15 minute read

Sub-Saharan Africa: can downstream move up?

Contributing Editor, Nancy D. Yamaguchi, explains why there is emerging hope for the downstream sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, despite the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sub-Saharan Africa has a signifi cant petroleum industry, revenues from which are a mainstay to government budgets. Countries across the region have worked to attract investment for upstream and downstream development. Yet many projects now are in stasis, set back by the COVID-19 pandemic. It has grown more challenging to regain momentum and attract investors. The pandemic has proven far more long-lived than nearly all forecasts anticipated, and there is constant concern that variants will continue to emerge and threaten populations. Many countries remain locked in battle with the disease. Oil production has fallen, oil reserves have fallen, demand has fallen, and refi nery throughput has fallen. Yet a reversal may be on the way.

As this article is underway, many major markets are re-opening their economies, and there are forecasts of severe winter weather and a natural gas crisis in the northern hemisphere. These factors are strengthening fuel prices. Indeed, many consuming countries called upon the OPEC+ producers’ group to ramp up oil production and ease prices, hoping that cheap energy would shore up their economies. Nonetheless, when the OPEC+ group met recently, it decided to stick to its already agreed-upon programme of gradual relaxation of production cuts. This will amount to an additional supply of 400 000 bpd per month beginning in August 2021 and extending at least through April 2022. Without the prospect of additional OPEC+ supplies, oil prices have risen considerably, hitting seven-year highs, with Brent crude prices back above US$80/bbl.

In the near-term, this will boost revenues for Sub-Saharan Africa’s oil producers, but perhaps create additional economic woes in import-dependent countries. Given the cyclical nature of the oil business, it is always possible that price spikes will cause demand to slump again, which in turn will force prices down. For the time being, however, global demand is recovering, as are prices.

This article focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa, which crosses the continent from west to east, stopping short of the Southern Africa region. Most of the countries in this area possess oil resources, at varying levels of development. Most of the countries have refi neries, though some have suspended operation. There are refi nery construction and modernisation projects underway or planned. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, however, the Sub-Saharan petroleum industry faced unique challenges to development. Some of the oil-prospective

Sub-Saharan Africa’s downstream sector

Declining utilisation and margins

areas are landlocked and in diffi cult terrain, while some are offshore. Fuel markets are usually small and often far fl ung, affecting refi nery economies of scale. Gaining access to markets may also require country-to-country negotiation so that resources can cross national borders, where there may be civil strife. Hope remains, however, for oil sector development and refi nery construction and modernisation. Can the downstream sector begin to move up?

A drop in oil demand

Most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa import petroleum fuels. They serve as important markets for export-oriented refi neries, some of which rely upon these external markets to keep their own refi nery utilisation rates high. Net-importing countries often wish to develop and/or expand domestic refi ning industries. Governments tend to equate a domestic refi ning presence with some modicum of supply security. Moreover, an in-country refi nery can serve as a focal point for other industrial and economic development. It can also help a country capture value-added if domestic crude oil and other feedstocks are available.

Domestic refi neries typically fare better if there is a solid base of domestic fuel demand. As Figure 1 illustrates, however, the year 2020 brought a sizeable drop in demand. In Western Africa, demand fell from 647 000 bpd in 2019 to 535 000 bpd in 2020, a drop of over 17%. Eastern African demand fell from 816 000 bpd in 2019 to 726 000 bpd in 2020, a drop of 11%. Central African demand fell from 232 000 bpd in 2019 to 202 000 bpd in 2020, a drop of nearly 13%. Central African demand already had been in decline since 2014.

Economies appear to be pulling out of the COVID-19 slump, and most international agencies now expect oil demand recovery. Rates of recovery will vary considerably, however, and the pandemic is not the only factor at play. In Kenya, for example, gasoline, kerosene and diesel prices were subsidised earlier this year in response to consumer complaints about the high cost of living. But the expense was too high, and the government recently ended the subsidy, causing prices to surge – along with consumer anger. Fuel pricing policies vary widely in Africa, adding complexity to demand forecasting.

Most of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have refi ning industries, and many have goals to expand, modernise, and build anew. This has been challenging, because outside of Nigeria, few markets are large enough to warrant a large refi nery that can capitalise Figure 1. Drop in oil demand in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2000 – 2020 (‘000 bpd), on economies of scale. As (source: BP). illustrated in Figure 1, oil demand in Middle Africa was 202 000 bpd in 2020. It is rare to fi nd sophisticated refi neries of under 100 000 bpd, or even under 200 000 bpd. Technically, therefore, one or two refi neries with the correct downstream confi guration could supply this entire region. However, that may not mesh with development goals among the individual countries. Each might desire its own refi nery, and internal fuel delivery infrastructure may be inadequate to allow a single regional refi nery to service a large area. Eastern African demand was 535 000 bpd in 2020. The largest submarket, Western Africa, had oil demand fall to 726 000 bpd in 2020. Nigeria is the key centre of demand and refi ning in this region, and its plans are discussed in more detail in a following section of this article. Outside of Nigeria, Sub-Saharan refi neries are small to medium in size, and they have simple confi gurations. Some have very low utilisation rates, and some have ceased operation altogether. For example, Chad’s refi nery is not operating, and Kenya’s refi nery was converted to a product terminal. Even though many of the demand centres are small and scattered, Sub-Saharan Africa is considered a growth market for fuels, and international traders view it as an important outlet. This has intensifi ed interest within the region to complete local refi nery projects geared toward satisfying domestic demand. Refi nery investment is seen as risky in today’s climate, however. African refi nery utilisation rates are low and have been falling. Figure 2 compares African refi nery capacity with throughput, calculating the rate of utilisation. Refi nery utilisation has been trailing down for the past decade, and it dropped to an anemic 55% in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic crushed refi nery margins around the world, as mandatory stay-at-home orders caused demand to plummet. Figure 3 displays quarterly average refi ning margins from 2017 through 2020, as calculated by BP. Margins around the world already were dropping by 3Q19, and the declaration of global pandemic sent them into freefall. Singapore’s medium sour hydrocracking margins went into negative territory in 1Q20 and remained submerged all year. Northwest European light sweet cracking margins dipped to -US$0.74/bbl in 3Q20 before recovering to US$0.82/bbl in 4Q20. US Gulf Coast medium sour margins remained the most competitive, but they too went negative in 2Q20. Although refi nery margins began to recover by late 2020, they remain depressed.

Additions to refinery capacity

Maintaining throughput and profi tability has been a continual challenge for Sub-Saharan refi neries. Nonetheless, some countries and companies remain committed to creating a successful refi ning industry, in some cases by replacing antiquated equipment with more modern facilities. OPEC recently published its ‘World Oil Outlook 2045’ in which it forecasts the addition of 1.2 million bpd of new crude distillation capacity in Africa between 2021 and 2026. Over half of this is accounted for by the 650 000 bpd Dangote project in Nigeria, which OPEC assumes will be completed in 2022. There are smaller projects in Nigeria, Angola, and Ghana. These additions include prefabricated modular units. OPEC states that these projects will increase the use of local crude oil and reduce the requirement for refi ned product imports. For OPEC+ countries cooperating in the production cut agreement, this may have the added advantage of taking some exported crudes off the international market, though naturally, if the global crude market remains oversupplied, this would merely shift the oversupply to other regions. Nonetheless, it will allow African producers to capture some value-added from processing domestic crudes.

Looking briefl y at Angola and Ghana, Angola has one refi nery at Luanda, owned and operated by Sonangol, the national oil company. Sonangol lists the capacity at 2.8 million tpy, or approximately 57 000 bpd. The refi nery runs at low utilisation rates, and the country imports refi ned product for most of its domestic needs. Angola planned to build two new refi neries in the cities of Lobito and Cabinda. The plan for a 200 000 bpd refi nery at Lobito was shelved. Sonangol is still pursuing the Cabinda refi nery plan, particularly since the country suffered severe fuel shortages in 2019. OPEC forecasts include new capacity in Angola coming onstream between 2021 and 2026.

Ghana’s Tema refi nery, commissioned in 1960, has a nameplate capacity of 45 000 bpd. This refi nery has run intermittently for years, often unable to secure credit for a steady supply of crude feedstocks. It underwent a revamp that should have increased capacity to approximately 49 000 bpd and added a residual oil catalytic cracker (RCC.) But maintenance was neglected for lack of funds, and the facility has deteriorated. General shutdown and maintenance were skipped in 2011, 2013, and 2015. An explosion shut down the refi nery in 2017, and another forced shutdown occurred in January 2018, just weeks after it re-opened. The government is planning a new refi nery to replace the Tema refi nery, envisioned as a 150 000 bpd plant. OPEC forecasts include new capacity in Ghana coming onstream between 2021 and 2026.

Figure 2. Africa refinery capacity and throughput (‘000 bpd) and utilisation rate (%), (source: BP).

Figure 3. Decline in regional refining margins (US$/bbl), (source: BP). Nigeria: the potential game-changer in the West

Nigeria is the region’s main refi ning centre, and it is poised to take an even more dominant role. Nigeria has four refi neries: Port

Harcourt I, Port Harcourt II, Warri, and

Kaduna. Three are cat cracking refi neries.

All four have catalytic reformers for octane provision, and two of the cat crackers have associated alkylation units.

Nameplate capacity is approximately 445 000 bpd, but utilisation rates are low (sometimes below 20%), and there were reports of utilisation dipping to 8% recently. The refi neries have fallen into disrepair. Moreover, at times they are starved for feedstock because of pipeline sabotage and theft. The Nigerian National

Petroleum Corp. (NNPC) sought private partners to revamp the refi neries, but market conditions have been discouraging, and modernisation has not been possible. Nigeria has grown

increasingly dependent on imported fuels, which frustrated many citizens who believe an oil-rich country like Nigeria should be able to meet domestic demand. A 1000 bpd modular refi nery was upgraded to 10 000 bpd in November 2018. Three additional modular refi neries are planned. There is also the potential for two condensate refi neries of 100 000 bpd each.

Any plans to revamp existing refi neries now may be swept aside by the massive Dangote Project. This will be the largest refi nery complex in Africa. The plan is ambitious, and it has been designed to avoid the pitfalls faced by other African refi neries (including small size, lack of technical sophistication, unreliable feedstock supply, and lack of secure infrastructure). Instead, the Dangote Project has been designed as an integrated petrochemical-refi nery complex. The complex will also produce fertilizer and polypropylene. It includes a massive 650 000 bpd refi nery, equipped with mild hydrocracking, residual oil catalytic cracking, alkylation, and ample hydrodesulfurisation capacity. The project team set a world record in December 2020 when it installed the world’s largest crude distillation tower. The crude tower was built by China’s Sinopec, which reported the size at 112.56 m long x 12 m dia., with a weight of 2252 t. It took several months at sea to deliver the tower, with two vessels failing along the way and a third needed to fi nally deliver the tower.

The Dangote Project is located east of Lagos in the Lekki Free Trade Zone. The presence of such a major facility is expected to have multiple knock-on effects, stimulating other development. The Dangote Group states that the project will create nearly 35 000 jobs in the Lagos area. The Lekki FTZ has a Phase 1 Master Plan to build a residential district in the north, accommodating 120 000 people, an industrial district in the middle, and commercial trading, warehousing, and logistics district in the southeast. Eventually, the government’s goal is to convert the entire Lekki Peninsula into a ‘Blue-Green Environment City.’

The Dangote refi nery originally was slated to begin production in 2016. The location was changed to Lekki, and construction did not begin until 2016. Completion was rescheduled for 2018, then 2019, then 2020. The construction team faced diffi culties when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, including supply chain hold-ups impacting the import of steel and other construction materials. However, the group had already taken actions to keep the project moving even before the pandemic hit. A fortuitous example was the company’s decision to bump up the construction of on-site houses. Originally, the plan called for 25 000 houses, but the group raised this to 45 000 houses in case there were construction hold-ups and additional workers were needed. When the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown hit, the fact that there were so many workers already in residence helped reduce the risk of infection. It reduced commuting in and out of the site. The Dangote Group now reports that the refi nery will be completed in 2022. Some market analysts believe that 2022 will bring only partial refi ning capability, but nonetheless this will be a sizable achievement.

When the Dangote Project is completed, Nigeria should be fully self-suffi cient in refi ned product, and it will be able to

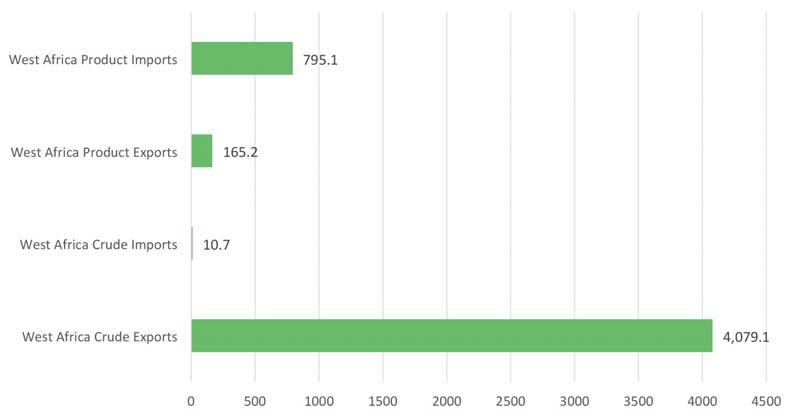

Figure 4. West Africa oil trade, 2020 (‘000 bpd), (source: BP). export fuel to neighbouring markets. At that point, the fate of the existing refi neries will grow more tenuous, and some capacity may be scrapped rather than modernised. Dangote’s fuel output will conform to EURO 5 quality standards, which the government has emphasised will help combat air pollution in metropolitan areas. The design specifi cations call for output of an impressive 314 000 bpd of gasoline and 94 000 bpd of diesel. To place the Dangote Project’s output in perspective, Figure 4 presents West African crude and product trade in 2020, as calculated by BP. In 2020, West Africa exported 4 079 000 bpd of crude and imported 11 000 bpd, for a net export fi gure of approximately 4 068 000 bpd. West Africa exported 165 000 bpd of refi ned products while importing 795 000 bpd, resulting in net product imports of approximately 630 000 bpd. While there will always be some in-and-out trade, the 650 000 bpd Dangote Project could entirely wipe out the need for West African product imports and create an exportable surplus.

Conclusion: downstream working to head back up

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Sub-Saharan Africa’s oil markets hard, cutting into demand and forcing already-lacklustre refi nery utilisation rates and margins down even further. Across the region, refi nery projects were postponed or cancelled outright. Many refi neries were sorely in need of upgrades and modernisation, but conditions never emerged that warranted the investments. Ultimately, most countries grew increasingly reliant on imported fuel. The coming year may change this for Nigeria and its neighbouring market outlets. Nigeria’s Dangote Project is unique. It is the only mega project underway that will integrate refi ning and petrochemicals. When completed, this project will meet all of Nigeria’s fuel requirements and allow exports to many neighbours. The global and local economies are not fully recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic, but Nigeria is showing confi dence in the future by pressing forward with a state-of-the-art industrial complex that will satisfy domestic needs and allow it to expand its presence in product export markets, likely to focus on the Sub-Saharan zone. When in full operation, the Dangote Project should be suffi cient to transform the entire West African region into a net product exporter. In Nigeria at least, downstream has been down, but is heading back up.