) foundthat“relationshipswithotheractivists”werethemostfulfilling, buttheywerealsothemoststressfulintheiractivistwork(47).

Inthepresentstudy,webuiltonthisresearchbyaskingactivistsabout theirmentalhealthexperienceasacomponentofemotionaltaxation. Althoughemotionsarearesource,theydonotfollowasimplecost–benefitcalculation.Agivendegreeofemotionalityrelativetoavailable capacityisnotalwayspredictiveofalevelofindividualorcollective engagement.Sometimesthereisnocostapersonorgroupisunwilling tobeartoadvancetheirsocialandpoliticalaims.

METHODOLOGY

Recruitment

Inthisstudy,weemployeda37-questionsurveyusingQualtricssoftware. Facebookadvertisementswereusedasthedistributionmechanismfor thesurveylink.TheFacebookadvertisementwastitled“2017LGBTQI

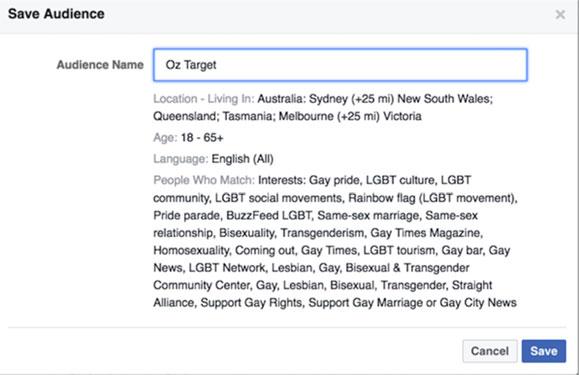

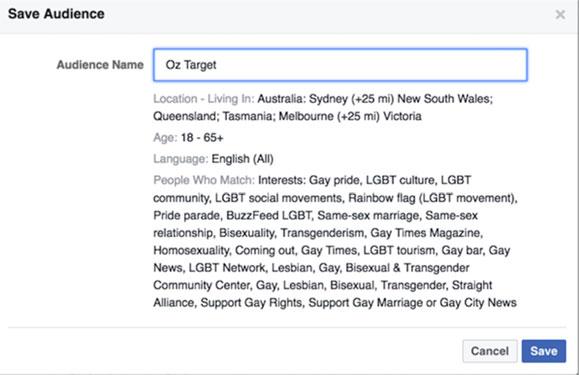

ActivistSurvey,”andittargetedpeople18–65 þ yearsofage.Asstated, “Thegoalofthesurveyistolookatthefeelingsandperceptionsofthose onthefront-lineofthemovement.”Wesoughttorestrictthesampleto thepopulationofinterest—LGBTQIactivists.AsMeyerandWilson (2009)state,“InvestigatorswishingtostudyLGBpopulationsmust ... devotesignificantenergyandresourcestochoosingasamplingapproach andexecutingthesamplingplan,”andhistorically,“toobtainlarger samplesofLGBswhilereducingthecostofprobabilitysampling, researchershavetargetedgeographicareaswithgreaterdensityofLGBs (‘gayneighborhoods’)”(23). Figure1 illustratestherecruitmentselection criteriafortheadvertisement,whichincludedsearchtermsconsistent withonlineneighborhoodsofLGBTQIactivism:“gaypride,”“rainbow flag,”“same-sexmarriage,”“comingout,”“LGBTcommunitycenter,” “GLBTstraightalliance,”and“supportgayrights.”

Respondentswerepartofadigitalconveniencesampleinwhich participantsvolunteeredtocompletethesurvey.Thus,cautionshouldbe takeningeneralizingthefindingstothebroaderLGBTQIactivist community.However,despitethislimitation,suchconcernsaboutthe dataaresubstantiallyallayedbytheirconsistencyacrossinternational locations.Regardingonlinesurveys,Eysenbach(2004)notes,“Biascan resultfrom(a)thenonrepresentativenatureoftheInternetpopulation and(b)theself-selectionofparticipants(volunteereffect)”(e34). However,onlinesampling“canalsofacilitateaccesstoindividualswho aredifficulttoreacheitherbecausetheyarehardtoidentify,locate,or perhapsexistinsuchsmallnumbersthatprobability-basedsampling wouldbeunlikelytoreachtheminsufficientnumbers”(Fricker 2008, 17).DatacollectionwithintheLGBTQIcommunityisnotoriously difficult,andtheuseofFacebookforpurposivesamplinghasbecome commonplaceinsocialscienceresearch(RamoandProchaska 2012; VanSelmandJankowski 2006,435).

ThismethodisconsistentwithanumberofLGBTQIsurveys.TheEU AgencyforFundamentalRightsresearch(FRA, 2012)usedanonline surveyofself-reportedLGBTrespondentsacrosstheEuropeanUnion andCroatia.Theanonymousonlinequestionnairecollecteddatafrom 93,079personsaged18yearsoroverwhoself-identifiedaslesbian,gay, bisexual,ortransgenderregardingtheirviews,perceptions,opinions,and experiences.“Intotal,17,839visitorstotheEULGBTsurveywebsite camedirectlyfromtheFacebookdomain,and10,456usersessions resultingincompletedinterviewsarrivedfromFacebook(thatis,some visitorsdidnotproceedbeyondthefrontpageofthesurveytothe

questionnaire).Withthis,Facebookwasthesurvey’ssinglemostimportant referrer.”(FRA, 2012,42).Inaddition,Daneetal.(2016)surveyedtheIrish LGBTcommunityfollowingthe2015Thirty-FourthAmendmentofthe ConstitutionAct,whichestablishedmarriageequality.Inpart,the onlinesurveyalsousedQualtricsandFacebooktodistributethesurvey toself-identifiedmembersofthequeercommunity.Specificresearch intothetransgendercommunityhasalsobeenconducted.Jamesetal. (2016)administeredasurveyofthetransgendercommunityinthe UnitedStates.Theynotethedifficultyinconductingthistypeof research:“Thesurveywasproducedanddistributedinanonline-only formatafteradeterminationthatitwouldnotbefeasibletoofferitin paperformatduetothelengthandthecomplexityoftheskiplogic requiredtomovethroughthequestionnaire”(25).

Measures

Overall emotionaltaxationwasmeasuredwithfouritems:(a)“Doyou thinkitisemotionallytaxingorpersonallyintense(toacost)workingin theLGBTQImovement?”(yes,maybe,orno);(b)“Onascaleof0–10, howemotionallydifficultisitforyouworkingintheLGBTQI movement?”(0–10);(c)“Towhatextentwouldyouagreethatworking intheLGBTQImovementhasimpactedyourmentalhealth?”(1–7;

FIGURE 1.Targetrecruitment.

stronglyagreetostronglydisagree);(d)“Onascaleof0–10(10beingmost negative)howhasworkingintheLGBTQImovementaffectedyour mentalhealth?”Thelatterthreeitemswerescaledandcenteredfor comparability,thenwereusedtocreatethe emotionaltaxationscale. Althoughitisreliableatconventionallevels(Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.78),this studymarksitsfirstdeployment,andfurtherresearchshouldbe conductedtovalidateandoptimizethisscale.

Task-specific emotionaltaxationwasmeasuredwitha10-pointscale accompaniedbytheprompt,“Howemotionallytaxedareyouwhen doingthefollowingtasks?”Categoriesincludedmarchinginaparade, handingoutflyerstothepublic,lobbyinglegislators,tweeting(i.e., postingonTwitter),postingonFacebook,organizinganevent,leadinga protestaction,andself-expressionofidentitythroughclothes,ink,hair, andmakeup.Precedingthequestion,emotionaltaxationwasdefinedas “theemotionalcost,intentionalornot,thatapolicy,program,or schemeplacesonanindividualorgroupforenteringintothepolitical processoraddressingapoliticalissue.”

Issue-specific emotionaltaxationwasmeasuredwitha10-pointscale askingrespondentstorate“thewaydifferentissuesplaceemotional burdensonyoupersonally.”Thesecategoriesincludedmarriage equality,workplacediscrimination,openlyLGBTQImilitaryservice, youthhomelessness,LGBTQIseniorcare,andLGBTQImentalhealth.

Participants

Thesurveywascompletedby1,019LGBTQIactivistsintheUnitedStates (n ¼ 355),theUnitedKingdom(n ¼ 230),SouthAfrica(n ¼ 228),and Australia(n ¼ 206)betweenMay9andMay16,2017.Therespondents wereaskedarangeofdemographicquestionsincludingage,sexual orientation,andgenderidentity.Aquestiononracewasalsoincluded. AlthoughAustraliansurveyresearchgenerallyemploystheAustralian StandardClassificationofCulturalandEthnicGroups(Australian BureauofStatistics 2016),questionsonracearecommonplaceinthe UnitedStatesandSouthAfrica,wheremostrespondentsinthebroader studywerelocated.Thisquestionwasincludedforallrespondentsinthe interestsofcross-nationalcomparison.Questionsaboutactivistbehavior, suchastheirrole(s)andyearsofinvolvement,werealsoincluded. Table1 providesadetailedbreakdownofrespondentcharacteristics.

Race

White16583.32408620087.39260.8 Nonwhite3322.26222.23716.213840.5

Age

18–24years8341.98229.88840.26830.0 25–34years3216.24215.34118.76830.0 35–44years2713.63211.62310.53615.9 45–54years3115.74516.43516.03716.3 55–64years168.15018.2198.7156.6 65 + years94.5248.7135.931.3

Genderidentity Female1035210838.78738.09039.6 Male5929.812745.59441.010747.1 Queer199.6269.3229.6208.8 Genderqueer/nonbinary3316.75620.14419.22711.9

Sexualorientation

Heterosexual115.6248.6135.7177.5 Homosexual9447.414150.511751.114563.9 Bisexual3919.74215.13816.62812.3 Pansexual3216.23713.33716.2208.8 Other2211.13512.52410.5177.5 Transgender 3316.85820.83716.2167.1

Yearsinmovement

1–5years13063.416947.713759.813861.3 6–10years2512.26919.53013.14419.6 10 + years5024.411632.86227.14319.1

Role

Local18087.431488.620388.321594.3 State9345.118552.66026.13414.9 Federal6029.19827.82812.2104.4 International2914.14011.43414.82410.5

*Percentagesexcludenonresponse;race,role,gender,andlevelallowmultipleanswers.

Surveyrespondentswhoidentifiedasfemalemadeup52%ofthe respondentsinAustralia,38.7%intheUnitedStates,38%intheUnited Kingdom,and39.6%inSouthAfrica(Table1).Fewersurvey respondentsidentifiedasmaleinAustralia(29.8%oftherespondentsin

Australia),butmoreidentifiedasmalethanasfemaleintheUnitedStates (45.5%),theUnitedKingdom(41%),andSouthAfrica(47.1%). Respondentswhoidentifiedasqueeraccountedfor9.6%ofrespondents inAustralia,9.3%intheUnitedStates,9.6%intheUnitedKingdom, and8.8%inSouthAfrica.However,greaterpercentagesofrespondents identifiedasgenderqueer/nonbinaryinAustralia(16.7%),intheUnited States(20.1%),intheUnitedKingdom(19.2%),andinSouthAfrica (11.9%).

Ineachofthefourstudiedcountries,mostsurveyrespondentswereaged 18–34years:58.1%ofrespondentsinAustralia,45.1%intheUnitedStates, 58.9%intheUnitedKingdom,and60%inSouthAfrica.Survey participantswhoidentifiedastransgendercomprised16.8%ofthecohort inAustralia,20.8%intheUnitedStates,16.2%intheUnitedKingdom, butonly7.1%inSouthAfrica.Ineachofthefourcountries,mostofthe respondentsreportedtheirsexualorientationashomosexual:47.4%in Australia,50.5%intheUnitedStates,51.1%intheUnitedKingdom, and63.9%inSouthAfrica.Thenextmostcommonlyindicatedidentity wasbisexual,whichwasindicatedby19.7%ofrespondentsinAustralia, 15.1%intheUnitedStates,16.6%intheUnitedKingdom,and12.3% inSouthAfrica.Thethirdmostcommonlyindicatedidentitywas pansexual,whichwasindicatedby16.2%ofrespondentsinAustralia, 13.3%intheUnitedStates,16.2%intheUnitedKingdom,and8.8%in SouthAfrica.Surveyrespondentswhoidentifiedasheterosexual comprised5.6%oftherespondentsinAustralia,8.6%intheUnited States,5.7%intheUnitedKingdom,and7.5%inSouthAfrica.

RespondentswereaskedhowmanyyearstheyhadbeenintheLGBTQI movement.Themostfrequentresponsewas“1–5years”:63.4%of respondentsinAustralia,47.7%intheUnitedStates,59.8%inthe UnitedKingdom,and61.3%inSouthAfrica.Thosewhoresponded “6–10years”comprised12.2%oftherespondentsinAustralia,19.5%in theUnitedStates,13.1%intheUnitedKingdom,and19.6%inSouth Africa.Thosewhoresponded“10 þ years”comprised24.4%ofthe respondentsinAustralia,32.8%intheUnitedStates,27.1%inthe UnitedKingdom,and19.1%inSouthAfrica.

RESULTS

Consistentwithourexpectationsinformedbytheliterature,morethanfive timesasmanyrespondents(n ¼ 557)agreedthattheirinvolvementinthe

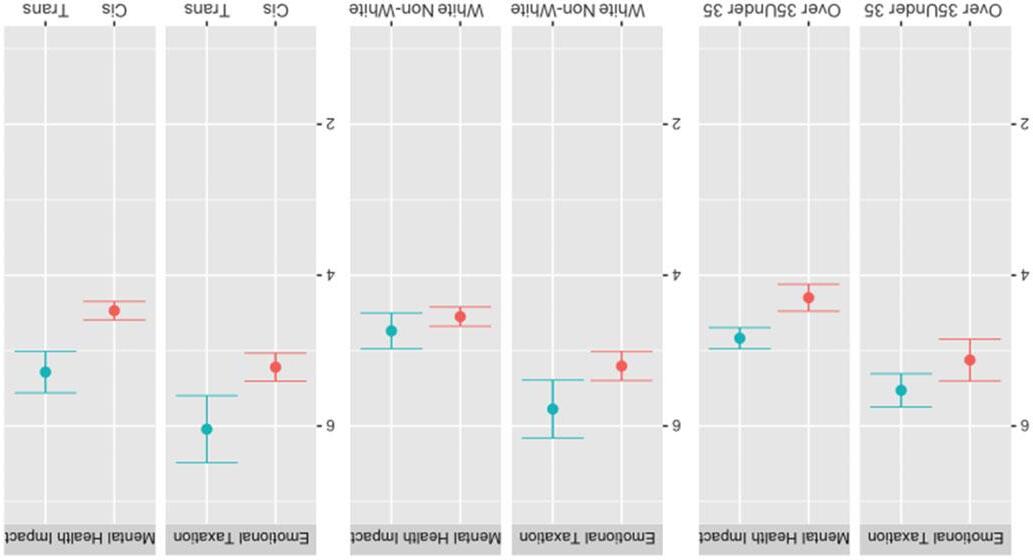

LGBTQImovementisemotionallytaxingthandisagreed(n ¼ 105). Amongtransgenderrespondents,theagree/disagreeratiowasmorethan eighttoone.Asshown Figure2,comparedtocisgenderactivists, transgenderactivistsexperiencedhigherlevelsofemotionaltaxation: F(899,1) ¼ 11.6( p , 0.01).Theyalsoreportedagreaterimpact upontheirmentalhealth: F(927,1) ¼ 27.1( p , 0.01).Similarly,nonwhite activistsreportedhigherlevelsofemotionaltaxationthanwhiteactivists: F(900,1) ¼ 8.0( p , 0.01).However,thislevelwasnotquitesignificantly higherwhenmentalhealthimpactswereconsidered: F(928,1) ¼ 2.0( p ¼ 0.15).Youngeractivists(lessthan35yearsold)alsoreportedsignificantly higherlevelsofemotionaltaxationthanolderactivists(morethan35years old): F(900,1) ¼ 5.3( p , 0.05).Youngeractivistsalsoreportedmuch greatermentalhealthimpacts: F(928,1) ¼ 22.0( p , 0.01).

Figure3 showstheemotionalburdenassociatedwitharangeof campaigntasksandissueareasbrokendownbycountryandage.The tasksincludedtweeting,postingonFacebook,attendingmarches, expressingidentity,postingflyers,organizingevents,lobbying,and participatinginaprotest.Consistentwith Figure2,thedatashowthat LGBTQIyoungeractivistsexperiencedemotionaltaxationatahigher ratethanolderactivistsineverycountryfornearlyallcampaigntasksand issues.OnlytheissueofseniorcareinAustralia,SouthAfrica,andthe UnitedStates,lobbyingintheUnitedKingdom,andtweetinginthe UnitedStatesimposedgreateremotionaltaxationonolderactivists. Amongrespondentsofallages,younger activistsreportedsignificantly higherlevelsofemotionaltaxationrelatedtothefollowingissues:LGBTQI militaryservice: F(434,1) ¼ 16.3( p , 0.01);same-sexmarriage: F(687,1) ¼ 13.1( p , 0.01);workplacediscrimination: F(753,1) ¼ 21.0 ( p , 0.01);youthhomelessness: F(666,1) ¼ 34.6( p , 0.01);andmental health: F(786,1) ¼ 71.4( p , 0.01).However,thehighlevelofemotional taxationdidnotextendtoseniorcare[F(609,1) ¼ 1.9( p ¼ 0.17)].Older respondentsreportedlessereffectsrelatedtoissues.Youngeractivistsalso reportedsignificantlyhigherlevelsofemotionaltaxationrelatedtothe followingtasks:eventorganization: F(808,1) ¼ 5.4( p , 0.05);personal expression: F(783,1) ¼ 14.8( p , 0.01);postingonFacebook: F(781,1) ¼ 8.2( p , 0.01);postingflyers: F(826,1) ¼ 6.7( p , 0.01);lobbying: F(805, 1) ¼ 5.1( p , 0.05);andprotesting: F(794,1) ¼ 8.1( p , 0.01). Interestingly,thehighlevelofemotionaltaxationdidnotextendtomarches [F(805,1) ¼ 3.7( p ¼ 0.56)]ortweeting[F(721,1) ¼ 2.7( p ¼ 0.1)].

Racealsoappearstoplayanimportantroleintheemotionalburdensof activists(Figure4).Converselytotheagedynamic,however,the

FIGURE 2.Age,race,andgenderidentity.

Abbreviations:Cis,cisgender;Trans,transgender.

*Errorbarsindicate95%confidenceintervals.

**Emotionaltaxation:“Onascaleof0–10,howemotionallydifficultisitforyouworkingintheLGBTQImovement?”

**Mentalhealthimpact:“Onascaleof0–10(10beingmostnegative)howhasworkingintheLGBTQImovementaffectedyour mentalhealth?”

FIGURE 3.Age.

Abbreviation:UK,UnitedKingdom.

*Pointrangesindicate95%confidenceintervals.

**Tasks:marchinginaparade;handingoutflyerstothepublic;lobbying legislators;tweeting(postingonTwitter);postingonFacebooking;organizing events;leadingaprotestaction;andexpressingidentitythroughclothes,ink, hair,andmakeup(1–10).

***Issues:marriageequality,workplacediscrimination,openlyLGBTQImilitary service,youthhomelessness,LGBTQIseniorcare,andLGBTQImentalhealth.

FIGURE 4.Racebycountry.

Abbreviation:UK,UnitedKingdom.

*Pointrangesindicate95%confidenceintervals.

**Tasks:marchinginaparade;handingoutflyerstothepublic;lobbying legislators;tweeting(postingonTwitter);postingonFacebook;organizingan event;leadingaprotestaction;andexpressingidentitythroughclothes,ink, hair,andmakeup(1–10).

***Issues:marriageequality,workplacediscrimination,openlyLGBTQImilitary service,youthhomelessness,LGBTQIseniorcare,andLGBTQImentalhealth.

differencesweresubstantiallygreaterwithregardtocampaigntasks comparedtoissues.Amongallrespondents,nonwhiteactivistsreported significantlyhigherlevelsofemotionaltaxationoneveryissue:LGBTQI militaryservice: F(434,1) ¼ 13.5( p , 0.01);same-sexmarriage: F(687, 1) ¼ 5.6( p , 0.05);workplacediscrimination: F(753,1) ¼ 6.5( p , 0.05);youthhomelessness: F(666,1) ¼ 12.4( p , 0.01);seniorcare: F(609,1) ¼ 4.2( p , 0.05);andmentalhealth: F(786,1) ¼ 7.3( p , 0.01).Althoughnonwhiteactivistsagainreportedsignificantlyhigher levelsofemotionaltaxationoneverytask-relateditem,largedifferences wereobservedamongtasks.Theemotionaleffectsrelatedtoseveraltasks weremodest:eventorganization F(808,1) ¼ 8.1( p , 0.01);lobbying: F(805,1) ¼ 5.8( p , 0.05);protests: F(794,1) ¼ 9.6( p , 0.01);and postingflyers: F(826,1) ¼ 14.6( p , 0.01).However,theseeffectswere moderatelylargeformarches[F(805,1) ¼ 22.0( p , 0.01)]andselfexpression[F(783,1) ¼ 29.3( p , 0.01)].Foronlineformsofactivism, emotionaltaxationeffectswereextremelylarge:postingonFacebook: F(781,1) ¼ 58.9( p , 0.01)andtweeting: F(721,1) ¼ 57.4( p , 0.01). Thedynamicsrelatedtothedifferencesbetweencisgenderand transgenderexperiencesofLGBTQIcampaignissuesandtasksaremore complex.Relativelylittlevariationwasobservedrelatedtoissues,but withregardtotasks,genderidentityinteractedprofoundlywithrace (Figure5).However,indirectcomparison,transgenderactivists experiencedsignificantlyhigherlevelsofemotionaltaxationfrom engagementinpublictasks1 thancisgenderactivists: F(665,1) ¼ 6.4( p , 0.05).Thedifferenceforonlinetasks(e.g.,postingonFacebookor tweeting)wasnotsignificant.Whenconsideredwithanintersectional perspectivebygender and race,nosignificantdifferencebetweenthe cisgender-whiteandtransgender-whitesubsamplesremained.However, takingaconservativeapproachandapplyingtheBonferroniposthoc correctionfortypeIerrorinflationresultingfrommultiplecomparisons, strongandsignificantdifferences( p , 0.01)remainedbetweenboththe cisgender-nonwhitesubgroupandbothwhitesubgroups,aswellas betweenthetransgender-nonwhitesubgroupandallthreeothersubgroups.

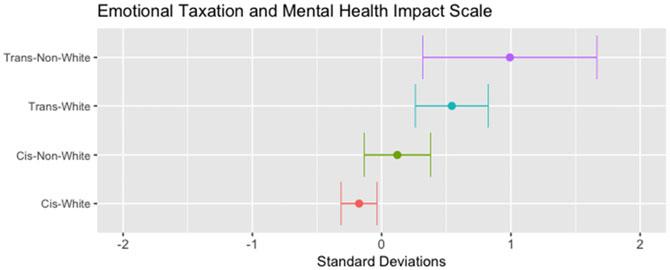

Theintersectionalanalysisofthescaleformedfromthecombined emotionaltaxationandmentalhealthmeasures(Figure5)showsthe expectedresult,withemotionaltaxationincreasingwithmarginalization. Thisresultconfirms Hypothesis1.Importantly,althoughthereisan

1.ScaleformedfromProtests,Marches,Personalexpression,andEventorganization:Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.71.

FIGURE 5.Intersectionalanalysisofissuesandtasks.

Abbreviations:Cis,cisgender;Trans,transgender.

*Pointrangesindicate95%confidenceintervals

**Tasks:marchinginaparade;handingoutflyerstothepublic;lobbying legislators;tweeting(postingonTwitter);postingonFacebook;organizing events;leadingaprotestaction;andexpressingidentitythroughclothes,ink, hair,andmakeup”(1–10).

***Issues:marriageequality;workplacediscrimination;openlyLGBTQImilitary service;youthhomelessness;LGBTQIseniorcare;andLGBTQImentalhealth.

approximately0.6standarddeviation(SD)penaltyassociatedwithbeing nonwhiteanda1SDpenaltyforbeingnoncisgender,thepenaltyfor beingnonwhite and noncisgenderis1.9SD,whichisapenaltygreater thanthesumofthecomponentpenalties.

DISCUSSION

Theresultsofthisstudyyieldprofounddataforourunderstandingofsocial movementorganizing,lobbying,andagendasetting.Ifsomeissuesand tasksaremorecostlytopersonallymobilizearound,thensomeactivists

areattractedwhileothersarepushedaway.Thus,emotionaltaxationmay actasafilterthatdeterminesnotonlywhoengagesbutalsowhatthey engagewith.Also,groupswithingroupsreportverydifferentexperiences ofactivism;thus,theactivistspacerequiresgreaterexamination.For instance,wearguethattheage,race,andgenderidentityofactivists couldbepowerfulmediatingfactorsontheselectionofissuesandtactics forasocialmovementbecausedisproportionateemotionalcostsare leviedonthesegroups.Thisisespeciallytrueattheintersectionsof theseidentities,whichrenderthemmorevulnerable(Crenshaw 1991; Pepin-NeffandCaporale 2018).Indeed,activistcampaignswiththebest ofintentionsdonotpresentanequalplayingfieldforall.Inturn,the directionofsocialmovementsandlobbyingcampaignsisinfluencedby thepeoplewhoshowuprepeatedly.Althoughtheremaybelittletono costforsome,othersreportaheavyemotionalburden.Thisinequity biasesboththemakeupofcommunitymobilizationsandwhichissues attracttheenergyneededtomobilizecollectiveaction.

Thisresearchisalsoimportantbecauseaccusationshavebeenlevelled thattheLGBTQImovementisoverwhelminglywhiteandbasedon overtandlatentracism.Thisstudywasnotdesignedtoidentifyracism; however,theliteraturemakesclearracismexistsintheLGBTQI movement.Ourdataprovideevidencefor Hypothesis2,thatthe makeupoftheLGBTQIactivistcommunityisproducedbyhierarchies ofmarginalizationinwhichinequitiesinemotionaltaxationcreate structuraldisincentivesforminorityparticipationinLGBTQIactivism. Thus,activismisnotthedemocraticinstitutioninwhichanyonecan choosetobattlethestatusquowhilefacingthesamepenaltiesand burdensasotheractivists.Instead,allmovementshavedifferentcostsfor participation,andcertainissuesandtacticsplaceacuteemotionalcostson certainpopulations.TheLGBTQIcommunityreflectsthesedifferences.

Asexpected,thedatademonstratethatLGBTQIactivistsintheUnited States,theUnitedKingdom,SouthAfrica,andAustraliaallexperience highlevelsofemotionaltaxation(Hypothesis1).Furthermore,the estimatesdetailedabovemaybeoverlyconservativeif,aswesuspect, extremelevelsofemotionaltaxationandstresscauseactiviststoburnout and/orleavethemovement.Wefindsystematicevidencethatmarginalized communitiesexperiencegreaterratesofemotionaltaxation.Furthermore, membersofmultiplemarginalizedcommunitiesexperienced disproportionatelyhigheremotionalcosts.Thesefindingsconfirm Hypothesis3.Althoughitisoftentreatedhomogeneously,theLGBTQI activistcommunityisreallyacommunityofsubcommunities,eachof 516

FIGURE 6.Emotionaltaxationscale.

Abbreviation:Cis,cisgender;Trans,transgender.

*Errorbarsindicate95%confidenceintervals.

**Scaleformedfromthreescaledandcentereditems(Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.78):(a) “Onascaleof0–10,howemotionallydifficultisitforyouworkinginthe LGBTQImovement?”;(b)“Onascaleof0–10(10beingmostnegative)how hasworkingintheLGBTQImovementaffectedyourmentalhealth?”;(c)“To whatextentwouldyouagreethatworkingintheLGBTQImovementhas impactedyourmentalhealth?”(1–7;stronglyagreetostronglydisagree).

whichfacesdifferentchallenges.Inaddition,subpopulationswithinthose subcommunitiesfacechallengesthatcompoundtheirburdens(Figure6). Ifmoremarginalizedgroupsfacehigherlevelsofemotionaltaxation, thenanavoidanceresponsemayresult,whichcouldmanifestina cisgender-whitewashedagenda-settingeffect.Ifthisprocessbiaseswhat movementsfocusonandwhofocusesonthem,themovementbecomes morecisgender-whitenotonlycompositionallybutalsointermsofits politicalagenda.Consequently,marginalizedgroupsandtheirpolitical interestsaremarginalizedbothoutsideandinsidetheLGBTQI movementthatrepresentsthem,creatingafeedbackloopinwhich LGBTQIactivismisbothmoredifficultformarginalizedactivistsand disproportionatelylessrepresentativeoftheirinterests.Importantly,the dataillustratethe kinds ofpoliticalactivitiesandissuesthatimpose greateremotionaltaxationonmoremarginalizedgroups.These underlyingdynamicsmayaffectthewaycampaignsarerunandthetypes ofissuesthatareselected.Indeed,activitiesthatattractcollectivesupport, suchasprotests,maystillrendertheparticipantsvulnerableto

persecution.Activistorganizersneedtorecognizethatnotallactivists experiencetheemotionalcostsofparticipationequally,andtheyshould takecaretoprotectmarginalizedactivistsfromdisproportionate emotionalstresstotheextentpossible.

Theevidencepresentedhereclearlydemonstratesthatactivistsworking againststructuresofoppressionarebynomeansimmunefrompayingan emotionalcostfortheirefforts.Indeed,thedegreetowhichtheyare affectedreflectsthedegreetowhichtheidentitiesthattheyinhabitare penalized.“Discriminationcanbecompoundedbymultiplestigmas,” includingrace(Bocktingetal. 2013,943).Asdemonstratedbythe resultspresentedin Figure5,treatingtransgenderandcisgenderactivists ashomogeneousgroupsmayobfuscateimportantintersectional dynamics.Thesedataaffirmthetheoryofintersectionality(Crenshaw 1991)andhighlightthefactthatpeoplewithmultiplemarginalized identitieshavedifferentexperiencesofLGBTQIactivismthanwhiteand cisgenderrespondents.

Figure5 revealsanumberofimportantdynamicswithinthedata.As hypothesized,marginalizedgroupswithintheLGBTQImovement consistentlydemonstratethehighestlevelsofemotionaltaxationand bearthegreatestmentalhealthcosts(Hypothesis1).Specifically, emotionalburdensweresystematicallygreaterforyoung,nonwhite,and transgenderactivists.Moreover,onlineactivismwasagreatdealmore stressfulfornonwhiteactiviststhanforwhiteactivists.Giventhewelldocumentedhostilitytowardracialandethnicminoritiesonsocial media,thisisnotaltogethersurprising;however,themagnitudeis remarkable—morethanhalfastandarddeviationforbothtweetingand postingonFacebook.Thisfindingsuggeststhatasthedigitalrevolution continues,attentionshouldbegiventotheemotionalimpacton marginalizedcommunities,whosemembersmayexperienceemotional impactsassevereasthoserelatedtoother,better-establishedformsof activistengagement(see,e.g.,Constanza-Chock 2010;Jenzen 2015; Krutzsch, 2014;LievrouwandLivingstone 2010).

Furthermore,sourcesofemotionaltaxationvarygreatlyamongactivists. Transgenderactivistswereparticularlystressedbypublicengagementssuch asmajoreventsandmarches.Althoughtransgenderrespondentsappeared toexperiencenogreaterburdenfromprivateactivism(i.e.,postingflyers andlobbying)andonline(i.e.,tweetingandpostingonFacebook) activism,theemotionalburdenofpublicactivism(i.e.,self-expression, marches,protest,andevents)wassignificantlygreaterfortransgender activiststhanforcisgenderactivists: F(665,1) ¼ 6.4( p , 0.05).This 518

findingagreeswiththeminoritystressmodel:“Thestressassociatedwith stigma,prejudice,anddiscriminationwillincreaseratesofpsychological distressinthetransgenderpopulation”throughprocessesthatareboth “external—consistingofactualexperiencesofrejectionand discrimination(enactedstigma)”and“internal,suchasperceived rejectionandexpectationsofbeingstereotypedordiscriminatedagainst (feltstigma)”(Bocktingetal. 2013,943).Hence,publicactivism involvescomplexinternalandexternalprocessesassociatedwith“hiding minoritystatusandidentityforfearofharm(concealment)”(Bockting etal. 2013,943),whichmanifestsinidentitysuppressionand/or emotionalstress.

Thissituationiscompoundedwhenweconsidertheinfightingand erasurethatcanexistwithintheLGBTQImovement(Ghaziani 2008). Murib(2017)notesthat“Inmanycases,theprivilegingofsexual orientation(i.e.,lesbianandgaypoliticalidentitiesandpolitical interests)entailedsilencingthepoliticalagendasfortransgenderand bisexual-identifiedpeople,aswellasbutches,fairies,crossdressers,queer peopleofcolor,andintersex-identifiedpeople,whoalsocompromised themarginsofthenew‘GLBT’identity”(20–21).Asaresult,difficult externalsituationsaremademoreperilousinternallyasthebroader marginalizedLGBTQIcommunitytakesactionsthatfurthermarginalize lesspowerfulmemberswithinthatgroup.Thisphenomenonwas empiricallyvalidatedbyourdata.Weaskedrespondentstoindicatethe mostsignificantobstaclestoLGBTQIprogress:“Whatwouldyousayare thebiggestobstaclestowinningLGBTQIequality?”Respondentsfrom everycountrynominatedallies(i.e.,equalitygroupsandnon-LGBTQI progressivegroups)overenemies(i.e.,anti-LGBTQIreligiousgroupsand opponents)ataratesof62%versus38%,respectively.

Finally,someimportantdifferencesbetweenthecountrieswererevealed. Forinstance,fewrespondentsinSouthAfricaidentifiedastransgender(7%). Thisfindingmayhaveresultedfromcontinuingviolence(asnoted),butitwas incongruentwithrespondentsfromAustralia(16.8%),theUnitedStates (20.8%),andtheUnitedKingdom(16.2%).Inaddition,respondentsin Australia(inMay2017)feltmoreemotionaltaxationrelatedtotheissueof same-sexmarriagethanrespondentsintheotherthreecountriesthat alreadyhadit.Thesamewastruefortheissueofgaymilitaryservice: respondentsreportedlessemotionaltaxationineachcountrythathad alreadyenactedlegislationonthatissue.IntheUnitedKingdomandthe UnitedStates,theagegapregardingconcernaboutyouthhomelessness waslarge,butperhapsmoresurprisingly,itwasalsolargewithregardto

overallmentalhealth(Figure3).Althoughthesewerethetwomostsignificant campaignissuesintermsofemotionalburdenreported,thiseffectwasalmost entirelydrivenbyyoungeractivists,whowerealsosignificantlymoredistressed byconcernsaboutworkplacediscrimination.

Overall,thedistributionofemotionalbenefitsandburdensisacore conceptinsocialmovementmobilization,ininterest-groupissue selection,inthemakeupofcoalitions,andintheactivitiesandactions executed.Italsofurtheridentifiesthemarginalizationofoppressedgroups likethetransgendercommunity.Trackingthesedistributionsshouldbea standardpartofsocialscienceresearch.Althoughitisnotremarkablethat ourdataareconsistentwiththetheoryofintersectionality,thisisthefirst timethispresumptionhasbeenconfirmedwithinLGBTQIactivism usingquantitativesurveydataacrossfourcountries.Indeed,working withinthemovementmaysubjectindividualstomoreemotionaltaxation thanatanyotherpoint,andgroupswithingroupsmayexperiencea compoundemotionalburden.Thesedataprovidenewevidenceto confirmthetheoryofnegativeexposure,andouranalysisbuildsonthis theoryusingtheconceptofemotionaltaxation.Thisstudymaybeuseful infurtherresearchonsocialmovementmobilizationordemobilization, issueselectionwithinmovements,andcommunityresilience.

CONCLUSION

ThisstudyfurtherdemonstratesthatLGBTQIpridecomesatacost.The datawereportfrom1,019LGBTQIactivistsadvancesthiseffortand connectsemotionaltaxationtoagendasetting,socialmovement organizing,lobbying,andpoliticalinstruments.

Moreresearchinthisarea,throughthedeploymentofexperimental surveymethodsandcomparisonsacrossvaryingemotionalpolitical issues,isneeded.Understandingtheburdens,punishments,negative mentalhealtheffects,andemotionalcostsfacedbytargetpopulations basedonhowtheyparticipateinthepoliticalprocessisfundamentalto politicalanalysis.Greaterunderstandingofthedynamicsofemotional taxationmayhelpensurethatthepoliticalprocessincludesnotonly thosewhofacefewpenaltiesforthemostwide-rangingpolitical endeavorsbutalsothosewhoaremarginalizedbecauseoftheirgender orsexualidentity.Politicsisateamsport,butnotallteamsarecreated equal.Thisanalysishashighlightedtheemotionaladvantagesthatsome receivesimplybyvirtueoftheiridentity.Moreover,thesedatasuggest

thattheindividualL-G-B-T-Q-Imembersofthecollectivecommunityare notallimpactedthesamewaybyequalitycampaigns.Themoreadverse marginalizationagroupfaces,themoreemotionaltaxationthey experiencewhentheyenterthepoliticalprocess,whichhassignificant ramificationsfortheirpoliticalengagementandefficacy.Levelingthe politicalplayingfieldintheUnitedStates,theUnitedKingdom,South Africa,Australia,andelsewhereintheworldwilltakemoretime,but identifyingtheexistinginequalitiesinthewaypoliticsisplayedneednot.

REFERENCES

Adam,Barry.1995. TheRiseofaGayandLesbianMovement.NewYork:Twayne. Armstrong,Elizabeth.2002. ForgingGayIdentities:OrganizingSexualityinSanFrancisco, 1950–1994.Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress. AustralianBureauofStatistics.2016.1249.0–AustralianStandardClassificationof CulturalandEthnicGroups(ASCCEG),2016. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/absnsf/ mf/1249.0.AccessedFebruary26,2019.

BallCarlos.,editor.2016. AfterMarriageEquality:TheFutureofLGBTRights.NewYork: NewYorkUniversityPress.

Barker,Meg.,ChristinaRichards,RebeccaJones,andSuryaMonro.2011.“BiReCon:An InternationalAcademicConferenceonBisexualityIncludingtheProgramfor BiReCon.” JournalofBisexuality 11(2–3):157–170.

Baumgartner,Frank,andBrianJones.1993. AgendasandInstabilityinAmericanPolitics. Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress.

Baylis,Troy-Anthony.2015. “Introduction:LookingIntotheMirror.”InColouringthe Rainbow:Blak,Queer,andTransPerspectives,ed.DinoHodge.Adelaide,South Australia:WakefieldPress

Berman,Alan.2008.“TheExperiencesofDenyingConstitutionalProtectiontoSodomy LawsintheUnitedStates,AustraliaandMalaysia:You’veComeaLongWayBaby andYouStillHaveaLongWaytoGo.”OxfordUniversityComparativeLawForum. Bockting,Walter.,MichaelMiner,RebeccaSwinburneRomine,AutumnHamilton,and EliColeman.2013.“Stigma,MentalHealth,andResilienceinanOnlineSampleofthe USTransgenderPopulation.” AmericanJournalofPublicHealth 103(5):943–951.

Bourdieu,Pierre.1977. OutlineofaTheoryofPractice,vol.16.Cambridge,UK:Cambridge UniversityPress.

Chen,CherWeixia,andPaulGorski.2015.“BurnoutinSocialJusticeandHumanRights Activists:Symptoms,CausesandImplications.” JournalofHumanRightsPractice 7(3): 366–390.

Cock,Jacklyn.2003.“EngenderingGayandLesbianRights:TheEqualityClauseinthe SouthAfricanConstitution.” Women’sStudiesInternationalForum 26(1):35–45. Costanza-Chock,Sasha.2010. Seve,sesiente:TransmediamobilizationintheLosAngeles immigrantrightsmovement.Dissertation,UniversityofSouthernCalifornia. Crenshaw,Kimberle.1991.“MappingtheMargins:Intersectionality,IdentityPolitics,and ViolenceagainstWomenofColor.” StanfordLawReview 43(6):1241–1299. Currier,Ashley.2010.“TheStrategyofNormalizationintheSouthAfricanLGBT Movement.” Mobilization:AnInternationalQuarterly 15(1):45–62. —.2012. OutinAfrica:LGBTOrganizinginNamibiaandSouthAfrica.Minneapolis: MinnesotaUniversityPress.

Dane,Sharon.,ElizabethShort,andGrainneHealy.2016.“SwimmingwithSharks:The NegativeSocialandPsychologicalImpactsofIreland’sMarriageEqualityReferendum ‘NO’Campaign.”SchoolofPsychologyPublications.TheUniversityofQueensland, Australia. http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:408120 AccessedFebruary25,2019.

Davidson,Roger.,andGayleDavis.2004.“‘AFieldforPrivateMembers’:TheWolfenden CommitteeandScottishHomosexualLawReform,1950–67.” TwentiethCentury BritishHistory 15(2):174–201.

Eekelaar,John.2014.“PerceptionsofEquality:TheRoadtoSame-SexMarriagein EnglandandWales.”InternationalJournalofLaw, PolicyandtheFamily 28(1):1–25. EuropeanUnionAgencyforFundamentalRights,FRA.2012.“EULGBTSurveyEuropeanUnionlesbian,gay,bisexualandtransgendersurvey-Resultsataglance: SurveymethodologyQandA.” https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2013/eu-lgbtsurveyeuropean-union-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-survey-results/surveymethodologyq-and-a.AccessedonFebruary26,2019.

Eysenbach,Gunter.2004.“ImprovingtheQualityofWebSurveys:TheChecklistfor ReportingResultsofInternetE-Surveys(CHERRIES).” JournalofMedicalInternet Research 6(3):e34.

Faderman,Lillian.2015. TheGayRevolution:TheStoryoftheStruggle.NewYork:Simon andSchuster.

Fricker,Ronald.2008.“SamplingMethodsforWebandE-mailSurveys.”In TheSage HandbookofOnlineResearchMethods,eds.N.Fielding,R.Lee,andG.Blank, 195–216.ThousandOaks,CA:Sage.

Ghaziani,Amin.2008. TheDividendsofDissent:HowConflictandCultureWorkin LesbianandGayMarchesonWashington.Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress. Gorski,Paul.2018.“FightingRacism,BattlingBurnout:CausesofActivistBurnoutinUS RacialJusticeActivists.” EthnicandRacialStudies 42(5):667–687

Gould,Deborah.2009. MovingPolitics:EmotionandACTUP’sFightagainstAIDS Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress.

Haider-Markel,Donald,andJamiTaylor.2016.“TwoStepsForward,OneStepBack:The SlowForwardDanceofLGBTRightsinAmerica.”In AfterMarriageEquality:The FutureofLGBTRights,ed.CarlosBall,42–72.NewYork:NewYorkUniversityPress. Helfer,Lawrence.,andErikVoeten.2014.“InternationalCourtsasAgentsofLegal Change:EvidencefromLGBTRightsinEurope.” InternationalOrganization 68(1):77 Herman,Jody.2013.“GenderedRestroomsandMinorityStress:ThePublicRegulationof GenderanditsImpactonTransgenderPeople’sLives.” JournalofPublicManagement &SocialPolicy (Newark)19(1):65–80. HillCollins,Patricia.,andBilgeSirma.2016.“WhatisIntersectionality?”In Intersectionality, eds.PatriciaHillCollinsandSirmaBilge,1–30.Malden,MA:PolityPress. Hochschild,Arlie.1983. TheManagedHeart.BerkeleyandLosAngeles:Universityof CaliforniaPress. Hopkins,June.1969.“TheLesbianPersonality.” BritishJournalofPsychiatry 115:1433–1436.

James,Sandy.,JodyHerman.,SusanRankin.,MaraKeisling.,LisaMottet.,and Ma’ayanAnafi.2016.“TheReportofthe2015U.S.TransgenderSurvey.National CenterforTransgenderEquality.” https://issuu.com/lgbtagingcenter/docs/usts-fullreport-final.AccessedFebruary27,2019. Jenzen,Olu.2015.LGBTQDigitalActivism,SubjectivityandNeoliberalism.Presentedat theCentreforResearchinMemory,NarrativeandHistoriesResearchSeminarSeries, UniversityofBrighton,inBrighton,UK,onFebruary18,2015.

KentCountyCouncil.2011.Lesbian,Gay,BisexualandTransgenderSupportToolkit. Availablefrom: https://www.kent.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/18068/LesbianGay-Bisexual-and-Transgender-support-toolkit.pdf.AccessedFebruary27,2019.

Kepner,Jim.,andStephenMurray.2002.“HenryGerber(1895–1972):Grandfatherof theAmericanGayMovement.”In BeforeStonewall:ActivistsforGayand LesbianRightsinHistoricalContext,ed.V.Bullough,24–34.NewYork:Harrington ParkPress.

Kingdon,John.1984. Agendas,AlternativesandPublicPolicies.NewYork:HarperCollins. Krutzsch,Brett2014.“ItgetsBetterasaTele ologicalProphecy:AUniversalPromise ofProgressthroughAssimilation.” TheJournalofPopularCulture 47(6): 1245–1255.

Lang,A.2000.“TheLimitedCapacityModelofMediatedMessageProcessing.” Journalof Communication 50(1):46–70.

Lievrouw,Leah.,andSoniaLivingstone.2010.“IntroductiontotheFirstEdition(2002): TheSocialShapingandConsequencesofICTs.”In HandbookofNewMedia:Social ShapingandSocialConsequencesofICTS,eds.L.LievrouwandS.Livingstone,15–32.London:Sage.

Marcus,George.2000.“EmotionsinPolitics.” AnnualReviewofPoliticalScience 3(1): 221–250.

Maslach,Christina.,andMaryGomes.2006.“OvercomingBurnout.”In Workingfor Peace:AhandbookofPracticalPsychologyandOtherTools,ed.R.McNair. Atascadero,CA:Impact.

McAllister,Ian.,andFeodorSnagovsky.2018.“ExplainingVotinginthe2017Australian Same-SexMarriagePlebiscite.” AustralianJournalofPoliticalScience 53(4):409–427.

Meyer,Ilan.1995.“MinorityStressandMentalHealthinGayMen.” JournalofHealthand SocialBehavior 36:38–56.

—.2003.“Prejudice,SocialStress,andMentalHealthinLesbian,Gay,andBisexual Populations:ConceptualIssuesandResearchEvidence.” PsychologicalBulletin 129(5):674–697.

Meyer,Ilan.,andPatrickWilson.2009.“SamplingLesbian,Gay,andBisexual Populations.” JournalofCounselingPsychology 56(1):23.

Mintrom,Michael.2000. PolicyEntrepreneursandSchoolChoice.Washington,DC: GeorgetownUniversityPress.

Moore,Clive.1995.“PoofsinthePark:DocumentingGay‘Beats’inQueensland, Australia.” GLQ 2:319–339.

Murib,Zein.2017.“RethinkingGLBTasaPoliticalCategoryinUSPolitics.” LGBTQ Politics:ACriticalReader 14–33.

Neff,Christopher.2016.“EmotionalTaxation.”Lecture.RetrievedfromUniversityof SydneyGOVT6159Emotions,AgendasandPublicPolicyBlackboardsite.

Neff,Christopher.,andLukeEdgellBlas.2013.“TheRiseofRepeal:Policy EntrepreneurshipandDon’tAsk,Don’tTell.” JournalofHomosexuality 60(2–3): 232–249.

OtherFoundation,The.2016.“ProgressivePrudes:ASurveyofAttitudesTowards Homosexuality&GenderNon-conformityinSouthAfrica.” http://theotherfoundation. org/wp-content/uploads/2016/ 09/ProgPrudes_Report_d5.pdf .AccessedFebruary 26,2019.

Pepin-Neff,Christopher.,andKristinCaporale.2018.“FunnyEvidence:FemaleComics aretheNewPolicyEntrepreneurs.” AustralianJournalofPublicAdministration 77(4): 554–567.

Pines,Ayala.1994.“ThePalestinianIntifadaandIsraelis’Burnout.” JournalofCrossCulturalPsychology 25(4):438–451.

Ramo,Danielle.,andJ.J.Prochaska.2012.“BroadReachandTargetedRecruitmentUsing FacebookforanOnlineSurveyofYoungAdultSubstanceUse.” JournalofMedical InternetResearch 14(1):e28.

Rimmerman,Craig.1996. Gayrights,militarywrongs:Politicalperspectivesonlesbiansand gaysinthemilitary.NewYork:Routledge.

Sabatier,Paul.,andNeilPelkey.1987.“IncorporatingMultipleActorsandGuidance InstrumentsintoModelsofRegulatoryPolicymaking:AnAdvocacyCoalition Framework.” Administration&Society 19(2):236–263.

Schneider,Anne.,andHelenIngram.1993.“SocialConstructionofTargetPopulations: ImplicationsforPoliticsandPolicy.” AmericanPoliticalScienceReview 87(2):334–347.

Sabatier,PaulA.,andHankJenkins-Smith.1988“Specialissue:policychangeandpolicyorientedlearning:exploringanadvocacycoalitionframework.” PolicySciences 21(2): 123–277.

Srivastava,Sarita.2006.“Tears,FearsandCareers:Anti-racismandEmotioninSocial MovementOrganizations.” CanadianJournalofSociology/Cahierscanadiensde sociologie 31(1):55–90.

True,James,BrianJones.,andFrankBaumgartner.2007.“Punctuated-Equilibrium Theory:ExplainingStabilityandChangeinPublicPolicymaking.”In Theoriesofthe PolicyProcess,ed.P.A.Sabatier,P.A.Boulder,CO:WestviewPress.

VanSelm,Martine.,andNicholasJankowski.2006.“ConductingOnlineSurveys.” Quality &Quantity 40(3):435–456.

Zahariadis,Nicholas.2007.“TheMultipleStreamsFramework:Structure,Limitations, Prospects.”In TheoriesofthePolicyProcess,ed.P.A.Sabatier.Boulder,CO: WestviewPress.