The oT he r life

The Malaise of the Overcivilized

English Origins

Downing, Vaux, and Olmsted: The Rustic in America

The AD iroNDACKS

Thomas and William Durant

Grosvenor Atterbury

William Wicks and Augustus Shepard

The ChAleT

The Chalet: Kirtland Cutter in Chicago

The Log Chalet

The r A ilr oAD

Railroads, National Parks and the Northern Pacific

Sublime Imperialism

Yellowstone: Building a Railroad, Building a Park

Th e ru ST i C

Rustic Begins: Two Log Cabins

The Old Faithful Inn

The Longs Peak Inn

The Surreal

The fore ST rui N

Sacred Groves

The Portland Forestry Building: The Temple of Capitalism

Bernard Maybeck: The Grove of Redwoods

The Great Northern Railroad

Louis Hill: Monuments and Chalets

The American Sublime

Glacier National Park: The Hotels

Glacier Park Chalets: Into the Wilderness

Kirtland Cutter in Montana

Geolo Gy

Geology and Ruins

The S anta Fe Railroad

Mary Colter: The Lookout Studio and Hermit’s Rest

Geology: Herbert Maier and Gilbert Underwood

The Desert Watchtower: The Hopi, the Diné, and Mary Colter

Cultural Appropriation

Literary Rationalism

The Paradise Inn: Rationalist Prologue

Albert Good’s Bible

Stephen Mather and the Log Cabin

Park Service Pragmatists: Gilbert Underwood, Daniel Hull and Fred Willson

Park Service Romantics: Thomas Vint and Ernest Davidson

Herbert Maier and the Roofless Museum

THE MALAISE OF THE OVERCIVILIZED

What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed being shaken by the wind? But What did you go out to see?1

Jesus’ question to John the Baptist Matthew 11:7-8

Horace Kephart was to all appearances a success. He was, in 1900, the head of the Mercantile Library in St. Louis, married, the father of five children, and beginning a career as a writer and editor. But 1904 found him a changed man,unemployed, abandoned by his family, recovering from bouts of alcoholism and depression, and living in a tent in the woods to the west of Asheville, North Carolina. Yet none of the problems of his family and career were the sole reason or even the primary reason for his changed circumstances. He later explained: “This instinct for a free life in the open is as natural and wholesome as is the gratification of hunger and thirst and love. It is Nature’s recall to the simple mode of existence that she intended us for. Our modern life in cities is an abrupt and violent change from what the race has been bred to these many thousands of years.”2 He moved into a cabin with the inset of winter, but he never left the Smokies. He was not alone with these impulses.

John Burroughs owned a large, well-furnished house on the Hudson, but in 1896 he largely abandoned it and built a small log cabin for himself about a mile away. He wrote: “The work of reclaiming that wild land seemed to stir the aboriginal instinct in me and I found myself longing for a wigwam or cabin to which I might retire when I was in the mood and live a life of rude simplicity.”3 He stayed there twelve years. When he moved, he moved to another cabin.

In 1879, Frank Cushing was assigned by the US Department of Ethnology to spend three weeks at the Zuni Pueblo in western New Mexico. He spent five years there, learning their language, eating their food, wearing their clothes, learning their history and rituals. He was adopted by the tribe, and left only when the government forced him to.

All of these events took place between 1879 and 1904 and there are many similar stories from the same period of people abandoning not just their daily lives but the civilization that housed them for a life that was in some way archaic, following impulses they saw as intuitive, living the existence nature intended us for. It coincided exactly with Paul Gauguin’s departure from Paris to live a “primitive” life in Tahiti. Gauguin died in the South Pacific. Kephart, Burroughs, and Cushing made a clean, long-term if not permanent break with over-civilization, but there were others for whom escape was temporary. The escape might be for a summer in the Adirondacks.

John Muir, writing in 1901 said: “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.”4 Writing in 1981, T. J. Jackson Lears used this same term, overcivilized, to describe a central condition of the period 1880 to 1920:

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, many beneficiaries of modern culture began to feel they were its secret victims. ... American anti-modernism, particularly in its dominant form—the recoil from an 'overcivilized' modern existence to more intense forms of physical or spiritual experience supposedly embodied in medieval or Oriental cultures.5

Opposite: Horace Kephart’s first camp

Children’s District

The Kinderberg Shelter, 1866

There was a fundamental change of methodology in 1866. Rustic structures appeared in more conspicuous locations and dramatically increased in scale as a part of the creation of the Children’s District near the park’s southeast corner. This was a facility for mothers and children of the poor created at the insistence of the park’s commissioners. Its largest element was the Kinderberg (Children’s Mountain) Summerhouse built of unmilled cedar timber. It was another of Vaux’s giant octagons, 110 feet across and composed of 48 interlocking “trees,” set atop a hill with views and rustic furniture in which to rest (some of them reduced in size to accommodate children). Like Stukeley and Warburton’s analogs of forests it was trees turned into architecture or perhaps architecture returning to trees.10

Durant Cabin, 1889-92

Third phase: Log and bark facing on milled frame

Maid’s Cabin, 1877

First phase: Solid log wall construction

Spruce Lodge, 1880

Second phase: Sawmill siding on saw-milled frame

In 1879, Durant’s transport system began to take shape and with it a new building culture as it developed. That year he founded the Blue Mountain and Raquette Lake Steamboat Line with connections by stage from North Creek to Blue Mountain Lake, four steamers on Blue Mountain and Raquette Lakes, and wagons between the two lakes for baggage services and construction equipment and materials. The damming of the Raquette River provided access to Lake Utowana and provided Durant with the power for a sawmill. Travel to the area increased dramatically as did construction of accommodations. At the same time they were building the new Adirondacks they were destroying the old one, as we will see.

Pine Knot

There are three distinct phases of architecture at Pine Knot based on the extent of its connection to the industry beyond the Adirondacks and three languages of wood construction to go with them.

First were the true log cabins, built before the navigable river and sawmill, when the main connection to the railroad at North Creek was by canoe. It was a building culture of axes and solid logs—the language of rustic log buildings, built of solid logs and filled with twiggy furniture. These have a rustic authenticity, largely out of technological necessity. It included five buildings constructed as they appeared to be, straightforward log buildings of solid log construction, usually spruce. Also built was a larger cabin, the primary

residence, now called the Chalet. The was the true rustic phase of construction, of genuine log construction, and it was short lived.10

Changes in the transport system and the creation of the sawmill enabled the second phase of building at Pine Knot c. 1880, one that included sawmill lumber and access to shipped materials. These nine utilitarian buildings were conventionally framed of milled lumber and covered with sawn siding. They were service buildings, built in the most economical way. As always, here was a direct link between the system of transport and the culture of building.

Having disposed of a truly rustic system he created a fictive one. The third is a hybrid of the two, in which the logs and bark rustic first phase is veneered over the sawmill frame of the second. The buildings of this phase are clad with a rustic narrative that is largely ornamental, draping the frame with nostalgic veneer, first of bark then of half logs.

The central building, the Chalet, is an illustration of a technology in transition. Thomas' lower story of solid logs was built before the dam and steamship service. William’s top story, the structure of rustic veneer of stretched bark on milled lumber (some of it brought from Virginia), was built after, an incrustation of indigenous rustic coating on a standard industrial frame from the sawmill. The top half of Durant’s Chalet at Pine Knot is largely a fiction, yet it is the best evidence for its architectural significance of Pine Knot and the architectural contributions of Durant.

Pine Knot Chalet

Left: 1878 Chalet

Right: Chalet with 1882 addition

Structurally it is a log walled building with a log frame building within. The roof framing is 9-inch log rafters, spaced at 2 feet 6 inches. with 9-inch horizontal ties.

The second floor framing is a series of solid log joists running across the short dimension of the building supported by the exterior longitudinal walls.≠

Camp Uncas Lodge, roof framing

Camp Uncas Lodge, floor framing

Camp uncas lodge

In contrast to the many buildings in this text that use half-log siding on milled framed lumber, the Uncas Lodge is an authentic log cabin with solid 9-inch log walls squared off on their inside face. The roof beams, roof trusses and floor beams are peeled 9-inch logs.

The exterior walls are solid. They sit on a stone foundation wall. The floor and roof structure are largely exposed. Only the floor, roof decking, and some interior paneling are built of sawmill lumber.

The roof of shingles and boards is supported 9-inch log rafters, spaced at 2 feet 6 inches. With 9-inch horizontal ties.

The second floor is 9-inch log beams, spaced at 2 feet 6 inches.

Some rooms, particularly on the second floor, have walls with wood paneling.

Wall Section

Sagamore Lodge: Center room, ground floor

Sagamore Dining Complex, 1898-1927

Immediately adjacent to the lodge is a second building type, the much-enlarged and altered dining complex. It is dramatically different in form and material from the lodge, a rambling structure with a bark and small log veneer. It is the Pine Knot construction type. This suggests another architect, perhaps Durant himself. Durant’s rustic architecture built independent of Atterbury is more often than not only skin deep. Even in its original form it was far more varied and irregular than the lodge. If there is a Durant-designed building at Sagamore this is probably the one. It has few log walls. Like the later buildings at Pine Knot, it is a series of mill-framed buildings given a rustic incrustation of bark with log trim.

The original building at Uncas is solid log construction. The Sagamore lodge was half real. Each of Atterbury’s log buildings is fundamentally different including his last at Uncas.

Sagamore Lodge on the left and Dining Hall on the right

Wicks

Wicks, a Cornell/MIT trained classicist, had established a successful practice in Buffalo with Edward Green. Their most conspicuous work is the Albright Gallery, but Wicks had a passion for the rustic, particularly the Adirondack cabin, and made a detailed study of the log cabins and shelters in the West Canada Creek area near Old Forge. The result was a small book, Log Cabins and Cottages (1889), not only still in print but still in use as a do-it-yourself log cabin building manual. Wicks advocated not just rustic architecture but the rustic life. Like Kephart and Burroughs, he felt he was connecting to a primal, archetypal self:

Some recent anthropologists regard the amusements of the chase, as cultivated by civilized men—hunting, fishing, and the like—as 'traces in modern civilization of original barbarism.' If there is any truth in this theory, then the writer must confess that he is in a large measure a barbarian… As man has brought with him from barbarism to civilization traces of his original condition, so he must take back to 'the forest primeval” some traces of civilization.' 3

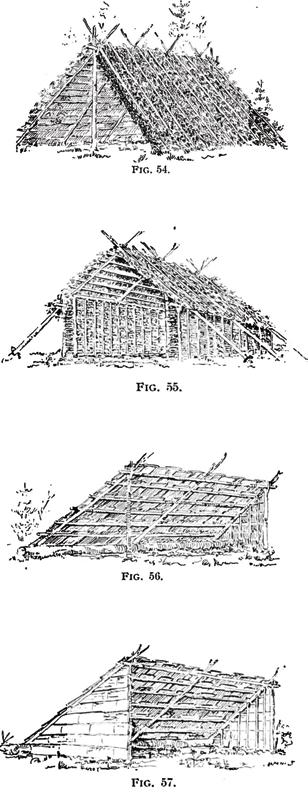

Wicks' book is a schizophrenic text in several ways. The first half is a step by step, axe blow by axe blow, set of instructions on how to build a simple log cabin. It describes preindustrial methodologies. There are no instructions on rustic veneers, half-log siding on sheathing masquerading as solid walls, no clapboard siding on studs masquerading as hewn square logs.

William

William Wicks Types of Lean-to

They are simple generic cabins, built in the woods with nothing more than an axe, crosscut saw and trees. There is an embodied acceptance in the text that materials from the sawmill—floor boards and window sash—were always necessary and at times sawmill sheathing and shingles. Wicks wrote that, “as far as possible they should be made on the spot and with the material at hand.”4

The second half of Wicks' book is decidedly an odd fit. It shows small plans and perspectives of 30–40 of Wicks' own rustic buildings. All are much larger, and structurally and spatially more complex than the simple log cabins that are shown in the first half. Nowhere can one discover how to build a truss, a covered porch, a balcony, or anything larger than a single room or two, assemblies that appear in abundance in Wicks' illustrated designs. Unfortunately, few of Wicks’ buildings are well documented, so how he dealt with these larger problems in practice is nebulous.

Wicks was part of a larger phenomenon, perhaps one he provoked, the revival of authentic log construction. Just as the industrialized Adirondacks, with its massive timber harvests and sawmill-driven building industry was nearing realization, there was in some quarters a revival of the old ways while attempting to reconcile the two technologies in a way that would avoid the stage set of Pine Knot. It is not an accident that return of the authentic log cabin coincided with creation of the railroad and the timber industry.

Pages from Wicks’ Log Cabins and Cottages (1889)

South elevation

Section looking north

BUILDING A RAILROAD, BUILDING A PARK

The railroads must have ties.

—Theodore

Roosevelt1

In 1877, the US army, anxious to assert their control over the Lakota Nation following their humiliating defeat at the Little Bighorn and death of George Custer the previous year, set out to build two forts along the Yellowstone and the Bighorn rivers. One, Fort Custer, was located upriver and only15 miles from the battlefield. The second, Fort Keough, was at the junction of the Tongue and the Yellowstone. Four companies of soldiers and 200 civilian workmen were dispatched by riverboat to the two sites. If this story were a movie, men with axes would have felled trees and placed them, with the bark on in vertical rows to form a stockade, sharpening the ends for additional protection. But this was not the case. These forts, like many of the day, were a series of individual buildings. Nor were the buildings all logs. They brought with them a portable sawmill. The buildings were built not out of logs but of milled lumber. Portable sawmills were usually steam powered, requiring wood for fuel, although some used water turbines. They were made in modules that were combined into a complete mill and required about four days to assemble.2

The buildings of the forts were not conventional balloon frame buildings but rather solid walls of stacked pieces of lumber six inches wide by two inches thick. The slabs were cut from local cottonwood timber and some lodge poles from the Lakota encampment of 1876 served as fuel for the sawmill.

Further downstream work had started on the second post, Fort Keough. Rough-cut lumber was secured at the government sawmill near the Yellowstone River and all the fine finished lumber was shipped in on steamboat. Since the majority of buildings were frame structures, a number of items still had to be brought by steamboat—138 kegs of nails, 21 bundles of window sash, and 18 boxes of glass. Here, something like log cabins had been built as temporary shelters—upright logs buried in the earth with a similar log roof. Chinked with mud, they leaked badly and were vermin infested, and their inhabitants quickly and happily moved into the milled-timber structures.3

It is not really surprising that a power sawmill was in use in so remote an area at so early a date. The pioneers of American myth may have journeyed west with an axe, but the portable sawmill was not far behind them, in fact if they came west by steamboat or rail, it probably came with them. Log technology, the log cabin, and the axe dominate the myth and popular history of the West but the portable sawmill and its allied architecture was no less ubiquitous.

This technology was not indigenous to Montana and neither was the architecture it created. The architecture that emerged in these forts is not rustic. It features gambrel roofs, double-hung windows with shutters, and porches. If these buildings speak of any place it is of the world the soldiers and their families had left to come there. If a log cabin was suggestive of anything to them it was probably discomfort and squalor.

Log crib trellis on the Columbia and Nehalem Valley Railroad, Columbia County, Oregon, 1906

The log cage joint

The log truss joint

Although lodgepole pine, this is the tree in its twisted form. The Gardiner Wonderland wrote:

Hundreds of miles of forest was searched for gnarled and twisted branches and trunks of trees. Nature’s forest cripples were collected by the thousand and the odd freaks of tree growth were seized upon and made part of the big hotel. ... Logs everywhere, and the oddest and most fantastic have entered most prominently into the architect’s intricate scheme of interior decoration.13

According to the Washington Evening Star “five woodsmen were brought here Wisconsin to look up freaks of timber for this purpose.”14

This is the craft of the surreal-the revelation of inner forces within the log. The twisted struts bring with them the memory of what they are and where they came from. The forces that over time that made it the shape and the forces acting on it today, so it is not just a glib observation that the inn is the architecture of nature is present.

The marks of the saw are hidden. The marks of the axe are exposed. The narrative is that of the rustic westerner and hand-tooled craft, not the railroad and its industrial sawmill. The dream of the temple growing out of the trees of a forest—the dream of Alexander Pope—was being realized across the West in 1905-1910 as we will see, but the inn is different. It is simultaneously

a literal railway trellis and a metaphorical forest. Not something a lover of the rustic would like but something far closer to the reality of the forces that created the inn—the massive power of nineteenth-century industry working in tandem with an indigenous craft sensibility. William Empson and Robert Venturi have written on the difference between confusion and ambiguity, a single work of art that generates multiple readings and which is not a problem but a virtue.15

Section at central court

Section at central court

Wood framing at Assembly Hall interior

Dining Hall

Dining Hall

Section looking east

West elevation

Many Glacier lodge Wall Section

It is far more refined and finished and far less rustic with far fewer logs that the Glacier Park Lodge.

The courtyard frame is smaller than the Glacier Park Lodge and framed with peeled logs,

It is built of log 48-foot columns tapering from 36-inch to 18-inch-22inch logs.

There is a 22-inch log beam entablature on top of the columns running along the long side of the atrium supporting 12-inch horizontal logs, one at each column, that connects to every third 12-inch log roof rafter to form trusses.

The roof is 2-inch tongue and groove boards on 12-inch log rafters 4 feet on center.

The interior walls are 2x6 studs covered with Sackett (gypsum) board and wood paneling.

The floor construction is 2x12 floor joists with a Sackett board ceiling with an exposed 10x10 milled beam at the edge.

Unlike the Glacier Park Lodge, the balcony railing is boards in Swiss profiles, not logs.

Deluxe Cabin Section looking south

Deluxe Cabin North elevation

Glazing, when it occurs, is in the wood walls between piers. Underwood’s stone is far more rectilinear and far less natural than Maier’s or Maybeck’s at Parsons.

Here the log wall was something like the traditional type but with the inner face of the logs covered. The walls were solid logs and the horizontal joints were heavily chinked with cement to create a weatherproof envelope, in the process giving the exterior very pronounced white stripes. The log walls are actually three-quarter logs, chamfered to form a flat, smooth surface that is on the inside faced with insulite, a thin wood fiberboard, that forms the interior finish. The logs are vertical at the gable ends. All the hidden lumber is milled.

The stone piers are an obvious reference to the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon, but Underwood used the same system repeatedly at locations whose geology had little resemblance to Bryce. The same piers were used at the main lodge at Zion and the Union Pacific Dining Hall in West Yellowstone. In fact, his geologic architecture is not particularly contextual even at Bryce. It may use local stone but its forms are based on rectilinear shapes highly geometric and highly abstracted and if the types of stone varied the forms did not.

This in a nutshell was the strategy—stones in their natural state, minimal mortar joints, minimal openings with minimal lintels, and slightly irregular edges at walls and parapet. It was regularity of line that made geology look like buildings. It was irregularity of line that made architecture look like geology. While Maier preferred the horizontal at Yellowstone or Yosemite or the south rim, Underwood favored tightly spaced vertical stone piers at Bryce and the north rim of the Canyon.

Union Pacific Dining Hall, West Yellowstone

The hoodoos at Bryce Canyon

Steel Frame H Columns

Edge channel ribs

Specially formed fabricated plate

Stone Enclosure

Desert Watchtower has always been popular with the public and the Park Service management long yearned to buy it before they finally did so. The educational part of the Park Service has always hated it. It was one thing that a fake ruin was situated at so unlikely a location contrary to any plausible history, but it was something else that it was a gift shop posing as a museum. Robert Farrel, a Park Service official, wrote:

I gag. I retch. I writhe on the floor in agony. The Desert Watchtower is totally unsuited to function as an interpretive facility ... In fact, it is totally unsuited to exist at all in my opinion. ... the damn thing was built to look like an Indian ruin, thereby attempting to foster a totally false impression of Indian architecture and use of that part of the South Rim. It should be dynamited, and as soon as possible.5

Yavapai was completed in 1928, and Watchtower four years later. The buildings are quite different but the architects had much in common. Both sought to learn from the indigenous architecture of the Southwest; both, on paper, forbade literal copying of precedent. Maier was 24 years younger than Colter and was clearly in her debt. What is best about Yavapai draws on Colter’s work at Lookout and Hermit’s Rest. What dramatically separates them is that in 1930 they were moving in opposite directions. Both Yavapai and Watchtower use literal historical quotations but Watchtower had far more of them and they are far more literal. The quotations would soon disappear from Maier’s work while in Colter’s work they were multiplying. The abstract refinement of Lookout had become the pseudo-kiva and Puebloan tower of Watchtower. Maier was moving toward abstraction. Colter and the Harvey Company had already moved into literalism.

The Kiva

Murals at the lower levels of the Watchtower