21 minute read

The fault in our cropsGrowing too much of one, none of another

How chai and sutta went from guilty pleasures to pricey indulgence

By Abdullah Niazi

Advertisement

Asingle cup of chai costs Rs 50 now. If a person consumes three cups a day, every day, the number multiplies to Rs4,500 a month. In a country where the minimum wage is Rs15,000, tea drinking can consume a whopping 30pc of income.

Once considered a small pleasure of life, the quintessential ‘chai ka cup’ made with tea leaves, sugar, and milk is quickly becoming a luxury. And it isn’t the only guilty pleasure that is fast evading the pockets of most people. Back in February this year, the tobacco industry was jolted when a huge increase in duties on cigarettes resulted in the product becoming more expensive by as much as 250% overnight.

While the more expensive imported cigarettes have gone far out of reach, even the cheaper local brands are selling at around Rs 11-12 per cigarette. That means for a person smoking five cigarettes a day, the bill comes out to around Rs 55 a day. This adds up to Rs 1650 a month, giving a ‘chai-sutta’ bill of just over Rs 6000 a month — which is nearly half the minimum wage in Pakistan.

So how are the manufacturers of these everyday pleasures that have turned into luxuries responding? On the one hand there is tea. Not grown in Pakistan, almost entirely imported, and with a uniquely inelastic demand the product will see no respite in prices since it has to be brought in from abroad. Meanwhile cigarettes are an entirely different game. Pakistan produces most of its own tobacco and at very high yields, yet the prices of cigarettes going up have to do entirely with levies and sin taxes. Profit explores.

Tea

Right before Ramazan the price of black tea (loose) had swelled to Rs1,600 per kg from Rs1,100 thanks to curbs being put on imports in the country. So why did prices of tea skyrocket by more than Rs 500 per Kg and are expected to continue to be affected by inflation after Ramzan?

Pakistan, unfortunately, barely grows any of its own tea and is in fact the world’s largest importer of tea spending $596 million on it last year. Meanwhile, India produces 0.94m tons of tea a year, consuming 70% of it domestically. Our story begins in 1813, when England’s parliament restricted the powers of the East India Company. The company had a monopoly on growing tea in China and had discouraged its production in India. This changed once the English government took a more direct interest in India.

In 1834 India’s first governor general, Lord Bentinck, formed a committee to submit “a plan for the accomplishment of the introduction of tea culture and growth into India.” The British hoped they could increase their production of tea by growing it in India as well as China.

Assam was the first area to be devel- oped, followed by the Himalayan foothills in 1842, the Surma valley in 1856, and Darjeeling in 1858. This rapid rise was testament to the ingenuity of the British colonisers, who settled major wastelands for the cultivation of tea-gardens.

This ingenuity, however, came at a grave cost to local communities. The project was undertaken with the express purpose of encouraging foreign enterprise. Barriers to entry such as not giving a grant of less than 100 acres kept local communities from benefitting.

By 1949 India was producing a total crop of 600 million pounds annually, nearly half of which was being exported to England. Now, up until 1971 a lot of the domestic tea consumption in Pakistan was met by tea farmers in East Pakistan. However, with the independence of Bangladesh Pakistan was suddenly a country that grew tea nowhere, but had a population that was hooked on the hot drink. So what did they do?

Pakistan simply started importing tea from India and Sri Lanka. The substance was cheap and not a major strain on the import bill. The first attempt to grow tea was made in 1982, when Chinese experts reported the hilly terrain of Mansehra would be ideal for tea-gardens.

Since then, however, progress has been slow and in the past decade down-right regressive. Tea was first planted in Mansehra in 1986, and then in 2001 in Swat both by the government and private companies. At its peak, Pakistan was growing tea on nearly 900ha.

However, currently this is limited to an area of 100 ha under Unilever Brother Support in Mansehra. The issues have been typical. In the initial days, the government was providing support like free nursery plants to encourage growth. As soon as the schemes ended, interest died out too.

Tea is a difficult crop to grow. In their natural state, tea trees have been known to grow to heights of 70 feet. When planted in fields, they rarely reach over four feet, making tea-gardens a vast forest of miniature trees. And these trees have a 5-year maturation period.

This makes them an unattractive prospect for farmers. Tea farming proved to be unprofitable because the price of plucked leaves (raw material for black tea) at Rs 46/ kg is much higher in Pakistan than that in the international market i.e. between Rs 20-22 per kg.

Pakistan could have become competitive with the international prices by growing more. Research has shown there are 64000ha of land in the country ripe for tea production. This with value addition and cost reducing measures across the value chain would have made a big difference.

Now, as a macroeconomic crisis brews in the country and Pakistan is cash-strapped for dollars, there is an acute realisation that these are very much products that we should be growing ourselves.

Cigarettes

In 1947 no tobacco was grown in Pakistan. Today, Pakistan has one of the highest per-area tobacco yields in the world and is a major producer. For decades, despite this initial lag, cigarette manufacturers thrived while growers have gotten the short end of the stick. But this year the script has been flipped.

The tobacco sector has been at the hit list for the government’s increasingly higher revenue collection needs, by paying higher taxes. A fresh massive strike of around 153 percent Federal Excise Duty (FED) rates on cigarettes in February caused around a 250 percent increase in the prices of cigarettes, produced by legitimate companies.

As a result, the country’s largest cigarette manufacturer claimed that smuggling of cigarettes has increased by 39% in just two months since the government raised an estimated 154% in Federal Excise Duty (FED) on cigarettes. The effects of this hike trickled down to taxes, causing a major hike in cigarette taxes, jolting Pakistan’s legitimate tobacco industry. As a consequence of cigarette prices hitting the roof, the tobacco market has been flooded with over 70 new brands of cigarettes during this short span of just two months.

Of course, this claim is not as simple as that. You see, there is a very strange stand-off between large cigarette producers like British American Tobacco and local producers in Pakistan. On the one side are the big-boys of nicotine, the two multinational cigarette manufacturers that control nearly 90% of the country’s tobacco consumption market share. And on the other are more than 50 smaller companies. All local, all willing to scrap, and all a constant thorn in the back of the multinationals.

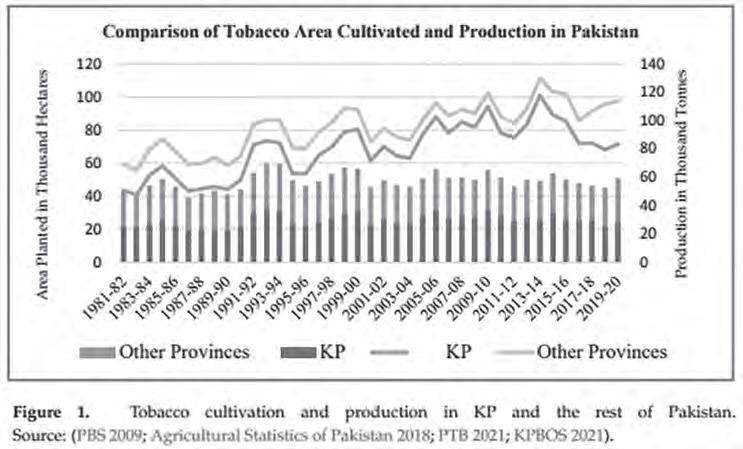

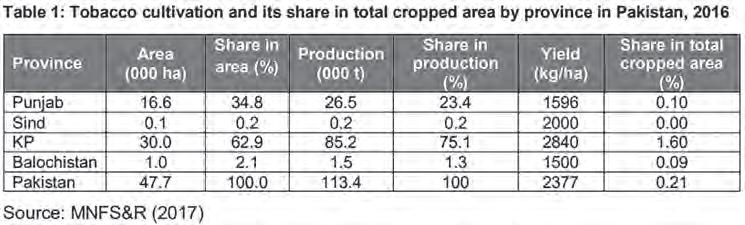

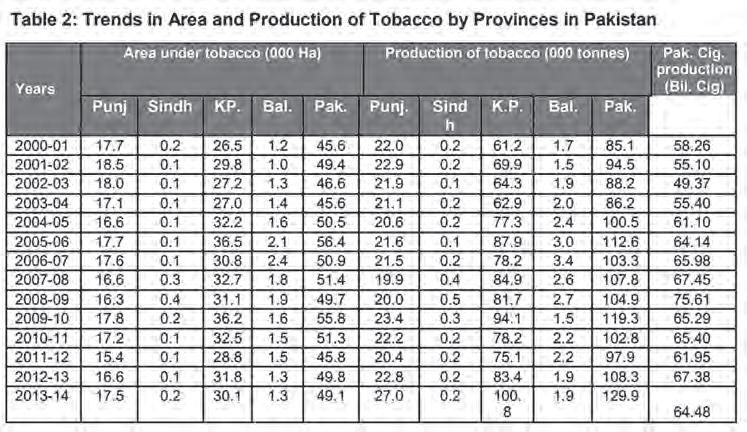

At the centre of this battle between evil and evil are vast swathes of fields in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa where tobacco is grown. Tobacco is grown in all four provinces in Pakistan, but it is predominantly grown in KP where it is a major part of the local agrarian economy. KP’s provincial economy is pegged majorly to the growth of tobacco. More than 80% of KP’s population lives in rural areas, with agriculture accounting for around 30% of provincial GDP. Pakistan currently grows tobacco on some 50,800 hectares, with KP making up nearly 30,000 of these hectares.

It is one of those rare agricultural products where Pakistan is ahead of the curve. Over the more than 50,000 hectares on which tobacco is grown, Pakistan’s yield per hectare stands at nearly 2.3 tonnes per hectare with a total production of 113.6 million kilograms. In comparison, the world average production for tobacco is 1.84 tonnes per hectare. Meanwhile, KP in 2021 produced 71.38 million kilograms on 28,089 hectares of land, giving an average yield of 2.5 tonnes per hectare — a 66% rise on the global average.

The first efforts to grow tobacco in Pakistan came with an experimental 20 acre farm in 1948. Here it was discovered that KP was an ideal area for the cultivation of tobacco.

Farming began quickly, but the crops were low-quality and only used by local cigarette manufacturers.

The biggest tobacco company at the time, British American Tobacco, still had to import tobacco to manufacture cigarettes. Things really took a turn in 1968 with the establishment of the Pakistan Tobacco Board entrusted with promoting and developing tobacco production and export.

In 1969, Philip Morris International established itself in Pakistan, bringing with it both research and development for the tobacco crop and increased competition. As a result, tobacco started being grown on more land, but even more importantly, the per-area yield rose.

Yield in KP increased from 43,408 tonnes in 1980 to 71,410 tonnes in 2020, while the area under cultivation only rose by 4,000 hectares in that time. This means that while the area under cultivation grew by around 16%, the total production rose by a comparative 65%.

Clearly this means Pakistan has great potential as a tobacco exporter. Tobacco exports stood at $55.94 million during 2021. Even though our per-area yield is high, to increase the export numbers we need to grow tobacco on more land to have enough volume to be a major exporter.

For that to happen farmers need to be making money. Tobacco farming has historically been profitable, but the end benefit does not always go to the farmers. Cigarette manufacturers buy green leaves at cheap rates from the farmers and then process them into smokeable tobacco.

On top of the low rates for these green leaves, tobacco farming requires a lot of expensive inputs such as fertilisers, labour, mechanical power, pesticides etc which discourages existing farms from expanding and new farms from being set up.

This is where things get more interest- ing. There is definitely a case to be made for more areas being used for tobacco cultivation. However, the problem will not be fixed until the farming of tobacco leaves becomes profitable. One of the biggest impediments to this is how the tobacco industry in Pakistan works.

There are two MNCs that operate in Pakistan. One is the Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited (PAKL), which is the Pakistani subsidiary of British American Tobacco. The other company is Philip Morris Pakistan Ltd (PMPK). Together, these two internationals control 90 percent of the market. They also pay 98 percent of the tax that is collected from this industry. That is where a major contention exists between the MNCs and the local players.

The other 52 tobacco companies in Pakistan only pay Rs 2 billion in taxes every year. To put this in context, this is only 2% of the total tax collected from the tobacco industry. This means that there is stringent competition between the two sides. So much so that the MNCs actually lobby for higher taxes that are more stringently imposed on the local growers and manufacturers. They believe that because they pay so much more tax while local producers do not, they have an unfair advantage. And at a time when these big companies are being taxed more than ever, the smuggling market and local markets will thrive at their expense.

What is the future for chai and sutta?

Both of these are products that are here to stay. The unfortunate part is that we grow the product that is dangerous to human health while we do not grow the product that is not dangerous — even though we have the capability and resources to do so.

Ideally, we should be headed in a direction where tea is grown in Pakistan and cigarettes continue to be highly taxed as most forward-thinking tax regimes around the globe have done. In an op-ed for Dawn, former SAPM on Health Dr Zaffar Mirza claimed that the time was ripe for a heavy tax to be slapped on consumer items that have proved to be harmful such as tobacco products and sugary drinks.

“Such a measure would be good for public health and will support the ailing economy. Smoking is on the rise, and a cash-strapped Pakistan desperately needs revenue. The IMF supports such taxes and tobacco excises in Pakistan are way below the recommended global level. Tobacco is lethal. Of the eight million deaths that occur globally each year due to tobacco use, 170,000 are in Pakistan — to put it into perspective, the total deaths from Covid-19 in Pakistan were around 31,000,” he wrote. n

By: Yousaf Nizami & Shahab Omer

In terms of planning and infrastructure, barring Islamabad, Lahore is arguably the best developed urban centre in the country. Place the two cities in their context and it becomes clearer why this second-place is impressive. Islamabad had the benefit of being built on a blank canvas with the requirements of a capital city in mind. Lahore, on the other hand, is an ancient city that along with its heritage also brings its own baggage.

Yet over the past decade in particular, Lahore has undergone a major renovation that has made many parts of it quite unrecognisable. Central areas such as Gulberg have been transformed into ‘signal free corridors’ using u-turns, overhead bridges and underpasses. DHA has expanded considerably, finishing at least three new phases with residential and commercial properties that are well-populated and announcing several new ones, while Johar Town has become a city within the city. Most recently, Main Boulevard all the way to Cavalry and the DHA entrance have undergone massive renovations for the introduction of Lahore’s Central Business District where once the old Walton airport and Walton forest existed. With these improvements in road network, infrastructure and the urban sprawl that has accompanied it, population density has shot up as well. Going by the latest census (2017) Lahore has 6,284 people per sq. km. To add some perspective, Karachi has 3,944 people per sq. km.

It was inevitable therefore that someone got the idea to go vertical and around six years ago apartment building projects started springing up all around town. The idea behind the expected success of so many apartment buildings was the benefits it provided over conventional home ownership and how, like Karachi, perhaps Lahore was finally ready for apartment living. Profit did a detailed story on those upcoming projects back in 2017 detailing the economics and profitability of these projects.

In this article we won’t be taking a ‘6 years later’ look at those projects, rather present a thesis that in the current economic climate of high inflation and low GDP growth, apartments have become significantly expensive, at a rate much higher than that of conventional residential housing.

Shrinking space

As per the 2017 census, Lahore is a city of 11.1 million people and on average has had an annual growth in population of around 4.07% since 1998. Going by that average, Lahore will have close to 14.1 million inhabitants by the end of this year. This is of course a loose estimation at this point and can only be confirmed by the ongoing 2023 census.

According to a study published by the Urban Unit, a Project Management Unit (PMU) of the Planning and Development Department under Government of the Punjab, which is a detailed analysis of data on Lahore district, as published in the 2017 census, the annual increase in population is closer to 3.0%. While lower than other estimates, it is still higher than the national average of 2.7% for all urban areas.

While growing population is a concern, rapid urbanization is a much bigger worry, the report emphasizes. From 1995 to 2005 Lahore’s Urban areas grew by 4.3%, from 220 sq. Km to 336 sq. km. By 2015 it had grown to 665 sq. km, a 7.1% jump in the second decade. Estimates are that by 2025 urban Lahore will cover an area of 1,320 sq. km. The study’s land consumption analysis shows a worrying statistic: for every 1% increase in Lahore’s population, an extra 2.82% of land is consumed.

A shift towards incentivising developers to invest in high rise housing projects rather than horizontal expansion to arrest this rapid land consumption, began.

Up up and away

Five years ago, soon after the Lahore Development Authority (LDA) doubled the permissible height limits for residential apartment buildings, almost doubling it from 45 ft. (ground plus three floors) to 80 ft. (ground plus six floors), a plethora of projects were announced.

The sales pitch was also very straightforward: own a place in central Lahore by paying far less than what it would cost to own a house in the same vicinity. And although the projects varied when it came to features, two aspects of each project were almost universal. The location must be Gulberg (it doesn’t get more central than that) and the finishing of the apartments must be high end.

For developers, at least on paper, it made good financial sense as well. The major initial investment was the cost of land following which the selling became crucial as the installments from each apartment sold, spanning over 2-3 years, would be used to build the project. ‘All equity, no debt’.

Through our reporting back in 2017, we arrived at the conclusion that a fully delivered and sold project would generate 115% return on equity. That was then. Things have changed massively since 2017, in fact, even more so in the last two years, as the economy tanked, inflation skyrocketed and the rupee depreciated to record levels.

Highrises amidst higher inflation

The past two years have been brutal on most industries, real estate included. An astronomical rise in cost of production and a general climate of economic uncertainty has severely slowed down investment and economic activity. Additionally, a discount rate of 22% that is likely to increase further has made investors park their cash in 100%-capital-secured government-backed paper.

Therefore, developers with incomplete projects are facing a double whammy. Not only have they overshot their budgets, there is no demand for their apartments at the revised selling prices, which means they can’t generate additional funds as there are no fresh sales being made. Additionally, installments for apartments sold at 2021-2022 rates, on average 52% lower than current prices, are proving insufficient to finance construction.

“High rise luxury apartment projects are generally associated with installments and most of them involve investors’ money. Due to inflation, these projects became expensive and investors stopped paying installments, which resulted in developers halting construction”, explained Javed Iqbal, a property dealer in Lahore DHA area, while speaking to Profit

“For example, Defence Raya launched a project consisting of three high rise buildings two years ago. They had received half the installments, from launch to present day at a rate of Rs 22,000 per sq. ft. Owing to market conditions they were forced to increase this to Rs 28,000 per sq. ft. Construction projects across the country are facing a similar situation,” Iqbal added.

The main culprit in rising construction costs is steel. Between 2017, when most projects began, steel cost Rs100 per kg. By 2021 it had risen to Rs 125 per kg. However, rates in 2023 jumped to unimaginable levels, peaking at 325 per kg. Currently available at 285 per kg, owing only to a drop in demand, steel is still too expensive, costing 128% more than two years ago.

And it’s a somewhat similar story with other essential materials as well. In 2021, cement was going for Rs 700 per sack, which went up to Rs 1,030 per sack in 2022 and at present it is being sold in the market for up to Rs1,150 per sack. Plywood has gone up from Rs 1600 per cubic feet while this year it is Rs 2,400 per cubic feet while Diyar wood costs around Rs 12,00 per cubic feet as compared to Rs 8,000 a year ago.

Hasan Sami, a developer who is constructing a high rise apartment building on Lahore’s Zafar Ali Road, told Profit that the prices of construction materials have increased by more than 100 percent in the last one year.

“When we made the feasibility of our project, the rate of steel was Rs 102 per kg, it is Rs 302 per kg now. Similarly, the price of a cement bag has more than doubled. As a result, our construction cost increased. Since we had an end-user focus when launching this project, as soon as prices of these materials increased we decided not to announce the sale of the project. Now that we have completed a lot of work, we intend to announce its sale in the next two months,” he said.

Enter the CBD (and its critics)

The CBD was launched by the Punjab Government last year to develop commercial real-estate in Punjab. The ethos behind the project was to use unused government land to develop a district within Lahore where commercial and residential real estate projects could be developed. And the style of all these buildings? High-rise. And not just apartment buildings, but business parks and high-rise office buildings too.

The problem for the CBD was, however, that the area in which they were developing this real estate is land-locked. That is why in November 2022, the CBD initiated the extension of the Kalma Chowk underpass. The project constitutes two parts: the construction of the CBD Punjab Boulevard and the remodelling of Kalma Chowk Underpass.

“The underpass serves primarily to facilitate the business district, by providing car access to landlocked property. Such infrastructure only benefits motor transport, that includes both cars and motorcycles”, says Raffay Alam, Pakistan’s leading environmental lawyer.

“The remodelling of Kalma Chowk Underpass has largely been proposed and implemented for the Central Business District. The project was planned for the former area of the Walton airport and plots were auctioned earlier this year. Part of the CBD’s plan was to provide direct access to major arteries such as Ferozepur Road and Main Boulevard,” says Dr Umair Javed, assistant professor of Politics and Sociology at LUMS.

Despite all of this, the CBD does to some extent help with the concerns many have had about Lahore’s reluctance to adopt high-rise development. And we are not just talking malls when we say high rise commercial buildings – we mean office buildings and business parks as well.

Why is this so?

The answer is very simple: Pakistan desperately needs thriving urban centres. Cities, after all, have an important role to play in the economic fortunes of the people that live in them. Pakistan’s urban population is currently 37% of the entire population, but it contributes a massive 60% to the national GDP. While those in the rural areas producing agricultural products are doing massively important work in terms of providing food security and producing actual products, there are so many in major cities in the service sector that are contributing to the economy. However, if they are to continue doing this effectively, they need to have comfortable living conditions, healthcare facilities, as well as recreational facilities. Similarly, for those people that want to set up businesses that will employ the people that want to work in the services sector, then they will need places to conduct their business, offices, and centres with friendly by-laws. That is essentially what the Punjab government wants to build with its ideas for central business districts.

“We need to give comfortable spaces to the urban population to work in. If we are to foster economic growth and activity, then we must encourage it. We need to provide a suitable ecosystem, and infrastructure to support people doing business,” says Imran Amin, CEO of the LCBDDA. “Our goal is to make Lahore a commercial economic city. The CBD in Lahore will definitely play a vital role in economic growth with attracting people seeking business and job opportunities. We do not want to limit ourselves to just providing office buildings and being done with it – a central business district in my conception provides exceptional business openings as well as offers effective working, living and playing spaces through quality urban design.”

Feasibilities out of whack

Is this massive construction undertaking feasible currently? Be it a government-backed project like CBD or private high rise residential housing developers? Not really!

The fact of the matter is that multistorey structures require much more steel. For a typical apartment building’s gray structure, 50% of the cost is made up of steel. For residential houses, this figure is closer to 25%. Right off the bat, going by the increase in the price of steel since 2021, apartment building developers are looking at a higher per sq. ft rate to finish their gray structure. In absolute terms, in 2021 the per sq. ft rate for a highrise building’s gray structure was around Rs 1600-1800. Currently this is at Rs 4500-5000.

As for residential housing, since they are using 25% less steel, gray structure cost has not shot up proportionate to an apartment building. Additionally, there is the consideration for timelines as well where apartment developers are again at a disadvantage. Building a 10-marla house in a posh area like DHA Phase 5 for example, will take between 10-12 months to complete and move into.

Comparatively, an apartment building with 6 floors and a basement will take up to three years to be complete enough for anyone to realistically move in. This opens up developers to all sorts of market risk, especially in an economy with such rapid price fluctuations. What is more, many of the finishing materials being used in the projects we have mentioned so far are imported making the finishing rate per sq. ft susceptible to rupee depreciation. Back in 2021, high end finishing would cost anywhere between Rs 2500-3000 per sq. ft. Currently this rate is around Rs 5000 per sq. ft. And these cannot be cut down by much. Developers are bound by what they’ve committed to customers at time of selling. Apart from sticking to the agreed per sq. ft rate of the sale, they have to deliver a minimum quality of finishing. They simply can’t ‘cheap out’ and deliver a substandard product. Not only would that be a breach of contract but also carries a reputational risk if they plan on remaining in the same business. However, one would assume, for many new entrants, this could be their first and last project.

Apartment building developers are therefore looking at a total construction cost that is upwards of Rs 10,000 per sq. ft. Add a pretty penny for marketing and miscellaneous costs on top, and the entire feasibility made two years ago becomes more or less redundant. Of course, if they are able to sell their units at the revised rates, then they’re still in the green, making the same margins and return on equity. But this is easier said than done. Demand is low.

Back to the Old House

The business of plot trading, house flipping and building homes for the purpose of selling to end users has also taken a beating, but a less intense one, as compared to apartment buildings. Not only is the gray structure cost less, as explained above, but the finishing cost is also much more manageable. Anyone building a house, either to sell in the market or for personal use, can always choose to use local finishing material over imported items in order to remain within budget.

There is the additional advantage of keeping one’s own timelines, more so for someone building for themselves but also a seller, as he will only be able to market it once it is finished. Plus, the land is the developer or homeowners asset, and it will hold a significant amount of its value, even in the worst of market conditions.

This price differential is reflected in the numbers as well. A reasonably comparable house to a 3-bedroom apartment in Gulberg would be a 10-marla home in Phase-5 DHA (ground plus first floor, no basement). The total covered area would be around 2450-2500 sq. ft (1425 per floor), with an open area of around 370 sq. ft for a two car parking. The personally owned space for the apartment would be around 2150-2200 sq. ft. Add parking for two and a servant quarter; the covered area adds up to the same, give or take.

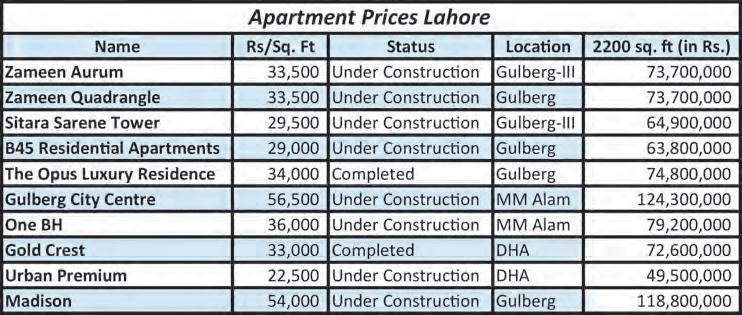

The following graph shows the price trend of finished and sold apartment projects in Lahore from 2017 to 2023.

Prices have steadily increased over the years but the severity of the hike between 2021 and 2023 is much less owing to reasons already mentioned above.

While there is an aspect of a slow and oversupplied market to this as well, with individual investors and home buyers waiting and watching for an indication of stability in the economy, an average buyer is definitely looking at prices with value in mind.

Dealing in absolutes

Imagine a family that has recently moved to Lahore, a couple with two kids, looking to buy a place, considering either apartment living or a ready to move into house in an upscale posh a conservative estimate would be around Rs 33,000 per sq. ft, translating into a buying price of Rs 76 - 77 million.

Comparatively speaking, his research on a similarly sized house (the 10-marla comparison we mentioned above) will cost him somewhere between Rs 54 - 56 million.

Not just about the price

With such a high delta between prices for an apartment and a ready to move into home, the choice should be quite clear. Right? Well, not really.

This is where personal preferences and a willingness to pay a premium for certain style and culture of living comes in. For the price sensitive types, it is a no brainer, but for a buyer who has perhaps lived the apartment life, moving from abroad or even as close as Karachi where it is much more common to own an apartment than a house, he might just cough up that extra cash.

But for the purpose of this article, our contention is that the apartment living culture in Lahore that was all set to take over the housing market, will have to wait until the economics of it all start making sense again. And this has already begun.

Apart from incomplete project onhold or unsold inventory, sources in LDA told us that there are developers who have bought plots for the purpose of building apartments but have delayed plans, which is evidenced by the fact that the volume for approvals has gone down considerably in 2023 as compared to 2022.

In comparison, the price trend for 10-marla homes in DHA phase 5 shows less variance over the same time period. (Date from Zameen.com index pricing).

neighborhood. Their research for apartment prices will bring up something similar to the following:

Profit conducted the same research as a buyer. Although there are some outliers in this list with very exorbitant asking prices,

There is still a market for apartments, just a shrinking one, where selling will become very difficult and new projects scarce, at least for the foreseeable future. n