For our joy, and for the glorification of Christ, forever, He who fills all things, and without whom there was nothing made that was made.

For our joy, and for the glorification of Christ, forever, He who fills all things, and without whom there was nothing made that was made.

March 23 - April 4th, 2020 Thought Pyramid Art Center

18 Libreville Street, Wuse 2, Abuja

Written and edited by Amarachi Okafor

Published by ORIE STUDIO, 2020, Abuja, Nigeria

© 2020 Amarachi Okafor w w w.amarachiokafor.art

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher.

Published by: ORIE STUDIO in 2020

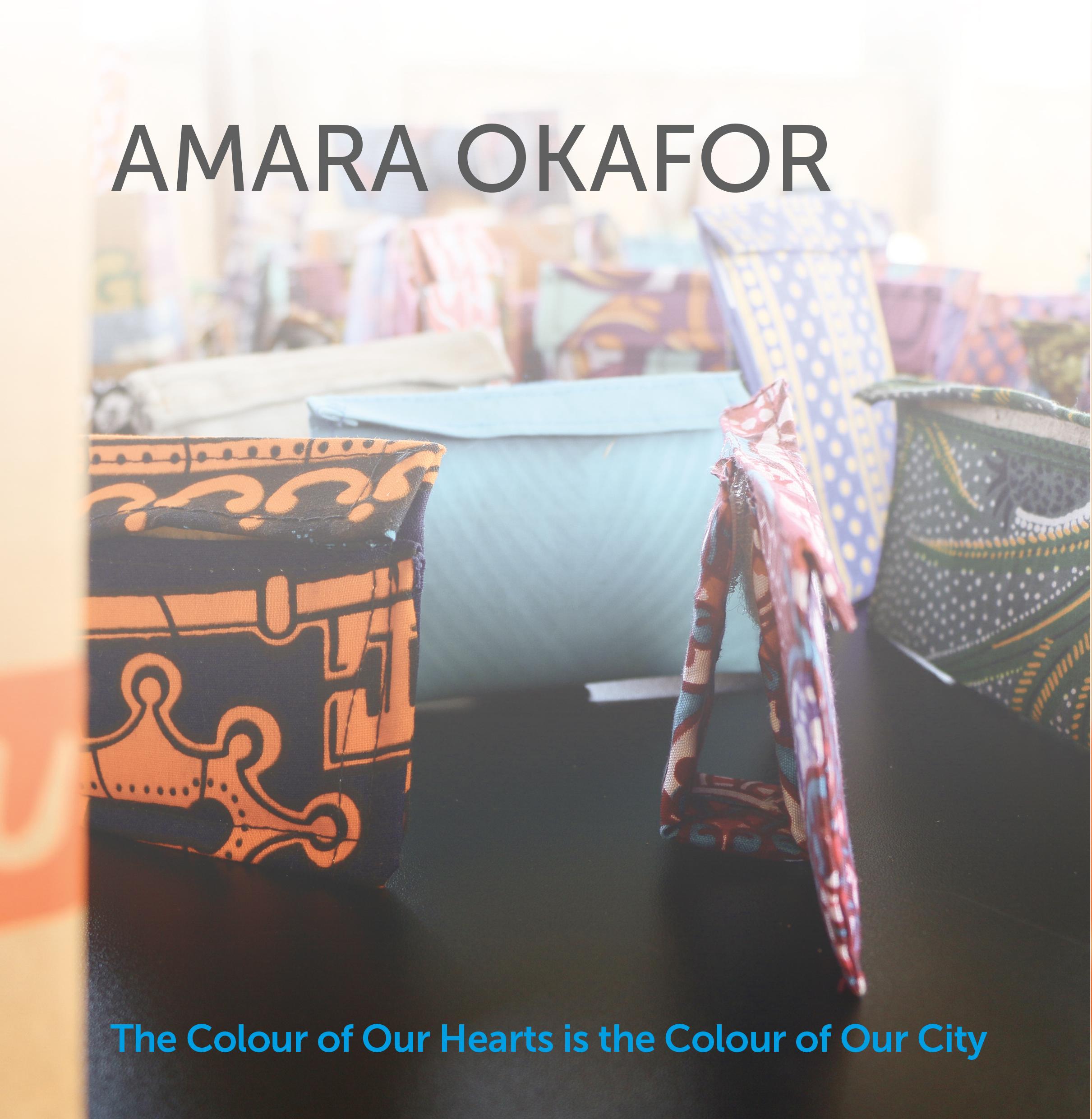

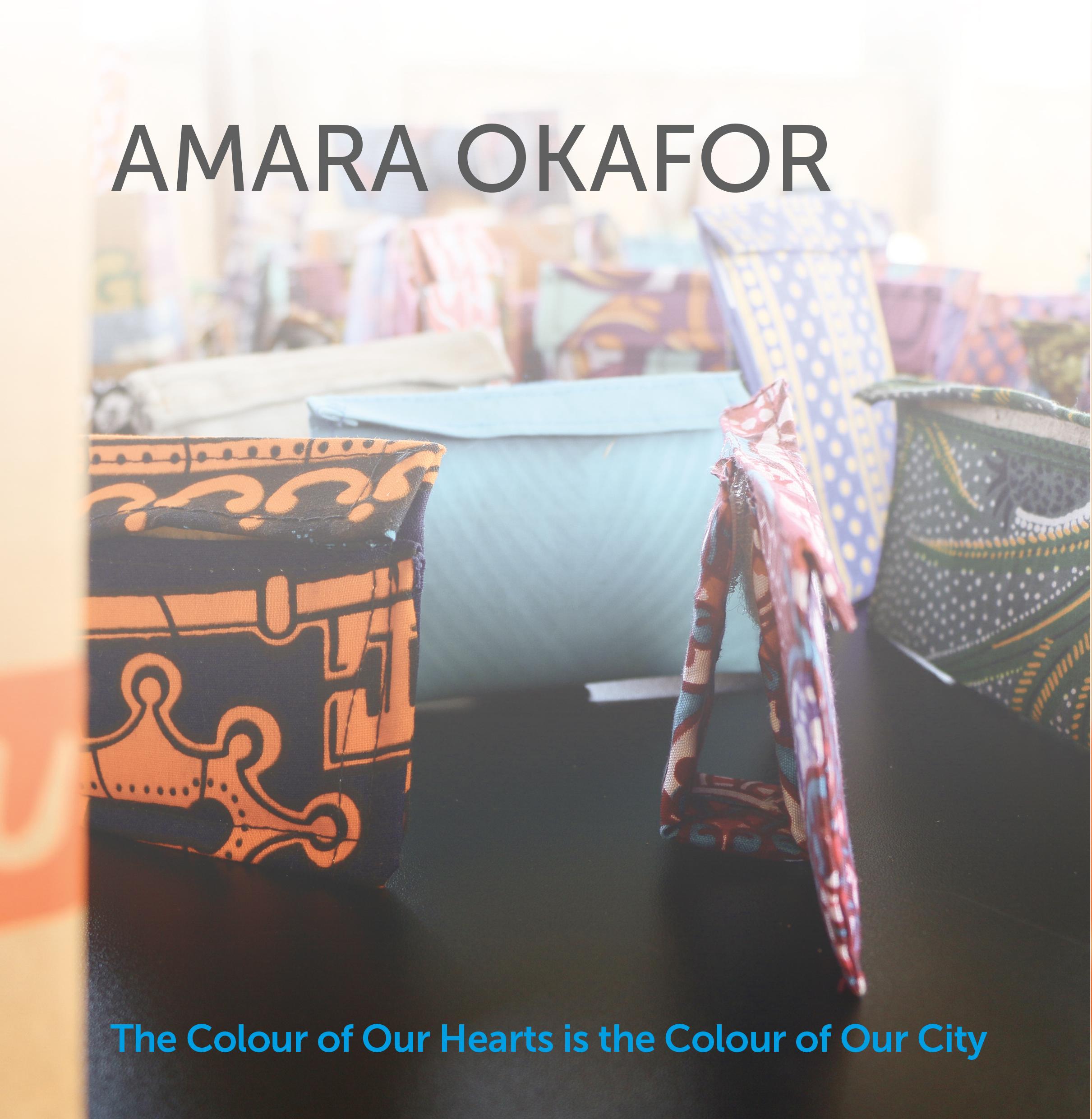

Cover Images: The Colour of Our Hearts is the Colour of Our City, 2015-2019 by Amarachi Okafor, variable dimensions, multiple media

Photo: Amarachi Okafor. Collection of the Artist, Karu-Nasarawa-Nigeria

Cover & book design by Julia P. Ames

ISBN 978-978-979-799-8

The Colour of Our Hear ts is t he Colour of our City poem by Chukwuemeka Akachukwu 6

Introduction 7

The Colour of Our Hear ts is t he Colour of our City, 2015-2019 8

Anya ’ri Umunne, 2019 12

Doughnut and Egg, 2019 16

Bright Room I: Illuminate, 2018- 2019 20

I Am t he Light III, 2019 24

I Am t he Light IV, 2019 28

Conversation wit h Amarachi Okafor 33

Lost Trut h and How We Got Tired of Seeking, 2016-2019 36

Onwa (Moonlight), 2010 40

Okpangu (Chimpanzee), 2010 42

Untit led, 2003 46

Faltering Toget her–Towards t hinking t hrough t he collective body essay by Jenke Van den Akker veken 48

Substance and Emptiness, 2004- 2015 52

How to Frame and Please Six Women at Once, 2019 54 Unction of t he Holy Spirit, 2006-2019 58 Herdsmen Bagged, 2017-2019 62

Is your hear t colour ful?

Is it blue, yellow, or red?

Is it purple, green, or brown?

The colour of our hear ts is t he

Colour of our city; it is our talk and laughter, Our solitude, our attitude.

In gold, brown, and grey, White, pink, or black, pray and Live…

Like a carnival train; Flamboyant ly, luminously, and free…

Is your hear t colour ful?

Will t he blue mix wit h t he red?

Will t he yellow glow at night to illuminate dark hear ts?

Will your green flow into t he city when all is dr y?

Will your blue flow into your neighbours’ sky?

The colour of our hear ts is t he colour of our city;

It is t he way we Pray and love, The way we eat and fuck, Our road rage, swear-words, and fake life. Our tenderness and kindness.

The colour of our hear t is our work, our hope, and Our success, Our failure, sadness, and frustration, Our ambition, perseverance and, future.

The colour of our hear t is t he way we see…

The way we sleep, t he way we t hink

Let t he colour of our hear ts flow into

The streets like t he stream, gent le and calm, If the colours become muddy, the city will become muddy too

For t he colour of our hear ts is t he colour of our city

–Akabeks, 2020

Chukwuemeka Akachukwu is an ar tist and poet, trained at University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He is based in Abuja, Nigeria.

How are we living in our cities! This is a reference to my city, inspired by my perception over time living and traveling in number of cities around the world. How do we live and how do we love?

Abuja, Umuahia, Lagos, Trondheim, Münster, Cornwall are cities some of where I have lived, and each of these cities have or offer different energies about them not due to their name or location, but due to the energies that the people living in them give out and translate to one another.

The colour of our hearts individually, is the colour of the collective result that we ‘enjoy’ where we dwell and where we participate. This is indeed the summation or the consequence of whom we essentially are as persons and as humans present in a given space.

What is my contribution ‘in colour’ to the spaces where I am given to be active at – Black, Red, White, Green, Pale, peaceful, Cool, Harsh or Ugly –?

Our vibe contributes to and can determine or affect the general vibe and energy of my entire city! Each one of us is a key stakeholder.

With this artwork, each pouch including its’ content stand (in) for man, one man. We are sealed bags full of secrets, full of sourness, joy, hope, gratitude, env y, love, kindness, compassion, empathy, jealousy, selfishness, pride, depravity, cheer; which of these possible contents is abundant in me, and hence, in my city because of me?

In general, do I enjoy the people in my city? Why so? Why not?

What kind of ingredients would I enjoy from codwellers in my city? How shall we multiply these ingredients to have an enjoyable city?

What if we each bore a grateful heart whilst in this Space today- mightily grateful; and shall we say a prayer for one another, for our city, leaders, families, friends and neighbours.

Pray:

Whilst here in this sacred space that is ours today, shall we hone and hold gratitude and compassion in our hearts for all these people thankful that we are here and that we have one another in this city. Let Love heal our hearts!

Think:

What do I bring to the rest of my co-dwellers in this city? How can I be more thankful? How can I give more? What more can I give? How can I love more people more? Whom can I love?

Do 1.:

Select a pouch that you can relate to, please write down your feelings on the prayer note within the pouch (please do not write about the art, the artist nor about the exhibition). Write about you, your appreciation and enjoyment of your city; your (hoped for) contribution with your presence in this city; your prayer for this city, people (especially the poor), and leaders.

Do 2.:

Return your note into its’ pouch. Let us know if you want it sealed I am praying with you also for our city If you like, you may sit with the art in silence. Peace.

The Colour of Our Hearts is t he Colour of Our City, 2015-2019

Variable dimensions, multiple media

An Installation of 2019 pouches with prayer notes for audience participation and engagement.

Photos pages 8, 10 and 11: Godswill Ayemoba

Photo page 9: Amarachi Okafor

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

44cm x109cm, stubbed cigarette filters.

Photo: Amarachi Okafor © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Doughnut and Egg, 2019

17cm x 89cm, stubbed cigarette filters.

Photo: Amarachi Okafor © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

105cm x 95.3cm, (unframed), mixed media, handmade paper.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

I Am t he Light III, 2019

100cm x 400cm, multiple media

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

100cm x 400cm, multiple media.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Ozioma Onuzulike: Amarachi, you have been working on the idea of what one may describe as an intriguing form of “public art” for some years now, and you are adding to the growing list of such exhibition projects at this time. Can you recall when and how this idea came about and how you have engaged with it over time?

Amarachi Okafor: Yes, I do recall. It is rooted in several decisions that I made during and after my study for MA in Curatorial Practice during which time I thought a lot really deeply about my art practice. It was tough thinking in those days, and still. I was at a sort of junction where I knew I had to take one path or the other So, I took both, in my own way. I stayed the artist, and I also became the mediator of art for audiences. I think that the second agenda is necessary in Nigeria where we often complain that only a small section of the population understands or consumes (contemporary) art. So, this is what I do. I try to take art to the people in their own spaces - markets, offices, schools... In August last year, for example, I took it to my local church and worked with young people aged 217, with ‘I am the Light’ project. So, I curate these projects, and instead of ending up a writer, which was also an option for me in my journey, I took the action to my artwork. I am still testing!

OO: I see. So, can you describe what it is that you are testing in this instance?

AO: I am testing to locate a position or place where I am honest in my work, a place where I am at the same time deeply fulfilled in my practice. This is what I meant when I said that. But I am testing my stance and my strides in this long journey. I am testing myself and searching my heart and my soul for what I am being called to do or say with art–what can be the purpose of art in this crazy and painful world, and what is my own assignment in the middle of it all? I am testing my audience. I am not sure that anyone will like my work or this exhibition. So, this is a test! I do not know if people will show up, or if they would understand me? When I take my work to the public, I usually have to physically bring people, individually, to the work and say “Look... this is about such and such...”. I am testing my media. The objects that I make are mostly a test. For instance, I have never seen the major piece in this exhibition completely laid out, so this is a test for me to sort of see the work. This exhibition will only show a fraction of the work.

OO: So, what is the current show specifically about?

AO: The Colour of our Hearts is the Colour of our City. Cities are made and built by people - all the people in it, not just some Each one of us is a stakeholder. It is not ‘them’, or ‘they’; not a question of “Na dem sabi” It is all of us! How does each one of us support

to make our communities better or worse? How do we care for one another or not? If I am enthusiastic or have a joyful personality, it catches on to the people around me and to the wider group, and if I am nonchalant or even hateful, it catches on too. All it takes is time, but it must establish and develop. I think many Nigerians, in the big cities especially, seem very angry, bitter people. We are greedy and selfish too. We can be more pleasant if we tried. It is said - Tell me where you live, and I shall tell you the kind of person you might be. In my small group, in this nation, how do I support to make the education system better or worse, for example? Why do we kidnap our brothers and sisters to gain things? An Igbo proverb says Onye nwere mmadu ka onye nwere ego (He who has people is greater than he who has money). Did our ancestors/parents teach us this?

OO: What is the creative or artistic strategy you will be using to draw people into contemplating these issues or to inspire them to ruminate over these questions? In other words, can you speak about the material framework you have in mind to deliver this project?

AO: Text/words and performative actions of reading and writing. We would also sew, if anyone wants to, they can sew with me meditatively, to seal the words they have written into the body of work. I plan to have the atmosphere of the exhibition sober, enabling and encouraging ref lection. There would be signage in the space

that would explain the situation and instructions on how people can participate and the issues that we are to deliberate on whilst in that space. It would not be a party at the opening; it will be sober and introspective. This is my plan. I hope it works. There will also be other works in the exhibition that speak about other things - paintings and sculptures.

OO: What forms do the painting and sculpture components take? What are the media and content and how do they intersect with the performative component of the project?

AO: They do not intersect so much, although there comes some text here and there on some of the works such as I am the Light Series which in fact is a result of a public art event. It is also possible that they intersect where I had not intentionally meant that they should since I am the same artist feeling the same things in my belly. They are mostly mixed media - acrylic, tempera on canvas, on/with handmade paper (that I made from local fibre); fabric, sewing threads and embroidery, synthetic leather, bags, stubbed cigarette filters. The piece with synthetic leather and bags is titled Herdsmen Bag ged, and it means just that - literally. Another, Lost Truth and How We got Tired of Seeking is a triptych acrylic and tempera on canvas and is about politics, leadership, the news and the issue of ‘the more you look, the less you see’ to the point where it begins to seem that they are

toying with our intelligence. It is kind of an extension of a sculpture installation that I made in 2010 with plastic bags, titled Cover Story.

OO: In my mind, the works you have described relate very much to the very theme of the current performative project, “The colour of our hearts is the colour of our city”. Do you intend to have the audience see these works before, during or after their participation at the art event, “happening” or performance? How do you envisage that things will go and why?

AO: My work is not Performance. I am not a performance artist (laughs). Yes, they are events. I call them relational events. All the works will be in the same gallery space. I suppose the audience will go to whatever attracts them (first). I think they might be baffled, perhaps a little confused because this is not the usual occurrence in that gallery (I think). In my experience, the audience would like the paintings because they are pretty and quite bizarre. I reckon we sure would have a lot of explaining to do.

OO: I see. You may not be a performance artist in the usual sense of the word but you appear to be enacting a performance by involving real people via a performative strategy. So, tell me a little more about how you plan to get the audience involved in this event beyond their merely looking at the paintings and sculptures and, may be, asking questions about what they see.

AO: Oh, pardon me, I have not been quite clear. It is only one out of the 13 works in the exhibition that is audience engaging. This is the sculpture installation titled The Colour of our Hearts is the Colour of our City, 2016-2019. This is also the title of the exhibition. The other twelve artworks are not to be engaged with in the same way that this is. These twelve are the paintings and sculptures that audiences can merely look at and maybe ask questions about what they see. For the Installation that gives the exhibition its’ name, we would guide the audience through their participation. At each location, I usually have a team of people that work with me. The team is pre-trained before any event to understand the work very well. During our pre-event meetings this time as is usually the case, we would try again to pre-empt audience reaction to this piece and deliberate on strategies for responding. Some members of this team have been part of my relational event programs from the early days with Ask Yourself (2014) and this is a good thing.

It can be like the way hawkers move during traffic jams - they watch the direction of your eyes, and if they catch you engaging with their goods then they quickly come at you saying “‘bottle’ water, 50 Naira”. So we’d be hawking our art (idea) and teaching via this process. We are also careful about not harassing people, following best practices, very considerate of the artwork and strategic to deliver the

message. I shall sit in one place mostly, in a peaceful costume and sew. There would be a desk and seats for people to sit at and write.

However, this process is very dynamic. The conversations that come out of these events are the most exciting part for me. They are ephemeral and lasting at the same time. They also have the capability and possibility to rebound, so I can say that this is quite an important dimension to the artwork. You never know who would show up, what questions they would bring on, and what topic they would digress to, branch out and keep going...

I want things to be sober at the exhibition. In my experience, managing the audience can get loud and complicated indeed. Well, here I have it planned out, but each location is always different. I shall try, but then this is life, life happens...

OO: It is interesting to me how you bring to bear your training as both a visual artist and curator to bear on your practice. It appears that you have dedicated yourself to educating your audience in ways that seek to make them aware of how art is life itself. How has that worked in your past projects and what is it that propels you to do more?

AO: Grace propels me to do more. Yes, I believe that art is also a vocation, a calling, an assignment given to ‘those who have been called’. Only to them. Not to everyone who trains as an artist. Am I one of those? Time will tell. If one takes on art, isn’t it almost like setting

off to ‘Mission’? Creativity is a gift and should be used to serve. I believe we are given skills/wisdom for life so that we can use this to serve others. It is not for us to make money with since whatever ‘things’ we need will certainly follow us if we try and serve well with the skills that we are given. How has the educational angle in my work worked in my past projects? I am not exactly sure how in terms of results. Things that count usually take time to develop, it can take even beyond our lifetime and this is why I said at the beginning that I am testing. I am quite open to a new dimension for tomorrow even though I am happy to watch this develop and to indulge in it. I do think that I have some kind of passion for education.

On the other hand, I know that my audiences usually pick up new knowledge during the conversations and interactions, some are surprised and question how this is art. I remember a high school student asking - during the Jogjakarta Biennial, “Why have you made a painting half way with some text, and you have brought it here to ask us questions with this? Isn’t artwork perhaps the drawing of a bird, or trees, and things like that?” I responded with something like “ our smallest activities in life or even in art today get written in history and tomorrow become the reality of that past. So, I am doing this which has occurred to me to do today- and tomorrow we would see what it becomes.” I think that with my processes, I can push any agenda or any subject matter to the world. It is quite

great and exciting! I pray that I manage to remain on the path of good causes alone.

Ozioma Onuzulike, artist, poet and writer, is a professor of ceramic art and African art and design history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Ozioma.onuzulike@unn.edu.ng oziomaonuzulike.com

Lost Trut h and How We Got Tired of Seeking, 2016-2019 130cm x 328cm, Acrylic and Tempera on Canvas.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Onwa (Moonlight), 2010 48cm x 135cm.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Okpangu (Chimpanzee), 2010

39cm x 77cm, mixed media.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Untit led, 2003

20.5cm x 35cm, mixed media on masonite.

Photo: Tersoo Gundu

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

These are the words spoken by the British painter Charles Ryder, the fictional protagonist of Evelyn Waugh’s 1945 novel, during a sleepless night in a sophisticated hotel room in frenetic New York. The fact that Ryder shares a room but not a bed with his wife, to whom he has just made love with the utmost formality, is a not unambiguous detail that heightens the context in which the words are uttered. Although Charles Ryder was speaking in the 1930s, his statement still rings true today. It seems to epitomise our own hectic lives, and the way in which we are thrown back upon ourselves to such an extent that it distorts our mutual relationships.

We live in a neurotic society, one that traps us in a perpetual quest for meaning from an intensely personal position of self-realisation within an oppressive, neoliberal framework of ‘ never (good) enough’. We launch ourselves into mindfulness, meditation (transcendental or otherwise) and yoga, just to be able to more or less hold our own in the rat-race into which, under the threat of social and existential exclusion, we are forcibly sucked. Twenty minutes of daily healing in

–Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisitedorder to feel that we matter for a day and to achieve a semblance of meaning: a cost-benefit analysis that we endure and pass with f lying colours.

Or not.

We heal, yes, but have become the sticking plaster on the wound of society. Maintaining a ‘healthy’ state of mind has turned into an obsession, something that we strive to preserve at all costs because we fear what will happen if we don’t play along –although it is not always clear what it is that we are supposed to be ‘playing along’ with. But as with any obsession, it masks an altogether darker reality. For all we might want to believe that this reality is one of toxic gluten, prehistoric lactose intolerances and stress caused by an imbalance in our work-life balance, those who dare to scratch beneath the surface will realise that banning bread, doting upon Buddha and introducing f lexible working hours amounts to nothing more than managing the symptoms of a neurosis, a strategy that skirts around the real problems. We are teetering on the brink. Anyone on the verge of collapse or who plunges over the precipice will be thrown a mindfulness

lifeline or handed a sponsored pill, but will also be expected to reattach his wagon to the runaway train.

So far, the deconstructive and somewhat cynical introduction.

Deconstructive and cynical, yes, but also an essential foundation for answering the following question: “Which thought mechanisms allow us to hold our ground today, and dare we face the future?” Only by unravelling the neoliberal fabric in and behind which we all hide from the meaninglessness of our existence, only by confronting the fundamental issues that have led to it being woven in the first place, can we try to answer the question. If we shirk this responsibility, and go looking for answers within the seemingly protective but actually suffocating fabric itself, our thinking will then be reduced to mere symptom management.

There is a danger to this approach, however. After all, we are so tightly fused to the fabric that it has not only become our blind spot, but has also turned the necessary act of taking distance – even if only temporarily –into a precarious undertaking. By

Towards t hinking t hrough t he collective body

“…for in that city there is neurosis in the air which the inhabitants mistake for energy.”

unravelling the fabric, we slowly but surely undermine the ground beneath our feet, the certainties on which our lives are based, the thin layer that separates us from the abyss, from the void. Before we begin the process of disentanglement, therefore, we need to find collective anchor points that we can latch onto, and which will help steer the quest for meaning that inevitably follows. But how do we map those anchor points? And how can we be sure that they won’t give way or are not simply the knots within a new, unstable and deceptive fabric?

Before answering this question, we need to address another crucial issue within the neo-liberal society. And this problem appears to be one of the noblest elements of its ideology: freedom. The defence of total individual freedom has become the burden of total individual freedom, with all of the attendant consequences for our fragile sense of identity. It is a hard-won privilege, but everyone now has the freedom and right to construct an identity based on personal beliefs and interests, values and norms. But at the same time, it is assumed that everyone knows how to do this and is able to create an identity within a state of utter liberty. Paradoxically, for those who cannot find their way, this freedom is not so much a triumph but a burden. The quest for identity then becomes a slippery slope that leads to the stress of having too many choices in an endlessly changing context, the result of which is an extremely superficial

interpretation of identity that alienates us not only from one another but also from ourselves. While this freedom should be a source of unlimited possibilities, it ultimately leads to doubt and stagnation.

Absolute freedom, when devoid of any directional anchor points, results in us locking ourselves into our iCocoons, within which we click and swipe from identity to identity, both on- and off line. We live in an age of unprecedented connectivity, yet the only thing that truly binds us is our shared loneliness. Perhaps the neoliberal fabric is not a safety net that spans the abyss, but a loose collection of rickety, individual rope bridges that have been thrown across the chasm?

We are so busy reinforcing our own tiny bridge to stop ourselves from falling that we lose sight of the others, thus forgetting that the ropes on which we are all neurotically faltering are, in actual fact, identical.

Only through this realisation can we begin to answer the question of where we might find those vital, solid anchor points that will ensure that we, both as individuals and as a society, can stay upright, heal and move forward. We must dare to seek, once more, the deeper connections that transcend superficiality and touch the existential. And those connections can be found, for example, in shared rituals. Rituals are part of our collective memory and enable us – as a group – to express and give meaning to fundamental questions

about who we are, where we stand, how and why we are here. Through the ritual, we share our traumas. Through rituals, we are able to break the vicious circle of our empty neuroses.

In a nutshell, a neurosis emerges from an inability to ascribe meaning to ‘things’. A psychotic person plugs this gap by creating their own reality and corresponding system of meaning, whereas a neurotic one will circle around this rift by using existing systems of meaning: words, actions In this respect, we might just as easily describe the ritual as a neurosis. The difference, however, lies in the fact that when the ritual is performed, we recognise it for what it is: a rite that offers a form of control over the uncontrollable, a calibrated formula that is very consciously repeated in a certain context. A neurosis is an unconscious process that offers the illusion of control, yet is actually uncontrollable.

At a time when the focus on selfrealisation seems to overshadow everything else, we need collective rituals more than ever, especially when this emphasis, combined with the aforementioned burden of freedom, makes rituals disappear and labels them as irrational, naive, restrictive and (thus) nonsensical and even dangerous. Yet in the history of mankind, across time and cultural boundaries, we find rituals so powerful that they appear to have retained their significance for hundreds or even

thousands of years, albeit redefined within ever-changing contexts, although often without much formal development. These are the rituals that touch upon fundamental, communal traumas and which have the capacity to heal us.

An example.

The ancient Greeks offered anathemata [gifts] to the god Asclepius in the hope that he would cure their illnesses and injuries, or to thank him for his acts of healing. His altar and its sanctuary would be piled high with terracotta arms, legs, breasts, penises, eyes, and other body parts. So numerous were these objects that they would be buried around the perimeter of the temple so as to make way for new offerings. Christianity assimilated this tradition and for centuries the devout would string body parts in terracotta, wax or silver above the tombs of saints in an attempt to make contact with a higher realm, hoping to be healed. These so called ex-votos swung in the wind, between life and death, next to f lickering candles, and together created a single hybrid human body. It was not the leg or the arm that was offered, but a fragment of the ‘I’ so that it could be healed as part of a shared physical form. Together, the ex-votos constitute the suffering, amorphous collective body, one that can only exist through the sacrifice and ‘disembodiment’ of each individual. Until the 1980s, clusters of ex-votos could still be found in churches and chapels around

Belgium, and one only has to look at the anatomical wax milagros hanging from the ceiling of the Church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim in Salvador, Brazil, for example, to understand that this healing ritual still persists today, after more than two thousand years.

This example was not chosen as a plea for a return to Catholic rituals. Nor does it mean that we should all make offerings instead of practicing mindfulness if we want to ‘heal’.

However, the ‘amorphous collective body’ created by the ex-votos offers a powerful metaphor for the subject that this essay aims to open up: the idea that healing – in the broadest sense of the word – will never occur within our present day society through a focus on self-realisation and the free individual, but rather from a sense of connection with the collective body of which we are all a part, and to which expression is given, for example, through rituals.

This is purely theoretical. Of course. Because this essay does not pretend to offer a solution in 2,000 words to the problem that it addresses – it is too dependent on neurotically chosen words and metaphors that are trapped between meanings. Yet it does offer a concrete and unambiguous answer to the question “Which thought mechanisms allow us to hold our ground today, and dare we face the future?” At the same time, it also aims to point to a possible direction in which we can steer our thoughts. By thinking through the collective body, and thus

embracing rather than repressing the so-called irrationality, naivety and limitations of the ritual, we might be able to create an opening in the prison wall of the place in which we were meant to be ‘free’. In so doing, we could break the vicious cycle of our neurosesfuelled lives and change course. Perhaps this is what the areligious Charles Ryder, with whose words this text began, feels when he kneels before an eternal f lame in the epilogue to Brideshead Revisited.

Jenke Van den Akkerveken is a Belgian art historian, with a special interest in iconology, anthropology and Lacanian psychoanalysis. She currently works as an independent art book editor, researcher and writer.

78.74cm x 195.58cm, (Unframed) mixed media.

Photo: Amarachi Okafor © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Amarachi Okafor © Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

to Frame and Please Six Women at Once, 2019

31cm x 155cm, Plastic bags, fabric offcuts, handmade paper.

Photo: Amarachi Okafor

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Unction of t he Holy Spirit, 2006-2019 120cm x 99cm (unframed), mixed media.

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Photo: Patrick Ebi Amanama

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

144cm x 85cm, synthetic leather, bags, copper wire, wood.

Photo: Amarachi Okafor

© Amarachi Okafor and ORIE STUDIO

Thanks so much to you all, my dear family and friends for your support.

The team at my studio, Thought Pyramid Art Centre (Jeff and Iyke), Austin Oliver, Jenke Van den Akkerveken, Oh Seok (Oso), Helen Simpson, Ozioma Onuzulike, Akachukwu Akabeks, Julia Ames, Adolphus Opara and more…

I wonder what I would do without you? May you always gain many graces, Amen!