10

10 The fault in our crops - Growing too much of one, none of another

14 Another one bites the dust

19

19 Provincialization of electricity distribution companies Ammar Habib

21 It’s takes two to tango Zafar Masud

25

25 How the two and three wheeler industry, not cars, became the hallmark of Pakistan’s automotive sector

31 Pakistani lawn makes the fashion dream come true, but is it worth it?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

How chai and sutta went from guilty pleasures to pricey indulgence

Asingle cup of chai costs Rs 50 now. If a person consumes three cups a day, every day, the number multiplies to Rs4,500 a month. In a country where the minimum wage is Rs15,000, tea drinking can consume a whopping 30pc of income.

Once considered a small pleasure of life, the quintessential ‘chai ka cup’ made with tea leaves, sugar, and milk is quickly becoming a luxury. And it isn’t the only guilty pleasure that is fast evading the pockets of most people. Back in February this year, the tobacco industry was jolted when a huge increase in duties on cigarettes resulted in the product becoming more expensive by as much as 250% overnight.

While the more expensive imported cigarettes have gone far out of reach, even the cheaper local brands are selling at around Rs 11-12 per cigarette. That means for a person smoking five cigarettes a day, the bill comes out to around Rs 55 a day. This adds up to Rs 1650 a month, giving a ‘chai-sutta’ bill of just over Rs 6000 a month — which is nearly half the minimum wage in Pakistan.

So how are the manufacturers of these everyday pleasures that have turned into luxuries responding? On the one hand there is tea. Not grown in Pakistan, almost entirely imported, and with a uniquely inelastic demand the product will see no respite in prices since it has to be brought in from abroad. Meanwhile cigarettes are an entirely different game. Pakistan produces most of its own tobacco and at very high yields, yet the prices of cigarettes going up have to do entirely with levies and sin taxes. Profit explores.

Right before Ramazan the price of black tea (loose) had swelled to Rs1,600 per kg from Rs1,100 thanks to curbs being put on imports in the

country. So why did prices of tea skyrocket by more than Rs 500 per Kg and are expected to continue to be affected by inflation after Ramzan?

Pakistan, unfortunately, barely grows any of its own tea and is in fact the world’s largest importer of tea spending $596 million on it last year. Meanwhile, India produces 0.94m tons of tea a year, consuming 70% of it domestically. Our story begins in 1813, when England’s parliament restricted the powers of the East India Company. The company had a monopoly on growing tea in China and had discouraged its production in India. This changed once the English government took a more direct interest in India.

In 1834 India’s first governor general, Lord Bentinck, formed a committee to submit “a plan for the accomplishment of the introduction of tea culture and growth into India.” The British hoped they could increase their production of tea by growing it in India as well as China.

Assam was the first area to be devel-

oped, followed by the Himalayan foothills in 1842, the Surma valley in 1856, and Darjeeling in 1858. This rapid rise was testament to the ingenuity of the British colonisers, who settled major wastelands for the cultivation of tea-gardens.

This ingenuity, however, came at a grave cost to local communities. The project was undertaken with the express purpose of encouraging foreign enterprise. Barriers to entry such as not giving a grant of less than 100 acres kept local communities from benefitting.

By 1949 India was producing a total crop of 600 million pounds annually, nearly half of which was being exported to England. Now, up until 1971 a lot of the domestic tea consumption in Pakistan was met by tea farmers in East Pakistan. However, with the independence of Bangladesh Pakistan was suddenly a country that grew tea nowhere, but had a population that was hooked on the hot drink. So what did they do?

Pakistan simply started importing tea from India and Sri Lanka. The substance was cheap and not a major strain on the import bill. The first attempt to grow tea was made in 1982, when Chinese experts reported the hilly terrain of Mansehra would be ideal for tea-gardens.

Since then, however, progress has been slow and in the past decade down-right regressive. Tea was first planted in Mansehra in 1986, and then in 2001 in Swat both by the government and private companies. At its peak, Pakistan was growing tea on nearly 900ha.

However, currently this is limited to an area of 100 ha under Unilever Brother Support in Mansehra. The issues have been typical. In the initial days, the government was providing

support like free nursery plants to encourage growth. As soon as the schemes ended, interest died out too.

Tea is a difficult crop to grow. In their natural state, tea trees have been known to grow to heights of 70 feet. When planted in fields, they rarely reach over four feet, making tea-gardens a vast forest of miniature trees. And these trees have a 5-year maturation period.

This makes them an unattractive prospect for farmers. Tea farming proved to be unprofitable because the price of plucked leaves (raw material for black tea) at Rs 46/ kg is much higher in Pakistan than that in the international market i.e. between Rs 20-22 per kg.

Pakistan could have become competitive with the international prices by growing more. Research has shown there are 64000ha of land in the country ripe for tea production. This with value addition and cost reducing measures across the value chain would have made a big difference.

Now, as a macroeconomic crisis brews in the country and Pakistan is cash-strapped for dollars, there is an acute realisation that these are very much products that we should

be growing ourselves.

In 1947 no tobacco was grown in Pakistan. Today, Pakistan has one of the highest per-area tobacco yields in the world and is a major producer. For decades, despite this initial lag, cigarette manufacturers thrived while growers have gotten the short end of the stick. But this year the script has been flipped.

The tobacco sector has been at the hit list for the government’s increasingly higher revenue collection needs, by paying higher taxes. A fresh massive strike of around 153 percent Federal Excise Duty (FED) rates on cigarettes in February caused around a 250 percent increase in the prices of cigarettes, produced by legitimate companies.

As a result, the country’s largest cigarette manufacturer claimed that smuggling of cigarettes has increased by 39% in just two months since the government raised an estimated 154% in Federal Excise Duty (FED) on cigarettes. The effects of this hike trickled down to taxes, causing a major hike in cigarette taxes, jolting Pakistan’s legitimate tobacco industry. As a consequence of cigarette prices hitting the roof, the tobacco

market has been flooded with over 70 new brands of cigarettes during this short span of just two months.

Of course, this claim is not as simple as that. You see, there is a very strange stand-off between large cigarette producers like British American Tobacco and local producers in Pakistan. On the one side are the big-boys of nicotine, the two multinational cigarette manufacturers that control nearly 90% of the country’s tobacco consumption market share. And on the other are more than 50 smaller companies. All local, all willing to scrap, and all a constant thorn in the back of the multinationals.

At the centre of this battle between evil and evil are vast swathes of fields in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa where tobacco is grown. Tobacco is grown in all four provinces in Pakistan, but it is predominantly grown in KP where it is a major part of the local agrarian economy. KP’s provincial economy is pegged majorly to the growth of tobacco. More than 80% of KP’s population lives in rural areas, with agriculture accounting for around 30% of provincial GDP. Pakistan currently grows tobacco on some 50,800 hectares, with KP making up nearly 30,000 of these hectares.

It is one of those rare agricultural products where Pakistan is ahead of the curve. Over the more than 50,000 hectares on which tobacco is grown, Pakistan’s yield per hectare stands at nearly 2.3 tonnes per hectare with a total production of 113.6 million kilograms. In comparison, the world average production for tobacco is 1.84 tonnes per hectare. Meanwhile, KP in 2021 produced 71.38 million kilograms on 28,089 hectares of land, giving an average yield of 2.5 tonnes per hectare — a 66% rise on the global average.

The first efforts to grow tobacco in Pakistan came with an experimental 20 acre farm in 1948. Here it was discovered that KP was an ideal area for the cultivation of tobacco.

Tobacco is lethal. Of the eight million deaths that occur globally each year due to tobacco use, 170,000 are in Pakistan — to put it into perspective, the total deaths from Covid-19 in Pakistan were around 31,000

Dr Zaffar Mirza, former SAPM on Health

Farming began quickly, but the crops were low-quality and only used by local cigarette manufacturers.

The biggest tobacco company at the time, British American Tobacco, still had to import tobacco to manufacture cigarettes. Things really took a turn in 1968 with the establishment of the Pakistan Tobacco Board entrusted with promoting and developing tobacco production and export.

In 1969, Philip Morris International established itself in Pakistan, bringing with it both research and development for the tobacco crop and increased competition. As a result, tobacco started being grown on more land, but even more importantly, the per-area yield rose.

Yield in KP increased from 43,408 tonnes in 1980 to 71,410 tonnes in 2020, while the area under cultivation only rose by 4,000 hectares in that time. This means that while the area under cultivation grew by around 16%, the total production rose by a comparative 65%.

Clearly this means Pakistan has great potential as a tobacco exporter. Tobacco exports stood at $55.94 million during 2021. Even though our per-area yield is high, to increase the export numbers we need to grow tobacco on more land to have enough volume to be a major exporter.

For that to happen farmers need to be making money. Tobacco farming has historically been profitable, but the end benefit does not always go to the farmers. Cigarette manufacturers buy green leaves at cheap rates from the farmers and then process them into smokeable tobacco.

On top of the low rates for these green leaves, tobacco farming requires a lot of expensive inputs such as fertilisers, labour, mechanical power, pesticides etc which discourages existing farms from expanding and new farms from being set up.

This is where things get more interest-

ing. There is definitely a case to be made for more areas being used for tobacco cultivation. However, the problem will not be fixed until the farming of tobacco leaves becomes profitable. One of the biggest impediments to this is how the tobacco industry in Pakistan works.

There are two MNCs that operate in Pakistan. One is the Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited (PAKL), which is the Pakistani subsidiary of British American Tobacco. The other company is Philip Morris Pakistan Ltd (PMPK). Together, these two internationals control 90 percent of the market. They also pay 98 percent of the tax that is collected from this industry. That is where a major contention exists between the MNCs and the local players.

The other 52 tobacco companies in Pakistan only pay Rs 2 billion in taxes every year. To put this in context, this is only 2% of the total tax collected from the tobacco industry. This means that there is stringent competition

between the two sides. So much so that the MNCs actually lobby for higher taxes that are more stringently imposed on the local growers and manufacturers. They believe that because they pay so much more tax while local producers do not, they have an unfair advantage. And at a time when these big companies are being taxed more than ever, the smuggling market and local markets will thrive at their expense.

Both of these are products that are here to stay. The unfortunate part is that we grow the product that is dangerous to human health while we do not grow the product that is not dangerous — even though we have the capability and resources to do so.

Ideally, we should be headed in a direction where tea is grown in Pakistan and cigarettes continue to be highly taxed as most forward-thinking tax regimes around the globe have done. In an op-ed for Dawn, former SAPM on Health Dr Zaffar Mirza claimed that the time was ripe for a heavy tax to be slapped on consumer items that have proved to be harmful such as tobacco products and sugary drinks.

“Such a measure would be good for public health and will support the ailing economy. Smoking is on the rise, and a cash-strapped Pakistan desperately needs revenue. The IMF supports such taxes and tobacco excises in Pakistan are way below the recommended global level. Tobacco is lethal. Of the eight million deaths that occur globally each year due to tobacco use, 170,000 are in Pakistan — to put it into perspective, the total deaths from Covid-19 in Pakistan were around 31,000,” he wrote. n

Tea is a difficult crop to grow. In their natural state, tea trees have been known to grow to heights of 70 feet. When planted in fields, they rarely reach over four feet, making tea-gardens a vast forest of miniature trees. And these trees have a 5-year maturation period

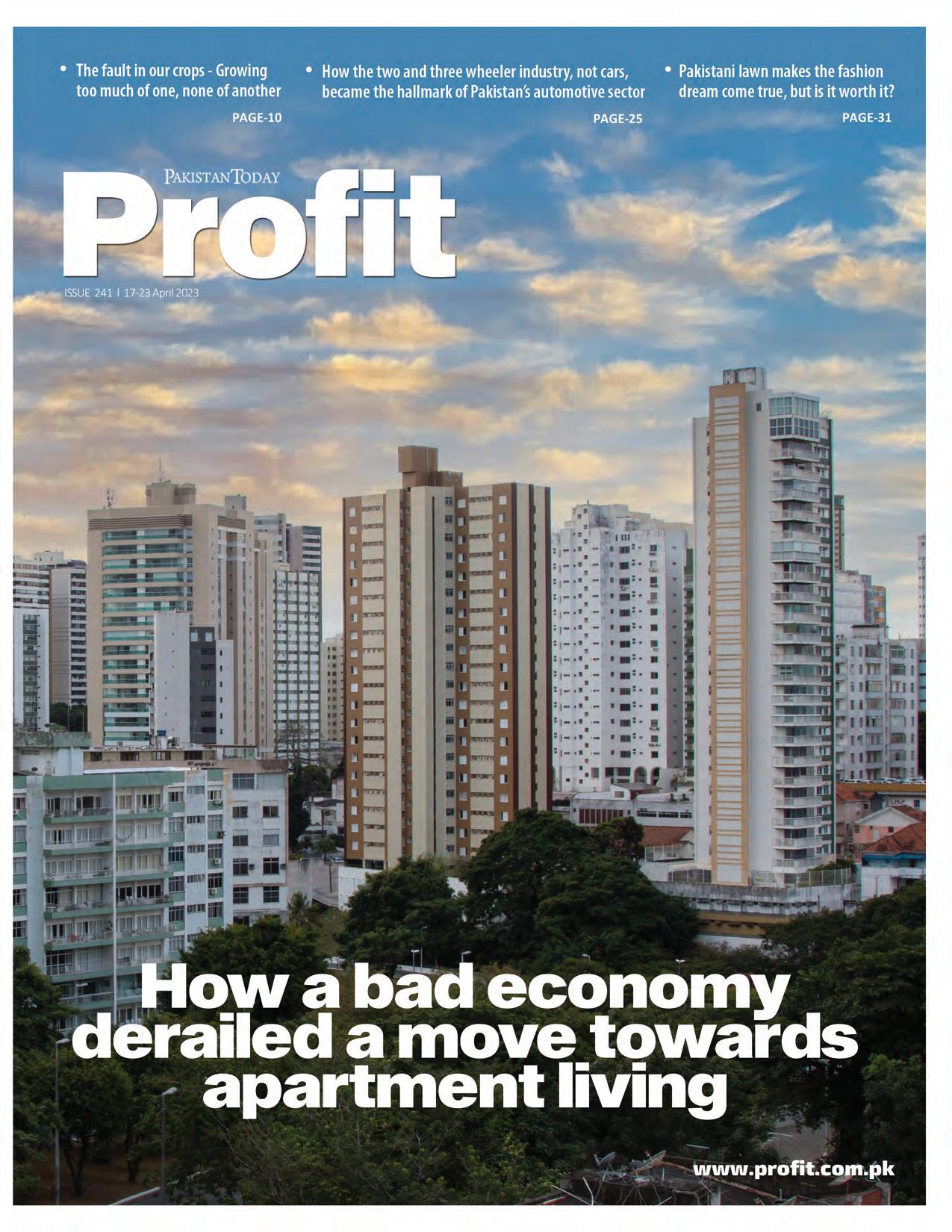

In terms of planning and infrastructure, barring Islamabad, Lahore is arguably the best developed urban centre in the country. Place the two cities in their context and it becomes clearer why this second-place is impressive. Islamabad had the benefit of being built on a blank canvas with the requirements of a capital city in mind. Lahore, on the other hand, is an ancient city that along with its heritage also brings its own baggage.

Yet over the past decade in particular, Lahore has undergone a major renovation that has made many parts of it quite unrecognisable. Central areas such as Gulberg have been transformed into ‘signal free corridors’ using u-turns, overhead bridges and underpasses. DHA has expanded considerably, finishing at least three new phases with residential and commercial properties that are well-populated and announcing several new ones, while Johar Town has become a city within the city. Most recently, Main Boulevard all the way to Cavalry and the DHA entrance have undergone massive renovations for the introduction of Lahore’s Central Business District where once the old Walton airport and Walton forest existed. With these improvements in road network, infrastructure and the urban sprawl that has accompanied it, population density has shot up as well. Going by the latest census (2017) Lahore has 6,284 people per sq. km. To add some perspective, Karachi has 3,944 people per sq. km.

It was inevitable therefore that someone got the idea to go vertical and around six years ago apartment building projects started springing up all around town. The idea behind the expected success of so many apartment buildings was the benefits it provided over conventional home ownership and how, like Karachi, perhaps Lahore was finally ready for apartment living. Profit did a detailed story on those upcoming projects back in 2017 detailing the economics and profitability of these projects.

In this article we won’t be taking a ‘6 years later’ look at those projects, rather present a thesis that in the current economic climate of high inflation and low GDP growth, apartments have become significantly expensive, at a rate much higher than that of conventional residential housing.

As per the 2017 census, Lahore is a city of 11.1 million people and on average has had an annual growth in population of around 4.07%

since 1998. Going by that average, Lahore will have close to 14.1 million inhabitants by the end of this year. This is of course a loose estimation at this point and can only be confirmed by the ongoing 2023 census.

According to a study published by the Urban Unit, a Project Management Unit (PMU) of the Planning and Development Department under Government of the Punjab, which is a detailed analysis of data on Lahore district, as published in the 2017 census, the annual increase in population is closer to 3.0%. While lower than other estimates, it is still higher than the national average of 2.7% for all urban areas.

While growing population is a concern, rapid urbanization is a much bigger worry, the report emphasizes. From 1995 to 2005 Lahore’s Urban areas grew by 4.3%, from 220 sq. Km to 336 sq. km. By 2015 it had grown to 665 sq. km, a 7.1% jump in the second decade. Estimates are that by 2025 urban Lahore will cover an area of 1,320 sq. km. The study’s land consumption analysis shows a worrying statistic: for every 1% increase in Lahore’s population, an extra 2.82% of land is consumed.

A shift towards incentivising developers to invest in high rise housing projects rather than horizontal expansion to arrest this rapid land consumption, began.

Five years ago, soon after the Lahore Development Authority (LDA) doubled the permissible height limits for residential apartment buildings, almost doubling it from 45 ft. (ground plus three floors) to 80 ft. (ground plus six floors), a plethora of projects were announced.

The sales pitch was also very straightforward: own a place in central Lahore by paying far less than what it would cost to own a house in the same vicinity. And although the projects varied when it came to features, two aspects of each project were almost universal. The location must be Gulberg (it doesn’t get more central than that) and the finishing of the apartments must be high end.

For developers, at least on paper, it made good financial sense as well. The major initial investment was the cost of land following which the selling became crucial as the installments from each apartment sold, spanning over 2-3 years, would be used to build the project. ‘All equity, no debt’.

Through our reporting back in 2017, we arrived at the conclusion that a fully delivered and sold project would generate 115% return on equity. That was then. Things have changed massively since 2017, in fact, even more so in the last two years, as the economy

tanked, inflation skyrocketed and the rupee depreciated to record levels.

The past two years have been brutal on most industries, real estate included. An astronomical rise in cost of production and a general climate of economic uncertainty has severely slowed down investment and economic activity. Additionally, a discount rate of 22% that is likely to increase further has made investors park their cash in 100%-capital-secured government-backed paper.

Therefore, developers with incomplete projects are facing a double whammy. Not only have they overshot their budgets, there is no demand for their apartments at the revised selling prices, which means they can’t generate additional funds as there are no fresh sales being made. Additionally, installments for apartments sold at 2021-2022 rates, on average 52% lower than current prices, are proving insufficient to finance construction.

“High rise luxury apartment projects are generally associated with installments and most of them involve investors’ money. Due to inflation, these projects became expensive and investors stopped paying installments, which resulted in developers halting construction”, explained Javed Iqbal, a property dealer in Lahore DHA area, while speaking to Profit

“For example, Defence Raya launched a project consisting of three high rise buildings two years ago. They had received half the installments, from launch to present day at a rate of Rs 22,000 per sq. ft. Owing to market conditions they were forced to increase this to Rs 28,000 per sq. ft. Construction projects across the country are facing a similar situation,” Iqbal added.

The main culprit in rising construction costs is steel. Between 2017, when most projects began, steel cost Rs100 per kg. By 2021 it had risen to Rs 125 per kg. However, rates in 2023 jumped to unimaginable levels, peaking at 325 per kg. Currently available at 285 per kg, owing only to a drop in demand, steel is still too expensive, costing 128% more than two years ago.

And it’s a somewhat similar story with other essential materials as well. In 2021, cement was going for Rs 700 per sack, which went up to Rs 1,030 per sack in 2022 and at present it is being sold in the market for up to Rs1,150 per sack. Plywood has gone up from Rs 1600 per cubic feet while this year it is Rs 2,400 per cubic feet while Diyar wood costs around Rs 12,00 per cubic feet as compared to Rs 8,000 a year ago.

Hasan Sami, a developer who is

constructing a high rise apartment building on Lahore’s Zafar Ali Road, told Profit that the prices of construction materials have increased by more than 100 percent in the last one year.

“When we made the feasibility of our project, the rate of steel was Rs 102 per kg, it is Rs 302 per kg now. Similarly, the price of a cement bag has more than doubled. As a result, our construction cost increased. Since we had an end-user focus when launching this project, as soon as prices of these materials increased we decided not to announce the sale of the project. Now that we have completed a lot of work, we intend to announce its sale in the next two months,” he said.

The CBD was launched by the Punjab Government last year to develop commercial real-estate in Punjab. The ethos behind the project was to use unused government land to develop a district within Lahore where commercial and residential real estate projects could be developed. And the style of all these buildings? High-rise. And not just apartment buildings, but business parks and high-rise office buildings too.

The problem for the CBD was, however, that the area in which they were developing this real estate is land-locked. That is why in November 2022, the CBD initiated the extension of the Kalma Chowk underpass. The project constitutes two parts: the construction of the CBD Punjab Boulevard and the remodelling of Kalma Chowk Underpass.

“The underpass serves primarily to facilitate the business district, by providing car access to landlocked property. Such infrastructure only benefits motor transport, that includes both cars and motorcycles”, says Raffay Alam, Pakistan’s leading environmental lawyer.

“The remodelling of Kalma Chowk Underpass has largely been proposed and implemented for the Central Business District. The project was planned for the former area of the Walton airport and plots were auctioned earlier this year. Part of the CBD’s plan was to provide direct access to major arteries such as Ferozepur Road and Main Boulevard,” says Dr Umair Javed, assistant professor of Politics and Sociology at LUMS.

Despite all of this, the CBD does to some extent help with the concerns many have had about Lahore’s reluctance to adopt high-rise development. And we are not just talking malls when we say high rise commercial buildings – we mean office buildings and business parks as well.

Why is this so?

The answer is very simple: Pakistan desperately needs thriving urban centres. Cities, after all, have an important role to play in the economic fortunes of the people that live in them. Pakistan’s urban population is currently 37% of the entire population, but it contributes a massive 60% to the national GDP. While those in the rural areas producing agricultural products are doing massively important work in terms of providing food security and producing actual products, there are so many in major cities in the service sector that are contributing to the economy. However, if they are to continue doing this effectively, they need to have comfortable living conditions, healthcare facilities, as well as recreational facilities. Similarly, for those people that want to set up businesses that will employ the people that want to work in the services sector, then they will need places to conduct their business, offices, and centres with friendly by-laws. That is essentially what the Punjab government wants to build with its ideas for central business districts.

“We need to give comfortable spaces to the urban population to work in. If we are to foster economic growth and activity, then we must encourage it. We need to provide a suitable ecosystem, and infrastructure to support people doing business,” says Imran Amin, CEO of the LCBDDA. “Our goal is to make Lahore a commercial economic city. The CBD in Lahore will definitely play a vital role in economic growth with attracting people seeking business and job opportunities. We do not want to limit ourselves to just providing office buildings and being done with it – a central business district in my conception provides exceptional business openings as well as offers effective working, living and playing spaces through quality urban design.”

Is this massive construction undertaking feasible currently? Be it a government-backed project like CBD or private high rise residential housing developers? Not really!

The fact of the matter is that multistorey structures require much more steel. For a typical apartment building’s gray structure, 50% of the cost is made up of steel. For residential houses, this figure is closer to 25%. Right off the bat, going by the increase in the price of steel since 2021, apartment building developers are looking at a higher per sq. ft rate to finish their gray structure. In absolute terms, in 2021 the per sq. ft rate for a highrise building’s gray

structure was around Rs 1600-1800. Currently this is at Rs 4500-5000.

As for residential housing, since they are using 25% less steel, gray structure cost has not shot up proportionate to an apartment building. Additionally, there is the consideration for timelines as well where apartment developers are again at a disadvantage. Building a 10-marla house in a posh area like DHA Phase 5 for example, will take between 10-12 months to complete and move into.

Comparatively, an apartment building with 6 floors and a basement will take up to three years to be complete enough for anyone to realistically move in. This opens up developers to all sorts of market risk, especially in an economy with such rapid price fluctuations. What is more, many of the finishing materials being used in the projects we have mentioned so far are imported making the finishing rate per sq. ft susceptible to rupee depreciation. Back in 2021, high end finishing would cost anywhere between Rs 2500-3000 per sq. ft. Currently this rate is around Rs 5000 per sq. ft. And these cannot be cut down by much. Developers are bound by what they’ve committed to customers at time of selling. Apart from sticking to the agreed per sq. ft rate of the sale, they have to deliver a minimum quality of finishing. They simply can’t ‘cheap out’ and deliver a substandard product. Not only would that be a breach of contract but also carries a reputational risk if they plan on remaining in the same business. However, one would assume, for many new entrants, this could be their first and last project.

Apartment building developers are therefore looking at a total construction cost that is upwards of Rs 10,000 per sq. ft. Add a pretty penny for marketing and miscellaneous costs on top, and the entire feasibility made two years ago becomes more or less redundant. Of course, if they are able to sell their units at the revised rates, then they’re still in the green, making the same margins and return on equity. But this is easier said than done. Demand is low.

The business of plot trading, house flipping and building homes for the purpose of selling to end users has also taken a beating, but a less intense one, as compared to apartment buildings. Not only is the gray structure cost less, as explained above, but the finishing cost is also much more manageable. Anyone building a house, either to sell in the market or for personal use, can always choose to use local finishing material over imported items in order to remain within budget.

There is the additional advantage of keeping one’s own timelines, more so for someone

building for themselves but also a seller, as he will only be able to market it once it is finished. Plus, the land is the developer or homeowners asset, and it will hold a significant amount of its value, even in the worst of market conditions.

This price differential is reflected in the numbers as well. A reasonably comparable house to a 3-bedroom apartment in Gulberg would be a 10-marla home in Phase-5 DHA (ground plus first floor, no basement). The total covered area would be around 2450-2500 sq. ft (1425 per floor), with an open area of around 370 sq. ft for a two car parking. The personally owned space for the apartment would be around 2150-2200 sq. ft. Add parking for two and a servant quarter; the covered area adds up to the same, give or take.

The following graph shows the price trend of finished and sold apartment projects in Lahore from 2017 to 2023.

Prices have steadily increased over the years but the severity of the hike between 2021 and 2023 is much less owing to reasons already mentioned above.

While there is an aspect of a slow and oversupplied market to this as well, with individual investors and home buyers waiting and watching for an indication of stability in the economy, an average buyer is definitely looking at prices with value in mind.

Imagine a family that has recently moved to Lahore, a couple with two kids, looking to buy a place, considering either apartment living or a ready to move into house in an upscale posh

a conservative estimate would be around Rs 33,000 per sq. ft, translating into a buying price of Rs 76 - 77 million.

Comparatively speaking, his research on a similarly sized house (the 10-marla comparison we mentioned above) will cost him somewhere between Rs 54 - 56 million.

With such a high delta between prices for an apartment and a ready to move into home, the choice should be quite clear. Right? Well, not really.

This is where personal preferences and a willingness to pay a premium for certain style and culture of living comes in. For the price sensitive types, it is a no brainer, but for a buyer who has perhaps lived the apartment life, moving from abroad or even as close as Karachi where it is much more common to own an apartment than a house, he might just cough up that extra cash.

But for the purpose of this article, our contention is that the apartment living culture in Lahore that was all set to take over the housing market, will have to wait until the economics of it all start making sense again. And this has already begun.

Apart from incomplete project onhold or unsold inventory, sources in LDA told us that there are developers who have bought plots for the purpose of building apartments but have delayed plans, which is evidenced by the fact that the volume for approvals has gone down considerably in 2023 as compared to 2022.

In comparison, the price trend for 10-marla homes in DHA phase 5 shows less variance over the same time period. (Date from Zameen.com index pricing).

neighborhood. Their research for apartment prices will bring up something similar to the following:

Profit conducted the same research as a buyer. Although there are some outliers in this list with very exorbitant asking prices,

There is still a market for apartments, just a shrinking one, where selling will become very difficult and new projects scarce, at least for the foreseeable future. n

Pakistan has ten electricity distribution companies, nine of which are controlled by the federal government, while K-Electric is in private control. The ten electricity distribution companies cumulatively posted PKR 170 billion in losses for the year 2021-22, and consistently post financial losses. The same losses are eventually borne by national exchequer resulting in an ever expanding fiscal deficit. It is estimated that the most recent losses for electricity distribution companies made up more than 1.4 percent of the GDP of Pakistan.

As the fiscal deficit expands, the cost of the same is either borne by the taxpayer through increasing taxes (and at the cost of other social and development expenditure), and by the population of the country through inflation, as the state continues to print more money to bridge it's deficits eventually fueling inflation.

On average, the electricity distribution companies have distribution losses of 17.5 percent – which means that for every one hundred kilowatt-hour (unit) of electricity that is distributed by these entities, roughly 17.5 units are either lost due to inefficient infrastructure, or remain unpaid. The inefficiency eventually leads to higher electricity cost for the end-user, who has to pay an ever increasing cost for an inefficient infrastructure.

On a macro level, service delivery of electricity distribution companies is either spread over a city, or multiple districts, exclusively

within jurisdiction of a province. In such a scenario, a governance structure which is centralized at federal level leads to misalignment of incentives. As incentives are misaligned, reduction of distribution losses is not incentivized, the province does not have any control to improve service delivery, or reduce financial losses. As the financial losses are borne at federal level, the province does not have any skin in the game to improve efficiencies, and consequently reduce losses.

A transition from federal to provincial control would mean that the provinces will have to bear any potential losses, or participate in subsequent gains. The incentive to improve efficiency, and service delivery would be directly aligned with financial outcomes. A more efficiently run electricity distribution company would result in better outcomes on a provincial level, while also directly affecting the financial position of a province.

This will also relieve the federal government of heavy financial losses, which then be managed by the provinces through their own resources aligning with the spirit of the eighteenth amendment of the constitution, which calls for devolution of services from federal to provincial for better service delivery and outcomes.

A transfer of electricity distribution companies to provinces would initially entail a substantial reorganization, and restructuring effort. This would entail rightsizing of the workforce, which would be a politically tough decision. Inability to take such decisions would mean that even the first step towards revitalization of distribution companies would not be taken resulting in compounding of losses, which will now be borne by the provinces. To avoid such losses, it will be critical to revitalize the entities on a war footing.

The next step would be to invest in maintenance and development of distribution infrastructure which would require significant injection of capital. Provinces can take the public-private partnership route to develop infrastructure without entailing significant capital outlay from provincial exchequer. Provinces can also take the route of privatization, and push entities towards restructuring while having specific goal based efficiency improvement targets. Moving towards the same would require considerably tough political decisions, that will require availability of political capital of a provincial government.

The electricity distribution companies have been bleeding cash for more than a decade now, and continue to impose a heavy cost on the taxpayers, and the population of the country. Tough political decisions will be like a bitter pill that can solve the problem for the future and plug the losses.

Alignment of performance and eventually profitable operations with the financial performance of a province can unlock more efficient operations that add value for stakeholders across the board. The sovereign is already reeling under the stress of perpetual fiscal deficits, and significantly high energy costs. Improvement of governance of electricity distribution companies, and their eventual restructuring remains critical for enabling the country to get on track of sustainable growth, while improving outcomes and overall welfare of the country's population. n

These are unusual times where a more inclusive approach is needed between businesses and the banking community. These times surely pose unprecedented opportunities for both to do some introspection and repositioning for a more sustainable and mutually beneficial relationship. Working together more closely than ever before, looking at changing working protocols, and more so mindset, amongst themselves and at the same time at the policy level within the Government, is the way forward.

To begin with, let’s see what it takes in making Banking more effective for the Business Community. Perhaps, the most significant constituency relates to, “Engagement between Banks and Businesses”.

Knowing the specific needs of the target clientele, and tailoring solutions for those needs has always been one of the foremost priorities of financial institutions, or any frontend business for that matter. However, the uptake of digital solutions in the banking industry has necessitated a re-evaluation of customer outreach and marketing to retain or recapture growth, customer engagement strategies are now in need of revision across the board with more integrated systems/ technology-based solutions at the two ends.

In my view this state of flux, brought about by the democratization of technology, the advent of data driven insights, artificial intel-

ligence, and broad based digital marketing, should be taken as a blessing in disguise. It is an opportunity for Banks and businesses to fill the engagement-gaps of the past via new solutions, and it is a reminder of the importance of being proactive & responsive to changes in the landscape. To this end, data analytics is the answer.

This is the next invaluable component of this equation. Now, more than ever, there is a need to listen, and to provide solutions that will bring value that is pertinent, timely, and intuitive, by using customers’ channels of choice, be they digital or otherwise. And most importantly in this respect, empathy and authenticity are paramount. Engagement with clients should be focused on their needs (financial stability/wellness) as opposed to the financial institution’s desire for product sales.

Further deepening of the relationship between banks and the business community may be achieved via transparency, with respect to cost in particular, and the provision of information in general. Transparency is vital in facilitating accountability, in projecting a customer-centric approach, and in enabling clients to make informed decisions about their needs and who can best serve them.

Transparency and close communication, however, must swing both ways; business clients must be open and communicative with their banking partners as well. You may be familiar with the old adage, which I have modified slightly: the three professionals in your life from whom you should not hide anything now include your lawyer, your doctor, and your banker.

Insofar as the structural changes that I would like to see within the Banking sector over time, there are a few core aspects, at the policy level, that I would like to address in this context.

Firstly, the share of private sector credit shall increase with reduced reliance on financing the dominant borrower (i.e., the Government of Pakistan). While credit to the private sector in Pakistan has increased in absolute terms, it has declined as a percentage of GDP (17% in 2022, down from 29% in 2008). The reasons for this are multifaceted; the biggest impediment being government borrowing which swelled over 400% during this last decade. Another reason, on the demand side, remains Pakistan’s large informal sector. More disclosure and documentation by the businesses would lead to bridging this gap effectively.

Secondly, Banking in Pakistan, in a very basic sense, is a game of access to cheaper deposits, whoever has that is the winner. Therefore, it’s critical that the institutions having larger deposit holdings shall be able to divert these deposits to more productive, specialized areas. The constitution of the banking industry needs a review. Currently, it’s totally lopsided and concentration of assets and liabilities rests with a handful of large banks who literally, by default, drive the agenda

of the entire sector. This warrants a paradigm shift whereby broad-based funding could be diverted to more desired and unconventional sectors, like agriculture, infrastructure, etc., through out of the box thinking and programs, in collaboration with the central bank and the governments.

Thirdly, a shift from collateral/ asset based lending to cash flows may also be pertinent in this context. Under this model, a company borrows money against anticipated revenues/ cashflows expected to be actualized in the future, despite their asset-thin status, which is particularly relevant in the case of start-ups.

Finally, for the banking industry to facilitate the prerequisites of business community (or any other client with a specific set of requirements) is to increase specialization in the portfolio – in other words, Specialized Banking: the streamlining of financial institutions’ service offerings to cater to a client pool with a particular set of requirements in a more efficient way than what could be offered by a universal bank. And finally, one more way that Banking can be made more effective for the Business Community is through building necessary expertise at the industry level, by liaising closely with industry specialists, consultants, and business clients. Positioning plays a key role in this; financial institutions with the necessary expertise must emphasize this in their communications, such that they may differentiate themselves from competitors.

Let me conclude with the statement that a change in mindset is desperately needed in our society – that making money is not a bad thing. In fact, if anything, it’s a good thing as long as it’s done fairly and legitimately, with the intent of economic inclusivity.

If we look at the Muslim history, something very revealing comes up. In his book “Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism”, the famous author of biographies and history, Benedikt Koehler, claims: “Muhammad ibn Abdullah, Islam’s founder, was proud of his descent from Arabia’s most respected tribe, the Quraysh, who owed their standing to success in business rather than in battle. Muhammad even at the peak of his career was pleased when he heard praise for his own financial accomplishments; he smiled when his deputy Abu Sufyan ibn Harb complimented him, “you have become the wealthiest of the Quraysh!” Abu Sufyan’s fawning accolade was not empty flattery, far from it, because Muhammad by then earned annual rents exceeding ten thousand ounces of gold (in today’s terms, commensurate with several million dollars).

Muhammad was the richest Arab of his time.”

My ultimate message is that, as a society, we need to be more mature and realistic in our stance towards businesses and businessmen. We need to respect them and their efforts in contributing towards the economy. We need to support them and look at them with a positive lens rather than sighting them with negativity and with the stance that there’s something seriously wrong with making money, per se. On the other hand, of course, businesses and businessmen have to act responsibly as well, while operating at the highest levels of integrity, transparency and inclusiveness.

At the end of the day, “It Takes Two Hands to Clap” and I would go to the extent of saying that it takes to clap louder, and with impact, when there’s enthusiasm and excitement behind it. Let’s work together to breed that positive energy and vibes between the banks and the business community. This has become all the more important and critical in these unprecedented times that our country is passing through. n

My ultimate message is that, as a society, we need to be more mature and realistic in our stance towards businesses and businessmen. We need to respect them and their efforts in contributing towards the economy.

‘Buying local’ no doubt has a strong emotional appeal. Supporting one’s community can have many positive spinoffs, including the development of local talent and the local economy. When it comes to investing in financial markets, we also often have greater comfort deploying our investments in assets with which we have greater familiarity.

As is often the case with investing, though, the intuitive response may not always be the best one. Is a strong home bias hurting your investment portfolio?

Home bias, or the preference of investors to allocate heavily to their home financial markets rather than diversify globally, is a phenomenon demonstrated by investors across most markets.

A study by the Atlanta Fed measured the extent of home bias by looking at actual investor allocation to domestic equities relative to that market’s weight in global markets from a market capitalisation perspective. For example, US equities constituted about 50% of global market capitalisation at the time of the study, but data showed US investors allocated about 90% of their equity investments to US markets. This gap was even wider for other major markets. The bias for investors to invest primarily in domestic financial assets is clearly significant.

Various studies have attempted to understand why inves-

The writer is Chief Investment Officer for Africa, Middle East and Europe at Standard Chartered Bank’s Wealth Management unit

tors demonstrate this preference. One possibility is the cost of investing globally. This can be prohibitively high in some markets, though for many major markets it is often not high enough to outweigh the benefits in terms of investment returns and volatility reduction.

A second possibility is information asymmetry. Investing locally comes with the appeal of adding exposure to ‘what I know’. While having a sufficient understanding of one’s investments is a fair ask, the same Fed study noted that the implicit ‘information’ cost of missing the benefits of diversifying globally appeared to be very high.

Third is an avoidance of taking on excessive currency risk. While this may be less of a challenge in equity markets, where FX volatility tends to be a smaller portion of returns over time, this can pose a bigger share of returns in asset classes such as bonds.

An excessive home bias can hurt one’s financial health due to unintended concentration and from missing the benefits of diversification.

For example, someone working in the energy industry who limits his/her investments to a domestic equity market which happen to have a large weight in the energy sector would be doubling up on the concentration risk in one industry. Even a normal cyclical downturn in the industry would pose a risk to such a non-diversified investor as his/her personal earnings and investment portfolio declines at exactly the same time.

We can see this impact in terms of currency exposure as well. As the table below illustrates, over the past two years, many major currencies, including those of Emerging Markets, weakened in the face of the unusually strong US Dollar. While this could partially reverse should the USD weaken in 2023, as we expect, even a small allocation beyond local market assets would have helped smoothen one’s investment performance.

Research shows that having an excessive home bias (ie. investing primarily in one’s home market alone) leads to sub-optimal outcome for investment portfolios. One can find many examples over the past few years of how investors would have benefitted from a globally diversified portfolio, whether from an industry or currency exposure perspective. The optimal balance between home and foreign assets is likely to vary in each individual situation. However, we believe investors should make a conscious decision to diversify globally as the benefits of international diversification far outweigh the risks.

Amidst economic turmoil and factory shutdowns, the two and three wheeler industry has casually carried on whilst its four wheeler counterpart continues to flounder

By Daniyal AhmadIn Pakistan, the tale of two related industries unfolds like a family drama. The elder brother, the beleaguered four-wheeler vehicle industry, receives attention and investment but struggles to keep his head above water in a tempestuous sea of financial troubles. In contrast, the younger brother, the flourishing two and

three-wheeler vehicle industry, thrives in the shadows. The brothers’ contrasting fortunes reflect the starkly different paths of the industries they represent.

Despite grappling with formidable economic challenges and a parched desert of letters of credit, the two and three-wheeler industry perseveres. It has been shattering sales and export records for years on end,

while the four-wheeler industry only made national headlines with its inaugural export in 2022. Unlike its elder sibling, which has suffered innumerable plant shutdowns amidst the current economic maelstrom, it continues to prosper.

The two and three-wheelers are the sole beacon of hope in Pakistan’s automotive industry. They exemplify Pakistan’s unwavering aspiration for localisation. This is the story of how the unheralded brother harnessed the power of localisation to become the lone bright spot in Pakistan’s automotive history while the other persists in blaming macroeconomic shortcomings.

“In normal circumstances, when left to natural forces, this industry is guaranteed to grow. It could even become a net exporter for Pakistan,” says Almas Hyder, Chairman of the Engineering Development Board. Why is that? “Volumes have risen to such a level and localisation has reached a point where the chances of this industry getting into difficulties are very remote,” Hyder continued.

So what are the localisation numbers that we’re looking at then?

“Atlas Honda leads the auto industry in localisation,” says Afaq Ahmed, Vice President of Marketing at Honda Atlas. “Our best-selling 70cc category has a 94.5% localisation level, while the 125cc category is at 92.4%. However, modern and higher cc series models have lower levels, ranging from 70 to 85% due to lower volumes,” Ahmed continues. Other players in the market are not too far behind either.

“All local 70cc bikes are roughly 85 to 90 percent localised. While we have stopped making 125cc motorcycles altogether, when we did, the numbers stood at 65-70% in terms of localisation,” says Fahad Iqbal, Director at Ravi Automobile. The three-wheeler industry is similar to this as well.

“Localisation in the three-wheeler

industry is an old story; everything is local now. Three-wheeler rickshaws, or taxi rickshaws as they’re known, have been completely localised. All we import in terms of parts is the engine, but the rest is made here,” says Ammar Hameed, Director at Sazgar. The significance of these numbers can only be appreciated when we compare them to their four-wheeled counterparts. According to the Auto Industry Development and Export Policy (AIDEP 2021-26), the Big 3 - Suzuki, Toyota, and Honda - have achieved over 50% deletion across most of their portfolio. However, some of the models on display are either out-of-date or have been discontinued. Newer models reset the clock in terms of localisation alone. Additionally, new entrants from the past five years are completely absent.

The peak for four-wheelers in terms of localisation figures is simply the norm in the two and three-wheeler industry.

There’s a simple answer to this: volumes, and a bit of imitation.

Data from the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association’s (PAMA) statistics from FY 2007/8 to FY 2021/22 show that they not only dwarf every other category of vehicle, but they also sell in excess of all other vehicles combined. Multiple times over. Three-wheelers in contrast are not as imperious.

However, the majority of the manufacturers from the three-wheeler market are also not members of PAMA. Furthermore, three-wheelers operate in a unique position whereby it’s a race to the bottom in terms of price due to the nature of the customers they cater to. Profit has documented this particular aspect in an earlier piece.

Read more:Electric rickshaws: Between Yellow-brick and Lytton road

Now, the imitation part. This is fairly simple. It’s a monkey see, monkey do kind of phenomenon at the base level.

“The motorcycle market is basically divided between Atlas Honda and Atlas Honda clones. We’re looking at a massive market that has identical components, irrespective of the brand that’s making it,” says Iqbal. “I think all the initial work for localisation was, frankly speaking, done by Atlas Honda. When the Honda clones came in, it accelerated that growth in terms of localisation because all of a sudden there was much more volume available of the same components, which of course encouraged the vending industry or the

Volumes have risen to such a level and localisation has reached a point where the chances of this industry getting into difficulties are very remote

Almas Hyder, Chairman of the Engineering Development Board

component manufacturing industry as well,” Iqbal continues.

It’s a similar story in the three-wheeler market too. “There are two prevalent designs across three-wheelers; ours and New Asia’s. All other players copy one of the two when they manufacture their product,” says Hameed.

“If the market for two and three-wheelers had featured a variety of shapes and designs, the level of localisation would not have been as high. Following the same designs has worked in the country’s favour by making the product affordable for consumers,” says Iqbal. “While some argue that customers want something different, everything comes at a price. If we had pursued different designs, the products would be more expensive, with lower volume and less affordability,” Iqbal adds.

How exactly does having similar shapes and designs assist with parts and subsequently localisation? “Vendors just need to make slight changes to their parts, and then they can sell the part to any manufacturer wanting to use it. The slight alterations also allow them to circumvent violating their contracts with any one manufacturer,” says Hameed.

“Localisation is usually the result of any one manufacturer in the industry acquiring and training the vendors, and then slowly more

players enter the space,” Hameed continues. “Two and three-wheelers are also less complex than four-wheelers. A car has thousands of parts. Two and three-wheelers do not. They have fewer parts which makes them easier to localise and subsequently copy,” Hameed adds.

“It’s a similar case for any successful model in Pakistan. If you were to have a successful flower stall at Liberty Market in Lahore, then one day you’d notice that suddenly other flower sellers will pop up doing the exact same thing. People hop on the bandwagon for whatever is successful,” Hameed muses.

So is it just the fact that cars have more parts that makes them more difficult to localise? Though cars are not as similar to one another as two and three-wheelers, they’re also not that different from one another. Right?

“The four-wheeler industry does not generate enough volume.

The Swift costs Rs 4,000,000; how many people do you know that will pay that much for the Swift? If there’s not enough volume, then localisation cannot occur,” says Hyder. “The four-wheeler industry

still hasn’t crossed the 250,000-270,000 mark in terms of annual sales,” adds Iqbal.

“Even if the car market does cross the 250,000 or 300,000 mark, the sales will be divided over two dozen variants. This wasn’t the case a decade ago when you had just three assemblers providing a handful of variants. The volumes will just never make sense to localise,” Iqbal muses.

This then raises two questions: were the two-wheeler and three-wheeler industries always destined for success? And why do they not get enough credit for what they’ve achieved?

Let’s start with the first question.

The simple answer to this is no. “Imagine a Pakistan that had a very strong public transport system or very high income levels. These markets would not be what they are then,” says Iqbal.

Short and simple.

Now onto why these two industries do not get the attention they deserve?

The simple answer to this is that the two and three-wheeler industry simply do not evoke the same level of excitement or curiosity as their fourwheeled counterparts. The CD-70 is iconic in Pakistan, but social media is not filled with pages dedicated to it in the same way as those dedicated to luxury imported cars. Similarly, three-wheelers are perhaps the backbone of Pakistan’s transport infrastructure, but cars dominate every press conference relating to road construction and expansion.

Two and three-wheelers are utilitarian vehicles at the end of the day whereas cars are, for the better part, a luxury in Pakistan. The stats speak for themselves. The Pakistan Social And Living Standards Measurement (2018-19) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics identifies 54% of all Pakistani households to have motorcycles,

New models face challenges when entering the market. They require new parts that aren’t available in Pakistan, forcing companies to invest large sums of money. Additionally, localisation must begin from the onset of the new product, further increasing costs. This makes it infeasible for customers accustomed to low prices to purchase themAfaq Ahmed, Vice President of Marketing at Honda Atlas

whilst only 6% of households have cars. A utilitarian product will simply never turn heads the same way a luxury product will.

Honda knows that their newest Civic will always grab more attention than their CD-70, and Sazgar knows this to be true in terms of their H6 relative to its three-wheelers. However, that’s not to say the two and three wheeler industries haven’t tried to change this. It’s just that they simply cannot. What do we mean here?

“New models face challenges when entering the market,” Ahmed tells Profit. “They require new parts that aren’t available in Pakistan, forcing companies to invest large sums of money. Additionally, localisation must begin from the onset of the new product, further increasing costs. This makes it infeasible for customers accustomed to low prices to purchase them,” Ahmed explains.

“When manufacturers want their vendors to make new parts for them, they have two options,” Hameed explains. “They

can either bear the tooling cost themselves and upgrade the vendor, or they can amortise the vendor’s cost by allowing them to charge a higher price for a certain number of units to recoup their expenses,”.

“This decision forces companies to undertake demand and cost forecasting,” Hameed continues. This is, however, an exercise that simply makes no sense given the current state of the two, and three wheeler industry.

“Why would a company want to invest in a new model if their current product is selling well, efficiently designed, and supported by a network of dealers and mechanics all over the country?” asks Iqbal. “If at least 95% of customers are happy with the product, why spend millions of dollars on something new?,” Iqbal adds.

Is there anything the government could do to maybe make these industries more glamorous so they can receive the attention they deserve? Well, yes. There is one way the government can reduce the costs of compa-

nies wanting to undertake modernising their models. Repeal Statutory Regulatory Orders (SRO) 693, 655, and 656. What are these one might ask?

These SROs cumulatively comprise the policy framework for levying duties upon automotive parts imported into Pakistan. They are also what make the new models of vehicles everyone wants more expensive according to Ahmed.

The answer then would be to just repeal them right? We’d all get the Hero Honda motorcycles that our neighbours across the border enjoy. It’d also make Sazgar’s fancy new electric rickshaws more affordable for everyone. However, the decision is not that simple.

“Eliminating the SROs would mean that we no longer want to be a country that manufactures components for these products,” says Iqbal. “Removing the SROs is not good for the country. The local industry thrives because of them. Manufacturers and vendors hire more people and create jobs,” says Hameed. “If we were to do away with the SROs, the base price of products would decrease, benefiting companies, but Pakistan would become a trading country,” Hameed adds.

“The volumes are there. If foreign players want to enter the market or if companies want to innovate, they should focus on localising everything. If you’re willing to localise everything from day one, you’re likely to capture a reasonable portion of the market,” says Iqbal. “These SROs do add a higher cost for manufacturers, but it’s a cost worth bearing for the overall benefit to everyone,” says Hameed.

Imagine being so successful that you suffer from it. That’s the story of these two industries. They’ve honed their skills to perfection, yet they may never receive the recognition they deserve. Why? Because they’re content with the way things are. But will this always be the case? It’s unlikely. These industries march to the beat of their own drum and will change at their own pace and on their own terms, unlike their four-wheeled counterparts. n

If the market for two and three-wheelers had featured a variety of shapes and designs, the level of localisation would not have been as high. Following the same designs has worked in the country’s favour by making the product affordable for consumers

Fahad Iqbal, Director at Ravi Automobile

If we were to do away with the SROs, the base price of products would decrease, benefiting companies, but Pakistan would become a trading country

Ammar Hameed, Director at Sazgar

By: Momina Ashraf

By: Momina Ashraf

New York, Paris, Milan . . . Lahore? Pakistan’s lawn craze creates a new style capital in the world. Although not a fashion week, the lawn collections, perfectly aligned with Eid, is a semi-annual fashion festivity, much like the well-attended fashion shows. It’s the perfect time for newcomers to map their presence, established ones to set the benchmark higher and forgotten ones to get back into the game.

Every year the three-piece suit takes on a new style. From choori daars to shararas, cotton dupattas to organza silks, self-print to embroidery, the lawn collection is as unique and as embellished as any high-end designer wear. Every year, as the pack of lawn suits gets heavier with necessary embellishments and motifs, the tag also gets pricier.

But here’s the catch, people still want to buy it.

“Please find out the science behind how the dresses get sold out within a few minutes of launch,” snarked Lubna Qayoom, an average lawn customer, on an all-women Facebook group where Profit reached out to the target audience.

Pakistan’s fashion industry is one of the rare industries that is doing well in the prevalent economic climate. Back in parents’ generation, the fashion industry catered to just a few - the high-end socialities and celebrities. It was unheard of having a branded suit for Eid, let alone designer wear for a regular get-together.

However, with time social dynamics changed and the country saw a rise in the urban class, working women, and an increased disposable income. This led to the expansion of the fashion industry’s consumer base. Slowly, brands like Khaadi, Alkaram and J. came to the forefront.

Apart from this, by 2017, a dip in textile exports forced the big names to bring the middle class within its fold; this has led to increased competition and production in the lawn season, the products of which are much in demand almost throughout the year. In fact, several textile manufacturers such as Sapphire and Nishat textiles launched retail brands with seasonal lawn lines.

In April 2021, the export value of the textile and clothing industry stood at $1.3 billion, reflecting an increase of 231% from $403.8 million in the corresponding period of the previous year. The growth has been attributed to the Economic Coordination Committee’s approval for import duty-free cotton yarn until the end of June 2021.

From buying yearly Eid clothes from these brands to buying even casual wear for home became the norm. The mainstreaming of brands led to another phenomenon, designer wear. Designer clothes, such as Élan, HSY, Maria B. which were limited to ramp walk models became available to women of upper-middle and upper-class families. The designer lawn, in essence, truly made the dream of magazine glamour a reality.

“Even when we design, the main thing we keep in mind is that it is not for ordinary citizens. Women buy designer lawns just so they can show they are wearing designer lawns,” said a designer from Zara Shahjahan, who wishes to stay anonymous. “Designer lawn is the local version of rich people wearing Dior and LV abroad. It’s about showing, without having to say that you have taste and class,” she continued.

Profit learned that designer lawn, as the name suggests, is a careful curation of embellishments, thread work and colours and its preparation takes up to a year.

“The lawn category has designated 12 designers. Zara encourages all junior and senior designers to create and design. Every year a new designer gets a chance to make it to the final collection. The team sits and plans and works and reworks,” explained the designer. “The lawn designs are created with the intention of introducing something new in the market. For example, we were the first ones to introduce matching basics and now everyone is doing it. Zara Shahjahan sets trends so we have to be ahead of the game. Some pieces follow the already set standard, but there always has to be something completely new as well,” she added.

The lawn season is the busiest for designers, more than the bridal season. By the time of the launch, all departments come together to sell the product because of how much traffic there is. “And it sells, within days and some-

times even on the first day,” explained a source . So who is Zara Shahjahan’s biggest competition? “Élan!” blurted the source. “We do not only have to look after our own launch but keep track of Élan’s also. Only they are our direct competitors in lawn,” she pointed out. Élan, a luxury designer brand launched in 2004 is the brainchild of Khadijah Shah. Although kickstarted off with luxury couture, in 2012 the brand spread its wings and ventured into the lawn market. It was to cater to a wider audience, while still maintaining a bit of a niche. “Our target audience is the upper class so inflation did not impact them. We saw a slight dip in other collections but for lawn, the demand is the same as before,” said a designer from Élan, who wishes to stay anonymous.

Most designers do not have their own mills and outsource raw materials from other mills. In the planning process, a sample of fabric is ordered from the mill and dyed inhouse. “They give us samples and we give them business,” that’s the usual practice, informed the anonymous source from Élan. “We order samples and dye and print them. If approved we make the business deal with the 1,5002,000 orders and the sample price is adjusted within it,” she explained.

It is pertinent to mention here that Élan was bought by Sefam group in November last year. While under Khadija Shah, Élan partnered with Sapphire Textile as a backward integration for a steady and high quality supply of the in-demand lawn fabric, while Sapphire used Shah’s creative impetus to further their retail aspirations. It worked for both parties involved, until it didn’t.

Profit did a feature piece on the Élan-Sefam deal with details of the Sapphire-Khadijah Shah arrangement as well based on an interview with Shah. Read here.

Once the collection is made, its launch is nothing short of a release of a bigscreen film. “The hype starts fifteen days prior on social media and our websites,” said Minahil Khan, Growth Associate for LAAM, a one-stop online store for fashion brands. There

are photos, sneak peeks, trailers and reels shot from picturesque locations. On the website, there’s a countdown running on the last day, and some even have the option of pre-order.

“It’s crazy on the day of the launch,” mentioned Khan. If it’s a hit collection it will get sold out within days earning an average revenue of 30 million. And if it’s not, the articles will remain unsold even by the end of the season.

“We have to carefully market them, and let people think that something major is coming,” mentioned the source from Élan. That’s why the marketing costs are the heaviest in the entire process. “We decide the model and location during the ideation phase of the collection. The pieces are made specifically for certain faces and celebrities which we know will bring life to it,” said the source from Zara Shahjahan.

Upon asking, Zara Shahjahan did not quote their marketing budgets but according to Khan from LAAM, the campaign budget for lawn alone costs a minimum of Rs 100 to 200 million. “If the campaign takes a major celebrity face Rs 20-50 million is allocated for that only. Although the costs can vary a lot, for example, if the shoot is international then it’s a different ball game. But the minimum slab is somewhere around Rs 20-50 million easily,” she explained.

The cost of raw materials and production goes up to about 150 to 200 million for a single lawn collection. But then there are other costs too which include utility, staff and a lot of other administrative costs. Designer lawn pieces, according to the source from Élan, earn a margin of almost 50%. It essentially includes the labour employed at every stage from ideation to distribution. A limited quantity, around 300-400 of such pieces are made, and the price tag, which now exceeds almost Rs 20,000, is there to maintain exclusivity.

“It’s not,” simply replied Amir Rasheed, business manager for Mahgul Designer Studio. Lawn is not only becoming expensive for the customer

“One can’t export it if the cost is higher than other countries and the cost of doing business is higher in Pakistan at the moment. Yarn, the raw material for lawn, is imported, so the final pricing depends on import duties as well”

Shahid Sattar, advisor at All Pakistan Textile and Mill Association (APTMA)

but even for the designer. “There’s a lot of units involved in making a single design of lawn. Textile mills, dyeing mills, printing units, embroidery houses, stitching, packing and a lot more. The costs at each stage are increasing. In the end, it’s a piece of lawn for daily wear, not luxury wear,” he explained. “We don’t think that designer lawn is the thing of the future. It’s too much money and hassle for the customer and for us. Lawn fundamentally is a light piece of clothing for summer, not a suit which is just one step below a wedding dress. Lawn’s disposability and rapidly changing trends don’t make the cost and price not worth it,” he continued.

“Even the 30-50% margin designer lawn earns is not realised into profit. From these margins, almost one-third goes to GST and a heavy proportion for marketing and selling. At the end about 10-15% is left from a 30% margin only”, said Rasheed.

The lawn market is immensely competitive. Every brand has a special focus on lawn and since they know they want to make it accessible there is only so much profit they can make out of it. “Even these profit margins for designer lawns are limited,” said Khan. “The profit margins for luxury and bridal collections are way higher. In every process, you have to cut above the rest.”

The real craze for lawns comes not from exclusivity but from accessibility. The big giants in the market, such as Sapphire, and Alkaram have their own textile mills, which takes production and revenue to a whole new level.

They are a tier below the designer lawn which focuses on a much wider consumer base. Brands such as Sapphire enjoy mass popularity and their way of doing business is also different. In conversation with Bilal Ashraf, lead designer at Sapphire, we learned that for retail brands the profit margin is usually 30-40%. That’s because the brand has its own textile mill and from embroidery to dyeing to weaving, everything is sourced and completed in-house.

Mill-owning brands produced at least 1,000 units of each lawn article. If a certain article gains popularity, its production doubles and is sometimes continued in the next collec-

tion as well. “There’s a lot of profit margin in lawn. For such brands, lawn is the business’s cash cow,” said Khan.

“Our main aim is to cater to the needs of the customer. We know what they want and we cash in on that. While designing, there’s a set category too. There’s a triangle we often refer to in the process (see below). The widest range, the base, is made up of the ‘essentials’ which are everyday wear for college students and working women starting from Rs 990. Then there is ‘commercial’ which is a bit fancier, with slight embroidery and on average cost around Rs 4,400. Essential and commercial both follow the already set designs and styles. Then the tip of the triangle is for ‘directional’, where there is room for experimentation and setting new rules. Such collections usually come around the first volume,”

The furore with lawn business has shaped the industry in a manner which produces a complete package for international sale. If India is known for its banarsi saree, Pakistan is known for its lawn shalwar kameez.

In a story previously done by Profit, it was reported that over the past two decades Pakistani lawn has become a $54 million market in India. There is often a shortage of Pakistan-made lawn suits due to high demand and a shaky supply chain. But due to unreliable bilateral trade relations with India, the middlemen in the business become the real winners. “From our experience, most of the brands don’t prefer selling directly, especially internationally. We have sent multiple emails to their sales team but they don’t seem to respond,” says Akram Tariq Khan, co-founder of Your Libas, an Indian online marketplace for Pakistani suits and kurtis in India and the rest of the world. “At the end of the day, there is always a middle-man ready to facilitate the deal – an approach that is unprofessional and unorganised.”

The situation in other countries is much

better though. Around 10% of Élan’s lawn collection is sold internationally, specifically in Dubai, the UK and the USA where there is a massive desi community. “With currency depreciation, the sales might have actually increased a bit because for them it’s a lot cheaper now. Inflation didn’t impact them,” mentions the anonymous source.

This is something which many brands can profit from, but the textile industry itself is not in the right place. Back in 2019, Shahid Sattar, an advisor at All Pakistan Textile and Mill Association (APTMA) told The News, “One can’t export it if the cost is higher than other countries and the cost of doing business is higher in Pakistan at the moment. Yarn, the raw material for lawn, is imported, so the final pricing depends on import duties as well.”

Since then, things have massively changed. In the current situation, exports have declined by 12% due to a shortage of raw materials. Due to the floods, the cotton crop experienced immense damage and against the requirement of 14 million bales, the country could only produce 5 million bales of cotton domestically. Owing to low foreign exchange reserves and curbs on imports, cotton could not be imported as freely and readily as required. “We have had to keep the profit margins low this time, somewhere around 15% because the industry is not in good shape. This year the retailers are bearing the brunt of the higher costs of doing business, let’s see how things progress further,” mentioned Ashraf from Sapphire.

Profit reached out to APTMA for a comment, but did not receive any.

So coming back to the fundamental question? Is a lawn suit worth the price? Just like any other fashion piece, its ‘worth’ so to speak is determined by consumer perception and demand. Lawn, although highly disposable, is taking new shapes and designs to maintain luxury and innovation.

And it works well. In a country, where there aren’t many avenues for leisure for women, shopping is a safe and suitable option where the affordability and variety of lawn fits the equation very well. n

“We don’t think that designer lawn is the thing of the future. It’s too much money and hassle for the customer and for us. Lawn fundamentally is a light piece of clothing for summer, not a suit which is just one step below a wedding dress. Lawn’s disposability and rapidly changing trends don’t make the cost and price worth it”

Amir Rasheed, Business Manager, Mahgul Designer Studio

“The hype starts fifteen days prior on social media and our websites. Launch day is crazy!”

Minahil Khan, Growth Associate, LAAM