ON THE COVER

FRONT COVER: (Front row, from left) Boxcar Willie, DeFord Bailey, Ronnie Milsap, Johnny Cash, Lester Flatt, Jimmy Dickens, Trace Adkins, Blake Shelton; (second row, from left) Bill Anderson, Jeannie Seely, Minnie Pearl, Loretta Lynn, Martina McBride, Earl Scruggs, Dolly Parton; (third row, from left) Dierks Bentley, Del McCoury, Carrie Underwood, Hank Williams Sr., Charley Pride, Darius Rucker; (back row, from left) Grandpa Jones, Alison Kraus, Jesse McReynolds, Jim McReynolds, Vince Gill, Trisha Yearwood, Bobby Bare, Eddie Montgomery, Charlie Daniels, Troy Gentry, Roy Acuff, Reba McEntire, Kimberly Schlapman, Kelsea Ballerini.

BACK COVER: The attending Grand Ole Opry cast members crowded the stage to sing “I Will Always Love You” in a tribute to Dolly Parton at NBC’s “Opry 100: A Live Celebration” event at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville on March 19, 2025. NICOLE HESTER / THE TENNESSEAN

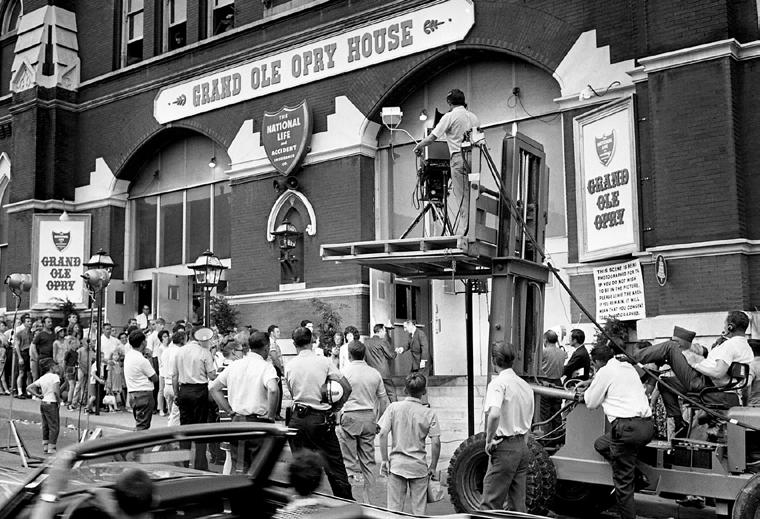

RIGHT: A Great American Country camera operator monitors the Grand Ole Opry show for cable on Oct. 11, 2003. A one-hour televised portion called “Opry Live” airs on GAC on Saturdays and Tuesdays, with four rebroadcasts during the week. JOHN PARTIPILO / THE TENNESSEAN

Copyright © 2025 by The Tennesean All Rights Reserved • ISBN: 978-1-63846-159-3

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner or the publisher.

Published by Pediment Publishing, a division of The Pediment Group, Inc. • www.pediment.com Printed in Canada.

This book is an unofficial account of Grand Ole Opry history by The Tennessean, and is not endorsed by the Grand Ole Opry.

TIMELINE

Marcus

KELSEA BALLERINI

FOREWORD

IT’S A DISTINCT AND RARE

full circle (pun intended) to have been a young fan in the pews, to a girl on a guided backstage tour, to stepping onto that stage for the first time as a performer, and now a member of the Grand Ole Opry.

Some would call the Opry a religious experience, a prestigious platform, the epicenter of country music. And yes, those are all inarguable. But to me, it’s the goosebumps you get as you walk in the front doors from the ghosts of our heroes that usher us in. It’s the boot marks and heel scratches etched onto the oak stage that remind us of the songs that soundtrack our highest highs and lowest lows. It’s the warmth of the amber

lights lining the dressing room hallway, with legends and newcomers alike tuning their guitars and singing harmonies from a room over. It’s the grandfather in a weathered Stetson bringing his granddaughter in a glittery dress in the third row, and having stories and songs for them both night after night after night.

The Opry holds the heartbeat that homages country music’s musical history, while eagerly opening its arms to what’s to come. It will forever be one of the highest honors of my life to help the circle stay unbroken.

FACT

The Grand Ole Opry began as the WSM Barn Dance in 1925 and is now the longest-running radio broadcast in history.

THE EARLY DAYS

HOW AN INSURANCE COMPANY’S RADIO SHOW CHANGED NASHVILLE’S TRAJECTORY FOREVER

BRYAN WEST • THE TENNESSEAN

IN 1925, THE TALK OF THE town was the dazzling new WSM radio station, on the fifth floor of the National Life and Accident Insurance Co. building in downtown Nashville.

The Tennessean headline from Oct. 4 read “Station WSM ‘goes on air’ Monday night.” Reporter William S. Howland detailed the studio — state of the art for the time — capturing the admiration of politicians, business leaders and the community.

“With every wire adjusted and every connection made, WSM now stands

ready in every respect to send the name of Nashville hurtling through the ether Monday night to the far corners of the American continent,” Howland wrote.

The insurance building stood at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Union Street. From 7 p.m. Oct. 5, 1925, until 2 a.m. the following morning, the inaugural program was transmitted from two 165-foot towers. Tennessee households tuned in with great anticipation. At that time, only WSB in Atlanta rivaled WSM in equipment quality.

“In short, any radio enthusiast who cannot find something to please him or her on WSM’s inaugural program might just as well give up the ghost and

pass on to another world, because he or she has gone beyond the scope of this world’s pleasures and entertainment,” Howland wrote.

One hundred years later, Dan Rogers sat in his office just a few feet from the stage of WSM’s legendary program the Grand Ole Opry. The show’s executive producer is steering the ship into its next century.

“I really believe if you could bring Uncle Jimmy Thompson — who was the first person to sit down and play his fiddle on the stage — to an Opry show today, he’d be flabbergasted by what he saw and heard,” Rogers said.

WSM radio launched what would

OPPOSITE: Hank Snow plays with his band at the Ryman Auditorium for the Grand Ole Opry show Feb. 7, 1953. DON CRAVENS / THE TENNESSEAN

FACT

The “Grand Ole Opry” was coined by radio announcer George D. Hay in November 1927.

become a century-long institution — one that would draw visitors from around the world to Nashville.

“There wouldn’t be an Opry without Nashville,” Rogers said. “And Nashville truly would not be the city it is today without the Opry.”

‘We Shield Millions’

Months before the first broadcast, National Life Vice President Edwin W. Craig acquired the call letters WSM, which soon came to stand for the company’s slogan:

“We Shield Millions.”

Craig had a vision: to elevate himself, his company and Nashville to national prominence. In the summer of 1925, while attending a broadcasting convention, he ran into George D. Hay — a charismatic and respected announcer known for his work on Chicago’s WLS National Barn Dance. Hay was intrigued by Craig’s vision and agreed to join him, arriving in Nashville just in time to launch the station’s first major program on Nov. 9 — his 30th birthday.

“In the 1920s, almost every radio station

across the country had some kind of barn dance program, especially in the South,” said Grand Ole Opry historian Byron Fay. “There were no records to play on air, so everything had to be performed live.”

Hay began assembling talent for the Saturday night broadcast. One of WSM’s pianists, Eva Thompson Jones, suggested her uncle, a fiddler named Uncle Jimmy Thompson who had earned acclaim in Texas for his performances. Hay invited Thompson to perform live on Nov. 28, 1925. His old-time fiddle tunes lit up

FACT

By 1933, fan mail totaled more than 30,000 letters in just three days, addressed to the Grand Ole Opry.

the airwaves, and enthusiastic listeners flooded the station with calls of approval.

That night’s success prompted Hay to bring in more local musicians, and his theatrical announcing became part of the appeal. He introduced each program with an imitation steamboat whistle and leaned into Southern charm. The show quickly gained traction.

By the end of the year, The Tennessean listed the lineup for the “WSM Barn Dance,” including Thompson and Jones.

“That was the start of the Opry,” Fay

said. “Hay added acts, all of them local and rural. No professionals, so to speak.

People started coming to watch from the hallways.”

Among the earliest additions to the WSM Barn Dance were Uncle Dave Macon, Sid Harkreader and Dr. Humphrey Bate. Macon, a banjo-playing showman, quickly became a crowd favorite with his infectious energy and vaudeville flair. Harkreader, a skilled fiddler, matched Macon’s charisma, while Bate showed off his harmonica skills. He had already performed on Nashville’s

first radio station, WDAD, and was likely the first country artist to play on WSM.

By the fall of 1926, the Barn Dance had gained enough popularity to take the show on the road. The cast performed live from the Tennessee State Fair, broadcasting from a glass-fronted stage where thousands watched Thompson, Bate, Obed Pickard and DeFord Bailey perform in person.

As the one-year anniversary of the show approached, National Life upgraded WSM’s broadcasting power to 5,000 watts. The transition required a temporary shutdown,

RULES & TRADITIONS

A GUIDE TO OPRY TRADITIONS, FROM OPEN DOORS TO UNBROKEN CIRCLES

MARCUS DOWLING • THE TENNESSEAN

AS WITH MOST LONG -

standing institutions, the Grand Ole Opry has an unwritten set of revered traditions and regulations. Here are a few of the most significant.

Why do Opry performers keep their dressing room doors open?

The Opry’s 1974 move from the Ryman Auditorium to the Grand Ole Opry House came with the addition of numerous dressing rooms. In 2025, the number stood at 18. If you visit backstage, room No. 1 honors the friendly legacy of former Opry host and country star Roy Acuff.

“My dressing room door is always open,” the “Wabash Cannonball” vocalist told The Oklahoman in a 1988 interview while hosting an impromptu jam session with his band.

Acuff also held court with friends, family, fans and fellow performers there. The reason? The sizable space located close to the stage could create once-ina-lifetime experiences. Want to meet or get into a guitar pull with a star you’re eyeing as a collaborator or who serves as a key inspiration? Head to Acuff’s dressing room.

Now, the trend has expanded past Mr. Roy’s door. Head backstage at the Opry on most any night and whether it’s an emerging act making their debut and

sitting in room No. 4, a bluegrass band preparing to hit the stage, a female star in the “Women of Country” dressing room or even Marty Stuart in room No. 18 — which shares its rhinestone-suited motif with another former Opry host, “Wagonmaster” Porter Wagoner — a welcoming open door’ll usually greet you.

What is the significance of the onstage circle at the Grand Ole Opry?

After calling the Ryman Auditorium home for decades, the Opry took a piece of it along when the show moved to the Grand Ole Opry House in 1974. An eightfoot square was cut from the Ryman stage and fashioned into a six-foot circle,

which was laid into the center of the new Opry stage.

The Opry’s website says it “bears the scuffs and marks of the decades of performers who’ve performed there and still brings some old country magic to the Opry every night.”

In May 2010, a flood devastated much of

Nashville, including the Grand Ole Opry, where the front-of-house and backstage areas were submerged under several feet of water. Though the backstage was destroyed and later renovated, the circle at the front of the Opry stage escaped relatively unscathed.

“(The circle) is in remarkably good

condition. We’ve taken it up and are taking it out for some TLC so that it will be fine,” then-Grand Ole Opry president Steve Buchanan said. “We have it sequestered for special attention, and then it will be back in place. We will ultimately need to replace the stage, but we do that every few years. But the circle will be saved.”

After undergoing $20 million in renovations, the Opry House fully reopened in October 2010.

“I’ve always said the circle still contains the dust from Hank Williams’ cowboy boots,” said Brad Paisley before the Opry House reopened its doors. “Now it contains that dust but also the heart and soul of this

town and all the people who have worked to rise above.”

Depending on the Opry’s production schedule, most Grand Ole Opry House tours include a chance to stand on the stage and step into the six-foot wood circle.

How

many times

per year are

Grand Ole Opry members required to perform?

Over its 100-year history, the number of times members inducted into the Opry cast are required to perform has dropped from a minimum of every other week to an average of once per month.

OPRY LEGENDS WHO ARE THE GIANTS OF THE GRAND OLE OPRY?

AUDREY GIBBS • THE TENNESSEAN

OVER THE PAST CENTURY OF THE GRAND OLE OPRY, ITS MEMBERS are the ones who’ve helped the show and venue ascend to its legendary status.

We’re here to walk you through some of the early giants of the Grand Ole Opry, from Minnie Pearl to “Whisperin’” Bill Anderson.

Here’s what to know about the performers who shaped the Opry.

OPPOSITE: A star studded lineup of Opry performers open the 40th anniversary celebration for the Grand Ole Opry House on March 15, 2014, by singing “The Wabash Cannonball” the same as Roy Acuff did 40 years before at the first Opry held at the new Opry House. LARRY MCCORMACK / THE TENNESSEAN

DEFORD BAILEY

HARMONICA PLAYER

DeFord Bailey is considered by many to have been the first African American country music star.

Born in Smith County, Tennessee, in 1899, Bailey was raised in a family that championed “Black hillbilly music,” he said. He’s best known for his songs “Pan American Blues,” “Muscle Shoals Blues” and “Fox Chase.”

DeFord made his Opry debut only months

after the show launched, and by June 1926, Bailey was regularly appearing on the Grand Ole Opry stage.

He was christened “The Harmonica Wizard” and made appearances alongside Uncle Dave Macon, Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe between 1926 and 1941. That year, the Opry fired Bailey due to a licensing dispute.

Bailey died in 1982 due to kidney and heart failure. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame posthumously in 2005.

ABOVE: Veteran harmonica player DeFord Bailey performs on Dec. 14, 1974, with “It Ain’t Gonna Rain No More,” “The Pan American Blues” and “Fox Chase.” Bailey, who first performed on the Opry a month after its debut in 1925, left it in 1941. DALE ERNSBERGER / THE TENNESSEAN

Roy Acuff, right, welcomes veteran harmonica player DeFord Bailey to the new Grand Ole Opry House on Bailey’s 75th birthday on Dec. 14, 1974. Bailey, whose first appearance on the Opry was in 1925, was making his debut in the new home of the Orpy. DALE ERNSBERGER / THE TENNESSEAN

on as

MINNIE PEARL

MINNIE PEARL — THE stage name Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon — was born in 1912 in Centerville, Tennessee

Cannon joined the Opry cast in 1940 after radio execs saw her perform at a banker’s convention, and would go on to perform on the stage for 50 more years.

Cannon’s country persona Minnie Pearl, a flirty small-town woman in a knee-length dress and straw hat who gossips about her neighbors in her fictional town, became a fixture of the show. Pearl came to be known

as the queen of country comedy, garnering acclaim for songs “Giddyup Go Answer” and “The Old Maids Of Grinder’s Switch,” and her trademark phrase “How-DEE!”

After undergoing treatment for breast cancer, Cannon became a notable advocate for cancer research and patient care. In 1993, a group of physicians established the Sarah Cannon Cancer Network in Nashville in her name. It has become a global network of cancer programs under HCA Healthcare, advancing cancer care in the U.S. and U.K.

In 1996, Cannon died due to complications of a stroke at 83 years old in Nashville.

the crowd during the Grand Ole Opry 43rd birthday party show at the Ryman

Oct. 19,

NASHVILLE IMPACT

‘NURTURED BY THE OPRY’: ICONIC RADIO SHOW MADE NASHVILLE WHAT IT IS TODAY

MELONEE HURT • THE TENNESSEAN

BEFORE NASHVILLE HAD bachelorettes, pedal taverns, rooftop swimming pools and a dozen honky-tonks named after country music superstars like Morgan Wallen, Jason Aldean and Lainey Wilson, the city was home to something truly original.

In 1925, a live barn dance-turned radio show started delivering country music into households every Saturday night. It became known as the Grand Ole Opry.

One hundred years later, that radio

show is still going strong and has evolved into nightly performances in its own namesake building in Nashville’s Donelson neighborhood. Artists clamor to stand in its sacred circle, and visitors buy tickets to witness it when they do. The Opry has not only formed the careers of almost every country music performer today, but it has shaped the city that birthed it. It created jobs. It established country music’s hometown. It gave Nashville a brand.

And as the Grand Ole Opry grew to international fame, it took Nashville along with it.

Gordon Kerr, president and CEO of

Black River Entertainment in Nashville, said the Opry has had a major impact on his company and the artists it represents, who include Kelsea Ballerini, Scotty Hasting, Chris Young and MaRynn Taylor.

“The Opry has played a significant role in our business and also in our artists’ development and their ability to celebrate milestones along their way,” he said. “I remember the night Kelsea got invited to be a member, and that was just a very special moment. “

However, Dr. Don Cusic, professor of music industry history and music business at Belmont University, said the

OPPOSITE: With a sold-out audience, the stage comes alive for the Grand Ole Opry show March 3, 1979, during the Public Television Broadcast nationwide telecast for only the second time in the 53-year history of the Opry. The telecast was on the air for six hours and Nashville’s WDCN public station was the host for the show. ROBERT JOHNSON / THE TENNESSEAN

ABOVE LEFT AND MIDDLE: Minnie Pearl and Dolly Parton perform in a packed Grand Ole Opry Spectacular as the Opry celebrates its 50th birthday, Oct. 18, 1975. The event closed a full week of country music activities and was broadcast live over WSM radio.

JIMMY ELLIS / THE TENNESSEAN

ABOVE RIGHT: Grandpa Jones, the newest member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, finishes his number during the Grand Ole Opry Spectacular, Oct. 18, 1978. FRANK EMPSON / THE TENNESSEAN

effects of the Grand Ole Opry on Nashville stretch far beyond the music industry.

“We have an NFL team,” Cusic said, which he attributed as indirectly because of the Opry. “We have a hockey team and a soccer team. That growth comes to a large extent from the Opry and the music industry. We would not be on the short list for a major league baseball team if we didn’t have that long history nurtured by the Opry.”

Opry’s inspiration is legendary

A young Virginia native remembers visiting the Grand Ole Opry at 6 years old

to see country legend Minnie Pearl. He raved about the performance the whole ride home. That young man was Ketch Secor of Old Crow Medicine Show. At 18, he returned to Nashville and performed on street corners, eventually landing an Opry membership himself.

The Opry’s back hallways and dressing rooms are lined with faces who have similar stories about how the Opry inspired them to pursue country music.

The Opry’s reach became clear to Cusic on an international trip several years back.

“ I was in India once,” he said. “I talk and someone said, ‘Where are you from?’ I say

‘Nashville, Tennessee,’ and they immediately respond with, ‘Oh, the Grand Ole Opry!’ I’ve made a lot of trips to England as well, and it’s just common knowledge there.”

The Opry provided early Nashville with an icon. It became to Nashville what Broadway is to New York City or Hollywood to Los Angeles.

“There are three recording centers in the United States: New York, L.A. and Nashville,” Cusic said. “The reason we’re in that three is because of the Opry directly and indirectly. It created a creative class here.” CONTINUED ON PAGE 148