3. THE PRACTICABLES

Le Havre (1969)

(1970)

Nevers (1971)

Amiens (1972–1973)

Mâcon (1973)

Douai (1973)

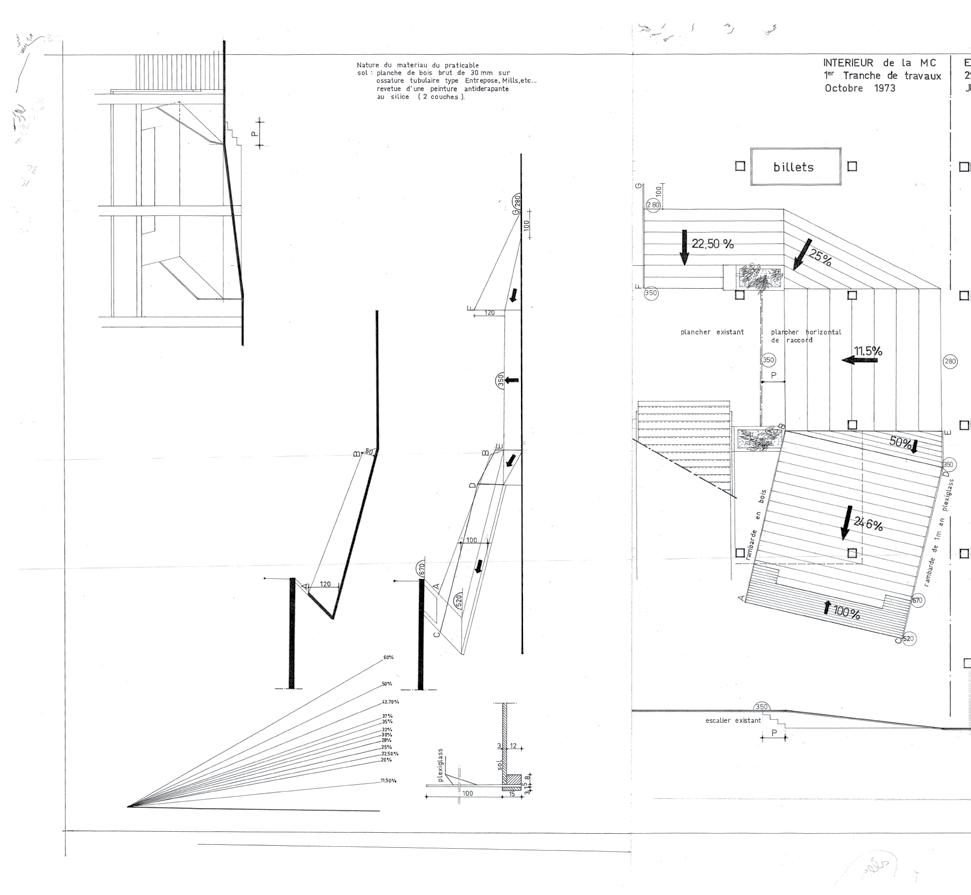

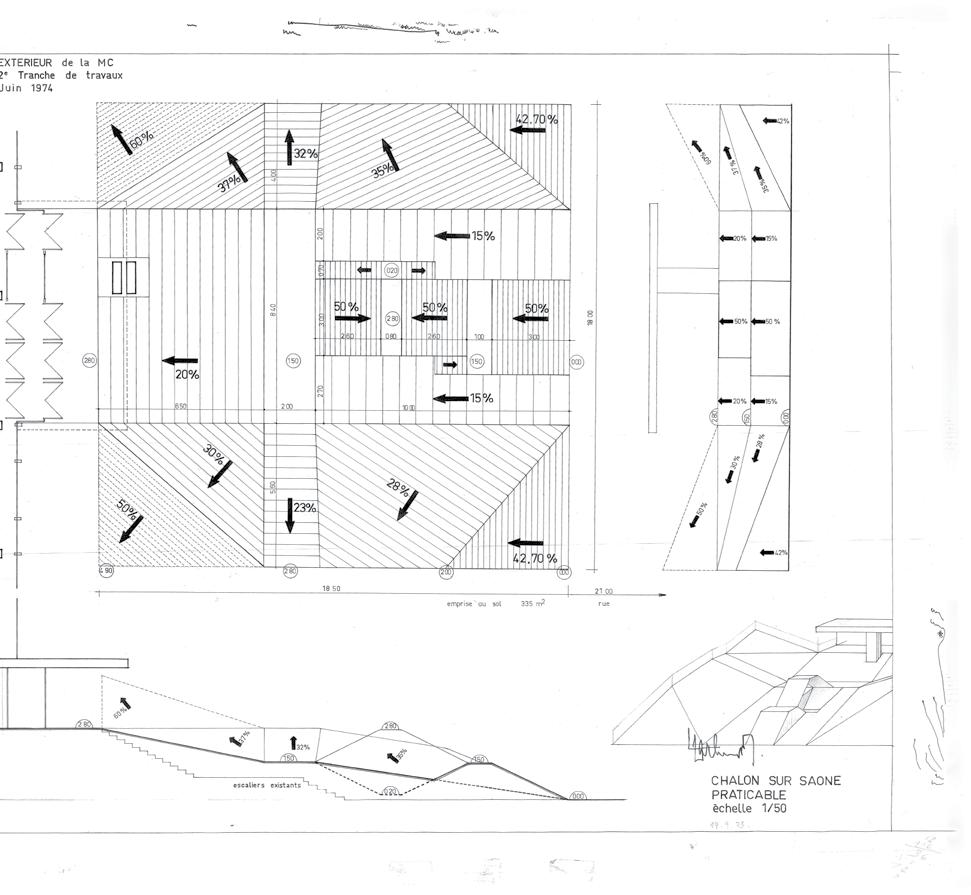

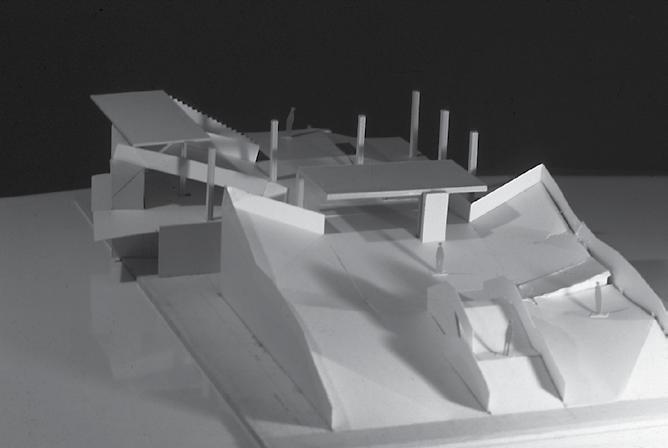

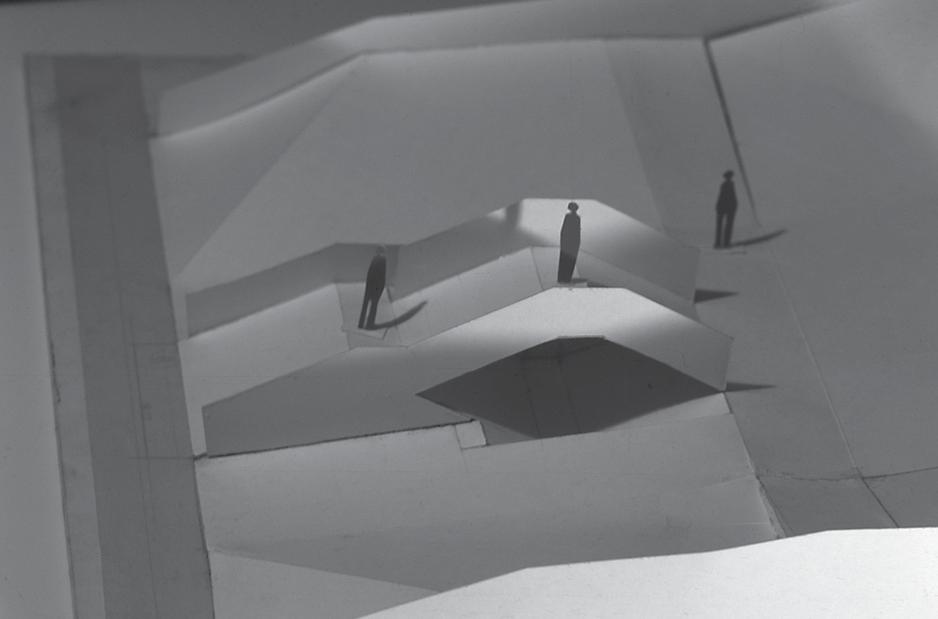

Chalon-sur-Saône (1973)

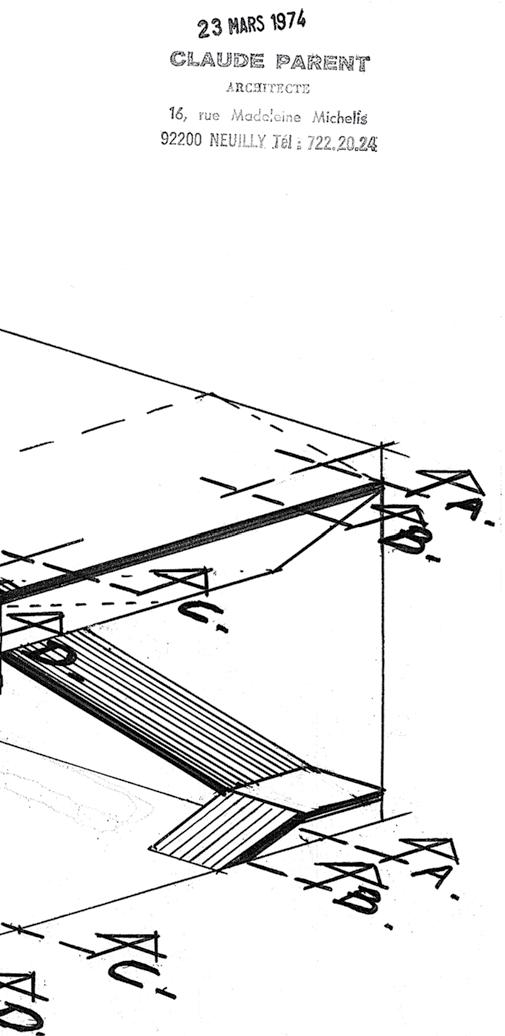

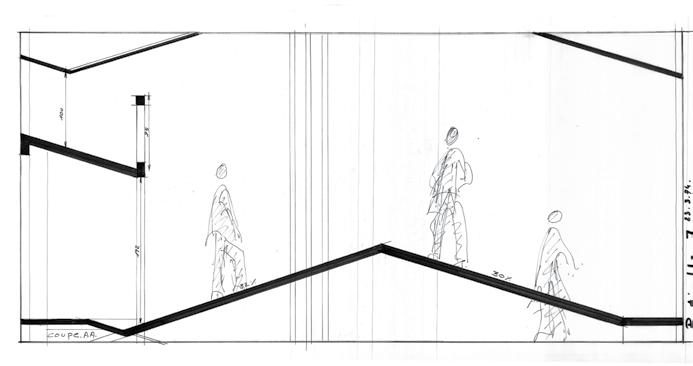

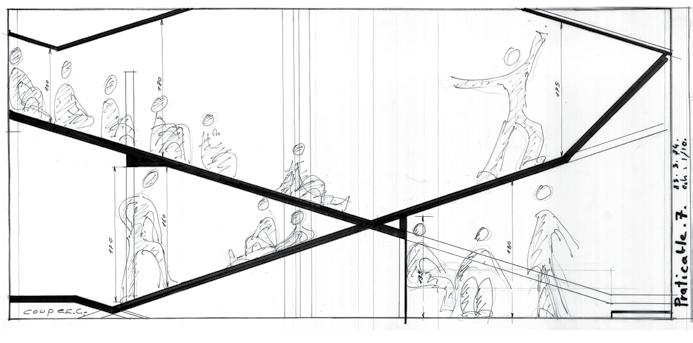

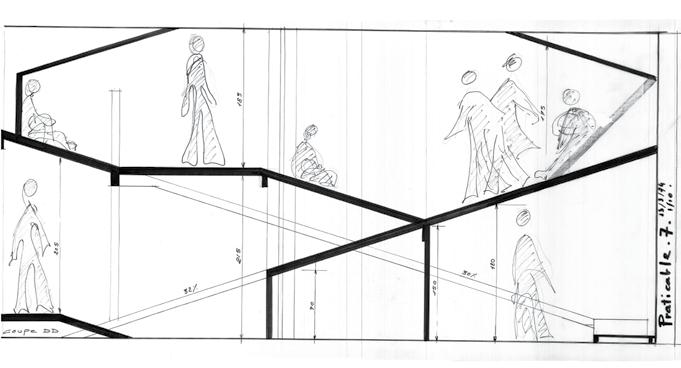

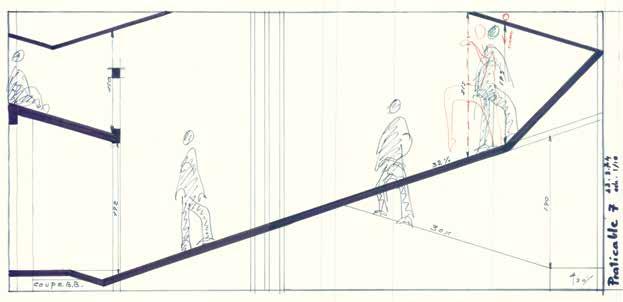

Praticable no. 7 (1974)

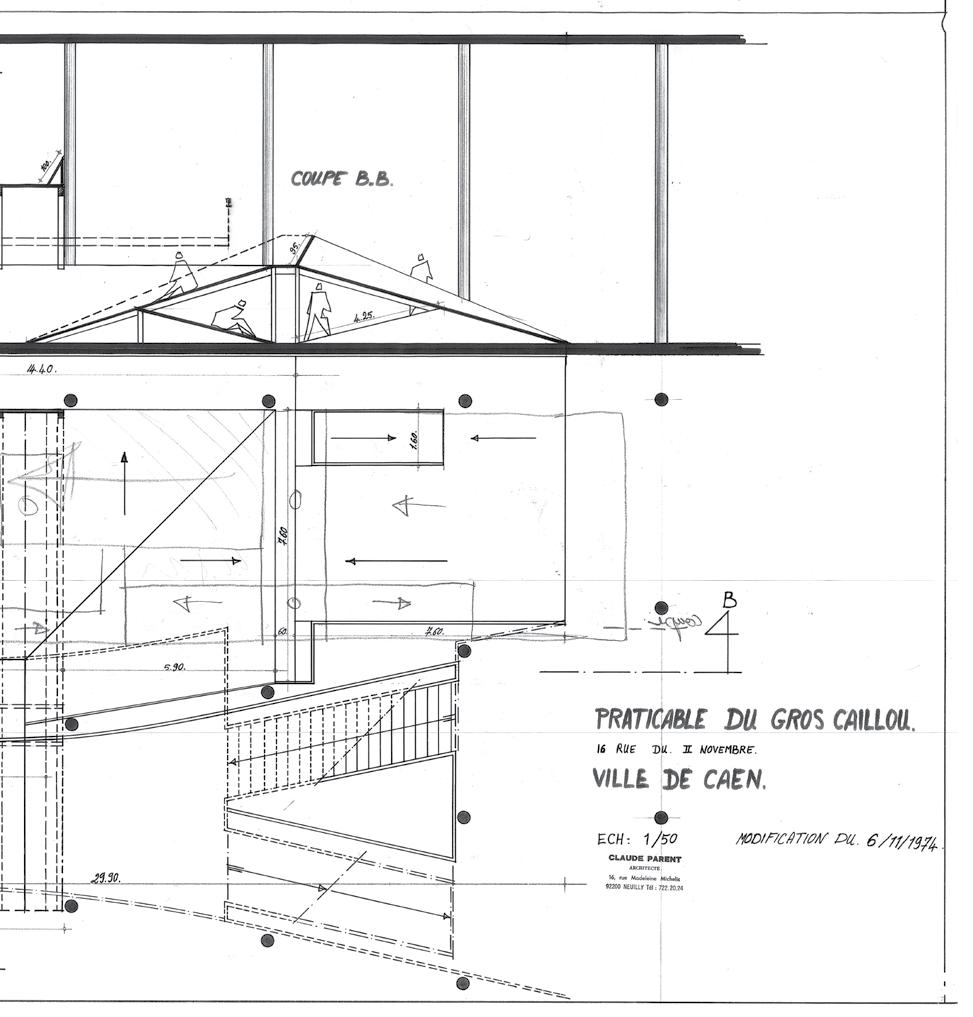

Caen (1975)

Le Havre (1969)

(1970)

Nevers (1971)

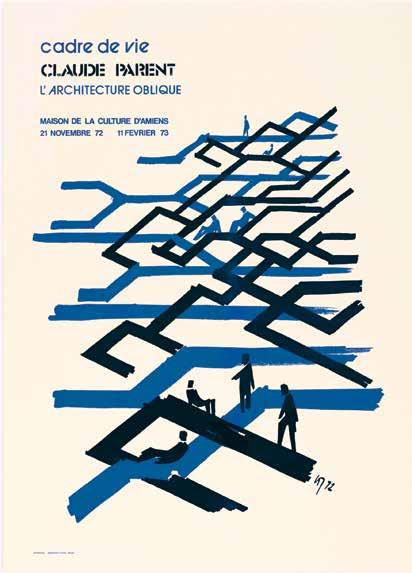

Amiens (1972–1973)

Mâcon (1973)

Douai (1973)

Chalon-sur-Saône (1973)

Praticable no. 7 (1974)

Caen (1975)

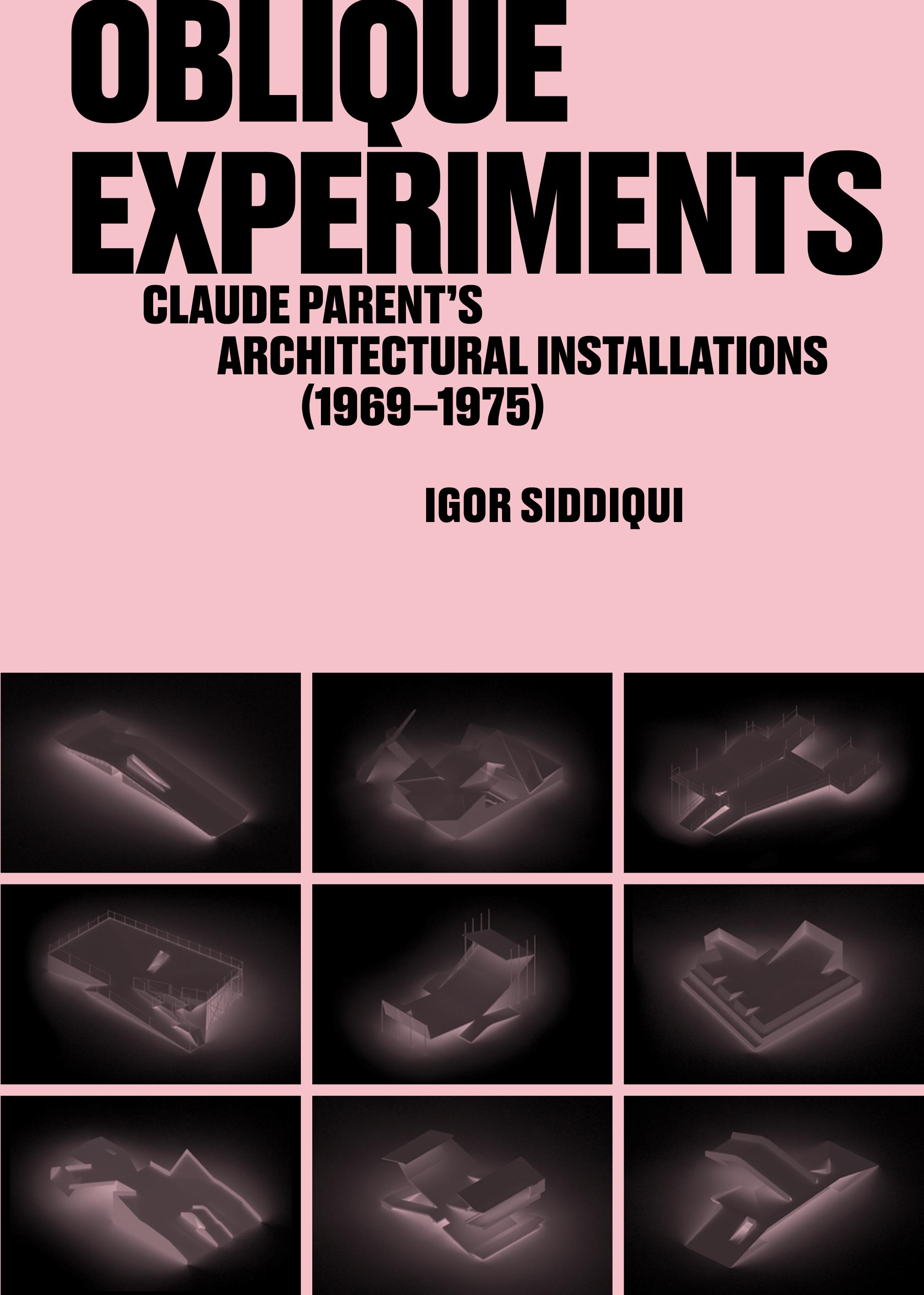

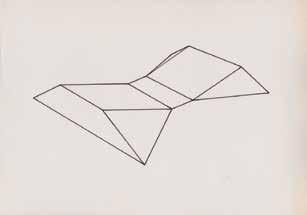

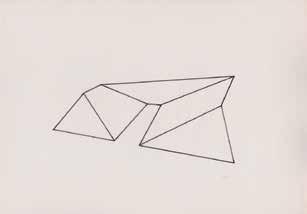

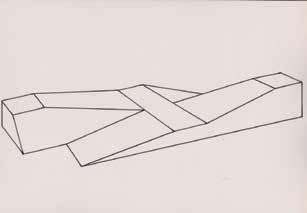

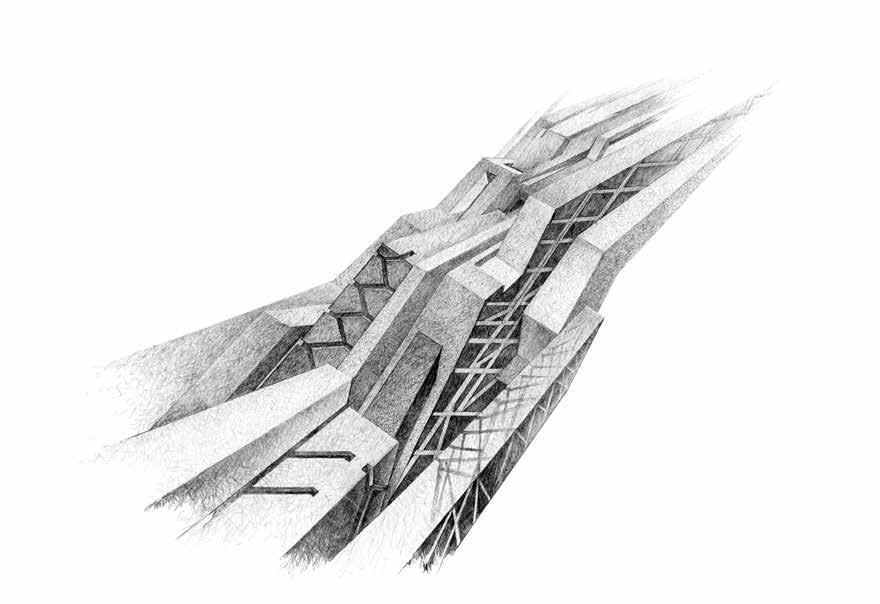

Sketches from the CPA 473 folder Dessins utopiques de Claude Parent (1966–1982), Fonction oblique: Vivre à l’oblique (1973–1975 ), part of the Claude Parent Archives housed by the Kandinsky Library at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

> Sigurður Guðmundsson, Study for Horizon, 1975.

CPA 473: The call number for one of nearly five hundred folders that comprise Claude Parent’s digitized archive housed by the Kandinsky Library at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Part of a larger section dedicated to the French architect’s graphic works in the archive—identified as dessins utopiques, or utopian drawings—the folder contains photographically reproduced sketches of imagined spaces shaped by angled floors, walls, and ceilings. Titled according to daily activities like work, play, and eating, and populated by scale figures suggesting such uses, the hand-drawn perspectives depict interior environments in which architecture acts as furniture and vice versa. These archived documents, dated between 1973 and 1975, are a record of Parent’s exploration of oblique living, that is, his total vision of life on sloped surfaces that contributed to his reputation as a radical architect.

CPA 473 contains evidence of Parent’s thinking about interiority, an aspect of his experimental architecture that was at times overshadowed by the monumental forms that emerged in many of his speculative drawings. Since this is one of the things that particularly interests me about his work, encountering these sketches was a step in the right direction for my research. Browsing through the folder for the first of many times, I eventually reached the last of the thirty-six images. In lieu of one more drawing, I was surprised to find another kind of image: a black-and-white negative of a photograph showing a man standing on a beach, his figure

juxtaposed against the flatness of the sea level in the background. Rather than standing upright his body slants forward, astonishingly parallel to the oblique angle of a wood post in front of him. A single line of text below the picture, “Study for horizon,” turned out to be its title, a self-portrait by the Icelandic artist Sigurður Guðmundsson from 1975.1

At first, I had no idea how the image ended up in Parent’s archives, much less in this specific folder. However, the fact that it did immediately made sense to me, almost as if it were a matter of fate. Someone, I guessed, must have been amused by the resonance between Guðmundsson’s tilted stance and Parent’s explorations of oblique architecture. Perhaps the artist and the architect’s apparently shared interest in defying the normative orientation of horizontals and verticals inspired someone to place the photograph among the collection of drawings, highlighting this observation. I later discovered a miniature reproduction of the same picture in Parent’s 1981 monograph Entrelacs de l’oblique, where, instead of being identified by title or author, its brief caption only notes that the artist in question participated in the Venice Biennale—conceivably the place where the architect first saw it.2 In any case, my unexpected encounter with this particular image, in this very folder, at this very archive, helped me grasp the sense of serendipitous displacement—or the fortuitous outcome of being out of place—that ripples through the various layers of my research that became this manuscript.

For one, unexpectedly finding within Parent’s vast oeuvre a small opening (Guðmundsson’s photograph) that leads to a view of oblique living beyond architecture, encapsulated in a single moment the kind of relationship between specificity and expansiveness that had already existed in my own engagement with the architect’s work. The truth is that while my initial interest in oblique architecture stemmed from the challenge that it posed for building interiors, its underlying theoretical principles simultaneously prompted me to contemplate the potential of obliqueness not only as it applies to inclined ground—which is how it appears in most standard accounts of Parent’s work—but also, interpreted more broadly, as any vector whose direction deviates from an already established expectation, reference, datum, or norm. I was working through my ideas about obliqueness in relation to my own design practice, publicly lecturing and publishing on the subject as early as 2017.3 Such a path, I later realized, is not unlike the experience of looking through Parent’s sketches but somehow ending up following the lead of a misplaced picture.

I came to the Pompidou archive to see if I would find in Parent’s body of work the very thing that his buildings, drawings, and writing inspired me to look for elsewhere. Moreover, I sought to identify any overlaps between such expanded expressions of obliqueness and his oblique interiors, as if trying to posit a fraction of his practice into a vast landscape formed by broader interpretations of his theoretical principles. These objectives led me to Parent’s architectural tour of France from the early 1970s, throughout which he designed a series of temporary interior installations as public explorations of oblique living. As the book’s primary subject, this episode of his career captured what I consider to be an oblique approach to practice—the tour was, in a sense, very much a detour—while also yielding a series of interior experiments.

As an architect, I typically spend most of my time in the design studio rather than in the archive—the space of research where

I eventually arrived through my design practice, as if following the oblique path of a wormhole. The memory of coming across Guðmundsson’s image stayed with me in part because its placement reminded me of my own position in the archive, both out of place and with a purpose. The artist’s posture in the photograph likewise embodies a mixture of adaptation and defiance, a type of productive displacement that defines oblique practice. And if my own departure from the comfort zone of my usual habitat in order to pursue this research was in this sense oblique, so were Parent’s traveling experiments during which he left his Parisian atelier behind in order to figure out an alternative form of architectural practice in a different kind of environment. Along the way, he challenged himself to redefine not only the role of architecture but also that of the architect. If the transformed silhouette of such a figure were visible, it would likely appear no less oblique than his architecture.

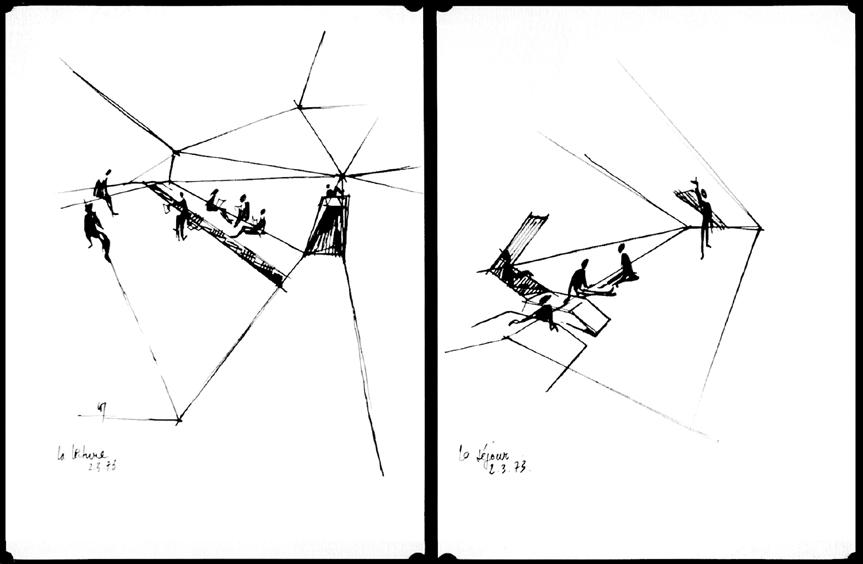

Parent testing a mocked-up slope with his collaborators while designing the oblique installation for the 1970 Venice Biennale.

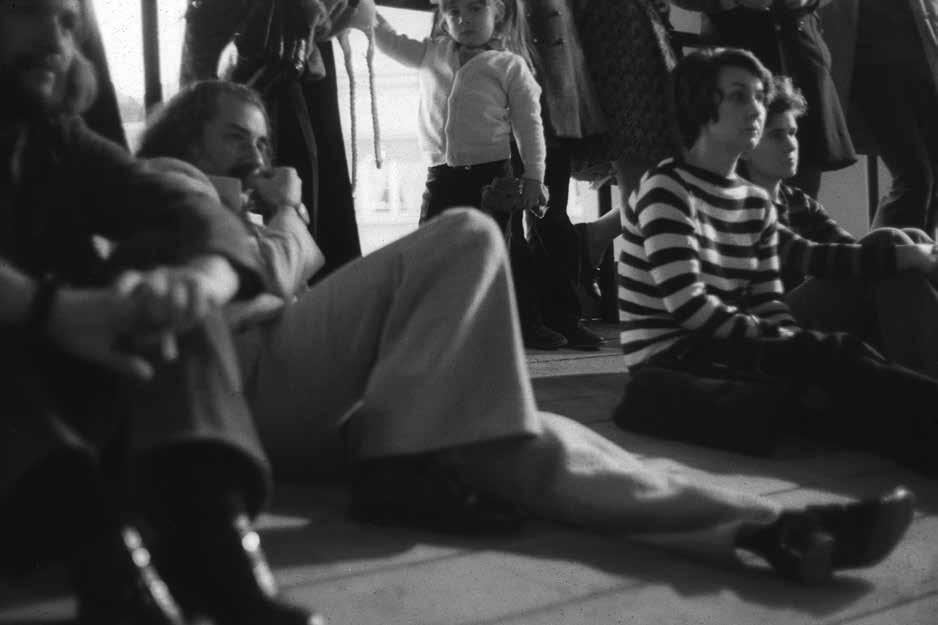

> Parent sitting on the sloped floor among the audience in Amiens, c.1973.

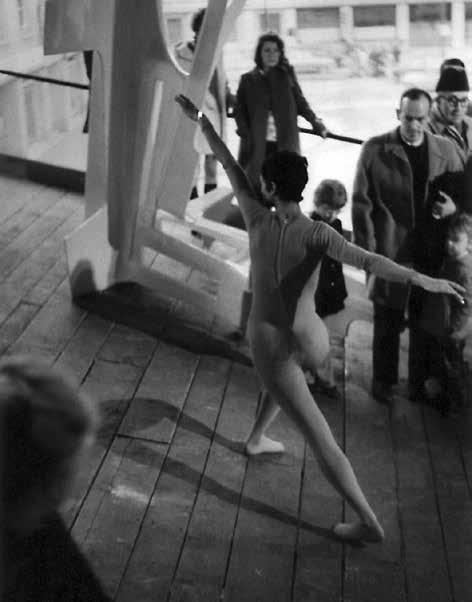

Suppose that most of life took place on sloped surfaces instead of flat ground. Imagine buildings without any level floors. How would it feel to live in an environment that inspires movement even in moments ordinarily associated with rest? What if everything straight were oblique? Such speculations invite an engagement with the work of French architect Claude Parent (1923–2016) who in the 1960s started exploring the use of angled planes in reshaping both architecture as a habitable terrain and its effects on those who inhabit it. As part of his ongoing investigations of such an architecture—which he pursued through various modes of practice, including writing, drawing, and building—Parent designed a series of temporary installations with which he intended to introduce his avant-garde ideas to popular audiences. Produced between 1969 and 1975, these pop-up architectural interventions—referred to, in French, as praticables—were designed for various sites throughout France (as well as featured at the 1970 Venice Biennale), usually accompanied by related public programs. In addition to helping promote Parent’s theories and bringing them closer to reality, these itinerant endeavors served as a form of observational research through which the architect sought to gain insight into how people responded to his work. The installations were thus instruments for imagining, questioning, feeling, testing, and verifying the potential of life at oblique angles. Oblique Experiments: Claude Parent’s Architectural Installations (1969–1975) is the outcome of collecting these objects and examining them as a cohesive series.

In French, the word praticable stands for a floor or platform on which an activity occurs, such as a theatrical performance or gymnastic routine. As a matter of décor or scenography, a praticable is also an element that exists three-dimensionally rather than being painted on or depicted through a flat image. The adjective form of the word references something

passable—like a path—or, in another sense, something that is possible to put into practice, as in “feasible” or “achievable.”1 The equivalent English term used to describe theatrical props and scenery is “practicable,” although the adjective’s abbreviated version, “practical,” is more common today.2 In the book Practicable: From Participation to Interaction in Contemporary Art, the adjective “practicable” qualifies works of art that are actualized by practice, while its editors also acknowledge the usefulness of the noun form as it exists in French “insofar as the practicable is a potential site of action or performance.”3 Parent used the noun praticable as a name for his temporary installations, an appropriate word choice not only because they were manifestly stage-like, but also given that their primary purpose was to test the feasibility of his theoretical ideas. The practicables—as they will be referred to throughout this book, with the added English “c”—were, in other words, a platform for putting into practice a theory of architecture.4 This book brings together nine of these installation designs— encompassing the extent to which these works were originally documented—each situated in its own particular context yet part of what is, in effect, an iterative series of objects and interrelated events. The book contributes to the existing scholarship on Parent as the first publication to date entirely dedicated to these projects and constitutes their first full compilation in any format. Also included in this study is the necessary background for understanding the development of the practicables as part of the architect’s larger body of work and in relation to the particular conditions that enabled, and at times constrained, their realization. Using

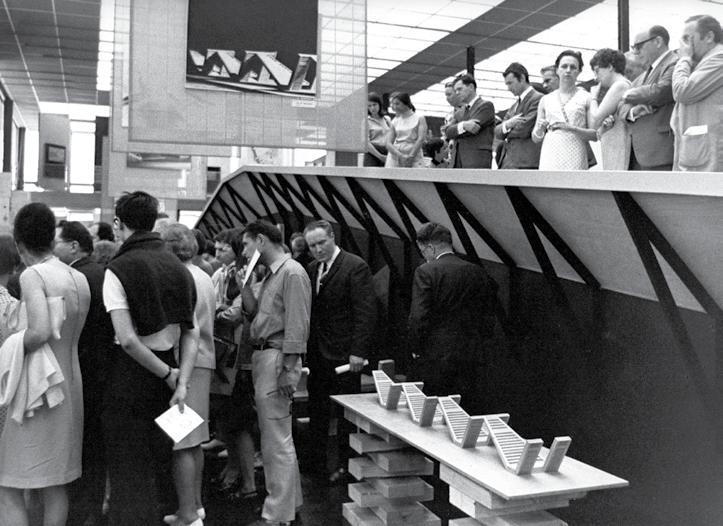

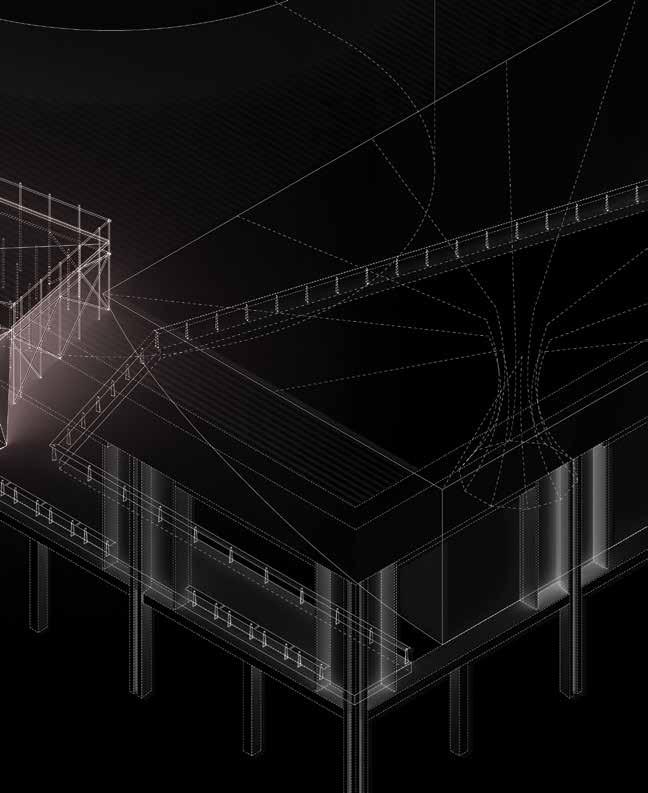

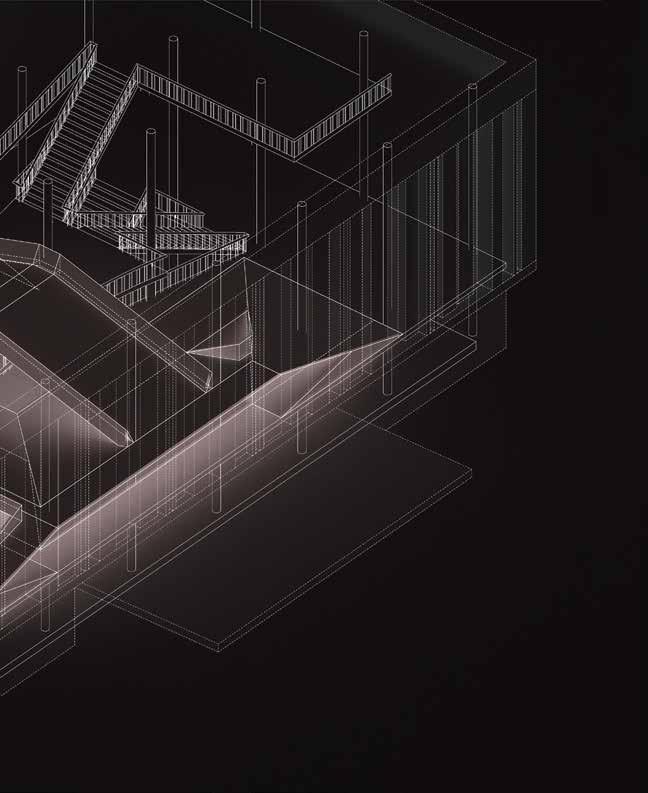

materials, fieldwork, as well as existing publications as a basis for in-depth documentation, analysis, and interpretation of this work, my research brings overdue attention not only to the practicables as a series of compelling architectural objects but also to the social and spatial contexts within which they came to exist. As part of this research, the practicables were reconstructed digitally, resulting in an original set of architectural representations that enables us to see them in a new way. In addition to archival photographs, drawings, pamphlets, posters, and other graphic materials—many never before published—these new drawings present with increased consistency and precision each of the individual schemes, while also enabling them to be seen as an iterative, and thus comparable, series of design experiments.

The purpose of this book is not to echo the architect’s advocacy for life on sloped ground, nor is it—as has already been done elsewhere—to perpetuate any particular predispositions related to architectural form or style. Instead, the intention here is to examine how the sum of this work serves as a model for a particular form of experimental practice that may be useful, as a matter of precedent, to contemporary designers. Written from an architect’s perspective, Oblique Experiments captures the intersection of visionary speculation and public engagement in Parent’s work that resonates with potential and excitement more than fifty years after its realization. By examining these acts of experimental architecture from a contemporary perspective, the book creates a space for two particular themes to unfold throughout its chapters. First is the role of interiority in these experiments, and second is the appropriation of an expanded definition of obliqueness as an approach to practice in and beyond architecture. In sum, therefore, the book treats Parent’s practicables as an iterative series of experiments rather than one-off projects; it brings out the underlying condition of interiority and presents it as an essential aspect of Parent’s work and a critical part of what makes the practicables experimental; and it considers obliqueness as more than either a formal architectural strategy or a literal prospect of life on slanted ground, whereby Parent’s experiments serve as a prompt for imagining and articulating other potential oblique orientations in contemporary practice.

An architect whose prolific practice began in the early 1950s and evolved over six decades, yielding numerous buildings, projects, and publications, Claude Parent remains best known for

his explorations of inclined planes according to the theory of the oblique function. La fonction oblique, as it is referred to in its original French, was initially the result of Parent’s productive, albeit relatively brief, collaboration with Paul Virilio, with whom he cofounded the group Architecture Principe in the mid-1960s.5 Virilio, who later emerged as a leading theorist and philosopher, was a decade younger than Parent and, at that time, in an early stage of what turned out to be an auspicious career. The group— part intellectual think tank and part architecture office—advocated for the use of inclined planes in buildings instead of level floors, a radical proposition with an intended impact on all scales of human habitats, from individual bodies to entire cities. According to Parent and the group, sloped surfaces inspire people’s active engagement with the built environment, the anticipated bottom-up effect of which was to be architecture’s renewed social relevance.6 By provocatively proposing to place all of life’s activities on oblique substrates, they envisioned the future of architecture free of orthogonal form as well as of strict distinctions between program and circulation, that is, between predetermined uses of space and the necessary movement through it.7 Architecture Principe’s eponymous manifesto-magazine captured a desire to emancipate architecture and its inhabitants from the outdated orthodoxies of modernism, while also projecting an alarming sense of anxiety and doom about the status quo.8

The group’s principal built work is the Church of St. Bernadette of Banlay in the central French town of Nevers, whose angled design, constructed between 1964 and 1966, was integral to the development of the oblique function as a theory. Parent remained preoccupied with the oblique function even after the group stopped functioning as an entity, producing a series of other related designs and texts. His sole-authored, self-published booklet Vivre à l’oblique from 1970, for example, was written as a manifesto in its own right and served as a key theoretical reference for his practice.9 He continued testing the feasibility of living with oblique architecture by attempting to implement its principles in various projects as well as by engaging with the people for whom they were intended. Temporary architectural installations and public engagement were central to this exploration. In the book’s first chapter, “Obliqueness,” I provide a detailed account of the trajectory that links Architecture Principe’s accomplishments as a group with Parent’s subsequent development of the practicables as a series of experiments.

For much of his ambitious career, Parent maintained a reputation as an outsider among the French architecture establishment while remaining relatively unknown outside of his native country.10 All of his surviving built works are located in France and many of his texts continue to be only available in their original French versions. In 1996, coinciding with the thirtieth anniversary of the Nevers church, the work of Architecture Principe received a burst of international attention prompted by a prominent feature in the exhibition BLOC: Le monolithe fracturé at the Venice Biennale of Architecture.11 Installed at the French Pavilion, the show introduced the Church of St. Bernadette of Banlay to contemporary audiences as an exemplary postwar building, while foregrounding Parent as a key figure in the realm of experimental architecture.12 Along with the staged “rediscovery” in Venice of the church and its creators, a reissue of the group’s complete set of nine magazine issues took place the same year—including an English translation of the original texts.13 Around the

same time, another English-language publication, titled The Function of the Oblique: The Architecture of Claude Parent and Paul Virilio 1963–1969 and released by the Architectural Association in London, also helped make the group’s work available to a new generation of architects and students, even though it has long since been out of print.

A handful of other books about Parent have been published in English since then, including a 2010 bilingual French-English monograph focused solely on the church in Nevers;14 a book on Parent’s collaboration with the artist Yves Klein published in 2013;15 the 2019 Claude Parent: Visionary Architect, whose primary focus is his extraordinary drawing practice;16 as well as the 2020 collection of interviews and sketches titled Oblique Time with Claude Parent. 17 Although these publications encompass only some parts of Parent’s oeuvre, they do give English readers insight into the oblique function as a theory and its manifestation in projects like the church in Nevers. They also provide useful context for understanding the importance of collaboration in his practice as well as the influence of his experimental work on subsequent generations of like-minded architects. With the exception of Oblique Time with Claude Parent, however, none of these texts sufficiently focus on his oblique installations. In many cases, they are not even mentioned.18

Two particular publications in the French language that are still in print cover more ground in this regard: the 2010 retrospective monograph Claude Parent: L’œuvre construite, l’œuvre graphique and the 2022 Claude Parent: Les desseins d’un architecte. Both offer comprehensive considerations of the architect’s entire career, including the period between the late 1960s and mid-1970s, when the practicable emerged as an important experimental device. The former is a catalog accompanying a major exhibition of the same name at the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine in Paris, a thorough and overdue overview of Parent’s entire career published

several years after his office closed.19 The latter, written by the architectural historian and preeminent Parent expert Audrey Jeanroy, is in effect a critical biography in which the architect’s creative output serves as the material for understanding his lifelong creative and intellectual evolution.20 Despite their scope and depth, even these two indispensable pillars of scholarship on Parent’s work only partially convey how these experimental installation designs collectively form a cohesive body of work.21

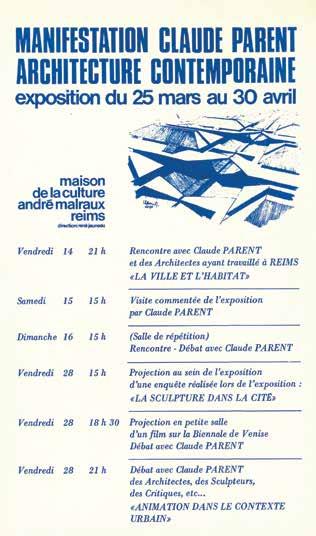

Despite the differences that distinguish them from one another, commonalities emerge across all the practicables allowing them to be seen as an interrelated series. One way they are brought together is via the architect’s traveling tour across France (including a stop at the country’s own pavilion at the Venice Biennale) whose itinerary consisted of sites for which the installations were designed. With some exceptions, the practicables were generally intended to be temporary in nature and made of construction materials like scaffolding and wood planks. Most of them were built inside existing buildings; several occupied the cultural centers that proliferated throughout postwar France known as maisons de la culture, which roughly translates as “houses of culture. ” The establishment of such centers was part of the national effort to decentralize and distribute access to cultural resources away from the capital, thanks to which most of the practicables landed in smaller provincial cities like Amiens, Caen, and Douai. Beyond their inherent functionality as sloped stages or ramps, the installations were often conceived as integral elements of thematically related public programs, including exhibitions, performances, lectures, and workshops. The organization and development of such projects usually involved artists representing different disciplines while, in addition to engaging popular audiences, Parent often realized the practicables with teams of local partners. The installations were in this way both a device for, and a product of, collaboration. In Chapter 2, “The Tour,” I examine the itinerary of Parent’s travels as well as the conditions that made the practicables possible. This includes the nature of the public institutions that served as hosts and coproducers, along with the underlying politics of the post-1968 era that shaped such institutions and their role in French society.

In a number of the cities that were part of Parent’s Tour de France, public programs took place even if the practicable intended for that particular site ultimately did not get built. Whether fully realized or not, the apparent role of each design shifted depending on its context. In some cases, the purpose was to help display artifacts such as drawings, photographs, and models as part of an exhibition; in others, it was the installation itself that was on display and whose completion was conceptually contingent upon the presence of people rather than other artworks. Some practicables served as temporary venues tailored to the accompanying cultural programs; in other instances, especially the unbuilt designs, their assigned role was more permanent, a type of corrective measure prompted by the limitations posed by existing architecture.22 Of the nine installation schemes documented in this book, five were constructed and, prior to their eventual demolition, in some way photographed; none outlived their ephemeral purpose.23 The designs of the other four schemes—each unrealized for different reasons— are known thanks to surviving drawings, models, and photographs of

discarded models that have been archived at the Kandinsky Library of the Pompidou, the Institut français d’architecture, and the family-managed Claude Parent Archives in Paris, as well as the FRAC Centre-Val de Loire in Orléans.

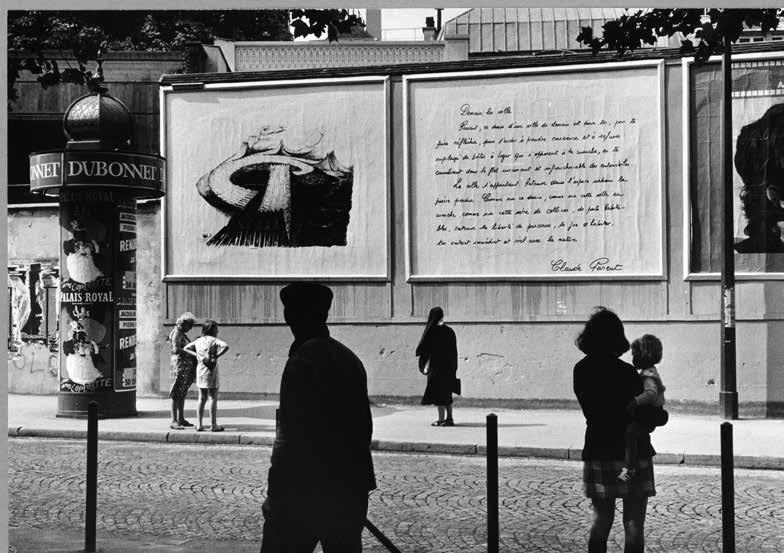

Since their realization more than half a century ago the practicables have been presented and talked about in different ways but never fully compiled as a series. Some are well known among certain audiences, while others remain obscured by various factors, including their uneven surviving documentation. Individually, each practicable varied in complexity and resolution, with some of the larger and architecturally more elaborate ones simply known as standalone projects. Elsewhere, the practicables have been associated with Parent’s public poster campaigns—during which he plastered the streets of Paris with oversized copies of sketches and written provocations about the future of architecture—bringing to light the architect’s inventive strategies for engaging the public. However useful a role they play within such narratives, the contribution of such accounts to a more nuanced, detailed, or situated understanding of the practicables is limited. As objects, the installations—whether constructed at full scale or conveyed through drawings and models—capture the specificity of engagement in space, with people, and through architecture that is difficult to convey solely through generalizing narratives. Of interest and value, in other words, is grasping them as situated objects. The third chapter—the book’s core—collects them all under the self-evident title “The Practicables.”

Organized chronologically, the chapter recreates the itinerary of Parent’s tour, starting with Le Havre in 1969 and ending in Caen in 1975. By combining detailed narratives with existing photography, drawings, promotional graphics, as well as newly produced drawings, I reconstruct each practicable

as an object embedded in a specific context, which in addition to existing architecture and urbanism included various public programs engaging a range of stakeholders and collaborators.

The practicables were experimental devices that are, from a contemporary point of view, easiest to describe as installations. This is how they are referred to throughout the book—starting with the title. On its own, however, the word “installation” fails to convey the practicables’ objecthood with enough specificity, individually or as a series. Meanwhile, despite their relative simplicity and raw execution, Parent’s experimental installations can be seen as many things at once. Designed by an architect, the floor-mounted assemblies of ramps, platforms, and landings were ephemeral works of architecture. Not unlike buildings, these architectural fragments were situated in specific contexts without which they were incomplete, even if their individual structure, or overall form, could provisionally be extracted as a stand-alone figure. Their partial, temporary, and exploratory character made them akin to improvised full-scale models used for quickly testing an idea or mocking up an architectural condition so that it might be further studied. The practicables were, as such, the working instruments of an ongoing experiment. In some of the iterations, the inclines were painted in bold blocks of color, envisioned by the artist Andrée Bellaguet as large three-dimensional canvases made to be walked on. In this sense, the practicables appeared as devices for the display of art as well as art objects in their own right, although it would ultimately be insufficient to refer to them as either exhibition designs or works of art. Moreover, true to their name and configuration, some appeared as scenic elements or served as performance stages, even if ultimately the objective of such obliquely staged theatrics was to find possible connections with, rather seek separation from, everyday reality.

The practicables were, in effect, site-specific furnishings sized to accommodate both resting in place and moving about, using public institutions as their support. Intended to occupy, augment, or otherwise intervene within existing buildings, they provided adjustment to the architecture that already existed and offered suggestions of what could be. Through the sum of such spatial undertakings, this series of oblique objects functioned as proofs of concept but were also leveraged as professional self-promotional materials wishfully tasked with reinforcing intellectual notoriety as well as attracting new commissions. In relation to each physical site as a container, they were the content, part of a larger composite of interrelated activities and actions—even if some of the practicables were only exhibited as design proposals, while others took place as full-scale constructions. Counting these multifaceted objects as constituent parts of a series is made possible by the overall itinerary of Parent’s traveling experiments as well as their oblique form. As an object, each practicable can as such be described as both experimental and oblique. Taking into account the various ways in which they took shape, the roles they played, and the contexts they engaged, however, also enables us to regard them, I argue, as interior objects. The book’s fourth chapter, “On Interiority,” considers how contemporary notions of the interior as both a spatial and subjective condition help reframe the practicables in relation to the development of Parent’s praxis. In this chapter, I explore the architect’s earliest period of practice, during which he refurbished quite a few interiors, as well as his writing on the subject of industrial design and decoration, followed by his

two domestic interiors designed according to the principles of the oblique function. Considering these pursuits allows us to grasp the significance of the practicables as interior objects that engage the public realm.

In his long out-of-print monograph Entrelacs de l’oblique from 1981, Parent dedicated a section, titled “Expérimenation, manifestation, participation,” to the practicables.24 While only thirteen pages long, it is likely the architect’s most complete published account of the installations as a body of work. Nuanced differences in meaning notwithstanding, the French title reads just as easily in English while also providing a useful vocabulary for distinguishing the variously intertwined aspects of the traveling installations from one another. Moreover, Parent’s choice of words prompts an explanation of how each term also appears throughout this book.

In architecture, experimentation generally refers to approaches to practice that challenge, and in some cases entirely circumvent, convention. In his 1970 book Experimental Architecture, Peter Cook considers experimental work to be driven by “the desire to undermine and explode all rival positions,” while also being charged with resisting the widespread “horrific mainstream” of the profession.25 Not unlike the provocative speculations produced by Cook’s avant-garde group Archigram in the 1960s, architectural experiments often come to life through drawing and image making. Such “visionary” or “paper architectures”—experiments in the form of purposely drawn unbuildable propositions—are part of a longstanding disciplinary tradition exemplified by the works of eighteenth-century figures like Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.26 Contemporary discourse on experimentation in architecture continues to evolve in response to a rapidly changing world, yet many of the core values associated with such modes of practice remain intact. Rachel Armstrong, researcher, scholar, and author of the 2019 book Experimental Architecture: Designing the Unknown, also considers experimentation as a visionary practice, while situating it as research “capable of developing alternative architectural paradigms by redefining the materials, tools and limits of the field.”27

Perhaps not surprisingly, Parent’s lifelong pursuit of architecture encompassed many of these aspects of experimentation, from his collaborations with Yves Klein in the 1950s (they worked together on the concept of “air architecture”) to his prolific drawing practice continuously pursued in lieu of retirement. The creative outcomes of his partnership with Virilio in the 1960s were a perfect match with Cook’s characterization of French experimental architecture, which he explains in his book as follows: “In France there is a tradition of utopian prognostications, accompanied by the most demonstrative physical images: these often combine a dramatic structural feat with a radical statement about society.”28 That Architecture Principe actively sought a place in the visionary domain of practice is evident, for example, from the 1965 exhibition Exploration du futur shown at Ledoux’s Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans. Focusing on architectural visionnaires from the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, the exhibition was curated by Parent and Virilio and also featured their own work. In this dual capacity, they placed their own drawings in relation to works

by Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée as well as those by a group of chosen contemporaries consisting of Archigram, the Metabolists, and Paolo Soleri—a declaration of their ambition to be considered as part of both the French lineage of visionaries and a new international wave of experimental architects creating new images of the future. In such a context, the medium of drawing provided a shared connection among architects pushing the boundaries of their discipline across different eras and geographies. Even as Parent engaged various other modes of practice throughout his career, he never stopped drawing. In fact, despite all his accomplishments, including numerous built projects, his contemporary reputation continues to grow in large part thanks to his drawings—architectural objects to be contemplated in their own right rather than documents used for constructing buildings—many of which he completed long after the permanent closure of his office.29

Practicable installations were distinguished from such drawing experiments in that they sought to engage ordinary conditions—the realities of daily inhabitation, physical sites, relationships with people, material means, and so on—in ways that extraordinary speculations on paper or screen cannot. Space—the interiors of public buildings in particular—replaced paper as the substrate for these equally experimental explorations. Paralleling Armstrong’s contemporary perspective on experimentation, Parent’s installations were in effect instruments for developing an alternative architectural paradigm, testing along the way the limits of professional practice. Not unlike Armstrong decades later, Parent viewed experimentation as a form of research. Practicables were research tools, and the purpose of these architectural experiments, as he articulated in Vivre à l’oblique and elsewhere, was akin to that of science—to test a hypothesis. To reiterate: practicables were a key phyical component, like hardware, of experiments designed to test Parent’s hypothesis about living on inclined planes; the ultimate objective was to substantiate the oblique function’s theoretical claims and demonstrate the viability of implementing them in practice.

In his 1975 memoir

Architecte: Un homme et son métier, Parent reflects on the experimental nature of the public encounter between the practicables and people as follows:

To experiment is to feel something, seen as a broadening or enrichment of knowledge, skills, and abilities. Such is the dictionary definition. Who experiments? People, the population, the crowd, the person who sets foot on these inclined planes. Who makes

experimental architecture? The architect who combines these inclined planes into a deliberate strategy of space to enable others to feel. To feel and not to see, to feel and not to say, to feel and not to think, to feel before any action other than that of sensing through the body. 30

“Experimentation,” “experimental,” and “experiment” variably refer both to specific aspects of Parent’s work and, more broadly, to alternative modes of research and design that have historically challenged the conventional scope of architectural practice and continue to do so today. Uniting all this work, then and now, is its infinite capacity for failure. The trials, errors, misses, messes, omissions, and cancelations all verify that an experiment is an experiment—and that all experiments are neither efficient enterprises nor guaranteed successes.

Parent’s experimental installations were a manifestation of the oblique function, different in their means and methods from both his published manifestos and built commissions (or “built manifestoes,” as the Parent expert Frédéric Migayrou, for example, regards the church in Nevers). 31 As an action, to manifest means bringing something into reality, view, or—as is true to the definition of the word “manifesto” as a declaration or statement—making it public; and this is how manifestation as a term, along with its variants, occasionally appears throughout this book. The public dimension of these particular actions is typically a reflection of their context, such as the types of institutional spaces where the practicables took place, or the ways in which Parent’s self-published booklets, magazines, posters, or pamphlets circulated, often free of charge, in order to reach broader audiences. However, the English use of “manifestation” adopted in the book is not to be confused with its common French meaning, where it also refers to a range of public events from rallies and protests to performances. It is appropriate as such to interpret Parent’s use of it in the chapter title “Expérimenation, manifestation, participation” as an

umbrella term that encompasses all the cultural and social activities that he was involved in throughout his tour, including presentations, lectures, debates, discussions, choreographies, demonstrations, and screenings. In this book, such manifestations are usually referred to as public programs or events.

Intertwined with experimentation and manifestation is participation as another multivalent aspect of Parent’s tour. In a general sense, the term refers to various forms of civic or social engagement, whether emerging through a grassroots process or structured by institutions or organizations. In the context of the venues that hosted the oblique experiments—the maisons de la culture and other similarly public institutional spaces charged with providing their communities a range of extracurricular engagements—participation may simply mean citizens showing up and taking part in government-funded programs, such as the “participation of inhabitants in the available facilities such as the library and the social center.”32 As publicly commissioned spatial interventions made for such venues, Parent’s practicables are in this sense participatory as a reflection of their assigned role in attracting people, encouraging their involvement, and assisting in forging a sense of social belonging in cities undergoing postwar modernization. On the whole, such forms of organized participation were part of a complex top-down effort to instill a sense of agency and self-determination among people across various layers of daily life.33 A suite of various participatory programs and activities accompanying Parent’s architectural installations and presentations in different cities reflected such institutionally driven objectives. This included self-directed workshops and working groups exploring various topics related to the built environment, from housing and urbanism to craft, prompted by but often seemingly tangential to Parent’s oblique endeavors. The difference between these programs and those already covered in the discussion above is increased direct involvement—whether it be a local community member leading a discussion group or getting their hands dirty making pottery—that rendered the participants as more than just passive viewers.

In the context of art, the curator and historian Claire Bishop addresses participation as a social practice that brings art closer to everyday life while “striving to collapse the distinction between

performer and audience, professional and amateur, production and reception.”34 From art and architecture to governance and public policy, participation generally involves multiple stakeholders in a decision-making process that shapes matters relevant to the very people engaged in it. Participatory processes across a range of fields bring together people with expertise in a subject or area gained not only through professional credentials or formal education but also life experiences or interests as citizens and members of a community. One version of such a bottom-up crossover in architecture involves “architects eschewing conventional practice and non-architects participating in space,” an encounter that is not unlike how Parent engaged the public throughout his tour.35 Participation in this sense describes Parent’s work as an intersection of his alternative approach to architectural practice and people’s direct engagement with it, with a twofold objective: From an institutional perspective, his experimental architecture was a tool for getting people to actively take part in their social environment, while the context of the everyday provided a space for Parent to figure out how to get them to care about architecture.

Throughout Ob lique Experiments , I use engagement and interaction as terms that describe ways of making social contact that are already encompassed by most definitions of participation. If my use of the term participation is as such restrained, it is part of my attempt not to overstate or misrepresent Parent’s socially driven motives or rely too heavily on the contemporary significance—and seemingly ubiquitous presence—of the term as it applies to a vast range of practices that are outside this scope. Moreover, the three terms originally brought up by Parent—experimentation, manifestation, participation—are neither stable categories of practice nor are they autonomous in relation to one another. On the contrary, the book shows in different ways how experiments are participatory and public programs can be experimental, and in this way opens up the question of practice as a series of alternative trajectories. In this spirit, the book’s fifth chapter, “Other Angles,” explores a set of relationships between Parent’s practicables and contemporary practice. While the first part of the chapter considers the layers that make up architectural ground as a series of hierarchically organized layers that can be disrupted—not unlike what Parent’s installations sought to do in their time—the second part examines how Parent’s presence throughout the tour, as an outcome of various modes of manifestation and participation, points toward new possibilities for conceptualizing the transmission of authorship in architecture. I end the chapter, and the book as a whole, with a reflection on obliqueness as a matter of motives, orientations, and approaches to experimental practice. In total, “Other Angles” presents a set of alternative connections between Parent’s oblique experiments and contemporary practice, in this way inviting readers to speculate and further build upon two themes that carry throughout the book—namely, interiority as a space of experimentation and obliqueness as an approach to experimental practice.

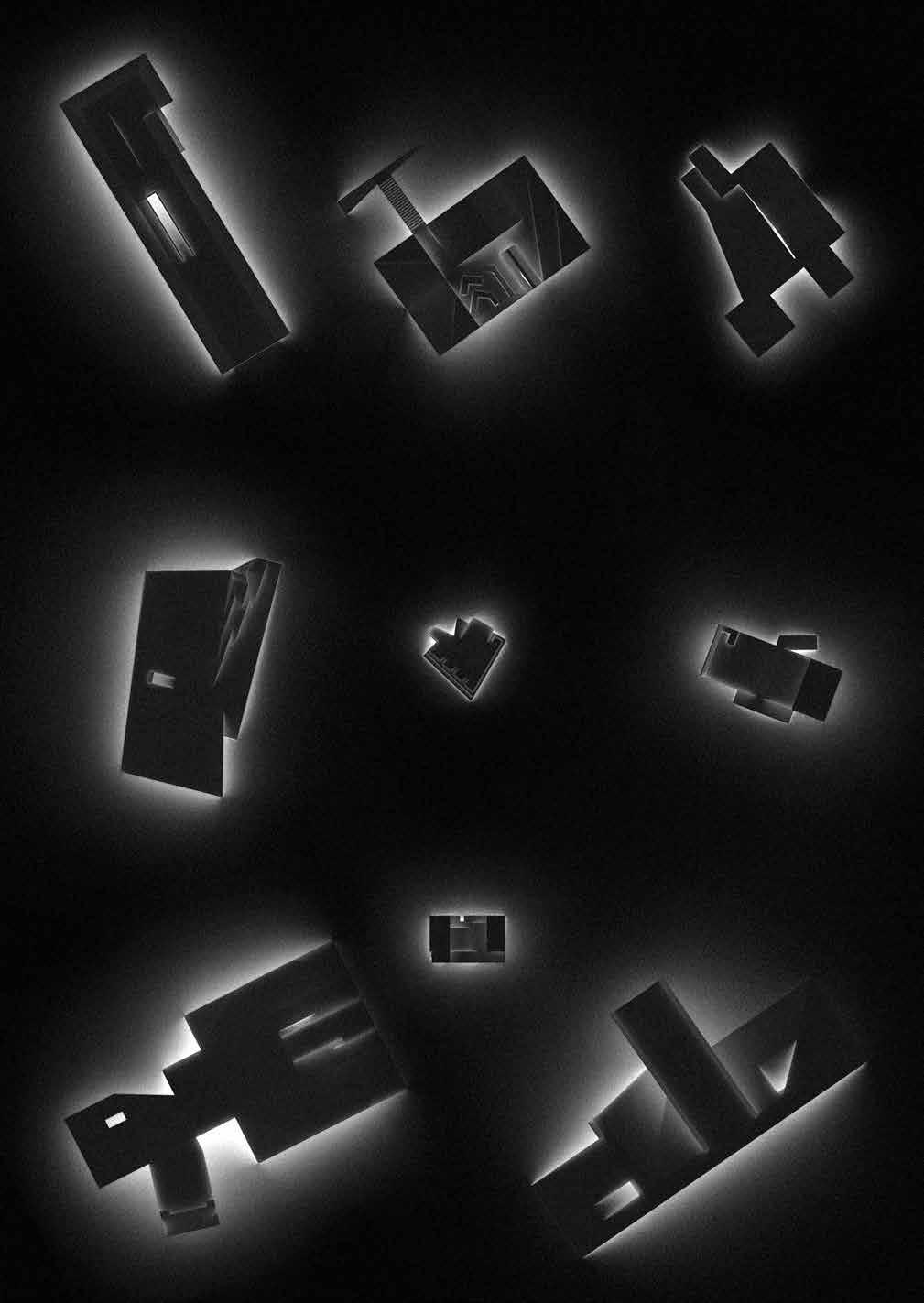

> Plan view of all nine practicables, including (top left to bottom right) Le Havre, Venice, Nevers, Amiens, Mâcon, Douai, Chalon-sur-Saône, Praticable no. 7, and Caen.

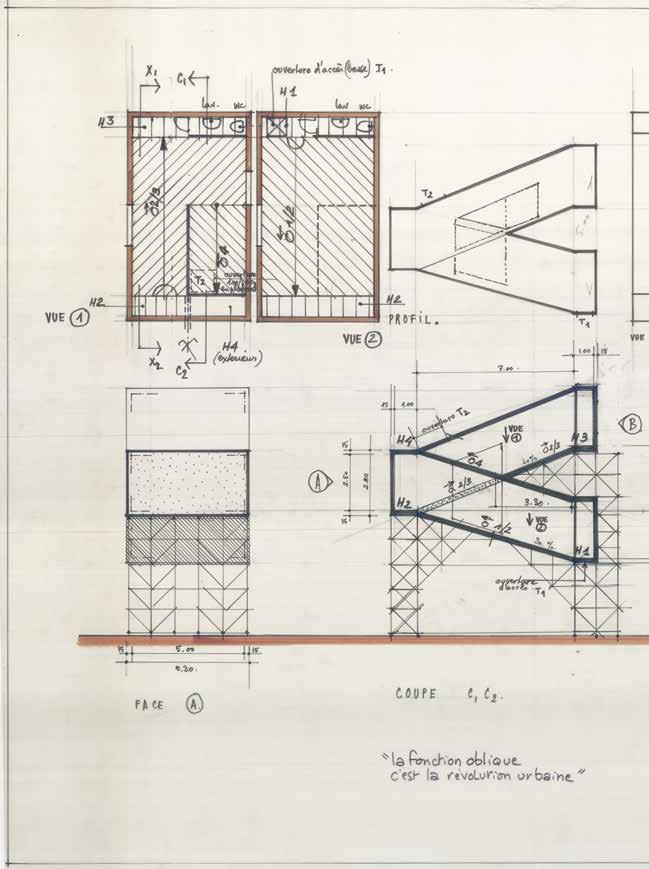

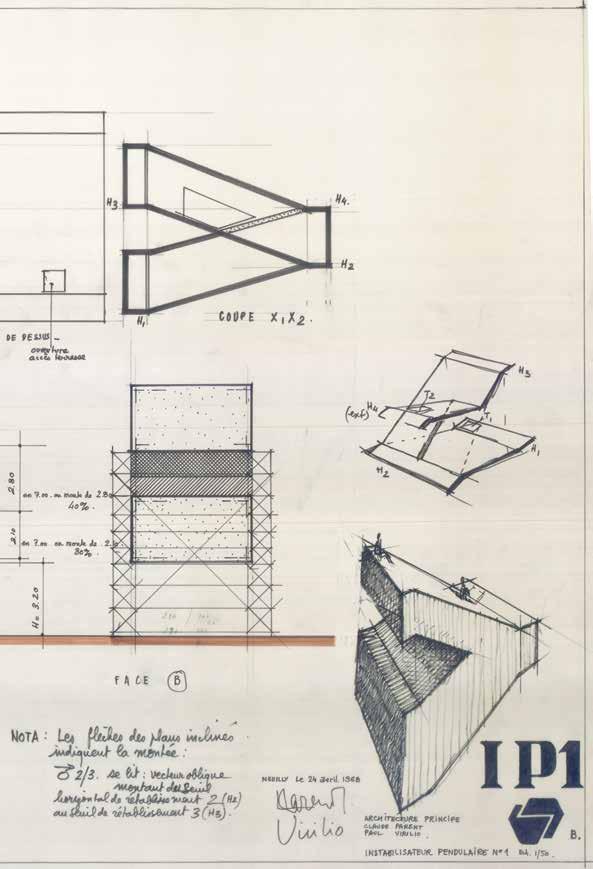

Drawings of the second of two Architecture Principe’s design schemes for the installation Instabilisateur pendulaire no. 1, dated April 24, 1968.

Shopping center in Sens, a commune in north-central France, designed by Parent and built in 1970, in its recent state as a supermarket.

Office building at 58 rue de Mouzaïa, in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, designed by Claude Parent with André Remondet and built in 1974. As part of a major renovation in 2020 by Canal Architects, the building was converted into housing for students and young workers as well as coworking space.

> Mapping of Parent’s traveling programs from 1969 to 1975, indicating locations of built practicables (magenta), practicables that were designed but not built (cyan), and those with no practicables (yellow).

Political turbulence in 1968 halted the realization of Parent and Virilio’s Instabilisateur pendulaire no. 1 and effectively marked the end of their collaboration, but Parent held onto the idea of using public installations as a means of further testing the oblique function’s practical viability.1 In the years immediately following the dissolution of Architecture Principe, Parent completed the construction of a number of substantial projects, including the shopping centers in Sens (1970) and Ris-Orangis (1971), the Rue de la Mouzaïa office building in the 19th arrondissement of Paris (1974), and the house in Soual for the painter Michel Carrade (1974), among others. Yet, it was alongside such building commissions that he dedicated a substantial amount of energy and time to the design of temporary installations—practicables—and the development of related public programs through which he experimented with the principles of oblique architecture.2 These design experiments occurred in towns all over France (with a side trip to Italy3) between 1969 and 1975. Venturing out from the French capital, Parent visited over a dozen provincial centers and small cities—villes étapes or “stopover towns” as he called them—including Le Havre, Saint-Étienne, Rennes, Nevers, Toulouse, Reims, Amiens, Mâcon, Douai, Chalon-surSaône, and Caen. At each destination he collaborated with local organizations on the development of programs generally aimed at audiences with little or no prior experience engaging experimental architecture. In addition to the usual repertoire of visiting lectures and exhibitions often pursued by architects promoting their work while traveling, Parent’s productions also included performances, workshops, study groups formed by local residents, various art demonstrations, debates, and other activities. Describing what one of his visits to a town may be like, he said to a magazine writer, “First and foremost, this event is not fixed and rigid like an exhibition. Its form

Manifestation Claude Parent: Architecture contemporaine exhibition and event flyer, Reims, 1972.

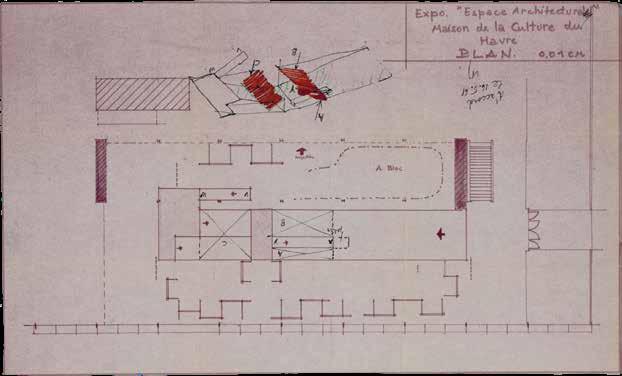

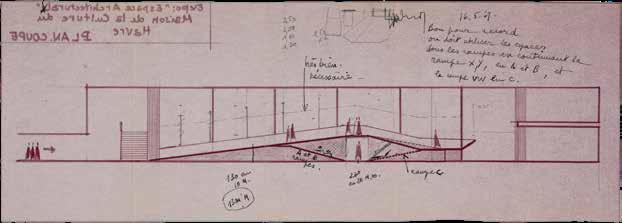

Floor plan drawing of the exhibition Espace architectural, with an overlay of freehand sketches. Section drawing of the Le Havre practicable shown inside the existing gallery, with handwritten annotations throughout.

that is dynamic rather than static—a dynamism not of mobile structures but rather of an active exchange between inhabitants and their physical environment. For Parent, this was a “permanent dialog” from which new architecture could emerge.7 The emphasis on movement served as a prominent conceptual thread that ran through an otherwise eclectic selection of works, ranging from Parent’s steel-framed buildings designed in the late 1950s to Bloc’s amorphous sculptures, alongside Architecture Principe’s explorations of the oblique function. The other connection throughout the exhibition was Parent himself, whose personal and professional relationship with both Bloc and Virilio profoundly impacted the course of his career. In a sense, the exhibition was Parent’s farewell to them both as he forged

ahead on his own: to his mentor and collaborator Bloc, who unexpectedly died in 1966, leaving behind a body of work that had yet to be exhibited at the scale of a retrospective; and to Virilio, with whom he had just parted ways after several years of a robust partnership. Tied together in this way by movement as a curatorial conceit—and by Parent’s personal relationship to all parts of the show—this diverse selection of works filled the entire museum, resulting in a reputation-affirming exhibition by a group of figures mostly unknown to the Norman audience.8

While the exhibition text mentions the oblique function just once, its principles dominated the show, the boldest evidence of which was the practicable itself. An accompanying promotional flyer for the exhibition was perforated and scored in such a way as to suggest that even a flat sheet of paper could be transformed into a miniature oblique structure. Referencing the installation at the end of his curatorial statement, Parent calls it une expérimentation implicite. 9 The phrase yields multiple, slightly different translations in English, with the word expérimentation variably referring to an experiment, experience, or experimentation. Similarly nuanced shifts in meaning are also present in the original French. Accordingly, the meaning shifts depending on one’s relationship to the practicable as an object. For the architect who created it, it can be seen as an experiment whose implicit aims have not yet been fully revealed, whereas for the users, it can be an experience whose occurrence is not entirely conscious, like a minor background event. The user’s experience, in this sense, is the architect’s experiment, a relationship that Parent further articulated in Vivre à l’oblique, published the following year. The dynamic of people engaging the ramp and the architect observing the interaction—while also placing movement on display as part of the exhibition—is one of several aspects of what throughout the later tour constituted participation and research;

View of the Venice installation showing how angled surfaces blurred differences between floors, walls, and ceiling.

While he for the most part accepted the existing flow of circulation in and out of the building, Parent transformed other aspects of the existing architecture by layering continuously folding surfaces on top of it. On the exterior, the proposed installation—represented in a white paper model and a set of orthographic drawings—appears as an oversized surface draped over the monumental stair, offering a variably navigable inclined field in lieu of a formal entrance. In doing so, the practicable functions as a space of circulation but also affords the possibility of other forms of occupation. At a smaller scale, two bridge-like parts are integrated into the larger surface, another version of his strategy, already applied in Amiens, to nest a practicable within a practicable. These parts are inhabitable from both above and below, like two modules that Parent used in an earlier set of projects, titled Inclisite, exploring the Architecture

Principe-era concept of cellular private spaces crossed, from above, by public circulation.92 Inside the building, the floor continues to slope up, smoothing out the foyer’s split floor, where the two levels were four steps apart. (The split level has since been flattened, the result of a recent building renovation.) Then, to the left of the entrance, next to the existing stair leading to the lobby’s mezzanine, the practicable slopes up at a steeper angle to create a sitting perch. Compared to the outside, the interior intervention is less extensive; yet the few components that are introduced to the space effectively disrupt the orthogonal order of the existing building. In fact, the importance of the interior portion of the design was that, according to Parent’s annotated drawings, it was intended to be constructed first, while the exterior was to follow in June of the following year.

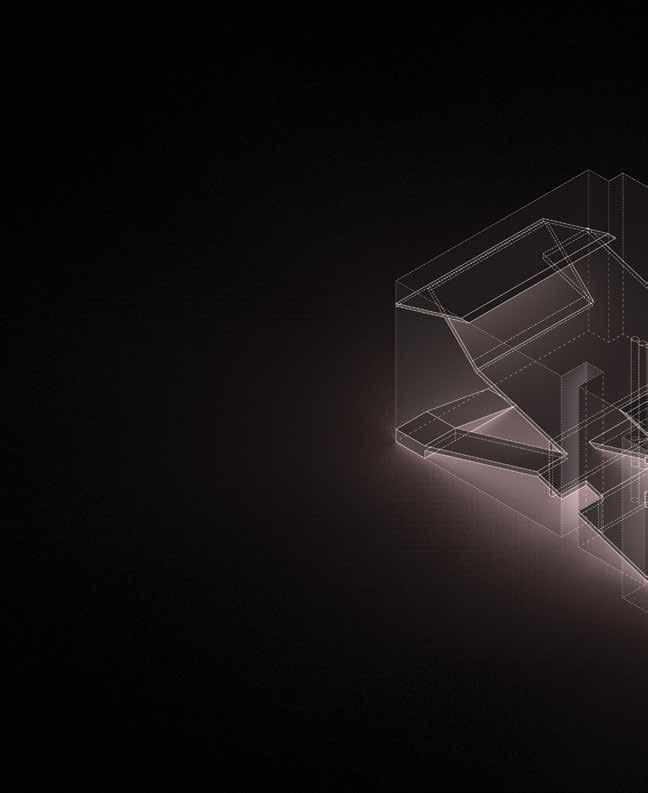

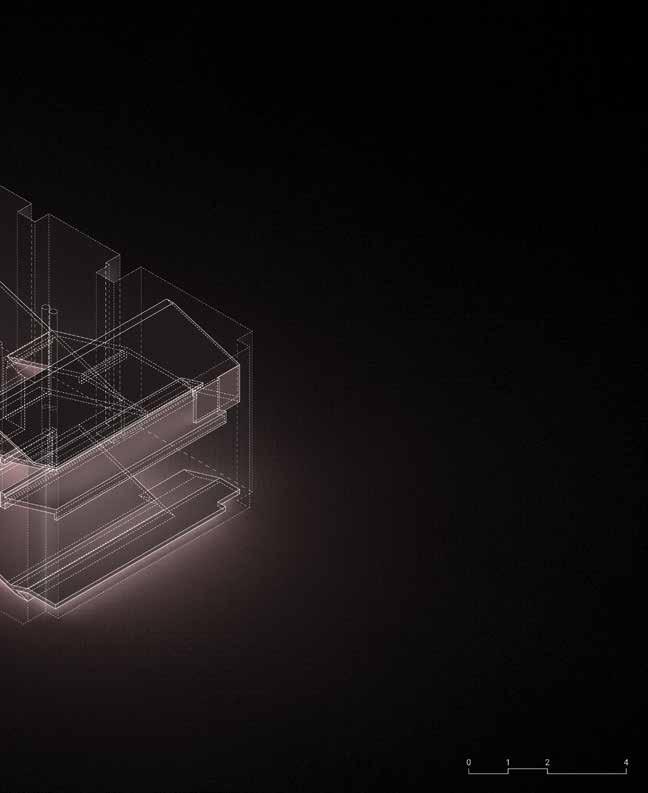

Like a theatrical stage that sits on top of an existing floor slab, the proposed practicable is structurally redundant but essential as an element that affords multiple uses. The formal continuity of the design expressed in the study model recalls the Le Havre installation in the way that railings and floor surfaces merge together rather than being separated into platforms and framing as was done in other designs—even if material specifications for the project indicate the typical combination of raw wood planks, metal scaffolding, and nonslip paint. The overall geometry of the surface has a complexity perhaps only matched by the Venice installation. Rather than using a one-directional extrusion as was done in Douai, an elongated ramp—such as in Le Havre and to some degree Nevers—or an amphitheater-like funnel shape found in both Amiens and Mâcon, the Chalon-sur-Saône design consists of a plane that folds in multiple directions, with many of the folds and creases occurring diagonally, like a fabric creased on the bias. The incline follows the path of movement from lower to upper levels, yet beyond facilitating vertical circulation in this direction, surfaces also slope up toward the sides, as if trying to contain rather than disperse people. As designed, the practicable produces a new façade for the entrance, one not made of enclosure but rather a sculpted floor that enables connection instead of separation. It is a study of the floor in elevation; an interior that not only spills outside but becomes the building’s dominant exterior appearance—an advanced iteration of the idea already introduced in Amiens.

Although Parent’s exhibition was on view inside the maison de la culture, most of his scheduled public appearances happened elsewhere. During a four-day period in mid-October, Parent met with and spoke to different audiences throughout the city—not unlike what he had previously done in Mâcon—with oblique architecture as a prompt for instigating an open dialog about living conditions and the future of the built environment.93 His Wednesday night presentation, for example, took place at a youth

Model of the Chalon-sur-Saône practicable ramping up to the exterior building entrance.

Detail of the Chalon-sur-Saône practicable, showing a smaller ramp nested within the larger inclined platform.

Exhibition and lecture flyer, September–October, 1973, Chalon-sur-Saône.

Event flyer, October 10–13, 1973, Chalon-sur-Saône.

A flyer announcing Parent’s presentation to a working group at a community center, October 11, 1973, Chalon-sur-Saône.

center, the Club de jeunes des Charreaux, on the western edge of the city— interrupted by a jazz rehearsal and rounds of foosball—while the following evening he appeared at a social club in the Prés-Saint-Jean district as part of an event organized by an urbanist working group.94 These appearances were orchestrated by the cultural center’s administration, with Parent feeling a sense of being “parachuted” into these locations under less than ideal circumstances, often having to quickly adapt to social situations as they emerged. On the third day of these roaming appearances, for instance, Parent was dispatched to the city center, where he was unexpectedly confronted by dozens of local shopkeepers more eager to share their grievances with the municipal administration than discussing the oblique function.95 His final public talk took place at the maison de la culture on a Saturday afternoon—unlike the other appearances throughout the week, this was a ticketed event with the admission price of five French francs, or about three euros in today’s currency. A local newspaper reported was an audience of some fifty people, including city officials.96 Parent recalled a patient mayor, engaged, supportive, and willing to sit through a three-hour architecture lecture.97 The sampling of different populations, neighborhoods, and organizations helped fulfill Parent’s aspirations to broaden his audience, and he described the total sum of such experiences as transformative. Reflecting on his encounters in Chalon, he writes: “Little by little, I got into the habit of better understanding, of more quickly defining what people came to ask me, what was important to them.”98 Likewise, he noted that his presence was equally critical to city officials—particularly the maison de la culture leadership—who were seeking new ways to engage people that such institutions otherwise failed to attract; he saw himself in the role of a catalyst, “a powerfully ionized intermediary.”99

The design for the unbuilt practicable represented through its architecture the same intermediary role that Parent performed socially. To put it another way, Parent and the practicable were both tasked with connecting the institution and the people outside of it. The practicable made visible the institution’s imperative to attract visitors, to create a connection between the city and the building interior. If Parent was used as a liaison between the cultural center and the local population, the proposed installation would have done the same as a connection between the interior of the maison de la culture and the city. Depending on one’s position, the Chalon practicable can be seen as an interior that gushes out of the building as much as it is the urban ground ascending like a flying carpet finding its way in.

A set of architectural drawings from Parent’s office, dated March 23, 1974, describe the design of a room-sized installation consisting of a series of interconnected ramps and titled Praticable no. 7. It is the sole scheme among the archived practicables not explicitly identified according to a specific city or venue, nor does it appear to be an alternate version of any of the other site-specific designs.

Without disclosing the exact location of the site, the drawings provide useful information about the existing architecture that was to contain the oblique installation. According to the floor plan, the overall space is about six by nine meters in area, split asymmetrically in the middle by two pairs

of slender columns in line with the load-bearing walls along the perimeter. The ceiling height was drawn at four meters in height, barely enough for a conventionally sized mezzanine but with enough flexibility for sloping the floor, as the scheme does, following a set of steep angles. To the left of the entrance, a small ramp slopes up toward a flat landing that extends the entire width of the room. From it, a large ramp with an incline of approximately twenty degrees slopes up toward the other end of the room. Another similarly angled and sized ramp stretches in the opposite direction, with

the two intersecting inclines forming an X-shaped configuration. Smaller sloping planes provide additional paths of movement throughout as well as a sense of enclosure in areas where they create a dropped ceiling above.

Sectional drawings of the design include loosely sketched figures of human bodies, inhabiting the slopes in a range of standing and seating postures. One such drawing shows multiple rows of seated figures on one slope, facing a single upright figure—drawn as if performing in a dance-like manner rather than standing still—on the opposite side. Meanwhile, the spaces underneath each incline are also populated by outlines of bodies, conveying a sense of simultaneity among the activities occurring within a single space. Other sectional drawings likewise show figures walking along the inclined paths as well as sitting inside various cocoon-like nooks. Even though it is relatively compact, the presence of multiple figures suggests that this interior was intended to be used for a range of group activities. Dimensional notations imply that, unlike the sloped interior of the children’s library in Mâcon, this space was sized for adult bodies.

The numbering of the project brings into question how Parent counted these installations. Given the date written on the drawings, Praticable no. 7 was designed after his visit to Chalon-sur-Saône but before the completion of the first design scheme for Caen, which he publicly presented in June of 1974.100 However, placing this scheme along the chronological timeline starting with Le Havre—as this book does—makes it the eighth in the series rather than seventh. To make it seventh requires excluding one of the earlier installations, such as either Le Havre or Venice, as part of the series, for which there could be multiple justifications. Only counting installation designs that were part of Parent’s tour of France with André Barey starting in 1971—and thus including some of the nondocumented proposals (for places such as Rouen),

which are mentioned but otherwise without a trace of a tangible design— could achieve a similarly numbered sequence.

As a strategy for an interior installation, Praticable no. 7 is not unlike the schemes for Venice or Mâcon in the way that it fills up the entire available footprint defined by the existing architectural envelope. The design emphasizes gathering and rest, even if circulation is an inextricable part of it. The resulting space lends itself to multiple uses and can be imagined as enabling a range of nondomestic daily activities. A magazine article published during Parent’s stay in Mâcon reported on a request made by the staff of a local teachers college to have him transform one of their classrooms according to the principles of the oblique function.101 Had the request been honored, the result would have been the second Mâcon practicable. It was nonetheless likely never fulfilled given that there is no other record of such a project. Yet it is reasonable to speculate that, had it been pursued, the design for an oblique classroom could have resembled the Praticable no. 7 scheme, given the presence of an existing room and the ramps inserted into it.

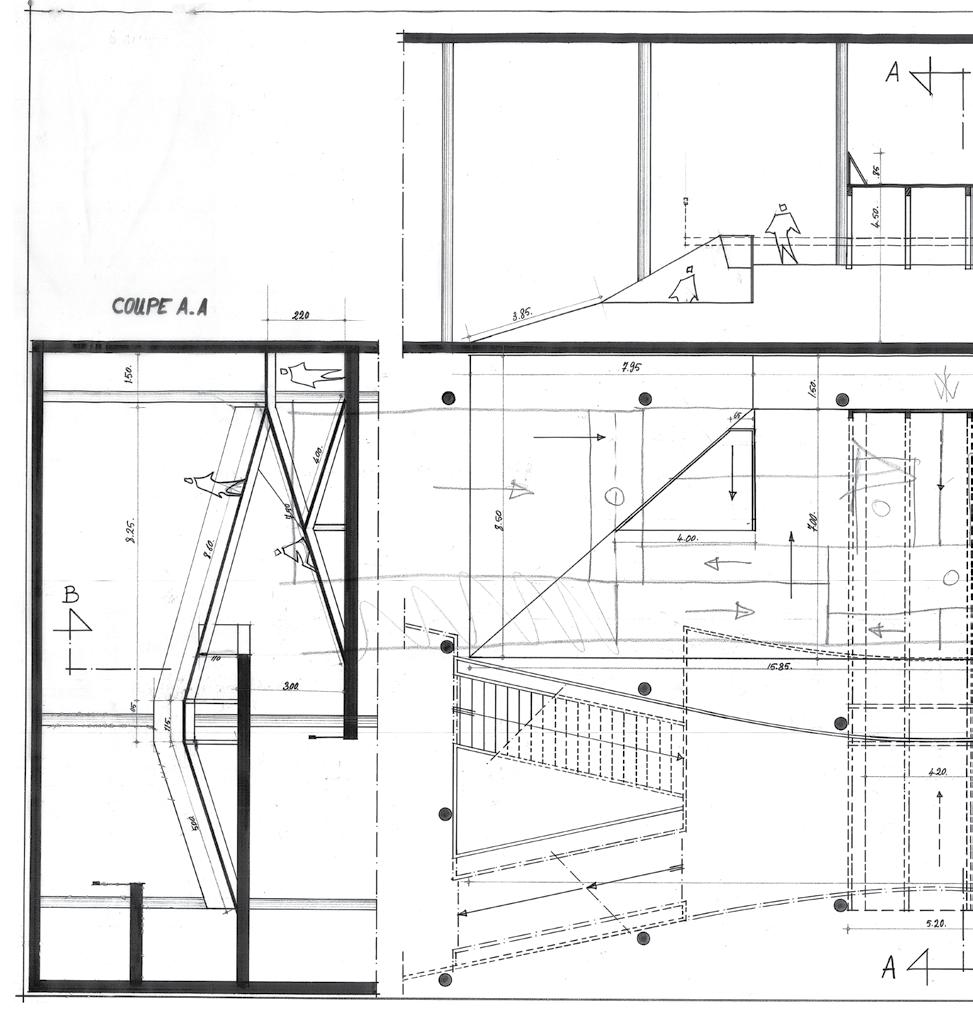

Parent’s multiyear tour of French cultural centers concluded in Normandy, the same region where he started with the 1969 installation in Le Havre, but this time in Caen. For this visit, he and Barey worked with city officials on preparations for a variety of programs to take place at the municipal theater, the building that had earlier also served as Caen’s maison de la culture. 102 Their planned repertoire included another iteration of the traveling exhibition, a mixture of live events previously staged in other cities and those created with local organizations specifically for the occasion, as well as the construction of a site-specific practicable. The proposed installation

design was exceptional among the practicables for its verticality as well as for how it engaged existing interior circulation.

The venue for the practicable and the accompanying programs, the Théâtre municipal de Caen, was built in 1963 as part of the city’s final phase of postwar reconstruction. From the outside, the building is a rectangular prism raised above street level—the visual effect of material changes in the façade from the ground level to its upper portions. It is composed of vertically oriented concrete and glass stripes whose variation in width and

depth yields a seemingly randomized pattern. The relatively opaque façade is the work of the architect François Carpentier, while the rest, including the interior, was designed by another architect, Alain Bourbonnais.103 Centered along a short side of the rectangular footprint, facing the pedestrian square, is the main entrance beyond which a low-ceiling vestibule leads to a stair that finally delivers people to the large foyer on the upper level. This generously proportioned space unfolds between the interior face of the striped façade overlooking the square on one side and the curvature of the round

trajectories and which contribute to establishing alternative connections between the past, present, and future.

With their original purpose and context in mind—as theoretically driven architectural experiments latching onto existing structures—I approach Parent’s temporary productions from three angles. The first engages the ground as a composite construct, bringing attention to its material layers and by doing so questioning the nature of the floor as a topical architectural element. The second angle considers Parent’s public role, framing his involvement throughout the tour as performance and participation but also in relation to questions of authorship. Each of these first two angles relates certain aspects of Parent’s exploration of obliqueness to a series of contemporary works by identifying and comparing their salient features to one another. The third angle traces a series of connections between Parent’s experiments and other practices based on their shared engagement with obliqueness as a term, concept, or condition, prompted by a range of diverse objectives. In this final part of the chapter, I take a broader view of obliqueness as a practice. Together, these three of an array of possible angles extend through the present with the intention of pointing to possible future directions. As a trajectory of an alternative lineage, each angle challenges existing ordering principles, from the hierarchies embedded in the layered construction of the ground to the composite of conventions against which divergent forms of experimentation emerge.

There is no shortage of sloped floors in contemporary architecture. But what would be our time’s equivalent of a practicable—a temporary installation framed by existing architecture that questions the nature of the ground we inhabit? Despite the perennial proliferations of installations by architects, some of the most provocative encounters with the ground have over the last decades been produced by artists working across other fields. As a fraction of the most compelling examples, this includes widely known artworks such as Olafur Eliasson’s Riverbed installed at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark in 2014; the artist Pierre Huyghe’s site-specific intervention After ALife Ahead produced for the 2017 Skulptur Projekte exhibition in Münster, Germany; as well as the scenery for the opera Sun & Sea (Marina) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, produced for the Venice Biennale in 2019 and on a world tour ever since. Each of these works uses the floor as an element that introduces a radical shift to an interior space, while also— not unlike the practicables—expressing distinct attitudes about human experience. Like the oblique installations, they serve as devices for speculating about the future of the living environment, while departing from Parent’s anthropocentric perspective by explicitly prioritizing, for instance, questions related to ecology, climate change, and the agency of nonhuman species.9 The floor in both Riverbed and After ALife Ahead is sloped, yet more significant than the particular geometry of each construction is its materiality. Along with Sun & Sea (Marina), these installations bring to life Parent’s notion of “the culture of tactility,” or the use of different materials on the floor as a way of eliciting various reactions from people, an idea that remained largely unrealized in his own work given that, as he admitted with some disappointment, “nobody was ever

The layering of materials in these contemporary installations is akin to the placement of practicables on top of already existing floors, while their material choices play a critical part in experimenting with the ground specifically indoors—and looking, in effect, at the living environment from the inside out.

In Riverbed, Eliasson explored the destabilizing effect of the ground on people’s perception of reality and their sense of orientation within an enclosed interior space. The temporary site-specific installation consisted of a walkable terrain distributed across four adjacent galleries that make up the Louisiana Museum’s South Wing. A combination of Icelandic rock, pebbles, and running water funneled into a stream is what visitors encountered as they climbed through the installation’s varied topography framed by a succession of white walls. As such, Riverbed formed part of the artist’s ongoing series of “installations that in various ways stage natural materials in isolated presentations.”11 Hidden underneath the rugged surface, an elevated wood structure reminiscent of Parent’s practicables provided the floor with its sloping form. The wood substrate’s faceted geometry was then softened by subsequent layers of moisture sheeting, sand, gravel, and larger rocks. Visitors traversed the installation in the general direction of

architectural historian Audrey Jeanroy interprets Parent’s interior design for the French Pavilion as a space that “transforms the spectator into a work of art.”28

The chronological and formal convergence of the work produced by these two figures, however coincidental, is one entry point into the larger field of artistic production that integrates performance in areas traditionally dominated by inanimate objects. Of particular interest in this respect are other artists who are physically present in their own art. The field occupied by such practices serves as a context for placing Parent’s event-based projects into, in order to identify specific affinities but also acknowledge considerable differences between them. Joseph Beuys, Allan Kaprow, Yoko Ono, Adrian Piper, Rebecca Horn, Marina Abramović, Joan Jonas, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Wu Tsang, and Brendan Fernandes represent a small intergenerational sliver of such an artistic lineage, which had experienced a particularly robust surge at the time of Acconci’s and Parent’s respective ramps and continues to thrive today. However, if certain aspects of Parent’s work resembled such practices, his intention was not to morph into an artist but rather expand the role of the architect to which he was unambiguously committed.29

Although not as extensive as it is in art, the presence of architects in their own work and, more broadly, the engagement of performance in architectural design, has a track record of its own. 30 The claim made by the book Bodybuilding: Architecture and Performance, edited by Charles Aubin and Carlos Minguez Carrasco and published in 2019, that

, installed

it is the first comprehensive history of performance by architects, reflects the emerging nature of the field, and similarly the 2024 publication of Architecture and Choreography: Collaborations in Dance, Space and Time by Beth Weinstein addresses another knowledge gap related to architecture’s overlap with staged performance.31 In her book The New Curator: Exhibiting Architecture and Design, the curator Fleur Watson traces the use of performance as a methodology in architecture and design to the early days of the Bauhaus School in Weimar, noting the artist, designer, and choreographer Oskar Schlemmer’s contribution to the development of the school’s compulsory curriculum. Schlemmer’s theater workshop, offered to students in the early 1920s, focused on performance as a means of exploring the relationship between bodies and space. 32 More than a century later, traces of such an approach are still present in design education, and in practice as well there is a thread that connects multiple generations of architects exploring performance—and their own physical presence—in their work.

In the late 1960s, for example, Hans Hollein, the members of Coop Himmelb(l)au, as well as the group Hans-Rucker-Co, experimented with designing, fabricating, and then inhabiting clear plastic bubbles, with plenty of photographs to prove it.33 These young Austrian architects explored the potential of pneumatic construction, while also experimenting with ways in which bodies interfaced with media in the age of urban mobility. In the United States, the group Ant Farm went on a performance tour of their own, promoting inflatable architecture and their how-to zine Inflatocookbook, first published in 1971. A self-described “body architect,” Lucy McRae engages her body as a site and subject of technological fictions reminiscent of 1960s wearable architecture as played out in her gallery installations, narrative-driven images, and videos produced since the early 2010s. Likewise, Alex Schweder, who was educated as an architect and currently practices what he refers to as “Performance Architecture,” often works with inflatables and appears in his installations as a performer, inhabitant, or installation operator, depending on the situation.

One such work, titled ReActor (2016), was a rectangular glass pavilion built in a rural field to be used as an experimental living unit for two people. Supported by only one center column, the structure hovered above the ground with Schweder occupying one side of it and his partner, the artist Ward Shelley, the other. Depending on how the two people moved in relation to one another, the pavilion tilted back and forth like a seesaw. ReActor can be compared to Parent and Virilio’s unbuilt gallery installation Instabilisateur pendulaire no. 1 in the way that it put the two artists on an elevated slope in relation to one another as part of a live-in experiment. Schweder and Shelley collaborated on other projects exploring similar balancing acts, which probe the intimate and codependent nature of one-on-one relationships. In another performance-based installation, My Turn (2018), the artists’ experimental habitat was a vertically oriented spinning wheel placed inside a gallery; an earlier version of it, Your Turn (2017) played out a similarly reciprocal dynamic along a two-sided climbing wall. However, it is perhaps Schweder’s ongoing solo series Performative Renovations that pushes his presence so close to the conceptual center of the work that the architect is not in but rather is the architecture itself, to paraphrase a term formulated by the architectural critic Germano Celant for referring to the radical architecture of the early

provoke and make the world more livable. She likewise suspects that we might already be “swimming inside a new age of manifesto architecture,” but not yet be able to recognize it. 67 Life is still spatial, and the built environment poses both opportunities and challenges for those that inhabit it. Architects, like everyone else in their own way, continue to trace what has existed before them in order to imagine what is yet to be.

The feminist writer Sara Ahmed has, for example, taken on a certain tradition in philosophy in order to reshape it, namely by working to “queer” the field of phenomenology.68 In doing so, Ahmed engages the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s seminal 1945 book Phenomenology of Perception in which the term “oblique” describes the relationship between a subject and their environment, particularly noting the subject’s capacity to adjust or straighten themselves. In her work on queer phenomenology, she takes on these moments of obliqueness as “queer,” a word also used by Merleau-Ponty, albeit in a different sense, in an attempt to redefine the terms of such orientation. She asks: “What happens if we consider the queer potential of the oblique?”69

Taking this question posed in the context of philosophy and redirecting it toward architecture brings to my mind works that already seem to flow along such a trajectory, including, for instance, the performance artists Gerard & Kelly’s Modern Living, a sensuous takeover of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye from 2019, and the interdisciplinary artist Vaginal Davis’s HAG – small, contemporary, haggard, a compact exhibition pavilion with

a sloping floor, modeled after the artist’s house gallery from the 1980s, first constructed at Participant, Inc. in New York in 2012 and reconstructed in 2024 at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. What comes to your mind when contemplating Ahmed’s question?

The experiment of putting various pursuits of obliqueness into contact with one another based on a shared vocabulary pulls Parent’s architecture toward music, economics, linguistics, and philosophy and in this way places his practicables into an expanded field of words, images, structures, concepts, processes, intentions, bodies, spaces, and strategies. By surveying and starting to dig into this diverse field, obliqueness emerges as a form of divergence, a common trait that runs through Eno’s instructional prompts, Kay’s pursuit of higher-level objectives, Curzan’s punctuation, Balmond’s research, Easterling’s know-how, Ahmed’s embodied identities, as well as Parent’s architectural form. As a departure from a given order—norm, convention, standard, procedure, or posture—divergence instigates ways of working, thinking, making, sensing, and living in the world, of which the practices introduced in this part of the chapter are just the beginning. Furthermore, divergence enables one to make connections across a field from any given point, like a nervous system in which one neuron can communicate with many other neurons. Considered from such an angle, obliqueness is not only a property based on orientation but also describes the capacity to forge connections that have not yet been made.