BriefReport

BriefReport

ChristopherL.Pepin-Neff

Citation: Pepin-Neff,C.L.SharkBite ReportingandTheNewYorkTimes. Biology 2022, 11,1438. https:// doi.org/10.3390/biology11101438

AcademicEditor:DarylMcPhee

Received:29August2022

Accepted:29September2022

Published:30September2022

Publisher’sNote: MDPIstaysneutral withregardtojurisdictionalclaimsin publishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

Copyright: ©2022bytheauthor. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

SchoolofSocialandPoliticalSciences,DisciplineofGovernmentandInternationalRelations, UniversityofSydney,Camperdown,NSW2006,Australia;chris.pepin-neff@sydney.edu.au

SimpleSummary: ThisbriefreportlooksatthelanguageusedbyTheNewYorkTimestoreporton human-sharkinteractionsandwhethertheygobeyondthephrase“sharkattack”.“Sharkattack” isaphrasethatholdsapowerfulpsychologicalpositioninthemindofthepublicanddirectsthe waysharksaretalkedaboutinsociety.However,itraisesconcernsbecausethephrase“sharkattack” tellsaone-dimensionalstoryofsharkbehavior,whichisoftenmisleading.Datashowsthatbetween 32–38%ofreportedshark“attacks”havenoinjuryatall.Asaresult,scrutinyofmediareportingon differenttypesofhuman-sharkinteractionsisimportant.ThisstudyfoundTheNewYorkTimes stillusesshark“attack”languagebuthasbeguntolayeritwithmorescientificallyaccurateshark “bite”and“sighting”narrativesthatconveylesssensationalstories.Thisispartofagrowingtrendto incorporateabroaderlexiconthatexplainsthatnoteveryinteractionwithsharks’resultsininjury orfatality.

Abstract: Thesocialandpoliticaldynamicsaroundhuman–sharkinteractionsareagrowingareaof interestinmarinesocialscience.ThequestionmotivatingthisarticleaskstowhatextentmediareportingbyTheNewYorkTimeshasengagedbeyondthelexiconof“sharkattack”discoursetodescribe human–sharkinteractions.Itisimportantbecausedifferentstylesofreportingonhuman–shark interactionscaninfluencethepublic’sperceptionsaboutsharksandsupportforsharkconservation. Thismediaoutletisalsoapaperofrecordwhoseeditorialstylechoicesmayinfluencethebroader medialandscape.IreviewreportinglanguagefromTheNewYorkTimesfor10yearsbetween2012 and2021(n=36).Ipresentthreefindings:first,IarguethatTheNewYorkTimeshashadanincreased frequencyinuseoftheterm“sharkbite”todescribehuman–sharkinteractions.Secondly,Ifindthat shark“attack”isstillusedconsistentlywithothernarratives.Third,thereappearstobeanincreased useof“sightings;encounter;andincident”descriptorssince2020.Theimplicationofthisisalayered approachtoreportingonhuman–sharkinteractionsthatdiversifiesawayfromaone-dimensional shark“attack”discourse.

Keywords: sharkbite;sharkincident;sharkattack;mediaanalysis;NewYorkTimes

1.Introduction

On17September1865,TheNewYorkTimesreportedontheirfirsthuman–shark interaction[1].PeterJohnsonwasaboardtheschooner CatherineWilcox outofLubec,Maine whenhejumpedintothewatertoretrieveapieceofwood.Whileinthewater,hewas “seizedaboutthemiddle”byafourteen-footshark.TheNewYorkTimesnotes,“thecase attractsattentionbecauseofthefactthatthesharkmusthavebeenofthespeciesknownas “maneater”whicharecommoninthelowlatitudesbutarerarelyseenintheshoalwater. Thecommonshovel-nosesharkofourwaterseldomifeverattackmankind”.

Thefocusofthisstudycentersontheuseofphrase“sharkattack”andhowthis terminologycaninfluencepublicperceptions.“Sharkattack”representsoneofthemost emotivetwo-wordphrasesintheEnglishvocabulary.Thislanguageutilizesaveryspecific wordingtodescribehuman–sharkinteractionsinwaysthathaveaprofoundimpacton thepublic’srelationshipwithsharks[2].Studieshaveshownthatwhenpeoplebelieve

inintent-basednarratives,suchasshark“attack”,theyarelesslikelytosupportshark conservationpolicies.Mediareportingonhuman–sharkinteractionsoftenincludesthe phrase“sharkattack”,whichsuggestsaveryseriousorfataloutcome.Pepin-Neffand Wynterstate,“fearofsharkscorrelateswithsupportforlethalpolicies,thisassociation ispowerfullymediatedbyperceptionsofintentionality”[3],page1.Inaddition,“shark attack”discoursehasapowerfulinfluenceonfeartowardsharksbytellingastoryabouta creaturethatintentionallyeatshumans,ratherthanafishwhichaccidentallyormistakenly bitespeopleonexceptionallyrareoccasions.Moreover,Ostrovkietal.(2021)addtothis analysisbynotingtheimportanceofageindeterminingfearofsharksbasedonpeoples’ exposuretodifferencemediasources[4].

Thishistoricalinterplayrelativetoemotions,words,andactualhuman–sharkinteractionsmotivatestheresearchquestion.Theresearchquestionaskstowhatextent mediareportingbyTheNewYorkTimesengagesbeyondthelexiconof“sharkattack” discoursetodescribehuman–sharkinteractions.Theaimofthisstudyistoexaminereportingstylesoveradecadeanddetermineifthereareanyvariationsfromthe“shark attack”monopoly.TheNewYorkTimesprovidesusefulexaminationsforseveralreasons. First,itwasfoundedin1851soitprovidesadegreeofmediacontinuity.Second,todayit has9millionsubscribers[5].Thisreadershipreinforcesitspositionasapaperofrecord. Inaddition,TheNewYorkTimeshasaslowhistoryoftextualvariation.TheNewYork TimesManualofStyleandUsagehasbeenupdatedjustfourtimessince1950.Asaresult, perceivedadjustmentsandchangestohuman–sharkinteractionreportingaresignificantin thecontextofthemedialandscape.

ThethesisofthisstudyisthatTheNewYorkTimeshasdiversifiedaroundhuman–sharkinteractionnarrativelanguage.Indeed,Ipresentthreepreliminaryfindings:first,I arguethatTheNewYorkTimeshashadanincreasedfrequencyinuseoftheterm“shark bite”todescribehuman–sharkinteractions.Secondly,Ifindthatshark“attack”isstillused consistentlywithothernarratives.Third,thereappearstobeanincreaseduseof“sightings; encounter;andincident”descriptorssince2020.Theimplicationsofthesefactorscontribute tomultiplenarrativesaroundhuman–sharkinteractionsratherthanaone-dimensional shark“attack”discourse.

Thisstudyisimportantbecausedifferentstylesofreportingonhuman–sharkinteractionscaninfluencethepublic’sperceptionsaboutsharksandsupportforsharkconservation. Thisvocabularyisdeployedasamediaassettostrategicallytapintothereader’ssubconsciousandmotivatethemtoreadorclickonanewslink.Inalandmarkstudyonthe mediaandsharksMuteretal.(2012)foundthat“Sharkattackswerereportedatleast 5timesmorethanconservationconcernsoranyothershark-relatedtopic”[6].Thisangle iscommonlypushedbyeditorsatnewspapersandlargemediaoutletsinwaysthatgive certainmeaning(i.e.,intentionality,fataloutcomes)whichhavesurvivalvalueasclickbait toeventsinvolvingsharks.Moreover,theremaybefinancialincentivestogainmoreclicks onhighlysensationalizedheadlines.Thiscanhaveimplicationsforsharkconservation becausestokingfearsofsharksthroughthemediaiseasytodo.AstudybyCrossleyfound, “thegeneralpublicgrosslyoverestimatesthenumberofnon-fatalandfatalsharkattacks, doublingthenumberofnon-fatalandquadruplingthenumberoffatalsharkattacks”[7]. Therefore,anexaminationofaleadingmediaoutletmayprovideasnapshotintofuture trendsregardingcoverageandforeshadowpublicperceptionsofsharks.

Thisstudyaddressesseveralunderlyingtensions.First,thedebateovertheproper terminologytousewhenreportingoneventsinvolvingsharksisdifficultbecausethere arerealtragediesforindividualsthatoccurandemotionallydifficultperiodsforcommunities[2].Severalfatalincidentshaveoccurredoverthepastdecade,namelyinRecife Brazil,CapeCod,ReunionIsland,andWesternAustraliawhere“attack”isappropriate becausethemotivationofthesharkappearsscientificallydeterminant[8–11].Additionally, whilethisrepresentsafractionofevents,ithasbothsocialandscientificpurchasethatis importanttorecognize.

Secondly,anynewlabelsthatpushbackagainsttheculturalmonopolyof“shark attack”discoursemaybeseentobemakinglightorwateringdownhumantragedies.For instance,followingahighlypublicizedarticleintheGuardianandTheNewYorkTimes, comedianStephenColberthadashortsegmentonhisshow,“TheLateShow”inJuly 2021regardingattemptstorelabelhuman–sharkinteractions,stating:“Inordertochange publicperceptionofsharks,Australianscientistsareseekingtorebrandsharkattacksas interactionsorincidents.Asin,I’msorryma’am,asharkinteractedwithyourhusband’s torsoandhe’sexperiencinganotbeingaliveincident”[12].

Inaddition,FoxhostTuckerCarlson[13]alsoranasegmentregardingthisstoryunder thepicture,“TodayinLiberalLunacy”,stating:“Inanothersignofglobalprogress,some governmentagenciesinonecountryarenolongerusingthetermsharkattacks.Theysaidit isastigmatizingphrasethatunfairlyprejudicespeopleagainstthese subsurfacecarnivores”.

Thirdly,therearedifferentstylesofreportingonhuman–sharkinteractionsthatcan influencethepublic’sperceptionsaboutsharksandsupportforsharkconservation.Scientificpushbackagainstthe“sharkattack”mediareportingbeganinearnestin1916inthe UnitedStatesandinthe1920’sinAustralia,whereshark“accident”wasmorecommonly usedbylocalgovernments[14].In1933,AustraliansurgeonVictorCopplesonwroteabout “sharkattacks”intheAustralianMedicalJournal,andthisseemedtoturnthetideonits morewidespreadadoptionanduse[15].In1958,atypologyofsharkattackcategories wasintroducedfollowingaNewOrleansSharkSymposium.Theystated[16],“Inthe tabulationthatfollows,wesetupcertaincategoriesforthevariouskindsofsharkattacks: UnprovokedSharkAttacks,ProvokedAttacks,BoatAttacksandAirandSeaDisasters”. TheSymposium’sworkhastransitionedtomodernresearchanalysisbytheInternational SharkAttackFile,whichusestwomaincategories:‘“Unprovokedbites”whicharedefined asincidentsinwhichabiteonalivehumanoccursintheshark’snaturalhabitatwithno humanprovocationoftheshark.’Additionally,‘“Provokedbites”whichoccurwhena humaninitiatesinteractionwithasharkinsomeway”[17].

Fourthlyapost-Jaws dimensiontoshark“attack”discoursebeganinthe2000’s.In 2000,duringthe“SummeroftheShark”inFloridatherewasanewpushbackbyshark scientistssuchasRobertHueter,andmoreofficiallyin2012and2013.WashingtonPost journalistJulietEilperin,inherbookDemonFish[18],notablyreferstohuman–shark interactionsasshark“strikes”.Additionally,in2013,NeffandHueterproposednew categoriesforhuman–sharkinteractionsbecausetheyfoundthatina2009NewSouth Wales,Australiagovernmentreport,approximately38%ofreported“sharkattacks”had noinjury[19].

The2013proposedcategoriesbyNeffandHueter[15]include: Sharksightings:Sightingsofsharksinthewaterinproximitytopeople.Nophysical human–sharkcontacttakesplace.

Sharkencounters:Human–sharkinteractionsinwhichphysicalcontactoccursbetweenasharkandaperson,oraninanimateobjectholdingthatperson,andnoinjurytakes place.Forexample,sharkbitesonsurfboards,kayaks,andboatswouldbeclassifiedunder thislabel.Insomecases,thismightincludeclosecalls;asharkphysically“bumping”a swimmerwithoutbitingwouldbelabeledasharkencounter,notasharkattack.Thisisthe categorymostcloselyalignedtowhathappenedtosurferMickFanningin2015[20].

Sharkbites:Incidentswheresharksbitepeopleresultinginminortomoderateinjuries. Smallorlargesharksmightbeinvolved,buttypically,asingle,nonfatalbiteoccurs.Ifmore thanonebiteoccurs,injuriesmightbeserious.Underthiscategory,theterm“sharkattack” shouldneverbeusedunlessthemotivationandintentoftheanimal—suchaspredationor defense—areclearlyestablishedbyqualifiedexperts.Sincethatisrarelythecase,these incidentsshouldbetreatedascasesofshark“bites”ratherthanshark“attacks”.

Fatalsharkbites:Human–sharkconflictsinwhichseriousinjuriestakeplaceasaresult ofoneormorebitesonaperson,causingasignificantlossofbloodand/orbodytissueand afataloutcome.Again,westronglycautionagainstusingtheterm“sharkattack”unless themotivationandintentofthesharkareclearlyestablishedbyexperts,whichisrarelythe

case.Untilnewscientificinformationappearsthatbetterexplainsthephysical,chemical, andbiologicaltriggersleadingsharkstobitehumans,werecommendthattheterm“shark attack”beavoidedbyscientists,governmentofficials,themedia,andthepublicinalmost allincidencesofhuman–sharkinteraction.

Followingthereleaseofthisresearch,Shiffman[21]noted,“TheAmericanElasmobranchSociety,theworld’slargestprofessionalorganizationofsharkandrayscientists,has issuedaresolutioncallingontheAssociatedPressStylebookandtheReutersStyleGuide toretirethephrase“sharkattack”infavorofamoreaccurate(andlessinflammatory) wordingthatisscaledtorepresentrealriskandoutcomes”.

Thecontestednatureofhuman–sharkinteractiondiscoursecanalsobeseenininternationalexamplesofthewayinstitutesrefertosharkincidents.Inreactiontothisgrowing trend,theGlobalSharkAttackFilechangeditsnametotheGlobalSharkAccidentFile (andusesbothattackandincident)andtheAustralianSharkAttackFile(foundedin1984) changeditsnametotheAustralianShark-IncidentDatabase.Theyrefertothemselvesas “Australia’sleadingsourceofsharkbitedata”.ThisisimportanttonotebecausetheAustralianShark-IncidentDatabaseisajointpartnershipwithTarongaConservationSociety Australia,FlindersUniversity,andtheAustralianstateofNewSouthWales’sDepartment ofPrimaryIndustries,agovernmentportfolio.However,theInternationalSharkAttack FileinFloridastillutilizes“sharkattack”languageinitstitle.

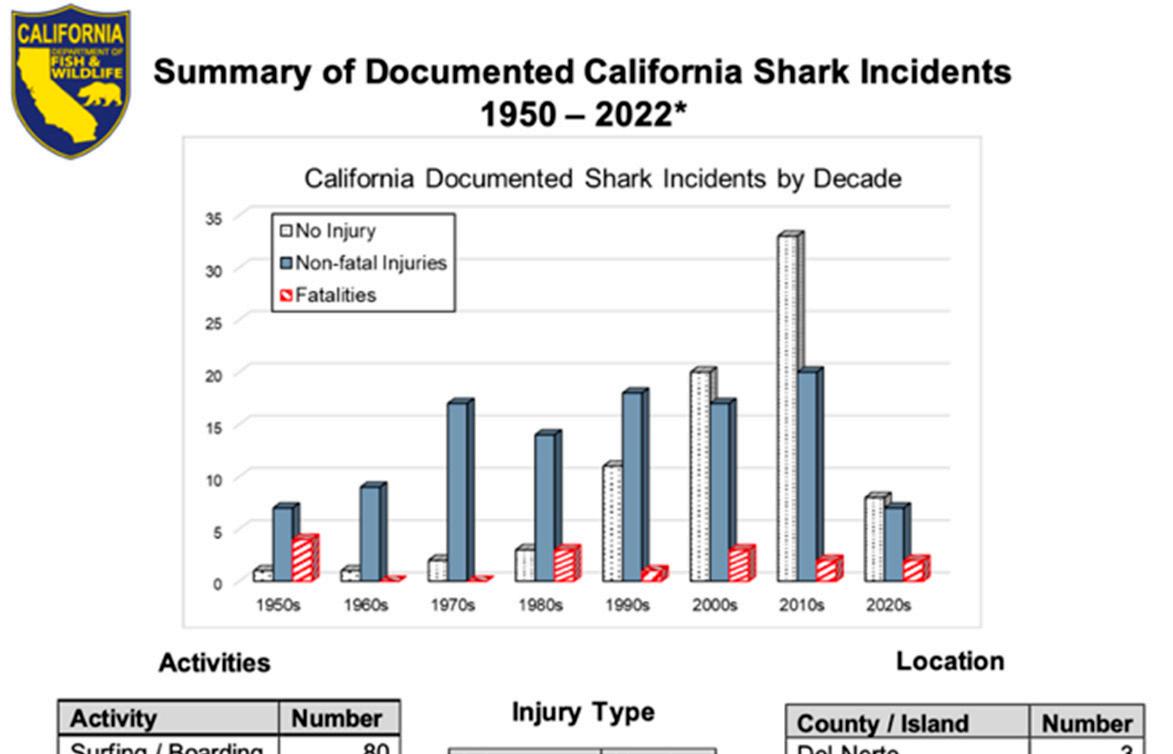

CapeCodNationalParksServicereferstosharkincidentsassharkbites[22].Thestate ofCaliforniahasupdatedtheirlanguageforreportingonhuman–sharkinteractions.The stateofCalifornia’sSharkIncidentReport[23]notestwothingsthatareimportant.First, theuseofthephrase“sharkincident”isusedanddefinedas:“*Asharkincidentisdefined asanydocumentedcasewhereasharkapproachedandtouchedapersoninthewater,or touchedaperson’ssurfboard,kayak,paddleboard,etc.Thissummarydoesnotinclude sharksightingswherenocontactoccurred,instanceswheresharksapproachedboats,or caseswherehookedsharkscausedinjuryordamage”.

AccordingtothestateofCaliforniastatistics,39%ofsharkincidents(79of203)dating fromthe1950’stothepresentinvolvednoinjury(seeFigure 1).ThisissimilartotheNeff andHueter[14]analysis,whichfoundthat38%ofgovernmentreportedhuman–shark interactionsbetween1979and2009hadnoinjury.Inshort,thisisanimportantdata pointtoreceiveaffirmationbyanothersource.AddingtothisisdatafromtheAustralian Shark-IncidentDatabase(Meagher,2021)thatshows34%ofincidentsinvolvenoinjury (405of1196).

Inaddition,theQueenslandSharkManagementPlan2021–2025doesnotincludethe phrase“sharkattack”butdoesusethephrase“sharkbite”13times[24].Additionally, thestateofWesternAustralia’s2021report,entitled:“Resultsofthenon-lethalSMART drumlinetrialinsouth-westernAustraliabetween21February2019and20February2021” onlyusesthephrase“sharkattack”whenquotingothersorwithincitations.Theyreferto “sharkbiteincidents”andshark“bite”9times.

TheCityofCapeTownuses“unprovokedsharkbites”noting,“InSouthAfrica,there havebeen249confirmed,unprovokedsharkbitesonhumansinthepast111years”.While theCapeTownfundedSharkSpottersprogramusesboth“sharkattack”and“sharkbite incident”languageonitswebsite,stating“ThelastsharkbiteinCapeTownwasinAugust 2014justoffSunrisebeachnearMuizenberg”.

Figure1. StateofCaliforniaReportonSharkIncidents.

1. State of California Report on Shark Incidents.

In addition, the Queensland Shark Management Plan 2021–2025 does not include the phrase “shark attack” but does use the phrase “shark bite” 13 times [24]. Additionally, the state of Western Australia’s 2021 report, entitled: “Results of the non-lethal SMART drumline trial in south-western Australia between 21 February 2019 and 20 February 2021” only uses the phrase “shark attack” when quoting others or within citations. They refer to “shark bite incidents” and shark “bite” 9 times.

The City of Cape Town uses “unprovoked shark bites” noting, “In South Africa, there have been 249 confirmed, unprovoked shark bites on humans in the past 111 years”. While the Cape Town funded Shark Spotters program uses both “shark attack” and “shark bite incident” language on its website, stating “The last shark bite in Cape Town was in August 2014 just off Sunrise beach near Muizenberg”.

Fifth,thiscontestationoflanguageisconsistentwithpublicattitudes.Intwodifferent surveys,respondentsindicatedthat“sharkattack”isoverused[3].Thestudiesconducted ofresidentsinAustraliainBallina(n=500)in2015andPerth(n=600)in2016following aseriesofsharkbitesaffectingthosecommunities,respondentswereaskedinthetwo separatesurveysifthey“agreethattheterm“sharkattack”wastoosensationalizedby themedia.Datashowthat66%ofrespondentsfromBallina(n=331)and67%from Perth(n=400)agreedthatthetermsharkattackwastoosensational,whileinboth32% disagreed,withBallina(n=161)andPerth(n=190).Inbothcases,just2%wereunsure. Thissurveyinvolved400peopleintheFederalSeatofPerthaswellasanoversampleto ensure100fromeachofthetwolocationsinMundurahandMindarie.Inaddition,53%of Ballinaresidentsstatedsharkbitesare“accidental”,withjust22percentdescribingthemas “intentional”andtheremaining25percentundecided.InthePerthsurvey,amajority(52%) ofthosesurveyedstatedthattheybelievedsharkbitesareaccidents,ratherthanintentional (22%)andnotsure(26%).Therefore,theunderpinningsofthe“sharkattack”narrative appearstobedissipating.Additionally,alargermajority(59%)ofthosesurveyedinPerth alsobelievedthat“noone”wastoblamewhensharkbitesoccur”.

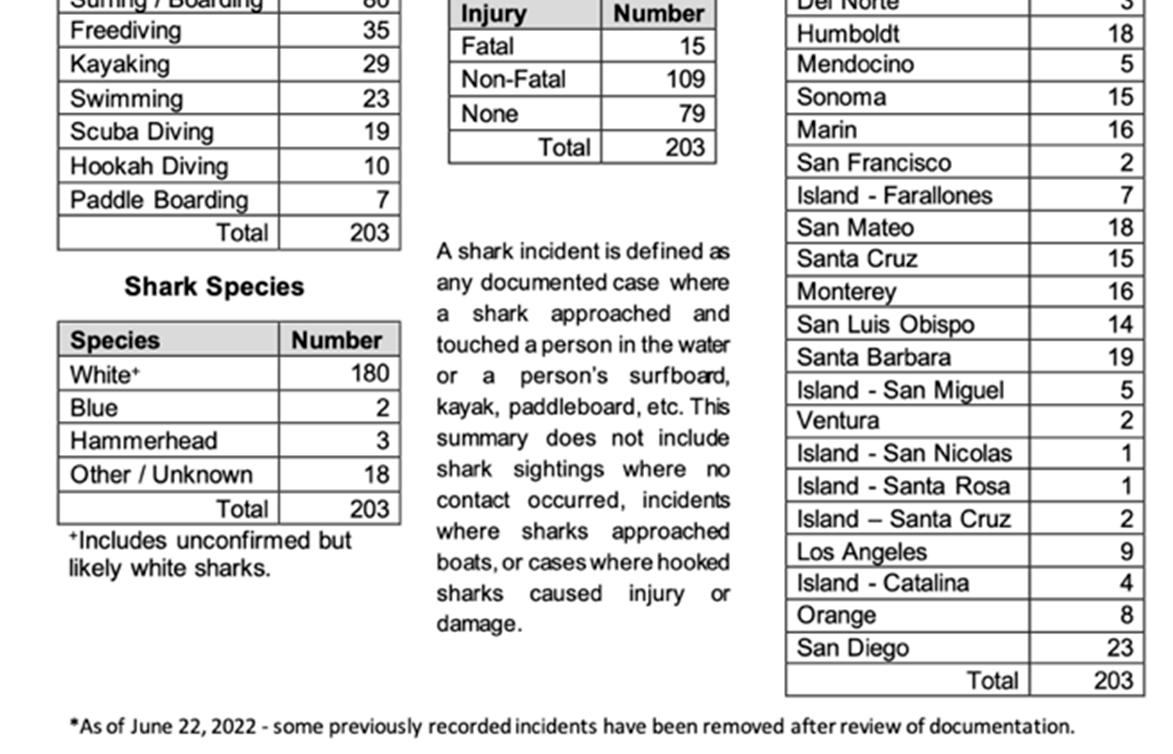

Movingforward,thisreportreviewsreportinglanguagefor36articlesfromTheNew YorkTimesbetween2012and2021withthelexiconofhuman–sharkinteractionsinmindto conductamediacontentanalysisofreportingonhuman–sharkinteractions.Forinstance, asnippetoftext,295wordsfromTheNewYorkTimesin2020showstheword“attack” appear13times,oronceevery23words(seeFigure 2).

Fifth, this contestation of language is consistent with public attitudes. In two different surveys, respondents indicated that “shark attack” is overused [3]. The studies conducted of residents in Australia in Ballina (n = 500) in 2015 and Perth (n = 600) in 2016 following a series of shark bites affecting those communities, respondents were asked in the two separate surveys if they “agree that the term “shark attack” was too sensationalized by the media. Data show that 66% of respondents from Ballina (n = 331) and 67% from Perth (n = 400) agreed that the term shark attack was too sensational, while in both 32% disagreed, with Ballina (n = 161) and Perth (n = 190). In both cases, just 2% were unsure. This survey involved 400 people in the Federal Seat of Perth as well as an over sample to ensure 100 from each of the two locations in Mundurah and Mindarie. In addition, 53% of Ballina residents stated shark bites are “accidental”, with just 22 percent describing them as “intentional” and the remaining 25 percent undecided. In the Perth survey, a majority (52%)

Thematerialandmethodsarereviewedbylookingatthereasonsforselectingthe casestudyofTheNewYorkTimes,thegatheringofdata,andoperationalizethedata.

TheNewYorkTimesmediareportswerechosenastheunitofstudybecauseitisthe recognizedpaperofrecordintheUnitedStates,andaleadingpublicationofinfluence aroundtheworld.Inaddition,theyareanauthoritativepublisherofstoriesreplated tohuman–sharkinteractions,havingpublishedtheirfirststoryin1865,coveringthe 1916sharkdisasterinNewJersey,andthesummerofthesharkin2000.

NewYorkTimesarticleswereselectedfollowingaFactivasearchthatwasrefined basedonthepublication,publicationdate,andkeywords.Atotalof36NewYorkTimes newspaperarticleswereselectedfrombetween2012and2021toprovideasuitableperiod fromtheintroductionofNeffandHueter[14]tothepresent.Articlesweregathered chronologicallyusingFactivasoftwarewiththeprimarykeywordbeing“sharkattack” (n=14).Secondarykeywordsweregatheredfrom36articlesandincluded“sharkbite” (n=12),shark“sighting”(n=7)“incident”(n=5),andshark“encounter”(n=3).Keywords wereselectedconsistentwithothermediaanalysesofhuman–sharkinteractionsandwere inclusiveofheadlinesandarticlebodytext.Articleswerefilteredtoensuretheyare addressinghuman–sharkinteractionsratherthanloansharks,Babyshark,cardsharks,or thenamesofsportsteams.Dailytelevisionlistingswithrecapswerealsoremoved.The numberofincidentsper5-yearaverageis72,with5–6fatalities[17].Theaveragenumber ofreportedbitesisgreaterthanthenumberofNewYorkTimesarticlesonhuman–shark interactionseachyear;however,itisnoteworthythat2020recordedthehighestnumberof fatalitiessince2013,seeTable 1.

Table1. InternationalSharkAttackFile:Worldunprovokedtotals.

Datawerelookedatincontextbyprintingoutandreadingeacharticle.Headlines werenotedaswellasthearticletext.Thediscourseandlexiconofhuman–sharkinteractions includes:“incidents,sharkbite,sharkattack,sharksighting,andsharkencounter”.Articles wereexaminedforthesekeywords.Propernounswereincluded,suchastheInternational SharkAttackFilebecausetheyreinforce(perhapsmoresothananyquoteorcomment)the toleranceforthespecificlanguage.Randomarticleswiththeword“sharkattack”were removedtoestablishthe10-yearcorearticles.Resultsweredouble-checkedtoensure inter-coderreliabilitybyaresearchstudent.

Inareviewof36NewYorkTimesarticlesonhumansharkinteractionsacross10years (2012–2021)therewereseveralfindings.Data(descriptormentions)wereanalyzedand separatedforcontentanalysisbasedonthewaytheyhighlighteddifferentdiscourseusage.

(1) “Sharkattack”or“attack”appearedintheheadlinein11of36articles(30%).One article(Barnard,2021)had“sharksighting”intheheadline[14].Noarticleshadshark “bite”intheheadline.Eacharticleexaminedwaswrittenbyadifferentauthor.

“bite” in the headline. Each article examined was written by a different author.

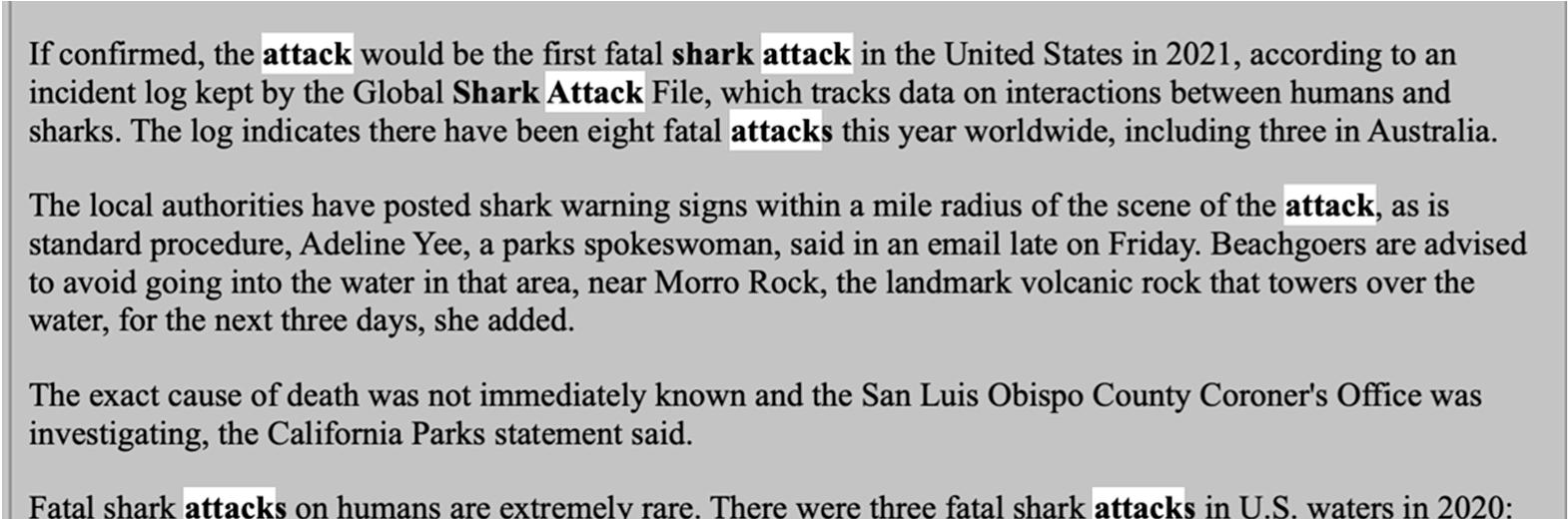

(2.) In Figure 3, shark “attack” and shark “bite” mentions are compared and highlight a potential shift in reporting style at The New York Times that provides new emphasis on shark “bite” as a descriptor for human-shark interactions since 2018.

(3.) In Figure 4, all keywords (bite, attack, sighting, incident, encounter) were compared by year. The data show that all The New York Times articles on human–shark interactions that mentioned shark “attacks” in 2021 (n = 5) and 2020 (n = 3) also mentioned shark “bites”. This was also the case in 2018 (n = 3).

(2) InFigure 3,shark“attack”andshark“bite”mentionsarecomparedandhighlighta potentialshiftinreportingstyleatTheNewYorkTimesthatprovidesnewemphasis onshark“bite”asadescriptorforhuman-sharkinteractionssince2018.

(3) InFigure 4,allkeywords(bite,attack,sighting,incident,encounter)werecomparedby year.ThedatashowthatallTheNewYorkTimes articles onhuman–sharkinteractions thatmentionedshark“attacks”in2021(n=5)and2020(n=3)alsomentionedshark “bites”.Thiswasalsothecasein2018(n=3).

(4.) There were nearly three times the number of mentions of shark “bite” in 2021 (n = 34) as there were in 2018 (n = 13), see Figure 5. This data also suggests an increase in “shark bite” descriptor usage at The New York Times since 2018.

(5.) Shark “sighting” is the third most common phrase to be mentioned in New York Times articles in 2021 (n = 7 mentions) and 2020 (n = 4 mentions).

(4) Therewerenearlythreetimesthenumberofmentionsofshark“bite”in2021(n=34) astherewerein2018(n=13),seeFigure 5.Thisdataalsosuggestsanincreasein “sharkbite”descriptorusageatTheNewYorkTimessince2018.

(5) Shark“sighting”isthethirdmostcommonphrasetobementionedinNewYork Timesarticlesin2021(n=7mentions)and2020(n=4mentions).

(6) Overall,whileshark“bite”mentionshaveincreased,thedatahighlightthatindividual mentionsofshark“attack”peryearatTheNewYorkTimesstillconstitutethemost prevalentlanguageselectioninreportingonhuman-sharkinteractionsin2021(n=51). Indeed,twoarticlesin2021inparticularaccountforsomeoftheriseinshark“bite” descriptorswith(n=12mentions)and(n=16mentions),respectively.

(6.) Overall, while shark “bite” mentions have increased, the data highlight that individual mentions of shark “attack” per year at The New York Times still constitute the most prevalent language selection in reporting on human-shark interactions in 2021 (n = 51). Indeed, two articles in 2021 in particular account for some of the rise in shark “bite” descriptors with (n = 12 mentions) and (n = 16 mentions), respectively.

Figure 2. New York Times article with “attack” highlighted in the text. Figure2. NewYorkTimesarticlewith“attack”highlightedinthetext.

Figure 3. Contains data on the number of articles per year that mention each descriptor for human–shark interactions (n = 36).

Figure 3. Contains data on the number of articles per year that mention each descriptor for human–shark interactions (n = 36).

Figure

Figure3. Containsdataonthenumberofarticlesperyearthatmentioneachdescriptorforhuman–sharkinteractions(n=36).

NY Times reporting descriptors for human-shark interactions between 2012-2021 by number of

NY Times reporting descriptors for human-shark interactions between 2012-2021 by number of articles

NY Times reporting descriptors for human-shark interactions between 2012-2021 by number of articles

Figure 4. Number of descriptors mentioned per year in

Figure 4. Number of descriptors mentioned per year in The New York Times articles (n = 36).

Figure4. NumberofdescriptorsmentionedperyearinTheNewYorkTimesarticles(n=36).

Figure 4. Number of descriptors mentioned per year in The New York Times articles (n = 36).

Number of total shark "bite" mentions in NY Times articles per year between 2017--2021

Figure

Figure 5. Contains data on the number of total shark “bite” mentions in

Figure 5. Contains data on the number of total shark “bite” mentions in NY Times articles per year between 2017–2021.

Figure5. Containsdataonthenumberoftotalshark“bite”mentionsinNYTimesarticlesperyear between2017–2021.

Thepreliminaryresultssuggesttwotypesofresponsesoverthe10-yearperiodbetween2012and2021.Thefirstisbasedonthenatureofindividualoccurrencesandmay reflectanindividualreporter’sdiscursivepreferences(between2012–2017).Thesecond; however,pointsaninstitutionalresponsethatismorelayeredandsuggestsachangein reportingstyleatTheNewYorkTimesregardinghuman–sharkinteractions(since2018).

Thedataindicatesanincreaseduseofvarieddiscourseinrecentyearsincluding shark“bites,attack,incident,sightingandencounter”.Thesetermsrepresentanew approachbythemediatowardalayeredreportingonhuman–sharkinteraction.This datacanbeinterpretedfromtheperspectiveofpreviousstudiesonmediarelationsand sharks[12–15].IfindthatTheNewYorkTimesisdiversifyingtheirdiscoursearound human–sharkinteractionsandthatthisisconsistentwithagrowinginternationaltrend awayfromthesingularadoptionof“sharkattack”asanappliedphrase.Theimplications ofthisresearchhighlighttheimportanceofavariedlexiconandvocabularytorepresentthe multi-dimensionalnatureofhuman–sharkinteractions.Futureresearchshouldexamine broadertrendsinmediareporting,particularlyasscientificbodiesfocusontheAssociated Press’StyleGuideasanothermediaindustrystandard.

Theadoptionofalayeringapproachtomediareportingonhuman–sharkinteractions wouldmarktheendoftheculturalmonopolyof“sharkattack”languageutilizationasa catch-allterm.Shark“attack”isaone-dimensionalrepresentationthatassumesknowledge ofsharkbehavioralintent,sensationalizeshuman–sharkinteractions,providesablanket labelthatassumesallsharksaredangerous,canbeusedpoliticallytoundermineshark conservation[25]andfailstoscientificallyrepresentthevarietyofpossibleexperiencesthat peoplecanhavewithsharks.Theimplicationsofthisspecificphrase’suseincludeharm tohumanpopulationsbecausethenatureoftheriskposedbysharksismisrepresented andleadstoafundamentalmisunderstandingofsharks.Ifthepublicknewthatnearly 40%ofreportedshark“attacks”hadnoinjurythiscouldchangeabuildingblockofmarine scienceeducation[18].Morevariedtextinmediaportrayalsillustratesthevarietyof differenttypesofhuman–sharkinteractionsthatareimportanttopubliccommunication andriskmitigation.

Inall,human–sharkinteractionresearchisagrowingareaofmarinesocialscience.This articleillustratesjustoneaspectofhowhuman–sharkinteractionshasbecomeagrowing interdisciplinarysub-fieldofhuman–sharkrelationswithinmarinesocialscience[26]. Thisemergingsub-fieldlookingathuman–sharkrelationsrelativetomarinebiology[27], geography[28],politicalscience[29],conservation,filmstudies[30],communications[31]. Thisarticlecontributestoademonstrated“sharkturn”insocialscienceresearch.Further researchisneeded,butthisstudysuggeststhatthatthereisevidencetosupportanemerging trendindiversifieddescriptionsregardingthecollectionandreportingonhuman–shark interactionsatakeymediaoutlet.

ThequestiondrivingthisbriefreportaskedtowhatextentmediareportingbyThe NewYorkTimesengagesbeyondthelexiconof“sharkattack”discoursetodescribehuman–sharkinteractions.Ifoundthattherehasbeenanincreaseindiversifiedlanguageused inreportsabouthuman–sharkinteractionsatTheNewYorkTimes,includingsharkbites, attack,encounters,sightings,andincidentssince2020.

Additionally,“sharkattack”discoursehasapowerfulinfluenceonfeartowardsharks bytellingastoryaboutacreaturethatintentionallyeatshumans,ratherthanafishthat accidentallyormistakenlybitespeopleonexceptionallyrareoccasions.Finally,itisuseful tonotethattheNeffandHueter(2013)typologyisapplicablemorebroadlyandcouldbe usedforotheranimalencounters,bothwater-basedandterrestrial.

Funding: Thisresearchreceivednoexternalfunding.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Datasupportingreportedresultscanbeobtainedforfreebyemailing theauthoratchris.pepin-neff@sydney.edu.au.

Acknowledgments: Theauthorwishestothanktheanonymousreviewersfortheirfeedback.Special thanksaswelltoBenOrmerodfortheirresearchassistance.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

References

1. NewYorkTimes. FightwithaShark;NewYorkTimesSunday:NewYork,NY,USA,1865.

2. Pepin-Neff,C.L. Flaws:SharkBitesandEmotionalPublicPolicymaking;Springer:Berlin/Heidelberg,Germany,2019.

3. Pepin-Neff,C.;Wynter,T.Sharkbitesandsharkconservation:Ananalysisofhumanattitudesfollowingsharkbiteincidentsin twolocationsinAustralia. Conserv.Lett. 2018, 11,e12407.[CrossRef]

4. Ostrovski,R.L.;Violante,G.M.;deBrito,M.R.;Valentin,J.L.;Vianna,M.Themediaparadox:Influenceonhumanshark perceptionsandpotentialconservationimpacts. Ethnobiol.Conserv. 2021, 10,1–15.[CrossRef]

5. Robertson,K. NewYorkTimesReaches9.1MillionSubscribers;NewYorkTimes:NewYork,NY,USA,2022.Availableonline: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/04/business/media/new-york-times-q1-earnings.html (accessedon7September2022).

6. Muter,B.A.;Gore,M.L.;Gledhill,K.S.;Lamont,C.;Huveneers,C.AustralianandUSnewsmediaportrayalofsharksandtheir conservation. Conserv.Biol. 2013, 27,187–196.[CrossRef]

7. Crossley,R.;Collins,C.M.;Sutton,S.G.;Huveneers,C.Publicperceptionandunderstandingofsharkattackmitigationmeasures inAustralia. Hum.Dimens.Wildl. 2014, 19,154–165.[CrossRef]

8. Hazin,F.H.;Burgess,G.H.;Carvalho,F.C.AsharkattackoutbreakoffRecife,Pernambuco,Brazil:1992–2006. Bull.Mar.Sci. 2008, 82,199–212.

9. Carlson,J.K.;Heupel,M.R.;Young,C.N.;Cramp,J.E.;Simpfendorfer,C.A.Arewereadyforelasmobranchconservationsuccess? Environ.Conserv. 2019, 46,264–266.[CrossRef]

10. Lemahieu,A.;Blaison,A.;Crochelet,E.;Bertrand,G.;Pennober,G.;Soria,M.Human-sharkinteractions:Thecasestudyof Reunionislandinthesouth-westIndianOcean. Ocean.Coast.Manag. 2017, 136,73–82.[CrossRef]

11. Gibbs,L.;Warren,A.KillingSharks:Culturesandpoliticsofencounterandthesea. Aust.Geogr. 2014, 45,101–107.[CrossRef]

12. StephenColbert,20July2021.Meanwhile WallyFunkIstheStarofBezos’BlueOriginSpaceMission.TheLateShow. Availableonline: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgH-itFA_hg (accessedon20August2022).

13. TuckerCarlsonTonightwithTuckerCarlson.DavePortnoyFiercelyDefendsthisControversialTopicon‘Tucker’.2021.Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yBNejdDxBmA (accessedon20August2022).

14. Barnard,A. BelieveItorNot,NewYorkBeachgoers,YouCanRelaxAbouttheSharkSightings;TheNewYorkTimes:NewYork,NY, USA,2021.

15. Neff,C.;Hueter,R.Science,policy,andthepublicdiscourseofshark“attack”:Aproposalforreclassifyinghuman–shark interactions. J.Environ.Stud.Sci. 2013, 3,65–73.[CrossRef]

16. Coppleson,V.SharkattacksinAustralianwaters. Med.J.Aust. 1933, 1,449–467.[CrossRef]

17. Schulze,L.P.Attacksbysharksasrelatedtotheactivitiesofman.In SharksandSurvival;DCHeath&Co.:Boston,MA,USA,1963.

18. Eilperin,J. DemonFish:TravelsthroughtheHiddenWorldofSharks;Anchor:NewYork,NY,USA,2011.

19. ISAF. InternationalSharkAttackFile:YearlyWorldwideSharkAttackSummary.TheISAF2021SharkAttackReport.Florida. 2021.Availableonline: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/yearly-worldwide-summary/ (accessedon 20August2022).

20. NSW.ReportintotheNSWSharkMeshing(BatherProtection)Program;2009.NewSouthWalesDepartmentofPrimary Industries.Availableonline: Chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/ assets/pdf_file/0008/276029/Report-into-the-NSW-Shark-Meshing-Program.pdf (accessedon10August2022).

21. AustralianBroadcastingCorporation. MickFanningEscapesSharkAttackinJ-BayOpenSurfEventinSouthAfrica;Australian BroadcastingCorporation,2015.Availableonline: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-07-19/mick-fanning-clashes-with-sharkin-south-africa-surfing-event/6632214 (accessedon6September2022).

22. Shiffman,D. World’sLargestGroupofSharkScientistsCallsonAPandReuterstoResistUsingthePhrase“SharkAttacks”;2013; SouthernFriedScienceBlog.Availableonline: https://www.southernfriedscience.com/worlds-largest-group-of-shark-scientistscalls-on-ap-and-reuters-to-resist-using-the-phrase-shark-attacks/ (accessedon10August2022).

23. NationalParksService.SharkSafetyatCapeCod. Natl.ParksServ. Lastupdated,11April2022.Onlinewebsite.Availableonline: https://www.nps.gov/caco/planyourvisit/sharksafety.htm (accessedon10August2022).

24. CaliforniaDepartmentofFishandWildlife.SummaryofDocumentedCaliforniaSharkIncidents.Availableonline: file: ///Users/cneff/Downloads/SharkIncidents_Summary_220811.pdf (accessedon10August2022).

25. QueenslandGovernment.QueenslandSharkManagementPlan2021–2025DepartmentofAgricultureandFisheries.2021. Availableonline: https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/fisheries/shark-control-program/plan#:~:text=Queensland% 20shark%20management%20plan%202021%E2%80%932025&text=reduce%20the%20risk%20of%20shark,community%20 education%20on%20SharkSmart%20behaviours (accessedon20August2022).

26. Neff,C.TheJawsEffect:HowmovienarrativesareusedtoinfluencepolicyresponsestosharkbitesinWesternAustralia. Aust.J. PoliticalSci. 2015, 50,114–127.[CrossRef]

27. Resko,D.M.;Johnson,A.M.AnAnalysisofSharkAttacksintheStateofFlorida. Fla.Geogr. 2014, 45,28–40.

28. Neff,C.Australianbeachsafetyandthepoliticsofsharkattacks. Coast.Manag. 2012, 401,88–106.[CrossRef]

29. Sabatier,E.;Huveneers,C.Changesinmediaportrayalofhuman-wildlifeconflictduringsuccessivefatalsharkbites. Conserv.Soc. 2018, 16,338–350.[CrossRef]

30. LeBusque,B.;Litchfield,C.Sharksonfilm:Ananalysisofhowshark-humaninteractionsareportrayedinfilms. Hum.Dimens. Wildl. 2022, 27,193–199.[CrossRef]

31. Chapman,B.K.;McPhee,D.Globalsharkattackhotspots:Identifyingunderlyingfactorsbehindincreasedunprovokedsharkbite incidence. Ocean.Coast.Manag. 2016, 133,72–84.[CrossRef]