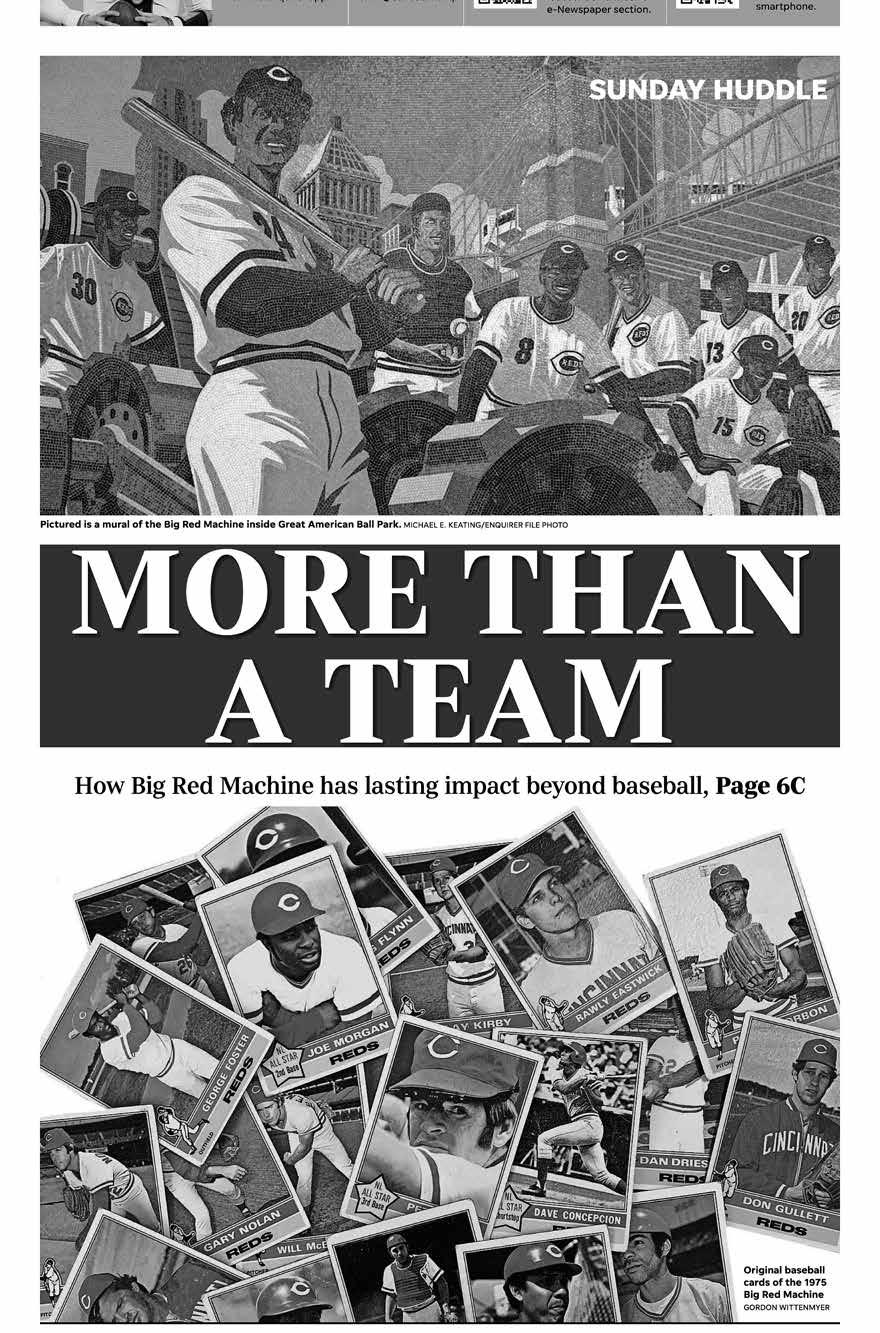

BIG RED MACHINE

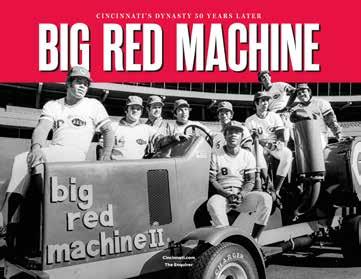

FRONT COVER: The Big Red Machine: Ken Griffey, Pete Rose, Don Gullett, Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, George Foster, César Gerónimo, Davey Concepción and Tony Pérez. FRED STRAUB / THE ENQUIRER

BACK COVER: LIZ DUFOUR, FRED STRAUB, MARK TREITEL, DICK SWAIM / THE ENQUIRER; MALCOLM EMMONS / IMAGN IMAGES

Copyright © 2025 by The Enquirer All Rights Reserved • ISBN: 978-1-63846-161-6

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner or the publisher.

Published by Pediment Publishing, a division of The Pediment Group, Inc. • www.pediment.com Printed in Canada.

This book is an unofficial account of the Big Red Machine by The Enquirer and is not endorsed by Major League Baseball or the Cincinnati Reds.

Credits

A product of The Enquirer

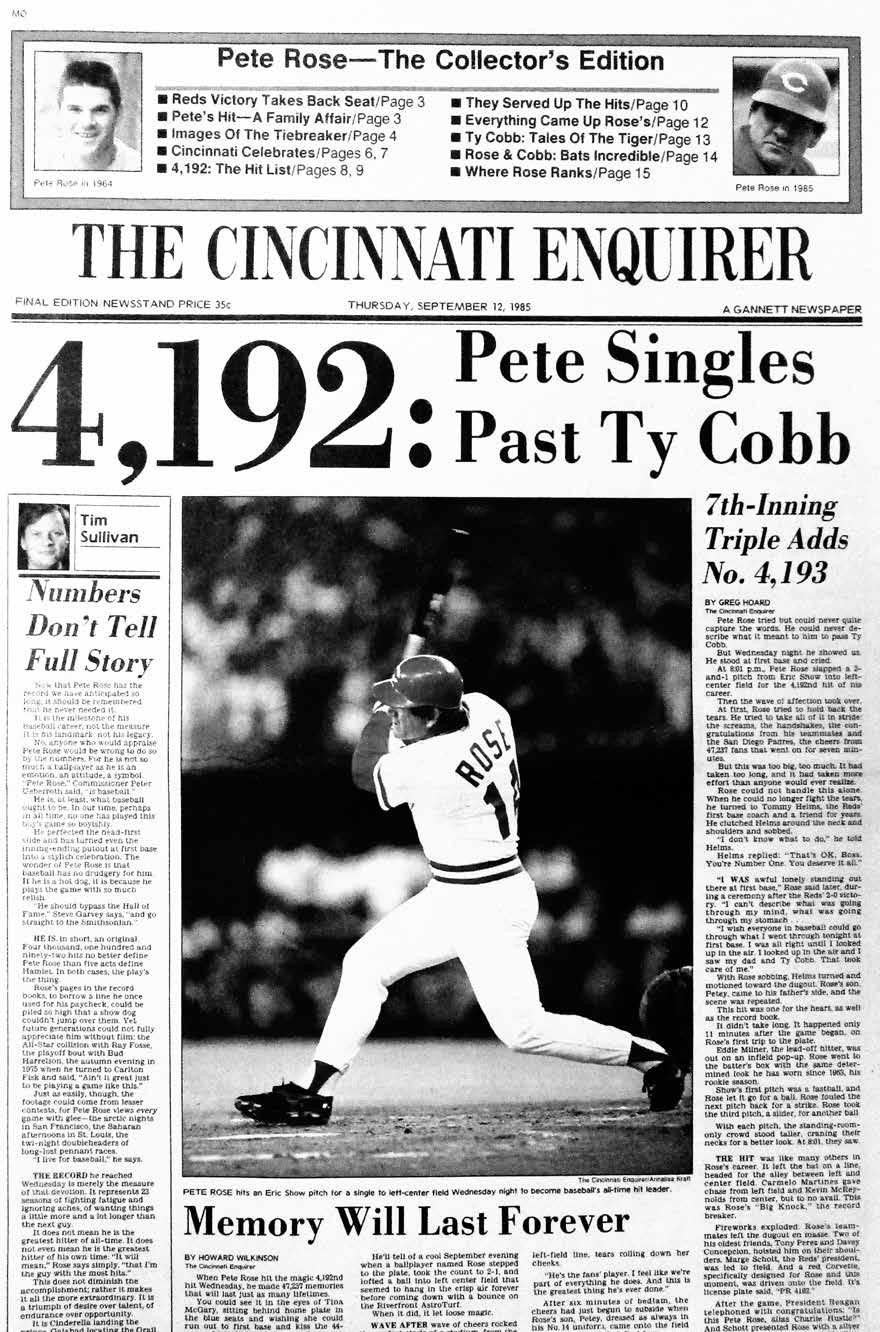

This book contains articles previously published in The Cincinnati Enquirer and the book Pete Rose: 4,192 published by The Enquirer. The text has been edited for style, clarity and length. Special thanks to Beryl Love, Jason Hoffman, USA Today, Gannett, the Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library, the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame and Museum, Pediment Publishing, Jerry Dowling, Chris Eckes, Chris Fenison, Gene Myers, Mike Nyerges, Cliff Radel, Greg Rhodes, Dashiell Suess, Kristin Suess, Jason Williams, Scott Winfield, Gordon Wittenmyer, David Wysong and The Enquirer ’s reporters, photographers, artists, editors and librarians.

Editor JEFF SUESS

Sports Editor JASON HOFFMAN

Executive Editor BERYL LOVE

OPPOSITE: Sparky Anderson speaks with umpire Satch Davidson as Johnny Bench looks on, 1976. DICK SWAIM / THE ENQUIRER

50 Years 50 Years

‘We Captured the Imagination’

BY GORDON WITTENMYER • THE CINCINNATI ENQUIRER • JUNE 29, 2025

George Foster tensed when he heard the strange voice, and braced for the worst.

“You ruined my life,” the man said.

Foster had his head down, putting baseballs and 8-by-10 photos on a table where he and other former baseball stars prepared for an autograph-signing fundraiser during a spring training game in Arizona a few years ago.

“I thought, ‘I better move back and remember my karate moves. Did I beat this guy up or something?’” said Foster, who learned hand-to-hand combat from his brother, an instructor in the military. No, the man said. “You beat my Dodgers.”

“Oh, that.” That.

The Big Red Machine.

They still remember. They’ll probably never forget. No matter where they grew up watching baseball.

And 50 years later, as nearly all of the surviving members from that iconic team conclude a weekend-long celebration at Great American Ball Park, their legacy remains as unique and intact for its cultural impact on a sport and a city as it does for

its staying power.

Never mind the historic dominance of perhaps the greatest lineup ever assembled.

“We captured the imagination,” said Johnny Bench, the Hall of Fame catcher.

Bench recalled the last Big Red Machine reunion just a few years ago.

“You had grandfathers bringing the fathers and the fathers bringing the kids,” he said. “So, you had three generations of people coming to the park. And the people that lived our past, they were crying. Because it took them to their childhood and their memories.

“You saw the tears. You saw what it meant to so many people,” Bench said. “We listen to music and we listen to the golden oldies. I guess we were the golden oldies in that way.”

Classic. Harmonic. Hit parade of all hit parades.

The Big Red Machine that dominated much of 1970s baseball certainly hits all of those golden-oldies notes.

But its legacy reaches far beyond that, then and now, for a unique confluence of time and place. Opportunity and vision. Sports and mainstream celebrity.

Big Red Machine legacy rivals any in MLB history

General manager Bob Howsam put his roster together in the last era of true dynasties, the back-to-back championships of 1975 and ’76 coming in the final two seasons before free agency.

They won their division five times from 1970 to 1976, finished second with 98 wins once, played in four World Series in that span, and had four players win six NL MVP awards from ’70 to ’77 (with 14 top-5 finishes overall in that stretch).

And they did it in the place where baseball’s professional roots run deepest, the only place that hosts an Opening Day parade for its baseball team and considers that day a city holiday.

“It’s an amazing story. It’s an amazing team,” Bench said. “I mean, it’s just, like, wow, why can’t you make a story out of the greatness of our team? And if we don’t pass somebody’s muster test, that’s fine. That’s what opinions are for.”

The greatness of the Big Red Machine tells only a fraction of the story of why its legacy resonates with Reds fans, rival fans and even non-fans five decades later.

OPPOSITE: Members of the Big Red Machine were honored at a 50th anniversary reception at the Aronoff Center for the Arts, 2025. OTTO RABE / THE ENQUIRER

Y BIG RED

50th ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIG RED MACHINE LEGA

“It doesn’t just resonate with people that are fans of baseball. It resonates with big leaguers,” said Reds broadcaster Jeff Brantley, the former All-Star closer who led the league with 44 saves for the 1996 Reds. “That’s a whole different kind of resonate.”

It’s a legacy amplified by the all-time

scandal that followed the all-time greatness of that team: the 36-year saga of hometown hero Pete Rose’s lifetime ban from baseball for gambling on baseball and his posthumous reinstatement last month.

It’s a legacy that includes an all-time actual MLB legacy in Ken Griffey Jr.

growing up in the Riverfront Stadium shadows of that team with his brother, Craig, and All-Star dad, and then growing into an inner-circle Hall of Fame center fielder.

It’s a legacy that 50 years later rivals any team in MLB history, any sports story in local history, and any cultural

phenomenon in the region since Skyline Chili or the Roebling Bridge. The names Johnny Bench and Pete Rose became so ubiquitous in the national baseball scene that they transcended sports into mainstream American consciousness the way Joe Namath and Willie Mays did before them.

Lasting cultural impact transcends baseball

In Cincinnati, few names in or out of sports carry the same weight all these years later.

“I would say Joe Burrow is probably there,” said Reds reliever Brent Suter, a Moeller High School grad whose grandfather was a police officer in Blue Ash. “Sarah Jessica Parker, Carmen Electra maybe, just in terms of notoriety. They’re right up there with the biggest celebrities.” Johnny Bench. Carmen Electra. Pete Rose. Sarah Jessica Parker. Joe Morgan, Joe Burrow. Tony Pérez, Jerry Springer, George Foster, Dave Concepción, Doris Day, Sparky Anderson, Steven Spielberg. It was baseball culture that spilled into popular culture.

It was impact.

“Impact on a city, impact on the game of baseball,” Suter said. “Not to mention Ken Griffey Sr., who was a great player in his own right and had a son who’s maybe the best center fielder of all time.” Legacy.

The Big Red Machine is still the last National League team to win back-to-back World Series, with the Dodgers spending more than $300 million on payroll this year to try to end that reign.

Those Reds had three Hall of Fame players, a Hall of Fame manager, baseball’s Hit King (who may one day join the others in the Hall), four league MVPs, seven All-Stars in their eight-man lineup and five guys with a combined 26 Gold Gloves. Their heavyweight greatness in their moment was undisputed.

“There were so many different ways that we could beat you,” George Foster said. “With our legs, with our gloves, with

our bats, with our speed. Whatever you needed we had on that team. Whatever you needed to be done, we had a guy that could do it.”

Bench said they drew big crowds just for the magnitude of batting practice. They were baseball rock stars wherever went.

“We were intimidating,” Foster said. “We’d go to Dodger Stadium and fans

would talk, and then they’d see us come out for (batting practice), and it was like EF Hutton. Everybody listens. We go out there, and it would get quiet.”

Until they started taking BP.

“I remember in San Diego, Gaylord Perry told his pitchers not to watch us take batting practice,” Foster said. “We noticed them watching so we started launching.

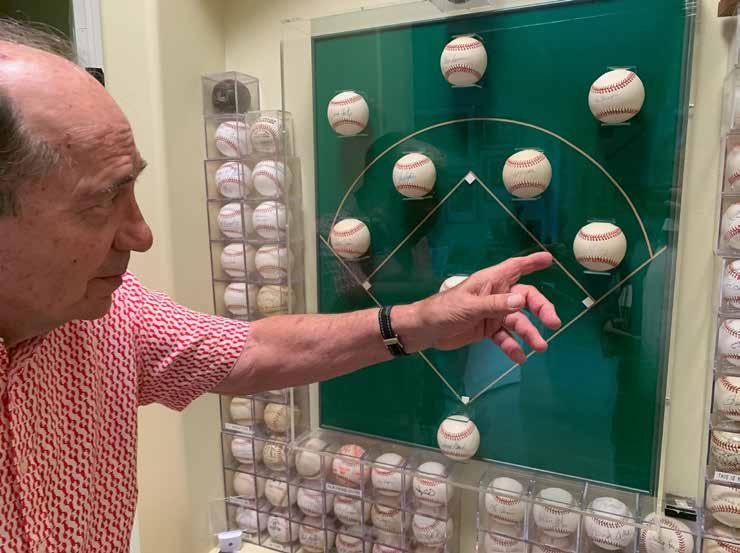

ABOVE: Reds legend Johnny Bench points to the faded autograph of Big Red Machine teammate Tony Pérez on the display of autographed balls from his teammates he keeps in his Florida home.

GORDON WITTENMYER / THE ENQUIRER

Rose. Bench. Morgan. So now the pitchers were intimidated.”

Yes, that Gaylord Perry. The two-time Cy Young winner and Hall of Fame spitballer. The veteran who in 1971 helped precipitate Foster’s trade to Cincinnati when he confronted the young slugger for taking extra BP with the pitchers.

“Somehow my bat got underneath his chin,” Foster said. “I didn’t know how it got there.”

He was traded quickly after the incident

Just ask the other pitchers in the league. “They were a different team than every other team I ever faced,” said former Cy Young winner Steve Stone, who faced the Reds nine times from 1971 through ’76 and never beat them (0–4, 4.89 ERA). “There were certain teams that if they get up 6–0, maybe they beat you 6–2. If the Big Red Machine got up 6–0, they tried to beat you 12–0. There was never any wasted at-bats.”

Stone pitched in both leagues during his 12-year career and faced the Oakland dynasty in 1973 during its three-year run of championships and later the 1977–78 Yankees champions.

“A lot of those teams could beat you,” Stone said. “The Big Red Machine went out to humiliate you.”

With stars at every position, Stone added. “Not stars but Hall of Famers.” Who was comparable? Who might have been better?

Not the ’27 Yankees of Ruthian lore, Pérez said.

in one of the best trades in Reds history.

Or, as Foster heard it from a Giants fan who recognized him a few years ago:

“You’re the worst trade in Giants history!”

‘Big Red Machine went out to humiliate you’ They still remember.

That might be the biggest thing 50 years later. Just how deep and lasting the impression those players made was.

“We set the standard,” Bench said.

“The Yankees in those days were a great team,” Pérez said. “But in those days, you didn’t have the great defense. You needed hitters and pitching. That’s all. It’s hard to catch the ball with the gloves they used to use.”

During this recent conversation in the living room of his Miami bayside condo, Pérez gestures across the room toward the figurines of the Big Red Machine lineup that he keeps on a top shelf.

“But our team,” he said, “you go through the lineup, that one there, and you can see everything you need to win a ballgame. Anything. You had defense. Speed. Offense. Anything.

“And we had pitching. We didn’t have

pitching to win 20 games or something like that. But they were great. The bullpen was great. The starters were great.”

“Not only was that lineup relentless,” said All-Star Rick Monday, who joined the arch-rival Dodgers in 1977, “but defensively they beat you, too.”

Stone called Davey Concepción one of the most underrated players in the game, an athletic shortstop with five Gold Gloves who mastered the skip throw to first, using the hard turf at newly opened Riverfront Stadium to his advantage.

In fact, that Reds “Great Eight” lineup of Rose, Morgan, Bench, Pérez, Foster, Griffey, Concepción and César Gerónimo had higher cumulative WAR (wins above replacement), according to Baseball-Reference.com, than the 1927 Murderer’s Row Yankees of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs and Bob Meusel.

Reds were once the prototype for the best talent in sports

Anyone who wants to win a baseball trivia contest at their next sports-bro party should quiz the room on who the catcher and third baseman were on the ’27 Yankees.

(Bench’s and Rose’s counterparts were Pat Collins and Joe Dugan.)

Anybody else?

“Maybe the Dodgers teams (of the 1950s) with Duke Snider and them,” Pete Rose said last year during a long conversation with The Enquirer. “But Duke was the only left-hand hitter on that team. The rest of them were all right-handed hitters. (Pee Wee) Reese, (Carl) Furillo, (Roy) Campanella.”

Anybody else?

Sure, maybe. But consider this in any historical comparison:

Not only did the Big Red Machine rise to dominance in a post-integration, pre-steroids moment, but as a percentage of MLB players, Black American levels were at their highest in the 1970s, more than 20 percent of the league in some of those seasons (more than double today’s numbers). The percentage of Latin American players

reached double digits in the ’70s and grew steadily through the decade.

And the young adults of the 1970s were the kids of the ’50s and ’60s, when baseball was still king in American sports.

Bottom line: For the first time — and the last time, so far — the greatest athletes in the Western Hemisphere disproportionately played baseball compared to other sports.

ABOVE: George Foster and Ken Griffey Sr. laugh at a joke during the Big Red Machine anniversary reception at the Aronoff Center. OTTO RABE / THE ENQUIRER

Sparky Who?

BY BOB HERTZEL • THE CINCINNATI ENQUIRER • OCT. 10, 1969

The year was 1955 and the place Fort Worth, Texas. Until then he’d been known as George Anderson, just another ball player.

It happened one afternoon. A radio announcer, covering the game, came up with it. He called him Sparky. It was the birth of Sparky Anderson, so to speak.

“There were people listening who thought the announcer was drunk that day. They’d never heard of Sparky Anderson,” said the just-named manager of the Cincinnati Reds.

Time has gone by and the place has changed, but the same cry is going out around Cincinnati that went out in Fort Worth. Who is Sparky Anderson?

The question isn’t easy to answer. You can go into the background … 35 years old, native of Bridgewater, South Dakota, resident of Thousand Oaks, California, a minor league manager and a major league coach. But this tells nothing. This is not the person.

Darrel Chaney, the Reds’ No. 2 shortstop, played for Anderson in 1968 at Asheville. That year Anderson was working for Bob Howsam, the man who again hired him, and won the pennant.

“He’s a lot like Dave Bristol,” said Chaney. “There’s a little more hot dog in him than there was in Dave. He’s more of a pepper pot.

“But Sparky knows the game inside and out. He hates to lose, just like Dave did. Really, I picture him and Dave as the same type of person. When you do something wrong they both let you know about it.

“There was this game in Asheville. The score was 1–1 in the 15th inning. A guy hit an easy ground ball through the middle.

Frank Duffy, the shortstop, and I went after it. Duffy called for it. I stopped. Duffy thought I was still coming and stopped, too. The ball went through for the game-winning hit.

“After the game, he got us in the clubhouse,” Chaney continued. “Duffy told him it was one of those things.

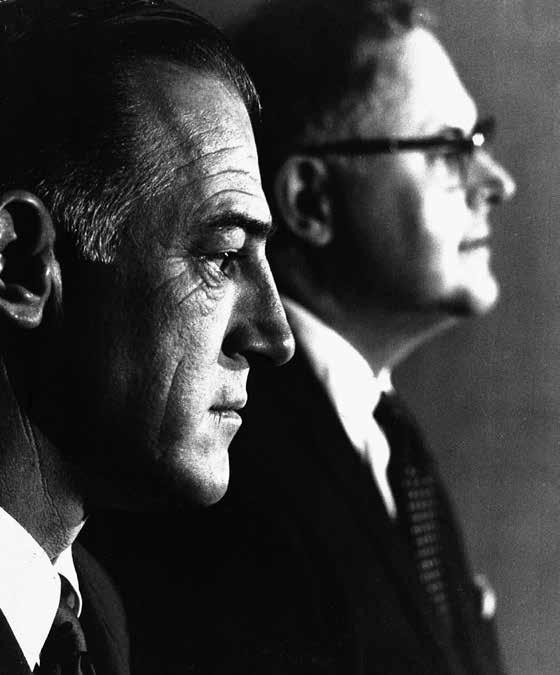

ABOVE: General manager Bob Howsam introduces Sparky Anderson as the new manager of the Cincinnati Reds.

MARK TREITEL / THE ENQUIRER

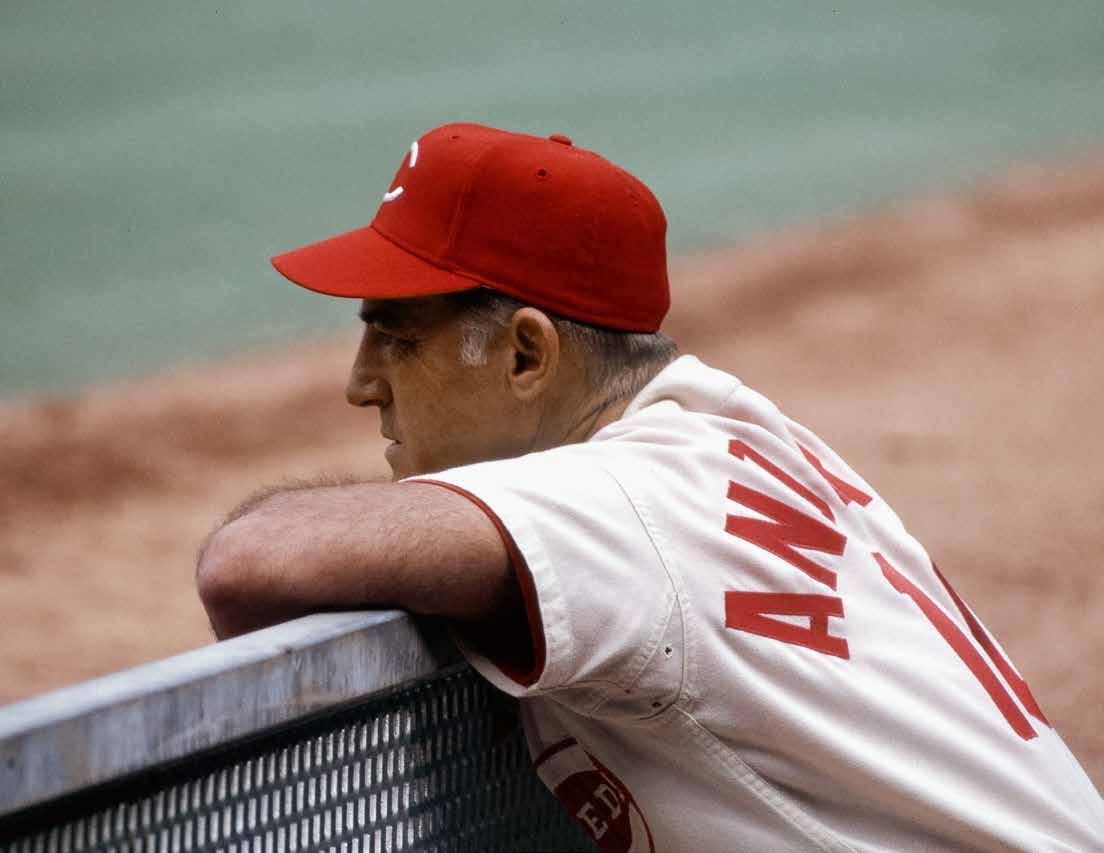

OPPOSITE: Reds manager Sparky Anderson watches from the dugout during the 1970 season at Riverfront Stadium.

MALCOLM EMMONS / IMAGN IMAGES

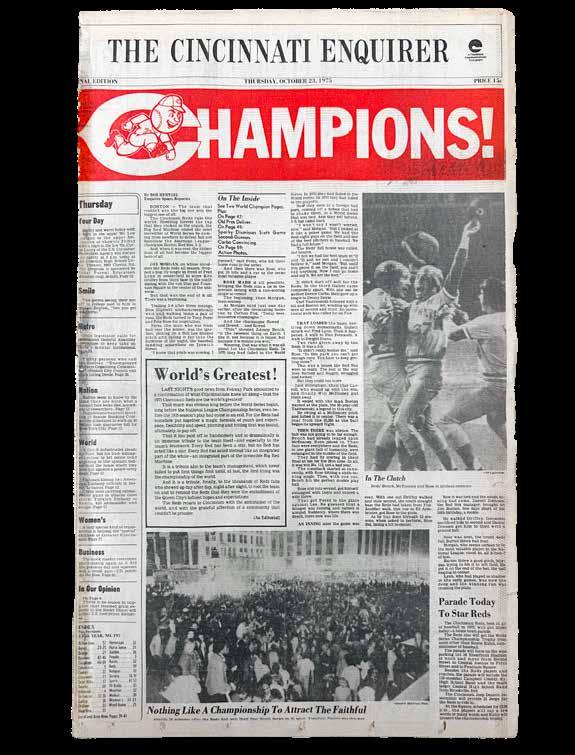

Champions!

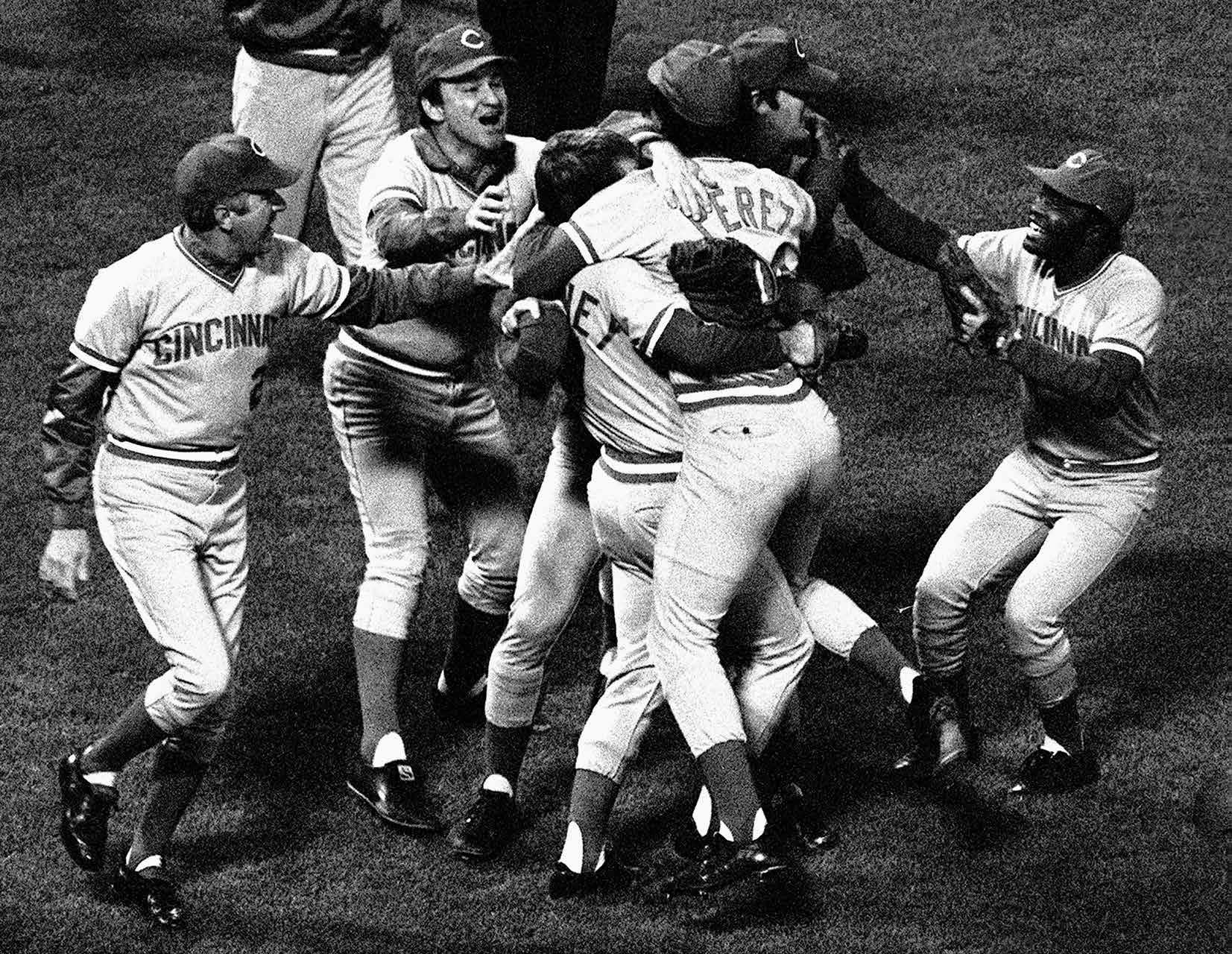

BY BOB HERTZEL • THE CINCINNATI ENQUIRER • OCT. 23, 1975

BOSTON — The team that couldn’t win the big one won the biggest one of all.

The Cincinnati Reds rule the world. Shedding forever the rap that they choked in the clutch, the Big Red Machine ended the most incredible of World Series by coming from nowhere to defeat but not humiliate the American League-champion Boston Red Sox, 4–3.

And, when it was over, the littlest man of all had become the biggest hero of all.

Joe Morgan, on whose shoulders the Reds rode all season, dropped a pop fly single in front of Fred Lynn in center field to score Ken Griffey from third base in the ninth inning with the run that put Fountain Square in the center of the universe.

But that was the end of it all. There was a beginning.

Trailing 3–0 after three innings, Don Gullett uncharacteristically wild and walking home a pair of runs, the Reds turned to Tony Pérez and Pete Rose for inspiration.

Pérez, the man who was trade bait over the winter, was the ignition, picking on a Bill Lee blooper pitch and sailing it far into the darkness of the night, the baseball

landing somewhere on Ipswich Street.

“I know that pitch was coming. I guessed,” said Pérez, who hit three home runs in the series.

And then there was Rose, who got 10 hits and a car as the series’ most valuable player.

Rose made it all possible, bringing the Reds into a tie in the seventh inning with a run-scoring single to center.

The beginning, then Morgan, then ecstasy.

As Morgan said just one day earlier, after the devastating home run by Carlton Fisk, “Today beer, tomorrow champagne.”

And the champagne flowed … and flowed … and flowed.

“This,” shouted Johnny Bench, “is the sweetest thing on Earth. I like it, not because it is liquor, but because it means you won.”

Winning, that was what it was all about for the Cincinnati Reds. In 1970, they had failed in the World Series. In 1972, they had failed in the World Series. In 1973, they had failed in the playoffs.

Now they were in a foreign ballpark, coming off a defeat that had to shake

them, in a World Series that was tied. And they fell behind, 3–0, but came back.

“I won’t say I wasn’t worried, now,” said Morgan. “But I looked at it like a poker game. We had the best eight guys on the field and one of the best pitchers in baseball. We had a full house.”

The Reds’ full house was called, not beaten.

“I felt we had the best team in ’72 and ’73 and we lost and I couldn’t believe it,” said Morgan. “But until you prove it on the field, you can’t say anything. Now I can go home and say it. We are the best.”

It didn’t start off well for the Reds. In the third, Gullett came completely apart. With one out he walked Bernie Carbo, then gave up a single to Denny Doyle. Carl Yastrzemski followed with a hit and Boston led, winding up with men at second and third. An intentional walk was called for on Fisk.

That loaded the bases. Settling down momentarily, Gullett struck out Fred Lynn. Then it happened. A walk to Rico Petrocelli. A walk to Dwight Evans.

Two runs given away by the Reds. It was a 3–0.