Prologue

With only a few moments to go before Lot 242 bidding went live, multiple thoughts were still racing through the collectors’ minds:

• How many others around the world had actually connected all the dots?

• Should the top bid limit be raised?

• Did we miss something in all the evidence that would invalidate our unanimous conclusion?

• How did it get here?

• This can’t possibility be what we think it is, can it?

The number of Slack posts over the previous week had been much higher than normal. As more evidence and documentation was added to the channel, the number of theories grew, which in turn prompted lively debates from the four members who comprised this small group. Each of them had spent countless hours over the last decade researching Danish modern, hoping to uncover clues, here and there, in vintage documentation and online records that would assist in identifying furniture to add to their collections.

Furniture, after all, is what is most closely associated with Danish modern during the middle part of the last century. More a movement than a style, early modernism at the Bauhaus school in Germany had eschewed historical context and traditional construction in favor of a new, industrial-based aesthetic. However, with

such a strong national woodworking and cabinetmaker heritage, modernism in Denmark was built upon the foundations of traditional design and construction. This new Danish mindset extended well beyond furniture to a wide range of visual and applied arts. But it was the elegant wood framing of Hans Wegner, the sensuously upholstered curves of Arne Jacobsen, and the bold colorful forms of Verner Panton that captured the attention of the world during the post-war economic and cultural boom. The resurgence of mid-century modern over the last 20 years had spawned a new appreciation for Danish design, which had faded from the global eye during the latter part of the 20th century. During this recent revival, the timeless purity of this furniture separately caught the eyes of Jason, Thomas, Zephyr, and Carl and inspired them to establish and start growing their personal collections. Although from different backgrounds —geographic, profession, cultural, and age— they all shared a passion for not only collecting Danish modern but also delving into research which could help fill in the many missing segments of its history in the public realm. In addition to appreciating the underlying design tenets of Danish modern, the four collectors also happened to place a high priority on accuracy in attributions and learning as much as they could about the history of the designers and manufacturers behind the furniture. It was these common traits that led them to create a Slack group, an online communications platform, where information

and discussion could be more easily shared from their dispersed physical locations in Norway, Oregon, Albuquerque, and Chicago respectively. Instead of competing against each other for acquiring pieces, and restricting knowledge gained during research, they shared information, vintage documentation, and theories within the group. Not only was this sharing of ideas beneficial to all four in elevating their collective knowledge but it also spurred discussions and debates. Personal theories would need to be well-developed to successfully pass through the gauntlets of critical challenge. The result of this discourse— based on historical documentation and personal experience— was the elevation of their shared knowledge to a level that none of the four would have been able to achieve on their own.

As personal furniture collections tend to be limited in size, in direct proportion to available space in the collectors’ homes, there was a continuous upgrade process where a possible acquisition had to surpass a rising design standard to bump a lesser piece out of the house. While Danish smalls were scattered throughout their homes, the focus was primarily on finding the next hidden furniture treasure that popped up for sale. With the comprehensive vintage document library that they had assembled over the years, the Danish modern Slack group —it was small enough that they never bothered to create a real name for themselves— was able to identify many of the unattributed, important designs that occasionally surfaced at auction houses. Since they were usually up against deep-pocketed dealers in many of those auctions, they had to rely more on wit than wallet to come out on top in lots where attribution and provenance were not apparent. This research and acquisition effort had been primarily focused on Danish modern furniture and not on paintings.

So, when a Danish modern painting popped up at a well-known Chicago auction house, in the early summer of 2021, there was instant recognition of its content but not of its true origins or significance. The listing description stated it was a watercolor of a Baker

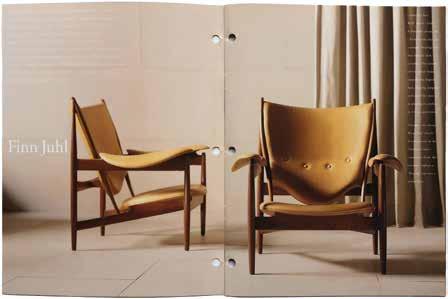

Chieftain Chair by Finn Juhl. Many individuals who follow auction listings around the world create online search alerts, where they receive e-mails of listing notices based on specific keywords. Serious mid-century dealers and collectors all have “Finn Juhl” and “Chieftain” in their alerts, as Juhl’s Chieftain Chair is one of the most— if not the most— iconic design in Danish modern. Therefore, the expectation was that many parties would have been alerted to this lot. The question was, how many had dug past the initial description and looked at the content within the painting? Most Chieftains from the 1950s and ’60s, including the very first ones, were handmade in Denmark by the cabinetmaker, Niels Vodder. A Vodder Chieftain is unquestionably the most desired production version of this chair. A year after the Chieftain Chair was designed in 1949, Juhl entered into a licensing agreement with Baker Furniture, based in Holland, Michigan, to hand produce a line of furniture in the United States. Carl, one of the collectors’, just so happened to own one of the few Chieftain Chairs that Baker had made in the 1950s. The majority of Baker Chieftains in homes today are from a re-issued production run in the late 1990s. A 1950s Baker Chieftain watercolor would certainly hang nicely on the wall next to his 1950s Baker Chieftain Chair.

In his youth, Finn Juhl originally wanted to become an art historian, before a compromise with his business-minded father resulted in the son’s enrollment into architecture school. Although trained as an architect, Juhl returned to his first love of art by using watercolors to help bring life to his architecture and furniture technical line drawings. Copies were often made from original line drawings and then watercolored afterwards for use as either gifts or for marketing purposes. Juhl had famously used watercolor in 1950 to help convince Baker to approve his designs for production, after the black-and-white line drawings initially sent were returned and rejected. Recent interest in Finn Juhl has blossomed to the extent that a book dedicated

solely to his watercolors was published just a few years ago, in 2015. Watercolors by Finn Juhl, by Anne-Louise Sommer, was compiled and supported by the Designmuseum Denmark, where most of the original watercolors that Juhl created during his lifetime now reside. These watercolors were part of a large drawing and documentation archive donation by Juhl’s widow, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, after his death at an early age in 1989. With limited Juhl watercolors left in private hands, the pre-auction estimates of $3,000-$5,000 was perhaps a touch on the low side, even for a watercolor of an American-made Baker Chieftain, painted on a reproduced drawing.

Except this watercolor wasn’t done on a copied drawing, nor was it of a Baker Chieftain.

The painting was something a lot more significant and historical than that. After a week of frantic research and debate, the research group had concluded this right before the auction started. Not every question was answered, nor was every inconsistency fully explained. And while the four did not agree on all parts of the theory, they were confident that the watercolor was a very rare treasure that would not come up for public auction again. With the clock winding down on Lot 242, the most important question of the day was not whether their assessment was correct, but rather:

• How many dealers, collectors, and museums in the world were aware of this auction lot,

• How many of those came to the same conclusion as the research group in the identification of this painting, and

• If any others made it this far, how big were their wallets?

If the answers to the above questions skewed the wrong way, then chances were that the research group would be priced out early in an international bidding war. If it skewed the right way, then it could end up being a good day— a very good day. In accordance to

the standing protocol that was established years ago, the other three yielded bidding rights to Carl; not only was he the first one to see and post the auction listing in the Slack channel, but the auction was also in his hometown of Chicago.

The four never bid against each other.

Yet, while Carl was technically the designated bidder for Lot 242, the importance of this particular piece and the lively discourse amongst them that helped identify it had the other three feeling part of the bidding team in spirit. As the start of auction crept closer and closer, the pace of the posts quickened...

The Poet Sofa (FJ 41), designed in 1941, and first exhibited at that year’s Guild Exhibition. The upholstered seating shell exhibits less padding than the overstuffed furniture of previous years.

The Vanity Chair, with sheepskin upholstery, was first exhibited in the 1943 Guild Exhibition (above). Similar to many previous designs, this chair went straight to Finn Juhl’s house afterwards for personal use (left). This design was never put into production by Niels Vodder, and the whereabouts of this transitional chair today is unknown.

form which apparently strains the wood to its utmost limits.”23 This statement is remarkable in that an architect critic has put the cabinetmaker first in praising the chair, with the designer, Juhl, mentioned almost as an afterthought. This quote demonstrates the admiration and acknowledgment that Vodder received for having a critical role in Juhl’s designs. This respect extended to his fellow cabinetmakers as well. In his autobiography years later, Ejnar Pedersen, co-founder of the workshop P.P. Møbler, remarked,

I would go as far as to say that if we had no Niels Vodder, we would not have had the Finn Juhl we know today… and he was never afraid to go out

where the ice was thin. If you look at some of the furniture that Vodder made for Finn Juhl today, most people will say, ‘It can not be done. It can not be that way,’… I have always had great respect for him - he was simply one of the best in the subject.24

It is believed that only 12 Bone Chairs were initially made by Niels Vodder, making it one of the most highly sought-after pieces in Danish modern. If Juhl is to be graded in hindsight, there should probably be a minus next to the Bone Chair’s “A”. Although stunning in design and composition, Juhl and Vodder may have ended up exceeding the structural limits of the wood after all, when factoring in durability over time.

The Bone Chair (FJ 44), made of Cuban mahogany and natural leather, in Niels Vodder’s 1944 booth (opposite). Juhl referred to it as his favorite design, and later acquired a pair from an original owner. Both chairs are still displayed in the house; one with natural leather in the study, and the other with black leather in the primary bedroom (below).

As evidenced in contemporary photos, the back elbow joints have been repaired in most of these 12 chairs, indicating a structural weak point in the design when stressed under sitting loads.

While the Bone Chair signaled the arrival of maturity and technical sophistication in Juhl’s designs, it was his follow-up act in 1945, which marked a watershed moment in Danish design history. The 45 Chair (FJ 45) made its debut at the Cabinetmaker’s Guild that year, redefining what Danish modern would be moving forward. All the design evolution over the first part of the decade culminated in a chair that became the icon for Juhl’s new design ethos: bearing-vs-borne. Expanding on a developing theme from prior years, the 45 Chair finally achieved separation of the “bearing” elements, the organic structural wood frame, from the “borne”, the upholstered seat bucket that receives the form and weight of the person sitting in the chair. Granted, the seat bucket did have a hidden internal frame of wood, but the primary components of the chair were now distinct from each other. To emphasize this separation, Juhl detailed small connection points at the chair’s shoulders and knees, and allowed a visual gap to separate the upholstered areas from the adjacent framing. Paying attention to detail, small leather welt cuffs were wrapped at the interfaces of upholstery and framing to provide a clean transition. A recessed rear seat rail with notched ends helped further a feeling of the seat floating within the frame.

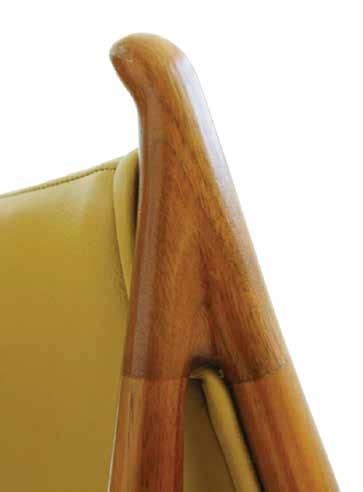

The frame itself was perhaps Vodder’s finest moment as a master cabinetmaker, as well as the pinnacle of how far the duo could go in combining their talents to achieve new heights. Juhl’s architectural design was sleek, refined, light, and sophisticated. Yet, it was not a frame that any rational woodworker would consider designing. The swooping curve of the armrest from the front legs to the shoulders is supported only at the elbow, where the rear inclined leg extends upwards. With the slender size of the members and the complex three-way joint at the elbow, this would be a

The 45 Chair (FJ 45), a milestone design in Danish modern, where bearing and borne components were separated into distinct elements. The earliest chairs incorporated tufted back and seat cushions (above), which Juhl eliminated a few years later.

The 45 Chair (FJ 45), a milestone design in Danish modern, where bearing and borne components were separated into distinct elements. The earliest chairs incorporated tufted back and seat cushions (above), which Juhl eliminated a few years later.

the master cabinetmaker, Niels Vodder, Kaufmann Jr. was now trying to sever that link to promote Juhl as the genius that will be able to achieve success with Baker.

Juhl and Kaufmann Jr. would go on to collaborate on curating exhibitions throughout the 1950s, including an extension of the Good Design series. These exhibitions were well-attended and instrumental in helping to increase awareness —and sales— of Danish modern in the United States.

Beyond a productive and beneficial working relationship, Juhl and Kaufmann Jr. also shared a lasting personal friendship throughout their lifetimes. From that initial meeting in 1948, they travelled together many times over the years, on vacation and to view art, including trips to Italy, Greece, Fallingwater — and naturally, each other’s homes in Copenhagen and New York. As a subtle testament to the importance and impact that Juhl and Kaufmann Jr. had on the American embrace of modern design, a 45 Chair has a permanent place in a corner of Fallingwater, which was donated in 1963 to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy to become a museum open to the public.

Considering the strong professional and personal bonds shared between the two men, it would not be surprising if Finn Juhl had gifted a cherished personal item to Edgar Kaufmann Jr. sometime in the early 1950s. With the Interiors articles, publicity tours, and Good Design exhibitions, Juhl’s star was about to shine brightest in the United States, due in large part through the actions of Kaufmann Jr. Juhl was well aware of this impact on his career, noting late in his life that Kaufmann Jr., “has definitely been my guru and motivator in the U.S.”33 The presentation of a meaningful gift from his own personal collection, one which represented the design creativity which Kaufman Jr. had helped promote, would have demonstrated the high regard that Juhl held for his close friend. If true, it could provide the missing link for how Lot 242 found its way to Chicago during the summer of 2021.

still chose to mostly use traditional designs as a base, from which he would distill new modern furniture. His FDB J16 rocking chair of 1944 (American Shaker), Fritz Hansen bentwood armchairs of 1945 (Chinese Ming Dynasty), and Johannes Hansen Peacock Chair of 1947 (English Windsor hoop) are all still in production today, a testimony to his talent for extracting the essential qualities of a traditional piece to create timeless designs. By 1949, Wegner was finally ready to create his first truly modern chair, the Round Chair; one that would catapult him past Finn Juhl on both the domestic and international stages during the 1950s.

A generational descendant from his first Chinese chair design, the Round Chair was the quintessential distillation of what an armchair had been: backrest and armrest had been combined into a single

twisting horseshoe form, lightly supported by four gently tapered turned legs. An open caned seat highlighted the visual lightness and minimalist qualities of the design. Many consider the Round Chair the finest chair ever designed. The following year, Interiors magazine featured it in a full-page photo, noting that Wegner, “devotes himself to perfecting the shape and scale of the parts.”40 The Chair gained even more accolades after it was chosen to be on the set of the first televised American presidential debate, between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960. Rumors over the years suggest that the chair selection was a strategic accommodation by Kennedy’s campaign to help alleviate the pain in his back and avoid from him appearing uncomfortable in front of millions watching at home. Even if the decision was made independently

design credit to Niels Vodder. 49 As previous chapters have highlighted, the Juhl/Vodder relationship made it difficult to separate design credit to the architect. By the same token, while Juhl may not have had any firsthand involvement in these later Vodder designs, there can be no doubt from where the inspiration came.

Finn Juhl’s fourth design that year displayed similar features to other furniture in the booth but was a distinct and memorable design on its own. The simple title of “klapbord” (folding table) on the 1:5 competition board does not provide descriptive justice for the elegant organic design that was built. Staged to the right of the two-seat sofa, the two shared a board for the competition. An organic fixed teak top sat on a three-legged Oregon pine base. The tabletop, narrow at one end, flairs outwards on the other end. The opposite edge is straight with a hinged drop leaf below that somewhat mirrored the fixed tabletop shape. When propped up into the open position, the

table transformed into a fully organic shape with no straight edges. A large brass inlay disk on the drop leaf served as a built-in coaster on which cold drinks and hot dishes could be placed without damaging the teak. Although relatively simple in construction, compared to the rest of the booth, this beautiful design never went into production after the exhibition. Vodder

Without vintage documentation to clarify otherwise, Niels Vodder’s NV 54 credenza (below) could be mistaken for a Finn Juhl design.

Watercolor board from Finn Juhl’s entry for the 1949 Guild Exhibition design competition: Chieftain Settee and Butterfly Coffee Table, scale 1:5 (right). Although the booth layout showed the coffee table to be located to the side, this competition board shows it in front, obscuring the lower part of the Chieftain settee in the rendered elevation.

Watercolor of expansion plans for Finn Juhl’s house (left), dated 1970. The primary bedroom expansion to the west was built. However due to the decline of his professional practice, the southern pavilion design studio was never realized. Photographs from the 1970s confirm a second Chieftain Chair was located in this bedroom for a period of time.

A watercolor update from 1968 shows that Finn Juhl had grand plans for the house that year. In addition to a new bedroom expansion at the end of the west wing, a separate new building was also planned to the south of the existing house, to be connected by an exterior terrace. This new pavilion would house his design studio, indicating that he was still optimistic about the future and viewing the recent industry downturn as temporary. This watercolor also depicted a number of furniture changes around the house since the 1950 plan in Interiors. The west wing expansion created a new larger primary bedroom, which housed a bedroom furniture suite that Juhl had made for his second wife, Hanne. These pieces were made by the cabinetmaker, Ludvig Pontoppidan, during a brief collaboration with Juhl in the early 1960s, after the architect’s longterm partnership with Niels Vodder had dissolved in the late ’50s. A Chieftain Chair is also shown in the primary bedroom in the watercolor, demonstrating Juhl’s intent to finally incorporate a second chair in the house.

of the 1930s & 1940s from Baker Furniture”. This 184page volume included illustrations for over 600 reproductions that Baker offered. If it seems unlikely that a furniture factory could handle production of 600 different items at one time, it is because Baker wasn’t structured like a typical industrial factory. Instead of incorporating production lines, that churned out wooden parts that could then be quickly assembled together, Baker was more of a up-scale version of the traditional cabinetmaker structure, with a large skilled workforce of woodworkers and carpenters. Although

Although “fine furniture reproductions” were their core business during the 1930s and 40s (left), Baker Furniture started reintroducing modern-inspired designs back into their offerings in 1950. To help meet expanding demand, Baker acquired the former Limbert Furniture plant at Sixth and Columbia Streets in Holland that same year (below).

over 600 designs were offered at the time, each item was custom-made as the orders were received. What was sacrificed in factory production efficiency was gained in hand-crafted quality and flexibility in handling custom orders. By offering a wide range of traditional designs and maintaining a high level of quality, Baker was not only able to survive the Great Depression of the 1930s but able to position itself for growth in the 1940s. By the 1950s, high demand for fine furniture reproductions made it a $5 million business— over $56 million in 2023 dollars —that furnished high-end residences and businesses around the country. It was in this context that Hollis S. Baker first read about Finn Juhl in November of 1948.

By 1950, Scandinavian modern designs had started to gain a foothold in the United States. In no small part due to Kaufmann Jr.’s promotion, the term Danish modern started to gain prominence, beginning to separate itself from branding of the larger region. Ever watchful of sales trends, Hollis Baker slowly began to re-embrace modernism once again. In the first half of 1950, Baker went out of house to contract modern-influenced designs by A. William Hajjar and Davis Prat, the latter of whom had won a prize two years earlier in the MOMA Low-cost Furniture Design competition.67

Over this same period, Finn Juhl was developing his own strategy for not only expanding his individual brand but also looking to capitalize more on the commercial opportunities that his newfound global celebrity status had recently unlocked.

While the annual Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibitions, with their well-publicized design competitions, helped bring recognition to a new generation of architects, the low-volume nature of cabinetmaker production did not translate well into commercial success. Even if a prize-winning design was in high demand by the public, the small-scale workshop production methods could never generate a large enough volume to produce more than nominal royalty fees for the architects. A few cabinetmakers

sought to expand their operations, with more modern equipment, to be able to meet current, and anticipated future, demand. These actions were looked upon disapprovingly by the more conservative guild members, who felt such production betrayed the very essence of what it was to be a cabinetmaker. Often, architects would work with specific factories, independent from their cabinetmaker relationships, to design and produce furniture intended for higher volume production and lower price points. By making Danish design more widely available and affordable to the masses, both domestic and abroad, architects could realize significantly greater income, through increased sales and royalties, than what the cabinetmakers alone could offer.

In 1949, an entrepreneur, E. Kold Christensen, and two high-end factories in Odense, Carl Hansen & Søn and Andreas Tuck, convinced Hans Wegner that there was a successful future if they all collaborated on creating, marketing, and selling new modern furniture. Before then, the marketing and branding of furniture was centered around who sold the piece. For items that sold through the maker’s place of business, it would be their name, not the designer’s, that would be marked on the furniture. For items that sold through third parties, such as department stores, the maker’s name would then be suppressed (often physically covered up with a plaque), in favor of that sales outlet’s brand. For this new arrangement for Hans Wegner, both maker and designer names would be clearly marketed for each design, with Wegner’s name soon added to the maker’s mark of each piece of furniture produced. Christensen would lead a new sales organization that would control the terms for how the designs would be marketed and sold. With a company name that clearly identified its fundamental role, Salesco was set up to market the new furniture that Wegner designed for Carl Hansen and Andreas Tuck. With the owners of both high-end factories trained as cabinetmakers, Wegner quickly came on board after touring the workshops and meeting the journeymen who

time afterwards —until the mid-1950s— there was a radiused wood spacer, without a rubber bushing. Production afterwards had no radius at the rear stretcher joint.

• Some very early productions have a flat ledge at the top ends of the rear stretcher, with no ledge in later production.

• Used both 3 and 4 button layouts for the backrest; the very first chair in 1949 used 4 buttons in a “shallow” smile configuration, but some early chairs also used 3 buttons in a straight line. A clear rationale for the use of 3 or 4 buttons has not yet been identified.

• Very early production used 5 cut steel plate brackets connecting seat to frame. Most production used 3 brackets, sometimes machined steel plate, sometimes brass plate with rounded edges. One very early chair only has 4 brackets of unknown metal.

• Wood: mostly teak, some early imbuia, French walnut, a few later models made in Brazilian rosewood, and one known elm example.

• Armrest material: planished steel, with a few early examples of cast aluminum.

• Padding: early to mid-production used horsehair, cotton batting, muslin for seat and backrest; later production shifted to foam padding; no armrest padding for either.

Chieftain Chair by Niels Vodder; details were refined over the course of Vodder’s 20+ year production run. All examples have the stepped joints, some chairs have machines steel seat tabs, and middle-later chairs have flat backrest spacer tabs and only three seat tabs.

The 1990s Baker re-issue of the Chieftain Chair exhibits many cost reduction modifications that make this the least elegant version of licensed production. Capped horns, plywood armrests, and corner blocking for the seat frame are some of the identifying details.

at the Designmuseum Denmark. Unmounted on a thin vellum paper, the design and details for a rolltop desk and accompanying side table are depicted in unrendered black ink lines. Much more a practical, technical document than artistic presentation, this initial board provides a good frame of reference for how Juhl’s presentation style and skill would develop over the next decade. Although most of the descriptive text on the board was carefully inked in an architectural block drafting style, there is a cursive hand-written “turc” located in the lower right-hand corner.

Only one original design competition board remains in the archives for the following three years, 1938- 1940. While the whereabouts of the remainder

A watercolor of a building design from Finn Juhl’s university studies shows the early influence of Vilhelm Lundstrøm (above).

Black ink drawing board from Juhl’s entry for the 1937 Guild Exhibition design competition: scale 1:5m (right); the sole known remaining board from Juhl’s first year in the exhibition. This board provides a good baseline for his early technical presentation style.

As shown in the watercolor front elevation, Finn Juhl did not initially consider use of tufting buttons for the backrest (above).

The 1:1 scale detail in the design competition board shows Juhl’s initial idea for a steel plate armrest construction, including exposed steel plate stiffener and no wood cover strip under the armrest support (below right). No evidence has been found that would confirm this detail was ever built, even for a prototype.

The Author

Carl J. D’Silva is currently a Principal Architect at Perkins&Will. He has been practicing architecture in Chicago for 30 years after graduating from Virginia Tech in 1994 (Go Hokies!). Carl has worked on signature projects around the world, including the passenger terminal complex at the New Bangkok International Airport. His first book, Constructing Suvarnabhumi, is a photographic essay of geometric compositions captured during the construction phase of the airport. In 2014, he was elevated to Fellow in the American Institute of Architects. For the last 14 years, he has been an enthusiastic collector and researcher of Danish modern, whose design tenets of integrated design, engineering, and construction, closely mirror his architectural philosophy throughout his career.

The author holding up the Chieftain Chair watercolor for the first time after winning Lot 242.