MS Strateg ment 2024-25 Spring 2025

MS Strateg ment 2024-25 Spring 2025

External Engagement Studio X Public Policy Lab

Guided by Professor Sareeta Amrute

Main Authors

Katrina Matejcik and Monisha Raju

Contributors

Hale Celikkin, Srishti Duragkar, Meenu Jitendrakumar Runiwal, Jasnoor Kaur, BonKyu Ku, Avantika Kulkarni, David Marquez, Aishwarya Mathur, Laia Monells Tellez, Shradha Pandey, Vidhi Shah, Neha Tangirala, Harsh Vatsa, Jagriti Yadav

Research Summary

Introduction

Project Challenge

Project Constraints

The Studio Structure

Methodology

Overview

PART A

- Case Study

- Pre-Field Work

PART B

- PPL Office: Fieldwork Methods

Findings and Analysis

PART A - Secondary Research

- Case study and external interviews

PART B - Direct Engagement

- PPL office: Field Observation Notes

Inferences from the Interview

- Opportunities

- Organizational Structure

- Internal team dynamics and roles

- Challenges for futures thinking

- Importance of Futures Thinking

- Codesign and prototyping

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendix

The Public Policy Lab (PPL), a nonprofit innovation lab focused on designing policies and programs for low-income and marginalized Americans, Partnered with Parsons’ MS in Strategic Design & Management students (2024-25) to help evolve its design approach Students in the External Engagement Studio (EES) were challenged to integrate future-oriented thinking into PPL’s standard, human-centered design process (the PPL Release Model) The goal was to reimagine civic design so that it accounts for the needs of future generations without compromising the immediate goals of clients or overburdening design teams.

How might we reimagine the civic design process to include considering the needs of future generations while continuing to meet the central needs of current-state users and project clients?

Two important constraints that PPL wanted the studio to consider:

1.The project partners and funders of PPL have narrow goals and objectives

2. Every additional ask of the project teams increases the workload and, as an organization, PPL values work-life balance

The Studio Structure

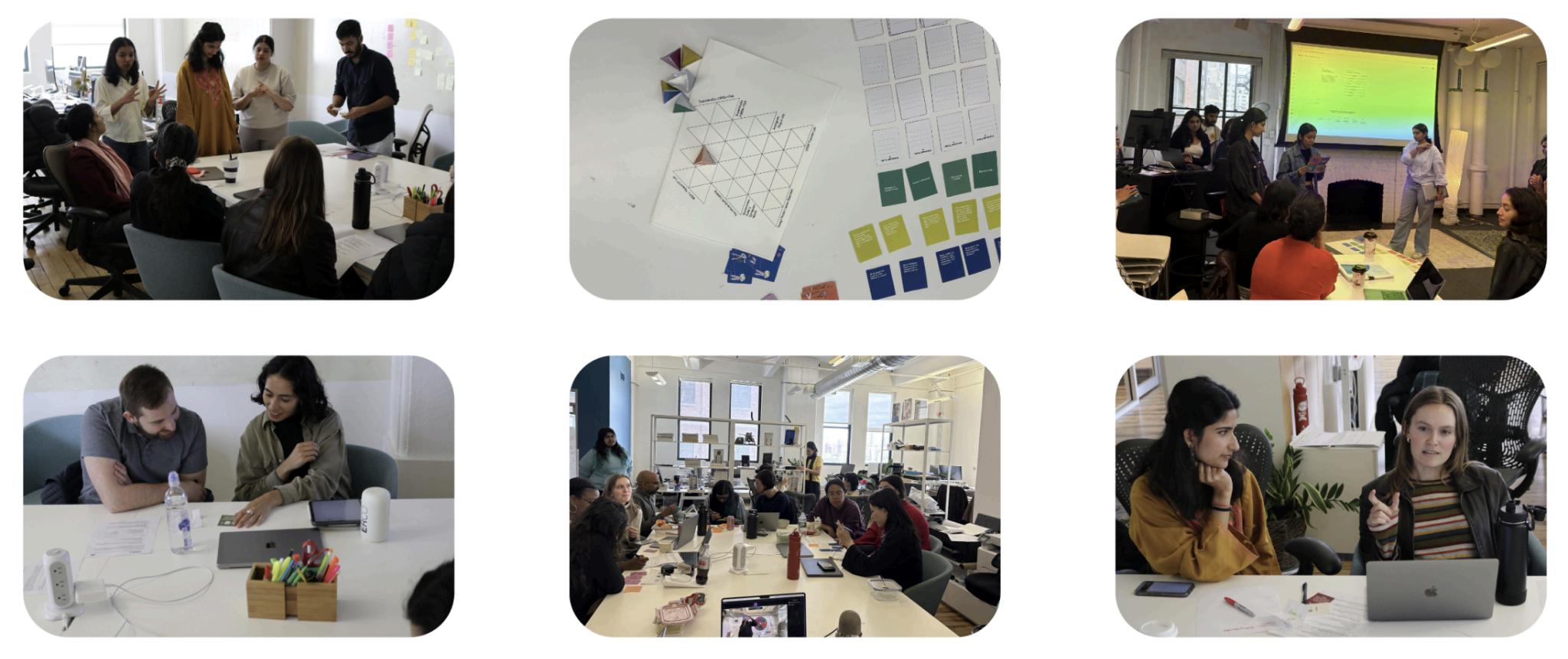

Over the course of 15 weeks, 16 EES students worked directly with PPL teams to explore how civic design processes might incorporate future-thinking while meeting current client needs. Students became familiar with PPL's methodology, beginning with problem definition and research, then moving through ideation and prototyping phases to develop human-centered solutions The studio culminated in final presentations where students showcased their process and design responses to the original challenge brief.

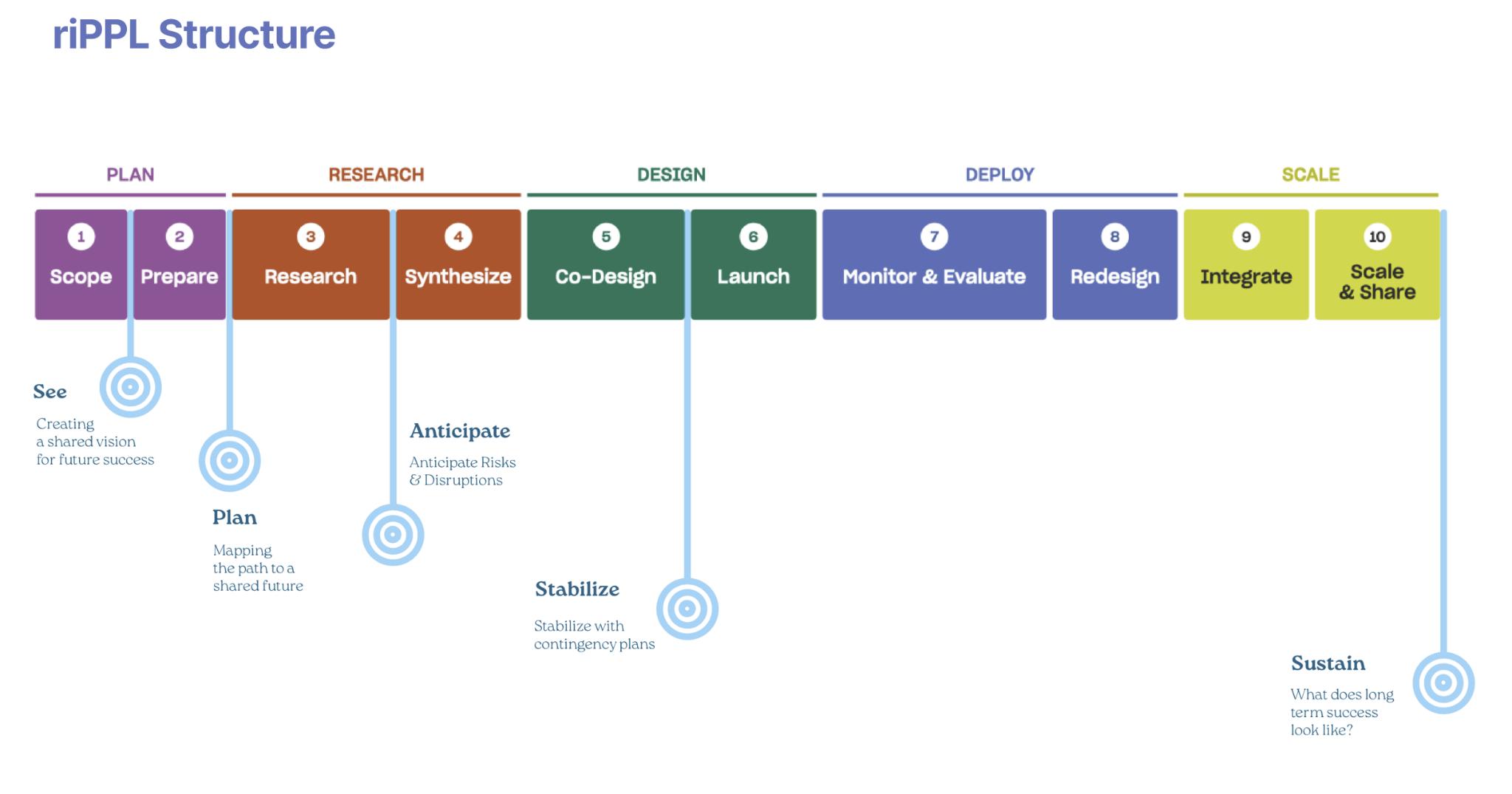

PPL’s commitment to openness and public accessibility made their online resources a valuable primary source of data for our research. Their human-centered, co-creative, and material-based approach allowed us to understand their iterative design process particularly how they pilot and test solutions The External Engagement Studio began by focusing on the Sprint Release Model as the initial entry point to learn about the organization’s process This model brings together both designers and non-designers through a predictable and coherent workflow, offering a shared structure for collaboration across the team.

The Studio approached the PPL challenge with the goal of gathering data to test three initial assumptions:

1. The idea of the future varies depending on the project, client, and team.

2. The team generally operates with a flat or non-hierarchical structure (though this may not be entirely consistent)

3 There is a universal approach to integrating the futures prompts across all projects, rather than adapting them to specific sectors

The research was grounded in qualitative methods and carried out in two parts over the 15-week course. The methods were influenced by practices in participatory design and design ethnography, as outlined by Akama and Light (2015), and Visocky O’Grady & O’Grady (2017), emphasizing on interpersonal dynamics, co-creation, and reflexivity in institutional settings

Part A involved secondary research and data collection from online sources. Part B focused on direct engagement with the team and observation of the space through ethnographic methods, including interviews, observation, and participation.

The study was designed to understand PPL’s organizational structure and internal team dynamics, with a focus on the roles and interactions of individual team members The class used an ecosystem map to categorize employees and visualize their relationships within the organization.

While initial research and data gathered from online sources provided a foundation, it left some gaps in understanding the team's day-to-day operations To guide our fieldwork, we outlined several key questions we aimed to explore further:

● How do PPL employees collaborate across teams, and what do their daily routines, workflows, and time constraints look like?

● What prompts or tools are currently used for brainstorming and synthesis within teams?

● When are their existing prompts typically used, and what kinds of outputs do they usually generate?

● What aspects of the office space and work environment influence team collaboration and overall functionality?

● Additionally, we sought to understand ways in which futures thinking currently fits if at all into their existing workflow When do teams consider long-term impacts or alternative futures in their projects? What appetite or capacity exists within PPL for integrating foresight practices into their decision-making processes? These were informed by frameworks from Designing for Growth (Liedtka & Ogilvie, 2011) which emphasizes on embedding foresight based tools within organizational workflows

Ecosystems Map

To explore ways futures thinking could be integrated into PPL’s ongoing work, our studio studied organizations that have successfully embedded long-term thinking into their decision-making processes

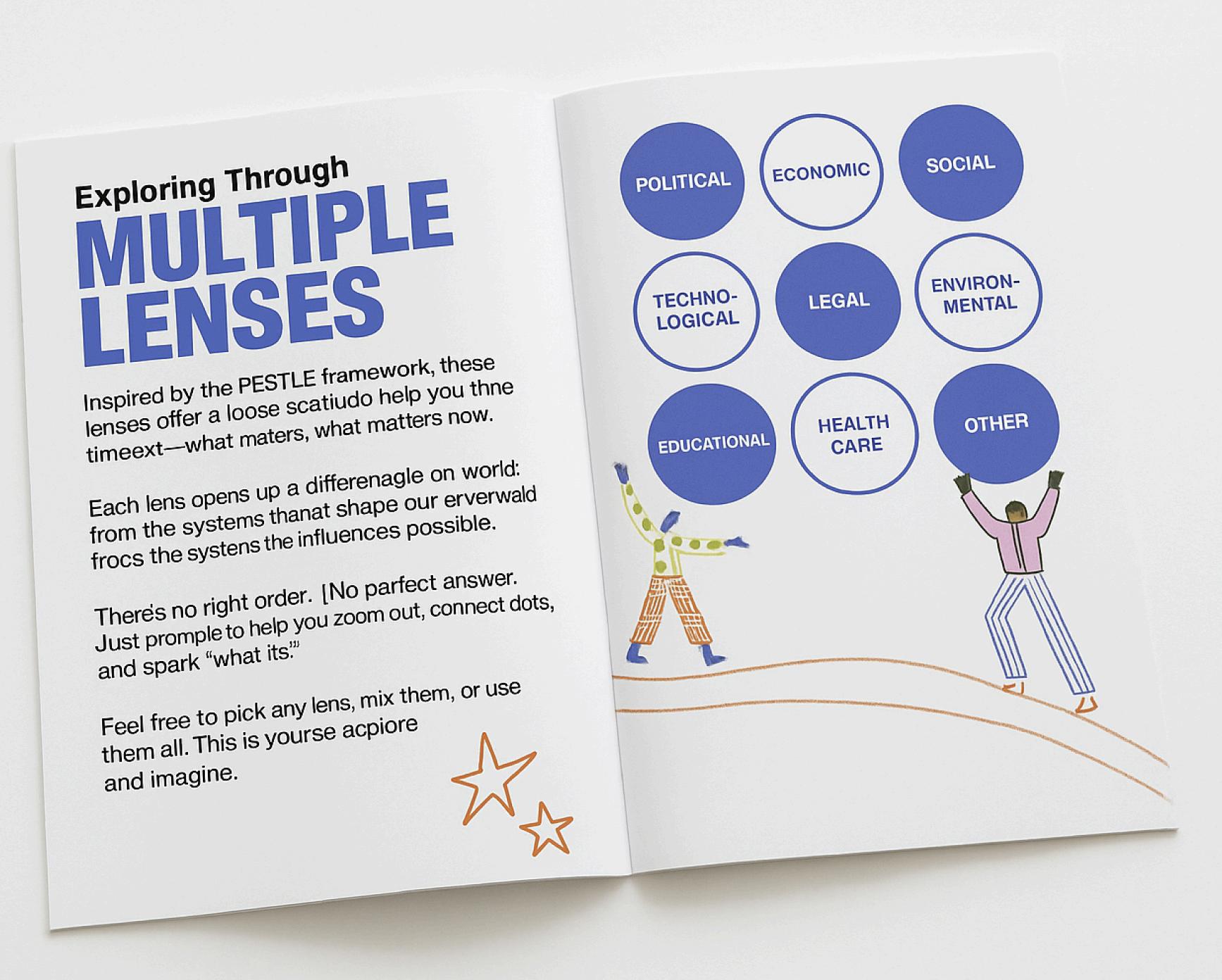

As part of the peer and competitor comparative study, we identified several international organizations to understand diverse approaches to strategic design and public innovation through a futures lens Scandinavian countries, in particular, were chosen for their longstanding commitment to design-led governance, transparency, and citizen-centered public services. We reviewed The Danish Design Center’s New Days Future Kit, as a practical tool for applying futures thinking in public engagement. From Sweden, we examined the work of SVID (Swedish Industrial Design Foundation, formerly SIG), particularly to understand how their methods could translate to the U S context Estonia’s government was explored through its e-Estonia initiative, a strong example of transparent, publicly accessible digital infrastructure such as e-residency, digital ID, and open data portals supported by user-centered design resources.

Shift Design was a UK-based social innovation studio that used service design and systems thinking to create long-term, community-centered solutions to social and environmental challenges Shift Design was studied to understand the factors that led to their closure and lessons that could be learned from their experience. The Helsinki Design Lab, an initiative under Sitra the Finnish Innovation Fund was reviewed for its systemic and policy-focused design work aimed at rethinking inherited structures and enabling long-term government innovation Finally, the Van Alen Institute, based in Brooklyn, New York, was considered for its community-led urban design, highlighting the importance of incorporating local knowledge into the design process and activating public space through inclusive, place-based engagement.

These case studies helped us understand and identify some key ideas that were common across all of them. There was a major emphasis on intentional integration of long-term thinking into day-to-day decision-making often through accessible frameworks. Futures thinking was most effective when paired with tangible tools, like the Danish Design Center’s New Days Kit, which helped make abstract concepts actionable Scandinavian models in particular emphasized policy-level integration, design literacy within government, and iterative learning processes.

Meanwhile, the closure of Shift Design highlighted the structural challenges of sustaining

mission-driven work, such as balancing experimentation with financial viability Collectively, these examples underscored the need for flexible infrastructure, inclusive processes, and a strong alignment between design values and institutional goals to embed futures thinking meaningfully and sustainably within civic organizations. These studies formed the foundation for engaging with the work of PPL in person.

As a part of our reflexive and relational research approach, the studio engaged in a series of preparatory steps to ground our fieldwork in intentionality, care, and ethical awareness We began by defining and clearly outlining how we would present ourselves as researchers clarifying our goals, setting boundaries for the research process, and aligning as a class on the intended outcomes of the project. Drawing on practices outlined in This is Service Design Doing (Stickdorn et al , 2017), we developed an interview guide with questions for each role at PPL, organized by thematic areas to allow flexibility and responsiveness during conversations. In parallel, we conducted a detailed review of PPL’s public presence not only through their website but also across platforms such as YouTube, LinkedIn, and other social media to inform more specific and context-aware research questions.

To understand PPL’s internal processes, we also mapped ways to mirror their workflow, including shifting our team’s collaboration tools to Slab and Slack. Additionally, we created a Fly-on-the-Wall Observation Template to support non-intrusive, ethically grounded engagement during fieldwork. This framework was designed to help us document nuanced team dynamics, language, and behaviors without actively disrupting the natural flow of work It emphasized active listening, contextual interpretation, and ongoing reflexivity, helping us to identify patterns in communication, power, collaboration, and organizational culture. The framework also served as a means for us to critically reflect on our own positioning and align our documentation practices with PPL’s values of care, inclusion, and co-creation

As part of the fieldwork, interviews were conducted with both internal team members and external stakeholders to better understand their roles, team dynamics, and expectations through their lived experiences

Observation and shadowing were two key methods that were adopted of both individual

tasks and team meetings, including project kick-offs, informal gatherings like PPLunches, sprint planning, strategy and product discussions, and retrospectives to gain more insights into daily workflows In an effort to empathize with their ways of working, PPL’s internal frameworks were also incorporated into the studio’s process, such as mimicking the Release Model.

Over the course of the project, the studio conducted a total of 19 interviews, including 10 with members of the Public Policy Lab and 9 with external experts We also participated in 8 internal meetings, including sprint planning sessions, benefits coordination meetings, biweekly critiques, and practice reviews. In addition, we facilitated 2 co-design workshops with the PPL team to collaboratively explore opportunities for integrating futures thinking into their workflows Additionally, we engaged in approximately 12–15 hours of observation and shadowing to study PPL’s communication patterns, team dynamics, and decision-making processes in their office. To support synthesis, we developed 3–4 stakeholder and ecosystem maps that helped visualize organizational roles, partner relationships, and internal processes

Specific ethnographic methods were used, including asking participants to draw their office space or map out a perceived hierarchy of the organization These exercises helped surface blind spots and highlight deeply embedded assumptions and practices. Additionally, informal notes and scribbles were documented to uncover what employees subconsciously prioritize.

Our fieldwork helped frame the strengths and limitations of currently including futures thinking into PPL’s practice. While there was genuine interest across the team in integrating long-term perspectives into projects, futures work often remained informal, individually driven, and deprioritized amid tight delivery timelines We observed strong team cohesion, thoughtful rituals like PPLunch that fostered cross-role dialogue, and an overall culture of care and adaptability However, we also noted recurring structural challenges, including synthesis bottlenecks, ambiguity in role clarity across projects, and misalignment between PPL’s internal pace and the expectations of public sector partners. These insights helped to identify key opportunity areas where small interventions could have outsized impact particularly in designing structured yet flexible futures prompts, improving internal communication tools, and creating space for reflection within the fast-paced project cycle The prototypes that followed were directly informed by these findings, aiming to operationalize futures thinking in ways that were lightweight, adaptable, and aligned with PPL’s values and constraints.

Detailed findings are collated in the next section

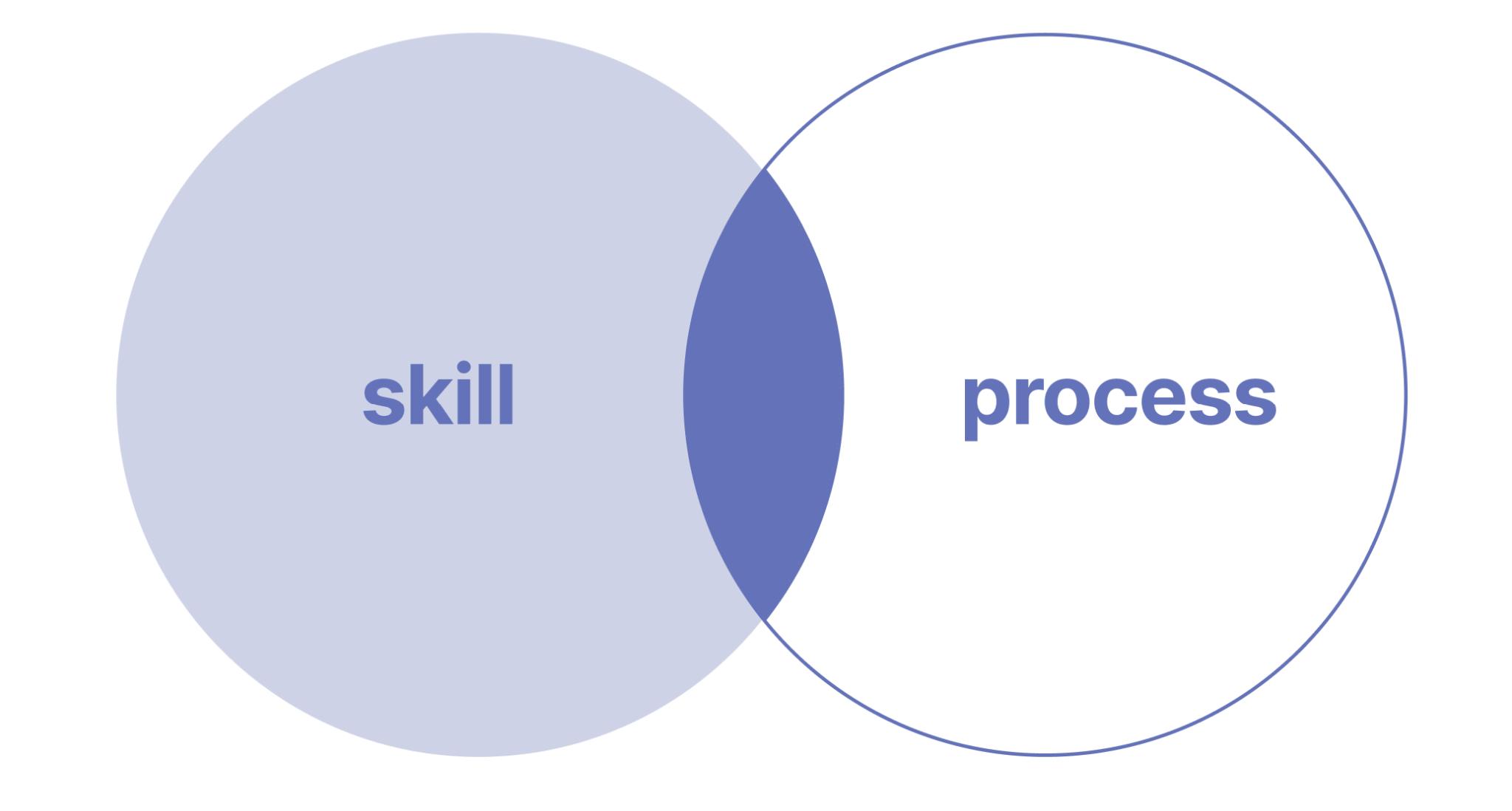

Following our fieldwork, case study analysis, and conversations with external interviewees, a key insight that emerged was the importance of adopting a people- and process-oriented strategy to embed futures thinking within the organization. These two areas people and processes were identified as critical for building internal capabilities and integrating long-term thinking into the existing work ecosystem

The studio used a co-design workshop as a method to test and better understand ways to interweave a thinking model into PPL’s existing processes. By bringing together internal team members, the workshop created space for participants to collaboratively envision long-term possibilities Through a series of guided activities the studio identified ways individuals interpret the concept of the future in relation to their work This not only helped uncover gaps in ways futures thinking is currently applied, but also identify moments within their workflow where such thinking could be most impactful. The workshop served as both a diagnostic and generative tool, allowing to test early ideas and gather insights directly from those who would eventually use or be affected by a futures-oriented approach

The co-design workshop future validated the need to move with the two broad approaches of skill development and integrating futures-oriented toolkit: a model that PPL could use within their internal work and with their partners. The studio also engaged with external stakeholders in prototyping sessions to test potential methods for seamlessly incorporating futures-oriented strategies into PPL’s practice

The studio began the research process by gathering data from publicly available online resources and engaging with external stakeholders, as outlined in Part A. This initial phase helped us build context, develop informed lines of inquiry, and establish a foundational understanding of PPL’s work and positioning Part B followed our in-person visit to PPL’s office, where we deepened our understanding through immersive fieldwork, including interviews, shadowing, and participatory methods. This two-part approach allowed us to triangulate insights and surface both the visible structures and the underlying cultural dynamics that shape how futures thinking could be meaningfully integrated into PPL’s existing practices The findings from both phases are detailed in the following section

As part of our comparative research, we interviewed Alex Anacki from New America, a public policy think-and-action tank, to explore how futures thinking is applied in policy-focused organizations. The conversation emphasized the critical role of relationship-building and routine collaboration in shaping long-term strategies

In the interview conducted on February 27, 2025, Alex explained that his work primarily involves facilitating communication and credit-sharing across colleges and universities in Washington, D.C. He focuses on building relationship-driven channels between various actors such as private companies and students, inter-departmental university teams, and program staff. His approach to long-term planning is rooted in making collaborative sessions a routine practice While acknowledging that work can be conducted through Zoom or email, he emphasized that meaningful innovation stems from the trust and empathy developed through consistent, in-person interactions.

These external interviews included conversations with individuals working in government innovation labs, design consultancies, civic tech initiatives, and policy think tanks. From these discussions, we learned about the practical challenges of integrating futures thinking into time-constrained public contexts, the need for adaptable tools that accommodate both organizational culture and political cycles, and the importance of building long-term capacity rather than relying solely on one-time interventions. These insights helped us benchmark PPL’s practices against a broader landscape and identify opportunities to strengthen their approach to speculative and strategic design

The EES was able to visit the PPL office in Brooklyn, beyond having conversations with PPL employees, students were able to observe how the office operated through what was present in their office. There were many playful elements, areas that encouraged collaboration, and settings to focus independently. The mix of analog and digital tools showed the range of different workflow that might not have been obvious through interviews or meeting observations Multiple surfaces encouraged people to write on the walls, pin up, and share expressions of their thinking. PPL projects often focus on serious subjects, but there is an

inherent joy express within their workplace through sketching on the walls, vibrant colors, and even toys interspersed between typical office equipment The following images are from the PPL office and show the range of work settings and playful elements in the space

Despite the constraints, there are several opportunities to enhance futures thinking at PPL Greater flexibility in project workflows could allow teams to respond more effectively to the unique demands of each engagement. Investing in training and team capacity-building can introduce new ways of thinking and support the integration of long-term planning tools. While systemic and political factors often limit transformative change in government contexts, many public sector professionals remain highly mission-driven and committed to making a difference This intrinsic motivation, when supported by adaptable frameworks and leadership alignment, presents a significant opportunity. Moreover, although structured models like the Release Model promote efficiency, re-evaluating them to support more experimental and adaptive approaches could unlock new potential for innovation Ultimately, effective transformation in the public sector requires both structural design interventions and careful political navigation

The employees at PPL were interviewed to understand the organization’s structure, daily operations, and perspectives on integrating futures thinking Anonymized summaries of these interviews can be found in the appendix. These conversations revealed patterns across various roles and highlighted both organizational strengths and areas of tension.

PPL’s organizational structure is a combination of top-down and bottom-up dynamics While leadership teams are responsible for setting high-level goals and strategic direction, feedback from team members on the ground plays a critical role in shaping how those goals are executed. In regard to futures thinkinking and organizational structure, one PPL Project Lead stated, “Depending on how high they are on the layer cake, if you ’ re more senior, I think that there’s actually more appetite for future forward work ” Despite functioning with an almost flat hierarchy in day-to-day work, there are moments when external partners override internal processes, introducing tension and sometimes undermining team autonomy. This fluid, collaborative structure allows for flexibility and responsiveness, but also requires careful coordination to manage overlapping responsibilities and maintain consistency across projects

Interviews revealed more about PPL’s internal culture, which is shaped by a fluid team structure at the intersection of strategic, creative, and operational roles Design Operations and Management team members focused on the sprint-based workflow and the structure provided by the release model. They emphasized efficiency and the need to balance creativity with timelines and deliverables Leadership, including the PPL founder, pointed to broader challenges such as long-term feasibility in government settings, political constraints, and systemic barriers that can hinder innovation.

Senior designers and researchers emphasized the importance of community insights and research synthesis, sharing how they often navigate the tension between addressing current needs and imagining long-term futures. Similarly, the service design and policy research team explored how policy change could be more meaningfully aligned with design processes, highlighting the role of systems thinking in bridging the two

Analysts and researchers spoke about the balance between structured processes and the flexibility required in research-intensive projects. Meanwhile, the content and strategy teams reflected on how stakeholder buy-in, scalability, and policy adoption play a role in sustaining project impact Senior analysts brought valuable insight into the use of mixed methods and the integration of quantitative data into evolving research approaches

A recurring theme across interviews was PPL’s fluid team structure Despite formal titles, team members often take on shared leadership responsibilities, reflecting a non-hierarchical, collaborative culture. This overlapping of roles is both a strength and a challenge, as it enables agility but can also create ambiguity in decision-making and ownership

Interviews and observations revealed several recurring challenges that limit the integration of long-term, futures-oriented thinking into PPL’s workflows. Funding limitations often restrict the scope of what can be explored or implemented. A leader at PPL expressed some of the challenges of futures thinking in an interview:

"We can't even design things for the next Administration We are working in government contexts, where authority comes from an elected official who has a four-year term And, particularly if you were in the second of those four-year terms There's no sense that you can do meaningful work again in the social service sector that is not going to have any payoff in this term. It's just going to cost money and take time and require political Capital The payoff is five years from now or 12 years from now "

Project pressures such as tight deadlines, unpredictable timelines, and resource constraints force teams to prioritize immediate deliverables over broader strategic thinking Partners and clients tend to focus on current-state needs, leaving little room to explore future scenarios. Teams frequently struggle to balance short-term requirements with long-term planning, and complex resource allocation further complicates this dynamic. A PPL Project Analyst stated in an interview, ‘It never feels like there's enough time And I don't know if that's because we always try to do too much” These constraints, combined with the lack of time and flexibility, create barriers to embedding future thinking meaningfully into everyday practice.

Future thinking is recognized as valuable and relevant across different stages of PPL’s design process. Many interviewees highlighted the importance of embedding it early in the project lifecycle to inform scalable, sustainable solutions and plan for potential crises There was a clear call for a “dual-timeline” approach one that addresses immediate user needs while also considering long-term societal shifts. Rather than treating futures thinking as an optional layer, participants emphasized that it should be an integrated and ongoing part of the workflow. However, there’s still uncertainty about how to apply these methods consistently and in ways that align with existing structures like the Release Model

Codesign and prototyping

Workshop 1

U

Fig: Activity outline of the workshop on figma

Agenda

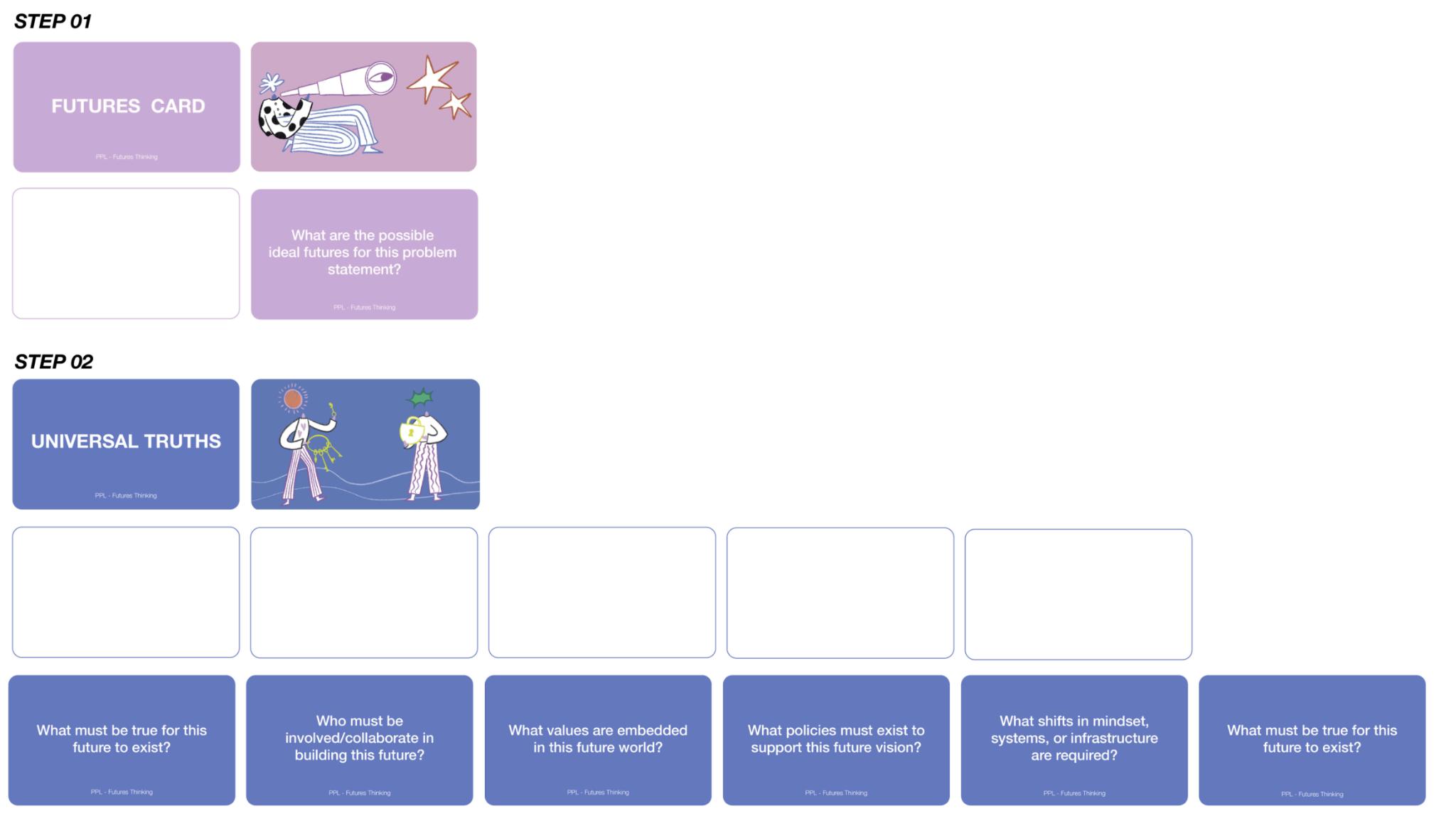

During the workshop, the studio collaborated with Public Policy Lab (PPL) employees to address the pressing issue of emergency room overcrowding in post-pandemic Baltimore. The centerpiece of the session was a futures thinking game, where teams picked chits to determine project phases and drew Situation and Action Cards that introduced complex, real-world challenges Each team analyzed their scenario and crafted strategic responses Guided by a Now/ Next/ Future framework, participants explored how to meet immediate needs while also planning for short- and long-term solutions to build a more resilient and future-ready healthcare system Teams articulated their strategies, identified key deliverables, and anticipated potential barriers They then presented their proposed approaches, followed by a peer voting process to recognize the most innovative and adaptive solution The workshop concluded with a collective reflection on insights gained and the role of futures thinking in driving effective, equitable change both within PPL’s work and in the broader context of their collaborations with public and community partners

Goals

Building a futures thinking muscle is essential to the body of work that Public Policy Lab (PPL) undertakes. The goal of this activity was to provide the team with all the necessary "nutrients and minerals" tools, insights, and reflections to help them recognize gaps in their current practices and begin strengthening this critical capability. Just as a healthy body requires intentional care and training, a healthy policy practice needs continuous foresight and adaptation

The primary goals of this workshop were to strengthen participants’ futures thinking skills and their ability to collaboratively address complex policy challenges

Through the DieGame activity, participants exercised their capacity to anticipate emerging issues, adapt strategies in real time, and design solutions across immediate, short-term, and long-term horizons The game encouraged creative, evidence-based problem-solving by challenging teams to respond to dynamic scenarios such as emergency room overcrowding in post-pandemic Baltimore using Situation and Action Cards.

Participants developed innovative policy options and identified risks, leveraged opportunities, and articulated clear deliverables and anticipated challenges The collaborative format promoted cross-sector dialogue, challenged assumptions, and built a shared language for futures-oriented governance. Ultimately, the workshop aimed to empower participants to integrate futures thinking into their ongoing work, enhancing the adaptability, resilience, and human-centered focus of public policy design

Fig: Cards used during the workshop

In this session, Public Policy Lab (PPL) team came together to collaboratively explore a pressing issue facing Baltimore’s healthcare system: the chronic overcrowding of emergency rooms (ERs) Since the pandemic, public hospitals in the city have seen increased ER demand, leading to longer wait times, delayed treatment, and burnout among medical staff. The goal of the session was to think not only about immediate fixes, but also longer-term solutions that could lead to a more sustainable and responsive healthcare system

To approach this complex challenge, we used a futures thinking framework built around three timelines: Now (immediate actions), Next (short-term planning: 1–4 years), and Future (long-term planning: 5+ years). We divided the group into five teams, with 2–3 people per team, and assigned each team two consecutive stages from a 10-step release model (R1–R10). Each step represented a key phase in the policy design process from defining the scope to scaling a solution The release cards provided real-world context and a focused task

After a short introduction to the brief, timelines, and tools, teams began working with sticky notes, notebooks, and printed sheets to brainstorm ideas and map strategies across the three time horizons. The working session lasted 20 minutes, followed by 10 minutes of sharing, where teams presented their ideas and offered feedback to one another. Throughout, facilitators provided guidance and helped teams stay focused and supported

This workshop was designed to help the PPL team grow their futures thinking skills, the ability to imagine different possibilities and plan for them. Like building a muscle, this kind of thinking takes practice, the right tools, and support. The session offered a playful and structured way for teams to build that strength together, encouraging curiosity, collaboration, and confidence in thinking ahead

The goal was to make space for imagining not just what needs to happen right now, but also what could change in the next few years and what kind of system we want to see in the long run. Using a real-life challenge, teams explored different stages of the work: from understanding the issue to designing and scaling solutions, all through the lens of time-based thinking

The teams were introduced to ways of working across time now, next, and future while practicing collaborative planning using structured tools and prompts It helped build a shared language around systems and design thinking, and reminded participants that even playful methods can lead to serious, thoughtful futuristic ideas. Ultimately, the workshop encouraged everyone to look beyond short-term fixes and consider the long-term impact of their policy and design decisions

Through the research, co-design workshop, the studio gained an understanding of PPL’s work process, organisation culture, and team dynamics In response to the core challenge: How might PPL reimagine the civic design process to account for the needs of future generations while continuing to serve current users and project clients? Two interconnected approaches were developed for integrating into the work process and skill development of the team We built something dynamic and adaptable:

The first approach focused on the creation of a skill-building resource that supports both internal onboarding and external partner education. This took three forms:

1. PPLay Book for exercises in backcasting

2 Futures Card Game to encourage collaborative futures thinking

These three skill building resources introduce and expand on key futures thinking methods such as trend analysis, scenario planning, backcasting, and holistic systems thinking to help embed long-term perspectives into everyday decision-making

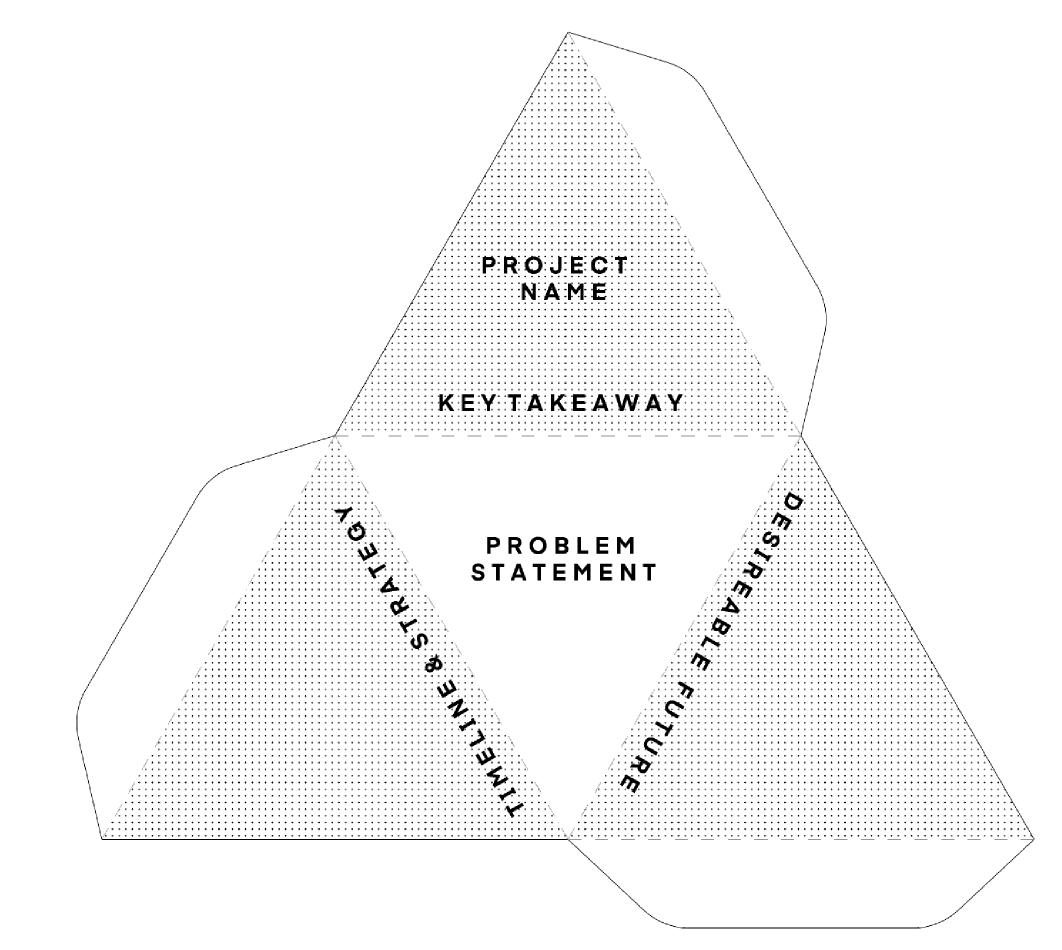

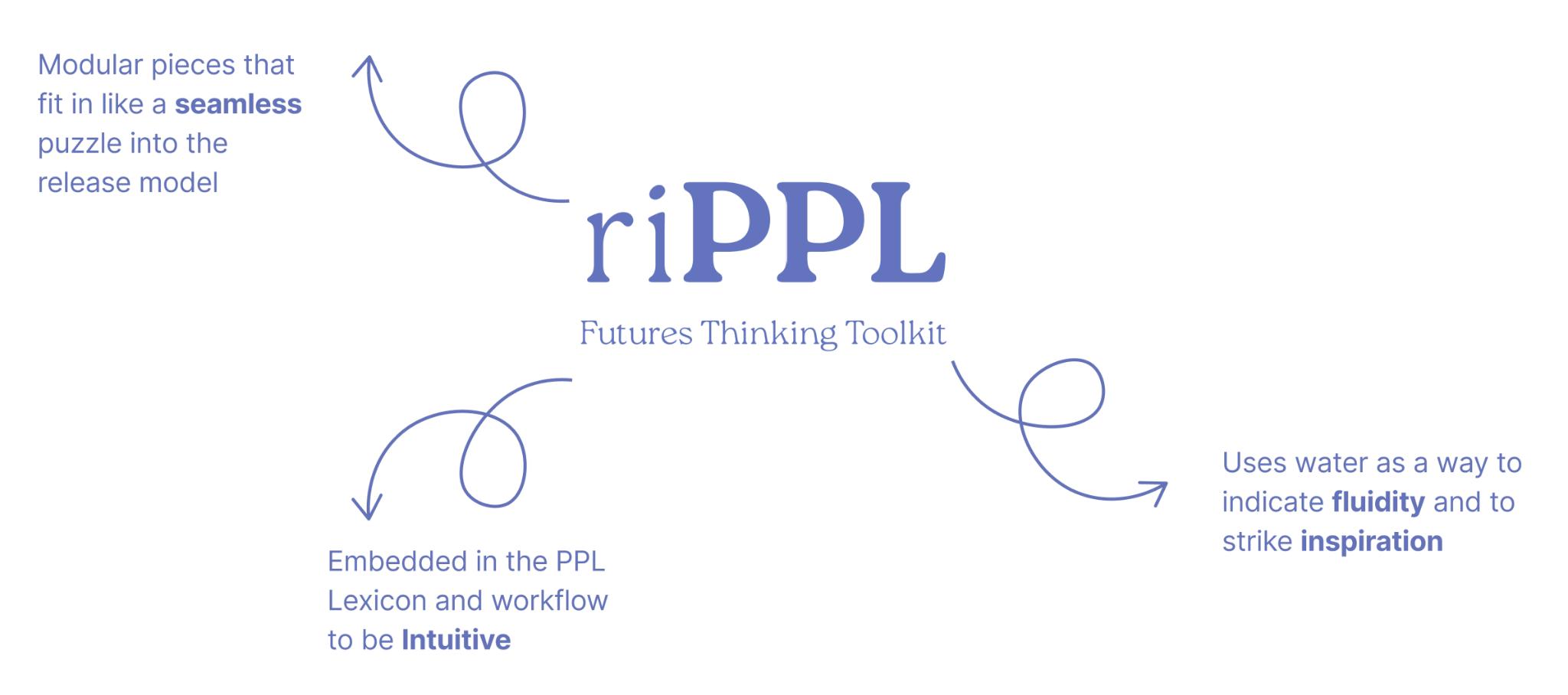

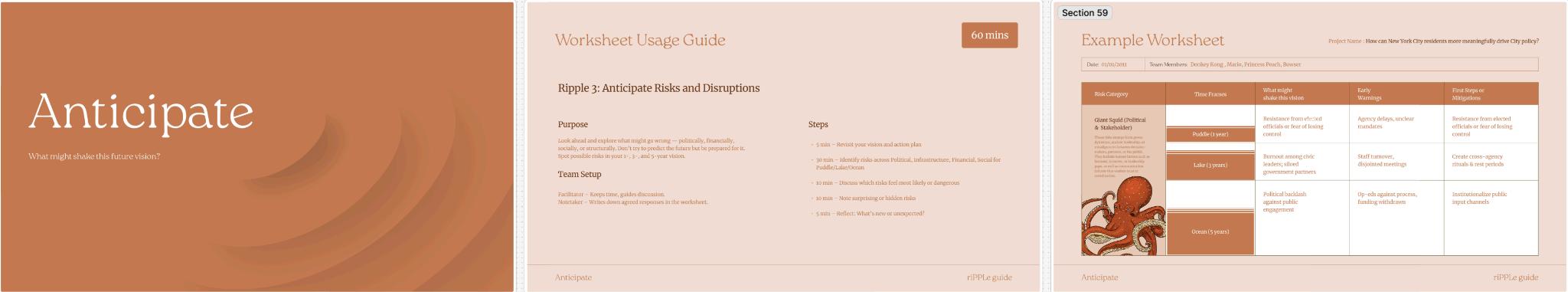

The second approach focused on process The prototype made to explore this was riPPL, a futures thinking toolkit designed to integrate into PPL’s existing workflow specifically, mapping aligning with opportunity points within the Release Model

Fig: identifying the touchpoints of riPPL with the current timeline

riPPL prototype of the worksheets

Rather than adding an entirely separate layer, the toolkit is designed to run in parallel with PPL’s current processes, offering prompts and exercises at critical stages of project development. The inspiration from biomimicry and

By the end of the 15-week semester, the studio delivered a set of prototypes, tested tools, and provided clear guidance to help PPL meaningfully incorporate futures thinking into their civic design practice strengthening their ability to serve both present and future communities

Akama, Yoko, and Anne Light “Relational Ethics for Participatory Design ” Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference, 2015.

Aulet, Bill. Disciplined Entrepreneurship: 24 Steps to a Successful Startup. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013

Bethune, Kevin “The 4 Superpowers of Design ” TED Talk https://www.ted.com/talks/kevin bethune the 4 superpowers of design.

Epstein, Eli “9 Innovative Methods for Modern Storytelling ” Mashable, July 1, 2014

Holmes, Kat. Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

Knapp, Jake, John Zeratsky, and Braden Kowitz. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016

Kumar, Vijay 101 Design Methods: A Structured Approach for Driving Innovation in Your Organization. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013.

Liedtka, Jeanne, and Tim Ogilvie Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Toolkit for Managers. New York: Columbia Business School Publishing, 2011.

Monarth, Harrison “The Irresistible Power of Storytelling as a Strategic Business Tool ” Harvard Business Review, March 11, 2014.

Osterwalder, Alexander, Yves Pigneur, Gregory Bernarda, and Alan Smith Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2014

Stickdorn, Marc, Adam Lawrence, Markus Hormess, and Jakob Schneider This is Service Design Doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, 2017.

van der Pijl, Patrick, Justin Lokitz, and Lisa Kay Solomon Design a Better Business: New Tools, Skills, and Mindset for Strategy and Innovation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2016.

Visocky O’Grady, Jenn, and Ken Visocky O’Grady A Designer’s Research Manual: Succeed in Design by Knowing Your Clients and What They Really Need 2nd ed Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers, 2017.

Zeratsky, John, Jake Knapp, and Braden Kowitz Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Danish Design Centre New Days – A Future Kit for Exploring Possible Futures Copenhagen: Danish Design Centre, 2022 https://danskdesigncenterdk/en/new-days

SVID – The Swedish Industrial Design Foundation Design for Public Sector Innovation Stockholm: SVID, accessed 2025. https://svid.se

e-Estonia Briefing Centre e-Estonia: The Digital Society Tallinn: e-Estonia, Government of Estonia, 2022. https://e-estonia.com

Shift Design Shift Design Report Archive London: Shift Design, 2018 https://shiftdesign org Helsinki Design Lab. HDL Global 2010: Government Meets Design. Helsinki: Sitra – The Finnish Innovation Fund, 2010 http://wwwhelsinkidesignlab org

Sitra – The Finnish Innovation Fund. Strategic Design at Sitra: Lessons from Helsinki Design Lab Helsinki: Sitra, 2012

Van Alen Institute Van Alen Institute Project Archive Brooklyn, NY: Van Alen Institute, accessed 2025 https://wwwvanalen org

The following interviews have been anonymized and represent insights gathered by student teams through direct engagement with Public Policy Lab staff. Each section summarizes findings thematically, preserving tone and voice while ensuring confidentiality

Interview Findings: Team 1

Future Thinking Challenges

● Short-Term Focus: Current projects prioritize immediate deliverables over long-term impact.

● Capacity Limitations: Staff already feeling overextended, making it difficult to add future-focused activities.

● Government Partner Constraints: Public sector partners often limited by political cycles, bureaucracy, and risk aversion

● Conceptual Approaches: Debate about best approaches to future thinking corporate-oriented methods versus more community-centered alternatives

Key Pain Points

● Timeline Constraints: Approval processes taking longer than scheduled, creating bottlenecks between phases

● Resource Allocation: Insufficient time allocated for certain phases, particularly synthesis and co-design.

● Partner Management: Misalignment between organizational process and partner expectations/needs

● Early Phase Overload: Too many stakeholders involved in early phases ("too many cooks")

● Communication Gaps: Team members often unaware of processes or expectations.

● Synthesis Challenges: Limited time to process large volumes of qualitative data.

Organizational Dynamics

● Hierarchy: Clear role progression from intern to lead, with distinct responsibilities at each level.

● Interdisciplinary Approach: "Everyone should do everything but everyone has their own niche."

● Project Lead Responsibilities: Maintaining partner relationships, setting strategic direction, delegating work

● Internal Conflicts: Differing perspectives between senior staff requiring negotiation by project leads.

Partner Relationships

● Power Dynamics: Different approaches needed based on partner's position in their organization's hierarchy.

● Varying Receptiveness: Senior-level partners generally more open to future-oriented work than operational staff

● Adaptation Requirements: Need to understand partner constraints and adjust processes accordingly

● Partner Typology: Different categories of partners based on their understanding of human-centered design, relationship history, and decision-making authority

Potential Solutions

● Dual-Time Approach: Balancing immediate project needs with longer-term strategic thinking.

● Process Flexibility: Adapting the Release Model based on project type and partner needs.

● Celebrating Long-Term Impact: Creating visibility for work that contributes to future goals

● Structured Future Thinking: Integrating specific future-focused activities at strategic points in the process

● Cross-Team Collaboration: Workshop approaches to redesign processes based on different team perspectives.

● Partner-Specific Strategies: Tailoring communication and engagement based on partner characteristics.

Interview Findings: Team 2

Challenges Faced at PPL

Time Constraints & Prioritization

● Teams must balance quality work with tight deadlines

● Decision-making is crucial: what must be done vs. what would be nice to do.

● Learning PPL’s processes while executing projects can be overwhelming, especially for newcomers

“I do think that maybe the hardest part about future thinking for projects is that, like I think we're even beyond capacity trying to deliver what ACS wants us to deliver in Research Summary

this project, specifically So it's like I would not even dare to add a future thinking task to my team, because we're already, like, doing 10 different directions.”

● Employees join PPL from various professional backgrounds.

● Even with structured training, real understanding only comes from hands-on project work.

● New hires must adjust quickly to PPL’s standardized processes while meeting project deadlines

● Uncertainty in new project acquisitions makes staffing complex

● Moving people between projects disrupts workflows.

● Ensuring the right skill sets align with project needs is a constant challenge

● Many projects lack built-in long-term planning components.

● Future recommendations are often provided but rarely implemented by agency partners

● Limited partner resources and competing priorities hinder the adoption of future-focused strategies.

“Depending on how high they are on the layer cake, if you’re more senior, I think that there’s actually more appetite for future forward work.”

● PPL members have commonly expressed that the work environment and engagement with team members is what they enjoy the most about their roles.

● Hierarchy is not established; however, there is still a structure that goes from Fellow to Analyst to Senior Analyst to Lead to Senior Second

“One of the great pleasures of working in a public sector context, is that fundamentally everyone you're working with is motivated, or you know, the vast majority of people are motivated by an actual desire to do good in the world. When you show up saying, we have a methodology that we think will make it easier, more effective, more satisfying to be able to do Good people are inherently interested That's why they care about their work."

● AI usage at PPL is minimal, mostly for early-stage design visualization

● Hesitancy around AI stems from its focus on averages, while PPL values unique individual experiences

● Brendan sees potential for AI/machine learning but also acknowledges risks, especially for human-centered design with disadvantaged communities.

● One reason for his departure is the limited role of AI and quantitative methods at PPL

● Explicitly Integrate Futures Thinking into the Release Model: Revise the model to include structured long-term planning exercises at key milestones

● Dedicated Future-Focused Projects: Position PPL to take on projects centered around futures research and scenario planning.

● Aligning Partner Expectations with Long-Term Thinking: Make future-oriented planning a formal deliverable rather than an optional recommendation.

● Resourcing & Project Staffing Adjustments: Develop flexible staffing pools that allow for smoother transitions between projects Build predictive hiring models based on projected project acquisition trends.

“But I think, I think if it was embroiled in the PPL process in a way where I could justify taking that time and money to do that. I think it would be easier to enforce it. But right now, it's kind of like futures is something that I know PPL is really thinking about and really wants to do, but in a project like mine right now, that's like that that bumps it down whenever there's 1000 emergencies and handling so I if we were to able to say to a partner, like, when we start this project, we are going to do some futures thinking and, like, this is what it looks like, and this is baked into a project, and we do this with everyone, I think it would be a lot easier.”

"We just started making future time frame solutions that we are delivering along with the current time frame solutions. At first, no one would be asking for those, but no one was asking for human-centered social services until we built a market "

This appendix synthesizes Team Nebula’s qualitative research, drawn from interviews, shadowing, and synthesis activities conducted with members of the Public Policy Lab The findings below represent the voices and perspectives of PPL staff across roles, anonymized for confidentiality but preserved in tone and intent

At PPL, roles are fluid; team members regularly shift between tasks, drawing on varied skill sets regardless of title While this creates space for personal growth and diverse contributions, the fast-paced nature of projects often limits time for deeper exploration or reflection.

“We’re agile in how we work, but the deadlines don’t bend with us ”

Despite good intentions, creative energy can be compressed under delivery pressures, leaving little room to process, pause, or future-plan.

Many team members spoke about balancing passion with pressure. Staff often juggle multiple responsibilities, and periods of “stacked timelines” can be emotionally and mentally draining

“There’s only been one time where I caught myself working at night, and I was like, what am I doing? Close the computer”

This speaks to the personal boundaries many try to uphold, even as work intensifies

Shared language is seen as a foundational pillar within PPL Phrases like "release model" and "futuring" aren’t just procedural they shape how team members understand and align with each other’s work However, for newcomers, this internal vocabulary can initially feel opaque

Language, when used intentionally, helps bridge experience levels and build common understanding across teams

A standout feature of PPL is its commitment to cultivating a thoughtful, caring workplace. Informal rituals, like “PLLunch” or impromptu learning moments, help create a sense of belonging across hierarchies.

“It’s actually a learning environment There’s a lot of space to grow, to ask questions, and to not know exactly what you’re doing and that’s okay”

While there’s widespread interest in embedding futures thinking into project work, it often takes a backseat to immediate delivery needs. Staff expressed that it’s not due to lack of value but rather a question of timing, resources, and partner expectations

Artefacts, speculative tools, and research prompts are beginning to emerge as ways to surface future-oriented conversations, but they remain largely informal or individual-led

“We’re starting to deliver future-frame solutions even if no one asks for them, just like we did with human-centered design years ago.”

● PLLunch – Strengthening Team Connections: Encourage informal spaces for staff to build empathy and community across teams and roles

● PLLearning – Upskilling & Growth: Integrate continuous learning moments into the workweek Create pathways for staff to experiment and grow, both within and beyond project scopes

● Artefacts – Embedding Futures Thinking: Make space for speculative practices as part of the process Use artefacts to explore alternative futures and engage partners in long-term thinking.

● Build structured moments for futures thinking into early phases like scoping and synthesis

● Recognize and support invisible labor especially emotional care, partner relationship-building, and internal knowledge transfer

● Clarify and share internal vocabulary to strengthen onboarding and alignment.

● Focus on quality over volume, allowing reflection and abstraction to support deeper, more sustainable outcomes