Recorder

I lift up my eyes to the hills. From whence does my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth (Psalm 121:1-2, RSV).

I lift up my eyes to the hills. From whence does my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth (Psalm 121:1-2, RSV).

Love cannot live without action, and every act increases, strengthens, and extends it. Love will gain the victory when argument and authority are powerless. Love works not for profit nor reward; yet God has ordained that great gain shall be the certain result of every labor of love. It is diffusive in its nature and quiet in its operation, yet strong and mighty in its purpose to overcome great evils. It is melting and transforming in its influence.… Pure love is simple in its operations, and is distinct from any other principle of action.

—Ellen White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 2, pp. 135-136

4 Finding Your Path 9 Some Historical Highlights 13 A Vital Communication Hub

James and Ellen White 23 P. G. Rodgers 29 William Ward Simpson 23 Arizona: The Early Years

37 Touching Hearts in Hawaii for Jesus 30 Beginnings: Central California

45 Beginnings: Nevada

49 Beginnings: Northern California

53 Beginnings: Utah

57 Beginnings: Southeastern California

63 Beginnings: Southern California

69 Asian-Pacific Work

73 Black Ministries

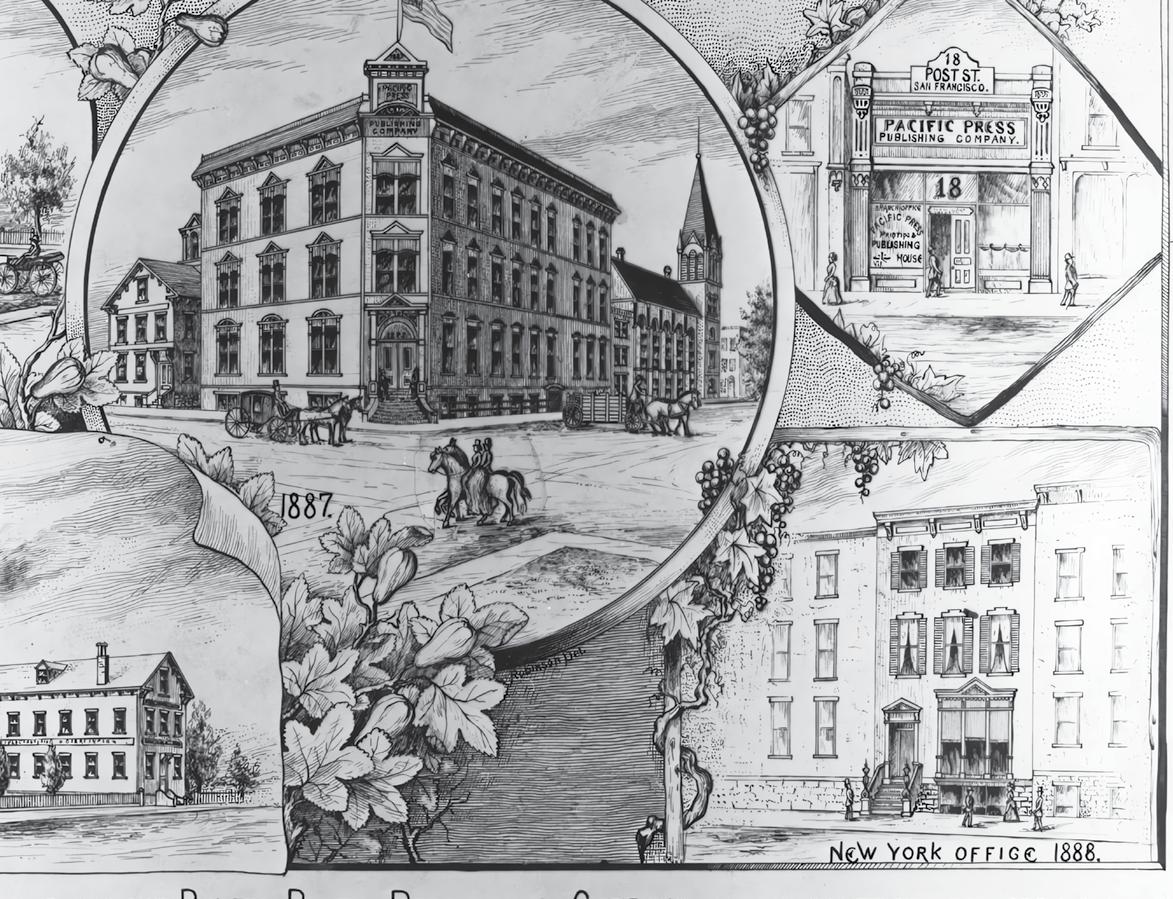

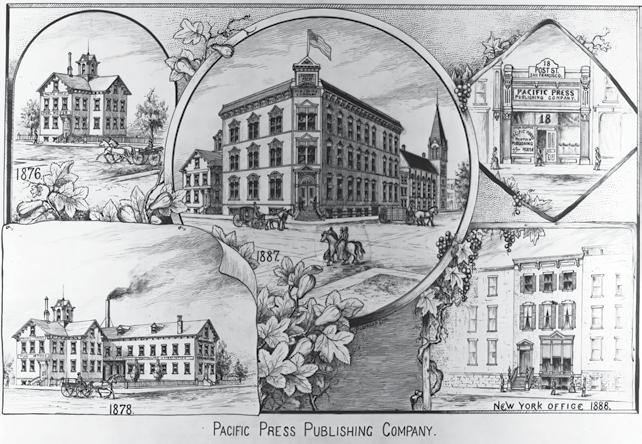

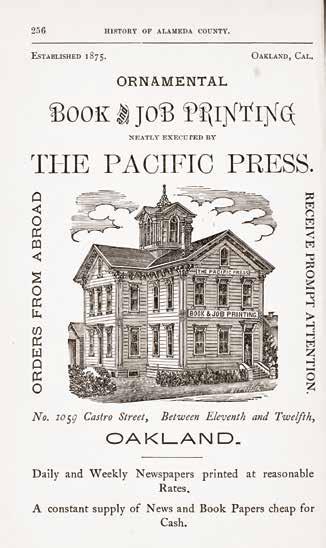

77 Beginnings: Pacific Press

81 Inventing a New Church Structure

85 John Burden

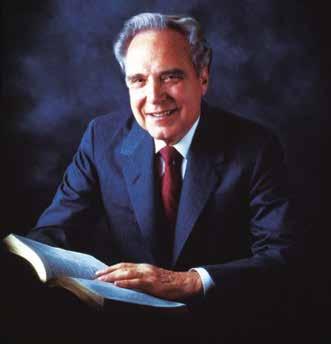

89 H.M.S. Richards

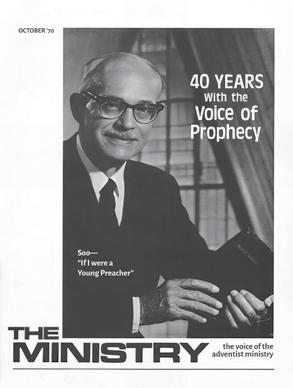

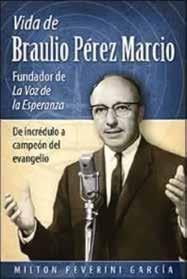

93 Braulio Pérez Marcio

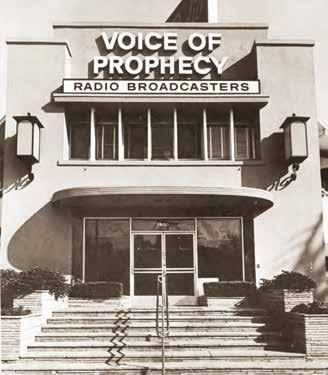

97 Beginnings: Media Ministries

101 Diversity in Mission

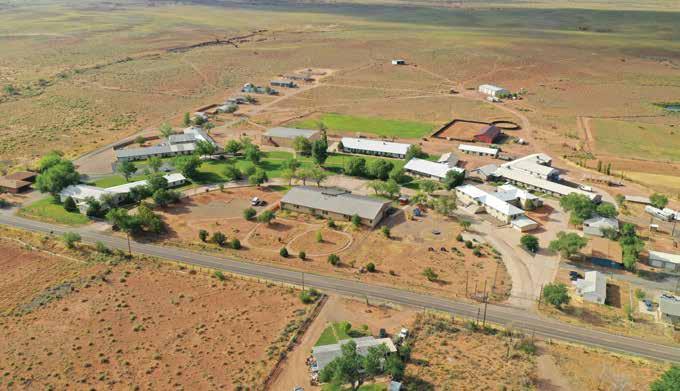

107 Holbrook Indian School

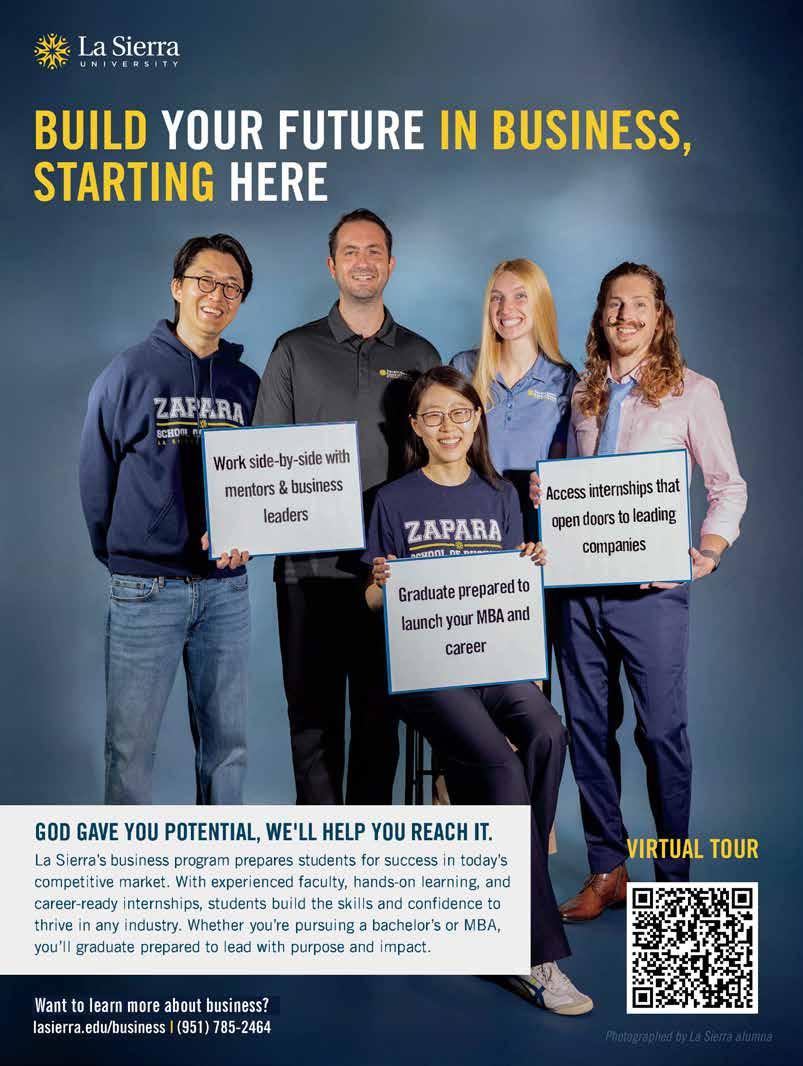

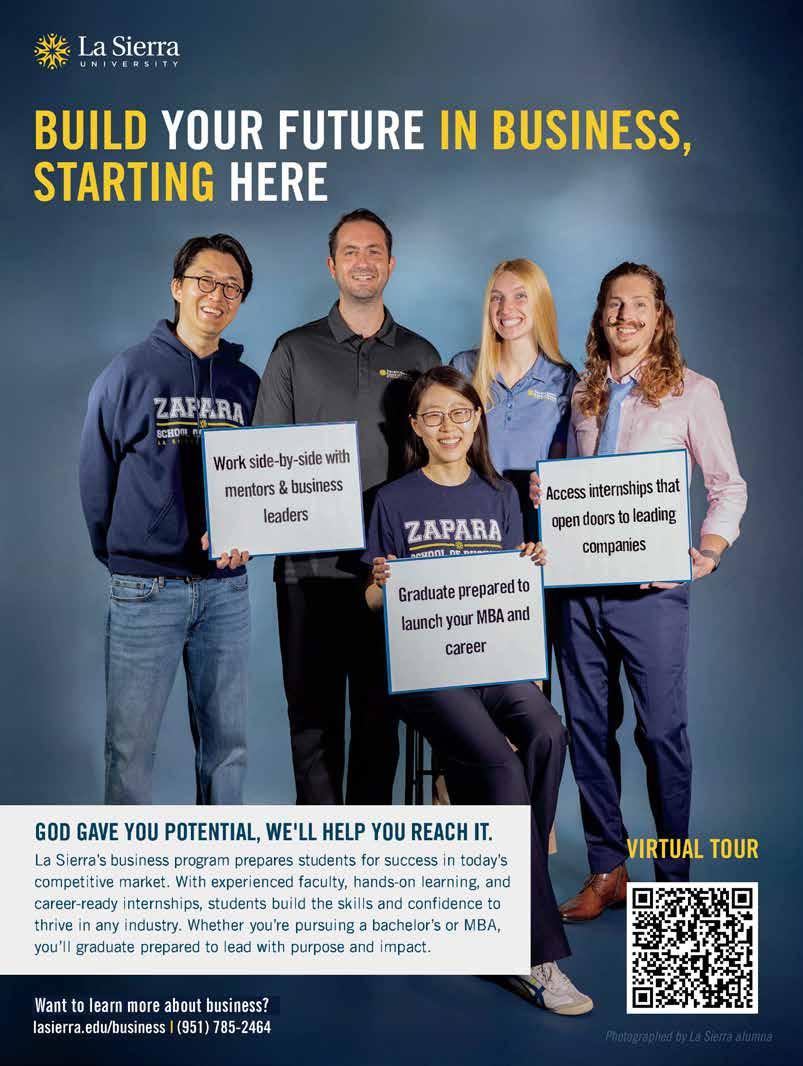

113 La Sierra University

119 Pacific Union College 125 Elmshaven

128 Path of Hope & Healing

131 An Amazing Beginning 136 Investing in Educators

140 A Training Center for Worldwide Outreach

Publisher Ray Tetz

Editor Alberto Valenzuela

Assistant Editor Connie Jeffery

Design/Layout

Stephanie Leal • Alberto Valenzuela

Printing

Pacific Press Publishing Association www.pacificpress.com

144 Rescuing Samuel Rhodes

This special issue of the Pacific Union Recorder is a historical overview of the work of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the Pacific Southwest. At the heart of this project is the vision and dedication of my colleague, Alberto Valenzuela, editor of the Recorder. Although he is inclined to give credit to the Recorder editorial staff, this issue reflects his tireless effort and personal commitment to telling our story well. The dedication of the entire editorial team—their pursuit of winsome and accurate content, presented with care and clarity in both word and design—has produced a resource that will serve our church family well for years to come.

—Ray Tetz, publisher

By Bradford C. Newton

Remember using a map? In these days of Apple Maps, Google Maps, and MapQuest, consulting a paper map is a bygone practice. Yet, it doesn’t seem that long ago that when a road trip was at hand, the Road Atlas would be opened at the kitchen table, and we’d use a highlighter and pencil to plan our route. Back then, the process of finding your way was prone to unexpected road closures, traffic jams in strange cities, and the fervent hope that you didn’t miss the crucial next turn.

Finding our path along the road of life is obviously more complicated, with many more challenges in comparison to a car trip. Marriage, job responsibilities, moving to a new city, caring for children or aging parents, relationship with God and church, healthcare issues, and times of profound loss are just some of the matters about which we search for guidance and direction.

“How can I know God’s will for my life?” is a question we each confront no matter our age, profession, personal circumstances, or economic status. How thankful I am for wise parents, good friends, committed teachers, experienced colleagues, and most of all my wonderful wife, who have helped me in seeking life pathways that honor God and bless me.

How did it happen that these precious people were in my life at just the right time? It was not happenstance or by accident. When I was a teenager, I recall my pastor sharing Psalm 37:4-5

with me, “Delight yourself also in the Lord, and He shall give you the desires of your heart. Commit your way to the Lord, trust also in Him, and He shall bring it to pass.”1 It remains a go-to passage for me to this day.

Every believer can experience God’s leading along the pathway of life. He longs that each of His children experience direction, purpose, meaning, and even joy when facing their biggest problems or decisions. For generations of Christfollowers, finding the pathway of life has meant employing essential spiritual principles to discover God’s will.

Principle 1: Anchor every decision in the Word of God. Psalm 119:105 says, “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.” There is no better place to start than the Bible for building the solid foundation for our decisions. Psalm 119:11 declares, “Your word I have hidden in my heart, that I might not sin against You.” Even when we can’t see everything ahead, we do know One who has been there before. When we root ourselves in Bible truths, we are on safe ground. Psalm 119:165 says, “Great peace have those who love Your law, and nothing causes them to stumble.”

Principle 2: Seek God daily in prayer. Finding God’s leading for life comes in the context of our daily conversations with Him. “Prayer is the opening of the heart to God as to a friend” (Ellen G. White, Steps to Christ, p. 93). When we share

both our joys and disappointments with Him, a growing trust and spiritual intimacy grows. Philippians 4:6-7 advises, “Be anxious for nothing, but in everything by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God; and the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.” We can trust Him as we grapple with important life decisions. Proverbs 3:5-6 promises, “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding; in all your ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct your paths.”

Principle 3: Seek wise counselors. Proverbs give timeless advice about where to seek counsel. Proverbs 12:26 says “The godly give good advice to their friends; the wicked lead them astray” (NLT). These sources are biblical in content and prayerful in practice. God gives this directive, “Where there is no counsel, the people fall; but in a multitude of counselors there is safety” (Proverbs 11:14).

Principle 4: Watch for divine direction through circumstances. When you are reading the Bible, praying over a decision, and listening to godly counselors, there may also be ways that God is speaking through circumstances that are forming around you. Romans 8:28, 31 reminds us, “And we

know that all things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to His purpose…. If God is for us, who can be against us?” When we have placed our trust in our Heavenly Father, we can be assured that we are not forsaken and that He will guide us to the best path.

Principle 5: Does this decision glorify God? As choices present themselves, the first consideration is how this impacts my commitment as a follower of Jesus. “Therefore, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Corinthians 10:31). Will the path before you take you closer to the Lord or draw you away from Him?

However, sometimes we make poor decisions. Or we do our best and things still don’t work out as we hoped. What then? We live in a sinful world, and we ourselves are part of this system. There is forgiveness when we fail. When things go badly, we are not alone. God assures us, “Be strong and of good courage.… And the Lord, He is the One who goes before you. He will be with you; He will not leave you nor forsake you; do not fear nor be dismayed” (Deuteronomy 31:7-8).

As we travel the path of this life, we do so with our Greatest Friend on the journey. His promise remains that in the end a wonderful future awaits each of us. “I will come again and receive you to Myself; that where I am, there you may be also” (John 14:3).

Bradford C. Newton is the president of the Pacific Union Conference.

1Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version.

Every believer can experience God’s leading along the pathway of life. He longs that each of His children experience direction, purpose, meaning, and even joy when facing their biggest problems or decisions.

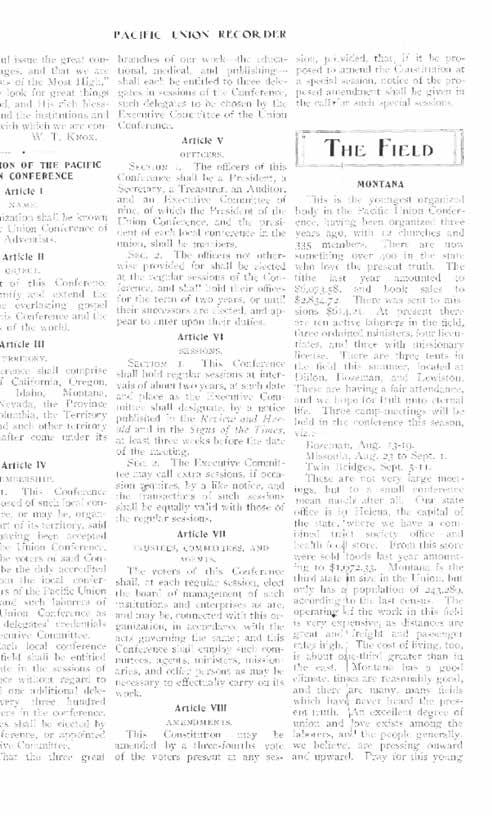

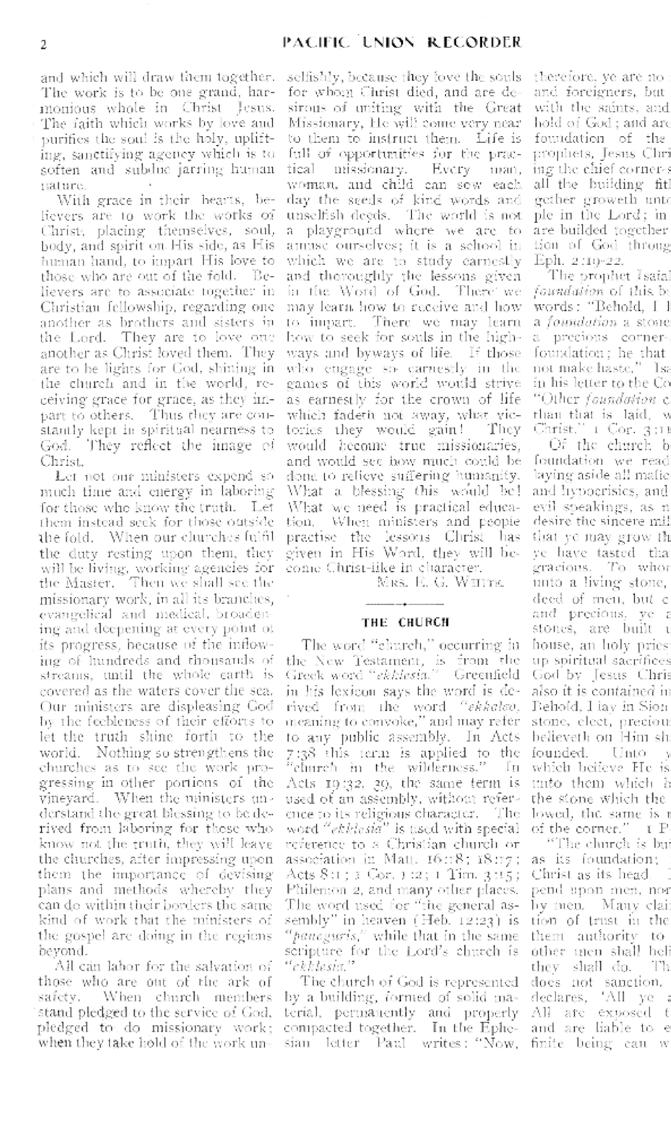

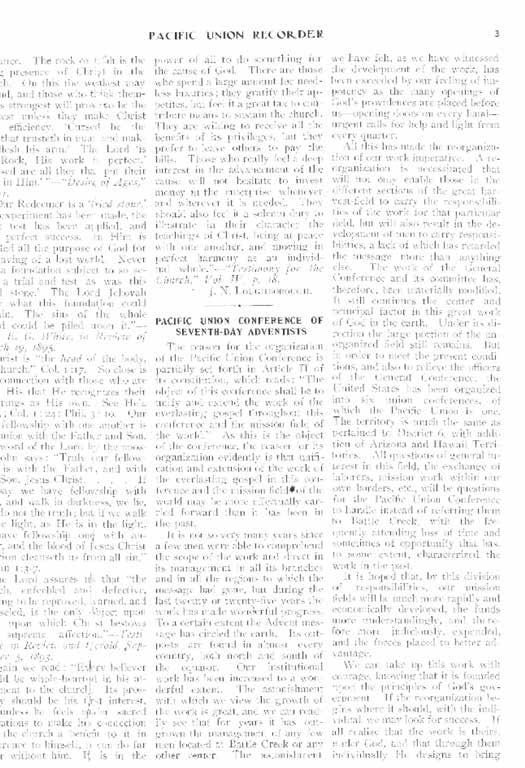

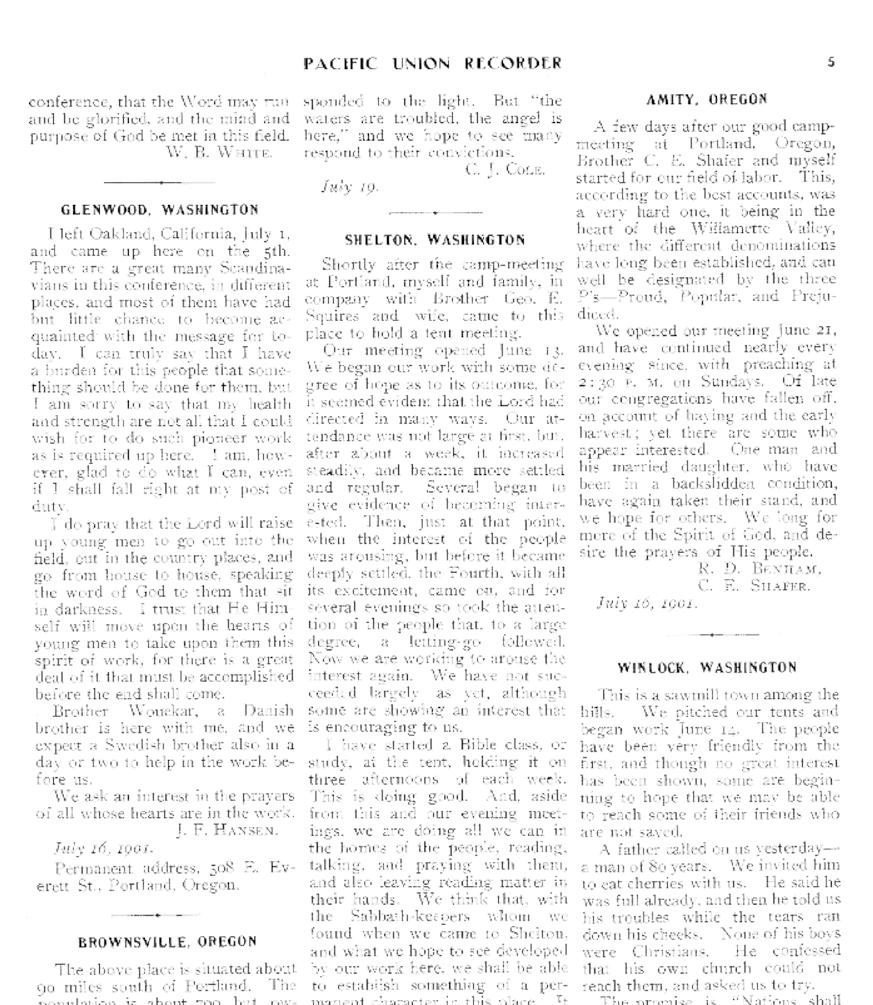

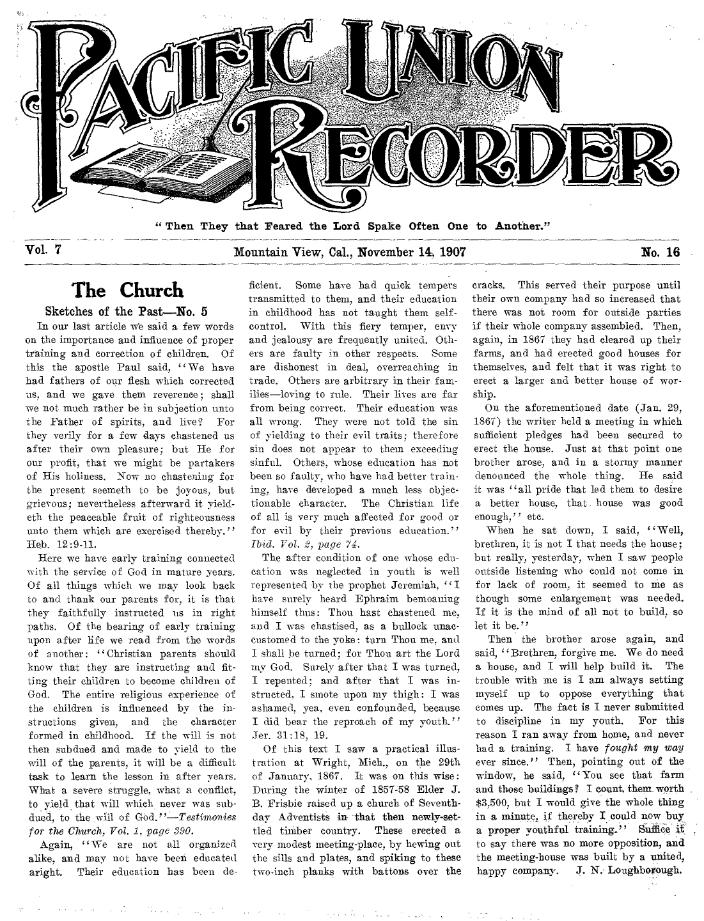

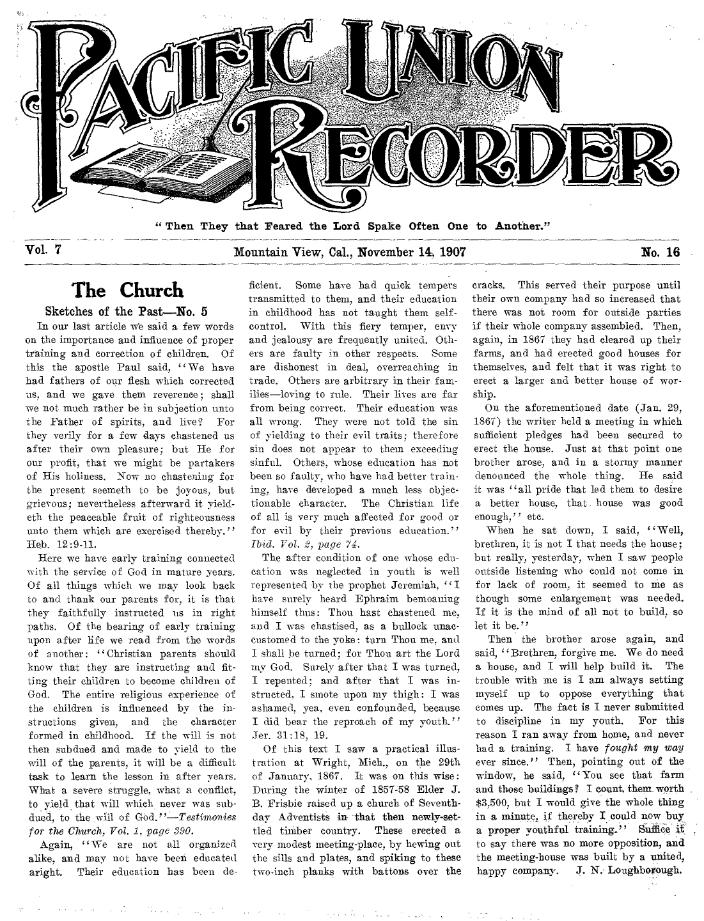

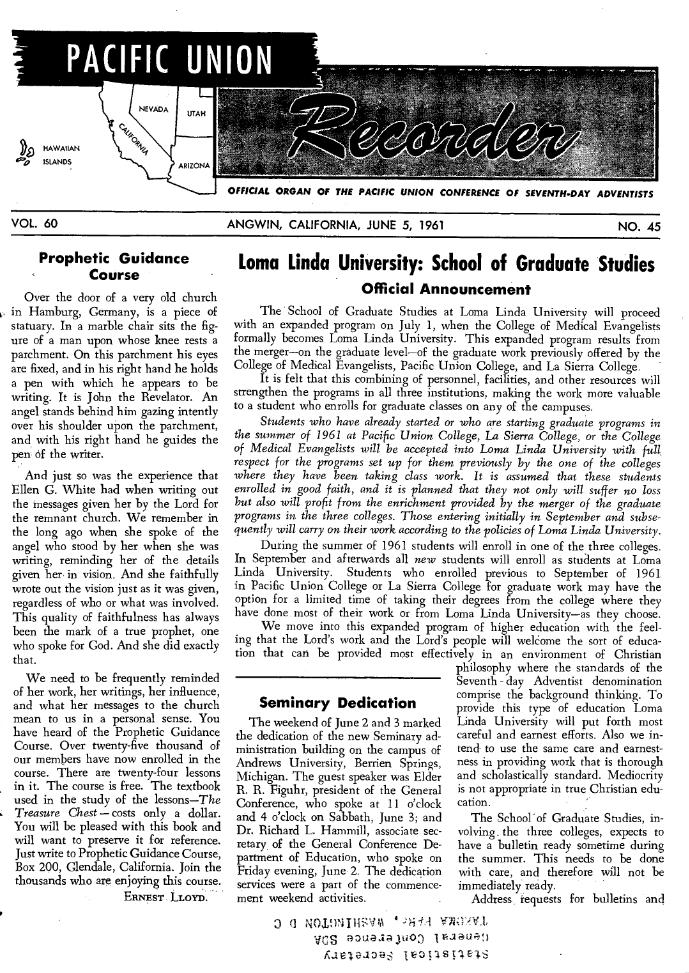

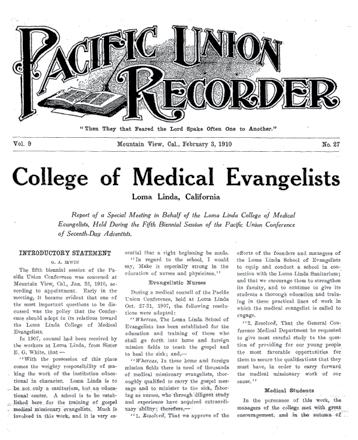

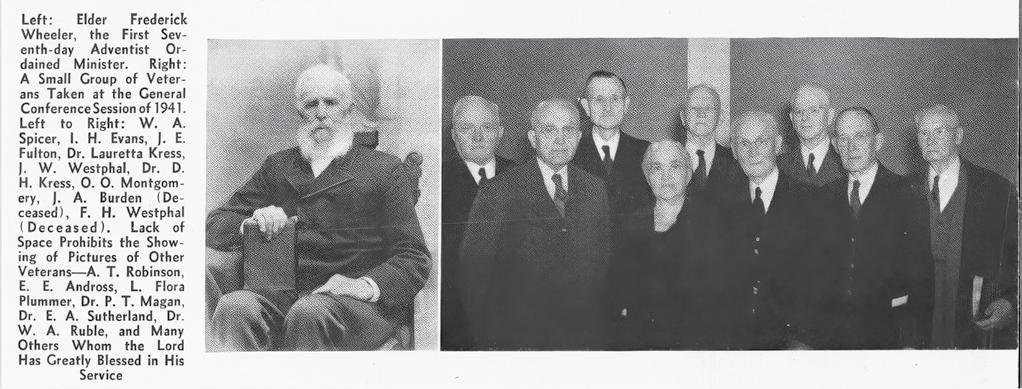

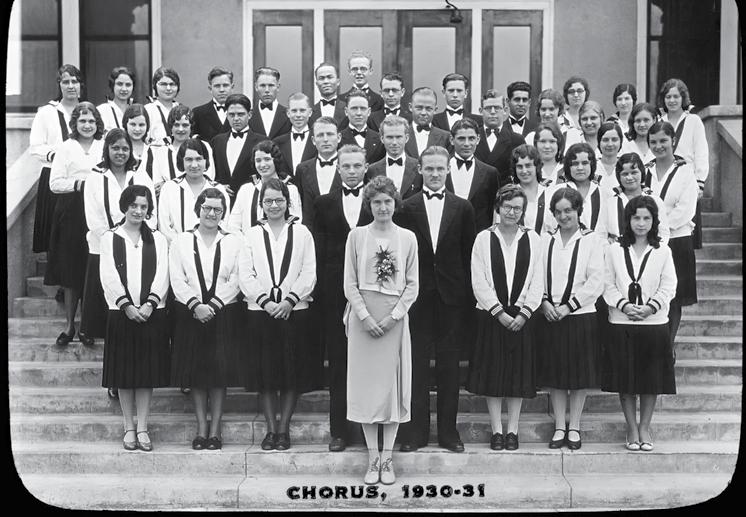

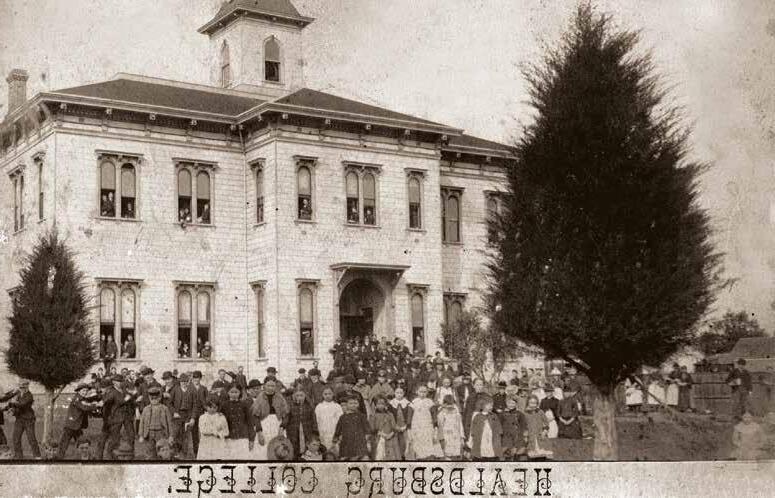

The Pacific Union Recorder first saw the light of day on August 1, 1901. In the many years since then, it has reported on a myriad of church activities, faithful members, and significant events, often of global significance. This short article attempts to capture some of the history and flavor of what has become essential reading for many in the Pacific Union and beyond.

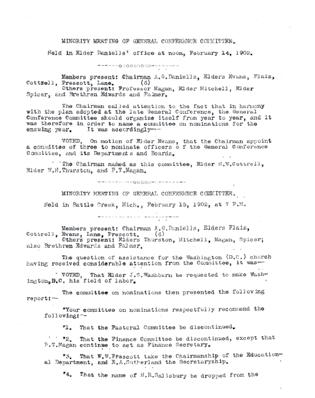

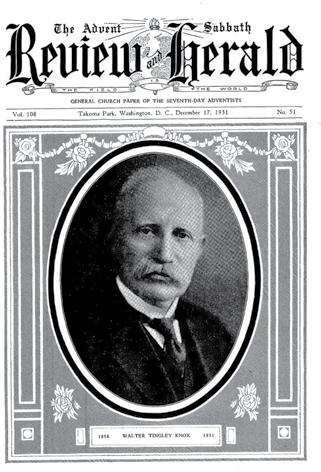

That first issue saw two major articles by Ellen White (“True Missionary Work”) and John Loughborough (“The Church”), followed by an explanation of the formation of the new Pacific Union Conference by its first president, W.T. Knox. He told readers that the development of church work required the establishment of new organizations. “In order to meet the present conditions, and also to relieve the officers of the General Conference, the United States has been organized into six union conferences, of which the Pacific Union is one.” He added, “All questions of general interest in this field, the exchange of laborers, mission work within our own borders, etc., will be questions for the Pacific Union Conference to handle instead of referring them to Battle Creek.”1 This meant the development of a new constitution for the Pacific Union, which interestingly did not even contain any reference to the General Conference!

The editors of the new Recorder explained that “when the organization of the Pacific Union Conference was completed, it was thought it would be a help to the union, as well as to the state,

conference work in this district if a paper was published to represent all parts of the work which is being carried on.”2 Consequently, the Recorder replaced the various local conference papers that had been operating up to that time. It was to be produced every two weeks, and the cost was 50 cents a year.

In that first issue, one major development was announced—that of the first Adventist missionaries being sent to Alaska. This was to be a continuing theme for the Recorder—reporting on advances in new areas, and not only in the local region but far overseas. The Recorder for Nov. 20, 1902, carried

a report by Alonzo Jones, then president of the California Conference, that missionaries from that conference were being sent to England, Ireland, Italy, Georgia, France, Spain, South Africa, Germany, Canada, and China. He commented, “Nearly all of these are still California workers, to be paid from the California treasury after they reach their foreign fields.”3 Reporting to the General Conference, Jones stated, “The amount of tithe now going to foreign fields from the California Conference is practically half the amount raised in the Conference.”4 This local initiative for mission work reported by the Recorder demonstrated tremendous commitment by

the members in the union who knew these workers and kept in regular contact.

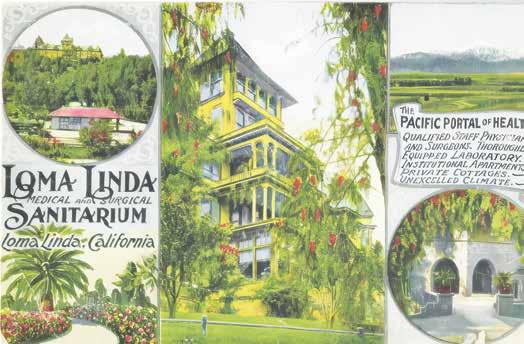

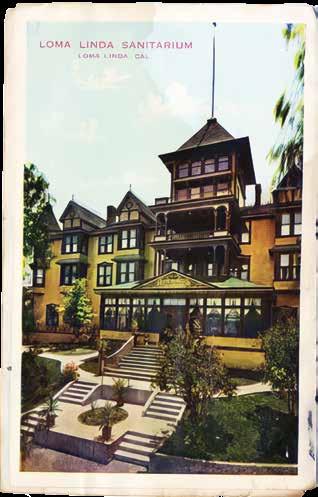

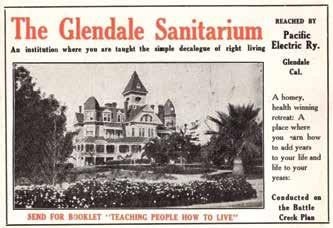

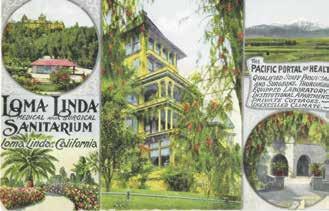

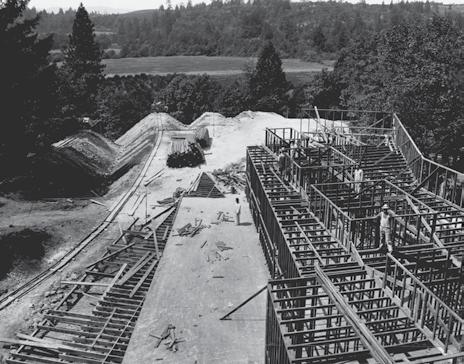

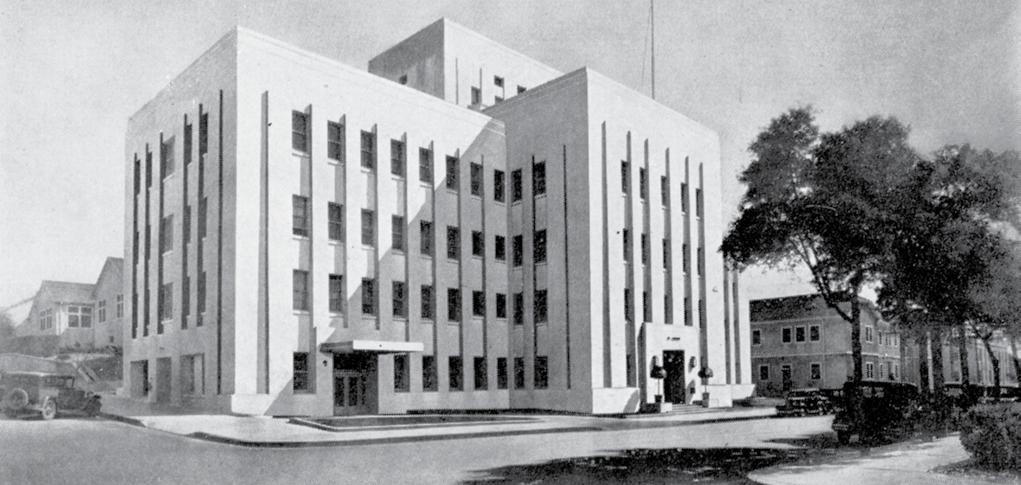

After the purchase of Loma Linda in 1906, the Recorder carried a long report of recommendations for the running of the new College of Medical Evangelists, even down to including details of the proposed syllabus!5 Such reporting regarding this flagship institution has continued over the years. For example, in 1910 there was a long article detailing the plans for Loma Linda voted by the fifth session of the Pacific Union Conference.6 In 1937, the Recorder reported the building of the chapel and the library at Loma Linda.7 Plans for a

new Dental School were detailed in the Recorder in 1952.8 The College of Medical Evangelists became Loma Linda University in 1961, and the Recorder published the official announcement.9 In January 2011, the Recorder published details of the Proton Treatment Center’s 20th anniversary.10 A global search of the Recorder’s archives reveals 3,210 references to Loma Linda.

Similarly Pacific Union College was frequently featured in the Recorder. For example, B.M. Shull ended his article on the college by asking: “Why should we not as one man take hold and push our educational work, and make Angwin a great college, the Harvard of Seventh-day Adventists?”11

But the Recorder did not carry only church-related news. It also reacted to significant world events such as World War I. In August 1914, the president of the Pacific Union, E.E. Andross, addressed the membership with an article entitled “The Great Crisis Upon Us,” while in the same issue writer Ernest Lloyd contributed a piece called “All Europe Plunges into War.”12

The Great Depression also called for comment, such as, “Then came the great depression and property values and earnings tumbled till many lost

not only all their gains, but their former holdings as well. Then many lamented that they had not been more liberal, and that they had not sold and placed their money in the cause.” 13 At the heart of the depression, the church produced a brochure promoted by the Recorder entitled “Welfare Work by Seventh-day Adventists” giving practical recommendations for helping the needy. 14

The Recorder also noted many of the welfare contributions of the church’s Dorcas Societies during this time.

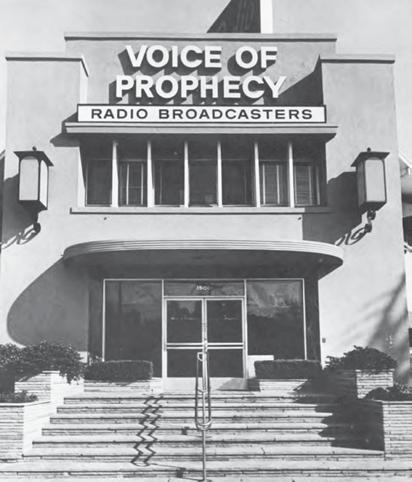

Anticipating the beginning of World War II, the Recorder published a warning from the Pacific Union committee three days before war was declared. 15 The Recorder also published requests that came into the Voice of Prophecy asking for materials related to the war. 16

The Recorder has seen many changes in format and presentation. It began as a 16page broadsheet in Times Roman font with no illustrations. Over the years this has changed, until today it is presented as a monthly full-color magazine of some 60 to 80 pages. But its primary

purpose has not changed since 1901: “a paper… published to represent all parts of the work which is being carried on.”

1W.T. Knox, “Pacific Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists,” Pacific Union Recorder (Aug. 1, 1901), pp. 3-4.

2“Pacific Union Recorder,” Pacific Union Recorder (Aug. 1, 1901), p. 16.

3A.T. Jones, “To the People of the California Seventh-Day Adventist Conference,” Pacific Union Recorder (Nov. 20, 1902), p. 2.

4“Minority Meeting of General Conference Committee,” p. 121, https:// documents.adventistarchives.org/Minutes/GCC/GCC1902.pdf.

5“The Council of the Medical Department of the Pacific Union Conference,” Pacific Union Recorder (Nov. 14, 1907), pp. 2-4.

6“College of Medical Evangelists,” Pacific Union Recorder (Feb. 3, 1910), pp. 1-7.

7“Our Institutions,” Pacific Union Recorder (Feb. 10, 1937), p. 3.

8M. Webster Prince, “Plans for the New Dental School at Loma Linda,” Pacific Union Recorder (July 21, 1952), pp. 1, 8.

9“Loma Linda University: School of Graduate Studies,” Pacific Union Recorder (June 5, 1961), p. 1.

10James Ponder, “Festivities Mark 20th Anniversary of Proton Treatment Center,” Pacific Union Recorder (Jan. 2011), p. 24.

11B.M. Shull, “A Patron’s View-point,” Pacific Union Recorder (Feb. 17, 1910), p. 7.

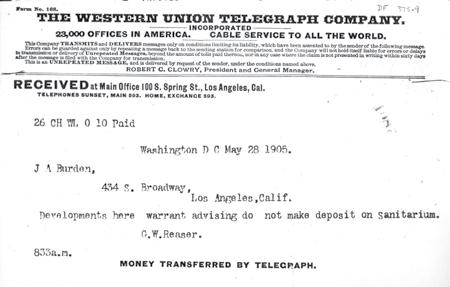

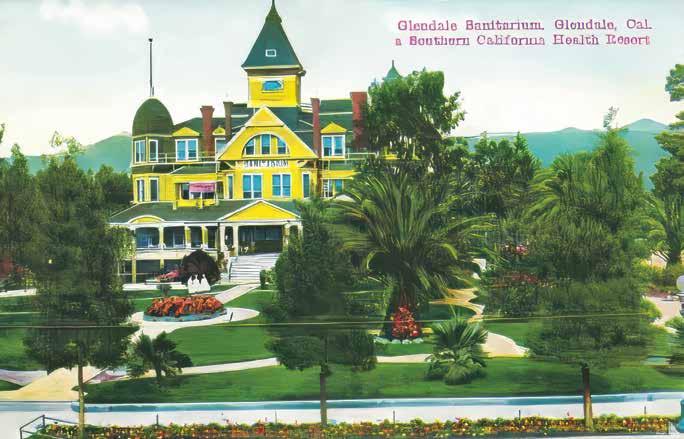

12Ernest Lloyd, “All Europe Plunges into War,” Pacific Union Recorder (Aug. 6, 1914), pp. 1-2.

13G.A. Roberts, “At the Island of Speculation,” Pacific Union Recorder (Nov. 20, 1924), p. 2.

14“Welfare Work,” Pacific Union Recorder (July 21, 1932), p. 2.

15“An Appeal from the Pacific Union Conference Committee,” Pacific Union Recorder (Sept. 6, 1939), p. 1.

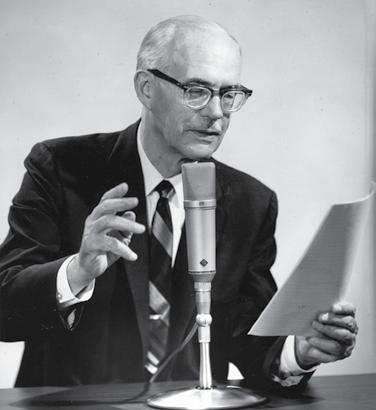

16“Voice of Prophecy,” Pacific Union Recorder (Sept. 27, 1939), p. 3.

By Alberto Valenzuela

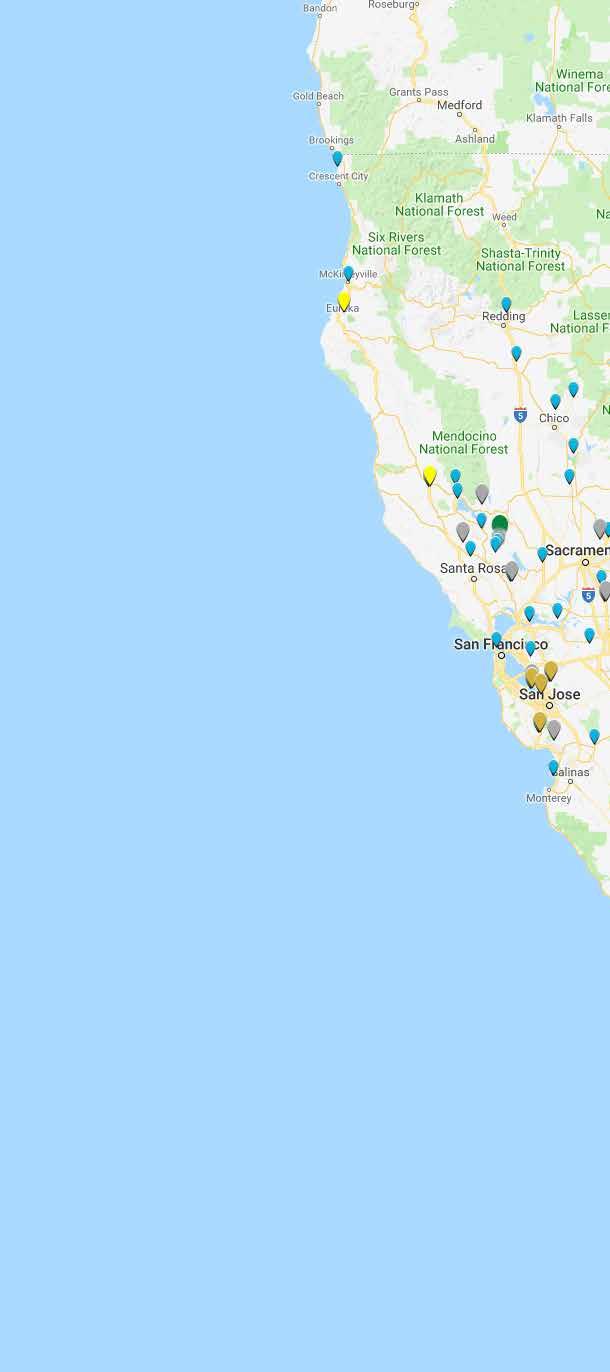

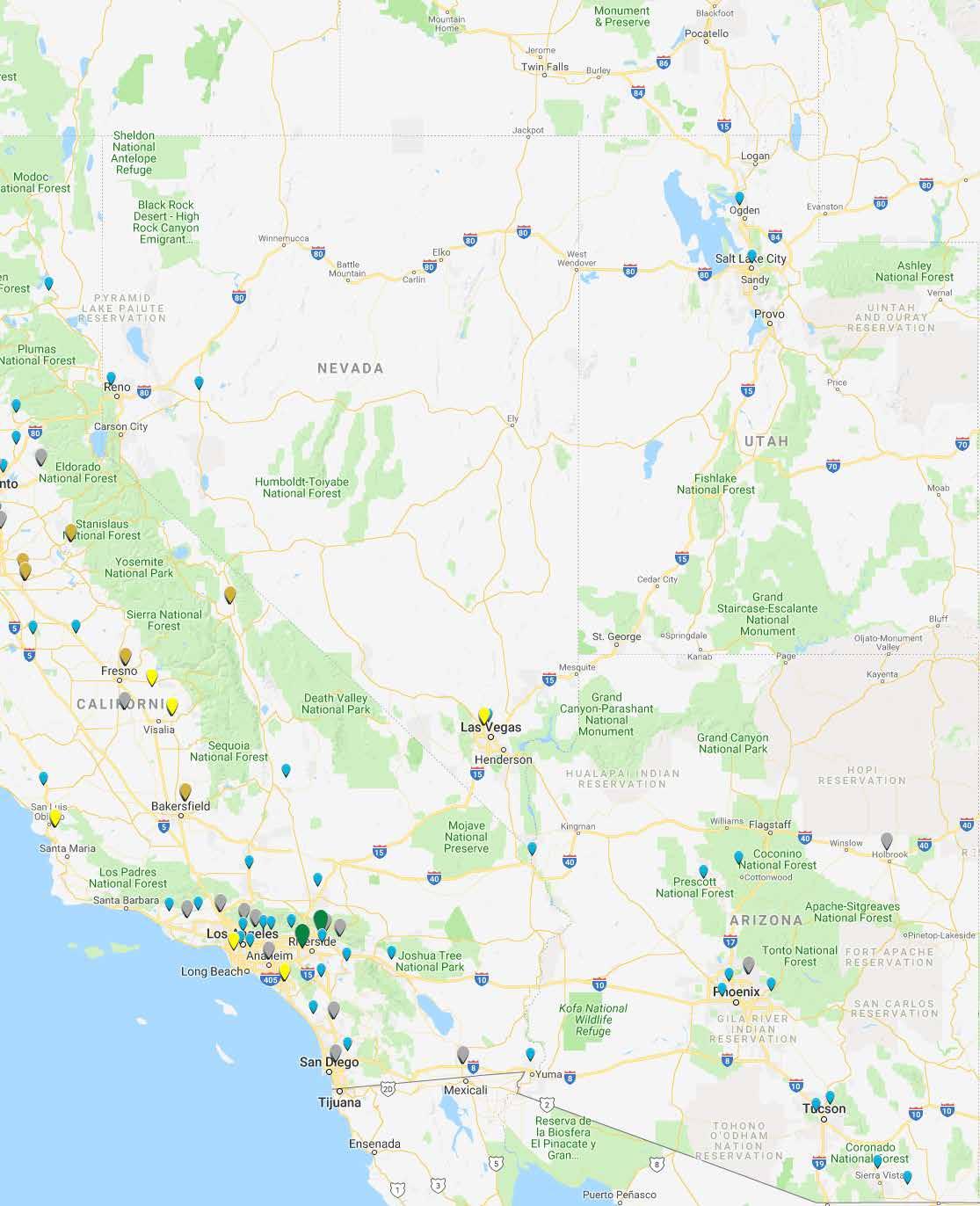

The Pacific Union Recorder stands as a cornerstone in the landscape of Adventist media, serving the vibrant and diverse community within the Pacific Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Covering the states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Hawaii, the Recorder has been a trusted source of news, inspiration, and connection for Adventist members and institutions for over a century.

Founded in 1901, the Recorder has evolved alongside the Adventist Church, adapting to the changing times while staying true to its mission of fostering spiritual growth and community cohesion. Initially a simple newsletter, it has grown into a sophisticated publication with a wide readership. The Recorder’s dedication to quality journalism and its commitment

Founded in 1901, the Recorder has evolved alongside the Adventist Church, adapting to the changing times while staying true to its mission of fostering spiritual growth and community cohesion.

El símbolo de la mayordomía

Un recorrido hacia la excelencia

The Recorder en español is the only publication of its kind in the North American Division, although other union papers may include a few pages in Spanish.

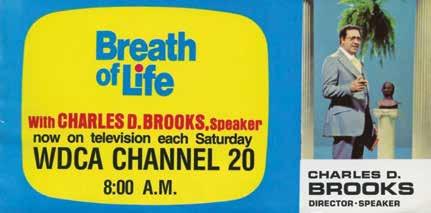

to addressing the spiritual and practical needs of its readers have cemented its role as an indispensable resource within the Adventist community.

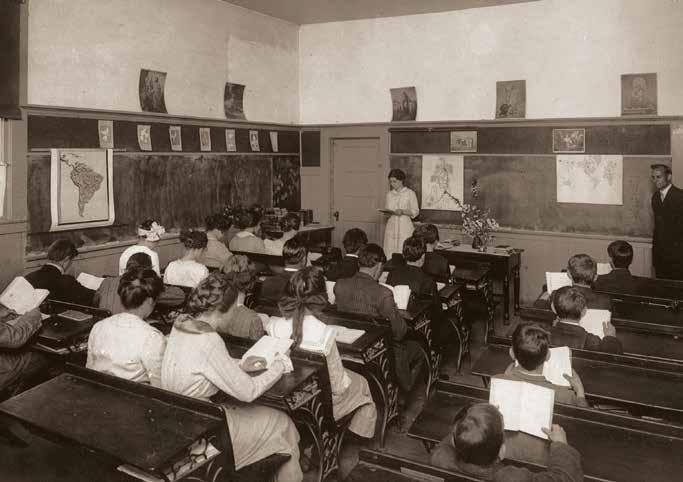

At its core, the Recorder is dedicated to spiritual nourishment. Each issue features a variety of articles aimed at deepening the faith and understanding of its readers. These include Bible studies, devotionals, and theological reflections authored by respected church leaders and scholars. The publication also highlights testimonies and personal stories of faith, offering readers tangible examples of God’s work in the lives of fellow Adventists.

Helping members stay informed about the latest developments within the church and the broader Adventist community is a key function of the Recorder. The publication covers a broad spectrum of news, from local church and conference activities to international events and initiatives. By providing timely and accurate reporting, the Recorder helps its readers stay connected with the wider church

community and informed about important issues and trends.

The Pacific Union Conference is home to numerous educational institutions and healthcare facilities, and the Recorder regularly features news and updates from these sectors. Articles on educational achievements, new programs, and health initiatives underscore the Adventist commitment to wholistic development—spiritually, mentally, and physically. These sections not only inform but also inspire readers to engage with and support Adventist education and healthcare ministries.

Recognizing the diversity within the Pacific Union Conference, the Recorder celebrates the unique cultural contributions of its members. Stories and features on cultural events, heritage celebrations, and community outreach programs highlight the rich tapestry of the Adventist community in the Pacific Union. This inclusivity fosters a sense of belonging and unity among

readers from different backgrounds and regions.

In recent years, the Recorder has embraced digital transformation to meet the evolving needs of its audience. While the print edition remains popular, the Recorder’s online presence has expanded significantly. The digital version offers enhanced accessibility, allowing readers to engage with content on various devices and platforms. Interactive features, multimedia content, and social media integration have further enriched the reader experience, making the Recorder more dynamic and engaging than ever before.

In consideration of the large Spanish-speaking membership of the Pacific Union, beginning in 2018, the Recorder began to be published quarterly in Spanish and was drop-shipped directly to the Spanish churches of the seven conferences in the union’s territory. From its first publication, this quarterly Recorder en español has aimed to cover stories and articles of particular interest to its Spanish-speaking readers.

While the English-language Recorder has appeared online for some time, January of 2023 saw the online appearance of the Recorder en español on a monthly basis. The monthly online version of the

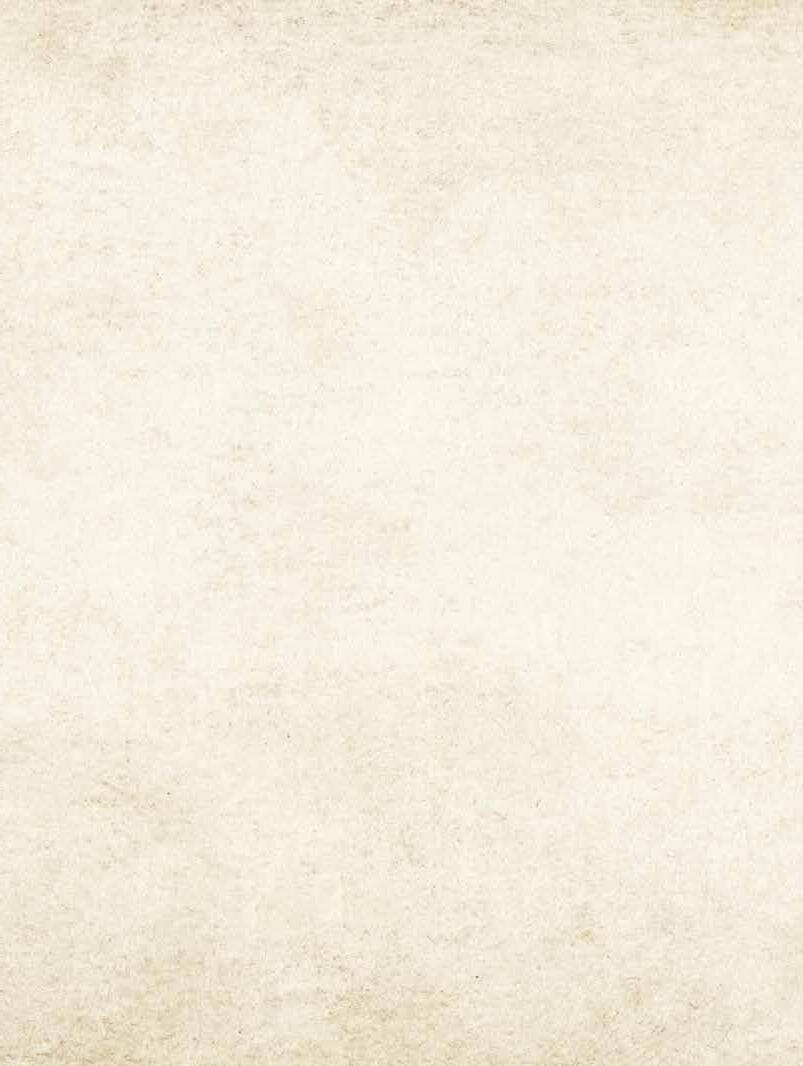

Recorder en español includes every article and news story that appears in the English-language Recorder. The Recorder en español is the only publication of its kind in the North American Division, although other union papers may include a few pages in Spanish.

Beginning in 2023, every article and news story that appears in the Recorder automatically appears on the websites of Pacific Union churches that take advantage of the web services of Adventist Church Connect. Three new stories—in English and in Spanish—from the Recorder appear every day, Monday through Friday. The stories are placed automatically on the websites of the local churches, bringing them readily to most of the churches throughout our territory.

The influence of the Recorder extends beyond its role as a news source. It acts as a unifying force, bringing together a geographically dispersed and culturally diverse community. By sharing stories of faith, reports on church activities, and articles on relevant issues, the Recorder fosters a sense of shared identity and purpose among its readers. An example of this has been the production of the April education issue of the Recorder, which has appeared since 2018. This issue has served to

promote Adventist education as well as to inspire support for the church’s educational entities. Articles about former and current students, teachers, and personnel, as well as photos of students from the many diverse schools—from a two-room elementary school to a college or university—have been the standard of every special education issue.

Furthermore, the Recorder’s commitment to highquality journalism and ethical reporting strengthens the credibility of the Adventist Church within and beyond its own community. It serves as a model for other church publications, demonstrating the power of thoughtful, well-crafted communication in advancing the mission of the church.

The Pacific Union Recorder is more than just a publication; it is a vital lifeline that connects, informs, and inspires the Adventist community in the Pacific

Covering the states of California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Hawaii, the Recorder has been a trusted source of news, inspiration, and connection for Adventist members and institutions for over a century.

Union Conference. As it continues to adapt and grow, the Recorder remains steadfast in its mission to support the spiritual, educational, and communal needs of its readers. For Adventists in California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and Hawaii, the Recorder is an indispensable resource that enriches their faith journey and strengthens their connection to the broader Adventist family.

Alberto Valenzuela is associate director of communication and community engagement of the Pacific Union Conference and the Recorder editor.

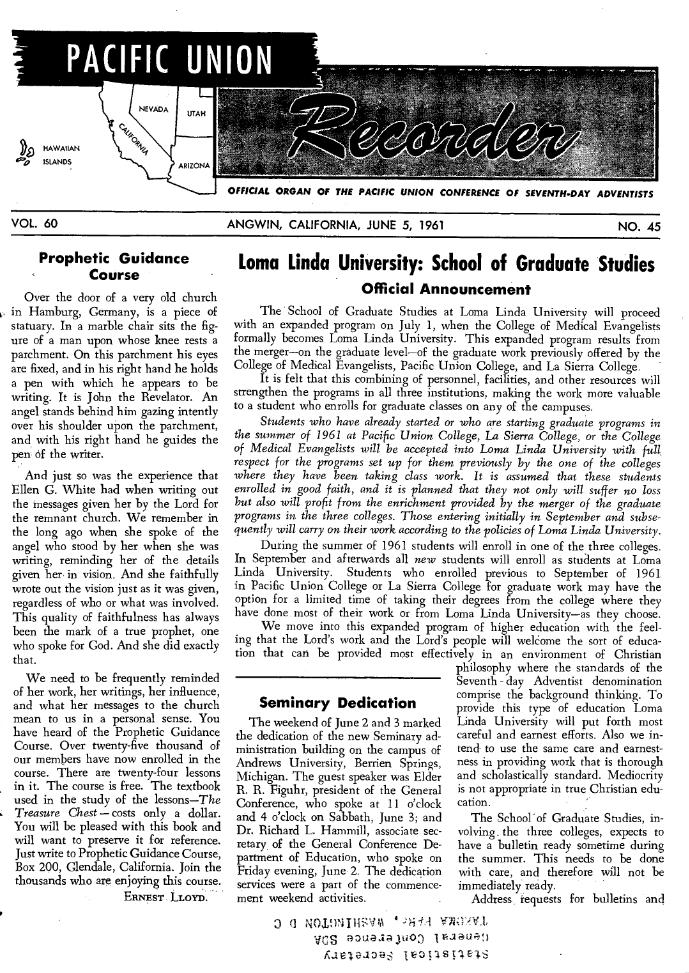

How and when did racial discrimination become embedded in Adventist institutions? Is it possible to change patterns of injustice when they become deeply ingrained in the corporate life of the church? Is it appropriate to organize in opposition to the voted policies of duly elected church leaders? May Christians use protest and pressure to bring about change in the church? Were Black conferences a step forward or backward?

In Change Agents, Douglas Morgan sheds light on such questions by telling the story of a movement of Black Adventist lay members who, with women at the forefront, brought the denomination to a racial reckoning in the 1940s. Their story, told in the context of the church’s racial history in America as it unfolded during the first half of the 20th century, illumines the often difficult but necessary conversations about race that challenge the church today. And it offers inspiration and insight to Adventists today whose love for their church drives a dedication to changing it.

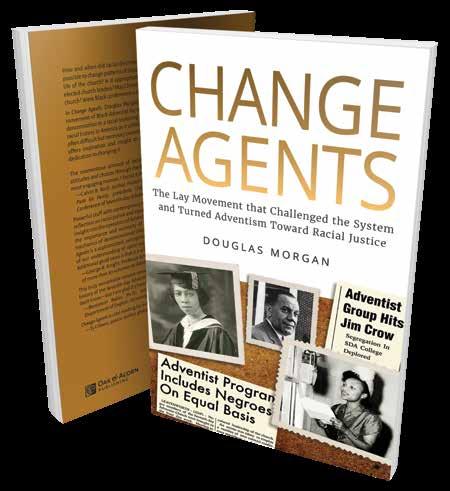

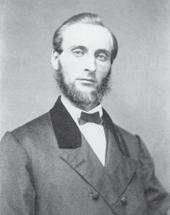

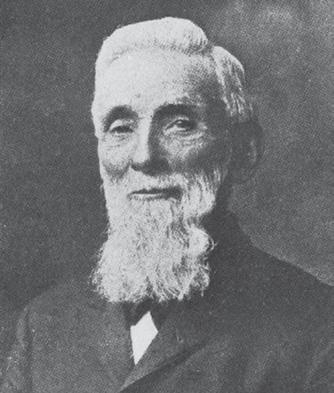

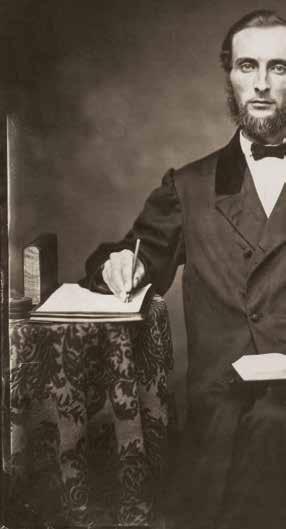

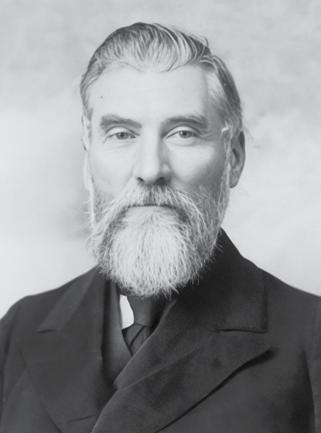

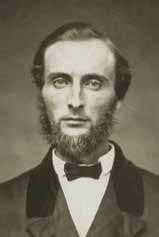

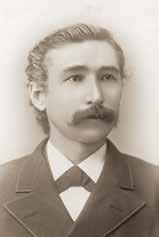

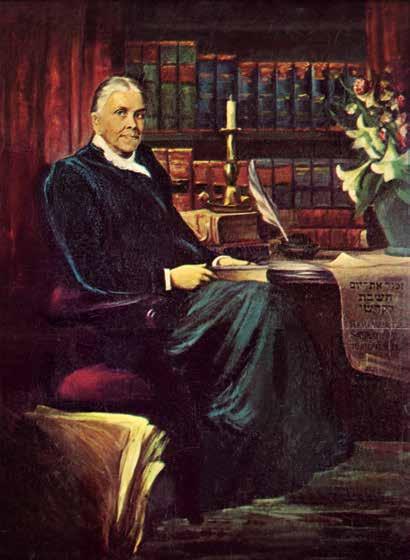

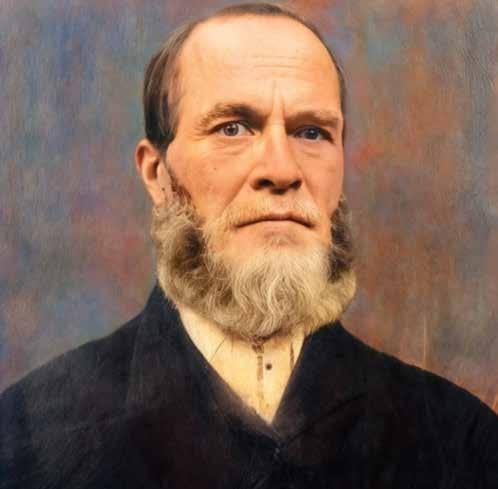

Ellen White’s role in the West began before she ever visited! In 1868, before evangelists J.N. Loughborough and D.T. Bourdeau had even boarded their ship for San Francisco, Ellen White had a vision in Battle Creek as to how to work in California. In a letter that was received by Loughborough and Bourdeau soon after they arrived, she explained that methods used in the East would not be appropriate in the West. She urged a spirit of liberality, of being open and generous, telling them not to be penny-pinching.

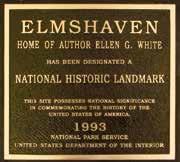

Following this advice, they were successful, both in terms of converts and also in the sale of literature, with James White once commenting, “You are selling more books there than all our tent companies east of the Rockies.”1

In an example of “California liberality,” the new church at Santa Rosa, California, sent $2,000 to Battle Creek for a mutual obligation fund, along with an invitation for James and Ellen White to spend the winter of 1872-73 in California.

The Whites accepted the invitation and traveled to Oakland, California, arriving in September 1872. Then they moved on to meet with J.N. Loughborough in Santa Rosa. Ellen wrote, “We think we shall enjoy our visit to California.”2

James wrote, “We like the people of California, and the country, and think it will be favorable to our

health.... We now have strong hope of recovering health, strength, and courage in the Lord, such as enjoyed two years since.”

3

After speaking at camp meetings and other events, and helping with the organization of the California Conference, they headed back to Battle Creek. However, the Whites liked California so much that they were back again in December of the following year. This time, however, they wanted something more permanent, and they sent helpers ahead to set up a home for them in Santa Rosa. They bought a team of horses and a carriage. They got busy with their writing. Ellen wrote, “I do not think we will attend the eastern camp meetings this coming season. It is of no use to make child’s play of coming to California and running back again.”

4

James and Ellen were convinced to make Oakland the center for the work in California. The forerunner of the Pacific Press was set up there in 1874, and The Signs of the Times began publishing. In fact, the Whites sold everything they had in the East to make this investment possible. Ellen wrote, “We went over the same ground in California, selling all our goods to start a printing press on the Pacific Coast. We knew that every foot of ground over which we traveled to establish the work would be at great sacrifice to our own financial interests.”5

Whites to a new home, Fountain Farm. However due to the demands from the East, Ellen decided to go back. James’ health prevented him from accompanying her, though he joined her later. But they returned to their home in California for the winter, though they arrived late, on February 2. James wrote, “We have felt, and still feel, the deepest interest for the cause on the Pacific.… Failing health and discouragements had led us to withdraw from the general cause to confine our labors to the Pacific Coast.”6

They clearly felt torn about responsibilities “back East,” and they both did what they could, including participating in the Michigan camp meeting. But their hearts and home were in California.

It’s almost as if the work needed to be reinvented in the West—with publishing being the first institution started. This meant another move for the

This pattern was repeated frequently in the following years—camp meetings back East, and then supporting the growing work in California during the winter months. Tragedy struck in August 1881 with the death of James in Battle Creek. Soon afterward, Ellen left for Colorado and then for Oakland to participate in the camp meeting there. At first she stayed in Oakland, but in 1882

she bought a new home in Healdsburg. In 1885 she moved to Europe for two years. In 1891 she sold her Healdsburg home after accepting the brethren’s request that she go to Australia, though she commented that she saw “no light” in this.

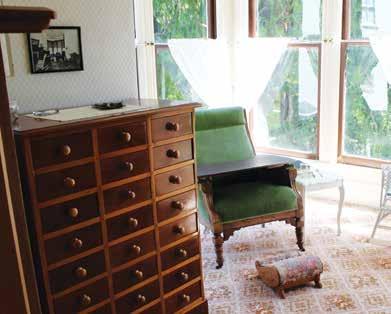

There was no question in her mind that California would be her home when she returned from Australia in August 1900. She purchased her last home, Elmshaven, in St Helena, where she would live for 15 years. She wrote: “It is just the place I need…. This place was none of my seeking. It has come to me without a thought or purpose of mine. The Lord is so kind and gracious to me. I can trust my interests with Him who is too wise to err and too good to do me harm.”7

Ellen was coming home to the West. It seems that this was the place she wanted to be. Of course there were issues of climate and her health. Yes, there were the benefits of good fruit and vegetables, as she makes clear. But most of all it seems her heart was here, even though she had the whole work on her mind. In fact, she had to face many of the issues of the East directly. She had to write strong letters to the brethren, opposing their mindset. She cautioned

them against interfering in the West. She told them “hands off” the Pacific Press. She complained about the rise of “kingly power” in Battle Creek. She warned about the policies being adopted by the institutions there—the Sanitarium and the Review and Herald press. It must have been heartbreaking for her to hear that the Sanitarium was lost to the church and then that both institutions were destroyed by fire in 1902.

Perhaps in reaction to this, she urgently supported the purchase of Loma Linda in 1905 and fought for the independence of the Pacific Press. She was much involved in the purchase of Pacific Union College in 1909. She saw the church making great progress in the West, and she gave her wholehearted support.

1J.N. Loughborough, Miracles in My Life (Payson, AZ: Leaves-of-Autumn Books, 1987 reprint), p. 72.

2Arthur L. White, Ellen G. White: The Progressive Years: 1862-1876, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1981), p. 357.

3Arthur White, The Progressive Years, p. 359.

4Arthur White, The Progressive Years, p. 404; Ellen G. White, letter to W.C. White, Feb. 10, 1874.

5Ellen G. White, The Publishing Ministry (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1983), p. 28.

6Arthur White, The Progressive Years, p. 448.

7Ellen G. White, Manuscript Releases, vol. 21, p. 127.

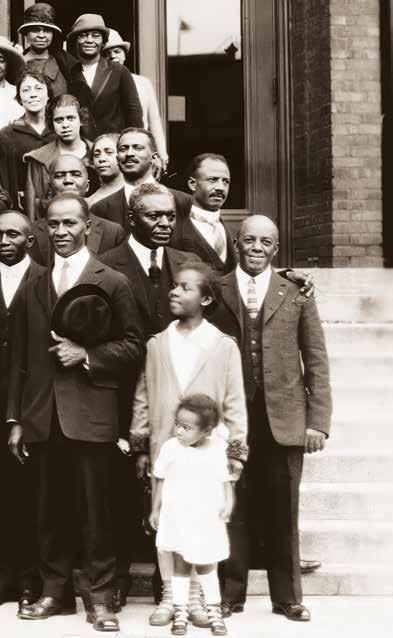

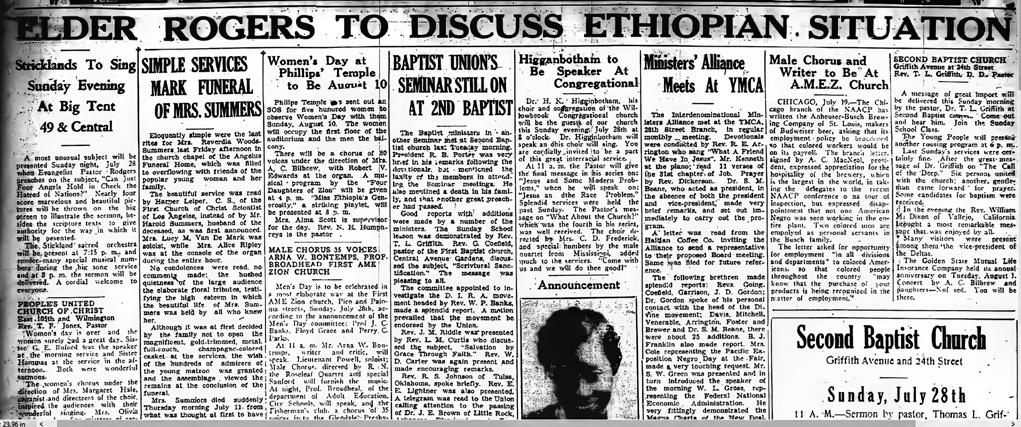

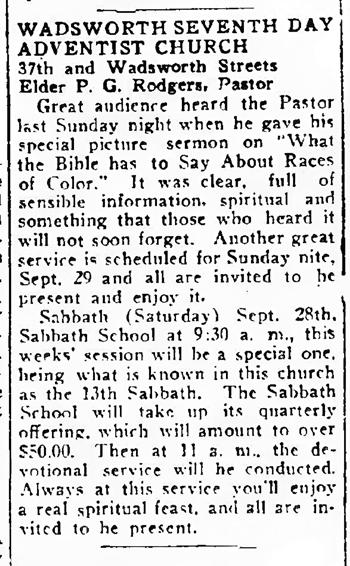

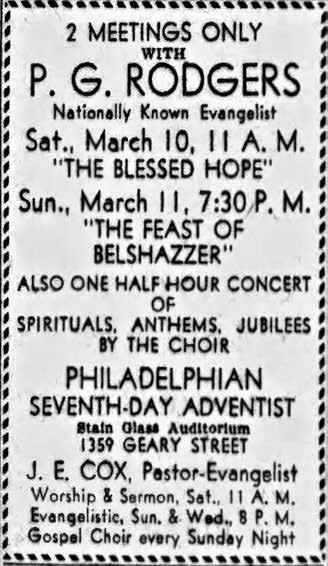

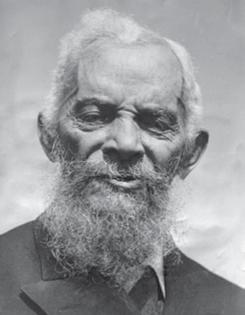

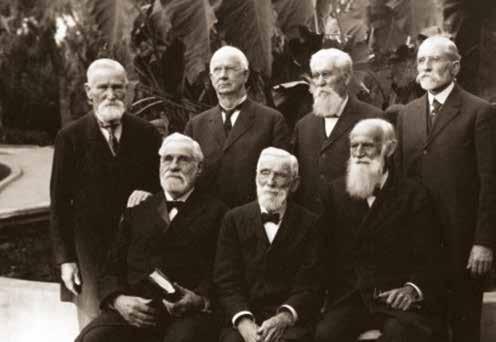

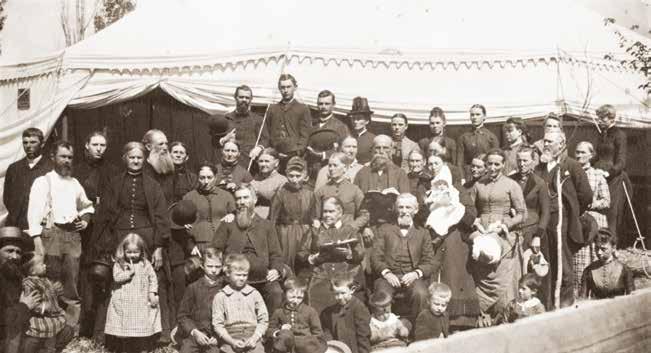

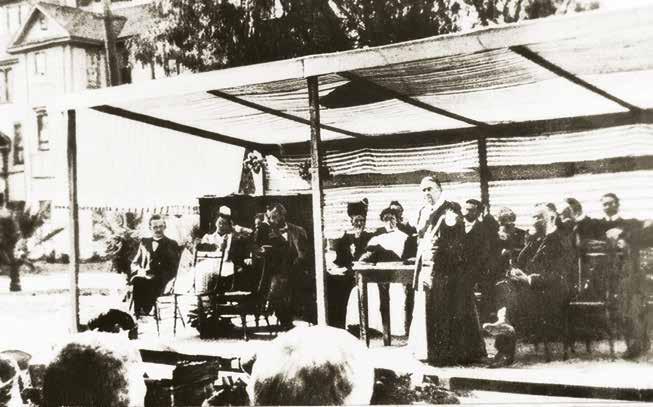

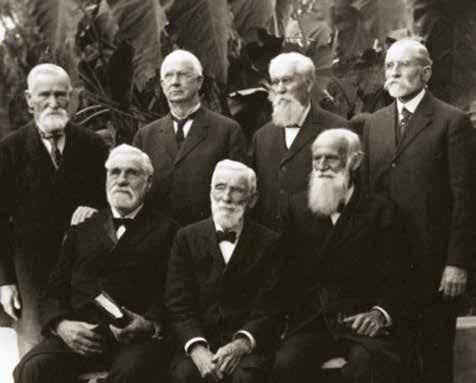

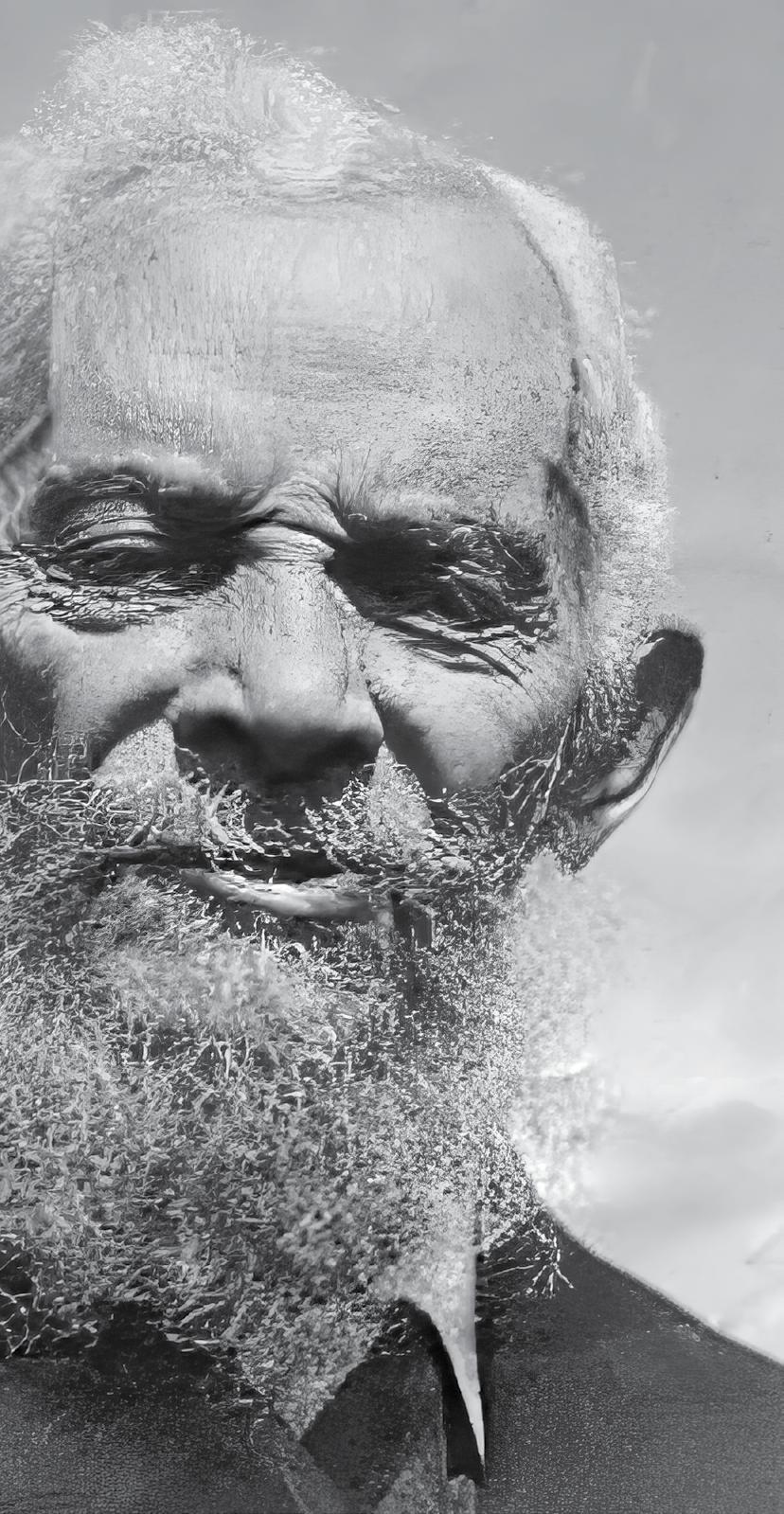

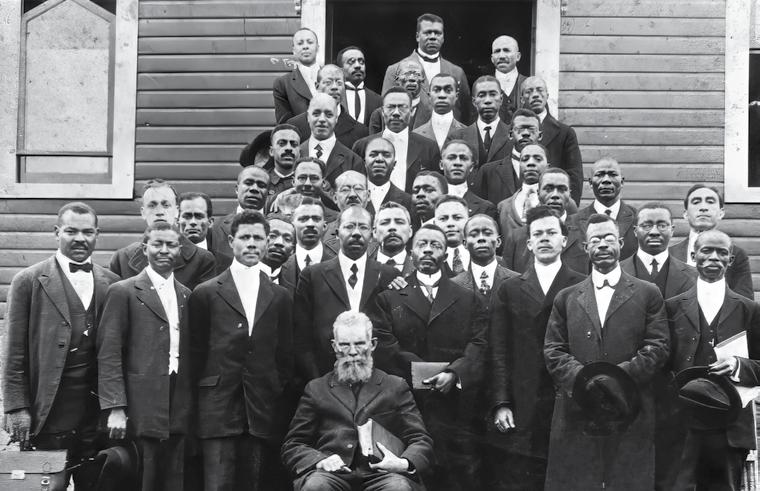

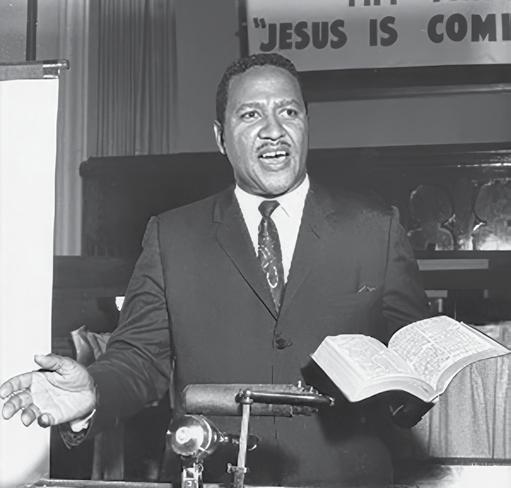

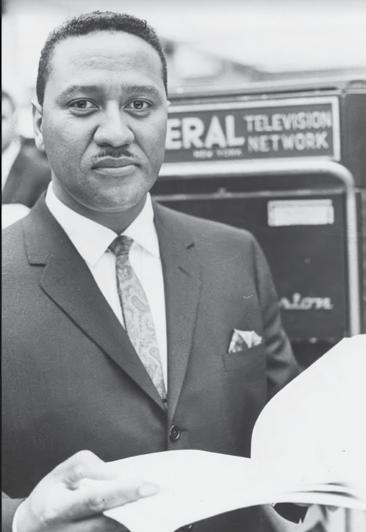

Rodgers in front row with Black delegates and guests at the 1926 General Conference Session, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

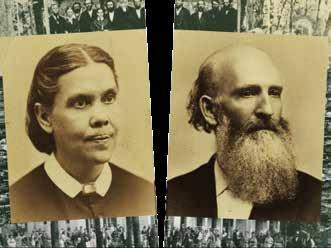

Dr. H. Claude Hudson, president of the Los Angeles chapter of the NAACP, and Charlotta A. Bass, publisher of the California Eagle, Southern California’s leading Black newspaper, were among the guest speakers at Wadsworth Seventh-day Adventist Church in Los Angeles on Jan. 7, 1931. They were there both to celebrate the 25th wedding anniversary of the church’s pastor, P.G. Rodgers, and his wife, Alverta Durham Rodgers, and “to congratulate the church on the rapid strides it has made under the leadership of Elder Rodgers.”1

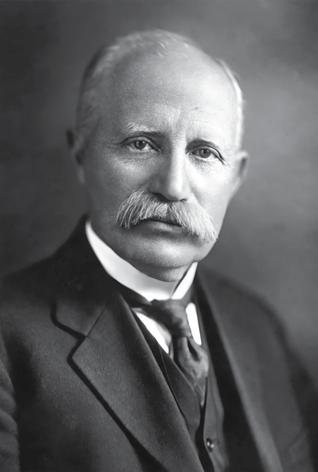

The presence of these community leaders, reported on the front page of the Eagle, is one marker of the impact made by Rodgers’ ministry. In Los Angeles, and before that in Baltimore and Washington, DC, Peter Gustavus Rodgers (1885-1961) proved to be one of Adventism’s

most effective spokespersons in America’s Black urban communities during the first four decades of the 20th century. He was likewise a leading voice in the struggle for Black equality within the church.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on Aug. 10, 1885, Gustavus Rodgers was the sole convert resulting from evangelistic meetings conducted by Fred H. Seeney in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1908. Gustavus and Alverta, married in 1906, both had roots in the Delaware-based people of ambiguous racial heritage known as the Moors.2 The couple’s light complexions sometimes confused people. When, for example, they arrived in Los Angeles in 1923, their congregants reacted with surprise, thinking that the conference had sent a White man to be their minister.3 Yet there was nothing ambiguous about their identity as Black or about their dedication to racial advancement.

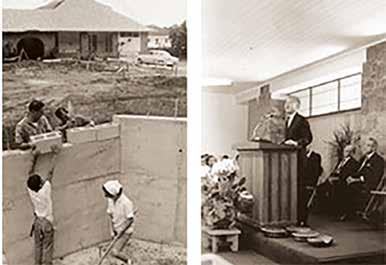

A carpenter by training, Rodgers quickly demonstrated exceptional gifts for ministry and was hired by the Chesapeake Conference in 1910 and assigned to Baltimore in late 1911. He arrived to a congregation of 11, their building “in a half-wrecked condition.” When his pastorate at Baltimore Third church (later named Berea Temple) concluded six years later, the membership had grown from 11 to 300, a church building had been acquired and renovated with over 75% of the mortgage paid, and a thriving church school had been established.4 It

was the beginning of a pattern.

At the Ephesus church in Washington, DC, Rodgers’ next assignment, he again placed a high priority on the quality of the house of worship as foundational to evangelism. After a major renovation completed in 1919, Rodgers claimed that the Ephesus structure now ranked “among the most modern and beautiful of our houses of worship.”5

At the outset of his ministry in Washington, DC, Rodgers used a special lecture he had originated in Baltimore to show that he and the movement he represented had something of importance to say about the dilemmas specific to the African American experience. He spoke on “The Black Man as God Sees Him, or the Inspired History of the Negro” at Black America’s leading cultural and intellectual forum, the

Bethel Literary and Historical Society, on Nov. 26, 1918. W.E.B. Du Bois and A. Philip Randolph were among the other lecturers during the society’s 19181919 season.

Such presentations helped stir interest in Rodgers’ expositions on the Bible delivered at the “Big Gospel Tent” on Sherman Avenue during the summers of 1918, 1919, and 1920. Rodgers baptized more than 200 new believers while at Ephesus, including three noteworthy individuals, all baptized on Dec. 5, 1920: Willie Anna Dodson, on her way to a pathbreaking career as a public school administrator; her husband, Joseph T. Dodson, an entrepreneur with an intellectual bent; and Eva Beatrice Dykes, about to become the first African American female to complete Ph.D. requirements. All three would become part of the lay committee that spearheaded denomination-wide change in race relations during the 1940s, a story told in the book Change Agents, published by Oak & Acorn in 2020.6

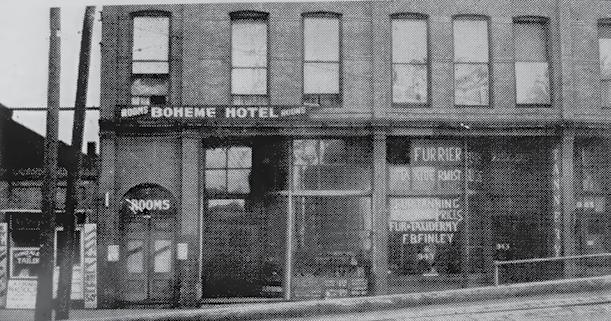

In 1923, Rodgers was called to pastor the East

36th Street church in Los Angeles. Organized in 1908 with the name Furlong Tract, it was the first Black Adventist church on the West Coast. Several of the young people who came of age in this fellowship would make notable contributions in both church and society. These included evangelist and church leader Owen A. Troy, pioneering public health advocate Ruth J. Temple, and educator and author Arna Bontemps, prominent in the Harlem Renaissance. When the congregation moved to a new building on East 36th Street in 1922, it had a relatively strong membership of 99. But that was about the same as it had been a decade before. Adventism still was barely touching the booming Black population of Los Angeles.

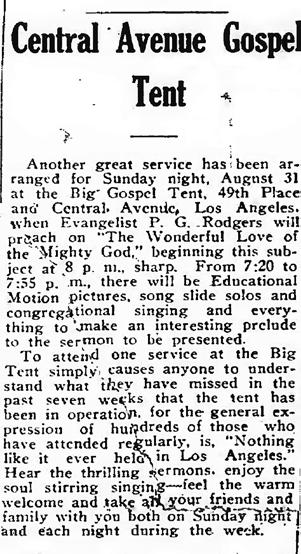

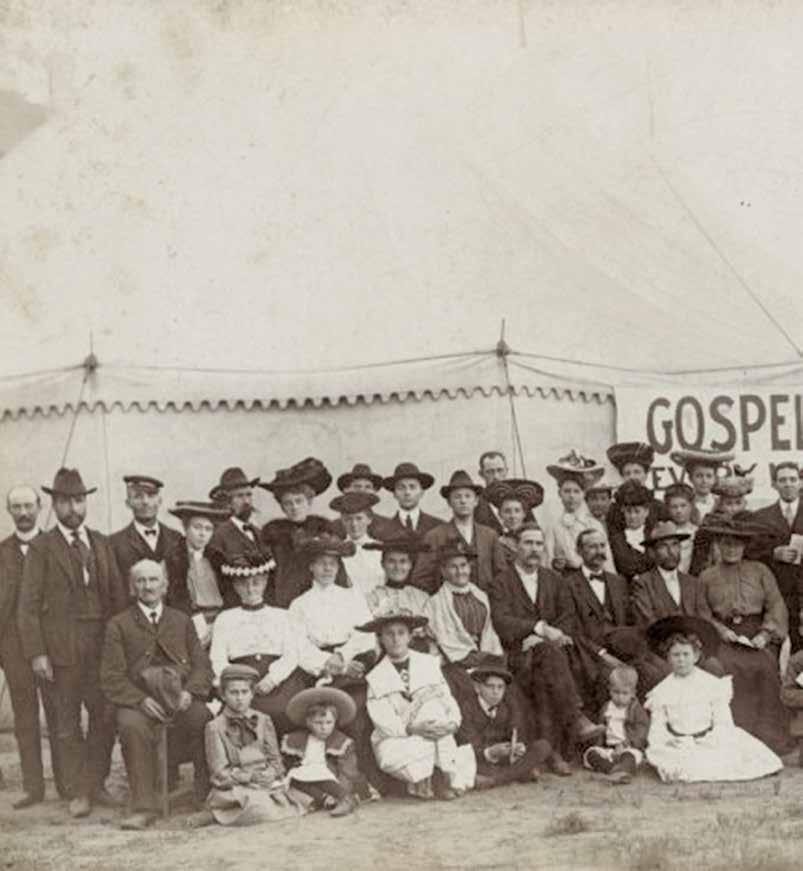

In the summer of 1924, Rodgers set up the 1,000-seat Big Gospel Tent on Central Avenue in the heart of the Black community for three months of evangelistic meetings. This would become an annual, summer-long happening for most of the next 15 years. The 1924 campaign drew nearcapacity crowds on Sunday nights and 400 to 600 on weeknights, including sizable contingents of White people. The church membership doubled to 200 as a result, making it clear already that a larger church building would be necessary.7

The California Eagle described the new 800-seat church, completed in the summer of 1927 on the corner of 35th Street and Wadsworth Avenue, as “one of the finest churches in the city.” With music also a top priority, a “beautiful alcove” behind the pulpit accommodated a Moller pipe organ along with the

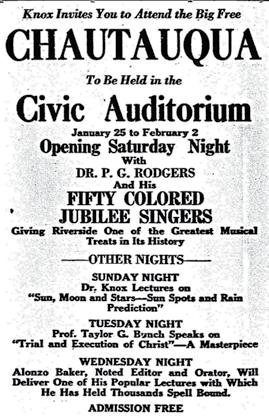

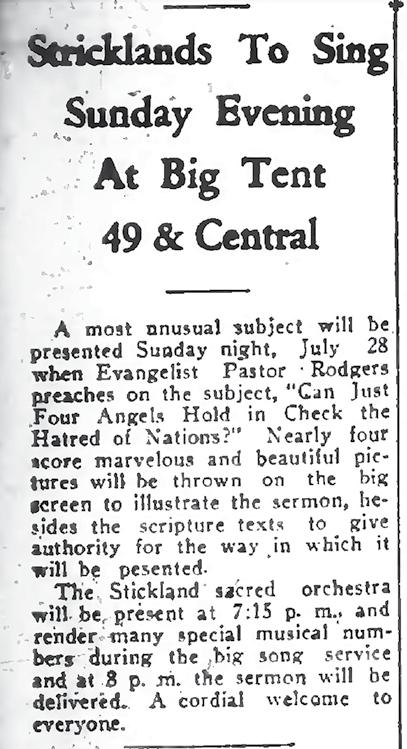

church’s large choir that, according to the Eagle, was “known far and wide in the city for the artistic nature of its work.”8 Rodgers, along with other church members, joined in the construction work to help keep costs down. Less than two years later, on March 2, 1929, the 300-member church held a “noteburning service” to celebrate final payment on the debt. Rodgers honed his method of drawing crowds with “thrilling sermons” that framed Adventism’s end-time warning message in issues of current public interest. In July 1936, for example, with European dictators stirring widespread anxieties about another world war and Italian aggression in Ethiopia arousing particular concern among African Americans, a large headline in the California Eagle announced, “Elder Rogers to Discuss Ethiopian Situation.” That discussion apparently was to be part of a broader presentation under the title announced for the July 28 meeting, “Can Just Four Angels Hold in Check the Hatred of the Nations?” Rodgers now made heavy use of slides, and for this topic he promised that close to “four score marvelous and beautiful pictures will be thrown on the big screen.”9 Rodgers’ ministry was not restricted to the Black

community. He served on the Southern California Conference Executive Committee from 1927-1937 and was frequently a featured speaker at camp meetings and other conference-wide gatherings. He also lent his preaching and the music of his renowned choir, for which he selected the name Jubilee Singers, in support of the efforts of leading White evangelists, such as H.M.S. Richards Sr. and Philip Knox.

As he had been in Baltimore and in Washington, DC, Rodgers was a relentless and passionate activist for equal opportunity in Christian education in Southern California. Though delayed by the Great Depression, a major advance took place in 1936 when the Wadsworth School opened with 68 students in eight grades. Two years later, it had become a junior academy with an enrollment of 112.

In 1938, restrictions on placement opportunities for Black interns by the College of Medical Evangelists (CME) in nearby Loma Linda drew vigorous protest from Rodgers. The preacher thought he had mediated a solution that satisfied both the NAACP and the General Conference administration, but he was outraged when the CME board voted a change to the wording of the policy in a way that, he contended, changed nothing in actuality. He warned that the NAACP would not let the matter go and declared that the only reason he

could imagine for such a “regrettable action” was that “the spirit of a doomed world is getting into the hearts of the leaders of Israel.” Rodgers urged a change so that nothing would be done to cause Black Adventists “to wonder if the entire set-up of pretended interest in them is not one grand colossal mockery.”10

Rodgers’ outspokenness on racial matters apparently made some church leaders feel uneasy about his loyalty to denominational organization. In fact, his very success as a pastor-evangelist made him suspect in an era when three of his contemporaries who were likewise effective became alienated from the denomination over racial issues: Lewis C. Sheafe (1916), John W. Manns (1916), and James K. Humphrey (1930). As one General Conference administrator put it, the basic concern about Rodgers was that “he was a man who has drawn very strongly to himself.” 11 In other words, he was perceived as exerting too much personal influence over his large congregation.

In 1940, his pastorate in Los Angeles having extended to an unheard-of length of 17 years, the pressure grew on Rodgers to accept a call elsewhere. He resisted doing so in part because his wife, Alverta, suffered from a respiratory condition that the Southern California climate

made more tolerable. Additionally, the 55-yearold preacher was beginning to show signs of serious health difficulties of his own. In the end, it seemed that the best solution was for Rodgers to accept a leave from full-time ministry due to disability.

Alverta’s health worsened in 1941 due to “heart trouble,” and she died on June 16, 1942. Though her role went almost completely unmentioned in public reports, she had been an active and indispensable partner in her husband’s ministry from the beginning more than 30 years before.

P.G. Rodgers never returned to full-time ministry, though he did preach occasionally until 1959, when he put up for sale his collection of “3,000 color stereopticon slides,” along with a “Bausch and Lomb dissolving lens machine” that he had used in leading 1,008 individuals to baptism during his time in California.12 Despite his persistent agitation against racial injustice in the church and the disappointment surrounding his early retirement, Rodgers testified in 1960, “I have loved every phase of the Message during these years and have never doubted one line of it.”13 He died in La Mesa, California, on Sept. 24, 1961, at age 76.

P. Gustavus Rodgers was both a powerful evangelist and a personable congregation-builder, a visionary promoter and a pragmatic leader skilled in bringing dreams to reality, unreserved in his dedication to the mission of the church and unrelenting in urging it toward a more Christ-like pattern of race relations.

Adapted by permission from the Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, encyclopedia.adventist.org. For full documentation and a more detailed treatment of Rodgers’ career, see “Rodgers, Peter Gustavus (1885–1961),” Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, https://bit.ly/47de92v

1“Seventh Day Adventist Church Fetes Pastor and Wife on the Occasion of the Couple’s Silver Wedding Anniversary,” California Eagle, Jan. 9, 1931.

2C.A. Weslager, Delaware’s Forgotten Folk: The Story of the Moors and the Nanticokes (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1943).

3Louis B. Reynolds, We Have Tomorrow: The Story of American Seventh-day Adventists with an African Heritage (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1984), p. 177.

4Gustavus P. Rodgers, “The Work Among the Colored People in the Chesapeake Conference,” Review and Herald, Feb. 21, 1918, p. 17.

5Gustavus P. Rodgers, “Work for Colored Believers in Washington, DC,” Review and Herald, July 17, 1919, p. 24.

6Douglas Morgan, Change Agents: The Lay Movement that Challenged the System and Turned Adventism Toward Racial Justice (Westlake Village, CA: Oak & Acorn Publishing, 2020).

7Mrs. A.H. Baker, “East Thirty-Sixth Street Church,” Pacific Union Recorder, Sept. 11, 1924, p. 3.

8“Seventh Day Adventist Church Fetes Pastor and Wife,” pp. 1, 3.

9“Elder Rogers to Discuss Ethiopian Situation,” California Eagle, July 18, 1936, p. 10.

10P.G. Rodgers to W.E. Nelson, Jan. 6, 1939, General Conference Archives, RG 11, Box 3957.

11H.T. Elliott to W.G. Turner, June 9, 1040, GCA, Sustentation Files, RG 33, Box 9774, P. Gustavus Rodgers.

12Advertisements, Pacific Union Recorder, July 27, 1959, p. 14.

13P.G. Rodgers to R.H. Adair, Feb. 5, 1960, P. Gustavus Rodgers Sustentation File, GCA.

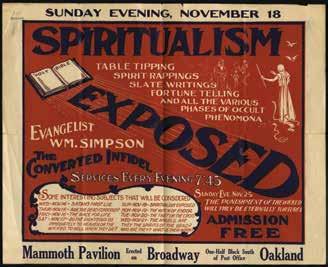

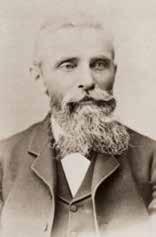

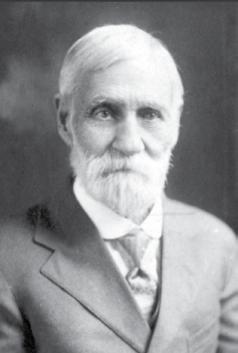

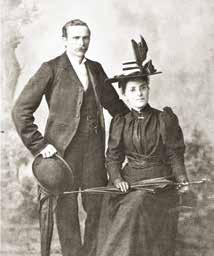

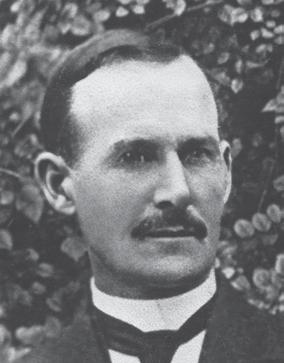

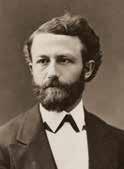

William Ward Simpson was born in Brooklyn, New York, on August 1, 1872, to English parents. The family moved back to England shortly afterwards and then returned to the U.S. when he was 11. His father died soon after the voyage.

When William fell ill, his mother was advised to take him to Battle Creek. Though from an atheist family, William accepted the Adventist message at 18 and began work in the Sanitarium and later at the Review and Herald.

One day, as he operated one of the printing machines, he announced to his foreman that he was leaving “to preach the third angel’s message.” Soon after he was given a ministerial license, and he worked both in Michigan and in Ontario, Canada, which came under the Michigan Conference at that time.

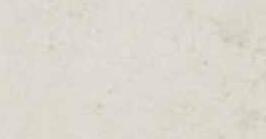

He organized a church in Kent County, Ontario, but while there he was imprisoned for 40 days for the crime of “desecrating the Sabbath” under the local Sunday laws. While in prison he wrote poetry and sent letters, one of which records his experience and was printed in the Review and Herald: “My cell is so small I have hardly room to undress. I am locked in at six o’clock, and let out at seven next

morning, so you see that the most of my time is spent there. I am not lonely; for the most precious experiences of my life have been while locked in my cell. Instead of being shut in by bare walls, it seems like being shut in with Jesus.”1 He later used

this experience in some of his handbills advertising his evangelistic meetings.

In 1897 he and another licensed minister began a church among the Iroquois in a reservation near Brantford, Ontario—the first Native American church in North America.

In 1899 he married Nellie Ballenger, daughter of Adventist pioneer John Fox Ballenger, having first met the family in 1894.

Moving to California in 1902, he developed his evangelistic strategies and held meetings in Redlands, Riverside, Pasadena, San Diego, San Francisco, and Oakland.

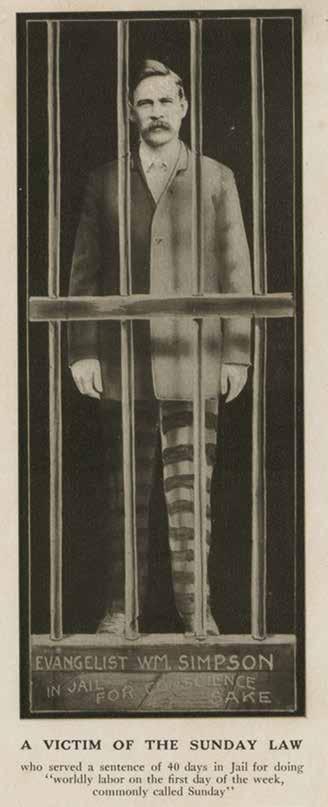

But his greatest work was reserved for the city of Los Angeles. Beginning in 1904, he held public meetings in the downtown area and attracted thousands.

Using graphic illustrations and clear expositions of Bible truth, he convinced many of the Advent message. After the first set of meetings, over 200 were baptized. When it was thought he would finish, a petition was circulated by the local people, urging more meetings.

When the conference did suggest a move, Ellen White opposed it. She took a great interest in Simpson’s work, writing to him several times. However, she was concerned about burn-out, telling him, “I am deeply interested in your work in Southern California. I am so anxious that you shall not break down under the strain of long, continuous effort. Let someone connect with you who can share your burdens. This is the plan that was followed by the Great Teacher. He sent His disciples out two and two.”2

She also spoke very favorably about his methods: “Brother S is an intelligent evangelist. He speaks with the simplicity of a child. Never does he bring any slur into his discourses. He preaches directly from the Word, letting the Word speak to all classes. His strong arguments are the words of the Old and the New Testaments. He does not seek for words that would merely impress the people

with his learning, but he endeavors to let the Word of God speak to them directly in clear, distinct utterance. If any refuse to accept the message, they must reject the Word.”3

She praised his ingenuity: “I am pleased with the manner in which our brother [Elder S] has used his ingenuity and tact in providing suitable illustrations for the subjects presented—representations that have a convincing power. Such methods will be used more and more in this closing work.”4

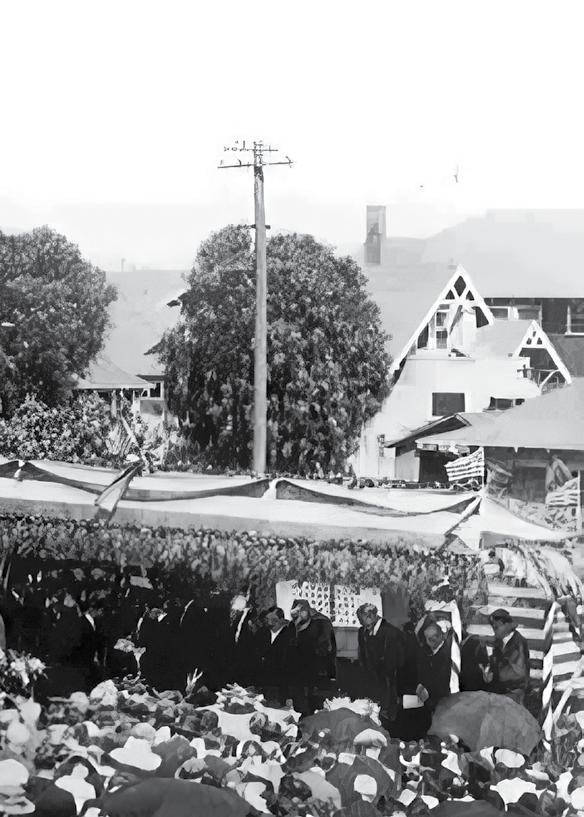

So it was all the more tragic that he died so early, at the age of 34 in 1907, leaving behind his wife and three young children. Ellen writes of her sadness: “While we were at Loma Linda, we were made sad to hear of the death of Elder W.W. Simpson. Brother Simpson was a man who thoroughly believed the message for this time, and he preached it with power. His winning way of

presenting Bible doctrines, and his ability to devise and to use suitable illustrations, enabled him to hold the close attention of large congregations. He had confidence in the power of the word of God to bring conviction, and the Lord greatly blessed his efforts in the salvation of many souls.”5

Ministerial colleague Roderick S. Owen conducted Simpson’s funeral and wrote, “The service, conducted in the Central church in Los Angeles, was attended by a large concourse of people.... He was buried in the new cemetery at Tropico, Cal., where he will sleep in Jesus until the voice of his Master calls him forth to behold, in wonder and rapture, the scene of Christ's return to earth, which scene he has so often and so vividly portrayed before his audiences.”6

Even so, come, Lord Jesus.

1. William Simpson, “From Chatham Jail,” Review and Herald, May 26, 1896, p. 333.

2. Ellen G. White, “Proper Voice Culture,” Manuscript Releases, vol. 9 (Silver Spring, MD: Ellen G. White Estate, 1990), p. 15.

3. Ellen G. White, Evangelism (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1946), p. 204.

4. Ellen G. White, Evangelism, p. 205.

5. Ellen G. White, “Notes of Travel—No. 2,” Review and Herald, Aug. 1, 1907, p. 8.

6. Roderick S. Owen, Review and Herald, May 23, 1907, p. 23.

The beginnings of Adventist work in Arizona are a little hazy. Certainly there were Adventists in Arizona by the 1880s—there is an entry in the Seventh-day Adventist Yearbook for 1884, but with no details. A.J. Potts indicates that the Phoenix church began in 1887 and that it was organized in 1890. In 1889, the California Conference took the responsibility for the largely un-entered territories of Utah and Arizona.

At the 1891 General Conference Session, R.A. Underwood reported, “Since the last General Conference, the California Conference has opened the work in Utah and Arizona. At Phoenix, Ariz., a church has been organized with eighteen members, and a good work started.”1 In 1895, Arizona was taken over as a General Conference mission, but in 1901 it was added to the territory of the newly created Pacific Union Conference.

One of the early pioneers, George States, wrote in the Review and Herald,

The work in this territory moves slowly, and at times looks discouraging. About the first of October [1898] I began holding Bible readings in Phoenix. I continued this work, assisting some on the church building from that date until January 15. As a result, I had the joy of baptizing two souls, and seeing them unite with the Phoenix church.

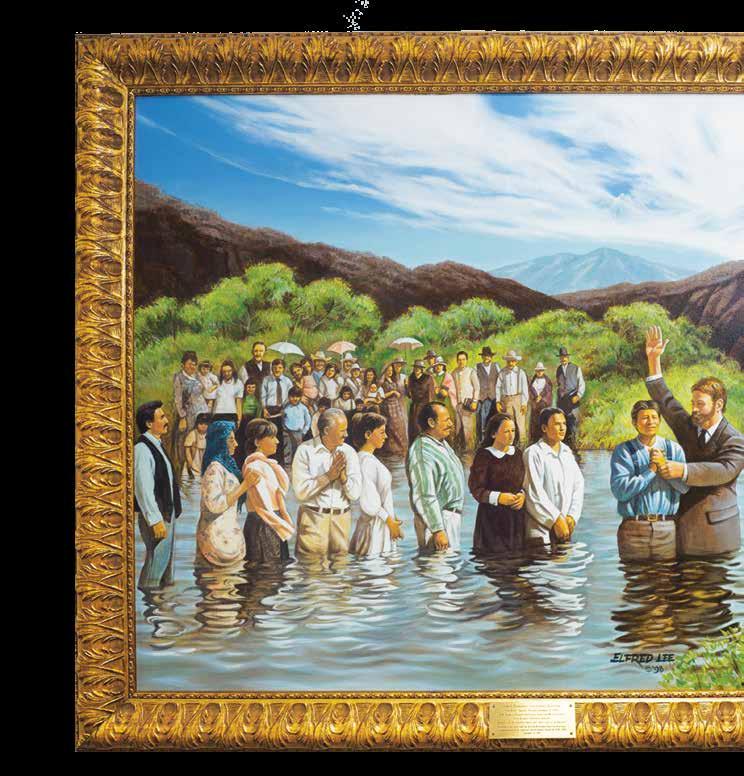

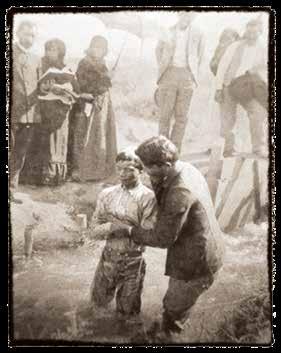

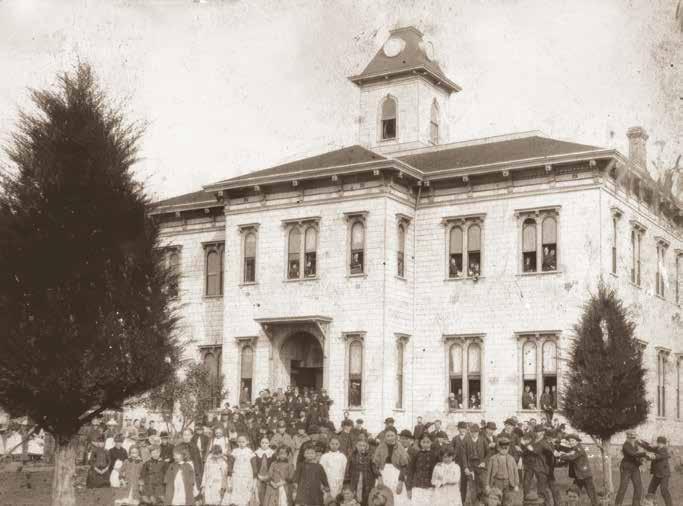

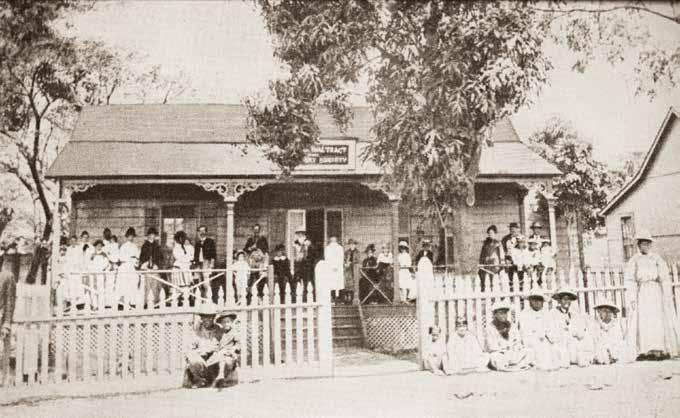

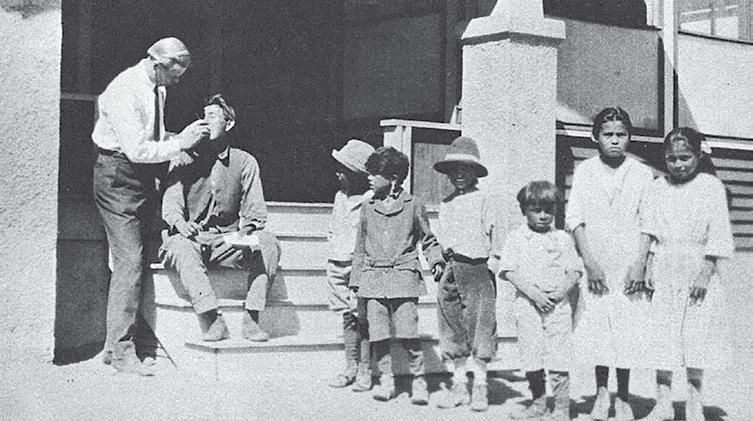

This original painting commemorates the first Hispanic Adventist baptism. It occurred on Dec. 9, 1899, in the Gila River at Sanchez, Arizona. Marcial Serna, formerly pastor of the Tucson Mexican Methodist-Episcopal Church, had accepted the message shared with him by Adventist literature evangelists. Included in the group of 15 baptismal candidates were Abel and Adiel Sánchez, along with several of their children. On Dec. 23, the church in Sánchez, Arizona, was officially organized, becoming the first Spanish Seventh-day Adventist church in North America.

January 15 I bade good-by to a large number of our brethren and sisters, and came to my new field at Flagstaff, nearly three hundred miles distant. As far as I know, there are none of our people within one hundred miles of us. It was quite a change to leave the warm climate of Phoenix and go to a place where the ground was covered with snow at an altitude of about seven thousand feet. I began at once to visit from house to house, leaving tracts, and taking orders for “Steps to Christ.” I have been over about two thirds of the place, have distributed several thousand pages of tracts, and expect to put at least seventy-five more copies of that valuable book into the homes of the people. I am giving some Bible readings, and a few seem interested. My wife and daughter are with me, and we hope soon to have others unite with us in our little Sabbath-school.2

The challenges of spreading the word are illustrated by some of States’ experiences. He went by bicycle through the Verde Valley, where he

gave out tracts and visited people from previous meetings. While he was traveling through Peeples Valley with a tent and equipment, his wagon broke down, forcing long treks to find water. He had convinced a number of people of the truth, but when he returned 30 months later, only one family was left. There had been a drought and, due to the nature of the environment, the population was very transient. In addition, religious ideas seemed to many to be a luxury as they struggled to survive. A common saying among those who came west seeking gold was that they left their religion behind at the Missouri River.

Illustrating the diverse nature of the West, it’s fascinating to learn that the first people among the Hispanic community to become Adventists in the United States lived in Arizona.

In 1899, literature evangelists Walter Black and Charles Williams contacted a Methodist minister, Marcial Serna, from Tucson. Following a public debate, Serna accepted the Sabbath, and he then shared this truth with his members, many of whom also became Adventists. The first Spanish church was in Sanchez, Arizona, with 15 members attending. Marcial Serna himself became the first Hispanic pastor in the Adventist Church.

In 1901, R.M. Kilgore reported to the General Conference:

In this mission field we have four organized churches, three of which have been developed since last General Conference. They are provided with a neat and comfortable meeting-house at each point (total value, $3,700), and so nearly paid for

that they are practically out of debt. Two of these are Spanish-speaking churches, a few Americans being connected at Tucson. In the territory there are 111 members and 17 isolated Sabbath-keepers. Tithes paid to General Conference in 1900 were $459,— $4.13 per capita. Amount paid to the Foreign Mission Board, $59.90; book sales for six months, $107.50.3

It’s interesting to note that the initial Tucson church membership was made up of 13 Spanish speakers, nine English speakers (including four workers), and one Chinese speaker. The church at Solomonville was made up entirely of Spanishspeaking members. By the end of 1901, the mission had one ordained minister, three licensed ministers, two Bible instructors, one literature evangelist, and one church school teacher. In 1901, Arizona became a mission of the Pacific Union Conference, newly established in a global reorganization of the Adventist Church’s administrative structure intended to allow local leadership greater say in directing the Church’s work. This change led directly to significant evangelistic progress in various areas, including the Pacific Southwest. General Conference

president A.G. Daniells commended the new union conference for taking immediate action to send workers to Arizona to develop the Church’s program there:

Perhaps no Conference in the States has done more thorough work in organizing than has the Pacific Union Conference. It has added to what was District 6, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii. The new administration began July 1, 1901. Without delay, laborers were sent to Arizona, Alaska, and Honolulu.4

The Arizona Conference was organized in 1902. It had four churches—Flagstaff, Phoenix, Solomonville, and Tucson—along with a company at Bisbee, altogether comprising 128 members, with one ordained and three licensed ministers. E.W. Webster, who had been superintendent of the mission, continued as president of the conference. The Arizona Conference was formally admitted to the Pacific Union Conference on March 18, 1904.

1General Conference Daily Bulletin, vol. 4, March 8, 1891, p. 25.

2George O. States, “Arizona,” Review and Herald, Feb. 14, 1899, p. 109.

3General Conference Bulletin, vol. 4, April 4, 1901, p. 60.

4A.G. Daniells, “A Brief Glance at the Work of Re-organization,” General Conference Bulletin, July 1, 1901, p. 514.

The adobe Sanchez church became the first Spanish-speaking Adventist church in North America on Dec. 23, 1899.

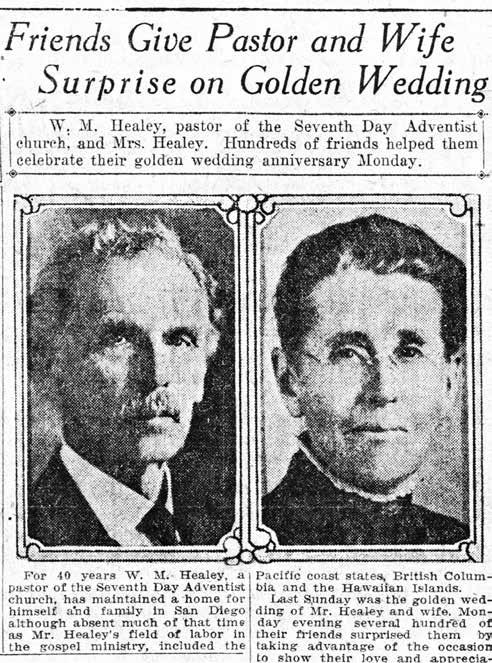

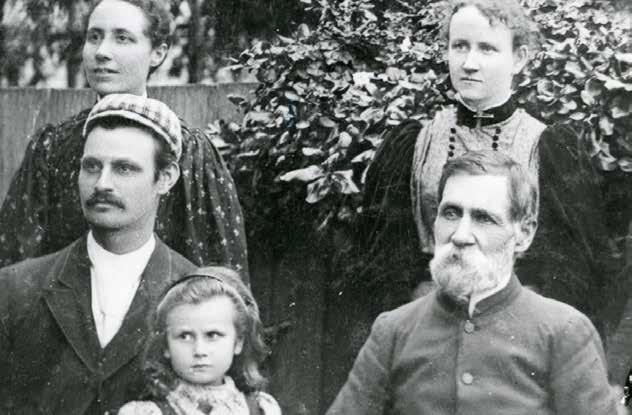

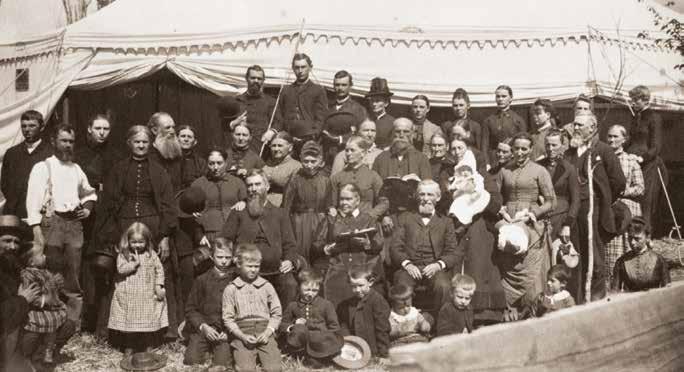

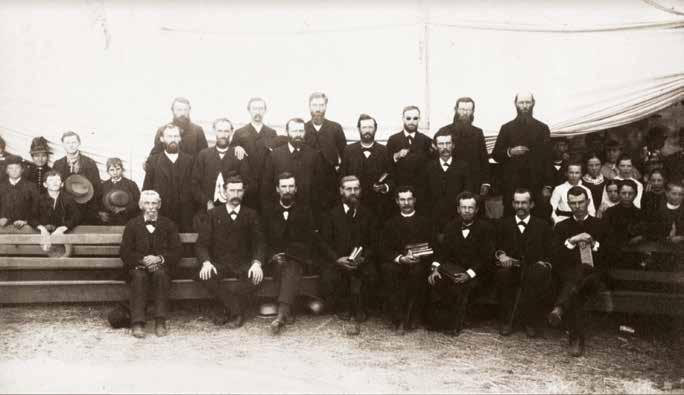

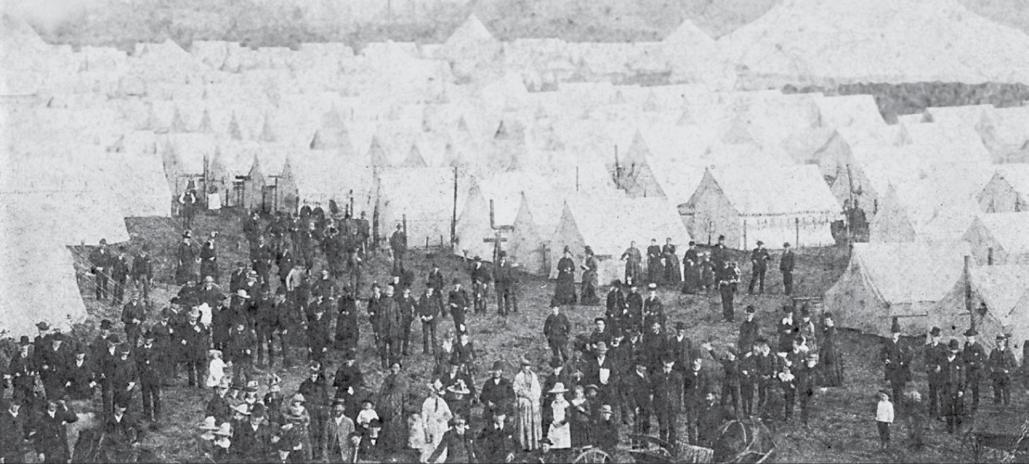

Photograph of the first evangelistic meeting held in Hawaii from January through March 1886. From left to right: Birdie Healey, William Healey, Clara Healey, Loran A. Scott, and Abram La Rue.

The Hawaiian Islands were formerly known as the Sandwich Islands. Visited by Captain James Cook in 1778, he named them after John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. The name Hawaii came into use later. Ellen White still referred to them as the Sandwich Islands in 1892.

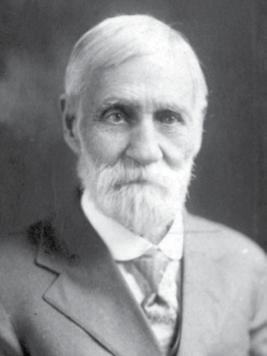

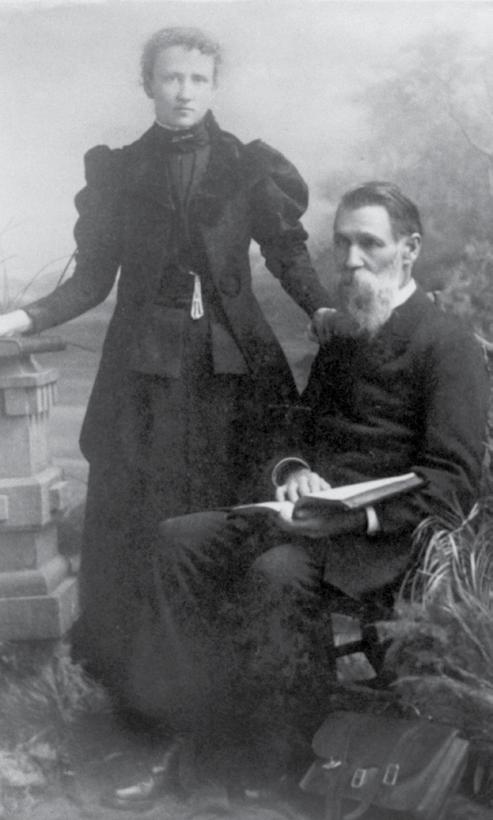

Adventist work in Hawaii began in 1884 when Abram La Rue and Henry Scott went at their own expense to do missionary work and sell books. Pioneer and historian John Loughborough records: “This awakened such an interest on the island that the General Conference, in November, 1885, voted that Elder Wm. Healy go the next season to Hawaii to labor, and that the California Conference be requested to loan a tent for this purpose. Thus equipped Elder Healy and those already on the island conducted a tent-meeting during the summer of 1886. As the result of this effort a number of persons accepted the message. Mr. La Rue remained in Honolulu till the year 1889, when he set sail for Hong Kong, China.”1

W.M. Healey arrived in Honolulu on Dec. 27, 1885, with his wife and 10-year-old daughter. To save money, they had traveled steerage class (no cabin) for $25 each. He began evangelistic meetings on Jan. 15, 1886, in a 50-foot tent pitched on the corner of Vineyard and Fort streets. The meetings were attended by the many interested people gathered by the two literature evangelists. Healey left Honolulu

four months later, having baptized nine.

A.J. Cudney followed Healey to Honolulu, and on July 22, 1888, he organized the nine charter members as the first Adventist church in Hawaii.

However, this was not reported to the General Conference because nine days later he set sail for Pitcairn Island—and he and his ship never arrived, all being lost at sea. Consequently, the church was not recognized until its reorganization in 1896.

Writing from England in 1896, E.J. Waggoner provided the following information: “A report from the Hawaiian Islands says that our friends in Honolulu are just starting a sanatorium, with a medical missionary in charge. The Chinese work in the islands is prospering, and some natives

connected with the mission are expecting soon to return to China to work.”2

Three years later, Baxter L. Howe also gave an enthusiastic report that, aside from the glowing language, also shows the potential among such a diverse population:

“There is hardly any nationality that is not represented in the Hawaiian Islands. These are constantly coming and going from all parts of the world. As they stop there, we have the opportunity of simply meeting them, and then they pass on.

“But there are many with whom we have more than this passing contact. Perhaps you know that we have a Chinese school established on the island of Oahu, also one in Hilo, and that we are endeavoring to do what we can for those people whom God has permitted to be there in such large numbers.…

“If there is one thing in all the islands of Hawaii that touches my heart more than others, it is the condition of the poor native people. The gospel has been brought to them. Some have accepted it with all their great, free, loving nature. But what was given them was not the true gospel of Jesus Christ.… They fear God, and worship idols.…

“Now I say that we must have something for these people, something that we can take to them, and that they can comprehend, that will lead them step by step out of this condition into the glorious light of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

“Our work among the English-speaking people has been most encouraging to us. It has not shown very largely in reports; but I want to say that there is an open door in the homes of the English-

“There is hardly any nationality that is not represented in the Hawaiian Islands. These are constantly coming and going from all parts of the world.” -Baxter L. Howe

speaking people in the islands of Hawaii to-day.”3

It was the newly formed Pacific Union Conference that, once it was formed, immediately sent workers to Hawaii (as well as to Arizona and Alaska).4

In 1903, the report was of 37 members among a population of 154,000, made up of native Hawaiians, Americans, Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese.5

On her way to Australia in 1891, Ellen White’s ship stopped in Honolulu for 19 hours. She wrote extensively of her experience in the Review and Herald. The article began, “One week from the time we left California we reached the Sandwich Islands. The scene presented to us from the steamer as we approached Honolulu, was very beautiful… Our steamer was not to leave Honolulu till past midnight, and at the earnest desire of our friends I

had consented to speak in the evening. The hall of the Young Men's Christian Association was secured for the purpose. Only a few hours' notice of the meeting could be given, yet a goodly number were assembled, among them many who were actively interested in temperance and Christian work. I spoke from 1 John 3:1-4, dwelling upon the great love of God to man, expressed in the gift of Jesus that we might become children of God. The Spirit of the Lord was present with us.”6

On her return from Australia, she also stopped in Honolulu on Sept. 14, 1900. She recorded her visit: “About eight o'clock this morning we steamed into the harbor. Elder Baxter Howe was at the wharf to meet us, and gave us a hearty welcome. He took us in a carriage to Sister Kerr's, where we were most heartily welcomed, and where we sat down to a bountiful meal, which we all greatly enjoyed.

“In the afternoon we visited the sanitarium, and were very much pleased with the location. Then we met with a large number of our people at the church, where I spoke for about forty minutes and Willie for about thirty minutes. It was a great privilege to meet with these brethren and sisters, and we wished that we could spend two or three weeks with them. But this would be impossible.

“At the close of the meeting we visited the Chinese school.… We see a large field of work for this school, which should be more fully developed. Thus missionaries can be prepared to go to China and labor for their countrymen.”7

1J.N. Loughborough, The Great Second Advent Movement (Washington, DC: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1905), p. 440.

2E. J. Waggoner, “Back Page,” The Present Truth, Aug. 27, 1896, p. 560.

3“The Hawaiian Mission Field,” General Conference Bulletin, vol. 4, April 16, 1901, pp. 279-280.

4“The Pacific Union Conference,” General Conference Bulletin, vol. 4, July 1, 1901, p. 514.

5“Report of the President, W.T. Knox,” General Conference Bulletin, vol. 5, April 2, 1903, p. 49.

6Ellen G. White, “On the Way to Australia: Visit to Honolulu,” Review and Herald, Feb. 9, 1892, p. 81.

7Ellen G. White, “Reflections While Crossing the Pacific,” Manuscript Releases, no.1427, Sept. 14, 1900, pp. 33-34.

RIGHT: Missionaries Arthur and Carrie Hickox with daughter Lillian Humberta (on the left) and Dr. Merritt Kellogg and wife Louisa (on the right), after sailing to the South Pacific on “Pitcairn.”

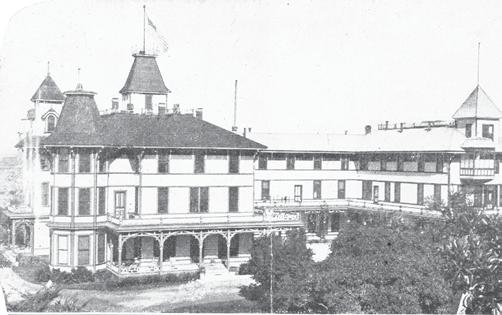

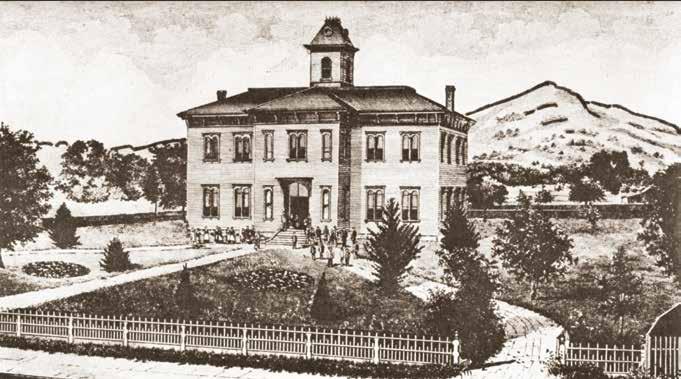

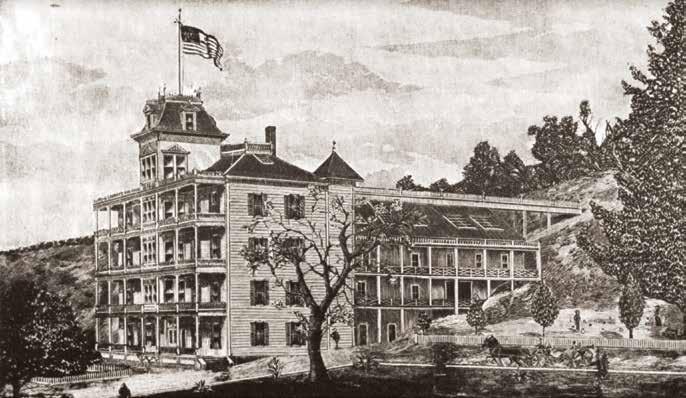

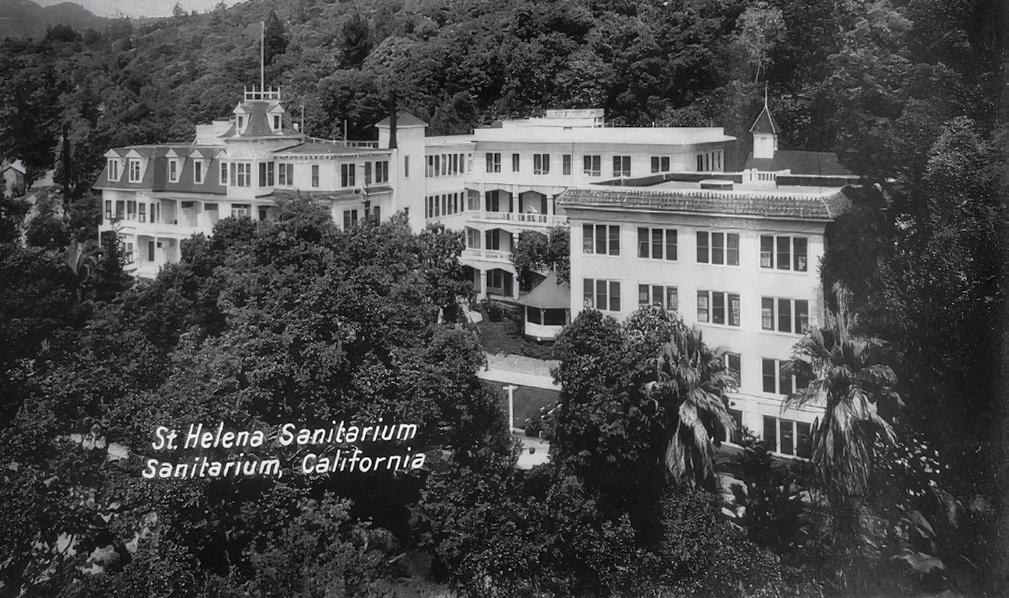

BELOW: Rural Health Retreat, near St. Helena, California, founded in 1878 by Dr. Merritt G. Kellogg.

Central California has the privilege of being the very first place in the West to be touched by the Adventist message. In 1859, when Merritt Kellogg, stepbrother of John Harvey Kellogg, arrived in San Francisco with his wife and family, he was ready to share his faith. His first convert was B.G. St. John, a “forty-niner” (one who had been part of the California gold rush in 1849) who had also been a follower of William Miller in 1844.

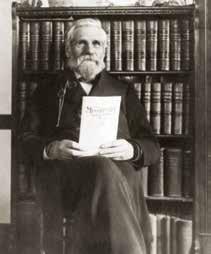

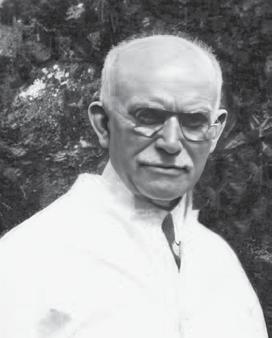

Dr. Merritt G. Kellogg.

By 1861 Merritt Kellogg had collected a group of 14 believers together. In 1864 he was joined by J.W. Cronkite, a shoemaker, who had come from Michigan by ship. He planned to support himself by his trade and do some missionary work by circulating tracts.

On behalf of the group, Kellogg sent a request for a minister to the General Conference, along with $133 in gold. The GC replied that they were not able to send anyone, but they kept the gold. So in 1867

Kellogg went east to plead his case to the GC in person. He didn’t arrive in time for the meeting, so he stayed until the next one—a year later!

In 1868 he was successful in persuading the GC to send evangelists to California, which at that time seemed to be at the ends of the earth. John Loughborough and Daniel Bourdeau took a ship to Panama. Loughbrough dryly observed an incident with some humor: “As we boarded the boat, Elder Bourdeau’s $5 hat got knocked into the water, which he fretted about every day until we reached Panama.” 1

They went overland across the Isthmus of Panama and then took another ship to San Francisco. (The Panama Canal was not finished until 1914.) On arrival they went immediately to B.G. St. John’s house and met the new believers.

They had intended to set up their tent in San Francisco, but they were invited by a group of

In 1868 he was successful in persuading the GC to send evangelists to California, which at that time seemed to be at the ends of the earth.

Independent Christians to come to Petaluma, 50 miles north. So it was not until 1871 that Loughborough began his first public meetings in downtown San Francisco.

Miles Grant, a minister of the Advent Christian Church from New England, had held some meetings in which he was supported by some of the Adventists—including St. John, who had Grant stay in his home. But then Grant left rather abruptly with the recommendation that his followers join the Methodist Church. About 50 did not want to do this and organized themselves into a separate group. St. John sent an urgent message for Loughborough to come, and many of this group went to hear him preach and joined the Adventist church. In total

about 70 new members joined the church in San Francisco.

In 1872 James and Ellen White accepted an invitation to visit California and traveled to Oakland, arriving in September. James White observed, “We like the people of California, and the country.”2

After speaking at camp meetings and other events, and helping with the organization of the California Conference, they headed back to Battle Creek. However, the Whites liked California so much that they were back again in December of the following year.

Loughborough records in 1874 that “Wesley Diggins of San Francisco made an earnest request that the double tent be erected in his city. We secured a lot on Golden Gate Ave., and opened meetings Oct. 16. Elder Butler took part until November 1, when he and Elder Cornell returned to Michigan. Attendance was between 800 and 1,200 nightly.”3

This was also during the time when James and Ellen White were present. Loughborough recalled, “My labors were associated more or less with the Whites until February, when the failing health of my companion called for my attention at home in St. Helena. I spoke to the company there on Sabbaths until she peacefully passed away on March 24. She sleeps quietly in the St. Helena cemetery.” 4 Loughborough’s wife Maggie died at age 35 from tuberculosis.

James and Ellen were convinced to make Oakland the center for the work in California. The forerunner of the Pacific Press was set up there, and Signs of the Times began publishing. In fact, the Whites sold up everything they had in the East to make this investment possible. In 1899, Ellen White wrote, “We went over the same ground in California, selling all our goods to start a printing press on the Pacific Coast. We knew that every foot of ground over which we traveled to establish the work would be at great sacrifice to our own financial interests.”5

The need for a church in San Francisco was obvious, but the congregation had little money.

However, with encouragement, the impossible happened. Loughborough again:

On April 14 [1875], the leading members of the San Francisco church met at the home of Sister J. L. James, and Sister White related to us what had been shown her in vision. She stated that San Francisco would always be a mission field, and urged upon us the importance of erecting a house of worship. It would look to that poor church like a move in the dark, but if they moved out as the providence of God opened the way, the cost would be entirely met. Knowing as I did the financial condition of these members, to build a church 35 x 80, where a lot alone cost $6,000, looked indeed like a “leap in the dark.”

But we found a lot on Laguna Street for $4,000. Then one sister promised $1,000 if she could sell her place, and within two weeks she sold it for $1,000 above the price she had valued it. A brother who could not see how a church could be built said, “If the Lord says it must be done, He will open the way.” Soon he received $20,000 from an estate settlement and gave $1,000. The church was erected for $14,000, including the price of the

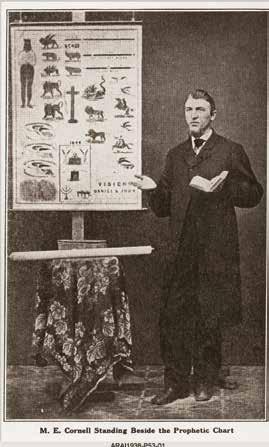

LEFT TO RIGHT: John Loughborough, Daniel Bourdea, and Miles Grant (From F.L. Piper, Life and Labors of Miles Grant [Boston: Advent Christian Publication Society, 1915]. Shared by Douglas Morgan). RIGHT: San Francisco Central Seventh-day Adventist Church, built in 1892, was originally a MethodistEpiscopal church.

lot, over half of which was paid for before it was finished.6

The emphasis was always on mission. In 1876, a Bible institute was held in Oakland. The California Conference provided board and room for the 48 participants, and it was conducted by Uriah Smith and James and Ellen White, showing in a very practical way their commitment to the work in California.

Because of the rapid growth in California, the decision to divide the Conference was taken at the Oakland camp meeting in 1901. Therefore, Southern California Conference was created, being the area of the state south of the Tehachapi and Santa Ynez mountains. In the same year the Pacific Union Conference was formed, with a large territory: Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, Hawaii, British Columbia, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona.

1J.N. Loughborough, Miracles in My Life (Payson, AZ: Leaves-of-Autumn Books, 1987 reprint), p. 69.

2Arthur White, Ellen G. White: The Progressive Years: 1862-1876, vol. 2 (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1986), p. 359.

3Loughborough, Miracles, p. 92.

4Loughborough, Miracles, p. 92.

5Ellen G. White, The Publishing Ministry (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1983), p. 28.

6Loughborough, Miracles, p. 92.

The year was 1869. Evangelists John Loughborough and Daniel Bourdeau had only been in the West for a year. They had started holding tent meetings in northern California—in Petaluma, Santa Rosa, and Healdsburg.

It was in Healdsburg that they received a letter from William Hunt of Gold Hill, Nevada. He’d seen a newspaper report that, though unsympathetic, at least reported what was happening. Hunt didn’t know their names, so he addressed the letter “To the Elders at the Tent in Healdsburg, California.” He had heard they were selling books on Revelation, and he wanted one. Loughborough sent him the book, along with other literature and a letter explaining what they were doing. Hunt replied, sending money and requesting more books. Eventually, Loughborough reported that they had sent him everything the denomination published!

Hunt said he believed it all and was making arrangements to keep Sabbath. He regularly sent money for the books and for tent meeting expenses.

Later Hunt came and met Loughborough, though he was leaving the country en route to New Zealand and then South Africa. In South Africa, he went to the diamond mines in Kimberley and, using the literature he had gathered, introduced the Adventist message there.

Reflecting on the positive experience that came as a result of a critical newspaper report, Loughborough observed, “By this time we knew we need not be alarmed at a little reproach against us.”1

A more permanent Adventist presence began in Nevada in 1876 when Jackson Ferguson, from Santa Rosa, California, began to hold regular Sabbath services. The following year, Loughborough reported that two families from Santa Rosa moved to St. Clair, Churchill County, Nevada. The year after that, they invited Loughborough to come and visit. He records his experience:

I arrived at Wadsworth Station Feb. 1, 1878, and was met by Jackson Ferguson who took me 35 miles across the desert to St. Clair, passing only one residence on the way. St. Clair is on the Carson River about six miles

above the sink, on the edge of the Great American Desert. It is 5 miles from ‘Rag Town,’ were [sic] the immigrants stopped on Carson River for a few days to change their muchworn garments for better clothing before entering the settlements.

During February we held meetings in the Churchill County Institute, the only school building in the county. The whole community turned out and listened with great interest. In addition to those who had moved here from California, eight covenanted to keep all the commandments. When the question arose about my travel expenses and four weeks of labor, a non-member arose and said,

‘The way to raise this is to go down into our pockets and hand out the money.’ Then he laid a $20 gold piece on the desk. Others followed, and in two minutes the sum was more than made up.2

Such generosity was a common feature of the early days in the West.

One of those baptized in Reno was Charles M. Kinny, who had been born a slave in Richmond, Virginia. He had gradually made his way west. It was there in Reno that in 1878 he attended J.N. Loughborough’s evangelistic series.

During these lectures Ellen G. White

“Some of our brethren and sisters in Battle Creek and other favored centers should be working in Nevada.”—Ellen White

visited, and on July 30 she preached to an interested audience. She records that she spoke “in the tent in which Elder Loughborough was giving a course of lectures. I spoke with freedom to about four hundred attentive hearers, on the words of John: ‘Behold, what manner of love the Father hath bestowed upon us, that we should be called the sons of God.’” 3

Her sermon made an impact on Kinny. He became convinced of the Adventist message and was baptized on September 30, 1878.

Significant? Absolutely! Kinny was sponsored by the Reno church to study at Healdsburg College, and he became the first ordained Black pastor in the Adventist Church with an important ministry in various areas in the South.

As a result of these meetings and others in Reno, the “Seventh-day Adventist Association in the State of Nevada” was formed, later becoming the Nevada Mission. Nevada’s first Adventist church was built in Reno in 1888.

That was also the year Ellen White visited again, this time for a camp

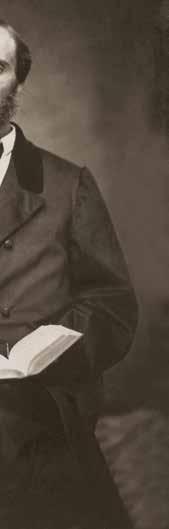

Ella White Robinson, granddaughter of Ellen White, at the age of 92 wrote her memoirs, beginning when she, a child of 3, traveled to Europe with her parents and grandmother.

meeting. We have a record of letters she wrote while on the train. In 1905 she passed through Reno again, this time with an even more personal interest, since her granddaughter, Ella White, was teaching at the school in Reno. With her direct experience of the situation in Nevada, Ellen White made one of her very incisive observations: “Some of our brethren and sisters in Battle Creek and other favored centers should be working in Nevada.”4

Churches were organized at Bishop (1903) and Fallon (1906). A report from A.J. Osborne in 1907 mentions church work at Genoa, Gardnerville, Reno, Verdi, Fallon, and St. Clair. Until 1911 the Nevada churches were under the administration of the California Conference. In 1913, the Nevada Mission was organized. In 1931, the Nevada-Utah Conference was created, with 315 members and 12 churches in Nevada.

1J.N. Loughborough, Miracles in my Life (Payson, AZ: Leaves-of-Autumn Books, 1987 reprint), p. 80.

2Loughborough, Miracles in My Life, p. 94.

3Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 4 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1885), p. 296.

4Ellen G. White, “Notes of Travel—No. 3,” Review and Herald vol. 82, no. 7 (Feb. 16, 1905), p. 8.

Walter T. Knox, president of the California Conference (1897-1900, 1906-1908).

The Santa Rosa church building in 1869, one of the first Adventist churches west of the Rocky Mountains.

A.J. Breed, president of the California Conference (1896-1897).

While it was San Francisco that saw the first presence of Adventists in California, it was within the territory of the Northern California Conference that the real work began.

A group of Independent Christians had seen a newspaper announcement about two Adventist evangelists coming west in 1868. Once John Loughborough and Daniel Bourdeau arrived in San Francisco, this group were able to contact them quickly and invite them north to Petaluma.

Loughborough and Bourdeau had already found that holding meetings in San Francisco was going to be expensive, so they readily accepted the invitation to Petaluma.

Loughborough records the way contact was made:

Mr. Hough, one of the Independents of Petaluma, called at St. Johns and inquired if there were two ministers with a tent staying with him. How did he so quickly find us in a city then numbering 175,000? On his way down he had been impressed to go at once to the Pacific Mail and inquire if a tent had come on the last steamer from Panama. As he asked,

‘Where was the tent?’ the very drayman who had moved the tent, came into the warehouse and directed him to Minna St. So in thirty minutes from the time Mr. Hough landed in San Francisco on the Petaluma steamer, he had found us.1

They left for Petaluma the next day. Mr. Wolf, one of the Independents, had dreamed about the two evangelists. When he met Loughborough and Bourdeau, he confirmed they were the men he had seen in his dream. This opened the way for the group to accept their ministry. The tent was pitched, and meetings were held from mid-August to mid-October. Even though there was public opposition, 20 accepted the Adventist message.

Later that year, Bourdeau and Loughborough spoke in different places in Sonoma County. They held 50 meetings in Windsor. Twelve people accepted the Sabbath, and a Sabbath School was organized. One of the Adventist converts had Abram La Rue working for him. La Rue read some of the literature and went to the meetings. He too accepted the message and became the first Adventist missionary to Hawaii and later to China.

Santa Rosa proved to be very open to the message preached by Loughborough and Bourdeau. The first baptism took place there on April 11, 1869. The first Adventist church was erected in Santa Rosa the same year. They established the first Adventist organization there, with the following officers: president D.T. Bourdeau; secretary, J.F. Wood; treasurer, J.N. Loughborough; executive committee, D.T. Bourdeau, Merritt G. Kellogg, and John Bowman. When the committee was formed, Bourdeau reported: “When we came to Petaluma we knew of but one in this county who was keeping the Sabbath. Now we know of at least seventy-five.”

This number had risen to over 100 by the following year, worshiping in four churches.