ARTIST’S STATEMENT

Transformation of material and the several ideologies of use are my foremost motivations for making art.

This is also my central approach to production.

Concerns in my work test socio economic themes involving topics that deal with human relationships, culture, religion, history, gender, sexuality, and the boundaries where we as humans can or cannot accommodate these phenomena.

To make art, I tend to choose materials which through their specific characteristics, reference these topics; and are capable of reflecting on the diverse contexts from where they are sourced. I prefer to involve as material, substances associated with use, hinting on our associations with objects. Each material that I employ into my work embodies a memory, and therefore a voice, acquired from a handful of experiences from its lived life. My ‘About Black Series’ adopts the use of an object that is very ordinary in Nigeria–the black plastic carrier bag, used every day in the shops and market places.1 This use of a common item is chosen because of its general invisibility, even when it is so familiar. In this piece, it is transformed into a significant monumental installation.

This is a recurrent approach in my work. The final construction of my artwork and the context for showing it is important, as this is always dependent on the concept.

Sewing is a special process for me, stemming from my interest in design and architecture, but also through my tacit knowledge of the process of dressmaking which I associate with the

women in my native local community. I have also trained locally to develop this process.

Clothes have followed people’s lives literally very closely–with all that this implies. I notice also that my immediate society is a fashion conscious one. It fascinates me that in Nigeria; fashion becomes a contest among the wealthy as well as among the humble. More important is my perception, that the patching and mending of every pliable broken piece of material that I adopt into my work, is the healing–of these bits and pieces, as well as of me, in an unpredictable society. Hence, my sewing processes are long drawn sessions, alluding to remedies of systems in my native society.

My preferred method of working is to address an inspiration, sourcing materials or processes, which lend the most appropriate voice to this idea. The concepts in my work sometimes supersede the actual materials that I use, as I do not like to restrict myself to one material only, and therefore the processes and connotations that probably must be associated with this single material. Usually, this takes me through a variety of approaches in my work, providing me with wider freedom of expression which I generally find very stimulating. Recently, I have found it even more fascinating to draw on curating as a process for making art or a platform for delivering my artwork. I am influenced by the experiences I have in whatever environment I am in at the time, which includes my community, my country, or even when I travel to other places around the world, exploring what I see and responding to it.

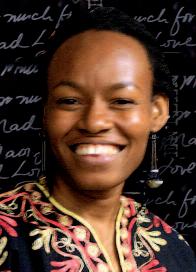

Amarachi Okafor The Producer

I am Bahamian. I eat Conch Salad

1 Ref p 40 8

QUESTIONING THE CANON: ART AND THE MUSEUM’S SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

Art as an idea has continued to sustain its age long controversy regarding its realm of reference. The development of the modern museum in 1830 seemed to have compounded the notional grounding on which the idea of art could appropriately be structured. The museum as an institution is a public site that receives, keeps, and makes art available to humanity. However as Stephen Bann (1998) notes referencing Maurice Blanchot, humanity created art in order to live with it, but the museum institution by its structure, creates “a situation of almost metaphysical ‘lack’ which the work of art suffers by its reluctance to find a home in the world” (1998: 238).

The realization of the way the museum has stood between man and the art object has been responsible for various efforts made in the recent past to retool and to reinvent the value and function of the museum and its space towards enhancing its social goal and responsibility Central to this effort at making the museum relevant is the reinvented canon of presenting the work of art dubbed ‘installation’ That persistent search by the museum to rehabilitate art in its metaphysically ensconced space refocuses our attention to a proper definition of art with attention to art as ‘what humanity has made, to live with’

Linked with the above problem is a larger dilemma associated with the gate-keeping ideology and fostered by the enlightenment epistemology which funds the discourse of difference or the otherness syndrome Implicated in this ideology is an overt claim that it is with the West alone that authentic art is experienced This problematic is enmeshed in postcolonial indeterminacies With the postcolonial rhetoric, it

is important thus to locate the value of art as cultural practice and product in the way that it is conserved and represented to humanity in the museum environment, or exposition-inspired activities like exhibitions and installations. These foundational observations raise some pertinent questions; firstly, what is art? Second, what is the relation of art to museum objectives for the human and the society? I therefore attempt to develop the distinctive principles that these questions suggest, and go beyond them to posit that the seeming indeterminable essence of art has often been tied to attempts to define art in reference to its use. Thus, the invariant core of art is different from the various practical purposes it has always been adapted to.

Contemporary notional grounding prevalent with art as an activity bound to culture in Africa, is largely the product of a received civilization from the West. This conceptual grounding is traceable to enlightenment, and European culture. In essence, the philosophical underpinnings that currently inform art as an idea is largely Euro-centric. Consequently, this analysis will draw on the cultural adaptations that art has undergone in that background, to aid the clarification bid of this essay.

The problem posed by this idea of art is the divorce of art from humanity as fostered by the museum Museum aesthetics presents objects [the artwork], against subjects [the human being, its maker], within the context of ‘distancing’ In the museum, art is encountered in exulted shelves now located in enclosures This divorce had generated continuous adjustments since the 1830’s when the first public museum was

9

formally instituted in France, all in an effort to reunite art and its maker (the human). Stephen Bann, referencing Bortiger provides a lead on how art had come to be debased.

The Greeks had seen the function of Art as being inseparable from religious and public functions. The Romans had began the process of deterioration by making Greek itself an object of aesthetic contemplation. The modern museum had completed the process of devising a new form of institutional display in which the works were by definition cut off from their original function (p. 237).

Professor C S Nwodo responding to a similar dilemma regarding philosophy of fine art and aesthetics (1984: 195 – 205), establishes three important points that will aid our efforts in this clarification These are that authentic art in the first place is not created to evoke an object/subject relationship as it appeared first among the Romans in their admiration of Greek Art Secondly, reading Martin Heidegger, Nwodo observes that the real objective of art is the disclosure of the “Being of Being ” And finally, African art and indeed authentic art was never created for the museum

Highlighting further on the nature of art, (as situated in the African cosmos) he furthers that art did not develop out of religion, quoting Isidore Okewho who also says that in Africa “Art came to the service of religion only after the craftsman had attained a credible sureness of hand ” In this understanding, he re-emphasizes the ontological status of art An important point to note is the complexity of museum aesthetics as understood within the enlightenment epistemology This is that any object worthy of museum space must as a matter of necessity be devoid of instrumental value, or assumed to be so in such respect The

idea that African art is fundamentally a product of religious worship, (as theories on African art are directed in most texts) is aimed at discrediting the aesthetic value of African Art; a situation that foists on the genre, a non-art status. The way the identity paradox has played out in recent exhibitions will be focused upon in due course.

What then is art as an essence? Professor Nwodo quotes Professor Chinua Achebe for whom “Art is, man’s attempt to create for himself a different order of reality from that which is given him, to offer himself a second handle on existence through his imagination” (Nwodo, 197).

In Michael Podro (1982: 7) three philosophers also highlight Achebe’s position. For Hegel, Art is a contra product that provides man with selffulfillment, unlike alien nature, which he merely found himself in. And for Gottfried Semper, man “builds in miniature, a world in which the cosmic laws appear before him.” But Alois Riegl captures these bits succinctly.

All life is an endless altercation of the individual “I” with the surrounding world, the subject with the object Man in a state of culture finds a purely passive role towards the world of objects by which he is completely conditioned impossible, and he sets out to regulate his relation to it, to make that relation one of independence and autonomy He does this when by means of art (in the widest sense of the word) he seeks another world, which is his own free creation, to put beside the world, which was none of his making (p 7)

From Karl Max who supports the above position, art is “the self estrangement of man from himself and from nature thereby enhancing ‘species being’ and life activity” (Eisenman 1999: 103)

10

Other ideas that are related to the above conceptual frames about art require also to be recalled here. Louis Finkelstein (1982: 40) holds the opinion that “Art represents man’s erotic longing to posses the world through shapes and colors.” And when Paul Cezanne said, “I have not tried to reproduce the world, I have represented it,” he was expressing the same views as above.

Gyorgy Kepes’ definition from the above then becomes fitting that; “Art is a sensuous form of consciousness, an important instrument in the conquest of nature and representation in the creative assimilation of nature” (1962: 29). He further explains that man by definition “implies those actions which reach out and transform his environment.” The central point in these definitions negates the identity constructed of the museum piece. Art is the human recreating and regenerating his or her environment in all its form, whilst Mother Nature provides the lead. Thus, art is creation by a subject whose origin emanates from this subject’s insight and attributes to assimilate nature.

The making of art and the value for culture can be likened to the creation of Eve in the biblical story In the midst of all creation including animals, Adam remained lonely God noticed his loneliness, and willing to improve this, he put man to sleep and out of man’s rib made a wo-man Adam finding a companion exclaimed; “This one at last is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” (Gen 2 21-23) It is this identification with kind (my kind) which issued from Adam that mankind recognizes; with art also, as my-kind, unlike alien nature This is what the explanations above offer regarding the essence of art That deep-seated spiritual leap

which humanity enjoys with the product of his/her hand is also suitably called to attention by Pope John Paul II in his letter to Artists during the Jubilee year of 2000 AD.

None can sense more deeply than you artists, ingenuous creations of beauty that you are, something of that pathos with which God at the dawn of creation looked upon the works of his hands. A glimmer of that feeling has so often shone in your eyes when like the artist of every age captivated by the hidden power of sounds and words, colours and shapes, you have admired the works of your inspiration, sensing in it some echo of the mystery of creation with which God the sole creator of all things, has wished in some way to associate you (1999: 3-4).

In the above contexts, we are reminded again of Professor Nwodo’s submissions What we have encountered so far by the conceptual frames regarding art is simply that art as Heidegger observes is a revelation of the “Being of Being ” Art is a spiritual product that accords the human being a deep sense of self fulfillment In this regard, the essence of art is beyond mere ephemeral outings and celebrations of museum exhibitions Even in spite of the spiritual elevation, which such altitude was designed to imply (Gadamer, 1986); art remains a great phenomenon for the celebration of life

The movement of art towards debasement as Stephen Bann notes started with classical Rome The Medieval period arrested that drift for a while But the renaissance period and its humanistic agenda once again hastened the debasement of art With the enlightenment, the value of art as axiology was further whittled down This occurred, in part, when artists gained autonomy from sole patronage which

11

the church and feudal lords had monopolized. The new concept of practice, and the identity which the work of art now assumed in the West was received in Africa with the former’s colonial adventurism. In spite of the above cultural dialogue leading to the adoption of the West’s repositioning of the idea of art, a lingering medieval flavour still hangs with the perception of art as practice and idea among non-Western cultures.

One institution emanating from the enlightenment tradition is the museum with its’ birth in the 1830’s. The museum institution stands on the threshold of completely alienating art from humanity. Art, an alienated object of the cultural product of humanity is now another type of a revelation whose meaning is thought to be complete in the museum display shelf. Art, unburdened from preponderant instrumental use, is located within high culture and supposed spiritual value, and is limited to the genres of architecture, sculpture, and romantic art (comprising painting, poetry and music). Thus the museum ideology was conceived to attend to the above categorization only as they are assumed to be sufficient unto themselves, in what is often referred to as “museum aesthetics”.

The strategies of the museum, in the way it relates to the work of art, remain opposing to the nature and essence of art: Humanity did not create art to put it away in an object and subject relationship Rather, humanity created art and still creates art (even in the restricted sense of paintings, prints and sculptures alone) to walk in and around them, to work in art whilst cohabiting with the art, without the artwork being an obstruction at all The museum as an

institution has by its nature and structure denied this union for a long time. In another argument, as Eisenman (1999: 102) notes on the same issue, there is a way the bourgeois class dominates the idea of art and the museum as an institution that was funded by the enlightenment. Eisenman’s position and its Marxist flavor are corroborated in the argument that art became a commodity to be appropriated by the bourgeoisie once it became freed from feudal and ecclesiastical holdings.

From the foregoing, it would appear that the museum institution is obsolete in its relation to art as cultural patrimony of humanity. The museum as an institution is still relevant to humanity as a product of culture. Museums have enlarged their scope to conserve all sorts of nature and human-made things. With regards to its relevance to art, the museum, since its inception, has been constantly searching for ways to reunite humanity with art as a revelation of the “Being of Being”. One such agenda is the various efforts to reinvent the museum, where the idea is to install art for humanity, that he or she may experience a union with the product of his or her imagination.

The strategies for this reunification are as diverse as can be imagined and they include among others, the strategy of installation In this regard, the work of art is assumed to be put in place within a space in a tacit atmosphere of a comely encounter between the object and the subject This strategy also has been favoured by the expanding contexts that the word ‘art’ has continued to accumulate since it’s bracketing within the “fine art” category

The word installation is a noun that derives from a transitive verb in-stall To install implies to set

12

in a site, to fine-tune for utilization, to reconcile an object within a place. The origin of the word is Medieval Latin, in-stallare, where the prefix ‘in’ performs a causative function to stallum, which means ‘to place’. The term installation, thus, runs counter to the other terminology of popular exchange–‘exhibition’, which had dominated the contexts of artistic displays. Exhibition, also a noun, draws on the transitive verb, exhibit, which explicitly addresses the necessity to let somebody see a display or to present a thing to public view. Going by the definition above–‘to install’, it would appear, implies a movement away from the prevalent idea of presenting art to the public. In other words, installation redefines as it rehabilitates our original relationship with the things we make. It also redefines in a significant sense, the museum aesthetics or the notion of ‘art for art sake’.

The expanded focus that installation implicates relates to George Kubler’s recognition of humanity’s visual culture as consisting of the totality of human-made things (Davis, 2011). The opening paragraph of Kubler’s book The Shape of Time, captures this comprehensive reintegration of art as the totality of [hu]manmade thing; “Let us suppose that the idea of art can be expanded to embrace the whole range of man-made things, including all tools and writing in addition to the useless, beautiful and poetic things of the world. By this view the universe of [hu]man-made things simply coincides with the history of art” (my emphasis).

The useless things approximate to objects categorized as fine art, the beautiful things fall within the craft traditions, and the poetic things relate to other ephemera that are not visual in nature The central point which Kubler makes,

and which is explicit with the practice of installation, is humanity’s patrimony over what she/he has made to live with even when the museum institution appears to exclude him/her from them. We now also come to terms with an expansion of what can be exhibited within the former museum aesthetics ideology, as the institution has now become home to the diverse categories of things that humanity has made.

Gerald McMaster (1998), in Museums and Galleries as Sites for Artistic Intervention introduces us to some teasers on the above subject. One emerges from ethnic stereotype and the other from the gate-keeping mentality associated with the reinvention agendas of the museum. As a non-Westerner artist and curator, his agenda at transgressing known canons of exhibition remain of interest. He acknowledges the hold Western epistemology which funded the colonial project has on the art world discourse. Such monopolization which McMaster confronts is commented upon thus in Chinua Achebe’s disavowal of the notion of ‘universals’ “I should like to see the word universal banned altogether from discussions of African literature until such a time as people cease to use it as a synonym for the narrow self-serving parochialism of Europe, until their horizon extends to include all the world” (Nwodo, 2004:176) If, as Achebe underscores that some concepts are diffused appropriation of some other concepts irrespective of where they feature, and therefore their validation should be seen as such; and on the other hand, if their employment in discourses is to be entertained, we are then confronted with seeking out the protocol that governs their use and the way they deviate from, or are aligned to similar protocols

13

McMaster as an artist and a curator has set out at various times to subvert protocols and to confront the gate-keeping mindset of his audience in his installations. In the exhibition

Savage Graces, 1992, which held at the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology he exhibited his contemporary constructions, though designed to look racial, to excite some curiosity. It should be noted that a museum of anthropology houses not art but ethnic objects that are supposed to be curious in their dispositions. But in the installation (Im)polite Gazes, 1995, installed at the Ottawa Art Gallery, the full implications of his subversion intents became manifest. He declares thus evaluating the responses that greeted both spatial incursions and subversions “I was confronted by an essentialist notion of place and identity, and I was being resisted for challenging the audience’s assumptions and common sense” (254).

Subverting stereotypes and querying dominant narratives becomes apparent also in Sokari Douglas Camp’s Schidkrout, 1999, an installation hosted at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The installation was organized by the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. Douglas Camp’s strategy was to reunite the mask to its frame–the masquerade–an ‘accumulated sculpture!’ The masquerades she constructed were in steel. The contradictions that greeted the audience in this installation were many. And it read: ‘tribal masks’ on modern steel works of sculpture, in a museum of Natural History?

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons’ installations at the Norton Gallery, West Palm Beach in 1994, Seven Powers Come by Sea, 1993, Spoken Softly With Mama, 1998, and Umbilical Cord, 1991 are narratives also designed to transcend

the irony of the museum couched on aesthetic modernism (Bell, 1998:33-42). I am Bahamian. I eat Conch Salad emerges from the same strategy to give a comprehensive story of a people and a place.

The installation of fine art and (fashion) design under the new rubric of human-made things is bound to a narrative that validates art as axiology. The value is that the limited narratives associated with fine art aligned in a structured synchrony with design become reconciled in a neighborly continuity within human productions.

The installations in this exhibition challenge the canons established by the West in the structural relationship that exists between the aestheticized notion of art against what Kubler defines as the [hu]man-made thing, as it also interrogates the stereotypes associated with museum labels

Here we confront the artificial boundary between a museum dedicated to anthropology, where the study of African art has been domiciled as a non aesthetic category but all the same belongs to the family named visual (material) culture, and the supposed gallery space where institutionally canonized art is exhibited In other words, this event designed to provoke, metaphorically remains a teaser in the way it has played up the paradox of the museum Its’ actualization is a coming to terms with the reality that art as essence should not be couched in the quaint stereotypical canons of the Western enlightenment And such an intervention can be valued for expanding Euro-centric canons especially the way art has all the while been defined along with their spaces of encounter

To retool cultural institutions in the light of new insights remains the norm. As it is always the

14

case, critical modernity will always lag behind in reconciling with advancements enacted within culture. It is to be noted that cultural advancements are not programmatic; hence cultural events happen to transcend previous notional boundaries depositing new identities. Often they are enacted in two forms; the first is that efforts will be made by progressive humanity to accommodate the old ideas while transcending them. The second and the most dangerous is that violence will come from those who do not comprehend foundational principles of received culture, but in relating normatively with such customs redefine it. This they do by investing on such customs their own aestheticized notions.

It is important to note the way the idea of installation sits with exhibitions; it enacts a definite manifesto on the death of ‘official’ art. The truth it plays up is that art was never created to last forever or to be made into fetish object. The ephemeral nature of objects of installation along with their high mobility and adaptation to new spaces remains noteworthy. By and large, the museum institution is strategic to culture. For the present, however, the museum institution must continue in its objective to rehabilitate art and locate more ways to unite art with humanity.

For the contemporary artist and their curator be they conservatives or progressives, art must be reunited with its maker This is the original idea of the birth of art by humans African cultures kept faith with this focus until the impact of the colonial agenda overwhelmed its cultures The teasers that installed objects instigate are pointed at erasing the constructed binaries in the world of human-made things Can art once again imply for the African that action by which he or she should reach out, to positively

transform his or her environment just like the medieval African artist who cared for the shrine environment where he installed the statue? Can he or she then also keep their environment clean and structured, equally like the interior decorator who represents a new environment that is ordered and peaceful with its installed furniture and sundry domestic needs?

Prof. Frank Ugiomoh, Sculptor, Printmaker, Professor of Art History and Theory University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

WORKS CITED

BANN, STEPHEN.“Art History and Museum” The subjects of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perceptive Eds. Mark A. Cheetam, Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxey, (Cambridge: University Press, 1998)230-249

BELL, LYNNE. “History of People who were not Heroes: A conservation with Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons” Third Text 43 (Summer 1998).

DAVIS, WHITNEY. “World Series: The Unruly Orders of World Art History,” Third text, (112, 25:5 2011) 493-501

EISENMAN, F. STEPHEN. “Negative Art History: Adorno and the Criticism of Culture” Art Journal (Spring 1999):101-4

GADAMER, HANS-GEORG. The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays Translated by Nicholas Walker, ed Robert Bernasconi, (Cambridge: University Press, 1986).

JOHN PAUL II PP, Letter of His Holiness Pope John Paul II to Artists (Vatican City Vaticum Press 1999)

KEPES, G. The Language of Vision, (Paul Theobald & Co 1962)

MCMASTER, GERALD. “Museums and Galleries as Sites of Artistic Interventions” in Eds Mark A Cheetam, Michael Ann Holly and Keith Moxey, (Cambridge: University Press, 1998) 250-261

15

NWODO, C. S. “Philosophy of Art versus Aesthetics”

British Journal of Aesthetics 24: 3 (1984)

NWODO, C. S. Philosophical Perspective on Chinua Achebe, (Port Harcourt: University of Port Harcourt Press, 2004)

PODRO, MICHAEL. Critical Historians of Art Yale: Yale University Press, 1982

ROBERTS, JOHN “The Museum and the Crisis of Critical Postmodernism” Third Text 41 (Winter 1997 – 98).

SCHIDKROUT, ENID “Challenging Exhibition” New Paradigms, Same Old Questions” African Arts (Autumn 1999) pp 1, 4 – 6, 8

The New Jerusalem Bible Standard Edition (London: Darim longman & tools 1985)

16

I am Bahamian.

I eat Conch Salad.

I have spent some time looking into the history of The Bahamas. It is interesting for me to learn that about one score and a half years after the Fall of Columbus, almost the entire population of the native Bahamians was exterminated from the Bahama Islands. Hence many of the cultural influences that make up the present Bahamas have come from other lands, and blended to form one unique identity. One identity of yet many constituents. What does it imply to be Bahamian, am I an individual of many identities, or one, of a single identity: the Bahamian identity?

The whole curiosity in these facts, and its’ significance makes it become important for me to make, with this Bahamian society–through the artist community in Nassau, this collaborative intervention of interdisciplinary nature. Coming from Nigeria, I feel a connection with The Bahamas, and the people here. There is so much similarity in many aspects of the Bahamian culture when compared with the situation in my part of Africa.

I cannot help but wonder if it has to do with heritage, or with the effects of colonialism?

Perhaps for this reason, I am especially led to compose this collaborative experience with Bahamians. It is noteworthy that the participating artists in this project speak for every Bahamian who more than most people in The Bahamas, show through their physical demeanour, a closer kinship to Africa. This is so only because this project is about ‘one voice from Africa’ and on the other hand, a message to Nigeria.

Another reason for choosing to make an artistic statement of this nature is to through this Installation of artworks, present the mixture

which is the Bahamians–a people made up of an incorporation of cultures and races–as is usually said–the melody of Europe and the rhythm of Africa. But what about the Arawak Indians? Therefore, this special lifestyle of communally accommodating one another becomes a striking education. I have learnt this for my country, but unfortunately, it is not a law that could simply be implemented, but a lifestyle to be emulated.

I wish to learn the views of more people–from artists here through their artwork, and words; and from other persons here through whatever means they choose, in this scheme. I hope that this procedure becomes a cathartic process on a topic such as this, whereas the public would also find many art pieces to spend time with, come to terms with, admire, appreciate, and learn from. On my part, I am interested in not only reflecting on original cultural identities, but also in providing a vision of a future in which more and more people, as migrants and permanent travelers, are becoming part of original nations, where the nation in turn becomes ‘unoriginal’. Is cultural identity still determined by geographical origins, ancestry or biological disposition? Perhaps it is increasingly becoming a hybrid construct that an individual can determine or change.

This intervention presents a body of work to be exhibited in Nassau, an art experience for everyone, rather than an exhibition of work that is solely mine I believe that this method of working will provide for better participation where more people would work together, sharing ideas and knowledge I have in the past worked on my own and exhibited my work This time I am interested in exploring

17

a fresh challenge; looking to bring together the feelings and voices of Bahamian artists and designers; some, out of a group of artists who have spoken a language I understand, through whose works I can feel some energy, and through whose works I wish to join in the same expression.

In my home country Nigeria, this situation of cohabitation and reflections on cultural identities, should also begin to pose questions, and seek answers to the question of ‘who are my kinfolk?’ This can be seen in various dimensions.

For the ‘I eat Conch Salad’ project, all participants contribute to a single voice Hence, it is not intended that the designs which come into this collaboration be shown on the runway with Models, or that Paintings and Sculptures be on stands with each artist’s name and title of work, immediately against the work We are looking for a different experience An architectural piece of Installation to be made out of the incorporation of these strong works of art (See Bourriaud, Nicolas 2005) 1

Each artist is acknowledged, where their ideas are discussed and documented in the written texts and publicity materials that accompany the show

1 Bourriaud, Nicolas, Postproduction: Culture as Screenpaly: How Art Reprograms the World (New York: Luckas and Sternberg, 2005)

18

The Making of the Project

Being creative is about finding fresh grounds–the unbeaten path. This is exactly what we seek with this venture! This is not about any one artist, but about the group, and about The Bahamas, and perhaps, Africa. It is hoped that the participating artists will continue to grow collectively and individually even after the project.

The story of I am Bahamian. I eat Conch Salad. is being written this week. It continues to grow, until it is born by Saturday, July the 10th, the Independence Day of The Bahamas. From then, it will be open to the public for 10 days. After which it is impossible for it to be seen anywhere, and there will be nothing else exactly like it.

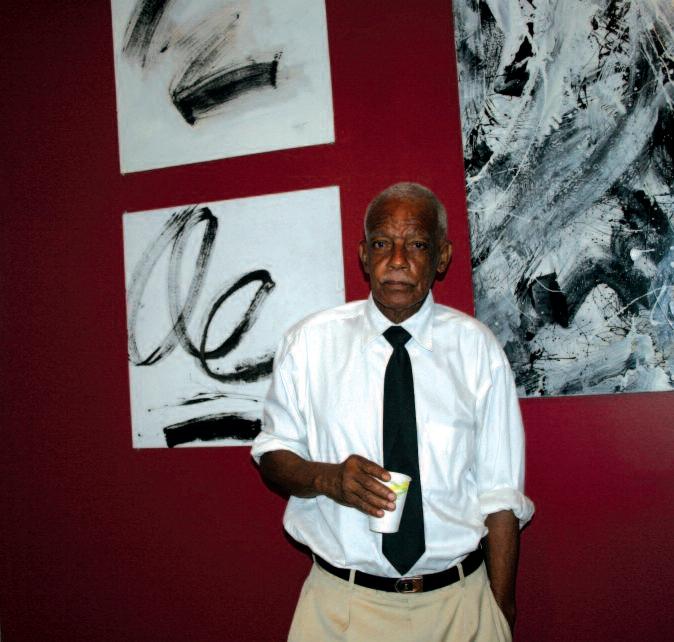

The nine artists participating in the making of this intervention are: Amarachi Okafor (Nigeria); Kishan Munroe (Bahamas); Tyrone Ferguson (Bahamas); Apryl Jasmine Burrows (Bahamas); John Beadle (Bahamas); Harl Taylor (Bahamas), Percy Wallace (Bahamas); Jeff St. John (Bahamas); Kendal Hanna (Bahamas).

This is a collaborative intervention, and through our several ideas and contributions, we are working on a major statement narrated through the theme I am Bahamian. I eat Conch Salad. For this, the artists’ individual pieces combine, and are interwoven to form one body of work rather than several pieces. As such this collaboration is like a song sung by a choir of nine choristers, but harmonized as one song.

The overall theme taken from the concept of the Bahamian Conch Salad, alludes to the mixture of a people, The Bahamians. It also calls to mind the harmony in this mixture of people who even despite varying ancestral backgrounds are proud to say: I am Bahamian! This apparent unity, or the lack of it, is my fascination.

Our intention is to build a discourse where people connected to Africa would describe The Bahamas. Each artist and ambassador in this project contributes ideas through one of the following themes:

1. Our Prides as Bahamians.

2. Our Lifestyle.

3. Our Strength.

4. Our Joys as a people.

5 Our Desires and Longings as Bahamians, and for The Bahamas

6 Gaps and Commentaries on our unity By ‘Gaps and Commentaries’, I allude to the alternative feelings that the artist might have concerning the (apparent) unity and peaceful cohabitation within the mixture which is the Bahamian people and cultures It is also about the alternative energies and inspirations he might perceive as an artist–a messenger, a prophet in, and for his society, on the topic

7

Our History

8. Our Future, and messages for the future –A speculated future of The Bahamas, and messages for the future, to Bahamians, as a people.

We grow this week, as we make…

Amarachi Okafor, July 2010

19

JOHN BEADLE Biography

John Beadle (born 1964, Nassau, The Bahamas), lives and works in The Bahamas, on the Island of New Providence. He is one of the major Bahamian artists of the post-Independence generation. One of his earliest memories is of watching one of his grandfather’s landscape paintings, waiting for someone to walk into view. He went to the College of The Bahamas and studied under Stan Burnside, going on to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where he obtained a BFA in Painting. He studied in Rome, as part of RISD’s European Honor Program, and received an M.F.A degree in painting from the Tyler School of Art, of Temple University.

A founding member of The Bahamas most p r o m i n e n t a r t i s t c o l l e c t i v e s , O P U S - 5 a n d B-C.A.U.S.E. (Bahamian Creative Artists United for Serious Expression), his works are in many private and corporate collections, including the National Collection of The Bahamas. Several of his series are about the despair of the illegal migrants who arrive by boat from Haiti, and he shows great dexterity in his use of different materials such as incorporating oars and machetes into his work. In 1991 he was named Emerging Artist of Latin America and the Caribbean in Nagoya, Japan.

As well as exhibitions in The Bahamas, Beadle’s work has been shown in the United States, Germany, France, the Santo Domingo Biennale of Painting, the Sao Paolo Biennale in Brazil, and in New Zealand. In 2003, his work was chosen for the Inauguration of The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and has been chosen at every annual exhibition of the NAGB since then. Beadle took part in the Big River 3 International Artists’ Workshop, Aripo, Trinidad, 2006 and the 5th Insaka International Artists Workshop, Livingston, Zambia, 2010. In 2010, he was selected to

create a sculpture piece for Lynden Pindling International Airport, in Nassau, The Bahamas. He is a member of the art group B.B.B. He is also a principal designer and sculptor in the ‘One Family’ Junkanoo festival group.

On “Gaps/Commentaries on our unity” Beadle with his awe-inspiring piece that brought so much grandeur to the show, made his personal commentary on the popular opinion about the Bahamian culture, and gaps, as he perceives them: “ as islanders the eternal seascape has made us look outward, toward the horizon It has turned us into an extrovert people, smiling and generous to the stranger But within us, there is something more difficult to see: a secrete sadness, shared rarely, the product of our microcosmic isolation; of our solitude in the midst of so much sun and so many tourists It is a shipwrecked impatience, in fact, which has always pushed us to abandon the islands for other, ampler, richer, more populous lands, for scientific and technological capitals where we think that things of capital importance happen ”

–THE NEW ATLANTIS: the ultimate Caribbean archipelago, ANTONIO BENITEZ-ROJO

The above excerpt outlines one of the principal ideas around the making of this piece Apart from talking about Caribbean people in general, Beadle has largely been using his more recent works, which majorly deal with the subject of immigration, to examine and come to a better understanding of a more personal matter: his father’s search for ampler, richer land What is it that made this country so attractive, and his country (Jamaica) so unattractive? Was the grass here that much greener? He says, “I often wonder how he must have felt navigating a hostile antiJamaican landscape I have heard him reflect on the general attitude of Bahamians to Jamaicans, I have gotten a sense of the bile he tasted, and the venom he had to fend off ”

20

JOHN BEADLE

Theme: Gaps/Commentaries on our unity

Artist:

Artist:

21

KISHAN MUNROE Biography

Kishan Munroe was born in Nassau in 1980.

As a young and aspiring artist, he was accepted into one of The Bahamas’ most successful programs for young artists–the Annual FinCo. Art Workshop, sponsored in part by the Finance Corporation of The Bahamas; and geared towards the refinement of the talents and skills of the country’s most promising artists. In addition to this accomplishment, Munroe worked under the tutelage of some of The Bahamas’ most renowned international painters.

Kishan has an M.F.A. in Painting, from the Savannah College of Art and Design (S.C.A.D.) from 2003; and a B.F.A. in Painting and Visual Effects also from S.C.A.D., Magna Cum Laude.

He is the recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts; multiple awards from The Central Bank of The Bahamas; The Nancie Mattice International Grand Prize Award; and the Combined Merit fellowship at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

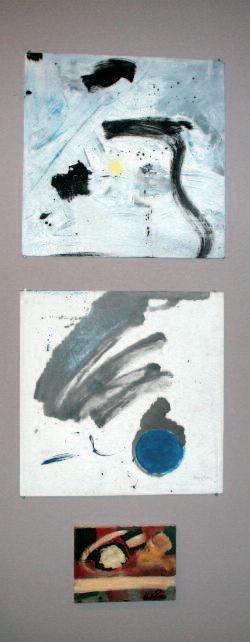

Kishan Munroe’s work often talks about our human experiences: the moments, periods, eras when we make transitions from life to death, from joy to sadness, ignorance to understanding, or ecstasy to agony. Going beyond representing the superficial, Munroe repeatedly seeks to engage with the parts of us that we might prefer to keep hidden–the fears and frailties which we hope that no one perceives. He seeks to unearth all those unspoken injustices that we sometimes righteously defend. Munroe has been shown in the Caribbean and in the U.S.A, and is included in a few public and private collections.

In August 2008, Kishan had embarked upon a multi-media tour named ‘The Universal Human Experience’. With paintbrush and camera in hand, coupled with his passion, Munroe set out for an ambitious trail around the universe. The intention for the tours was to inform and educate the universal community, thus, advancing cultural understanding and tolerance. Through his imagery, he shows the many different stories of human efforts and conquests while looking for a common ground.

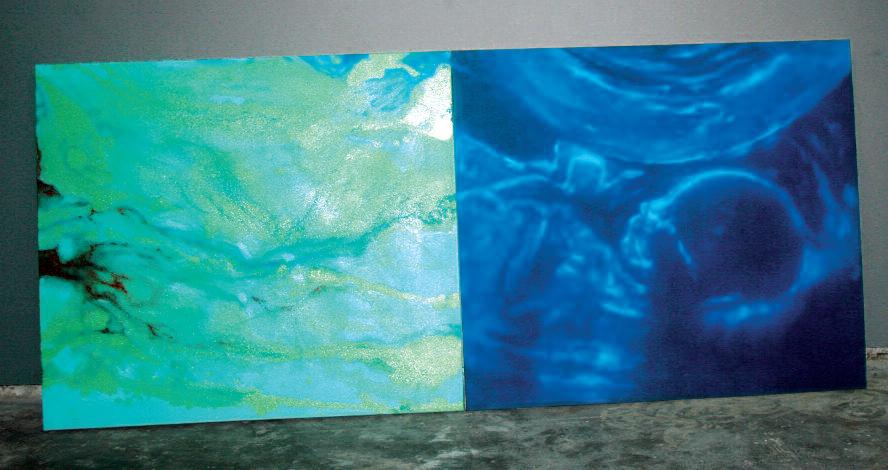

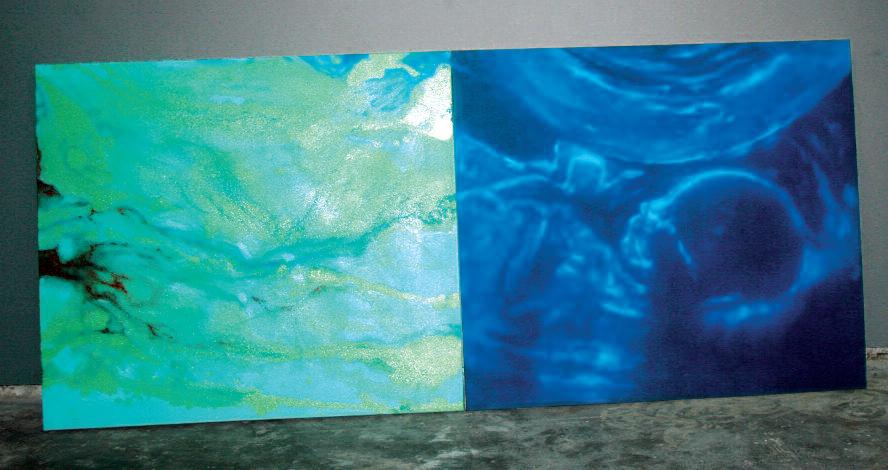

On “The Future”

For this project, Kishan is thinking ... ‘when oil and water mix?’

According to Munroe, ‘these do not mix!’

Oil is the foreign entity, whereas water is the indigenous one. Munroe says that the very fear of the common Bahamian is the fact that foreigners and indigenous people are getting to merge so much, up to the point where the indigenous loses itself and would defy recognition. But then this action is also rather impossible and cannot happen, according to Kishan, because oil and water do not mix.

Kishan Munroe seems to combat the very ideology that this project is founded on–the seemingly pleasant Bahamian cultural and political mix.

28

Artist: KISHAN MUNROE

Theme: The Future

29

JEFF ST. JOHN Biography

Jeff St. John is from Nassau, The Bahamas. At the vanguard of Bahamian high fashion, St John learned his first lessons in design from his mother, who was a dressmaker, and has more than 40 years experience in the industry. He worked in New York, but he returned to Nassau full-time about 20 years ago to establish the ‘House of St John’.

St John studied between 1968 and 1981 at Trade Technical College in Los Angeles. He has won Designer of the Year award both in 1982, and in 1998.

In the 2009 Islands of the World Fashion Week (of Unesco and the Mode Îles Limited), Jeff St. John won the Seal of Excellence award from the judges.

His award-winning designs for the Fashion Week, he says, “were intended to reflect the Caribbean’s cultural debt to Africa, ‘it’s rhythms, its colours,’ and even its drums.” Always, he returns to his own roots to find inspiration in “the natural beauty that surrounds us in The Bahamas and in the elegance and good manners of its people.”

Wraps, scarves and bikini or tube-style tops featured heavily in his award-winning collection; utilizing the locally-manufactured fabrics of Androsia and Bahama Hand Prints, he had made the outfit for the ‘Miss Universe 2009’, which she wore at her press briefing on the morning after her crowning, on 13th August 2009. Among many renowned Bahamian fashion designers such as Basheva Eve, Bryda Knowles, Patrice Lockhart, Sabrina Francis, Cedric Bernard, Percy Wallace, Judy Deleveaux, Kathy Pinder, and Tesha Fritz, Jeff St. John’s design was also featured at the

‘African Bahamian Culture-Rama,’ an exciting show of African and Bahamian Fashions, Music and Dance, organized by the African Bahamian Association–a non-profit organization with membership of Africans, Bahamians and other persons of African heritage or interest, in The Bahamas.

On “Our Joys...”

Marriage plays a very important part in the life of every adult human being. As we grow into maturity, and are ready to be functional in the society we think of marriage, and we want to settle down to this phase of life. It is known over time, that people from all over the world come to marry in The Bahamas. As to the kinds of marriages that couples are interested in having–some want traditional weddings, and some want to walk down the isle... But at the end of it, what does marriage represent, to us? Is it all about just the wedding, or the actual marriage thereafter? What kind of marriage do you want to have?

Utilizing his renowned Androsian prints, laces, and luxuriant frills and flounces, St John created a glow with an array of the warmest colours at this show.

30

Artist: JEFF ST. JOHN

Theme: Marriage–A joy

31

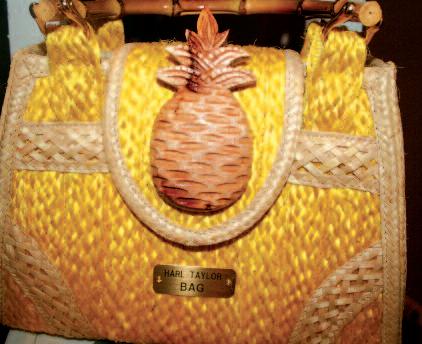

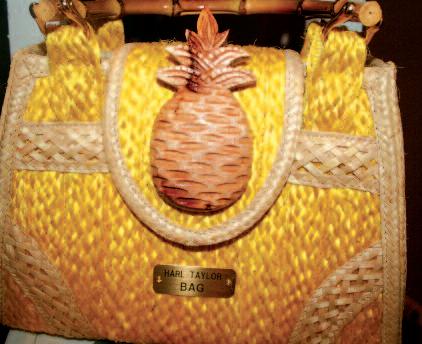

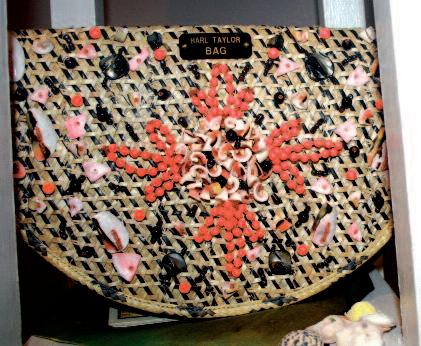

HARL TAYLOR Biography

Harl Taylor grew up in Nassau, but left to study interior design at New York’s Parsons School of Design. Realizing that he loved fashion more, he left for Paris, where he interned with fashion giants Karl Lagerfeld and Givenchy, before graduating in 1992. Afterwards, he worked as an assistant designer at the couture house of Rochas, one of Paris’ premier houses of haute couture; while he also designed and made garments for clients, many of who had 2nd homes in The Bahamas. Taylor afterwards returned to The Bahamas to set up his mark on the Caribbean fashion scene. He established the Harl Taylor BAG designer label. A graduate of Parsons Paris, whose alumni include such iconic names as Donna Karan, Willi Smith and Marc Jacobs; Harl Joseph Taylor had his pick of jobs in top fashion houses, but his decision to return to The Bahamas placed The Bahamas on the fashion world’s map.

Harl Joseph Taylor was born in The Bahamas in 1970. Harl Joseph Taylor died in The Bahamas in 2007.

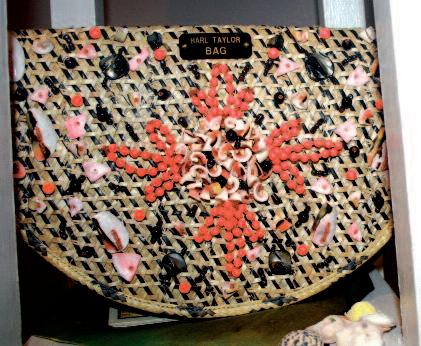

His surprising mix of the lush with the simple and natural was purely awesome. Harl created many things in his time, but his signature piece however, was his “Handbag”. He made handbags out of straw with luxurious lining, adorned with rich beading, mother of pearl, conch shell, mahogany carvings.

These bags started out as a fun experiment and evolved into something that elevated the Bahamian straw industry to another level. Made from straw, with bamboo or faux tortoise shell handles; the bags were initially made as special gifts for his clients. Many of the bags were named after the specific woman for whom they were initially created. Each beaded, straw bag, embellished with sea shells, was an exquisite ‘work of art’, in and of itself; they were beautifully packaged, with loving care, surrounded by sand and sea shells. These incomparable ‘art pieces’ evolved over the years into ‘fashion status symbols’, both nationally and internationally. His gifted mother Beverly, a retired Science Educator and two of his former employees, continue his work as they spread the beauty of Bahamian straw craft to many.

On “Bahamian Lifestyles”

The luscious and luxurious bags that Harl created are ‘must have’ items sought out by celebrities and fashionable Bahamian residents alike. Harl Taylor’s customers were the best advertisement for his bags, and the stylish women who carried his coveted creations were proud to be owners of a Harl Taylor Bag. The Harl Taylor bag was a couture item, a fashion badge and when you carried it, you became a member of a (Bahamian) exclusive club.

32

HARL TAYLOR

Theme: Bahmamian Lifestyles

Artist:

Artist:

33

Artist:

Artist:

Artist:

Artist:

Artist:

Artist: