The

Hurricane That Changed America

Hurricane That Changed America

Stories of perseverance two decades later

EDITOR

Colleen McMillar

DESIGNER

Joey Schaffer

PROOFREADER

Heather Hewitt

PROJECT COORDINATOR

Gene Myers

Hurricane Katrina remains a singularly agonizing American disaster. On the morning of Aug. 29, 2005, the storm barreled ashore and ravaged 90,000 square miles, mostly in south Louisiana and along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. It also led to the catastrophic failure of the levee system in New Orleans.

But the storm reverberated far beyond the Gulf Coast. Hurricane Katrina exposed deep flaws in our country’s disaster preparedness and response. And, while many chose to come back to the region as soon as they could, tens of thousands of former residents remain scattered throughout the nation.

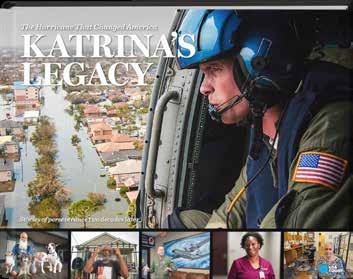

FRONT: Coast Guard Petty Officer 2nd Class

Shawn Beaty, 29, of Long Island, N.Y., looks for survivors in the wake of Hurricane Katrina on Aug. 30, 2005. Beaty is a member of an HH-60 Jayhawk helicopter rescue crew sent from Clearwater, Fla., to assist in search and rescue efforts. PETTY OFFICER 2ND CLASS NYXOLYNO CANGEMI / U.S. COAST GUARD

BACK: Debris from Hurricane Katrina covers a neighborhood in Pascagoula, Miss., on Aug. 30. TONY GIBERSON / PENSACOLA (FLA.) NEWS JOURNAL

OPPOSITE: A lone man wades through floodwaters in New Orleans, six days after Hurricane Katrina passed through the area.

MICHAEL MADRID / USA TODAY

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner or the publisher.

Published by Pediment Publishing, a division of The Pediment Group, Inc. • www.pediment.com • Printed in Canada.

Maria Maginnis is carried by her husband, David Maginnis, through floodwaters in their Old Metairie neighborhood. For the first time since Hurricane Katrina slammed into metro New Orleans on Aug. 29, 2005, residents of Jefferson Parish were allowed to return during a 12-hour window Sept. 5 to check on their homes. The couple grabbed some belongings, including a New Orleans Saints jersey and the family fish Swimmy, which Maria is carrying in a plastic cup. JACK GRUBER / USA TODAY

BY LICI BEVERIDGE, HATTIESBURG AMERICAN AND CLARION LEDGER

AS LT. COL. SEAN CROSS, A HURRIcane hunter, conducted a reconnaissance mission over the Atlantic to monitor the brewing storm, he knew Hurricane Katrina was going to be a bad one.

“All I could think of was the people down below and how their lives would be changed,” he said.

Cross, a member of the 403rd Wing

of the U.S. Air Force Reserves at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, had flown in hundreds of reconnaissance missions over the years, so his eyes and his gut were telling him what to expect.

The New Orleans native had moved to the Mississippi Coast after joining the Hurricane Hunters. As it turned out, his home, too, would be damaged by Katrina, but not as much as others on his team who lost everything.

“They showed up to work with bags of

whatever they had left, ready to work,” he said. “Many of them didn’t even know what their homes looked like. They just got back to work.”

Hurricane Katrina annihilated the Gulf Coast and prompted the largest population displacement in America since the Dust Bowl. USA TODAY Network journalists explored how the storm, its victims and responders have continued to impact communities around the nation

LEFT: Lt. Col. Sean Cross, chief of safety for the 403rd Wing, based at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss., is one of the few people who are still in active service and flew inside Hurricane Katrina.

BARBARA GAUNTT / MISSISSIPPI CLARION LEDGER

Costliest inflation-adjusted weather disasters globally, according to EM-DAT, NOAA and Gallagher Re. Two of the top 10 occurred in 2024 and 2025. This is for total economic damage, not just insured. Compiled by Yale Climate Connections, an independent and nonpartisan initiative staffed by professional journalists, meteorologists and radio producers.

BY COLLEEN MCMILLAR

FEW IN NEW ORLEANS WERE PAYing attention as a tropical depression formed 900 miles to the east, over the Bahamas, on Tuesday, Aug. 23, 2005.

The Crescent City was nearing the end of a typically lazy summer season, when the tourist numbers drop as the temperatures rise. Despite the 90-degree days, with no hint of relief in sight, many of us were looking longingly ahead to the promise of autumn.

A new year had just begun for the city’s 126 public schools. Irrational optimism was still flowing from the Saints’ preseason victory, four days earlier, over the reigning Super Bowl champion New England Patriots. Southern Decadence, the annual LGBTQ festival, was expected to bring to town tens of thousands of visitors for Labor Day weekend.

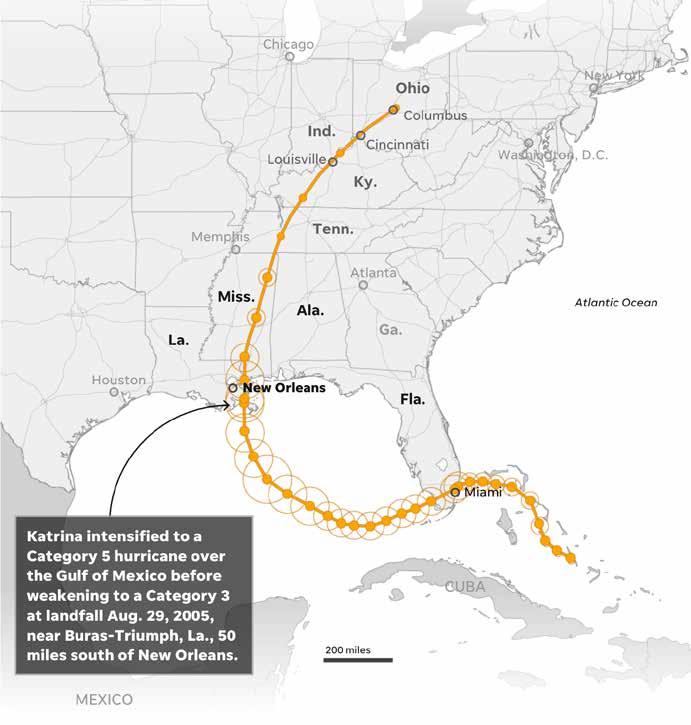

As a distracted New Orleans shook off the summer doldrums, the distant tropical depression became Tropical Storm Katrina. By Thursday, Aug. 25, it was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane that pummeled southeastern Florida, leaving 14 dead as it crept west across the state.

The next day, Katrina entered the warm waters of the Gulf, where it churned and gathered strength. The National Hurricane Center initially projected that

the storm’s eye would pass through the Florida Panhandle. But, on that Friday at 10 p.m. CDT, roughly 56 hours before the hurricane would make another landfall, the hurricane center’s prediction tilted westward.

Now, the central Gulf Coast, including metro New Orleans, was squarely in the hurricane’s sights.

Twenty years later, Hurricane Katrina remains a singularly agonizing American disaster. On the morning of Aug. 29, 2005, the storm — by then at Category 3 strength and packing 125 mph winds — barreled ashore and ravaged 90,000 square miles, mostly in south Louisiana and along the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

In New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina led to the catastrophic failure of the levee system, later found to be poorly designed and shoddily constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The consequences of this failure — and a dawdling federal response — were grave in a city that’s largely below sea level.

By modern standards, the numbers are daunting for a disaster on U.S. soil. The death toll, adjusted downward over the years, has been officially set by the National Hurricane Center at 1,392 people. Katrina remains the costliest hurricane in American history: $201.3 billion when adjusted for inflation.

In all, more than a million housing units in the Gulf Coast region were damaged, according to the Data Center, an independent research organization in southeast Louisiana. Roughly half of those were in Louisiana, including 134,000 in New Orleans. But the storm reverberated far beyond the Gulf Coast. This was the first big test for the Department of Homeland Security, formed four years earlier in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. By its own admission, the department — which includes the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) — failed. Katrina exposed deep flaws in our country’s disaster preparedness and response. In New Orleans, tens of thousands were trapped in a drowning city for nearly a week because of communication breakdowns and a lack of coordination between the federal government and overwhelmed state and local officials.

Deeply etched in the nation’s memory are jarring images and video from New Orleans, 80% of which was engulfed by water: People stuck on rooftops waiting, sometimes for days, to be rescued; families using makeshift rafts to get the very young and the frail to dry land; corpses in the streets; survivors scavenging for food and supplies; thousands of residents — many poor, Black, elderly or sick — stranded at the Superdome and

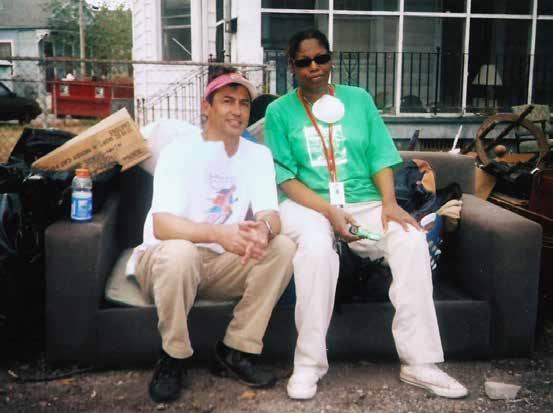

RIGHT: Colleen McMillar’s Mid-City home was among the many residences flooded after the levee breaks in New Orleans. McMillar, this book’s editor and the writer of the foreword, is pictured here with her friend and Times-Picayune co-worker Robert Rhoden, who helped her drag waterlogged contents to the curb.

Convention Center in scorching heat, without adequate food and water.

Katrina displaced more than a million Louisiana and Mississippi residents. In the month following the storm, evacuees were scattered throughout the nation. FEMA and Postal Service records showed evacuees registered in every state and almost half of all U.S. ZIP codes.

Around the country, everyday Americans responded to the Gulf states’ plight, organizing fundraisers and donating money in record amounts. Everyday Americans opened their homes to evacuees. Everyday Americans put boots on the ground, working alongside locals to clear debris and rebuild communities.

In other states, government officials opened shelters, held job fairs for the displaced and found permanent housing for those who wanted to start anew.

Most Louisiana and Mississippi evacuees eventually made their way back home. In some cases, it took only days. In other cases, especially for metro New Orleans residents, it took weeks, months and even years.

The profound resoluteness of those who returned — facing overwhelming destruction and an arduous recovery — pulled New Orleans and cities and towns up and down the Gulf Coast back from the brink. Other evacuees resettled in other states, often by choice but sometimes not. In their resilience, they built new lives in those new places.

I lived in New Orleans from 1992 until the beginning of 2006. Four months after Katrina, I left the city that I consider my spiritual home — still — and my job as a journalist at the local newspaper, The

Times-Picayune. I took a job as an editor at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

I had always known that I would eventually make my way back to my native Georgia to be closer to my sister and aging mother, who lived in Macon. Katrina forced my hand. The flooding rendered my apartment, in a Mid-City “double,” or duplex, unlivable. It also took most of my worldly possessions.

When I got to Georgia, back to a land with stores and restaurants and mail service, I needed everything: a car, furniture, clothes, a place to live.

A woman, whom I had never met and only knew of through a mutual friend,

rented me the bottom floor of her townhouse. Cathy, a deeply empathetic Chicago transplant, welcomed me like family. She didn’t need the money. She wanted to help. Today, as far as I’m concerned, this fanatical Cubs fan is family.

These pages recount a disaster that left an indelible mark on a nation. And I hope these words and pictures give voice to those who showed strength and resilience when one of the country’s worst natural disasters and engineering failures turned their worlds upside down. Let it also give voice to fellow Americans who were there, when everything went wrong, to help pick up the pieces.

LEFT: A spray-painted roof sends a message that a Waveland, Miss., homeowner is alive on Aug. 31, 2005. Two days before, Hurricane Katrina swept through the area.

BEN TWINGLEY / PENSACOLA (FLA.) NEWS JOURNAL

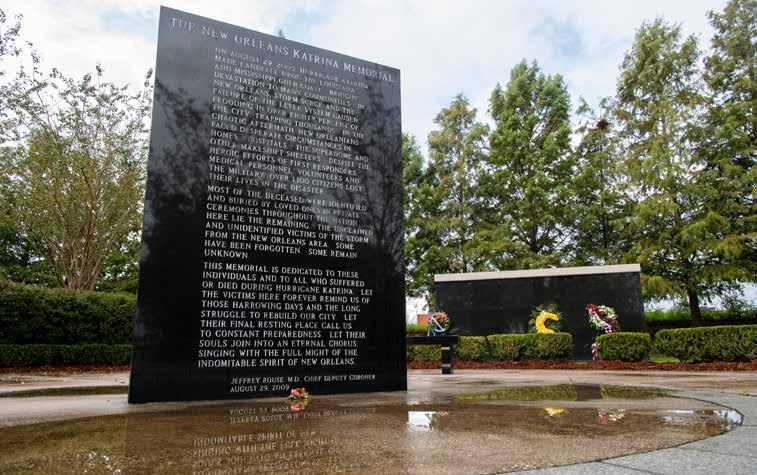

BELOW LEFT: A monument to the victims and survivors of hurricanes Katrina and Rita stands in the 4900 block of North Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward.

JASPER COLT / USA TODAY

TUESDAY, AUGUST 23

• A tropical depression forms over the southeastern Bahamas.

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 24

• The depression becomes Tropical Storm Katrina as it moves northwest.

THURSDAY, AUGUST 25

• Tropical Storm Katrina is upgraded to a Category 1 Hurricane Katrina before making landfall in South Florida, with 80 mph winds. The storm is linked to 14 deaths in the state.

• Hurricane Katrina weakens to a tropical storm during its six-hour saunter over land.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 26

78 hours before Gulf Coast landfall

• The storm moves over the eastern Gulf of Mexico, becoming a Category 2 hurricane by 11:30 a.m. EDT.

• Forecast models initially project it will come ashore in the Florida Panhandle. By midday, models show Hurricane Katrina moving west.

• Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Blanco and Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour declare states of emergency, allowing quick mobilization of resources, personnel and funding. They also call up their National Guards.

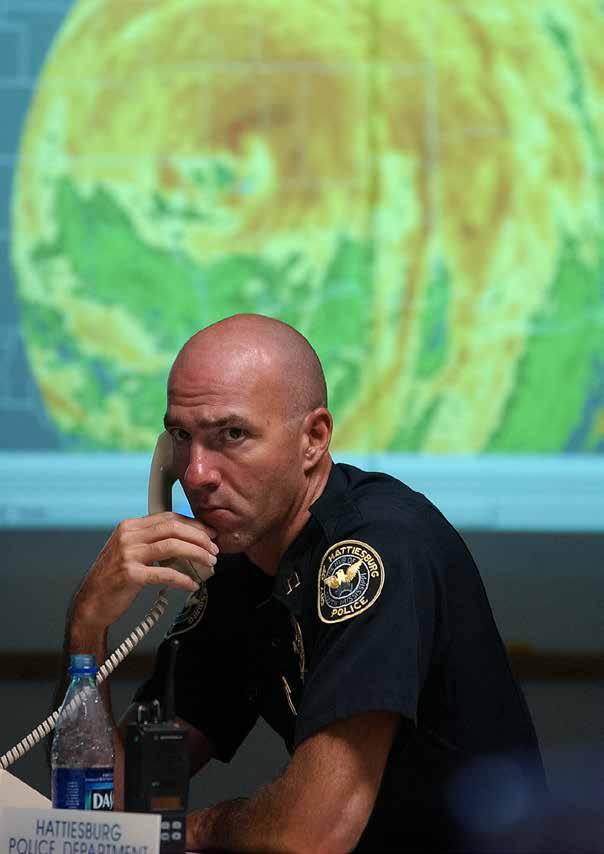

Police Capt. Mike Shappley works the phones at the HattiesburgForrest County Emergency Operations Center in Mississippi on Aug. 29, 2005. BART BOATWRIGHT / GREENVILLE (S.C.) NEWS

26 CONTINUED

Hurricane advisory, issued at 11 p.m. EDT, projects landfall in southeast Louisiana, now threatening New Orleans, a city of nearly 500,000 that’s brimmed by an extensive system of levees and floodwalls because half of its land lies below sea level. Another landfall is expected near the Louisiana-Mississippi border.

54 hours before Gulf Coast landfall. (Time is now in CDT instead of EDT)

• Hurricane Katrina reaches Category 3 strength, with its strongest winds at 115 mph.

• President George W. Bush signs a disaster declaration for Louisiana, which triggers the process for providing federal funds to state and local governments.

9 a.m.: Mandatory evacuations are ordered in Louisiana’s St. Charles and Plaquemines parishes, as well as for coastal areas of Jefferson Parish.

10 a.m.: A hurricane watch covers a wide expanse, from Morgan City, Louisiana, to the Alabama-Florida border.

3 p.m.: New Orleans Mayor C. Ray Nagin and officials in nearby parishes call for voluntary evacuation.

4 p.m.: Louisiana and Mississippi start contraflow on major highways, reversing the flow of traffic. All lanes are now outbound to aid in evacuation.

• The hurricane watch escalates to a hurricane warning.

7:30 p.m.: Hurricane Center Director Max Mayfield phones state officials to warn them of the storm’s intensity and its potential to be catastrophic, especially for New Orleans. Its low elevation and protective ring of levees make it essentially a bowl.

From late night to early afternoon the next day: Airlines begin shutting down service. Rental car companies close. Bus service is halted.

ABOVE LEFT: Technical crew chief Terry Lynch, a NOAA systems analyst, monitors computers and radar equipment during a research and reconnaissance flight to survey and penetrate the eyewall of Hurricane Katrina on Aug. 27, 2005. VALERIE ROCHE / FORT MYERS (FLA.) NEWS-PRESS

LEFT: LEFT: Adrian Beard of Mobile, Ala., works at boarding up a Ruby Tuesday in Gulfport, Miss., on Aug. 28, ahead of Hurricane Katrina’s arrival. JACK GRUBER / USA TODAY

AUGUST 28

Day before Gulf Coast landfall

Just after midnight: Katrina strengthens to Category 4, with 145 mph winds.

7 a.m: Katrina intensifies to Category 5, with maximum sustained winds peaking at 175 mph. The storm is immense, covering much of the Gulf from the U.S. to Mexico. Hurricane-force winds now extend about 125 miles from the center and tropical storm-force winds 230 miles from the center.

9 a.m.: New Orleans Mayor Nagin orders a mandatory evacuation, the first in the city’s history. A dusk curfew is set.

More than 1 million people in metro New Orleans have already or will flee the region, including an estimated 80% of the city’s population. About 100,000 people remain — many of them are sick, elderly or poor; others are unable or unwilling to leave. Roughly 30% of the city’s residents don’t own cars.

• In Mississippi and Alabama, officials order the evacuation of low-lying areas. In southern Mississippi, shelters begin filling up.

• Traffic is moving at a snail’s pace on major roads and highways.

28 CONTINUED

10:11 a.m.: BULLETIN

URGENT - WEATHER MESSAGE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE NEW ORLEANS LA

1011 A.M. CDT SUN AUG 28 2005 ...DEVASTATING DAMAGE EXPECTED... .HURRICANE KATRINA...A MOST POWERFUL HURRICANE WITH UNPRECEDENTED STRENGTH...RIVALING THE INTENSITY OF HURRICANE CAMILLE OF 1969. MOST OF THE AREA WILL BE UNINHABITABLE FOR WEEKS... PERHAPS LONGER. AT LEAST ONE HALF OF WELL CONSTRUCTED HOMES WILL HAVE ROOF AND WALL FAILURE. ALL GABLED ROOFS WILL FAIL...LEAVING THOSE HOMES SEVERELY DAMAGED OR DESTROYED. THE MAJORITY OF INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS WILL BECOME NON FUNCTIONAL. PARTIAL TO COMPLETE WALL AND ROOF FAILURE IS EXPECTED. ALL WOOD FRAMED LOW RISING APARTMENT BUILDINGS WILL BE DESTROYED. CONCRETE BLOCK LOW RISE APARTMENTS WILL SUSTAIN MAJOR DAMAGE...INCLUDING SOME WALL AND ROOF FAILURE. HIGH RISE OFFICE AND APARTMENT BUILDINGS WILL SWAY DANGEROUSLY...A FEW TO THE POINT OF TOTAL COLLAPSE. ALL WINDOWS

WILL BLOW OUT. AIRBORNE DEBRIS WILL BE WIDESPREAD...AND MAY INCLUDE HEAVY ITEMS SUCH AS HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES AND EVEN LIGHT VEHICLES. SPORT UTILITY VEHICLES AND LIGHT TRUCKS WILL BE MOVED.

THE BLOWN DEBRIS WILL CREATE ADDITIONAL DESTRUCTION. PERSONS... PETS...AND LIVESTOCK EXPOSED TO THE WINDS WILL FACE CERTAIN DEATH IF STRUCK. POWER OUTAGES WILL LAST FOR WEEKS...AS MOST POWER POLES WILL BE DOWN AND TRANSFORMERS DESTROYED. WATER SHORTAGES WILL MAKE HUMAN SUFFERING INCREDIBLE BY MODERN STANDARDS. THE VAST MAJORITY OF NATIVE TREES WILL BE SNAPPED OR UPROOTED. ONLY THE HEARTIEST WILL REMAIN STANDING... BUT BE TOTALLY DEFOLIATED. FEW CROPS WILL REMAIN. LIVESTOCK LEFT EXPOSED TO THE WINDS WILL BE KILLED. AN INLAND HURRICANE WIND WARNING IS ISSUED WHEN SUSTAINED WINDS NEAR HURRICANE FORCE...OR FREQUENT GUSTS AT OR ABOVE HURRICANE FORCE... ARE CERTAIN WITHIN THE NEXT 12 TO 24 HOURS. ONCE TROPICAL STORM AND HURRICANE FORCE WINDS ONSET...DO NOT VENTURE OUTSIDE!

OPPOSITE: Northbound traffic on I-55 uses both sides of the interstate south of Brookhaven, Miss., on Aug. 28, 2005. State officials enabled all lanes to move in the same direction so that south Mississippi and Louisiana residents could head to safer areas before Hurricane Katrina. CHRIS TODD / MISSISSIPPI CLARION LEDGER

LEFT: USA TODAY’s front page on Aug. 29, 2005.

New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast are scarred, but have recovered

OPPOSITE: Twenty years after the flooding of New Orleans, the city has climbed from an all-time low of 3.7 million visitors in 2006 to 19 million in 2024. JACK GRUBER / USA TODAY

BY RICK JERVIS, USA TODAY

Louis Armstrong International Airport recently, I was quickly reminded just how radically this city has changed in the two decades since Hurricane Katrina.

Stepping off the plane, a gleaming $1.3 billion terminal beckoned with Creole offerings from Leah’s Kitchen and Café Du Monde. There’s a stunning two-story cypress swamp mural. The space shimmers with the curves and technology of a world-class facility — a far cry from the fusty older terminal.

Then I went to retrieve my rental car.

After I waited 15 minutes in a pelting rain, the shuttle bus arrived. It took 25 minutes circumnavigating the airport grounds before delivering me and other passengers to the car rental facility. Charm amid dysfunction. Though some things in New Orleans may be different, others remain stubbornly the same.

I lived in New Orleans from 2007 to 2013, reporting at the time on the

region’s rebuilding from the destruction wrought by Katrina and the failures of the federal levees. It remains one of the most special places my wife and I have ever lived — and one of the most significant stories I’ve ever covered.

One of the pressing questions early in the recovery was whether the city would retain its traditions and charm while rebuilding. Would New Orleans plaster over its unique culture — the very thing visitors travel from around the world to experience — in its rush to spend billions of dollars in federal recovery money?

As I returned to the city to report on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, that was one of the key questions I hoped to answer, specifically related to the city’s vaunted cuisine and music.

To get a sense of how the city’s food scene had evolved, I met with Dickie Brennan, a third-generation restaurateur

whose stable of eateries include some of New Orlean’s most iconic restaurants, including Bourbon House, The Commissary and Pascale’s Manale.

On a sultry late afternoon, we sat on rocking chairs on the porch of his Riverbend home watching cargo ships slowly ply down the Mississippi River. Brennan recounted his time during Katrina: how he fled to Baton Rouge after the storm but returned to the city five weeks later to reopen Bourbon House in the French Quarter.

It was one of the first eateries to open in the city after Katrina. While New Orleans sat in muddied ruins, Brennan and his crew served redfish on the half shell and wild catfish to journalists and first responders.

“We were in it,” Brennan said. “Our instinct was, ‘Let’s just get in there and do it.’”

The two decades since have presented a plethora of challenges for the city’s restaurant scene, from sagging visitor numbers to lack of infrastructure such as schools and hospitals to the coronavirus

OPPOSITE: Ben Jaffe, creative director and son of the cofounders of Preservation Hall, a French Quarter venue dedicated to preserving New Orleans’ traditional jazz music. JACK GRUBER / USA TODAY

BY SUSAN PAGE, USA TODAY

Buckles Jr. remembers Katrina — remembers at age 13 having his neighborhood swept away by the hurricane’s raging waters, a defining moment of his life that would dislodge his family for a time from its New Orleans roots.

Twenty years later, America remembers Katrina, too — remembers one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern U.S. history, raising questions that persist today about the crises of climate, the role of government and the nation’s divides by race and class.

In a USA TODAY/Ipsos Poll in 2025, 85% of Americans said they were familiar with Hurricane Katrina despite the passage of two tumultuous decades packed with competing news events, from an economic meltdown to wars abroad to a global pandemic.

“The images are just burned into people’s minds and hearts and souls about what those days and weeks looked like with the city underwater,” said Mary Landrieu, then a Democratic senator from Louisiana, the daughter of one New Orleans mayor and the sister of another. “The thousands of people that were stranded at the Superdome — I mean, that was a catastrophe and a real failure of the local, state and federal government.”

As the hurricane approached, she and her extended family fled their summer camp on Lake Pontchartrain. Hours later, “it was destroyed,” she said. “There wasn’t a stick or a stone left.”

The most intense memories are understandably in the South, where scars from the storm’s battering can still sometimes be seen.

But the imprint of Katrina also remains remarkably wide across the country,

recalled by nearly 9 of 10 in the Northeast and more than 8 in 10 in the Midwest and the West.

Even among those now 18 to 34 years old — no more than teenagers when the storm struck, and some not even yet born — three-quarters say they know at least a little and sometimes a lot about the tropical cyclone that in August 2005 left devastation in its wake across Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

Nearly everyone surveyed said the storm had a negative impact on New Orleans; 3 of 4 described the harm it did as significant.

Hurricane Katrina is believed to have killed 1,392 people — the deadliest hurricane since the Okeechobee hurricane in 1928 — and to have caused an estimated $200 billion in damage, when adjusted for inflation, one of the costliest storms to ever hit the United States.

OPPOSITE: Leeland Martin pulls his brother, Milton Martin, to the Superdome on an inflatable mattress on Aug. 30, 2005. JOHN ROWLAND / LAFAYETTE (LA.) DAILY ADVERTISER