SUSAN MELLER

So you may see, if you will look Through the windows of this book, Another child, far, far away, And in another garden, play.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, “TO ANY READER,” 1885

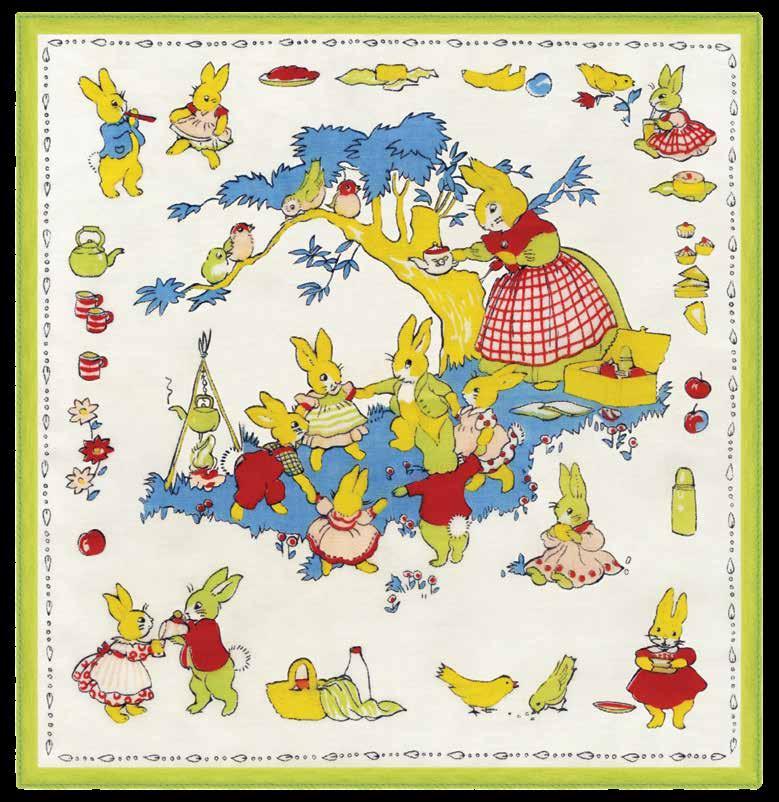

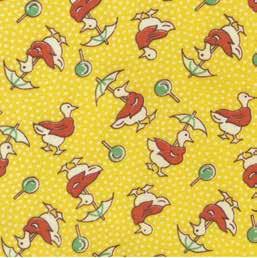

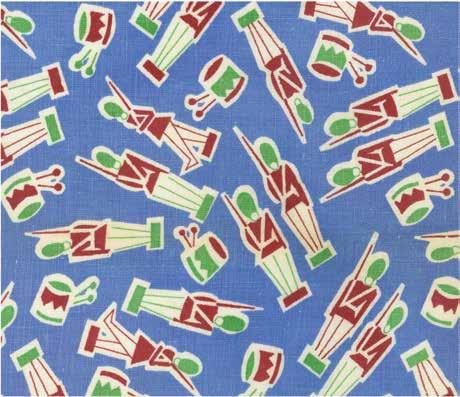

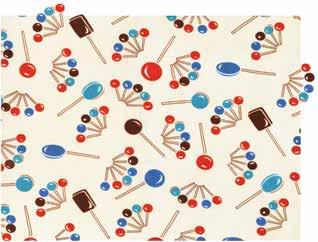

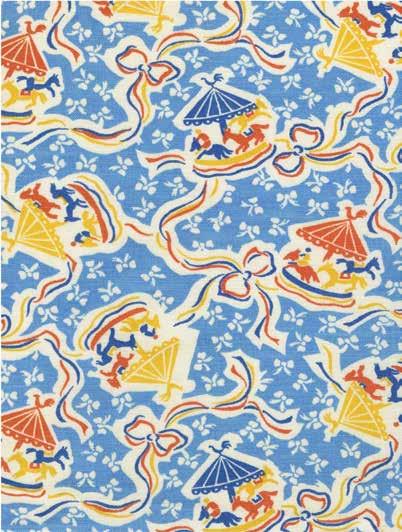

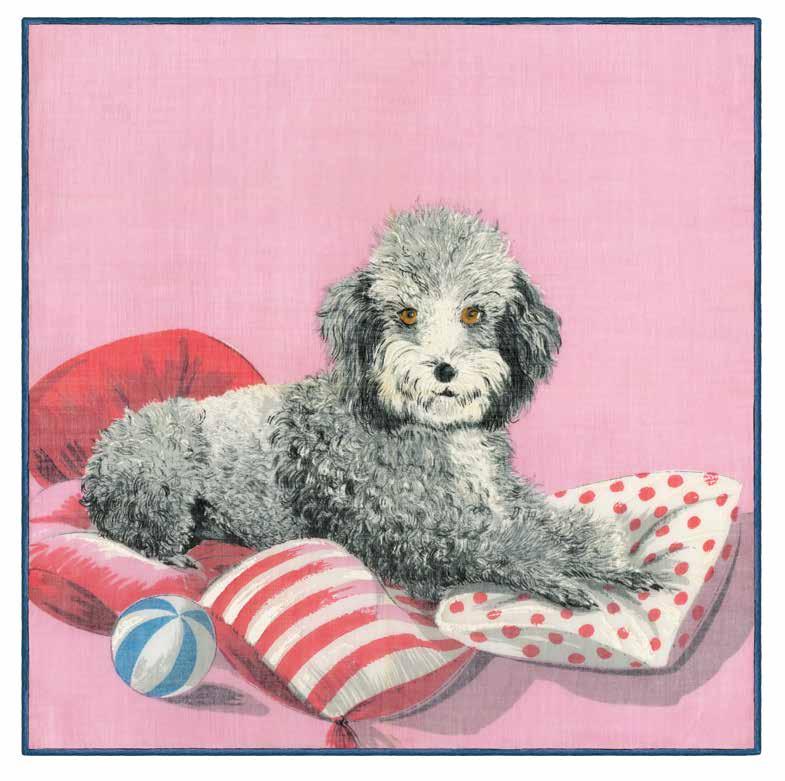

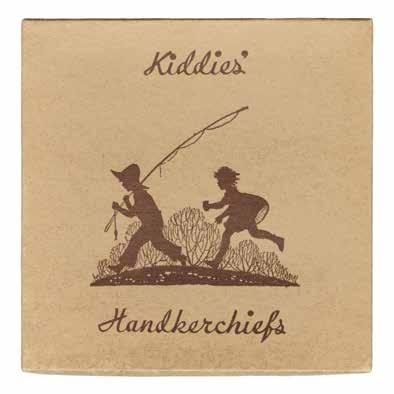

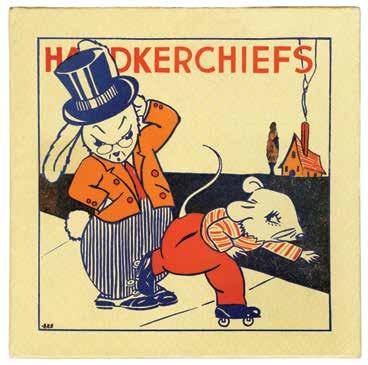

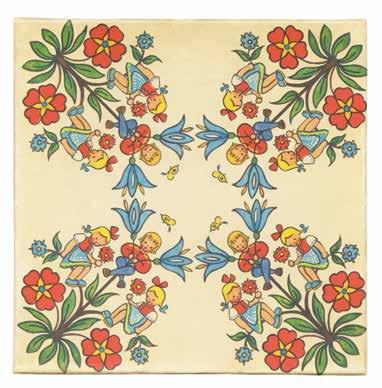

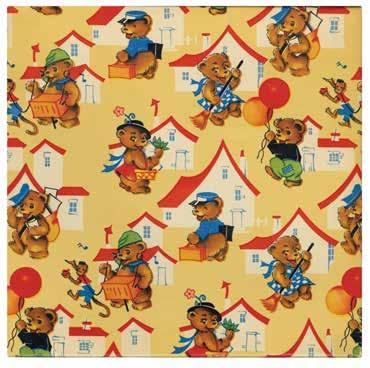

this is a feel-good book for these very stressful times. It will conjure up memories of bygone days when little girls and boys played with homemade rag dolls and had their own “indestructible” muslin ABC books—delightful reminders of more innocent times when “B was for Bow-Wow” and “Q was for Quack-Quack.” Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, tens of thousands of handkerchiefs were created with images of circus scenes, nursery rhymes, toy soldiers, teddy bears, bunnies, kittens, and puppies. Fabrics designed especially for kids ranged from charming figures of Victorian children based on Kate Greenaway illustrations and printed on upscale cloth to novelty patterns like faux-patchwork (called “cheater cloth”) on feed and flour sacks.

The common thread weaving through this book is cotton cloth. Everything pictured—piece goods, feed sacks, handkerchiefs, cut-and-sew dolls, fanciful bibs, muslin and linen books— is made of cloth, especially printed cloth dating from the late 1800s to the 1960s. Readers will recognize playthings and clothing that their grandparents might have had—or dolls and textiles from their own childhoods. And everyone, including the author, will find something they wished had been in their own toy box.

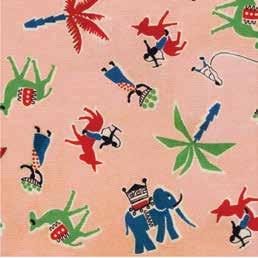

Some might wonder why there are not more items that specifically relate to African American, Latino, or Asian American childhood. During the time period covered in this book, white American culture was dominant. Textile printers produced patterns for this group and seldom for any other. While they printed fabrics with what the industry termed “ethnic” motifs, such as sombreros, cacti, and burros for “South-of-the-Border” or scenes

with paper lanterns, pagodas, dragons, and kimono-clad figures for “Oriental,” these were marketed to a general audience. African American store-bought cloth items were primarily dolls, including topsy-turvy dolls and cut-and-sew advertising premiums. Many of the latter tended to be stereotypical, like the Aunt Jemima’s brand Pancake Flour cutout dolls introduced in 1909 that depict Aunt Jemima and members of her family. Homemade African American rag dolls were far more abundant, judging from how many still survive.

Creating this book has brought me back to my roots as a child growing up in Connecticut during the late 1940s and ’50s. I have discovered picture books that I would have loved back then, for example, Howard R. Garis’s Uncle Wiggily series, Eulalie Osgood Grover’s Sunbonnet Babies’ Book, Johnny Gruelle’s Raggedy Ann Stories, and Carmen L. Browne’s beautiful illustrations for Come Play with Me and Sunny Rhymes for Happy Children by Olive Beaupré Miller. My favorite book as a child was the edition of A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson with illustrations by Jessie Willcox Smith. Its poems and pictures transported me to far-off lands and secret gardens where:

I have just to shut my eyes

To go sailing through the skies—

To go sailing far away

To the pleasant Land of Play

—ROBERT

LOUIS STEVENSON, “THE LITTLE LAND,” 1885

Late in my life, I grow fond of the Uncle Wiggily cloth rabbit shown in this book and, once again, hold my own Raggedy Ann doll, a gift from my grandmother when I was a little girl. The puppy hankie on page 109 (fig. 5) was found in the back of my bedroom dresser, and some of the merit badges shown on page 125 are ones that I earned as a Girl Scout. I have greatly enjoyed the chance to experience a second childhood while creating this book and hope the images illustrated will evoke pleasant childhood memories in others.

Susan Meller Berkeley, California

most of us have memories, conscious or not, of the first patterns we noticed in our young worlds. One such memory for me is of the 1950s wallpaper in my parents’ Chicago bedroom, where I was required to try to nap most afternoons of my preschool years. It was a Calder-esque mobile pattern on a dark brown ground. I found it fascinating to stare at and felt challenged to construe the possible meanings of the abstract shapes.

Many years later, my own children remember designs as diverse as bedroom curtains inspired by a Victorian-era toile with a scene of well-dressed children playing at the seaside a nd a crocheted blanket full of patterned openings that created a “comforting veil” for my younger daughter when she held it between her face and the light. She even claims to have a very early memory of the floral blouse her mother wore while breastfeeding her. My older daughter remembers the pink-and-blue floral sheets on her parents’ bed. She remembers the polka dots she saw on her “working” visits to the Design Library, and she proudly remembers the stacks of designs that I let her remove—based on her taste alone—from a large swatch book. The next day I presented them to the GAP Kids team as designs chosen by my five-year-old, and the professionals looked through them with renewed interest.

For so many of us, there were patterns on flannel blankets that warmed, on hankies that were gifted, and on printed cloth that was used to fashion our earliest clothing. In a large family like mine, I could track my young self’s patterns as they were handed down to my six younger siblings. These remembered fabrics produce waves of nostalgia. Like pop music for teenagers, they conjure up the times that were meaningful for us. They remind us of how we’ve grown and of how we may cherish our hard-won sophistication. But equally, there is a sophistication contained in many of these “Remnants of Childhood.” We must allow a suspension of disbelief to let in the wonderment of animals dressed up and cavorting like proud humans at an idealized fun fantasy party. We may experience a bold desire to join the circus or a call to duty as a scout or cowboy; we may get a message of overt

parental wisdom coupled with lessons in natural history or a fascination with the thinly veiled pathos of many common nursery rhymes. There is an attraction to these patterns that allows children to escape to a place where they feel they belong.

Susan Meller has made serious, beautiful, and in-depth additions to our awareness of the textile design universe. Textile Designs: Two Hundred Years of European and American Patterns for Printed Fabrics (1991), Russian Textiles: Printed Cloth for the Bazaars of Central Asia (2007), Silk and Cotton: Textiles from the Central Asia that was (2013), and Labels of Empire: Textile Trademarks. Windows into India in the Time of the Raj (2023), all have opened previously unknown worlds to scholars and laypeople alike. And now with this splendid new volume, Susan Meller continues in her mission to lead readers to new levels of appreciation via delightful images and clear, elucidating text.

Remnants of Childhood takes us by two hands to gently dance with our own young selves. As adults, we may feel naïveté has been lost, but we can still catch a glimpse of our innocence skipping playfully through the pages of this book.

Peter Koepke

The Design Library Hudson Valley, New York

by the end of the 19th century, Western society had begun to view young children less as little adults and more as a class of people within the general population who had their own requirements that were not being addressed. Social reformers published and preached the need for child labor laws and public education. People were encouraged to place less emphasis on a strictly moralistic upbringing and to allow children more freedom to play. Little boys could be mischievous, ride tricycles, and get their playclothes dirty. Little girls, released from bustles and layers of heavy petticoats, could roll hoops and jump rope. By the 1920s, changes in fashion and the ubiquitous whites of earlier eras had given way to more practical clothing in a range of colors and a profusion of printed patterns designed especially for children.

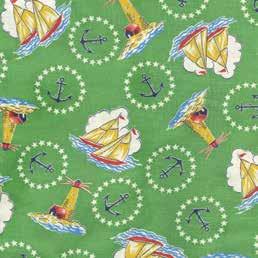

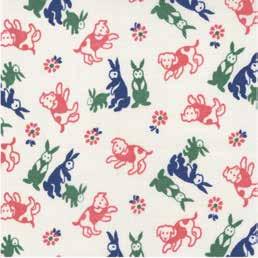

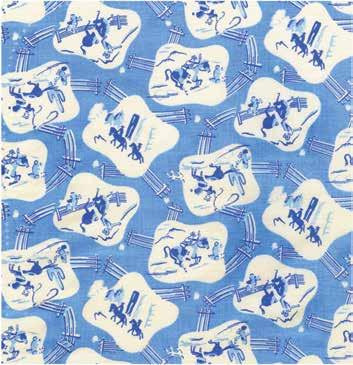

Late 19th- and early 20th-century juvenile patterns were usually mass-produced on cotton cloth by roller-printing machines. If figurative, they tended to be realistically rendered and were often scenic in nature. As the decades progressed, the images became more whimsical, and many cute designs were created specifically for very young children. Rompers, sleepwear, and sunsuits might have ducklings, bunnies, or puppies scampering over them. Indeed, baby animals were favorite motifs for little boys and girls. For older boys, there were trains, boats, cowboys, and toy soldiers. Older girls were treated to “Mommy’s little helper” images, Sunbonnet Sue, and floral calicos. Circus scenes were popular with all kids and usually larger in scale for use as home-furnishing fabrics—as were novelty chintz designs, which were a favorite for curtains in children’s rooms.

With the birth of Micky Mouse in 1928 and the subsequent parade of other characters created by Disney, textile manufacturers began to license images from popular culture for use in their products. Each decade brought its own cultural icons into kids’ rooms and onto their clothes—Howdy Doody, Barbie, Sesame Street, Star Wars, and on and on. But for babies and toddlers too young to choose their own prints, parents could still find charming patterns based on more innocent times.

cloth books evolved in much the same way as children’s handkerchiefs. The earliest paper books were small, crudely block-printed booklets called “chapbooks.” First made in 16th-century Europe, they continued to be widely available into the mid1800s. Selling for a halfpenny to a few pennies each, they were a form of popular culture with subject matter ranging from moralistic to bawdy. They also provided lessons for children—teaching them their ABCs, history, and Bible stories.

As the 19th century progressed and more people were able to read and afford books, chapbooks gave way to inexpensive bound books. Along with the evolution in reading habits came a transformation in society’s view of children, particularly among the middle and upper classes. Children began to be thought of as individuals whose daily lives would be enriched by the pleasures and not just the lessons that books could provide. Like kids’ handkerchiefs, books too became fun! As publishers began to print more and more books for children, they soon realized the need for sturdier copies that could withstand the wear and tear inflicted by little hands. By the late 1880s, McLoughlin Bros., Inc., of New York had begun to produce chromolithographed picture books on linen.

Other prolific publishers of children’s cloth books were Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd., London, the Dean’s Rag Book Company Ltd., London, and the Saalfield Publishing Company, which was founded in Akron, Ohio, in 1900. Dean’s liked to say that children “wear their food and eat their clothes,” hence the need for “hygienic” cloth books. While the back cover of some of Saalfield’s muslin books bore this little verse:

They may be washed

And the colors will not run,

A child can chew them

And have lots of fun.

Production of cloth books continued until World War II, when rationing of cotton fabric curtailed supplies and publishers turned instead to thick paper with a textured surface resembling linen. They called these books “linenettes.” However, many cloth books, the “rag” books of yesteryear, survive today as proof that they were indeed “indestructible.”