18 minute read

How the two and three wheeler industry, not cars, hallmark of Pakistan’s automotive sector became the

Amidst economic turmoil and factory shutdowns, the two and three wheeler industry has casually carried on whilst its four wheeler counterpart continues to flounder

By Daniyal Ahmad

Advertisement

In Pakistan, the tale of two related industries unfolds like a family drama. The elder brother, the beleaguered four-wheeler vehicle industry, receives attention and investment but struggles to keep his head above water in a tempestuous sea of financial troubles. In contrast, the younger brother, the flourishing two and three-wheeler vehicle industry, thrives in the shadows. The brothers’ contrasting fortunes reflect the starkly different paths of the industries they represent.

Despite grappling with formidable economic challenges and a parched desert of letters of credit, the two and three-wheeler industry perseveres. It has been shattering sales and export records for years on end, while the four-wheeler industry only made national headlines with its inaugural export in 2022. Unlike its elder sibling, which has suffered innumerable plant shutdowns amidst the current economic maelstrom, it continues to prosper.

The two and three-wheelers are the sole beacon of hope in Pakistan’s automotive industry. They exemplify Pakistan’s unwavering aspiration for localisation. This is the story of how the unheralded brother harnessed the power of localisation to become the lone bright spot in Pakistan’s automotive history while the other persists in blaming macroeconomic shortcomings.

How good are the two and three wheeler industries?

“In normal circumstances, when left to natural forces, this industry is guaranteed to grow. It could even become a net exporter for Pakistan,” says Almas Hyder, Chairman of the Engineering Development Board. Why is that? “Volumes have risen to such a level and localisation has reached a point where the chances of this industry getting into difficulties are very remote,” Hyder continued.

So what are the localisation numbers that we’re looking at then?

“Atlas Honda leads the auto industry in localisation,” says Afaq Ahmed, Vice President of Marketing at Honda Atlas. “Our best-selling 70cc category has a 94.5% localisation level, while the 125cc category is at 92.4%. However, modern and higher cc series models have lower levels, ranging from 70 to 85% due to lower volumes,” Ahmed continues. Other players in the market are not too far behind either.

“All local 70cc bikes are roughly 85 to 90 percent localised. While we have stopped making 125cc motorcycles altogether, when we did, the numbers stood at 65-70% in terms of localisation,” says Fahad Iqbal, Director at Ravi Automobile. The three-wheeler industry is similar to this as well.

“Localisation in the three-wheeler industry is an old story; everything is local now. Three-wheeler rickshaws, or taxi rickshaws as they’re known, have been completely localised. All we import in terms of parts is the engine, but the rest is made here,” says Ammar Hameed, Director at Sazgar. The significance of these numbers can only be appreciated when we compare them to their four-wheeled counterparts. According to the Auto Industry Development and Export Policy (AIDEP 2021-26), the Big 3 - Suzuki, Toyota, and Honda - have achieved over 50% deletion across most of their portfolio. However, some of the models on display are either out-of-date or have been discontinued. Newer models reset the clock in terms of localisation alone. Additionally, new entrants from the past five years are completely absent.

The peak for four-wheelers in terms of localisation figures is simply the norm in the two and three-wheeler industry.

How did the two and three-wheeler industries achieve what they have?

There’s a simple answer to this: volumes, and a bit of imitation.

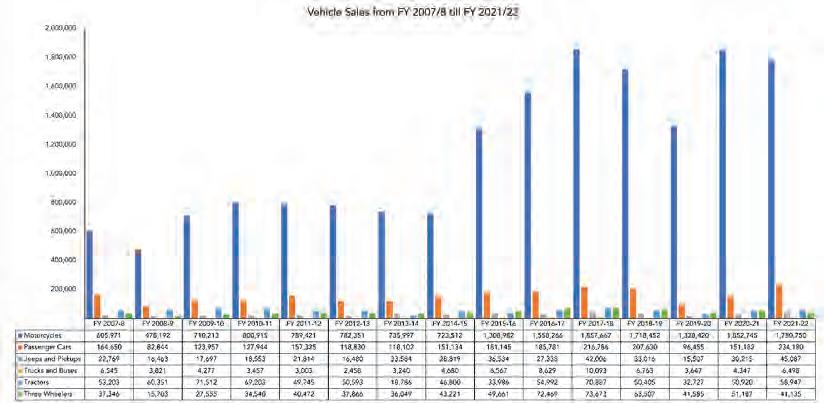

Data from the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association’s (PAMA) statistics from FY 2007/8 to FY 2021/22 show that they not only dwarf every other category of vehicle, but they also sell in excess of all other vehicles combined. Multiple times over. Three-wheelers in contrast are not as imperious.

However, the majority of the manufacturers from the three-wheeler market are also not members of PAMA. Furthermore, three-wheelers operate in a unique position whereby it’s a race to the bottom in terms of price due to the nature of the customers they cater to. Profit has documented this particular aspect in an earlier piece.

Read more:Electric rickshaws: Between Yellow-brick and Lytton road

Now, the imitation part. This is fairly simple. It’s a monkey see, monkey do kind of phenomenon at the base level.

“The motorcycle market is basically divided between Atlas Honda and Atlas Honda clones. We’re looking at a massive market that has identical components, irrespective of the brand that’s making it,” says Iqbal. “I think all the initial work for localisation was, frankly speaking, done by Atlas Honda. When the Honda clones came in, it accelerated that growth in terms of localisation because all of a sudden there was much more volume available of the same components, which of course encouraged the vending industry or the component manufacturing industry as well,” Iqbal continues.

It’s a similar story in the three-wheeler market too. “There are two prevalent designs across three-wheelers; ours and New Asia’s. All other players copy one of the two when they manufacture their product,” says Hameed.

“If the market for two and three-wheelers had featured a variety of shapes and designs, the level of localisation would not have been as high. Following the same designs has worked in the country’s favour by making the product affordable for consumers,” says Iqbal. “While some argue that customers want something different, everything comes at a price. If we had pursued different designs, the products would be more expensive, with lower volume and less affordability,” Iqbal adds.

How exactly does having similar shapes and designs assist with parts and subsequently localisation? “Vendors just need to make slight changes to their parts, and then they can sell the part to any manufacturer wanting to use it. The slight alterations also allow them to circumvent violating their contracts with any one manufacturer,” says Hameed.

“Localisation is usually the result of any one manufacturer in the industry acquiring and training the vendors, and then slowly more players enter the space,” Hameed continues. “Two and three-wheelers are also less complex than four-wheelers. A car has thousands of parts. Two and three-wheelers do not. They have fewer parts which makes them easier to localise and subsequently copy,” Hameed adds.

“It’s a similar case for any successful model in Pakistan. If you were to have a successful flower stall at Liberty Market in Lahore, then one day you’d notice that suddenly other flower sellers will pop up doing the exact same thing. People hop on the bandwagon for whatever is successful,” Hameed muses.

So is it just the fact that cars have more parts that makes them more difficult to localise? Though cars are not as similar to one another as two and three-wheelers, they’re also not that different from one another. Right?

Why haven’t cars pulled this off?

“The four-wheeler industry does not generate enough volume.

The Swift costs Rs 4,000,000; how many people do you know that will pay that much for the Swift? If there’s not enough volume, then localisation cannot occur,” says Hyder. “The four-wheeler industry still hasn’t crossed the 250,000-270,000 mark in terms of annual sales,” adds Iqbal.

“Even if the car market does cross the 250,000 or 300,000 mark, the sales will be divided over two dozen variants. This wasn’t the case a decade ago when you had just three assemblers providing a handful of variants. The volumes will just never make sense to localise,” Iqbal muses.

This then raises two questions: were the two-wheeler and three-wheeler industries always destined for success? And why do they not get enough credit for what they’ve achieved?

Let’s start with the first question.

The simple answer to this is no. “Imagine a Pakistan that had a very strong public transport system or very high income levels. These markets would not be what they are then,” says Iqbal.

Short and simple.

Now onto why these two industries do not get the attention they deserve?

Suffering from success

The simple answer to this is that the two and three-wheeler industry simply do not evoke the same level of excitement or curiosity as their fourwheeled counterparts. The CD-70 is iconic in Pakistan, but social media is not filled with pages dedicated to it in the same way as those dedicated to luxury imported cars. Similarly, three-wheelers are perhaps the backbone of Pakistan’s transport infrastructure, but cars dominate every press conference relating to road construction and expansion.

Two and three-wheelers are utilitarian vehicles at the end of the day whereas cars are, for the better part, a luxury in Pakistan. The stats speak for themselves. The Pakistan Social And Living Standards Measurement (2018-19) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics identifies 54% of all Pakistani households to have motorcycles, whilst only 6% of households have cars. A utilitarian product will simply never turn heads the same way a luxury product will.

Honda knows that their newest Civic will always grab more attention than their CD-70, and Sazgar knows this to be true in terms of their H6 relative to its three-wheelers. However, that’s not to say the two and three wheeler industries haven’t tried to change this. It’s just that they simply cannot. What do we mean here?

“New models face challenges when entering the market,” Ahmed tells Profit. “They require new parts that aren’t available in Pakistan, forcing companies to invest large sums of money. Additionally, localisation must begin from the onset of the new product, further increasing costs. This makes it infeasible for customers accustomed to low prices to purchase them,” Ahmed explains.

“When manufacturers want their vendors to make new parts for them, they have two options,” Hameed explains. “They can either bear the tooling cost themselves and upgrade the vendor, or they can amortise the vendor’s cost by allowing them to charge a higher price for a certain number of units to recoup their expenses,”.

“This decision forces companies to undertake demand and cost forecasting,” Hameed continues. This is, however, an exercise that simply makes no sense given the current state of the two, and three wheeler industry.

“Why would a company want to invest in a new model if their current product is selling well, efficiently designed, and supported by a network of dealers and mechanics all over the country?” asks Iqbal. “If at least 95% of customers are happy with the product, why spend millions of dollars on something new?,” Iqbal adds.

Is there anything the government could do to maybe make these industries more glamorous so they can receive the attention they deserve? Well, yes. There is one way the government can reduce the costs of compa- nies wanting to undertake modernising their models. Repeal Statutory Regulatory Orders (SRO) 693, 655, and 656. What are these one might ask?

These SROs cumulatively comprise the policy framework for levying duties upon automotive parts imported into Pakistan. They are also what make the new models of vehicles everyone wants more expensive according to Ahmed.

The answer then would be to just repeal them right? We’d all get the Hero Honda motorcycles that our neighbours across the border enjoy. It’d also make Sazgar’s fancy new electric rickshaws more affordable for everyone. However, the decision is not that simple.

“Eliminating the SROs would mean that we no longer want to be a country that manufactures components for these products,” says Iqbal. “Removing the SROs is not good for the country. The local industry thrives because of them. Manufacturers and vendors hire more people and create jobs,” says Hameed. “If we were to do away with the SROs, the base price of products would decrease, benefiting companies, but Pakistan would become a trading country,” Hameed adds.

“The volumes are there. If foreign players want to enter the market or if companies want to innovate, they should focus on localising everything. If you’re willing to localise everything from day one, you’re likely to capture a reasonable portion of the market,” says Iqbal. “These SROs do add a higher cost for manufacturers, but it’s a cost worth bearing for the overall benefit to everyone,” says Hameed.

Imagine being so successful that you suffer from it. That’s the story of these two industries. They’ve honed their skills to perfection, yet they may never receive the recognition they deserve. Why? Because they’re content with the way things are. But will this always be the case? It’s unlikely. These industries march to the beat of their own drum and will change at their own pace and on their own terms, unlike their four-wheeled counterparts. n

By: Momina Ashraf

New York, Paris, Milan . . . Lahore? Pakistan’s lawn craze creates a new style capital in the world. Although not a fashion week, the lawn collections, perfectly aligned with Eid, is a semi-annual fashion festivity, much like the well-attended fashion shows. It’s the perfect time for newcomers to map their presence, established ones to set the benchmark higher and forgotten ones to get back into the game.

Every year the three-piece suit takes on a new style. From choori daars to shararas, cotton dupattas to organza silks, self-print to embroidery, the lawn collection is as unique and as embellished as any high-end designer wear. Every year, as the pack of lawn suits gets heavier with necessary embellishments and motifs, the tag also gets pricier.

But here’s the catch, people still want to buy it.

“Please find out the science behind how the dresses get sold out within a few minutes of launch,” snarked Lubna Qayoom, an average lawn customer, on an all-women Facebook group where Profit reached out to the target audience.

The booming fashion industry

Pakistan’s fashion industry is one of the rare industries that is doing well in the prevalent economic climate. Back in parents’ generation, the fashion industry catered to just a few - the high-end socialities and celebrities. It was unheard of having a branded suit for Eid, let alone designer wear for a regular get-together.

However, with time social dynamics changed and the country saw a rise in the urban class, working women, and an increased disposable income. This led to the expansion of the fashion industry’s consumer base. Slowly, brands like Khaadi, Alkaram and J. came to the forefront.

Apart from this, by 2017, a dip in textile exports forced the big names to bring the middle class within its fold; this has led to increased competition and production in the lawn season, the products of which are much in demand almost throughout the year. In fact, several textile manufacturers such as Sapphire and Nishat textiles launched retail brands with seasonal lawn lines.

In April 2021, the export value of the textile and clothing industry stood at $1.3 billion, reflecting an increase of 231% from $403.8 million in the corresponding period of the previous year. The growth has been attributed to the Economic Coordination Committee’s approval for import duty-free cotton yarn until the end of June 2021.

From buying yearly Eid clothes from these brands to buying even casual wear for home became the norm. The mainstreaming of brands led to another phenomenon, designer wear. Designer clothes, such as Élan, HSY, Maria B. which were limited to ramp walk models became available to women of upper-middle and upper-class families. The designer lawn, in essence, truly made the dream of magazine glamour a reality.

The designer lawn craze

“Even when we design, the main thing we keep in mind is that it is not for ordinary citizens. Women buy designer lawns just so they can show they are wearing designer lawns,” said a designer from Zara Shahjahan, who wishes to stay anonymous. “Designer lawn is the local version of rich people wearing Dior and LV abroad. It’s about showing, without having to say that you have taste and class,” she continued.

Profit learned that designer lawn, as the name suggests, is a careful curation of embellishments, thread work and colours and its preparation takes up to a year.

“The lawn category has designated 12 designers. Zara encourages all junior and senior designers to create and design. Every year a new designer gets a chance to make it to the final collection. The team sits and plans and works and reworks,” explained the designer. “The lawn designs are created with the intention of introducing something new in the market. For example, we were the first ones to introduce matching basics and now everyone is doing it. Zara Shahjahan sets trends so we have to be ahead of the game. Some pieces follow the already set standard, but there always has to be something completely new as well,” she added.

The lawn season is the busiest for designers, more than the bridal season. By the time of the launch, all departments come together to sell the product because of how much traffic there is. “And it sells, within days and some- times even on the first day,” explained a source . So who is Zara Shahjahan’s biggest competition? “Élan!” blurted the source. “We do not only have to look after our own launch but keep track of Élan’s also. Only they are our direct competitors in lawn,” she pointed out. Élan, a luxury designer brand launched in 2004 is the brainchild of Khadijah Shah. Although kickstarted off with luxury couture, in 2012 the brand spread its wings and ventured into the lawn market. It was to cater to a wider audience, while still maintaining a bit of a niche. “Our target audience is the upper class so inflation did not impact them. We saw a slight dip in other collections but for lawn, the demand is the same as before,” said a designer from Élan, who wishes to stay anonymous.

Most designers do not have their own mills and outsource raw materials from other mills. In the planning process, a sample of fabric is ordered from the mill and dyed inhouse. “They give us samples and we give them business,” that’s the usual practice, informed the anonymous source from Élan. “We order samples and dye and print them. If approved we make the business deal with the 1,5002,000 orders and the sample price is adjusted within it,” she explained.

It is pertinent to mention here that Élan was bought by Sefam group in November last year. While under Khadija Shah, Élan partnered with Sapphire Textile as a backward integration for a steady and high quality supply of the in-demand lawn fabric, while Sapphire used Shah’s creative impetus to further their retail aspirations. It worked for both parties involved, until it didn’t.

Profit did a feature piece on the Élan-Sefam deal with details of the Sapphire-Khadijah Shah arrangement as well based on an interview with Shah. Read here.

Once the collection is made, its launch is nothing short of a release of a bigscreen film. “The hype starts fifteen days prior on social media and our websites,” said Minahil Khan, Growth Associate for LAAM, a one-stop online store for fashion brands. There are photos, sneak peeks, trailers and reels shot from picturesque locations. On the website, there’s a countdown running on the last day, and some even have the option of pre-order.

“It’s crazy on the day of the launch,” mentioned Khan. If it’s a hit collection it will get sold out within days earning an average revenue of 30 million. And if it’s not, the articles will remain unsold even by the end of the season.

“We have to carefully market them, and let people think that something major is coming,” mentioned the source from Élan. That’s why the marketing costs are the heaviest in the entire process. “We decide the model and location during the ideation phase of the collection. The pieces are made specifically for certain faces and celebrities which we know will bring life to it,” said the source from Zara Shahjahan.

Upon asking, Zara Shahjahan did not quote their marketing budgets but according to Khan from LAAM, the campaign budget for lawn alone costs a minimum of Rs 100 to 200 million. “If the campaign takes a major celebrity face Rs 20-50 million is allocated for that only. Although the costs can vary a lot, for example, if the shoot is international then it’s a different ball game. But the minimum slab is somewhere around Rs 20-50 million easily,” she explained.

The cost of raw materials and production goes up to about 150 to 200 million for a single lawn collection. But then there are other costs too which include utility, staff and a lot of other administrative costs. Designer lawn pieces, according to the source from Élan, earn a margin of almost 50%. It essentially includes the labour employed at every stage from ideation to distribution. A limited quantity, around 300-400 of such pieces are made, and the price tag, which now exceeds almost Rs 20,000, is there to maintain exclusivity.

Is lawn really a cash cow for clothing brands?

“It’s not,” simply replied Amir Rasheed, business manager for Mahgul Designer Studio. Lawn is not only becoming expensive for the customer but even for the designer. “There’s a lot of units involved in making a single design of lawn. Textile mills, dyeing mills, printing units, embroidery houses, stitching, packing and a lot more. The costs at each stage are increasing. In the end, it’s a piece of lawn for daily wear, not luxury wear,” he explained. “We don’t think that designer lawn is the thing of the future. It’s too much money and hassle for the customer and for us. Lawn fundamentally is a light piece of clothing for summer, not a suit which is just one step below a wedding dress. Lawn’s disposability and rapidly changing trends don’t make the cost and price not worth it,” he continued.

“Even the 30-50% margin designer lawn earns is not realised into profit. From these margins, almost one-third goes to GST and a heavy proportion for marketing and selling. At the end about 10-15% is left from a 30% margin only”, said Rasheed.

The lawn market is immensely competitive. Every brand has a special focus on lawn and since they know they want to make it accessible there is only so much profit they can make out of it. “Even these profit margins for designer lawns are limited,” said Khan. “The profit margins for luxury and bridal collections are way higher. In every process, you have to cut above the rest.”

The real craze for lawns comes not from exclusivity but from accessibility. The big giants in the market, such as Sapphire, and Alkaram have their own textile mills, which takes production and revenue to a whole new level.

They are a tier below the designer lawn which focuses on a much wider consumer base. Brands such as Sapphire enjoy mass popularity and their way of doing business is also different. In conversation with Bilal Ashraf, lead designer at Sapphire, we learned that for retail brands the profit margin is usually 30-40%. That’s because the brand has its own textile mill and from embroidery to dyeing to weaving, everything is sourced and completed in-house.

Mill-owning brands produced at least 1,000 units of each lawn article. If a certain article gains popularity, its production doubles and is sometimes continued in the next collec- tion as well. “There’s a lot of profit margin in lawn. For such brands, lawn is the business’s cash cow,” said Khan.

“Our main aim is to cater to the needs of the customer. We know what they want and we cash in on that. While designing, there’s a set category too. There’s a triangle we often refer to in the process (see below). The widest range, the base, is made up of the ‘essentials’ which are everyday wear for college students and working women starting from Rs 990. Then there is ‘commercial’ which is a bit fancier, with slight embroidery and on average cost around Rs 4,400. Essential and commercial both follow the already set designs and styles. Then the tip of the triangle is for ‘directional’, where there is room for experimentation and setting new rules. Such collections usually come around the first volume,”

Exports

The furore with lawn business has shaped the industry in a manner which produces a complete package for international sale. If India is known for its banarsi saree, Pakistan is known for its lawn shalwar kameez.

In a story previously done by Profit, it was reported that over the past two decades Pakistani lawn has become a $54 million market in India. There is often a shortage of Pakistan-made lawn suits due to high demand and a shaky supply chain. But due to unreliable bilateral trade relations with India, the middlemen in the business become the real winners. “From our experience, most of the brands don’t prefer selling directly, especially internationally. We have sent multiple emails to their sales team but they don’t seem to respond,” says Akram Tariq Khan, co-founder of Your Libas, an Indian online marketplace for Pakistani suits and kurtis in India and the rest of the world. “At the end of the day, there is always a middle-man ready to facilitate the deal – an approach that is unprofessional and unorganised.”

The situation in other countries is much better though. Around 10% of Élan’s lawn collection is sold internationally, specifically in Dubai, the UK and the USA where there is a massive desi community. “With currency depreciation, the sales might have actually increased a bit because for them it’s a lot cheaper now. Inflation didn’t impact them,” mentions the anonymous source.

This is something which many brands can profit from, but the textile industry itself is not in the right place. Back in 2019, Shahid Sattar, an advisor at All Pakistan Textile and Mill Association (APTMA) told The News, “One can’t export it if the cost is higher than other countries and the cost of doing business is higher in Pakistan at the moment. Yarn, the raw material for lawn, is imported, so the final pricing depends on import duties as well.”

Since then, things have massively changed. In the current situation, exports have declined by 12% due to a shortage of raw materials. Due to the floods, the cotton crop experienced immense damage and against the requirement of 14 million bales, the country could only produce 5 million bales of cotton domestically. Owing to low foreign exchange reserves and curbs on imports, cotton could not be imported as freely and readily as required. “We have had to keep the profit margins low this time, somewhere around 15% because the industry is not in good shape. This year the retailers are bearing the brunt of the higher costs of doing business, let’s see how things progress further,” mentioned Ashraf from Sapphire.

Profit reached out to APTMA for a comment, but did not receive any.

So coming back to the fundamental question? Is a lawn suit worth the price? Just like any other fashion piece, its ‘worth’ so to speak is determined by consumer perception and demand. Lawn, although highly disposable, is taking new shapes and designs to maintain luxury and innovation.

And it works well. In a country, where there aren’t many avenues for leisure for women, shopping is a safe and suitable option where the affordability and variety of lawn fits the equation very well. n