Beauty Through Clarity

Joseph Giovannini

The scenery behind the musicians in the top-floor performance space in the San Francisco Conservatory of Music is as majestic as any painted backdrop on stage at La Scala, except that it is real. The audience at concerts and recitals—ranging from Yo-Yo Ma to four-year-olds—look out past the performers to the dome of City Hall, the centerpiece of the city’s classicized Civic Center. With its gilded ribs, the dome recalls Michelangelo’s at the Vatican and Brunelleschi’s in Florence. At night, motorists and pedestrians on adjacent Van Ness Avenue see the lead corner of the performance hall, which edges out slightly over the sidewalk, glowing like a lantern. The space that looks out at the monuments of the city is itself an object to look at, a worthy addition to a distinguished cityscape.

Few other American cities have the right to as much architectural pride as San Francisco, and few are more architecturally self-conscious and self-protective. For decades the city has curated specimens of architecture like its majestic collection of trees in Golden Gate Park. The forty-ninesquare-mile peninsula grew a concentration of tall, architect-designed structures, and seismic requirements caused buildings to be constructed to a high standard. The cumulative result is a building-by-building, street-by-street environment that establishes environmental dignity in the

public realm. The city was rebuilt after the 1906 earthquake over the decades when traditional architectural styles gave way to modernism. As a result, for a city considered one of the most “European” in the United States, San Francisco is surprisingly both modern and modernist. Its residents are the audience to, and protectors of, a unique architectural legacy.

It has long been an article of faith that architecture, like politics, is local, and that architects traditionally have grown their practices from within a community indigenous to a place, a genius loci. But with the accelerating globalization of the last several decades, many architects, especially starchitects, have parachuted into cities where, with little understanding of local culture, they drop a signature design on a site and then leave. They are usually hired to do their stylized buildings precisely because the designs stand apart from the local rule.

Mark Cavagnero is a notable exception, an architect with work of national stature who has grown his practice out of San Francisco and the Bay Area since he established his eponymous firm in 1993. He designs works to be building blocks for the city, not freestanding statements. He draws on the values of the community for which his work is appreciated. He is an architect with honor at home.

If he has grown his practice out of an understanding of the city and region, he has grown the vision he brought to San Francisco out of the legacy of modernism. His understanding of the legacy, however, is complex, reaching well beyond the standard Bauhaus history and Architecture History 101. As an undergraduate at Harvard, he studied with the architectural historian and Le Corbusier expert William J. R. Curtis, and in the graduate architecture school at UC Berkeley he studied with Spiro Kostof and taught his own seminar in twentieth-century architectural theory. Over the years he developed a modernist individualism and an architect’s architecture that referenced the attributes of some of the international masters who came before him: the spatial complexity and porosity of Italian Giuseppe Terragni; warm, wood-inflected modernism of Finnish Alvar Aalto; sharply eroded sculptural geometries of Swiss Luigi Snozzi; crafted meditations of Italian Carlo Scarpa; and serene geometric purities of American Louis I. Kahn. He turned many stones—some obvious, some obscure—over in his mind and eye, drawing his own conclusions.

Cavagnero searched for authenticity in the buildings he admired, reading the literature, traveling, absorbing the lessons that are never obvious. He understood modernism for its underlying

intelligence rather than style; for its physical and cultural context, not for its imagery.

Le Corbusier’s writings suggest that a building should have three scales of clarity—at a distance as a beautiful form, at mid scale as a complex and well-proportioned facade, and up close as well detailed in its materials and craft. Cavagnero admired Le Corbusier for elevating his structures on pilotis so that volumes rest lightly on shadows. He respected Terragni for integrating walls into adjacent structural frames. Construction itself interested the aspiring architect: during a year as a construction worker, he saw concrete being mixed, slumped, poured, and vibrated, and developed an understanding of how to achieve the expressive, structural, and aesthetic potential of the timeless material.

As Cavagnero acquired a deep literacy of modernism, he developed his own interpretations. Modernism was not frozen. Probing its diversity, looking beyond received interpretations, he synthesized his own direction from both mainstream and more obscure examples. Beyond connoisseurship, he needed to know what to do and why he was doing it. Modernism was not a finished history but still had potential for invention and reinvention. He gradually wrote chapters of his own.

As he came up in college and entered the architectural profession in New York in the 1980s, modernism itself had lost its edge and relevance in a changing society, and with its commercial success and consequent complacency, it had lost its original aspirational impulse and drive for continuous invention and societal meaning. Looking for alternatives to modernism, some architects of the era migrated toward the soft blandishments of postmodernism, and then to the iconoclastic apostasies of deconstructivism, and more recently to digital design.

Cavagnero instead understood that modernism had unrealized potential. He turned the prism to look at it in different ways, focusing on its successes (famous and obscure), distilling lessons, forming his own insights, finding ways for revision and renewal. He remodeled and extended the modern legacy that he would bring to California.

When he arrived, he confronted building conditions that exercised new demands and further shaped his thinking: seismic requirements, patterns of strong light and consistent wind, car culture, a tight sense of community, architecture’s civic role, even the freestanding California live oak and the environment it represented. No less than the founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, had regionalized his work in Massachusetts when he set his own pristine white house

on a foundation of boulders excavated from the site. Local circumstance matter: genius loci is necessary in architecture.

When Cavagnero opened his office in 1993, lean years of a small practice followed, based on renovations that limited his architectural range. Importantly his pursuit of an authentic practicable language continued. However, in 2000, after several years of guiding a client through attempts at remodeling existing structures, Cavagnero received the commission to build its ground-up performing arts center, the Community School of Music and Arts at Finn Center (CSMA) in Mountain View, on the San Francisco peninsula. He was prepared. He brought his literacy and a renewed legacy to bear.

His first task was to develop an economic solution that could solve acoustic and seismic requirements within the larger architectural design. Rather than retrofitting seismic engineering into a design fait accompli, he integrated the engineering as a feature of the design. Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como provided an abstract idea—extending long, horizontal beams from the sheer walls—as a formal device to hyphenate the facades into an aesthetic whole. Here, the judiciously placed concrete walls could satisfy seismic bracing needs. Engineering could meet the eye’s need to complete a geometric thought. He filled in the bays of the structural steel grid with glass and wood panels, the wood bringing warmth and texture to the building. He kept the palette of materials simple—concrete, wood, and glass—and limited the colors to a pale and consistent tonality without disruptive contrasts.

He kept the corners and edges of the facades crisp, completing the volumes with geometric decisiveness. By juxtaposing separate volumes in an interlocking relationship, he generated

Casa del Fascio

a combined complexity out of singular simplicities. The stability and fullness of the volume gives the building a presence that holds a site otherwise destabilized by neighboring roadways, railways, and industrial buildings. Elegantly detailed, the strong geometries and full volumes give the performing arts center an institutional gravitas and an overall legibility of purity and clarity of form. The building is beautiful and was widely published.

Believing in the integrity of the well-proportioned room, Cavagnero kept the CSMA’s plans simple and cellular. The project’s recital hall is lyrical in its simplicity, an acoustically bright musical passage in itself. Unlike the open spaces of modernism’s usually open plan, rooms as rooms ring the building’s courtyard in neat rows, transmitting to the inside the volumetric integrity of the exterior. There is something fundamentally satisfying about the decisiveness and clarity of the plan, the rooms designed according to the proportions of the golden mean. Inside and out, Cavagnero disciplined the whole by subtraction, eliminating any extraneous lines or materials as he filtered his design decisions to achieve aesthetic simplicity and clarity. Nowhere is there a lapse in tone; nowhere the disruption of high contrast or anything discordant. The self-reinforcing consistency of materials, colors, and geometry achieves a quiet visual grace.

The design was not a Terragni, a Scarpa, a Kahn, a Le Corbusier, or a Snozzi, but a Cavagnero. He had found his signature, and it was legible, credible, and authentic. As his first ground-up work, CSMA was surprisingly mature, a thesis building distilling what he had learned and thought since his Harvard years two decades earlier. A summary of his own research, it contained the DNA of his subsequent work.

Community School of Music and Arts at Finn Center

A direct line led from CSMA to other work for performing arts institutions in San Francisco. Unlike Mountain View’s open, heavily trafficked intersection, San Francisco offered infill sites in the dense tissue of the city, where building design had to embody the concerns of the surrounding community. Neighborly, sensitive architectural behavior was required. On tight, expensive sites, the buildings also had to fulfill ambitious programmatic wish lists.

A large corner lot in a residential neighborhood of wood-frame buildings and storefronts with the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall just down the block was the site for the SFJAZZ Center, a project that had gestated for a decade. The center belonged to both its funky immediate neighborhood and to institutional colleagues at the Civic Center nearby. A sensitive but firm touch was required to address both scales and contexts.

Cavagnero again treated the need for integrated engineering as a point of departure and a generative design move necessary for authenticity, clarity, and economy of means. He spent concrete strategically and economically, encasing an auditorium at the core of the building in a box that provided acoustic isolation and relieved the facade from shouldering much of the burden of lateral bracing. The physical heart of SFJAZZ is this auditorium, and the soul of that space is jazz performance, which Cavagnero supported through design. He conceived the hall from the reciprocal points of view of performer and audience and stepped seating in a terraced plan so that musicians could riff to the eyes of an audience rising into view on the stepped tiers. He carefully adjusted the acoustics to minimize any need for amplification so that the musicians could hear one another. With his belief in the power

Swiss Pavilion

of a room designed for its sense of containment, he proportioned it to be roughly square in plan. The big room feels intimate, the community feels close.

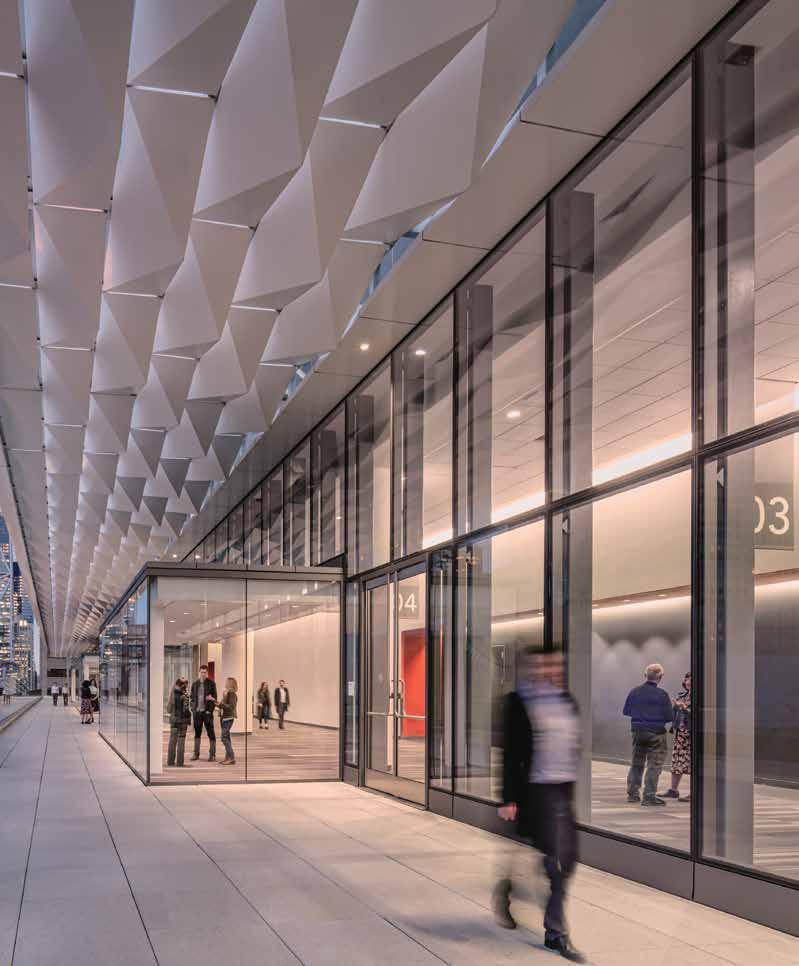

Along both adjoining streets, the architect consolidated and lifted the second and third stories above a ground floor entirely covered in high-clarity glass. Upper volumes cantilever, scaling the building down to pedestrian height by giving the sidewalk a ceiling. The upper two floors appear to float lightly, as in Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Internationale Universitaire in Paris, a building Cavagnero greatly admires.

At SFJAZZ, Cavagnero used panels of frosted glass between spans of clear glass to establish a peristyle of window bays that, fortuitously, has the regularity of the Parthenon’s peristyle. Deploying the frosted panels on the second floor in an A-B-A-B pattern and on the third floor in a B-A-B-A pattern, he syncopated the facade visually, animating what might otherwise seem a static composition. He emphasized the horizontality of the floor and roof lines to unify and encase the upper facade, underlining with clear geometry the sense that those upper floors are a volumetric whole. Edging the volume in concrete gives the building visual unity, and floating the upper stories gives the building lightness.

With a track record of beautiful, civic-minded buildings that honor the street and the community and express their unique program, Cavagnero earned institutional trust in a short period of time in a city where word of mouth spreads quickly within a tight community of civic leaders. Cavagnero was responsive, capable, talented, and likable. He listened. He also had something to say. Institutional commissions within San Francisco concatenated.

SFJAZZ Center

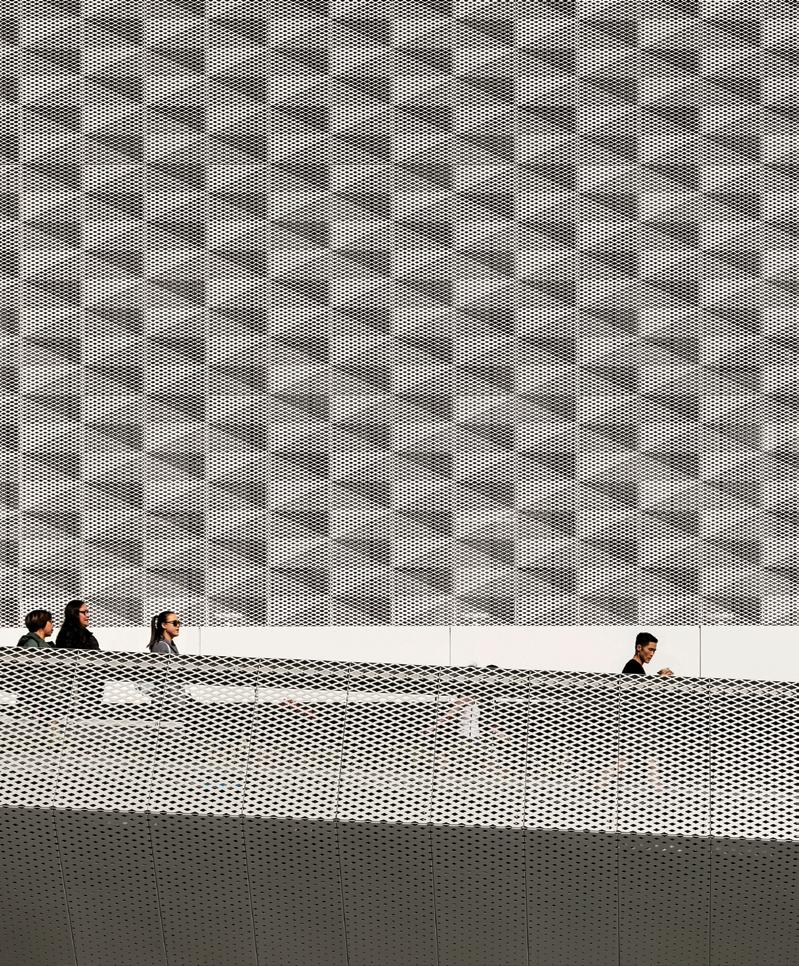

The Ute and William K. Bowes, Jr. Center for Performing Arts, San Francisco Conservatory of Music lies near SFJAZZ on a corner lot directly opposite Davies Symphony Hall. Like the jazz center, the conservatory is efficiently packed with program, including two stories of community housing, many stories of school dormitories, numerous practice rooms, a public café, recording studio, guest suites, and the performance hall on the eleventh floor looking eye-to-eye with the dome of City Hall. Again, Cavagnero lifts and cantilevers a crisply defined cubic volume over a glass-enclosed base. Again, he uses glass, this time opaque rather than frosted, to define the bays and the wholeness of a facade that reads as a stable solid. Again, he edits the facade by subtraction, eliminating the typical, pesky ventilators by designing slim vents to the side of the windows. He crowns the building block with the performance space extending from the volume below, angling it over the street to give a sense of movement to the otherwise cubic base.

Inside the glass hall, triple glazed for acoustic isolation, he curves the interior side wall to open the view to City Hall and the sweeping urban panorama, detailing the wall so that it evenly disperses and absorbs sound. He worked closely with an acoustician to assure that the opposing hard glass walls that permit the stunning panorama also work for sound. This is Tanglewood in San Francisco, open to the out-of-doors visually, except that the structure proudly gives visual access to the urban habitat rather than to nature.

For Sava Pool, a community pool in San Francisco’s Parkside neighborhood, Cavagnero was in fact able to open a building to a Tanglewood context. The project was small, no more than a seven-lane indoor pool backed with supporting dressing rooms and offices. But the site was sensitive: a sloping piece of land negotiating the transition and the view from rows of suburban houses along a busy avenue to the much-loved, thirty-three-acre Stern Grove. He broke the scale of the structure down by interlocking the smaller volume housing the supporting rooms with the much larger volume spanning the pool. The architect nested the working rooms into the upslope of the site, so as not to obstruct the long ocean view from the surrounding houses. He then opened the pool itself to the grove by fronting the pool structure with a long, tall facade of glass that, in the full light of day, gives a sense of swimming out of doors. He proportioned the space housing the pool carefully to allow enough height for the breadth of the large pool; the space that opens to the grove is itself a satisfying room scaled for the community, Cavagnero’s successes at medium-scale buildings earned the attention and trust of large institutions. The University of California, San Francisco, hired the architect to design its

Neurosciences Building, a major structure on its Mission Bay campus. He faced the challenge that many architects with emerging firms face: upscaling their design vision to a very large building. He needed to translate the principles of his evolved modernism—which he carefully curated idea by idea, incrementally, starting at architecture school—to the 282,500-square-foot project.

He lifted a well-defined volume on a transparent plinth, organizing a perimeter of research laboratories and treatment clinics around a generous and impressive seven-story atrium that explains the building to the visitor, laying it all out clearly. The building’s husband-and-wife donors, Joan and Sanford I. Weill, had seemingly conflicting goals at the outset of the project. Sanford, a successful entrepreneur, wanted a “wow” building while Joan asked for a reassuring building that would welcome patients who often had cognitive problems requiring real-time procedures lasting hours. She wanted to take the chill off intimidating out-patient treatments by adjusting the psychological temperature of the building.

Cavagnero reconciled these differing intentions. He centered symmetrical, lateral wings on a recessed entry and topped them with what seems like a gull-winged roof to create a big first impression, which continues inside with a vast, seven-story, skylit atrium. A palette of blond woods and gentle, blue-gray marble paving brings a psychological calm to the atrium. Treatment rooms have an open spa-like tranquility enhanced by more blond woods, while glass perimeter walls open west-facing spaces to a view of a densely treed park.

Cavagnero took special care to design laboratories—often grim and crowded with technical equipment along narrow aisles—to be open and luminous, flooded with natural light. No curtains are required to protect from the sun since Cavagnero took the roof to the edge of the building and folded it down the facades into a scrim of open metal latticework that allows views out while protecting the interior from the sun. He had adapted Le Corbusier’s concrete sunscreens into a lightweight metal equivalent that transforms with the sunlight—opaque and solid at times, shimmering at others.

The building is phenomenal, registering change with passing clouds and the diurnal rhythm of the sun. Wrapping the roof around sides gives the project an enveloping sense of containment and literally an edge that keeps the glass facades from bleeding inconclusively into the sky. The building holds its own in space, anchoring the adjacent quad and the center of the campus.

Not all modernisms in the modernist legacy are successful modernisms, and San Francisco built at least one major failure in 1981. At a time when its South of Market (SoMa) neighborhood was troubled, dangerous, and poor, the Moscone Center was designed with a perimeter of landscaped berms and exit doors that shielded conventioneers. The bermed perimeter, softened with apologetic landscaping, was closed to the street and alienating. Over the years SoMa gentrified, and the size of the center grew inadequate for the increasing sizes of conventions, a principal source of revenue for the city.

Commissioned to expand Moscone Center, Cavagnero planned to turn the building inside out, extroverting the perimeter to the new, wide, pedestrian-friendly sidewalks with clean glass walls and elevating the great halls inside within a grand, three-block-long, multistory volume positioned like a piano nobile. A master at handling architectural scale, Cavagnero broke down the mass with block-long roof overhangs that give the sidewalks ceilings. He projected a very long, all-glass, “bay window” from the main mass of the piano nobile, nesting the bay window within the larger volume and giving the monumental structure two scales. A lithe bridge as elegant as a long cigarette holder connects the convention center to an addition across the street.

His aesthetic of simplicity and clarity permits exceptional moments. The language is not self-restrictive. For his expansion of the Oakland Museum of California, a 1960s structure and designated landmark that East Coast architect Kevin Roche had designed among terraced gardens, Cavagnero respected the original building by tactfully opening it to the street. He did this with canopies and a covered passage that invite passersby to the entrance on the far side of an entry plaza. His additions are simple interventions, architectural accessories broken into parts. He articulated each part, separating columns from canopies and canopies from walls with slots of space that individuate the parts into a right-angled cadenza of intermingled form and space. The openings permit glimpses to the sky as sunlight beams through the apertures, mixing light with shadow, registering changes in the day like a sundial. The new architectural anatomy barely touches the original building, but it reintroduces and ingratiates an aloof building to visitors with elements at an intermediate scale with granular details. The addition, no more than a couple of long planes supported by some outrigger columns, touches the building lightly. The touch is masterful.

Cavagnero’s portfolio of buildings across types, scales, and three decades of practice is remarkably consistent because he bases design on principles he spent years cultivating—interlocking volumes, a limited palette of wood and concrete, lightness, authenticity, presence, and multiple scales designed to read at varying distances. He carries these principles forward to new designs, adding new themes and varying their application per the individual demands of changing projects. He tests the application of these principles against an overarching belief in simplicity and clarity and the conviction that the architect should create a building that relates fundamentally to its use and site, with beauty. He understands modernism deeply, and renews its legacy with fresh, serious, and original works that respectfully transform and perpetuate the spirit of his original inspirations.

Joseph Giovannini holds a masters in architecture from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. He has taught at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, UCLA’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning, the University of Southern California School of Architecture, and the University of Innsbruck. Mr. Giovannini has written on architecture and design for three decades for The New York Times, Architectural Record, Art in America, Art Forum, and Architecture Magazine. He has also served as the architecture critic for New York Magazine and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

Mark Cavagnero

I have spent most of my life trying to filter an overwhelming amount of information and run it through my own quite personal lens. At times, little seemed in focus. At other, more extreme times, it seemed like midnight, with the aura of darkness yielding little clarity. Occasionally I had a bright, clear moment where disparate threads from very different sources coalesced and brought order to my thinking. These moments have stayed with me. Some of them happened in academia, some in the workplace, and some only upon sketching and ruminating with no distractions whatsoever. Regardless, I like any architect, find the real challenge in design is deciding what to keep, what to modify, and what to let go.

Growing up in Litchfield County, Connecticut, I was exposed to Marcel Breuer’s architecture. My father worked at Torin Corporation, a machine design company. Breuer designed three houses for each of my father’s two closest colleagues, Andrew Gagarin and Rufus Stillman. Breuer also designed Torin’s factories and headquarters and the Tech Center where my father developed his machinery. In seventh grade I walked the site on Saturday mornings, listening to my father explain the design process with Breuer.

This experience sparked a strong interest in modern architecture. Discovering Who Was Le Corbusier by Maurice Besset in my school library at age fourteen was pivotal. I was excited by Le Corbusier’s drawings for Algiers and Paris. The early villas seemed astounding, as they were modern like the Breuer houses I had visited, but much more dramatic, powerful, and sculptural. Becoming preoccupied with Le Corbusier’s ideas and work, I read everything I could find on his buildings, which was, unfortunately, not much in rural Connecticut.

This early exposure to Le Corbusier introduced me to cast concrete as a modern masonry, an idea I have never abandoned. Similarly, visiting these Breuer buildings exposed me to the power of craft and how materials can be used to underscore spatial ideas.

I left Litchfield County for Harvard College quite certain I wanted to be an architect, but equally assured that I needed a solid liberal arts education to ground me. I chose a joint concentration in History with Visual and Environmental Studies. After two years of studio art classes with Lou Bakanowsky, Flora Natapoff, and Will Reimann and film analysis with Nick Brown, I was able to begin an architectural education. I studied history with Eduard Sekler while spending my evenings in the Carpenter Center with two years of studio design with Albert Szabo. My most exciting classes were seminars on modern architecture with William J. R. Curtis, who dug deeply into how Le Corbusier made form.

My thesis, with John Stilgoe as my adviser, combined history with architecture. I focused on the poor, at times intentionally mean-spirited, planning and design of American public housing, looking specifically at one project in the Mission Hill neighborhood of Boston. The project was built in two phases, the first during the Depression for then-unemployed White workers and the second after World War II for recently migrated Black factory workers. The disparity between the levels of care and design of the two phases astounded me. Architecture completely changed the environment these people lived with daily. It was not used to improve the community or people’s lives, but had become a tool to degrade the neighborhood and enhance profit. Studying art, architecture, and history at Harvard connected the roles of design within the community; it showed me how architecture can become a powerful cultural force, one that could be harnessed either for good or for manipulation.

I left Harvard and went to University of California, Berkeley for my masters degree. There I studied architectural history with Spiro Kostof and worked for him as a graduate assistant. I organized and led a graduate-level course on twentieth-century theory and ideas, loosely modeled after Curtis’s seminars. I had a chance to study with John Shaw, one of the group of educators known as the Texas Rangers, on loan at the time from Cornell University. He taught me a great deal about site and context and how an architect should practice with responsibility. Shaw’s lessons still ring true to me, as I aspire to design buildings that respond to their location sensitively rather than aim for a purely self-reflective stature.

After I graduated, I went to work for Edward Larrabee Barnes, a talented New York architect. In the 1940s he was a Harvard classmate of Philip Johnson and I. M. Pei, studying under Walter Gropius and Breuer. Barnes was very close to Breuer and designed his own house in Mount Kisco, New York, as a plinth house, as Breuer taught him. Barnes knew of my personal connection to Breuer. On my visits to his home, Barnes and I discussed about how his early work derived from Breuer and how he developed his own thinking as his practice evolved.

My influences, like Barnes’s, grew a bit slowly, but I remained extremely focused on Le Corbusier and Louis I. Kahn. I traveled quite extensively to see their work. I spent time in the Ticino area of Switzerland and came to admire the work of Luigi Snozzi. Eventually I made it to Finland and visited many of Alvar Aalto’s works. I was impressed by his ability to place a building into an urban context with care but still maintain a sense of modern form and beauty. In my late twenties, I first came across Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como, Italy and loved its wall-and-frame discipline. I then went to see several of his apartment buildings. Terragni’s influence can be seen in my firm’s first new building project, the Community School of Music and Arts at Finn Center (CSMA, page 35).

I eventually left New York and relocated to California, setting up an independent practice. I began working on the renovation and expansion of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor in 1992 as an associate architect to Barnes. A year into the project Barnes retired, and I was asked to take over the project and complete the design and its execution. That year, 1993, I founded Mark Cavagnero Associates (MCA). The Legion of Honor Expansion was completed several years later and was widely published and well received.

The ensuing opportunities for MCA were renovations and/or arts oriented, such as the San Rafael Film Center, the Headlands Center for the Arts, the Barbary Coast Building, and other Bay Area projects. Each was a deliberate study with which we took extreme care in distinguishing the new and contemporary from the existing and restored. (Carlo Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum was my basis for designing contemporary insertions within historic structures.) Our reputation for such work grew quickly, and a variety of project opportunities emerged that kept us busy and growing.

After five years, I was offered the chance to design a new, freestanding building—CSMA. This was both exciting and intimidating, as it was much more difficult than my previous projects. I had spent years working with Barnes’s gestalt, focusing on lightness and volume, learning to see how he saw. I tried to marry the ideas he taught me with those I had studied in the buildings of Le Corbusier, Terragni, Aalto, and Kahn. I struggled with the interconnection of these ideas— how to find my own resonance.

I wanted to develop an authentic approach so that the work was based not on style but on substantive thought. I also wanted to build in a way that made sense in California, where a high seismic threat is the strong reality, and a sunny climate is both pleasant and demanding. I found my language at CSMA; it is a clear and direct building, expressive of its use and place.

My newfound language of building was explored in subsequent projects, many of which are featured in the pages that follow. Each new design offered further clarity and authenticity to this approach, and eventually I became more confident and adept in my methodology. I could make a California building address seismic needs, meet budgets, and express program in simple, clear ways. As importantly, the designs focused on light and volume, place and community—the themes that run through all our work.

Looking back at the people, buildings, and ideas that informed the work, I realize that all were screened through my very personal filter. This filter focused on beauty, strength of ideas, purity of form, and public benefit. An overarching goal of clarity is prevalent in the designs of all the great architects I admired and remains to this day the single most important pursuit in my thought.

I would like to express special thanks to my children, Jane and William, to my brothers Dave, Tom and especially Paul, and lastly to Ive Kari, who have all given me support and encouragement over the years.

—Mark Cavagnero

“ I draw a character. I make him enter the house; he discovers its volume, the form of the room and, above all, the amount of light coming through the window or the pane of glass. He advances: another volume, another influx of light. After that, another source of light; still further on, a flood of light and shade on the side, etc.”

“ The street is a room by agreement. A community room, the walls of which belong to the donors.”

—Louis I. Kahn

—Le Corbusier

This book exhibits twenty years of buildings that steadfastly retain our core values: volume and light, site and community, and place and time. We apply these values we learned through travel, study, and reflection. These values are similar to those that evolved during architecture’s early modern period but have expanded with twenty-first century construction techniques and societal pressures. Our reliance on them incorporates different sites with different programs, budgets, clients, uses, and neighborhoods. The constant reliance on these values, however, gives our work consistency and thematic cohesion.

We embrace the struggle of opposing forces. We seek to balance this tension between creating a beautiful building with forming flexible and useful spaces that shape the building’s core presence. Urban land and construction costs have become so expensive that the act of building represents a tremendous will. The resultant architectural project must yield the utility hoped for, but beyond that it must express the aspirations of beauty and the core values of its era. The architect is now less writer and more poet, expressing much more with fewer available words.

An Architecture of Volume and Light

Architecture of volume is architecture of space, not mass—of human occupation, not sculptural presence. Our focus on volume rethinks conventional ideas about walls, floors, and ceilings. Each has a role as a volume-defining element, not a main attraction. The sense of containment and belonging changes the essence of order to one of purpose and comfort. Space and how we move through it becomes paramount. We understand that perception is dynamic and so we design volumes to accommodate different perspectives. Axial and formal points of view are less important than multiple views.

This focus on volume aims to minimize the object nature of architecture and prioritize its relationship to the human condition. It is this sense of volume that separates buildings from sculpture, space from void, and engaged appreciation from a more mundane experience. We limit material variations to emphasize the importance of volume. Colors, textures, and surfaces are subordinated to openness and lightness. In this pursuit of a volumetric sense of space, we meet surfaces and planes with minimal disruption. A sense of continuity is critical to carry the eye and convince the heart.

Light can augment volume, elevating the spirit and connecting the human experience at different levels. The combination of volume and daylight can be intellectually calming but also emotionally provocative and stimulating. Volumes that reach up and expand our sense of scale can even be electrifying. Consider the volumes of Greek amphitheaters, Roman baths, and, perhaps most notably, thousand-year-old Gothic cathedrals.

When suffused with balanced daylight, a volume raises our sense of well-being. It offsets the loss of nature we experience outdoors with a sense of comfort, warmth, and control. A well-lit architectural volume is an idealized, controlled, and refined version of nature made more controlled and refined. We see light as nature and nature as light and so we explore various means of maximizing both the amount of daylight and its diverse perception throughout the day and the seasons.

Daylight is the most fundamental connection to nature we have from within our buildings. It is also the most sought-after by the building’s users. The rhythm of the day, the unfolding of the sky, the movement of clouds, and the changing hue and intensity of the atmosphere connect us to life and to our humanity. Each moment is singular in its relationship to the time of day, the season of the year, and the position of sun and clouds in the sky. This highly dynamic characteristic of architecture can be exploited or ignored, used or wasted, or made memorable or forgotten.

San Francisco—a City of Light

San Francisco, where much of our work is located, is a peninsula surrounded by water on three sides. Daylight and the reflected deep blue sky are the dominant aspects of our natural world. The coastal California sky presents a powerful light, reflecting the vastness of the Pacific Ocean and the immediacy of the San Francisco Bay. A beautiful, singular quality of light defines our city. This strong California light has affected all our work. Our forms and volumes respond directly to the challenges and opportunities the sun affords.

We try to expose interior spaces to daylight from two or more directions, offering both a sense of balance and a sense of dynamic change. The result can be simultaneously calming and stimulating. Balanced daylight produces a sense of respite, of being engulfed in light and feeling

attached to nature despite having walked inside. By lighting a corner or a portion of a volume differently, we create a sense of stimulation in which people experience daylight in a different way each time they move through the space. Each architectural volume, therefore, can translate some of the richness in experience that we have in our natural world.

Connecting daylight to the human experience of nature drives our architectural minimalism as well. Unnecessary materials and forms can diminish the fundamental need for both shelter and calm. Our architecture, therefore, is directly related to this need and uses light as its cue. In responding to all aspects of light—its angle, intensity, variation, and direction—our buildings become living things. We carefully study each building in terms of the penetration of light, the striking of light, and the timing of light.

Glass is pivotal. Glass offers not only controlled daylight, but also transparency to our interior volumes, the life of the building. Connecting the purpose and program of a structure to the life of the city is critical to our work. By using low-iron high-clarity glass, our pedestrian-level facades create an intersection between the street and the interior. The activity, purpose, and life of the building becomes linked to the life of the city.

Extending a building’s view out into the landscape connects users to nature, even in urban sites where nature is best represented by sky and sun. Carefully developing the dialogue between the natural and the man-made is essential to respecting both and enhancing human experiences.

Site and Context

Site and context are critical values for us in practicing community responsibility. We develop buildings that sensitively respond to their location rather than aim for a purely monumental stature. We strive to create designs that are both beautiful forms and studied responses to their sites. This makes each building feel timeless and unique, as it would not make similar sense in any other place.

Great works of architecture are interlocked with their immediate site and the larger community simultaneously. We analyze the adjacent buildings, the larger block, and the fuller neighborhood around our building site as part of its essential community. Our goal is to connect.

Using the same materials on our projects as those of its immediate neighbors is often avoided. In our most public buildings, which warrant distinction from the repetitive fabric of their immediate surroundings, we try to do both. That is, we establish the unique character of our works, and at the same time reference and connect them to their neighbors. Ideally, our buildings can both complement and be counterpoints to their vicinities.

We use simple tools—materiality, color, surface texture, and aligning key datum lines, such as window openings or cornices—to connect our new designs to existing fabrics. We relate to the scale and proportion of adjacent structures and their openings. Wall depth and shadow reveals are important in establishing the rhythm of a block. Continuity yields harmony and urban satisfaction; discontinuity can cause an abrupt visual dislocation.

An architect should make the block of a new building better—more interesting and cohesive— not more distracting and adversarial. The nature of the project should always be apparent in its design. Expressing a building’s program and use should make it exciting to the city and inviting to the public.

Architecture as Community

Architecture utilizes various means of connection to reinforce a fundamental sense of community. Architecture reflects a community and its ambitions, whether by intention or default. It can yield buildings that clearly represent the best values and goodwill or, by avoidance or apathy, reflect self-interest and individuation, or avoidance and neglect.

Building in the larger community of California is a complex matter. Its history is rich, and its racial composition is highly varied. Many subcultures form this place, from the original Native peoples to the Mexican and Spanish settlers to the Gold Rush European immigrants searching for fortune. Each group brought its own culture, language, and expectations about building community. Over time, California developed its own sense of place and character, proud to be different, proud to be on the extreme coastal setting facing the Pacific Ocean, and separated from the rest of the continent by the rugged Sierra Nevada mountains.

Physically, the sunny climate is both pleasant and demanding. Meanwhile, a high seismic threat requires specific safety measures not common in most American regions. Our goal is to meet these California conditions with authenticity—not with a West Coast style but with substantive, thoughtful responses. Our buildings garner the sunlight but minimize the heat; they ground into the land itself but are stabilized from seismic activity. The forces are distinct and often at odds. California requires great care.

Architecture as Thoughtful Integration of Forces

Architecturally, we use the integration of frame and wall to meet the demands of our locale, to express these opposing forces inherent in the land and climate. The understanding of a wall and a frame as two entirely different constructs helps us pull apart these California threads.

The wall carries light along its surface but blocks it from entering. It brings seismic strength to the building as well. The frame offers openness, transparency, and daylight critical in successful community-based public buildings. The dialogue between the frame and the wall is unique for each project and relates to its program and site. Used properly, the dialogue speaks to the contradictions that define our Western region. The contradictions in architecture, like in life itself, yield richness, interest, and balance when carefully controlled.

Sustainably, our detailed efforts begin with minimizing heat gain in the warm California climate. We carefully site each building to minimize the sun on western facades and low-angled glare, with its concomitant heat gain. In controlling sun exposure, we need to accommodate both the desire for balanced daylight and the equally important need to minimize glare and heat.

Financially, many of our projects are tightly budgeted public works. Therefore, the careful use of walls to carry the seismic strengthening requirements allows open frames elsewhere to allow visual connection to the surroundings and maximize daylight. Furthermore, our concrete structures utilize the wall elements for more than seismic strengthening; these walls also yield fire resistance and acoustic isolation. The multiplicity of tasks means that each system component is integral to the design approach and works in a variety of ways to make the building perform. Unlike our corporate clients, our public-sector clients rarely have sufficient funds to maintain their buildings, and so we choose durable materials for their projects.

Each new building design has offered the opportunity to develop further clarity of thought. Each struggle for authenticity brought more confidence in methodology. The pages that follow exhibit fifteen projects that attempt to find such authenticity, this sense of character and place unique to the site and time of its making. Their order is roughly chronological to bear witness to the core ideas as they developed and adopted to new building types in larger scale work. The chronological sequence roughly coincides with the firm’s growth in scale of projects over time. Each new and larger project brings with it the challenge to grow and adapt our core ideas to newer and larger situations and program complexity. With each successive project we strive to reduce our words and find the poetry inherent in the work. This excites us.