Editor in Chief, Basma Bsharat

Copy Editor, Lamia Abdallah

Layout Editor, Fadia Alagha

Arabic Editor, Fadia Alagha

Advisor, Rania Mustafa

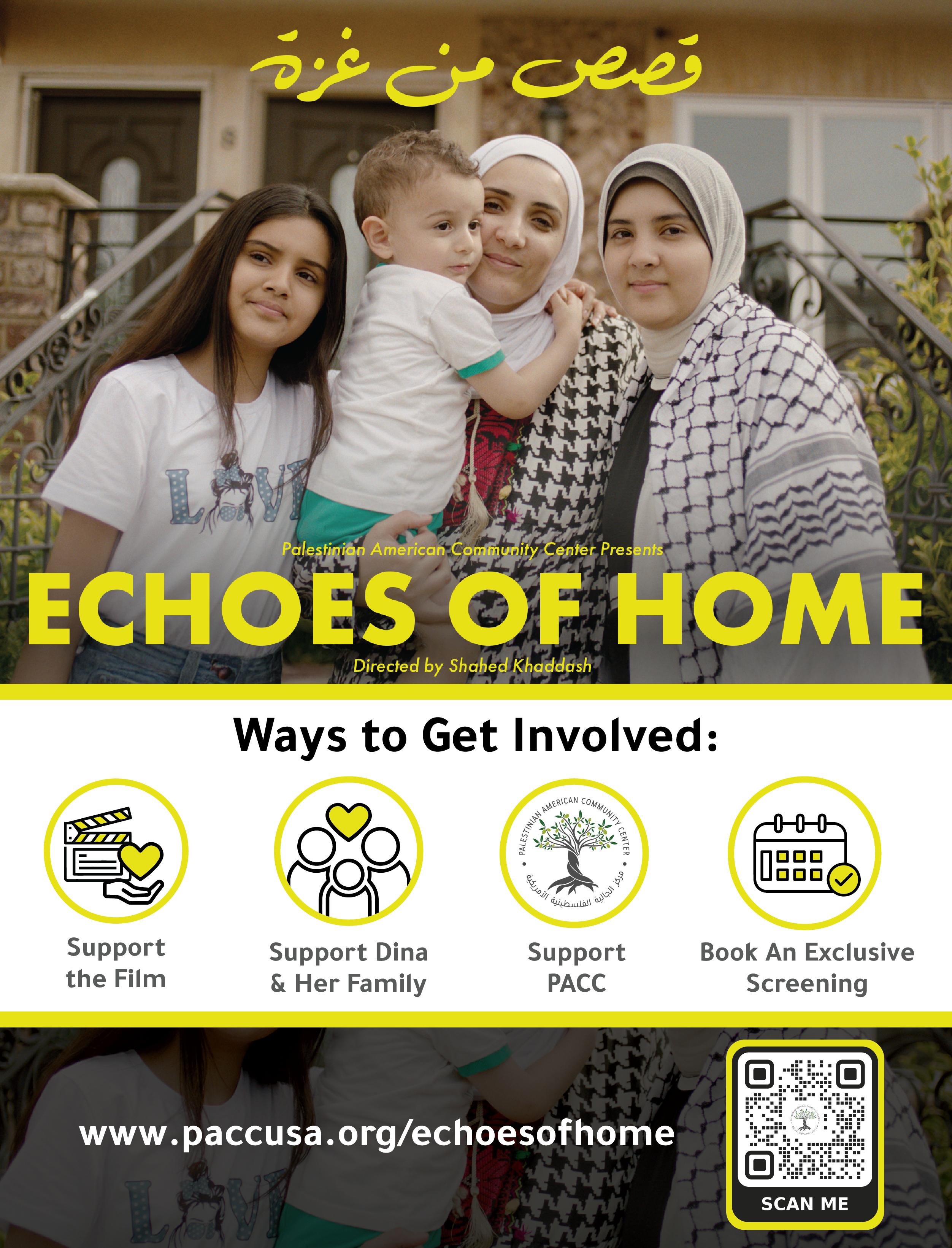

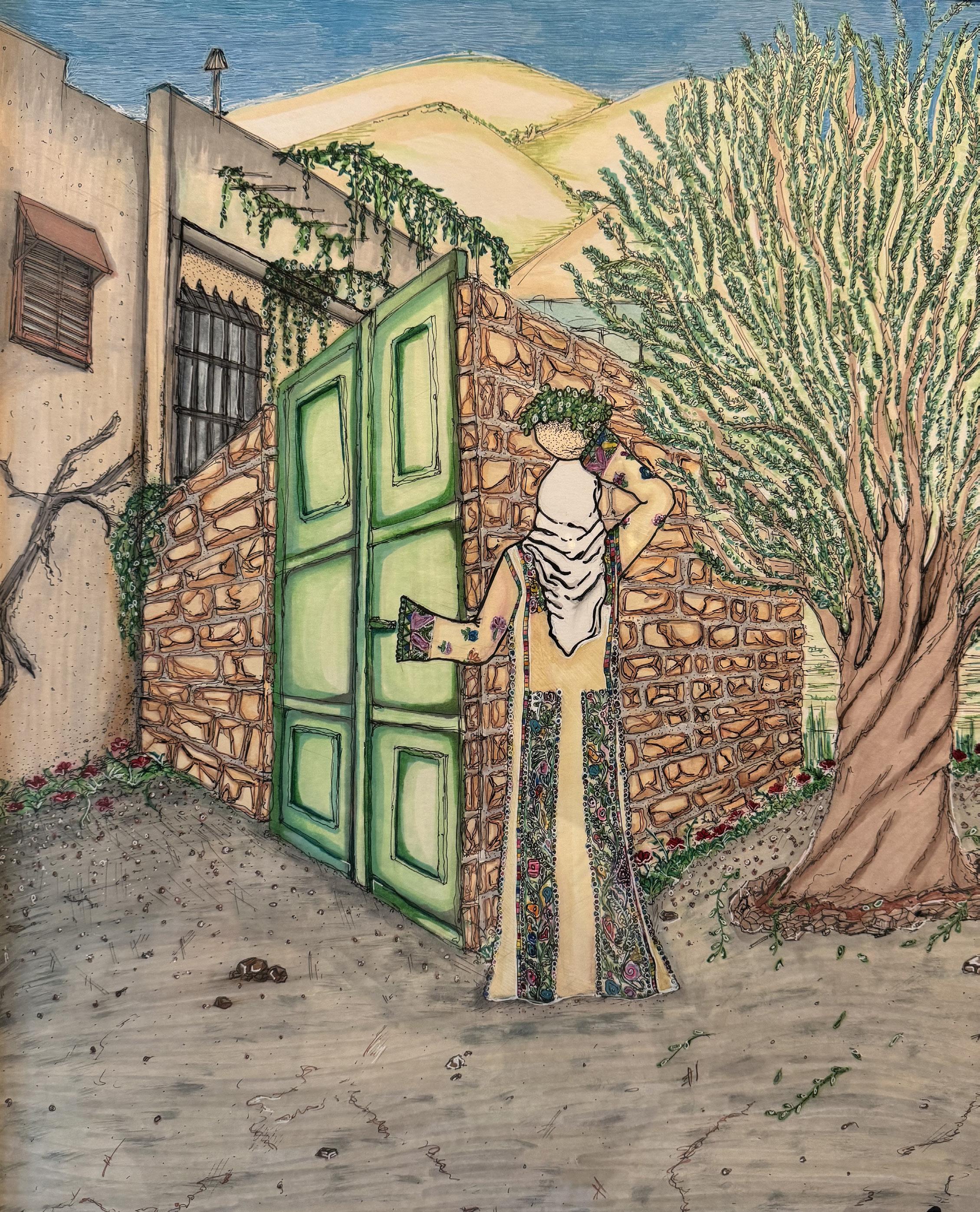

Thank you to world-renowned artist and Bethlehem native Taqi Spateen for this issue’s powerful cover art, painted live during Palestine Day on Palestine Way as part of the national mural tour From That Land, organized by the Jerusalem Academy of Arts, Al Hub Chicago, and The Mural Movement, led by Thaer Alkiswani. Best known for his work on the Apartheid Wall—including the George Floyd mural—Taqi dedicated this piece to 14-year-old Amer Rabee, a member of our community recently killed by Israel in Turmusayya, and to all martyred Palestinian children. The mural features the poppy, a national symbol of resistance, rootedness, and remembrance.

We are deeply grateful to our Board of Directors for making this project and this magazine possible, to the volunteers and community members who brought it to life, and to our Executive Director Rania Mustafa for capturing the cover photo. Falastin Magazine continues to thrive thanks to the dedication of our staff, contributors, and volunteers, the generosity of our sponsors, and—most importantly—you, our readers. You can follow Taqi’s work at @taqi_spateen, and the mural tour at @alhubchicago and @thaeralkiswani

973-253-6145

388 Lakeview Ave Clifton, NJ 07011

paccusa.org

info@paccusa.org

Siti’s Stories: Returning Through Storytelling

Laila Khalil

Resistance Symbolism

Waseem Shakhshir

Zip Ties, Tents, and Turtles: Behind Palestine Day

Bayann Amer

Palestine Way

Petals of Resistance رابص Prickly Pear Cactus

Jenah Elnatshe Jenah Elnatshe

Jaweerya Mohammad

A Tribute to Amer Sawt Al-Silence

Sarah Mustafa M.M.H.

Yazan Peeled an Orange in Yaffa

Safiya Hamdeh

Safiya Hamdeh E.G.

Scattered In Gaza, Seeming is Not Like Being

Alaa Salah Bahjat Arafat

Dear PACC family,

We are honored to present the second issue of this volume of Falastin magazine.

The overarching theme of this volume is Return, and this issue focuses on Return as Resistance. We invited contributors to reflect on how they resist Israeli occupation through organizing, culture, and community. From Waseem Shakhshir’s powerful piece on Palestinian music as a living form of resistance to Safiya Hamdeh’s heartbreaking tribute to Yazan and Sadam, two Palestinian children whose lives were stolen—each contribution speaks to loss, dispossession, and an unwavering refusal to surrender.

This past month marked 77 years since the beginning of the ongoing and systematic Nakba. The Nakba is not a closed chapter in history—it is a continuing structure of settler colonialism that persists to this day. Now, more than ever, we bear witness to the deepening of this reality—in Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem, and all across historic Palestine. But Palestinians have never stopped resisting. In the face of dehumanization, displacement, and genocide, we continue to hold fast to our land, our history, and our identity.

We also continue to organize—together. Through community-rooted events like Palestine Day on Palestine Way, where thousands gathered in Paterson, our home away from home, we build spaces of belonging, solidarity, and resistance. These moments remind us that return is not only about geography—it’s about reclaiming who we are, together.

Our hope is that Falastin magazine stands as a humble offering—an act of resistance rooted in the power of the diaspora to remember, to organize, and to return.

Until freedom, Basma Bsharat Editor-in-Chief of Falastin

By Laila Khalil of Siti’s Stories: Highlighting Palestinian Women

Two Sitis. Two women. Two different lives. Yet both gave me something immeasurable: love, wisdom, and a deep appreciation for my heritage. I think about my grandmothers almost every day. Their presence, their influence, and the way they shaped me are woven into my life in ways I will never fully be able to put into words.

The lessons my Sitis taught me don’t just live in memories—they live in the way I move through the world. In the way I carry my Palestinian identity with pride. In the love I pass on to my children. Their legacies ground me in a culture that has always resisted erasure.

Growing up, I made it a point to ask my grandmothers about their lives—their struggles, their joys, their migrations. I knew even then that I was gathering something sacred. And I knew it had to be shared.

When my paternal grandmother, Siti Shay, passed away two years ago, I wanted to honor her in a meaningful way. That’s when the first seed of Siti’s Stories was planted: an idea for a podcast rooted in cultural memory, education, and the empowerment of Palestinian women across generations.

Then, this past September, my last living grandparent, Halema Salama, passed. With her, an entire generation of stories was gone. I realized there was a whole treasure chest of stories I would never get to hear.

So, Siti’s Stories was born—born out of grief, but also out of love. Love for our Sitis, for our people, and for the land we all long to return to. It is a space to honor the women who came before us, preserve their stories, and reflect on how they shaped our resistance—even when history tried to forget them.

Return doesn’t always mean a physical journey. For many of us in the diaspora, return lives in language, in memory, in song, in dance, in the recipes and rituals we continue. For me, it lives in storytelling.

Through Siti’s Stories, I’m building a digital archive of resilience and resistance. Each episode is a small act of return: a step back toward the wisdom of our elders, a reclamation of memory, and a refusal to let our stories be lost. Stories don’t just root us in the past—they help us imagine a liberated future.

Sit with your elders. Ask them about the land, the life, the loss, and the love. Record and share their stories. Learn their recipes. Wear their thobes. They are the ones whose memories hold the texture of a home we’ve been denied. They are our living archives. And it is our duty to preserve and share their stories—for we will not know a way of return without them.

One of the greatest acts of love we can offer, as children of the diaspora, is to continue their tradition of storytelling. Because Sitis are more than grandmothers—they are our storytellers, our protectors, our historians, and the heartbeat of our families.

And every single one of them has a story worth telling.

This podcast is my way of returning through memory, through story, through resistance.

Follow Siti’s Stories on Instagram @sitis.stories, visit the website at podpage.com/sitistories, and listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts!

By Waseem Shakhshir

Music has always been more than a pastime for me, it is an essential part of who I am and how I relate to the world. I believe music holds an extraordinary power: to connect, to uplift, and to give voice to experiences that words cannot. As a musician, I see myself as both a storyteller and a bridge-builder, conveying universal emotions and unique cultural narratives. I strive to create music that resonates with people, whether through joy or nostalgia. My goal as an artist is to use music as a means to foster empathy, preserve heritage, and inspire change within my community and beyond.

I was raised in a household where music was not just heard, but also lived. My Syrian mother and Palestinian father both endured histories of war, exile, and instability, and music was how they kept those histories alive. My mother, one of ten siblings, was denied the chance to learn music herself, but when we lived in Syria, she made sure my brothers and I had that chance. Despite the pressures it presented while raising three children in a modest lifestyle, she carved out time and space for us to study and practice. My father, though not a musician himself, influenced me musically in other ways. He often sang Arabic classics at home, such as Umm Kulthum and his favorite, Farid Atrash, and filled our space with the sound of pan-Arabism anthems calling for Palestine’s freedom. He sang loudly in his house in the diaspora, sometimes offpitch, but always with conviction. His voice was a daily reminder that identity is something you carry in your chest and release into the air, note by note.

When the Syrian war erupted, I started to understand that music was more than sound. It was a force that could hold people together, convey what speech could not, and ground us when everything else felt uncertain. I was nine when we left Syria and moved to Palestine. One of the first things my

mother did after we settled was find a way for my siblings and me to continue playing music. We enrolled at the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music, where I truly began to shape my identity as a musician. Studying there was never just about theory or flute lessons; it was about becoming part of a shared pulse, a community where music created meaning, connection, and belonging.

Over my ten years of study, and later work, at the conservatory, my interests evolved, especially beyond Western classical and Arabic traditions. The circumstances in Palestine brought their own challenges, and I often found myself asking whether music must always be either abstract or concrete, or whether it can live in both forms. I was frequently asked, in interviews and conversations, about my “message” as a Palestinian musician. I did not always know how to answer. Could I simply enjoy music as others do, without carrying the weight of representation? Must every note carry a statement? Over time, I have grown more comfortable with that uncertainty. Music, for me, does not need to offer clarity. Sometimes, its power lies in being flexible enough to resonate with every interpretation.

I became increasingly drawn to questions of access and equity. I began to see that the structure around music–who gets to learn it, and who gets to share it–is just as important as the music itself. This has sparked a growing interest in managing the music scene, especially in Palestine, aiming to foster and develop it. I envision a system that is fair and inclusive, where no child feels they must skip school to pursue their passion, and no one is excluded from music education due to financial barriers.

Looking forward, my goal is to contribute to the Palestinian music scene by helping create a space where access to music education and creative expression is open to all, not just the privileged few. Growing up, I felt lucky to be able to follow my passion, but I want future generations to know that music is not a privilege; it is a right, and a way of shaping their world. My long-term vision is to

support a music culture in Palestine that is inclusive, empowering, and rooted in shared storytelling. I imagine a platform where musicians from all backgrounds can share their voices, and where the richness of Palestinian culture is preserved and promoted.

(Continued on next page)

The more time I spend in the United States, the more I come to value the deep cultural roots I carry with me. In a time when I see active efforts attacking aspects of our identity, which have become increasingly threatened with erasure, distortion, or appropriation, I feel a growing urgency to protect and grow our cultural voice. This is what draws me to the field of cultural management and what fuels my desire to shape the musical landscape in a way that honors our fruitful history and empowers future creators.

When it comes to the struggle for existence, music is not the first weapon that comes to mind. In the context of military occupation, forced displacement, censorship, and the fragmentation of daily life, it is easy to assume that resistance emerges solely through demonstrations, political negotiations, or armed confrontation. Few would imagine an oud carried across borders, a song recorded in a refugee camp, or the cracked voice of a grandmother, singing folklore beneath wedding lights. And yet, in the context of Palestine, these seemingly modest actions form an essential part of the resistance fabric.

It would be a mistake to understand Palestinian music merely as a soundtrack to struggle. Music in this context does not serve to entertain, soothe, or distract. It operates as a cultural engine of endurance and meaning-making. In every revolution, there is a song. “For Palestinians, music is not just an art form; it could be survival. The ability to sing, to compose, to perform, and to transmit musical knowledge across generations is, in itself, a refusal of erasure. It is a quiet but persistent answer to the forces of disappearance that seek to unwrite a people and their history.”

The importance of music in struggles for justice is often acknowledged, but rarely understood in its full complexity. Music in this context is not only a vessel of storytelling but a mechanism of memory, a map of identity, and, often, the only safe space left for political expression. In Palestine, where

expression is constantly monitored, policed, or coopted, music provides a coded language. It carries the weight of the past, the pain of the present, and the hope for what is yet to come. Songs that appear folkloric or romantic may embed stories of land dispossession, martyrdom, and longing. Instrumental choices, maqam modulations, and stage aesthetics are not arbitrary. They are intentional, and they are political.

Palestinian music is not a passive or decorative cultural product. It is shaped by displacement and return, memory and myth, community and exile. And within it lies a web of resistance that is often subtle, metaphorical, and deeply layered. From mawwals sung in village weddings to hip-hop verses recorded in the diaspora, Palestinian music reflects the multiple dimensions of Palestinian life: joy, loss, faith, rebellion, and survival.

The notion of symbolism is especially central. In the context of Palestinian art, symbolism is rarely abstract. It is almost always forged out of necessity. Whether confronting state repression, avoiding censorship, or responding to generational trauma, Palestinian musicians have cultivated an extensive repertoire of indirect expression. This includes lyrical metaphor, allegorical storytelling, musical motifs, and visual cues in live performances. These symbols do not dilute the political message, but they sharpen it, and allow it to travel further, resonate deeper, and last longer.

Palestinian music, far from being homogeneous, stretches across genres, regions, and generations. It draws from Bedouin poetry traditions, Ottoman-era melodies, Jerusalem radio broadcasts, communist anthems of the 1960s, the resistance songs of exile in Lebanon and elsewhere, today’s electronic beats from Ramallah, and so much more. Within all this diversity, the through line is the refusal to forget and the insistence on returning. Music becomes both a mirror and a shield, a recollection and a projection.

By Bayann Amer, PACC Office Manager

Palestine Day on Palestine Way, from a community member’s point of view, is a time to reconnect with old friends, make new acquaintances, and involve oneself in the ever-growing and flourishing Palestinian American community in Paterson. A grand spectacle that draws in crowds not just from the state but from all over the country, it makes every participant feel a sense of belonging, a feeling of familiarity, and an aching for home.

At the Palestinian American Community Center, it is our honor and privilege to gather all the resources of our community and bring to the public a day of reflection, resilience, and renewal. And while the day went by too quickly, the performances and speeches ran a little too smoothly, and the vendors did almost too well in sales—none of it would’ve been possible without the morning chaos and the tried-and-true efforts of all our staff and volunteers.

May 18, 2025—a day so highly anticipated—started like any other: stumbling out of bed, clinging to the last few remnants of sleep. Slathering on SPF 50 to prepare for the stinging sun rays I knew would be chasing me. Rushing to dress myself in the most comfortable attire I own because I anticipated running, jumping, reaching, and kneeling my way through the day’s events. I stuffed my fanny pack with the day’s essentials: two Sharpie markers, a pair of scissors, a handful of zip ties, Advil, some loose Band-Aids, and, of course, chapstick. In record time, I was prepared for the madness of the day. The only things missing were my large iced vanilla latte with oat milk from Coffee Cabana and my keffiyeh bandana—two things I go nowhere without.

As I made my morning commute to Paterson, New Jersey—the epicenter of our Palestinian American convenings—I went through all of my responsibilities in my mind. Am I certain that all 90+ vendor banners are printed and spelled correctly? Fingers crossed. Did I tell the food trucks the correct

address? Here’s to hoping! Do all the vendors have their correct table assignments and instructions on where to go? I’m sure they’ll let me know if they don’t. Please tell me the porta-potties have been delivered… they better have been. By the time I completed my mental checklist, I had arrived at Main Street, Paterson—or as we like to call it, Palestine Way.

I leapt from my car into a sea of red and sweatyfaced volunteers, staff members, and board members who had already been grinding since dawn. I immediately got to work alongside my fellow organizers. Our one collective mission: open and assemble 104 tents in one hour. Once all the tents were up, everything else should have been a cakewalk. And it was—sort of. Except for the fact that this day, of all days, was the windiest, causing the tents to fly, flip, and skip all over town. As soon as we could catch the flying tents and pin them down, we began hanging the business name banners from each and every tent. It turned into a kind of synchronized dance—two or three people stationed at each tent while I walked down the middle like a coach on game day, calling out, “Put ’em up, people, let’s go!” I paced back and forth, checking each banner to make sure it was straight and hung in the right zone. Finally, the tents were up, the banners were hung; next, it was time to greet the vendors.

The vendors were lined up like race cars at the starting line, waiting to be let in so they could start unloading their inventory to sell to the masses. Our head volunteers were stationed at each street— Goshen, Grove, and Michigan—making sure everyone in line was a certified vendor, not just some random person trying to pull a fast one on us. We were prepared for everything. I ran down each line of cars, checking people in for their designated time slots. I repeated the same script for each one: “Hi, how are you? Can I get your name and booth number?” At this point in the day, I was rattling

off orders and words I’d said thousands of times. I probably looked like a crazy person. But that didn’t matter now—my highest priority was making sure the vendors got to their tables and started unloading.

Slowly but surely, a routine flow settled in between the vendors and the head volunteers, and a sense of calm took over. Another part of the event, done and dusted. Now, it was time to let the public in and maybe, just maybe, enjoy the rest of my day. Throughout the afternoon, I spent my time running from vendor table to vendor table, putting out little fires everywhere—trying to make sure everyone was completely satisfied with how the day was going. Along the way, I heard a rumor: someone was down on Main Street selling unsanctioned street turtles. To my shock and disbelief, I found the man—only

to realize he had already sold every single one of his little street turtles. I abandoned my street-patrolling duties and set off to find something else that needed fixing.

At exactly seven o’clock, it was “officially” over— another successful Palestine Day on Palestine Way in the books. But now came the cleanup. And oh, was there a lot to clean up. The city street cleaner barreled down Main Street, lifting dirt and debris into the air; it blew into my face and my hair, but at this point, I was too exhausted to care.

I plopped down on the nearest bench and took in the scene. My feet were bruised and blistered, my hands dirty and scraped—but I was just happy the day was over.

By Jenah Elnatshe

I live near a town called Paterson’s heart, A place that feels like a piece of our start. They call it “Little Ramallah,” the closest we get, To a home we remember, a home we can never forget.

The streets are alive with the spirit we share, Palestinian flags waving proudly in the air. Restaurants serve falafel and sweet kanafeh plates, The flavors of home crossing faraway gates. There are hair salons, bakeries, and markets so sweet,

The sounds of Arabic spill out to the street. Even a road named “Palestine Way” stands tall, A reminder of our roots, a piece of us all. It’s not the land we left behind, but it’s close in its way,

A place to gather, to dream, and to say: We are still here, strong and free, Carrying our heritage like the olive tree.

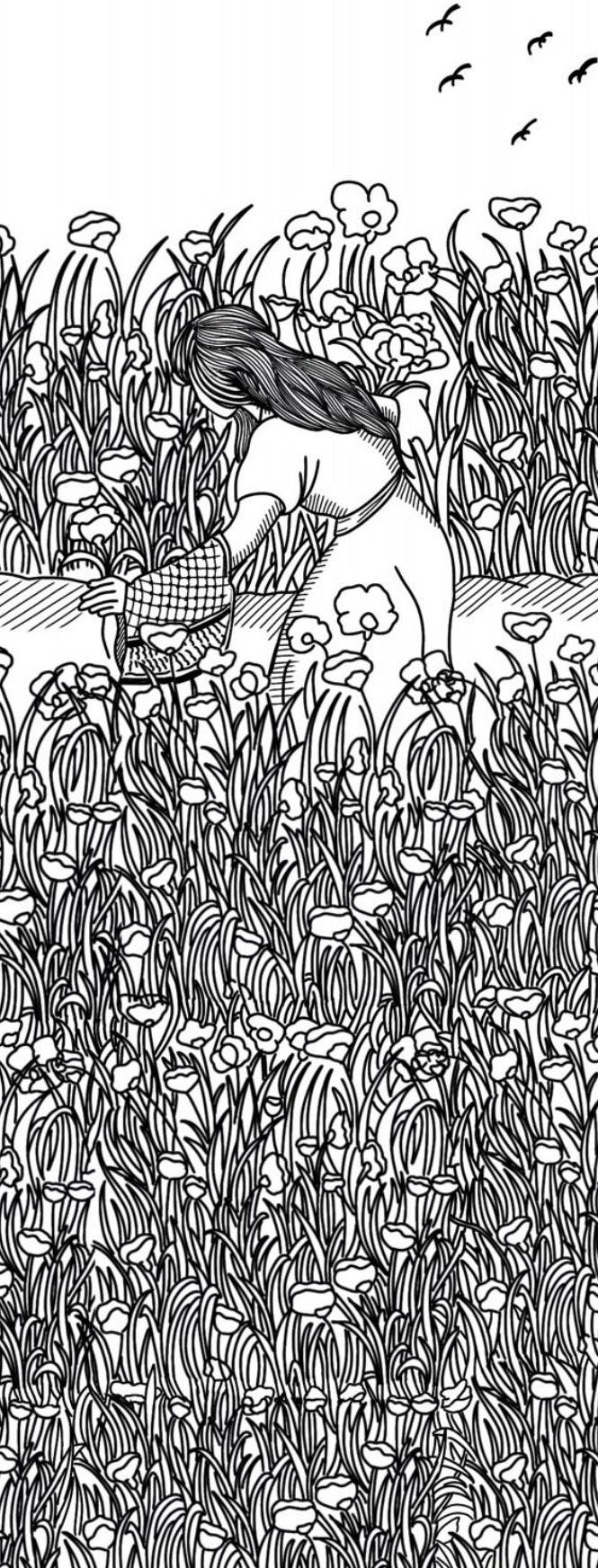

“Palestine Way” is a poem by Jenah Elnatshe from her forthcoming book, Stuck Between the Olive Trees. It is accompanied by an original illustration by the author.

By Jenah Elnatshe

Across the fields, red poppies bloom, A burst of color that breaks the gloom. The poppy, our symbol of pride and might, Its petals spread courage, pure and bright.

Red like the blood of those who defend, With roots deep in the soil where stories never end. The poppies sway gently in the breeze, Standing tall in the land we seize.

They remind us of beauty, even in pain, A symbol of hope that will always remain. Though the flowers may fade, their seeds will grow, Just like our love for the land we know.

In every petal, a promise to keep, Our hope will rise, no matter how steep.

“Petals of Resistance” is a poem by Jenah Elnatshe from her forthcoming book, Stuck Between the Olive Trees. It is accompanied by an original illustration by the author.

By Jaweerya Mohammad

flowers open-mouthed like ripened citrus, its pulp and fruit a marvel of cool sweetness,

after its spiny hairs are plucked and thick, waxy skin is sliced in halves, its carved belly trickles stored rainwater, like sloshing tears, there are clustered patches standing like faces everywhere, climbing up, gulping dry air, their roots damp, thriving, soil soaked with martyrs’ sweat, immovable.

Originally published in the Berkeley Poetry Review, Issue 54 (Spring 2025).

By Sarah Mustafa

Abrupt from sleep, The call comes— unexpected, yet somehow always feared. The phone trembles in hand, but this ring feels different. It echoes like a siren through generations of grief.

One call. Then another. And another.

Each one slicing deeper, tearing lives apart with the same terrible news. Picking up the phone feels like catching a bullet straight through the chest.

“Amer has been shot.”

Rush.

To call for help. To save a life. To hold onto a heartbeat. But you’re kept on hold—

“Please wait a second,” they say. But Amer doesn’t have a second.

You pace with prayers, you scream into silence. You search for someone—anyone— who will listen, who will care.

“He’s a U.S. citizen,” his father pleads.

“He’s one of yours. Help him.”

But silence answers. Silence, complicity— then

eleven shots.

To the heart.

To the head. To the future.

Blood paints the ground. And Amer, sweet-faced, bright-eyed, full of dreams, is gone.

His once predestined future halted, shattered mid-breath. His academic promise— papers, grades, hopes— meaningless to the finger behind the trigger.

His U.S. passport offered no shield from the U.S.-funded bullet that tore through his chest.

Amer Rabee—only 14. Not a number. Not a headline.

A son. A friend. A boy. A dreamer. Now a martyr.

By M.M.H.

Silence hums on the crimson stained sand, winds whisper with rightful demand. revival tethered by still breath— faith chokes loud in quiet death.

in Gaza the sky won’t sleep, stars blinded through a smoke-slick heap. the world loses count through the days— teeth clenched in anger towards hollowed praise.

hands hold signs in bleeding light, screens glare warm with a digital fight. no stone moves, no borders fall— grief is loud, yet resilience does not stall.

iman remains though qahar-filled hearts are raw, reality exposed as courts fall as the sacred law. what is to stop the bloody stream— guilt returns to thread an Arab dream.

how does man remake this crime? has he unlearned nothing through breaking time? mothers kneel with eyes half-wide— while the world forgets who died.

still, they walk with burdened grace, numbed by bombs we won’t face. truth stands in the ash and stays— shame repeats in endless ways.

Palestine is not a cry— it’s the land, the soul, the why. though we pray and say “never,” silence ends—and starts— the silence is all ours.

By Safiya Hamdeh

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa.

And I watched him, memorizing every detail.

Of that little boy.

The sun beat down on him, And blurry heat divided us. His brow was furrowed, His eyes focused only on the orange In his tiny hands. He was oblivious to everyone And everything around him.

He peeled back the skin

With greasy fingers,

And when juice squirted on a cut On his forefinger, he winced.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa. His light brown hair was bleached by the sun, His skin tanned

From the heat that kissed it

As he sat under his favorite orange tree.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa.

Someone called his name; He barely looked up from his orange. Yazan remembered his home As having the ocean in front of it

And the orange groves behind it.

Yazan loved the ocean, but not as much As his precious oranges.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa. He stood in the middle of The dusty street.

Sweat dripped down his brow, And if someone saw him, They would have thought he was crying.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa.

And he tossed the peel into the ocean

Like a child who still believed

That if you made a wish and threw something In the sea, Your wish would come true.

But Yazan knew better than that. He had stopped wishing a long time ago. The sea swallowed the orange peel, But not his wishes.

For even the waves know that some dreams Die before they come true.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa. And he slowly opened it, Fascinated by each perfectly cut slice. Whenever Yazan ate oranges, Juice always dripped down his chin, Staining his crisp, ironed shirts. Yazan loved to run through the groves As sunlight danced through the leaves. Now,

Only shadows remain.

Yazan peeled an orange in Yaffa. But then the occupier came. Yaffa became Jaffa, And Yazan’s beloved orange groves Were stolen.

Maybe in another world, Yazan is still peeling an orange in Yaffa, And no one has ever tried to take it away. Yazan never got to taste the sweetness

Of his favorite fruit. Whenever I visit little Yazan’s grave in Yaffa, I remember to bring him an orange. Sometimes I still hear him Asking to have an orange from Yaffa,

Again.

He says that he Just wants to taste them

One more time.

By Safiya Hamdeh

10-year-old Saddam Rajab was killed by an Israeli sniper in Tulkarem, occupied West Bank. Saddam’s murder was caught on camera and he remained in critical condition for 10 days before succumbing to his injuries.

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Come back to the streets of Tulkarem

Play soccer with your friends

And go to school every morning

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Come back to the alleys of Tulkarem

Play hide and seek

Come back and laugh

And play

And smile

Whatever you do,

Don’t scream

Please, I beg you

Don’t scream

Your screams will forever haunt me

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Don’t go outside at night

The soldier sniped you

And you fell to the ground

You screamed and pulled up your shirt

When you saw where the bullet

Had torn through you

You whimpered and continued to scream For your father

Baba! Baba! BABA!

You continued to scream on the ground

I CAN’T STOP HEARING YOUR SCREAMS

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Come back to your home

Your father and mother miss you

Your room is empty

Filled with nothing

And everything

Your clothes are still neatly folded

Your books are on the shelf

And your bed is still unmade

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Come back to sunny days

And rainy nights

Watch birds that glide through

The clear blue sky in the day

And gaze at the stars

That float above us

Late at night

Oh Saddam, Where have you gone?

Come back to your village

But don’t go out alone at night

Look both ways and make sure

There are no soldiers

When you cross the road

Come back and clean up

The puddle of blood

That spilled out of you

And stained the street

Gather it all up

And put it back inside

Your body

We can’t have you dying of blood loss

Oh Saddam, Where have you gone?

Come back so that I can find you

I will look for you

In every tiny alley

And behind every closed door

I will search all over for you

I will walk from Akka

To Haifa

To Gaza

To Deir Dibwan

To Ramallah

To Nablus

To Balata

And to Jenin

Or would that all be for nothing, And will I find you?

Screaming for your father, Somewhere in Tulkarem?

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

We truly do miss you

Come back, oh Saddam

And smile while you walk through The streets of Nur Shams Camp

Wave to the crowds

That will greet you

We will carry you on our shoulders

Above the fences

Past the Wall

And into freedom

Oh Saddam,

Where have you gone?

Come back and we’ll hug you

We will smile as you run into our open arms

We’ll cheer and laugh

But that’s all a fantasy, I guess

Because I don’t think you’ll ever come back

In reality

We heard your screams

Echo through the village

We visited you at the hospital

Bringing you flowers and hoping for the best

We prayed late into the night

Asking our Lord to let you live

But ten days later, Allah called you to Him

And you obeyed, going up

To the heavens

We wrapped you in a shroud

Tied a keffiyeh on your head

And draped you in the Palestinian flag

We carried you on our shoulders

Above the fences

Past the Wall

And into freedom

Oh Saddam,

Don’t you miss us?

Don’t you hear us crying ourselves to sleep

Late at night?

Don’t you see the pain scratched

On our scarred faces?

Don’t you remember us?

Oh Saddam,

Come back and wipe our tears

With your laughter

Come back and remove our pain

With your smile

Come back and never forget us

Oh Saddam,

Come back, please,

Just come back

By E.G.

In the past, women often wrote under male or anonymous names—not because they lacked voices, but because the world wasn’t ready to hear them. Writing was an act of survival; signing with their real names, an act of danger.

Today, the fear takes different forms, yet it still exists. I choose to write without a name—not to hide from the truth, but to protect it. Because the stories I tell are not mine alone, but echoes of many unheard voices.

These stories do not seek fame, only impact. Don’t ask for a name—ask for meaning.

Scattered is a heartfelt story about a family of brothers and sisters who once lived together in Gaza, but have been separated by the devastating effects of war. The narrative follows their individual journeys as they are dispersed across different parts of the world, each facing their own challenges and struggles. Through family photos, messages, and memories shared across distances, the story reveals their resilience, their hopes for reunion, and the emotional toll of being scattered—yet still connected by love and a shared past.

With braids framing her small face, she stood confidently in front of the camera, no older than five. Her fingers formed the classic pose beneath her chin, a radiant smile lighting up her face. On her tiny shoulders hung a pink backpack, ready for her first day of kindergarten. Behind her, bombed-out buildings and a drab gray sky told another story— but she didn’t care. Even the brown tent she had just stepped out of faded into the background. All that mattered now was the photo.

“And there was little Mariam, ready for school like any well-behaved student.”

“She looks like a little angel,” someone said.

“I didn’t know kindergartens still existed in Gaza.” “There are initiatives,” came the reply.

“They help kids escape the war, even if just for a little while.”

“Let me show you Nora’s picture from Jordan.”

Twelve-year-old Nora stood tall with long black hair and a headband. Behind her, golden sand dunes rolled gently under a clear sky. Her white T-shirt bore the image of another girl—brown-skinned with a headband—and she wore a small bag, just like the character on her shirt. Her eyes, framed by glasses, held a quiet intelligence.

“When did she get so tall? Has it really been a year?”

“She’s growing fast. Wait until you see her in two years.”

Laughter followed, and then a new photo appeared in the group chat—Jehan from Khan Yunis in Gaza. She sat on her bombed balcony, wearing a prayer dress, smiling in front of an earthen oven she had built herself. With gas prices skyrocketing, this was how she cooked now. A pot of leftovers sat on a wooden table, a kettle blackened by fire-boiled tea above a wood flame. In one hand, she held a loaf of bread; in the other, a towel to wipe off soot.

“The children were craving something sweet.”

“Why don’t you make Anbar, like Grandmother used to during the first Intifada? Get small apples, dip them in sugar with lemon—that was delicious.”

“Apples, sugar, and lemon? Where do you think we live?” Jehan replied, laughing. “There’s none of that here. If there is, it’s so expensive it might as well not exist.”

“No bread? Let them eat cake,” joked another sister, echoing the infamous line attributed to Marie Antoinette.

(Continued on next page)

Artwork Credit: Abdullah Imran Free Palestine Project

“You think it’s a joke? I made 27 loaves yesterday. You know how many are left? Only two.”

“How?!”

“I sent Ali to the bakery with them—he came back with fewer. Some went to neighbors; some were eaten. We share what little we have. Wheat, food, fruit—everything’s scarce now.”

Then a photo came from Mahmoud, seated in what looked like an embassy waiting room—plastic chairs, people clutching documents, weary faces. He looked heavier now, glasses slipping down his nose.

“Where are you applying this time?”

“Maybe this time they’ll give me the visa.”

He had tried many embassies—each one a new country, a new hope, and the same quiet rejection. A video notification appeared.

“I found this,” someone said. “Two years ago, before the war. At the pool.”

The video played: children splashing, fathers catching them mid-jump, mothers rushing with towels and snacks. One young man danced with a ball, refusing to let anyone take it. Food covered the tables. Apples, large and small, sat untouched.

“That was a loud explosion,” a sibling in Gaza said suddenly.

“What happened??” Mahmoud asked from Egypt.

“Is that shooting from your side or ours?” another sibling from Gaza asked.

“Seems like it’s everywhere now,” replied someone from elsewhere in Gaza.

“Not sure where that was, but look at this video,” the sibling in Jordan said.

A clip began uploading: Ambulances raced by with

sirens screaming. Children—bleeding, dazed—were rushed to hospitals. Mothers rushed toward the chaos, calling out their children’s names. A father sprinted beside them, his face coated in dust, eyes searching. He seemed to have just made it out from under the rubble. One boy, no older than ten, bleeding from his arm, clutched a bundle of clothes to his chest, refusing to let anyone take it…

By Alaa Salah Bahjat Arafat

Killing human beings, losing money and property, lacking food and drink, and lacking a sense of security and tranquility mark the outbreak of a fierce and sprawling war, like a spider’s web attacking everything on Gaza’s land. Gazans struggle against these complex crises and catastrophes born of war just to stay alive. When all these tragedies converge in a small area called Gaza, Gazans summon the strength of their hearts to endure, binding themselves tightly to withstand a life beyond description—a life of misery and hardship imposed by the brutal conditions of genocide. Gazans have eaten the prickly pear with its thorns—such is the intensity of their endurance. The sea is before them, and the smell of death follows them at every moment. There is no escape from death; it is either death or more death. My feelings and soul pour these words into your hands. This is the story of my sister Samah and her seven children— one of the many real stories produced by the war on Gaza’s land. Samah, her husband, and their children are its characters.

When a temporary ceasefire was announced for forty days and displaced people in the south were allowed to return north to their original homes, joy poured into the hearts of Samah and her children. They would return to their home and neighborhood in East Al-Shujaiya. They had been absent from Al-Shujaiya for about a year, not knowing whether their home was still standing or had been bulldozed. Although they had to return on foot—a harsh and miserable journey that began at 7 a.m. and lasted until 3 p.m. due to traffic and the immense number of displaced people (about a million)—the family didn’t feel the fatigue or hardship of the distance because of the joy that filled their hearts.

Samah and her children reached Al-Shujaiya and started looking for the street that would lead them to their home. The shock was that the family couldn’t recognize the streets and roads of their neighborhood due to the disappearance

of landmarks and the presence of sand hills and mountains of rubble, the result of bombings and bulldozing. After much difficulty, the family located their house using the remains of neighboring homes. My 20-year-old nephew, Abed Al-Aziz, saw their home from afar and exclaimed, “Dad, this is our house—standing on columns!” The family was delighted to find it, even without walls. The structure was in better condition than the surrounding homes. They settled in, rearranged what remained, replaced the walls with blankets and nylon sheets, and used a wooden table in place of the destroyed kitchen counter to adapt to the new reality. Yes, it was their home—the place they were born in, played in, ate in—all their memories rooted there.

They stayed for 40 days. Aid began to enter the Strip and was distributed to the people. Everything began to improve until the Israel military broke the ceasefire agreement and issued evacuation maps for Al-Shujaiya and other areas. This was the sixth time my sister’s family had been displaced. They had nowhere to go and no transportation due to the bombing of many vehicles. There was no gasoline, oil, tires, or spare parts, and even if transportation was available, the cost was extremely high. This forced the family to remain at home two more days until the situation became too dangerous to wait.

Artillery shelling intensified, and they were forced to leave against their will, their eyes brimming with tears amid the explosions, fearing they’d never return. Samah quickly grabbed the bag of official documents, packed some clothes and canned food. Each child carried a backpack and clothes. Most importantly, they carried one bag of flour on Ali’s bicycle—a dream gift before the war, now a vehicle for survival, used to transport water, firewood, and essentials during the repeated displacements.

They set off at top speed, with artillery shrapnel flying over their heads like swarms of locusts. Their 16-year-old daughter Sondos, who suffers from a rare and severe inflammation in her right knee and

was awaiting treatment abroad, couldn’t walk long distances. Her father gave her a cane and asked his sons to walk ahead while he supported her. He carried two blankets, a backpack, and a gallon of water in one hand while she leaned on his other. The shelling intensified and struck one of the fleeing displaced, killing them instantly. Terrified by what she witnessed, Sondos tried to quicken her pace despite the pain. Eventually, the family reached the outskirts of Al-Zaytoon, away from immediate danger. They rested on the roadside before heading to their cousin Imad’s partially damaged house in western Al-Zaytoon.

Sondos could walk no further. A kind, displaced man with a donkey-drawn cart took pity on her and gave her a ride on top of his belongings. The rest of the family continued on foot.

Finally, after an arduous journey through death and misery, they arrived at Imad’s house, already crowded with displaced relatives. Everyone was in a miserable state—chapped lips, pale faces, emaciated bodies, torn shoes exposing scratched toes blackened with dust. The house was like a hole full of mice. There was no space to breathe, and no clean clothes to wear. They slept curled like snails, tightly packed due to the crowding.

After a month, the last precious bag of flour ran out. The parents worried how to feed the children, who had no food except what they received from charity centers. The thought of returning home to retrieve the remaining flour bags meant certain death. Samah’s heart broke seeing her children hungry while knowing food was trapped in their home.

Aid ran out, borders closed, no supplies were allowed in, and the price of flour and legumes skyrocketed. Samah, who had tried to be a strong oak for her children, was shaken when her threeyear-old daughter Tasneem asked for a crumb of bread. She had none. She distracted Tasneem, saying, “I’ll bake in a little while, wait, sweetheart.” These words continued until noon, when both

Tasneem and her six-year-old sister Lana cried from hunger. Samah was forced to send Abed Al-Aziz to grind the kilo of lentils she had saved and make bread discs to ease their hunger.

The children didn’t ask for meat, fruit, or vegetables. Despite their age, they had learned to accept whatever food was available. One piece of bread— that’s all Tasneem wanted. Today, it was lentil bread. What will tomorrow bring? A series of torments and catastrophes that Gazans face every moment since war descended on Gaza. Patience and survival are their only weapons.