CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND PRESERVATION PLAN

RUBEL CASTLE HISTORIC DISTRICT

GLENDORA,CA [21345] Prepared for: Glendora Historical Society

MARCH 18, 2023

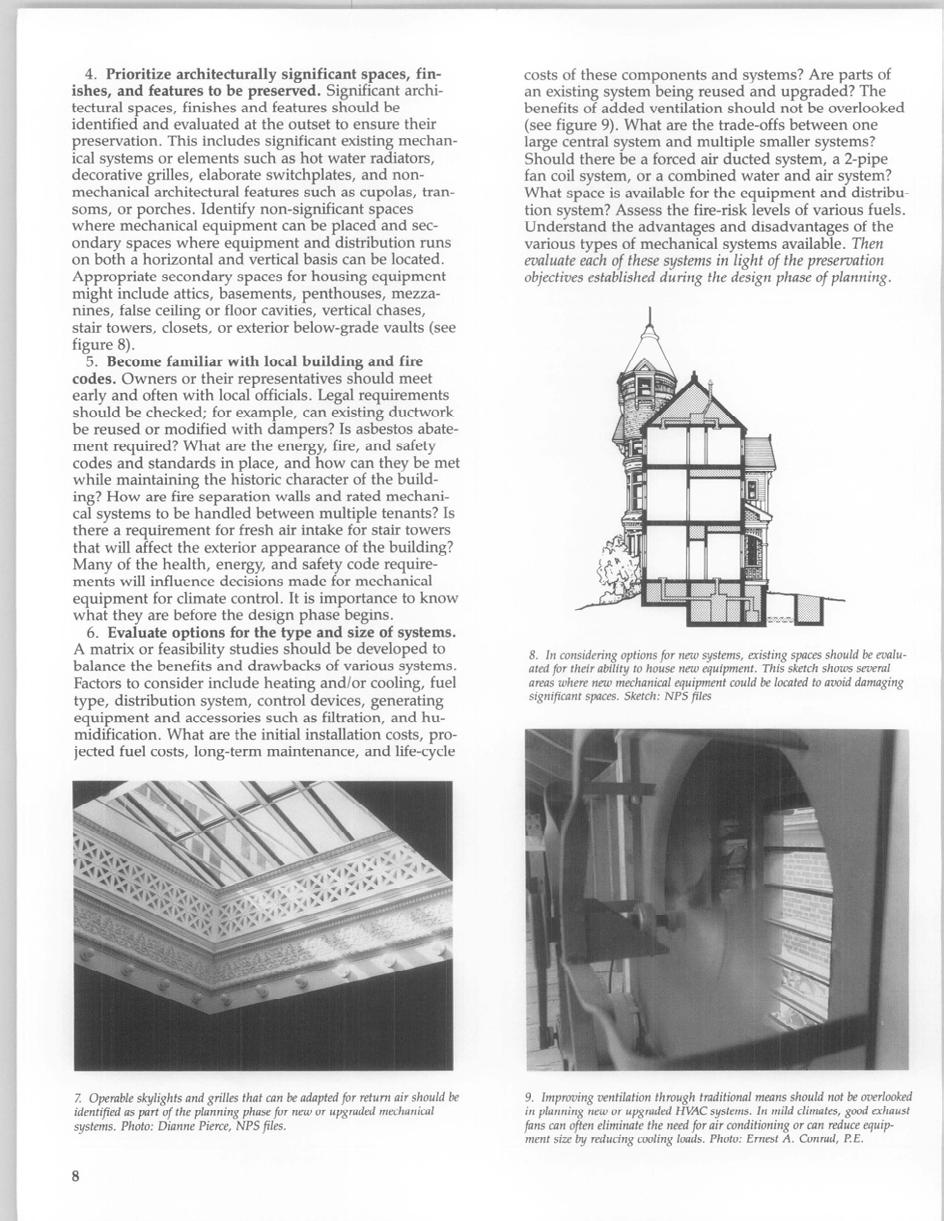

This Page Intentionally Blank

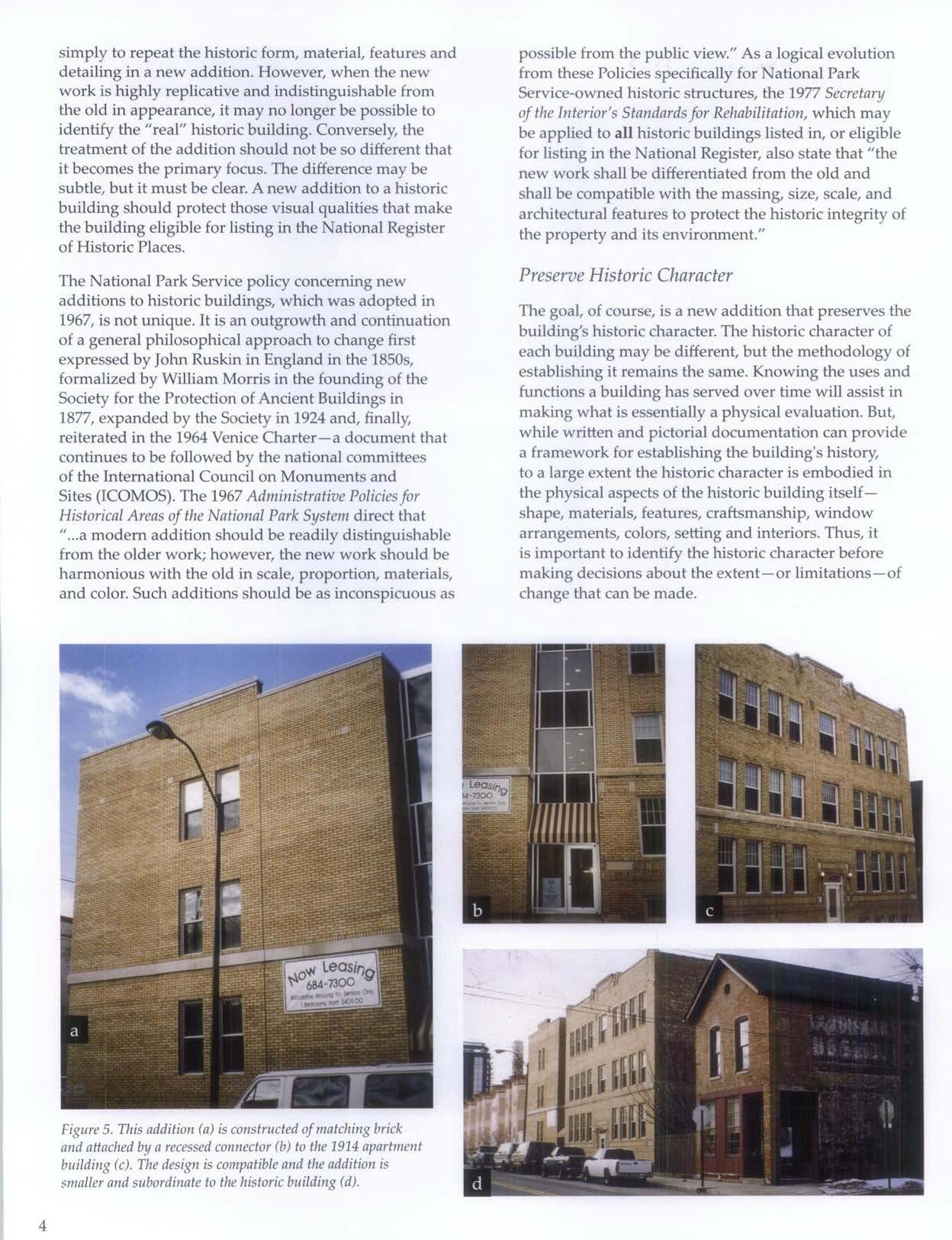

OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS- CONT.

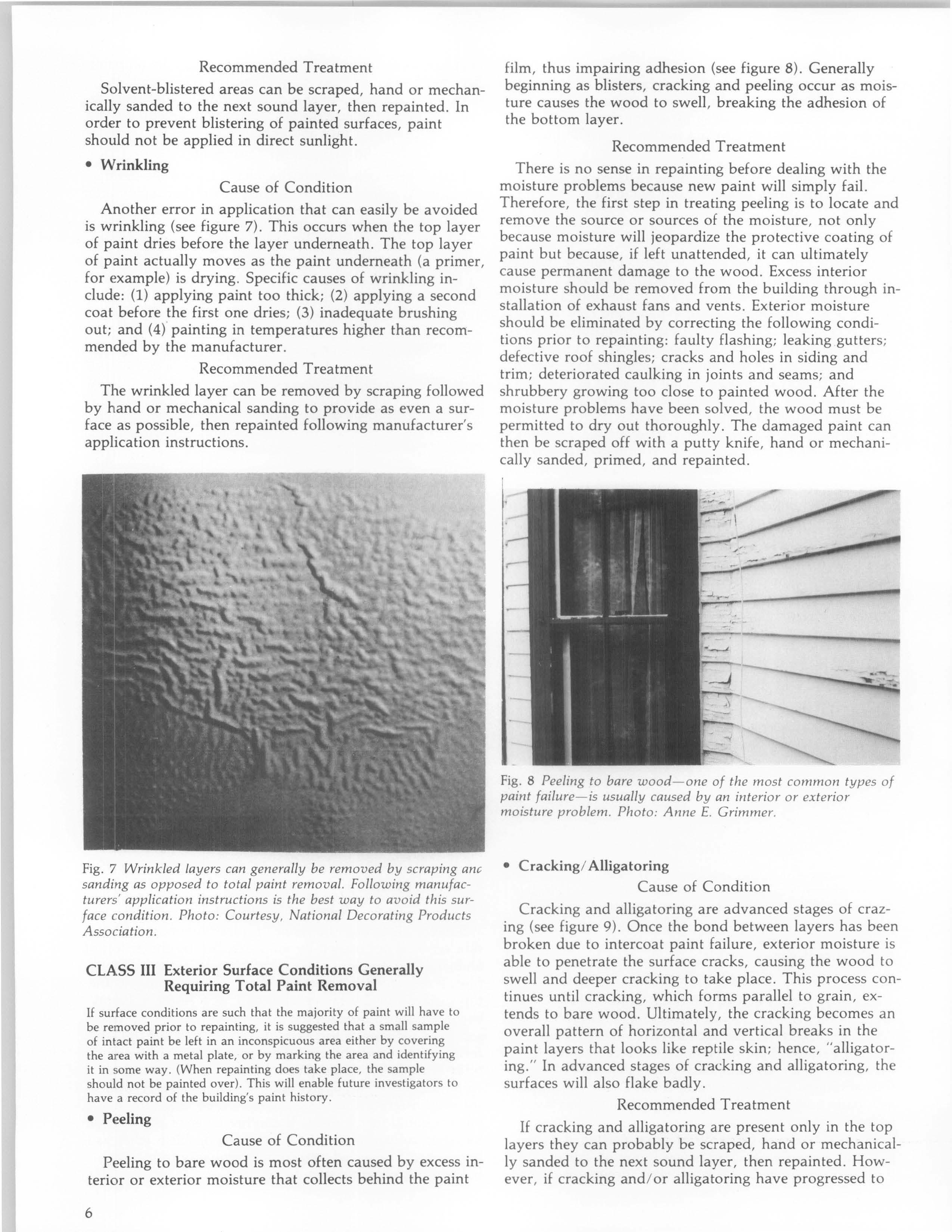

APPENDIX B. RESOURCE AND SPACES LIST

APPENDIX C. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

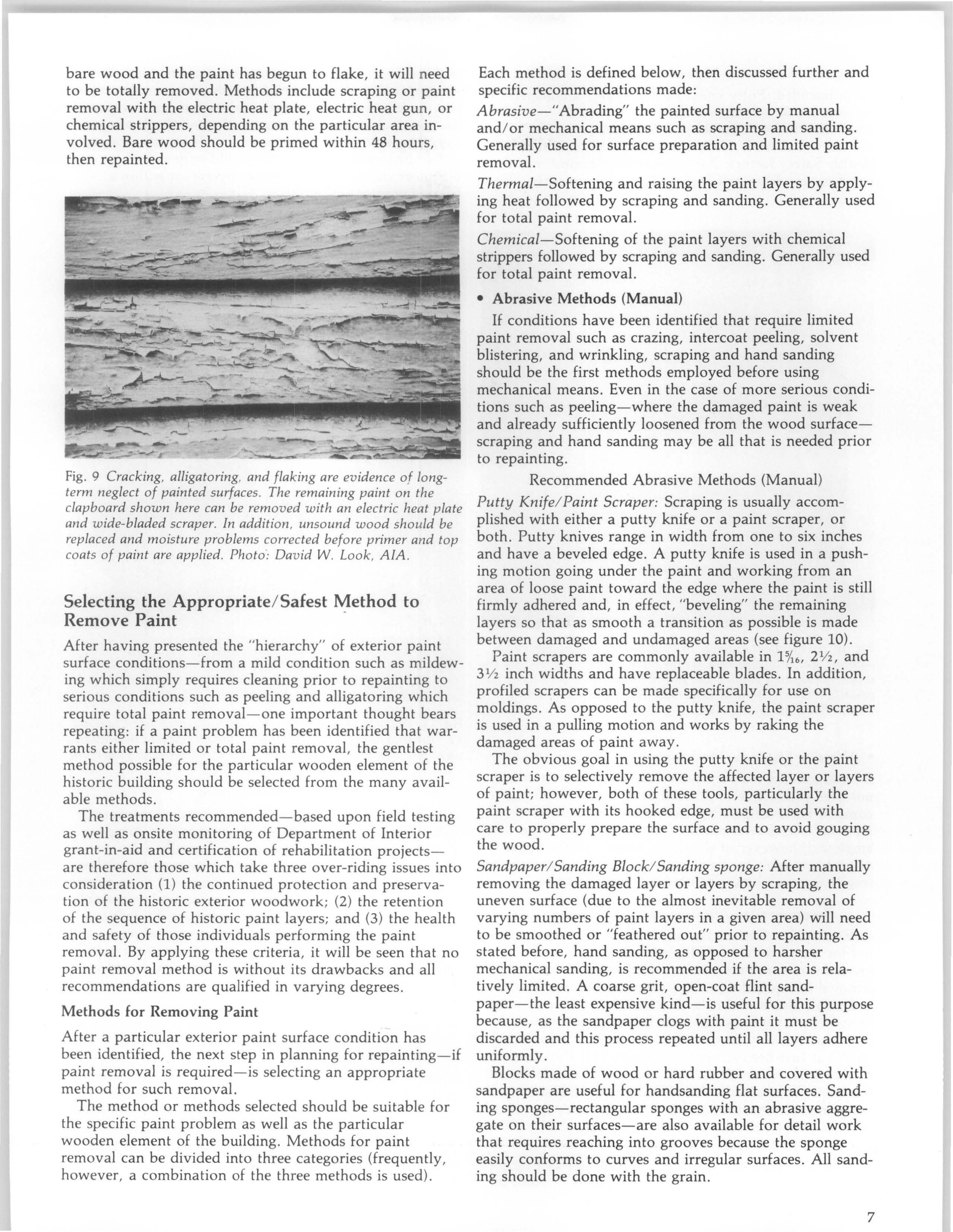

#3 – improving EnErgy EFF C EnCy in historiC buildings

#9 – thE rEpair oF historiC woodEn windows

#10 – ExtErior paint problEms on historiC woodwork

#14 – nEw ExtErior additions to historiC buildings

#24 – hEating, vEntilating and Cooling historiC buildings

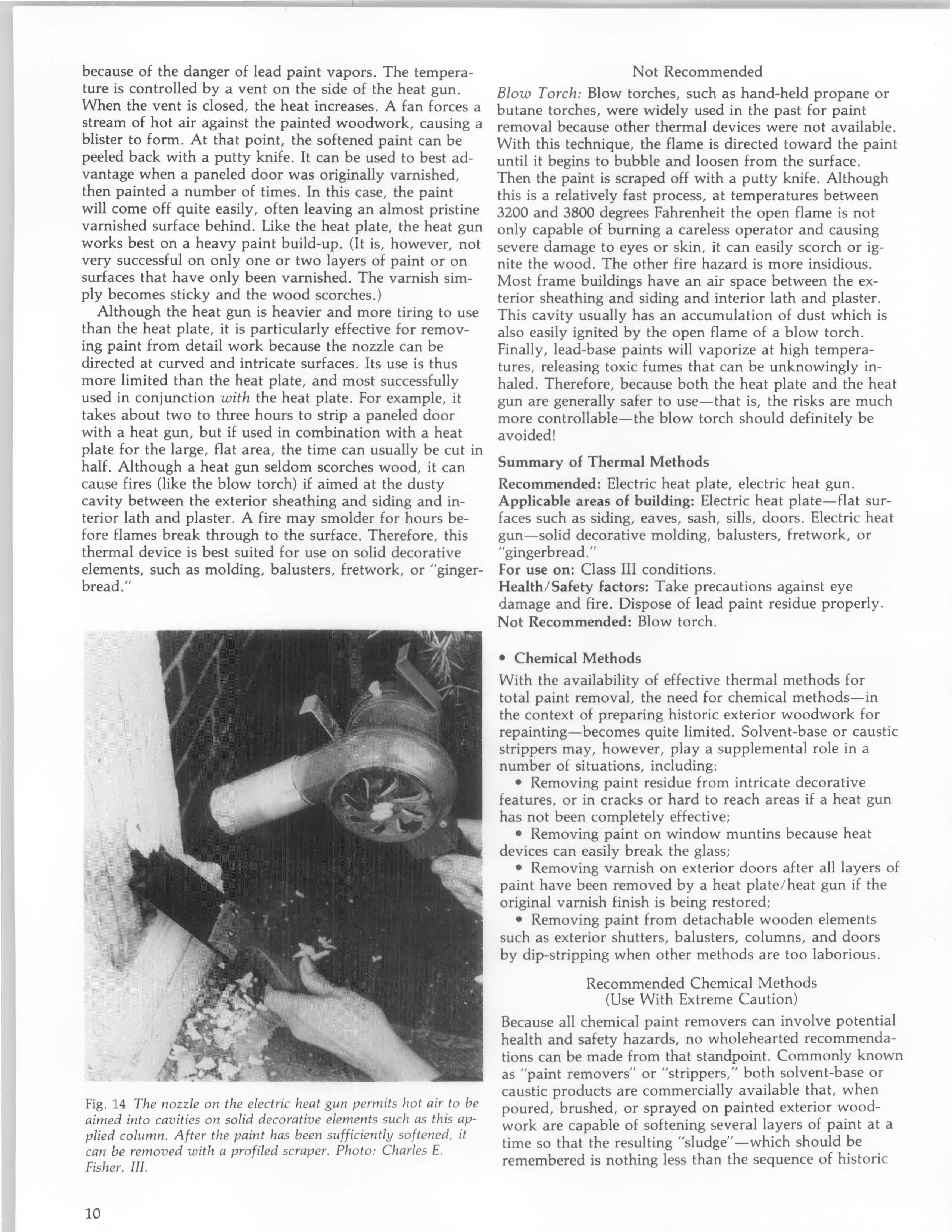

#32 – making historiC propErtiEs aCCEssiblE

#39 – Controlling unwantEd moisturE in historiC buildings

APPENDIX D. CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT REPORT

(LAYER REPORT) (PROVIDED AS SEPARATE DOCUMENT)

APPENDIX E. RCHD NPR FORM (NOT COMPLETE)

PART I. INTRODUCTION

LOCATION

The Rubel Castle Historic District (RCHD) is located in the city of Glendora, California, near the San Gabriel Mountain foothills. It is part of Los Angeles County. Glendora developed amid the expansive citrus industry, which gave way to suburban development in the mid-twentieth century.

The RCHD is a 1.7-acre site located at the southeast corner of East Palm Drive and North Live Oak Avenue on the north side of the city. It is delimited by a perimetral wall to its north and west— with a chain-link fence that abuts single-family residences to its east and south. The site has two access doors that exit westward at the Main Gate onto North Live Oak Avenue. In addition, one small door on the site’s north side opens onto East Palm Drive.

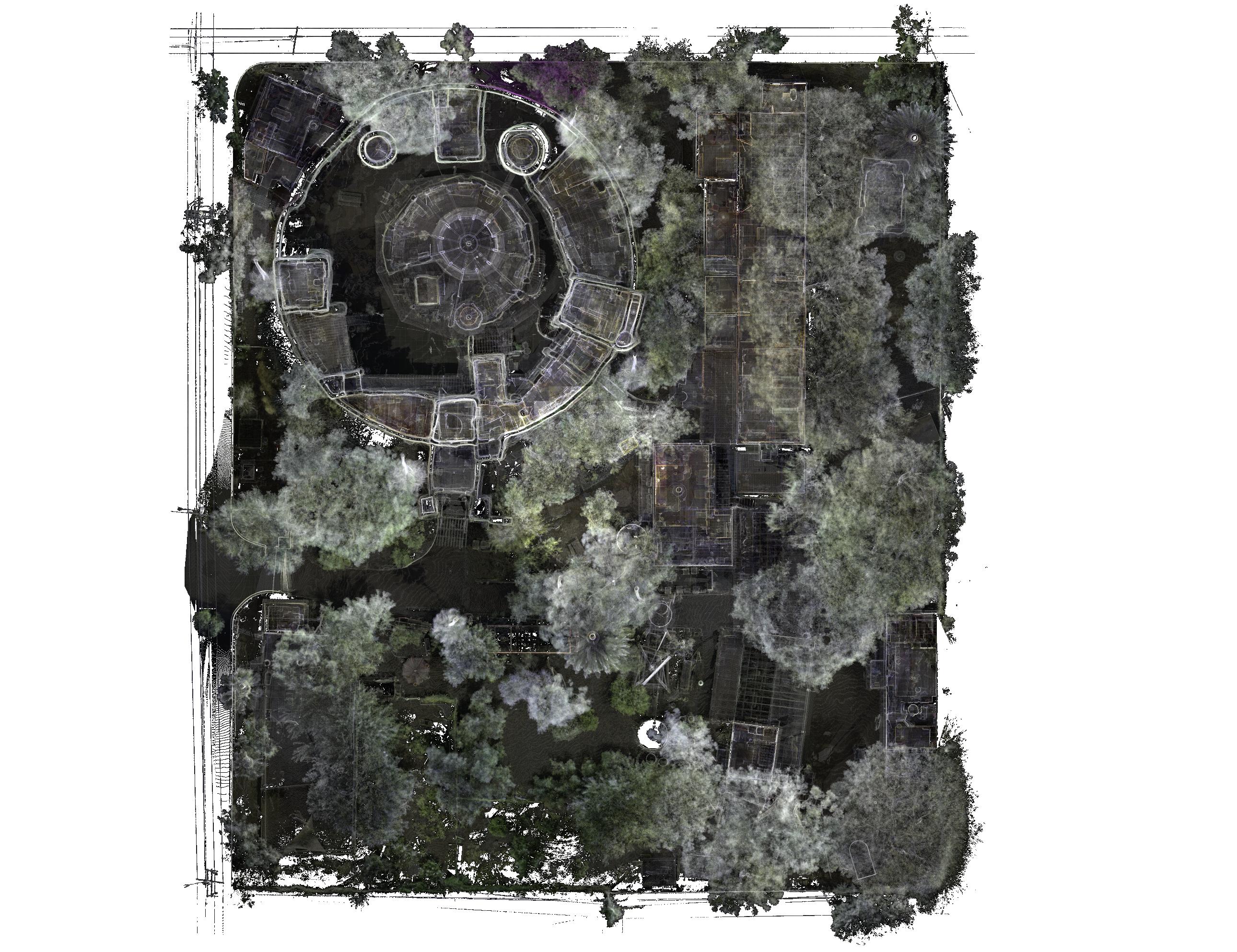

Figure 1. Site Map - Taken form Google Earth © November 2022

Figure 2. Aerial view of Rubel Pharms 1969, GHS Archives.jpg

PROJECT OVERVIEW

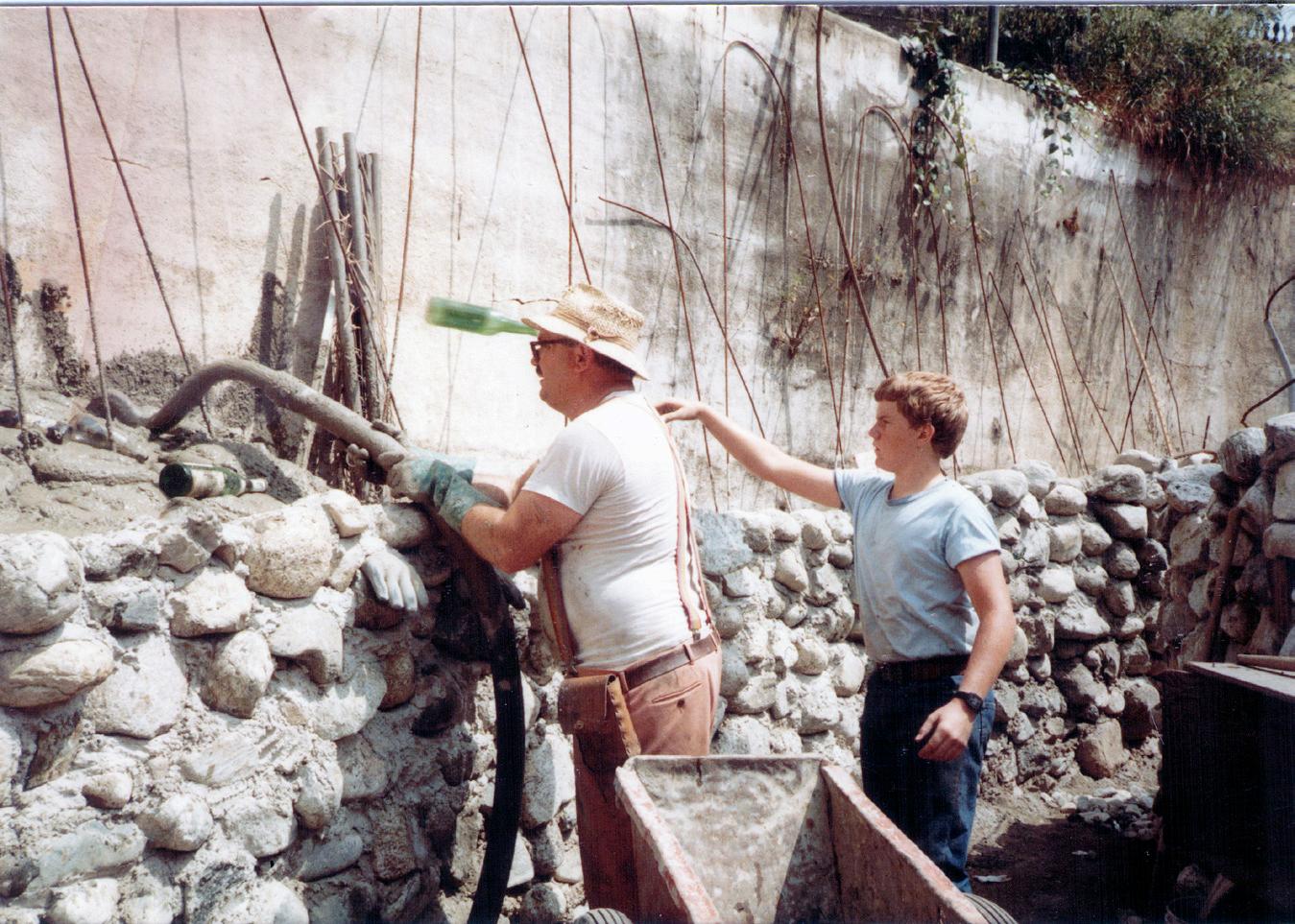

The Glendora Historical Society (GHS) asked Page & Turnbull to create this Preservation Plan for the RCHD, which is owned and operated by the GHS. “Rubel Castle”, also known as “Rubelia” or “Rubel Pharms,”1 is a self-contained site named after Michael Clark Rubel (1940-2007). Michael Rubel acquired the property and existing citrus ranch buildings in 1959. With no more than his own hands and the help of friends, workers, and family, Rubel modified the property by constructing several structures and a castle out of recycled, local materials (referred to as “urbanite”2 throughout this document) between 1960 and 1986.3

Rubel Castle remains widely regarded as a place where dreams are possible. It hosts a community of artists who live on the site. Artists work in the district’s workshop spaces. Such art, along with a vast collection of artifacts and memorabilia, collected initially by Michael Rubel, can be appreciated at Rubel Castle day tours.

The RCHD was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 3, 2013 (# 130008104). The 1.7-acre district contains fourteen contributing buildings and structures (as stated in the National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form). The site was found eligible under criterion “A” for its association with the California citrus industry, and under criterion “C” as a rare and excellent example of the folk-art environments of California. For this Preservation Plan, Page & Turnbull identified Character-Defining Features associated with both criteria.

RCHD resources are divisible according to their period of significance and eligibility criterion. All resources related to California’s citrus industry era are built on the east portion of the site—while most resources with unique Folk Art Architecture cluster on the northwestern corner of the site. By nature of the urbanite construction, all Folk Art Architecture resources have been affected by use and the weather over time. Structures belonging to the citrus era are in slightly better condition, though they have also changed over time. Because construction was performed without professional supervision, there is a lack of documentation regarding systems, structures, and infrastructure throughout the entire site. These factors present a risk to residents and visitors as well as the resources themselves.

The scope of this Preservation Plan includes fourteen contributing buildings and structures, along with eleven structures and landscapes not yet recognized as contributing. Eleven non-contributing structures and landscapes are included due to their association with the folk-art environment and their direct impact to contributing resources and the district’s integrity. Moreover, they are potentially eligible in the future.

1 “Pharm” refers to the production of oranges in the site, Michael Rubel’s friends are referred to as Pharm Hands.

2 Urbanite is a term that refers to broken pieces of unwanted leftovers from a demolition project. Urbanite can be locally sourced at construction sites, and is usually free if you are willing to haul it away.

3 Historic Resources Group, LLC. 2012. “Historic Designation - NPS Registration Form.” Glendora Historical Society Website. November 5. Accessed August 20th, 2022. https://glendorahistoricalsociety.org/rubel_castle_historic_district.pdf.

4 National Park Service. 13. “NPGallery Digital Asset Management System.” NRHP Registration Form. August 21. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/13000810.

Recommendations and guidelines found in this Preservation Plan correspond with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (The Standards). In addition, this Preservation Plan focuses on the Ad Hoc Committee’s suggested areas of investigation:

• Structural and life-safety hazards.

• Deterioration of wood elements

• Stone masonry construction

• Water intrusion and stormwater control at buildings

• Erosion and stormwater drainage at site

• Guidelines for building infrastructure repair and maintenance

• Guidelines for site infrastructure repair and maintenance

METHODOLOGY

The GHS through the Ad Hoc Preservation Planning Committee, which is part of the GHS, worked collaboratively with Page & Turnbull to:

1. Develop a methodology able to evaluate the RCHD

2. Develop priorities, and create a roadmap to execute treatments.

Prior to the formulation of recommendations, Page & Turnbull formed a basic and underlying understanding of the Historic District through the following:

• Identifying and listing historically significant spaces, spatial relationships, features, and materials (Character-Defining Features).

• Assessing and documenting conditions, including life-safety and code-related issues such as structural/seismic retrofit, disabled access, and/or fire prevention-egress.

• Reviewing traditional, current, and intended uses.

Page & Turnbull surveyed the RCHD during visits conducted between May and September of 2022. Prior to the site survey, the team reviewed all known reports supplied by the GHS and the Ad Hoc Committee and thereafter reviewed available drawings and diagrams of the site and buildings. Preparation for the assessment included a series of working meetings between Page & Turnbull and the Ad Hoc Committee.

During site visits, the team surveyed resources with the use of traditional methodologies, observation, and a cloud-based collaborative software (Layer App) to identify the following aspects and conditions of the site:

• Significance and Integrity

• Character-Defining Features

• Safety hazards

• Overall condition

• Infrastructure upgrade requirements

• Accessibility and egress conditions

PURPOSE

The purpose of the Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan is to document the property and provide useful guidance for the treatment of the buildings and landscape elements of the district. This document was produced at the request of the GHS and will principally be used by the Historic District management. The Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan will also be used by residents and private contractors hired to perform restoration, rehabilitation, preservation, and maintenance work at RCHD. The document is meant to provide baseline information to guide management decisions and aid in establishing prioritized maintenance and rehabilitation strategies for the district.

This report follows The Standards. Such guidelines and recommendations should promote safety, security, and accessibility while conveying the historic character of the RCHD.

The project team sought to create a practical document that would provide base guidelines and best practices for the preservation and rehabilitation of the Historic District useful for several years.

This document assesses Character-Defining Features and levels of significance to determine urgency and prioritize work to be performed in the RCHD. The main body of this report assesses overall condition and makes recommendations, and a more detailed Conditions Assessment Report is included as appendix D.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan provides the GHS and the Rubel Castle community with a framework to conserve and maintain the RCHD. This plan should be used as a starting point for developing strategies, programs, and schedules to conserve the livelihood and historic character of the district.

Part II provides the historic background of the district along with its general Character-Defining Features. These features are identified as the base for conservation efforts and prioritization stemming from the historical and cultural significance of each one of the resources. Character-Defining Features’ impacts must be considered before any upgrade or alteration is undertaken.

Part III provides the general conditions of the district at the time of the assessment in 2022. It sets the condition of “Fair” as an accepted baseline for any future work undertaken for upgrades or adaptation within the conservation framework. Because adaptation is part of the district’s fabric integrity, feeling, and workmanship. More detailed information on the conditions can be found in the “Conditions Assessment Report” attached to this document.

Part IV Outlines a series of recommendations for maintenance, upgrades, and enhancements based on preservation treatments aligned to the Secretary of the Interior Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (“The Standards”) and the unique evolving character of the district. The recommendations set a basic framework for repair and maintenance of the features identified in poor condition during the survey; given the nature of the various constructions, each repair and upgrade work should be looked at specifically under considerations presented in this document. Additional strategies are presented for consideration for the maintenance of the site and structures.

Figure 3. Aerial view of Rubel Castle Historic District. Source Scott Rubel archives.

PROJECT TEAM

Glendora Historical Society Ad Hoc Contract Committee

Craig Woods

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Co-Chair

Kaitlin Drisko

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Co-Chair

Linda Granicy

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Co-Chair

Scott Rubel

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Sheharazad Fleming

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Sandy Krause

Castle Curator

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Hans Hermann

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Robert Deering

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Criswell Guldberg

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Robert Knight

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Member

Steven Flowers

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Ex Officio Member

Stephen Slakey

Ad Hoc Contract Committee Ex Officio Member

Page & Turnbull

417 S Hill St. Los Angeles, California, 90013 Ph. 213.221.1200

John Lesak

Historic Preservation Architect

Principal

James Mallery Architect Project Manager

Flora Chou

Architectural Historian

Jesús Barba Bonilla

Architectural Designer

Figure 4. Michael Rubel and typical work crew. Source Scott Rubel archives

Project and Historic Architect

PART II. HISTORIC BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

The Rubel Castle Historic District (RCHD) was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2013 with the following eleven contributing buildings and three contributing structures:

Tin Palace, also known as Citrus Packing House: The one-story building, formerly the citrus ranch packing house, is today adaptively reused as a museum and collections space. The building has an underground cellar and a refrigeration equipment pit on the west side referred to as “the well”.

The Tree House Residence: The two-story building has a residence on the second floor. The resource is attached to the steel-clad carport and shed that include a breezeway, known as the Shop, used as a historic artifact exhibition space, and an open garage used by residents. It is the only existing original residence from the citrus era. It is completed inside with its own kitchen and restroom with a shower.

The Glenn’s Shop: The one-story tin structure is used for historic artifact storage.

The Big Kitchen or Lemon House: The two-story building houses a communal kitchen along with collections on the upper level. The first level includes an assembly space referred as “the Dungeon.”

The Box Factory: The two-story, wood and tin building has an open garage and two utilitarian rooms at its base and a residence on its second floor; this is where the citrus crates were manufactured in the Albourne days. The Box Factory was the first building Michael rented to his first tenant, Glen Speer, architect of Mongoose Junction in St. John, USVI.

The Wood Rental, also known as the Chip House: The one-story utilitarian building has been adapted into a residence. The core of the Chip House is an older structure. It did have plumbing and a toilet in it, according to Scott Rubel. Some reservoir control valves are in a pit outside this house.

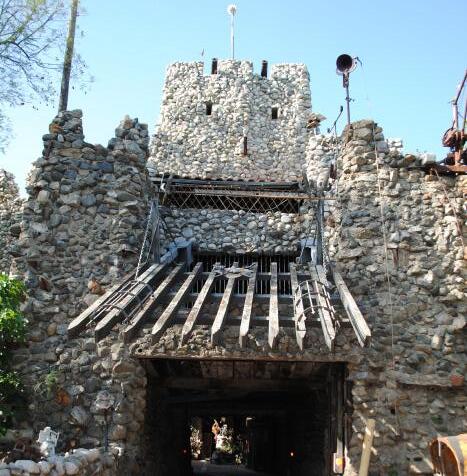

The Castle Complex: The stone masonry building was built on top of the old reservoir concrete walls. It has battlements, towers, a portcullis, and a central courtyard. Several buildings/structures are attached or built within the castle walls. For purposes of surveying the Castle Complex is subdivided in the following:

• The North Tower: The three-story structure is attached to the round perimeter wall and is used as a museum exhibition space.

• The Clock Tower: The cylindrical tower on the northeast side of the courtyard contains historic artifacts related to the clock.

• The East Tower: The two-story building is used as an assembly space called the Bennett Room and an art workshop on the second level that is accessed through the drawbridge from the Central Tower into the Clock Tower.

• The Pigeon Tower: The four-story tower with battlements houses a print shop at its base and residence at its upper levels. The tower has a pigeon coop on the rooftop.

• The King’s Quarters East: The three-story section east of the Fire Water Tower houses the Troll’s House residence at the base and the King’s Quarter’s residence in its upper levels.

• Fire Tower and Perimeter Walls: The central entry tower above the drive tunnel has an open shaft with a series of catwalks and mechanical engines to open the portcullis. The Central Courtyard is an open space with pavers and can be accessed by way of the portcullis tunnel and a tunnel between the Trolls House and the Pigeon Tower.

• The King’s Quarters West: The three-story section west of the Fire Water Tower includes a series of communal spaces used by Michael Rubel.

• The West Tower: Two open wood and steel decks connects Kings Quarter’s West and the Bee Tower. This is the main access staircase into the King’s Quarter’s residence.

• The Bee Tower: The four-story tower has a garage at its base and an elevated deck above. The upper floors of the tower are not currently used.

• The Bell Tower, also known as the Stair Tower: The cylindrical tower with a helicoidal staircase provides access to the upper levels of the north tower. It also provides access to the Wood Rental through the perimeter wall.

• The Central Tower, also known as the Round House, and the Machine Shop: The doubleheight round wood structure stands at the center of the Castle courtyard. The structure has a mezzanine and functions as an art workshop and museum collections space.

• The Bottle House: The one-story structure was built of glass bottles in the central courtyard. It stands under the Central Tower roof. It is used as a museum collections space.

Bennett’s Bunker: Also known as the rock shed or propane house, the one-story stone masonry structure near the Main Gate is used for storage.

The Rock Barn or Billing’s Barn: The two-story stone structure south of the Main Gate is rented out as storage.

The Pump House, also known as the Rock Garage or Bird Bath Engine: The one-story stone structure at the northeast corner of the site is used as a museum artifacts space.

Aside from the contributing resources, five (5) resources are identified in the National Park Service registration form as non-contributing:

• The Corral: The fenced piece of land at the southwest corner of the site.

• The Cemetery, also known as the Orchard: This citrus grove south of the site is decorated with some misspelled stones and homemade memorials to family and Castle Builders.

• The Santa Fe Caboose: This 1942s Santa Fe Rail Lines caboose built for the conductor’s living, is used as a guest house.

• The Water Tower: The wooden structure and water tank south of the Big Kitchen.

• The Windmill: The wooden structure adjacent to the Water Tank.

With the aim of providing a Preservation Plan for the RCHD, the Page & Turnbull team has identified six (6) additional resources not previously assessed:

• The Perimeter Walls: The Historic District’s entry and the masonry wall delimiting the site and the Main Gate.

• The Kiln Area (Laundry): The open workshop space north of the Main Gate. It includes a wooden shed over the community laundry.

• The Restroom: The single-use restroom between the Castle and the Tin Palace.

• The Shower Room: The recycled tank west of the Big Kitchen was formerly used as a shower room. It has a bathtub, sinks and shower.

• The Pool: The recycled tank south of the Windmill. Formerly used as the community swimming pool, it is abandoned today. It used to be attached to the Tree House by a wooden deck. The deck columns are still in place.

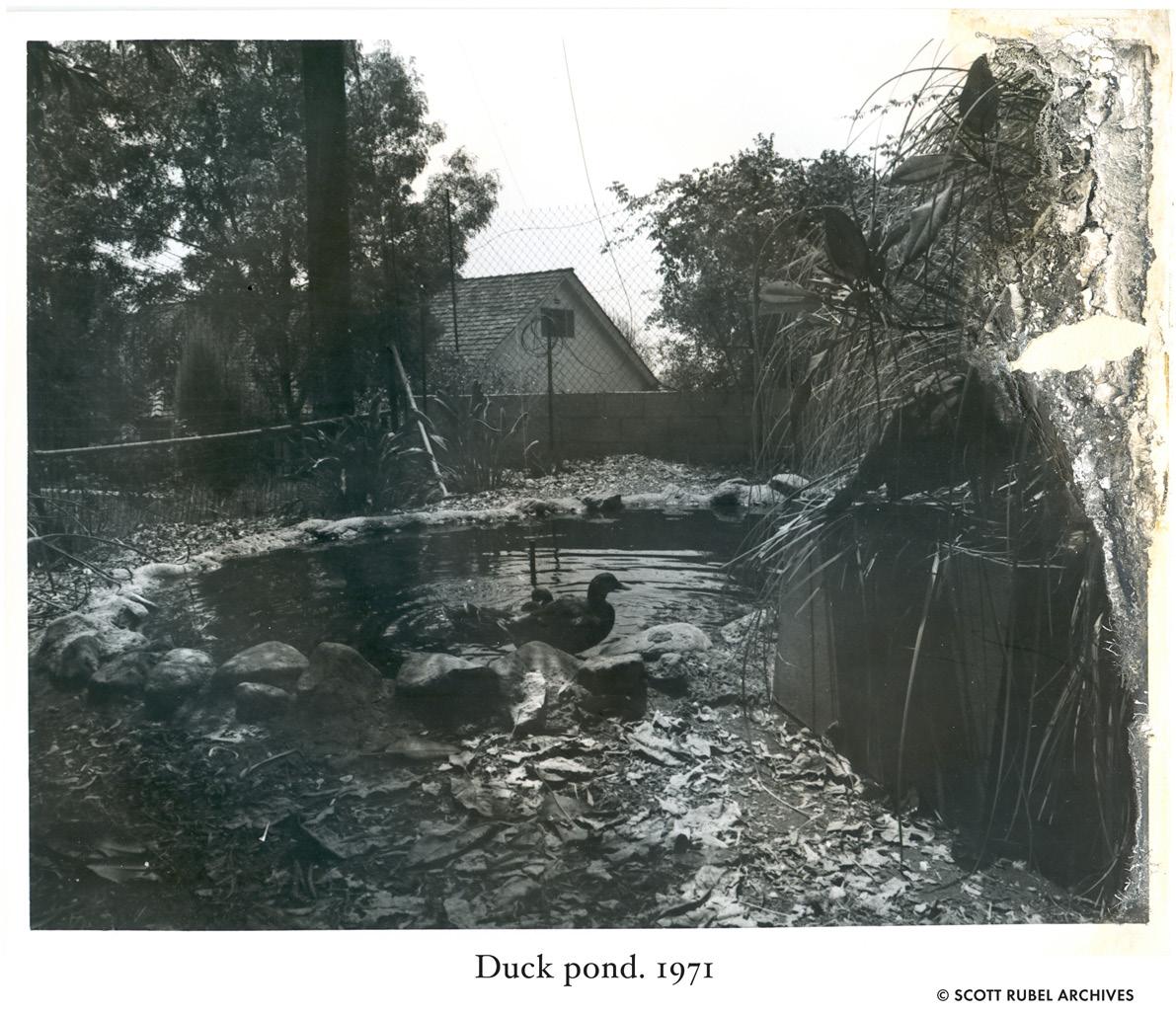

• The Duck Pond: The stone and concrete pond at the southeast corner of the site is abandoned today.

These features are included in the document as non-contributing resources due to their potential for future eligibility and their impact on the district’s fabric and feeling.

The Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan documents a total of twenty-three resources in the district. Each resource has been assigned an identifier number (1-23). To help communicate specific conditions and guidelines the Castle Complex has been subdivided into twelve resources from 1A to 1M. In the same manner, the Tree House has been subdivided into three resources from 11A through 11C. Resources 4 and 5 are considered landscape follies and no specific assessment was conducted for them.

Figure 5.

1986 Castle Completion Celebration. Source Glendora Historical Society archives

Landscape features within the district include: the overall layout of the site, specimen trees, fruit trees at the Cemetery, screening vegetation at the property boundary, and shrubs on the perimeter of the Castle Complex. The site plan of the RCHD has a vernacular, non-formal pattern. Resources cluster around an axial non-paved driveway that runs east-west from the Main Gate, under the Water Tower and through the breezeway at the Tree House building to the end of the site. Additional sinuous unpaved pathways interconnect the buildings and features in the site.

PERIODS OF SIGNIFICANCE

A self-contained folk-art village, the RCHD consists of a walled, 22,000 square foot Castle Complex and adjacent buildings that date to the early-twentieth century citrus farming that dominated the region. The Historic District has two distinct but interrelated “periods of significance” as stated in the National Park Service registration form (see appendix E). In the first period, 1910-1949, the district is historically significant due to its association with the local citrus industry and includes an irrigation reservoir on the property that dates to the period. The second period, 1959-1986, is historically significant due to the development of a unique and exceptional folk-art environment designed and built by idiosyncratic visionary Michael Clark Rubel. Rubel obtained the site previously known as the Albourne Citrus Ranch in 1959. Following acquisition, Rubel set out to construct a medieval-style castle from found and recycled materials. Major construction on the Castle Complex ended in 1986 with the completion of the Clock Tower.

Period of Significance 1910-1949: The period of significance from 1910 to 1949 reflects the property’s association with Glendora’s citrus industry. The concrete irrigation reservoir was built in 1910, and the citrus ranch ceased operations in 1949.

Period of Significance 1959-1986: The period of significance from 1959 to 1986 reflects the property’s association with Michael Rubel. Rubel acquired the property in 1959, and the Clock Tower, which was the last addition to Rubel Castle Complex, was completed in 1986. These resources are referred to as “Folk Art.”

BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

In total, the Historic District contains eleven contributing buildings and three contributing structures, for a total of 14 contributing resources. To facilitate the assessment of the Castle Complex's perimeter walls and battlements, Castle Complex resources have been subdivided into seven resources listed from 1A to 1M. In the same manner, the Carport and Shed building is subdivided into three resources and is listed from 11A to 11C.

According to the National Park Service registration, non-contributing resources include an orchard (the Cemetery), three structures, and one object. However, additional resources not previously assessed for significance are identified in this report and are considered part of the Folk-Art Environment theme due to their potential to become contributors to the Historic District in the future. Therefore, twentythree resources are identified in the Preservation Plan.

Resources are organized into three categories:

a) Citrus Farm Era

b) Folk-Art Environment

c) Non-Contributing Folk-Art

The Castle Complex sits on the northwest portion of the site while adaptively reused citrus farm buildings primarily sit on the eastern portion of the site. Contributing and Non-Contributing Folk-Art resources are scattered through the site.

Contributing Citrus Era rEsourCEs

Citrus Era resources are rare examples of utilitarian construction used during the Historic District's orange, lemon and avocado agricultural era. All Citrus Era resources were built prior to Michael Rubel’s acquisition of the property in 1959. With the exception of a couple of additions, the original building envelopes of this era are preserved while the interiors were adaptably reused by Rubel to house dwelling units for rent. These resources include:

3

– Tin Palace (Packing House)

5 – Big Kitchen

6 – Glenn’s Shop

9 – Box Factory

11A – Tree House Residence

11B – Garage

11C – Breezeway Shop

23 – Chip House

Contributing Folk-art EnvironmEnt rEsourCEs

Folk-Art Environment resources comprise buildings and structures built by Michel Rubel and Pharm Hands between 1959 and 1986. Built of ad-hoc, urbanite materials, their distinctive, medievalinfluenced style contrasts with the buildings and structures of the citrus era. Contributing Folk-Art Environment resources include the Castle Complex and the ancillary structures listed below:

1A – North Tower

1B – Clock Tower

1C – East Tower

1D – Pigeon Tower

1E – King’s Quarters East

1F – Fire Water Tower and Perimeter Walls

1G – King’s Quarters West

1H – West Tower

1J - Bee Tower

1K – Bell Tower

1L– Center Tower

1M – Bottle House

3 – Pump House

19 – Billing’s Barn

21 – Bennett’s Bunker

non-Contributing Folk-art

Non-contributing Folk-Art includes sites, structures, and objects that are not considered contributing to the RCHD include:

4 – Restroom

7 – Fire Pit

8 – Gas Pumps

10 – Duck Pond

12 – Shower Room

13 – Water Tower

14 – Windmill

15 – Pool

16 – Caboose

17 – Cemetery

18 – Corral

20 – Perimeter Walls

22 – Kiln Area

Figure 6. View of Box Factory

Figure 7. View of Clock Tower

Figure 8. Duck Pond 1971. Source Scott Rubell archives

RESOURCES

1A - North

1B

1C -

1D -

1E

1F -

1G -

1H

1J

1K

1L

1M

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11A

11B -

11C - Breezeway

12

13 -

14

15 -

16 -

17

18 -

19 -

20 -

21

22 -

23 -

CHRONOLOGY OF DEVELOPMENT AND USE

Below is an updated summary of development provided by the Glendora Historical Society (GHS). The chronology of development and use is an important part of the evolution of the Historic District and should continue to grow under the characteristic folk-art adaptations part of the narrative of the site and Michael Rubel’s vision. According to the GHS, the dates provided by Michael Rubel are imprecise (as he often changed dates or made them up) which has become part of the story of the district. Below, timeline dates are approximate and used as reference only.

1890 Estimated year that the reservoir was dug.

1905 The Glidden reservoir was built, according to the assessor’s records.

1910 A 124-foot diameter irrigation reservoir was completed for the citrus ranch.

1936 Today known as the “Tree House,” (11A-11C) a residence with a carport and shop was constructed for ranch personnel.

1937 The Glenn’s Shop (6) was built.

1938 The Tin Palace (2) or Citrus Packing House was completed.

1939 The Tin Palace (2) was extended on the south and north sides, and a partial basement was added beneath the building’s southern portion.

1940 A small office was added to the northern portion of the Tin Palace, which was originally used by Rubel as a kitchen. It was subsequently removed following damage from the 1969 flood.

1941 The Box Factory and tool shed (9) was constructed as a box-making factory, residence, and tool shed for the Albourne Ranch Co.

1943 A Platform and covered walkway was added along the southern side of the Tin Palace (2) to connect it to the Big Kitchen (5).

1943 The Big Kitchen (5) was constructed by the Albourne Ranch Co. as a Lemon Packing House and cold storage area. After Rubel acquired the property, it became the “Pharm” Kitchen and gathering place.

1949 The Albourne Citrus Ranch closed.

1950 Cold storage rooms added at west of original Citrus House (2).

Figure 9. Rubel Castle Historic Distric Resources Diagram

Pre-1953 The Chip House (23) or Wood Rental can be seen on a 1953 aerial photograph. (The exact date of original construction is unknown.)

1959 At age 19, Michael Rubel acquired the packing house and reservoir with the help of his mother, Mr. Bourne, and the Grace Episcopal Church. Rubel immediately took in renters who were encouraged to improve their living spaces.

1959 The Packing House (2) was converted into a residence. Cold storage rooms along the west elevation were converted into bedrooms. The large, open rectangular space of the building became dining, living and public rooms.

1961 Dorothy Rubel moved into the Packing House. Known for entertaining Hollywood celebrities and elaborate black tie events, the Packing House came to be known as “The Tin Palace.” (2)

1965 The Western 30 Horsepower pump engine was obtained from Glendora Mountain Road. Annual Easter parties began.

1965-1968 Construction began on Rubel Castle. A car-sized passageway was created by boring below grade through the circular reservoir walls.

1968 The Bottle house (1M) was built inside the reservoir and the drive tunnel was created. This marked the beginning of Castle construction.

1969 Massive floods hit Glendora and the foothill communities in January and February.

1969 Rubel ceded ten feet of the site for street widening along East Palm Drive and five feet on North Live Oak Avenue. Rubel agreed to remove a wood and tin residence on East Palm Drive north of the Citrus Packing House. The city of Glendora installed sidewalks and gutters. Glendora allowed Rubel to install a six-foot wall on East Palm Drive and North Live Oak Avenue. An entrance to the site was created along East Live Oak Avenue.

Early 1970s Construction focused on the southern portion of the Castle walls and buildings. By 1972, the Castle walls reached approximately three stories tall around the periphery

1970 The Windmill (14), found in Lompoc, is transported and rebuilt on site.

1972 The Central Tower also known as Round House or Machine Shop (1L) is constructed and becomes the centerpiece of the Castle Complex.

1975 The Billing’s Barn (19) was constructed south of the North Live Oak Avenue entrance to house horses by Pharm Hand Curt Billings.

1975-77 Tanks were lifted, stacked and assembled (bolted and welded) to create the Clock Tower (1B).

Figure 10. 1964 photo at the Tin Palace. Source GHS archives

Figure 11. 1969 Flood. View of garage that became the Chip House (Wood Rental) beyond. Source GHS archives

1978 Lorne Ward gifted the Seth Thomas Clock (from Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY).

1978 Michael Rubel and Curt Billings completed the Bee Tower (1J).

1979 Michael Rubel and Curt Billings completed the Garage and Elevator Tower at the West Tower (1H).

1980 Michael Rubel and Curt Billings completed the Pigeon Tower (1D).

1981 Curt Billings built the Loom Room and helped complete the Fire Tower (1F).

1981 The Bennett's Bunker (21) was constructed near the Live Oak Ave entrance to the property by long-time Pharm Hand Ed Bennett.

1982 Ed Bennett returns and resumes work on the Bell Tower (1K), north wall, circular stairway and roof over his shop the Bennett Room (1C). Ed completes construction of the Castle with the help of John McHann, and Scott Rubel.

1985 The Clock Tower’s (1B) river-rock exterior was constructed.

1986 According to a bronze plaque, the Castle was completed on April 16th.

1986 The 1890 Seth Thomas hand-wound clock was installed in the Clock Tower (1B).

1989 A caboose (16) was craned onto the Rubel Pharm. It was a gift from San Dimas friend John McCafferty. The caboose was originally built in 1942. The date painted on the side of the Caboose indicates that it was re-built in 1974.

2004 Michael Rubel suffered a heart attack. After the ambulance took him to the hospital he never returned to the site.

2005 Michael Rubel gifted the Rubel Castle to the GHS. The Castle Conservation Committee (CCC) was formed.

2007 On October 15th Michael Clark Rubel died in a home down the street from the Castle. The home belonged to his wife Kaia.

2009 The Tin Palace (2) was determined to be the best location for Michael Rubel’s personal and family archive and collection.

2013 The RCHD was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Figure 12. Concrete pumping under Chip House. Source Scott Rubel archives

Figure 13. Rubel Pharms driveway. Source Scott Rubel archives

CHARACTER-DEFINING FEATURES

Except for Citrus Era Buildings, resources in the RCHD are built of urbanite construction and mix recycled material, folkloric objects, and local stones. This type of construction can also be seen in adaptations to Citrus Era building interiors.

sitE and landsCapE

Site landscape includes mature trees, numerous recycled artifacts, and architectural follies

gEnEral propErty matErials

While different eras of significance display different materials, overall, the site’s Character-Defining Features include:

• Concrete

• River rocks

• Recycled bottles

• Wood

• Corrugated metal siding

• Composition shingles

• Concrete roofing red tile

• Recycled/found objects

• Decorative ceramic tiles

• Brick

Contributing Citrus Era CharaCtEr-dEFining FEaturEs

The Contributing Citrus Era resources have the following Character-Defining Features:

2 Tin Palace

• Exterior:

o Utilitarian design

o Wood-frame construction

o One-story height

o Generally rectangular plan

o Exterior walls clad in corrugated metal siding

o Capped with wood truss roof clad in corrugated metal panels

o Fenestration of wood-framed, multi-light, double-hung windows in a variety of configurations

o Stencil signage

• Interior

o Open layout/floor plan

o Refrigerator Rooms and wine cellar at basement

o Changes of flooring that illustrate that the building was previously three separate buildings that were connected (date unknown)

o Wood paneling along walls (including bathroom)

Excludes wood veneer paneling

Includes wood paneling dated dates to the Citrus Era.

Figure 14. Gas Pumps by Box Factory. Photo looking northeast

Figure 15. Windmill and Water Tower structures

11 Carport and Shed (Tree House, Garage, and Breezeway)

• Exterior

o Utilitarian design

o Two-story, wood frame construction

o Rectangular plan

o Enclosed garage at the ground story with sliding doors

o Full-length balcony supported by a recycled telephone pole used as a beam and post clad in irregular courses of river rocks, set in cement. The balcony has shed roof and wood railing that spans the second-story façade

o Low-pitched, side gable roof with red concrete tiles

o Fenestration varies but consists of metal- and wood-framed windows in a variety of configurations

o Exterior walls clad in cement plaster and corrugated metal siding

o Breezeway

o Open truss roof framing

o Historic era light fixture posts

o Stencil signage

• Interior

o Wooden built-ins

6 Glenn’s Shop

• Exterior

o One-story, rectangular plan

o Wood-frame construction with wood-beam roof

o Corrugated metal siding on exterior walls and doors

5 Big Kitchen (Pharm Kitchen, Lemon House)

• Exterior

o Two-story, wood frame construction

o Full length, open balcony, fronted by an iron-pipe railing, extending across the second story

o Low-pitched, front-gabled roof

o Exterior wall material includes panels of ribbed metal siding

o Fenestration varies and consists of single-panel, wood- and metal-framed windows and doors in a variety of configurations and sizes

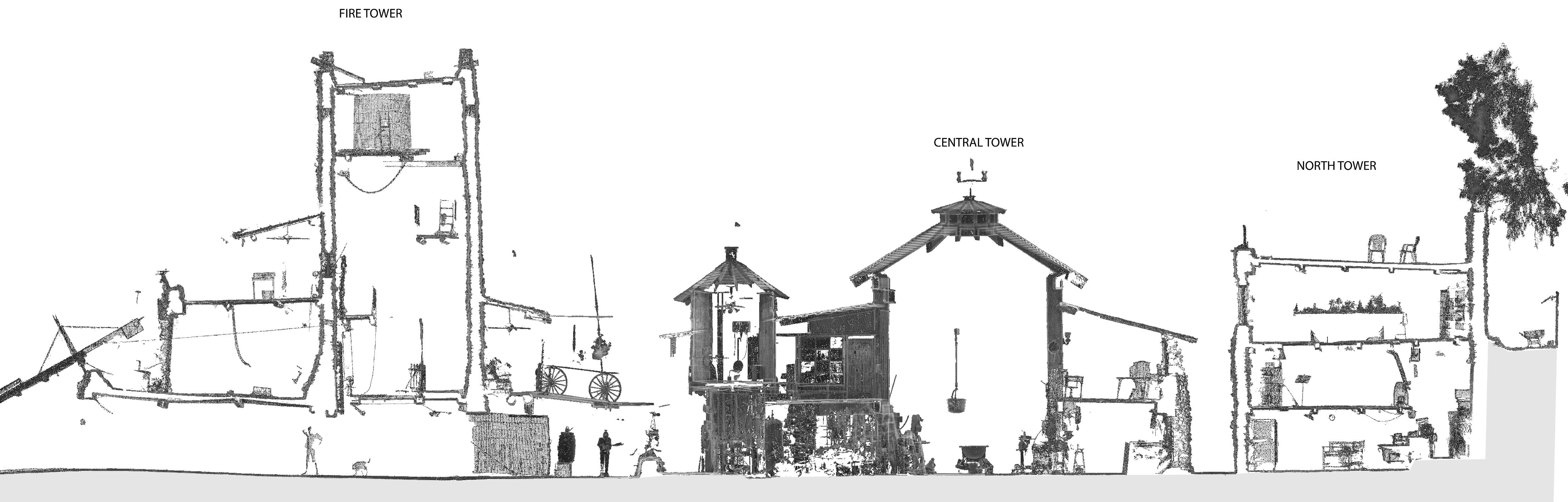

Figure 16. North-South Section. Source Laserscar point cloud. Credits Aqyer

• Interior

o Wood flooring

o Wooden built-ins

o Fireplace

o Historic era plumbing fixtures and furnaces

9 Box Factory

• Exterior:

o Vernacular design

o Rectangular, two-story wood-framed building

o Corrugated metal exterior walls

o Concrete foundation

o Low-pitched, side-gabled roof with exposed rafters and corrugated metal sheathing

o Exterior walls clad in corrugated metal

o Barn door on second floor, former hoist door

o Fenestration of wood-framed windows in a variety of sizes and configurations

o One-story tool shed located at the southern portion of the Box Factory

o Stencil signage

• Interior

o Wood flooring

o Wooden built-ins

o Historic-era plumbing fixtures and furnaces

23 Chip House

• Exterior

o One-story, wood frame construction

o Wood siding

o Side-gable roof

o Porch that spans the façade and consists of telephone poles used as post supports and a timber beam

• Interior

o Glazed tile flooring

o Wooden built-ins and slat walls

o Fireplace

o Historic-era plumbing fixtures and furnaces

Figure 17. Interior of Tin Palace

Figure 18. "NO SMOKING" stencil signs. typical around the district.

Contributing Folk-art EnvironmEnt

The Contributing Folk-Art environment resources have the following Character-Defining Features:

1 Castle Complex: Castle Walls, Buildings, Towers, and Entry Portcullis5

• Castle Complex Overall Character Defining Features

o Courtyard and walkway around the Castle faced with symmetrically arranged brick pavers accented by decorative glazed ceramic tile

o Stairs

Open stairs made of steel, repurposed tombstones, concrete, and wood

Second- and third-story residences, workshops, and rooms accessed by external staircases

Railings made from a variety of recycled materials including wood grilles, wagon wheels, and rail tracks

Stair treads of irregular-shaped slabs of recycled granite with steel-pipe railings

5 The Castle Complex is subdivided in sections from 1A to 1M for purposes of surveying and documentation.

o Decorative ironwork made at the Castle’s blacksmith shop

o Telephone poles as roof beams and opening transoms.

o 124-foot diameter concrete reservoir walls, which are exposed in some interior and exterior locations

o Walls

Irregular courses of boulder-sized river rocks with granite slabs (donated by a locat tombstone maker) that reinforce portions of the base

Walls reinforced with steel bars and other materials such as steel piping, railroad tracks, bed springs, large steel cables

Battlements that top Castle Walls

Recycled and found objects such as bottles, household items, appliances, and portions of bicycles and motorcycles embedded in mortar

Walls with wood lintels. handmade and recycled wood and steel casement windows, double-hung sash windows, and large iron grilles

Figure 19. Castle Complex North-South Section. Source Laserscan point coud. Credits Aqyer

1A North Tower

o Three-story height with a roof terrace

o Upper floors accessible via circular staircases via the Bell Tower

o Loom room at the ground floor, office at second floor with a mezzanine, train room at third floor and an open roof terrace with tile floor finish at the roof

1B Clock Tower

o Approximately 74-feet tall

o Structure of 10,000-gallon water tanks, stacked vertically, bolted together, and welded

o Tanks clad in river rocks and granite set in cement

o 1890 Seth Thomas hand-wound clock installed in Clock Tower on the ground floor

o Drawbridge connecting Clock Tower to Machine Shop and the studio in the East Tower

1C East Tower

o Two-story height

o Upper floor access via drawbridge on Clock Tower

o Quintessential windows with telephone poles

o Protruding piping

1D Pigeon Tower

o Four stories with open roof terrace

Print Shop at ground floor (Pot Shoppe)

Residences at floors 2-3

Pigeon coop at roof terrace

o Upper floors accessible via a brick and stone curved staircase

o Interior with wooden built-ins, ceramic glassed decorative tile, and wood and rope flooring

1E King’s Quarters East

o Stone walls

o Troll House residence at the base

o Urbanite windows and doors

o Metal signs

o Exposed wood beams

1F Fire Water Tower

o Entry Portcullis

Main entry tunnel on the south side of the Castle leading north into the Castle Complex courtyard

• Walls finished with multi-colored glass bottles set in cement

• Wood-plank ceiling with wood rafter supports

Portcullis (medieval-style gate) of recycled metal made by the castle blacksmith

• Members arranged vertically and bound with wrought-iron hardware

o Stepped Water Fire Tower

Three-story, river rock towers on the east and west sides of the tunnel and gate

Includes passageway/tunnel at the ground floor and the King’s Quarters above

Includes tank and pressurizing pump

Large terrace overlooking the grounds and surrounding neighborhood

Balcony or “hyphen” that extends between the two towers with massive timber posts that support a shed roof

Figure 20. Clocks on Clock Tower

1G King’s Quarters West

o Unfinished stone walls and some areas of applied horizontal wood siding in an irregular manner

o Wood & tile bar counter at the east end of the room

o Exposed beams at ceiling

o Painted wood door at entry landing with central glazing finished with wrought iron grill and tile

o Custom elevator

1H West Tower

o 3 level open decks

o Metal staircase and railing

o Hung artifacts

o Sloped roofing with red tile

1J Bee Tower

o Four stories with an open roof terrace

o Garage space at ground floor and storage space at the three upper levels

o Upper floors accessible via an L-shaped staircase made of repurposed tombstones at the north side

1K Bell Tower

o Three- and one-half stories height

o Spiral staircase leading up to an open walkway that connects to the castle’s North Tower terrace and train room

o Catwalk connecting to north side of Castle wall

o River rock and reinforced granite walls

o Arched opening at the top of the tower that contains one of the clock bells that came with the Seth Thomas clock

1L Central Tower

o Location as the centerpiece of the Castle Complex

o Circular plan with a double-height open center

o Two-story, timber framing

o Irregular design composition with different appearances from all angles

o Walls with irregular courses of granite and boulder-sized river rocks set in cement

o Recycled bottles, curios, and other found objects embedded in the walls

o Series of large iron grilles and gates, reclaimed jail bars, placed irregularly along the ground story, which provide light and access to the interior

o Roof of radial wood joists supporting a grid of wood-plank sheathing covered in plywood

o Two cupolas at the roof, once centered and a smaller one off-center

Larger cupola with clerestory windows

The smaller cupola roofs the restroom in the upper level

o Varying eave treatments, including wide open eaves at the southwestern side extending to shelter the one-story Bottle House and shallower, open eaves ringing the circumference of the building

o Varying fenestration patterns including homemade and recycled fixed and casement windows in wood and metal

o Windows and doors with lintels made of timber and slabs of granite

o Open floor plan with shop occupying the first story and loft area and workspaces on second story

o Second story balcony and walkway at south side near entry tunnel that connects the loft of the Central Tower with the castle buildings

o Drawbridge at the northern portion of the building that connects with the Clock Tower.

o Custom bathroom on second level

Figure 21. Figure - Courtyard at Castle Complex.

1M Bottle House

o One-story residential dwelling

o Constructed out of multi-colored bottles set in cement

o Rectangular plan

o Front gabled roof

o Corrugated metal sheathing

o Transparent multi-colored bottles that allow light into interior

o Low height mezzanine level accessible by ladder at interior

3 Pump House (Bird Bath Engine)

o One-story structure

o Rectangular in plan

o Front-gable roof sheathed in corrugated metal

o Recycled wood doors, with wood frames and a lintel, that provide access to the ground story

o Gable apex pierced with a round opening filled with a recycled wagon wheel, providing ventilation to the interior

o Pump Engine

o Palm Trees for building construction

o Structural river-rock exterior walls in irregular courses, set in cement

19 Billing’s Barn

o Two-story construction

o A rectangular plan capped with a front-gable roof sheathed in clay tiles

o Three purlins, made from recycled telephone poles, that mark the gable apex and sides

o Open eaves, revealing the structure of wood planks and recycled wood rafters beneath

o Roof eaves on the south side that extend to enclose a storage area

o Handmade, double wood doors that provide access to the ground story

o Wood casement windows with wood frames at the second story

o Exterior walls built of structural river-rock arranged in irregular courses, set in cement

o Hoist and platforms

21 Bennett’s Bunker

o One-room structure

o Rectangular in plan

o Capped with a side-gabled roof sheathed in concrete tiles

o Roof gables and rafters bear on massive wood logs and beams

o Building displays load-bearing river-rock walls set in cement, with timber lintels over a handmade wood door made of recycled materials

o A series of small, rectangular window openings framed by flat, asymmetrical chunks of granite

o Pulley, hoist, and hardware

non-Contributing Folk-art EnvironmEnt The Non-Contributing Folk-Art Environment

Figure 22. Tank Room getting set. Courtesy of Scott Rubel

SIGNIFICANCE

To determine Preservation Plan work priorities, this Preservation Plan identifies five levels of significance within the RCHD: Primary Significant, Secondary Significant, Contributing, Non-contributing Folk-Art, and Non-Contributing. Each level is applied to features and spaces to clarify their significance and prioritize their preservation.

Primary Significant

Primary Significant features convey the seven aspects of integrity defined by the National Register. Due to their importance, they should be the focus of preservation efforts. Within the concept of integrity, the National Register criteria recognize seven aspects or qualities that, in various combinations, define integrity. These seven aspects include location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association. Primary Significant features include features identified as Character-Defining Features in Historic District’s Contributing resources that have remained in their original states, such as exterior walls, original windows and doors, and public spaces which, due to their location, association, and feeling within the district represent the overall legacy of Michael Rubel and Rubel Castle.

Secondary Significant

Secondary Significant features also convey the seven aspects of integrity. Secondary Significant features such as exterior walls, original windows and doors, and public spaces remain in their original states. However, due to such factors as change in fabric over time, location within the district, and current condition they are considered secondary. They represent the progressive evolution of Rubel Castle.

Contributing

Contributing features are resources that convey some, but not all aspects of integrity. Contributing features include spaces that are partially accessible to the public, have suffered significant modifications throughout the years, and/or currently act as utilitarian spaces and are in plain sight.

Non-contributing Folk-Art

Non-contributing Folk-Art features include sites, objects, follies, and resources within the district’s boundaries that are not contributing to the RCHD per the National Park Service registration form. Although not significant at the National Register level, these features have the potential to become eligible in the future because of their association with the Twentieth Century Folk Art Environments in California theme. They contribute to the district’s fabric and feeling.

Non-contributing

Non-contributing features are elements within the Historic District’s boundary that do not pose any significant value.

signiFiCanCE diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate and identify the significance of features within the RCHD.

Figure 23. View of the original Rubel Duck Pond. Courtesy of Scott Rubel

1A

1E

1F

1G

1J

Figure 24. Significance Diagram

Figure 25. Significance Diagram

CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND PRESERVATION PLAN

BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES

1A - North Tower

1B Clock Tower

1C - East Tower

1D - Pigeon Tower

1E King's Quarters East

1F - Fire Water Tower and perimeter walls

1G - King's Quarters West

1H - West Tower

1J Bee Tower

1K Bell Tower

1L - Center Tower

1M - Bottle House

2 - Tin Palace

3 - Bird Bath Engine

4 - Restroom

5 - Big Kitchen

6 - Glenn's Shop

7 - Fire Pit

8 - Gas Pumps

9 - Box Factory

10 - Duck Pond

11A - Tree House

11B - Garage

11C - Breezeway

12 - Shower Room

13 - Water Tower

14 - Windmill

15 - Pool

16 -

17 -

18 -

19 -

20 -

21 -

22 -

23 -

Figure 26. Significance Diagram Third Level

Figure 27. Significance Diagram Fourth Level

This Page Intentionally Blank

CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND PRESERVATION PLAN

PART III. EXISTING CONDITIONS

CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND THE FOLK ART ENVIRONMENT

Evaluating the conditions of a folk-art environment is similar, but not identical to a building conditions assessment. The characteristics of a folk-art environment are reviwed here as a prelude to the summary of existing conditions. Folk-art environment characteristics present at Rubelia are:

• The monumental size of the work, consisting of buildings, structures, sculptural forms, and decorative surfaces – including the living space of the artist (Michael), as well as living spaces for many of his collaborators/craftspeople.

• Visitors find themselves surrounded on all sides (above and below) by the vision of the artist.

• The artist used the natural and built landscape, as well as discarded materials to create the folk-art environment.

• Recycling and innovative use of natural and man-made materials are endemic to the work. These works combine beauty with utility and transform common objects into art – bringing pleasure to those who view them.

• The artist(s) spent the bulk of their time (spare time) on their creation. Ingenuity and creative drive, rather than money and new materials, were important elements of the work.

• The visionaries are not highly skilled artisans, builders, or craftspeople – they do not earn their living making art or building buildings. They possess a vigorous unschooled spirit and create powerful individual statements amid routine commercial culture. Nonetheless, the visionaries grow to become “schooled” citizens.6

• The design of the folk-art environment was the result of a highly intuitive process of creation rather than products of a particular plan or set of rules.7

SUMMARY OF EXISTING CONDITIONS

Existing Conditions mEthodology

The following assessment identifies many of the current conditions of the Rubel Castle Historic District (RCHD), site, and resources. Such conditions were observed during on-site investigations in Spring 2022. The team assessed conditions of the Citrus Era, the Folk-Art Environment, and resources identified as Non-Contributing Folk-Art. The purpose of the investigation was to document and assess the condition of the existing site and structures, identify areas of immediate concern, and make general recommendations for the overall treatment. This conditions assessment will serve as a tool for planning future maintenance and preservation.

Architectural investigations were conducted on site on May 12th and 13th of 2022. Conditions were assessed with basic, visual tools such as tape measures, cameras, and non-invasive metal probes. Documentation took the form of written notes and digital photography synchronously uploaded to a cloud-based software (LAYER APP). Information was then rectified and processed in the office.

The Existing Conditions section of this Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan is divided into two sections: 1) Historic District Site and Landscape and 2) Buildings and Structures. Historic District Site and Landscape includes an assessment of softscape and hardscape elements as well as site drainage issues. Buildings and Structures includes a brief assessment overview of resources.

Page & Turnbull assessed resources regardless of significance to identify possible safety hazards. P&T utilized a rating system according to the Conservation Assessment Program (CAP) Handbook for Assessors Historic Structure Guidelines.8 Each site and building element condition is described and given an assessment rating of “Good,” “Fair,” or “Poor.” To set a benchmark for preservation work, the Glendora Historical Society (GHS) agreed that a “Fair” rating is acceptable. Preservation efforts should thrive to bring resources rated as “Poor” to a minimum of “Fair” through upgrades.

6 Glen Speer became a renowned architect and built Mongoose Junction. Curt Billings became a city engineer for Rancho Cucamonga and many others went on to become handymen and contractors.

7 “Twentieth Century Folk Art Environments in California,” National Register of Historic Places Thematic Nomination, 1978 and Addendum, 1979.

8 Heritage Preservation (the National Institute for Conservation). 2009. Conservation Assessment Program (CAP) - Handbook for Assessors.

Condition dEFinitions

Page & Turnbull uses the following National Park Service definitions to evaluate conditions at the RCHD:9

GOOD (G)

The structure and significant features are intact, structurally sound, and performing their intended purpose. The structure and significant features need no repair or rehabilitation, but only routine or preventative maintenance and monitoring.

FAIR (F)

The element is in fair condition if either of the following conditions is present:

• There are early signs of wear, failure, or deterioration through the structure and its features are generally structurally sound and performing their intended purpose; or

• There is failure of a significant feature of the element.

POOR (P)

The element is in poor condition if any of the following conditions is present:

• The significant features are no longer performing their intended purpose; or

• Significant features are missing; or

• Deterioration or damage affects more than 25% of the feature; or

• The structure or significant features show signs of imminent failure or breakdown.

A rating for each building is provided here. Because not all building elements or features were assessed, ratings are observed averages. P&T recommends that the maintenance staff assess each building in greater detail to develop a resource-specific monitoring and maintenance plan.

The work for accessibility compliance, structural, mechanical, plumbing, electrical, building envelope, and life safety egress is estimated in the following categories:

Heavy

Most of the construction and infrastructure need retrofitting.

Medium

Some of the construction and infrastructure need retrofitting or upgrades.

Light

Minimal work or solely maintenance and monitoring is required.

Conditions summary diagram

The following diagram illustrates and identifies the estimated average of resources throughout the RCHD. Specific features and locations are indicated in red to identify them as safety concerns because their current state poses a threat to residents and visitors.

9 U.S. Department of Interior. 1997. Preserving Historic Structures in the National Park System: A Report to the President. National Park Service recommendations, National Center for Cultural Resources Stewardship and PArtnership Programs, NAtional Park Service, Washington: Park Historic Structures and Cultural Landscapes Program, 111. Accessed September 30, 2022. http://npshistory.com/publications/habs-haer-hals/ preserving-historic-structures.pdf.

saFEty ConCErns

Safety concerns should take priority in preservation work. The following are some items and reasons of concern observed during the survey:

Stairs and elevated walkways: The majority of the stairs and walkways in the Castle Complex represent a safety concern due to open threads, lack of handrails, open or lack of guardrails, and uneven steps. Particularly the helicoidal staircase at the Bell Tower presents signs of rotten and dry wood. The Drawbridge in the Clock Tower has no guardrails and the catwalk connecting the King’s Quarters to the Center Tower is currently closed and in disrepair. The staircase inside the Pigeon Tower has some loose steps. Because most of these are the only access to the different spaces of the Castle and residences, it is important to make sure these are stable in case of an emergency.

Foundations/retaining walls: The reservoir retaining wall presents cracks and signs of moisture infiltration. Potential undelaying conditions could cause failure and irreparable damage to the Castle. The retaining wall on the east side of the Tin Palace leans inwards because of the tree rooting pressure. The movement seems stable, but shoring should be considered. The west side of the Tin Palace is likely under stress and water damage. The Shower Room’s wooden foundation is heavily damaged.

Structural elements: Most structural elements in the district are wood and significant rotten damage and termite infestation are evident. Failure of elements like wood beams, the balcony at the Billing’s Barn, the Windmill, and the Water Tower represents a safety concern for residents and visitors of the district.

Additional elements of concern: The loose concrete tiles, sticking rusted elements, and pointy wood rafters in Bennett’s Bunker can harm people passing by due to their low heigh; the water collected in the Pool creates the perfect environment for disease-transmitting insects.

sitE and landsCapE

The site plan of the RCHD has a vernacular, non-formal pattern. Resources cluster along an axial, non-paved driveway that runs east-west from the Main Gate, near the Water Tower, and through the breezeway at the Tree House building. Additional sinuous, unpaved pathways interconnect other buildings and features.

Shrubs and mature trees adorn the Historic District. Architectural follies are scattered throughout the site. Most trees on the site are mature, and some are structurally damaging built resources. This is the case of the Tin Palace, whose east retaining wall foundation is being uplifted by mature fig roots. Also, the slab at the Breezeway is being uplifted by a tree at its southeast end. Moreover, trees around the Historic District cast mature branches over building roofs that pose potential damage in case of failure.

sitE drainagE

The RCHD sits in a former orange grove farm built adjacent to a water reservoir; commonly these reservoirs are built in depressed terrain where rainwater flows naturally. The reservoir was converted into the Castle Complex water runoff, which is a primary challenge. A series of scuppers around the castle direct water from the north into the courtyard, and exposed drain lines with glazed pavers direct the flow outside the Castle. Both the scuppers and drain lines are part of the Character-Defining Features of the Castle Complex. The loose backfill against the concrete walls of the reservoir does not have the appropriate drainage to mitigate hydrostatic pressure and signs of moisture can be seen around the Castle’s walls.

The terrain slopes from north to south. While the city of Glendora’s public infrastructure (roads and drainage) may help decrease the stormwater flow into the district, the site still does not have sufficient infrastructure to prevent damage to the historic resources. A main storm drain line runs through the site north to south on the east side between the citrus era resources.

landsCapE FEaturEs: soFtsCapE

Drought-resistant shrubs and mature trees compose the landscaping fabric of the Historic District. They line the sinuous pathways adorning the site and provide its picturesque look. Mounds front the exterior of the castle walls covered in mulch and fruit trees. Similar mulch and fruit trees can be found at the south portion of the site in the gardens and the Orchard (Cemetery). The softscape throughout the site is in fair condition.

landsCapE FEaturEs: hardsCapE

Most pathways in the Historic District are unpaved. Brick pavers adorn the Castle Complex courtyard with glazed tile accenting the original drainage lines. Historic objects retrieved from various locations are scattered throughout the site and are part of the RCHD museum collections. Most are in poor to fair condition, in need of maintenance, and not accessible. The main driveway runs below the Water Tower, which is in poor condition and at risk of failure, posing a safety concern in case of emergency because it is the only vehicle access to the east part of the site.

RESOURCES CONDITIONS SUMMARY

The following section presents an overall summary of the existing conditions of landscape, building, and structure resources. More detailed information can be found in the Conditions Assessment Report included as an appendix of this document.

CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND PRESERVATION PLAN

FINAL DRAFT

landsCapE rEsourCEs

The following is a list of the resources and their overall condition. More information can be found in the Conditions Assessment Report appended to this document.

10 - DUCK POND - POOR condition.

17 - CEMETERY - FAIR condition.

18 - CORRAL - FAIR condition.

22 - KILN AREA - FAIR condition.

buildings and struCturEs

1C - EAST TOWER - POOR condition.

1A - NORTH TOWER - FAIR condition.

1B - CLOCK TOWER - FAIR condition.

1D - PIGEON TOWER - FAIR condition.

1E - KING'S QUARTERS EAST - FAIR condition.

CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT AND PRESERVATION PLAN

1G - KING'S QUARTER'S WEST - FAIR condition.

1H - WEST TOWER - FAIR condition.

1J - BEE TOWER - FAIR condition.

1K - BELL TOWER - FAIR condition.

2 - TIN PALACE - FAIR condition

3 - PUMP HOUSE - FAIR condition.

4 - RESTROOM - FAIR condition.

5 - BIG KITCHEN - GOOD condition.

6 - GLENN'S SHOP - FAIR condition.

9 - BOX FACTORY - FAIR condition.

11A - TREE HOUSE - FAIR condition.

11B - GARAGE - FAIR condition.

11C - BREEZEWAY - FAIR condition.

12 - SHOWER ROOM - POOR condition.

13 - WATER TOWER - POOR condition.

14 - WINDMILL - POOR condition.

15 - POOL - POOR condition.

16 - CABOOSE - FAIR condition.

19 - BILLING'S BARN - POOR condition.

20 - PERIMETER WALLS - FAIR condition.

21 - BENNETT'S BUNKER - POOR condition.

23 - CHIP HOUSE - FAIR condition.

PART IV. TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS & GUIDELINES

Part IV, Treatment Recommendations & Guidelines uses the historical information and documented conditions presented in Parts II and III, as well as working meetings with the Glendora Historical Society Ad Hoc Committee, to formulate historic preservation objectives and tailor a range of treatment approaches for the on-going and future treatment of the variety of buildings, structures, objects, as well as site and landscape features that contribute (and do not contribute) to the historic district. As discussed in detail below, “Preservation Zoning” is applied to the Rubel Castle Historic District (RCHD) to relate the treatment recommendations and guidelines to the Secretary of the Interior Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (“The Standards”).

Crafting historic preservation treatment recommendations and guidelines for the RCHD is challenging for a variety of reasons, including (but not limited to):

• The complexity of the district ranging from type of construction, era built, wide variety of materials used, organic quality of the building forms (particularly within the Castle Complex), etc.

• The size of the historic resource.

• The folk-art environment characteristics of the district. Because Michael and his team of “Pharm Hands” were not professional builders and they often developed construction methods as they went, the as-built construction is not comparable to building norms, standards, and/or codes.

• Similarly, the incorporation of “found”/recycled materials throughout the district and the need to accommodate the differing physical and mechanical properties of the materials – a stone is going to behave (age) differently than a piece of wood or a bottle or a vacuum cleaner head or a bicycle.

The treatment recommendations and guidelines below provide general advice regarding materials, features, systems, structures, buildings, and landscaping that make up the historic district. Additionally, they offer a process for managing and executing parts of the Preservation Plan. Accompanying Part IV is a “Treatment Matrix” that more specifically locates, classifies, and prioritizes treatment recommendations. The Treatment Matrix also offers timelines and suggests responsible parties for the treatment recommendations undertaking, either by the Castle Conservation Committee or, if subcontracting is preferable, by the Historic Preservation Committee (Ad Hoc Contracts Committee). While the Treatment Matrix is included as a printed appendix, it is also provided in digital format so that the information can be reorganized/sorted in a variety of ways. It should be considered a “living document” that is periodically updated as work is completed and conditions change.

HOW TO USE THE PRESERVATION PLAN

The Conditions Assessment and Preservation Plan provides the GHS and the Rubel Castle community with a framework to conserve and maintain the RCHD. This plan should be used as a starting point for developing strategies, programs, and schedules to conserve the livelihood and historic character of the district.

The plan provides a series of high-level standard recommendations for the treatment of the most common conditions observed around the castle. Materials and construction methodology vary at each condition and treatment should be selected based on the case-by-case specific need.

Creating two committees to oversee and perform the preservation work in the RCHD can help organize the different treatments needed around the site depending on the level of proficiency required by the work:

• Historic Preservation Committee: This committee will oversee the whole implementation of the preservation plan and will decide on work that requires large city processing permits, specialized workmanship, and any work that requires a contract.

• Castle Conservation Committee: This committee mostly composed of volunteers will undertake maintenance tasks around the castle, documentation, and routine repairs needed around the historic district.

It is also recommended to form a joint committee with members of both the CCC and HPC to manage, schedule, and oversee the application and progress of the preservation plan. This committee will decide on key components in the process cycle with the objective to provide the least aggressive treatment.

Refer to the Treatment Matrix (Appendix A) and figure 33 for additional recommendation on which committee should perform the task.

Figure 29. Rubel Castle Committee Diagram

PROCESS CYCLE

daTa collecTion and documenTaTion

The first step is to develop a maintenance and monitoring plan that prevents additional deterioration of the resources and features. Due to the nature of the construction and the lack of documentation, it is difficult to understand and predict where systems and structures may fail. The diagnosis should evolve over time through data collection and documentation.

A maintenance and monitoring plan should be developed in accordance with the Historic Districts’ requirements. All resources, spaces, and landscaping within the district’s boundary should be periodically inspected, cleaned, maintained, and repaired as required.

Recommended TReaTmenT

The RCHD’s overall condition is fair, as some key materials (wood) and assemblies have deteriorated, some atypical (folk-art) construction methods/materials are not performing adequately, and maintenance and monitoring efforts are not always coordinated, systematic, and/or applied with regularity. Recommendations in this document strive to bring conditions deemed as “poor” into a better state and to prevent the further deterioration of elements in fair condition.

The required maintenance, documentation, repair, and additional work can be performed either by a crew of volunteers (Castle Conservation Committee) or by contracting professional services depending on the scope and requirements of each specific intervention through the Historic Preservation Committee. The Castle Conservation Committee can take care of regular maintenance items, documentation, and minor repair required around the district, while works that require professional input, plan-check permitting, and heavy labor should be undertaken by professionals in the field required. This may include works such as structural assessment and retrofit, extermination services, rainwater site drainage, etc.

Describe WHY the assessment is necessary. HOW would the condition be classified - Maintenance, Repair, Monitoring, Systems Upgrade, or Resiliency?

Ascertain information about the material / assembly to be assessed and what types of deterioration may exist. Assemble information regarding relevant data to collected and types of assessments that may be relevant. Note that research may be ongoing throughout an entire assessment.

Decide WHAT type(s) of are needed. There are different types of condition assessments. The most common is a visual assessment - others include monitoring / measuring change over time, field testing, and materials sampling followed by laboratory testing. Assessment can also include trial treatments / mockups to determine their efficacy.

Establish WHERE and HOW MUCH assessment is needed. Often a representative sample may need assessment to provide sufficient data to more forward with treatment recommendations.

Determine HOW is the assessment being completed. Is special equipment required? Will ladders or lifts be required to access the feature being assessed? Is information being recorded via pencil and paper -or-digital methods? Do forms or background drawings need to be prepared to record data? What nomenclature is being used? How is each feature uniquely identified? How are the results being presented to others and entered into the record.

Identify WHO should participate in the assessment. Is professional or expert assistance needed? Is training required for tools being used to field test? Are volunteers being used - if so, who coordinates the volunteers? Prepare a directory with contact information of the assessment team.

Determine WHEN the assessment is to occur. Is access to private spaces required? What other site activities (tours) or conditions (weather) could affect the schedule? Consider building in time contingencies.

As needed, determine HOW MUCH the assessment would cost. Include any professional time, equipment purchase or rental, shipping and handling of samples, and/or laboratory fees.

Prepare a written proposal including the information above for Approval. If an assessment proposal is large, complicated, expensive, or controversial, consider starting with a brief conceptual proposal.

Figure 30. Process cycle diagram

A2.1

A2.2

A2.3

A2.4

Present the proposal for the assessment to the board or committee for approval. Include all the steps from the planning and preparation phase in the proposal.

Answer any questions relating to the proposed assessment. Set relaistic expectations and scope.

Any changes requested from the board or committee should be addressed in a timely manner. Schedule ongoing working meetings to come to an agreement in a proper time frame.

Receive authorization, funding, etc. to proceed. Set a start deadline.

A3.1

A3.2

A3.3

A3.4

A3.5 PROGRESS CHECK-INS

A4.1

A4.2

A4.3

Mobilize. Gather equipment, team, etc. Update and review schedule.

Hold a kickoff meeting with team and stakeholders, could be on first day of assessment.

Assess conditions, document any unforseen circumstances.

Based on initial results, revise scope, methodology, team, and/or schedule as needed.

For longer efforts, periodically check-in with stakeholders and joint committee

Prepare assessment report, include 1) a summary of observations and data, 2) an analysis, and 3) recommendations for additional assessment and options for treatment. List next steps. Include field information as an appendix.

Answer any questions from the assessment the board or committee may have

Prepare the final assessment report documenting all the data from the observations and proposing possible treatments. File and archive copies of report and appendices in print and digital formats. Distribute copies of report to all interested parties. Ensure information is available to future generations.

T1. PLANNING & DESIGN

WHAT do we need to know?. Gather and prepare all the documentation relevant to the condition to be treated. This may include but is not limited to: As-builts, assessment reports, historic records, construction drawings, specifications, or any other form of documentation that may inform the treatment process.

HOW MUCH is needed and HOW MUCH do we have? Allocate the budget and obtain pricing for the treatment work required. Depending on the size and requirements of the work estimate the cost of the treatment. For larger projects prepare a request for proposal (RFP) and consider a bidding process if time allows for it. For smaller projects request quotations from the required professional and consider allowances for volunteers.

Create a schedule that is inclusive of all work required to perform the treatment necessary. HOW LONG will the entire process take? Is there down time required for repairs to cure or set? Is the work scheduled after visitor hours or does it need to be coordinated during public visiting hours? consider weather factors.

Present the proposal for the treatment to the board or committee for approval. Include all the steps from the planning and preparation phase in the proposal. Review bids and proposals and quotations with the help of historic preservation professionals and select the most appropriate.

Answer any questions relating to the proposed treatment. Set relaistic expectations and scope.

Any changes requested from the board or committee should be addressed in a timely manner. Schedule ongoing working meetings to come to an agreement in a proper time frame.

Receive authorization, funding, etc. to proceed. Set a start deadline.

Build a team to oversee the project. Bring consultants, staff, and stackholders whose involvement is critical in the treatement process of the upcoming work. DIVIDE AND CONQUER, assiegn one or two members from the committees to follow the process. For example WHO is the best fit to help repair the wooden steps?

Hold a kickoff meeting with team and stakeholders, could be on first day of treatment.

T3.3

Commence the work, schedule regular team check-in meetings. document and brainstorm solutions for any unforseen circumstances.

Document all phases of treatment work. Before, during, and after the treatment work, document the conditions with photographs, drawings, video recordings, etc. that adequately capture the process. File and archive copies of all materials in print and digital formats. Ensure information is available to future generations.

Prepare a final treatment report include all the documentation gathered during the work and include any conditions discovered after demolition that may be useful to furture monitoring or maintenance efforts. Report any variations from the construction documents or specifications that may be needed for reference in the future for additional work or maintenance. File and archive copies of report and appendices in print and digital formats. Distribute copies of the report to all interested parties. Ensure information is available to future generations.

Figure 31. Example of monitoring progam at the Desert View Watch Tower, Grand Canyon National Park.

1. Plan showing location of existing cracks

2. Proposed location of exterior crack monitor

3. Installed interior crack monitor 4. Monitor data log

Results of moniotring

CLASSIFICATION OF TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

There are six (6) interrelated areas to consider when planning to protect the historic character of the RCHD both now and in the future: maintenance, repair, monitoring, systems upgrades, resilience, and enhanced use. The areas of concentration provided by the Ad Hoc Contract Committee fall into one or more of these focus areas.

MAINTENANCE

For the purposes of this report, MAINTENANCE is defined as proactive measures to upkeep materials, features, and systems of the RHCD so they can continue to perform their required function(s). Other terms used to describe this are preventative maintenance, planned maintenance, cyclic maintenance, or scheduled maintenance.

It is our understanding that the Ad Hoc Committee members who operate and maintain the district would like to apply a folk-art environmentalist mindset to the maintenance of the site - selfperforming work and applying ingenuity and creative drive to solve maintenance problems. In crafting recommended treatment and guidelines, the team should try to balance this mindset with traditional historic preservation best practices.

REPAIR