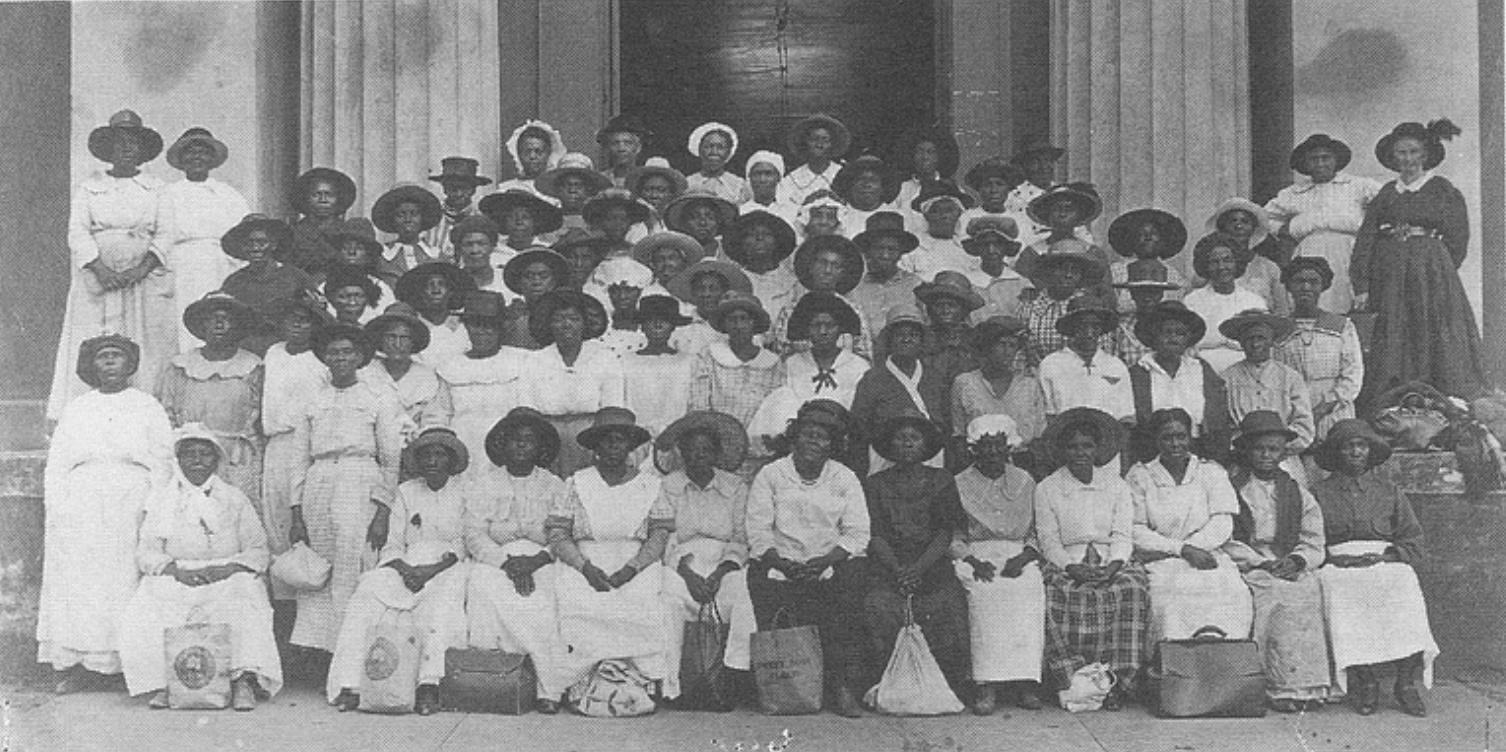

The Numbers: The Black Maternal Mortality Crisis

The U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate vs. the U.S. Black Maternal Mortality Rate per 100,000 Births (2019-2021)

Source: Hoyert D L (2022) Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States 2020 National Center for Health Statistics https://www cdc gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/E-stat-Maternal-Mortality-Rates-2022 pdf; Harris, E (2023) US Maternal Mortality Continues to Worsen JAMA, 329(15), 1248 https://doi org/101001/jama 2023 5254

In 2019, the U S ’s maternal mortality rate was 201 per 100,000 births For Black women specifically, this number was 44 per 100,000 births The total U S maternal mortality rate continued to grow in 2020 with 23 8 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, as did this racial inequity wherein 55 3 Black maternal deaths per 100,000 births were observed – the highest among any other racial group (Hoyert, 2022)

These rates, like many other health inequities, were exacerbated after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic The total U S maternal mortality rate increased to 32 9 per 100,000 births in 2021 while the Black maternal mortality rate grew to 69 9 per 100,000 births (Hoyert, 2022; Harris, 2023)

In each year between 1999-2019, research found that the Black population had the highest median state maternal mortality rate In addition to Southern states, Black maternal mortality ratios were the highest in

Source: Fleszar, L G , Bryant, A S , Johnson, C O , Blacker, B F , Aravkin, A , Baumann, M , Dwyer-Lindgren, L , Kelly, Y O , Maass, K , Zheng, P , & Roth, G A (2023) Trends in State-

Nonmedically Indicated C-Section Births

Global C-Section Rate by Percent

Source: Angolile, C M , Max, B L , Mushemba, J , & Mashauri, H L (2023) Global

: A call to

Although medically indicated Cesarean section (CS) is evidenced to save the lives of birthing people and their babies, overuse of the surgery is a threat to the health of both the birthing person and their baby Overuse of the surgical procedure has significantly increased in the past 30 years, mostly due to nonmedically indicated use in middle- and high-income countries (Boerma et al , 2018) From 1990 to today, the global CS rate has grown from 7% to 21% – a rate that is expected to reach 29% by 2030, well surpassing the World Health Organization’s acceptable CS rate of 10-15% Nonmedically indicated CS can expose the mother and baby to various health complications including non-communicable diseases and immune conditions (Angolile et al., 2023).

Some contributors to increased overuse of CS include:

increased maternal request due to anxiety or fear of vaginal use and/or the desire to give birth on a specific date; physicians’ preference of convenience; and financial incentives for physicians and hospitals (Angolile et al , 2023)

Global and regional increases in CS use were associated with an increasing proportion of

b

ri t s occurring within health facilities, accountingfor 65% ofthe global

increase. Drivers of within-country increases in CS use included high CS use among low obstetric risk births, especially among more educated women and wealthier women (Boerma etal., 218).

RacialInequitiesinNonmedicallyIndicated CSUse

Additionally, a 2022 study identified racial disparities in nonmedically indicated CS use, revealing that lowrisk nulliparous Black and Hispanic women and birthing people undergo CS more frequentlythan their white counterparts, contributing to excess maternal mortality (Debbink et al., 2022).

Research Process: Highlights

The Literature

The research process for this project first began with an extensive review of the literature on topics such as the Black maternal mortality crisis, obstetric racism, the history of Black traditional midwifery, racial concordant care, and statistics on midwifery versus physician care

Interviews

Next, two interviews were conducted with the following individuals:

A Columbia University nursing-midwifery student

An obstetrician in leadership at a NYC Health & Hospitals facility that has achieved one of the lowest CS rates in the city

Workshop

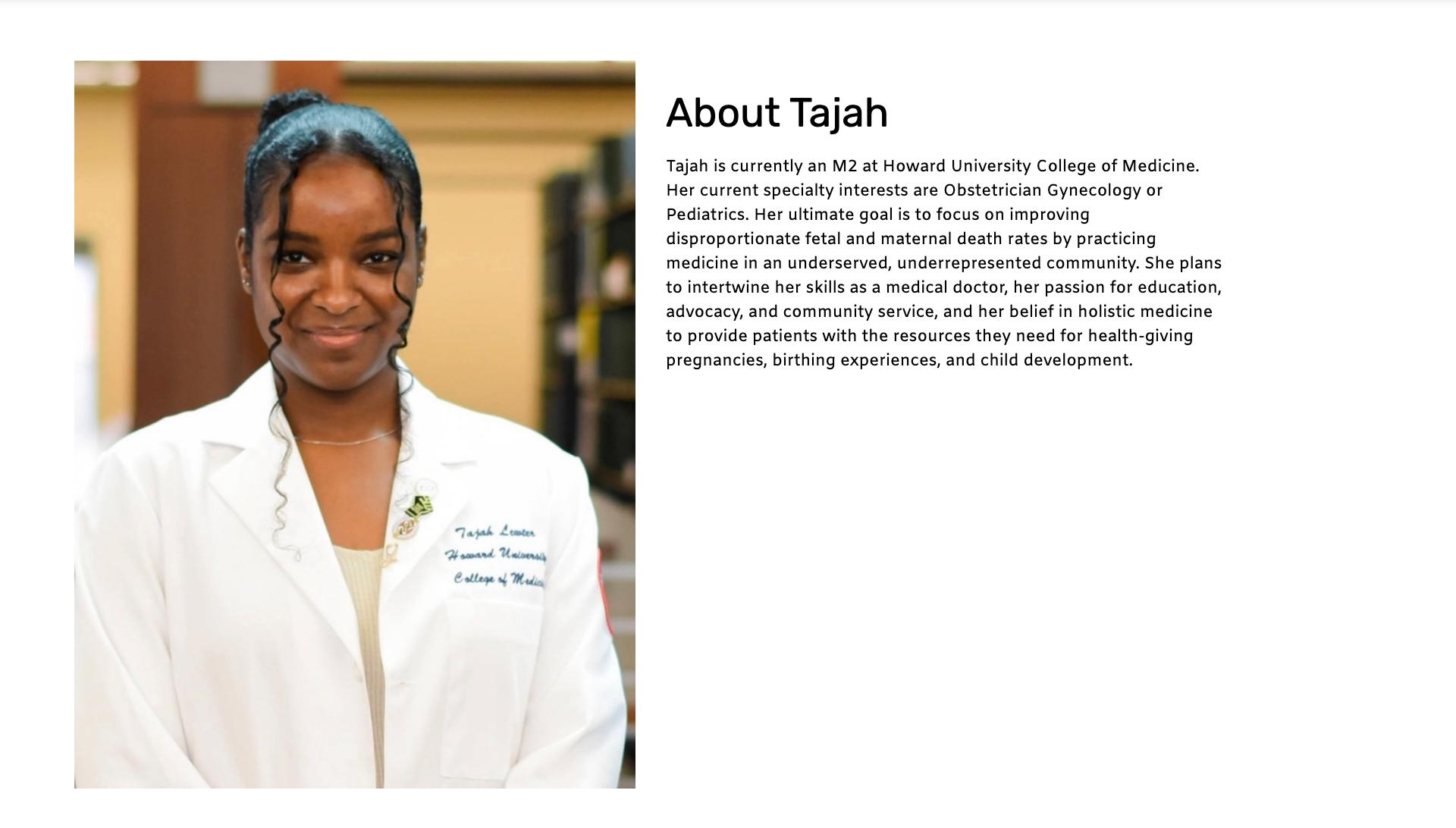

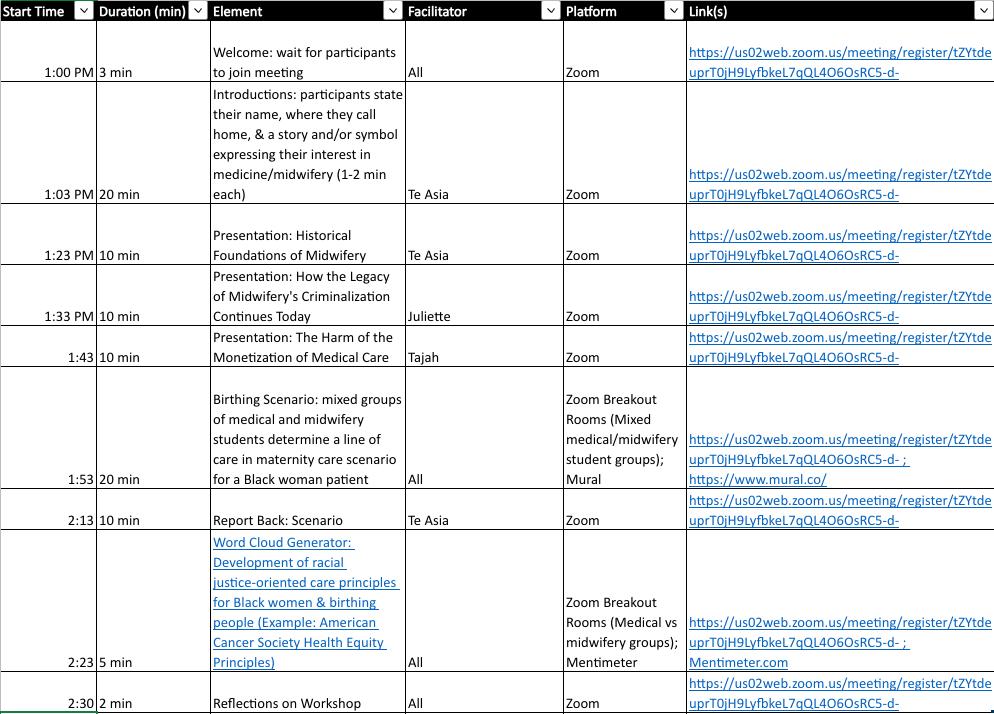

Following the interviews, a virtual workshop was planned and executed by a Black second year Public & Urban Policy PhD student studying racially-concordant midwifery-led care at The New School, a Black Columbia University nursing-midwifery student, and a Black second year Howard University medical student interested in practicing obstetrics Participants were recruited after creating a website outlining the details of the workshop The nursing-midwifery student and medical student then sent the website to their classmates who expressed their interest by signing up using the survey on the website

In addition to the planning group, this workshop ultimately convened three medical students from Howard University School of Medicine and four nursing-midwifery students from Columbia School of Nursing in early December 2023 All participants identified as women and all were women of color Specifically, all but one participant identified as Black.

Number of Midwifery and Medical Students in Attendance at the Workshop

Howard University Medical Students 3

Columbia University Midwifery Students 4

Participants began by introducing themselves to one another and shared powerful personal stories that motivated them to enter midwifery and medicine – all of which, at least in part, stemmed from news and personal experiences concerning the Black maternal mortality crisis. They listened to three 10-minute presentations about Black traditional midwifery, the role that the medical establishment played in destroying this vital community resource, the harm that continues to result from aligning medicine with capitalistic interests, and how barriers to accessing raciallyconcordant midwifery models of care contribute to the Black maternal mortality crisis The workshop was designed not only to educate participants on these topics, but also to encourage the creation of a learning and support network among these students to advance knowledge about each other’s roles within the maternal and perinatal care team, increase medical students’ respect for Black midwifery models of care, and inspire Black medical students to advocate for efforts that support Black midwives and improve Black birthing people’s access to them

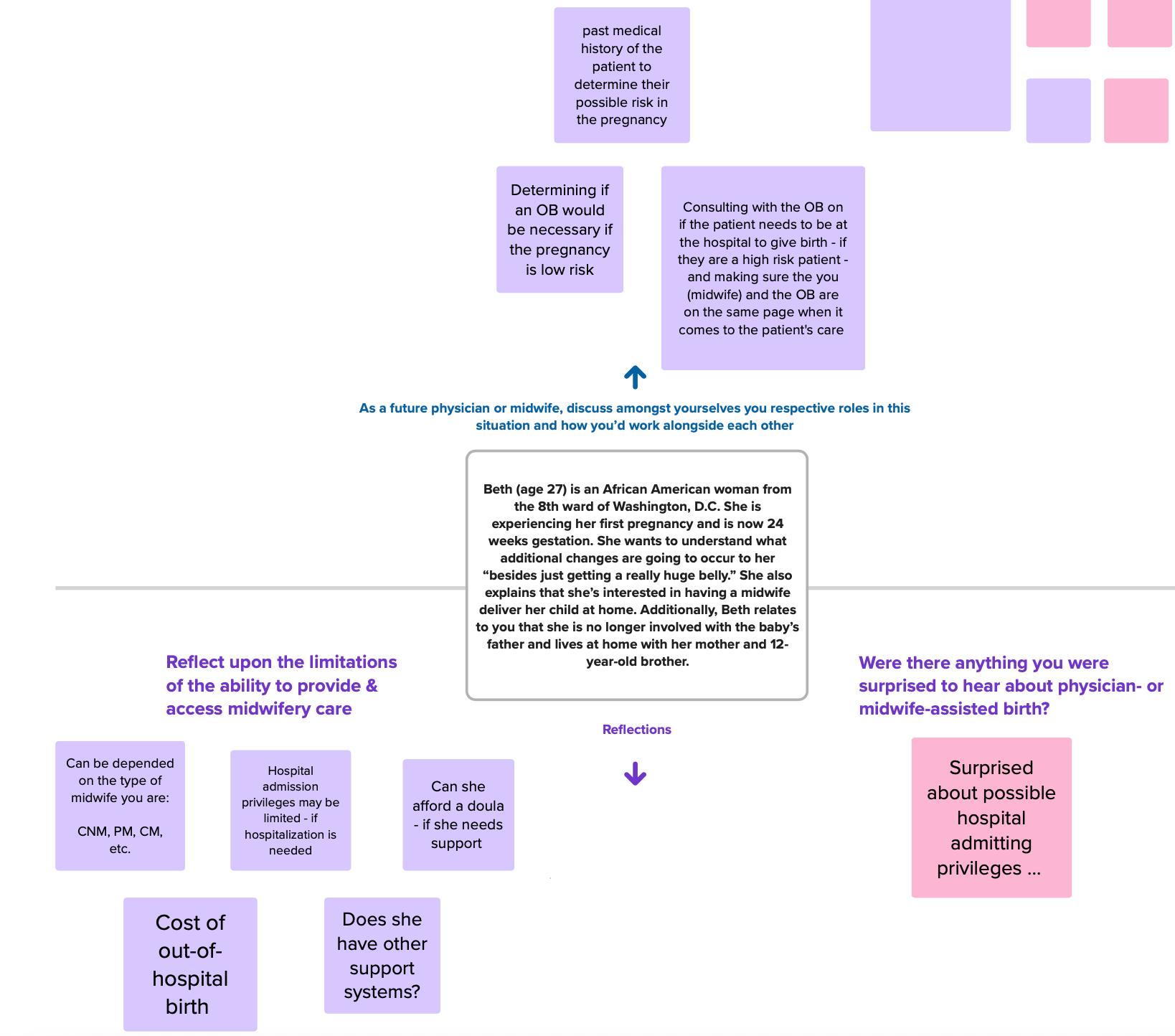

Next, midwifery and medical students worked together on a clinical scenario to devise a plan of care for a Black patient taking into consideration the social determinants of health Additionally, they learned about the positives that they each bring to the care team, as well as the barriers they face that impede improved quality of care

“As midwives…in nursing, you’re honestly constantly being reminded about your limitations, your scope, what you can and you cannot do, and really being so careful to not overstep those boundaries…Honestly, a lot of the time, it can weigh you down and make you forget what you can do and what is your knowledge”

-Midwifery Student Participant

They also discussed ways that physicians can connect their patients with midwives

“Me, myself, would push towards midwifery…if you feel like you need an OB, they can maybe push you to an OB faster than 3 months, which is a very long time when you’re having a child…I think it has to change on a bigger level, but at least individual corporations can educate people…I’ve educated myself…[As a physician] I’m here to educate you [as the patient] and now that I’ve educated you, who knows, maybe those people that I pushed towards midwifery were low-risk and didn’t need to see an OB”

-Medical Student Participant

The workshop closed with participants developing racial justice-oriented principles they believed should be at the forefront of the provision of maternal and perinatal care for Black women and birthing people

“The first thing that I thought of was liberation. In terms of so many social justice movements, we can all be the best midwives, the best OBs, and even the best doctoral students, but it can only go so far if

“I put community. I think being intentional about building community is at the forefront of not just my work but my life at this point in time. So much of our experiences as Black people –

we’re still operating in this system that generally doesn’t want us to be free”

-Midwifery Student Participant

Black birthing people – when we’re giving birth has been taken away from us because there’s been really intentional efforts on the part of these systems to tear apart our community. It’s really important to reclaim that in every aspect of our lives, particularly this one – our families: birthing them, creating them, and nurturing them, and fostering them. ”

-Midwifery Student Participant

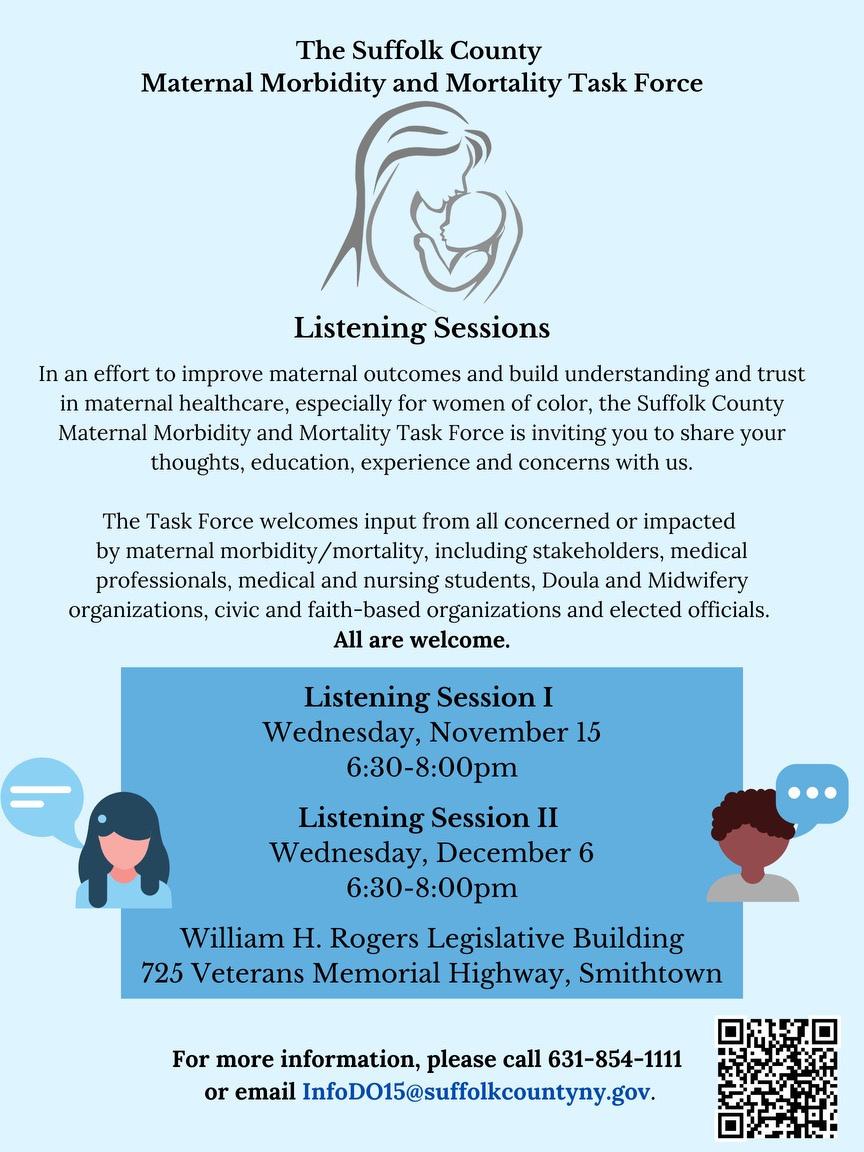

Task Force Meeting

To further supplement the research for this project, as well as satisfy personal interests, I also attended a Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Task Force listening session within my county Task force members represented major hospitals, community organizations, and legislative offices on Long Island There, I learned about how the Black maternal mortality crisis has manifested within my country and the work being done to combat it.

Protocols

Columbia University Nursing-Midwifery Student:

1-Informed Consent

My name is Te Asia Hunter and I’m a PhD student at The New School studying the history of Black midwives in this country and current-day manifestations of the tradition Before OBGYN’s attended births within hospitals, Black midwives were once the primary practitioners of maternal and infant care and traveled to birthing people’s homes to provide this care This was until the medical and public health establishments organized national campaigns to mystify childbirth as some dangerous process in need of physician management and blamed Black midwives for poor maternal and infant health outcomes by characterizing them as unintelligent witches These campaigns were successful in undermining a critical birthing resource for Black women and birthing people and restricted their options to birthing their babies in hospitals where they endure medical racism – a significant contributor to the ongoing Black maternal mortality crisis.

My goal of this interview today is to understand how certified nursing programs – the most prominent version of midwifery in the U S today – value Black midwives and their tradition that once birthed a nation. Specifically, I’m interested in understanding CNM students’ perceptions of their program’s (1) inclusion of Black midwifery in the curriculum, (2) engagement with the surrounding (Black) birthing community, and (3) strategies to diversify the disproportionately white women CNM workforce

If you allow me, I will need just 30-45 minutes of your time to ask you some questions I will record our conversation but all information you share will remain private and be deleted upon the end of my course in December. The information you help me gather will culminate into a final share out to my professors and classmates that excludes any personal identifiable information

2-CNM Curriculum

Students:

i. Please describe your program’s curriculum.

ii Is there anything you feel that your curriculum is missing and if so, what?

iii Is there anything you’d add to your curriculum and if so, what?

iv. Can you please describe the non-clinical aspects of your curriculum (e.g., population health, sociology, health equity, policy)?

v How does this fit within your program?

vi Is there anything you’d change about these courses?

vii. What do you know about the history of midwifery in this country? How did you learn this?

3-Community Engagement

Students:

i What is the community surrounding your school and what are some health-related issues they face?

ii Based on your training, how can you contribute to alleviating these issues?

iii. What opportunities does your program offer to get involved in the community?

iv Can you describe the awareness and/or perception that you believe the surrounding birthing community has of your program?

v What benefit do you believe members of the surrounding birthing community could have to your curriculum?

My name is Te Asia Hunter and I’m a second-year PhD student within The New School’s Public and Urban Policy program My research focuses on the history of Black midwives in this country, the role of the medical and public health establishments in the decline of traditional Black midwifery, the value Black midwifery-led models of care offer to mitigating the Black maternal mortality crisis and other instances of harm experienced by Black pregnant people, and how the democratization of the birthing experience can re-introduce community and celebration back into birthing As the organization you’re apart of – Village Maternity MD – provides a shining example of the democratization of the birthing process, I’d like to interview you to learn more about your organization and its efforts to provide low intervention care during labor and birth. The interview will last approximately 45 minutes and all private information will remain confidential

2-Village Maternity MD Background:

i Can you please describe the story of how Village Maternity MD came to be?

ii When was it created?

iii For what purpose?

iv What is the distinction between Village Maternity MD and the OBGYN operations at Metropolitan Hospital?

v What is your role in the organization and when did you become involved?

3-Village Maternity

Logistics

i. What are some of the efforts that you believe contributed to Metropolitan Hospital having among the lowest cesarean rates?

ii How do pregnant people decide what Village Maternity MD providers to work with?

iii. Is any education provided to them regarding what each provider does and what they can offer them?

iv What does this education consist of (e g , roles/responsibilities of providers, how this aligns with patients’ goals/birth plan, etc )?

v. How do patients in need of the services your organization provides typically find out about Village Maternity MD?

vi What role do patients’ families play in their birth process if they’re serviced by your organization?

vii Is there any limits to the amount of people allowed in the hospital room when the patient gives birth?

viii If a patient interested in having a home birth seeks your organization’s services, are there any restrictions?

ix Are there any differences in payment reimbursement depending on the provider a patient chooses to deliver their child? If so, can you please describe them?

i What is the value in collaboration between physicians, nurse practitioners, doulas, and midwives?

ii What have clinicians learned about other clinicians’ modalities of care and how – if at all –have these learnings become embedded in the philosophy of the organization?

iii Do you have a specific example that you can share?

iv What are your thoughts on co-learning between OBGYN residents and nursing-midwifery students?

i What can other health systems and organizations learn from Village Maternity MD?

ii What would you identify as the core barriers to other health systems achieving what your organization has?

iii What are some birthing justice issues or other race, gender, and/or class inequities that the organization has identified and sought to mitigate within their system?

iv Do you have a specific example that you can share?

v The literature shows us that Black women’s disproportionate rates of maternal mortality, as well being ignored and/or disrespected when they have the standard physician-managed birth within a hospital How is your organization uniquely positioned to disrupt these inequities for NYC birthing community?

vi Does your organization collect any metrics to measure patient satisfaction, access, and/or racial health inequities?

vii Are there any further thoughts that you’d like to discuss?

Flyer: Suffolk County Maternal Morbidity & Mortality Task Force

Workshop

Website: View here

References

Angolile, C M , Max, B L , Mushemba, J , & Mashauri, H L (2023) Global increased cesarean section rates and public health implications: A call to action. Health Science Reports, 6(5), e1274.

https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1274

Barker, K. (1998). Women Physicians and the Gendered System of Professions: An Analysis of the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921. Work and Occupations, 25(2), 229–255.

Berliner, H. S. (1975). A Larger Perspective on the Flexner Report. International Journal of Health Services, 5(4), 573–592.

Boerma, T., Ronsmans, C., Melesse, D. Y., Barros, A. J. D., Barros, F. C., Juan, L., Moller, A. -B., Say, L.,

Hosseinpoor, A R , Yi, M , De Lyra Rabello Neto, D , & Temmerman, M (2018) Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections The Lancet, 392(10155), 1341–1348

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31928-7

Brown, E. R. (1980). He Who Pays the Piper: Foundations, the Medical Profession, and Medical

Education Reform. International Journal of Health Services, 10(1), 71–88.

Debbink, M. P., Ugwu, L. G., Grobman, W. A., Reddy, U. M., Tita, A. T. N., El-Sayed, Y. Y., Wapner, R. J.,

Rouse, D. J., Saade, G. R., Thorp, J. M. J., Chauhan, S. P., Costantine, M. M., Chien, E. K., Casey, B. M.,

Srinivas, S K , Swamy, G K , Simhan, H N , & Network, for the E K S N I of C H and H D (NICHD) M -

F M U (MFMU) (2022) Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Cesarean Birth and Maternal Morbidity in a LowRisk, Nulliparous Cohort. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 139(1), 73.

https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004620

Goode, K., & Rothman, B. K. (2017). African-American Midwifery, a History and a Lament. The American

Journal of Economics and Sociology, 76(1), 65–94.

Harris, E. (2023). US Maternal Mortality Continues to Worsen. JAMA, 329(15), 1248.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.5254

Hoyert, D. L. (2022). Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020. National Center for Health

Statistics https://wwwcdc gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/E-stat-Maternal-MortalityRates-2022 pdf

Lett, E , Hyacinthe, M -F , Davis, D -A , & Scott, K A (2023) Community Support Persons and Mitigating Obstetric Racism During Childbirth Annals of Family Medicine, 21(3), 227–233

https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2958

MANA. (2023, August 28). Types of Midwives. MANA. https://mana.org/about-midwives/types-ofmidwife

Menzel, A. (2021). The Midwife’s Bag, or, the Objects of Black Infant Mortality Prevention. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 46(2), 283–309. https://doi.org/10.1086/710806

Niles, P. M., Baumont, M., Malhotra, N., Stoll, K., Strauss, N., Lyndon, A., & Vedam, S. (2023). Examining respect, autonomy, and mistreatment in childbirth in the US: do provider type and place of birth matter? - PubMed Reproductive Health, 20(1), 67 https://doi org/101186/s12978-023-01584-1

Niles, P M , & Zephyrin, L C (2023) How Expanding the Role of Midwives in U S Health Care Could Help Address the Maternal Health Crisis The Commonwealth Fund

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/may/expanding-role-midwivesaddress-maternal-health-crisis

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Center for Women’s Health. (2022). A Brief History of Midwifery in America Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) https://wwwohsu edu/womenshealth/brief-history-midwifery-america

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, & Commonwealth Fund (2020, November 20) U S Midwife Workforce Far Behind Globally Statista

https://www.statista.com/chart/23559/midwives-per-capita

Shroff, F M (2011) Power Politics and the Takeover of Holistic Health in North America: An Exploratory

Historical Analysis. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 9(1), 25.

Simmons-Duffin, S., & Wroth, C. (2023, March 16). Maternal deaths in the U.S. spiked in 2021, CDC reports. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/03/16/1163786037/maternal-deaths-inthe-u-s-spiked-in-2021-cdc-

reports#:~:text=The%20U S %20rate%20for%202021,deaths%20per%20100%2C000%20in%202020

Vedam, S , Stoll, K , MacDorman, M , Declercq, E , Cramer, R , Cheyney, M , Fisher, T , Butt, E , Yang, Y T , & Powell Kennedy, H (2018) Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: Impact on access, equity, and outcomes. PloS One, 13(2), e0192523. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192523

Wren Serbin, J , & Donnelly, E (2016) The Impact of Racism and Midwifery’s Lack of Racial Diversity: A

Literature Review Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 61(6) 694–706